TL;DR#

Current benchmarks for evaluating large language models’ (LLMs) coding skills are inadequate, lacking comprehensive test suites, private test cases, and proper judge support, leading to inaccurate results and misaligned evaluation environments. This research introduces CODEELO, a new benchmark designed to address these issues. It leverages the CodeForces competitive coding platform, ensuring accurate and standardized evaluations.

CODEELO uses a unique judging system by directly submitting code to the CodeForces platform, guaranteeing reliable results. The benchmark categorizes problems by difficulty and algorithm type, offering detailed performance analysis. The results reveal that while some LLMs perform exceptionally well, others struggle even with basic tasks, highlighting areas for improvement. CODEELO also introduces a human-comparable Elo rating system, enabling more precise comparisons between LLMs and human coders.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

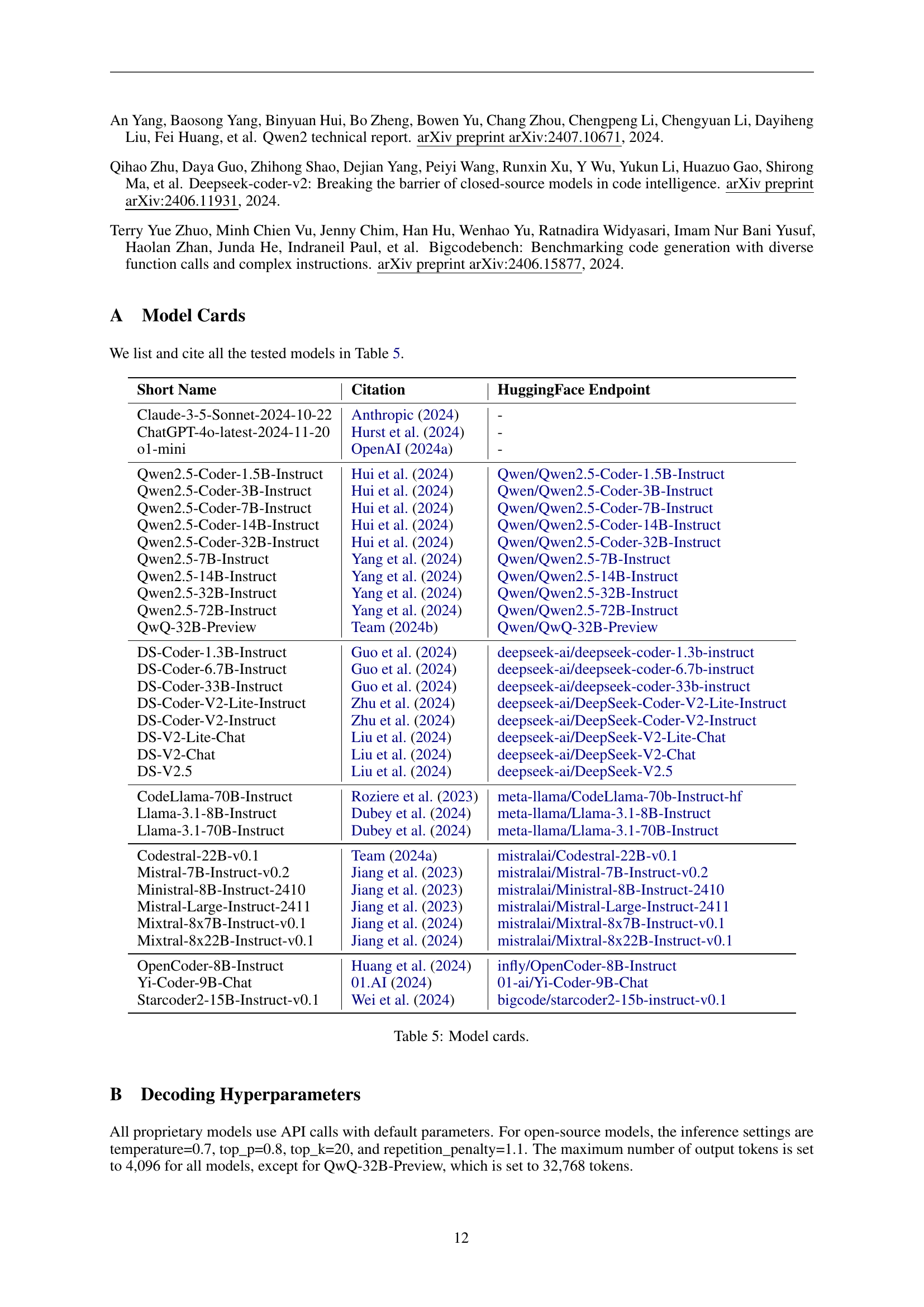

This paper is important because it introduces CODEELO, a novel benchmark for evaluating large language models’ code generation capabilities. It addresses limitations of existing benchmarks by using a standardized competition-level coding platform, enabling more accurate and human-comparable evaluations. This provides crucial insights into LLM strengths and weaknesses in code generation, paving the way for improved model development and fairer comparisons.

