↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly used for complex reasoning tasks, but existing serving systems are inefficient due to the high and varying computational costs. These systems fail to adapt to the scaling behaviors of reasoning algorithms or the varying difficulty of queries, leading to inefficient resource utilization and unmet latency targets. This results in wasted compute, degraded accuracy, and missed latency targets.

To address this, the researchers developed Dynasor, a novel system that optimizes compute allocation for LLM reasoning. Dynasor uses a new metric called ‘certaindex’ to dynamically track reasoning progress. Based on certaindex, Dynasor adapts compute allocation: more for difficult queries, less for easier ones, and early termination for unpromising queries. This approach significantly reduces compute usage (up to 50% in batch processing) while maintaining accuracy and improving latency (up to 4.7x tighter latency SLOs in online serving).

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical challenge of efficiently serving large language models (LLMs) for complex reasoning tasks. Current systems struggle with the varying computational demands of these tasks, leading to inefficiency and latency issues. The proposed system, Dynasor, offers a novel solution that is both effective and adaptable, paving the way for more efficient and scalable LLM-based applications. The introduction of ‘certaindex’ as a measure of reasoning progress opens new avenues for optimizing LLM resource allocation.

Visual Insights#

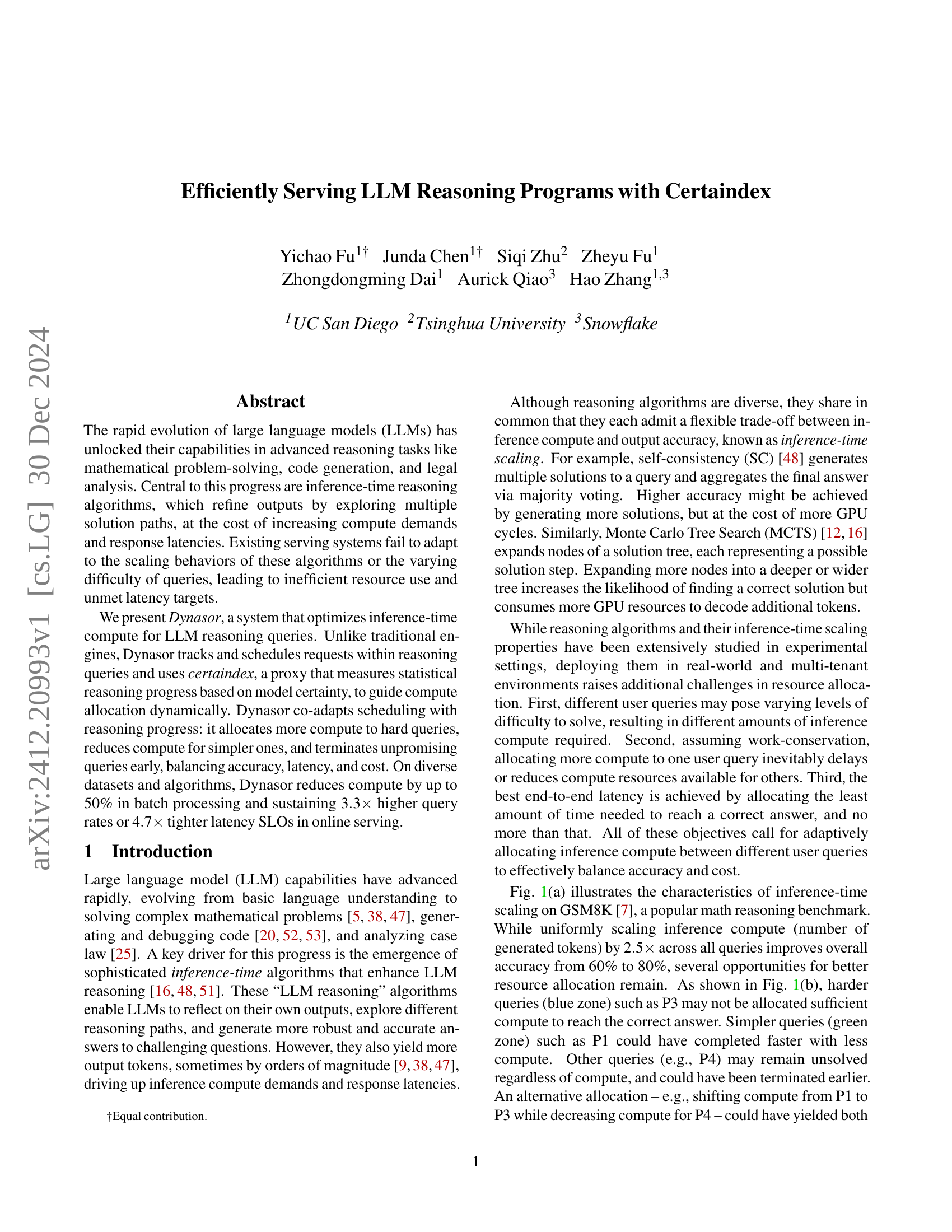

🔼 Figure 1(a) shows the inference time scaling of the self-consistency algorithm on the GSM8K benchmark dataset. The x-axis represents the number of output tokens, which is a proxy for the amount of computation used. The y-axis shows the overall accuracy achieved. The curve demonstrates the typical trade-off in LLM reasoning algorithms: increasing computation (more tokens) generally leads to higher accuracy, up to a point where further increases yield diminishing returns. The figure highlights the existence of three zones: an easy zone where a small amount of computation is sufficient for high accuracy; a scaling zone where increasing computation significantly improves accuracy; and an impossible zone where no amount of computation can guarantee a correct solution.

read the caption

(a)

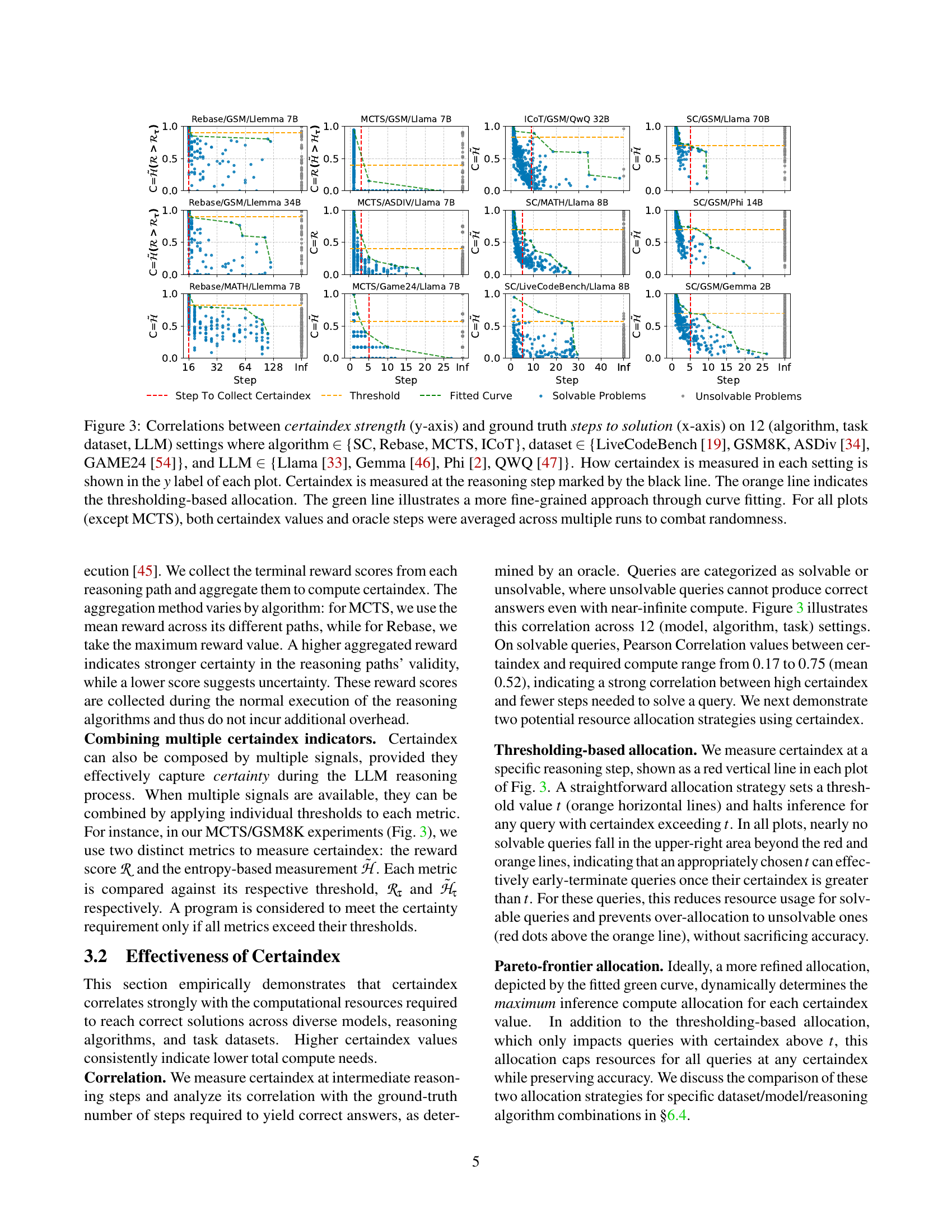

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameter settings used for the certaindex metric in Dynasor’s experiments. It shows the thresholds used for the entropy (H) and reward (R) metrics in different algorithms and datasets. The ‘Detect @knob’ column specifies the reasoning step at which certaindex was measured, indicating the point in the reasoning process where the algorithm’s confidence was assessed. Note that the Rebase algorithm was only evaluated on the MATH-OAI subset of the MATH benchmark.

read the caption

Table 1: Hyperparameter configurations for certaindex. Rebase is evaluated on the MATH-OAI [28] subset of the MATH benchmark.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Compute#

Adaptive compute in the context of large language models (LLMs) focuses on dynamically adjusting the computational resources allocated to individual reasoning tasks based on their inherent difficulty and progress. This contrasts with traditional approaches that use a fixed compute budget per task, leading to inefficiency. A key aspect is the development of a proxy metric, often termed “certaindex,” which quantifies the LLM’s confidence in approaching a solution. This allows the system to intelligently allocate more compute to challenging problems where confidence is low and to curtail resources for those nearing completion or showing high certainty. Early termination of unpromising tasks is another crucial element – preventing wasted resources on queries that are unlikely to yield accurate results. The efficacy of adaptive compute hinges on accurate and efficient measurement of progress, which should ideally be computationally inexpensive and compatible with diverse reasoning algorithms. The ultimate goal is to optimize for overall system throughput and efficiency while maintaining accuracy and fairness across multiple concurrently running tasks. Achieving this requires sophisticated scheduling mechanisms capable of dynamically allocating resources in response to evolving certaindex values.

