↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current proprietary large language models (LLMs) raise significant privacy concerns. Private inference (PI) is a promising solution, but it struggles with high communication and latency overheads, mostly due to nonlinear operations within transformer architectures. These nonlinearities are crucial for model stability and attention head diversity, and removing them leads to training instability and underutilization of attention’s representational capacity.

This paper proposes solutions to overcome these issues. It introduces an entropy-guided attention mechanism along with a novel entropy regularization technique. The approach dynamically adjusts regularization strength for individual attention heads and mitigates ’entropic overload’. Additionally, PI-friendly layer normalization alternatives prevent ’entropy collapse’ and improve training stability in LLMs with fewer nonlinearities. Experiments on various datasets demonstrate significant improvements in both efficiency and model performance. The paper offers a principled framework for designing efficient and private LLMs, advancing the field of privacy-preserving AI.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in private AI, machine learning, and information theory. It offers a novel entropy-guided framework for designing efficient and privacy-preserving LLMs. By addressing the challenges of nonlinear operations in private inference, it opens avenues for improving the efficiency and security of large language models, impacting numerous applications requiring privacy-sensitive computations.

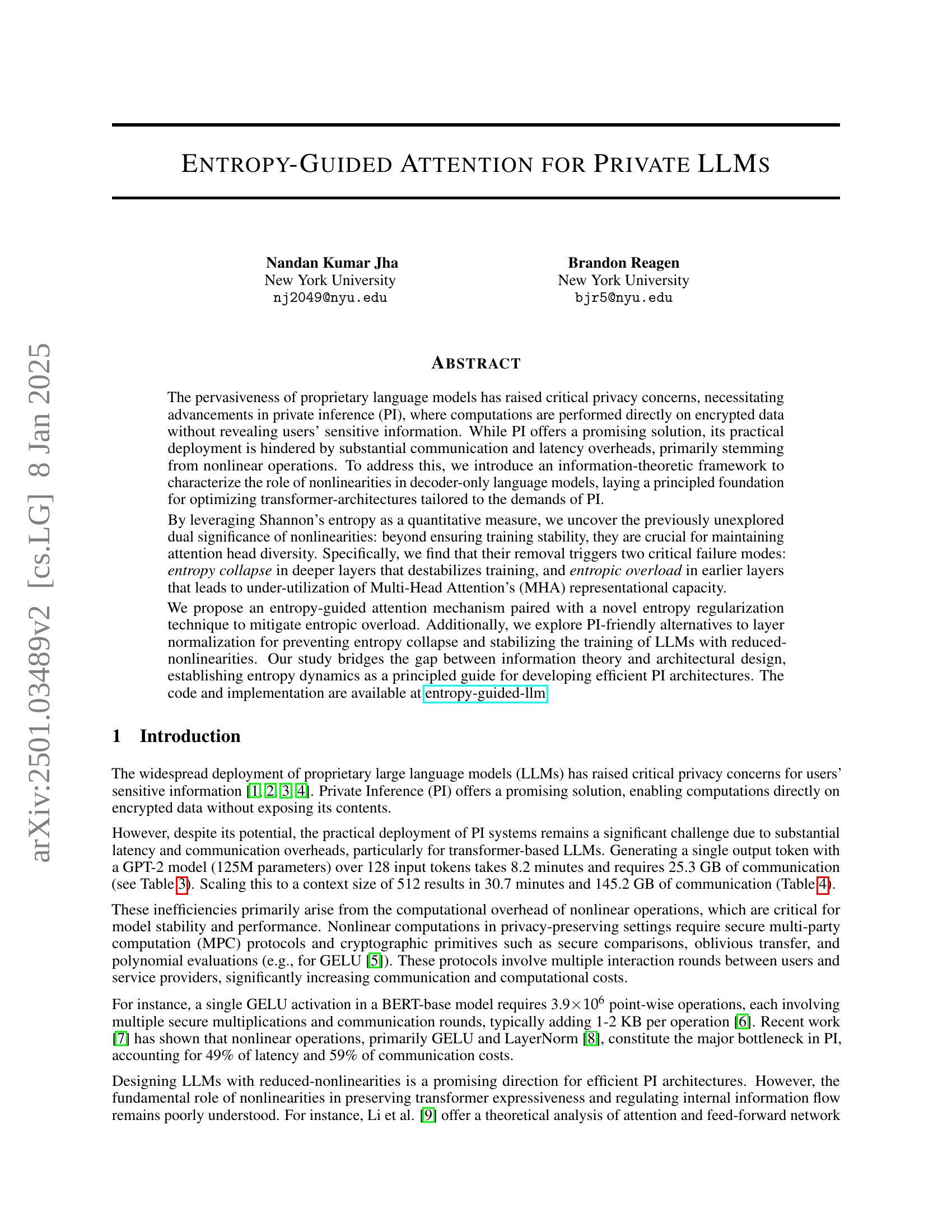

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the threat model and cryptographic protocols employed in private inference (PI) for large language models (LLMs). The threat model depicts a two-party computation scenario where a client (user) sends encrypted input to a server (model provider). The server processes the encrypted data and returns the encrypted output to the client without revealing either party’s private information. The figure also showcases the cryptographic protocols used to achieve this secure computation. This ensures that only the final results are obtained, without revealing the client’s data or the server’s model parameters.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of threat model and cryptographic protocols used for LLM private inference.

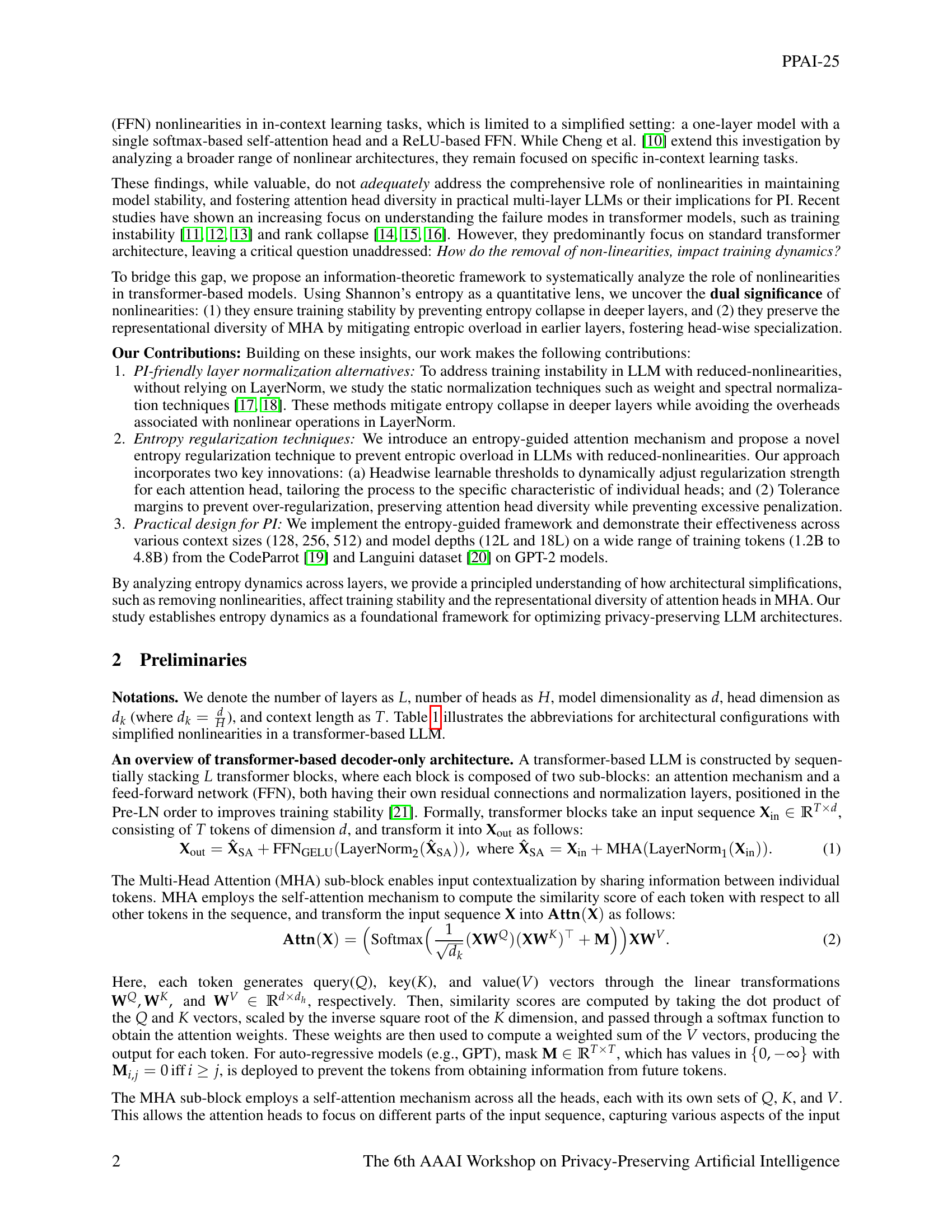

| Abbreviation | Architectural configuration | |

|---|---|---|

| SM + LN + G | \mathbf{X}{\text{out}}=\text{FFN}{\text{GELU}}(\text{LayerNorm}{2}(\text{MHA}(\text{Attn}{\text{Softmax}}(\text{LayerNorm}{1}(\mathbf{X}{\text{in}}))))) | |

| SM + LN + R | \mathbf{X}{\text{out}}=\text{FFN}{\text{ReLU}}(\text{LayerNorm}{2}(\text{MHA}(\text{Attn}{\text{Softmax}}(\text{LayerNorm}{1}(\mathbf{X}{\text{in}}))))) | |

| SM + LN | \mathbf{X}{\text{out}}=\text{FFN}{\text{Identity}}(\text{LayerNorm}{2}(\text{MHA}(\text{Attn}{\text{Softmax}}(\text{LayerNorm}{1}(\mathbf{X}{\text{in}}))))) | |

| SM + G | \mathbf{X}{\text{out}}=\text{FFN}{\text{GELU}}(\text{MHA}(\text{Attn}{\text{Softmax}}(\mathbf{X}{\text{in}}))) | |

| SM + R | \mathbf{X}{\text{out}}=\text{FFN}{\text{ReLU}}(\text{MHA}(\text{Attn}{\text{Softmax}}(\mathbf{X}{\text{in}}))) | |

| SM | \mathbf{X}{\text{out}}=\text{FFN}{\text{Identity}}(\text{MHA}(\text{Attn}{\text{Softmax}}(\mathbf{X}{\text{in}}))) |

🔼 This table presents various architectural configurations for Large Language Models (LLMs) focusing on the impact of different combinations of non-linear activation functions on model performance. It shows how the choice of Softmax (SM), LayerNorm (LN), GELU (G), and ReLU (R) affects the overall architecture, and specifically how these components are combined in equations 1, 2, 3 and 4. This allows researchers to analyze and compare LLMs with various levels of nonlinearity.

read the caption

Table 1: Architectural configurations of nonlinearities in LLMs, illustrating the combinations of Softmax (SM), LayerNorm (LN), GELU (G), and ReLU (R) functions (see Eq. 1, 2, 3 and 4).

