↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current video generation methods struggle with precise control, often limited to a single control type. This paper introduces Diffusion as Shader (DaS), which tackles this problem. The core issue is the lack of 3D awareness in existing methods, relying solely on 2D control signals while videos are fundamentally 2D renderings of 3D content. This makes achieving versatile and precise video control challenging.

DaS uses 3D tracking videos as control signals, offering a novel 3D-aware approach. This allows for a wider range of control tasks, including mesh animation, motion transfer, camera control, and object manipulation. The method shows improved data efficiency, achieving strong control results with just 3 days of fine-tuning on a relatively small dataset. The superior performance and versatility of DaS are demonstrated through various experiments, comparing favorably against existing methods in terms of both quantitative metrics and qualitative visual results.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to video generation control, enabling versatile and precise manipulation. It addresses a major challenge in the field by leveraging 3D tracking videos as control signals, allowing for multiple control types within a unified architecture. This opens new avenues for researchers in video generation and related fields, impacting applications such as film-making, animation, and virtual reality.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the core concept and capabilities of the Diffusion as Shader (DaS) model. Panel (a) provides a high-level overview of the DaS architecture, highlighting its 3D-awareness. This 3D awareness is key to the model’s ability to perform various video manipulation tasks. The subsequent panels (b-e) showcase examples of these capabilities: (b) demonstrates the ability to animate 3D meshes and generate realistic videos from them, (c) shows motion transfer, allowing the model to apply the motion from one video to another, (d) illustrates camera control where the viewpoint is modified to create different perspectives on the same scene, and finally, (e) exhibits object manipulation, permitting changes to the location and appearance of objects within a video. These examples collectively highlight the versatile control DaS offers over video generation.

read the caption

Figure 1. Diffusion as Shader (DaS) is (a) a 3D-aware video diffusion method enabling versatile video control tasks including (b) animating meshes to video generation, (c) motion transfer, (d) camera control, and (e) object manipulation.

| Method | Small Movement | Large Movement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TransErr ↓ | RotErr ↓ | TransErr ↓ | RotErr ↓ | |

| MotionCtrl | 44.23 | 8.92 | 67.05 | 39.86 |

| CameraCtrl | 42.31 | 7.82 | 66.76 | 29.70 |

| Ours | 27.85 | 5.97 | 37.17 | 10.40 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of three different methods for camera control in video generation: MotionCtrl (Wang et al., 2024c), CameraCtrl (He et al., 2024b), and the authors’ proposed method. The comparison is based on two metrics: TransErr and RotErr. TransErr measures the angular difference between the estimated translation vector of the camera and the ground truth translation vector, while RotErr measures the angular difference between the estimated rotation (quaternion) and the ground truth rotation. Smaller values for both metrics indicate better performance. The results are reported for both small and large camera movements.

read the caption

Table 1. Quantitative results on camera control of MotionCtrl (Wang et al., 2024c), CameraCtrl (He et al., 2024b), and our method. “TransErr” and “RotErr” are the angle differences between the estimated translation and rotation and the ground-truth ones in degree.

In-depth insights#

3D-Aware Diffusion#

The concept of “3D-Aware Diffusion” in video generation signifies a paradigm shift from traditional 2D diffusion models. Instead of treating video frames as independent 2D images, a 3D-aware approach leverages inherent spatial and temporal relationships within the video sequence. This is achieved by representing the video as a dynamic 3D scene, often using 3D tracking data or depth maps to guide the diffusion process. This allows for more precise and versatile control over video generation, enabling tasks such as realistic camera movements, object manipulation, and seamless motion transfer between videos. The key advantage lies in the improved temporal coherence and enhanced realism that arise from understanding the underlying 3D structure, avoiding the artifacts and inconsistencies that often plague purely 2D methods. This framework shows significant potential for creating high-fidelity videos with fine-grained control, opening up exciting possibilities for applications in animation, VFX, and other creative fields.

