TL;DR#

Existing Video LLMs lack fine-grained spatial-temporal understanding due to limited high-quality data and comprehensive benchmarks. This paper introduces the VideoRefer Suite to address this, comprising three key components: a new dataset (VideoRefer-700K) with high-quality object-level video instructions, a novel VideoRefer model with a versatile spatial-temporal object encoder, and a benchmark (VideoRefer-Bench) for comprehensive evaluation.

The VideoRefer model significantly improves upon existing methods in various video understanding tasks. The new dataset and benchmark provide valuable resources for the research community to advance the state-of-the-art in video understanding. The results showcase the effectiveness of the VideoRefer model and the importance of high-quality data and comprehensive evaluation in achieving fine-grained video understanding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in video understanding and large language models. It introduces a novel benchmark and model that significantly advances spatial-temporal object understanding, a currently under-addressed area. This research opens new avenues for developing more sophisticated video LLMs capable of fine-grained object-level analysis and complex reasoning, bridging a key gap in current video understanding capabilities. The high-quality dataset further fuels advancements in the field.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 compares VideoRefer to other general and specialized Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for video understanding. It highlights VideoRefer’s superiority in handling fine-grained spatial and temporal details within videos, outperforming other methods on three key tasks: video object referring (identifying and describing specific objects), complex video relationship analysis (understanding interactions between multiple objects), and video object retrieval (locating objects within the video based on textual descriptions). The figure visually demonstrates these capabilities, showing how VideoRefer excels compared to previous models which primarily focused on holistic video understanding.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparisons with previous general and specialized MLLMs. Our VideoRefer excels in multiple fine-grained regional and temporal video understanding tasks, including basic video object referring, complex video relationship analysis, and video object retrieval.

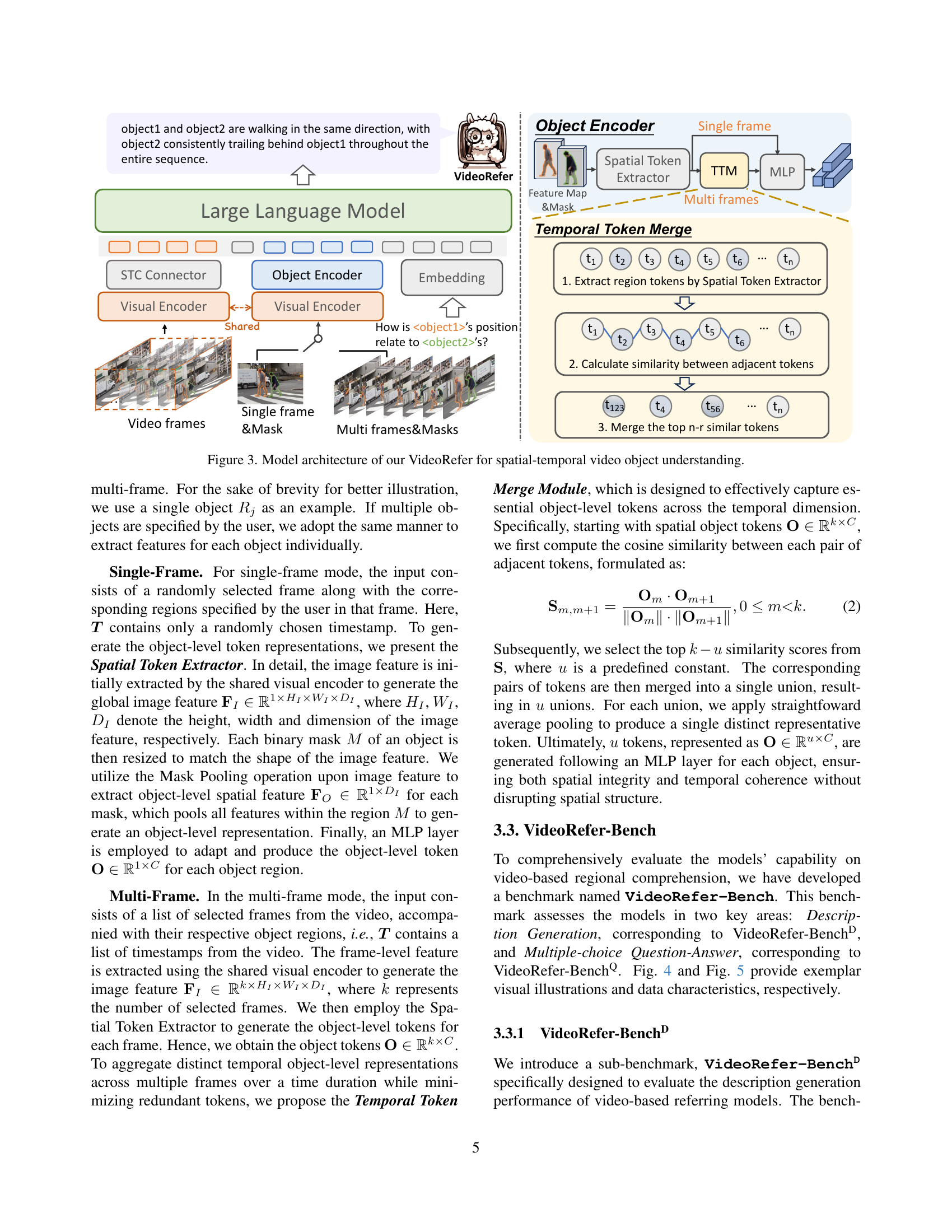

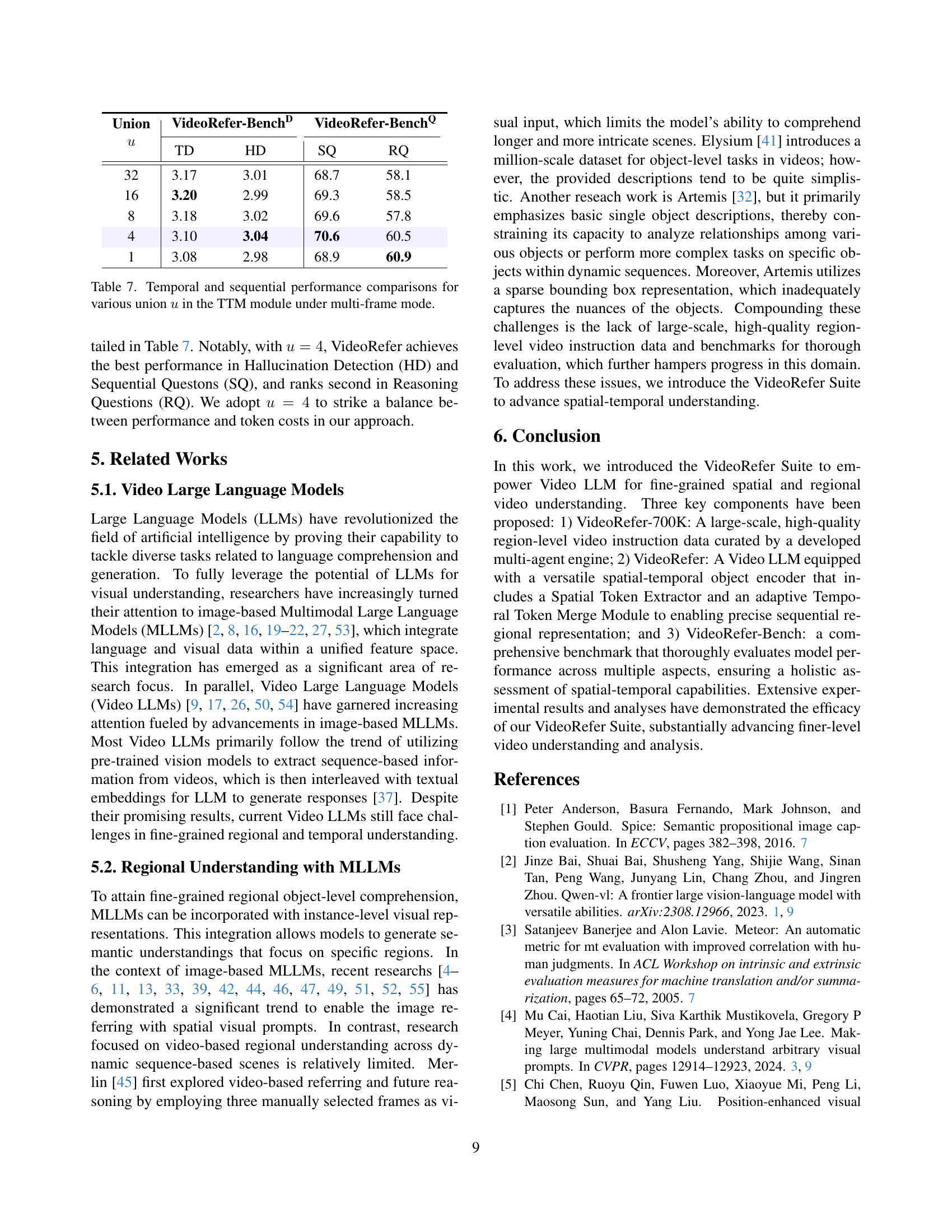

| Method | Single-Frame SC | Single-Frame AD | Single-Frame TD | Single-Frame HD | Single-Frame Avg. | Multi-Frame SC | Multi-Frame AD | Multi-Frame TD | Multi-Frame HD | Multi-Frame Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalist Models | ||||||||||

