↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current language model based software engineering agents are limited by proprietary models and a lack of suitable training environments that reflect real-world challenges. Existing datasets either lack executable environments, reward signals, or contain unrealistic synthetic instructions. This paper introduces SWE-Gym, the first publicly-available training environment that combines real-world software engineering tasks, executable environments, and reward signals. SWE-Gym contains 2,438 real-world Python task instances sourced from popular open-source repositories.

The researchers use SWE-Gym to train language model based software engineering agents, achieving up to 19% absolute gains in resolve rate on popular benchmarks. They also demonstrate inference-time scaling through verifiers trained on agent trajectories. Combining fine-tuned agents with verifiers, they achieve a new state-of-the-art performance. To facilitate further research, they publicly release SWE-Gym, models, and agent trajectories.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces SWE-Gym, the first open-source environment for training software engineering agents. This addresses the critical need for robust training data in the field, enabling researchers to develop more effective AI tools for software development and significantly advancing research in this area. The work’s focus on real-world problems and publicly available resources ensures broad impact and accessibility.

Visual Insights#

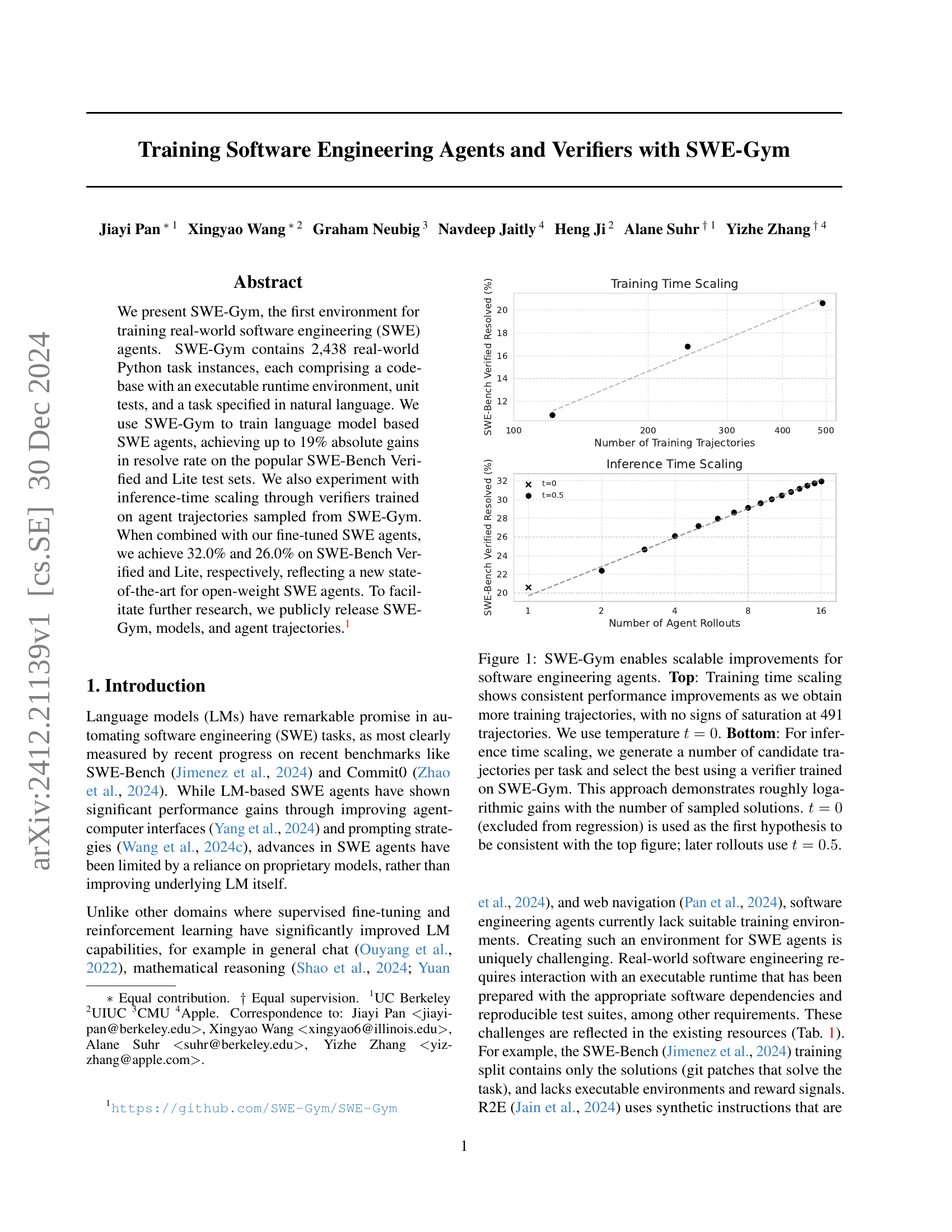

🔼 This figure demonstrates the scalability of improvements achieved using SWE-Gym for software engineering agents. The top panel shows training time scaling, illustrating consistent performance gains with an increasing number of training trajectories, even up to 491 trajectories without any sign of saturation. A temperature of 0 was used during training. The bottom panel displays inference time scaling, showcasing approximately logarithmic performance increases as the number of candidate trajectories per task increases. A verifier, trained using SWE-Gym, selects the best trajectory. While a temperature of 0 is used for the initial hypothesis to maintain consistency with the top panel, subsequent rollouts utilize a temperature of 0.5.

read the caption

Figure 1: SWE-Gym enables scalable improvements for software engineering agents. Top: Training time scaling shows consistent performance improvements as we obtain more training trajectories, with no signs of saturation at 491 trajectories. We use temperature t=0𝑡0t=0italic_t = 0. Bottom: For inference time scaling, we generate a number of candidate trajectories per task and select the best using a verifier trained on SWE-Gym. This approach demonstrates roughly logarithmic gains with the number of sampled solutions. t=0𝑡0t=0italic_t = 0 (excluded from regression) is used as the first hypothesis to be consistent with the top figure; later rollouts use t=0.5𝑡0.5t=0.5italic_t = 0.5.

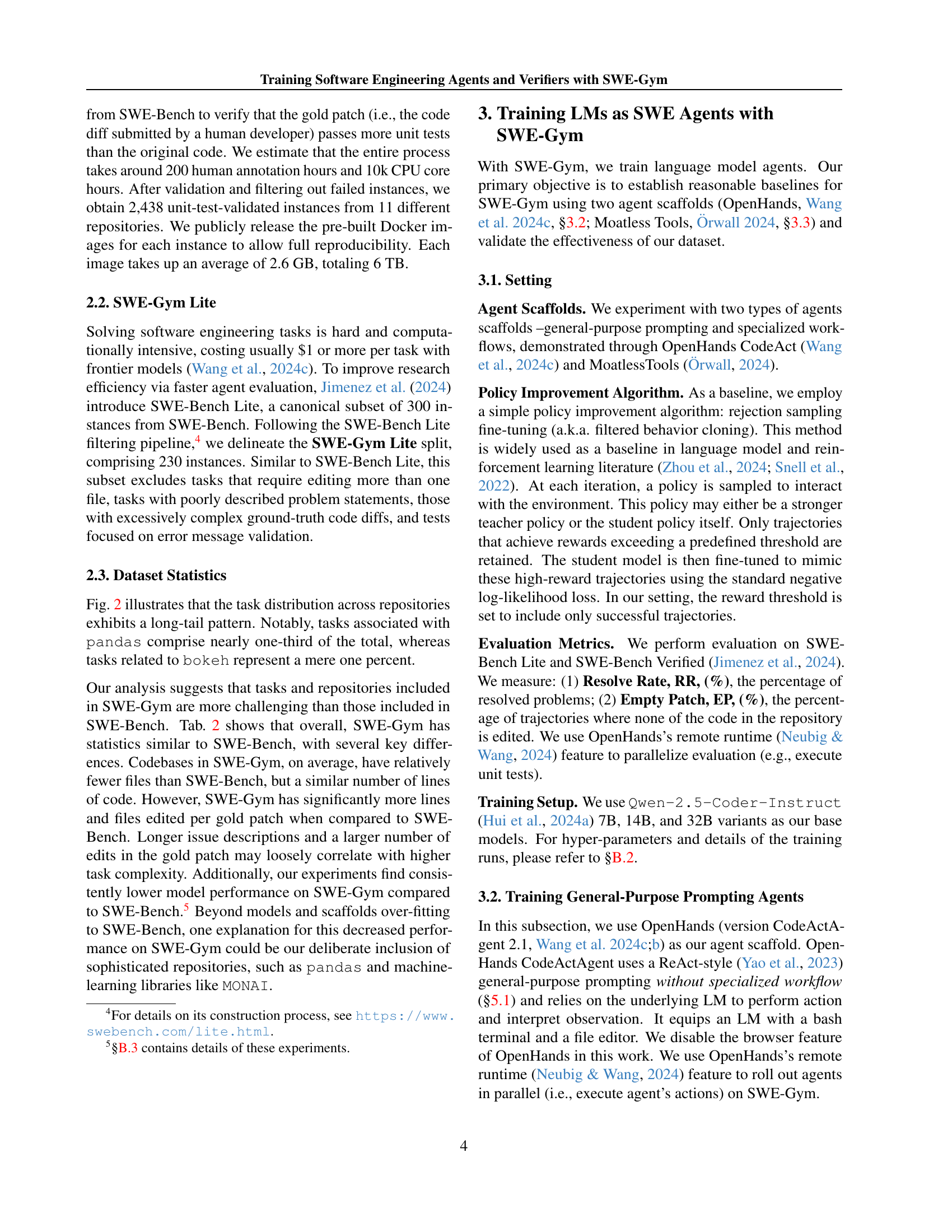

| Dataset (split) | Repository-Level | Executable Environment | Real task | # Instances (total) | # Instances (train) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CodeFeedback (Zheng et al., 2024b) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 66,383 | 66,383 |