Certaindex Metric#

The core idea behind the “Certaindex Metric” is to quantify the confidence of a large language model (LLM) in its reasoning process. It serves as a proxy for measuring reasoning progress, enabling dynamic resource allocation during inference. Instead of uniformly allocating compute resources, this metric allows for adaptive resource management. Higher Certaindex values indicate that the model is more confident in its current answer, suggesting less compute is needed. Conversely, low values signal uncertainty, prompting further exploration and the allocation of additional resources. The beauty of Certaindex lies in its generality; its measurement can be adapted across diverse reasoning algorithms, acting as a unified interface between the LLM and the system. This adaptability is crucial for efficiently serving various reasoning tasks, as it avoids the need for algorithm-specific resource allocation strategies, simplifying system design and improving resource utilization. However, the effective use of Certaindex depends on accurate calibration of thresholds. Finding optimal thresholds is essential to balance the cost of computation with accuracy and performance, necessitating calibration procedures using empirical data or profiling mechanisms.

Dynasor System#

The Dynasor system is presented as a novel, end-to-end LLM serving system designed to efficiently manage inference-time compute for dynamic reasoning programs. Its core innovation lies in the use of certaindex, a proxy metric quantifying the LLM’s confidence in its reasoning process. Unlike traditional systems that operate at the level of individual input/output requests, Dynasor understands and orchestrates the scheduling of requests within the context of entire reasoning queries. This allows Dynasor to adapt compute allocation dynamically, providing more resources to challenging queries, reducing compute for simpler ones, and terminating unpromising queries early. This adaptive approach aims to optimize the balance between accuracy, latency, and cost. The system’s architecture includes a reasoning program abstraction, a certaindex-based intra-program scheduler, and a program-aware inter-program scheduler, working in concert to achieve efficient resource allocation and task scheduling. Dynasor’s effectiveness is demonstrated through extensive evaluations showing significant improvements in compute usage, latency, and throughput compared to state-of-the-art systems. The system’s design is shown to be adaptable to a variety of reasoning algorithms and LLMs, highlighting its potential for broad applicability in serving future LLM reasoning applications.

Empirical Studies#

An Empirical Studies section in a research paper would rigorously evaluate the proposed approach, likely called Dynasor. It would present controlled experiments demonstrating Dynasor’s effectiveness across various scenarios. Key metrics to be analyzed would include compute resource usage (token count or GPU time), accuracy, latency, and throughput. The experiments would compare Dynasor against relevant baselines, such as traditional serving systems or other scheduling algorithms, under different conditions. For example, varying the difficulty of tasks or the number of concurrent requests, to explore Dynasor’s adaptability. Statistical significance would be crucial in establishing whether performance improvements are genuine. The section would ideally include detailed breakdowns of results, providing insights into the contributions of Dynasor’s various components, such as gang-scheduling, certaindex-based allocation, and the use of various heuristics. Furthermore, ablation studies should be included to assess the impact of removing individual parts of Dynasor to understand their independent contributions. Ultimately, a strong Empirical Studies section would provide compelling evidence to support the claims made in the paper.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on efficiently serving LLM reasoning programs could explore several key areas. Extending Dynasor’s adaptive scheduling capabilities to handle a broader range of reasoning algorithms and LLM architectures is crucial. Further investigation into the properties of certaindex across different LLMs and tasks is warranted, potentially leading to more robust and generalizable methods for estimating reasoning progress. Developing more sophisticated resource allocation strategies beyond simple thresholding and curve fitting is a key area; reinforcement learning or other advanced techniques could be leveraged for optimal dynamic resource allocation. Incorporating fairness considerations beyond finish-time fairness to address potential biases in resource allocation among different users or queries is essential. Finally, thorough empirical evaluations on larger-scale datasets and more diverse deployment scenarios are critical to validate Dynasor’s effectiveness and robustness in real-world production environments.

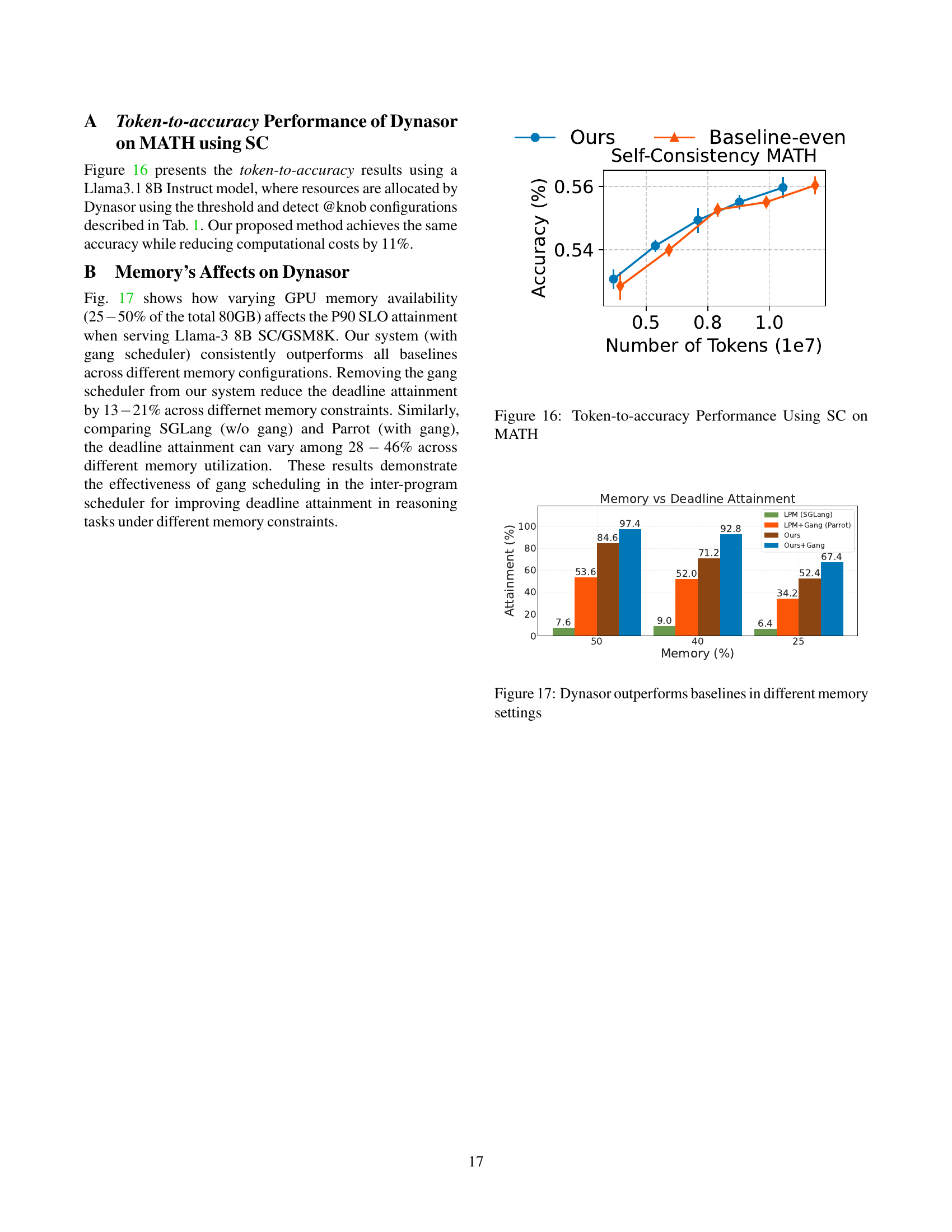

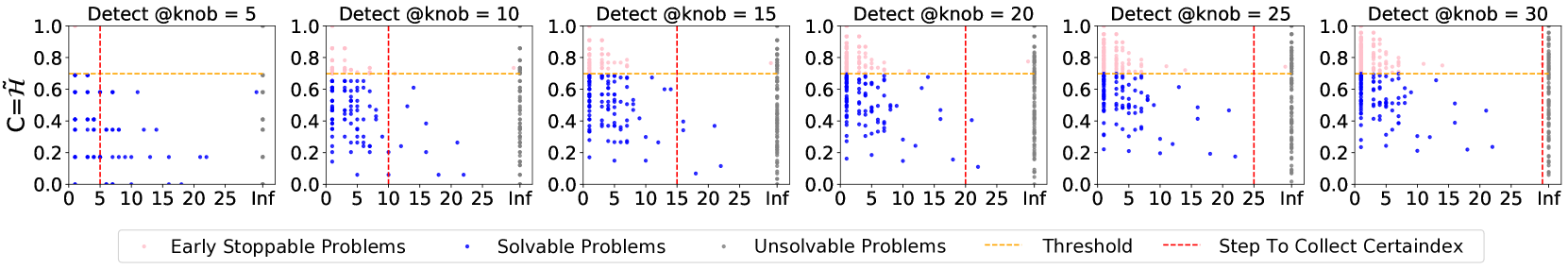

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates a canonical resource allocation comparison between existing systems and an ideal allocation scenario. It highlights the inefficiency of existing systems in allocating resources across tasks of varying difficulty. Existing systems often allocate resources evenly, leading to under-allocation for harder tasks (requiring more compute to get the correct answer) and over-allocation for easier tasks (using more compute than necessary). The ideal allocation strategy dynamically adjusts resource allocation based on the difficulty of each query to optimize for accuracy, cost, and latency.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between the certaindex values and the amount of compute required to obtain a correct answer for various questions. Each point represents a question, and the x-axis shows the amount of compute used, while the y-axis represents the certaindex. A higher certaindex indicates a higher degree of certainty from the LLM in its response, suggesting that less compute was needed to reach the correct answer. The plot demonstrates a strong negative correlation, meaning that higher certaindex values are associated with lower compute needs.