| GPT-4o [28] | 3.34 | 2.96 | 3.01 | 2.50 | 2.95 | 4.15 | 3.31 | 3.11 | 2.43 | 3.25 |

| GPT-4o-mini [28] | 3.56 | 2.85 | 2.87 | 2.38 | 2.92 | 3.89 | 3.18 | 2.62 | 2.50 | 3.05 |

| InternVL2-26B [8] | 3.55 | 2.99 | 2.57 | 2.25 | 2.84 | 4.08 | 3.35 | 3.08 | 2.28 | 3.20 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B [43] | 2.97 | 2.24 | 2.03 | 2.31 | 2.39 | 3.30 | 2.54 | 2.22 | 2.12 | 2.55 |

| Specialist Models | ||||||||||

| Image-level models | ||||||||||

| Osprey-7B [46] | 3.19 | 2.16 | 1.54 | 2.45 | 2.34 | 3.30 | 2.66 | 2.10 | 1.58 | 2.41 |

| Ferret-7B [44] | 3.08 | 2.01 | 1.54 | 2.14 | 2.19 | 3.20 | 2.38 | 1.97 | 1.38 | 2.23 |

| Video-level models | ||||||||||

| Elysium-7B [41] | 2.35 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 3.59 | 1.57 | |||||

| Artemis-7B [32] | 3.42 | 1.34 | 1.39 | 2.90 | 2.26 | |||||

| VideoRefer-7B | 4.41 | 3.27 | 3.03 | 2.97 | 3.42 | 4.44 | 3.27 | 3.10 | 3.04 | 3.46 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different models’ performance on the VideoRefer-BenchD benchmark, focusing on four evaluation metrics (Subject Correspondence (SC), Appearance Description (AD), Temporal Description (TD), and Hallucination Detection (HD)). It compares both generalist and specialist models (image-level and video-level) in both single-frame and multi-frame settings. The best and second-best results for each model are highlighted, and ‘-’ indicates models that don’t support a specific input type. Grey entries show results where model input was modified to include manually overlaid target masks, allowing for comparison where the original method couldn’t process the data.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparisons on VideoRefer-BenchDD{}^{\text{D}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT D end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT. The best results are bold and the second-best results are underlined. “–” means that the model does not support the certain input form. Grey entries denote cases where the original method cannot accomplish the task; for these tests, masks of the targets were overlaid on the original video (the same below).

In-depth insights#

VideoLLM Advancements#

VideoLLM advancements are pushing the boundaries of video understanding, moving beyond holistic scene comprehension to fine-grained spatial-temporal analysis. Early VideoLLMs struggled with detailed object-level understanding, lacking the capacity to accurately describe specific objects or their interactions within a video. Recent work, however, addresses these limitations through the development of high-quality object-level video instruction datasets. These datasets enable training of models capable of precise regional and sequential representations, facilitating accurate object descriptions and complex reasoning. Multi-agent data engines are key to generating diverse and nuanced annotations for video content, significantly improving model performance on benchmarks assessing various aspects of video understanding, including object referring, relationship analysis, and even future prediction. The integration of spatial-temporal object encoders, alongside advancements in large language models, is critical to these advancements, suggesting that the future of VideoLLMs lies in combining powerful LLMs with robust visual encoders specifically designed to handle the complexities of video data.

VideoRefer Suite#

The “VideoRefer Suite” represents a comprehensive approach to enhance video large language model (LLM) capabilities for spatial-temporal object understanding. It tackles the limitations of existing Video LLMs which struggle with fine-grained details and lack high-quality object-level data. The suite introduces three key components: a meticulously curated large-scale dataset (VideoRefer-700K), a novel Video LLM architecture (VideoRefer) with versatile spatial-temporal object encoders, and a thorough benchmark (VideoRefer-Bench) for comprehensive evaluation. VideoRefer-700K’s multi-agent data engine ensures high-quality object-level annotations, enabling finer-level instruction following. The VideoRefer model leverages a unified spatial-temporal encoder for precise regional and sequential representations, while the VideoRefer-Bench allows for robust evaluation across diverse aspects of spatial-temporal understanding. This holistic approach promises significant advancements in the field, pushing the boundaries of Video LLM capabilities for nuanced video comprehension.

Multi-agent Engine#

A multi-agent engine, in the context of a video understanding research paper, is a sophisticated system designed to generate high-quality training data. Instead of relying on a single model, it leverages the strengths of multiple specialized models working collaboratively. This approach tackles the complexities of video annotation by breaking down the task into smaller, manageable sub-tasks. Each agent focuses on a specific aspect, such as object detection, caption generation, or mask creation. The collaborative nature of this engine ensures better accuracy and diversity in the resulting dataset. The use of multiple models compensates for the individual limitations of each, creating a more robust and reliable method for generating high-quality data for video LLMs. The output data is typically multi-modal, including detailed image regions, refined captions, and even QA pairs, providing rich training examples for fine-grained video understanding.

Benchmarking LLMs#

Benchmarking LLMs is crucial for evaluating their capabilities and progress. A robust benchmark should encompass a range of tasks reflecting real-world applications, including text generation, question answering, translation, and reasoning. Furthermore, it needs to consider various aspects such as accuracy, fluency, coherence, and bias. The choice of metrics is equally vital; while automated metrics offer efficiency, human evaluation remains necessary to capture nuanced aspects of language understanding. Data sets used for benchmarking must be diverse and representative, avoiding biases that might skew results. Finally, transparency and reproducibility are paramount; detailed documentation of the benchmark’s design, data, and evaluation methods is essential for the community to validate results and build upon previous work. A well-designed benchmarking framework fosters a healthy competition among LLM developers, driving progress towards more capable and reliable language models.

