↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Real-world video super-resolution (VSR) aims to enhance low-resolution videos with realistic details and smooth transitions. Existing GAN-based methods often over-smooth images, while diffusion models struggle with maintaining temporal consistency. Text-to-video models offer a promising approach to VSR but may introduce artifacts and compromise fidelity.

The proposed STAR method leverages the power of text-to-video models for real-world VSR by introducing a novel Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM). LIEM improves local detail and reduces artifacts. Furthermore, STAR utilizes a Dynamic Frequency Loss to enhance fidelity and improve the overall quality. This new approach achieves state-of-the-art results on several benchmarks, demonstrating superior spatiotemporal performance and paving the way for future advances in real-world VSR.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances real-world video super-resolution (VSR) by leveraging the power of text-to-video models. It addresses the limitations of existing methods, offering a novel approach that produces more realistic and temporally consistent results. This opens up new avenues for research in VSR and related fields, potentially impacting applications like video enhancement, restoration, and generation.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 presents a comparison of video super-resolution (VSR) results on both real-world and synthetic low-resolution video clips. The figure directly compares the output of the proposed STAR model against two state-of-the-art VSR methods ([73, 75]). The comparison highlights the superior performance of STAR in preserving fine details, particularly showcasing the more natural rendering of facial features and text compared to the other methods. The enhanced clarity and detail achieved by STAR are visually evident in the figure.

read the caption

Figure 1: Visualization comparisons on both real-world and synthetic low-resolution videos. Compared to the state-of-the-art VSR models [73, 75], our results demonstrate more natural facial details and better structure of the text. (Zoom-in for best view)

| Datasets | Metrics | Real-ESRGAN | DBVSR | RealBasicVSR | RealViformer | ResShift | StableSR | Upscale-A-Video | MGLDVSR | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDM10 | PSNR↑ | 22.41 | 19.65 | 23.64 | 24.00 | 22.90 | 23.50 | 21.29 | 23.74 | 23.91 |

| SSIM↑ | 0.6476 | 0.4747 | 0.6842 | 0.6896 | 0.5451 | 0.6599 | 0.5967 | 0.6826 | 0.7164 | |

| LPIPS↓ | 0.2769 | 0.4566 | 0.2514 | 0.2325 | 0.4036 | 0.2785 | 0.3006 | 0.2195 | 0.1885 | |

| DOVER↑ | 0.4831 | 0.0959 | 0.5039 | 0.5055 | 0.3252 | 0.3490 | 0.5309 | 0.4896 | 0.5422 | |

| E∗warp↓ | 11.17 | 12.56 | 5.14 | 3.57 | 12.69 | 8.89 | 2.83 | 6.03 | 2.68 | |

| REDS30 | PSNR↑ | 19.56 | 14.85 | 20.85 | 20.86 | 19.93 | 20.32 | 19.71 | 20.57 | 20.29 |

| SSIM↑ | 0.4862 | 0.2941 | 0.5469 | 0.5377 | 0.4261 | 0.5043 | 0.4315 | 0.5113 | 0.5411 | |

| LPIPS↓ | 0.3376 | 0.5915 | 0.2899 | 0.2597 | 0.4422 | 0.3857 | 0.3443 | 0.2240 | 0.2804 | |

| DOVER↑ | 0.3182 | 0.0600 | 0.3483 | 0.3400 | 0.2221 | 0.2519 | 0.2857 | 0.3857 | 0.4017 | |

| E∗warp↓ | 19.1 | 18.00 | 8.32 | 6.06 | 17.40 | 22.14 | 15.65 | 12.28 | 7.30 | |

| OpenVid30 | PSNR↑ | 24.62 | 21.14 | 24.63 | 26.21 | 24.29 | 24.91 | 24.41 | 24.73 | 25.30 |

| SSIM↑ | 0.7778 | 0.5887 | 0.7759 | 0.8080 | 0.6070 | 0.7633 | 0.7167 | 0.7686 | 0.8371 | |

| LPIPS↓ | 0.1994 | 0.4207 | 0.2297 | 0.1881 | 0.3902 | 0.2102 | 0.2479 | 0.2074 | 0.1011 | |

| DOVER↑ | 0.6992 | 0.1819 | 0.7345 | 0.7275 | 0.5435 | 0.6368 | 0.7201 | 0.7191 | 0.7393 | |

| E∗warp↓ | 8.46 | 12.11 | 4.12 | 2.52 | 9.78 | 8.87 | 4.72 | 4.82 | 1.82 | |

| VideoLQ | ILNIQE↓ | 27.95 | 27.19 | 26.29 | 26.11 | 25.92 | 29.97 | 24.49 | 23.94 | 25.35 |