In-depth insights#

Private LLMs#

The concept of “Private LLMs” addresses the crucial issue of privacy in the context of large language models. It highlights the need for techniques that allow computations on encrypted data without revealing sensitive user information. Private Inference (PI) is presented as a key solution, but it faces challenges like substantial communication and latency overheads, primarily from nonlinear operations. The research explores the use of information theory, specifically Shannon’s entropy, to analyze the role of nonlinearities in transformer architectures, revealing their importance beyond training stability. The research proposes methods to create PI-friendly LLMs by mitigating issues such as entropy collapse and entropic overload, suggesting entropy-guided attention as a technique to improve efficiency and privacy.

Entropy Dynamics#

The concept of ‘Entropy Dynamics’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) offers a powerful lens for understanding the internal information flow and training stability. Entropy, a measure of uncertainty, provides insights into how attention mechanisms function and how the removal of non-linearities impacts model behavior. High entropy in early layers suggests underutilization of attention heads, a phenomenon termed ’entropic overload,’ whereas low entropy in deeper layers leads to training instability (’entropy collapse’). The research likely explores how entropy changes across layers and attention heads during training. By analyzing these dynamics, the authors can identify optimal levels of non-linearity for efficient and private inference. This involves a delicate balance – insufficient non-linearities lead to instability, while excessive non-linearities incur high communication costs. The study likely proposes novel entropy-guided attention mechanisms and layer normalization alternatives to address these issues. The goal is to create efficient architectures with reduced non-linearities that maintain training stability and attention head diversity. This approach combines information theory with architectural design, opening promising avenues for enhancing privacy-preserving LLMs.

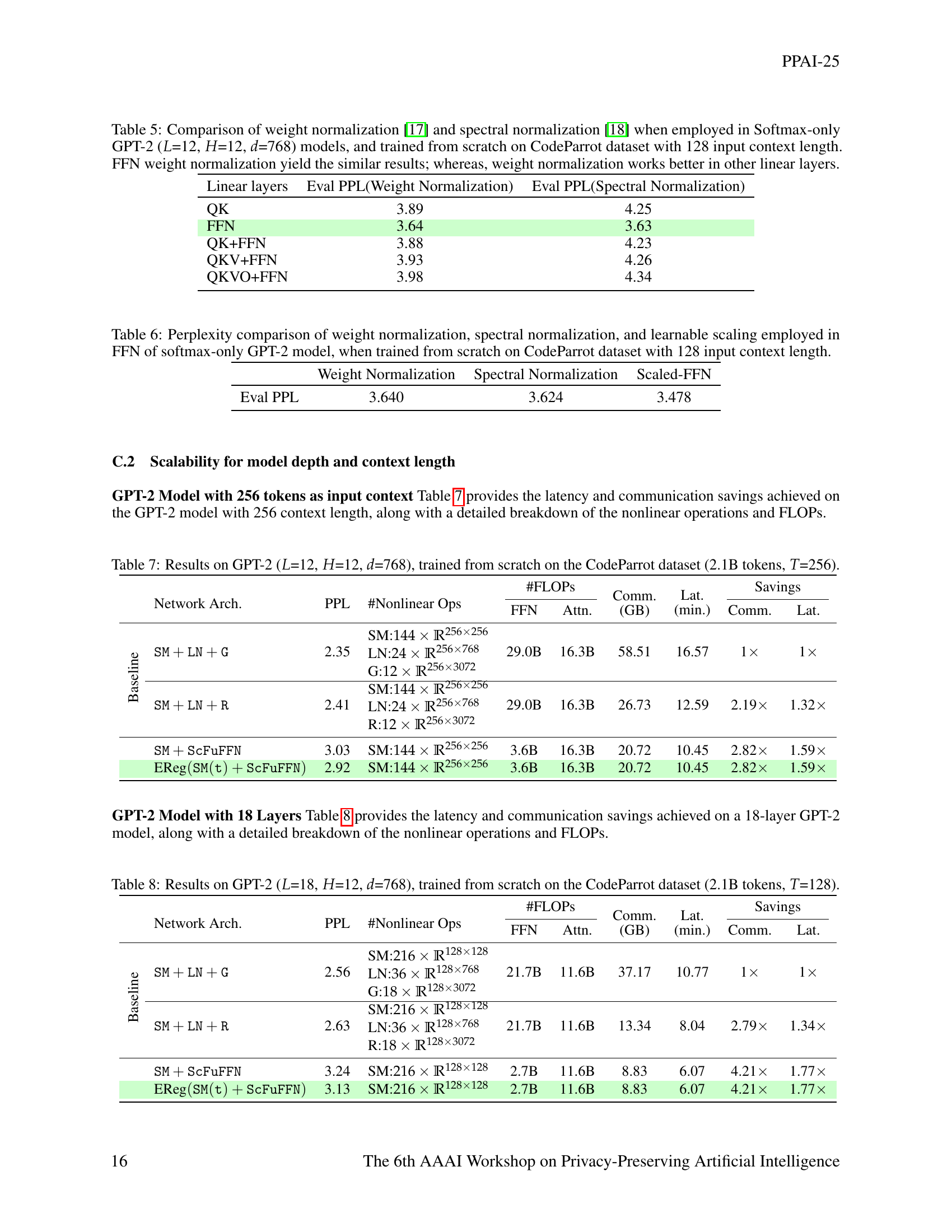

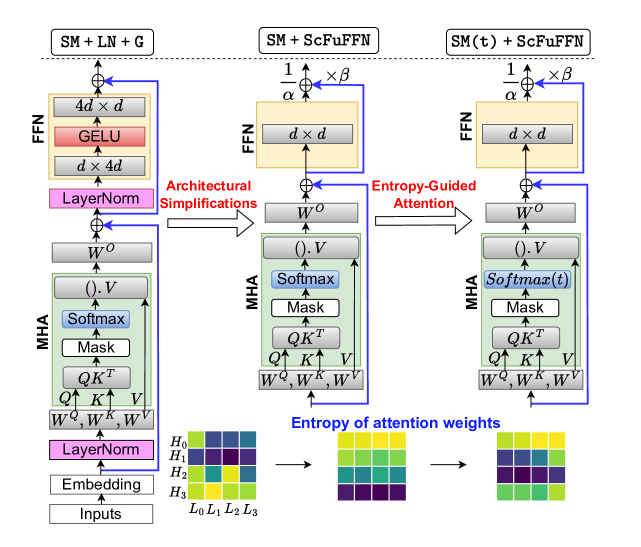

PI-Friendly Normalization#

Private inference (PI) systems for large language models (LLMs) face significant challenges due to the computational overhead of normalization layers, particularly LayerNorm. This necessitates the exploration of PI-friendly normalization alternatives that reduce latency and communication costs without sacrificing model performance. The paper investigates static normalization techniques, such as weight and spectral normalization, as replacements for LayerNorm. These methods avoid the computationally expensive operations of LayerNorm, making them suitable for PI. Weight and spectral normalization effectively mitigate entropy collapse, a common issue when reducing nonlinearities in LLMs, by normalizing weights rather than activations. The effectiveness of these methods depends on their placement within the model architecture; the study explores optimal locations within the attention and feedforward network (FFN) sub-blocks. A key finding is that applying weight normalization or spectral normalization in the FFN layers yields comparable or better results than applying it to the attention layers. The study further investigates a simpler technique of scaling FFN outputs using learnable scaling factors, demonstrating promising results in maintaining training stability and achieving lower perplexity. Overall, the exploration of PI-friendly normalization highlights a crucial aspect of optimizing LLM architectures for private inference, emphasizing the trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance.

Entropy Regularization#

The concept of ‘Entropy Regularization’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) focuses on managing the distribution of attention weights within the attention mechanism. High entropy signifies a uniform distribution, where attention is spread thinly across many tokens, while low entropy indicates a focused distribution on a few key tokens. The authors introduce an entropy regularization technique to prevent two critical failure modes: ’entropy collapse’ in deeper layers (resulting in training instability) and ’entropic overload’ in shallower layers (leading to underutilization of attention heads). This technique uses learnable thresholds for each attention head, allowing the model to adapt regularization strength dynamically. A tolerance margin prevents over-regularization and maintains diversity. The effectiveness is demonstrated by improved perplexity and training stability in experiments across different model sizes and datasets, showcasing the importance of balancing entropy for optimal LLM performance and privacy.

Future of PI#

The future of Private Inference (PI) in large language models (LLMs) hinges on addressing the inherent trade-offs between privacy, efficiency, and model performance. Reducing the reliance on computationally expensive nonlinear operations is crucial, as these form a major bottleneck in PI systems. This could involve exploring alternative architectures and training methodologies that minimize or eliminate nonlinearities while preserving model expressiveness. Further research into the fundamental role of nonlinearities is essential to guide the design of more efficient PI architectures. An information-theoretic approach, utilizing concepts like entropy, offers a promising avenue for understanding and optimizing attention mechanisms within the context of PI. Developing more sophisticated entropy regularization techniques and exploring novel methods for mitigating entropic overload will be key. The development of PI-friendly layer normalization alternatives is important to ensure training stability in models with reduced nonlinearities. Finally, scalability is a critical aspect for the future success of PI; addressing the challenges of deploying PI systems to very large LLMs and diverse datasets is paramount.

