↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current video understanding benchmarks overlook fine-grained motion comprehension, a crucial aspect for many real-world applications. This limitation stems from the difficulty in processing high-frame-rate videos within the limited context length constraints of large language models (LLMs). To address these issues, the paper introduces MotionBench, a comprehensive benchmark to evaluate fine-grained motion understanding in videos.

MotionBench uses diverse video sources and question types focusing on motion-level perception, revealing significant shortcomings in existing video models. The authors then propose a novel Through-Encoder (TE) Fusion method which enhances video feature representation by applying deep fusion throughout the visual encoder, particularly beneficial under high compression ratios. Experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of TE Fusion, achieving state-of-the-art results on MotionBench and showcasing its superior performance compared to other compression techniques across multiple benchmarks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in video understanding and vision-language models. MotionBench provides a much-needed benchmark for evaluating fine-grained motion comprehension, a previously under-explored area. The proposed TE Fusion method offers a novel approach to video feature compression, improving model performance and prompting further research into efficient architectures for video understanding. Its findings challenge the field to create models capable of truly understanding nuanced video content.

Visual Insights#

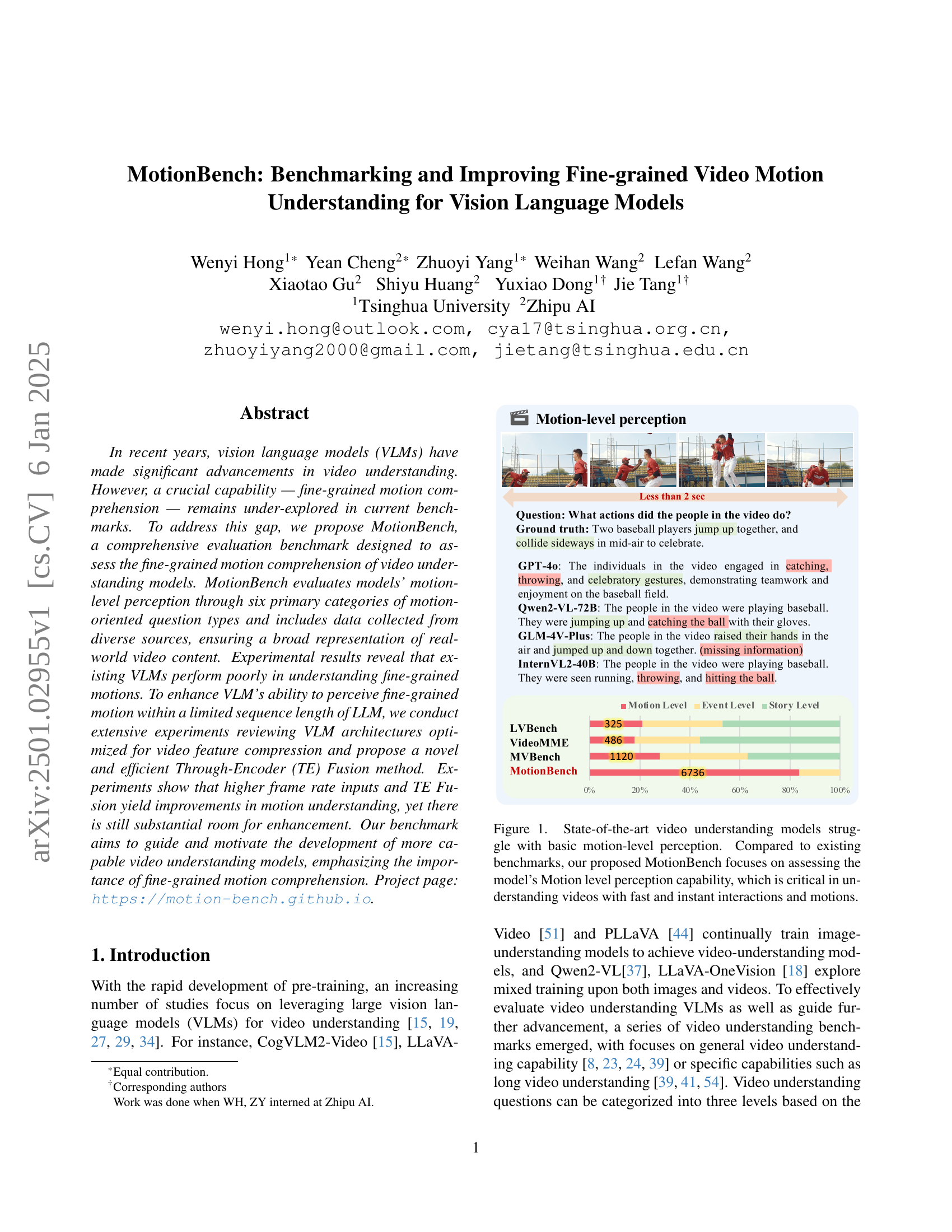

🔼 The figure illustrates that state-of-the-art video understanding models struggle with basic motion-level perception. It compares the performance of several models (LVBench, VideoMME, MVBench, and the proposed MotionBench) on motion-level perception tasks. MotionBench outperforms other benchmarks because it specifically focuses on evaluating the fine-grained motion understanding capability, crucial for comprehending videos with rapid and immediate interactions and movements.

read the caption

Figure 1: State-of-the-art video understanding models struggle with basic motion-level perception. Compared to existing benchmarks, our proposed MotionBench focuses on assessing the model’s Motion level perception capability, which is critical in understanding videos with fast and instant interactions and motions.

| Benchmarks | #Videos | #QAs | Perception Level | Data source | Dataset Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVBench [23] | 4,000 | 4,000 | general, motion<30% | existing datasets | general |

| TempCompass [28] | 410 | 1,580 | general, motion<20% | ShutterStock | temporal concept |

| VideoMME [8] | 900 | 2,700 | general, motion<20% | Youtube | general |

| AutoEval-Video [4] | 327 | 327 | event level | Youtube | open-ended QA |

| EgoSchema [31] | 5,031 | 5031 | event level | ego-centric video | ego-centric |

| LVBench [39] | 103 | 1,549 | event & story level | Youtube | long video |

| LongVideoBench [41] | 3,763 | 6,678 | event & story level | web channels | long videos |

| MovieChat-1K [35] | 130 | 1,950 | story level | movies | movie |

| Short Film Dataset [9] | 1,078 | 4,885 | story level | short films | story-level |

| MotionBench | 5,385 | 8,052 | motion level | web videos, movies, synthetic videos, datasets | motion perception |

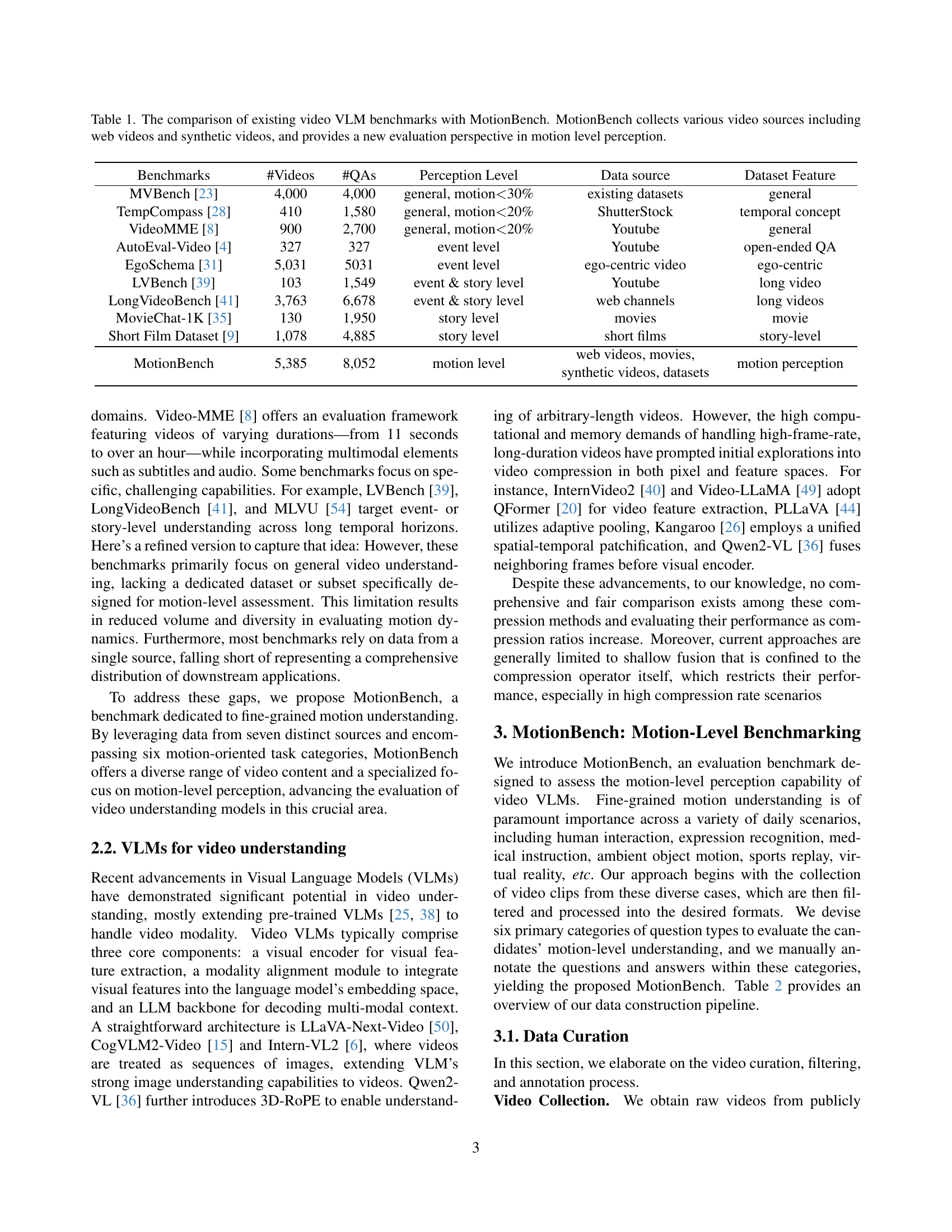

🔼 This table compares MotionBench with other existing video VLM benchmarks. The comparison includes the number of videos and questions/answers (QAs) in each benchmark. It also highlights the level of perception each benchmark focuses on (general, motion, event, or story level), the data sources used, and the types of features present in the datasets (general, temporal concepts, etc.). MotionBench is distinct in its focus on motion-level perception, using a diverse range of video sources and providing a more granular evaluation of fine-grained motion understanding than other benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 1: The comparison of existing video VLM benchmarks with MotionBench. MotionBench collects various video sources including web videos and synthetic videos, and provides a new evaluation perspective in motion level perception.