Future Work#

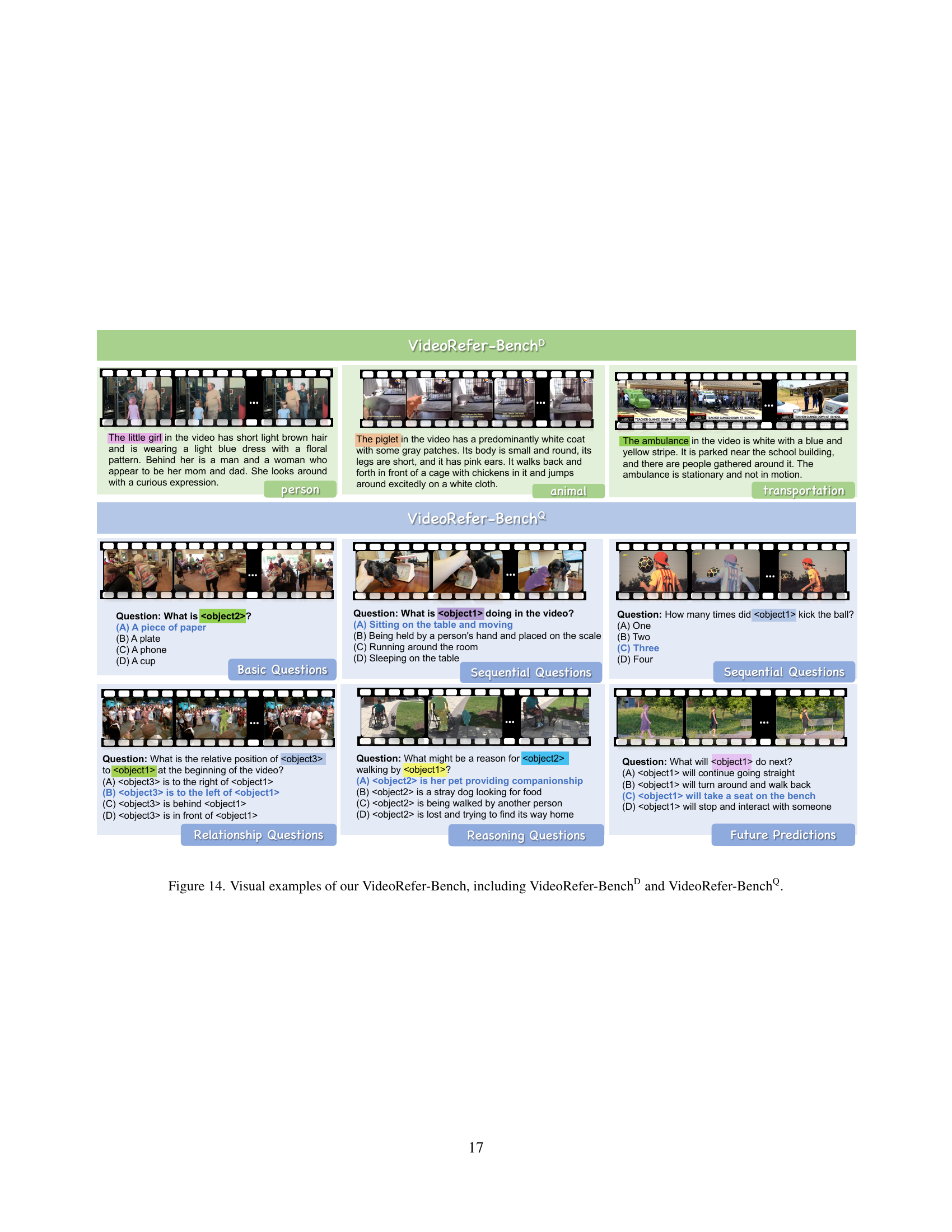

The ‘Future Work’ section of a research paper on Video Referencing would ideally outline several key directions. Extending the VideoRefer suite to encompass grounding capabilities is crucial, bridging the gap between object-level understanding and real-world applications. This would involve refining the model to accurately identify and associate objects within dynamic contexts, which is currently a limitation. Developing a more robust benchmark for evaluating video referencing models is also important. The current VideoRefer-Bench could be expanded to include a wider range of tasks and complexities, addressing more nuanced aspects of temporal and spatial reasoning. Further research into improving the efficiency and scalability of the multi-agent data engine used to generate the VideoRefer-700K dataset is warranted. Optimizing the engine for greater speed and resource efficiency is essential for facilitating broader adoption. Finally, exploring applications beyond video captioning, such as interactive video comprehension and predictive reasoning, would demonstrate the wider applicability and potential of this approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the multi-agent data engine used to create the VideoRefer-700K dataset. The engine leverages several expert models working collaboratively to generate high-quality object-level video instruction data. The steps involved include analyzing the video for nouns, generating object-level captions, creating pixel-level masks for objects, verifying the accuracy of the annotations, and refining the final captions. This process results in a dataset with detailed captions, short captions, and multi-round QA pairs for each object across multiple video frames.

read the caption

Figure 2: A multi-agent data engine for the construction of our VideoRefer-700K.

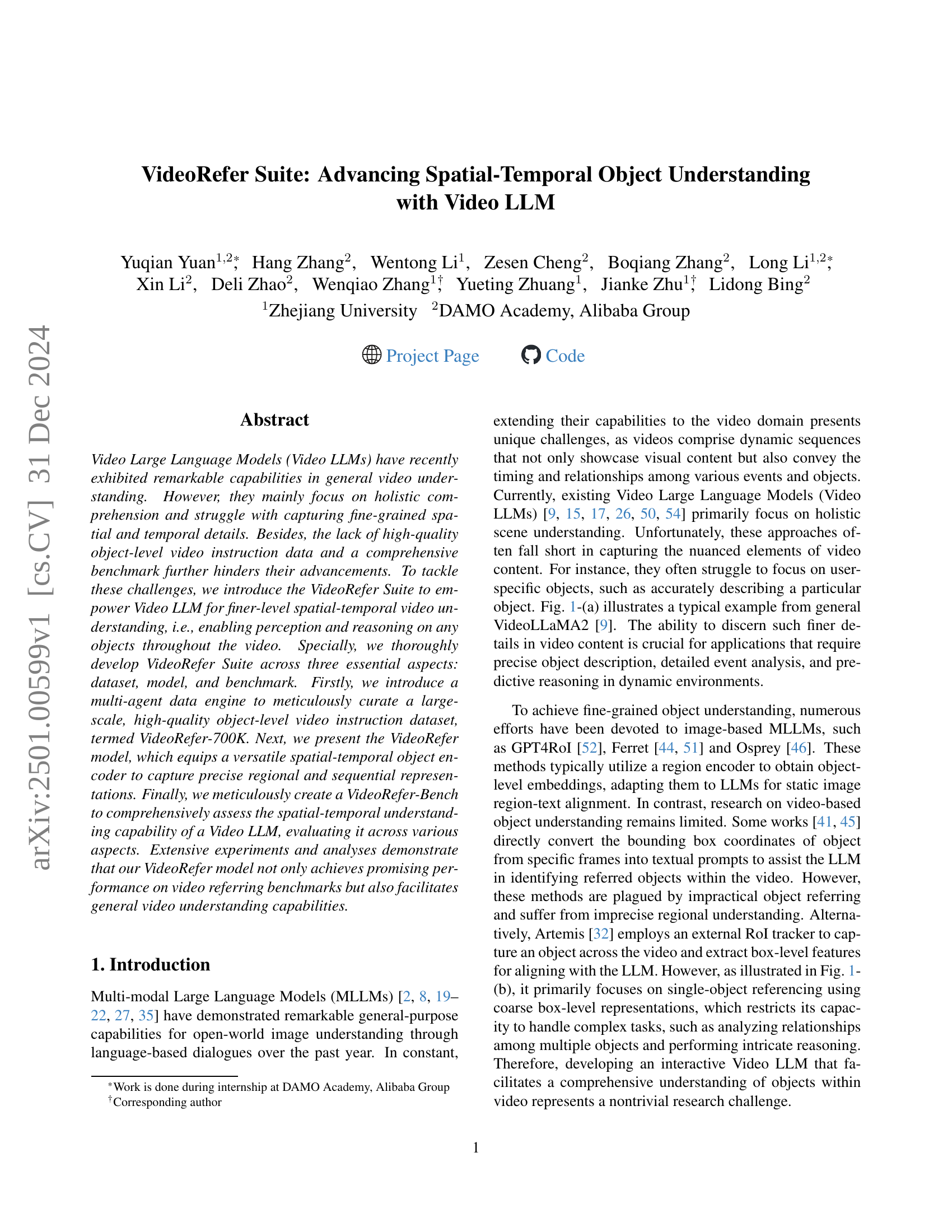

🔼 This figure details the architecture of the VideoRefer model, designed for comprehensive spatial-temporal understanding in videos. It illustrates how the model processes both single-frame and multi-frame video data to generate object-level representations. The model incorporates a shared visual encoder, a versatile spatial-temporal object encoder (consisting of a Spatial Token Extractor and a Temporal Token Merge Module), and an instruction-following large language model (LLM). The object encoder handles free-form input regions and merges temporal information from multiple frames. The final output is generated by the LLM, which integrates image-level, object-level, and linguistic embeddings.

read the caption

Figure 3: Model architecture of our VideoRefer for spatial-temporal video object understanding.