Visual Insights#

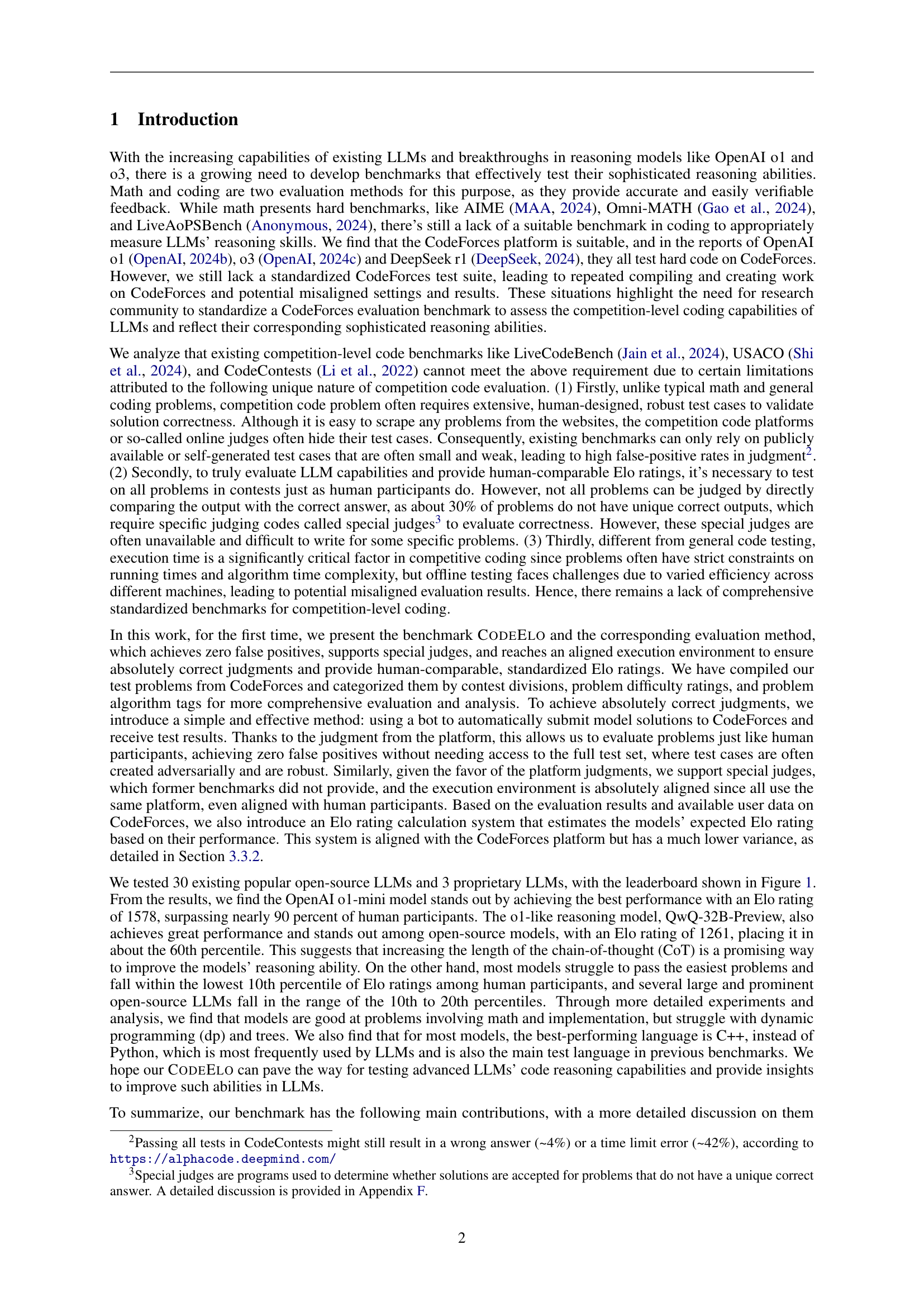

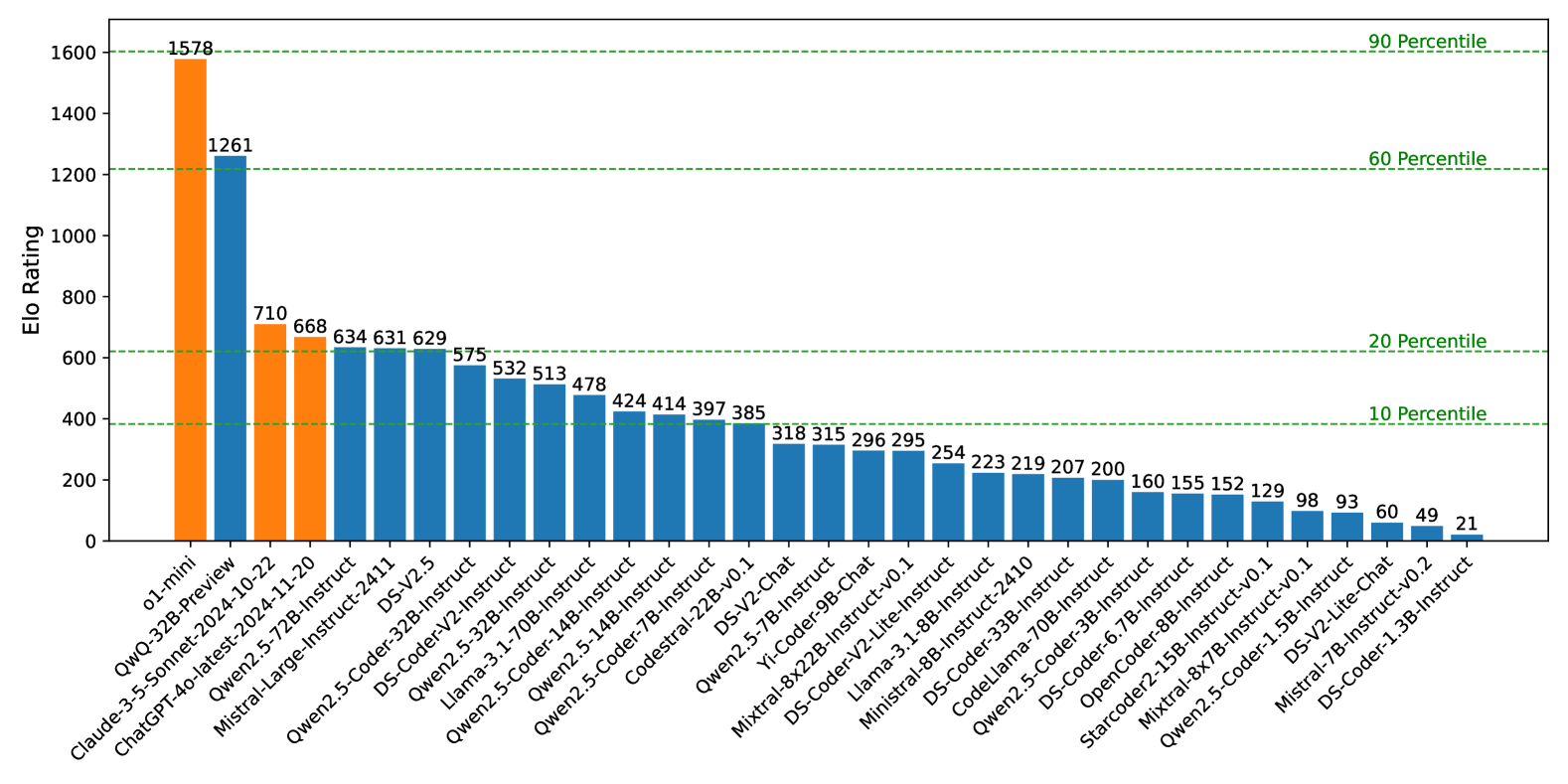

🔼 This figure shows the Elo ratings of 30 different large language models (LLMs) on the CODEELO benchmark. The Elo rating system is used to rank the models based on their performance on a set of competitive programming problems. Higher Elo ratings indicate better performance. The figure visually represents the ranking of the models, with the highest-performing models at the top.

read the caption

Figure 1: The ELO rating leaderboard.

| Problem | Difficulty | Updates | Zero False | Positive? | Special | Judge? | Aligned | Execution | Environment? | Standardized | Elo Rating? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APPS | ★★ | No updates | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CodeContests | ★★★ | No updates | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| TACO | ★★ | No updates | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| xCodeEval | ★ | No updates | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| USACO | ★★ | Offline | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| LiveCodeBench | ★ | Online | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CodeForces | ★★★ | Online | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

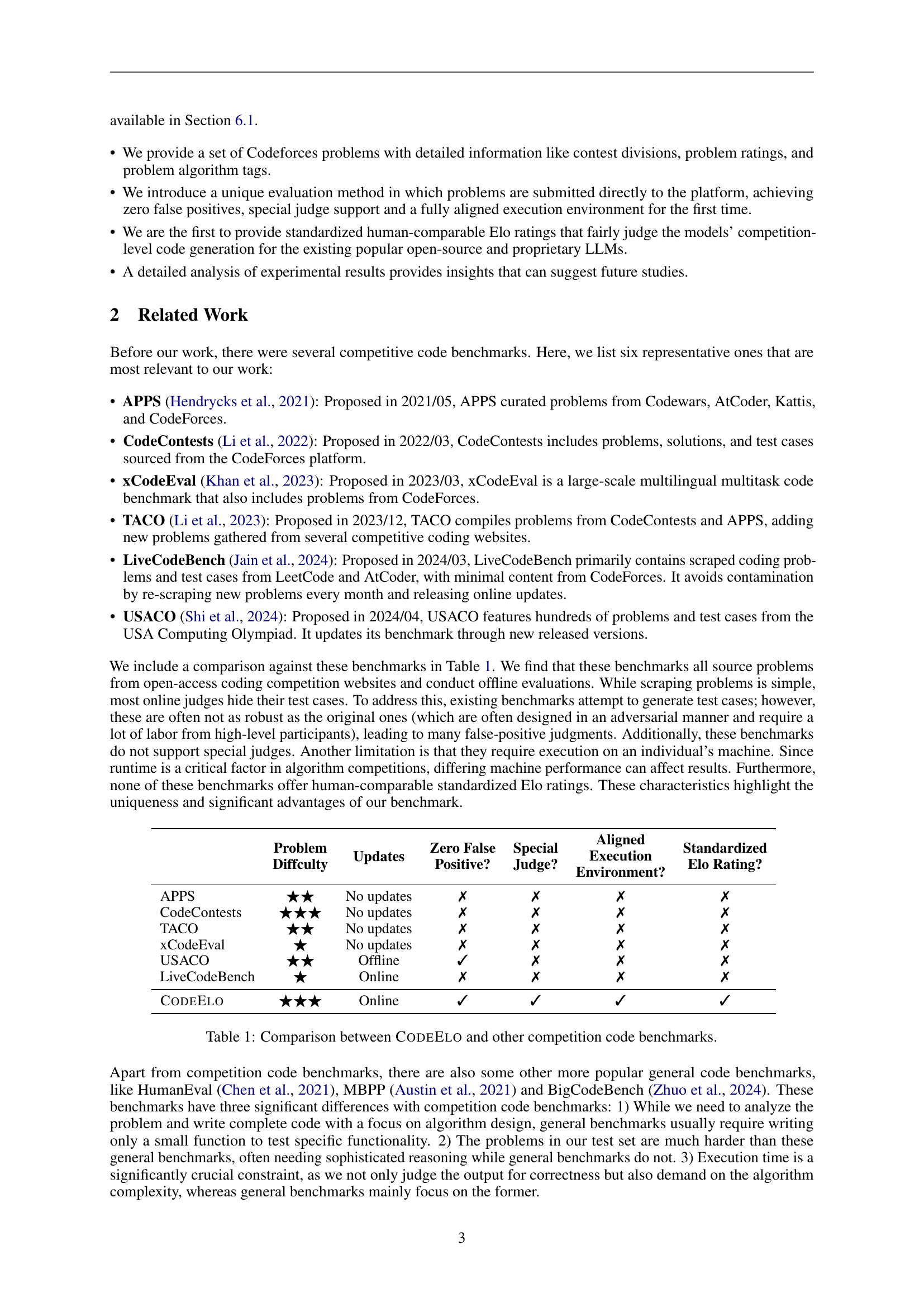

🔼 This table compares CODEELO with other existing competitive programming benchmarks across several key features. These features include whether the benchmark provides updates, ensures zero false positives in its evaluation, supports special judges (for problems with multiple valid solutions), offers an aligned execution environment to prevent inconsistencies, and whether it uses a standardized Elo rating system to rank and compare model performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison between CodeForces and other competition code benchmarks.

