↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current benchmarks for large language models (LLMs) primarily focus on isolated code generation tasks. This approach doesn’t accurately reflect real-world coding scenarios that often demand complex reasoning and the ability to utilize previously generated code to tackle more complex issues. This paper introduces three new benchmarks, HumanEval Pro, MBPP Pro, and BigCodeBench-Lite Pro, which are designed to evaluate LLMs on a new task called “self-invoking code generation”. In this task, LLMs must solve a simple problem and then use its solution to address a related, more complex problem.

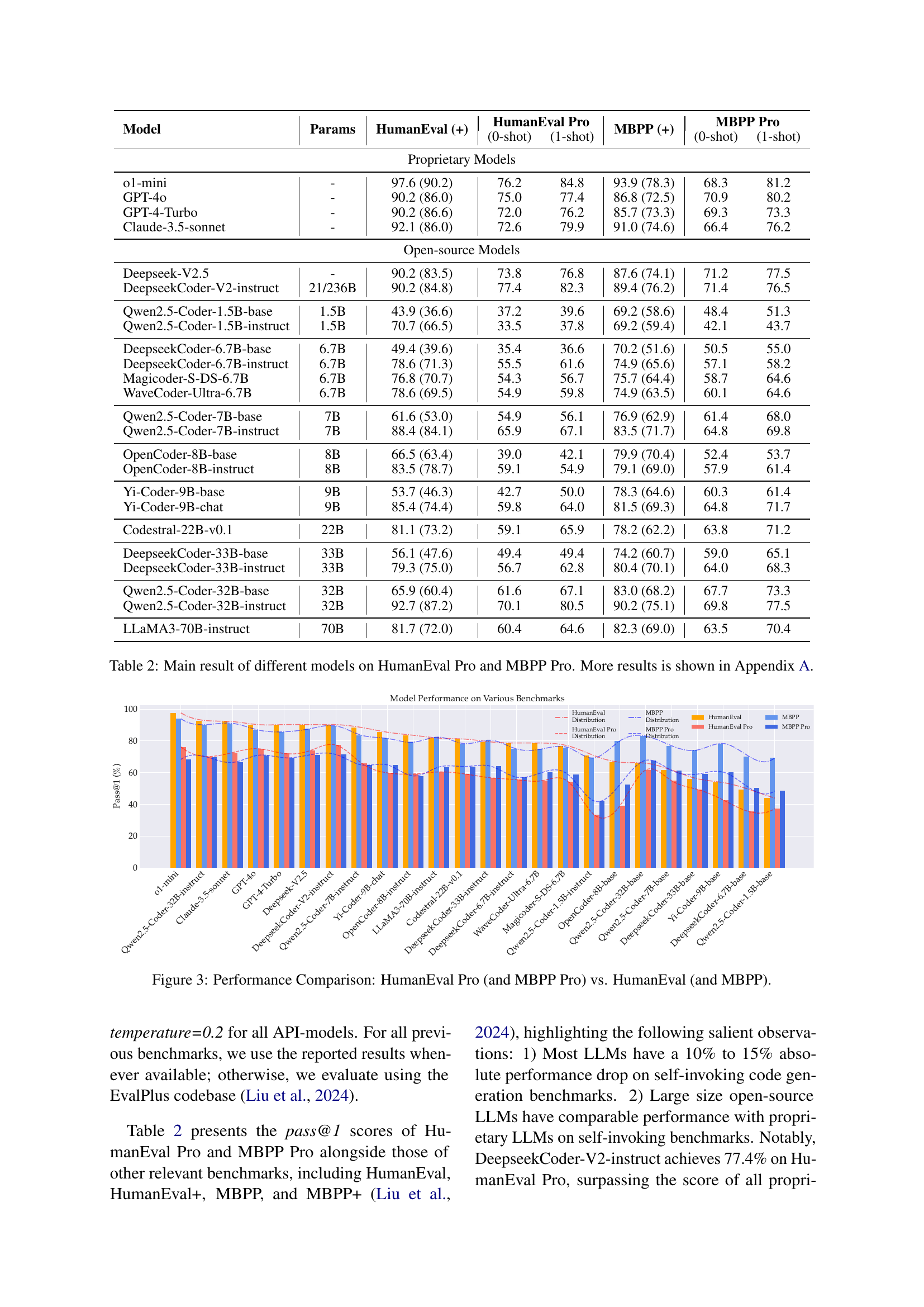

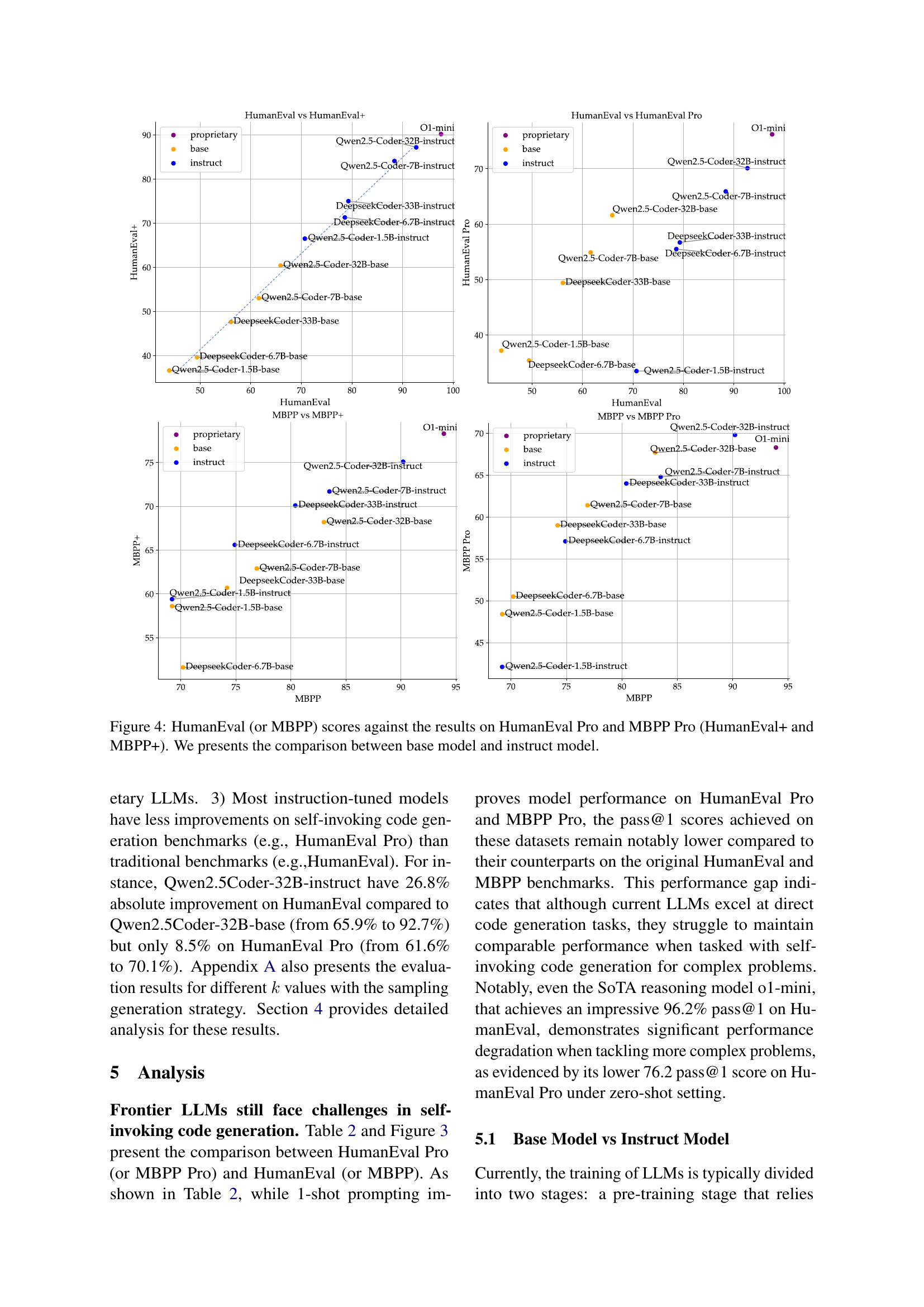

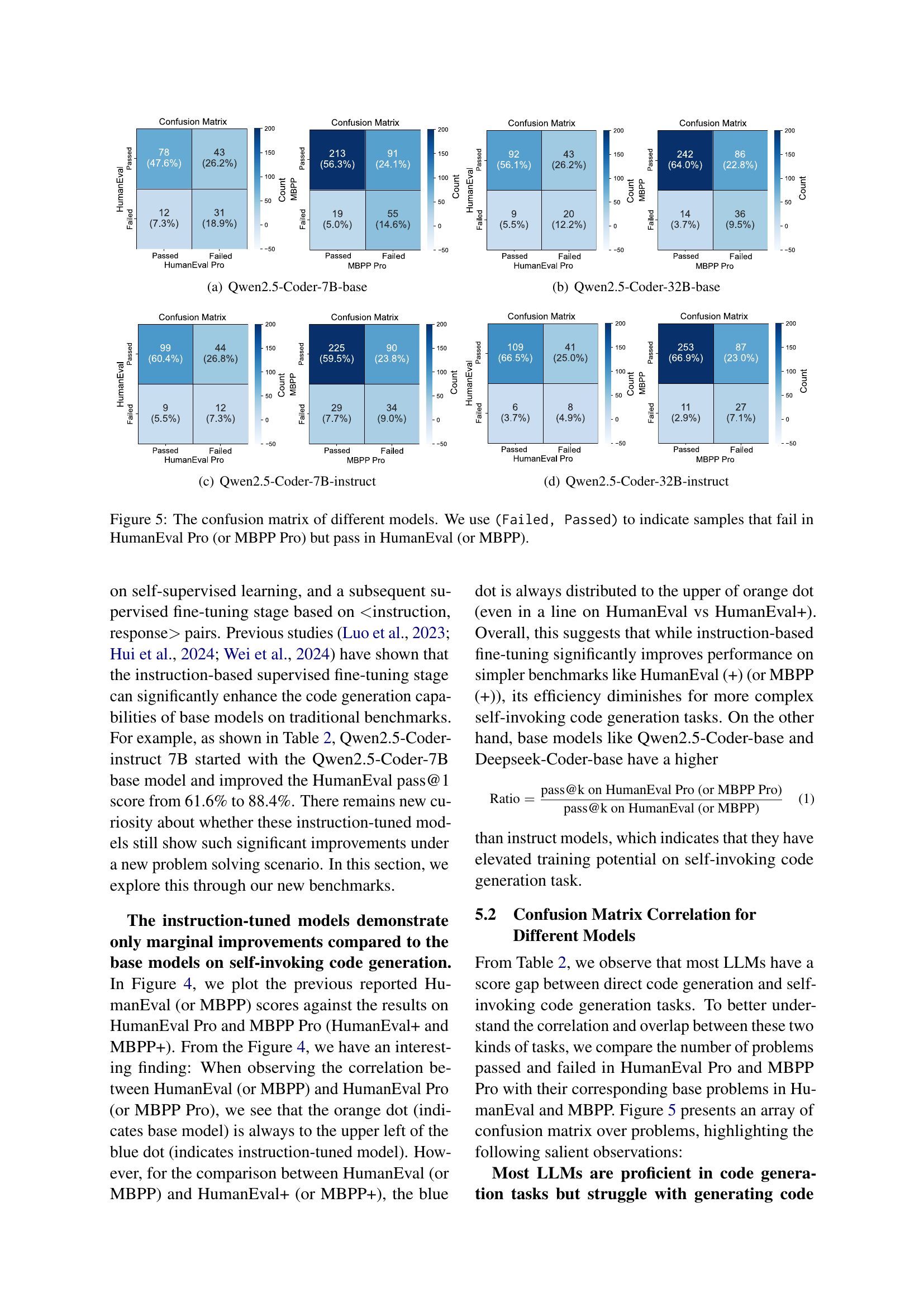

The study evaluates twenty LLMs across these benchmarks. The results reveal that while LLMs often perform well on the standard code generation benchmarks, their performance significantly drops in the self-invoking tasks. Additionally, the researchers find that instruction-tuned models, which are specifically trained to follow instructions, exhibit only marginal improvements compared to their base models in the self-invoking code generation task. The failure analysis reveals that difficulties in utilizing self-generated code and handling logical inconsistencies are major factors leading to the performance drop. The paper’s findings underscore the limitations of existing benchmarks and point towards the need for improvements in LLM training methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel evaluation task for large language models (LLMs), addressing limitations of existing benchmarks. It highlights the gap between LLMs’ ability to generate isolated code and their capacity to utilize self-generated code for complex problem-solving. This finding paves the way for future research focused on improving the progressive reasoning and problem-solving capabilities of LLMs. The proposed benchmarks and analysis provide valuable insights for researchers developing and evaluating LLMs.

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure illustrates the self-invoking code generation task. Given a simple base problem and a more complex problem that relies on the solution of the base problem, the model must solve the base problem first and then use its solution (or a function from its solution) to address the second, more complex problem. This tests the model’s ability to not only generate code but also to use previously-generated code in a progressive problem-solving manner.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of self-invoking code generation in HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro. Given a base problem and a related, more complex problem, they are required to solve the base problem and use its solution to address the complex problems.

| Iteration | HumanEval Pro (%) | MBPP Pro (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | 64.0 | 84.7 |

| Round 2 | 98.8 | 99.7 |

| Round 3 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

🔼 This table shows the success rate of generating canonical solutions and test cases for HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro benchmarks across three iteration rounds. Each round involved manual review and refinement of the solutions and test cases. The pass@1 metric indicates the percentage of times the model generated a correct solution in the first attempt.

read the caption

Table 1: Pass@1 (%) of candidate solutions across different iteration rounds for canonical solution and test case generation with human manual review.

In-depth insights#

Self-Invoking Code#

The concept of “Self-Invoking Code” presents a novel approach to evaluating large language models (LLMs) by assessing their ability to not only generate code but also utilize previously generated code to solve progressively complex problems. This paradigm shift from isolated code generation tasks to more realistic, multi-step problem-solving scenarios offers a more nuanced and robust evaluation metric. The core idea is to challenge LLMs with a base problem and then a subsequent, more complex problem that explicitly requires leveraging the solution of the first. This effectively tests not just code generation capabilities but also the LLM’s understanding, modification, and application of its own generated code. The results highlight a significant performance drop for many LLMs when transitioning from traditional isolated tasks to self-invoking tasks, underscoring the limitations of current models and the need for more sophisticated reasoning abilities. This research emphasizes the importance of moving beyond simplistic benchmark evaluations towards more complex, realistic scenarios that better reflect the challenges faced in real-world software development. The ‘Self-Invoking Code’ evaluation approach therefore provides valuable insights into the current limitations of LLMs and points to a promising direction for future research focusing on enhancing code reasoning capabilities and progressive problem-solving.