read the caption

(c)

🔼 Figure 1 demonstrates the concept of inference-time scaling and Dynasor’s adaptive resource allocation. (a) shows how accuracy on the GSM8K benchmark improves with increased compute (measured by the number of output tokens) but plateaus after a certain point due to the limitations of the model. (b) illustrates the difference between existing systems’ uniform resource allocation and Dynasor’s ideal allocation which adapts to query difficulty, providing more resources to harder queries and less to easier ones. (c) shows the strong correlation between certaindex (a measure of the model’s certainty) and the compute needed to get a correct answer, indicating that high-certainty queries require less compute.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) Inference time scaling of self-consistency [48] on GSM8K [7]. As we uniformly increase the number of output tokens (x-axis) per question, the overall accuracy (y-axis) grows then plateaus (see §2.2). (b) Canonical resource allocation in existing systems vs. ideal allocation for four queries P1-P4 with vary difficulties. (c) Correlations between certaindex and the compute required to obtain a correct answer. Each point is a question. Statistically higher certaindex indicates lower compute needed.

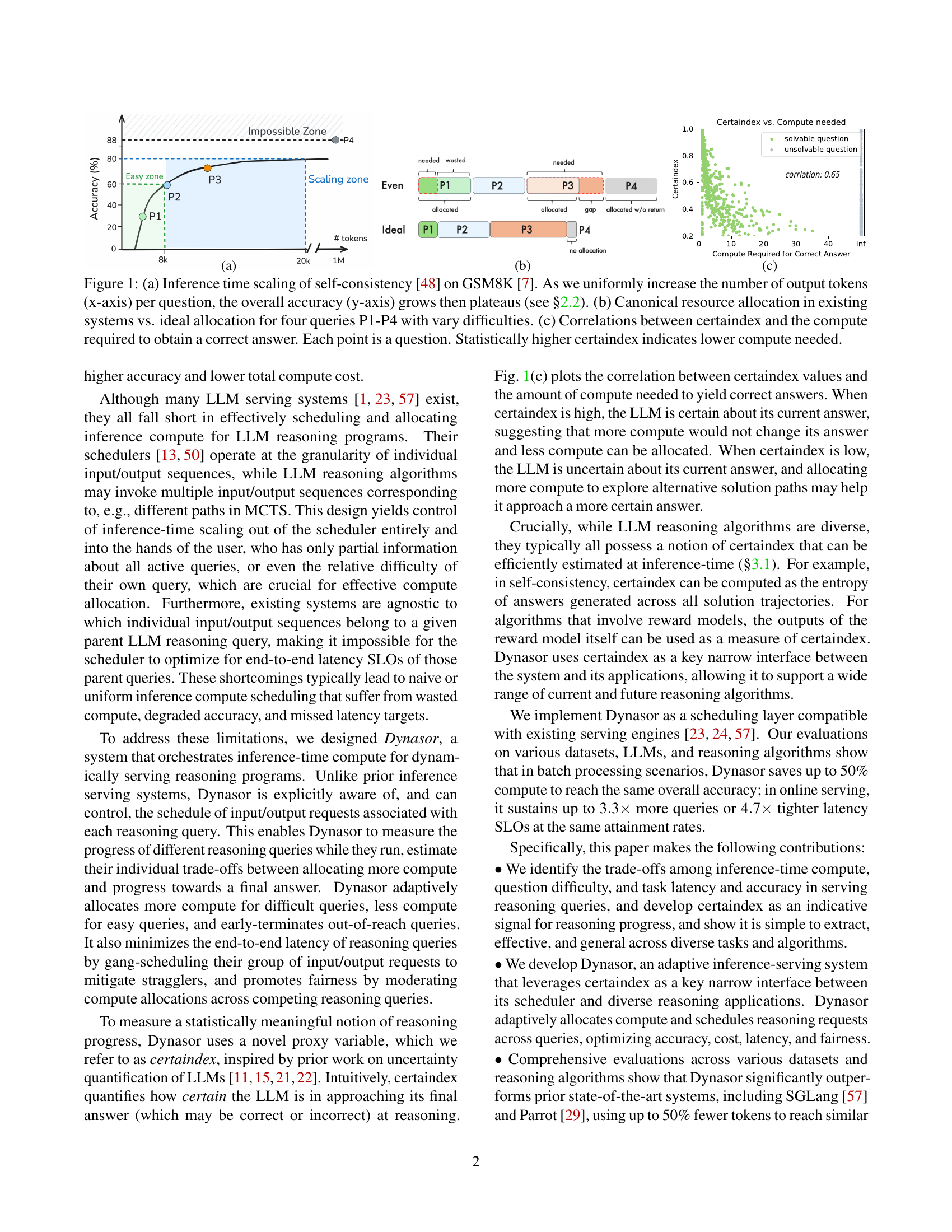

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of four different LLM reasoning algorithms: Self-Consistency (SC), Rebase, Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), and Internalized Chain-of-Thought (ICoT). Each algorithm is shown as a diagram to visually represent its process. The diagrams highlight key steps such as prompt input, trajectory expansion (representing different reasoning paths), and final answer aggregation. They also show the key control parameters (knobs) for each algorithm that affect the amount of compute used during inference, allowing a comparison of their different approaches to reasoning and computation.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of the workflow of different LLM reasoning algorithms discussed in §2.1

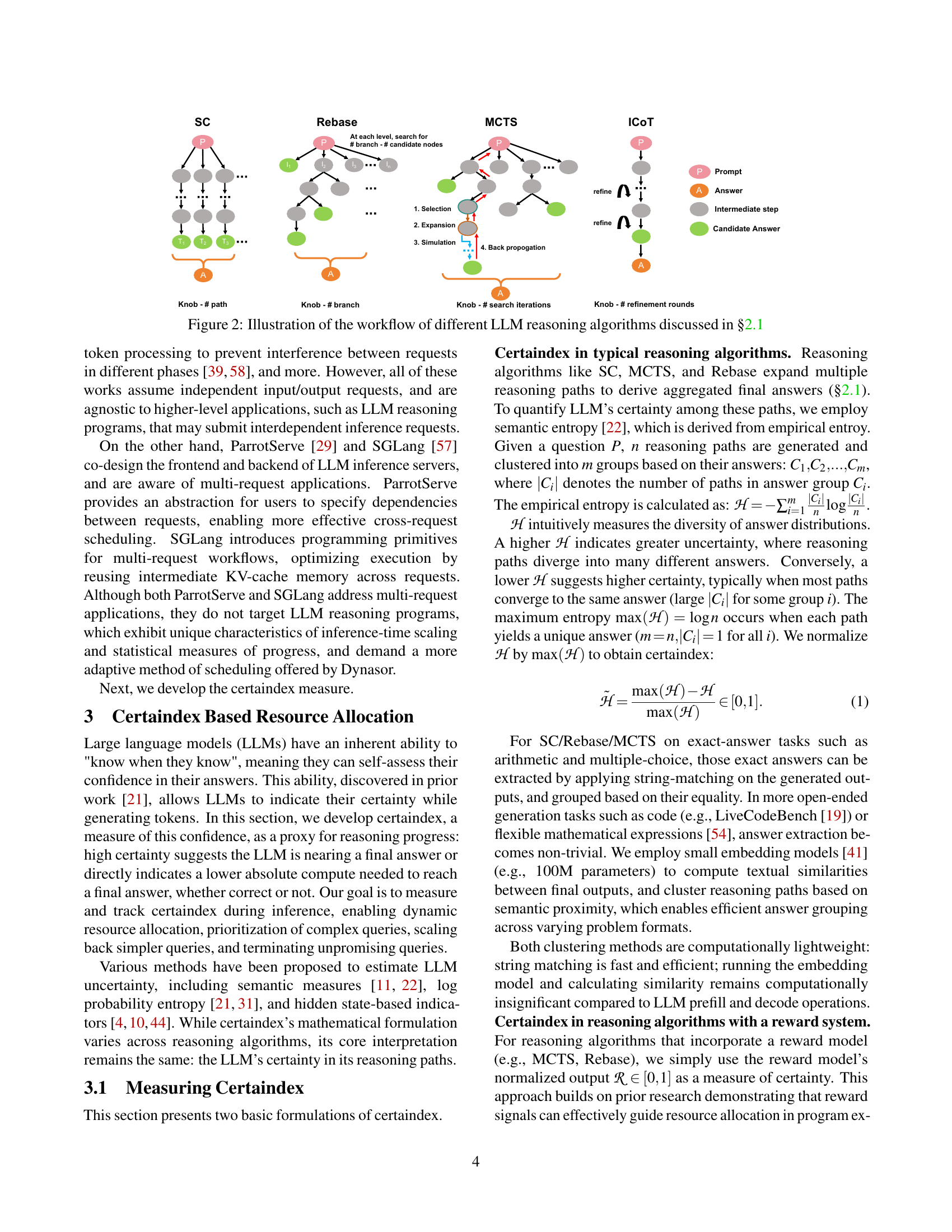

🔼 Figure 3 displays the correlation between the certainty of a large language model (LLM) during reasoning and the number of steps required to reach the solution. It presents 12 different plots, each representing a unique combination of reasoning algorithm (SC, Rebase, MCTS, ICoT), dataset (LiveCodeBench, GSM8K, ASDiv, GAME24), and LLM (Llama, Gemma, Phi, QWQ). Each plot shows the model’s certainty (certaindex) measured at a specific step, compared to the actual number of steps needed for a correct solution. The different ways of measuring certaindex are indicated on the y-axis labels for each plot. The orange and green lines represent different resource allocation strategies (threshold-based and curve fitting, respectively). Note that for all plots except those using MCTS, the data was averaged across multiple runs to reduce the impact of randomness.

