↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current research focuses on slow-thinking reasoning systems which improve the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) by increasing their ’thinking time’. This approach is being adapted for multimodal LLMs, but these systems are complex, and the mechanisms of slow-thinking are not well understood. This paper explores a simpler method: fine-tuning a capable MLLM with a small amount of text-based long-form thought data. This resulted in a multimodal slow-thinking system called Virgo.

The researchers found that the text-based long-form reasoning data was effectively transferred to the MLLM, improving performance significantly. Surprisingly, text-based data was even more effective than using visual data in improving reasoning capabilities. This suggests that the language model component is fundamentally associated with slow-thinking and that this capability is transferable across various modalities. This research provides a straightforward approach to enhancing MLLMs, addressing limitations in current multimodal reasoning systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it explores a novel approach to enhancing multimodal large language models (MLLMs) with slow-thinking capabilities. This addresses a significant gap in current research, where multimodal slow-thinking systems lag behind their text-only counterparts. The findings on the effectiveness of text-based long-form thought data for improving MLLM reasoning have significant implications for the development of future AI systems. The release of resources further facilitates broader research and development in this promising area.

Visual Insights#

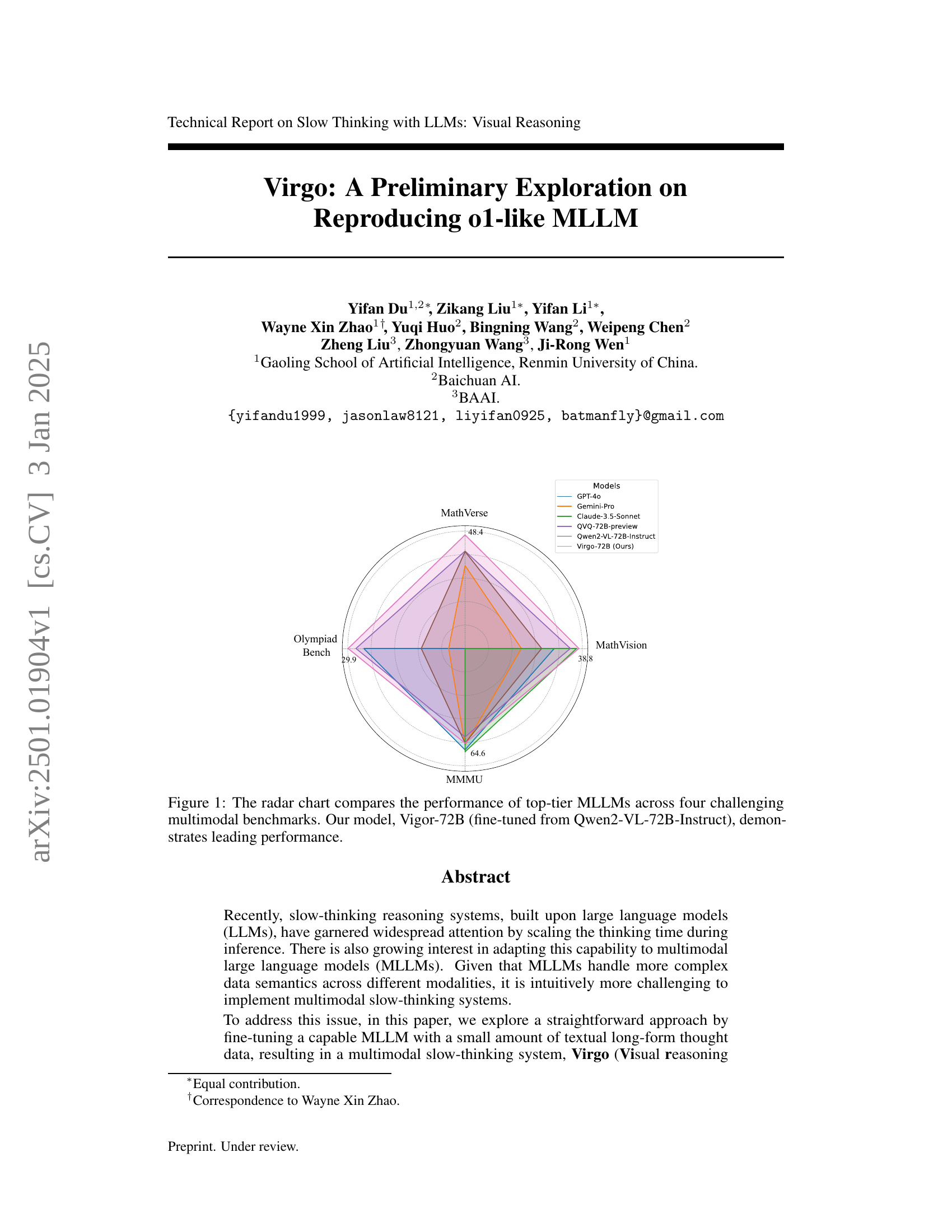

🔼 Figure 1 presents a radar chart comparing the performance of several leading multimodal large language models (MLLMs) across four challenging benchmarks. The benchmarks assess performance on complex reasoning tasks requiring integration of multiple modalities (e.g., text and images). The chart visually displays each model’s relative strengths and weaknesses across these benchmarks. The authors highlight that their model, Virgo-72B, achieves the highest overall performance, indicating superiority in multimodal reasoning capabilities. Virgo-72B is a fine-tuned version of the Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct model.

read the caption

Figure 1: The radar chart compares the performance of top-tier MLLMs across four challenging multimodal benchmarks. Our model, Vigor-72B (fine-tuned from Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct), demonstrates leading performance.

| Domain | Geometry | Geometry | Geometry | Geometry | Table, Chart, and Figure | Table, Chart, and Figure | Table, Chart, and Figure | Object |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset | Geos | GeoQA+ | Geometry3K | UniGeo | TabMWP | FigureQA | ChartQA | CLEVR |