LLM Reasoning#

LLM reasoning, a critical aspect of large language model capabilities, remains a complex and multifaceted area of research. Current benchmarks often fall short in evaluating the true reasoning abilities of LLMs, focusing on isolated tasks rather than the progressive, multi-step reasoning required in real-world scenarios. The capacity for self-invoking code generation, which necessitates generating a solution and then using that solution to solve a more complex related problem, is a prime example. Studies show that while LLMs excel in isolated code generation tasks, their performance significantly degrades when required to reason progressively. Instruction tuning, a popular method to improve LLM performance, demonstrates only marginal improvements in self-invoking tasks compared to base models. This suggests a need to move beyond simple benchmarks and develop new evaluation metrics that accurately assess complex multi-step reasoning. Further research is needed to explore failure modes, such as difficulties with understanding function calls or handling edge cases, and improve training methodologies to enhance true reasoning capabilities. Ultimately, the pursuit of superior LLM reasoning is about creating models capable of genuine problem-solving, not just pattern matching.

Benchmarking LLMs#

Benchmarking Large Language Models (LLMs) is crucial for evaluating their capabilities and identifying areas for improvement. Effective benchmarks should go beyond simple metrics like accuracy, and instead assess LLMs on tasks that reflect real-world applications. This includes evaluating their ability to handle complex reasoning, nuanced instructions, and diverse data formats. Bias detection and mitigation are also crucial aspects that benchmarks should consider. While existing benchmarks like GLUE and SuperGLUE have contributed valuable insights, there’s an ongoing need for benchmarks tailored to specific LLM applications, such as code generation, translation, or question answering. The design of a good benchmark requires careful consideration of task selection, metric choice, and data diversity, aiming for both breadth and depth. This holistic approach ensures a fair and informative assessment, promoting progress in the field while highlighting limitations that need further research.

Instruction Tuning#

Instruction tuning, a crucial technique in enhancing large language models (LLMs), involves fine-tuning pre-trained models on a dataset of instruction-response pairs. This method significantly improves the models’ ability to follow instructions and generate desired outputs. The effectiveness of instruction tuning hinges on the quality and diversity of the instruction dataset. A well-crafted dataset with varied instructions and corresponding high-quality responses is paramount for optimal performance. Instruction tuning demonstrably improves performance on downstream tasks, particularly those requiring complex reasoning or multi-step problem solving. This is because instruction tuning bridges the gap between the model’s internal knowledge and its ability to apply this knowledge in response to specific instructions. However, instruction tuning’s benefits are not universal. There are limitations; for instance, the improvement might be task-specific, and the model may still struggle with novel or ambiguous instructions. Future research should focus on creating larger and more diverse instruction datasets, exploring more sophisticated training methodologies, and investigating ways to enhance the models’ robustness to challenging or unforeseen instructions. Ultimately, instruction tuning remains a powerful tool in the ongoing development of more capable and adaptable LLMs.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section would greatly benefit from expanding the scope of programming languages beyond Python. Addressing the limitations of relying solely on Python datasets is crucial for broader applicability and generalizability. Furthermore, the current self-invoking problem set, while challenging, could be significantly improved by introducing a more diverse range of problems to ensure a robust evaluation of LLMs’ reasoning abilities. This could involve incorporating more real-world scenarios and complexities found in software development. Another crucial area for improvement lies in developing more sophisticated evaluation metrics that go beyond simple pass/fail rates and delve into the qualitative aspects of generated code. Analyzing specific failure modes and identifying the underlying reasons for model shortcomings will further enhance the benchmarks’ effectiveness. Lastly, exploring the potential of incorporating multilingual datasets would significantly expand the research’s scope, making it more relevant in today’s increasingly globalized software landscape.