In-depth insights#

CodeELO: A New Benchmark#

CodeELO presents a novel benchmark designed to rigorously evaluate the code generation capabilities of large language models (LLMs). Unlike previous benchmarks, CodeELO leverages the CodeForces platform for evaluation, ensuring a standardized, competition-level testing environment. This approach eliminates the limitations of existing methods such as the unavailability of private test cases and misaligned execution environments. CODEELO’s unique judging method involves direct submission of LLM-generated code to CodeForces, achieving zero false positives and supporting special judges. Furthermore, CODEELO introduces a human-comparable Elo rating system, allowing for a more nuanced comparison of LLM performance against human participants. This benchmark addresses several critical shortcomings of prior work, providing a more comprehensive and realistic evaluation of LLM coding proficiency. The detailed analysis provided by CODEELO, including performance across various algorithms and programming languages, offers valuable insights for future research and development in LLM code generation.

Elo Rating System#

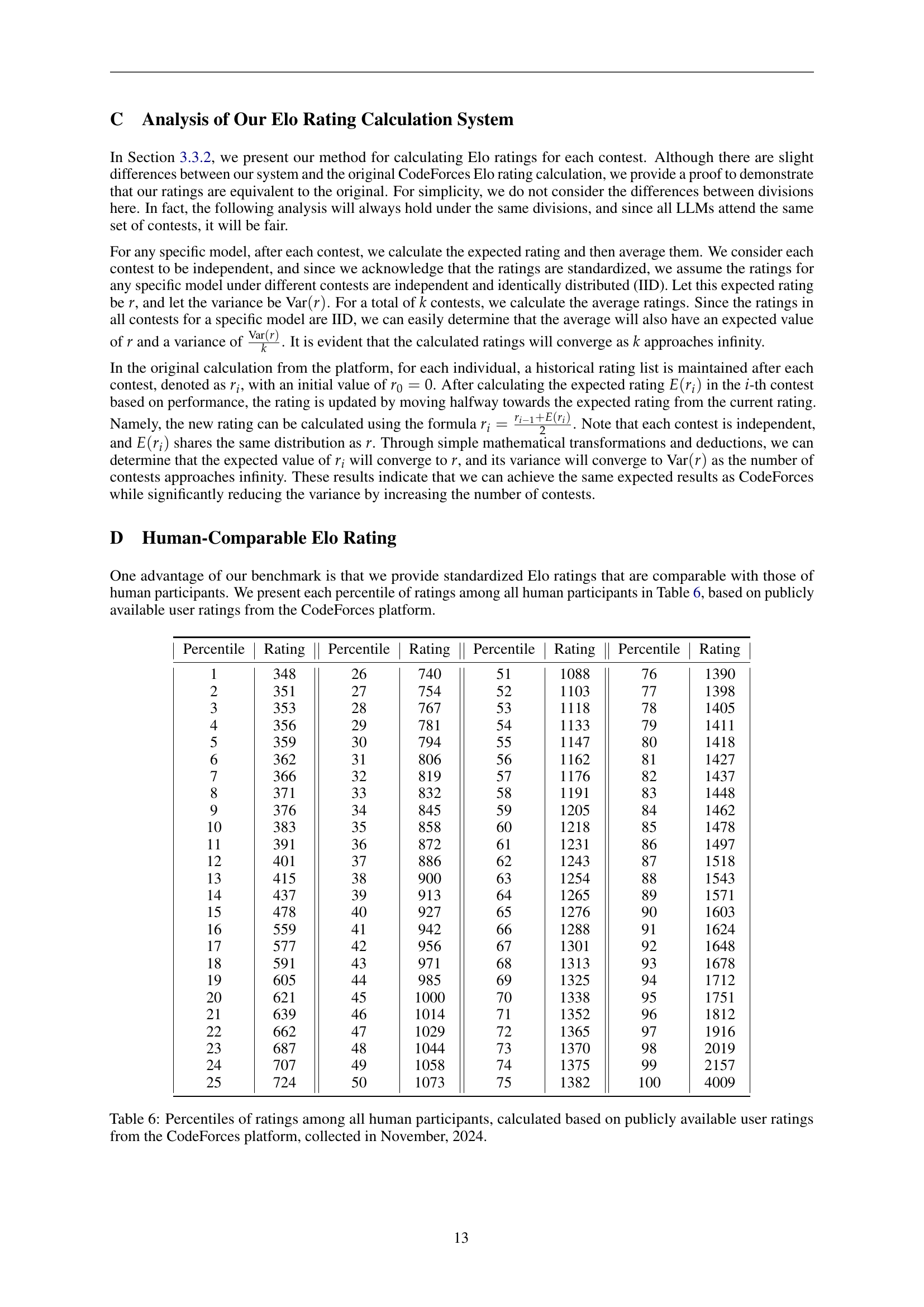

The paper introduces a novel Elo rating system for evaluating large language models’ (LLMs) code generation capabilities. Instead of relying on simplistic pass/fail metrics, the Elo system dynamically adjusts LLM rankings based on their performance against a pool of Codeforces problems. This approach mirrors human competitive coding rankings, providing a more nuanced and informative evaluation. A key advantage is the system’s robustness; it handles diverse problem types and the use of ‘special judges’ – crucial for problems with multiple valid solutions – thus ensuring accurate assessment. Furthermore, the method aligns closely with the Codeforces platform, leveraging its automated judging system to avoid biases and enhance reliability. The detailed explanation of the Elo calculation process, its comparison to traditional Codeforces methods, and the discussion on its advantages (lower variance, comprehensive assessment) highlight the system’s sophistication and suitability for benchmarking LLMs in a competitive context. This innovative approach significantly improves the accuracy and interpretability of LLM evaluation in code generation.

LLM Code Generation#

The field of LLM code generation is rapidly evolving, driven by the need for efficient and reliable automated code production. Current benchmarks often fall short, lacking comprehensive test cases, special judge support, and consistent execution environments. This paper introduces CODEELO, a novel benchmark designed to address these shortcomings by leveraging the CodeForces platform. CODEELO’s strength lies in its direct submission of code to CodeForces, ensuring accurate and unbiased evaluation. This methodology addresses the limitations of previous benchmarks by providing a standardized environment. CODEELO’s Elo rating system is another key feature, enabling a fair comparison between LLMs and human programmers, with the added benefit of lower variance than standard methods. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of CODEELO in evaluating LLMs’ competition-level coding abilities, revealing surprising performance differences between models. Further research is required to better understand the relationship between model size, architecture, and overall performance, but the introduction of a robust benchmark like CODEELO is a major step toward advancing the field of LLM code generation.

Algorithm Analysis#

An algorithm analysis section in a research paper on large language model (LLM) code generation would likely involve a multifaceted examination of the models’ performance across various algorithms. This would go beyond simple pass/fail metrics. The analysis would likely investigate the models’ success rate on problems categorized by specific algorithm types (e.g., dynamic programming, graph algorithms, sorting algorithms). The choice of algorithms to analyze would reflect common algorithmic challenges found in competitive programming competitions. Key metrics would likely include pass rates, execution time, and perhaps even an analysis of the code’s quality (e.g., code style, efficiency, correctness). The findings would likely reveal strengths and weaknesses in the models’ understanding and application of different algorithms, possibly revealing biases or limitations in their training data. The analysis might also compare the models’ performance across different programming languages (e.g., C++ versus Python), showing how language choice impacts model performance on certain algorithmic tasks. Such insights would be crucial for understanding the models’ capabilities and limitations in code generation and provide actionable feedback for future model improvement and development. The comparative analysis across both open-source and proprietary LLMs is critical for evaluating progress in the field.

