↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current methods for evaluating large language models (LLMs) in complex tool use scenarios are limited by the lack of reliable datasets. Existing datasets often use a tool-driven approach, failing to ensure that tools are interconnected, that queries genuinely require multi-hop reasoning, and that the answers are verifiable. This leads to biased evaluations and unreliable insights.

ToolHop introduces a novel query-driven approach to constructing a benchmark dataset. It focuses on generating diverse multi-hop queries first and then constructing tools to solve them, ensuring the interdependency of tools and the authenticity of the multi-hop nature of the queries. The project rigorously evaluates 14 LLMs across 5 model families. The evaluation reveals substantial challenges in handling multi-hop tool use, with even state-of-the-art models achieving only moderate accuracy. Detailed analysis of ToolHop offers actionable insights into the varying tool-use strategies employed by different LLM families, paving the way for the development of more efficient and robust LLM models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it introduces a novel, rigorously evaluated benchmark dataset called ToolHop for assessing LLM capabilities in multi-hop tool use. The dataset addresses limitations of existing benchmarks by using a query-driven approach, ensuring diverse and meaningful queries that genuinely require multi-hop reasoning. This allows for more reliable and informative evaluation of LLMs’ tool-use abilities, guiding further research and development in this important area of AI.

Visual Insights#

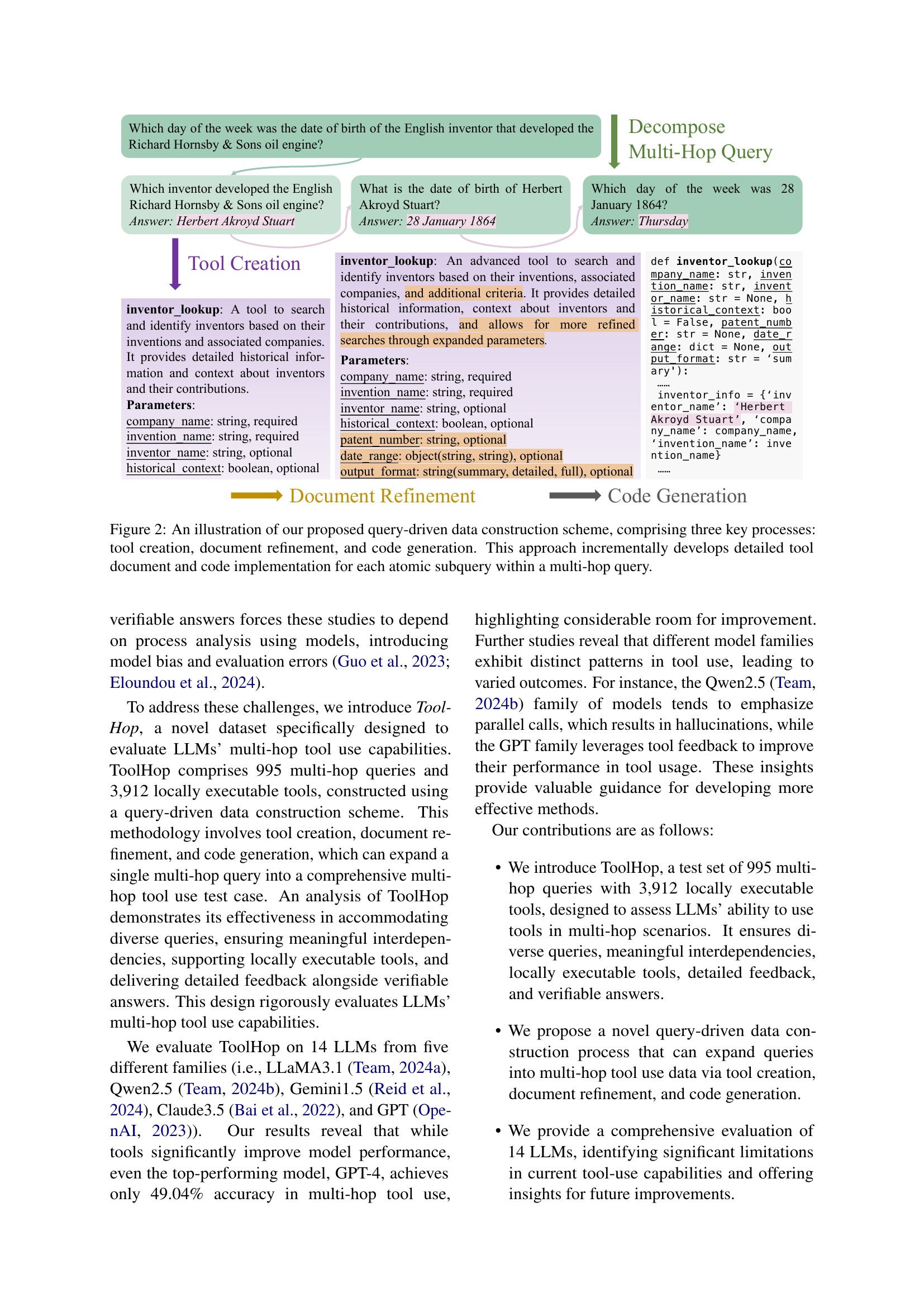

🔼 This figure illustrates the multi-hop tool use process. A complex user query is broken down into smaller, individual sub-queries. Each sub-query is then processed by invoking an appropriate tool. The tool’s response (feedback) is used to inform subsequent sub-query processing, creating an iterative cycle. This continues until all sub-queries are answered and the final answer to the original, complex query is obtained. The process highlights the need for comprehension, reasoning, and the ability to properly call and manage external tools (functions).

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of multi-hop tool use. The process entails decomposing a complex multi-hop query into multiple atomic sub-queries, sequentially invoking the appropriate tools, retrieving results from the tool feedback, and iterating until the final answer is derived. This demonstrates the integration of comprehension, reasoning, and function-calling capabilities.

| # Tools | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Data | 428 | 353 | 136 | 10 | 68 |

🔼 This table shows the distribution of the number of tools needed to answer each question in the ToolHop dataset. It breaks down how many queries required three, four, five, six or seven tools to arrive at a solution. This data provides insights into the complexity of the queries within the dataset and the level of multi-hop reasoning required.

read the caption

Table 1: Distribution of the number of tools required to solve each query in ToolHop.

In-depth insights#

Multi-hop Tool Use#

Multi-hop tool use signifies a significant evolution in large language model (LLM) capabilities, demanding a more nuanced evaluation than previous single-step assessments. It necessitates LLMs to break down complex queries into smaller, manageable sub-queries, executing a sequence of tools, and integrating intermediate results to reach the final answer. This process showcases advanced reasoning and comprehension skills, including the ability to understand tool functionalities, select appropriate tools, and manage the flow of information. The evaluation of multi-hop tool use thus requires sophisticated benchmarks which go beyond simple accuracy measures. Such benchmarks must account for the complex interplay of query decomposition, tool selection, error handling, and the overall reasoning chain, highlighting not only the final result but also the intermediate steps and potential points of failure. Therefore, rigorous evaluation datasets are crucial for advancing LLM research and development in this area, enabling the creation of more robust and intelligent systems.

Query-Driven Data#

The concept of ‘Query-Driven Data’ introduces a paradigm shift in dataset creation, moving away from the traditional tool-centric approach. Instead of assembling tools first and then generating queries, this method prioritizes the user query. This ensures that the resulting dataset is directly relevant to practical user needs, avoiding potential biases from tool selection. The process then iteratively builds the necessary tools, documents, and code to address the query. This approach inherently creates interdependencies between tools, reflecting the complexities of real-world scenarios. A key strength is the inherent focus on multi-hop reasoning. This iterative query-driven approach thus naturally generates multi-hop scenarios, reflecting how users often need to combine multiple tools to solve complex problems. Further, the process naturally lends itself to creating verifiable answers, strengthening the dataset’s robustness and enabling more rigorous evaluation of large language models (LLMs). Overall, ‘Query-Driven Data’ offers a more realistic and effective approach to benchmarking LLM capabilities in multi-hop tool use.

LLM Tool Use Gaps#

The heading “LLM Tool Use Gaps” suggests an analysis of shortcomings in Large Language Models’ (LLMs) ability to effectively utilize external tools. A comprehensive exploration would likely delve into specific types of tool usage failures, such as incorrect tool selection, misinterpretation of tool outputs, inability to handle multi-step processes (requiring multiple tools), and struggles with tools requiring complex or nuanced interactions. Performance comparisons across different LLM architectures would be crucial, highlighting architectural strengths and weaknesses in tool integration. Furthermore, the analysis should identify the root causes of these gaps, possibly including insufficient training data incorporating tool interactions, limitations in reasoning and planning capabilities, and inadequate mechanisms for error handling and recovery during tool usage. Investigating the impact of various factors like prompt engineering techniques and tool documentation quality on LLM performance could reveal actionable strategies for improvement. Finally, the section likely proposes potential solutions, perhaps focusing on improved training methodologies that incorporate diverse and complex tool usage scenarios, architectural innovations designed for more robust tool integration, and the development of better evaluation metrics specifically tailored for assessing LLMs’ tool-use capabilities.