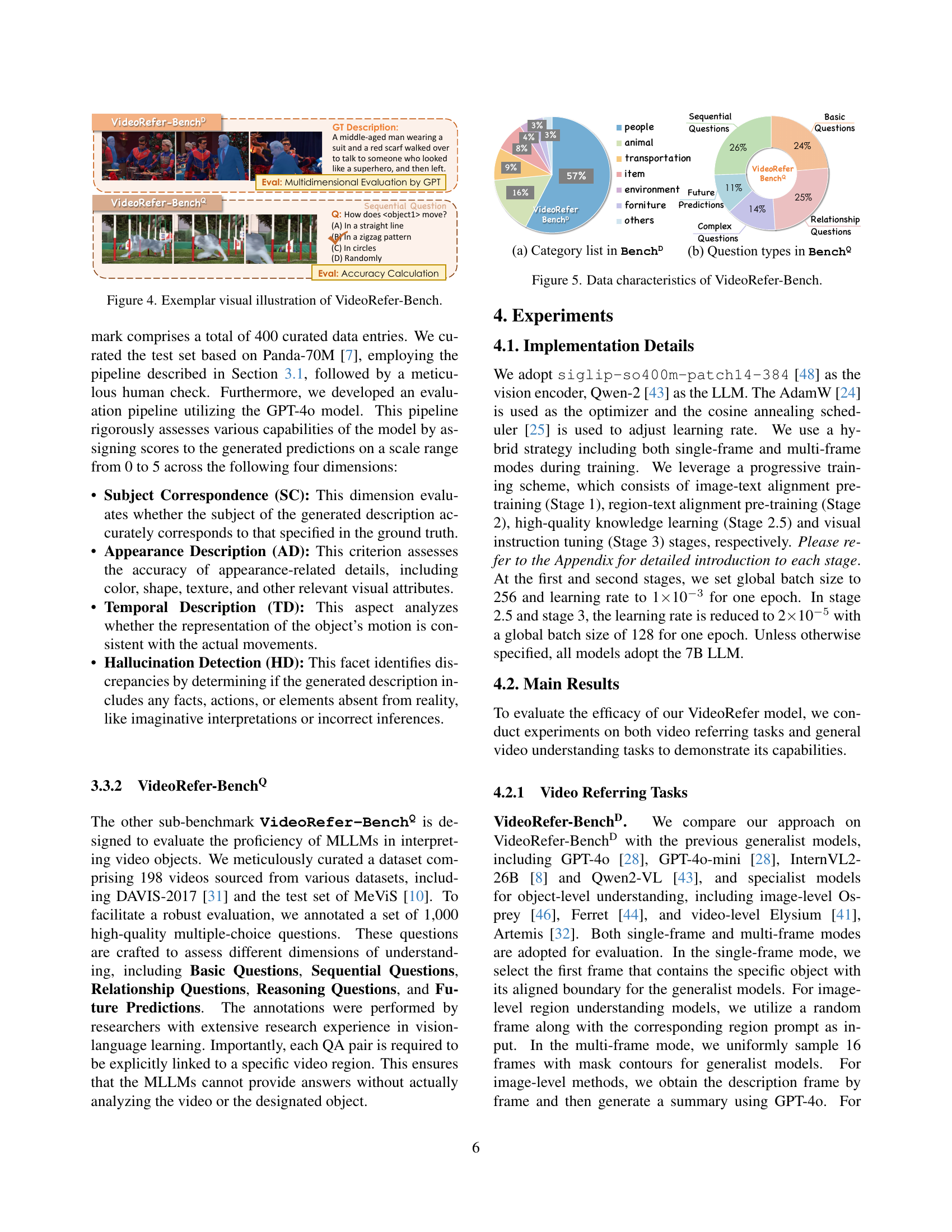

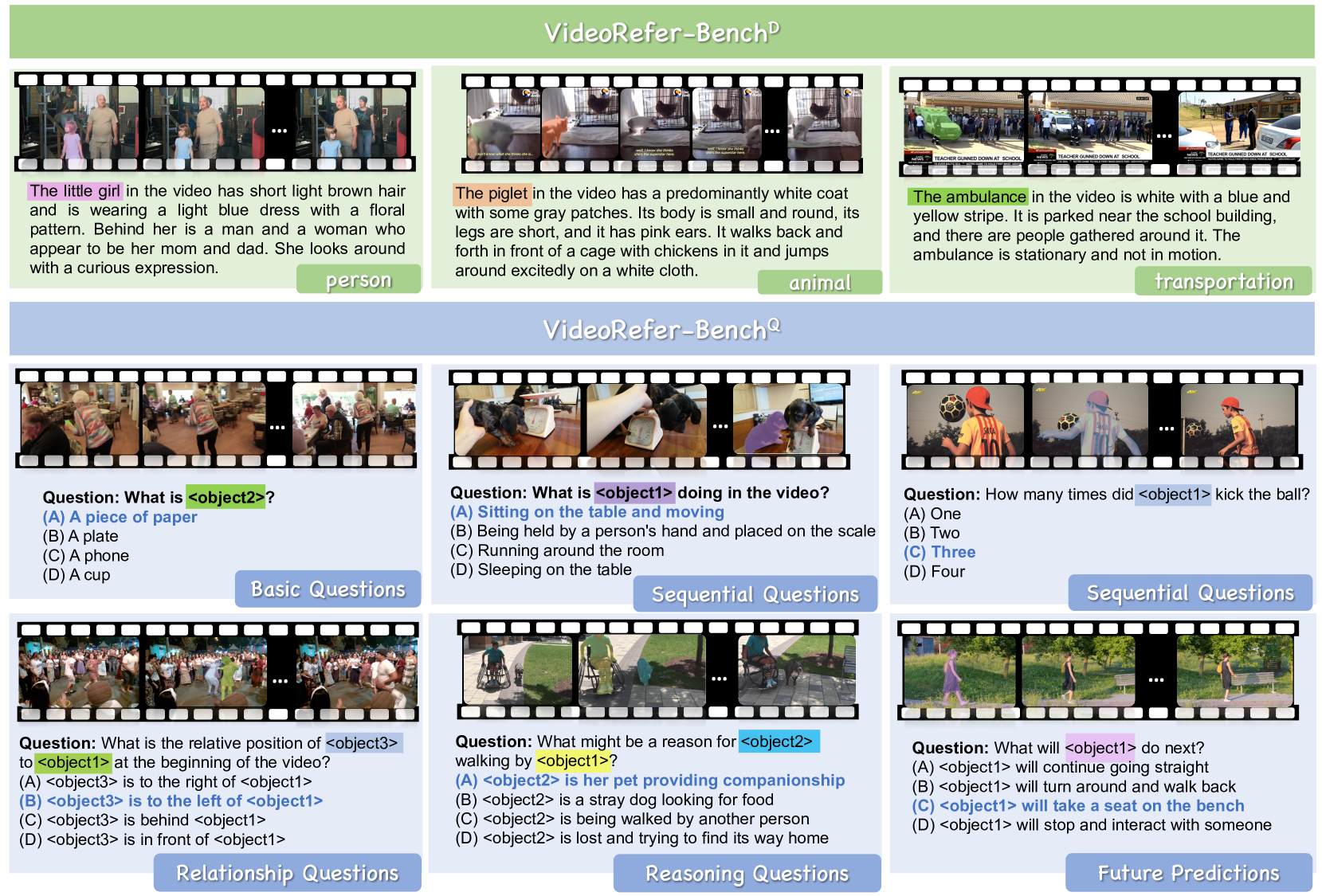

🔼 Figure 4 is a visual representation of the VideoRefer-Bench benchmark. It shows example queries and their corresponding ground truth descriptions for different aspects of video understanding, such as single-object descriptions, complex reasoning, and future prediction. The figure highlights the multidimensional nature of the benchmark, illustrating how it evaluates different aspects of video comprehension.

read the caption

Figure 4: Exemplar visual illustration of VideoRefer-Bench.

🔼 This figure presents a detailed breakdown of the data characteristics used in the VideoRefer-Bench benchmark. Specifically, it shows the distribution of categories within the benchmark (e.g., people, animals, transportation, etc.) and illustrates the proportion of different question types, providing insights into the diversity and complexity of questions included within the benchmark. The distribution of question types are shown to provide a balance between different types of reasoning abilities.

read the caption

Figure 5: Data characteristics of VideoRefer-Bench.

🔼 Figure 6 presents a qualitative comparison of video descriptions generated by VideoRefer, GPT-40, Elysium, and Artemis on the VideoRefer-BenchD benchmark. The figure directly compares the output of each model for the same video clip, demonstrating VideoRefer’s superior ability to capture fine-grained details, temporal aspects, and relationships within the video. Each model’s description showcases its strengths and weaknesses regarding accuracy, completeness, and overall quality of the video understanding.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visual comparisons between our VideoRefer with general GPT-4o and regional video-level Elysium and Artemis. Here we provide detailed illustrations on VideoRefer-BenchDD{}^{\text{D}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT D end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT.

🔼 This figure displays the cosine similarity between consecutive object-level tokens across temporal sequences within a video. Each row represents a different video segment showing how the similarity between object tokens changes over time. The heatmap shows that for most videos the similarity between consecutive tokens is high, indicating that the object tokens capture the temporal relationships between adjacent frames. The x-axis represents the frame number, and the y-axis represents video samples. The color intensity of each cell indicates the cosine similarity between the respective tokens.

read the caption

Figure 7: Visualizations of similarity among adjacent object-level token pairs across the temporal dimension. Here, we use cosine similarity as the measurement.