In-depth insights#

MotionBench#

MotionBench, as described in the research paper, is a novel benchmark designed for evaluating the fine-grained motion understanding capabilities of Vision Language Models (VLMs). Its core contribution lies in addressing the gap in existing benchmarks that lack a dedicated focus on motion-level perception. MotionBench achieves this through a comprehensive evaluation framework encompassing diverse video sources and six key categories of motion-oriented question types. The benchmark reveals the significant deficiency in existing VLMs’ ability to accurately understand fine-grained motions, highlighting a critical area for future VLM development. Furthermore, MotionBench provides valuable insights into the challenges presented by high frame rates and the computational cost of processing long sequences of video frames. The introduction of a Through-Encoder Fusion (TE) method aims to mitigate these challenges, demonstrating improvements in motion understanding. Overall, MotionBench serves as a powerful tool for driving research and development of more capable video understanding models.

Fine-grained Motion#

Fine-grained motion analysis in video understanding is a challenging yet crucial area. It demands high frame rates for capturing subtle movements, but processing long sequences at such rates is computationally expensive. Existing benchmarks often overlook this level of detail, focusing instead on event or story-level understanding. This gap highlights a critical need for more sophisticated models capable of robust fine-grained motion comprehension. A key challenge lies in the development of efficient video feature compression techniques that preserve crucial motion information without excessive loss. Architectural innovations, such as through-encoder fusion, show promise in improving the handling of high frame rate inputs and enhancing the understanding of subtle motions. Future advancements in this area could significantly impact video understanding applications requiring precise motion analysis, such as anomaly detection and detailed action recognition.

TE Fusion#

The proposed Through-Encoder Fusion (TE Fusion) method offers a novel approach to video feature compression for Vision Language Models (VLMs). Instead of performing fusion before or after the visual encoder (as in Pre-Encoder and Post-Encoder fusion methods), TE Fusion integrates temporal fusion directly within the visual encoder. This deep fusion process, using group-level self-attention across adjacent frames before compression, aims to capture higher-level temporal redundancies that shallow fusion methods miss. This leads to improved performance, particularly at high compression ratios, where TE Fusion significantly outperforms existing methods. The key advantage lies in its ability to leverage the visual encoder’s capacity for understanding contextual temporal relationships, leading to more robust and accurate motion understanding, even with limited input frames. It addresses the inherent trade-off between high frame-rate requirements for fine-grained motion analysis and the computational constraints of VLMs, thus paving a new way for efficient video understanding.

Benchmarking VLMs#

Benchmarking Vision-Language Models (VLMs) for video understanding is crucial for evaluating their progress and identifying areas needing improvement. Comprehensive benchmarks should cover various aspects, including motion perception at different granularities (fine-grained, event-level, story-level), handling of varying video lengths, and diverse video content types. A good benchmark must address the limitations of existing datasets by including more nuanced annotations and a broader range of video sources, ensuring a robust evaluation of VLMs across diverse scenarios. High-frame-rate videos, while important for accurate fine-grained motion analysis, present a significant computational challenge, and benchmarks should consider this trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. Ultimately, effective benchmarking should help guide the development of VLMs that are more robust, accurate and efficient in comprehending complex video data.

Future Directions#

Future research should focus on improving the robustness of video understanding models to noisy and complex real-world data, addressing limitations in handling diverse lighting conditions, occlusions, and variations in camera viewpoints. A key area is developing more effective methods for fine-grained motion representation and compression, which could involve exploring novel neural architectures or leveraging advances in signal processing. Furthermore, enhanced benchmarks are needed to accurately measure the capabilities of video understanding models, particularly in tasks requiring nuanced motion comprehension. This involves creating more diverse and challenging datasets, including scenarios with complex interactions and multi-modal inputs (audio, text, etc.). Finally, future work must investigate the ethical implications of video understanding, particularly in contexts where privacy and fairness are paramount. Addressing these future directions will lead to significant advancements in fine-grained video motion analysis, paving the way for a broader range of innovative applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