More visual insights#

More on figures

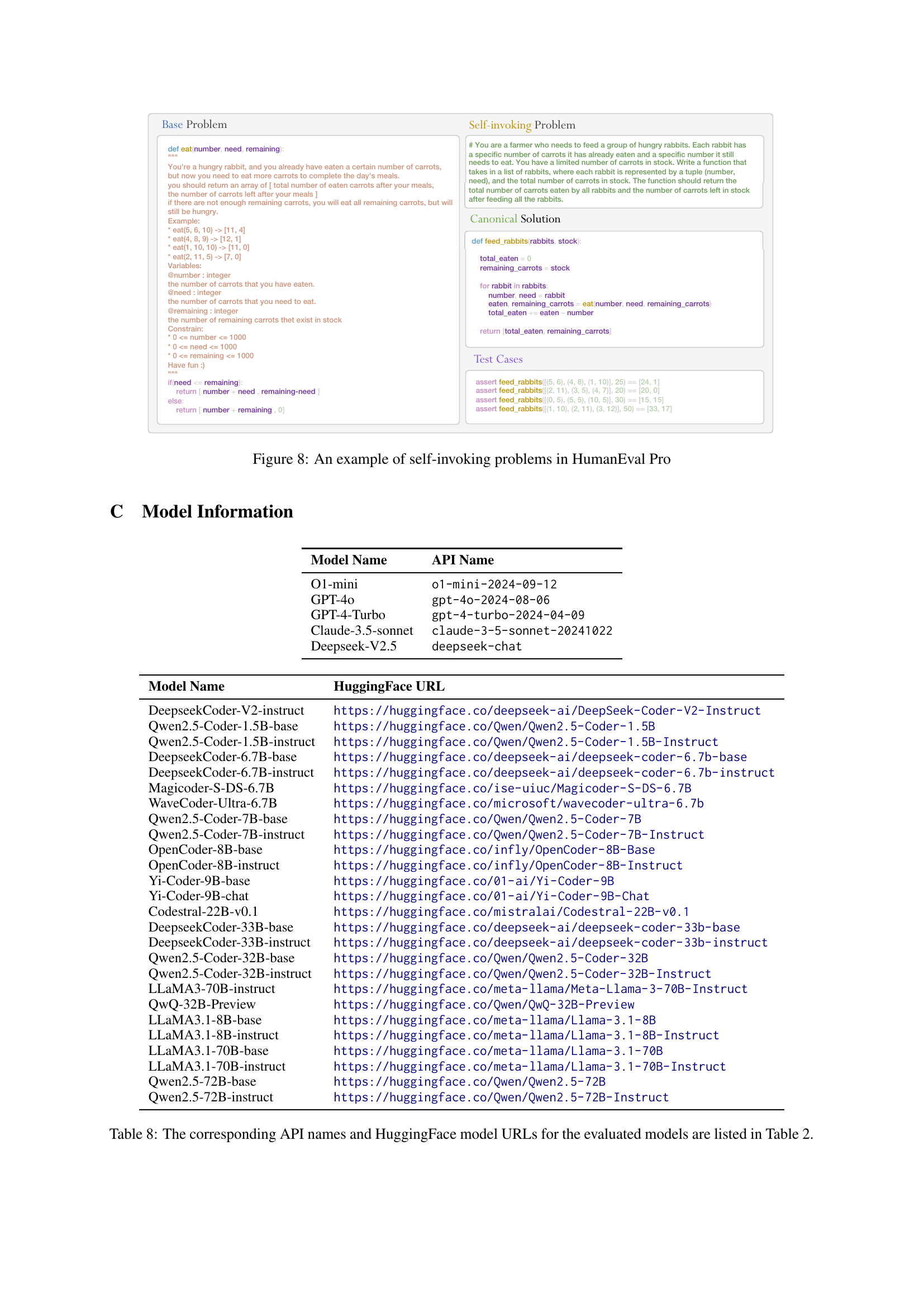

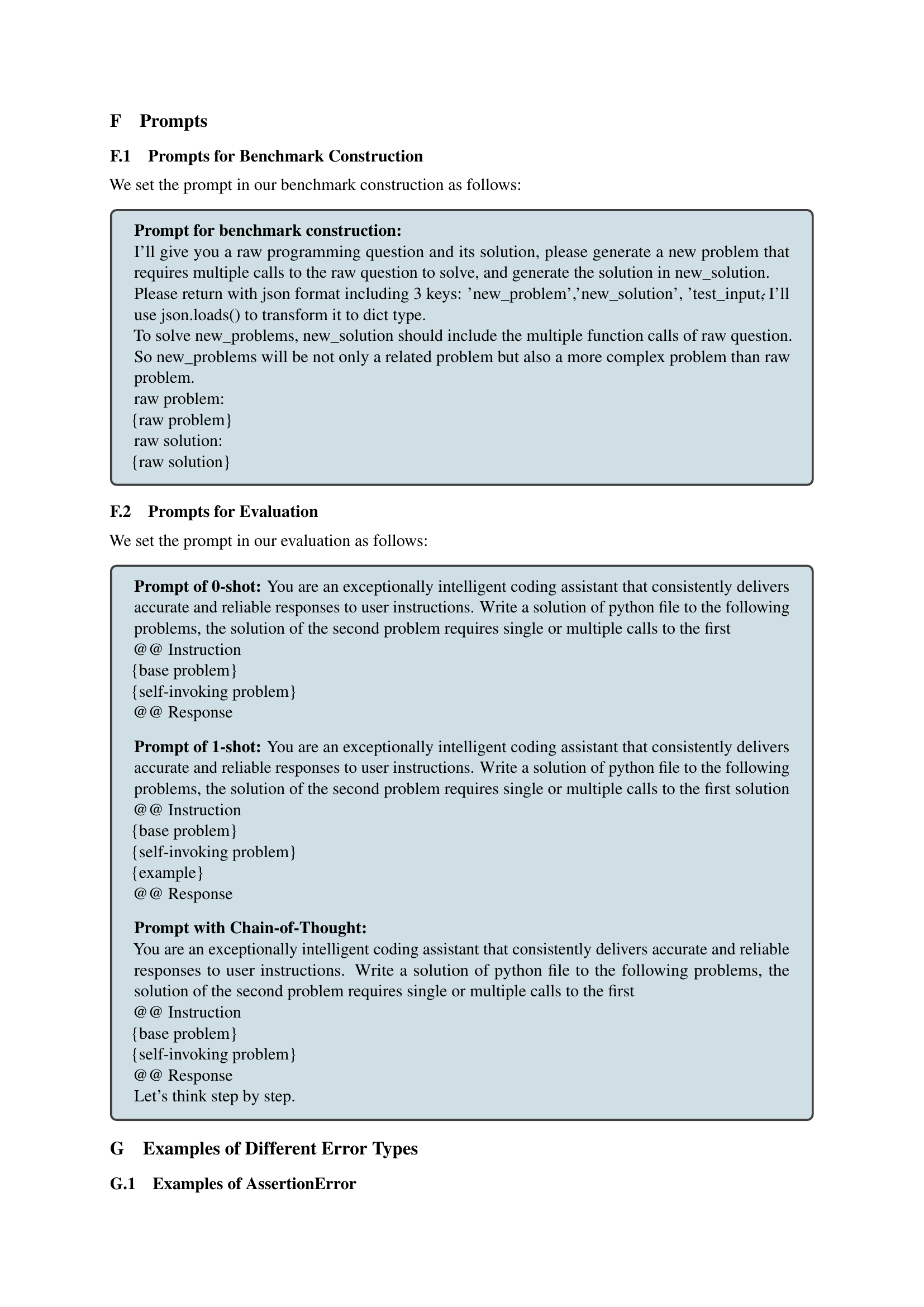

🔼 This figure illustrates the benchmark construction process, which consists of three main stages: self-invoking problem generation using Deepseek-V2.5, solution generation by executing the code in a controlled environment, and test case generation through an iterative process of Python execution checks and manual review. The final step involves using the assert command to create comprehensive test cases that ensure the reliability of the benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 2: The overview of benchmark construction. An example is shown in Figure 8. We summarize the entire benchmark construction process as follows: (1) Self-invoking problem Generation: We use Deepseek-V2.5 to generate the self-invoking problems, as well as their candidate solutions and test inputs. (2) Solutions Generation: We execute the generated solution with the test inputs in a controlled Python environment to obtain ground truth outputs. (3) Test Cases Generation: We employ an iterative method involving Python execution check and manual review to ensure that all test cases pass successfully. The final execution results are then used to construct complete test cases with assert command.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on two code generation benchmarks: HumanEval and MBPP. It shows the pass@1 scores (the percentage of times the model generated a correct solution on the first attempt) for each model on the original benchmarks (HumanEval and MBPP) and their more challenging, self-invoking counterparts (HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro). This comparison highlights the relative difficulty of self-invoking code generation tasks for LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 3: Performance Comparison: HumanEval Pro (and MBPP Pro) vs. HumanEval (and MBPP).