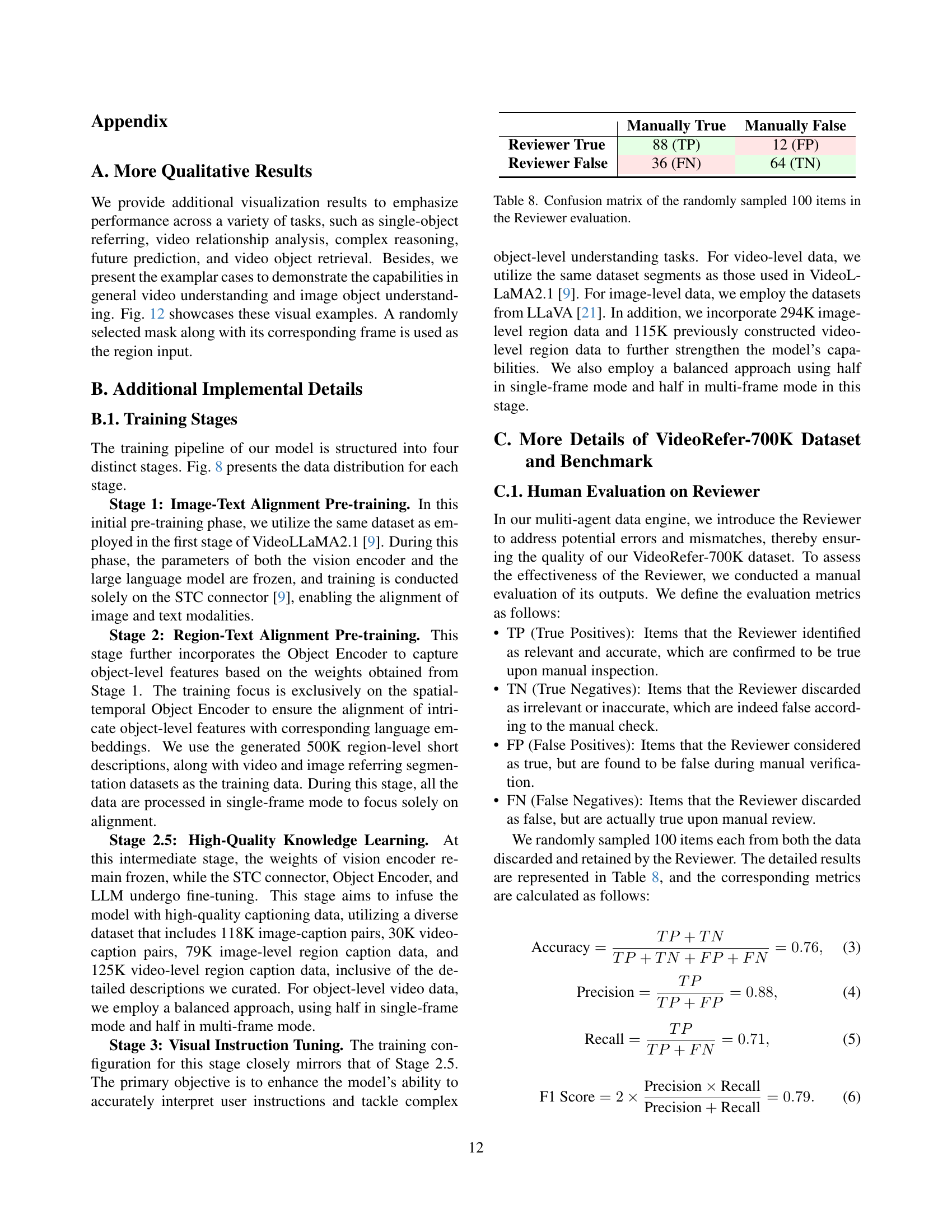

🔼 This figure shows the data distribution for each of the four training stages of the VideoRefer model. Stage 1 focuses on Image-Text Alignment Pre-training using 10M samples. Stage 2 performs Region-Text Alignment Pre-training with 511K samples. Stage 2.5 involves High-Quality Knowledge Learning using 118K image-caption, 30K video-caption, 79K image-level region-caption and 125K video-level region-caption pairs. Finally, Stage 3 conducts Visual Instruction Tuning with 478K samples and additional 115K video-level region-caption pairs. The number of samples in each stage reflects the increasing complexity and specificity of the training data.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visual illustrations of the data distribution for each training stage.

🔼 Figure 9 shows the distribution of data types within the VideoRefer-700K dataset. The dataset is composed of five main categories: short captions, detailed captions, basic questions, reasoning questions, and future predictions. Each bar in the chart represents the number of samples in that category, illustrating the relative proportion of each data type within the overall dataset. This visualization helps understand the dataset’s composition and balance across different task types.

read the caption

Figure 9: Data distributions of our VideoRefer-700K dataset, encompassing five different data types.

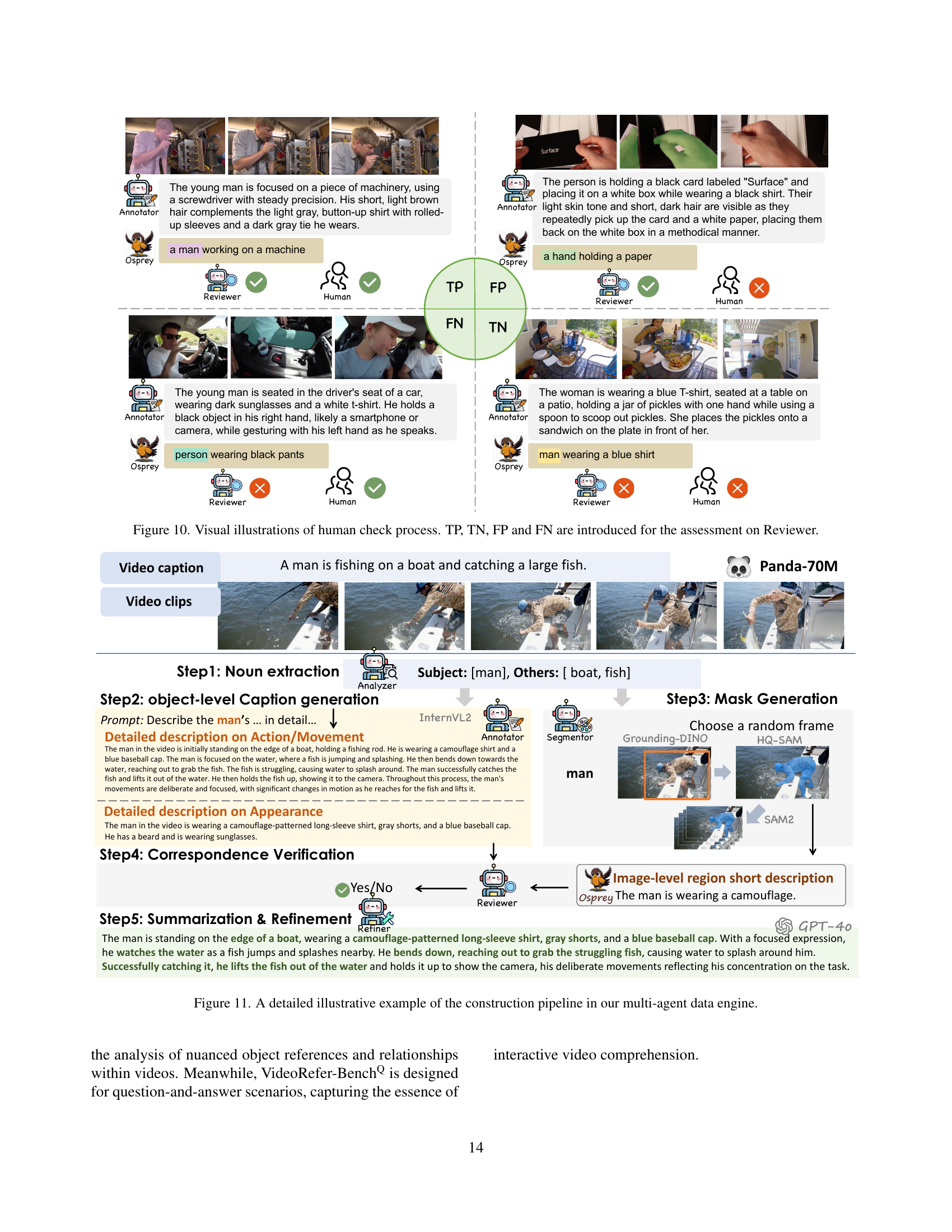

🔼 This figure visually demonstrates the human evaluation process used to assess the performance of the ‘Reviewer’ component within a multi-agent data engine. The Reviewer’s task is to verify the accuracy of object-level annotations generated automatically. The image displays several examples of video clips and their corresponding annotations. Each example is categorized into one of four groups based on the Reviewer’s assessment and the ground truth: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN). True Positives represent correctly identified accurate annotations. True Negatives are correctly identified inaccurate annotations. False Positives are inaccurate annotations incorrectly identified as accurate. False Negatives are accurate annotations incorrectly identified as inaccurate. This process is essential in ensuring the quality and reliability of the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 10: Visual illustrations of human check process. TP, TN, FP and FN are introduced for the assessment on Reviewer.

🔼 This figure illustrates the multi-agent data engine used to create the VideoRefer-700K dataset. The process begins with noun extraction from video captions using an analyzer. Then, an annotator generates detailed descriptions of these objects, focusing on both appearance and motion. A segmentor creates pixel-level masks for each object in a randomly selected frame, which are then propagated to all other frames using SAM 2 [34]. A reviewer verifies the accuracy of the descriptions, discarding inaccurate ones. Finally, a refiner summarizes and refines the captions to ensure coherence and accuracy, resulting in a high-quality dataset with detailed object descriptions and corresponding masks.

read the caption

Figure 11: A detailed illustrative example of the construction pipeline in our multi-agent data engine.