| APPS (Hendrycks et al., 2021a) | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 10,000 | 5,000 |

| HumanEval (Chen et al., 2021) | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 164 | 0 |

| MBPP (Tao et al., 2024) | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 974 | 374 |

| R2E (Jain et al., 2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 246 | 0 |

| SWE-Bench (train) (Jimenez et al., 2024) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 19,008 | 19,008 |

| SWE-Gym Raw | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 66,894 | 66,894 |

| SWE-Bench (test) (Jimenez et al., 2024) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,294 | 0 |

| SWE-Gym | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2,438 | 2,438 |

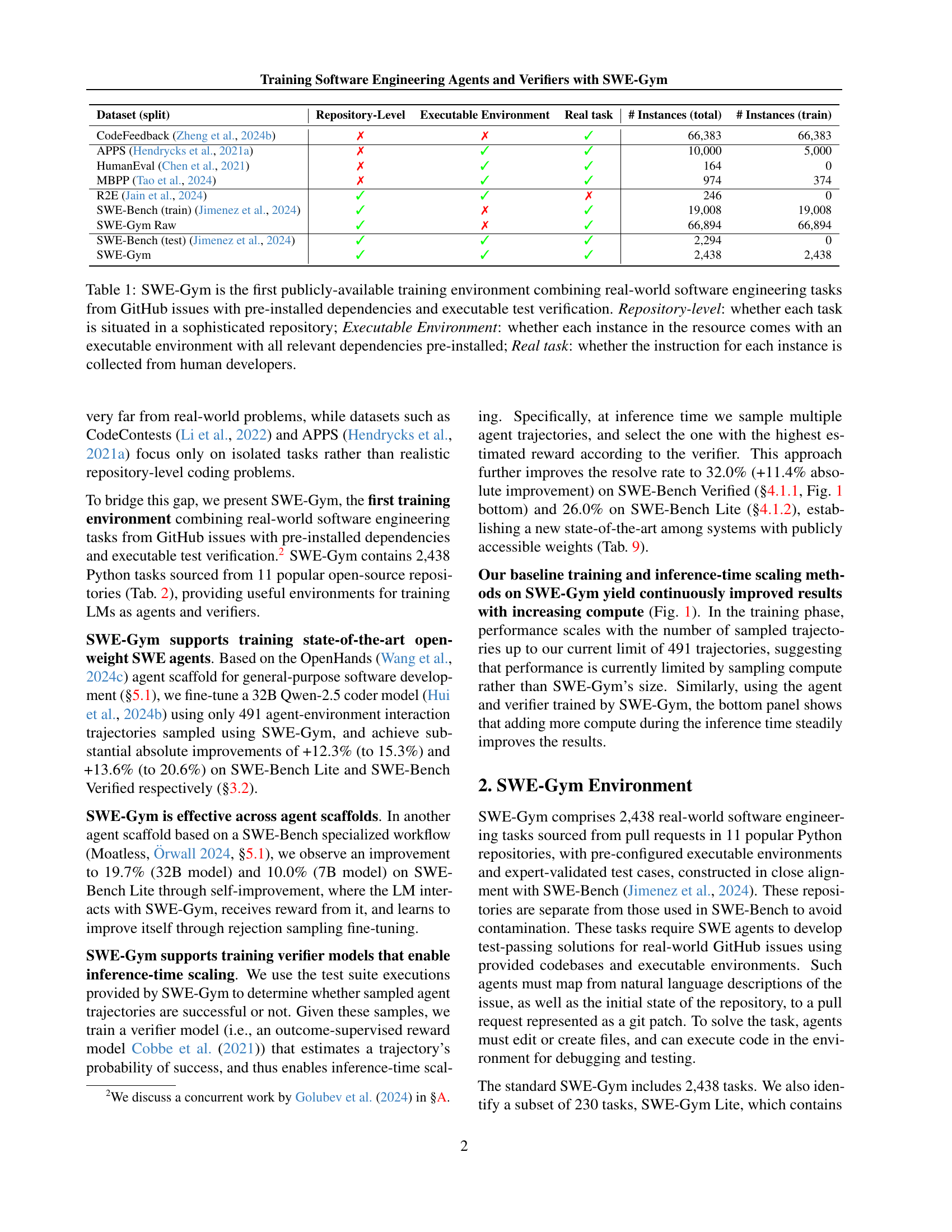

🔼 SWE-Gym is the first publicly available dataset for training software engineering agents. This table compares SWE-Gym to other datasets, highlighting key features such as whether tasks originate from sophisticated repositories, include executable environments with pre-installed dependencies, and use instructions written by human developers. It shows SWE-Gym’s unique combination of these features, making it superior for training real-world software engineering agents.

read the caption

Table 1: SWE-Gym is the first publicly-available training environment combining real-world software engineering tasks from GitHub issues with pre-installed dependencies and executable test verification. Repository-level: whether each task is situated in a sophisticated repository; Executable Environment: whether each instance in the resource comes with an executable environment with all relevant dependencies pre-installed; Real task: whether the instruction for each instance is collected from human developers.

In-depth insights#

SWE-Gym: A New Env#

The heading “SWE-Gym: A New Env” suggests a research paper introducing a novel software engineering training environment. SWE-Gym likely provides a realistic and comprehensive simulation of real-world software development tasks, allowing researchers to train and evaluate software agents in a more controlled setting compared to real-world scenarios. The “New Env” portion implies that this environment offers significant improvements or unique features not found in existing tools. This could include a more realistic problem representation, integration with actual development tools, the use of executable code evaluation, or the availability of large, high-quality datasets of software engineering tasks. The paper likely focuses on the design, implementation, and evaluation of SWE-Gym’s capabilities, demonstrating how it addresses limitations of previous approaches. Key aspects would be the benchmark tasks used, agent performance metrics employed, and the reproducibility of the environment. The overall contribution is likely to advance research in the area of automated software engineering and AI-powered development tools.

Agent Training#

The agent training process, a crucial aspect of the research, focuses on using a novel environment, SWE-Gym, to train language models as software engineering agents. SWE-Gym’s real-world task instances, complete with executable environments and test suites, provide a significant advantage over previous methods that relied on synthetic or incomplete data. The training leverages reinforcement learning techniques, specifically rejection sampling, to improve agent performance. The use of two agent scaffolds, OpenHands and MoatlessTools, demonstrates the approach’s adaptability to different workflows. Furthermore, the training data itself is investigated, with studies showing the importance of balanced datasets and the impact of data scaling methods on final agent capability. Results indicate that training on SWE-Gym leads to substantial improvements in the agent’s ability to solve real-world software engineering problems, pushing the state-of-the-art for open-weight SWE agents. The scalability of the training process, showing continuous improvement with increased compute, is also highlighted as a key finding.

Verifier Approach#

The effectiveness of the proposed SWE-Gym environment is significantly enhanced by a novel verifier approach. This approach leverages the power of machine learning to evaluate the quality of agent-generated solutions. By training a verifier model on agent trajectories from SWE-Gym, the system gains the ability to distinguish between successful and unsuccessful solutions. This is crucial because it enables inference-time scaling, allowing the system to sample multiple solutions and select the optimal one based on the verifier’s assessment. The verifier’s capacity to accurately predict success probabilities significantly boosts overall system performance. The integration of the verifier demonstrates a systematic improvement over simpler methods and highlights the importance of utilizing learned models for robust evaluation in complex software engineering tasks. This method directly addresses the challenges of evaluating solution quality, a key limitation in existing benchmarks that use human evaluation or less sophisticated techniques. Furthermore, continuous improvements in both training and inference time scaling are shown as more compute is utilized.

Scalable Training#

The concept of “Scalable Training” in the context of AI models for software engineering is crucial for practical applications. The paper highlights the need to move beyond limited datasets and resource-intensive training methods. Efficient training is achieved by leveraging a new environment, SWE-Gym, that contains a large number of real-world software engineering tasks. This scalability is demonstrated through consistent performance gains with increasing amounts of training data, showing that the environment’s size isn’t a bottleneck. The training process also demonstrates scalability through the use of sampling techniques. Multiple trajectories are generated and the best solution is selected, highlighting effective inference-time scaling through verification models. This strategy shows considerable promise for balancing resource allocation with performance gains. Overall, the focus on scalable training underscores the significance of creating practical AI systems that can be deployed and utilized effectively in real-world software engineering scenarios.