Benchmark Limitations#

A robust benchmark for evaluating large language model (LLM) code generation capabilities needs to consider several limitations. First, the reliance on a single platform, like CodeForces, introduces platform-specific biases and might not fully represent the diverse challenges faced in real-world coding scenarios. Second, limiting the number of submissions per problem could underestimate the true potential of some models that might succeed with additional attempts. Third, the dependence on automatic submission to CodeForces for evaluating accuracy relies on the platform’s evaluation which has limited transparency. Therefore, potential discrepancies between the platform’s judgment and other evaluation methods need to be considered. This might underestimate the actual capabilities of certain LLMs. Finally, while the benchmark uses human-comparable Elo ratings, ensuring its comprehensive coverage across diverse coding styles and problem types is crucial for fair comparison. The benchmark should aim for broader coverage and consider more diverse evaluation metrics. Addressing these limitations will improve the overall robustness and generalizability of the LLM code generation benchmark.

More visual insights#

More on figures

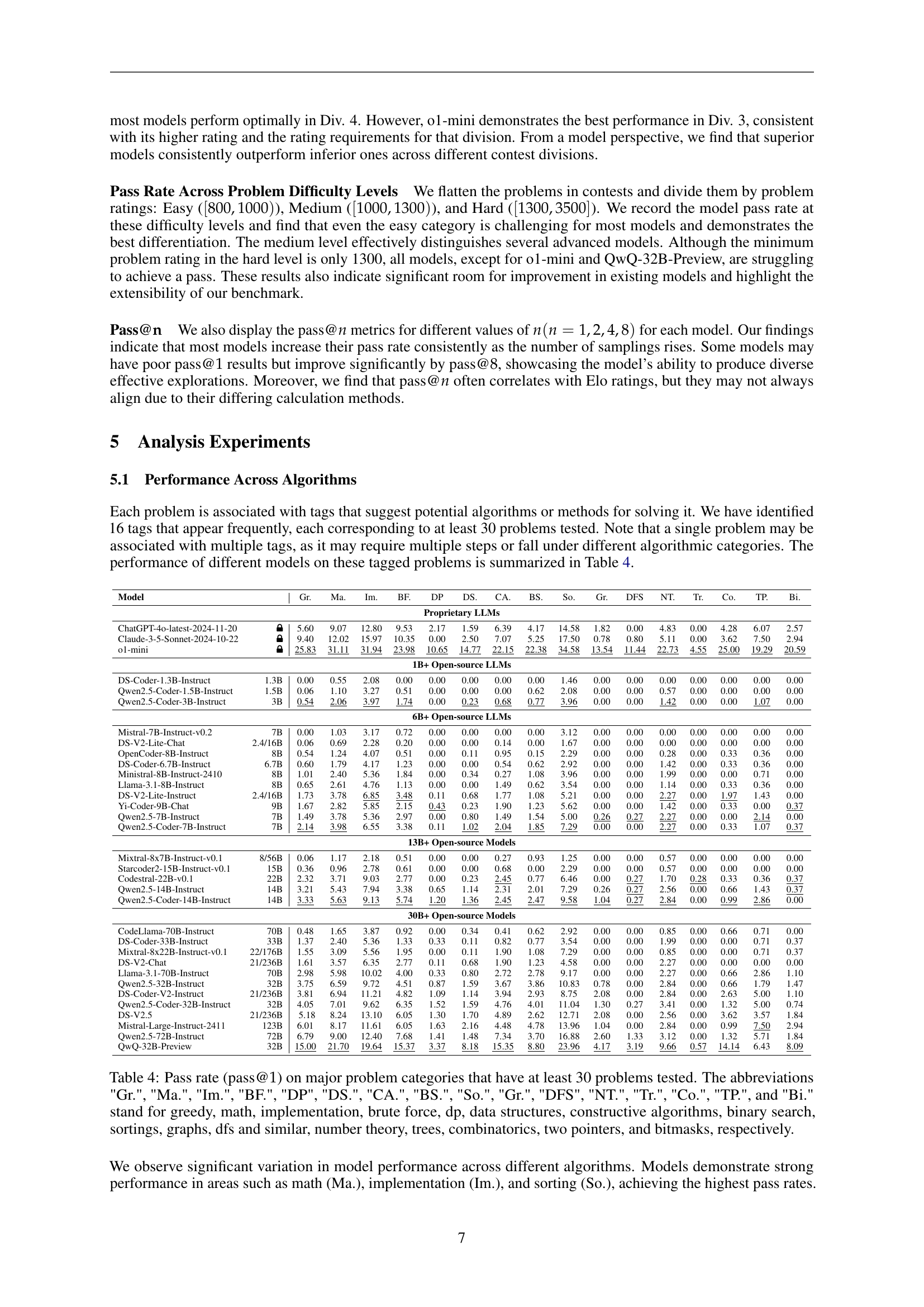

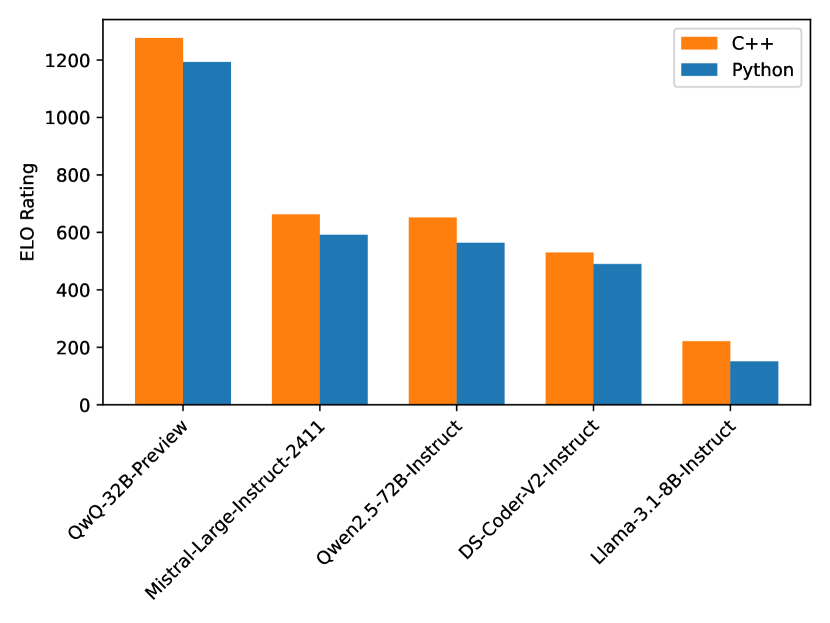

🔼 This figure compares the Elo ratings achieved by several large language models (LLMs) when using C++ versus Python as the programming language for solving competitive coding problems. It highlights the significant performance difference observed between the two languages, showing that models generally perform better when using C++. This difference is attributed to the constraints on algorithm running time often imposed in competitive coding, where C++’s efficiency provides an advantage.

read the caption

Figure 2: The Elo ratings using C++ and Python as programming languages.