read the caption

Figure 3: Correlations between certaindex strength (y-axis) and ground truth steps to solution (x-axis) on 12 (algorithm, task dataset, LLM) settings where algorithm ∈\in∈ {SC, Rebase, MCTS, ICoT}, dataset ∈\in∈ {LiveCodeBench [19], GSM8K, ASDiv [34], GAME24 [54]}, and LLM ∈\in∈ {Llama [33], Gemma [46], Phi [2], QWQ [47]}. How certaindex is measured in each setting is shown in the y𝑦yitalic_y label of each plot. Certaindex is measured at the reasoning step marked by the black line. The orange line indicates the thresholding-based allocation. The green line illustrates a more fine-grained approach through curve fitting. For all plots (except MCTS), both certaindex values and oracle steps were averaged across multiple runs to combat randomness.

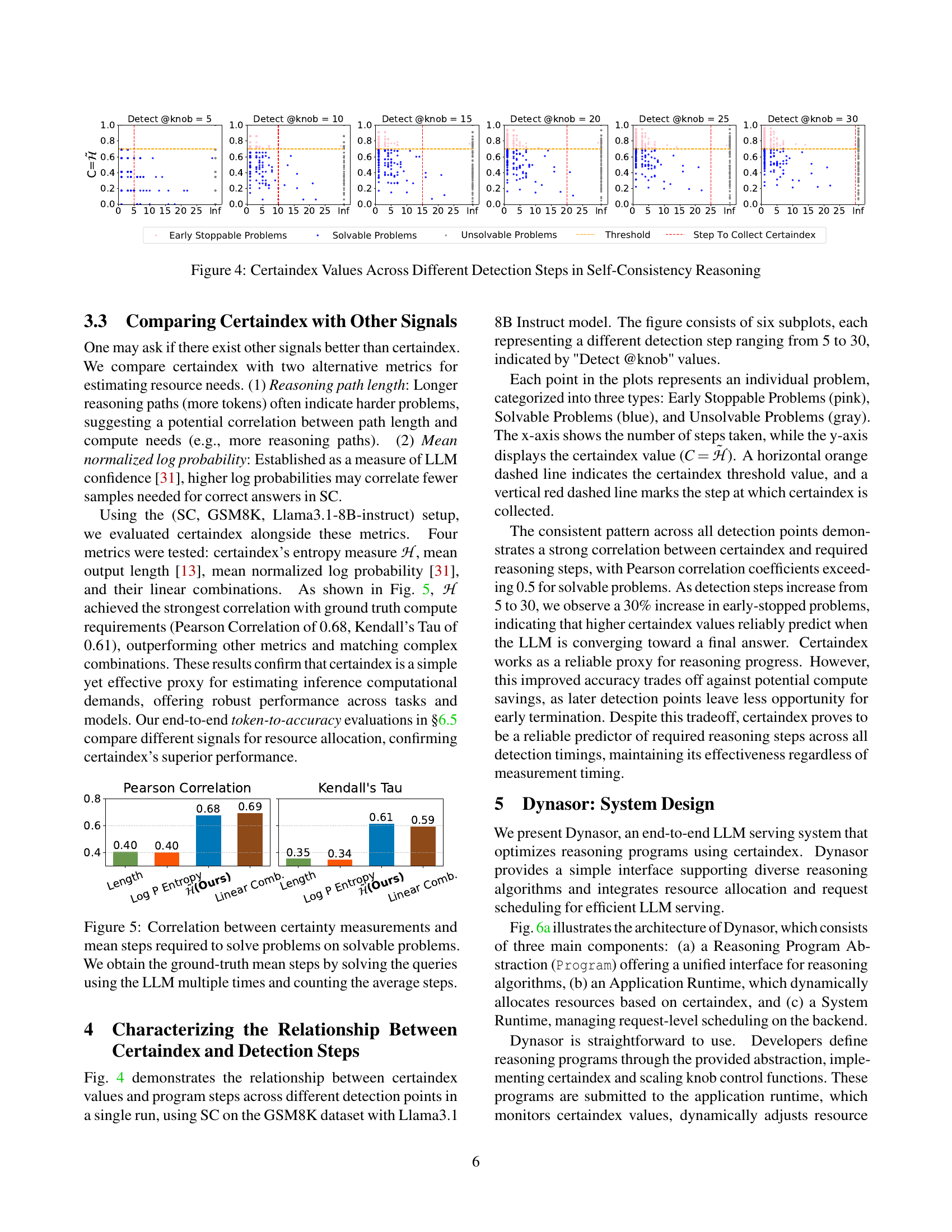

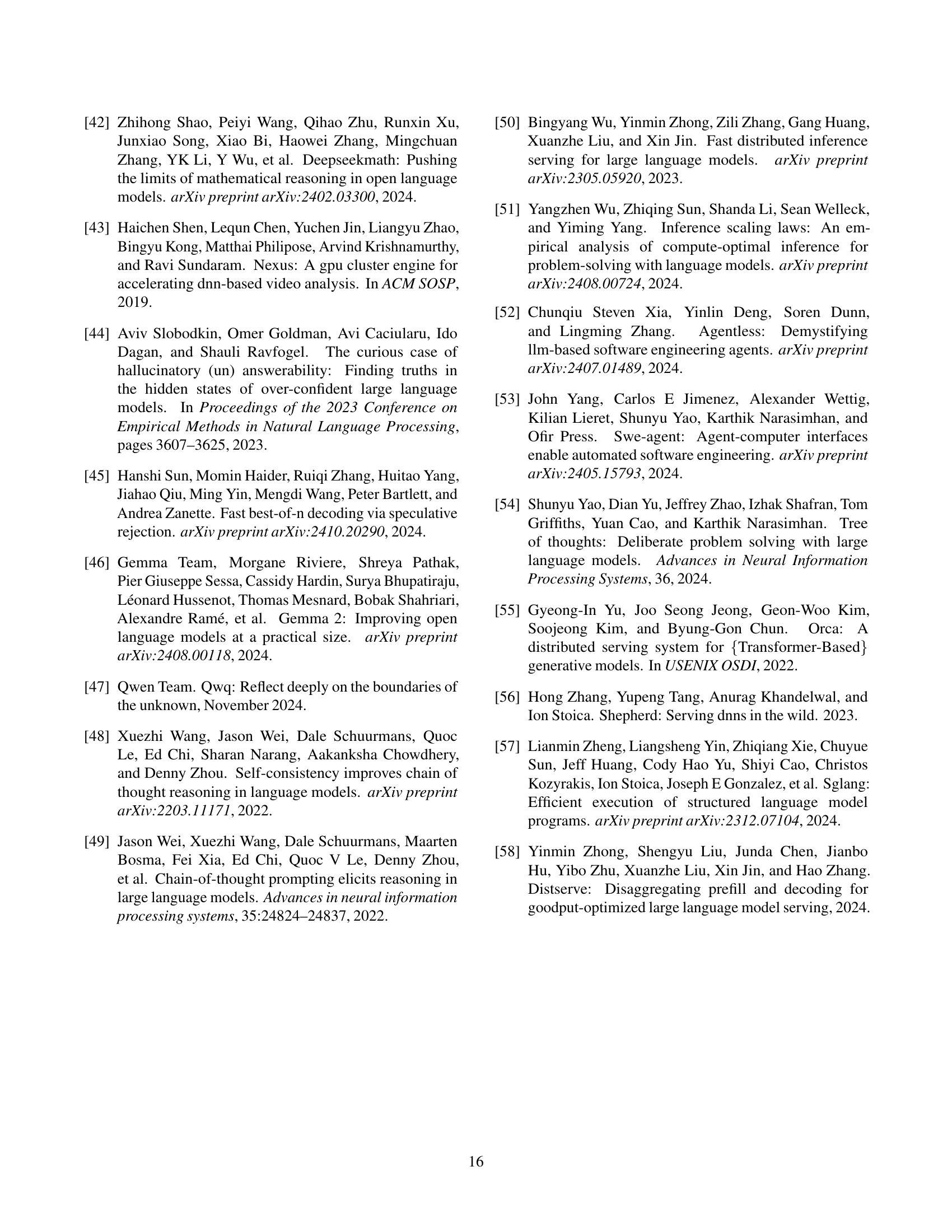

🔼 This figure visualizes how the Certaindex values change across different reasoning steps within the Self-Consistency algorithm. Each subplot represents a specific detection step (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30). Points in the plot represent individual problems, categorized into three types: Early Stoppable Problems, Solvable Problems, and Unsolvable Problems. The x-axis displays the number of steps, the y-axis shows the Certaindex values, a horizontal orange dashed line shows the threshold, and a vertical red dashed line shows the step at which Certaindex is collected. The consistent pattern demonstrates a strong correlation between Certaindex and the required reasoning steps, highlighting its effectiveness as a proxy for reasoning progress.