ToolHop Dataset#

The ToolHop dataset represents a significant contribution to the field of large language model (LLM) evaluation, specifically focusing on multi-hop tool use. Its query-driven construction is a key strength, ensuring that the tools are genuinely interdependent and the queries reflect real-world complexities. This contrasts sharply with prior tool-driven approaches which often resulted in artificial scenarios. The inclusion of 995 multi-hop queries and 3,912 associated tools, along with detailed feedback mechanisms and verifiable answers, provides a robust and reliable benchmark. The diversity of queries across 47 domains, the careful refinement of tool documents and code implementations, and the emphasis on local executability all enhance the dataset’s practical value. ToolHop’s rigorous evaluation across 14 LLMs from five model families exposes the significant challenges remaining in multi-hop tool use, thus enabling more effective development of LLMs.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for multi-hop tool use in large language models (LLMs) should prioritize developing more robust and adaptable tool-use models capable of handling diverse query types and complex tool interactions. Improving LLMs’ understanding of user intent is crucial to avoid errors stemming from incorrect tool selection or parameter usage. Further investigation into optimizing the balance between efficiency and accuracy in parallel tool calls is needed, as current methods show a trade-off between the two. Detailed feedback mechanisms are essential for enhancing LLMs’ ability to learn from mistakes and refine their tool-use strategies. Finally, exploring new evaluation methods beyond simple accuracy metrics to capture nuanced aspects of tool use performance, such as efficiency and reliability, is vital for comprehensive assessment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the three-step query-driven data construction process used to create the ToolHop dataset. First, a multi-hop query is decomposed into individual atomic subqueries. Then, for each atomic subquery, a tool is created, with its corresponding documentation refined to provide detailed descriptions, parameters, and specifications. Finally, code is generated for each tool to ensure local execution and verification of outputs. This iterative approach creates a comprehensive dataset for evaluating large language models’ multi-hop tool-use abilities.

read the caption

Figure 2: An illustration of our proposed query-driven data construction scheme, comprising three key processes: tool creation, document refinement, and code generation. This approach incrementally develops detailed tool document and code implementation for each atomic subquery within a multi-hop query.

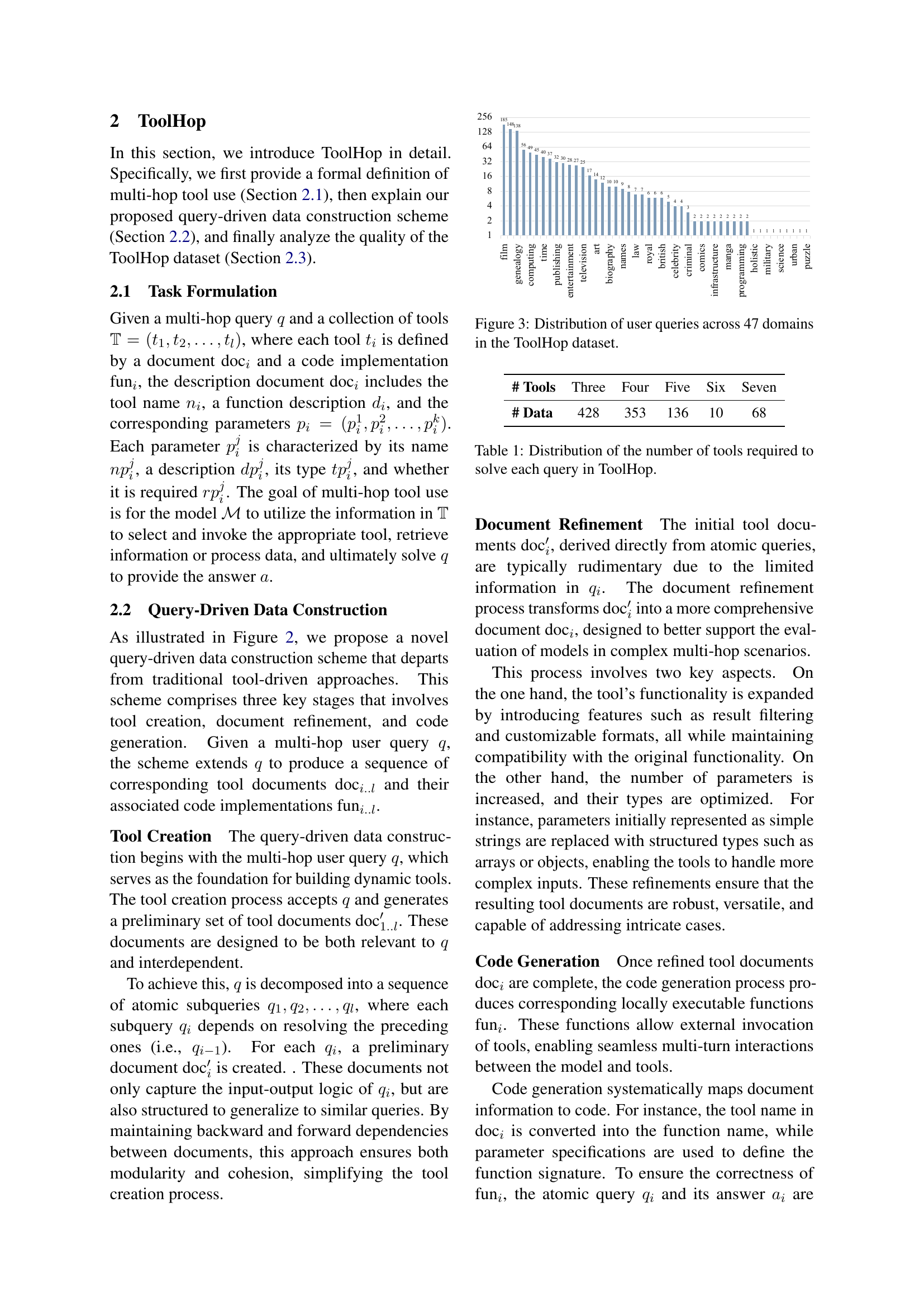

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of 995 user queries from the ToolHop dataset across 47 different domains. The x-axis represents the different domains (e.g., film, genealogy, computing, etc.), and the y-axis shows the number of queries within each domain. The bar chart visually represents the frequency of queries in each domain, giving insights into the diversity of topics covered in the ToolHop dataset. This demonstrates that ToolHop covers a wide range of topics and is not limited to a specific niche.

read the caption

Figure 3: Distribution of user queries across 47 domains in the ToolHop dataset.

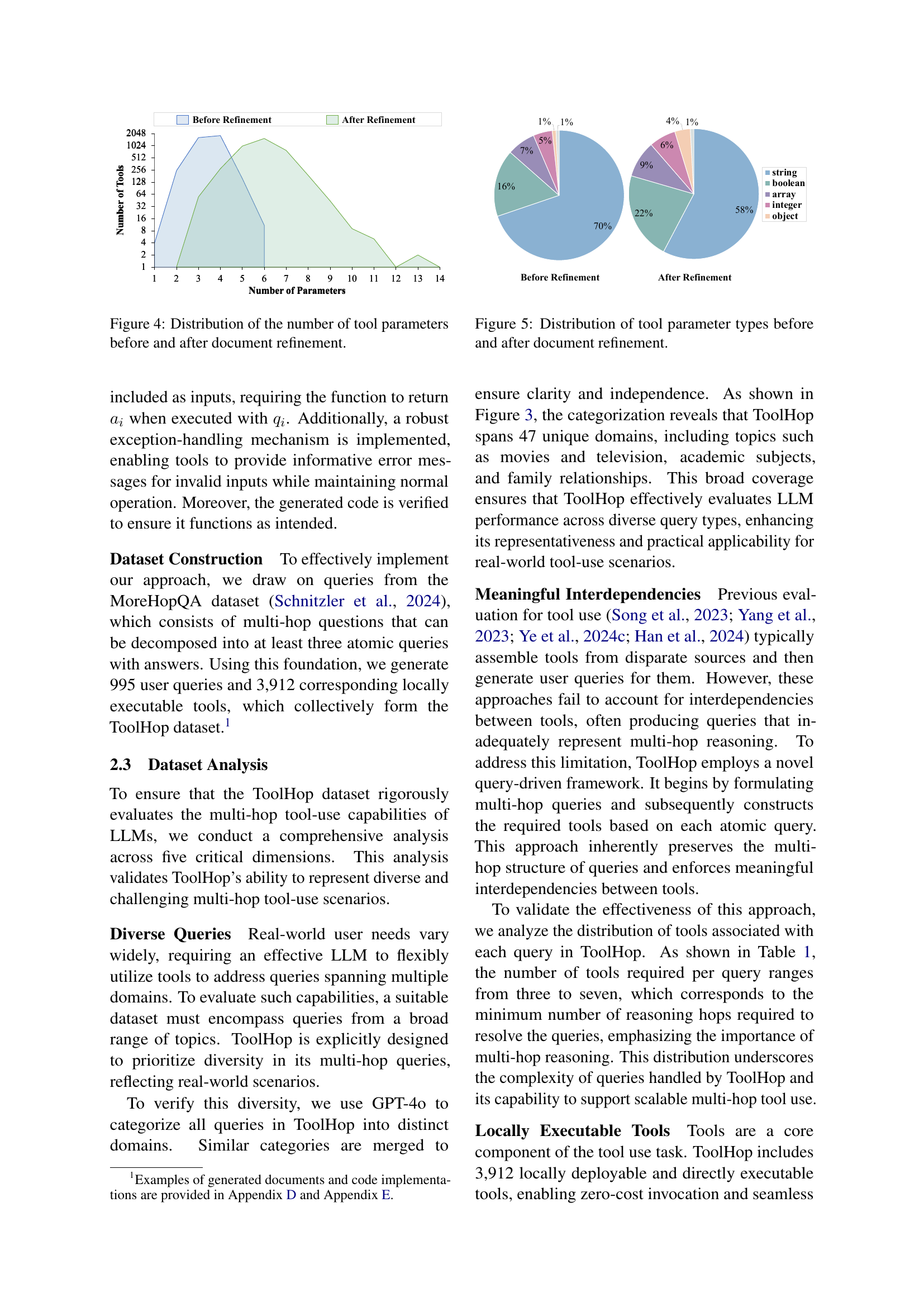

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of the number of tool parameters before and after the document refinement process. The x-axis represents the number of parameters, and the y-axis represents the number of tools. The bars visually compare the number of tools with different parameter counts before and after refinement, highlighting the impact of the refinement process on tool complexity.

read the caption

Figure 4: Distribution of the number of tool parameters before and after document refinement.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the distribution of different parameter types used in tools before and after the document refinement process. Before refinement, a larger proportion of parameters are simple strings. After refinement, there is a shift toward more complex and structured parameter types such as arrays, booleans, integers, and objects, indicating an increase in the complexity and richness of the tools.

read the caption

Figure 5: Distribution of tool parameter types before and after document refinement.