| # Samples | 279 | 563 | 551 | 555 | 568 | 589 | 509 | 548 |

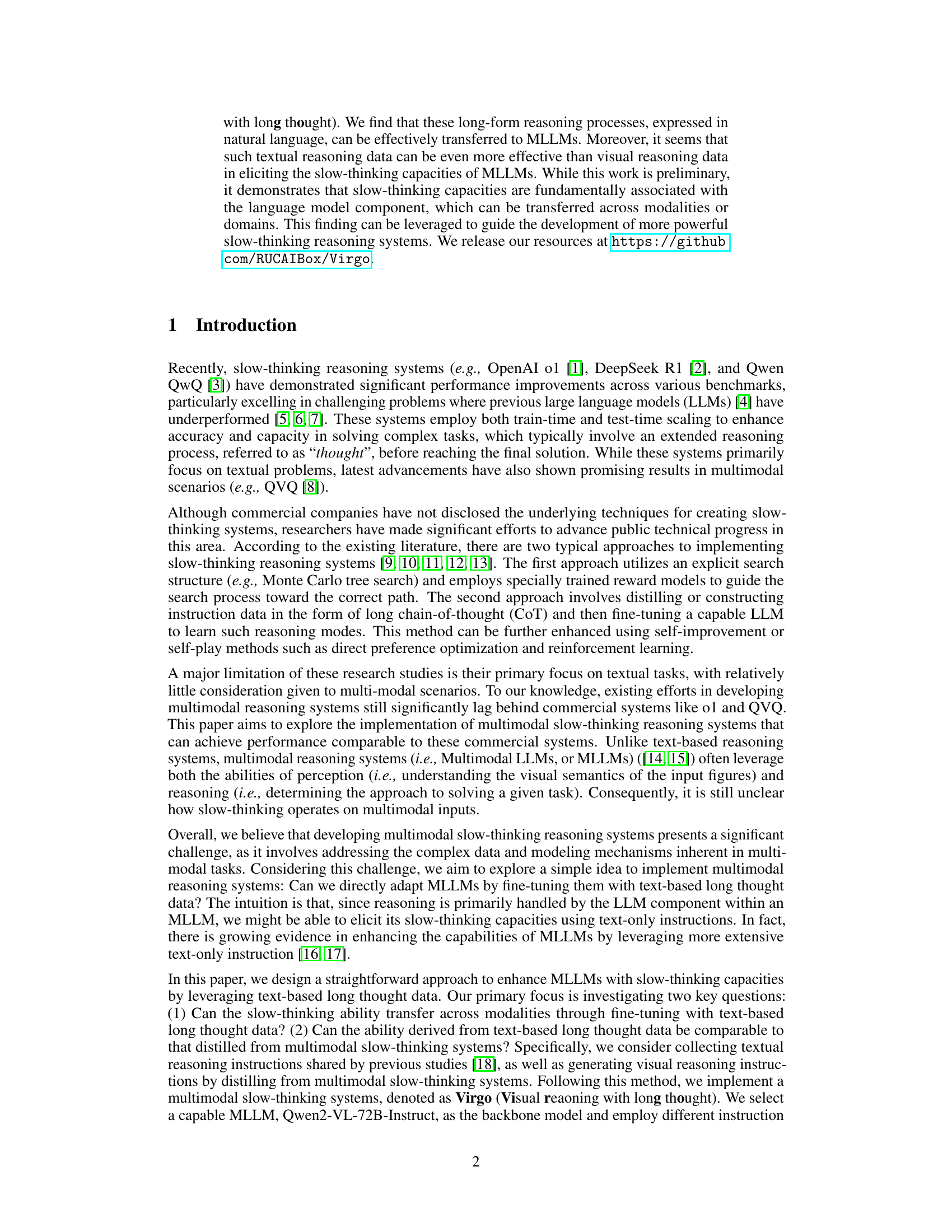

🔼 Table 1 presents a detailed breakdown of the statistics for four different geometry datasets (Geos, GeoQA+, Geometry3K, UniGeo), three table and figure datasets (TabMWP, FigureQA, ChartQA), and one object dataset (CLEVR). For each dataset, the table shows the number of samples available. These datasets were used as sources for visual question answering (VQA) problems to gather multimodal long thought data in the study.

read the caption

Table 1: The statistics of the selected visual query sources

In-depth insights#

MLLM Slow Thinking#

The concept of “MLLM Slow Thinking” explores enhancing the reasoning capabilities of large multimodal language models (MLLMs). The core idea is to leverage the inherent strengths of LLMs within MLLMs by extending their thinking time during inference, thus improving accuracy and depth of reasoning on complex multimodal tasks. This approach contrasts with traditional methods focused on explicit search structures or complex multimodal data. The paper investigates transferring slow-thinking abilities from text-based LLMs to MLLMs via fine-tuning with long-form textual thought data, finding that this approach is surprisingly effective. This suggests that slow thinking may be fundamentally associated with the language model component of MLLMs, easily transferable across modalities. While achieving comparable performance to existing commercial systems, the study also highlights limitations of relying solely on text-based data, particularly for visual reasoning tasks requiring sophisticated perception and analysis. Future research should focus on the generation of high-quality multimodal thought data and explore the interplay between perceptual and reasoning components within MLLMs to further enhance their slow-thinking capabilities.

Text-Based Transfer#

The concept of ‘Text-Based Transfer’ in the context of multimodal slow-thinking systems is intriguing. It proposes leveraging the readily available abundance of textual long-form thought data to enhance the reasoning capabilities of multimodal large language models (MLLMs). The core idea is that slow-thinking reasoning is a fundamental characteristic of the language model component, and this ability can be transferred across modalities by fine-tuning an MLLM with textual data. This approach offers a straightforward and efficient alternative to acquiring and utilizing more scarce multimodal data. The success of this approach suggests that the language model’s capacity for reasoning is paramount, potentially outweighing the importance of direct visual reasoning data for eliciting slow-thinking in MLLMs. This finding is a significant contribution to understanding the architecture of MLLMs and simplifies the data requirements for training more powerful multimodal reasoning systems. However, limitations remain: the approach may not always generalize perfectly across all types of multimodal tasks, especially ones that heavily rely on visual perception. Further research into the optimal balance between textual and visual data, along with a deep dive into the mechanisms of knowledge transfer, is needed to fully unlock the potential of this approach.

Multimodal Tuning#

Multimodal tuning in large language models (LLMs) presents a significant challenge, as it involves adapting models trained primarily on text to handle diverse data types like images and audio. A key consideration is how to effectively integrate information from different modalities. Simple concatenation of textual and visual features might not suffice; more sophisticated methods like cross-modal attention mechanisms or fusion strategies could be explored to allow the model to learn meaningful relationships between different data types. The effectiveness of multimodal tuning is also greatly dependent on the quality and quantity of training data, requiring a well-curated dataset representative of real-world applications. Careful design of the training process, including the choice of loss functions and optimization algorithms, is critical for successful multimodal learning. Furthermore, evaluating the performance of a multimodal LLM requires tailored metrics beyond standard textual accuracy, as the nature of multimodal reasoning is inherently complex and nuanced. Finally, successful multimodal tuning will likely depend on both architectural choices (e.g., whether to use a unified model or separate encoders for each modality) and effective training strategies.

Instruction Data Impact#

The research reveals a significant impact of instruction data on the performance of multimodal slow-thinking systems. Text-based long-form thought data proves surprisingly effective, often outperforming or matching multimodal data in eliciting slow-thinking capabilities. This suggests that the core reasoning mechanism resides within the language model component of the MLLM, which can be effectively transferred across modalities via textual instructions. However, the study also highlights that longer instructions do not always correlate with better performance. Indeed, excessively long instructions, particularly those dominated by complex mathematical problems, can lead to performance degradation. A balanced approach, utilizing a mix of instruction data lengths and domains, is vital for optimal results. Finally, the effectiveness of instruction data is also shown to be model-size dependent, underscoring the importance of carefully selecting training data to match the capacity and strengths of the MLLM in use.