Future Directions#

Future research should focus on enhancing the scalability and robustness of SWE-Gym. This includes expanding the dataset to encompass a wider range of programming languages, project sizes, and development styles. Improving the efficiency of environment setup is crucial to reduce the computational overhead and facilitate broader adoption. The development of more sophisticated verifier models, capable of handling complex scenarios and providing more nuanced feedback, is essential. Investigating advanced training methodologies like reinforcement learning, which may prove more effective in handling the inherent complexity of SWE tasks, would be valuable. Finally, exploring the use of SWE-Gym in different areas, such as security testing and code generation, should be considered to broaden its impact on software engineering research and development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

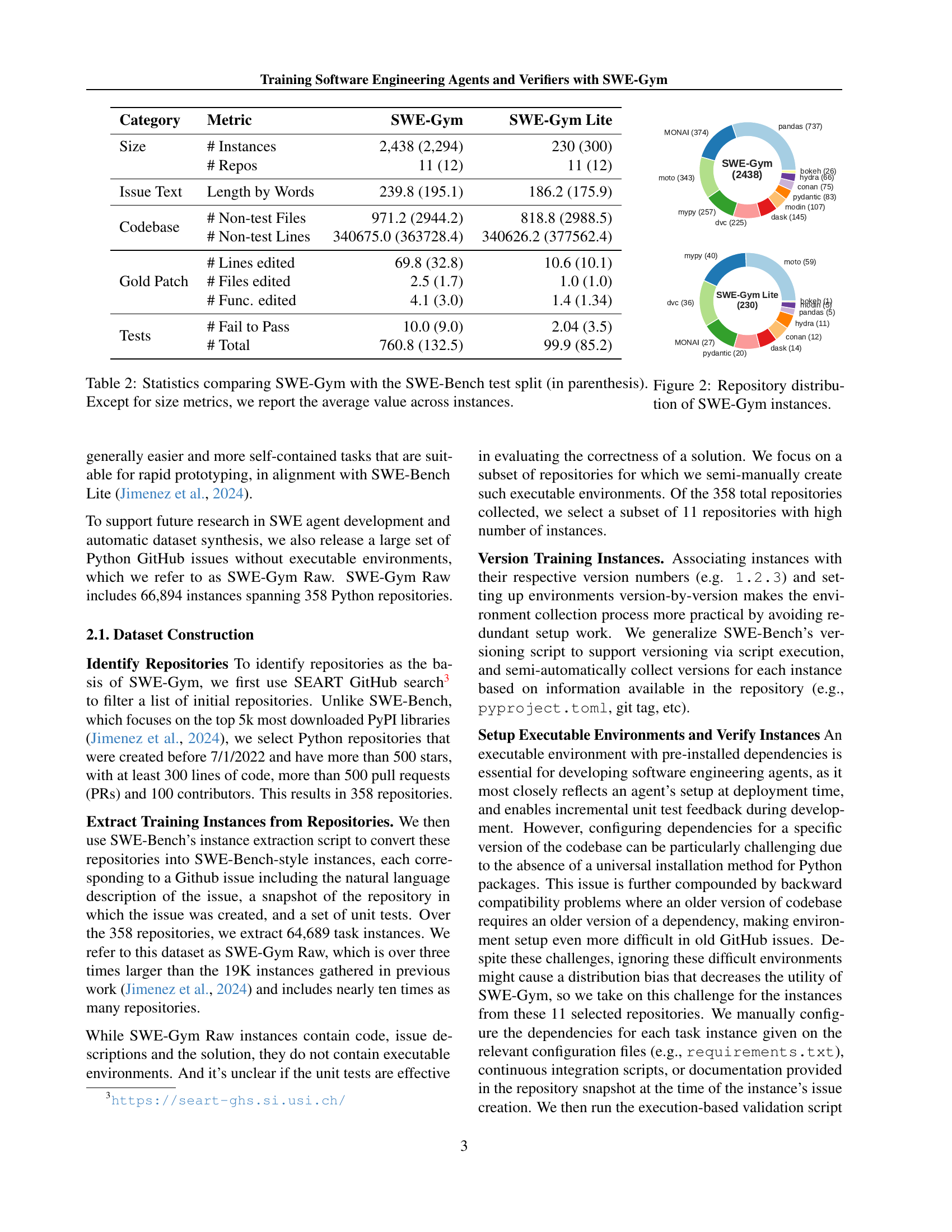

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of the 2,438 Python software engineering tasks in SWE-Gym across 11 different open-source repositories. The size of each repository’s representation in the chart visually corresponds to the number of tasks sourced from it. This illustrates the diversity of projects represented within SWE-Gym and highlights the prevalence of certain repositories (such as pandas) compared to others.

read the caption

Figure 2: Repository distribution of SWE-Gym instances.

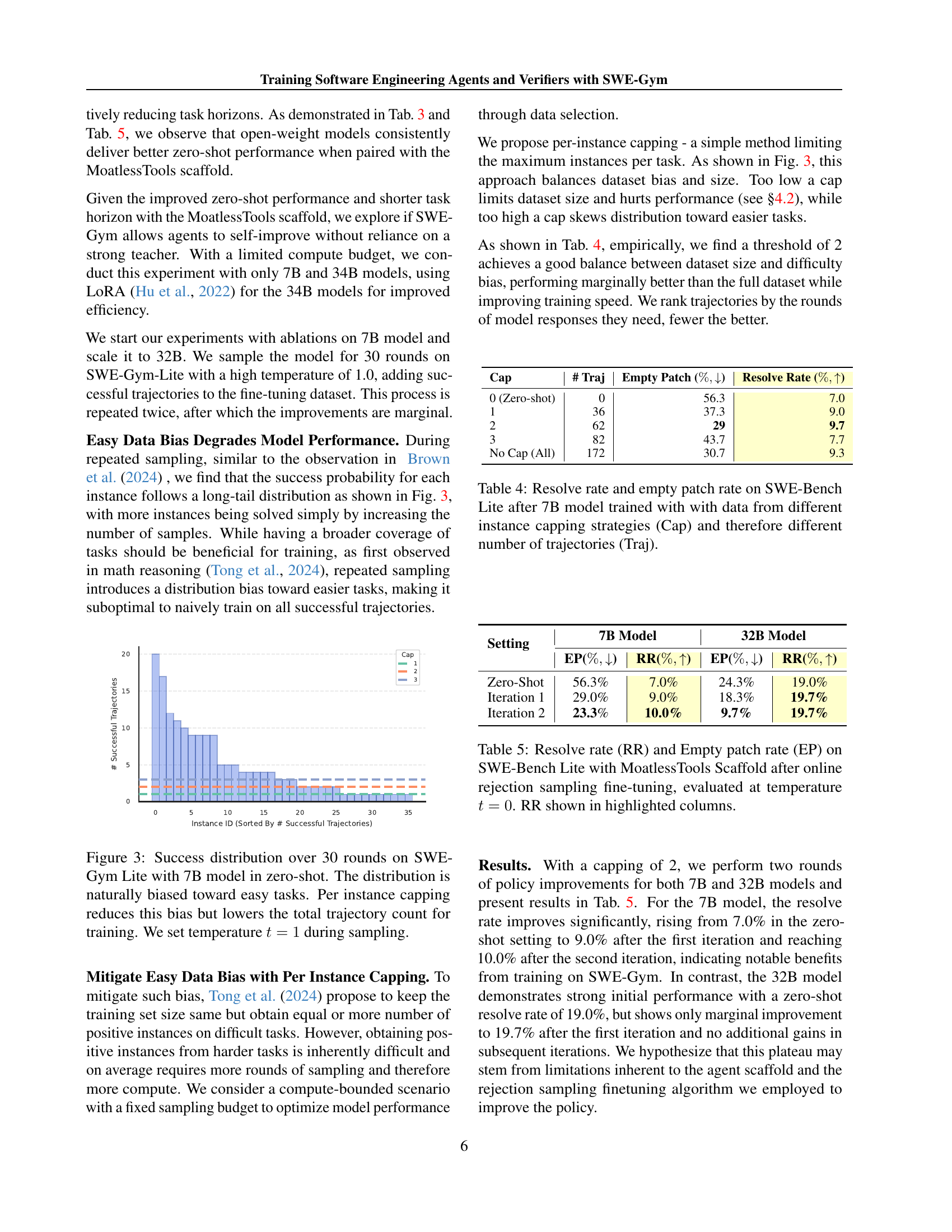

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of successful trajectories over 30 rounds of sampling for a 7B model on the SWE-Gym Lite dataset. The zero-shot setting reveals a long-tail distribution, indicating a bias towards easier tasks. The x-axis shows the number of successful trajectories for each task, while the y-axis represents the number of tasks with that many successful trajectories. The authors highlight how ‘per-instance capping’ (limiting the number of successful attempts per task) mitigates the bias towards easy tasks. However, this method also decreases the total number of trajectories available for training.

read the caption

Figure 3: Success distribution over 30 rounds on SWE-Gym Lite with 7B model in zero-shot. The distribution is naturally biased toward easy tasks. Per instance capping reduces this bias but lowers the total trajectory count for training. We set temperature t=1𝑡1t=1italic_t = 1 during sampling.