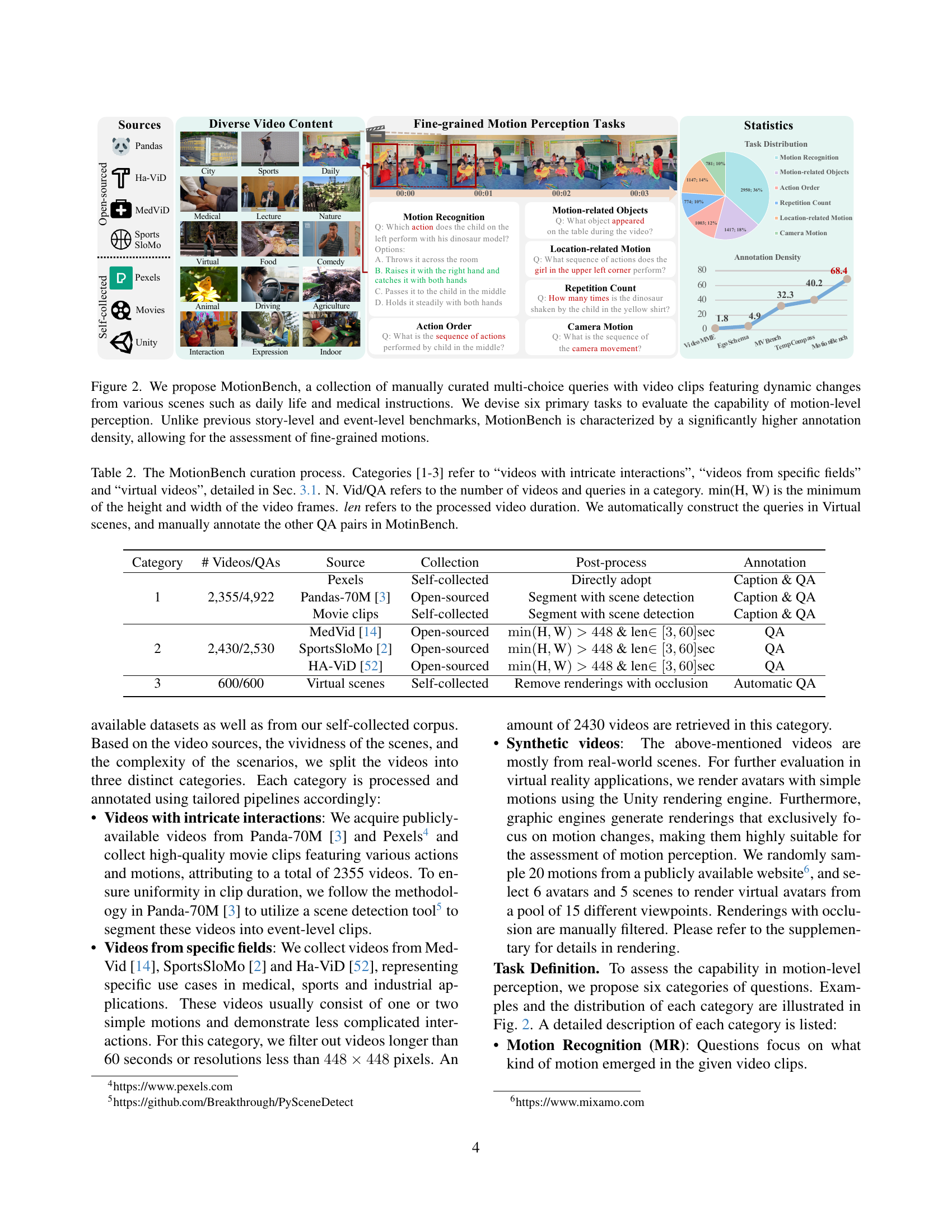

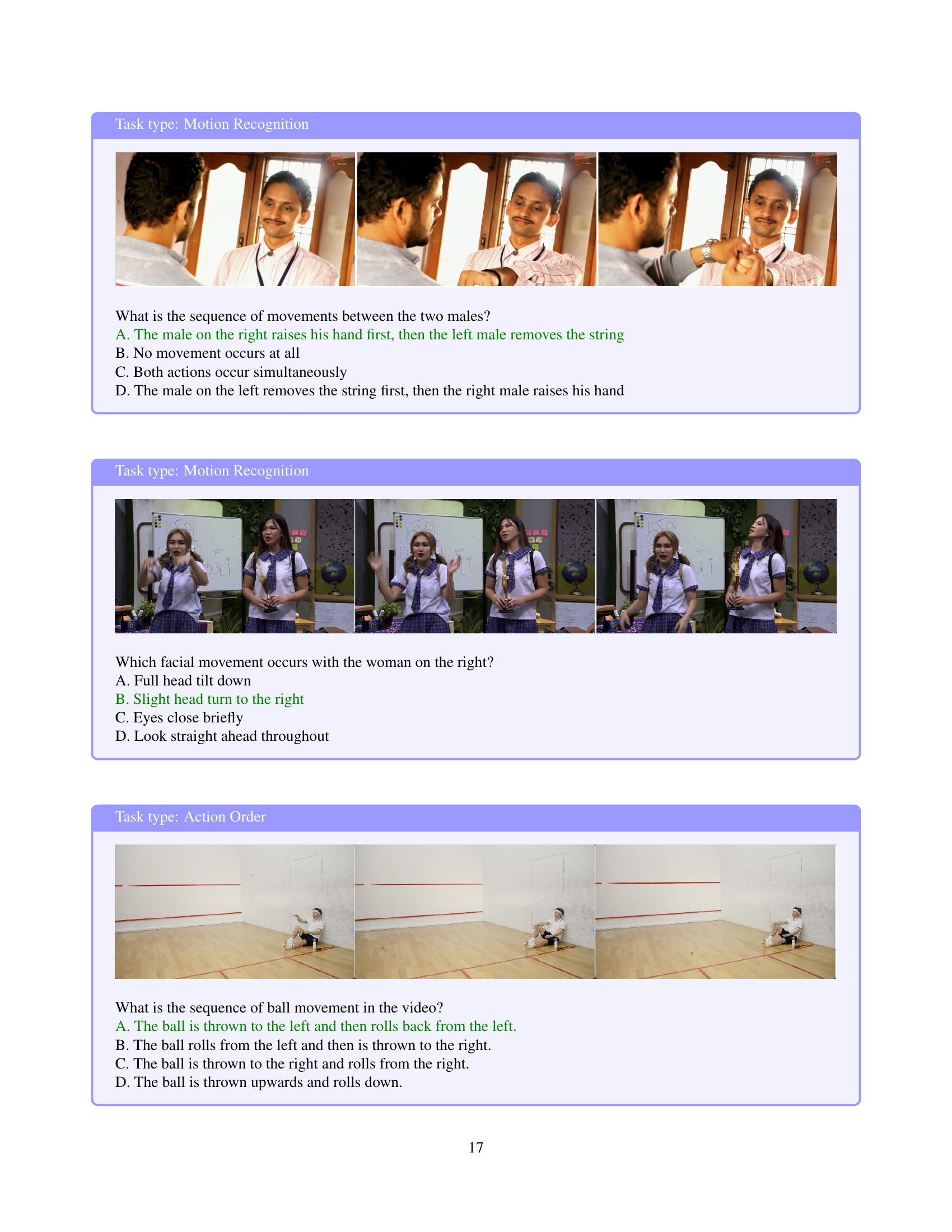

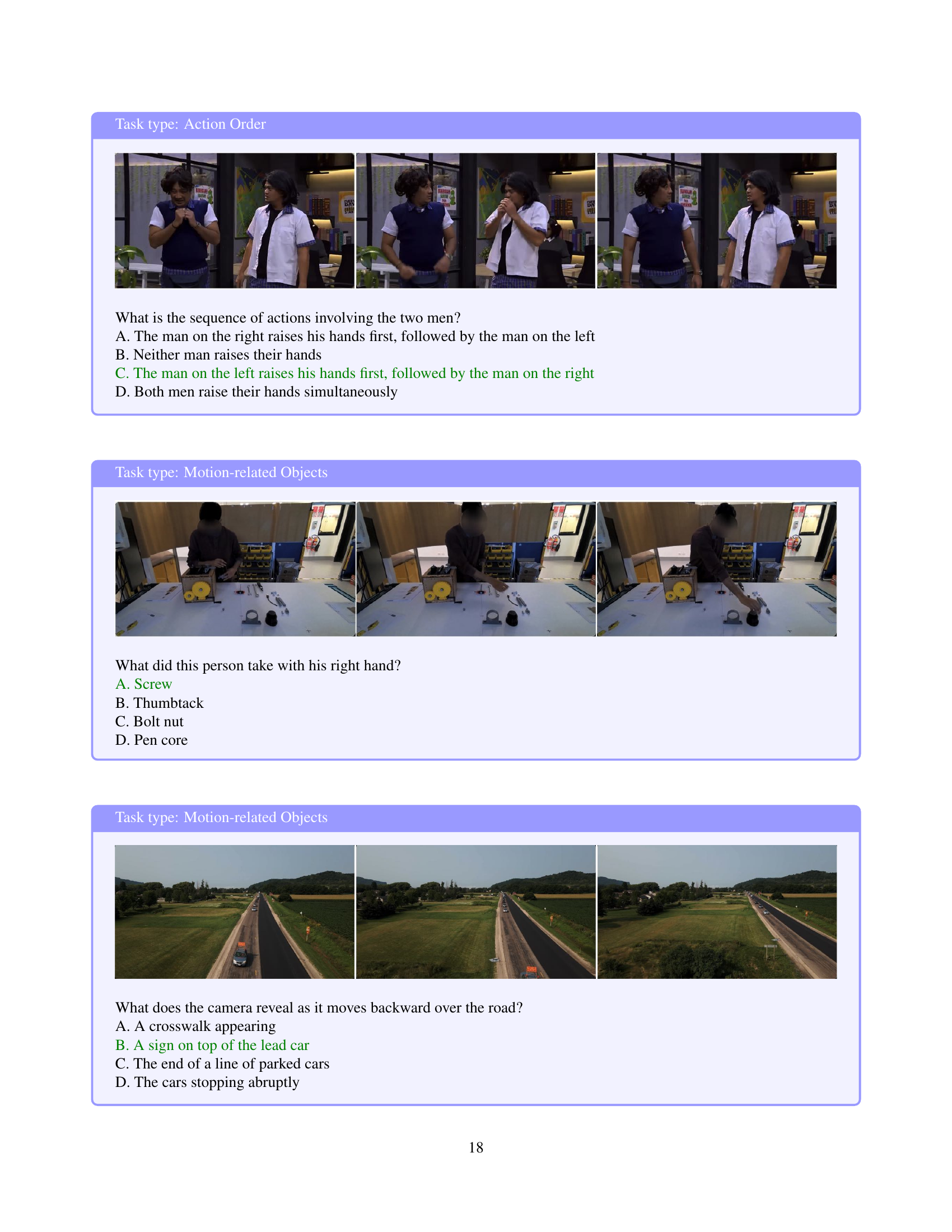

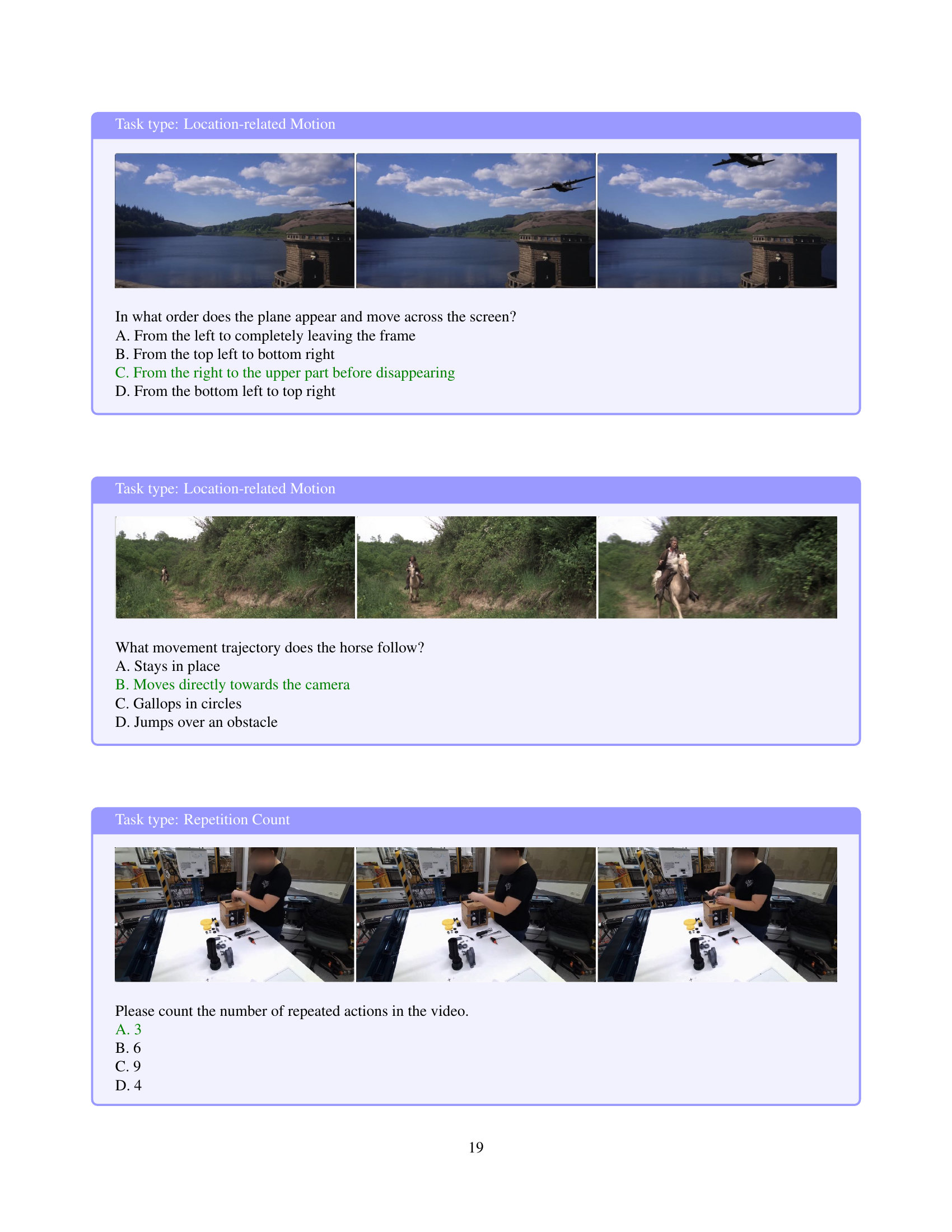

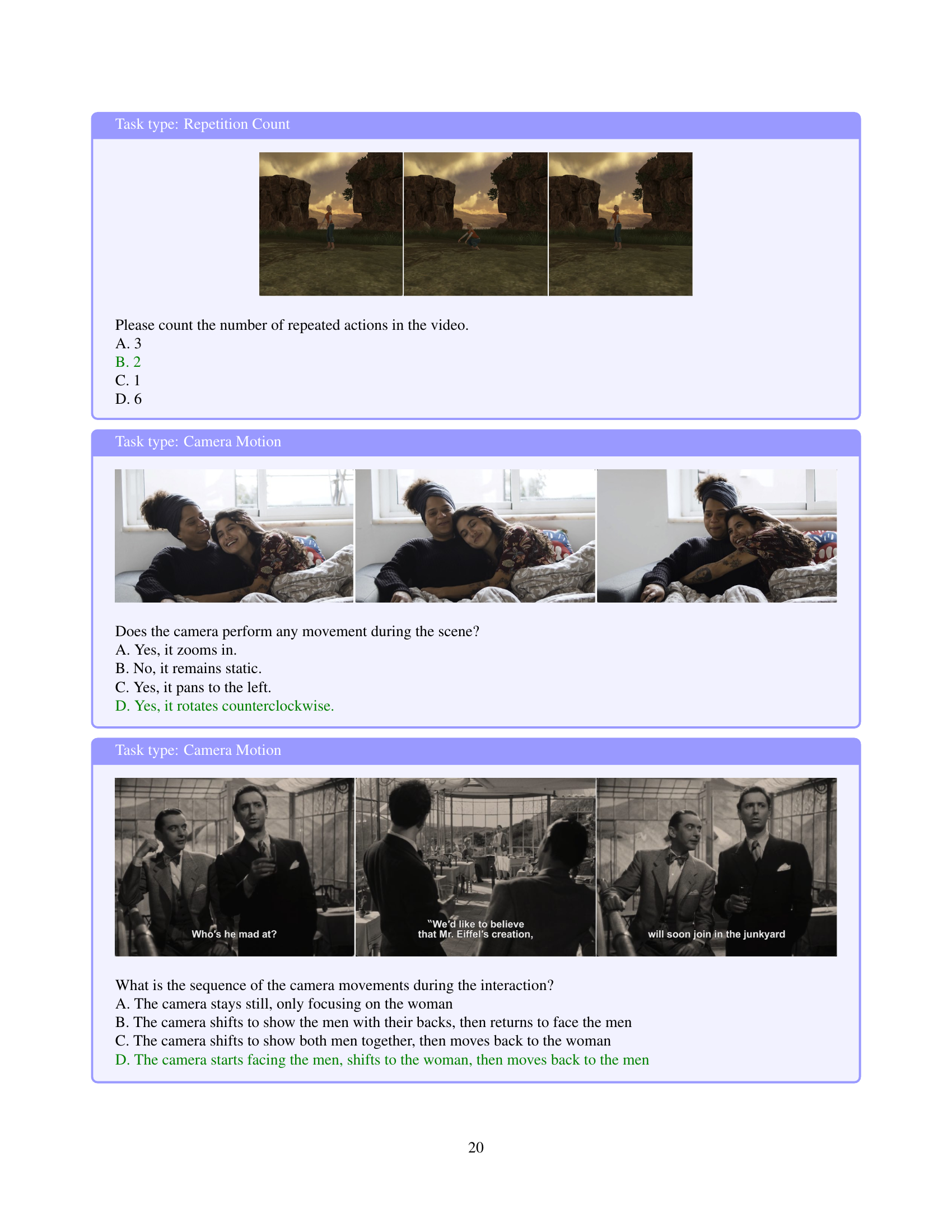

🔼 MotionBench is a new benchmark dataset for evaluating the fine-grained motion understanding capabilities of vision-language models (VLMs). It consists of 8052 multiple-choice questions paired with short video clips showing diverse dynamic actions from various settings, including daily life and medical scenarios. The questions are categorized into six primary tasks designed to test different aspects of motion-level perception (motion recognition, location-related motion, action order, repetition count, motion-related objects, and camera motion). MotionBench’s key feature is its significantly higher annotation density compared to existing video understanding benchmarks, which allows for a more precise evaluation of fine-grained movements.

read the caption

Figure 2: We propose MotionBench, a collection of manually curated multi-choice queries with video clips featuring dynamic changes from various scenes such as daily life and medical instructions. We devise six primary tasks to evaluate the capability of motion-level perception. Unlike previous story-level and event-level benchmarks, MotionBench is characterized by a significantly higher annotation density, allowing for the assessment of fine-grained motions.

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of option selections across all questions in the MotionBench dataset. It helps to illustrate the balance (or imbalance) of the multiple choice answers provided for each question in the benchmark, revealing whether the answers are evenly distributed or if some options are favored more than others. This is a key aspect of evaluating the quality and fairness of a multiple choice question benchmark.

read the caption

(a) Option distribution

🔼 This histogram shows the distribution of video durations within the MotionBench dataset. The x-axis represents the duration of videos in seconds, and the y-axis represents the frequency or count of videos with that duration. The distribution shows the range of video lengths included in the MotionBench benchmark, indicating the dataset’s diversity in terms of video length.

read the caption

(b) Video duration

🔼 This histogram displays the distribution of annotation lengths (number of words) for the questions within the MotionBench dataset. It shows the frequency of different annotation lengths, giving insight into the level of detail present in the questions and the complexity of the descriptions needed to adequately capture fine-grained motion.