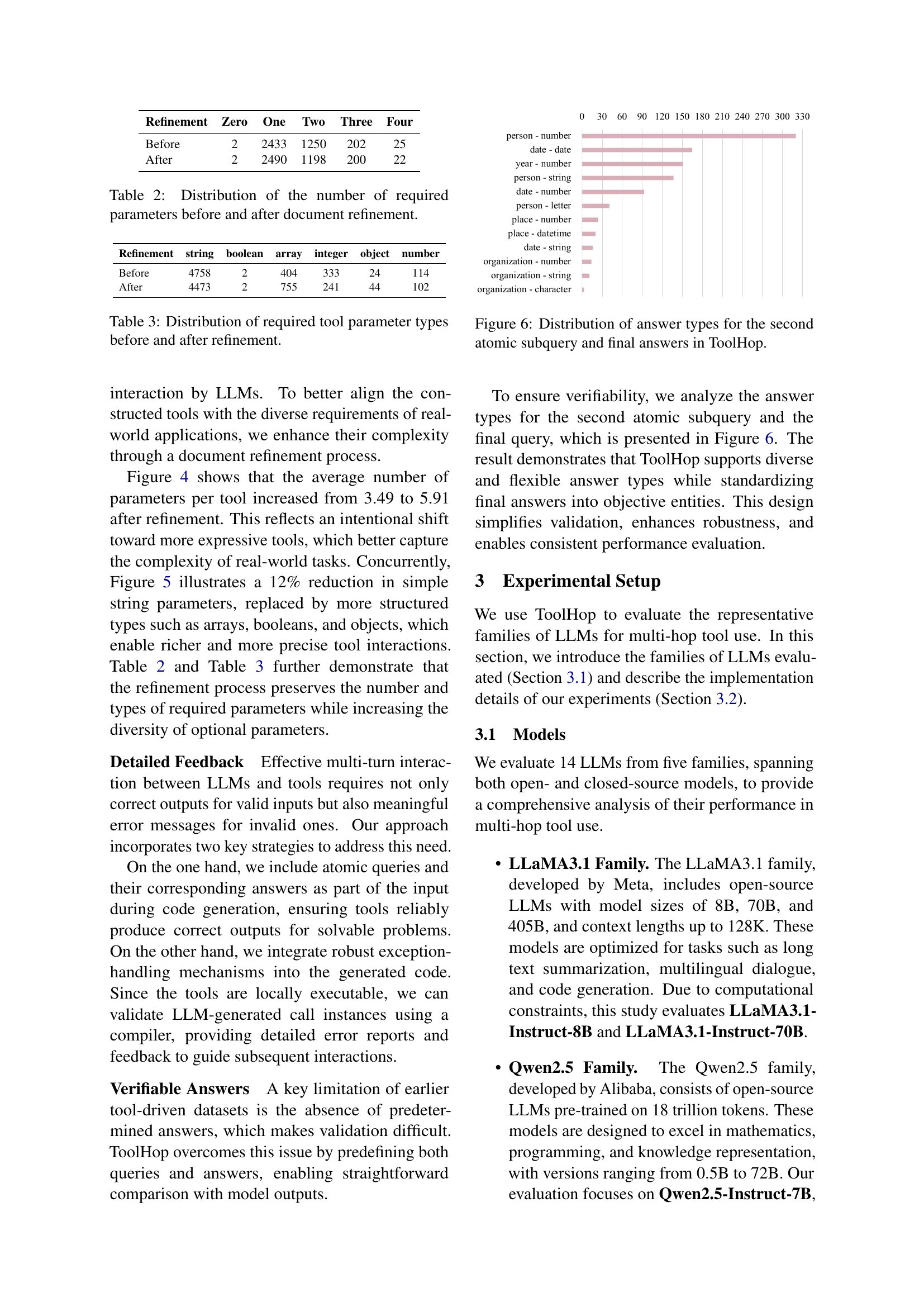

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of different answer types across all queries in the ToolHop dataset. It breaks down the answer types for both the second atomic subquery (an intermediate step in a multi-hop query) and the final answer to the complete multi-hop query. The visualization helps understand the diversity of answer types handled by the dataset and the complexity of reasoning involved in answering the multi-hop queries.

read the caption

Figure 6: Distribution of answer types for the second atomic subquery and final answers in ToolHop.

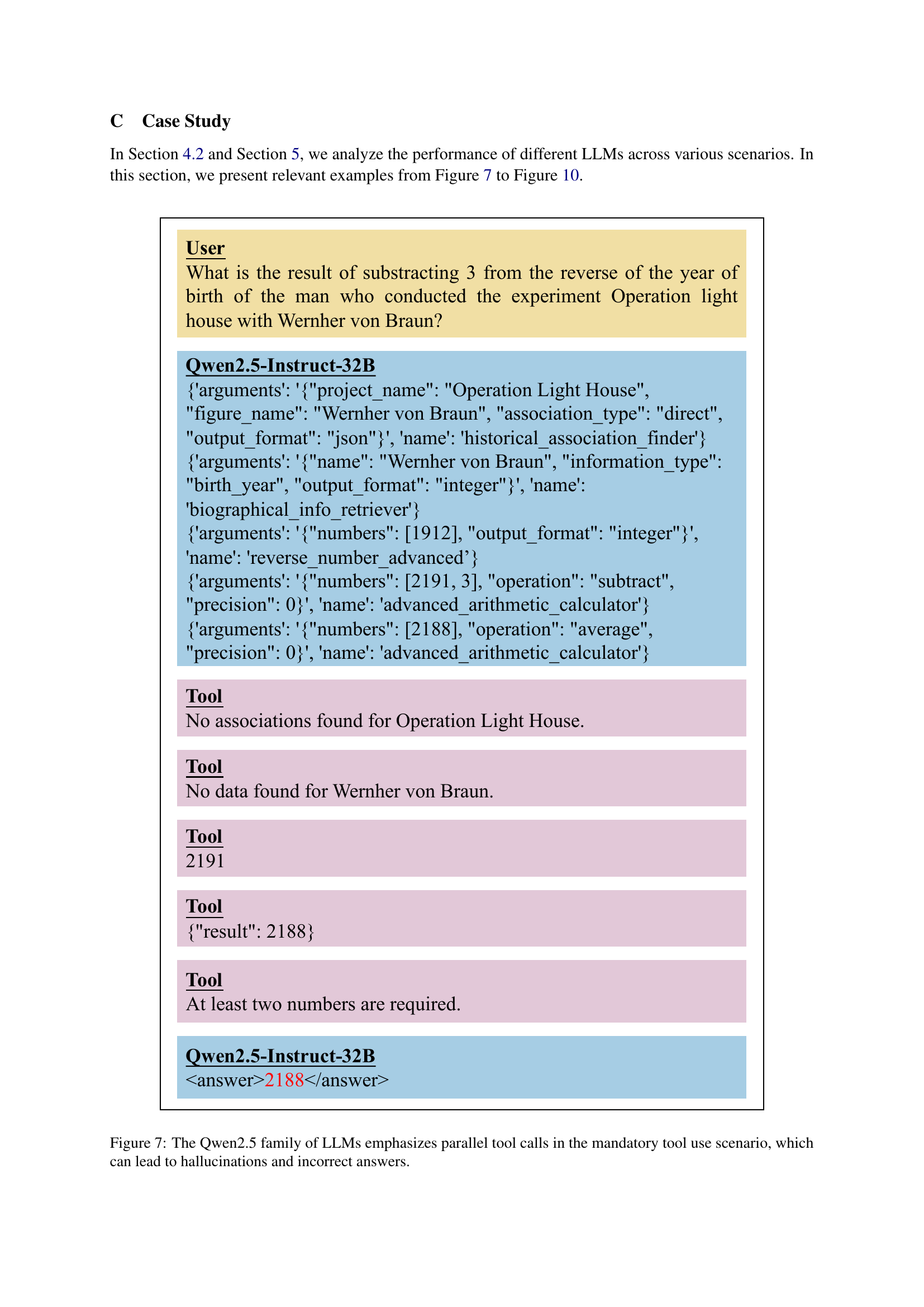

🔼 The figure shows an example of how the Qwen2.5 family of large language models (LLMs) performs in a multi-hop tool use scenario. In this scenario, the models are required to use multiple tools to arrive at the correct answer. However, the Qwen2.5 models make parallel tool calls, which can lead to incorrect results due to hallucinations. The example illustrates how the model’s parallel processing strategy results in errors, despite the potential benefits of efficiency. This highlights the challenges involved in handling complex tool-use scenarios and underscores the limitations of parallel processing in such contexts.

read the caption

Figure 7: The Qwen2.5 family of LLMs emphasizes parallel tool calls in the mandatory tool use scenario, which can lead to hallucinations and incorrect answers.