More visual insights#

More on figures

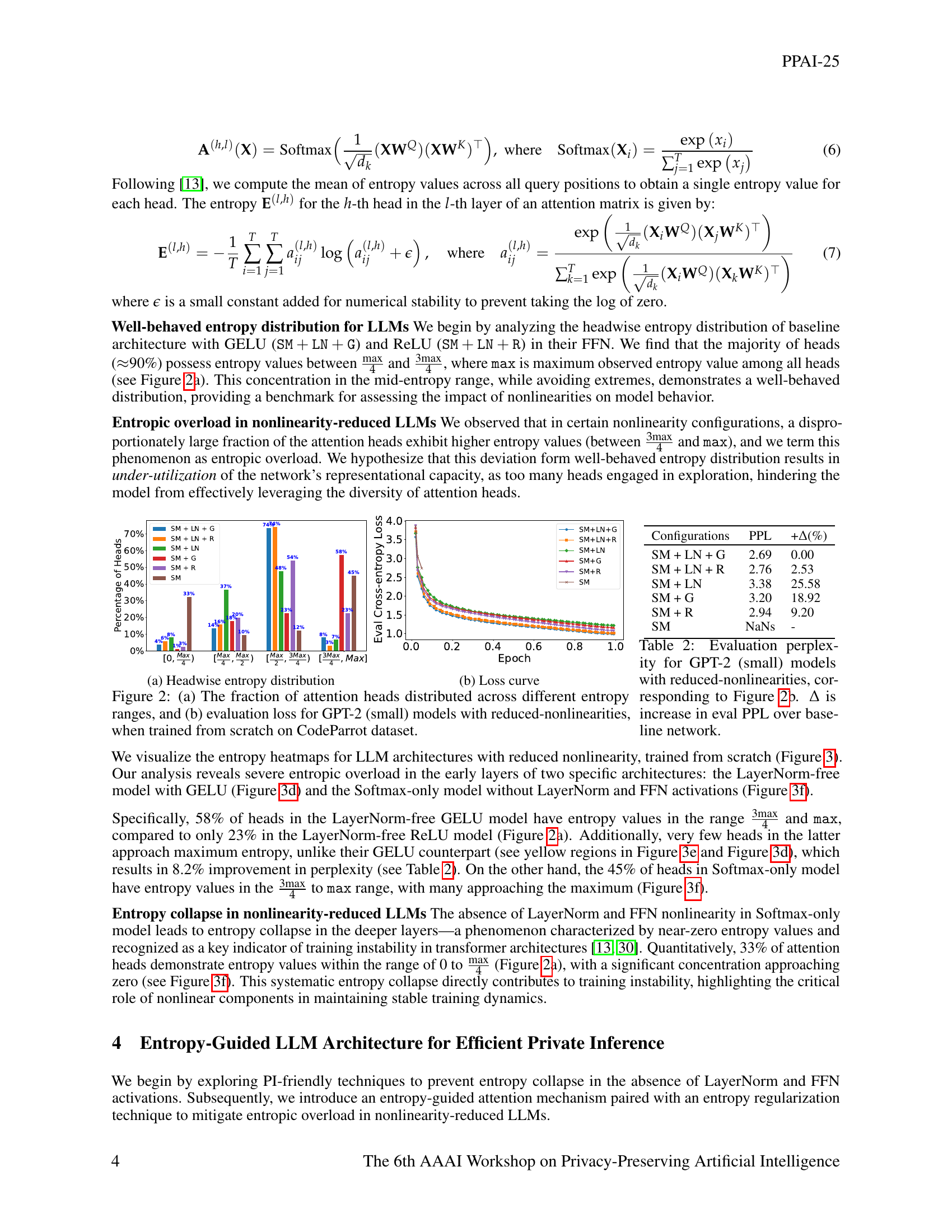

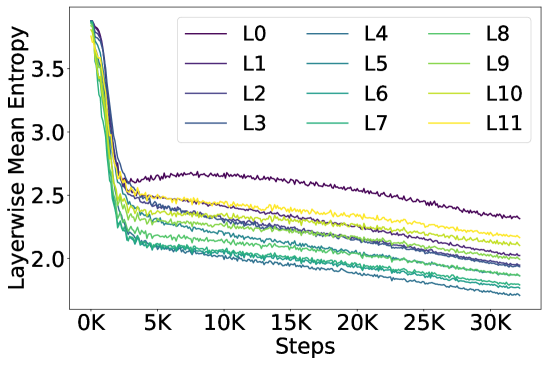

🔼 This figure shows the layerwise mean entropy distribution for a GPT-2 model (small) with the baseline architecture (Softmax, Layer Normalization, and GELU activation). The y-axis represents the mean entropy, while the x-axis indicates the head index. Each line represents the entropy for a specific layer, providing a visual representation of how entropy changes across layers and heads in this standard model.

read the caption

(a) SM + LN + G

🔼 This figure shows the headwise entropy distribution for a GPT-2 small model (with 12 layers and 12 heads) trained on the CodeParrot dataset. Specifically, it displays the percentage of attention heads exhibiting different ranges of entropy values, broken down into four entropy intervals: [0, max), [max, max), [max, 3max), and [3max, max]. The figure helps to visualize the impact of using the ReLU activation function within the feed-forward network (FFN) of the transformer architecture. It demonstrates the distribution of attention weights among heads in a model using the softmax activation function, layer normalization and ReLU in the feed-forward network.

read the caption

(b) SM + LN + R

🔼 This figure shows the layer-wise entropy distribution across different attention heads for a Softmax + LayerNorm model. It’s part of an analysis comparing entropy distributions across various architectures of Language Models, with and without nonlinearities. Specifically, this sub-figure displays the heatmap visualization of entropy values for the specified model, enabling a direct comparison to other models’ behavior shown in other subfigures. The heatmap reveals the entropy pattern for each head across the model’s layers; darker shades generally mean lower entropy while brighter shades mean higher entropy. It illustrates headwise entropy dynamics in a model with standard nonlinearities, providing a baseline for evaluating the effects of removing nonlinearities or using different normalization methods.

read the caption

(c) SM + LN

🔼 This figure displays the headwise entropy distribution in a language model architecture with reduced nonlinearities. Specifically, it shows the entropy values for each attention head across different layers (indicated by the y-axis) of the model using the softmax activation function and the GELU activation function (SM+G). Each column in the heatmap represents a different attention head, showing how the entropy of each head varies over the layers. The color intensity represents the entropy value, with higher intensity indicating higher entropy. The figure visualizes the entropy dynamics in the model to demonstrate that removing nonlinearities (particularly LayerNorm) leads to an issue called ’entropic overload’ in early layers, causing some attention heads to use the full representational capacity and underutilize the diversity of the model’s attention heads.

read the caption

(d) SM + G

🔼 This figure shows a heatmap visualization of the entropy distribution across different attention heads in various layers of a language model with a simplified architecture. Specifically, it presents the entropy values for each head in the model that uses only softmax activation function (SM) and ReLU activation function (R) in the feed-forward network (FFN). The heatmap allows for a visual inspection of the entropy distribution across layers and heads and is useful for identifying potential issues such as entropy overload (high entropy values in earlier layers) or entropy collapse (low entropy values in deeper layers), which may negatively affect the model’s performance. The y-axis represents the layer index, and the x-axis represents the head index. The color intensity of each cell in the heatmap reflects the entropy value for the corresponding layer and head, with darker colors indicating higher entropy. The caption (e) SM + R indicates that the figure corresponds to a model architecture without LayerNorm.

read the caption

(e) SM + R

🔼 This figure shows the headwise entropy distribution across different layers for a Softmax-only model (no LayerNorm or FFN nonlinearities). It demonstrates the phenomenon of entropy collapse in the deeper layers, where entropy values approach zero, indicating instability. This contrasts with baseline models that exhibit a well-behaved entropy distribution. The entropy heatmap visually represents the entropy of attention heads across layers and heads, highlighting the regions of low and high entropy.