| DOVER↑ | 0.4967 | 0.3392 | 0.5285 | 0.4804 | 0.4113 | 0.4775 | 0.4833 | 0.5319 | 0.5431 | |

| E∗warp↓ | 8.00 | 7.75 | 6.52 | 5.10 | 8.33 | 9.26 | 10.89 | 7.82 | 6.38 |

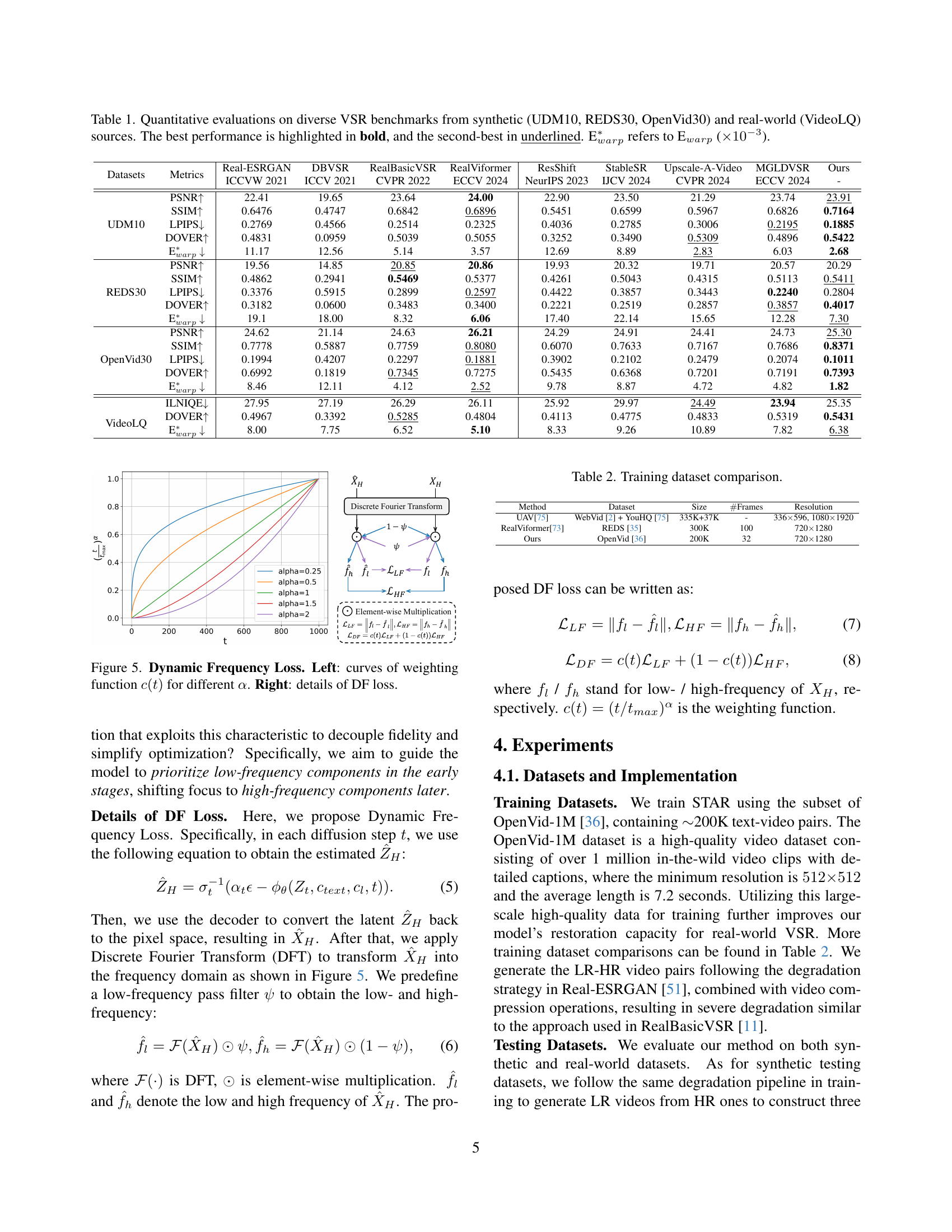

🔼 Table 1 presents a quantitative comparison of various video super-resolution (VSR) models on four benchmark datasets: UDM10, REDS30, OpenVid30 (synthetic), and VideoLQ (real-world). The table evaluates the performance of each model using several metrics: PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), SSIM (Structural Similarity Index), LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), DOVER (a video quality metric), and Ewarp (a measure of flow warping error). The best performance for each metric on each dataset is shown in bold, with the second-best result underlined. The Ewarp values are multiplied by 1000 for easier readability.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluations on diverse VSR benchmarks from synthetic (UDM10, REDS30, OpenVid30) and real-world (VideoLQ) sources. The best performance is highlighted in bold, and the second-best in underlined. Ewarp∗subscriptsuperscriptabsent𝑤𝑎𝑟𝑝{}^{*}_{warp}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT ∗ end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_w italic_a italic_r italic_p end_POSTSUBSCRIPT refers to Ewarp (×10−3absentsuperscript103\times 10^{-3}× 10 start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT - 3 end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT).

In-depth insights#

Real-world VSR#

Real-world Video Super-Resolution (VSR) presents significant challenges due to the unpredictable and complex degradations inherent in real-world videos. Unlike synthetic datasets with controlled distortions, real-world videos suffer from a combination of noise, blur, compression artifacts, and unknown degradations making accurate restoration extremely difficult. Existing methods often struggle to maintain both high spatial detail and temporal consistency, frequently resulting in either over-smoothed or blurry outputs. The integration of text-to-video (T2V) models offers a promising approach due to their powerful generative capabilities and ability to learn complex spatio-temporal relationships, but these models are susceptible to generating artifacts and may compromise the fidelity of the restored video. Therefore, robust solutions must address artifact reduction, fidelity enhancement, and the effective integration of T2V models without compromising temporal consistency. This necessitates careful consideration of local and global information processing, innovative loss functions to guide the restoration process, and potentially, new training strategies to better handle the variability of real-world degradations.

T2V Model Fusion#

The concept of ‘T2V Model Fusion’ in video super-resolution (VSR) offers a promising avenue for enhancing both spatial detail and temporal consistency. By integrating text-to-video (T2V) models into the VSR pipeline, the approach aims to leverage the rich semantic understanding and temporal modeling capabilities of T2V models to overcome limitations of traditional GAN-based or diffusion-based methods. A key challenge lies in effectively managing the artifacts introduced by complex real-world degradations, which can disrupt the delicate balance between fidelity and perceptual quality. This fusion approach necessitates careful consideration of how to combine the strengths of T2V models with existing VSR architectures, potentially via modules like Local Information Enhancement Modules (LIEM) that prioritize local details. Moreover, loss functions such as Dynamic Frequency (DF) Loss might be crucial in guiding the model to focus on different frequency components at various stages of the reconstruction process. Successful fusion would mean a significant improvement in VSR quality, generating videos with realistic spatial details and robust temporal consistency, addressing the challenges of over-smoothing and temporal inconsistencies. The research direction would involve investigating various fusion strategies, optimal model architectures, and the impact of different T2V model scales on the final results. Ultimately, the success hinges on achieving a refined balance between the generative power of T2V models and the precision requirements of accurate VSR.

STAR Framework#

The STAR framework, as described in the research paper, is a novel approach to real-world video super-resolution (VSR) that leverages the power of text-to-video (T2V) models. Its core innovation lies in effectively addressing the challenges of maintaining both spatial detail and temporal consistency often encountered in VSR, particularly with real-world, complex degradations. The framework incorporates a Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM) to refine local details and reduce artifacts. This module, placed before global self-attention in the T2V model, is crucial for handling real-world imperfections where global attention alone might over-smooth fine details. Additionally, a Dynamic Frequency (DF) Loss is introduced to improve fidelity by strategically focusing on low-frequency components early in the diffusion process and high-frequency components later. This adaptive approach separates fidelity and structure reconstruction, enhancing overall quality. The use of powerful pre-trained T2V models, combined with these enhancements, allows STAR to achieve state-of-the-art results on both synthetic and real-world datasets. The framework highlights the potential of powerful generative priors in practical VSR, significantly improving spatial detail, temporal consistency, and overall fidelity compared to existing methods. Further research could explore the impact of even more powerful T2V models and investigate the scalability and efficiency of the framework for higher resolution videos.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove or alter components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of this video super-resolution (VSR) research, ablation studies would likely investigate several key aspects of the proposed STAR model. The Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM), designed to improve local detail preservation, would be a primary focus. Experiments would compare performance with and without LIEM to quantify its impact on spatial detail and artifact reduction. Similarly, the Dynamic Frequency (DF) Loss, aimed at enhancing fidelity through frequency control during diffusion, would be thoroughly examined. Ablation tests would likely involve removing the DF Loss or varying its weighting function to determine its effectiveness in achieving high-fidelity outputs. Additionally, the choice of pre-trained text-to-video (T2V) model is a significant hyperparameter. Ablation studies would systematically assess the impact of different T2V models on the overall performance of the system. Results from these experiments would provide valuable insights into the relative importance of each module and help researchers understand how individual components contribute to the STAR’s success in achieving robust real-world VSR.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from the STAR model could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the model is crucial; reducing computational costs would greatly enhance its applicability. Investigating alternative T2V models and their impact on the quality of restoration is another key area. The current model relies on a specific architecture; exploring diverse architectures would be valuable. Furthermore, enhancing the handling of diverse degradation types remains a significant challenge. The paper focuses on specific degradations; a more robust model that handles a wider variety of distortions is necessary. Lastly, extending the model to handle higher resolution videos and longer sequences presents a compelling opportunity, expanding its applicability to more demanding video applications. A comprehensive evaluation across a broader spectrum of video types, capturing various lighting conditions, motion dynamics, and degradation profiles would further validate the model’s robustness and generalizability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