read the caption

(c) Annotation length

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of the number of questions per video in the MotionBench dataset. It reveals the variability in the number of questions asked about each video, indicating a range of complexity and detail in the annotations.

read the caption

(d) QA per video

🔼 Figure 3 presents a detailed statistical overview of the MotionBench dataset. The subfigures illustrate the distribution of options in multiple-choice questions (a), video durations (b), the number of questions per video (d), and the lengths of annotations (c). These visualizations provide insights into the dataset’s composition and characteristics, aiding in a comprehensive understanding of its scale, complexity, and diversity of video content.

read the caption

Figure 3: Basic statistics of MotionBench.

🔼 This figure showcases an example of how dynamic information is annotated in the MotionBench dataset. It includes a short video clip description highlighting changes that occur over time. This caption is then followed by a multiple-choice question related to the video, demonstrating the level of detail and specificity in the MotionBench annotations. The purpose is to illustrate the richness of the annotations and highlight the focus on fine-grained motion-level understanding, differentiating it from existing benchmarks that often rely solely on the initial frame or static descriptions.

read the caption

Figure 4: Example of dynamic information annotation

🔼 Figure 5 illustrates four different approaches to video compression before feeding the data into a Vision Language Model (VLM) decoder. The first method (‘Without Temporal Fusion’) processes each frame individually. The second (‘Pre-Encoder Fusion’) merges frames before visual encoding. The third (‘Post-Encoder Fusion’) encodes frames separately and then combines their features. Finally, the authors’ proposed method (‘Through-Encoder Fusion’) integrates the fusion of frames within the visual encoder, resulting in a more efficient and effective compression strategy. The figure focuses specifically on the steps preceding the VLM decoder to highlight the differences in how temporal compression is handled.

read the caption

Figure 5: Summarization of prevalent paradigms for video compression and our proposed Through-Encoder Fusion (TE Fusion). Here we only illustrate the part before the VLM decoder where temporal compression performs.