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of the performance of base language models and instruction-tuned models on the HumanEval and MBPP benchmarks, as well as their more challenging counterparts, HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro. Each point represents a specific model. The x-axis shows the model’s performance on the original benchmark (HumanEval or MBPP), and the y-axis shows the model’s performance on the corresponding Pro benchmark (HumanEval Pro or MBPP Pro). This allows for a visual assessment of how well the models generalize from simpler to more complex, self-invoking code generation tasks, highlighting the differences between base and instruction-tuned model performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: HumanEval (or MBPP) scores against the results on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro (HumanEval+ and MBPP+). We presents the comparison between base model and instruct model.

🔼 This confusion matrix shows the performance of the Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-base model on HumanEval and HumanEval Pro, as well as MBPP and MBPP Pro. The matrix breaks down the number of problems correctly solved (Passed) and incorrectly solved (Failed) in each benchmark. It highlights the discrepancies between the performance on the original and the self-invoking benchmarks. The numbers within each quadrant represent the count of problems in each category, with percentages indicating the proportion of the total samples.

read the caption

(a) Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-base

🔼 This figure shows the confusion matrix for the Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-base model. The confusion matrix visualizes the model’s performance on both the HumanEval and MBPP benchmarks, and their self-invoking counterparts (HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro). Each cell in the matrix represents the count of problems that fall into specific categories, For example, how many problems the model passed both in the original benchmark and the self-invoking version, and how many it passed in the original benchmark but failed in the self-invoking version. This analysis helps to understand the types of errors the model makes and where the self-invoking aspect presents additional difficulties.

read the caption

(b) Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-base

🔼 The confusion matrix for the Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-instruct model on both HumanEval and HumanEval Pro, and MBPP and MBPP Pro. The matrix shows the counts of problems that passed or failed in both the original and self-invoking benchmarks. This visualization helps understand the model’s performance differences between simpler (original) and more complex (self-invoking) code generation tasks. The numbers within each cell represent the count of problems, allowing for a detailed analysis of the model’s behavior in various scenarios.

read the caption

(c) Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-instruct

🔼 This confusion matrix shows the performance of the Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-instruct model on HumanEval and HumanEval Pro, as well as MBPP and MBPP Pro. The rows represent the results on the original benchmarks (HumanEval and MBPP), while the columns show the results on the self-invoking code generation benchmarks (HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro). Each cell displays the number of problems that fall into a particular category. For instance, the top-left cell shows the number of problems that passed both HumanEval and HumanEval Pro. The bottom-right cell shows how many failed both. Analyzing this matrix helps understand the model’s ability to transfer its code generation skills from simpler tasks to more complex, self-invoking ones.

read the caption

(d) Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-instruct

🔼 This figure presents a series of confusion matrices that visually represent the performance of various LLMs (Large Language Models) on code generation tasks. Each matrix compares the model’s performance on a standard code generation benchmark (HumanEval or MBPP) against its performance on a more challenging, self-invoking variant (HumanEval Pro or MBPP Pro). The (Failed, Passed) notation signifies instances where the model failed the self-invoking task but succeeded on the original task. This allows for a detailed analysis of the model’s ability to leverage previously generated code to solve more complex problems, highlighting potential weaknesses in their progressive reasoning capabilities. The matrices provide a visual way to compare the error patterns across different LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 5: The confusion matrix of different models. We use (Failed, Passed) to indicate samples that fail in HumanEval Pro (or MBPP Pro) but pass in HumanEval (or MBPP).

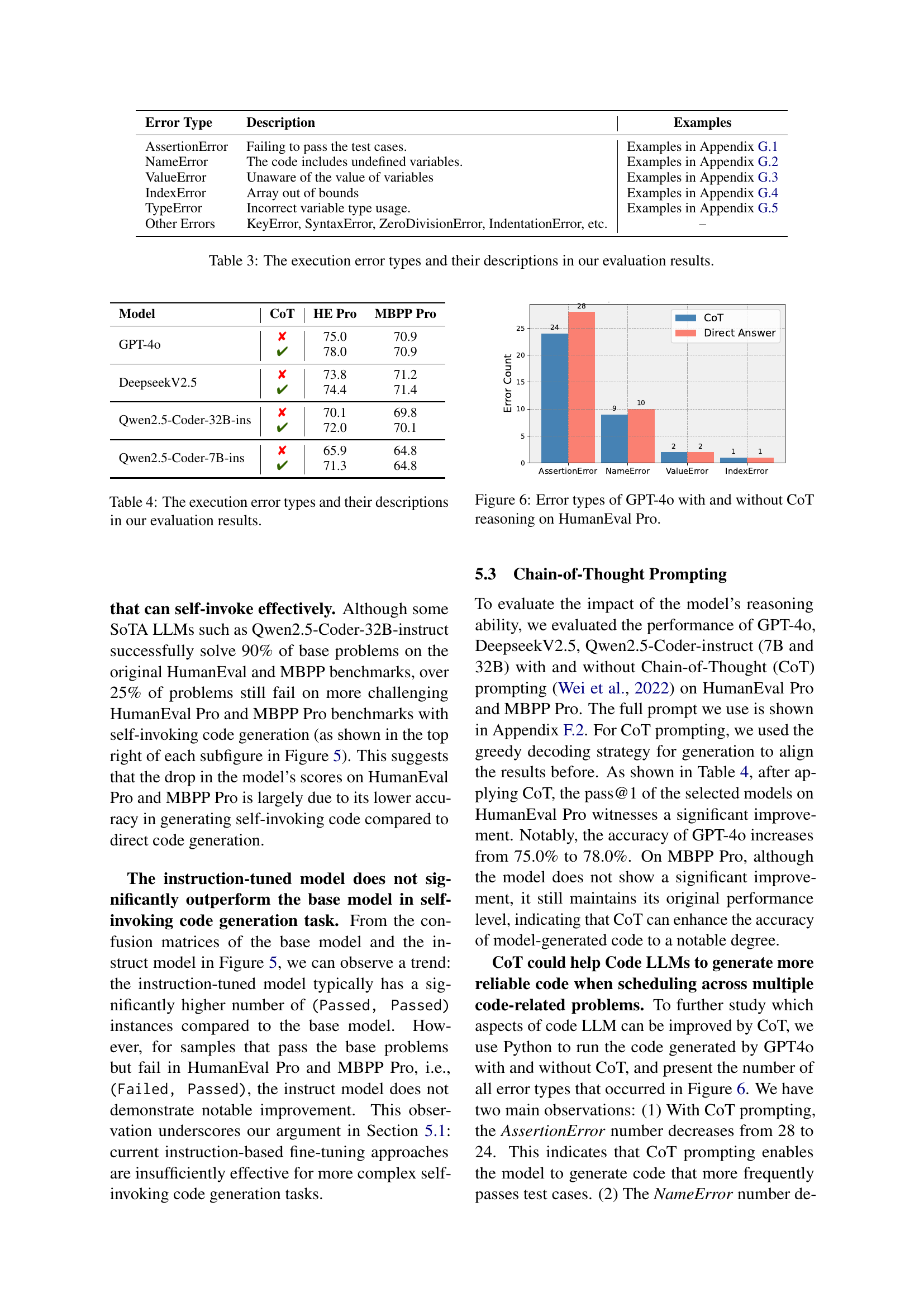

🔼 Figure 6 shows a bar chart comparing the types and counts of errors generated by GPT-40 on HumanEval Pro, with and without the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting technique. The chart visually represents the impact of CoT prompting on reducing specific error types such as AssertionError and NameError in the generated code, offering insights into how the reasoning capability of LLMs affects code generation quality.

read the caption

Figure 6: Error types of GPT-4o with and without CoT reasoning on HumanEval Pro.