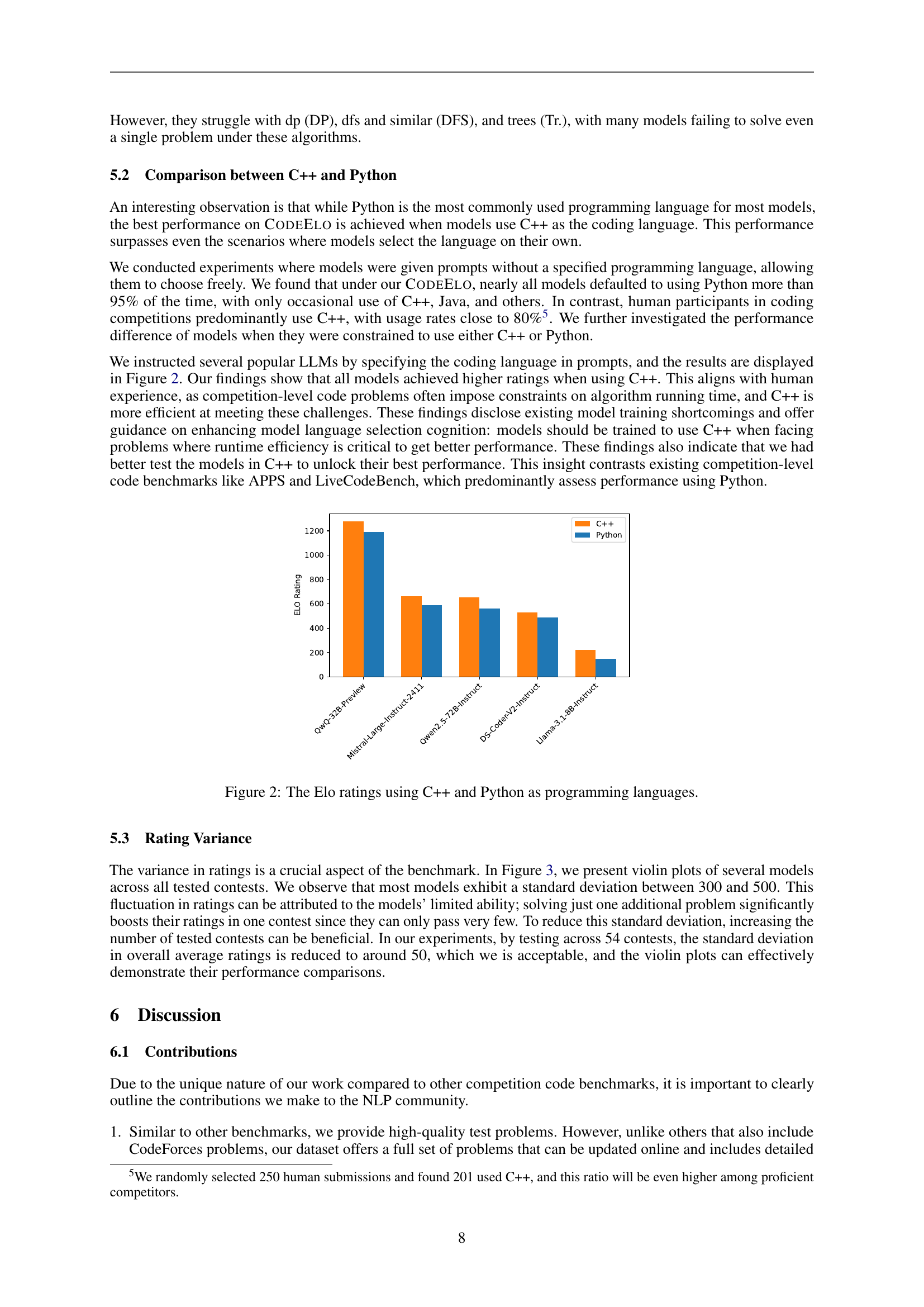

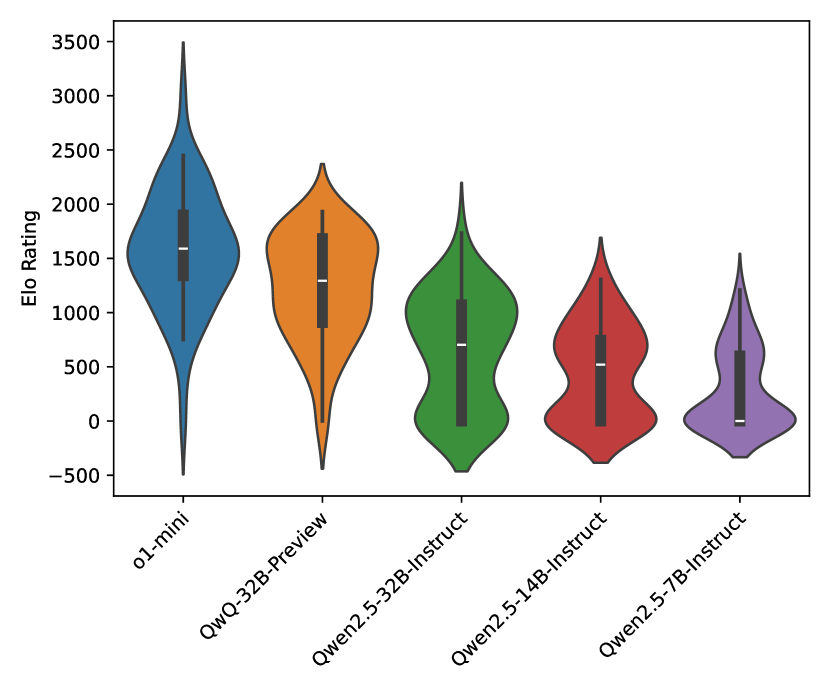

🔼 This violin plot visualizes the distribution of Elo ratings achieved by various large language models (LLMs) across multiple CodeForces contests. Each violin represents a different LLM, showing the spread and central tendency of its Elo ratings. The wider parts of the violins indicate higher data density at that Elo rating range. The plot helps to compare the consistency and overall performance of different LLMs in competitive programming.

read the caption

Figure 3: Violin plots of ratings across tested contests.