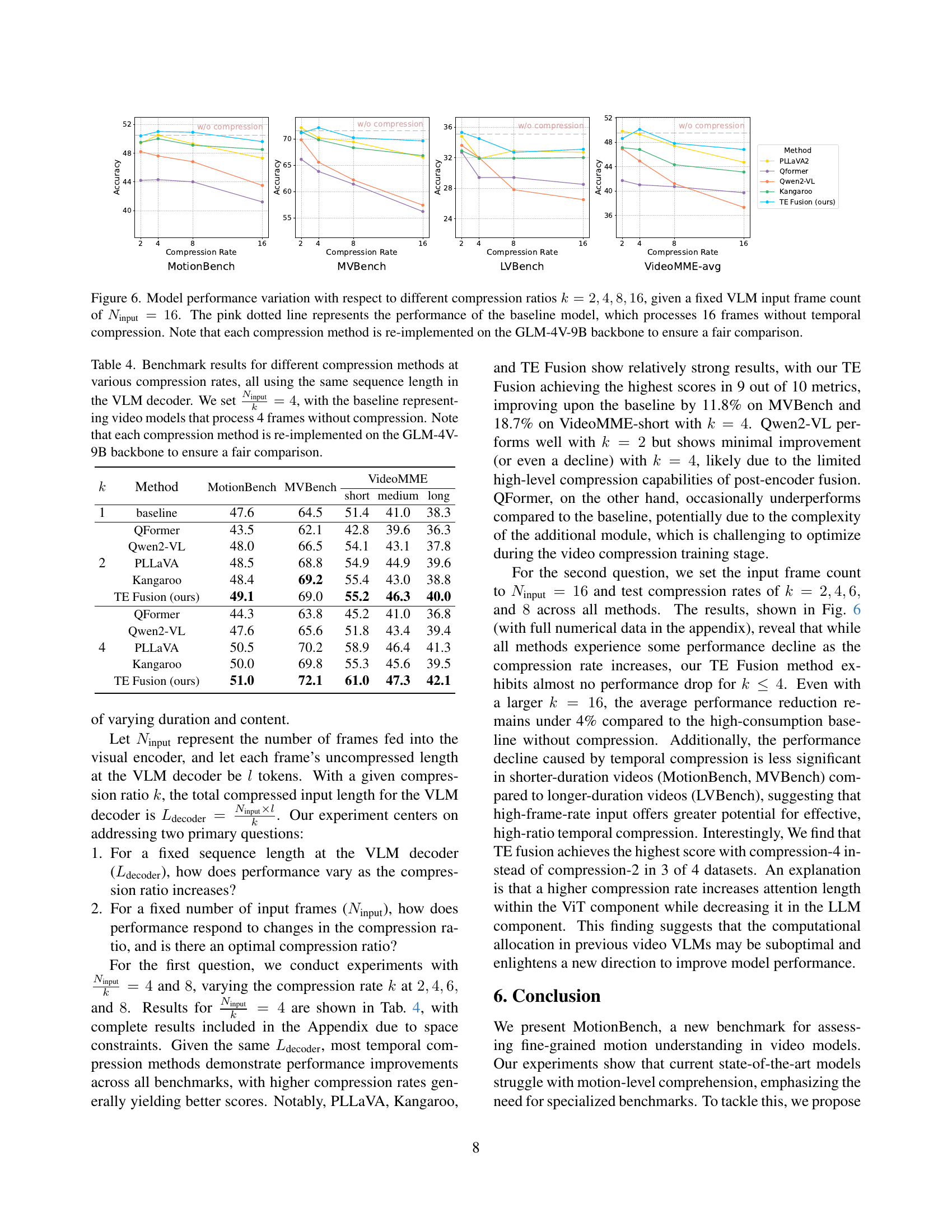

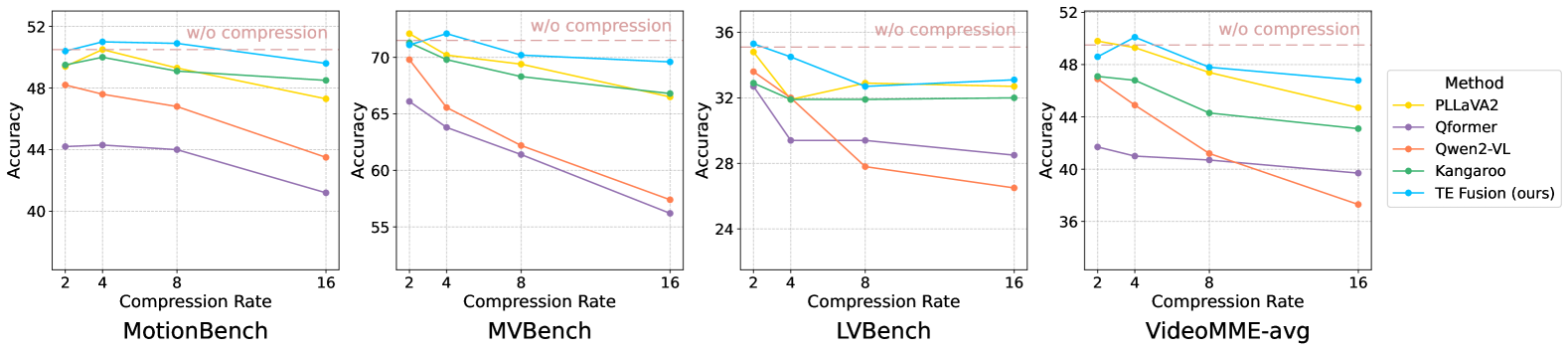

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comparative analysis of various video compression techniques’ impact on model performance. The experiment uses a fixed number of input frames (Ninput = 16) to the Vision Language Model (VLM), while varying the compression ratio (k = 2, 4, 8, 16). The results are shown for four different video compression methods: QFormer, PLLaVA, Kangaroo, and the authors’ proposed Through-Encoder Fusion (TE Fusion). A baseline representing a model processing 16 frames without compression is also included (pink dotted line). Each compression method was re-implemented using the same GLM-4V-9B backbone for a fair comparison. The figure displays the accuracy achieved by each method on four benchmarks: MotionBench, MVBench, LVBench, and VideoMME across different compression ratios, illustrating how well each technique balances compression with accuracy in video understanding.

read the caption

Figure 6: Model performance variation with respect to different compression ratios k=2,4,8,16𝑘24816k=2,4,8,16italic_k = 2 , 4 , 8 , 16, given a fixed VLM input frame count of Ninput=16subscript𝑁input16N_{\text{input}}=16italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT input end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 16. The pink dotted line represents the performance of the baseline model, which processes 16 frames without temporal compression. Note that each compression method is re-implemented on the GLM-4V-9B backbone to ensure a fair comparison.

More on tables

| Category |

|---|

| web videos, movies |

| synthetic videos, datasets |

🔼 Table 2 details the process of creating the MotionBench dataset. It breaks down the dataset creation into three categories: videos with complex interactions, videos from specific domains (like medical or sports), and synthetic videos. For each category, it shows the number of videos and associated questions (N. Vid/QA), the source of the videos (whether collected directly or from an existing dataset), how the videos were processed (e.g., scene segmentation), and whether the questions and answers were automatically generated or manually annotated. The table also lists the minimum resolution (min(H,W)) and minimum duration (len) of the processed video clips. This provides a detailed overview of how the MotionBench dataset was compiled, highlighting the different sources, processing steps, and annotation methods used for each category.

read the caption

Table 2: The MotionBench curation process. Categories [1-3] refer to “videos with intricate interactions”, “videos from specific fields” and “virtual videos”, detailed in Sec. 3.1. N. Vid/QA refers to the number of videos and queries in a category. min(H, W) is the minimum of the height and width of the video frames. len refers to the processed video duration. We automatically construct the queries in Virtual scenes, and manually annotate the other QA pairs in MotinBench.

| Category | # Videos/QAs | Source | Collection | Post-process | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2,355/4,922 | Pexels | Self-collected | Directly adopt | Caption & QA |

| Pandas-70M [3] | Open-sourced | Segment with scene detection | Caption & QA | ||

| Movie clips | Self-collected | Segment with scene detection | Caption & QA | ||

| 2 | 2,430/2,530 | MedVid [14] | Open-sourced | min(H,W)>448 & len∈[3,60]sec | QA |

| SportsSloMo [2] | Open-sourced | min(H,W)>448 & len∈[3,60]sec | QA | ||

| HA-ViD [52] | Open-sourced | min(H,W)>448 & len∈[3,60]sec | QA | ||

| 3 | 600/600 | Virtual scenes | Self-collected | Remove renderings with occlusion | Automatic QA |