read the caption

(f) SM

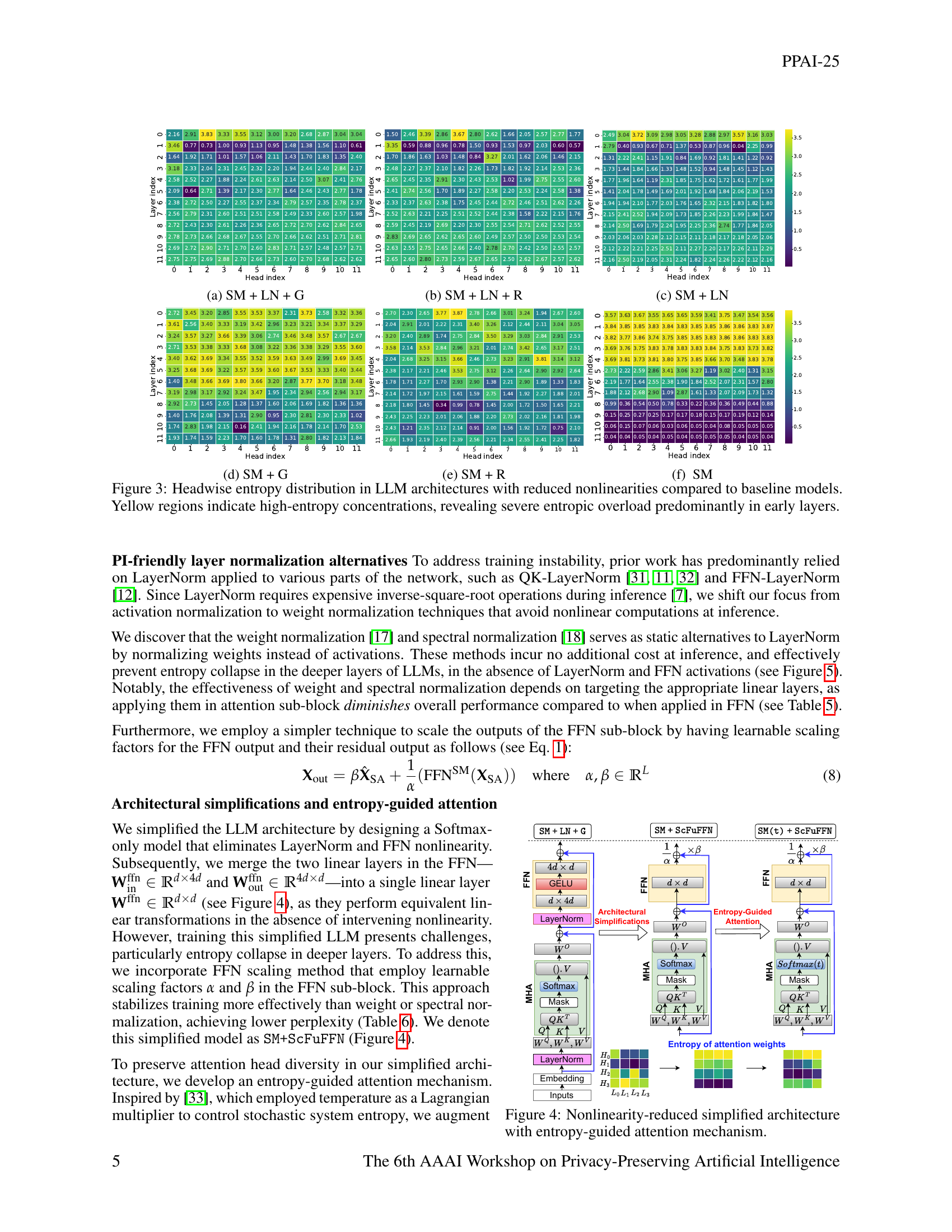

🔼 This figure visualizes the distribution of entropy across different attention heads in various layers of several Large Language Models (LLMs). Each LLM has varying degrees of nonlinearities (nonlinear activation functions), ranging from a full set of nonlinearities to models with most nonlinearities removed. The color of each cell represents the entropy value for a given attention head in a specific layer. Yellow indicates high entropy values, suggesting that the attention mechanism is not focusing effectively on a subset of features, but rather is distributing attention widely. This phenomenon is called ’entropic overload’ and is observed primarily in the earlier layers of the LLMs with fewer nonlinearities. Conversely, models with nonlinearities exhibit a more focused distribution of attention, represented by lower entropy. This demonstrates the importance of nonlinearities in regulating attention distribution and preventing entropic overload.

read the caption

Figure 2: Headwise entropy distribution in LLM architectures with reduced nonlinearities compared to baseline models. Yellow regions indicate high-entropy concentrations, revealing severe entropic overload predominantly in early layers.

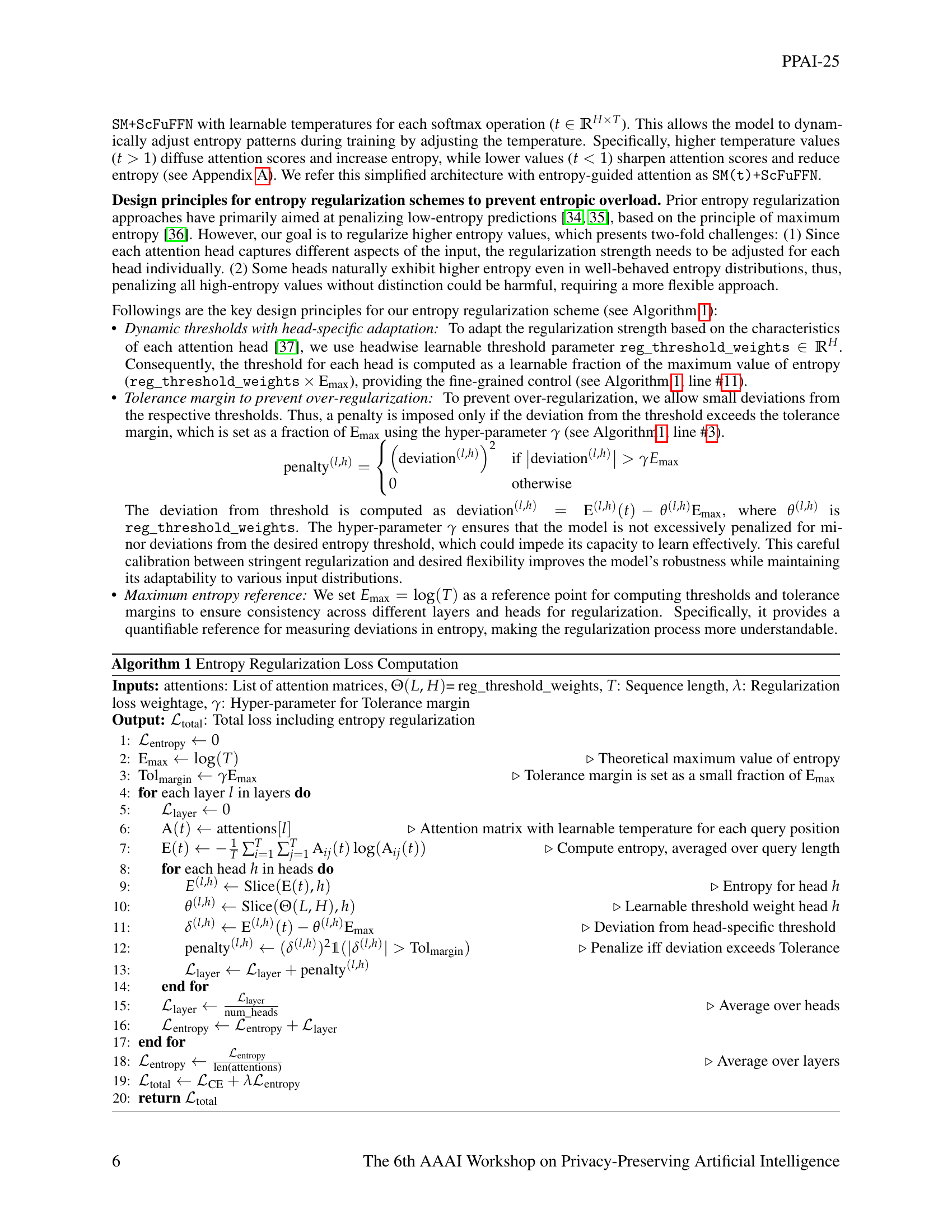

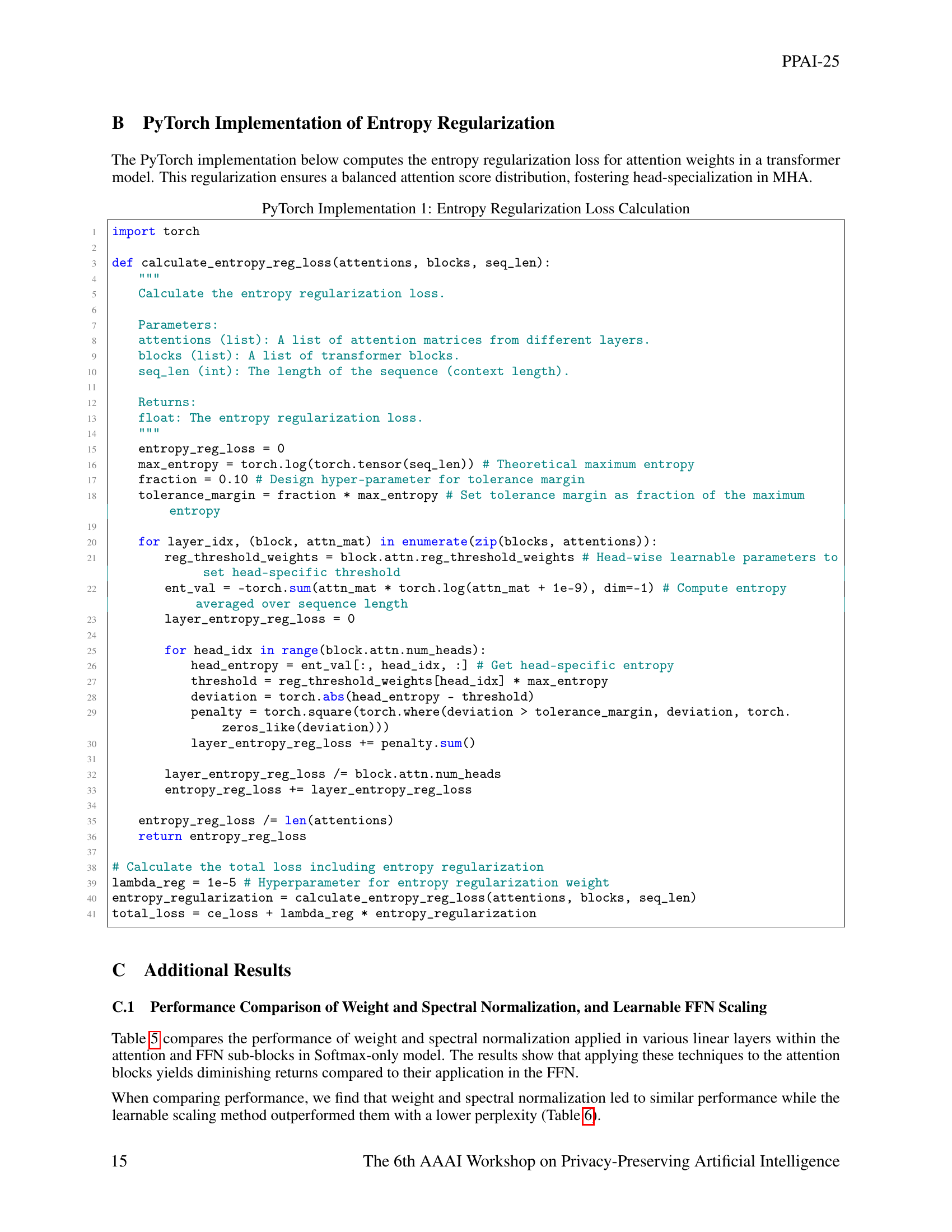

🔼 This figure illustrates the simplified architecture of a large language model (LLM) designed for efficient private inference. It shows how the model’s architecture has been modified to reduce reliance on non-linear operations, which are computationally expensive in privacy-preserving settings. The key modification is the incorporation of an ’entropy-guided attention mechanism’, which helps control the distribution of attention weights. This mechanism, which leverages a learnable temperature to regulate entropy, aims to improve model efficiency and stability while maintaining performance by focusing attention on the most relevant parts of the input sequence. The figure visually details the individual components of this simplified architecture, highlighting the interactions and flow of information between them.

read the caption

Figure 3: Nonlinearity-reduced simplified architecture with entropy-guided attention mechanism.