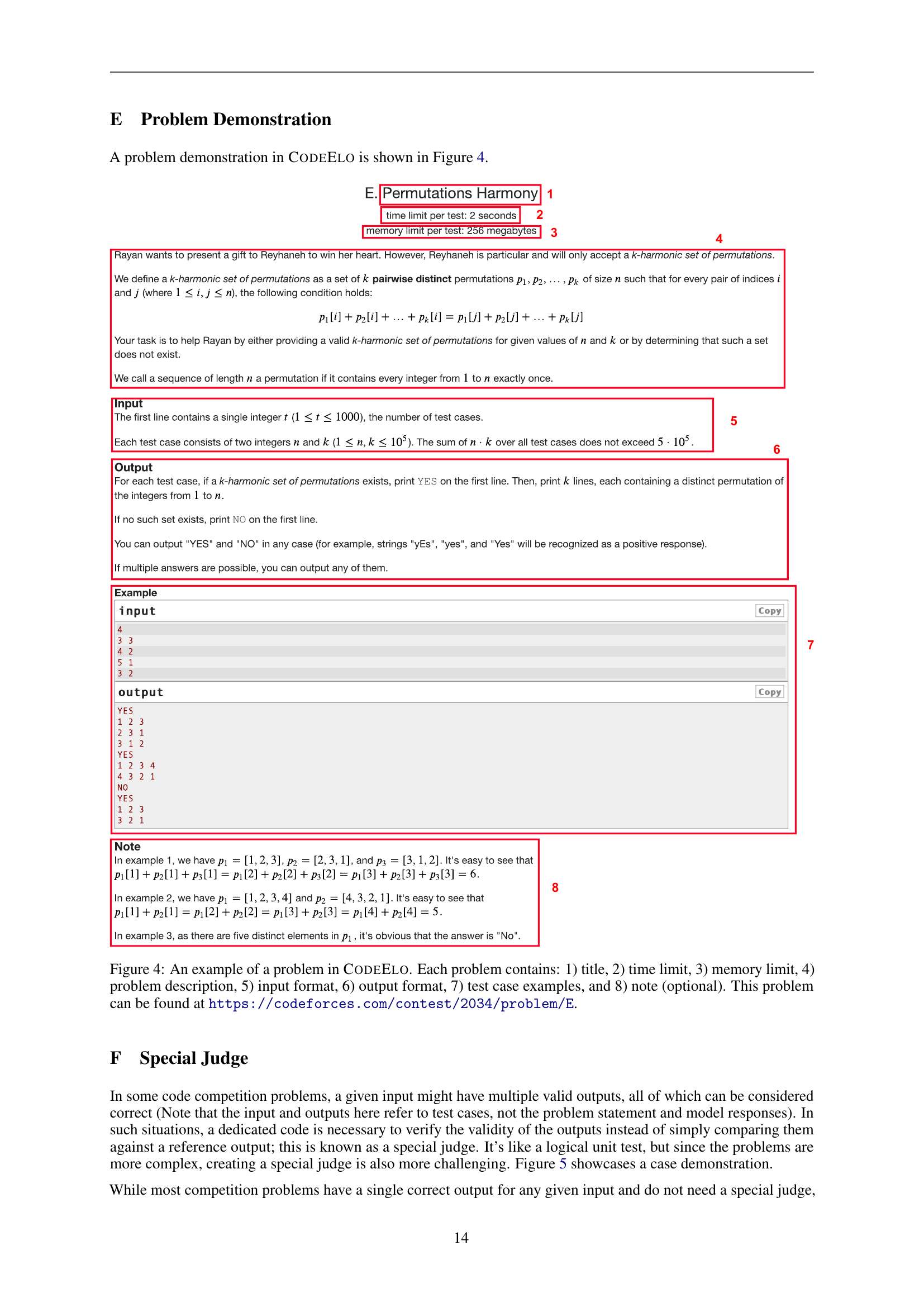

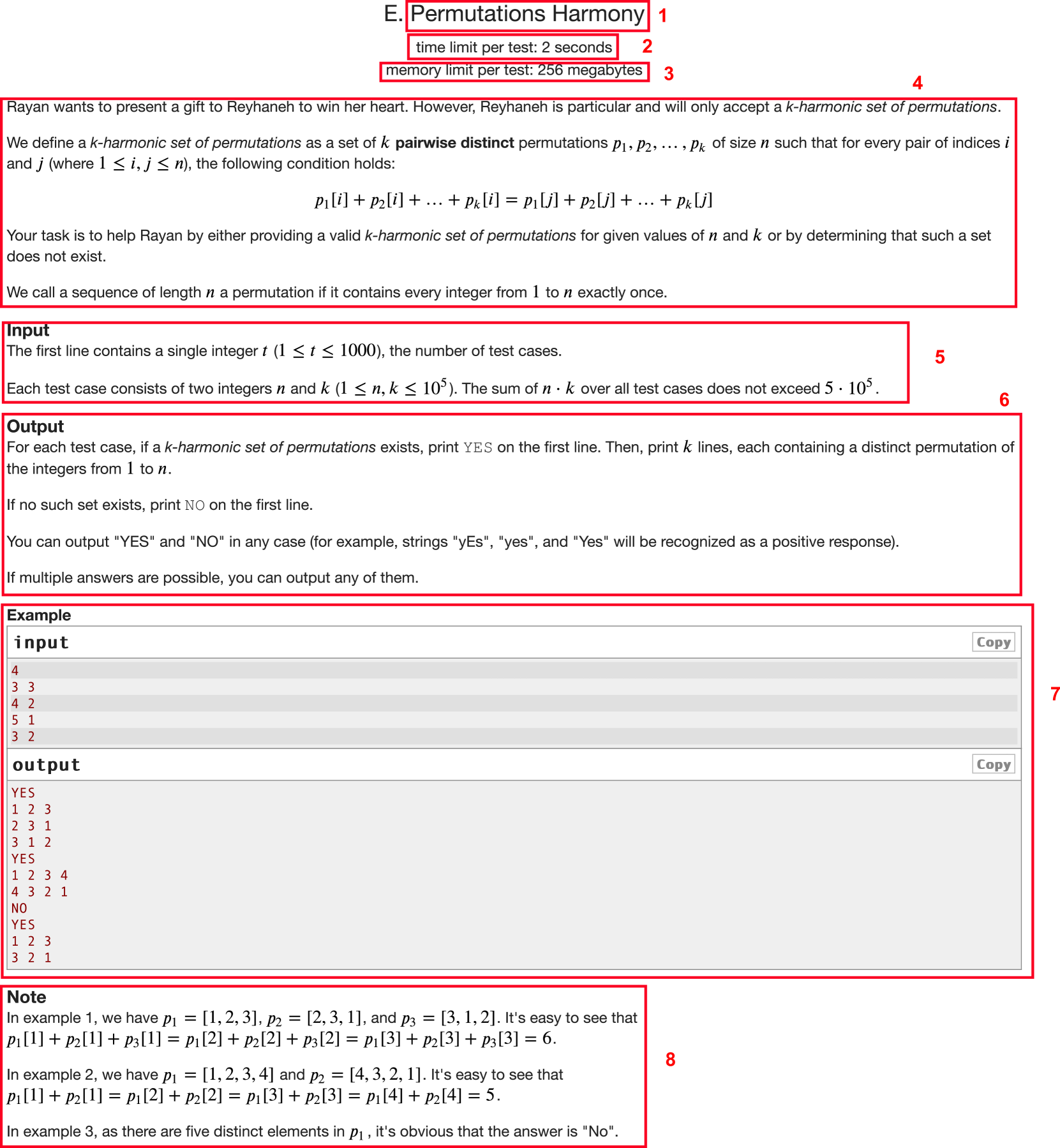

🔼 Figure 4 presents a detailed breakdown of a typical problem from the CodeForces platform, which serves as the foundation for the CODEELO benchmark. The image showcases the various components of a CodeForces problem, including the problem’s title, constraints (time and memory limits), a comprehensive description of the problem’s task and requirements, specifications for input and output formats, sample test cases illustrating input and expected output, and an optional notes section that provides additional clarification or constraints. This example problem, accessible via the provided CodeForces link, highlights the structure and level of detail inherent in the problems used to evaluate the LLMs in the benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 4: An example of a problem in CodeForces. Each problem contains: 1) title, 2) time limit, 3) memory limit, 4) problem description, 5) input format, 6) output format, 7) test case examples, and 8) note (optional). This problem can be found at https://codeforces.com/contest/2034/problem/E.