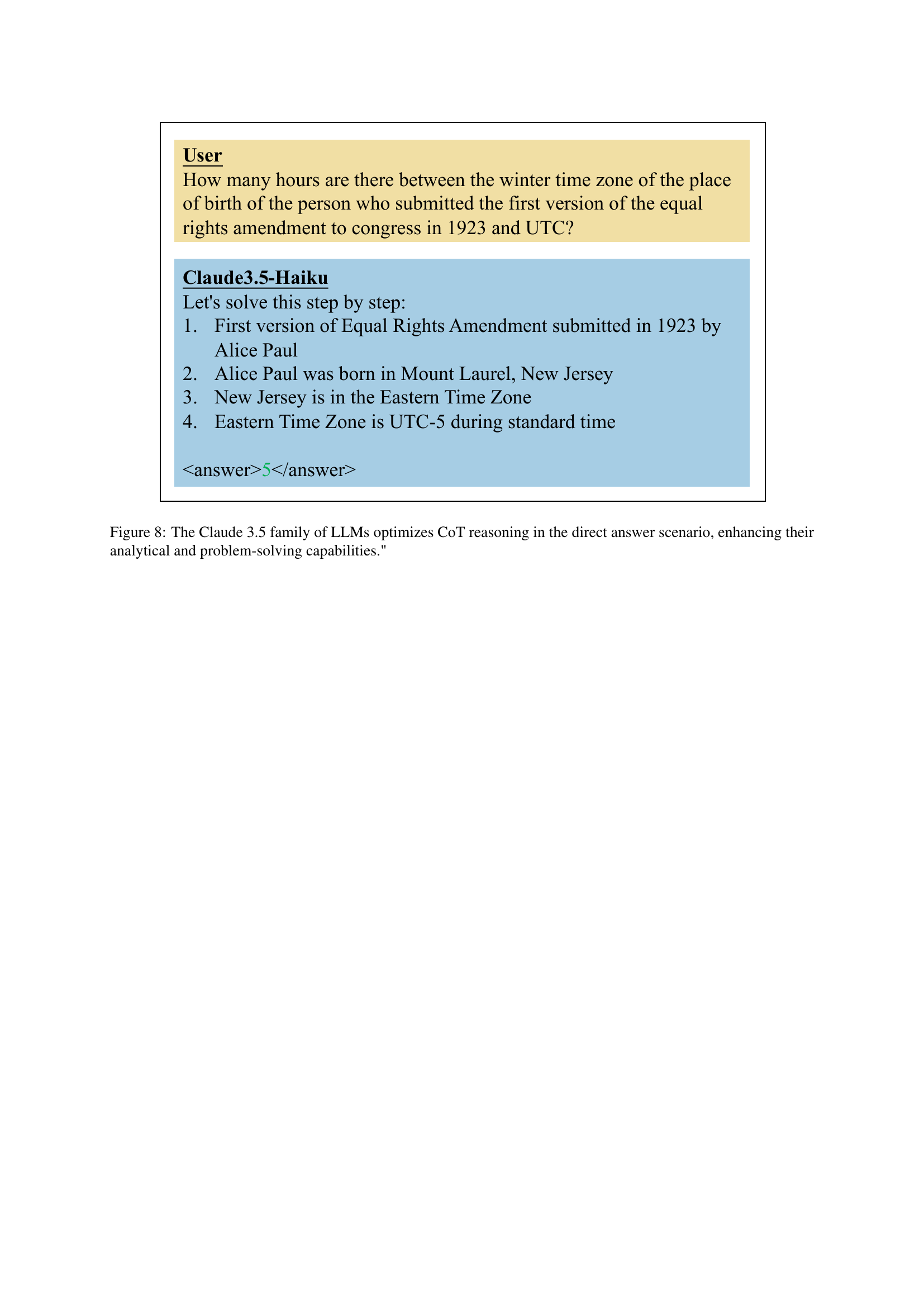

🔼 Figure 8 demonstrates the Claude 3.5 family of LLMs’ superior performance in direct answer scenarios. Unlike other models, Claude 3.5 models naturally employ chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning to break down complex problems into smaller, manageable steps, ultimately leading to more accurate and insightful solutions. This highlights the model’s advanced analytical and problem-solving skills, even without explicit prompting for CoT reasoning. The figure visually represents this process.

read the caption

Figure 8: The Claude 3.5 family of LLMs optimizes CoT reasoning in the direct answer scenario, enhancing their analytical and problem-solving capabilities.'

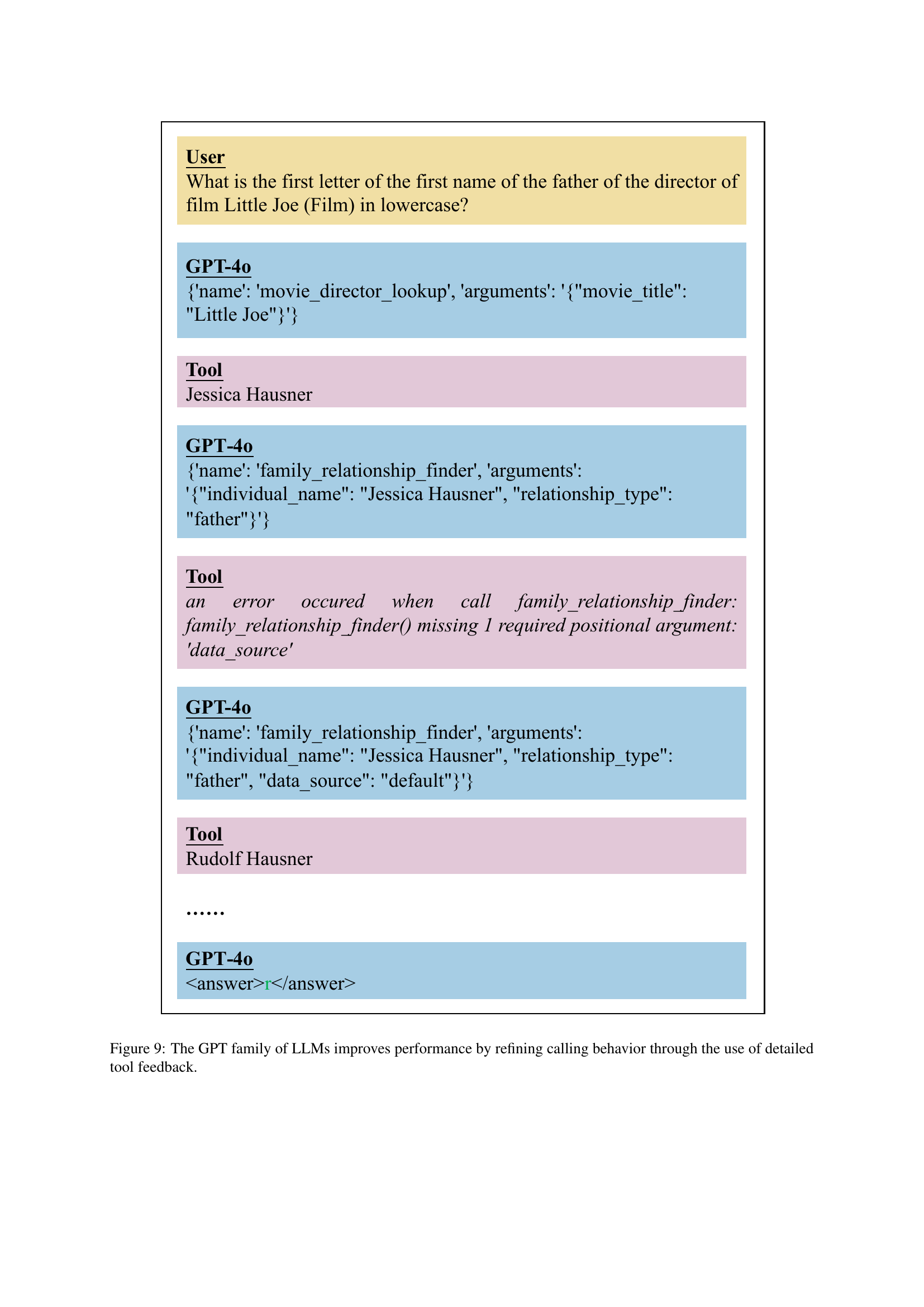

🔼 This figure shows how the GPT family of large language models (LLMs) improves its performance by learning to refine its tool-calling behavior through the use of detailed feedback. The example shows a multi-hop query: ‘What is the first letter of the first name of the father of the director of film Little Joe (Film) in lowercase?’ The model initially makes an error when calling the family_relationship_finder tool because it’s missing a required argument. However, after receiving detailed feedback, the model successfully corrects its error, and produces the correct answer. This demonstrates the model’s ability to learn from detailed feedback and improve its performance in handling tool calls.

read the caption

Figure 9: The GPT family of LLMs improves performance by refining calling behavior through the use of detailed tool feedback.