🔼 This figure shows the layer-wise mean entropy for the baseline GPT-2 model with Softmax, Layer Normalization, and GELU activation functions (SM + LN + G). The x-axis represents the head index (0-11), and the y-axis represents the layer index (0-11). Each cell displays the average entropy value across all query positions for a given head and layer. The colormap visualizes the entropy values, with darker shades indicating lower entropy (more focused attention) and lighter shades indicating higher entropy (more uniform attention). This figure helps visualize the entropy distribution across different attention heads and layers in a well-trained model, serving as a baseline for comparison with models having different architectures.

read the caption

(a) SM + LN + G

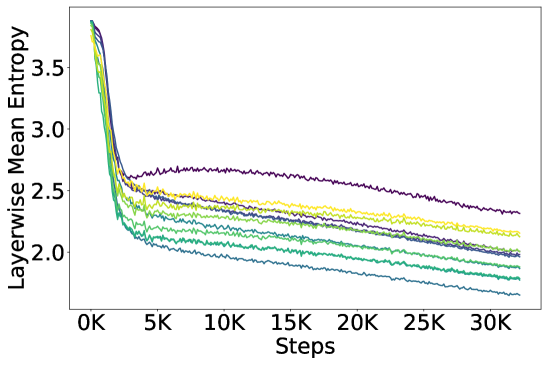

🔼 This figure displays the layer-wise mean entropy for the Softmax-only (SM) model architecture in GPT-2 models, trained from scratch on the CodeParrot dataset. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis shows the mean entropy across the different layers. The multiple colored lines represent different layers in the model. The plot illustrates the entropy dynamics across training steps within each model layer and reveals the entropy collapse and entropic overload issues associated with this simplified architecture.

read the caption

(b) SM

🔼 This figure shows the layerwise mean entropy patterns in a GPT-2 model (12 layers, 12 heads, dimensionality 768) during training. The model uses only the softmax activation function (SM) and employs weight normalization specifically on the feed-forward network (FFN) layer. The plot illustrates how entropy changes across different layers (from L0 to L11) over the training steps. It helps visualize the effectiveness of weight normalization in mitigating entropy collapse and potentially improving the stability and performance of the model.

read the caption

(c) SM + WeightNormalization(FFN)

🔼 This figure shows the layer-wise entropy patterns observed in a GPT-2 model (12 layers, 12 heads, 768 dimensions) trained from scratch on the CodeParrot dataset. This specific visualization focuses on the architecture where only the softmax activation is used, and the feed-forward network (FFN) employs spectral normalization. The plot displays the average entropy across all heads within each layer of the model, indicating the distribution of attention scores. The entropy values represent the uncertainty or spread of the attention weights. A low entropy implies that attention is focused on a small set of tokens, while a high entropy suggests more evenly distributed attention.

read the caption

(d) SM + SpectralNormalization(FFN)

🔼 This figure shows the layer-wise entropy patterns in a GPT-2 model (with 12 layers, 12 heads, and a dimensionality of 768) trained from scratch on the CodeParrot dataset. Specifically, it illustrates the entropy distribution across different layers (Layer 0-11) and shows the impact of using a scaled feed-forward network (FFN) within the Softmax-only architecture (SM). The scaled FFN approach is a technique employed to mitigate the training instabilities and issues caused by the removal of nonlinearities typically seen in more complex transformer models. The visualization in this sub-figure allows comparison with other models and techniques explored in the paper for handling entropy dynamics within the transformer architecture.

read the caption

(e) SM + Scaled(FFN)

🔼 This figure shows the layer-wise mean entropy patterns in a GPT-2 model (12 layers, 12 heads, dimensionality 768) trained on the CodeParrot dataset. Specifically, it displays the entropy dynamics for the architecture denoted as ‘EntropyReg(SM(t)+ScFuFFN)’, which represents a Softmax-only model (no LayerNorm or FFN nonlinearities) that incorporates an entropy regularization technique and a learnable temperature for each softmax operation. This method aims to mitigate both entropic overload (excessive entropy in early layers) and entropy collapse (near-zero entropy in deeper layers). The plot helps visualize how effectively this approach manages entropy across layers and heads, promoting more balanced attention distributions.

read the caption

(f) EntropyReg(SM(t)+ScFuFFN)

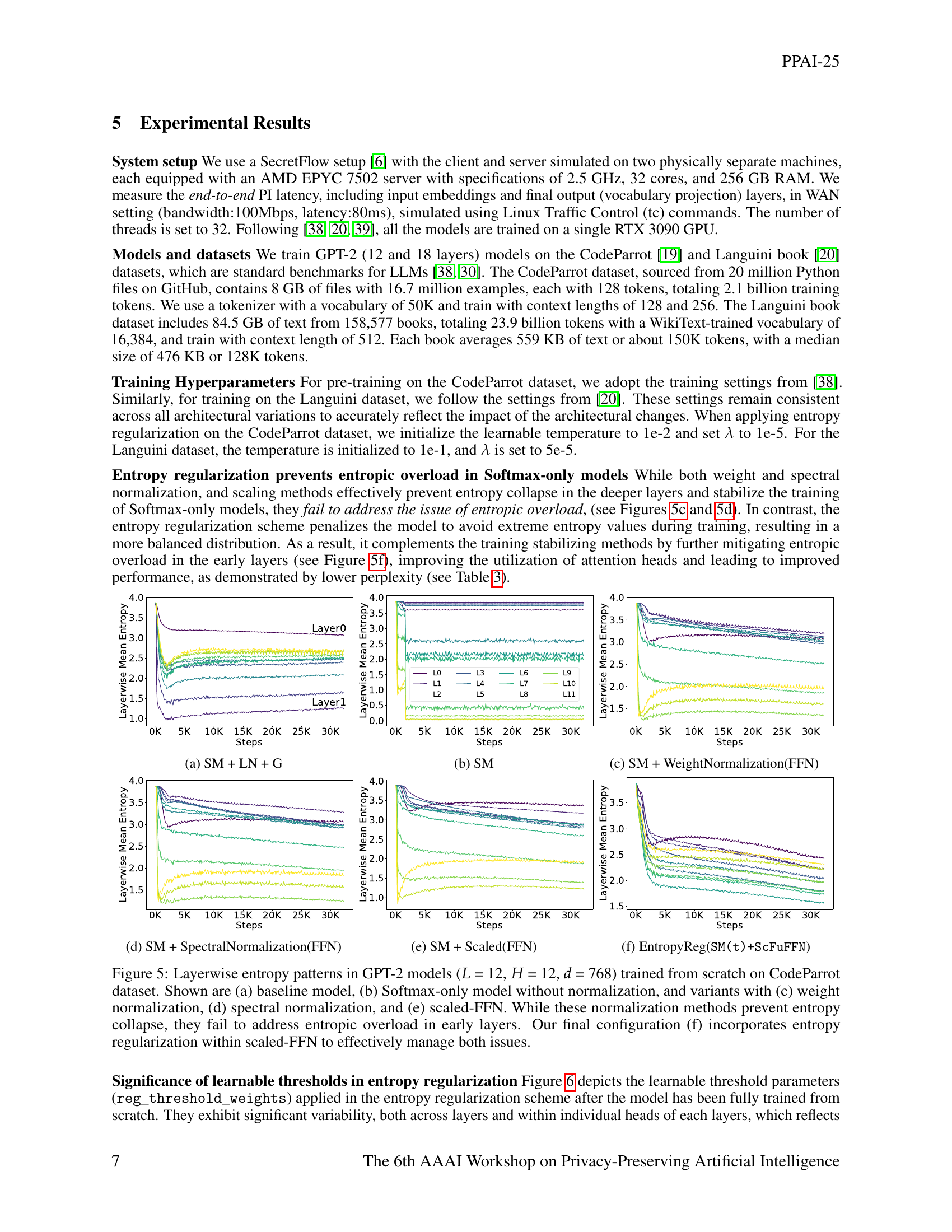

🔼 This figure displays the layerwise entropy patterns observed in various GPT-2 model configurations trained on the CodeParrot dataset. The models are compared across several variations: a baseline model using softmax, layer normalization, and GELU activation; a softmax-only model without normalization; and variations incorporating weight normalization, spectral normalization, and scaled feed-forward networks (FFN). The figure visualizes how different techniques impact entropy across layers. While weight, spectral, and scaled FFN normalization methods effectively prevent entropy collapse in later layers, they struggle to address entropic overload, the presence of excessive high-entropy values, in earlier layers. The final configuration adds entropy regularization to the scaled FFN approach, demonstrating its effectiveness in managing both entropy collapse and overload.

read the caption

Figure 4: Layerwise entropy patterns in GPT-2 models (L𝐿Litalic_L = 12, H𝐻Hitalic_H = 12, d𝑑ditalic_d = 768) trained from scratch on CodeParrot dataset. Shown are (a) baseline model, (b) Softmax-only model without normalization, and variants with (c) weight normalization, (d) spectral normalization, and (e) scaled-FFN. While these normalization methods prevent entropy collapse, they fail to address entropic overload in early layers. Our final configuration (f) incorporates entropy regularization within scaled-FFN to effectively manage both issues.