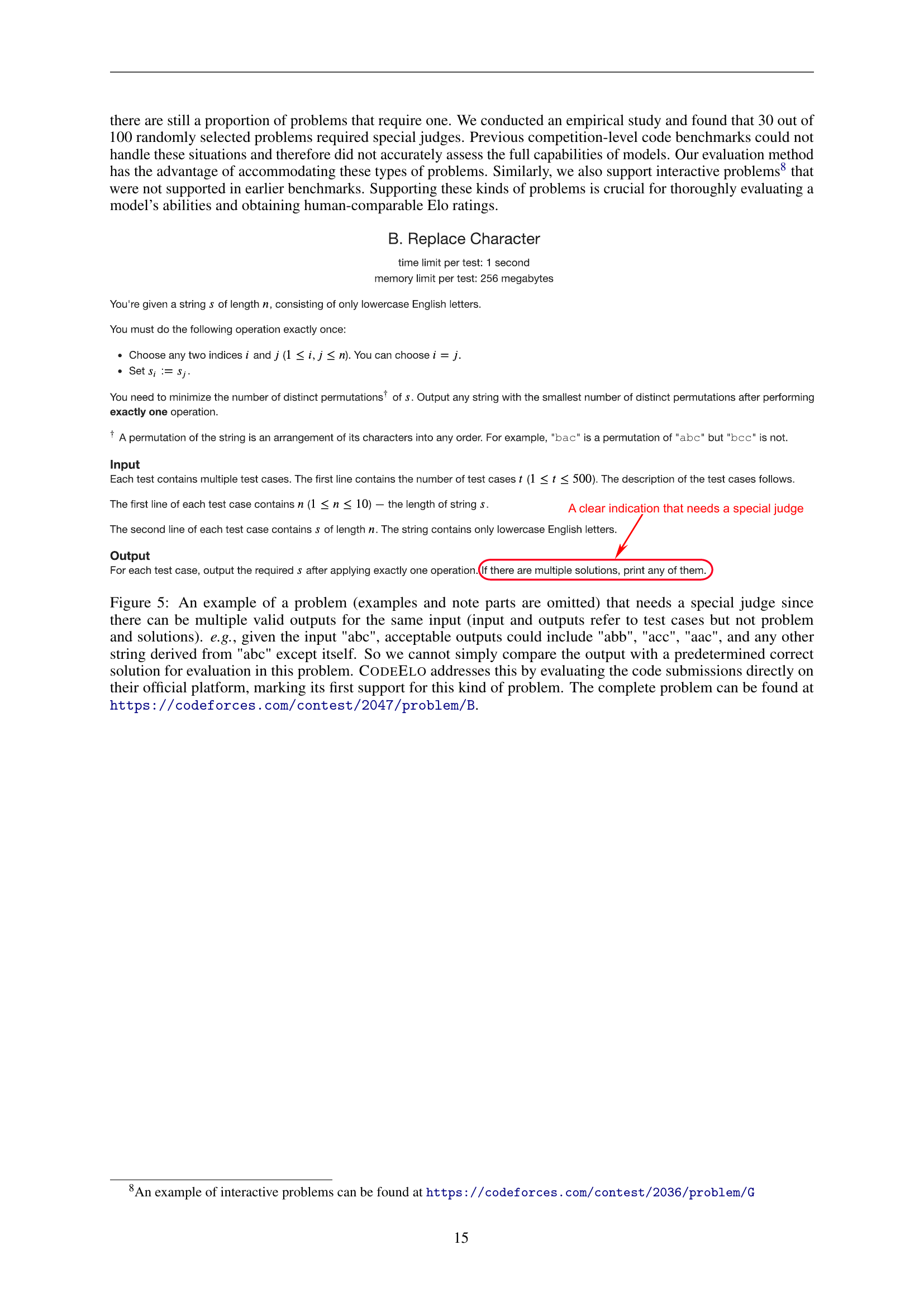

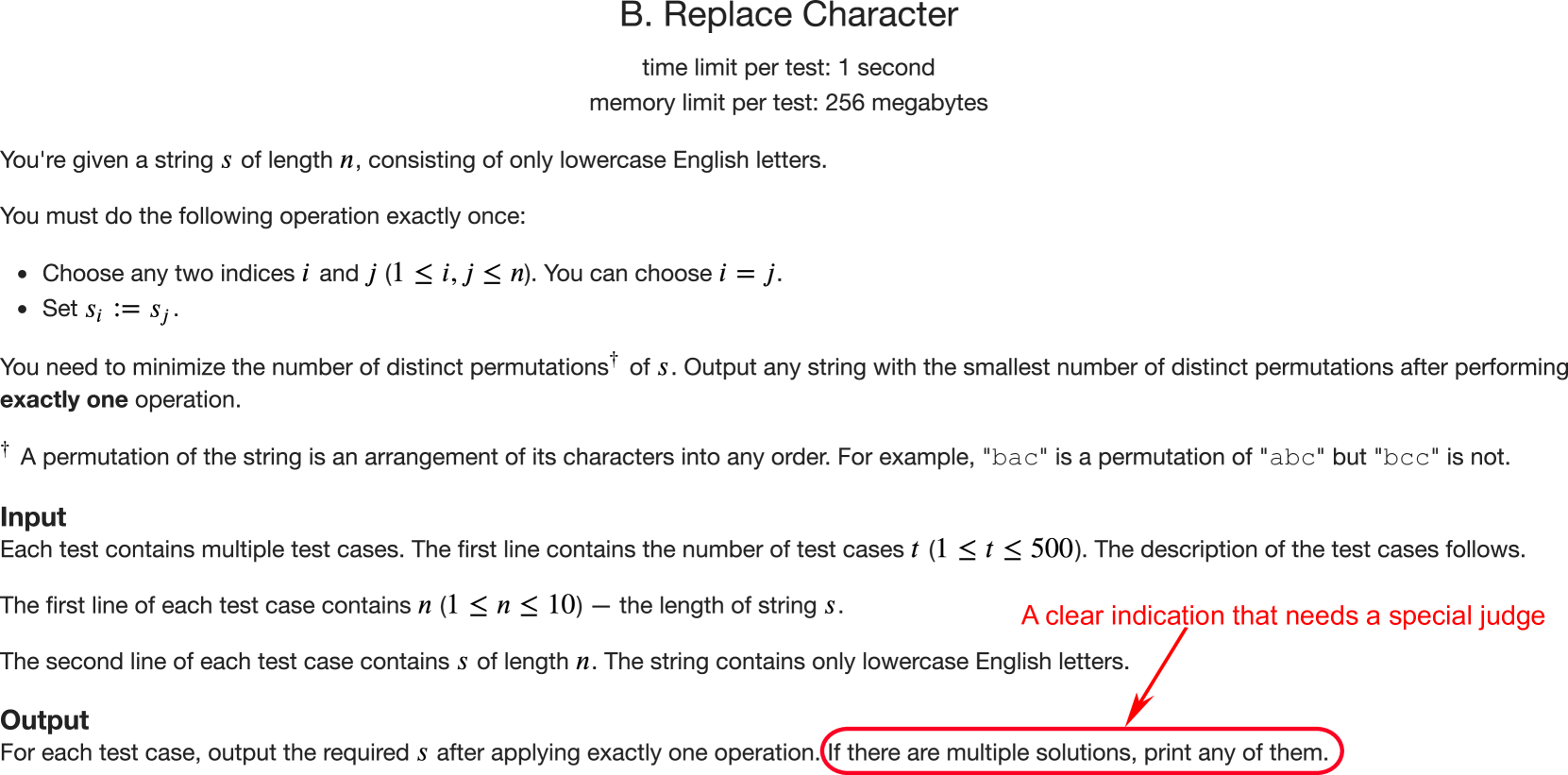

🔼 Figure 5 demonstrates a Codeforces problem requiring a special judge. A special judge is necessary because multiple correct outputs exist for a single input. The example given shows that for the input ‘abc’, outputs like ‘abb’, ‘aac’, and others derived from ‘abc’ (excluding ‘abc’ itself) are all valid. Direct output comparison against a pre-defined solution is impossible; therefore, CodeForces’s platform is used for evaluation, which directly supports problems needing special judges.

read the caption

Figure 5: An example of a problem (examples and note parts are omitted) that needs a special judge since there can be multiple valid outputs for the same input (input and outputs refer to test cases but not problem and solutions). e.g., given the input 'abc', acceptable outputs could include 'abb', 'acc', 'aac', and any other string derived from 'abc' except itself. So we cannot simply compare the output with a predetermined correct solution for evaluation in this problem. CodeForces addresses this by evaluating the code submissions directly on their official platform, marking its first support for this kind of problem. The complete problem can be found at https://codeforces.com/contest/2047/problem/B.

More on tables

| Problem | Diffculty |

|---|

🔼 Table 2 presents a statistical summary of CodeForces contests categorized by difficulty division. It shows the number of contests within each division (Div. 1, Div. 1+2, Div. 2, Div. 3, Div. 4), the average number of problems per contest within each division, the average problem rating across the problems in each division, and the approximate CodeForces rating range required to successfully solve problems in each division.

read the caption

Table 2: Basic statics of different contest divisions.