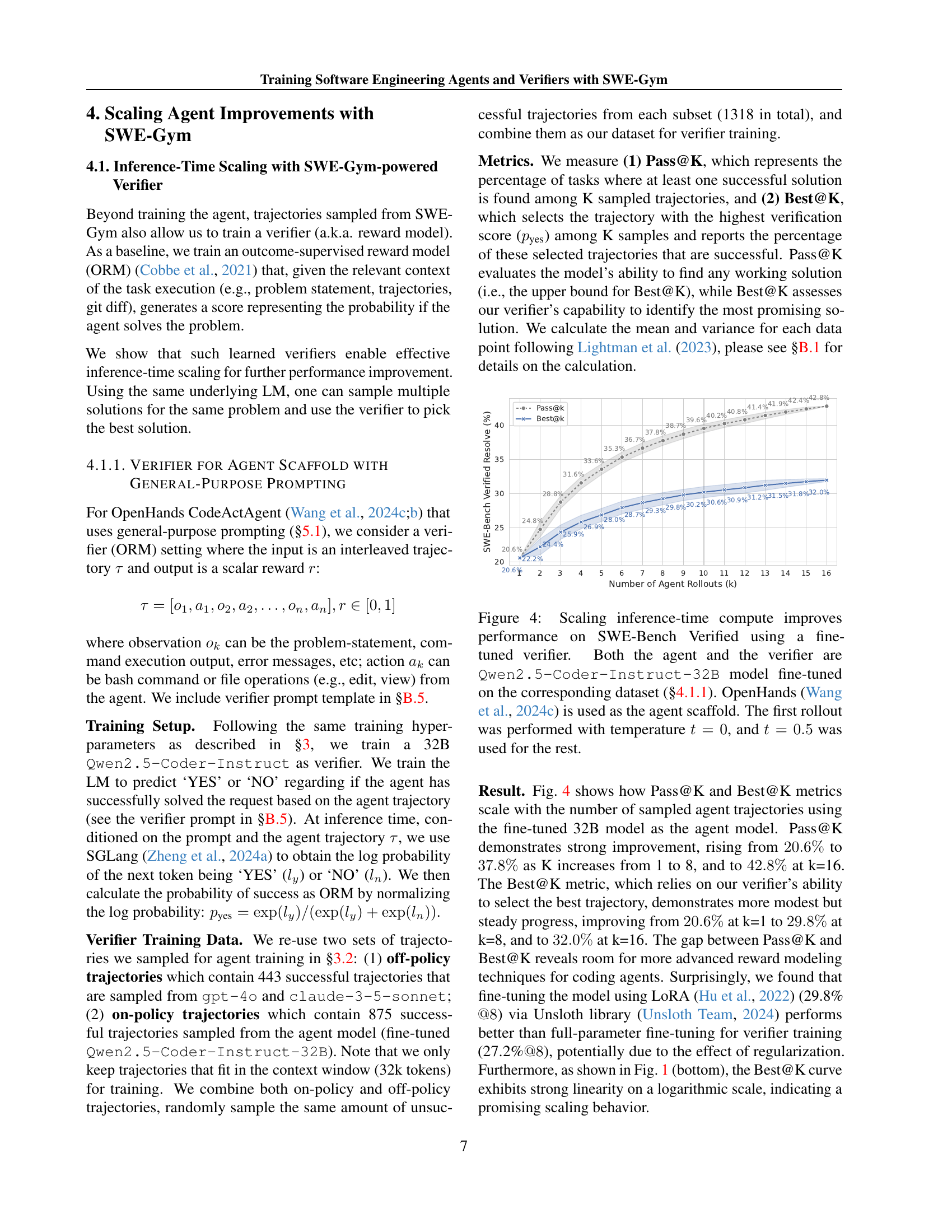

🔼 This figure demonstrates how increasing the computational resources allocated to inference improves the performance of software engineering agents on the SWE-Bench Verified dataset. The experiment uses a fine-tuned Qwen-2.5-Coder-Instruct-32B language model as both the agent and verifier. The agent utilizes the OpenHands framework for its interactions. The initial inference uses a temperature of 0, while subsequent inferences use a temperature of 0.5. The graph illustrates the relationship between the number of agent rollouts (attempts to solve the problem) and the success rate (resolve rate). The improvement in performance is directly tied to increased compute, enabling the exploration of multiple solution candidates.

read the caption

Figure 4: Scaling inference-time compute improves performance on SWE-Bench Verified using a fine-tuned verifier. Both the agent and the verifier are Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct-32B model fine-tuned on the corresponding dataset (§4.1.1). OpenHands (Wang et al., 2024c) is used as the agent scaffold. The first rollout was performed with temperature t=0𝑡0t=0italic_t = 0, and t=0.5𝑡0.5t=0.5italic_t = 0.5 was used for the rest.

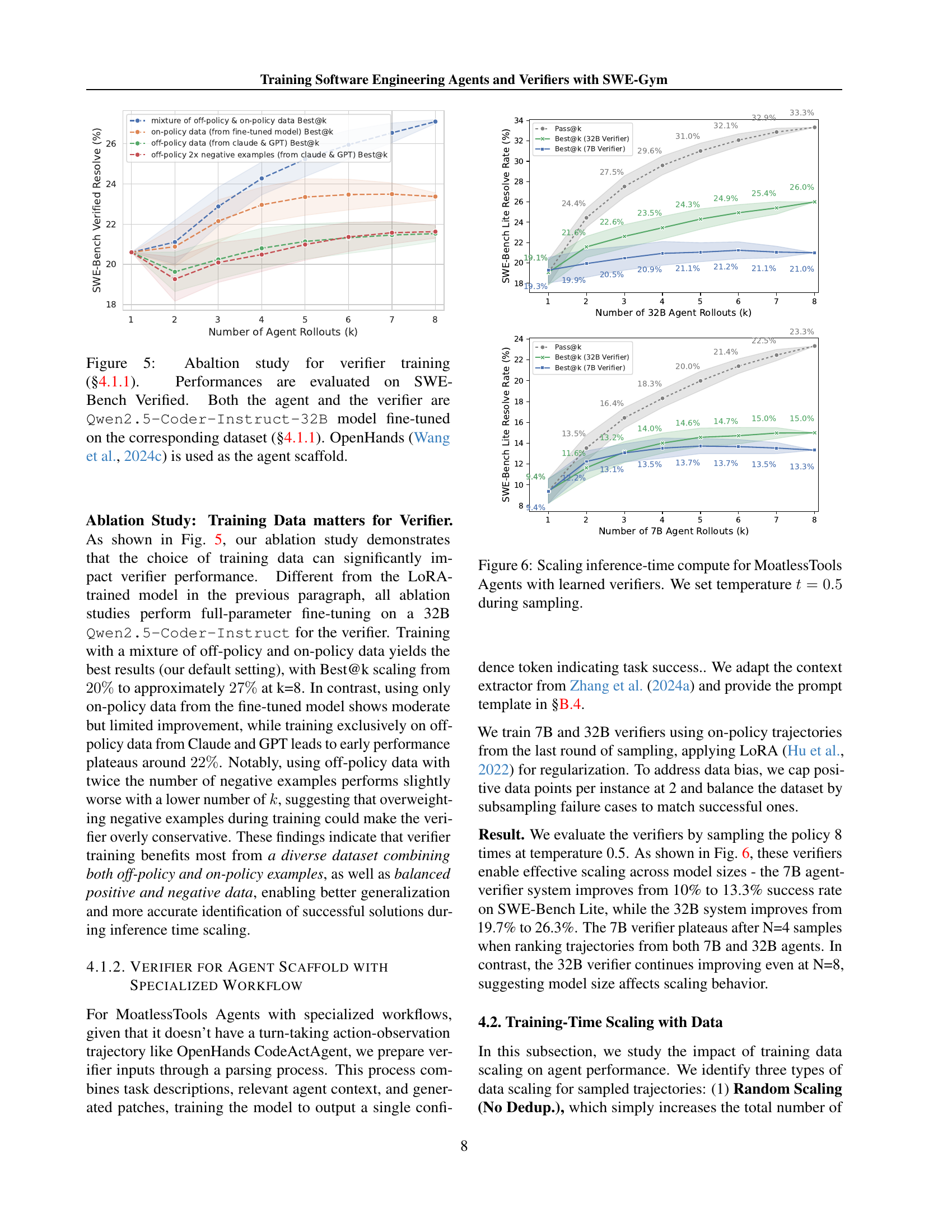

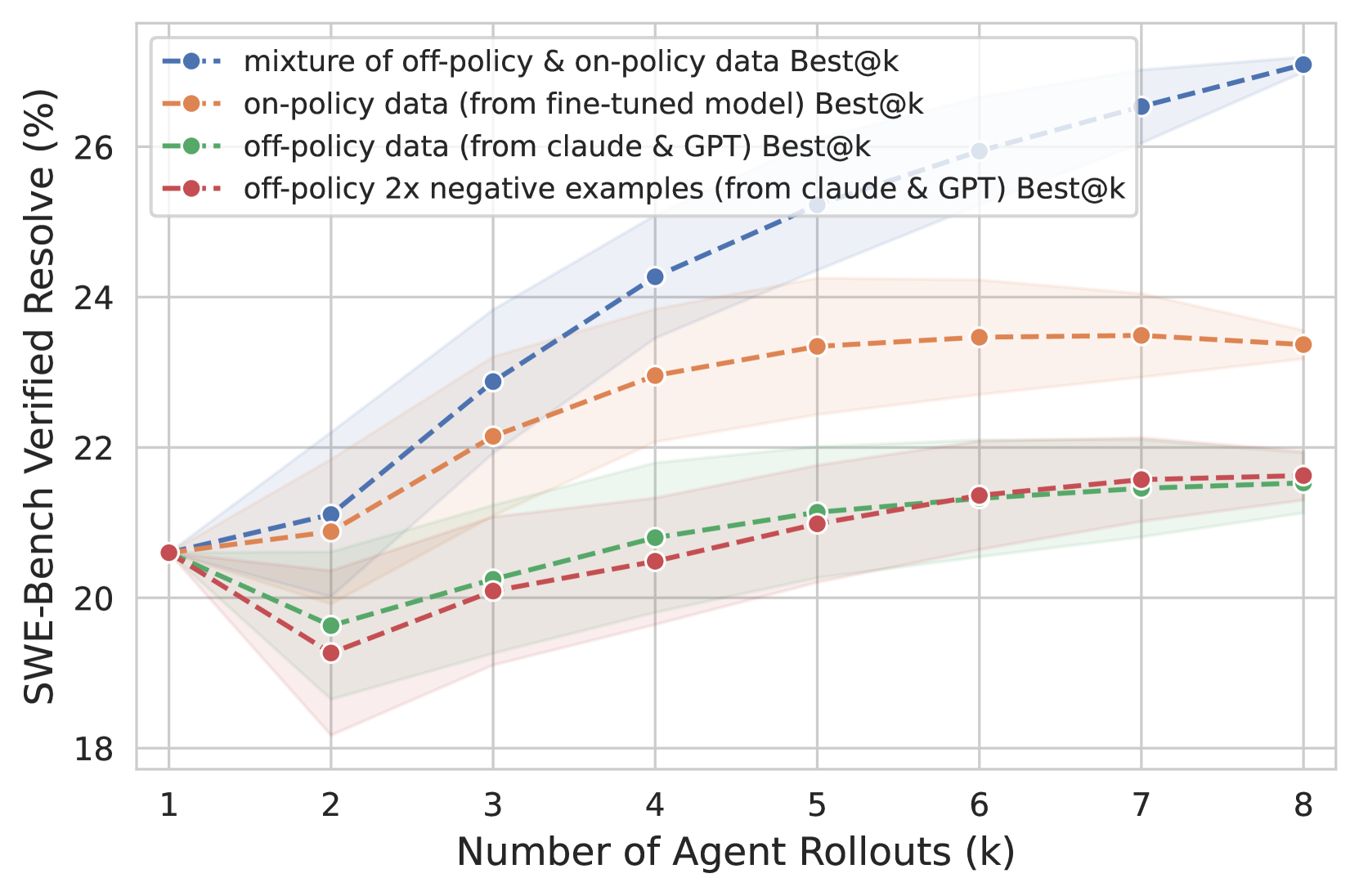

🔼 This ablation study analyzes the impact of different training data on verifier performance. The experiment evaluates performance on the SWE-Bench Verified dataset using a 32B Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct model for both the agent and the verifier. The agent utilizes the OpenHands scaffold. The study compares the performance of a verifier trained with: a mixture of on-policy and off-policy data (the default setting), only on-policy data from the fine-tuned model, only off-policy data, and off-policy data with twice the number of negative examples. The results show the effectiveness of combining on-policy and off-policy data for optimal verifier performance.

read the caption

Figure 5: Abaltion study for verifier training (§4.1.1). Performances are evaluated on SWE-Bench Verified. Both the agent and the verifier are Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct-32B model fine-tuned on the corresponding dataset (§4.1.1). OpenHands (Wang et al., 2024c) is used as the agent scaffold.