Future MLLM Research#

Future research in Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) should prioritize addressing limitations in handling complex reasoning and improving the robustness of MLLMs. Further exploration of effective training methodologies for slow-thinking reasoning in MLLMs is crucial. Combining textual and visual reasoning data during training warrants investigation to leverage strengths of both modalities. Benchmark development needs to focus on creating challenges that truly assess MLLM reasoning abilities, moving beyond simple question-answering tasks. Addressing perceptual biases present in MLLMs and their impact on reasoning is essential, alongside developing techniques for improving transparency and explainability. Finally, investigating effective methods for scaling MLLMs to handle longer contexts and more complex multimodal inputs will be critical to unlocking their full potential for higher-level tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

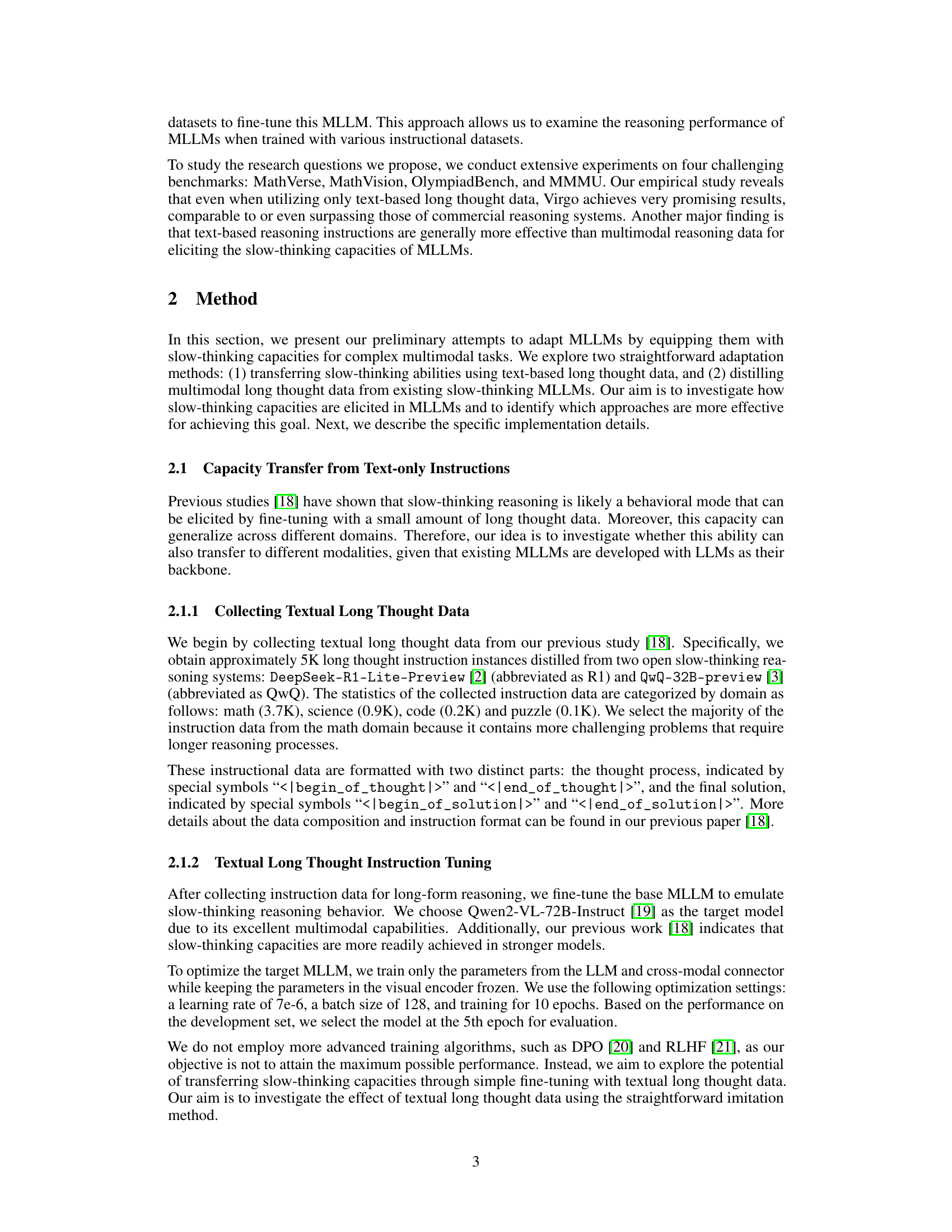

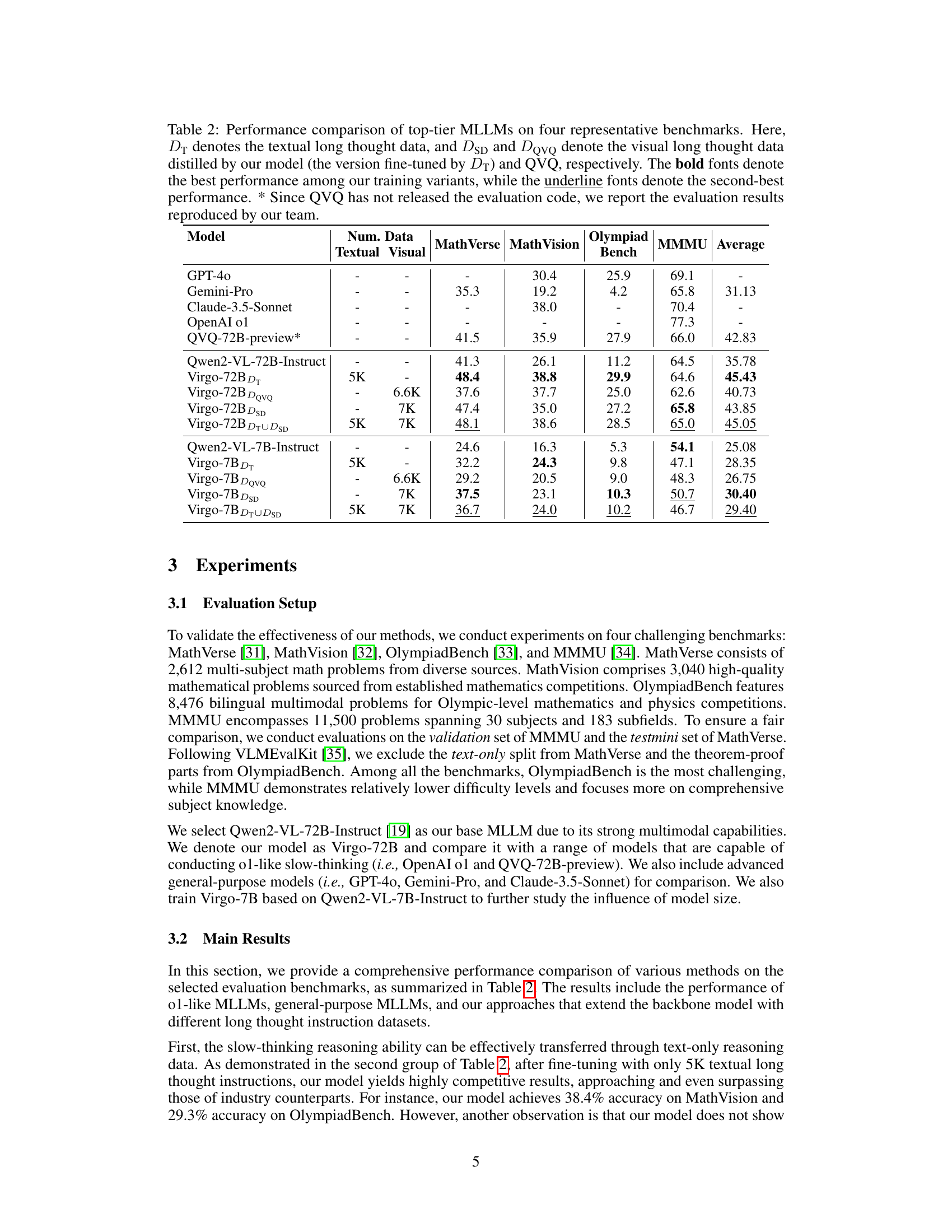

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates the correlation between the average length of reasoning processes (thought length) in different benchmarks and the performance of two models: Virgo and Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct. The graph uses lines to represent the average thought length for each benchmark (MMMU, MathVerse, MathVision, and OlympiadBench), and bars to show the corresponding performance scores of both models on those benchmarks. Lighter bars indicate Virgo’s performance, and darker bars represent Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct’s performance. The figure visually demonstrates a positive correlation: longer average thought lengths generally lead to better performance for both models, indicating that more extensive reasoning improves accuracy in complex problem-solving tasks.

read the caption

Figure 2: The relationship between the average thought length of each benchmark and the corresponding performance of both Virgo and Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct. The “average thought length” is represented by the line, while “performance” is indicated by the bar. The bars in light color represent Vigor’s performance, while the bars in dark color represent Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct’s performance. We observe that benchmarks with longer thought lengths generally correspond to greater performance improvements.