read the caption

Figure 4: Certaindex Values Across Different Detection Steps in Self-Consistency Reasoning

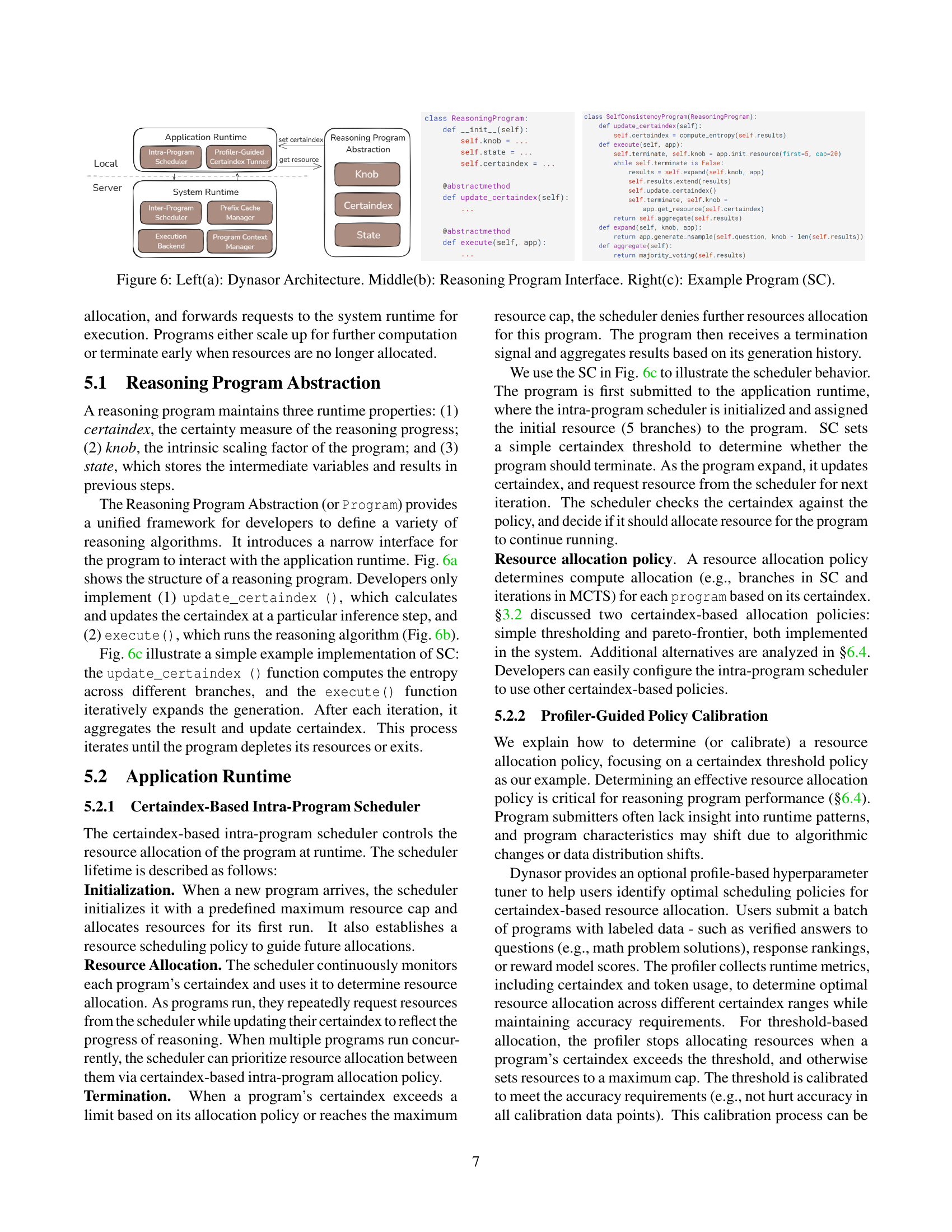

🔼 This figure displays the correlation between different metrics used to estimate the certainty of a large language model’s (LLM) answers and the actual number of steps required to obtain a correct solution. The metrics compared include: certaindex (based on entropy), mean output length, mean normalized log probability, and linear combinations of these. The ground-truth number of steps was determined by repeatedly solving the problems with the LLM and averaging the results. The figure demonstrates that certaindex (entropy-based) shows the strongest correlation with the true number of steps required to obtain the solution.

read the caption

Figure 5: Correlation between certainty measurements and mean steps required to solve problems on solvable problems. We obtain the ground-truth mean steps by solving the queries using the LLM multiple times and counting the average steps.

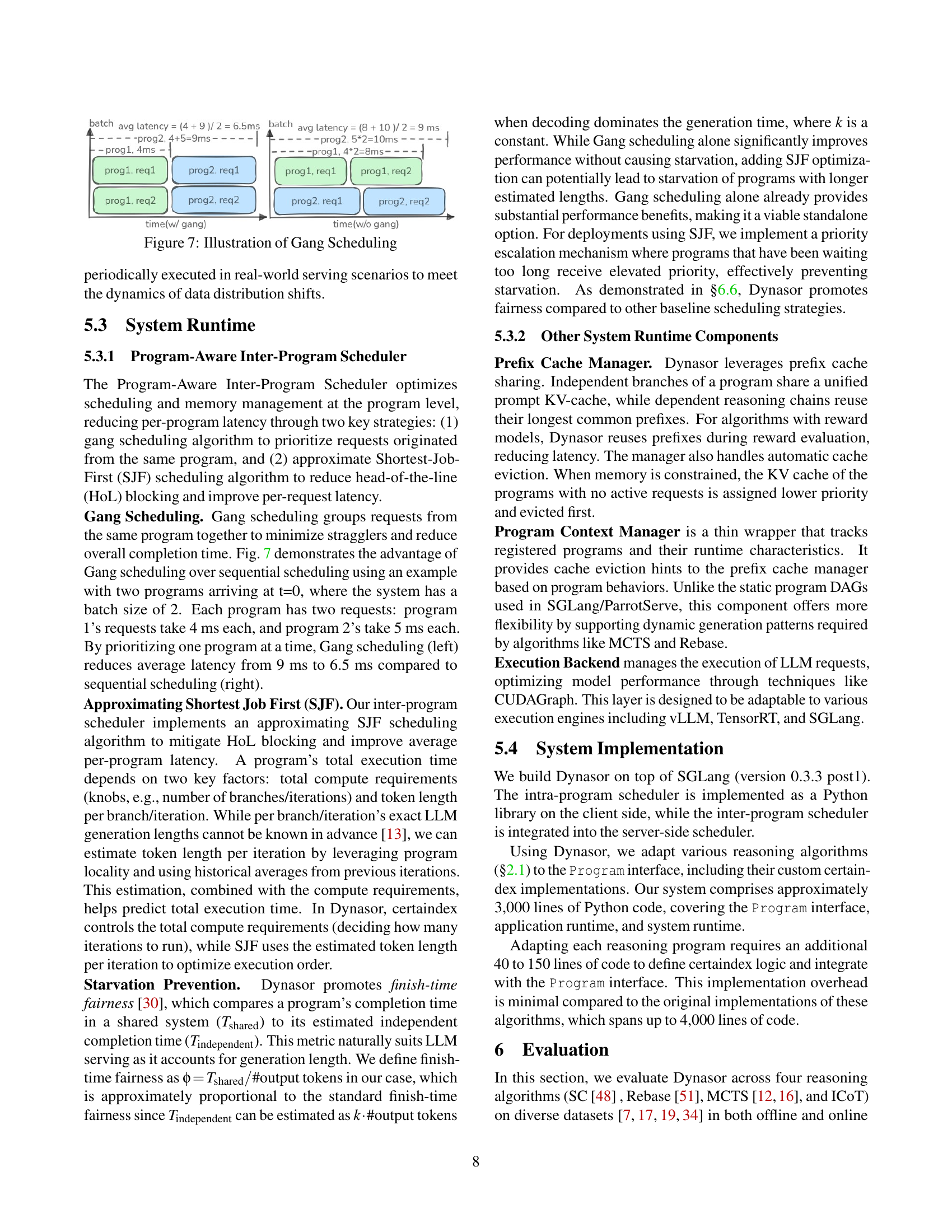

🔼 Figure 6 illustrates the Dynasor system architecture, which consists of three main parts: (a) Reasoning Program Abstraction, (b) Application Runtime, and (c) System Runtime. The Reasoning Program Abstraction provides a standardized interface for various reasoning algorithms, allowing them to interact with the Dynasor system seamlessly. The Application Runtime is responsible for resource allocation based on the ‘certaindex’ metric, which indicates the progress of the reasoning process. Finally, the System Runtime manages inter-program scheduling, ensuring efficient resource utilization and minimizing latency. The figure also includes a code example (c) showing the implementation of a self-consistency (SC) reasoning program within the Dynasor framework.

read the caption

Figure 6: Left(a): Dynasor Architecture. Middle(b): Reasoning Program Interface. Right(c): Example Program (SC).