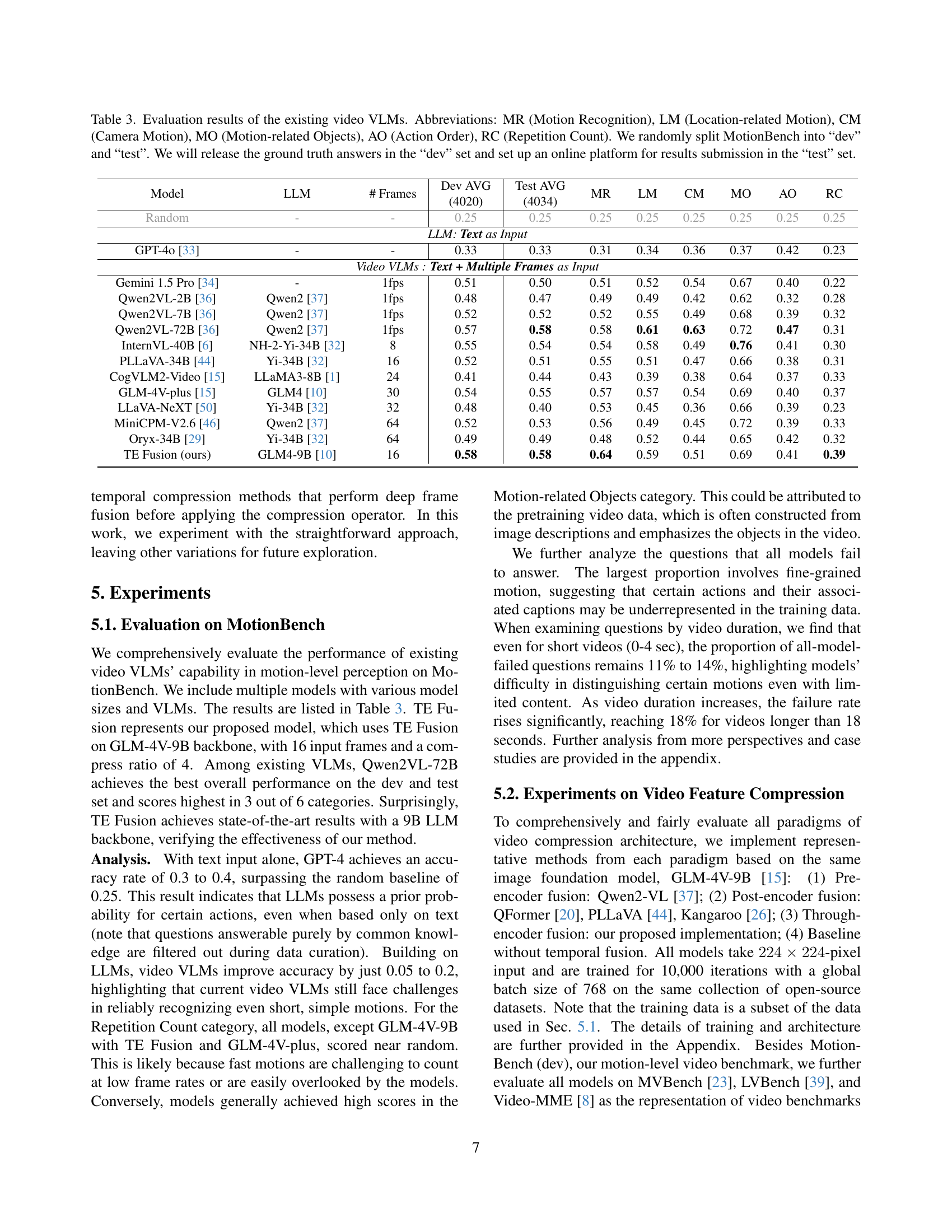

🔼 This table presents the performance of various existing Video Vision Language Models (VLMs) on the MotionBench benchmark. The benchmark assesses six categories of motion-related tasks: Motion Recognition (MR), Location-related Motion (LM), Camera Motion (CM), Motion-related Objects (MO), Action Order (AO), and Repetition Count (RC). The table shows the average performance across a randomly split development set (‘dev’) and a held-out test set (’test’) of the MotionBench dataset. The ‘dev’ set’s ground truth answers are released to facilitate model evaluation, while an online platform will be established for submitting and evaluating results on the ’test’ set. The results highlight that even well-established VLMs struggle with fine-grained motion comprehension.

read the caption

Table 3: Evaluation results of the existing video VLMs. Abbreviations: MR (Motion Recognition), LM (Location-related Motion), CM (Camera Motion), MO (Motion-related Objects), AO (Action Order), RC (Repetition Count). We randomly split MotionBench into “dev” and “test”. We will release the ground truth answers in the “dev” set and set up an online platform for results submission in the “test” set.

| Model | LLM | # Frames | Dev AVG (4020) | Test AVG (4034) | MR | LM | CM | MO | AO | RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | - | - | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| LLM: Text as Input | ||||||||||

| GPT-4o [33] | - | - | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.23 |

| Video VLMs : Text + Multiple Frames as Input | ||||||||||

| Gemini 1.5 Pro [34] | - | 1fps | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.22 |

| Qwen2VL-2B [36] | Qwen2 [37] | 1fps | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| Qwen2VL-7B [36] | Qwen2 [37] | 1fps | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.32 |

| Qwen2VL-72B [36] | Qwen2 [37] | 1fps | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.31 |

| InternVL-40B [6] | NH-2-Yi-34B [32] | 8 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.30 |

| PLLaVA-34B [44] | Yi-34B [32] | 16 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.31 |

| CogVLM2-Video [15] | LLaMA3-8B [1] | 24 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| GLM-4V-plus [15] | GLM4 [10] | 30 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.37 |

| LLaVA-NeXT [50] | Yi-34B [32] | 32 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.23 |

| MiniCPM-V2.6 [46] | Qwen2 [37] | 64 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.33 |

| Oryx-34B [29] | Yi-34B [32] | 64 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.32 |

| TE Fusion (ours) | GLM4-9B [10] | 16 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.39 |