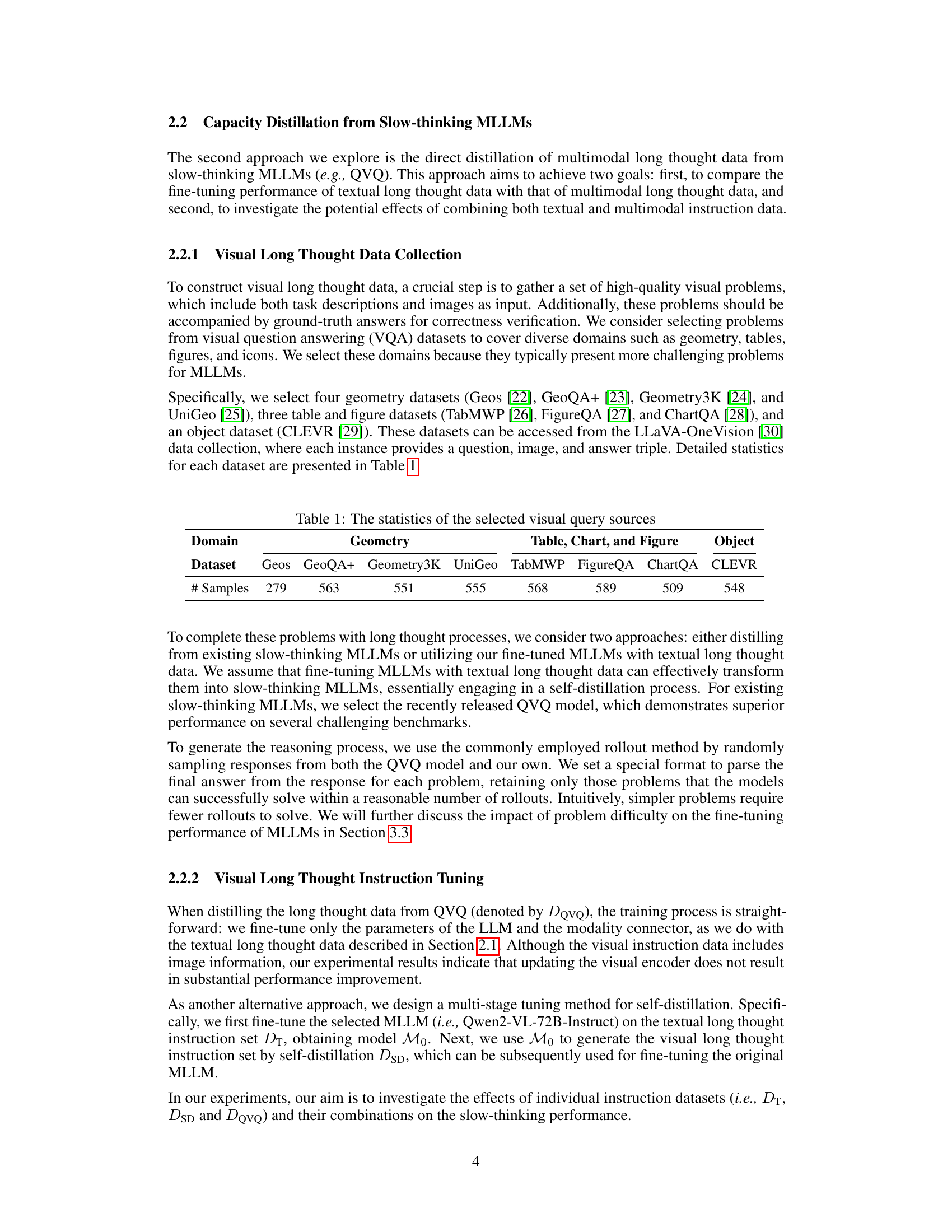

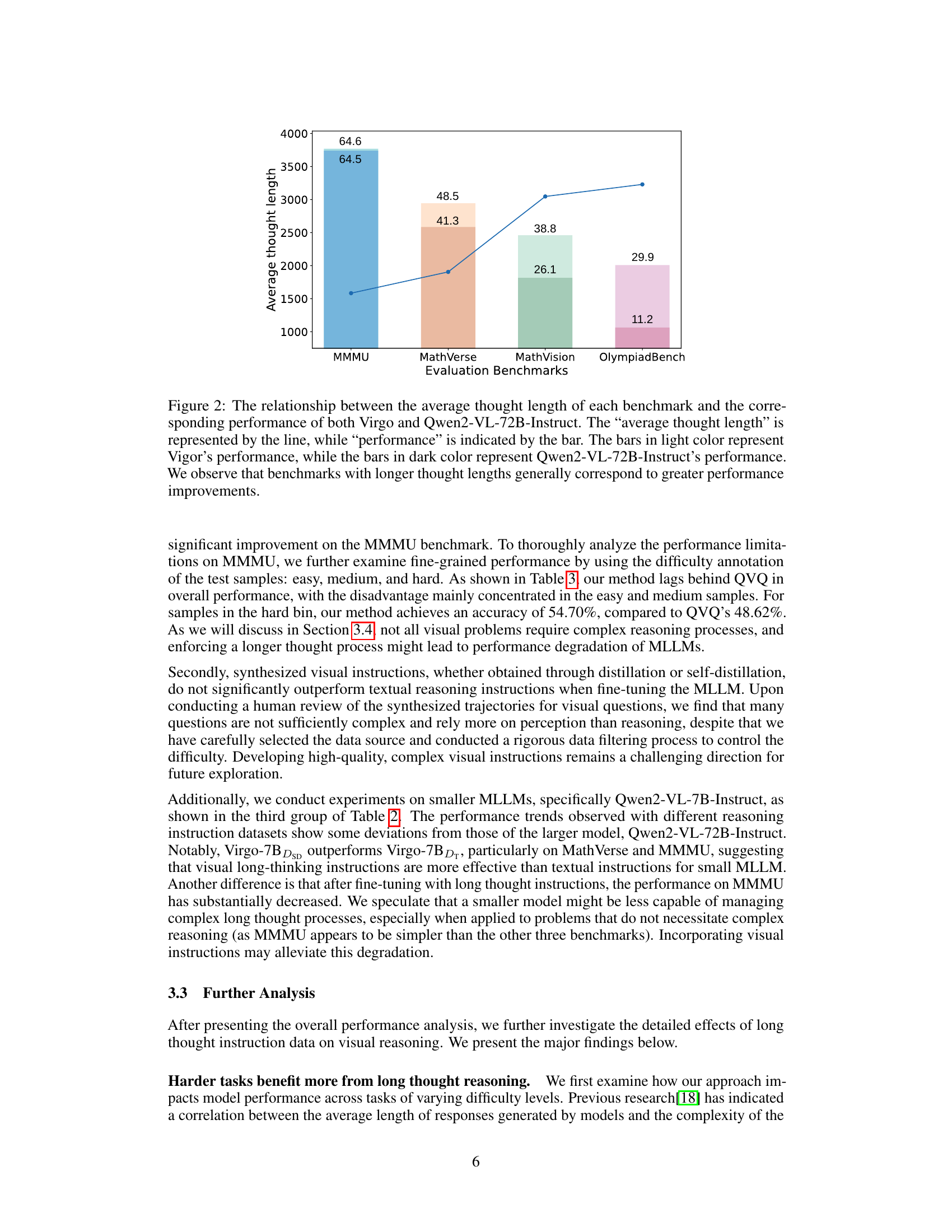

🔼 This figure shows a breakdown of the textual long-form thought instruction data used to train the Virgo model. It displays the proportion of instructions belonging to different domains: math, code, science, and puzzle. The visualization helps illustrate the relative quantity of data from each domain, indicating the focus on mathematical problems within the overall training dataset.

read the caption

Figure 3: The domain distribution of textual long thought instructions.

More on tables

| Model | Num. Data | MathVerse | MathVision | MMMU | Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | - | - | - | 30.4 | 25.9 | 69.1 | - | |

| Gemini-Pro | - | - | 35.3 | 19.2 | 4.2 | 65.8 | 31.13 | |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet | - | - | - | 38.0 | - | 70.4 | - | |

| OpenAI o1 | - | - | - | - | - | 77.3 | - | |

| QVQ-72B-preview* | - | - | 41.5 | 35.9 | 27.9 | 66.0 | 42.83 | |

| Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct | - | - | 41.3 | 26.1 | 11.2 | 64.5 | 35.78 | |

| Virgo-72BDT | 5K | - | 48.4 | 38.8 | 29.9 | 64.6 | 45.43 | |

| Virgo-72BDQVQ | - | 6.6K | 37.6 | 37.7 | 25.0 | 62.6 | 40.73 | |

| Virgo-72BDSD | - | 7K | 47.4 | 35.0 | 27.2 | 65.8 | 43.85 | |

| Virgo-72BDT∪DSD | 5K | 7K | 48.1 | 38.6 | 28.5 | 65.0 | 45.05 | |

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct | - | - | 24.6 | 16.3 | 5.3 | 54.1 | 25.08 | |