🔼 This figure illustrates the benefit of gang scheduling in reducing average latency. It compares two scenarios: one using gang scheduling and another using standard sequential scheduling. Both scenarios involve two programs, each with two requests, that have varying processing times. In the gang scheduling scenario, requests from the same program are grouped together to minimize the impact of stragglers (longer-running requests), resulting in lower average latency. The sequential scheduling scenario processes requests one program at a time, leading to higher average latency due to delays caused by the longer-running requests from program 2.

read the caption

Figure 7: Illustration of Gang Scheduling

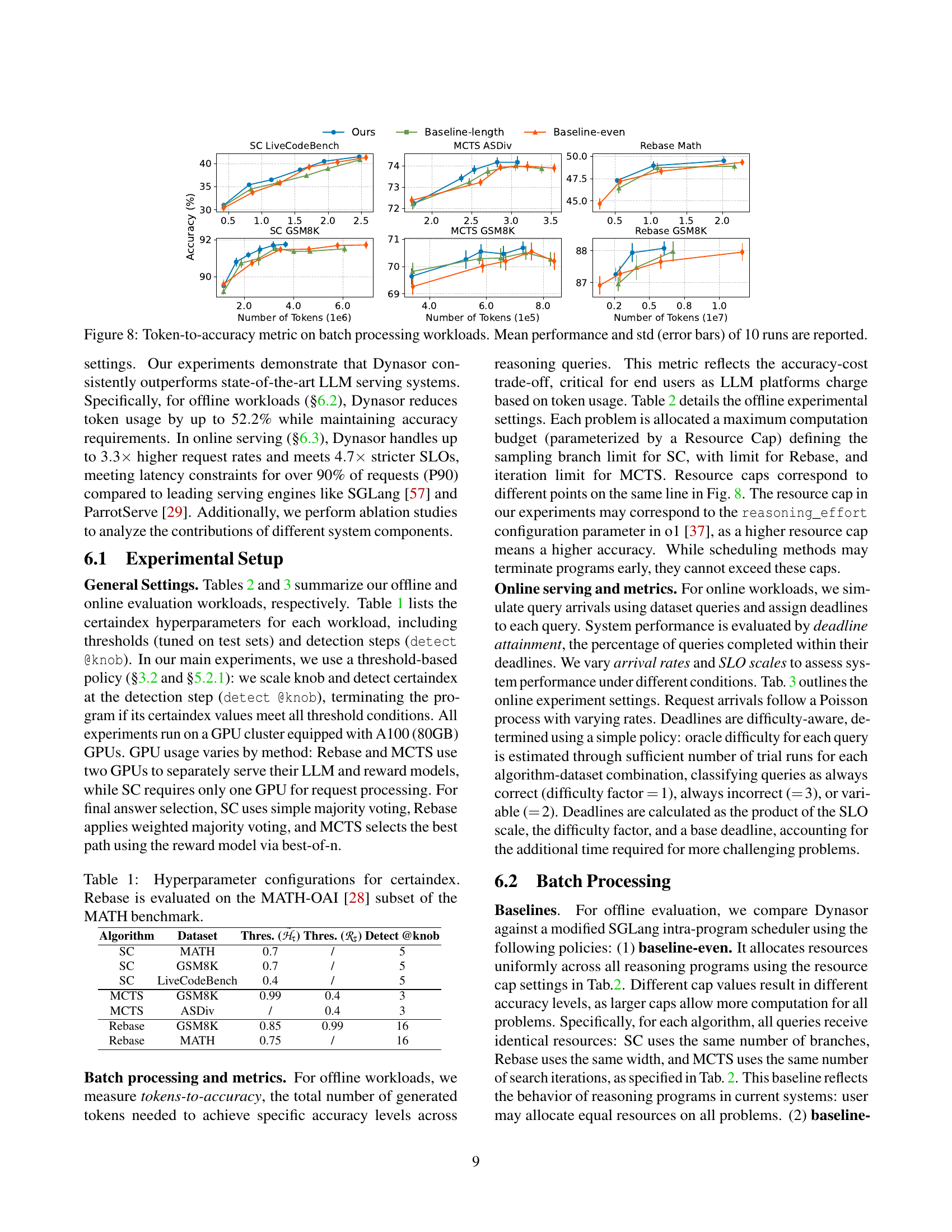

🔼 This figure displays the results of batch processing experiments, comparing the token usage efficiency of Dynasor against baseline methods. For various reasoning algorithms (Self-Consistency, Monte Carlo Tree Search, and Rebase) and datasets (GSM8K, LiveCodeBench, MATH), it shows the relationship between the number of tokens (x-axis) and the achieved accuracy (y-axis). Error bars represent the standard deviation across 10 runs. This allows for a direct comparison of the computational efficiency of Dynasor in achieving similar accuracy levels compared to allocating resources evenly or based on output length.

read the caption

Figure 8: Token-to-accuracy metric on batch processing workloads. Mean performance and std (error bars) of 10 runs are reported.

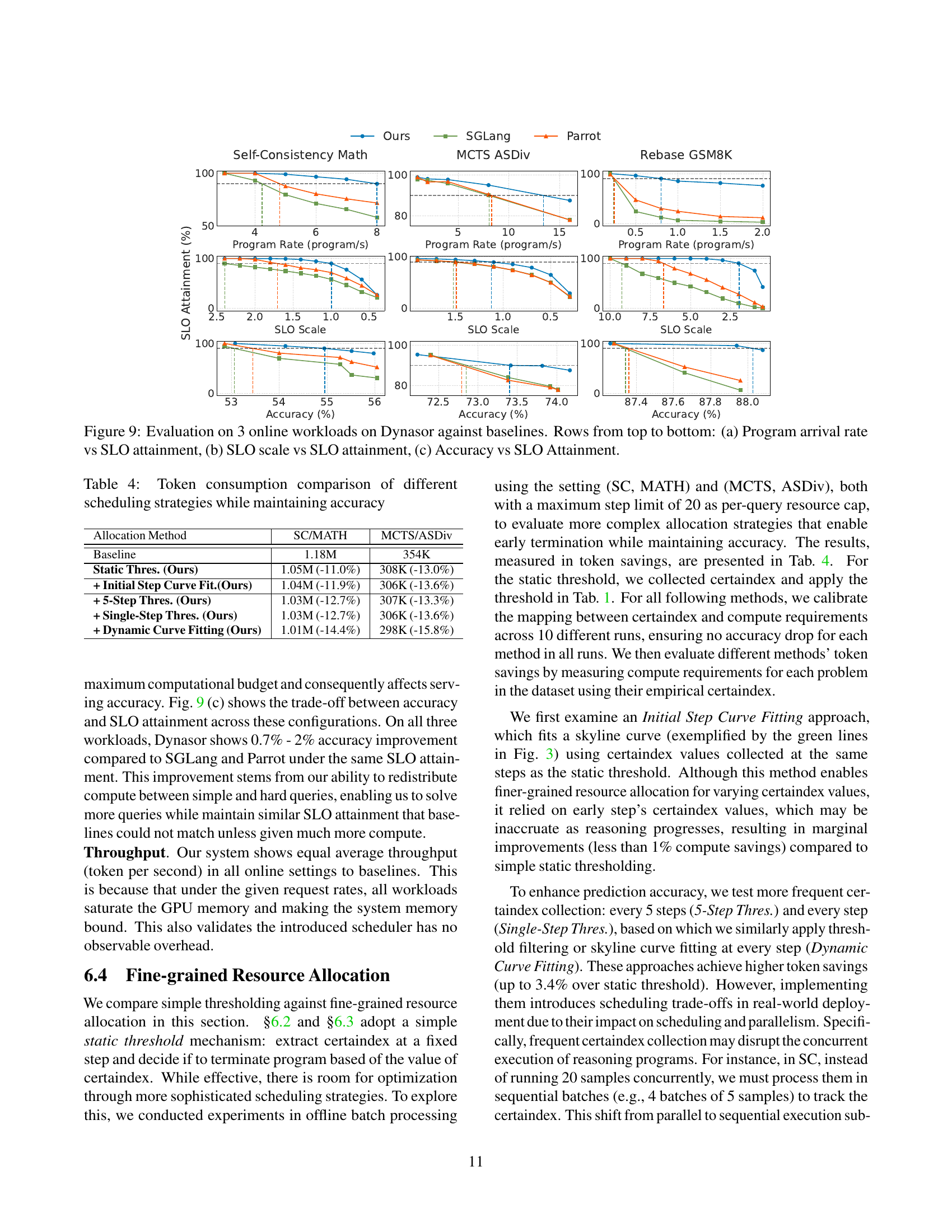

🔼 Figure 9 presents a comprehensive evaluation of Dynasor’s performance in online serving scenarios against two strong baselines: SGLang and ParrotServe. The figure is divided into three subplots, each illustrating a key performance trade-off in LLM reasoning query serving: (a) Program arrival rate vs. SLO attainment: This plot demonstrates Dynasor’s ability to sustain higher request arrival rates while meeting latency targets (SLOs). It shows the relationship between the number of incoming queries per second and the percentage of queries that meet their deadlines (SLO attainment). (b) SLO scale vs. SLO attainment: This subplot illustrates Dynasor’s ability to handle more stringent latency requirements (tighter SLOs). Here, the SLO attainment is shown as a function of the stringency of the latency constraints. (c) Accuracy vs. SLO attainment: This plot highlights the trade-off between accuracy and SLO attainment, showing how the achieved accuracy changes when we adjust the resource allocation to meet different SLO requirements. It examines whether prioritizing SLO attainment affects the overall accuracy of the query results. This plot shows how the attained accuracy changes when we adjust the resource allocation to meet different SLO requirements. All three subplots showcase Dynasor’s superiority over the baselines across diverse conditions, demonstrating its capacity to achieve high throughput, meet strict latency targets, and maintain high accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 9: Evaluation on 3 online workloads on Dynasor against baselines. Rows from top to bottom: (a) Program arrival rate vs SLO attainment, (b) SLO scale vs SLO attainment, (c) Accuracy vs SLO Attainment.