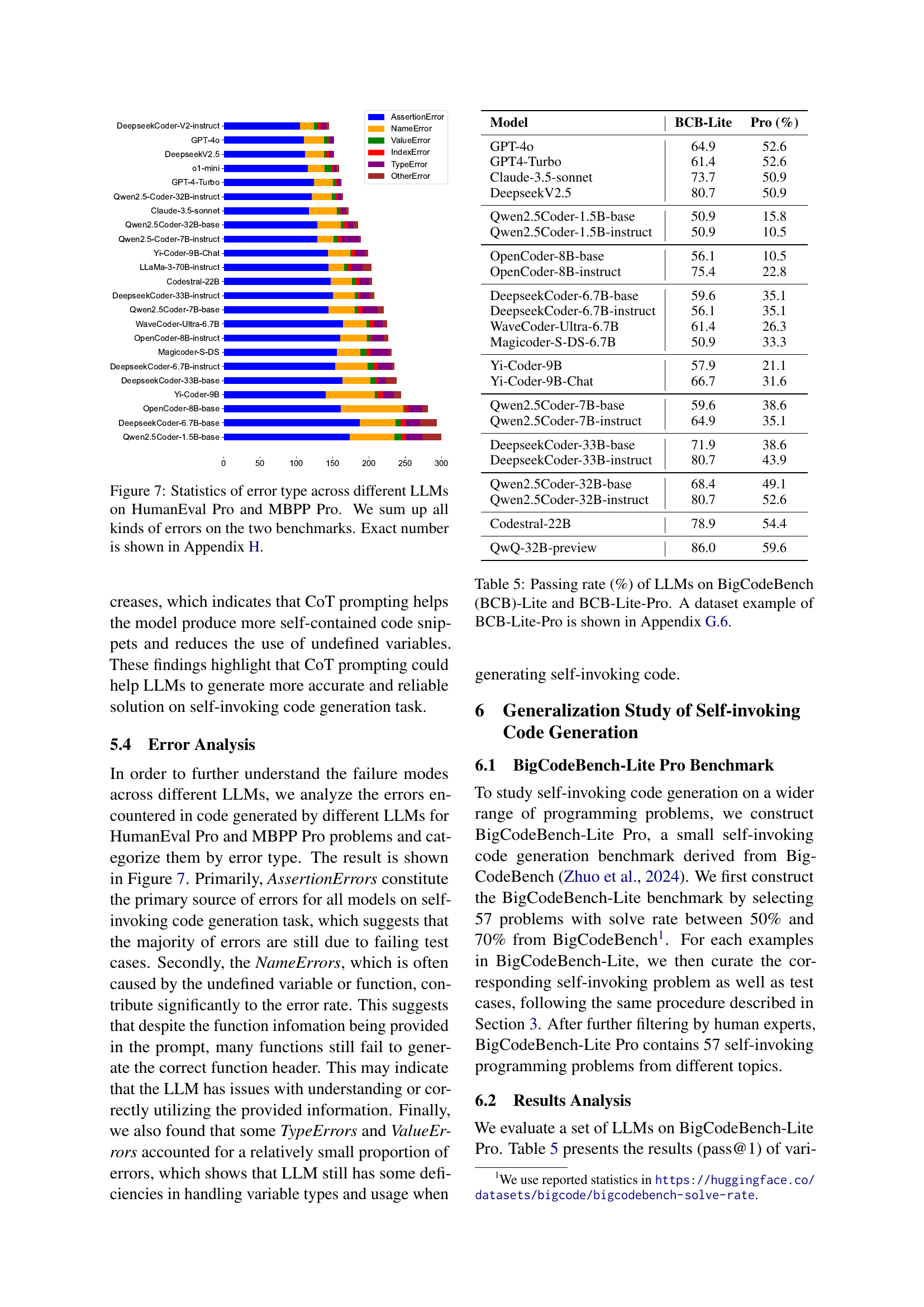

🔼 This figure displays a bar chart visualizing the frequency of different error types generated by various Large Language Models (LLMs) when completing HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro tasks. Each bar represents an LLM, and its height reflects the total number of errors encountered across both benchmarks. The chart categorizes the errors into six types: AssertionError, NameError, ValueError, IndexError, TypeError, and Other Errors. This allows for a comparison of the relative strengths and weaknesses of different LLMs in handling various types of coding errors within the context of self-invoking code generation.

read the caption

Figure 7: Statistics of error type across different LLMs on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro. We sum up all kinds of errors on the two benchmarks. Exact number is shown in Table 9.

More on tables

| Model | Params | HumanEval (+) | HumanEval Pro (0-shot) | HumanEval Pro (1-shot) | MBPP (+) | MBPP Pro (0-shot) | MBPP Pro (1-shot) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proprietary Models | |||||||

| o1-mini | - | 97.6 (90.2) | 76.2 | 84.8 | 93.9 (78.3) | 68.3 | 81.2 |

| GPT-4o | - | 90.2 (86.0) | 75.0 | 77.4 | 86.8 (72.5) | 70.9 | 80.2 |

| GPT-4-Turbo | - | 90.2 (86.6) | 72.0 | 76.2 | 85.7 (73.3) | 69.3 | 73.3 |

| Claude-3.5-sonnet | - | 92.1 (86.0) | 72.6 | 79.9 | 91.0 (74.6) | 66.4 | 76.2 |

| Open-source Models | |||||||

| Deepseek-V2.5 | - | 90.2 (83.5) | 73.8 | 76.8 | 87.6 (74.1) | 71.2 | 77.5 |

| DeepseekCoder-V2-instruct | 21/236B | 90.2 (84.8) | 77.4 | 82.3 | 89.4 (76.2) | 71.4 | 76.5 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-1.5B-base | 1.5B | 43.9 (36.6) | 37.2 | 39.6 | 69.2 (58.6) | 48.4 | 51.3 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-1.5B-instruct | 1.5B | 70.7 (66.5) | 33.5 | 37.8 | 69.2 (59.4) | 42.1 | 43.7 |

| DeepseekCoder-6.7B-base | 6.7B | 49.4 (39.6) | 35.4 | 36.6 | 70.2 (51.6) | 50.5 | 55.0 |

| DeepseekCoder-6.7B-instruct | 6.7B | 78.6 (71.3) | 55.5 | 61.6 | 74.9 (65.6) | 57.1 | 58.2 |

| Magicoder-S-DS-6.7B | 6.7B | 76.8 (70.7) | 54.3 | 56.7 | 75.7 (64.4) | 58.7 | 64.6 |

| WaveCoder-Ultra-6.7B | 6.7B | 78.6 (69.5) | 54.9 | 59.8 | 74.9 (63.5) | 60.1 | 64.6 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-base | 7B | 61.6 (53.0) | 54.9 | 56.1 | 76.9 (62.9) | 61.4 | 68.0 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-instruct | 7B | 88.4 (84.1) | 65.9 | 67.1 | 83.5 (71.7) | 64.8 | 69.8 |

| OpenCoder-8B-base | 8B | 66.5 (63.4) | 39.0 | 42.1 | 79.9 (70.4) | 52.4 | 53.7 |

| OpenCoder-8B-instruct | 8B | 83.5 (78.7) | 59.1 | 54.9 | 79.1 (69.0) | 57.9 | 61.4 |

| Yi-Coder-9B-base | 9B | 53.7 (46.3) | 42.7 | 50.0 | 78.3 (64.6) | 60.3 | 61.4 |

| Yi-Coder-9B-chat | 9B | 85.4 (74.4) | 59.8 | 64.0 | 81.5 (69.3) | 64.8 | 71.7 |

| Codestral-22B-v0.1 | 22B | 81.1 (73.2) | 59.1 | 65.9 | 78.2 (62.2) | 63.8 | 71.2 |

| DeepseekCoder-33B-base | 33B | 56.1 (47.6) | 49.4 | 49.4 | 74.2 (60.7) | 59.0 | 65.1 |

| DeepseekCoder-33B-instruct | 33B | 79.3 (75.0) | 56.7 | 62.8 | 80.4 (70.1) | 64.0 | 68.3 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-base | 32B | 65.9 (60.4) | 61.6 | 67.1 | 83.0 (68.2) | 67.7 | 73.3 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-instruct | 32B | 92.7 (87.2) | 70.1 | 80.5 | 90.2 (75.1) | 69.8 | 77.5 |

| LLaMA3-70B-instruct | 70B | 81.7 (72.0) | 60.4 | 64.6 | 82.3 (69.0) | 63.5 | 70.4 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro, which are benchmarks designed to evaluate the progressive reasoning and problem-solving capabilities of LLMs. The results show the pass@1 scores (percentage of problems solved correctly on the first attempt) for each model on both benchmarks. The table includes both proprietary and open-source models, allowing for a comparison of performance across different model architectures and training approaches. Further detailed results are available in Appendix A.

read the caption

Table 2: Main result of different models on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro. More results is shown in Appendix A.