🔼 This figure demonstrates how inference-time performance scales with increased compute for software engineering agents using the MoatlessTools framework. The experiment employs learned verifiers to evaluate multiple agent-generated solutions for a given task. The graph shows the improvement in the resolution rate (success rate) of the MoatlessTools agents on the SWE-Bench Lite benchmark as the number of agent rollouts (and consequently, the amount of compute) increases. A temperature of 0.5 was used during the sampling process for generating candidate solutions.

read the caption

Figure 6: Scaling inference-time compute for MoatlessTools Agents with learned verifiers. We set temperature t=0.5𝑡0.5t=0.5italic_t = 0.5 during sampling.

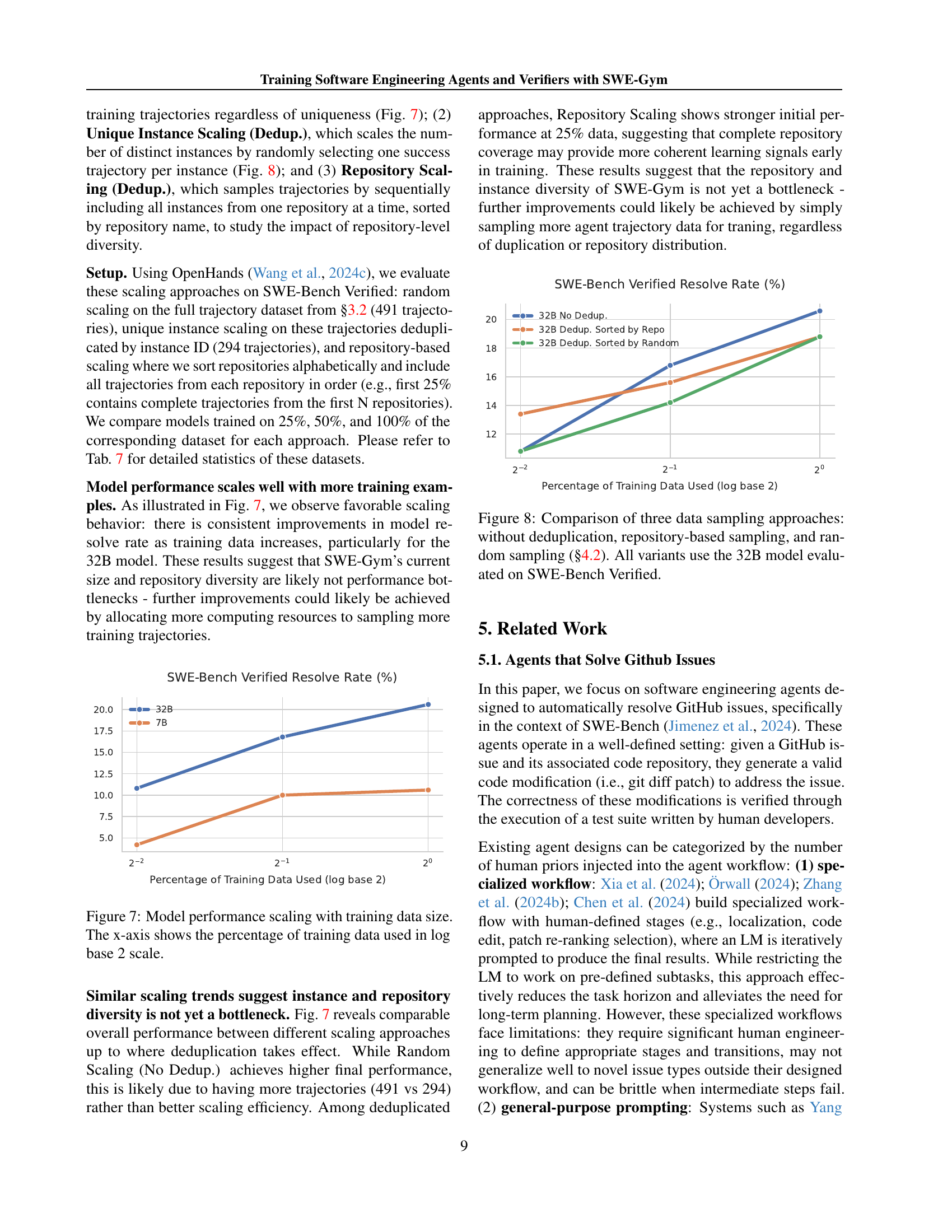

🔼 This figure illustrates how the performance of two different sized language models (7B and 32B parameters) scales with the amount of training data used. The x-axis uses a logarithmic scale (base 2) to represent the percentage of the total training data used, ranging from 25% to 100%. The y-axis represents the model’s performance, specifically the resolve rate (percentage of successfully solved problems) on the SWE-Bench Verified dataset. The graph shows an upward trend for both models, indicating that increased training data leads to improved performance. The 32B model consistently outperforms the 7B model across all data sizes, demonstrating the benefit of larger model capacity.

read the caption

Figure 7: Model performance scaling with training data size. The x-axis shows the percentage of training data used in log base 2 scale.

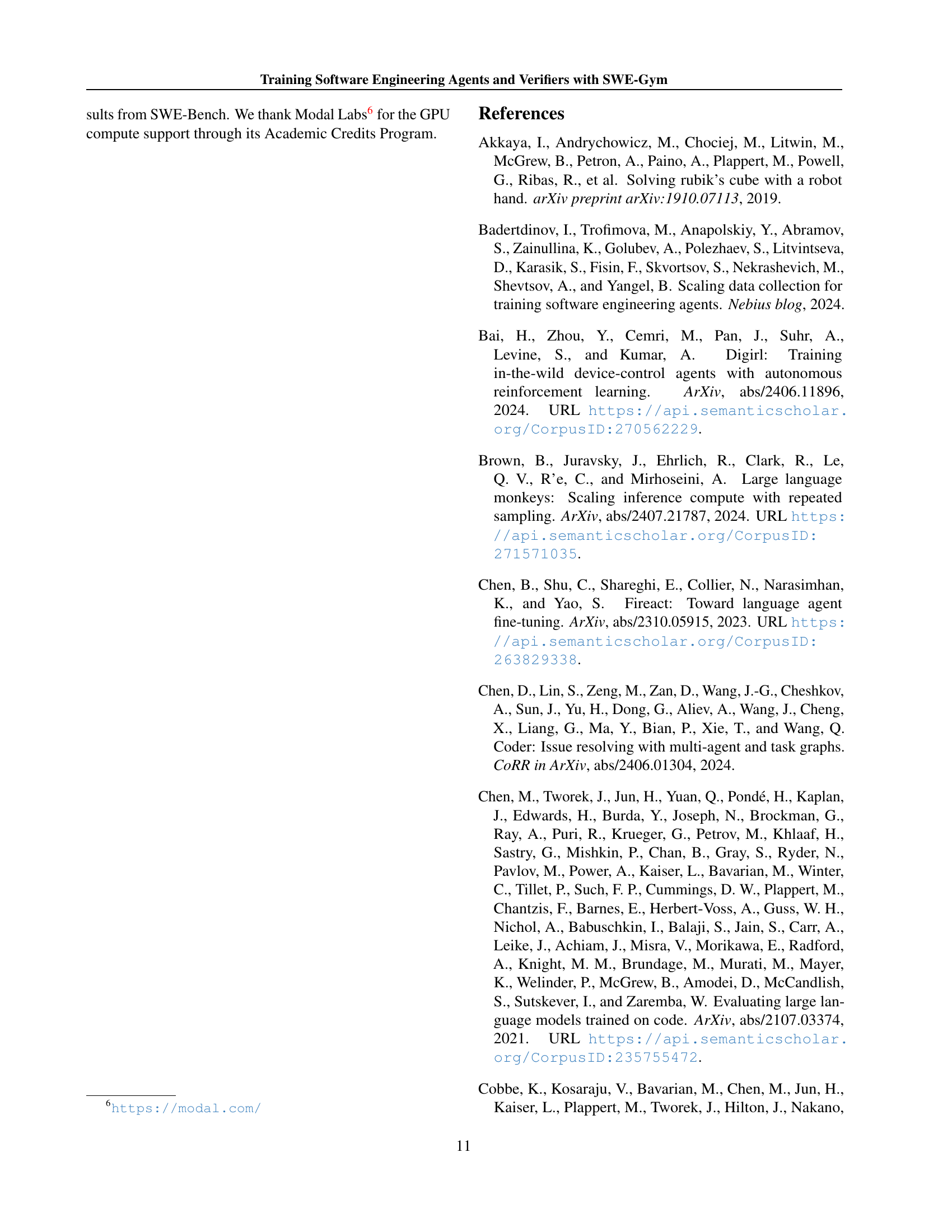

🔼 Figure 8 illustrates the impact of different data sampling methods on the performance of a 32B language model evaluated on the SWE-Bench Verified dataset. Three approaches are compared: random sampling (without deduplication), repository-based sampling (with deduplication), and random sampling (with deduplication). The x-axis represents the percentage of training data used, and the y-axis represents the model’s resolve rate. This figure shows how different strategies for selecting training data affect the model’s performance and whether the size or diversity of the training data is a limiting factor.

read the caption

Figure 8: Comparison of three data sampling approaches: without deduplication, repository-based sampling, and random sampling (§4.2). All variants use the 32B model evaluated on SWE-Bench Verified.