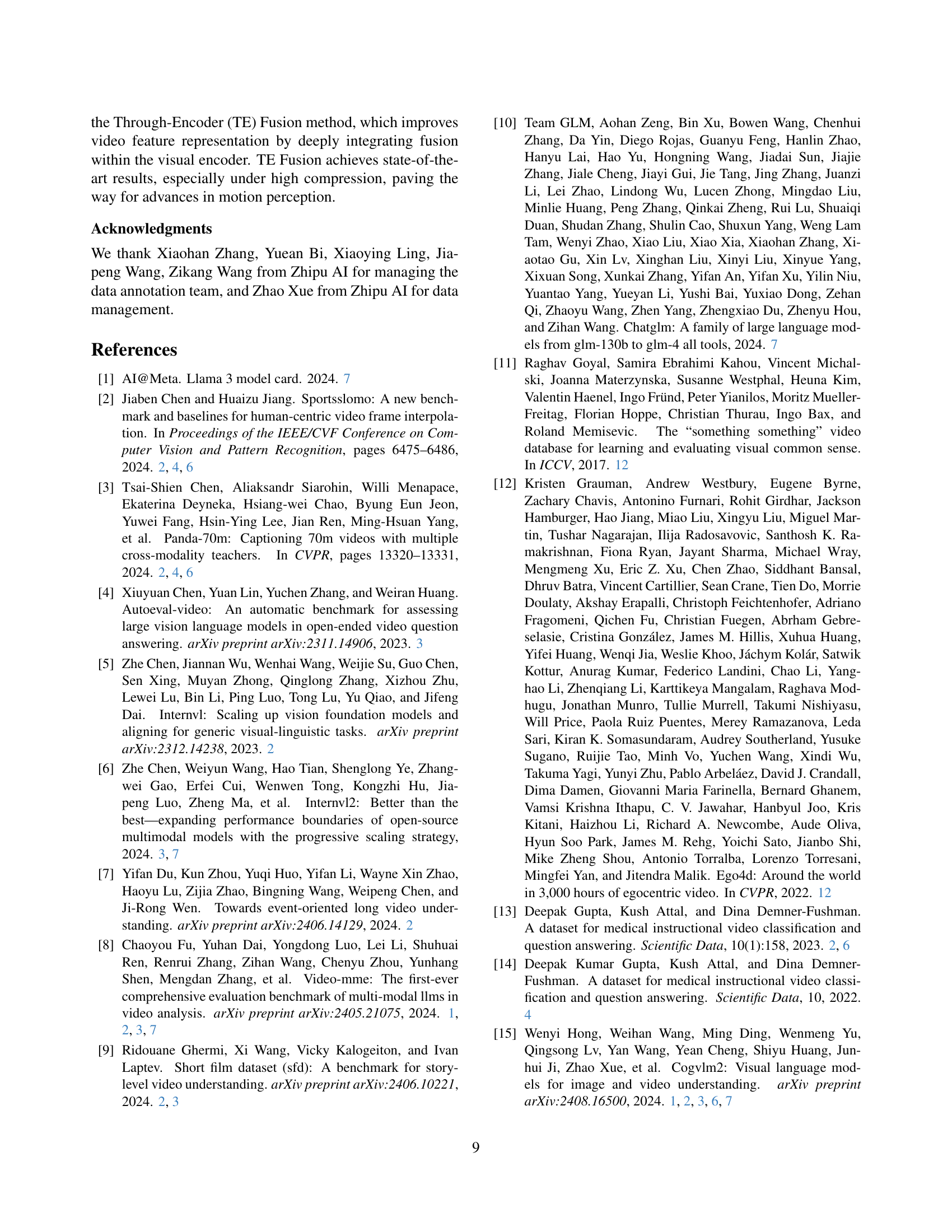

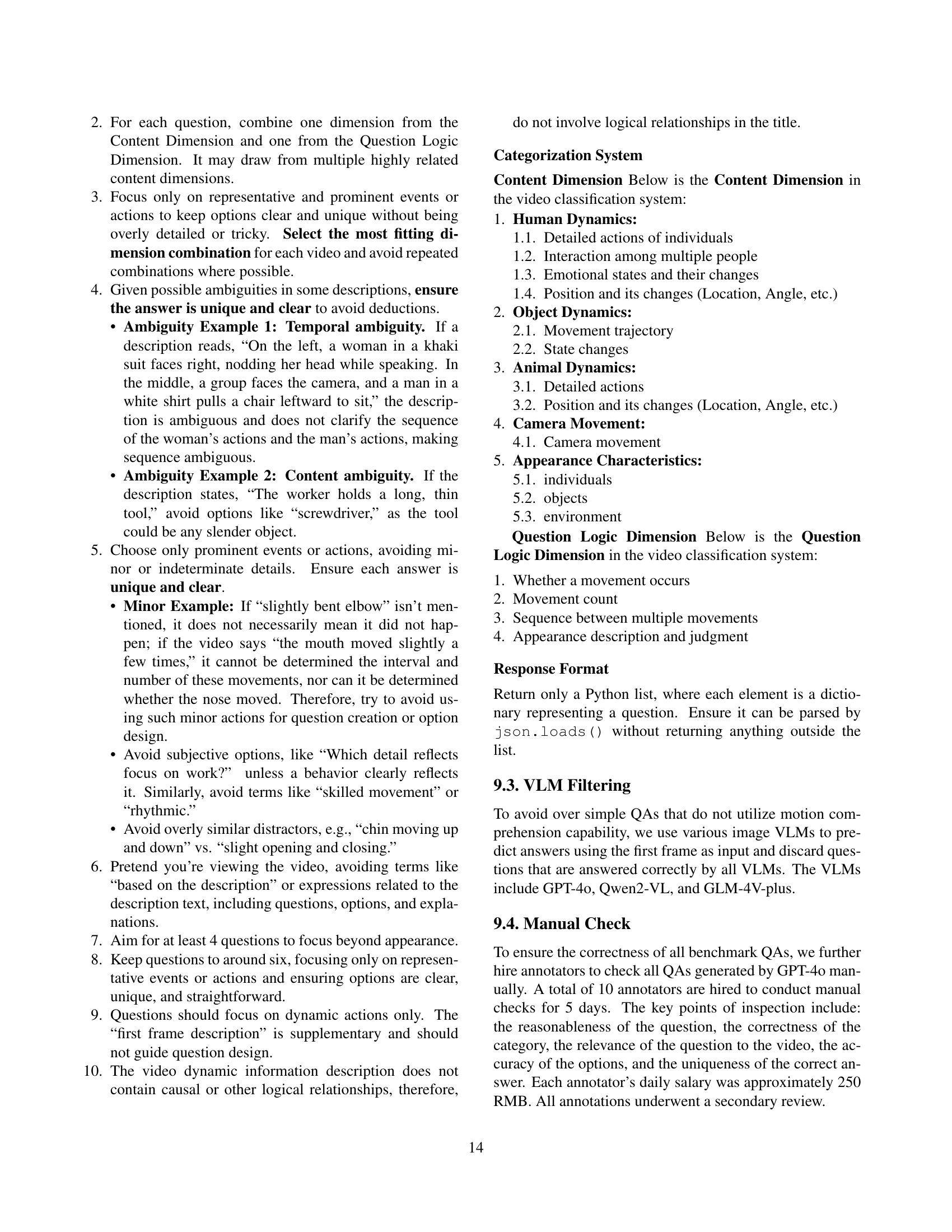

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different video compression methods’ performance on the MotionBench benchmark. The experiment controls for the length of the input sequence to the VLM decoder, holding it constant while varying the compression ratio (k) and the number of input frames (Ninput). The results show the performance for each compression technique (QFormer, Qwen2-VL, PLLaVA, Kangaroo, and TE Fusion) at different compression ratios, with a baseline representing a model that uses 4 frames without compression. All methods were implemented using the same GLM-4V-9B backbone for fair comparison.

read the caption

Table 4: Benchmark results for different compression methods at various compression rates, all using the same sequence length in the VLM decoder. We set Ninputk=4subscript𝑁input𝑘4\frac{N_{\text{input}}}{k}=4divide start_ARG italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT input end_POSTSUBSCRIPT end_ARG start_ARG italic_k end_ARG = 4, with the baseline representing video models that process 4 frames without compression. Note that each compression method is re-implemented on the GLM-4V-9B backbone to ensure a fair comparison.

| Dev AVG | |

|---|---|

| (4020) |

🔼 Table 5 presents the evaluation results of existing video Vision Language Models (VLMs) on the MotionBench benchmark. It shows the average performance (across a development and test set) of various models on six motion-related tasks: Motion Recognition (MR), Location-related Motion (LM), Camera Motion (CM), Motion-related Objects (MO), Action Order (AO), and Repetition Count (RC). The table includes the model name, the underlying Large Language Model (LLM), the number of frames used as input, and the average accuracy scores on the development and test sets for each task, as well as an overall average accuracy. A random baseline is also provided for comparison.

read the caption

Table 5:

| Test AVG | |

|---|---|

| (4034) |

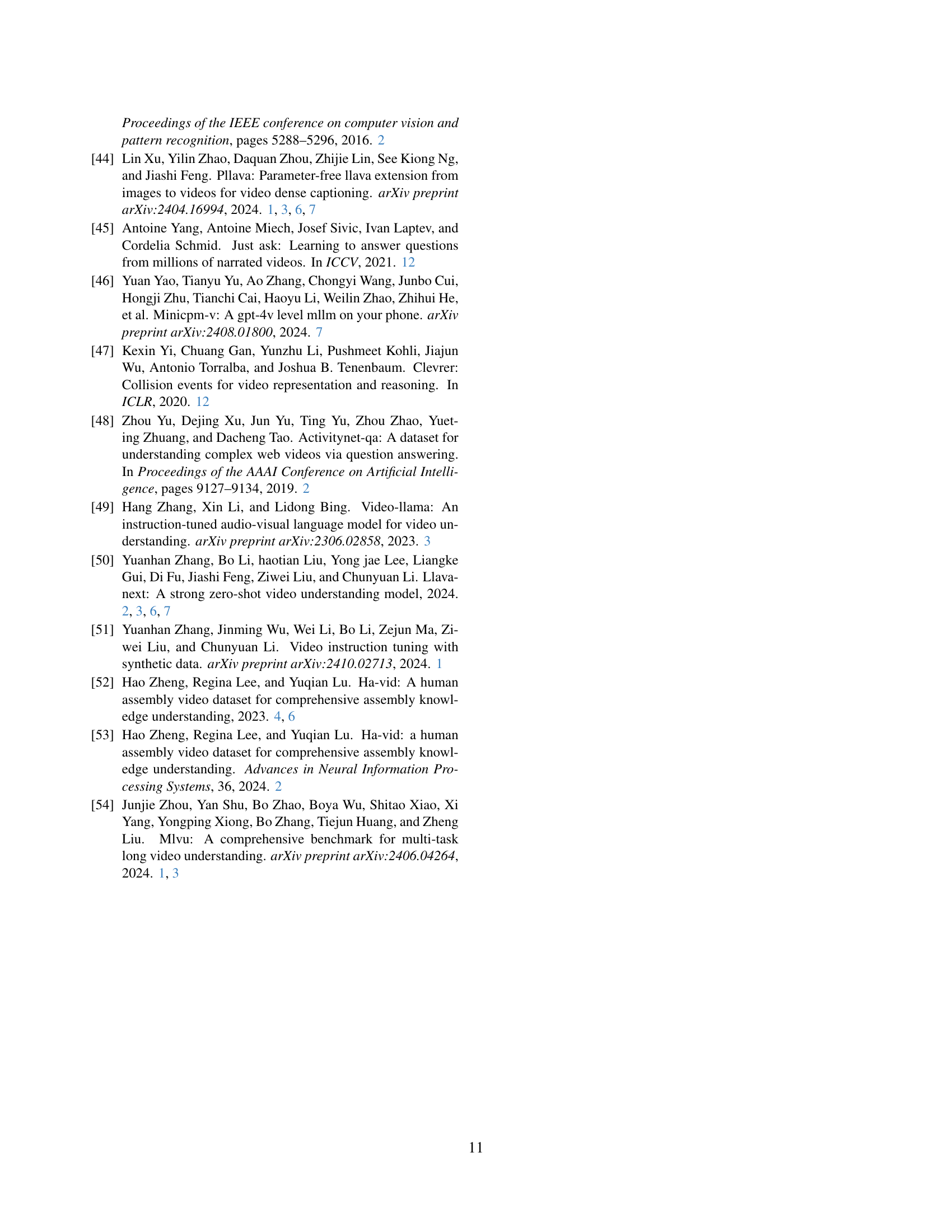

🔼 This table details the specific configurations of the Vision Language Models (VLMs) used in the experiments. It lists the hyperparameters for the decoder and the visual encoder components of the various models, allowing for comparison across different architectures and highlighting the key settings that impact performance. The configurations help in understanding and replicating the experimental setup.

read the caption

Table 6: The model configurations of all ablated architectures.

| k | Method | MotionBench | MVBench | VideoMME short | VideoMME medium | VideoMME long |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | baseline | 47.6 | 64.5 | 51.4 | 41.0 | 38.3 |

| 2 | QFormer | 43.5 | 62.1 | 42.8 | 39.6 | 36.3 |

| 2 | Qwen2-VL | 48.0 | 66.5 | 54.1 | 43.1 | 37.8 |

| 2 | PLLaVA | 48.5 | 68.8 | 54.9 | 44.9 | 39.6 |

| 2 | Kangaroo | 48.4 | 69.2 | 55.4 | 43.0 | 38.8 |

| 2 | TE Fusion (ours) | 49.1 | 69.0 | 55.2 | 46.3 | 40.0 |

| 4 | QFormer | 44.3 | 63.8 | 45.2 | 41.0 | 36.8 |

| 4 | Qwen2-VL | 47.6 | 65.6 | 51.8 | 43.4 | 39.4 |

| 4 | PLLaVA | 50.5 | 70.2 | 58.9 | 46.4 | 41.3 |

| 4 | Kangaroo | 50.0 | 69.8 | 55.3 | 45.6 | 39.5 |

| 4 | TE Fusion (ours) | 51.0 | 72.1 | 61.0 | 47.3 | 42.1 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different video compression methods’ performance on the MotionBench benchmark. The experiment controls for the total number of frames processed by the VLM decoder (Ldecoder) by adjusting the compression ratio (k) and number of input frames (Ninput). The table shows accuracy results across various metrics for four different compression methods (QFormer, Qwen2-VL, PLLAVA, Kangaroo) and the proposed Through-Encoder Fusion (TE Fusion) method. The baseline represents a model without temporal compression processing only 4 frames. Results are shown for different compression ratios (k=2, 4, 8) and numbers of input frames (Ninput=4, 8). The goal is to evaluate how different compression techniques affect model accuracy while maintaining a consistent sequence length within the VLM decoder.

read the caption

Table 7: Benchmark results for different compression methods at various compression rates, all using the same sequence length in the VLM decoder. We set Ninputk=4,8subscript𝑁input𝑘48\frac{N_{\text{input}}}{k}=4,8divide start_ARG italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT input end_POSTSUBSCRIPT end_ARG start_ARG italic_k end_ARG = 4 , 8, with the baseline representing video models that process 4 frames without compression. Note that each compression method is re-implemented on the GLM-4V-9B backbone to ensure a fair comparison.