Shader-Based Control#

Shader-based control, in the context of video generation, presents a powerful paradigm shift. Instead of manipulating the video directly, it proposes using shaders to process intermediate 3D representations before rendering. This approach offers enhanced control and flexibility, particularly with 3D-aware models. By manipulating 3D tracking videos, one can achieve diverse control tasks such as animating meshes, transferring motion, or manipulating objects. The shader acts as an intermediary, allowing modifications in the 3D space that directly translate into refined visual changes in the generated video. This is a significant advantage over prior methods that solely used 2D control signals, which often struggle with fine-grained or temporally coherent control. The 3D awareness is crucial, ensuring the generated videos maintain realistic movement and object interactions. However, the efficacy of this approach is tightly coupled with the accuracy and completeness of the 3D tracking data. Inaccurate or sparse tracking information may lead to artifacts or inconsistencies in the final generated video. Future work should focus on improving the robustness of this method to handle noisy or incomplete 3D tracking data.

Versatile Video Synthesis#

Versatile video synthesis is a rapidly evolving field aiming to generate high-quality, diverse videos with precise control. Current methods often struggle with balancing controllability and quality, frequently limited to single control types. 3D-aware approaches, like the one presented in the paper, offer a promising solution by leveraging 3D information to achieve a wide range of manipulations. This enables fine-grained control over various aspects such as camera movement, object manipulation, and motion transfer. The key challenge remains in developing robust, data-efficient methods that can handle diverse control demands and maintain temporal consistency without significant computational overhead. The use of 3D tracking videos as control signals demonstrates a significant step towards achieving versatile and high-quality video synthesis. Future work should focus on improving data efficiency and addressing limitations in handling complex scenes and ambiguous control inputs. The development of more powerful and flexible models capable of learning complex spatio-temporal relationships is crucial for achieving true versatility in video generation.

DaS Limitations#

The DaS model, while demonstrating impressive capabilities in versatile video generation control, is not without limitations. A major constraint is its reliance on accurate 3D tracking videos. Inaccuracies or inconsistencies in the tracking data directly impact the quality and coherence of the generated videos. Failure cases arise when the input image and 3D tracking video are incompatible, leading to scene transitions or unnatural results. Furthermore, regions lacking 3D tracking data points result in uncontrolled content generation, highlighting a need for more robust tracking methods. The model also exhibits a dependence on computationally expensive 3D tracking algorithms, posing a potential barrier to real-time applications or broader accessibility. While impressive results are shown, further development is crucial to enhance the robustness of the 3D tracking process and address these shortcomings, thereby unlocking DaS’s full potential for more reliable and widely applicable video generation control.

Future Directions#

Future research should focus on improving the robustness of 3D tracking, addressing limitations in handling complex scenes or occlusions. Exploring alternative 3D representation methods, beyond point clouds, such as meshes or volumetric representations, could enhance control and realism. Investigating more efficient training strategies, potentially leveraging self-supervised learning or transfer learning, would reduce the computational cost. Further research could explore incorporating other modalities, like audio or haptic feedback, for richer control. Finally, developing a unified framework that seamlessly integrates multiple control signals, enabling fine-grained manipulation across various aspects of video generation, is a crucial next step.