| Virgo-7BDT | 5K | - | 32.2 | 24.3 | 9.8 | 47.1 | 28.35 | |

| Virgo-7BDQVQ | - | 6.6K | 29.2 | 20.5 | 9.0 | 48.3 | 26.75 | |

| Virgo-7BDSD | - | 7K | 37.5 | 23.1 | 10.3 | 50.7 | 30.40 | |

| Virgo-7BDT∪DSD | 5K | 7K | 36.7 | 24.0 | 10.2 | 46.7 | 29.40 |

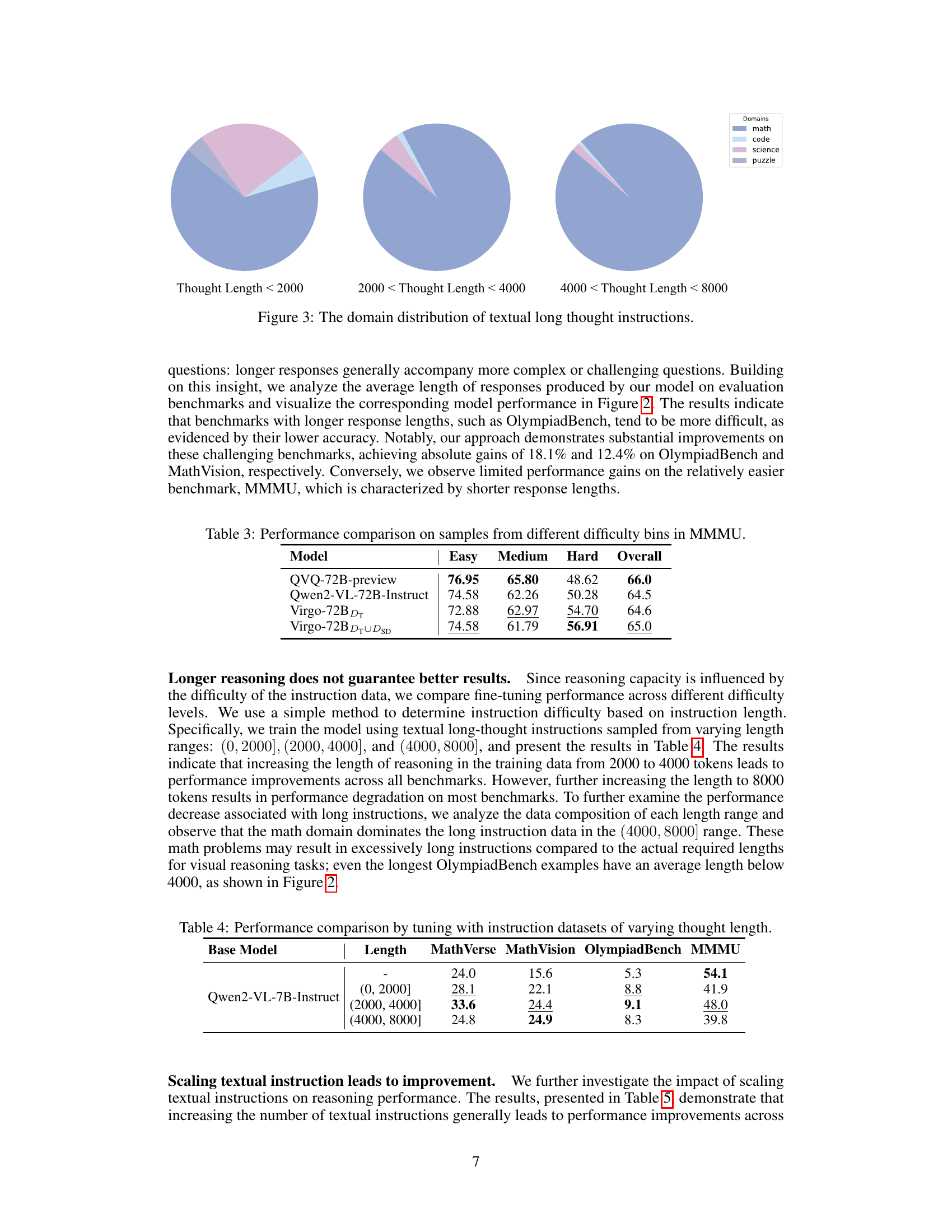

🔼 Table 2 presents a performance comparison of leading large language models (LLMs) on four challenging benchmarks: MathVerse, MathVision, OlympiadBench, and MMMU. The LLMs are evaluated based on their performance with different types of training data: textual long thought data (DT), visual long thought data distilled from the model fine-tuned on textual data (DSD), and visual long thought data distilled from the QVQ model (DQVQ). The table highlights the best and second-best performing models for each benchmark and provides the average performance across all four benchmarks, showcasing the impact of various training datasets on the model’s reasoning capabilities. Note that the QVQ results are reproduced by the authors due to the lack of publicly available evaluation code.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance comparison of top-tier MLLMs on four representative benchmarks. Here, DTsubscript𝐷TD_{\text{T}}italic_D start_POSTSUBSCRIPT T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denotes the textual long thought data, and DSDsubscript𝐷SDD_{\text{SD}}italic_D start_POSTSUBSCRIPT SD end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and