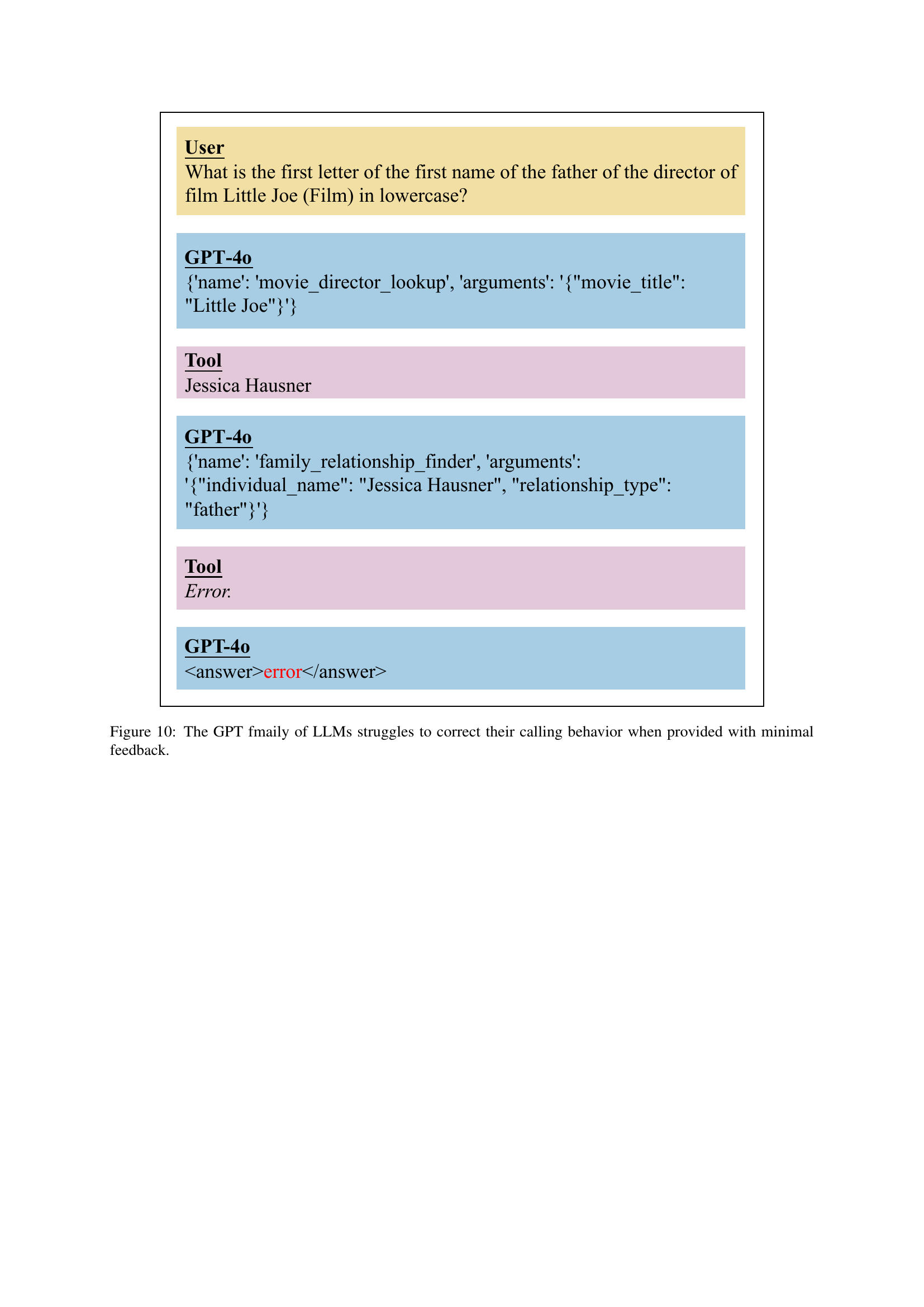

🔼 The figure shows the GPT family of large language models (LLMs) failing to correct their tool-calling behavior when provided with only minimal feedback. This highlights the importance of detailed feedback in enabling effective tool use by LLMs. The example demonstrates a scenario where an LLM requests information about the father of a film director. When the tool fails, returning only a generic error, the LLM is unable to recover and provide the correct response.

read the caption

Figure 10: The GPT fmaily of LLMs struggles to correct their calling behavior when provided with minimal feedback.

More on tables

| Refinement | Zero | One | Two | Three | Four |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 2 | 2433 | 1250 | 202 | 25 |

| After | 2 | 2490 | 1198 | 200 | 22 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the number of required parameters in tool documents before and after a refinement process. The refinement process aims to improve the quality and complexity of the tools. By showing the distribution of the number of required parameters (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, etc.), we can understand how the refinement impacts the complexity of tools used in multi-hop reasoning tasks. The ‘Before’ column shows the parameter count before refinement, and ‘After’ shows the count after refinement. The numbers represent the frequencies of tool documents with that many required parameters.

read the caption

Table 2: Distribution of the number of required parameters before and after document refinement.

| Refinement | string | boolean | array | integer | object | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 4758 | 2 | 404 | 333 | 24 | 114 |

| After | 4473 | 2 | 755 | 241 | 44 | 102 |

🔼 This table shows the number and types of parameters required by the tools in the ToolHop dataset before and after the document refinement process. It illustrates how the refinement process increased the complexity of the tools by adding more parameters and using more diverse parameter types (e.g., changing simple strings to arrays or objects). The table helps to demonstrate the impact of the refinement process on the overall complexity and versatility of the tools.

read the caption

Table 3: Distribution of required tool parameter types before and after refinement.

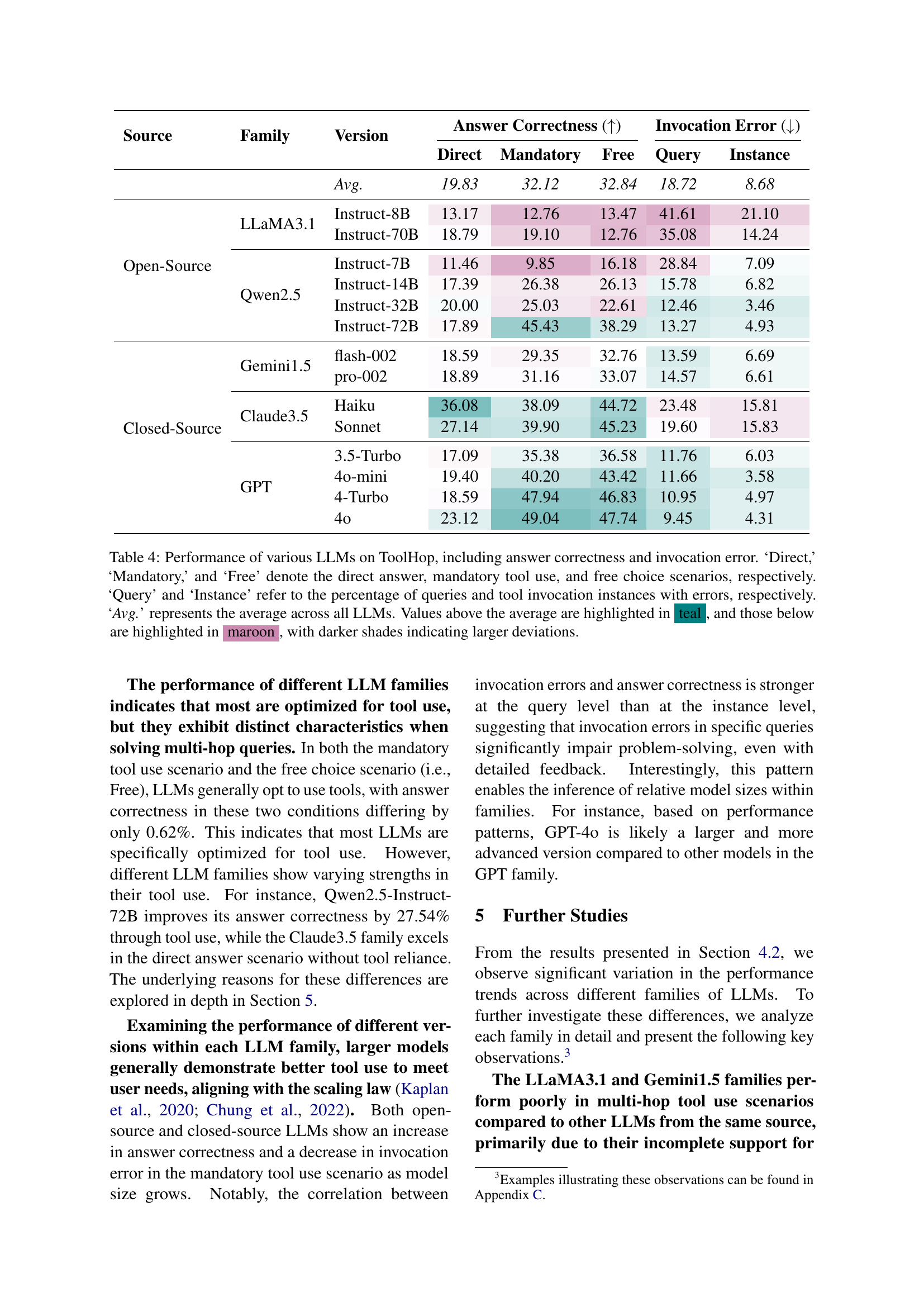

| Source | Family | Version | Direct | Mandatory | Free | Query | Instance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | 19.83 | 32.12 | 32.84 | 18.72 | 8.68 | |||