More visual insights#

More on figures

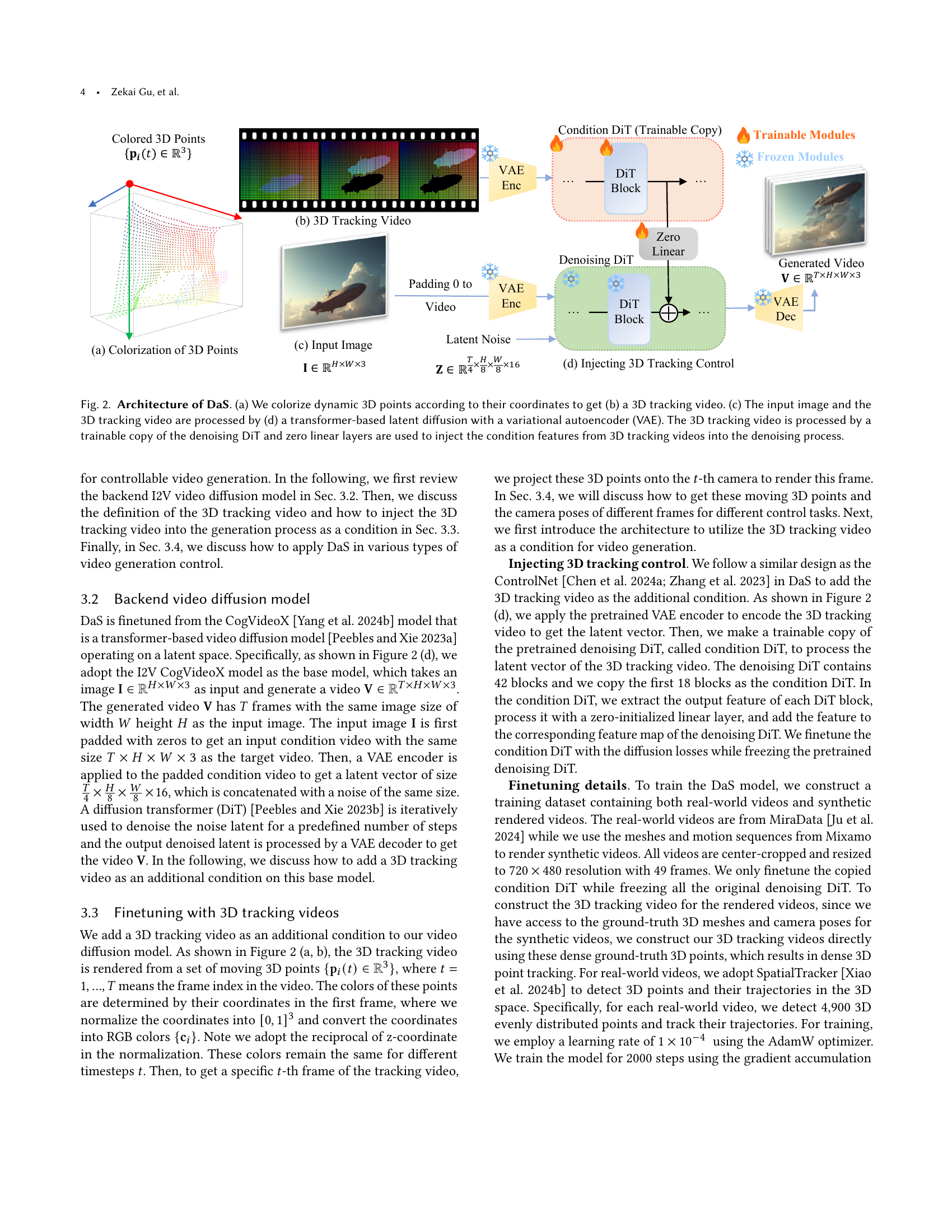

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Diffusion as Shader (DaS) model. It begins by explaining how 3D points are color-coded based on their coordinates (a), forming a 3D tracking video (b) which acts as a control signal. The input image (c) and the 3D tracking video are then fed into a transformer-based latent diffusion model using a Variational Autoencoder (VAE). A crucial step is the use of a ’trainable copy’ of the denoising Diffusion Transformer (DiT) to process the 3D tracking video. Zero linear layers help integrate the condition features from this video into the denoising process, making the model 3D-aware.

read the caption

Figure 2. Architecture of DaS. (a) We colorize dynamic 3D points according to their coordinates to get (b) a 3D tracking video. (c) The input image and the 3D tracking video are processed by (d) a transformer-based latent diffusion with a variational autoencoder (VAE). The 3D tracking video is processed by a trainable copy of the denoising DiT and zero linear layers are used to inject the condition features from 3D tracking videos into the denoising process.