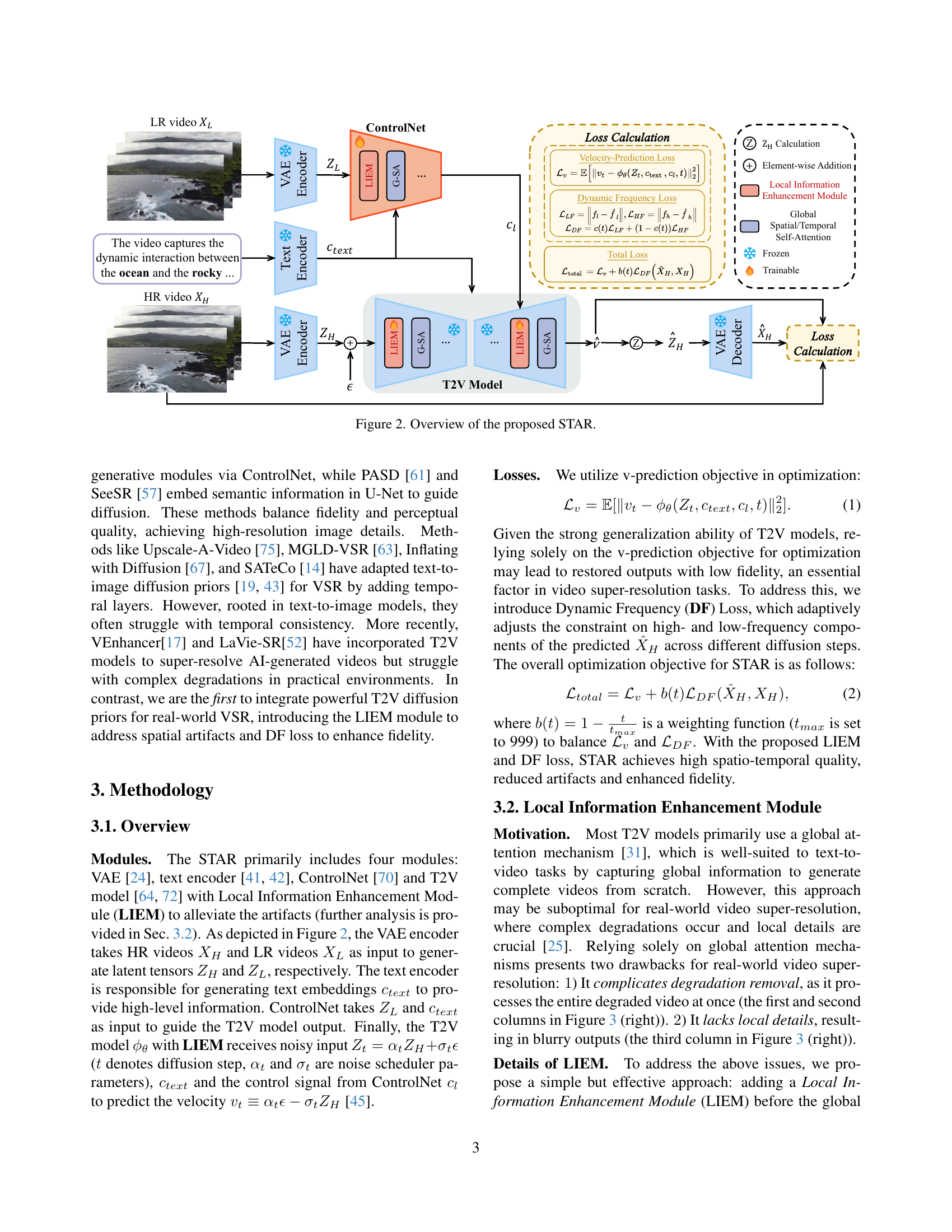

🔼 This figure provides a detailed overview of the STAR model architecture. It illustrates the flow of information through the various modules: the input LR video and text are processed by separate encoders. The LR video’s latent representation is combined with the text embeddings. A ControlNet module guides the T2V (Text-to-Video) model, which includes a Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM) and a Global Spatial/Temporal Self-Attention module. The T2V model then generates the predicted velocity and the HR video. Losses (velocity-prediction loss and dynamic frequency loss) are calculated and used for optimization during training.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of the proposed STAR.

🔼 Figure 3 demonstrates the effectiveness of the Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM). The left panel shows a schematic comparing using only global information against a combination of local and global information. The right panel presents visual comparisons on both real-world and synthetic videos to showcase the improved performance when employing both local and global information. The results highlight how LIEM enhances local details and mitigates artifacts by incorporating local information before the global self-attention mechanism.

read the caption

Figure 3: Motivation of LIEM. Left: schematic diagram illustrating the impact of using only global structure versus a combination of local and global structures. Right: visual comparison on real-world and synthetic videos. (Zoom-in for best view)

🔼 Figure 4 illustrates the concept of Dynamic Frequency Loss by showing the change in PSNR values for low- and high-frequency components throughout the diffusion process. The left panel graphs the PSNR, demonstrating that low-frequency details improve earlier in the process, while high-frequency details improve later. The right panel shows example visual results, supporting the observation that low-frequency components (larger structures) are recovered first, followed by high-frequency components (fine details like edges) as the diffusion process progresses.

read the caption

Figure 4: Motivation of DF Loss. Left: PSNR curves of low- and high-frequency components relative to ground truth across diffusion steps. The low-frequency PSNR increases during the early diffusion steps, while the high-frequency PSNR rises in the later diffusion steps. Right: visual results of low- and high-frequency components at different diffusion stage. (Zoom-in for best view)

🔼 Figure 5 illustrates the Dynamic Frequency Loss (DFL) used in the STAR model. The left panel shows curves of the weighting function c(t) for different values of α. This weighting function controls how much emphasis the loss places on low-frequency versus high-frequency components at different stages of the diffusion process. The right panel provides a detailed breakdown of the DFL components, showing how low-frequency and high-frequency components are combined based on the c(t) weighting to achieve balanced fidelity.

read the caption

Figure 5: Dynamic Frequency Loss. Left: curves of weighting function c(t)𝑐𝑡c(t)italic_c ( italic_t ) for different α𝛼\alphaitalic_α. Right: details of DF loss.