| Error Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

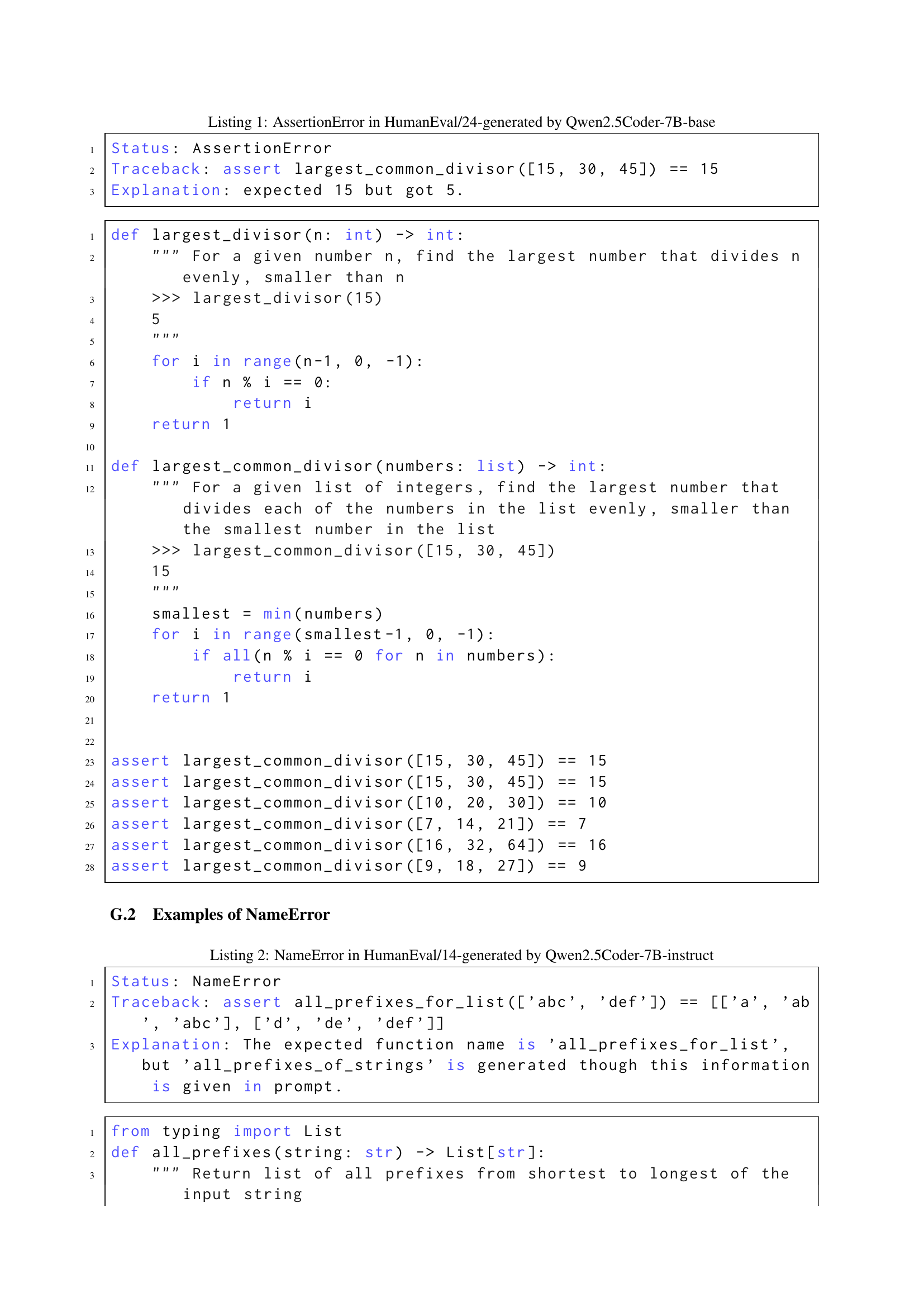

| AssertionError | Failing to pass the test cases. | Examples in Section G.1 |

| NameError | The code includes undefined variables. | Examples in Section G.2 |

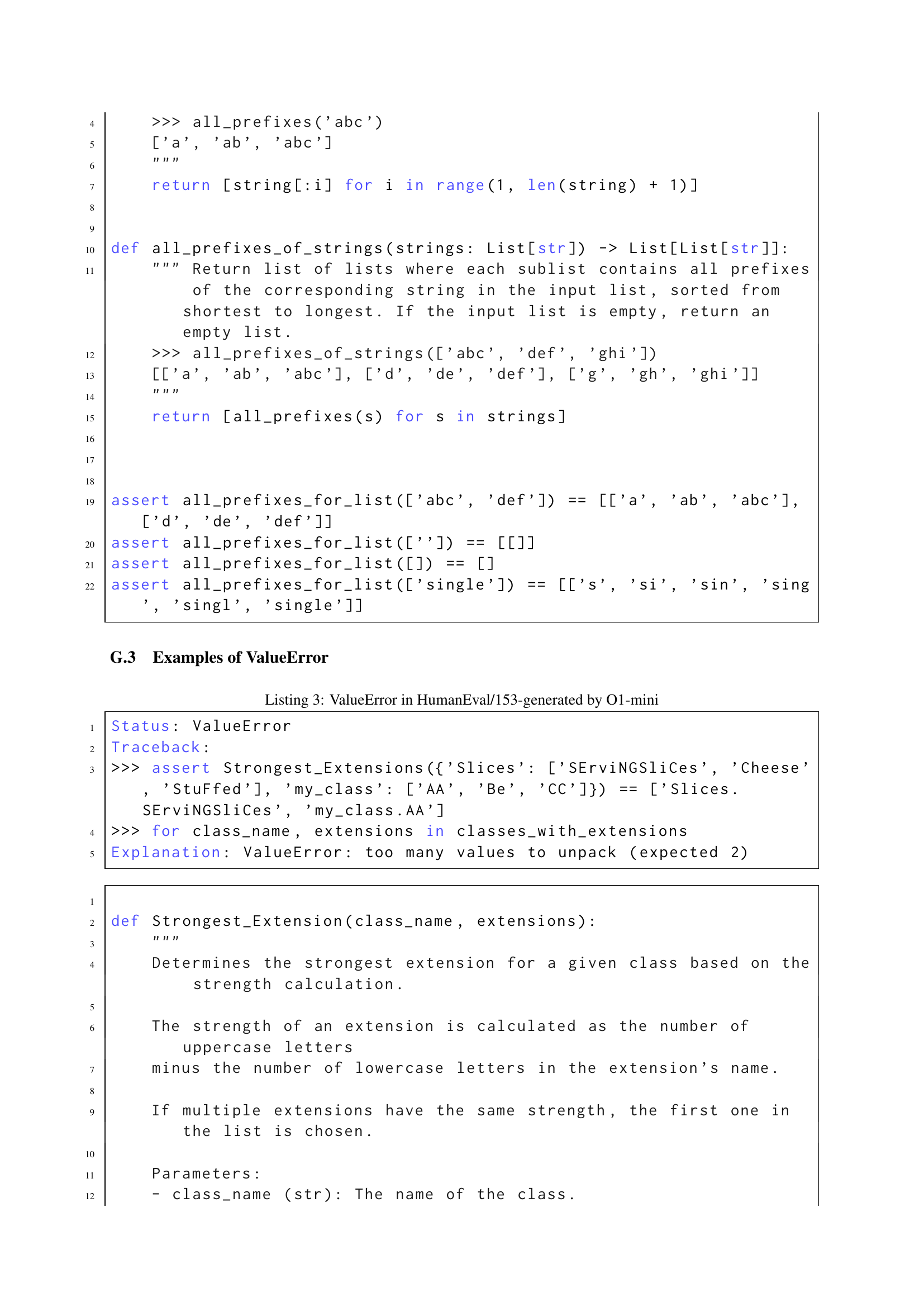

| ValueError | Unaware of the value of variables | Examples in Section G.3 |

| IndexError | Array out of bounds | Examples in Section G.4 |

| TypeError | Incorrect variable type usage. | Examples in Section G.5 |

| Other Errors | KeyError, SyntaxError, ZeroDivisionError, IndentationError, etc. | – |

🔼 This table lists the different types of errors encountered during the execution of the code generated by various large language models (LLMs) in the HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro benchmarks. For each error type, a short description is provided along with examples in the appendix. The error types are categorized to help understand common failure modes of LLMs during code generation tasks.

read the caption

Table 3: The execution error types and their descriptions in our evaluation results.

| Model | CoT | HE Pro | MBPP Pro |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | ✘ | 75.0 | 70.9 |

| GPT-4o | ✔ | 78.0 | 70.9 |

| DeepseekV2.5 | ✘ | 73.8 | 71.2 |

| DeepseekV2.5 | ✔ | 74.4 | 71.4 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-ins | ✘ | 70.1 | 69.8 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-ins | ✔ | 72.0 | 70.1 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-ins | ✘ | 65.9 | 64.8 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-ins | ✔ | 71.3 | 64.8 |

🔼 This table presents a breakdown of the different types of errors encountered during the execution of code generated by various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro benchmarks. Each error type is described, and examples can be found in the appendix. This analysis helps to identify failure modes and areas for future improvement in LLM code generation.

read the caption

Table 4: The execution error types and their descriptions in our evaluation results.