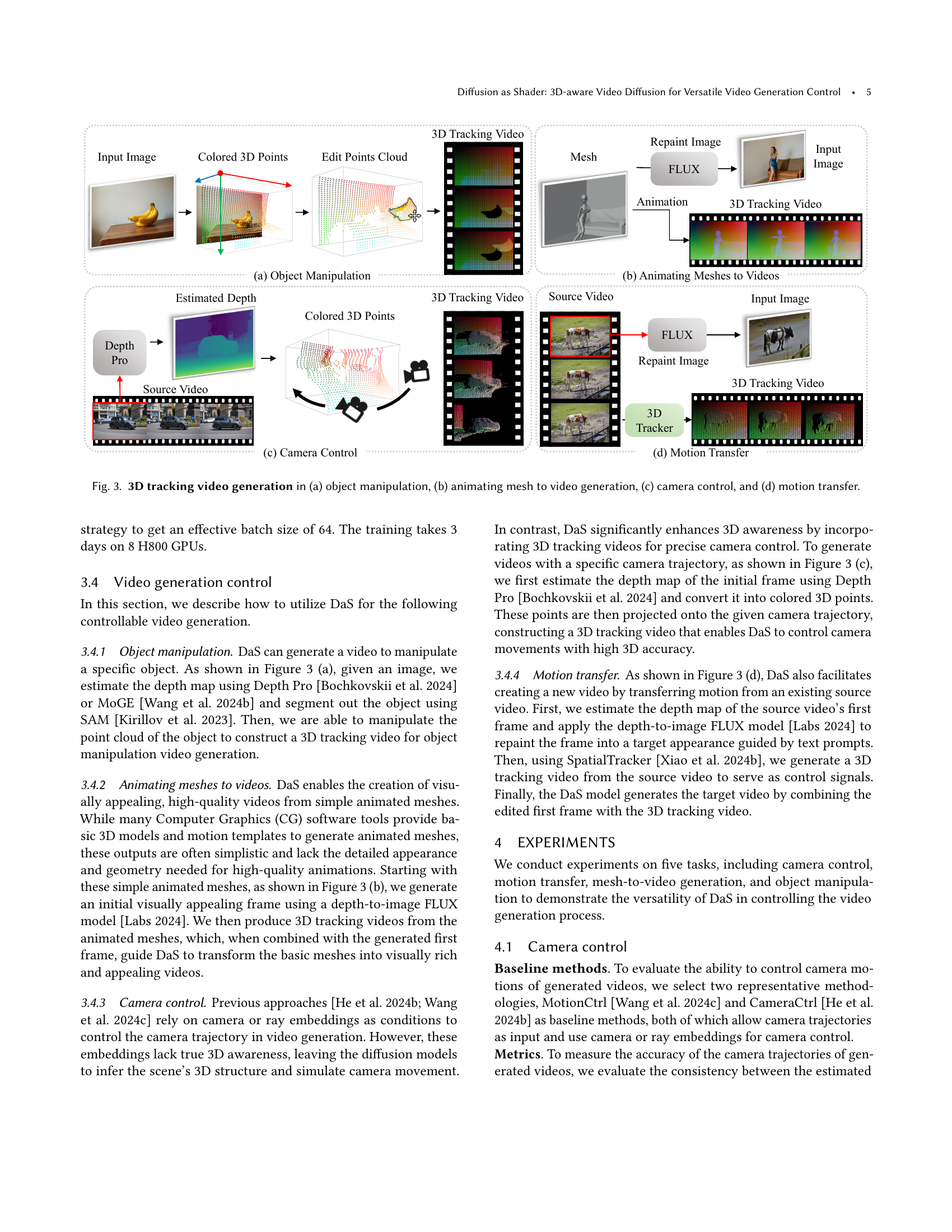

🔼 This figure illustrates how 3D tracking videos are generated for four different video control tasks using the Diffusion as Shader (DaS) method. (a) Object manipulation: Depth maps and object segmentation are used to identify and manipulate the 3D points of an object, creating a 3D tracking video that guides the object’s movement in the generated video. (b) Animating meshes to videos: Animated 3D meshes are converted into 3D tracking videos, providing control over mesh animation. (c) Camera control: Depth maps and camera trajectories are used to generate a 3D tracking video that directs camera movements in the output video. (d) Motion transfer: A 3D tracker processes a source video to generate a 3D tracking video which captures and transfers the motion to a new video with potentially altered styling or content.

read the caption

Figure 3. 3D tracking video generation in (a) object manipulation, (b) animating mesh to video generation, (c) camera control, and (d) motion transfer.