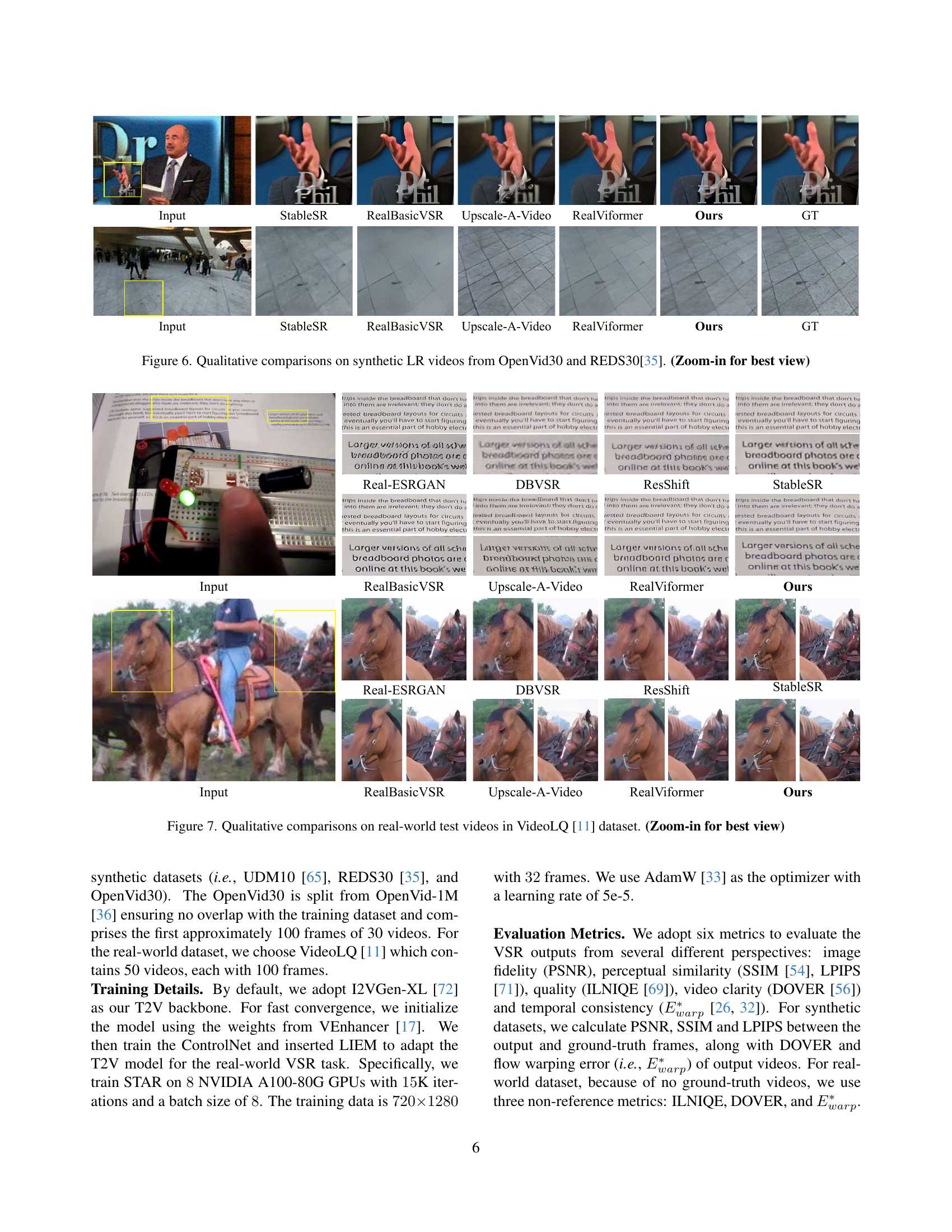

🔼 This figure displays a qualitative comparison of video super-resolution (VSR) results on synthetic low-resolution (LR) videos. It compares the output of several different VSR models, including StableSR, RealBasicVSR, Upscale-A-Video, RealViformer, and the authors’ proposed STAR model, against the ground truth (GT) high-resolution videos. The comparison demonstrates the visual quality differences between various methods in terms of detail, sharpness, and artifact reduction on both the OpenVid30 and REDS30 datasets. Zoom in for a detailed view of the results.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative comparisons on synthetic LR videos from OpenVid30 and REDS30[35]. (Zoom-in for best view)

🔼 Figure 7 presents a qualitative comparison of real-world video super-resolution (VSR) results on the VideoLQ dataset. It visually demonstrates the performance of various state-of-the-art VSR models, including Real-ESRGAN, DBVSR, RealBasicVSR, Upscale-A-Video, RealViformer, StableSR, and the authors’ proposed STAR model. The figure showcases the differences in the ability of each model to restore high-resolution videos from low-resolution inputs, highlighting improvements in sharpness, detail, and artifact reduction. Zooming in allows for better appreciation of the finer details of each restored video.

read the caption

Figure 7: Qualitative comparisons on real-world test videos in VideoLQ [11] dataset. (Zoom-in for best view)

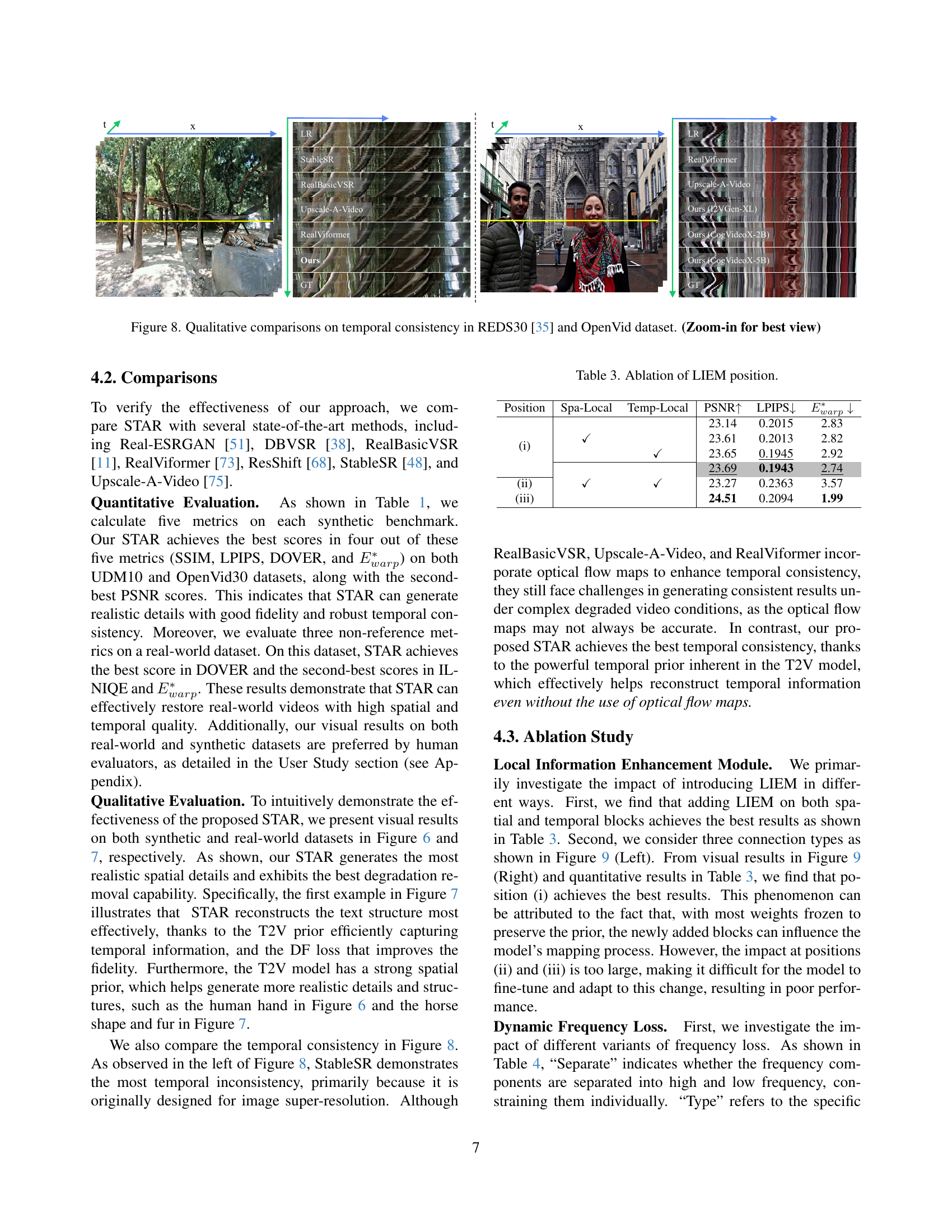

🔼 This figure demonstrates the temporal consistency of video super-resolution (VSR) results generated by different methods, including STAR (the proposed approach), on the REDS30 and OpenVid datasets. Temporal consistency refers to how well the model maintains smooth and realistic motion across consecutive frames in a video. The figure directly compares the results of STAR to those of several other state-of-the-art VSR methods. By visually inspecting the results, the user can easily assess which method yields a more temporally consistent video and the degree of artifacts or flickering that is present.

read the caption

Figure 8: Qualitative comparisons on temporal consistency in REDS30 [35] and OpenVid dataset. (Zoom-in for best view)