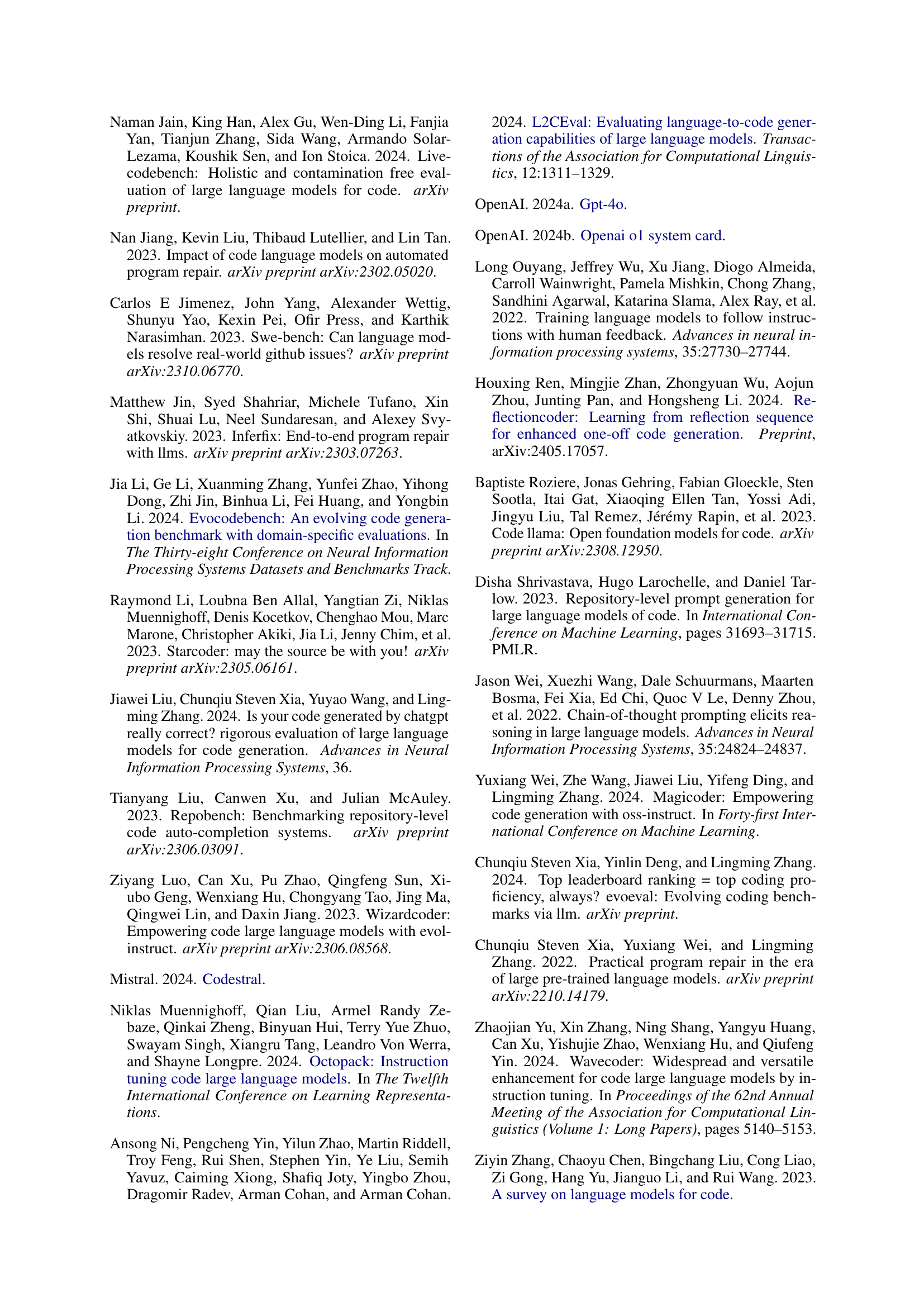

| Model | BCB-Lite | Pro (%) |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | 64.9 | 52.6 |

| GPT4-Turbo | 61.4 | 52.6 |

| Claude-3.5-sonnet | 73.7 | 50.9 |

| DeepseekV2.5 | 80.7 | 50.9 |

| Qwen2.5Coder-1.5B-base | 50.9 | 15.8 |

| Qwen2.5Coder-1.5B-instruct | 50.9 | 10.5 |

| OpenCoder-8B-base | 56.1 | 10.5 |

| OpenCoder-8B-instruct | 75.4 | 22.8 |

| DeepseekCoder-6.7B-base | 59.6 | 35.1 |

| DeepseekCoder-6.7B-instruct | 56.1 | 35.1 |

| WaveCoder-Ultra-6.7B | 61.4 | 26.3 |

| Magicoder-S-DS-6.7B | 50.9 | 33.3 |

| Yi-Coder-9B | 57.9 | 21.1 |

| Yi-Coder-9B-Chat | 66.7 | 31.6 |

| Qwen2.5Coder-7B-base | 59.6 | 38.6 |

| Qwen2.5Coder-7B-instruct | 64.9 | 35.1 |

| DeepseekCoder-33B-base | 71.9 | 38.6 |

| DeepseekCoder-33B-instruct | 80.7 | 43.9 |

| Qwen2.5Coder-32B-base | 68.4 | 49.1 |

| Qwen2.5Coder-32B-instruct | 80.7 | 52.6 |

| Codestral-22B | 78.9 | 54.4 |

| QwQ-32B-preview | 86.0 | 59.6 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on two code generation benchmarks: BigCodeBench-Lite and its extended self-invoking version, BigCodeBench-Lite Pro. The passing rate, expressed as a percentage, indicates the success rate of each LLM in correctly solving the code generation problems within each benchmark. The self-invoking nature of BigCodeBench-Lite Pro adds a layer of complexity compared to the original BigCodeBench-Lite, requiring LLMs to not only generate code but also effectively utilize previously generated functions to solve more intricate problems. Section G.6 provides an example of a problem from the BigCodeBench-Lite Pro dataset.

read the caption

Table 5: Passing rate (%) of LLMs on BigCodeBench (BCB)-Lite and BCB-Lite-Pro. A dataset example of BCB-Lite-Pro is shown in Section G.6.

| Model | HumanEval Pro (0-shot) | MBPP Pro (0-shot) |

|---|---|---|

| LLaMA-3.1-8B-base | 25.0 | 36.5 |

| LLaMA-3.1-8B-instruct | 45.7 | 53.7 |

| LLaMA-3.1-70B-base | 40.9 | 57.4 |

| LLaMA-3.1-70B-instruct | 60.4 | 63.8 |

| Qwen-2.5-72B-base | 62.2 | 65.3 |

| Qwen-2.5-72B-instruct | 68.9 | 68.8 |

| QwQ-32B-preview | 72.0 | 67.5 |

| LLaMA-3.3-70B-instruct | 67.1 | 64.6 |

| Mistral-Large-instruct-2411 | 75.0 | 69.3 |

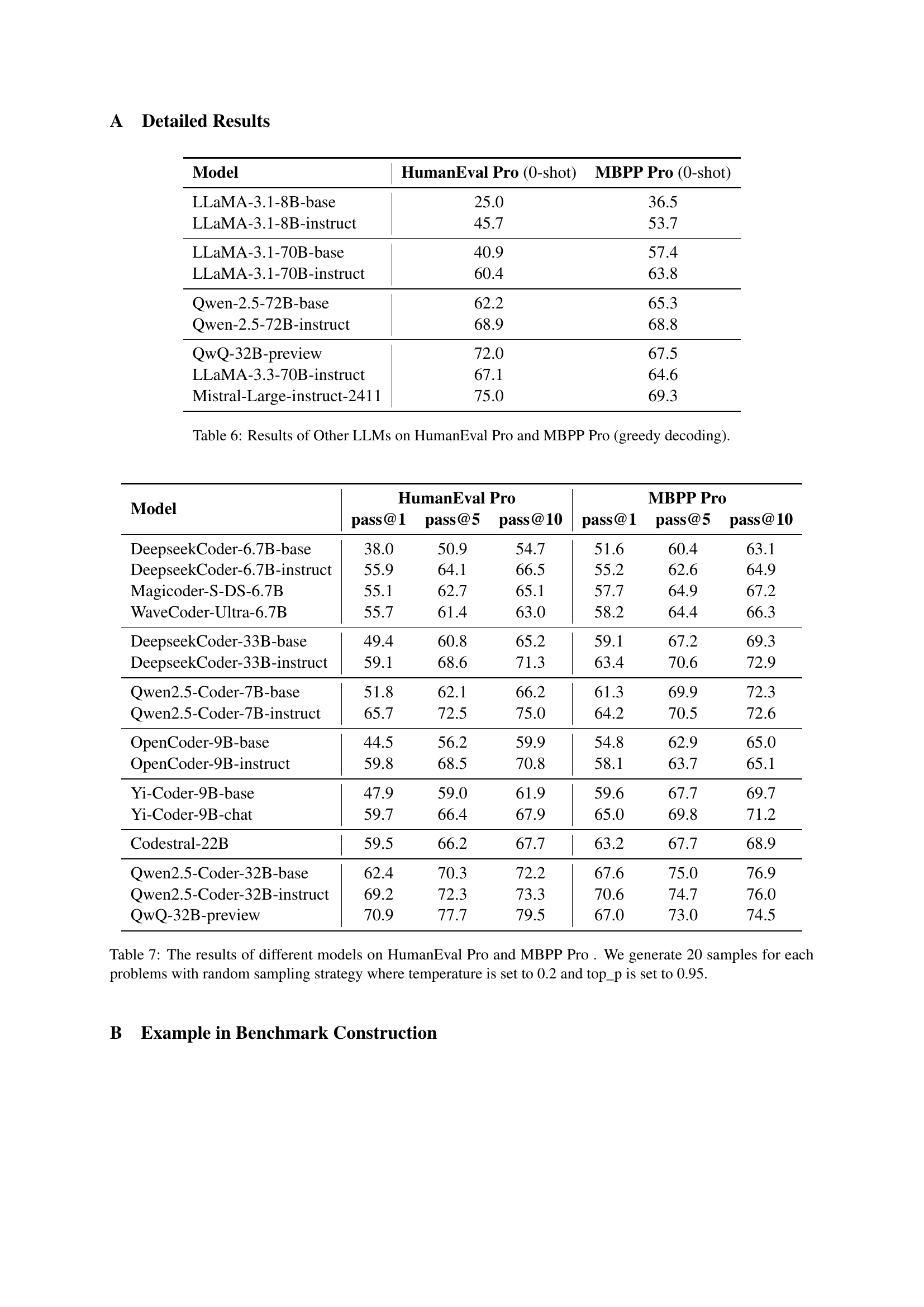

🔼 This table presents the results of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro benchmarks using greedy decoding. It shows the pass rate for each model on these two benchmarks, offering a comparison of performance across different LLMs and highlighting the challenges posed by these more complex, self-invoking code generation tasks.