More on tables

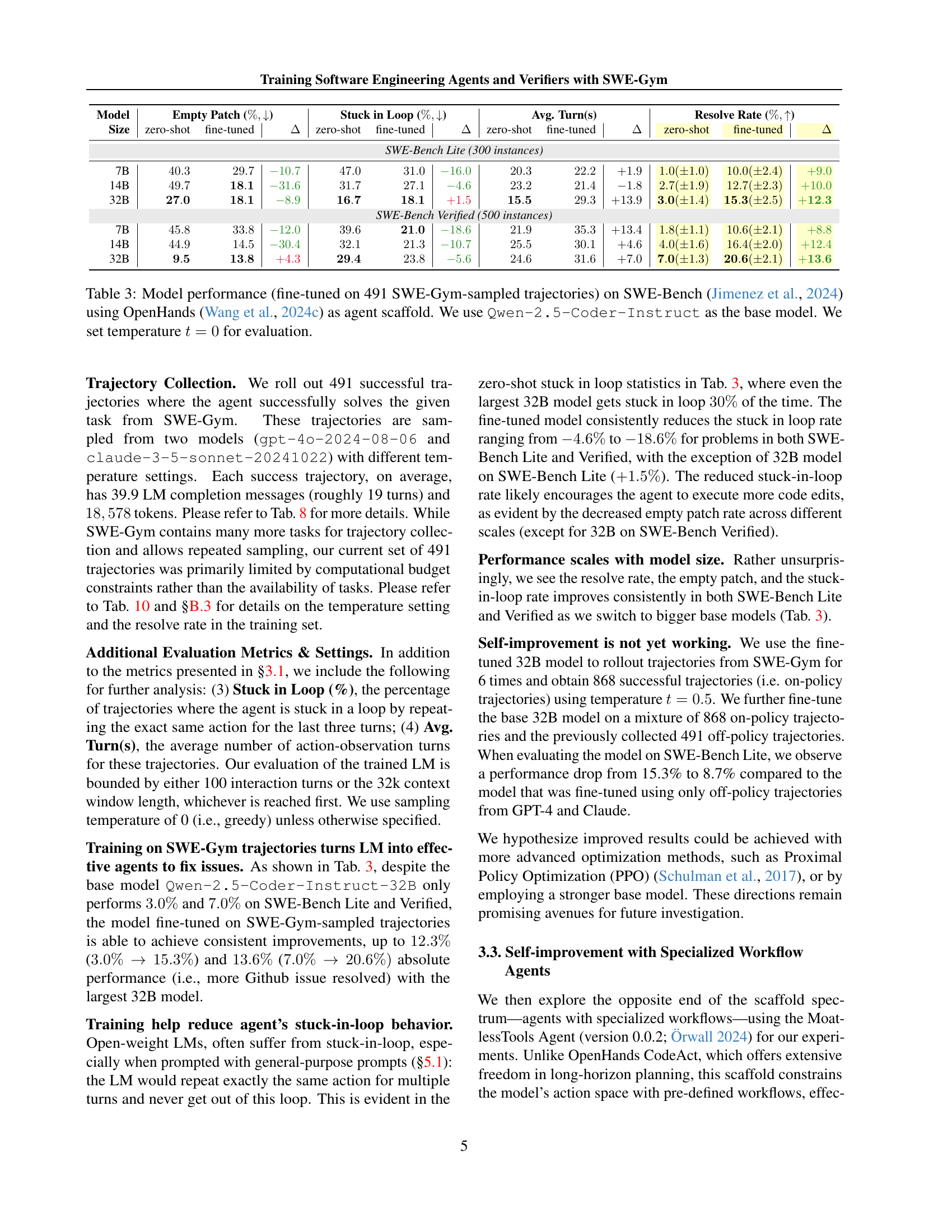

| Model | Empty Patch (%,[downarrow]) | Stuck in Loop (%,[downarrow]) | Avg. Turn(s) | Resolve Rate (%,[uparrow]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | zero-shot | fine-tuned | Δ | zero-shot | fine-tuned | Δ | zero-shot | fine-tuned | Δ | zero-shot |

| SWE-Bench Lite (300 instances) | ||||||||||

| 7B | 40.3 | 29.7 | -10.7 | 47.0 | 31.0 | -16.0 | 20.3 | 22.2 | +1.9 | 1.0(±1.0) |

| 14B | 49.7 | 18.1 | -31.6 | 31.7 | 27.1 | -4.6 | 23.2 | 21.4 | -1.8 | 2.7(±1.9) |

| 32B | 27.0 | 18.1 | -8.9 | 16.7 | 18.1 | +1.5 | 15.5 | 29.3 | +13.9 | 3.0(±1.4) |

| SWE-Bench Verified (500 instances) | ||||||||||

| 7B | 45.8 | 33.8 | -12.0 | 39.6 | 21.0 | -18.6 | 21.9 | 35.3 | +13.4 | 1.8(±1.1) |

| 14B | 44.9 | 14.5 | -30.4 | 32.1 | 21.3 | -10.7 | 25.5 | 30.1 | +4.6 | 4.0(±1.6) |

| 32B | 9.5 | 13.8 | +4.3 | 29.4 | 23.8 | -5.6 | 24.6 | 31.6 | +7.0 | 7.0(±1.3) |

🔼 This table presents the performance of different sized language models (7B, 14B, and 32B parameters) fine-tuned using trajectories from the SWE-Gym dataset. The models were evaluated on the SWE-Bench Lite and SWE-Bench Verified benchmarks. The evaluation used the OpenHands agent scaffold and a temperature of 0 during the testing phase. The table shows the resolve rate, empty patch rate, stuck-in-loop rate, and average number of turns for each model configuration. These metrics provide insights into the model’s ability to successfully complete software engineering tasks and its efficiency during the process.

read the caption

Table 3: Model performance (fine-tuned on 491 SWE-Gym-sampled trajectories) on SWE-Bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) using OpenHands (Wang et al., 2024c) as agent scaffold. We use Qwen-2.5-Coder-Instruct as the base model. We set temperature t=0𝑡0t=0italic_t = 0 for evaluation.

| ↑) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Zero-shot) | 0 | 56.3 | 7.0 |

| 1 | 36 | 37.3 | 9.0 |

| 2 | 62 | 29 | 9.7 |

| 3 | 82 | 43.7 | 7.7 |

| No Cap (All) | 172 | 30.7 | 9.3 |

🔼 This table shows the results of training a 7B model on the SWE-Bench Lite dataset using different instance capping strategies. The instance capping limits the number of trajectories sampled per instance, which indirectly affects the number of total training trajectories. The table compares the resolve rate (percentage of successfully resolved tasks) and the empty patch rate (percentage of tasks with no code edits) achieved under each capping strategy. It demonstrates the impact of data balancing and the trade-off between the quantity and quality of training data on model performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Resolve rate and empty patch rate on SWE-Bench Lite after 7B model trained with with data from different instance capping strategies (Cap) and therefore different number of trajectories (Traj).

| Setting | 7B Model | 32B Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP(%,↓) | RR(%,↑) | EP(%,↓) | RR(%,↑) | |

| Zero-Shot | 56.3% | 7.0% | 24.3% | 19.0% |

| Iteration 1 | 29.0% | 9.0% | 18.3% | 19.7% |

| Iteration 2 | 23.3% | 10.0% | 9.7% | 19.7% |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments using the MoatlessTools agent scaffold on the SWE-Bench Lite dataset. The experiments involved online rejection sampling fine-tuning, a technique used to improve model performance. The table shows the Resolve Rate (RR), which represents the percentage of successfully resolved problems, and the Empty Patch Rate (EP), which indicates the percentage of tasks where no code changes were made by the model. The Resolve Rate is presented in the highlighted columns, and all results are evaluated at a temperature of 0. The purpose is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the MoatlessTools scaffold combined with online rejection sampling fine-tuning.

read the caption

Table 5: Resolve rate (RR) and Empty patch rate (EP) on SWE-Bench Lite with MoatlessTools Scaffold after online rejection sampling fine-tuning, evaluated at temperature t=0𝑡0t=0italic_t = 0. RR shown in highlighted columns.