| Zero False | Positive? |

|---|

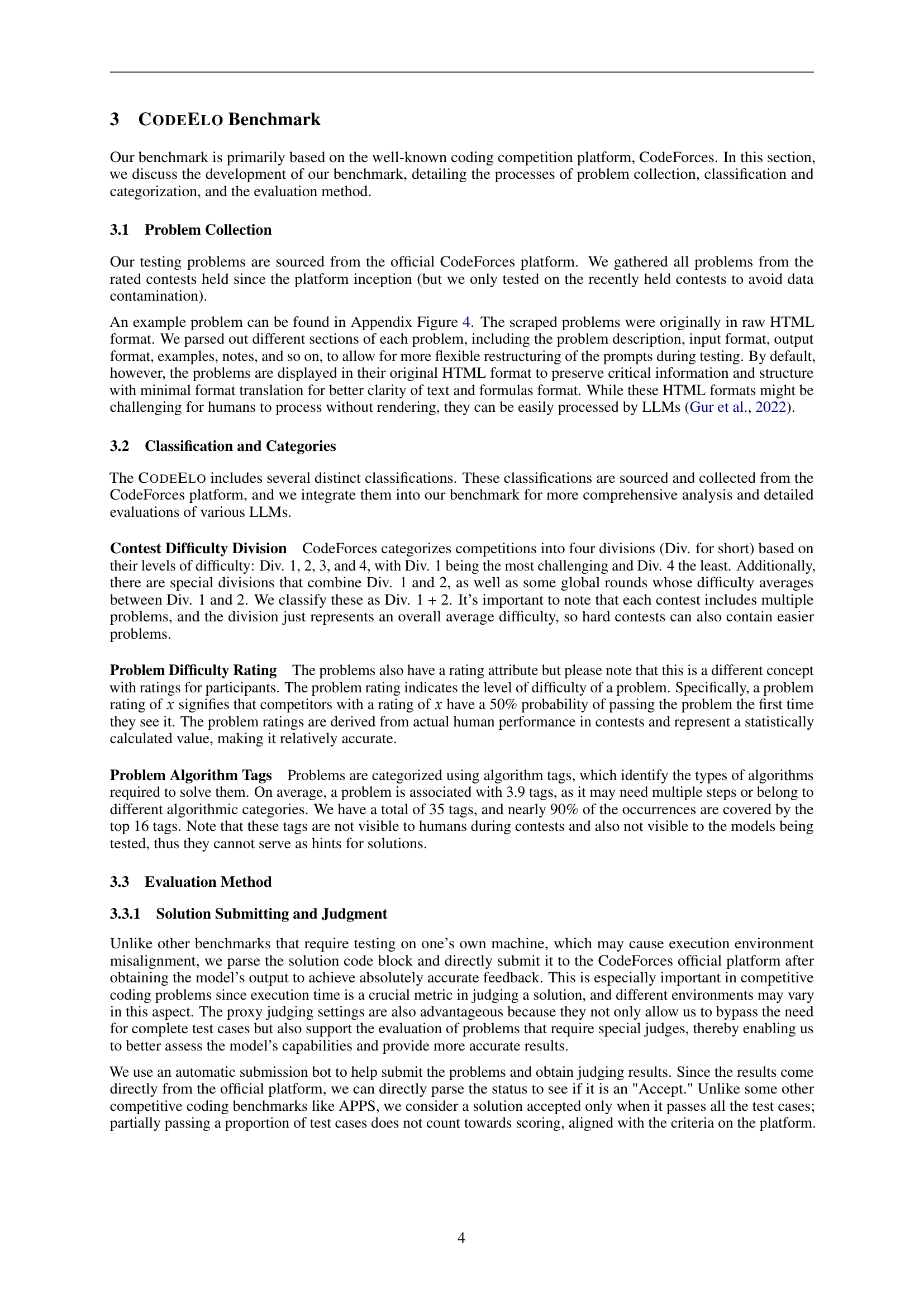

🔼 This table presents the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the CODEELO benchmark, a competition-level code generation benchmark based on CodeForces problems. For each LLM, it shows the overall Elo rating (a measure of skill relative to human competitors), pass rates at different problem difficulty levels (Easy, Medium, Hard), and pass rates at various numbers of attempts (pass@1, pass@2, pass@4, pass@8). The Elo rating is accompanied by the percentile rank the model achieved compared to human participants. The table also categorizes LLMs by size (1B+, 6B+, 13B+, 30B+), highlighting the best performance for each size category.

read the caption

Table 3: Main results of different LLMs on CodeForces. The number in parentheses after the overall Elo rating shows the percentile rank among human participants. The underlined numbers represent the best scores within the same model size range.

| Special | Judge? |

|---|

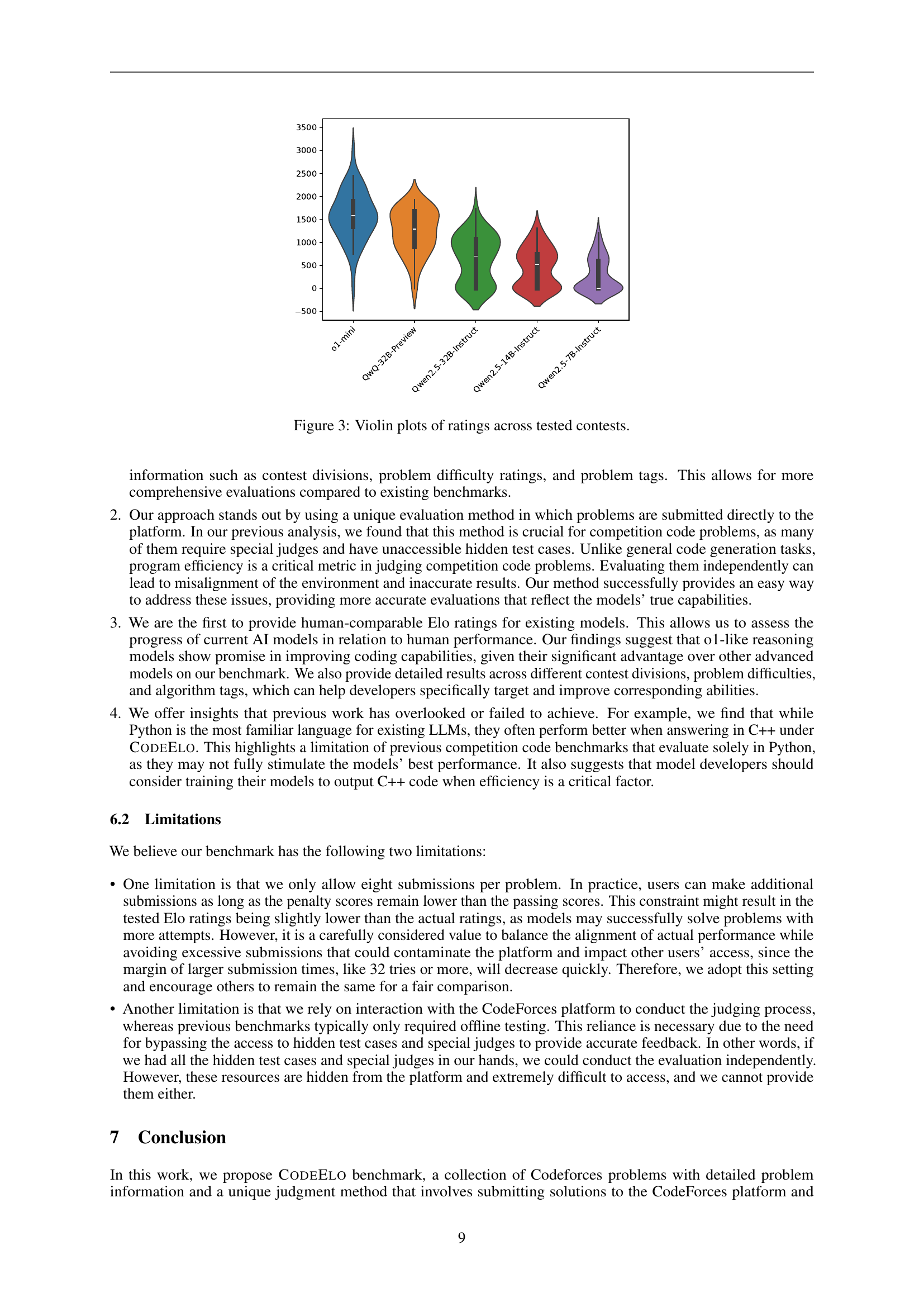

🔼 This table presents the success rate (pass@1) of various large language models (LLMs) across 16 common algorithm categories in solving CodeForces problems. Each category contains at least 30 problems, and the table shows the percentage of problems each model correctly solved on its first attempt. The abbreviations used represent different algorithm types, such as ‘Gr.’ for greedy algorithms, ‘Ma.’ for math-based problems, ‘Im.’ for implementation problems, ‘BF.’ for brute force, ‘DP’ for dynamic programming, ‘DS.’ for data structures, ‘CA.’ for constructive algorithms, ‘BS.’ for binary search, ‘So.’ for sorting algorithms, ‘Gr.’ for graph algorithms, ‘DFS’ for Depth-First Search and similar graph traversal algorithms, ‘NT.’ for number theory problems, ‘Tr.’ for tree-based problems, ‘Co.’ for combinatorics, ‘TP.’ for two-pointer algorithms, and ‘Bi.’ for bitmask algorithms. This detailed breakdown helps analyze the strengths and weaknesses of different LLMs across various algorithm categories.

read the caption

Table 4: Pass rate (pass@1111) on major problem categories that have at least 30 problems tested. The abbreviations 'Gr.', 'Ma.', 'Im.', 'BF.', 'DP', 'DS.', 'CA.', 'BS.', 'So.', 'Gr.', 'DFS', 'NT.', 'Tr.', 'Co.', 'TP.', and 'Bi.' stand for greedy, math, implementation, brute force, dp, data structures, constructive algorithms, binary search, sortings, graphs, dfs and similar, number theory, trees, combinatorics, two pointers, and bitmasks, respectively.

| Aligned | Execution | Environment? |

|---|

🔼 This table lists all the Large Language Models (LLMs) used in the CODEELO benchmark, providing their short names, citations to their original papers, and HuggingFace endpoints where available.

read the caption

Table 5: Model cards.

| Standardized | Elo Rating? |

|---|

🔼 This table shows the distribution of Elo ratings among all human participants on the CodeForces platform during November 2024. Each row represents a percentile (e.g., the 26th percentile means that 26% of human participants had a rating equal to or lower than the rating listed in that row). It illustrates the range of skill levels present within the CodeForces community and provides context for comparing the performance of large language models (LLMs) against human coders, as reported in the paper.

read the caption

Table 6: Percentiles of ratings among all human participants, calculated based on publicly available user ratings from the CodeForces platform, collected in November, 2024.

Full paper#