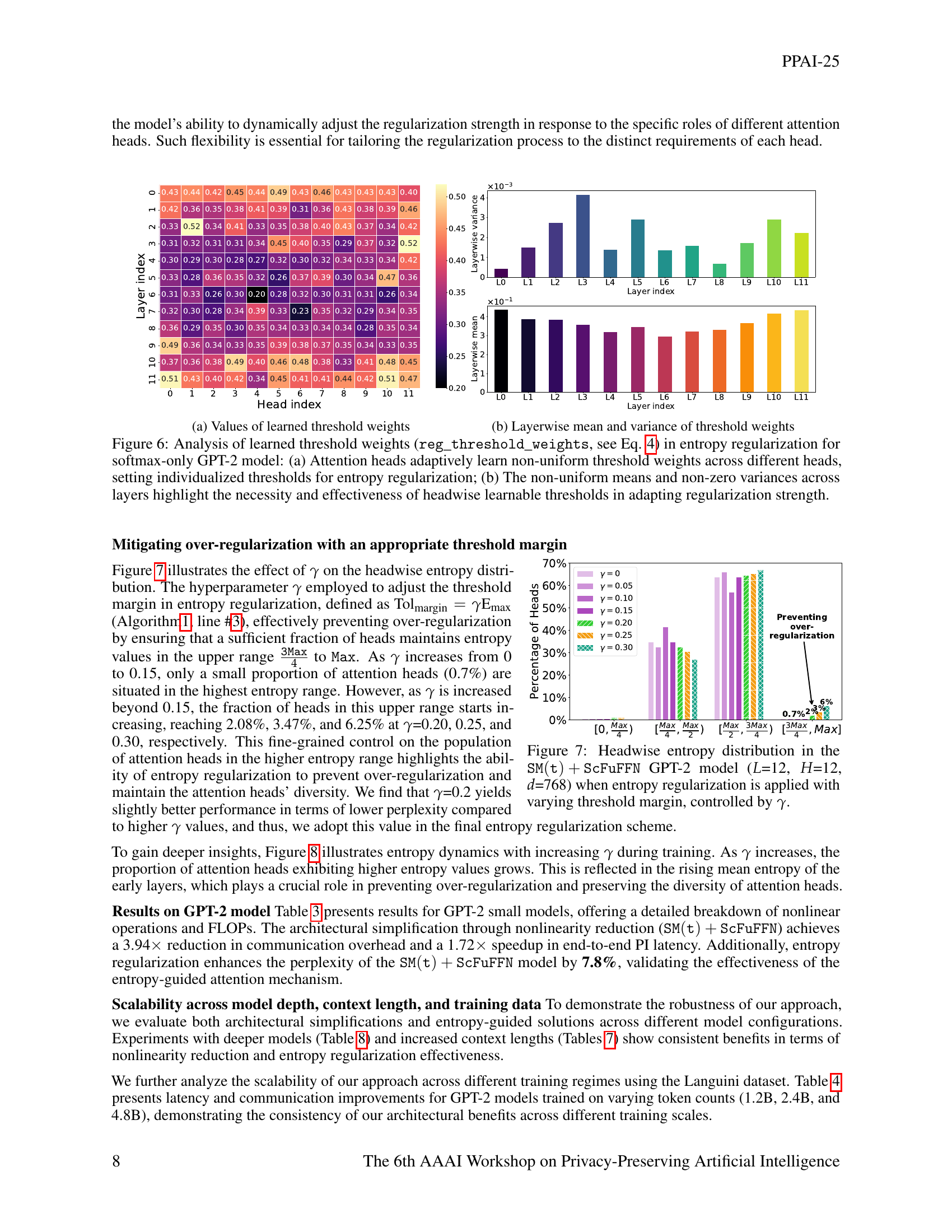

🔼 This figure visualizes the learned threshold weights (reg_threshold_weights) used in the entropy regularization component of the model. The values shown represent the learned fraction of the maximum entropy value (Emax) that is used as a threshold for applying the entropy penalty to individual attention heads. The heatmap shows these weights for each attention head (x-axis) across different layers (y-axis) of the transformer model. Variations in the weights across layers and heads reflect the model’s adaptive adjustment of the regularization strength based on the unique behavior of each head in different layers.

read the caption

(a) Values of learned threshold weights

🔼 This figure visualizes the distribution of learned threshold weights used in the entropy regularization technique across different layers of the model. The top panel shows the mean threshold weight values for each attention head within each layer, revealing how the model dynamically adjusts the regularization strength based on the head’s specific role. The bottom panel displays the layer-wise mean and variance of these weights, emphasizing the non-uniformity of the regularization process across different layers and the significant variability within individual layers. This non-uniformity is a key aspect of the method; the model adapts its regularization approach depending on the specific needs of different layers.

read the caption

(b) Layerwise mean and variance of threshold weights

🔼 Figure 5 displays the learnable threshold weights, represented by \texttt{reg_threshold_weights}, used in the entropy regularization method for a softmax-only GPT-2 model. Panel (a) shows that each attention head learns its own unique threshold weight, allowing for a flexible and adaptive regularization process across different heads. This is important because some heads naturally exhibit higher entropy than others. Panel (b) demonstrates the non-uniformity in average threshold weights across layers and the presence of non-zero variances. This non-uniformity underscores the importance of allowing each head to have its own dynamic threshold, rather than applying a single global threshold across all heads and layers, thereby ensuring effective regularization strength.

read the caption

Figure 5: Analysis of learned threshold weights (𝚛𝚎𝚐_𝚝𝚑𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚑𝚘𝚕𝚍_𝚠𝚎𝚒𝚐𝚑𝚝𝚜𝚛𝚎𝚐_𝚝𝚑𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚑𝚘𝚕𝚍_𝚠𝚎𝚒𝚐𝚑𝚝𝚜\mathtt{reg\_threshold\_weights}typewriter_reg _ typewriter_threshold _ typewriter_weights, see Eq. • ‣ 4) in entropy regularization for softmax-only GPT-2 model: (a) Attention heads adaptively learn non-uniform threshold weights across different heads, setting individualized thresholds for entropy regularization; (b) The non-uniform means and non-zero variances across layers highlight the necessity and effectiveness of headwise learnable thresholds in adapting regularization strength.

🔼 Figure 6 visualizes the impact of the tolerance margin (γ) hyperparameter on the distribution of entropy across attention heads in a GPT-2 language model (12 layers, 12 heads, hidden dimension 768) using the SM(t)+ScFuFFN architecture. The x-axis represents the entropy range, categorized into bins, and the y-axis indicates the percentage of attention heads falling within each entropy range. Different colored bars correspond to various values of γ, illustrating how adjusting the tolerance margin affects the concentration of entropy values. A small tolerance margin leads to more attention heads having high entropy, indicating a less focused attention mechanism. A larger margin results in fewer attention heads exhibiting very high entropy, suggesting a more focused mechanism. This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the tolerance margin in controlling over-regularization and maintaining attention head diversity.

read the caption

Figure 6: Headwise entropy distribution in the 𝚂𝙼(𝚝)+𝚂𝚌𝙵𝚞𝙵𝙵𝙽𝚂𝙼𝚝𝚂𝚌𝙵𝚞𝙵𝙵𝙽{\tt SM(t)+ScFuFFN}typewriter_SM ( typewriter_t ) + typewriter_ScFuFFN GPT-2 model (L𝐿Litalic_L=12, H𝐻Hitalic_H=12, d𝑑ditalic_d=768) when entropy regularization is applied with varying threshold margin, controlled by γ𝛾\gammaitalic_γ.

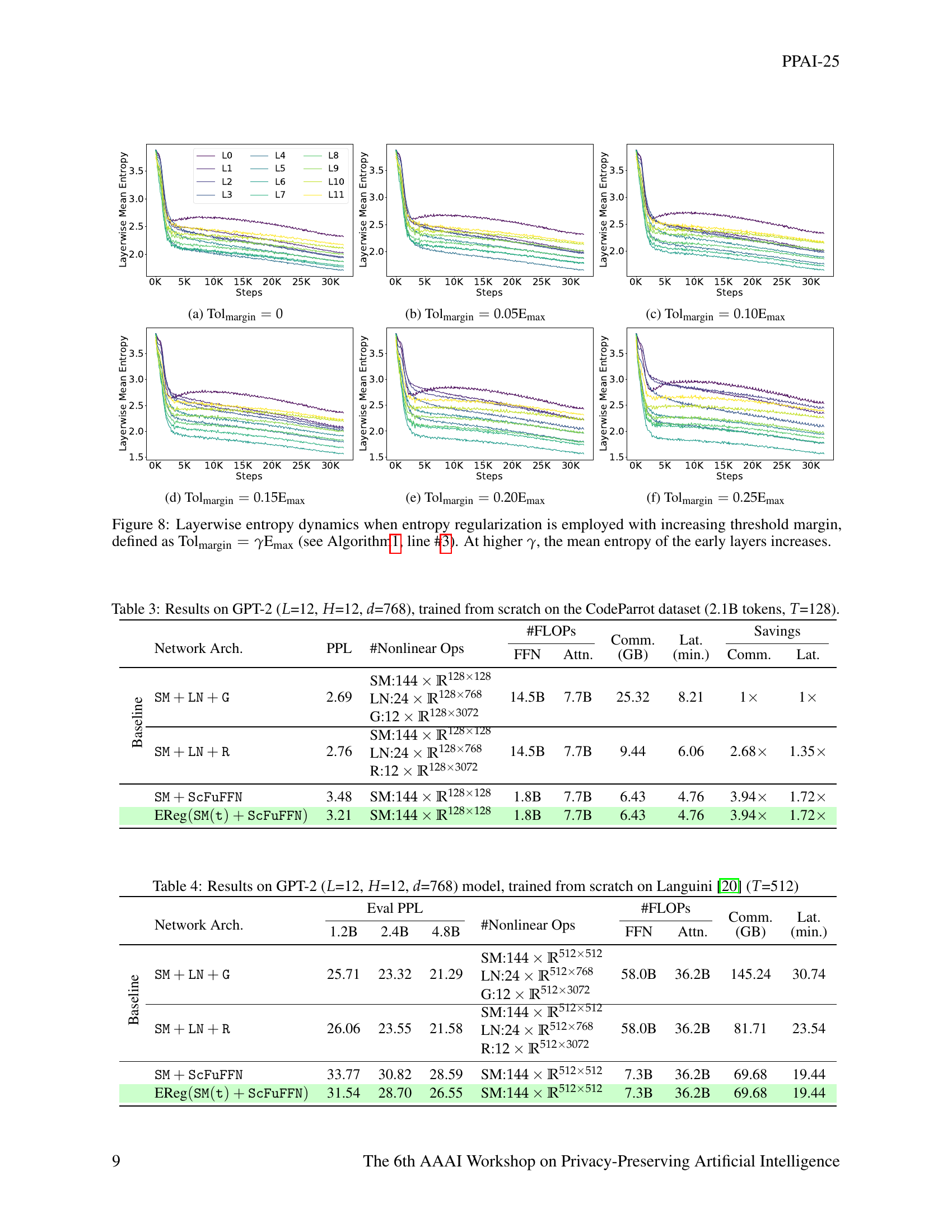

🔼 Figure 8 visualizes the impact of the tolerance margin hyperparameter (Tolmargin) on layer-wise entropy dynamics during the training process of a Softmax-only model. The figure displays six subplots, each representing a different Tolmargin value (0, 0.05Emax, 0.10Emax, 0.15Emax, 0.20Emax, and 0.25Emax). Each subplot shows the average entropy across all attention heads for each layer (L0 through L11) as training progresses (x-axis represents the training steps). It illustrates how increasing the tolerance margin allows for a greater proportion of attention heads to exhibit higher entropy values, particularly in the earlier layers, thereby mitigating over-regularization and preserving attention head diversity. The y-axis represents layer-wise mean entropy while the x-axis represents training steps.