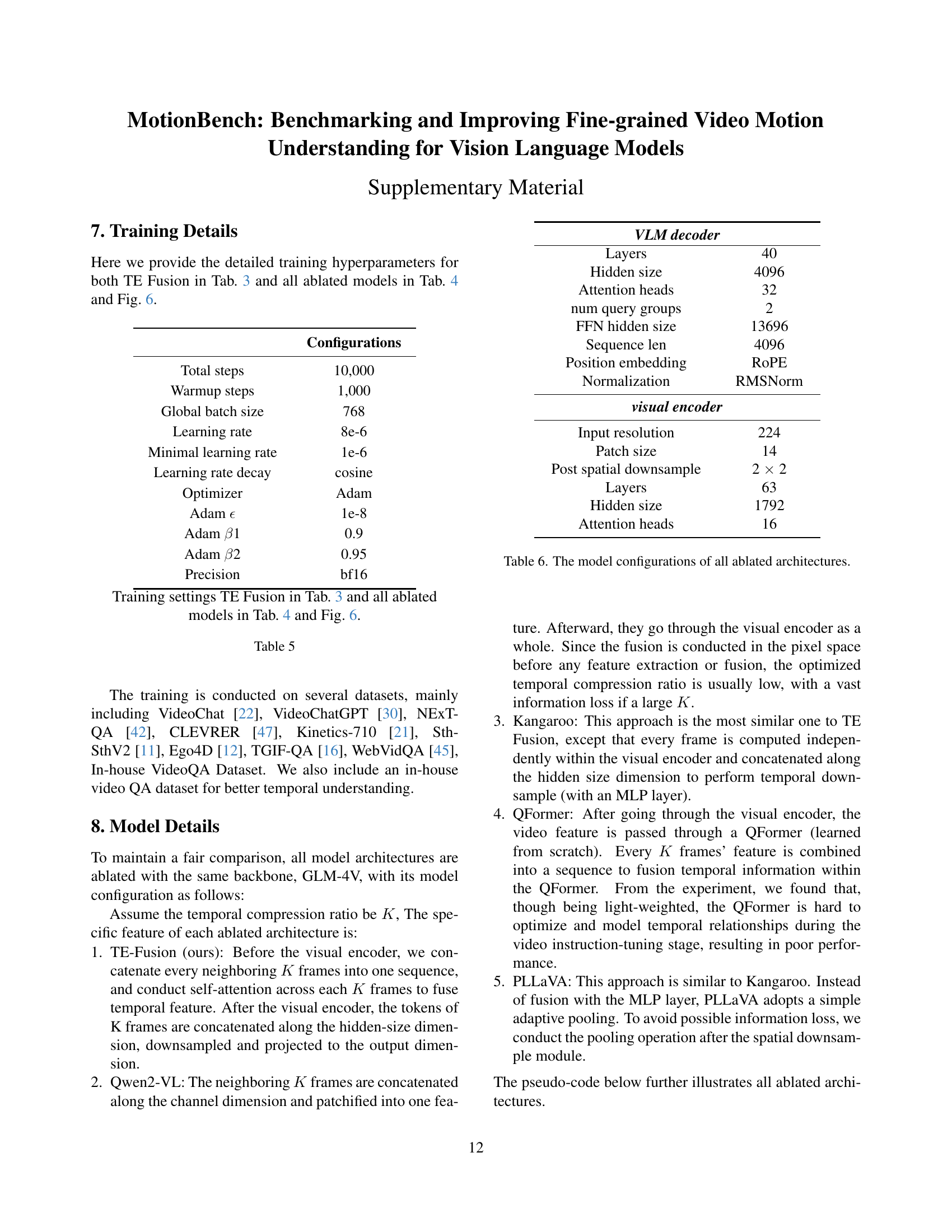

| Configurations |

|---|

| Total steps |

| Warmup steps |

| Global batch size |

| Learning rate |

| Minimal learning rate |

| Learning rate decay |

| Optimizer |

| Adam ϵ |

| Adam β1 |

| Adam β2 |

| Precision |

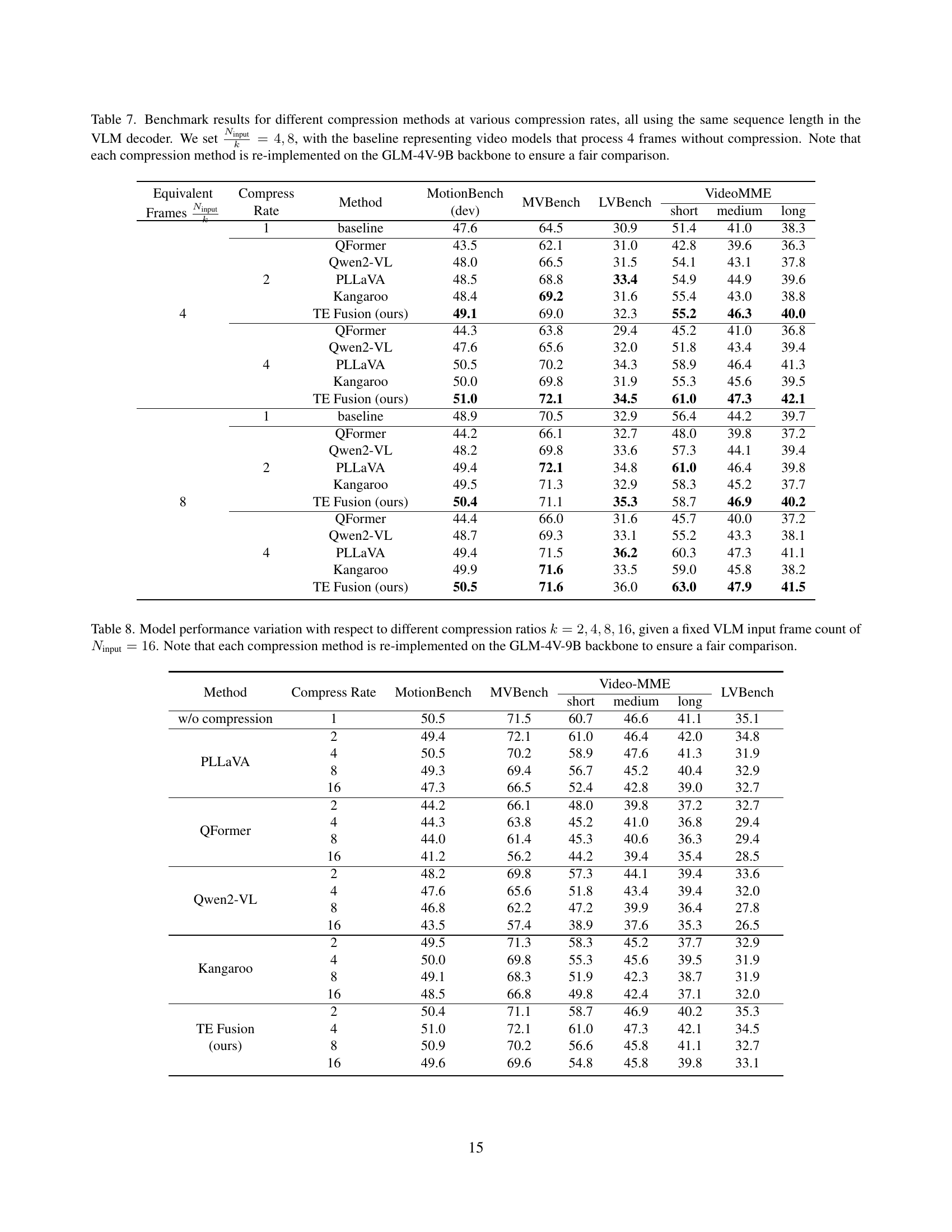

🔼 Table 8 presents the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of various video compression techniques on video language models (VLMs). The experiment uses a fixed number of input frames (Ninput = 16) for each VLM and varies the compression ratio (k = 2, 4, 8, 16). The table shows how different compression methods, including pre-encoder fusion, post-encoder fusion, through-encoder fusion (TE Fusion), and a baseline without temporal fusion, affect the performance of the model on the MotionBench, MVBench, LVBench, and VideoMME datasets. Each compression method was implemented using the GLM-4V-9B backbone for a fair comparison. The table allows for assessment of how different compression strategies affect model performance across different datasets and compression ratios.

read the caption

Table 8: Model performance variation with respect to different compression ratios k=2,4,8,16𝑘24816k=2,4,8,16italic_k = 2 , 4 , 8 , 16, given a fixed VLM input frame count of Ninput=16subscript𝑁input16N_{\text{input}}=16italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT input end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 16. Note that each compression method is re-implemented on the GLM-4V-9B backbone to ensure a fair comparison.

Full paper#