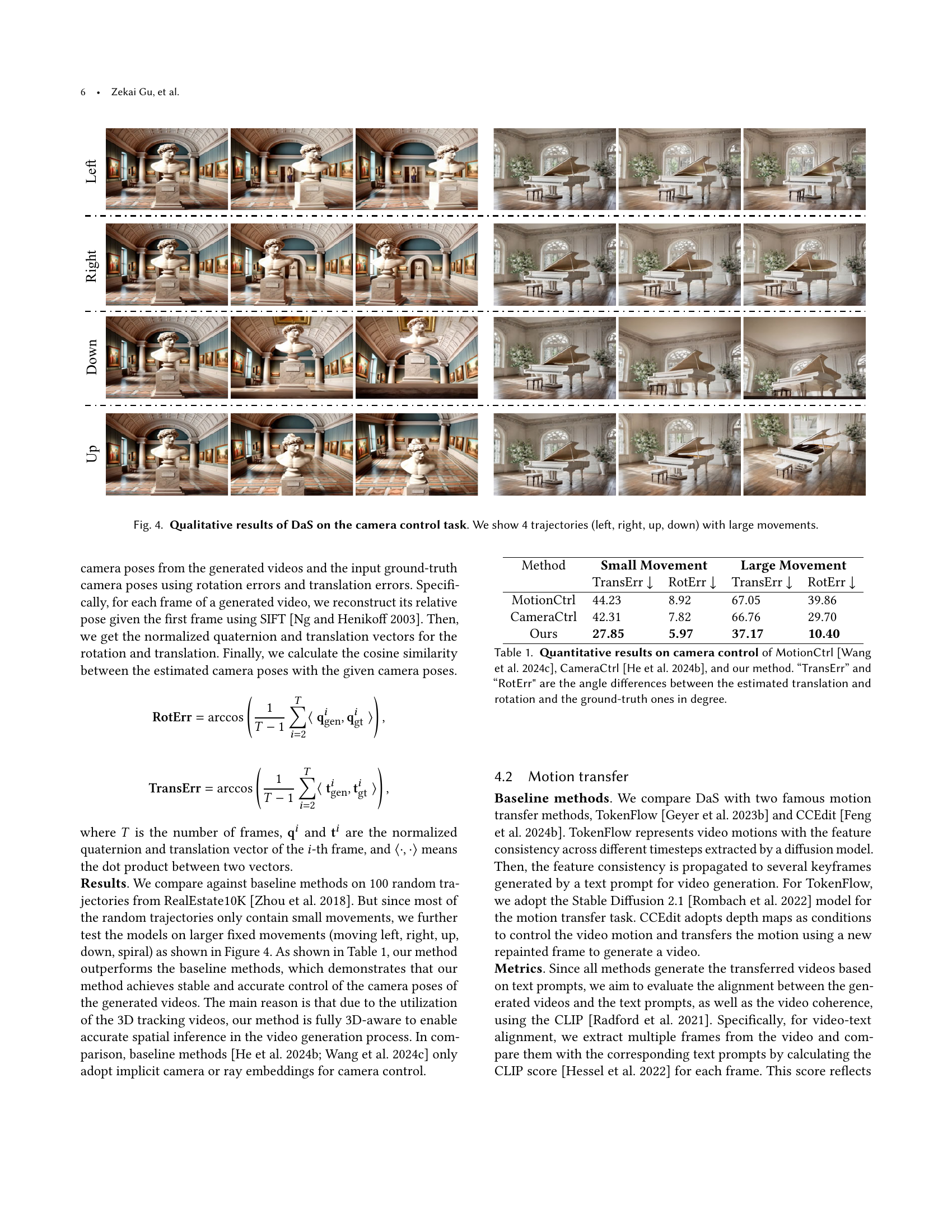

🔼 This figure showcases the qualitative results of the Diffusion as Shader (DaS) model on camera control tasks. Four distinct camera trajectories are depicted (left, right, up, and down movements) across multiple frames. The large-scale movements demonstrate the model’s ability to generate videos with diverse and complex camera paths accurately. Each row shows a sequence of frames from a video generated with DaS, demonstrating the smoothness and realism of the camera motions.

read the caption

Figure 4. Qualitative results of DaS on the camera control task. We show 4 trajectories (left, right, up, down) with large movements.

🔼 Figure 5 presents a qualitative comparison of motion transfer results obtained using three different methods: the authors’ proposed method, CCEdit (Feng et al., 2024b), and TokenFlow (Geyer et al., 2023b). For each method, two example video generation results are displayed, each accompanied by the corresponding text prompt. This allows for a visual assessment of each method’s ability to accurately translate the motion described in the text prompt into the generated video, considering factors like fidelity, coherence, and overall quality of the video generated. The comparison highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach in achieving accurate motion transfer.

read the caption

Figure 5. Qualitative comparison on motion transfer between our method, CCEdit (Feng et al., 2024b), and TokenFlow (Geyer et al., 2023b).