DQVQsubscript𝐷QVQD_{\text{QVQ}}italic_D start_POSTSUBSCRIPT QVQ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denote the visual long thought data distilled by our model (the version fine-tuned by DTsubscript𝐷TD_{\text{T}}italic_D start_POSTSUBSCRIPT T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) and QVQ, respectively. The bold fonts denote the best performance among our training variants, while the underline fonts denote the second-best performance. * Since QVQ has not released the evaluation code, we report the evaluation results reproduced by our team.

| Model | Easy | Medium | Hard | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QVQ-72B-preview | 76.95 | 65.80 | 48.62 | 66.0 |

| Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct | 74.58 | 62.26 | 50.28 | 64.5 |

| Virgo-72BDT | 72.88 | 62.97 | 54.70 | 64.6 |

| Virgo-72BDT∪DSD | 74.58 | 61.79 | 56.91 | 65.0 |

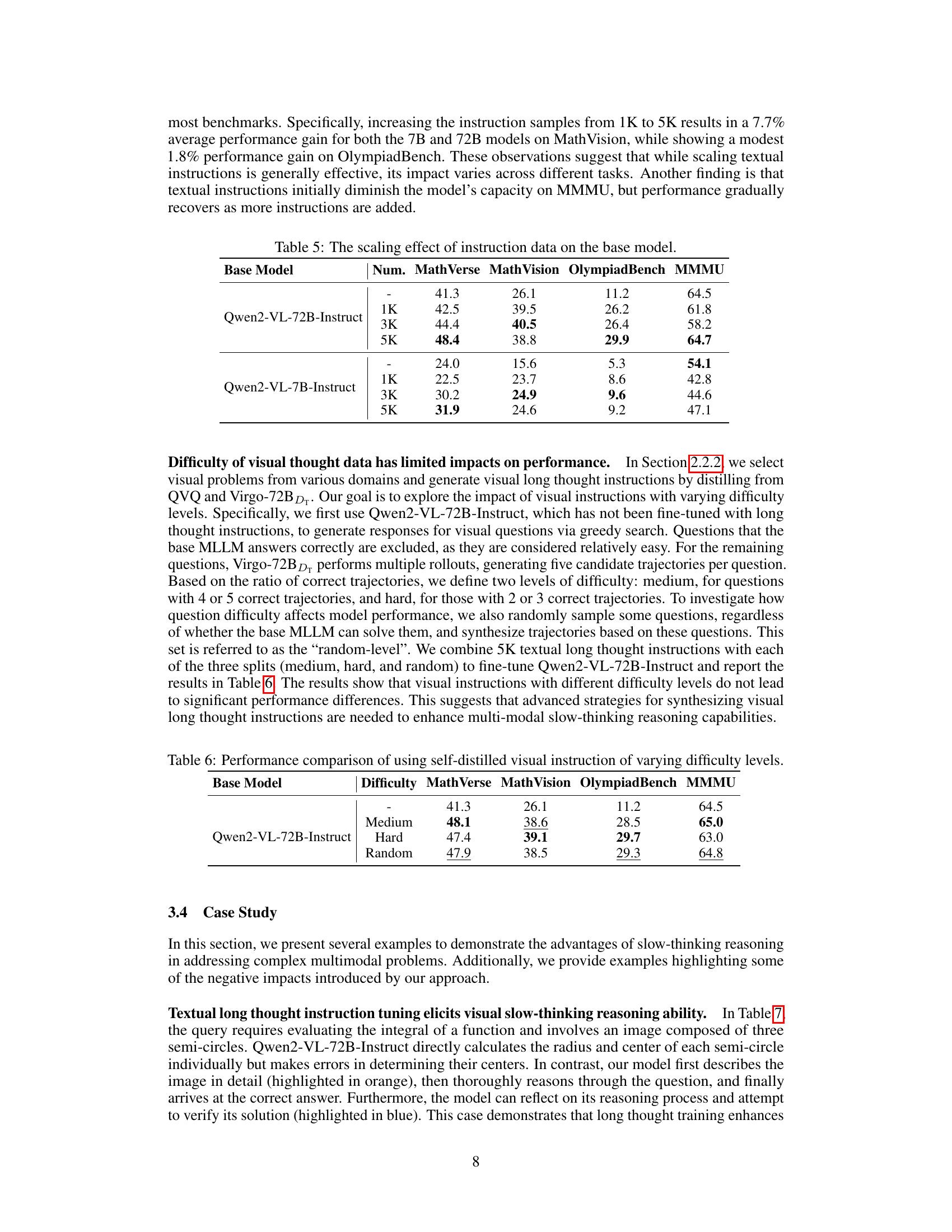

🔼 This table presents a performance comparison of different models on the MMMU benchmark, broken down by the difficulty level of the questions (easy, medium, hard). It shows the accuracy of each model for each difficulty level and overall. This allows for a more granular analysis of model performance, revealing potential strengths and weaknesses at different levels of problem complexity.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance comparison on samples from different difficulty bins in MMMU.