read the caption

(a) Tolmargin=0subscriptTolmargin0\text{Tol}_{\text{margin}}=0Tol start_POSTSUBSCRIPT margin end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 0

🔼 This figure shows the layer-wise mean entropy during the training process of a Softmax-only GPT-2 model with entropy regularization. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the mean entropy across different layers. Different lines correspond to different layers (L0-L11) in the model. The tolerance margin (Tolmargin) is set to 0.05 times the maximum entropy (Emax), influencing the entropy distribution across the layers during training. This plot visualizes how entropy regularization, with a specific tolerance margin, affects the entropy level in each layer throughout the training process. A lower mean entropy value generally indicates a well-behaved attention mechanism, while high values could point to potential issues like entropic overload or underutilization of attention heads.

read the caption

(b) Tolmargin=0.05EmaxsubscriptTolmargin0.05subscriptEmax\text{Tol}_{\text{margin}}=0.05\text{E}_{\text{max}}Tol start_POSTSUBSCRIPT margin end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 0.05 E start_POSTSUBSCRIPT max end_POSTSUBSCRIPT

🔼 Figure 8(c) displays the layer-wise mean entropy dynamics during training of the SM(t)+ScFuFFN model when employing entropy regularization with a tolerance margin set to 0.10 times the maximum entropy value (Tolmargin = 0.10*Emax). The figure visualizes how the average entropy across different layers changes over training steps, demonstrating the impact of this specific tolerance margin setting on the attention mechanism’s entropy distribution. It shows how the entropy values in different layers evolve throughout training, offering insights into the effect of the chosen tolerance margin on the overall entropy dynamics of the model.

read the caption

(c) Tolmargin=0.10EmaxsubscriptTolmargin0.10subscriptEmax\text{Tol}_{\text{margin}}=0.10\text{E}_{\text{max}}Tol start_POSTSUBSCRIPT margin end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 0.10 E start_POSTSUBSCRIPT max end_POSTSUBSCRIPT

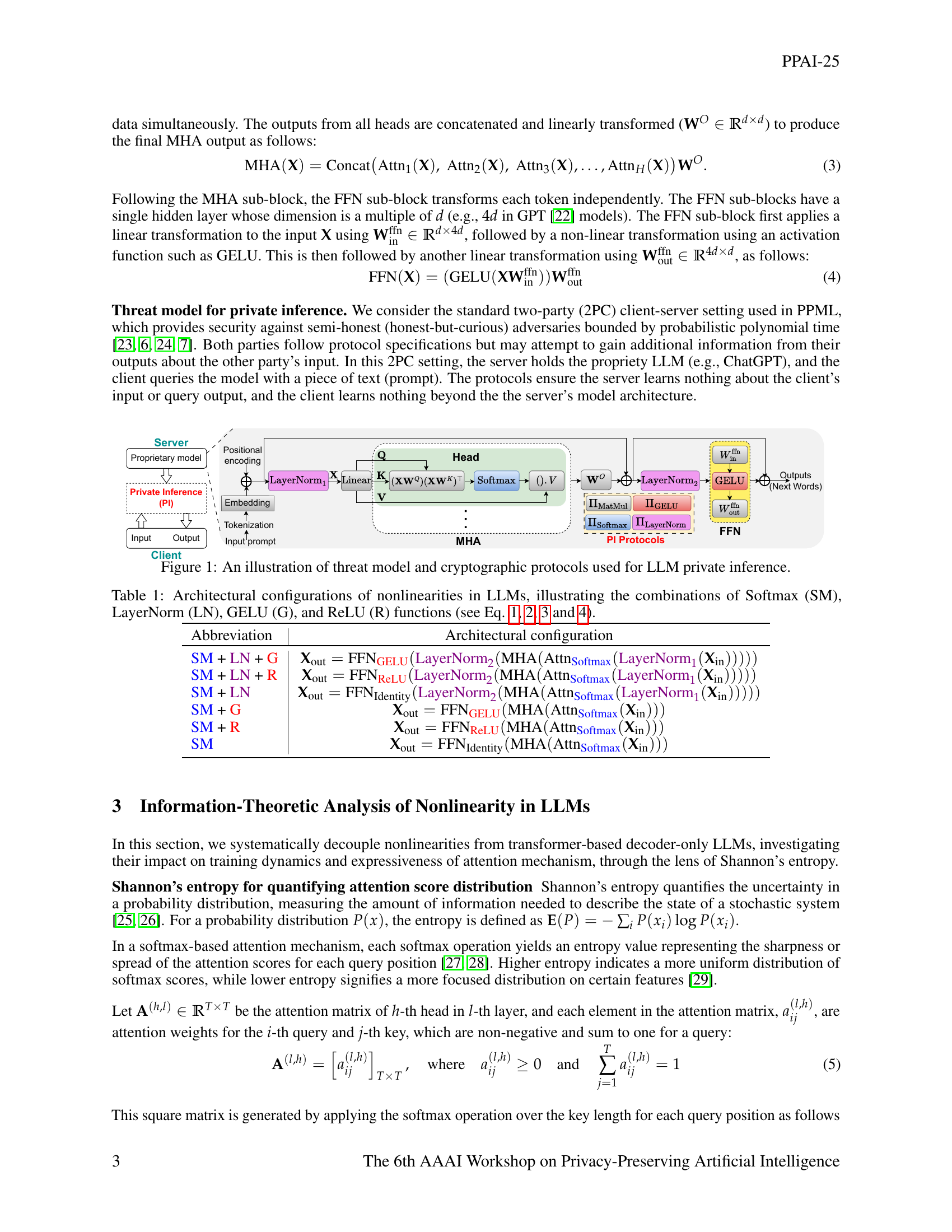

More on tables

| Configurations | PPL | +Δ(%) |

|---|---|---|

| SM + LN + G | 2.69 | 0.00 |

| SM + LN + R | 2.76 | 2.53 |

| SM + LN | 3.38 | 25.58 |

| SM + G | 3.20 | 18.92 |

| SM + R | 2.94 | 9.20 |

| SM | NaNs | - |

🔼 This table visualizes the distribution of entropy values across different attention heads within a language model. Entropy, a measure of uncertainty, reflects the focus or spread of attention weights assigned to input tokens. A high entropy value indicates a more uniform distribution of attention across tokens (less focus), while a low entropy value indicates more concentrated attention on a few specific tokens. The table likely shows how many heads fall within specific entropy ranges (e.g., low, medium, high), offering insights into the attention mechanism’s behavior and potential for improved efficiency and reduced noise.

read the caption

(a) Headwise entropy distribution

| Network Arch. | PPL | #Nonlinear Ops | FFN (FLOPs) | Attn. (FLOPs) | Comm. (GB) | Lat. (min.) | Comm. Savings | Lat. Savings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | SM+LN+G | 2.69 | 14.5B | 7.7B | 25.32 | 8.21 | 1× | 1× | |

| LN: 24×ℝ¹²⁸ˣ⁷⁶⁸ | |||||||||

| G: 12×ℝ¹²⁸ˣ³⁰⁷² | |||||||||

| SM+LN+R | 2.76 | 14.5B | 7.7B | 9.44 | 6.06 | 2.68× | 1.35× | ||

| LN: 24×ℝ¹²⁸ˣ⁷⁶⁸ | |||||||||

| R: 12×ℝ¹²⁸ˣ³⁰⁷² | |||||||||

| SM+ScFuFFN | 3.48 | 1.8B | 7.7B | 6.43 | 4.76 | 3.94× | 1.72× | ||

| EReg(SM(t)+ScFuFFN) | 3.21 | 1.8B | 7.7B | 6.43 | 4.76 | 3.94× | 1.72× |

🔼 The figure shows the training loss curve for various GPT-2 model configurations with different nonlinearities. It illustrates how the training loss changes over epochs, providing insights into the effectiveness of different model architectures in terms of convergence and stability. The different lines represent different model setups such as those with GELU, ReLU, or no nonlinearities in their feed-forward networks, or different layer normalization strategies.

read the caption

(b) Loss curve

| Network Arch. | Eval PPL (1.2B) | Eval PPL (2.4B) | Eval PPL (4.8B) | #Nonlinear Ops | #FLOPs (FFN) | #FLOPs (Attn.) | Comm. (GB) | Lat. (min.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline SM+LN+G | 25.71 | 23.32 | 21.29 | SM: 144×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ⁵¹² LN: 24×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ⁷⁶⁸ G: 12×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ³⁰⁷² | 58.0B | 36.2B | 145.24 | 30.74 |

| SM+LN+R | 26.06 | 23.55 | 21.58 | SM: 144×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ⁵¹² LN: 24×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ⁷⁶⁸ R: 12×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ³⁰⁷² | 58.0B | 36.2B | 81.71 | 23.54 |

| SM+ScFuFFN | 33.77 | 30.82 | 28.59 | SM: 144×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ⁵¹² | 7.3B | 36.2B | 69.68 | 19.44 |

| EReg(SM(t)+ScFuFFN) | 31.54 | 28.70 | 26.55 | SM: 144×ℝ⁵¹²ˣ⁵¹² | 7.3B | 36.2B | 69.68 | 19.44 |