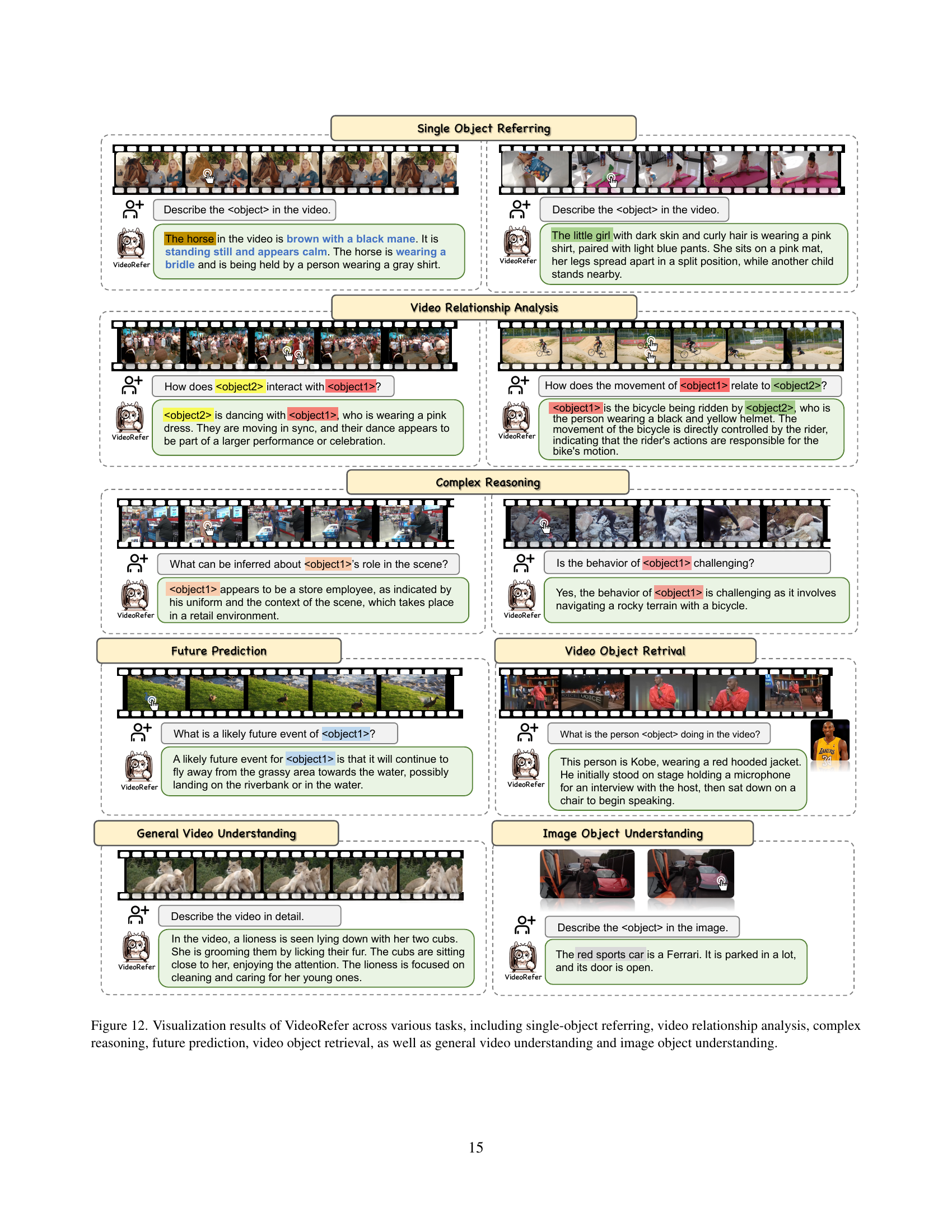

🔼 Figure 12 showcases VideoRefer’s capabilities on various video understanding tasks. Each row presents a different task: single-object referring (describing a specific object), video relationship analysis (explaining the interaction between objects), complex reasoning (inferring information about an object’s role), future prediction (predicting an object’s future action), video object retrieval (identifying an object based on a textual query), and general video understanding (providing a holistic summary of the video). For each task, example video clips and VideoRefer’s corresponding response are displayed, highlighting the model’s ability to understand various levels of video comprehension.

read the caption

Figure 12: Visualization results of VideoRefer across various tasks, including single-object referring, video relationship analysis, complex reasoning, future prediction, video object retrieval, as well as general video understanding and image object understanding.

🔼 Figure 13 shows example data from the VideoRefer-700K dataset. It demonstrates the three types of annotations included: short descriptions (concise summaries of the video’s content), detailed descriptions (more thorough and comprehensive explanations), and question-answer (QA) pairs (questions about the video and their corresponding answers). This variety of annotations helps to ensure that the VideoRefer model can accurately understand and respond to various queries about the video.

read the caption

Figure 13: Visual samples from our VideoRefer-700 dataset, typical including short descriptions, detailed descriptions, and QA pairs.

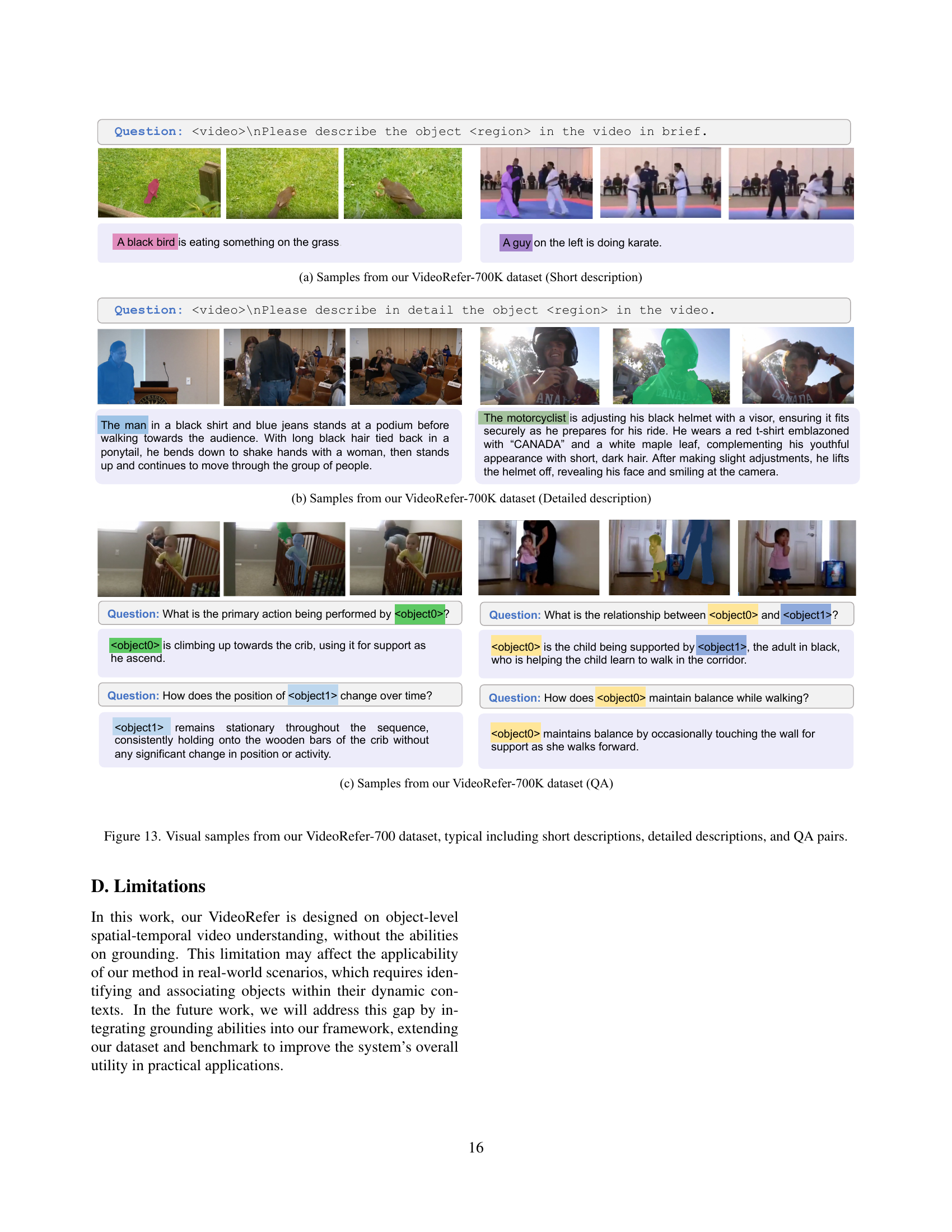

🔼 Figure 14 presents visual examples from the VideoRefer-Bench benchmark, which is designed to comprehensively evaluate the capabilities of Video LLMs in video understanding. The benchmark consists of two sub-benchmarks: VideoRefer-BenchD (for Description Generation) and VideoRefer-BenchQ (for Multiple-choice Question Answering). The figure showcases diverse examples illustrating the various task types within each sub-benchmark, demonstrating the complexity and variety of questions that VideoRefer-Bench assesses. This includes questions about basic object identification and descriptions, sequential actions, relationships between objects, reasoning, and future predictions.

read the caption

Figure 14: Visual examples of our VideoRefer-Bench, including VideoRefer-BenchDD{}^{\text{D}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT D end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT and VideoRefer-BenchQQ{}^{\text{Q}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT Q end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT.