| Base Model | Length | MathVerse | MathVision | OlympiadBench | MMMU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct | - | 24.0 | 15.6 | 5.3 | 54.1 |

| (0, 2000] | 28.1 | 22.1 | 8.8 | 41.9 | |

| (2000, 4000] | 33.6 | 24.4 | 9.1 | 48.0 | |

| (4000, 8000] | 24.8 | 24.9 | 8.3 | 39.8 |

🔼 This table presents a performance comparison of a model fine-tuned using instruction datasets with varying lengths of thought processes. It shows the impact of different thought lengths on the model’s performance across four benchmarks: MathVerse, MathVision, OlympiadBench, and MMMU. The results are presented for the base model (Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct) and three different lengths of instruction datasets: (0, 2000], (2000, 4000], and (4000, 8000]. This helps in understanding the relationship between the length of the reasoning process in the training data and the resulting performance of the model.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance comparison by tuning with instruction datasets of varying thought length.

| Base Model | Num. | MathVerse | MathVision | OlympiadBench | MMMU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct | - | 41.3 | 26.1 | 11.2 | 64.5 |

| 1K | 42.5 | 39.5 | 26.2 | 61.8 | |

| 3K | 44.4 | 40.5 | 26.4 | 58.2 | |

| 5K | 48.4 | 38.8 | 29.9 | 64.7 | |

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct | - | 24.0 | 15.6 | 5.3 | 54.1 |

| 1K | 22.5 | 23.7 | 8.6 | 42.8 | |

| 3K | 30.2 | 24.9 | 9.6 | 44.6 | |

| 5K | 31.9 | 24.6 | 9.2 | 47.1 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment examining the impact of scaling the amount of textual instruction data used to fine-tune a base multimodal large language model (MLLM). It shows how the model’s performance across four different benchmarks (MathVerse, MathVision, OlympiadBench, and MMMU) changes as the number of instructions increases from 1,000 to 5,000. The base MLLMs used are Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct and Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct, allowing for the investigation of scale effects.

read the caption

Table 5: The scaling effect of instruction data on the base model.

| Base Model | Difficulty | MathVerse | MathVision | OlympiadBench | MMMU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct | - | 41.3 | 26.1 | 11.2 | 64.5 |

| Medium | 48.1 | 38.6 | 28.5 | 65.0 | |

| Hard | 47.4 | 39.1 | 29.7 | 63.0 | |

| Random | 47.9 | 38.5 | 29.3 | 64.8 |

🔼 This table presents a performance comparison of a multimodal large language model (MLLM) fine-tuned using self-distilled visual instructions with varying difficulty levels. It compares the model’s performance across four challenging benchmarks: MathVerse, MathVision, OlympiadBench, and MMMU. The difficulty levels of the visual instructions are categorized as ‘Medium’, ‘Hard’, and ‘Random’, reflecting the complexity of the reasoning processes involved. The table shows the impact of instruction difficulty on the MLLM’s ability to perform slow-thinking reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Table 6: Performance comparison of using self-distilled visual instruction of varying difficulty levels.

| Problem | Ground Truth | Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct | Virgo-72B (ours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7π | To evaluate the integral of the functions graphed using the formula for circles, we need to identify the equations of the circles and then integrate them over the appropriate intervals. 1. Identify the Equations of the Circles: … 4. Final Answer: 18π | Alright, I’ve got this graph here with three semicircles plotted. The x-axis ranges from 0 to 12, and the y-axis goes up to 5. Each semicircle is labeled with an expression involving x. … So, this simplifies to … |

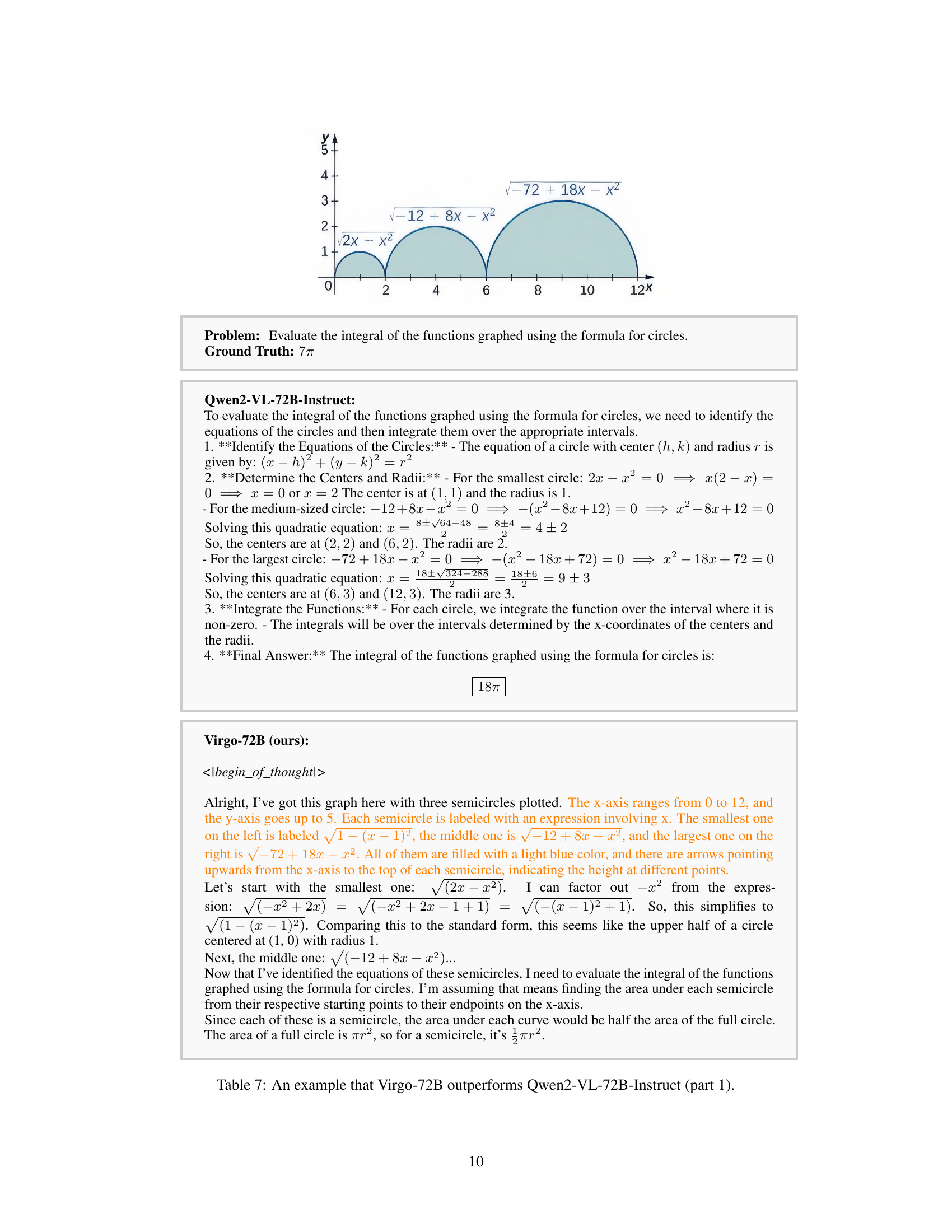

🔼 This table showcases a comparative analysis of the problem-solving approaches employed by two different large language models (LLMs): Virgo-72B and Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct. The models are tasked with evaluating the integral of a function depicted graphically, and the table highlights the step-by-step reasoning processes of each model, demonstrating Virgo-72B’s superior performance and more detailed explanation.

read the caption

Table 7: An example that Virgo-72B outperforms Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct (part 1).

| Image | Description |

|---|---|

| https://arxiv.org/html/2501.01904/S4.T8.1.1.1.1.p1.pic1.png | Let’s calculate the area for each semicircle: |

- Smallest semicircle: radius r=1, so area = π/2.