| Open-Source | LLaMA3.1 | Instruct-8B | 13.17 | 12.76 | 13.47 | 41.61 | 21.10 | |

| Instruct-70B | 18.79 | 19.10 | 12.76 | 35.08 | 14.24 | |||

| Qwen2.5 | Instruct-7B | 11.46 | 9.85 | 16.18 | 28.84 | 7.09 | ||

| Instruct-14B | 17.39 | 26.38 | 26.13 | 15.78 | 6.82 | |||

| Instruct-32B | 20.00 | 25.03 | 22.61 | 12.46 | 3.46 | |||

| Instruct-72B | 17.89 | 45.43 | 38.29 | 13.27 | 4.93 | |||

| Closed-Source | Gemini1.5 | flash-002 | 18.59 | 29.35 | 32.76 | 13.59 | 6.69 | |

| pro-002 | 18.89 | 31.16 | 33.07 | 14.57 | 6.61 | |||

| Claude3.5 | Haiku | 36.08 | 38.09 | 44.72 | 23.48 | 15.81 | ||

| Sonnet | 27.14 | 39.90 | 45.23 | 19.60 | 15.83 | |||

| GPT | 3.5-Turbo | 17.09 | 35.38 | 36.58 | 11.76 | 6.03 | ||

| 4o-mini | 19.40 | 40.20 | 43.42 | 11.66 | 3.58 | |||

| 4-Turbo | 18.59 | 47.94 | 46.83 | 10.95 | 4.97 | |||

| 4o | 23.12 | 49.04 | 47.74 | 9.45 | 4.31 |

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive evaluation of 14 Large Language Models (LLMs) across five families on the ToolHop benchmark. It compares their performance in three scenarios: solving queries directly (Direct), mandatorily using tools (Mandatory), and freely choosing to use tools (Free). The results show answer correctness rates and invocation error rates (both at the query and instance level). Color-coding highlights performances above and below the average, with darker shades indicating larger deviations from the average. This allows for detailed analysis of model performance across different approaches to tool usage, revealing strengths and weaknesses of various LLM families.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance of various LLMs on ToolHop, including answer correctness and invocation error. ‘Direct,’ ‘Mandatory,’ and ‘Free’ denote the direct answer, mandatory tool use, and free choice scenarios, respectively. ‘Query’ and ‘Instance’ refer to the percentage of queries and tool invocation instances with errors, respectively. ‘Avg.’ represents the average across all LLMs. Values above the average are highlighted in teal, and those below are highlighted in maroon, with darker shades indicating larger deviations.

| Version | w/ Feedback | w/o Feedback | ΔC→I | ΔI→C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5-Turbo | 36.75 | 21.37 | 20.51 | 5.13 |

| 4o-mini | 38.53 | 11.93 | 29.36 | 2.75 |

| 4-Turbo | 29.31 | 12.07 | 17.24 | 0.00 |

| 4o | 47.87 | 24.47 | 25.53 | 2.13 |

🔼 This table presents the impact of detailed feedback on the performance of GPT family models when dealing with queries that resulted in tool invocation errors. It shows the answer correctness when detailed feedback is provided and when only minimal error feedback is offered. The changes in accuracy are also presented, showing how many initially correct answers became incorrect (ΔC→I) and how many initially incorrect answers became correct (ΔI→C) when the feedback was changed from detailed to minimal.

read the caption

Table 5: Answer correctness of the GPT family of models in queries containing invocation error. ‘w/ Feedback’ and ‘w/o Feedback’ represent cases where detailed feedback or only simple error reporting is provided, respectively. ‘𝚫𝐂→𝐈subscript𝚫→𝐂𝐈\mathbf{\Delta_{C\to I}}bold_Δ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT bold_C → bold_I end_POSTSUBSCRIPT’ denotes the proportion of correct answers that become incorrect, while ‘𝚫𝐈→𝐂subscript𝚫→𝐈𝐂\mathbf{\Delta_{I\to C}}bold_Δ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT bold_I → bold_C end_POSTSUBSCRIPT’ represents the proportion of incorrect answers that become correct, when transitioning from detailed feedback to simple error reporting.

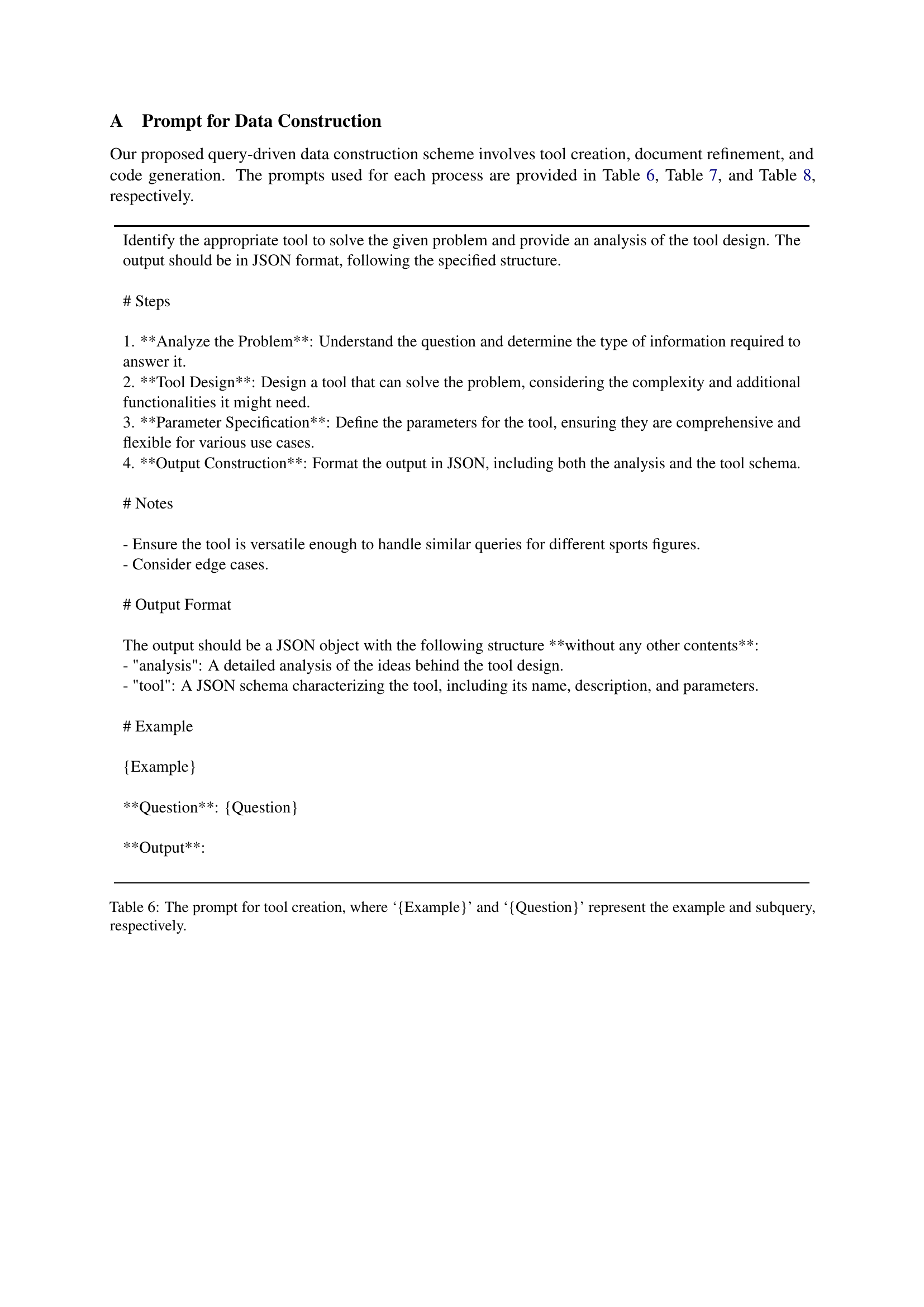

| Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Analyze the Problem | Understand the question and determine the type of information required to answer it. |

| 2. Tool Design | Design a tool that can solve the problem, considering the complexity and additional functionalities it might need. |

| 3. Parameter Specification | Define the parameters for the tool, ensuring they are comprehensive and flexible for various use cases. |

| 4. Output Construction | Format the output in JSON, including both the analysis and the tool schema. |

| Notes | - Ensure the tool is versatile enough to handle similar queries for different sports figures. - Consider edge cases. |

| Output Format | The output should be a JSON object with the following structure without any other contents: - “analysis”: A detailed analysis of the ideas behind the tool design. - “tool”: A JSON schema characterizing the tool, including its name, description, and parameters. |

🔼 This table details the prompt used for the tool creation stage in the ToolHop dataset construction. The prompt instructs the model to analyze a given problem, design a tool to solve it, specify the tool’s parameters, and format the output as a JSON object containing both the analysis and the tool schema. The ‘{Example}’ and ‘{Question}’ placeholders within the prompt indicate that example data and a subquery will be provided to guide the model’s response.

read the caption

Table 6: The prompt for tool creation, where ‘{Example}’ and ‘{Question}’ represent the example and subquery, respectively.