More on tables

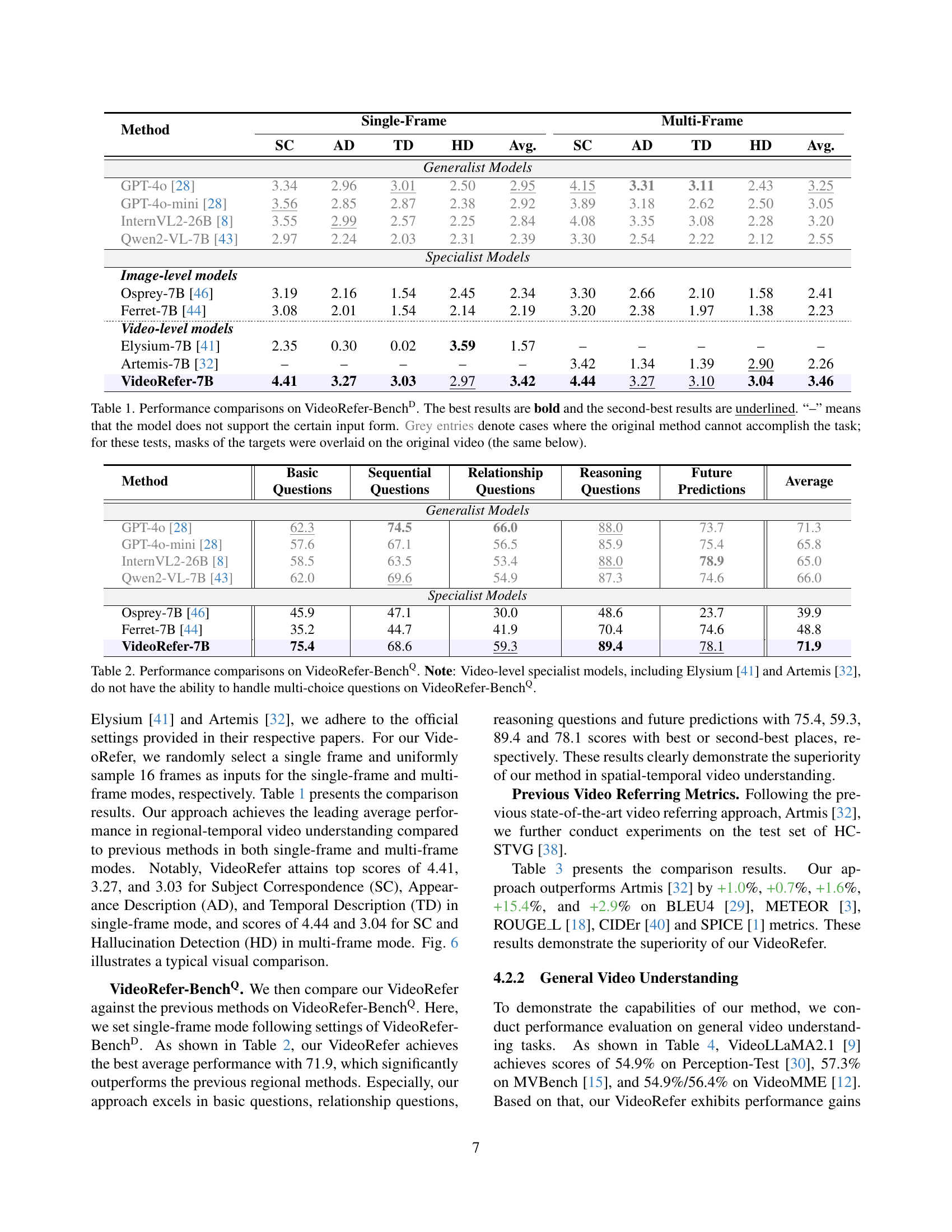

| Method | Basic Questions | Sequential Questions | Relationship Questions | Reasoning Questions | Future Predictions | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalist Models | ||||||

| GPT-4o [28] | 62.3 | 74.5 | 66.0 | 88.0 | 73.7 | 71.3 |

| GPT-4o-mini [28] | 57.6 | 67.1 | 56.5 | 85.9 | 75.4 | 65.8 |

| InternVL2-26B [8] | 58.5 | 63.5 | 53.4 | 88.0 | 78.9 | 65.0 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B [43] | 62.0 | 69.6 | 54.9 | 87.3 | 74.6 | 66.0 |

| Specialist Models | ||||||

| Osprey-7B [46] | 45.9 | 47.1 | 30.0 | 48.6 | 23.7 | 39.9 |

| Ferret-7B [44] | 35.2 | 44.7 | 41.9 | 70.4 | 74.6 | 48.8 |

| VideoRefer-7B | 75.4 | 68.6 | 59.3 | 89.4 | 78.1 | 71.9 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different models’ performance on the VideoRefer-BenchQ benchmark, specifically focusing on the accuracy of answering multiple-choice questions related to videos. It shows the average performance across five question types: Basic Questions, Sequential Questions, Relationship Questions, Reasoning Questions, and Future Predictions. Note that certain video-specialized models (Elysium and Artemis) were not included in the comparison because they lack the capability to handle multiple-choice questions.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance comparisons on VideoRefer-BenchQQ{}^{\text{Q}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT Q end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT. Note: Video-level specialist models, including Elysium [41] and Artemis [32], do not have the ability to handle multi-choice questions on VideoRefer-BenchQQ{}^{\text{Q}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT Q end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT.

| Method | BLEU@4 | METEOR | ROUGE_L | CIDER | SPICE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merlin [45] | 3.3 | 11.3 | 26.0 | 10.5 | 20.1 |

| Artemis [32] | 15.5 | 18.0 | 40.8 | 53.2 | 25.4 |

| VideoRefer | 16.5 | 18.7 | 42.4 | 68.6 | 28.3 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different models on video-based referring tasks, specifically using the HC-STVG [38] test set. The metrics used to evaluate the models’ performance are BLEU@4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE, all commonly used in evaluating the quality of generated descriptions for videos. The table allows for a direct comparison of how well different models generate descriptions that align with the visual content of the videos, highlighting the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model on various aspects of video captioning.

read the caption

Table 3: Exprimental results on video-based referring metrics on the HC-STVG [38] test set.

| Method | Perception-Test | MVBench | VideoMME |

|---|---|---|---|

| VideoLLaMA2 [9] | 51.4 | 54.6 | 47.9/50.3 |

| VideoLLaMA2.1 [9] | 54.9 | 57.3 | 54.9/56.4 |

| Artemis [32] | 47.1 | 34.1 | 28.8/35.3 |

| VideoRefer | 56.3 | 59.6 | 55.9/57.6 |

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different models on general video understanding tasks. It shows the accuracy scores achieved by various models on three established benchmarks: Perception-Test, MVBench, and VideoMME. The results highlight the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model in terms of its overall video comprehension capabilities.

read the caption

Table 4: Exprimental results on general video understanding tasks.

| Mode | VideoRefer-BenchD | VideoRefer-BenchQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode | TD | HD | Avg. | SQ | RQ | Avg. | |

| Single-frame | 3.03 | 2.97 | 3.42 | 68.3 | 59.1 | 71.9 | |

| Multi-frame | 3.10 | 3.04 | 3.46 | 70.6 | 60.5 | 72.1 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the model’s performance using single-frame and multi-frame modes during inference. The metrics evaluated include average performance across all questions, along with a breakdown of scores for Sequential Questions (SQ) and Relationship Questions (RQ). This allows for an analysis of how the model’s ability to understand temporal relationships and object interactions changes depending on the input type (single frame vs. multiple frames).

read the caption

Table 5: Results using different modes during the inference. Here, SQ and RQ are Sequential Questions and Relationship Questions.

| Method | BenchD | BenchQ | MVBench |

|---|---|---|---|

| w/o Regional data | – | – | 57.9 |

| + Short description | 2.43 | 68.3 | 58.0 |

| + QA | 2.45 | 71.7 | 58.4 |

| + Detailed description | 3.42 | 71.9 | 59.6 |

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results, showing how different types of data in the VideoRefer-700K dataset affect the performance of the VideoRefer model on the VideoRefer-Bench benchmark. Specifically, it compares the model’s performance when trained only on short captions, short captions plus question-answer pairs (QA), and short captions plus QA plus detailed descriptions. The results demonstrate the incremental improvements in performance as more comprehensive data is included in the training process.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation results on various data types in VideoRefer-700K dataset. Bench denotes VideoRefer-Bench for simplicity.