- Middle semicircle:…… So, the total area under all three semicircles is 7π. |

🔼 Table 8 presents a comparison of the performance of two models, Virgo-72B and Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct, on a specific visual reasoning task. It shows how Virgo-72B, equipped with slow-thinking reasoning capabilities through textual long-form thought data, not only arrives at the correct answer but also demonstrates a more comprehensive and self-reflective reasoning process compared to Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct. The table highlights the advantages of the slow-thinking approach by showcasing a more detailed and insightful solution process, indicating improved accuracy and reasoning depth.

read the caption

Table 8: An example that Virgo-72B outperforms Qwen2-VL-72B-Instruct (part 2)

| Model | Image | Text |

|---|---|---|

| https://arxiv.org/html/2501.01904/x5.png | Problem: Graph 1 shows the number of unemployed (in thousands) over a five-month period, organized by level of education completed. The difference between the number of unemployed high school graduates and the number of unemployed workers without a high school diploma was smallest in . A. June B. July C. August D. September E. October Ground Truth: D. September |

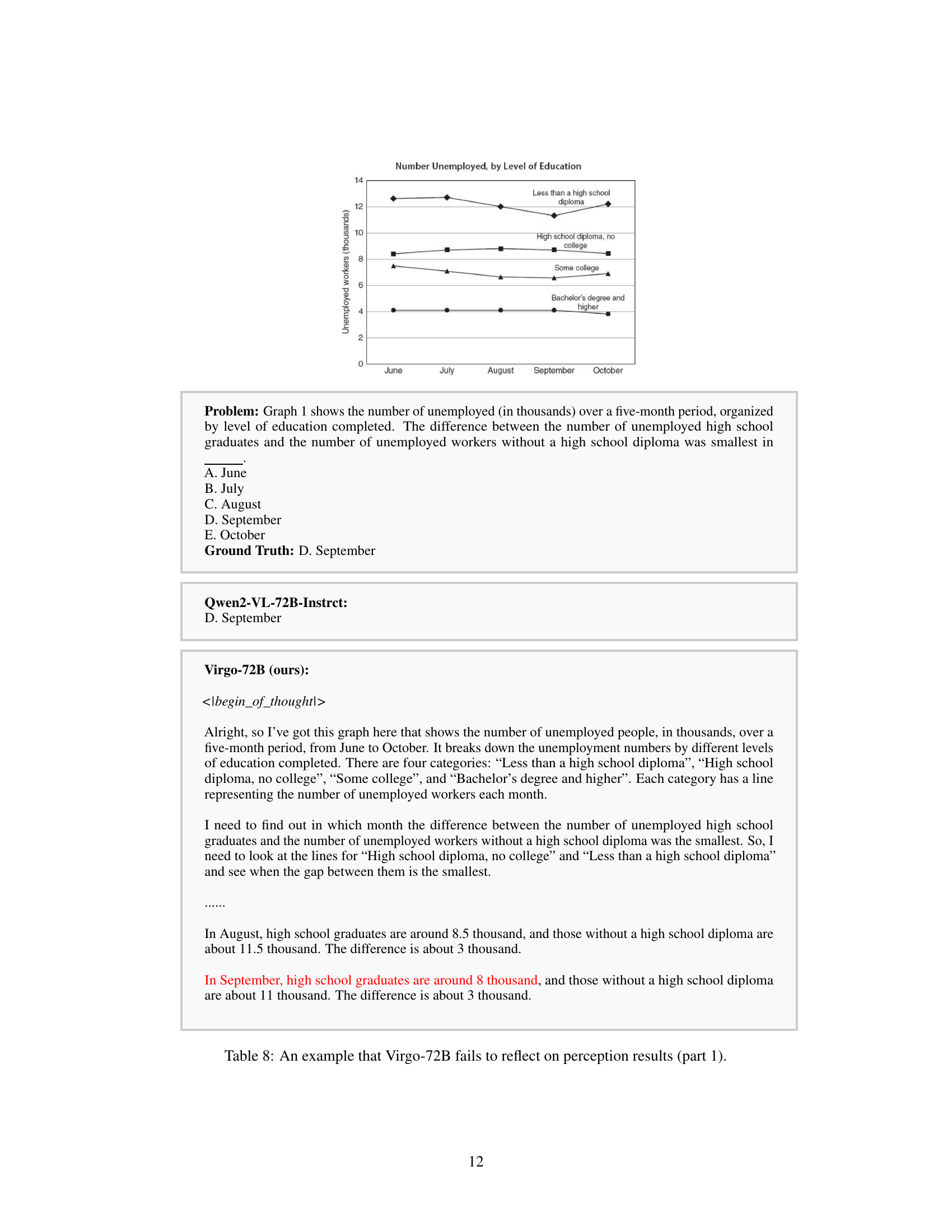

🔼 This table showcases a case where the Virgo-72B model demonstrates a failure in its reasoning process due to an incorrect interpretation of the input graph. The model correctly identifies the question but makes an error in its initial assessment of the number of unemployed individuals in a specific category during a given month. While the model recognizes an inconsistency in its findings and attempts to correct itself, it ultimately fails to question the flawed visual data interpretation and reaches an incorrect final answer. The example illustrates a key limitation: the model’s inability to effectively self-correct when a perceptual error affects its reasoning chain.

read the caption

Table 9: An example that Virgo-72B fails to reflect on perception results (part 1).

| Month | High School Graduates | No High School Diploma | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| June | 4000 | ||

| July | 3500 | ||

| August | 8500 | 11500 | 3000 |

| September | 8000 | 11000 | 3000 |

| October | 8000 | 12000 | 4000 |

🔼 This table showcases an example where the Virgo-72B model demonstrates a failure to reflect on its initial perception of the data. Specifically, it incorrectly interprets data from a graph showing unemployment numbers over five months, categorized by educational attainment. The model initially identifies the smallest difference between two unemployment categories (high school graduates and those with less than a high school diploma) and even correctly mentions the months where the difference is smallest. However, it fails to maintain this consistency in its reasoning, leading to a faulty and ultimately incorrect final answer.

read the caption

Table 10: An example that Virgo-72B fails to reflect on perception results (part 2).

Full paper#