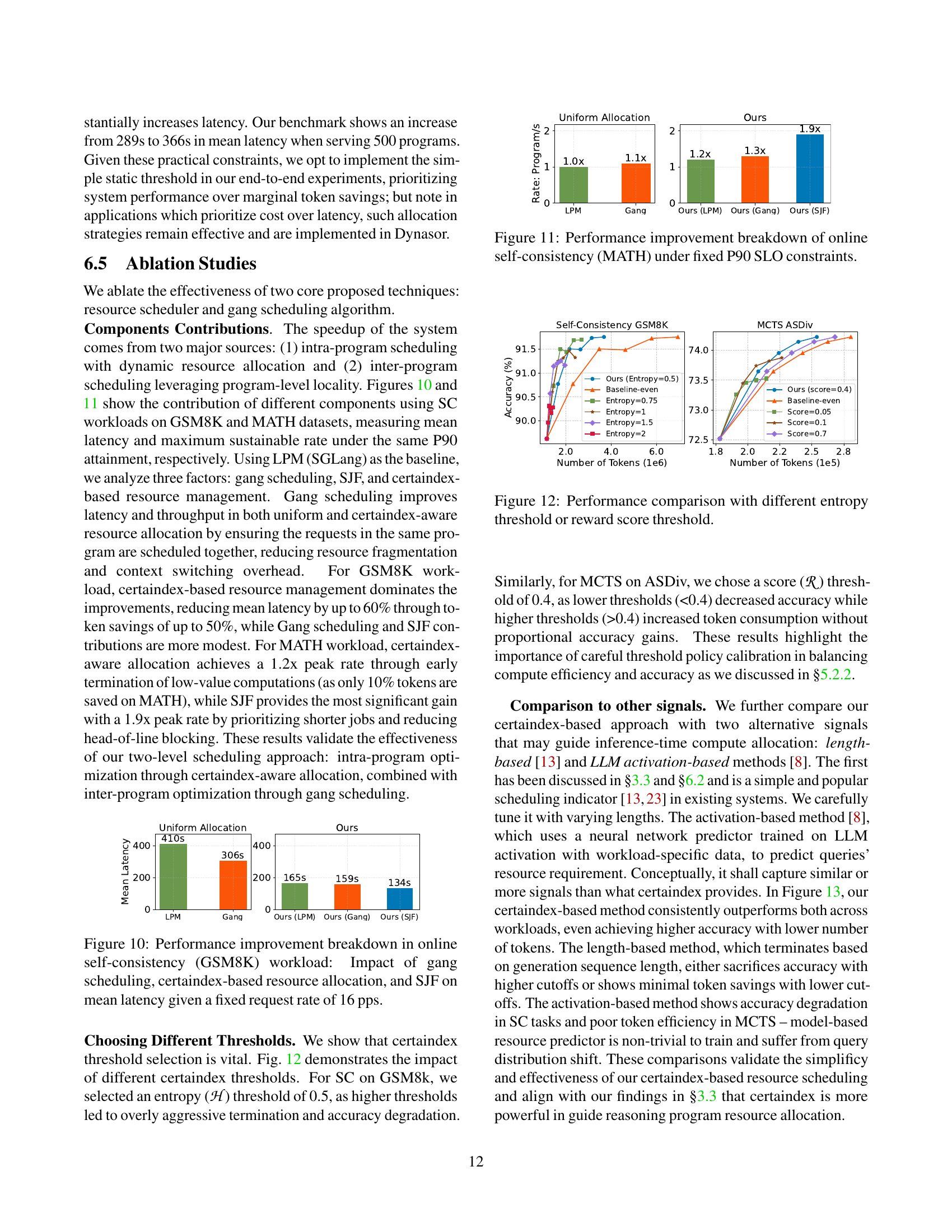

🔼 Figure 10 displays the impact of three key techniques in Dynasor on the mean latency of online self-consistency (SC) tasks using the GSM8K dataset. The experiment uses a fixed request rate of 16 programs per second (pps). The three techniques analyzed are gang scheduling, certaindex-based resource allocation, and the shortest-job-first (SJF) scheduling algorithm. Each bar represents the mean latency, allowing for a comparison of the baseline (using only Longest Prefix Matching from SGLang) against the performance gains achieved by incorporating each technique individually and in combination. This visualization helps to quantify the contribution of each component to Dynasor’s overall latency reduction.

read the caption

Figure 10: Performance improvement breakdown in online self-consistency (GSM8K) workload: Impact of gang scheduling, certaindex-based resource allocation, and SJF on mean latency given a fixed request rate of 16 pps.

🔼 Figure 11 shows the performance improvements achieved by Dynasor for online self-consistency tasks on the MATH dataset, focusing on maintaining the 90th percentile (P90) service level objective (SLO). It breaks down the contributions of three key components: Gang Scheduling, which groups requests from the same program for more efficient execution, SJF (Shortest Job First) scheduling for reducing latency, and the certaindex-based resource management. The bar chart compares the mean latency and maximum throughput (rate) of Dynasor with various combinations of these components against the baseline LPM (Longest Prefix Matching) scheduler from SGLang, demonstrating the synergistic benefits of combining these techniques.

read the caption

Figure 11: Performance improvement breakdown of online self-consistency (MATH) under fixed P90 SLO constraints.

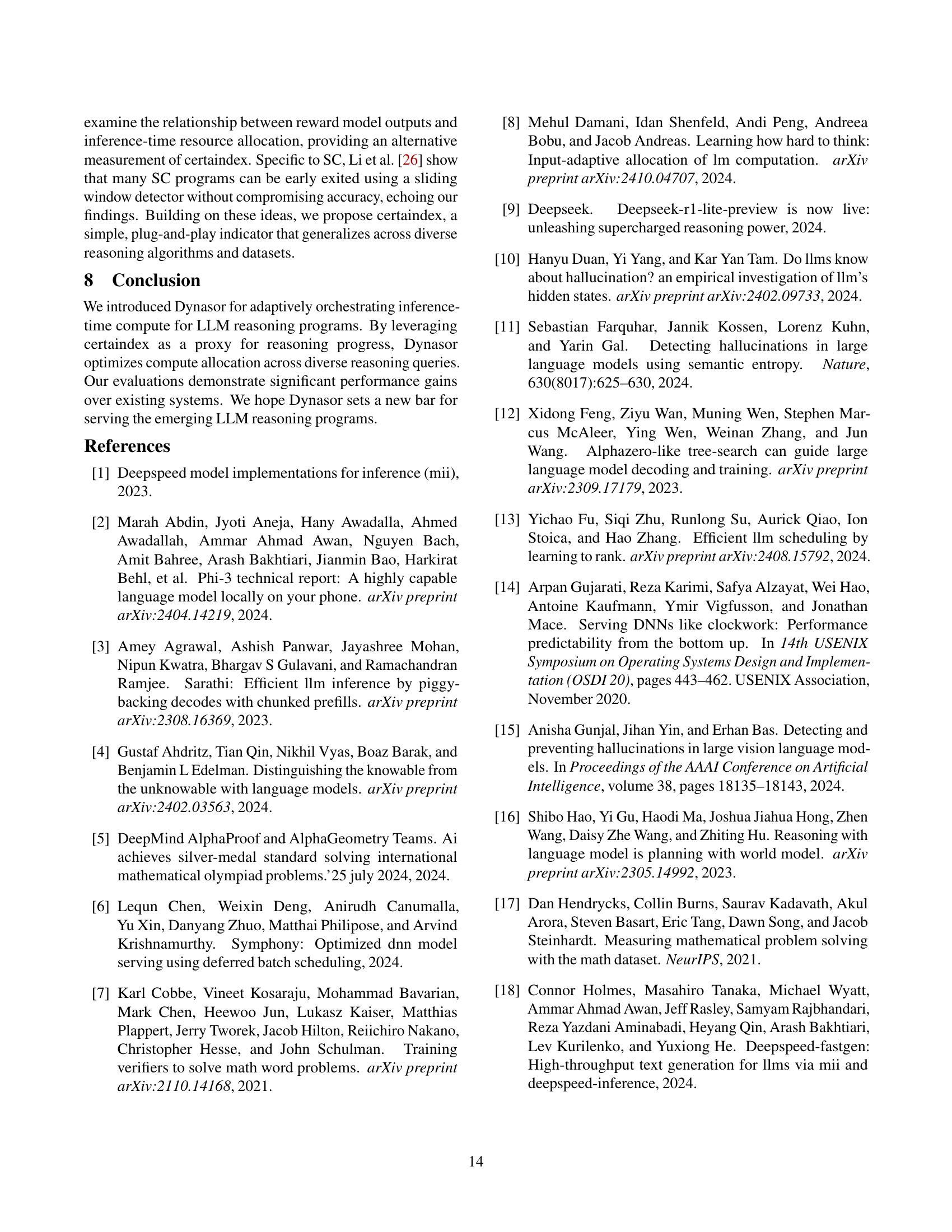

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different thresholding strategies for resource allocation in online serving. The x-axis represents the number of tokens used, and the y-axis represents the accuracy achieved. Different colored lines represent different methods: ‘Ours’ uses the proposed certaindex-based method, while ‘Baseline-even’ uses uniform resource allocation and ‘Entropy=0.75’, ‘Entropy=1’, ‘Entropy=1.5’, ‘Entropy=2’ represent variations on entropy-based thresholds. Similarly, ‘Ours (score=0.4)’, ‘Score=0.05’, ‘Score=0.1’, ‘Score=0.7’ show variations based on reward score thresholds, again compared to ‘Baseline-even’. The plots for Self-Consistency (GSM8K) and MCTS (ASDiv) illustrate the performance difference of these approaches on different algorithms and datasets. This shows the effectiveness and sensitivity of choosing appropriate certaindex thresholds.

read the caption

Figure 12: Performance comparison with different entropy threshold or reward score threshold.