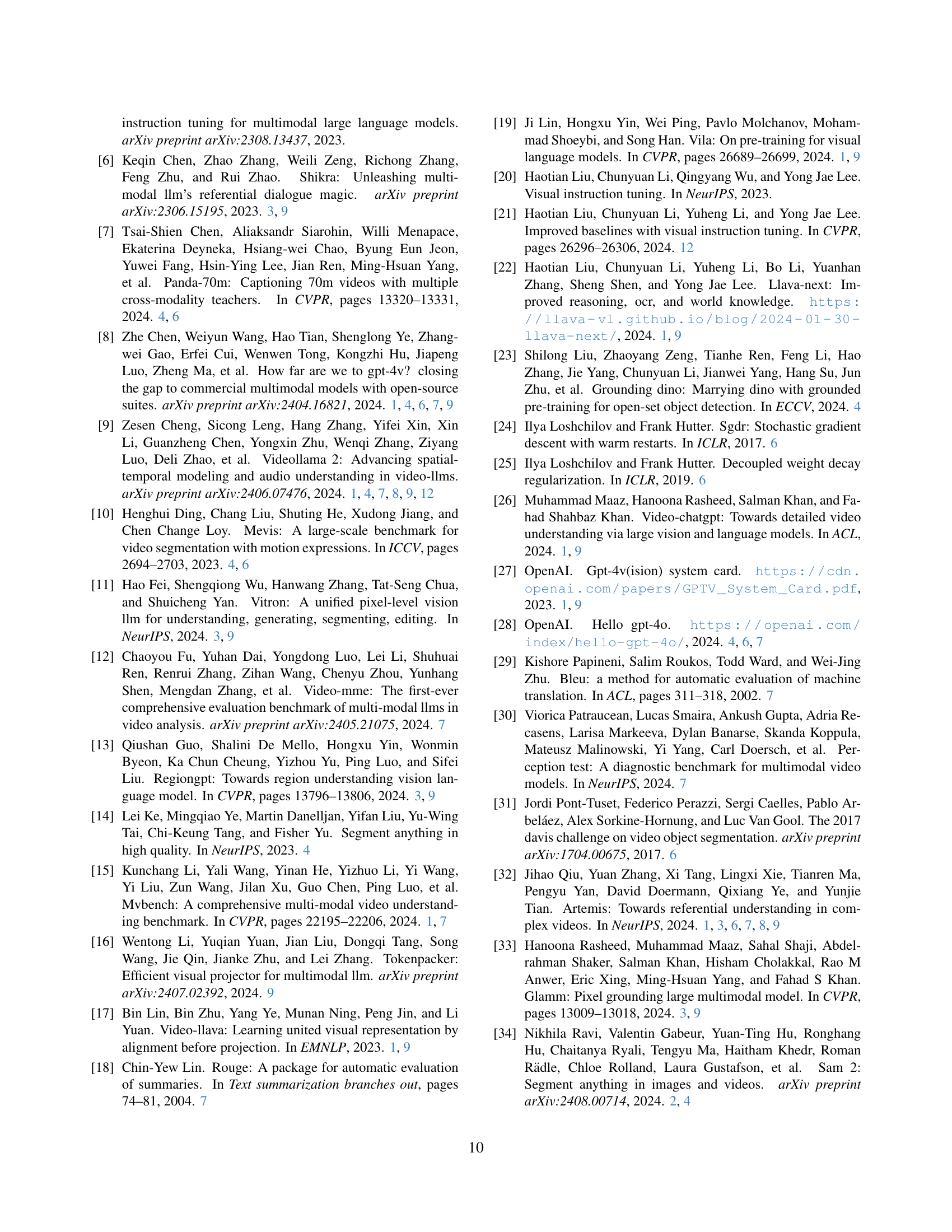

| Union | VideoRefer-BenchD | VideoRefer-BenchQ |

|---|---|---|

| u | ||

| TD | HD | SQ |

| 32 | 3.17 | 3.01 |

| 16 | 3.20 | 2.99 |

| 8 | 3.18 | 3.02 |

| 4 | 3.10 | 3.04 |

| 1 | 3.08 | 2.98 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of temporal and sequential performance metrics achieved by the VideoRefer model using different numbers of unions (u) in the Temporal Token Merge (TTM) module, under a multi-frame setting. The results demonstrate how varying the number of unions affects the model’s ability to capture temporal relationships and generate accurate descriptions. Specifically, it shows the scores for Temporal Description (TD), Hallucination Detection (HD), Sequential Questions (SQ), and Relationship Questions (RQ) tasks for several values of u.

read the caption

Table 7: Temporal and sequential performance comparisons for various union u𝑢uitalic_u in the TTM module under multi-frame mode.

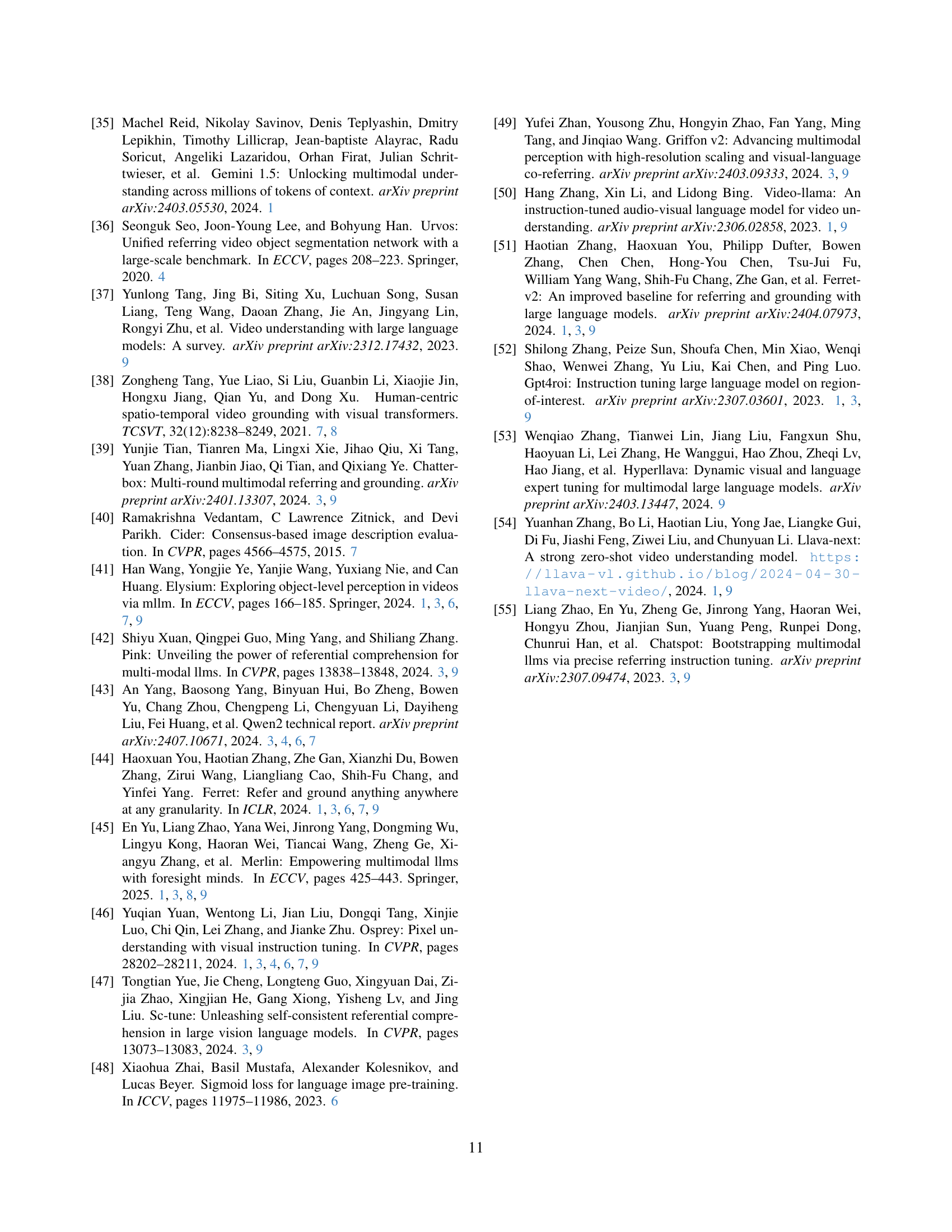

| Manually True | Manually False | |

|---|---|---|

| Reviewer True | 88 (TP) | 12 (FP) |

| Reviewer False | 36 (FN) | 64 (TN) |

🔼 This table presents the results of a manual evaluation assessing the performance of the Reviewer component within a multi-agent data engine. The Reviewer’s task is to verify the accuracy and relevance of object-level captions and masks generated by other components in the pipeline. The confusion matrix shows the counts of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) based on a random sample of 100 items (50 where the Reviewer flagged the data as correct and 50 where the Reviewer flagged the data as incorrect). This allows for the calculation of precision, recall, F1-score and accuracy metrics to evaluate the Reviewer’s effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 8: Confusion matrix of the randomly sampled 100 items in the Reviewer evaluation.

Full paper#