read the caption

Table 6: Results of Other LLMs on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro (greedy decoding).

| Model | HumanEval Pro | MBPP Pro | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pass@1 | pass@5 | pass@10 | pass@1 | pass@5 | pass@10 | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DeepseekCoder-6.7B-base | 38.0 | 50.9 | 54.7 | 51.6 | 60.4 | 63.1 |

| DeepseekCoder-6.7B-instruct | 55.9 | 64.1 | 66.5 | 55.2 | 62.6 | 64.9 |

| Magicoder-S-DS-6.7B | 55.1 | 62.7 | 65.1 | 57.7 | 64.9 | 67.2 |

| WaveCoder-Ultra-6.7B | 55.7 | 61.4 | 63.0 | 58.2 | 64.4 | 66.3 |

| DeepseekCoder-33B-base | 49.4 | 60.8 | 65.2 | 59.1 | 67.2 | 69.3 |

| DeepseekCoder-33B-instruct | 59.1 | 68.6 | 71.3 | 63.4 | 70.6 | 72.9 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-base | 51.8 | 62.1 | 66.2 | 61.3 | 69.9 | 72.3 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-instruct | 65.7 | 72.5 | 75.0 | 64.2 | 70.5 | 72.6 |

| OpenCoder-9B-base | 44.5 | 56.2 | 59.9 | 54.8 | 62.9 | 65.0 |

| OpenCoder-9B-instruct | 59.8 | 68.5 | 70.8 | 58.1 | 63.7 | 65.1 |

| Yi-Coder-9B-base | 47.9 | 59.0 | 61.9 | 59.6 | 67.7 | 69.7 |

| Yi-Coder-9B-chat | 59.7 | 66.4 | 67.9 | 65.0 | 69.8 | 71.2 |

| Codestral-22B | 59.5 | 66.2 | 67.7 | 63.2 | 67.7 | 68.9 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-base | 62.4 | 70.3 | 72.2 | 67.6 | 75.0 | 76.9 |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B-instruct | 69.2 | 72.3 | 73.3 | 70.6 | 74.7 | 76.0 |

| QwQ-32B-preview | 70.9 | 77.7 | 79.5 | 67.0 | 73.0 | 74.5 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro, which are more challenging benchmarks designed to assess the progressive reasoning and problem-solving capabilities of LLMs through self-invoking code generation tasks. The results show the pass rate (@1, @5, @10) for each model, indicating the percentage of times the model generated a correct solution within the top 1, 5, or 10 predictions. The evaluation methodology involves generating 20 samples per problem using a random sampling strategy with a temperature of 0.2 and top_p of 0.95 to ensure diversity and robustness in the results.

read the caption

Table 7: The results of different models on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro . We generate 20 samples for each problems with random sampling strategy where temperature is set to 0.2 and top_p is set to 0.95.

| Model Name | API Name |

|---|---|

| O1-mini | o1-mini-2024-09-12 |

| GPT-4o | gpt-4o-2024-08-06 |

| GPT-4-Turbo | gpt-4-turbo-2024-04-09 |

| Claude-3.5-sonnet | claude-3-5-sonnet-20241022 |

| Deepseek-V2.5 | deepseek-chat |

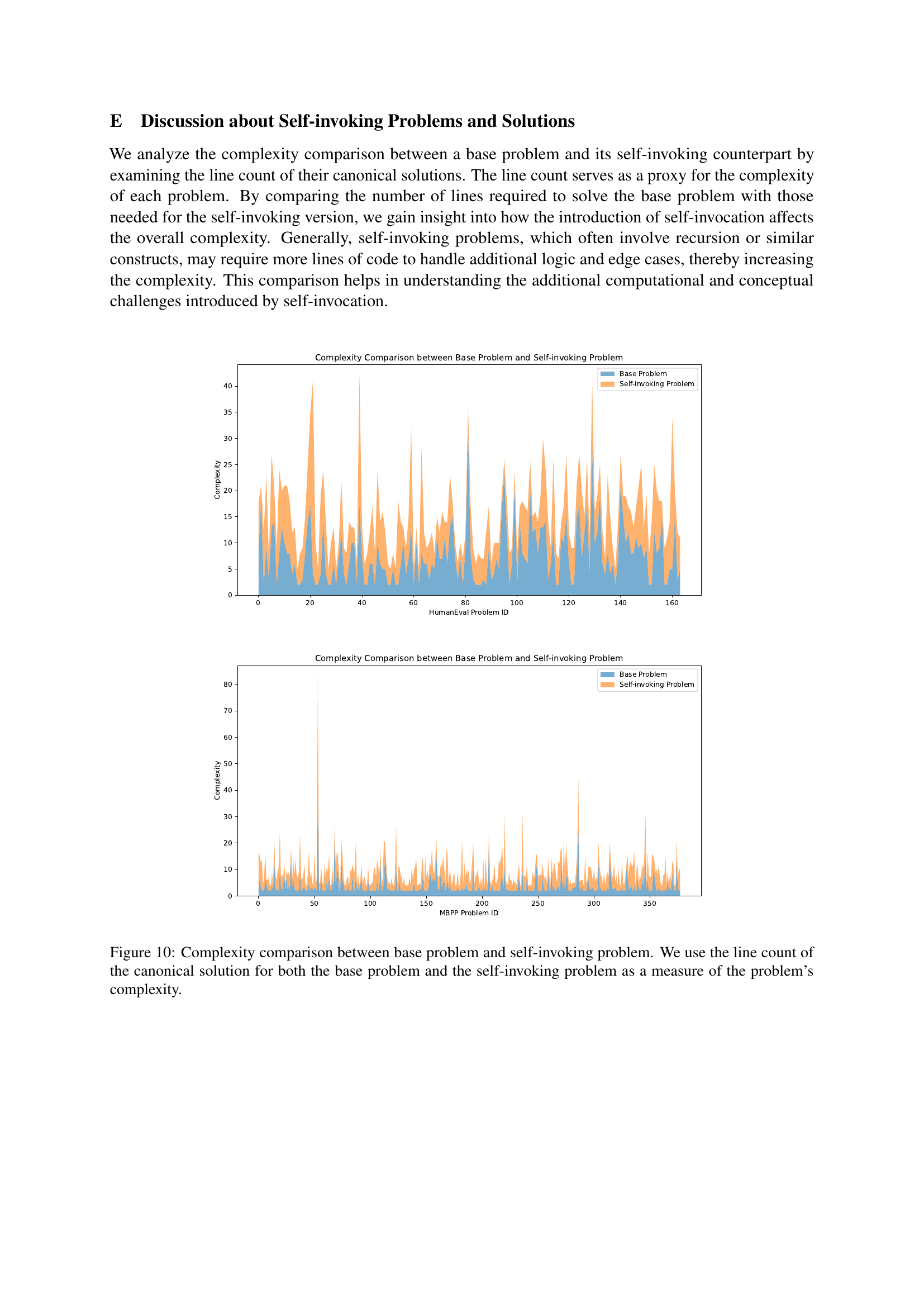

🔼 This table provides a mapping between the model names used in the paper and their corresponding API names and Hugging Face model URLs. This allows for easy reference and reproducibility of the experiments, as readers can directly access the models using the provided URLs.

read the caption

Table 8: The corresponding API names and HuggingFace model URLs for the evaluated models are listed in Table 2.

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the different types of errors encountered by various large language models (LLMs) while attempting to solve problems in the HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro benchmarks. The error types include AssertionErrors (test failures), NameErrors (undefined variable issues), ValueErrors (incorrect values), IndexErrors (array out-of-bounds errors), TypeErrors (type mismatch problems), and Other Errors (other types of errors). The table allows for a comparison of error frequencies among different LLMs and across the two benchmarks. This provides insights into the specific challenges and failure modes of LLMs in the self-invoking code generation task.

read the caption

Table 9: Error type of Different Models on HumanEval Pro and MBPP Pro.

Full paper#