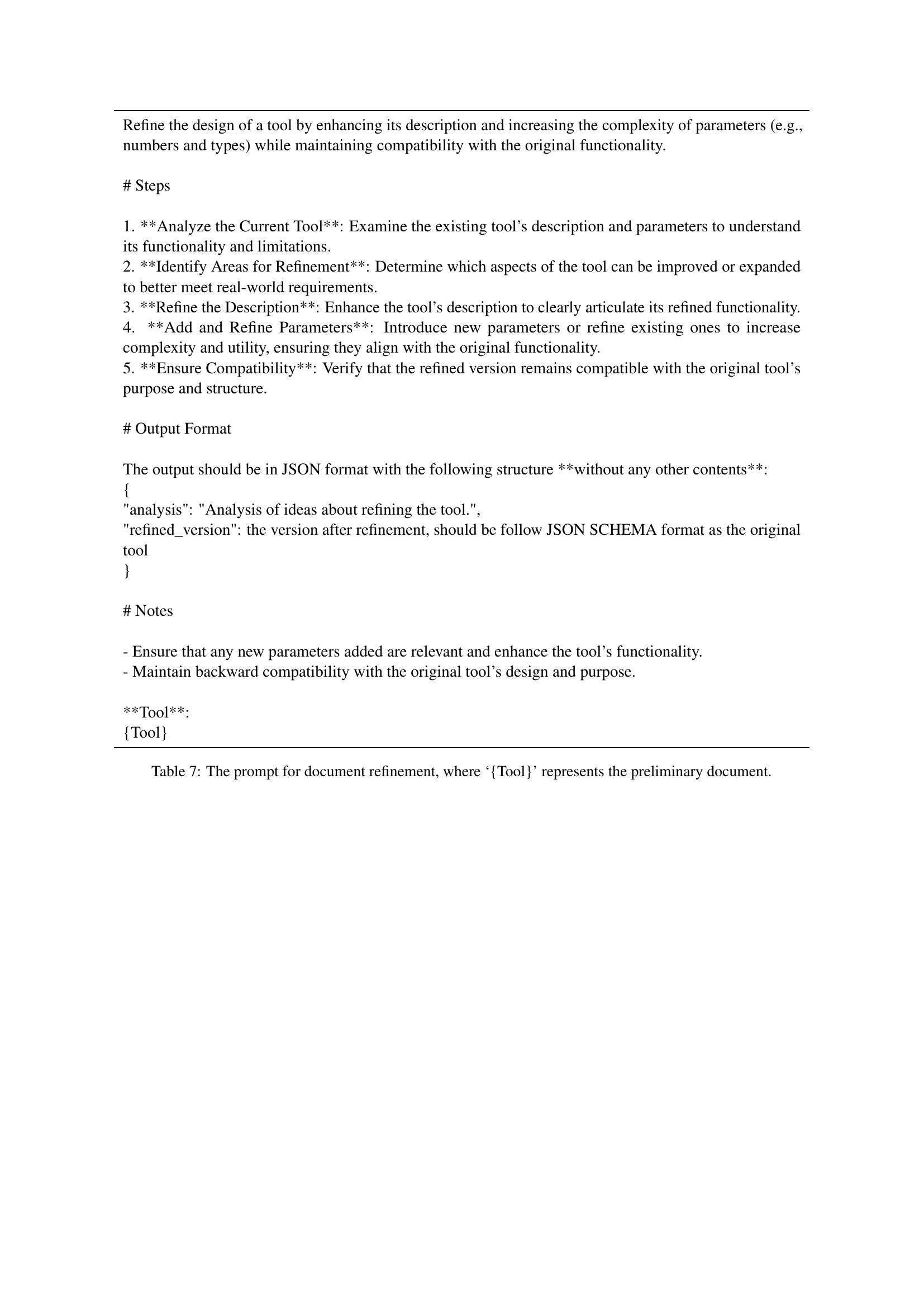

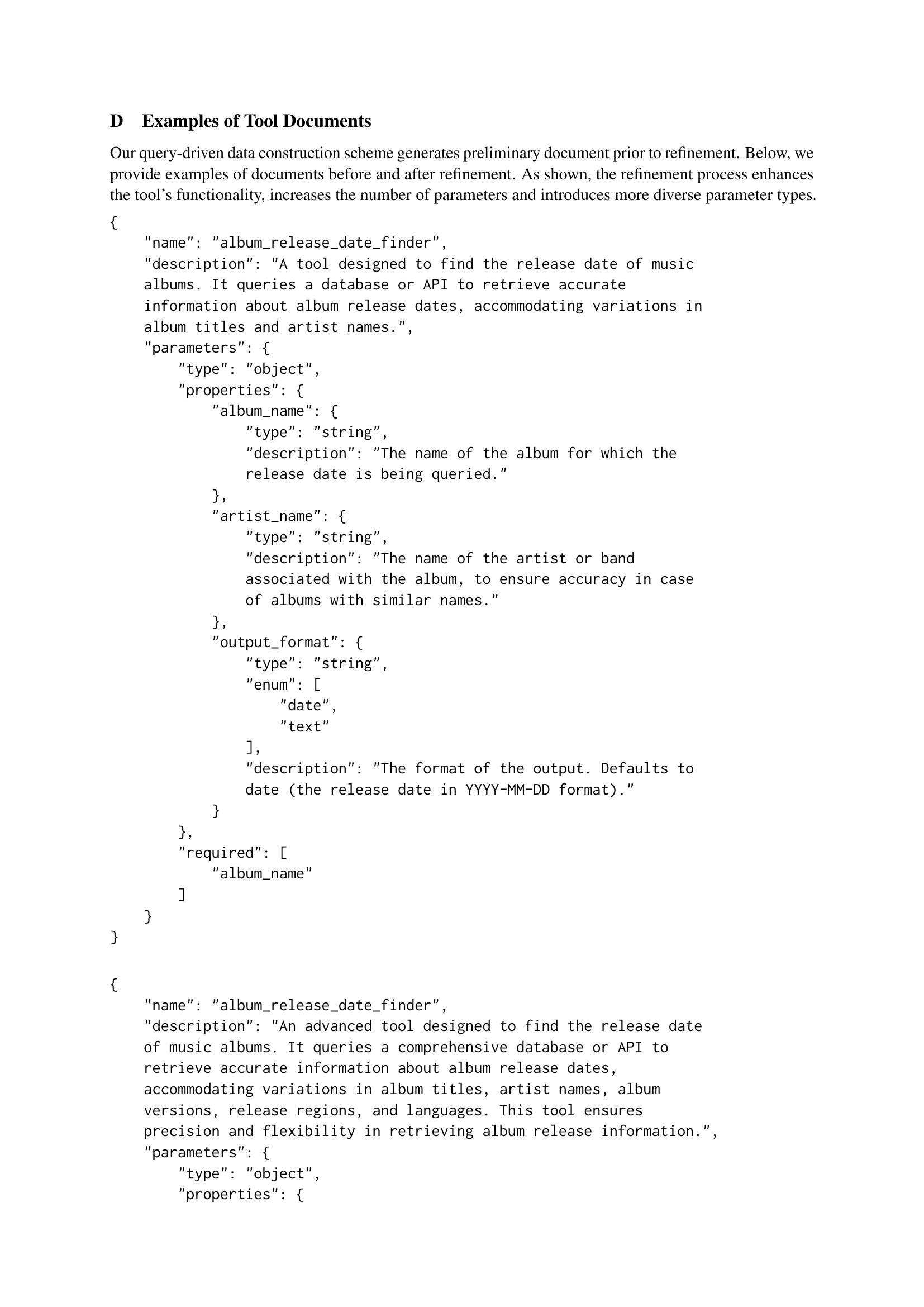

🔼 This table describes the prompt used in the query-driven data construction process for refining the preliminary tool documents. The prompt guides the process of enhancing the tool’s description, adding or refining parameters to increase complexity and utility, while maintaining compatibility with the original tool’s functionality. It outlines steps for analyzing the existing tool, identifying areas for improvement, refining the description, adjusting parameters, and verifying compatibility.