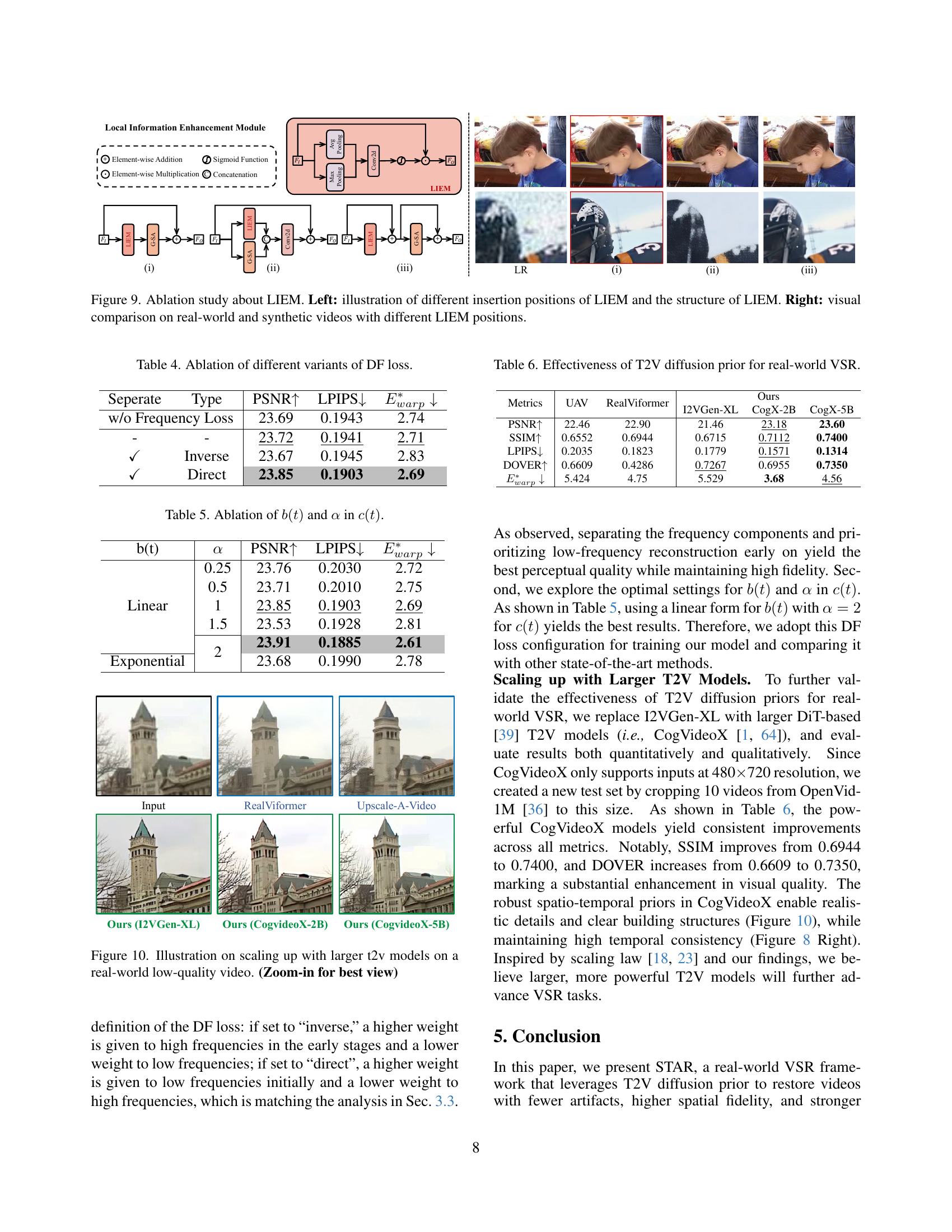

🔼 This figure presents an ablation study on the Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM). The left side illustrates the different positions where LIEM can be inserted within the model architecture and details its internal structure. The right side shows a visual comparison of real-world and synthetic video results obtained using LIEM in various positions, demonstrating the impact of LIEM’s placement on the overall performance of the model.

read the caption

Figure 9: Ablation study about LIEM. Left: illustration of different insertion positions of LIEM and the structure of LIEM. Right: visual comparison on real-world and synthetic videos with different LIEM positions.

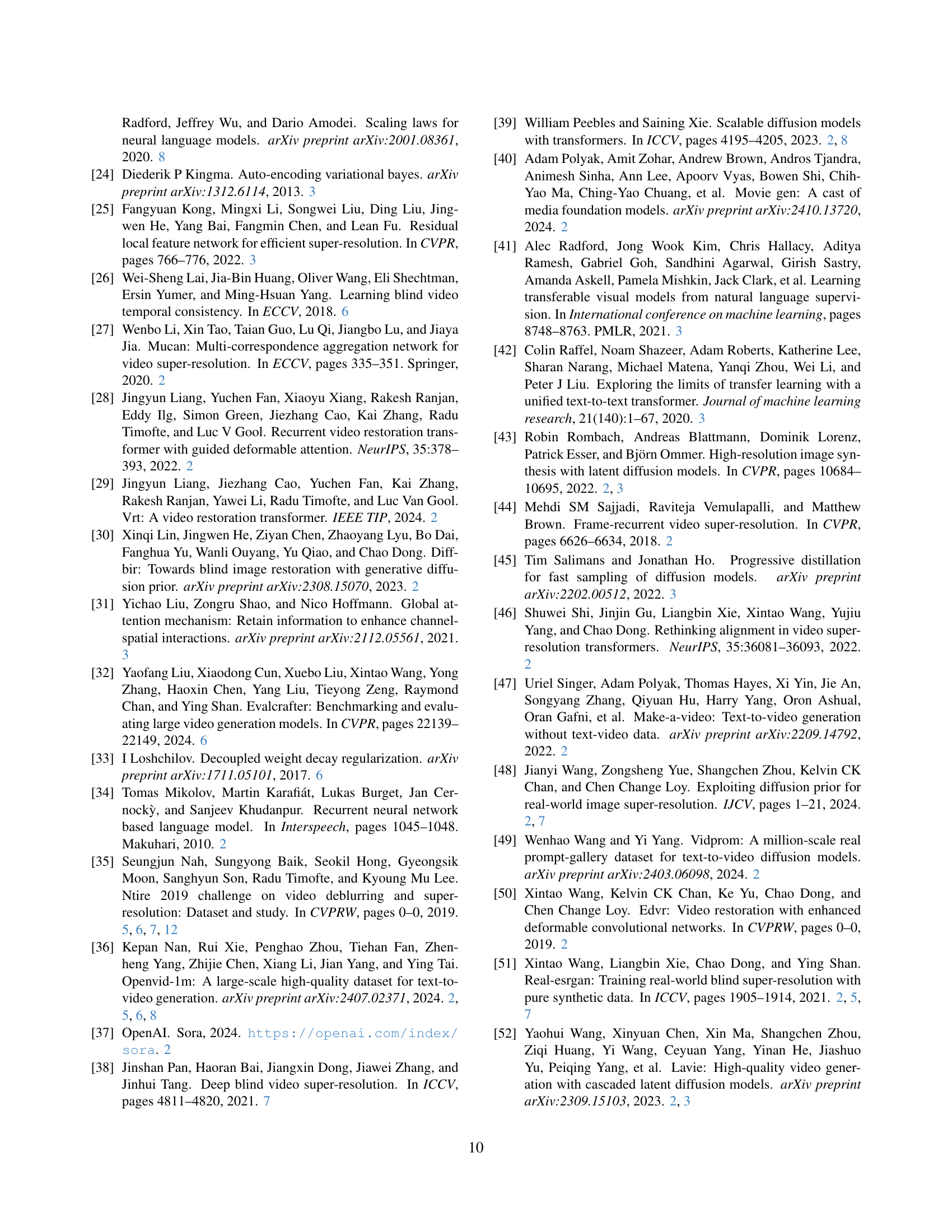

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of using larger text-to-video (T2V) models within the STAR framework. It showcases a real-world low-quality video enhanced by several different models, including the STAR model using different T2V backbones. By comparing the results, the figure highlights the improvements in visual quality obtained by leveraging more powerful T2V models for video super-resolution. Specifically, it illustrates the increases in detail and realism achieved when scaling up to larger T2V models. Zooming in on the image will reveal finer details.