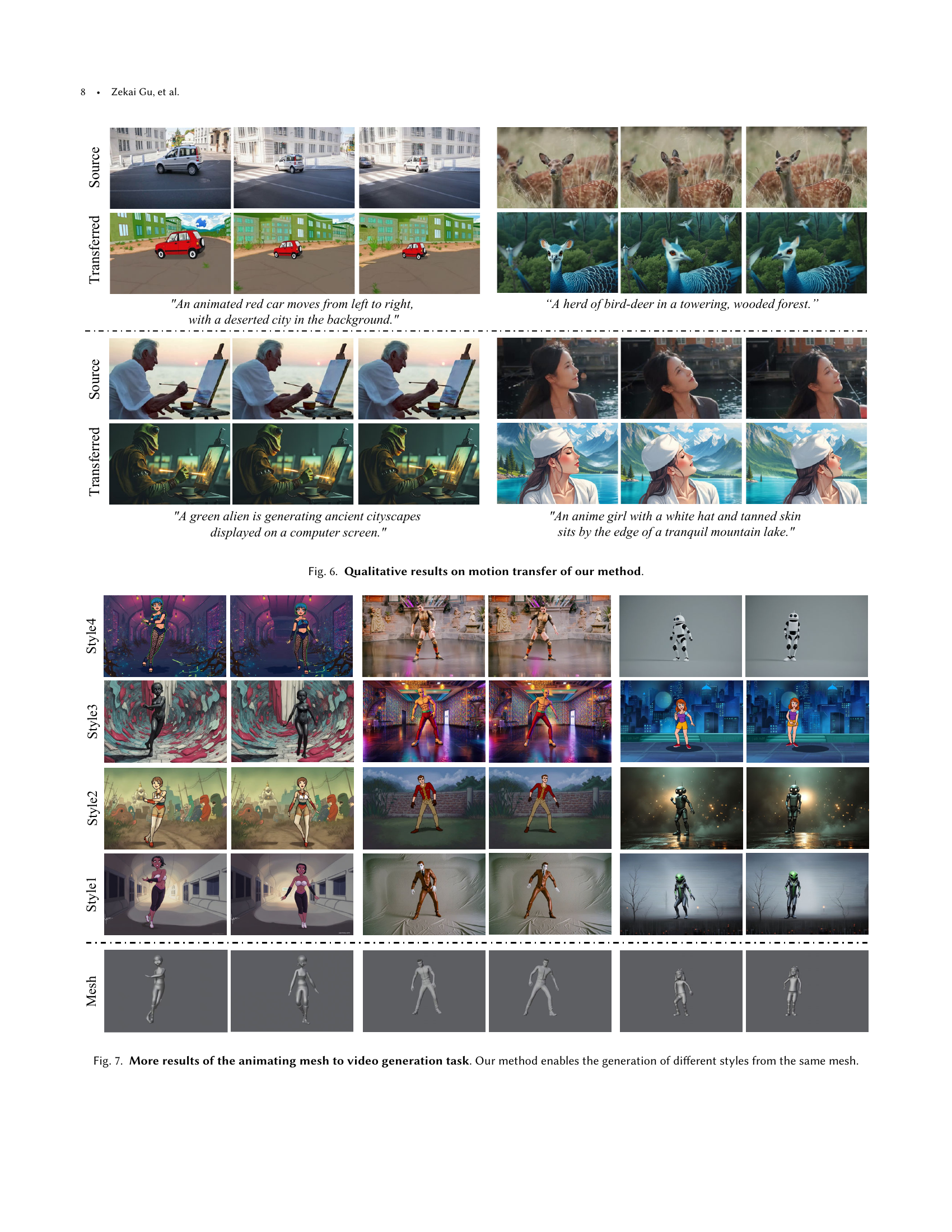

🔼 Figure 6 showcases the qualitative results of the motion transfer task using the proposed Diffusion as Shader (DaS) method. It displays several pairs of source and transferred videos generated by the DaS model. The source video is shown on the top row of each pair, while the DaS-generated transferred video is presented in the bottom row. Each pair demonstrates the ability of DaS to transfer motion while maintaining good quality and visual coherence.

read the caption

Figure 6. Qualitative results on motion transfer of our method.

🔼 Figure 7 showcases the versatility of the proposed Diffusion as Shader (DaS) method in generating videos from animated 3D meshes. It demonstrates that, using the same underlying mesh as input, DaS can produce videos with vastly different artistic styles. This highlights the method’s ability to decouple animation from visual style, allowing for greater control and creative freedom in video generation.

read the caption

Figure 7. More results of the animating mesh to video generation task. Our method enables the generation of different styles from the same mesh.