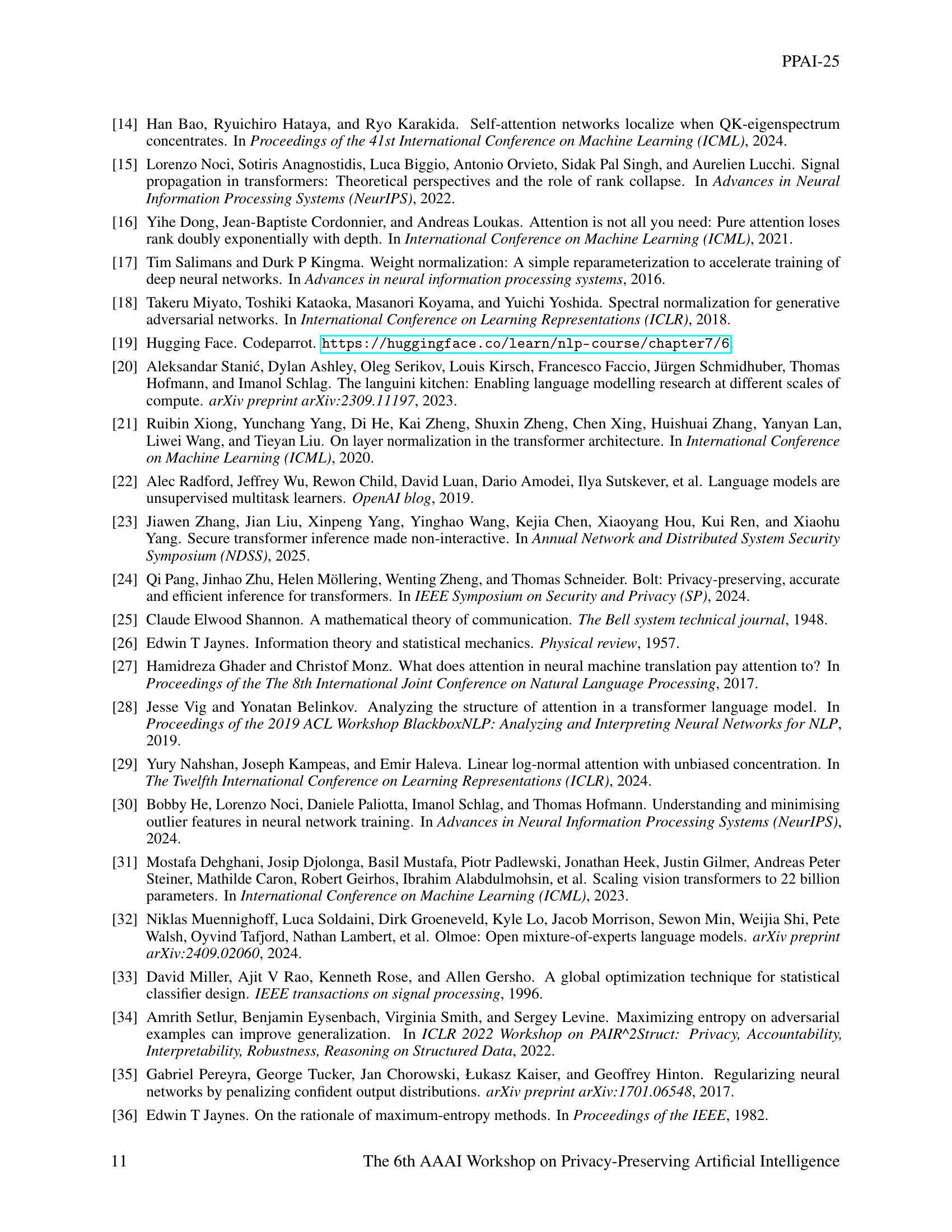

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on a GPT-2 language model with 12 layers, 12 attention heads, and an embedding dimension of 768. The model was trained from scratch using the CodeParrot dataset, which contains 2.1 billion tokens, with a sequence length (context window) of 128 tokens. The table compares the performance of several model variations, each differing in the types of non-linear operations used (e.g., GELU, ReLU, or none), along with the inclusion of entropy regularization. Metrics reported include perplexity (PPL), the number of nonlinear operations, and the total number of floating point operations (FLOPs), along with communication costs and latency. This allows for an evaluation of the impact of different architectural choices on model efficiency and accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Results on GPT-2 (L𝐿Litalic_L=12, H𝐻Hitalic_H=12, d𝑑ditalic_d=768), trained from scratch on the CodeParrot dataset (2.1B tokens, T𝑇Titalic_T=128).

| Linear layers | Eval PPL(Weight Normalization) | Eval PPL(Spectral Normalization) |

|---|---|---|

| QK | 3.89 | 4.25 |

| FFN | 3.64 | 3.63 |

| QK+FFN | 3.88 | 4.23 |

| QKV+FFN | 3.93 | 4.26 |

| QKVO+FFN | 3.98 | 4.34 |

🔼 Table 3 presents the results of experiments conducted on a GPT-2 language model with 12 layers (L=12), 12 attention heads (H=12), and an embedding dimension of 768 (d=768). The model was trained from scratch using the Languini dataset [20] with a context length of 512 tokens (T=512). The table likely shows the performance of different model architectures in terms of perplexity (PPL), the number of nonlinear operations, FLOPs (floating-point operations), and communication and latency overheads for private inference. It might also compare different configurations like the inclusion or exclusion of LayerNorm, GELU, and other components, demonstrating the impact of various architectural choices on the efficiency of private inference.

read the caption

Table 3: Results on GPT-2 (L𝐿Litalic_L=12, H𝐻Hitalic_H=12, d𝑑ditalic_d=768) model, trained from scratch on Languini [20] (T𝑇Titalic_T=512)

| Weight Normalization | Spectral Normalization | Scaled-FFN |

|---|---|---|

| Eval PPL | 3.640 | 3.624 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of weight normalization and spectral normalization techniques when applied to different linear layers within a Softmax-only GPT-2 language model. The model has 12 layers (L=12), 12 attention heads (H=12), and an embedding dimension of 768 (d=768). It was trained from scratch using the CodeParrot dataset with an input context length of 128 tokens. The table compares the evaluation perplexity (Eval PPL) achieved using each normalization method in different layer combinations: QK (query-key), FFN (feed-forward network), QK+FFN, QKV+FFN (query-key-value + FFN), and QKVO+FFN (query-key-value-output + FFN). The results show that FFN weight normalization yields similar performance across all layer combinations. In contrast, weight normalization generally performs better than spectral normalization in other linear layers.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison of weight normalization [17] and spectral normalization [18] when employed in Softmax-only GPT-2 (L𝐿Litalic_L=12, H𝐻Hitalic_H=12, d𝑑ditalic_d=768) models, and trained from scratch on CodeParrot dataset with 128 input context length. FFN weight normalization yield the similar results; whereas, weight normalization works better in other linear layers.

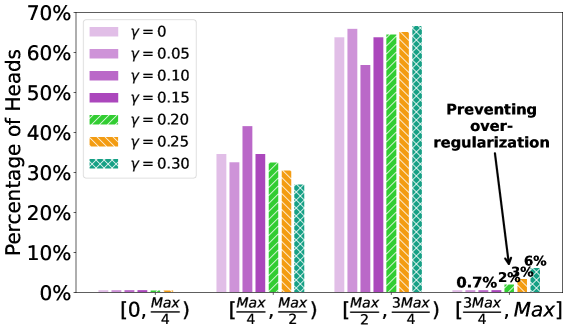

| Network Arch. | PPL | #Nonlinear Ops | FFN FLOPs | Attn. FLOPs | Comm. (GB) | Lat. (min.) | Comm. Savings | Lat. Savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline SM+LN+G | 2.35 | 144xℝ256x256 24xℝ256x768 12xℝ256x3072 | 29.0B | 16.3B | 58.51 | 16.57 | 1x | 1x |

| SM+LN+R | 2.41 | 144xℝ256x256 24xℝ256x768 12xℝ256x3072 | 29.0B | 16.3B | 26.73 | 12.59 | 2.19x | 1.32x |

| SM+ScFuFFN | 3.03 | 144xℝ256x256 | 3.6B | 16.3B | 20.72 | 10.45 | 2.82x | 1.59x |

| EReg(SM(t)+ScFuFFN) | 2.92 | 144xℝ256x256 | 3.6B | 16.3B | 20.72 | 10.45 | 2.82x | 1.59x |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the perplexity scores achieved by three different methods for regularizing the feed-forward network (FFN) in a softmax-only version of the GPT-2 language model. The methods compared are weight normalization, spectral normalization, and learnable scaling. The model was trained from scratch on the CodeParrot dataset using an input context length of 128 tokens. The perplexity scores provide a measure of how well each regularization technique generalizes to unseen data.

read the caption

Table 5: Perplexity comparison of weight normalization, spectral normalization, and learnable scaling employed in FFN of softmax-only GPT-2 model, when trained from scratch on CodeParrot dataset with 128 input context length.

| Network Arch. | PPL | #Nonlinear Ops | #FLOPs (FFN) | #FLOPs (Attn.) | Comm. (GB) | Lat. (min.) | Savings (Comm.) | Savings (Lat.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baseline | SM+LN+G | 2.56 | 21.7B | 11.6B | 37.17 | 10.77 | 1x | 1x | ||

| SM: 216xℝ128x128 LN: 36xℝ128x768 G: 18xℝ128x3072 | ||||||||||

| SM+LN+R | 2.63 | 21.7B | 11.6B | 13.34 | 8.04 | 2.79x | 1.34x | |||

| SM: 216xℝ128x128 LN: 36xℝ128x768 R: 18xℝ128x3072 | ||||||||||

| SM+ScFuFFN | 3.24 | 2.7B | 11.6B | 8.83 | 6.07 | 4.21x | 1.77x | |||

EReg(SM(t)+ScFuFFN) | 3.13 | 2.7B | 11.6B | 8.83 | 6.07 | 4.21x | 1.77x |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted on a GPT-2 language model with 12 layers, 12 attention heads, and an embedding dimension of 768. The model was trained from scratch using the CodeParrot dataset, which comprises 2.1 billion tokens and a context length of 256. The table compares the performance of several model configurations, focusing on their perplexity (PPL), the number of nonlinear operations, floating point operations (FLOPS), the communication overhead (Comm.), and latency (Lat.). The configurations evaluated include the baseline model (SM + LN + G), a model with ReLU activation (SM + LN + R), a simplified Softmax-only model (SM + ScFuFFN), and finally, the proposed entropy-regularized Softmax-only model (EReg(SM(t) + ScFuFFN)). The comparison highlights the performance gains and resource savings achieved by the simplified and entropy-regularized architectures in terms of perplexity, computational cost, communication, and latency.

read the caption

Table 6: Results on GPT-2 (L𝐿Litalic_L=12, H𝐻Hitalic_H=12, d𝑑ditalic_d=768), trained from scratch on the CodeParrot dataset (2.1B tokens, T𝑇Titalic_T=256).

Full paper#