read the caption

Figure 10: Illustration on scaling up with larger t2v models on a real-world low-quality video. (Zoom-in for best view)

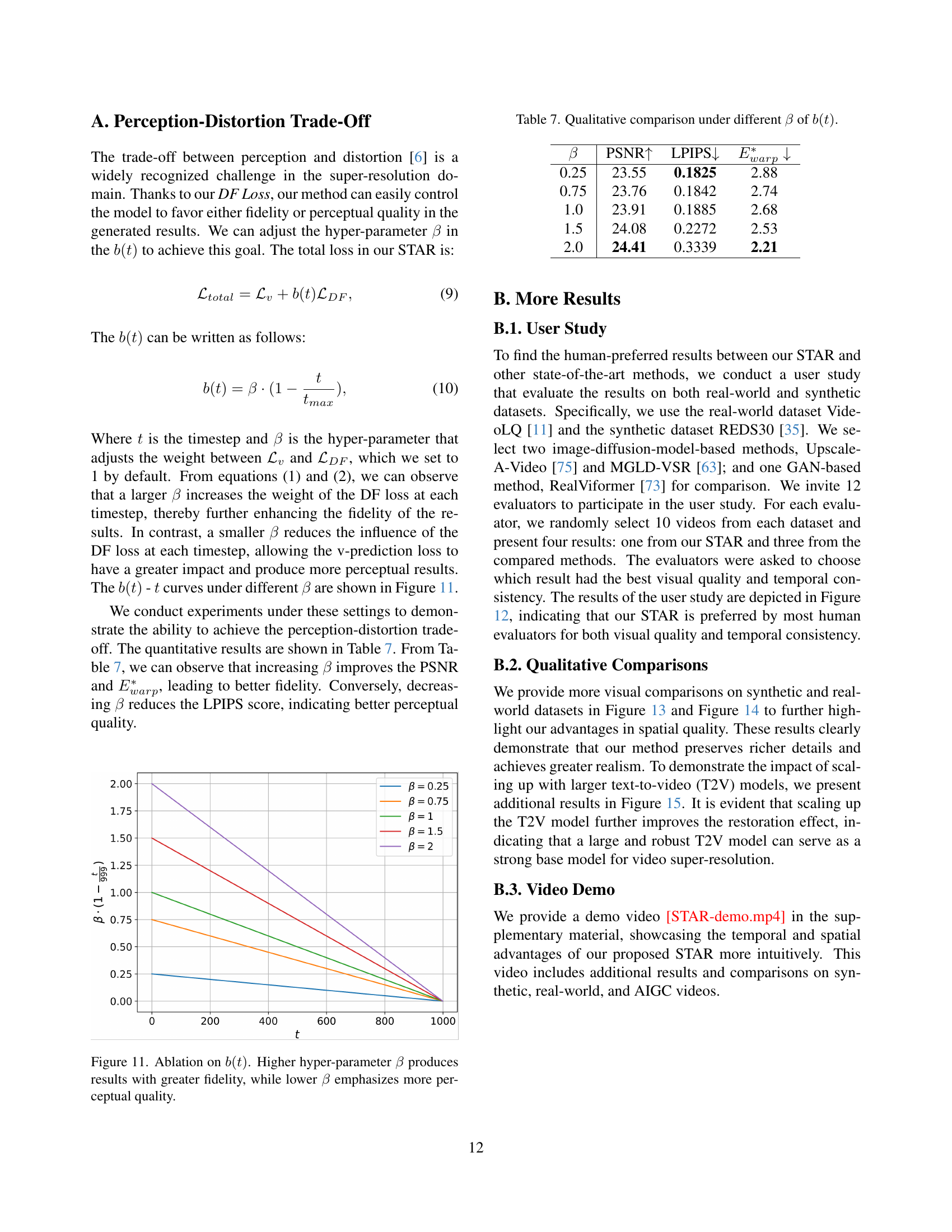

🔼 This figure shows the effect of changing the hyperparameter (\beta) in the weighting function (b(t) = \beta (1 - \frac{t}{t_{max}})) of the Dynamic Frequency Loss. The x-axis represents the diffusion timestep (t), and the y-axis represents the value of (b(t)). Different colored lines represent different values of (\beta). Higher values of (\beta) place more emphasis on the fidelity of the reconstruction, which leads to results with more accurate details but potentially less natural appearance. Lower values of (\beta) put more emphasis on perceptual quality, leading to results that may look more natural but may sacrifice some detail accuracy. The figure demonstrates the trade-off between fidelity and perceptual quality controlled by (\beta).

read the caption

Figure 11: Ablation on b(t)𝑏𝑡b(t)italic_b ( italic_t ). Higher hyper-parameter β𝛽\betaitalic_β produces results with greater fidelity, while lower β𝛽\betaitalic_β emphasizes more perceptual quality.