read the caption

Table 7: The prompt for document refinement, where ‘{Tool}’ represents the preliminary document.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. | Understand the Tool Document: Review the tool document to identify the function name, parameter names, and types. |

| 2. | Analyze the Question and Answer: Determine how the function should be used to answer the question. |

| 3. | Implement the Function: - Use the tool name as the function name. - Define parameters exactly as specified in the tool document. - Implement the function logic to produce the correct answer for the given question. - Simulate additional return values as specified in the tool document. |

| 4. | Error Handling: Develop a robust error handling mechanism to return valid error messages for incorrect inputs or other issues. |

| Note | - Ensure parameter types and names match exactly with the tool document. - Simulate additional return values as needed based on the tool’s documentation. - Implement comprehensive error handling to cover potential issues. |

| Output format | Output the result in JSON format with the following structure without any other contents: { |

| “analysis”: “Detailed analysis of how the function was designed, including reasoning for parameter choices and exception handling.”, | |

| “function”: “The specific function design, including code and comments explaining each part.” | |

| } | |

| Tool Document | {document} |

| Question | {question} |

| Answer | {answer} |

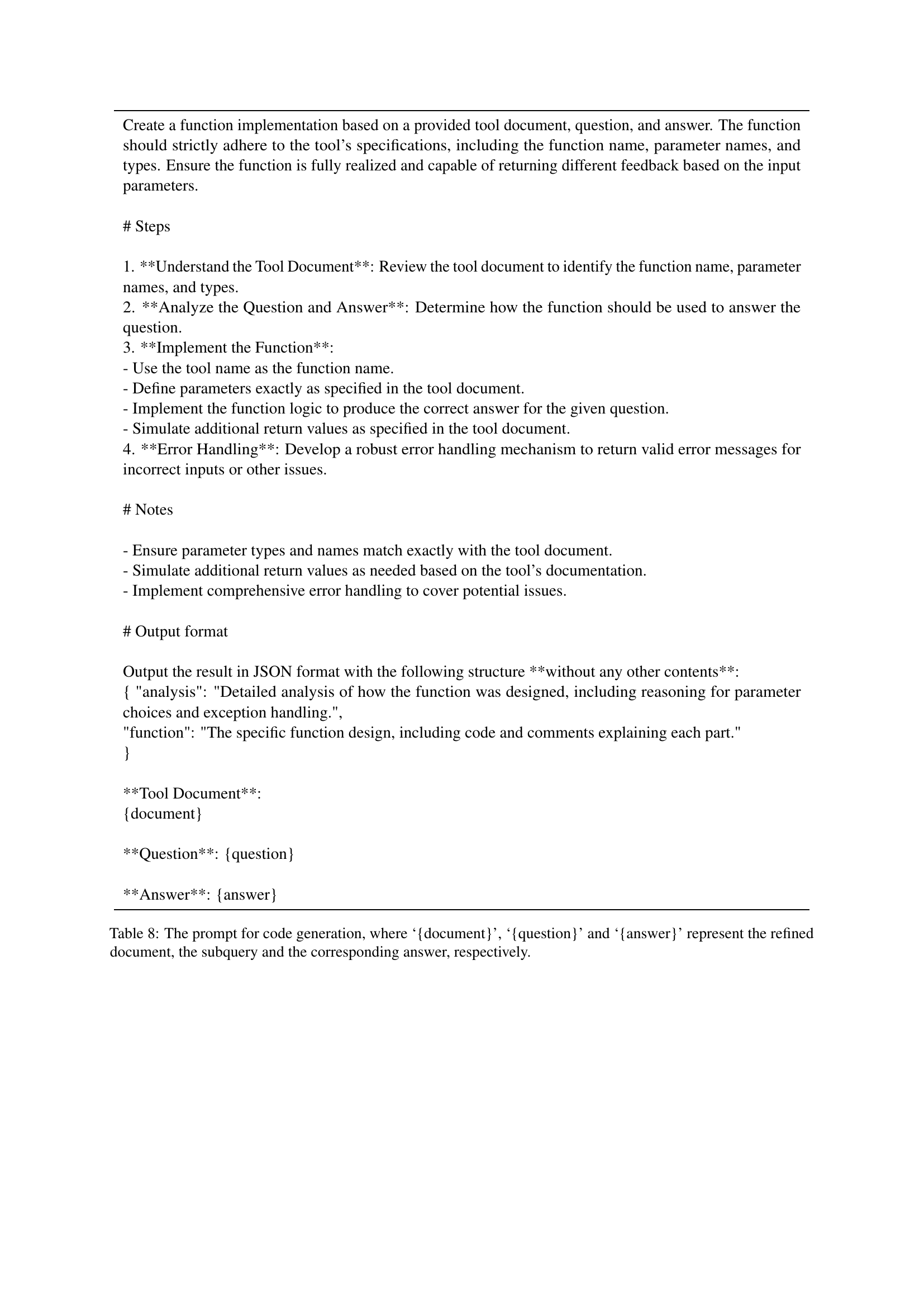

🔼 Table 8 details the prompt used to generate code based on a refined tool document, a specific subquery, and its corresponding answer. This prompt guides the process of creating functional code for the tools used in the ToolHop multi-hop query benchmark, ensuring the code accurately reflects the tool’s specifications and handles various inputs appropriately. The prompt is structured to ensure that the generated code adheres strictly to the tool’s specifications, including the function name, parameter names, types, and error handling mechanisms, enabling accurate evaluation of LLM capabilities in tool use.

read the caption

Table 8: The prompt for code generation, where ‘{document}’, ‘{question}’ and ‘{answer}’ represent the refined document, the subquery and the corresponding answer, respectively.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Analyze the Sentence | Break down the sentence to understand its components and context. |

| 2. Identify Key Elements | Look for specific terms or phrases that indicate the subject matter, such as names, dates, or specific topics. |

| 3. Determine the Domain | Based on the analysis, select the most appropriate domain that encapsulates the main focus of the sentence. |

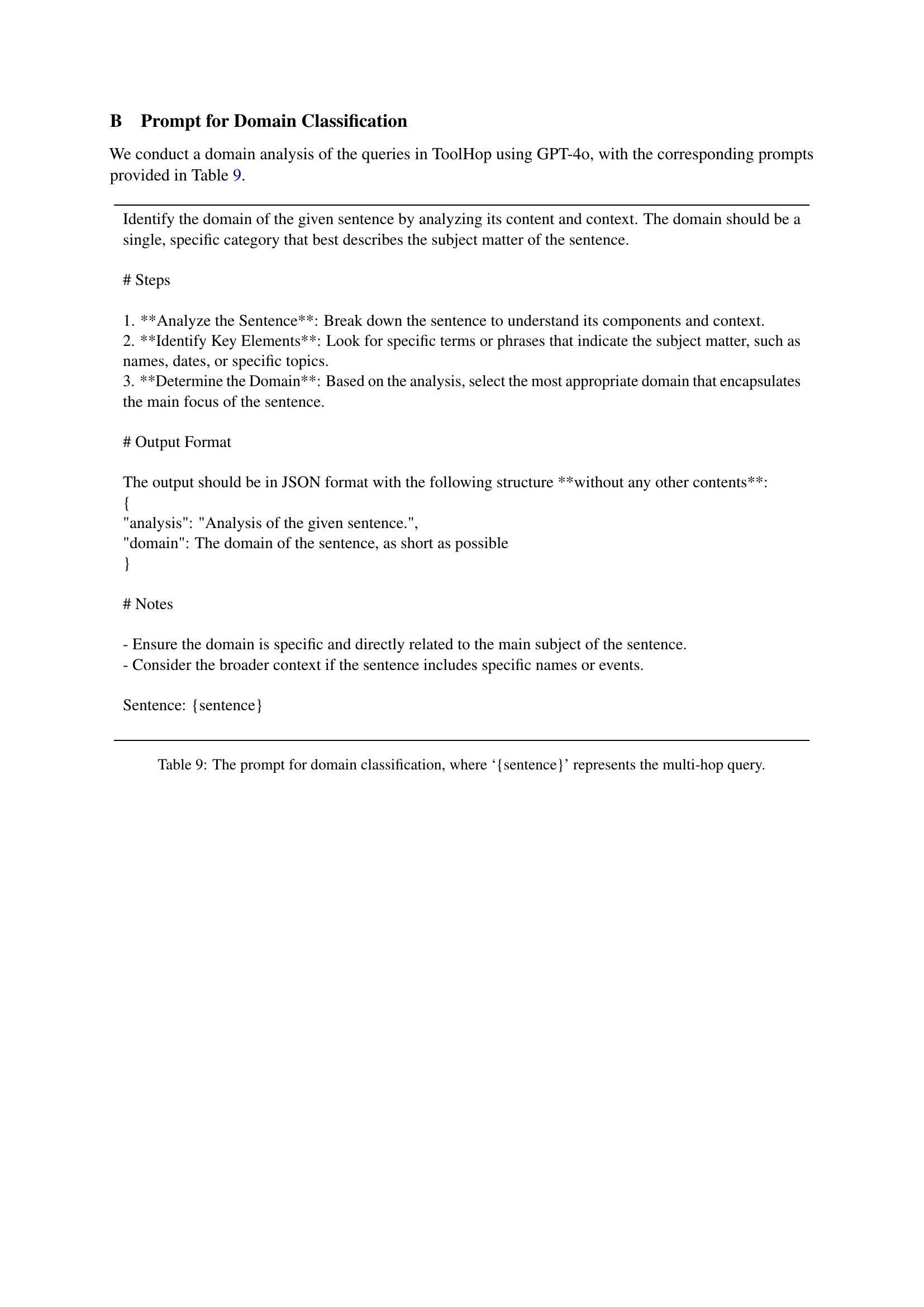

🔼 This table details the prompt used for domain classification within the ToolHop dataset. The prompt instructs GPT-40 to analyze a given sentence (the multi-hop query), identify key elements and determine the most appropriate domain to categorize the query’s subject. The expected output is a JSON object with ‘analysis’ and ‘domain’ fields.

read the caption

Table 9: The prompt for domain classification, where ‘{sentence}’ represents the multi-hop query.

Full paper#