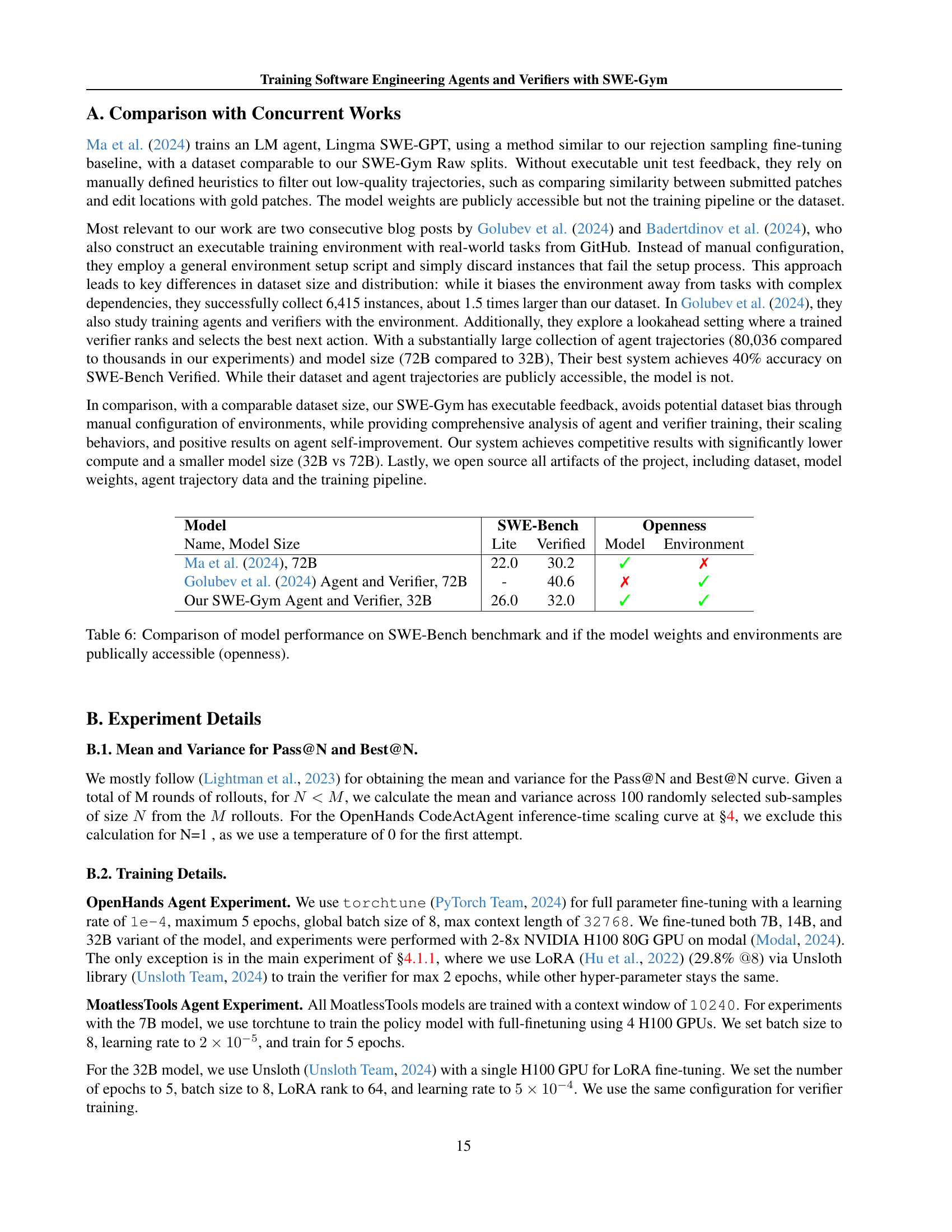

| Model | SWE-Bench | SWE-Bench | Openness | Openness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, Model Size | Lite | Verified | Model | Environment |

| Ma et al. (2024), 72B | 22.0 | 30.2 | ✓ | ✗ |

| Golubev et al. (2024) Agent and Verifier, 72B | - | 40.6 | ✗ | ✓ |

| Our SWE-Gym Agent and Verifier, 32B | 26.0 | 32.0 | ✓ | ✓ |

🔼 This table compares the performance of different models on the SWE-Bench benchmark. It highlights not only the achieved results (on both the Lite and Verified subsets of SWE-Bench) but also the accessibility of the model weights and the environments used for training. This allows for a comparative analysis considering both performance and reproducibility.

read the caption

Table 6: Comparison of model performance on SWE-Bench benchmark and if the model weights and environments are publically accessible (openness).

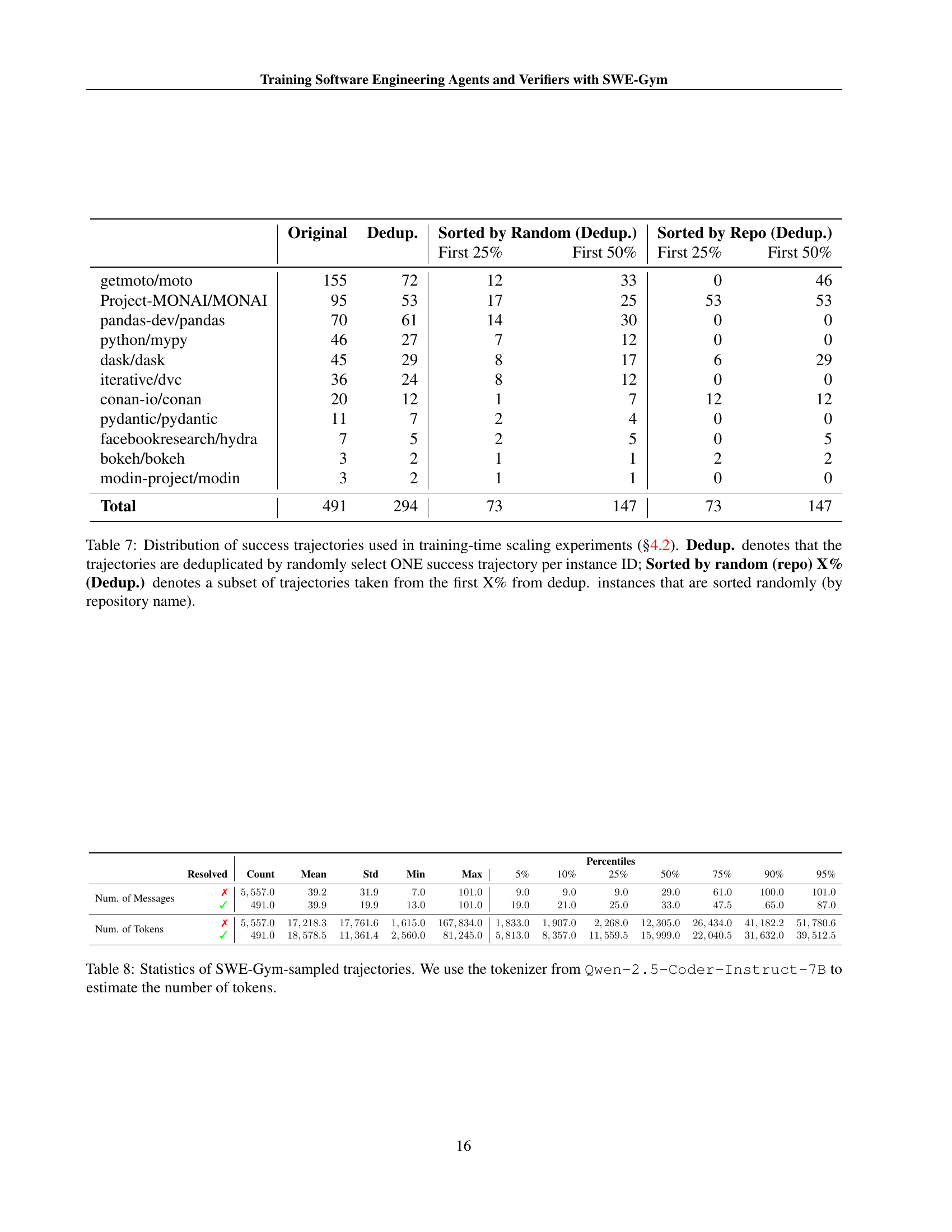

| Original | Dedup. | Sorted by Random (Dedup.) | Sorted by Random (Dedup.) | Sorted by Repo (Dedup.) | Sorted by Repo (Dedup.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First 25% | First 50% | First 25% | First 50% | |||

| getmoto/moto | 155 | 72 | 12 | 33 | 0 | 46 |

| Project-MONAI/MONAI | 95 | 53 | 17 | 25 | 53 | 53 |

| pandas-dev/pandas | 70 | 61 | 14 | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| python/mypy | 46 | 27 | 7 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| dask/dask | 45 | 29 | 8 | 17 | 6 | 29 |

| iterative/dvc | 36 | 24 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| conan-io/conan | 20 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 12 | 12 |

| pydantic/pydantic | 11 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| facebookresearch/hydra | 7 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| bokeh/bokeh | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| modin-project/modin | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 491 | 294 | 73 | 147 | 73 | 147 |

🔼 Table 7 details the distribution of successful trajectories used in the training-time scaling experiments of section 4.2. The table shows how the number of trajectories changes when different sampling methods are applied. The original data contains all successful trajectories, while the ‘Dedup.’ column shows the data after deduplication (one successful trajectory kept per instance ID). ‘Sorted by random (repo) X% (Dedup.)’ represents subsets of the deduplicated data, where the first X% of instances are randomly selected (or sorted by repository name). This allows for analysis of how different data sampling strategies (random and repository-based) affect the results of the experiments.

read the caption

Table 7: Distribution of success trajectories used in training-time scaling experiments (§4.2). Dedup. denotes that the trajectories are deduplicated by randomly select ONE success trajectory per instance ID; Sorted by random (repo) X% (Dedup.) denotes a subset of trajectories taken from the first X% from dedup. instances that are sorted randomly (by repository name).