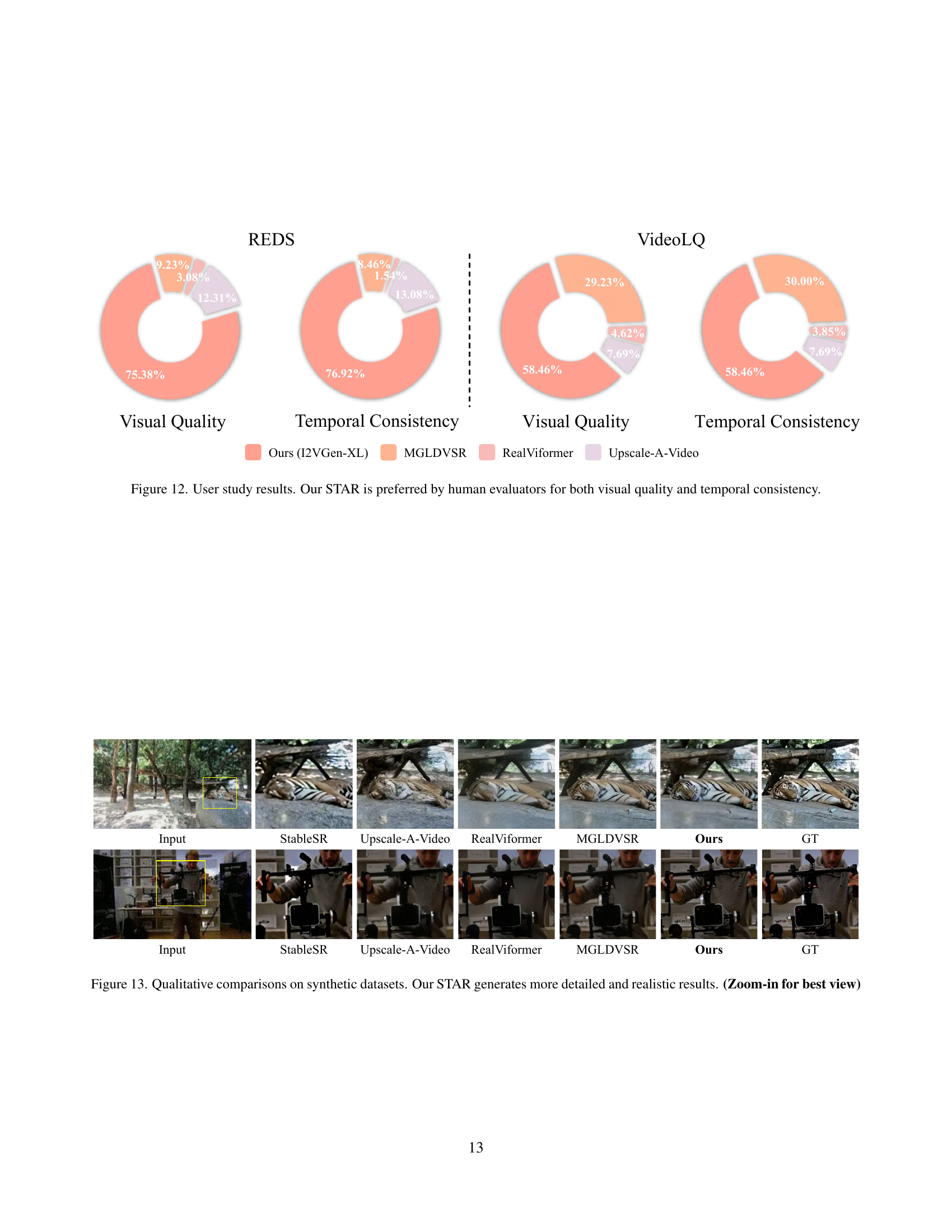

🔼 A user study was conducted to compare the visual quality and temporal consistency of video super-resolution results generated by STAR against other state-of-the-art methods. Human evaluators were asked to choose the best results based on these two criteria from a set of options including STAR and competing methods. The pie charts show that a significant majority of evaluators preferred STAR’s output for both visual quality and temporal consistency across both synthetic and real-world datasets.

read the caption

Figure 12: User study results. Our STAR is preferred by human evaluators for both visual quality and temporal consistency.

🔼 Figure 13 presents a qualitative comparison of video super-resolution (VSR) results on synthetic datasets. It visually showcases the outputs of several state-of-the-art VSR methods alongside the results generated by the STAR model. The comparison highlights that STAR produces significantly more detailed and realistic results compared to the other methods, demonstrating its superior performance in restoring fine details and textures within the video frames. The ‘Zoom-in for best view’ notation indicates that the details of the results are best appreciated at higher magnification.

read the caption

Figure 13: Qualitative comparisons on synthetic datasets. Our STAR generates more detailed and realistic results. (Zoom-in for best view)

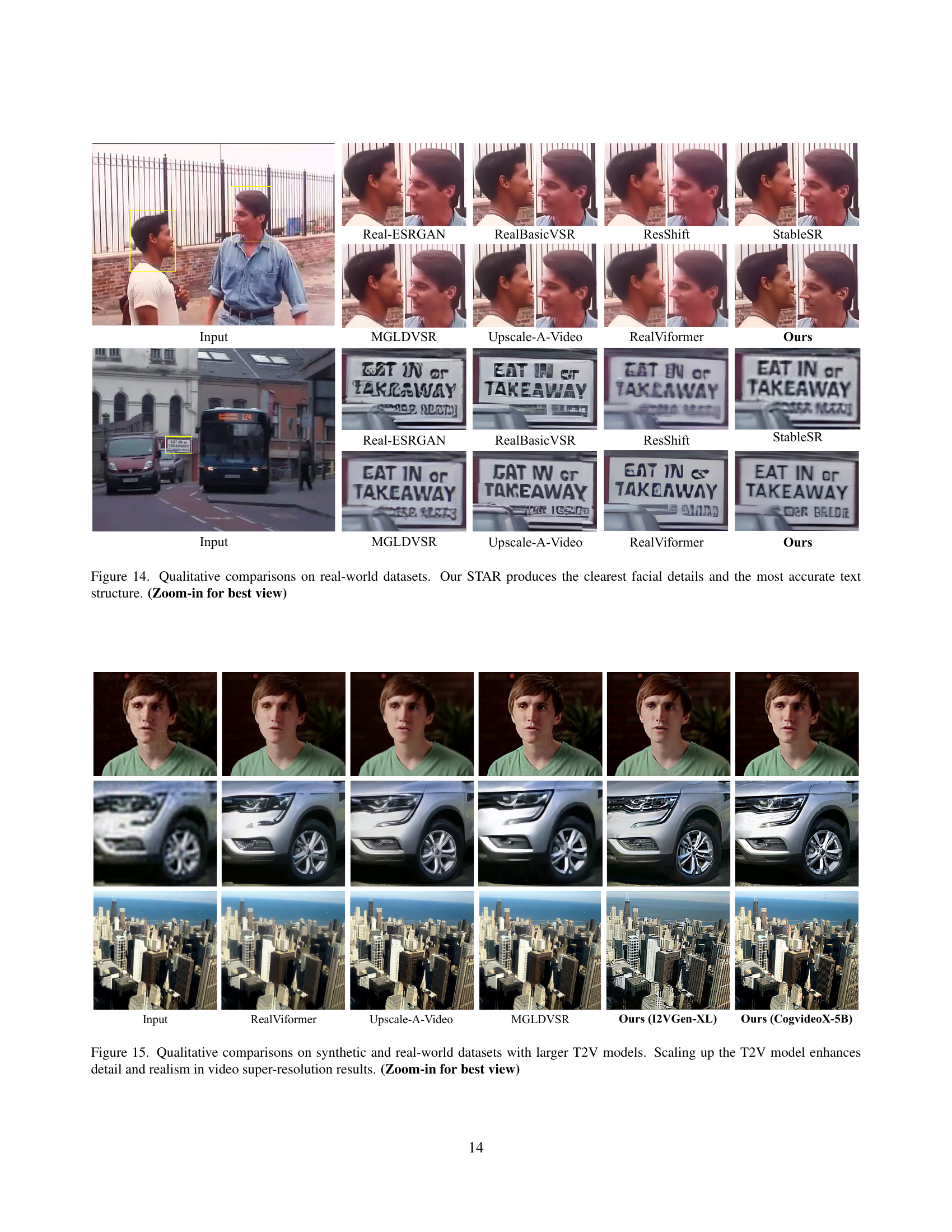

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of different video super-resolution (VSR) methods on real-world datasets. It showcases the results of several state-of-the-art VSR models, including Real-ESRGAN, RealBasicVSR, ResShift, StableSR, MGLDVSR, Upscale-A-Video, RealViformer, and the proposed STAR method. Each model’s output is displayed alongside the input low-resolution video and the ground truth high-resolution video. The comparison highlights STAR’s superior performance in restoring fine details, particularly in facial features and text, demonstrating its enhanced ability to reconstruct clear, sharp images from real-world low-resolution inputs.

read the caption

Figure 14: Qualitative comparisons on real-world datasets. Our STAR produces the clearest facial details and the most accurate text structure. (Zoom-in for best view)

More on tables

| Method | Dataset | Size | #Frames | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV[75] | WebVid[2] + YouHQ[75] | 335K+37K | - | 336×596, 1080×1920 |

| RealViformer[73] | REDS[35] | 300K | 100 | 720×1280 |

| Ours | OpenVid[36] | 200K | 32 | 720×1280 |

🔼 This table compares the training datasets used in different video super-resolution (VSR) models. It shows the dataset name, its size (number of video clips and frames), and the resolution of the videos. The information allows for a comparison of the scale and quality of training data used across various models, providing insight into potential differences in performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Training dataset comparison.

| Position | Spa-Local | Temp-Local | PSNR ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | E*warp ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (i) | 23.14 | 0.2015 | 2.83 | ||

| ✓ | 23.61 | 0.2013 | 2.82 | ||

| ✓ | 23.65 | 0.1945 | 2.92 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 23.69 | 0.1943 | 2.74 | |

| (ii) | 23.27 | 0.2363 | 3.57 | ||

| (iii) | 24.51 | 0.2094 | 1.99 |

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the placement of the Local Information Enhancement Module (LIEM) within the STAR model architecture. It shows the impact of placing LIEM at different positions within the model on the performance metrics of PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), and Ewarp (flow warping error). The results demonstrate which LIEM placement provides the best performance across these metrics for real-world video super-resolution.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation of LIEM position.