🔼 Figure 13 compares the performance of Dynasor’s certaindex-based resource allocation with two alternative methods for managing inference-time compute in LLMs: using the length of generated sequences as a proxy for computational needs and using a neural network model to predict resource requirements based on LLM activations. The results are shown across two different tasks and models. The x-axis represents the number of generated tokens (compute), while the y-axis shows the achieved accuracy. This visualization demonstrates the superior performance of Dynasor’s certaindex method, achieving higher accuracy with fewer tokens than the other two methods.

read the caption

Figure 13: Performance comparison with LLM activation-based predictor and output length based scheduling.

🔼 This figure illustrates the fairness of Dynasor’s scheduling mechanism by comparing the ratio of latency to the number of tokens used. The baseline token count represents the number of tokens consumed when all programs utilize their maximum resources. The graph shows that Dynasor with both gang scheduling and the shortest job first (SJF) scheduling algorithm improves finish-time fairness significantly compared to the baseline, particularly for longer tasks.

read the caption

Figure 14: Finish-Time Fairness.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of Dynasor in optimizing the performance of the Qwen-QWQ language model. The original Qwen-QWQ model, due to its long chain-of-thought generation process, performs poorly under lower token limits, often failing to reach conclusions. Dynasor addresses this by implementing two strategies: ‘QWQ Guided’ breaks the generation into smaller chunks with intermediate ‘final answer’ prompts to improve the accuracy and reduce token consumption. ‘QWQ Cut’ adds a certaindex-based termination condition, allowing early termination of unpromising generations. This results in significant reduction of tokens, while maintaining accuracy comparable to the original model, demonstrating that Dynasor is capable of adapting to diverse LLMs and improving their efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 15: Serving Qwen-QWQ using Dynasor.

More on tables

| (Algo., Dataset, LLM) | Reward Model | # Samples | Resource Cap |

|---|---|---|---|

| (SC, LCB, Llama3.1 8B) | / | 400 | 5,10,15,20,25,30 |

| (SC, GSM8K, Llama3.1 8B) | / | 1000 | 5,10,15,20,25,30 |

| (MCTS, ASDiv, Llama2 7B) | Skywork 7B | 300 | 3,7,10,15,20 |

| (MCTS, GSM8K, Llama2 7B) | Skywork 7B | 300 | 3,7,10,15,20 |

| (Rebase, MATH, Llemma 7B) | Llemma 34b | 500 | 16,32,64,128 |

| (Rebase, GSM8K, Llemma 34B) | Llemma 34b | 500 | 16,32,64,128 |

🔼 This table details the configurations used for offline experiments in the paper. It lists the algorithm used (SC, MCTS, Rebase), the dataset employed (LiveCodeBench, GSM8K, ASDiv, MATH), the specific large language model (LLM) and reward model used (Llama, Skywork, Llemma), the reward model hyperparameters, the number of samples used, and the resource cap (maximum computation budget) for each experimental setting. The different resource caps correspond to various points on the token-to-accuracy curves shown in Figure 8. This allows for the comparison of different computational budgets and the impact on accuracy across various algorithms and datasets.

read the caption

Table 2: Offline workload Configurations. LiveCodeBench (LCB), Llama2 7B [12], Skywork7B [35], Llemma 7B and 34B [51] are fine-tuned models used in different settings as LLM/reward model.

| Algorithm | Dataset | LLM | Reward Model | Base Deadline (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | MATH | Llama3.1 8B | / | 240 |

| MCTS | ASDiv | Llama2 7B | Skywork 7B | 60 |

| Rebase | GSM8K | Llemma 34B | Llemma 34b | 300 |

🔼 This table details the configurations used in the online evaluation of the Dynasor system. It lists the specific algorithms (Self-Consistency, Monte Carlo Tree Search, and Rebase), datasets (GSM8K, ASDiv), and large language models (LLMs and reward models) used in each experimental setting. Importantly, it also specifies the base deadline (in seconds) used for each configuration, providing context for the online serving performance evaluation.

read the caption

Table 3: Online workload Configurations

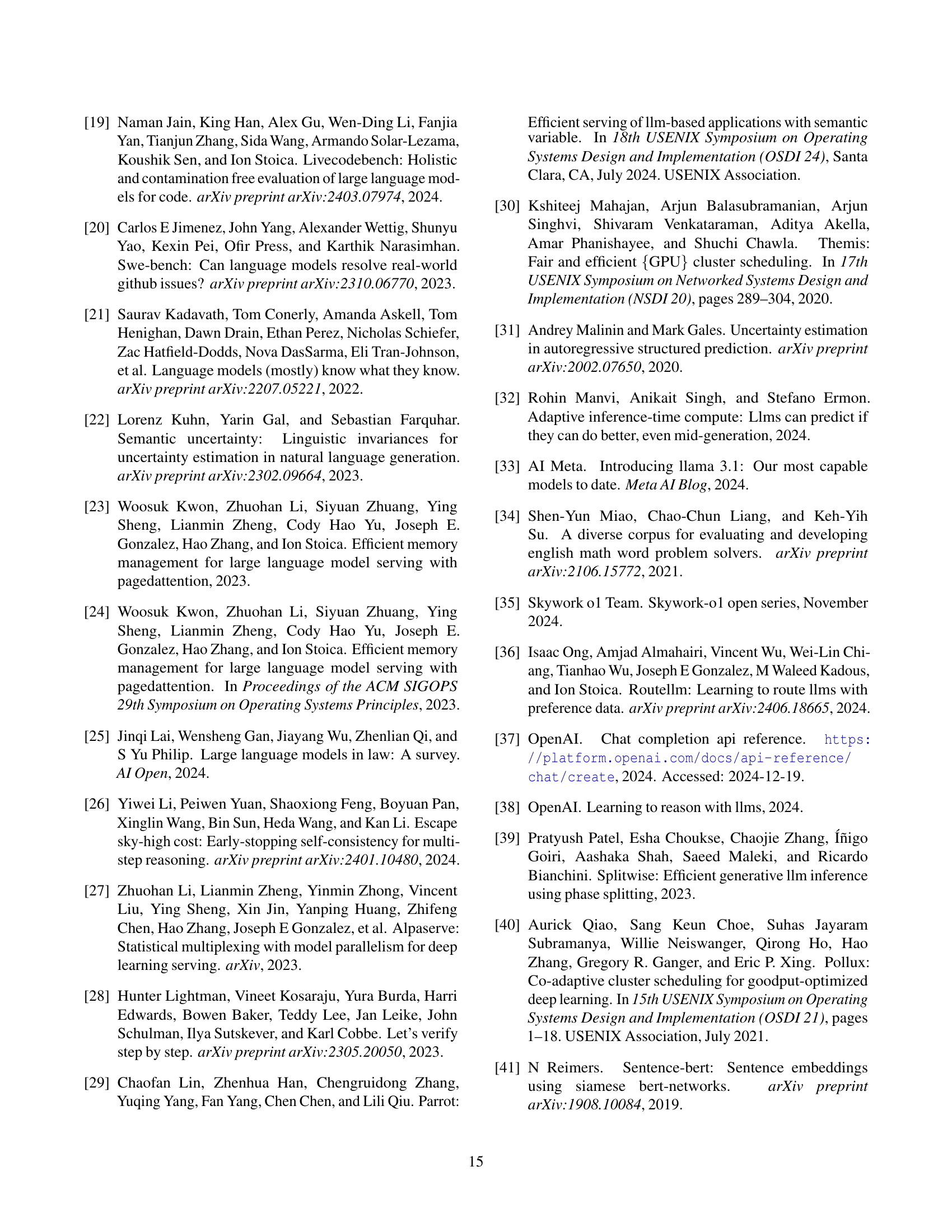

| Allocation Method | SC/MATH | MCTS/ASDiv |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1.18M | 354K |

| Static Thres. (Ours) | 1.05M (-11.0%) | 308K (-13.0%) |

| + Initial Step Curve Fit.(Ours) | 1.04M (-11.9%) | 306K (-13.6%) |

| + 5-Step Thres. (Ours) | 1.03M (-12.7%) | 307K (-13.3%) |

| + Single-Step Thres. (Ours) | 1.03M (-12.7%) | 306K (-13.6%) |

| + Dynamic Curve Fitting (Ours) | 1.01M (-14.4%) | 298K (-15.8%) |

🔼 This table compares the token consumption of various scheduling strategies for two different reasoning tasks: self-consistency on the MATH dataset and Monte Carlo Tree Search on the ASDiv dataset. It shows the token usage under different methods: the baseline (no optimization), a static threshold approach (Dynasor’s core method), a refined approach combining initial step curve fitting, a 5-step threshold approach, a single-step threshold approach, and a dynamic curve fitting approach. The goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of Dynasor’s fine-grained resource allocation compared to simpler scheduling approaches, while maintaining the same level of accuracy for each method.

read the caption

Table 4: Token consumption comparison of different scheduling strategies while maintaining accuracy

Full paper#