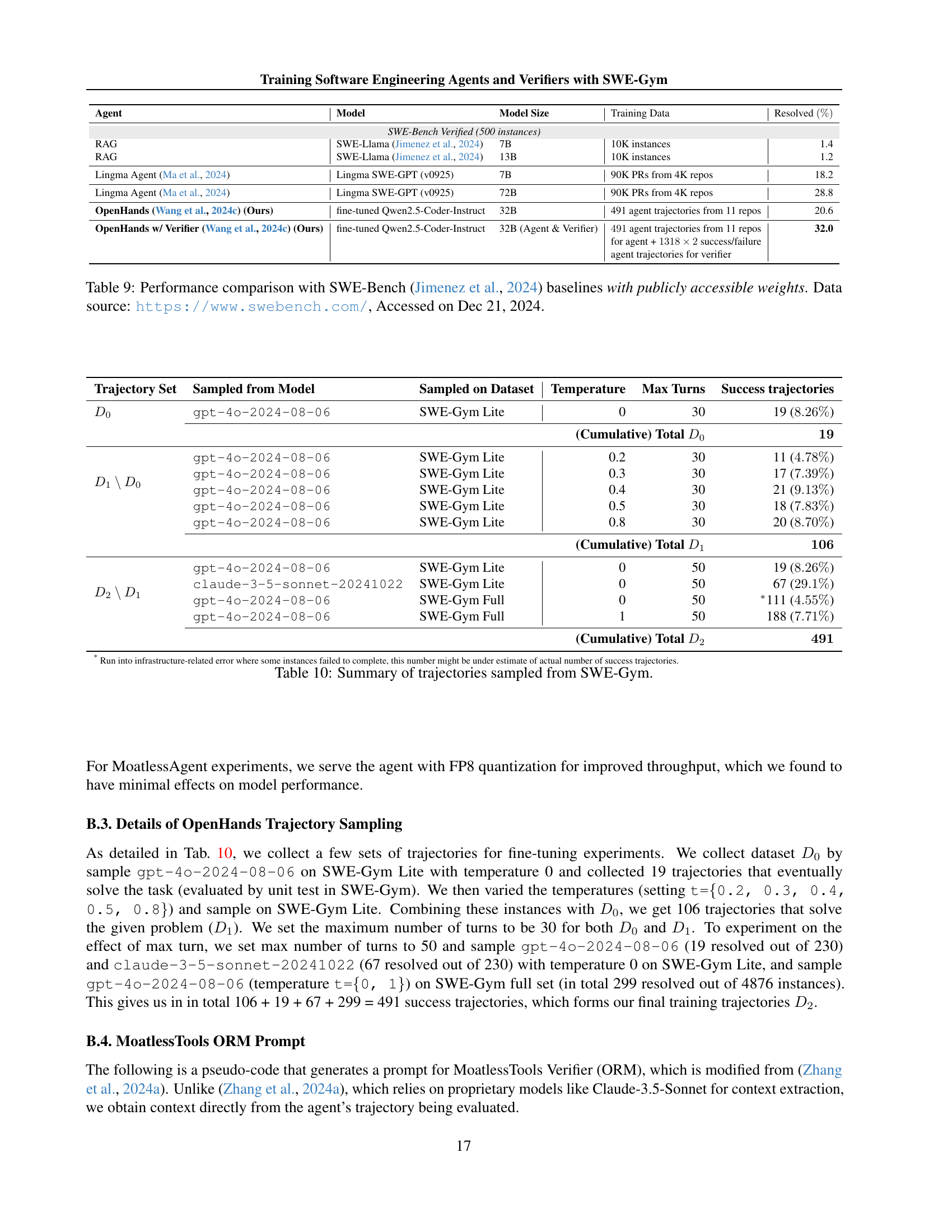

| Resolved | Count | Mean | Std | Min | Max | 5% | 10% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 90% | 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num. of Messages | ✗ | 5,557.0 | 39.2 | 31.9 | 7.0 | 101.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 29.0 | 61.0 | 100.0 | 101.0 |

| ✓ | 491.0 | 39.9 | 19.9 | 13.0 | 101.0 | 19.0 | 21.0 | 25.0 | 33.0 | 47.5 | 65.0 | 87.0 | |

| Num. of Tokens | ✗ | 5,557.0 | 17,218.3 | 17,761.6 | 1,615.0 | 167,834.0 | 1,833.0 | 1,907.0 | 2,268.0 | 12,305.0 | 26,434.0 | 41,182.2 | 51,780.6 |

| ✓ | 491.0 | 18,578.5 | 11,361.4 | 2,560.0 | 81,245.0 | 5,813.0 | 8,357.0 | 11,559.5 | 15,999.0 | 22,040.5 | 31,632.0 | 39,512.5 |

🔼 Table 8 presents a statistical overview of the trajectories sampled from SWE-Gym, which is a dataset used for training software engineering agents and verifiers. The table details the number of messages, and the total number of tokens in each trajectory. The token count was calculated using the tokenizer from the Qwen-2.5-Coder-Instruct-7B language model.

read the caption

Table 8: Statistics of SWE-Gym-sampled trajectories. We use the tokenizer from Qwen-2.5-Coder-Instruct-7B to estimate the number of tokens.

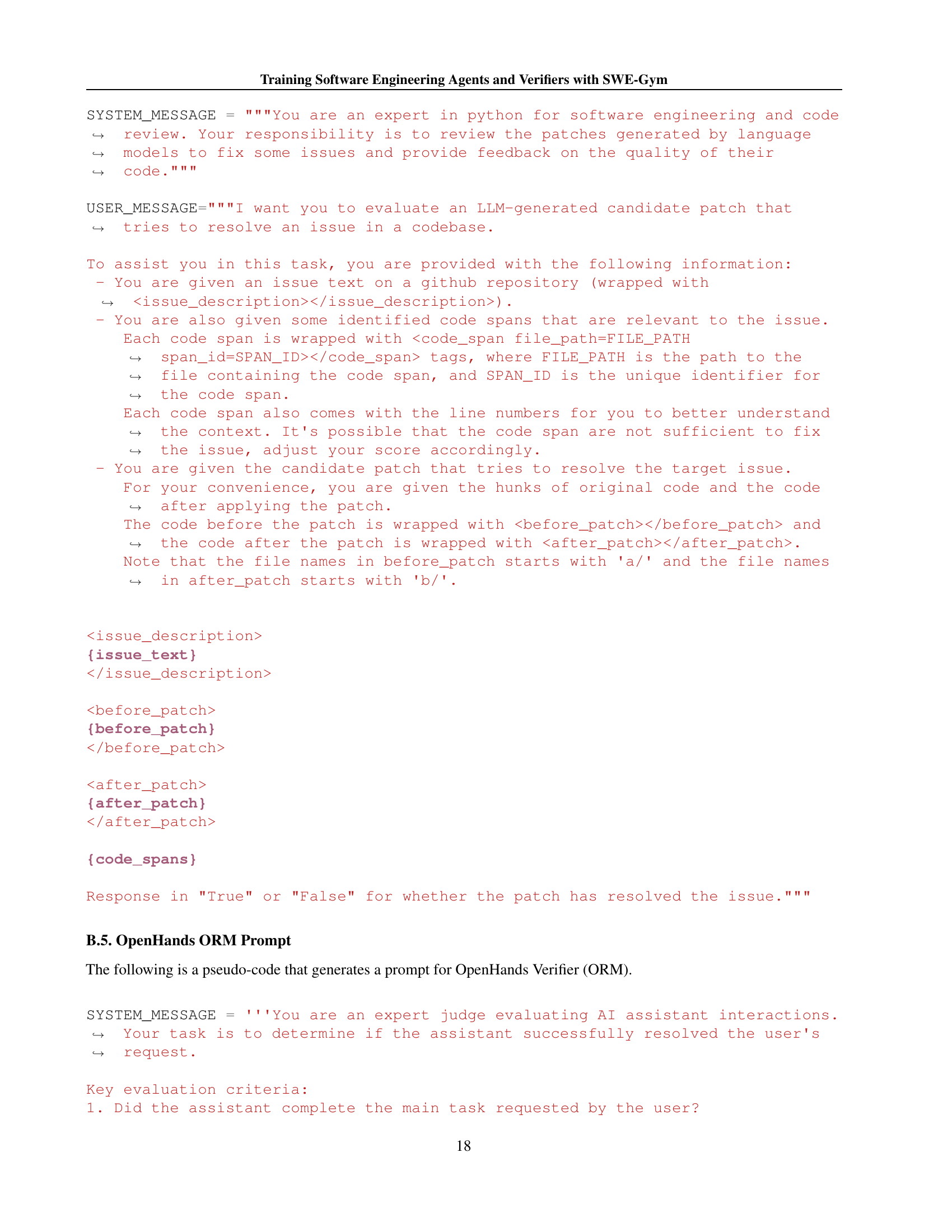

| Agent | Model | Model Size | Training Data | Resolved (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAG | SWE-Llama (Jimenez et al., 2024) | 7B | 10K instances | 1.4 |

| RAG | SWE-Llama (Jimenez et al., 2024) | 13B | 10K instances | 1.2 |

| Lingma Agent (Ma et al., 2024) | Lingma SWE-GPT (v0925) | 7B | 90K PRs from 4K repos | 18.2 |

| Lingma Agent (Ma et al., 2024) | Lingma SWE-GPT (v0925) | 72B | 90K PRs from 4K repos | 28.8 |

| OpenHands (Wang et al., 2024c) (Ours) | fine-tuned Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct | 32B | 491 agent trajectories from 11 repos | 20.6 |

| OpenHands w/ Verifier (Wang et al., 2024c) (Ours) | fine-tuned Qwen2.5-Coder-Instruct | 32B (Agent & Verifier) | 491 agent trajectories from 11 repos for agent + 1318 x 2 success/failure agent trajectories for verifier | 32.0 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of different software engineering agents on the SWE-Bench benchmark. It specifically focuses on models with publicly available weights, making the results reproducible. The table lists each agent’s model size, the training data used, and the achieved resolution rate on SWE-Bench. This allows for a direct comparison of different approaches and models in terms of their effectiveness at solving real-world software engineering problems. The data for SWE-Bench is sourced from https://www.swebench.com/ and accessed on December 21, 2024.

read the caption

Table 9: Performance comparison with SWE-Bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) baselines with publicly accessible weights. Data source: https://www.swebench.com/, Accessed on Dec 21, 2024.

Full paper#