| Seperate | Type | PSNR ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | E*warp ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o Frequency Loss | 23.69 | 0.1943 | 2.74 | |

| - | - | 23.72 | 0.1941 | 2.71 |

| ✓ | Inverse | 23.67 | 0.1945 | 2.83 |

| ✓ | Direct | 23.85 | 0.1903 | 2.69 |

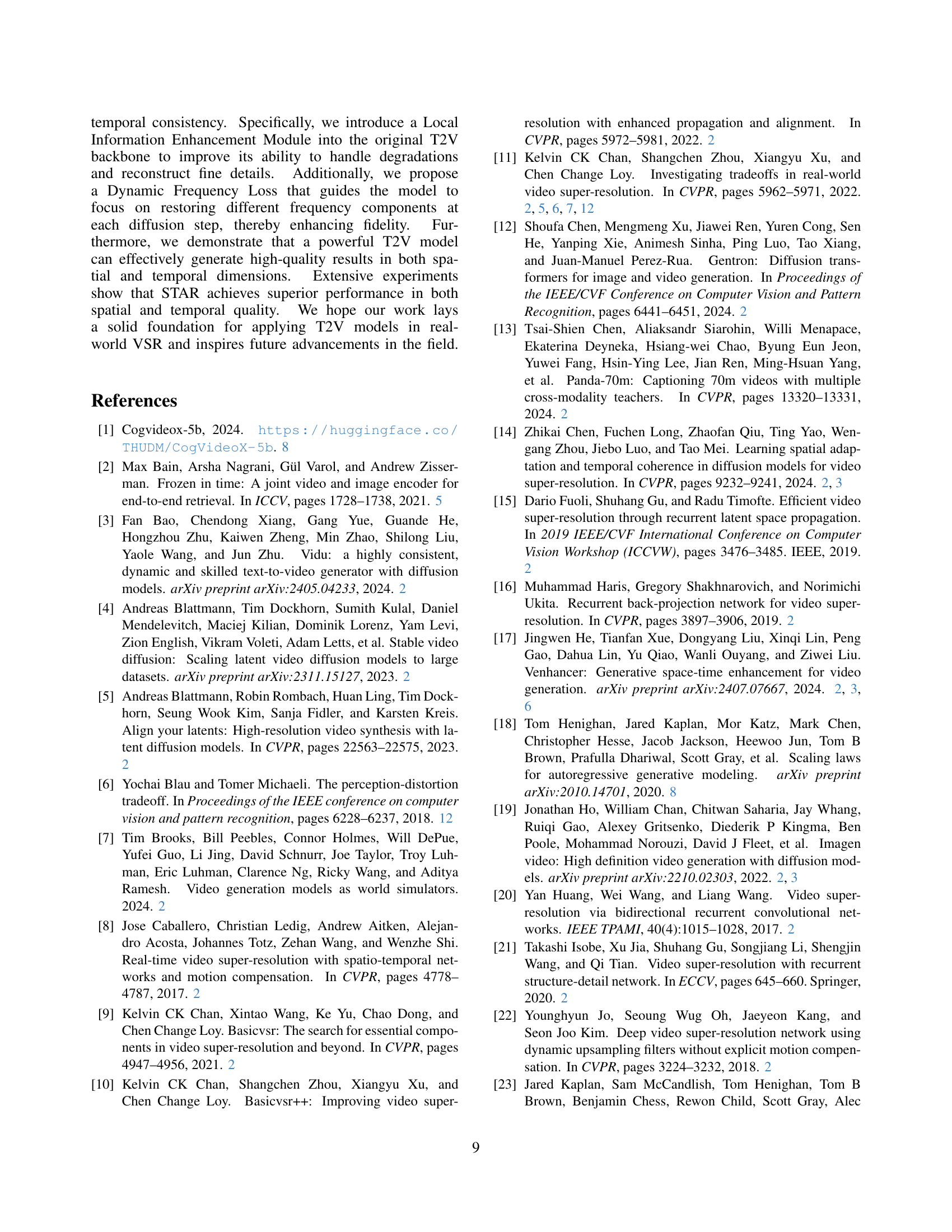

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the Dynamic Frequency (DF) Loss, a key component of the STAR model. It shows how different variations in the DF Loss affect the performance of the model in terms of PSNR, LPIPS, and Ewarp metrics. The variations explored include whether low and high frequencies are separated, and the type of weighting function used (inverse or direct). This helps in understanding the individual contribution of each component of the DF loss to the overall performance of the model.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation of different variants of DF loss.

| b(t) | α | PSNR ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | E*warp ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | 0.25 | 23.76 | 0.2030 | 2.72 |

| 0.5 | 23.71 | 0.2010 | 2.75 | |

| 1 | 23.85 | 0.1903 | 2.69 | |

| 1.5 | 23.53 | 0.1928 | 2.81 | |

| 2 | 23.91 | 0.1885 | 2.61 | |

| Exponential | 23.68 | 0.1990 | 2.78 |

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies on the hyperparameters b(t) and α in the Dynamic Frequency Loss function of the STAR model. It shows how changes to these parameters affect the PSNR, LPIPS, and Ewarp metrics, which measure the performance of the video super-resolution model. Different values of b(t) and α were tested with both linear and exponential functions to determine their individual and combined effects on the model’s overall performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation of b(t)𝑏𝑡b(t)italic_b ( italic_t ) and α𝛼\alphaitalic_α in c(t)𝑐𝑡c(t)italic_c ( italic_t ).

| Metrics | UAV | RealViformer | Ours (I2VGen-XL) | Ours (CogX-2B) | Ours (CogX-5B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR ↑ | 22.46 | 22.90 | 21.46 | 23.18 | 23.60 |

| SSIM ↑ | 0.6552 | 0.6944 | 0.6715 | 0.7112 | 0.7400 |

| LPIPS ↓ | 0.2035 | 0.1823 | 0.1779 | 0.1571 | 0.1314 |

| DOVER ↑ | 0.6609 | 0.4286 | 0.7267 | 0.6955 | 0.7350 |

| E*warp ↓ | 5.424 | 4.75 | 5.529 | 3.68 | 4.56 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of video super-resolution (VSR) results using different text-to-video (T2V) diffusion models. It shows the effectiveness of incorporating T2V priors into a real-world VSR framework by comparing the performance metrics (PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, DOVER, and Ewarp) of various models. The metrics evaluate image quality, perceptual similarity, video clarity, and temporal consistency. The models compared include a baseline (I2VGen-XL), and several larger models (CogVideoX variants) to demonstrate the impact of model size and power on VSR performance.

read the caption

Table 6: Effectiveness of T2V diffusion prior for real-world VSR.

| β | PSNR ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | E*warp ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 23.55 | 0.1825 | 2.88 |

| 0.75 | 23.76 | 0.1842 | 2.74 |

| 1.0 | 23.91 | 0.1885 | 2.68 |

| 1.5 | 24.08 | 0.2272 | 2.53 |

| 2.0 | 24.41 | 0.3339 | 2.21 |

🔼 This table presents a qualitative comparison of the results obtained using different values for the hyperparameter (\beta) in the weighting function (b(t)). The (\beta) parameter controls the balance between the velocity prediction loss and the dynamic frequency loss in the optimization process. Different values of (\beta) lead to varying degrees of emphasis on fidelity and perceptual quality in the reconstructed videos. The table shows the PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), and Ewarp (flow warping error) metrics for several values of (\beta), allowing for an assessment of the trade-off between perceptual quality and fidelity in the generated results.

read the caption

Table 7: Qualitative comparison under different β𝛽\betaitalic_β of b(t)𝑏𝑡b(t)italic_b ( italic_t ).

Full paper#