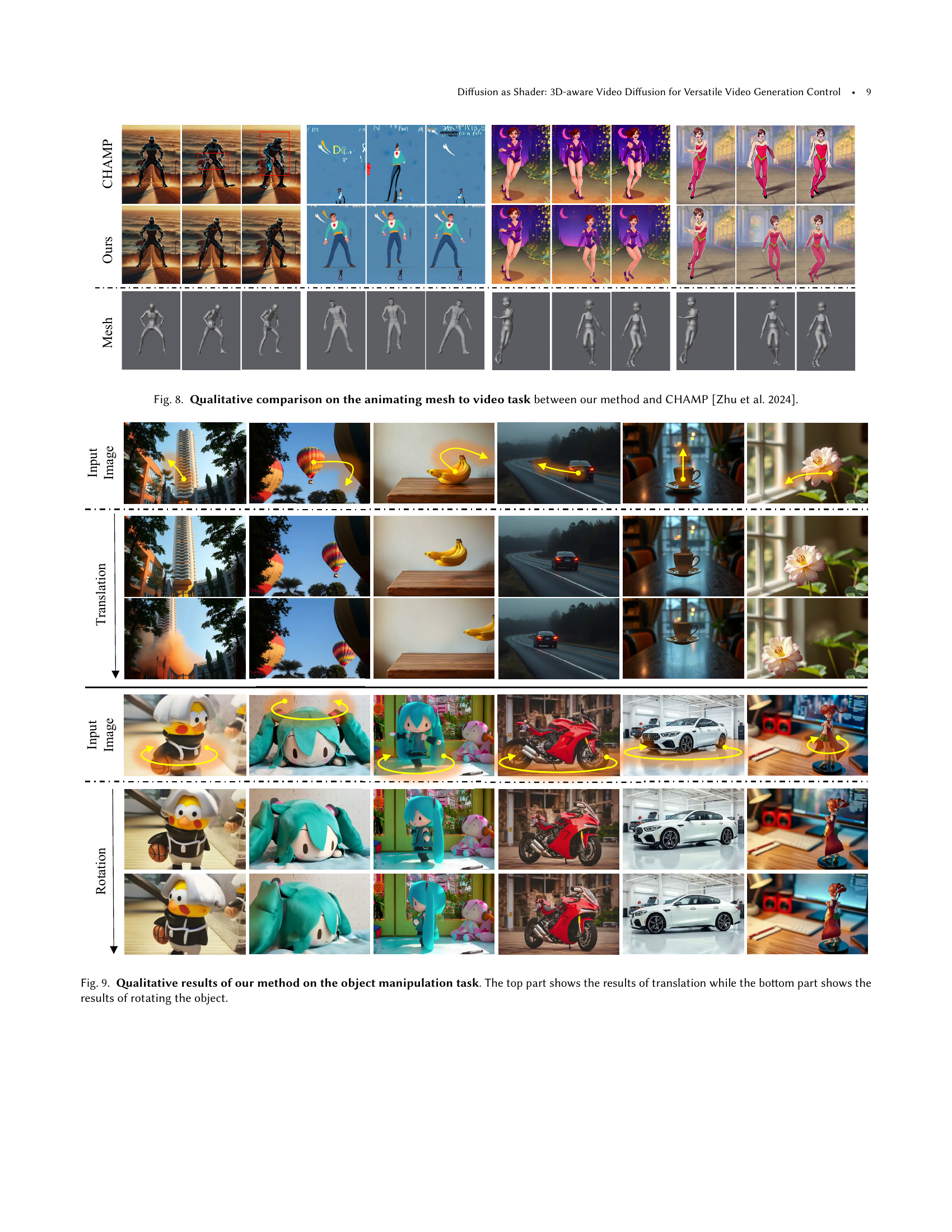

🔼 Figure 8 presents a qualitative comparison of video generation results from two different methods: the proposed ‘Diffusion as Shader’ (DaS) approach and the CHAMP method (Zhu et al., 2024). Both methods tackle the task of animating 3D meshes into realistic videos. The figure visually demonstrates the capabilities of each approach by showing generated video frames corresponding to various animation sequences and stylistic choices (different styles), allowing for a direct comparison of their respective visual quality, animation smoothness, and overall realism. The comparison highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each method in terms of producing high-fidelity, visually appealing videos from input 3D mesh animations.

read the caption

Figure 8. Qualitative comparison on the animating mesh to video task between our method and CHAMP (Zhu et al., 2024).

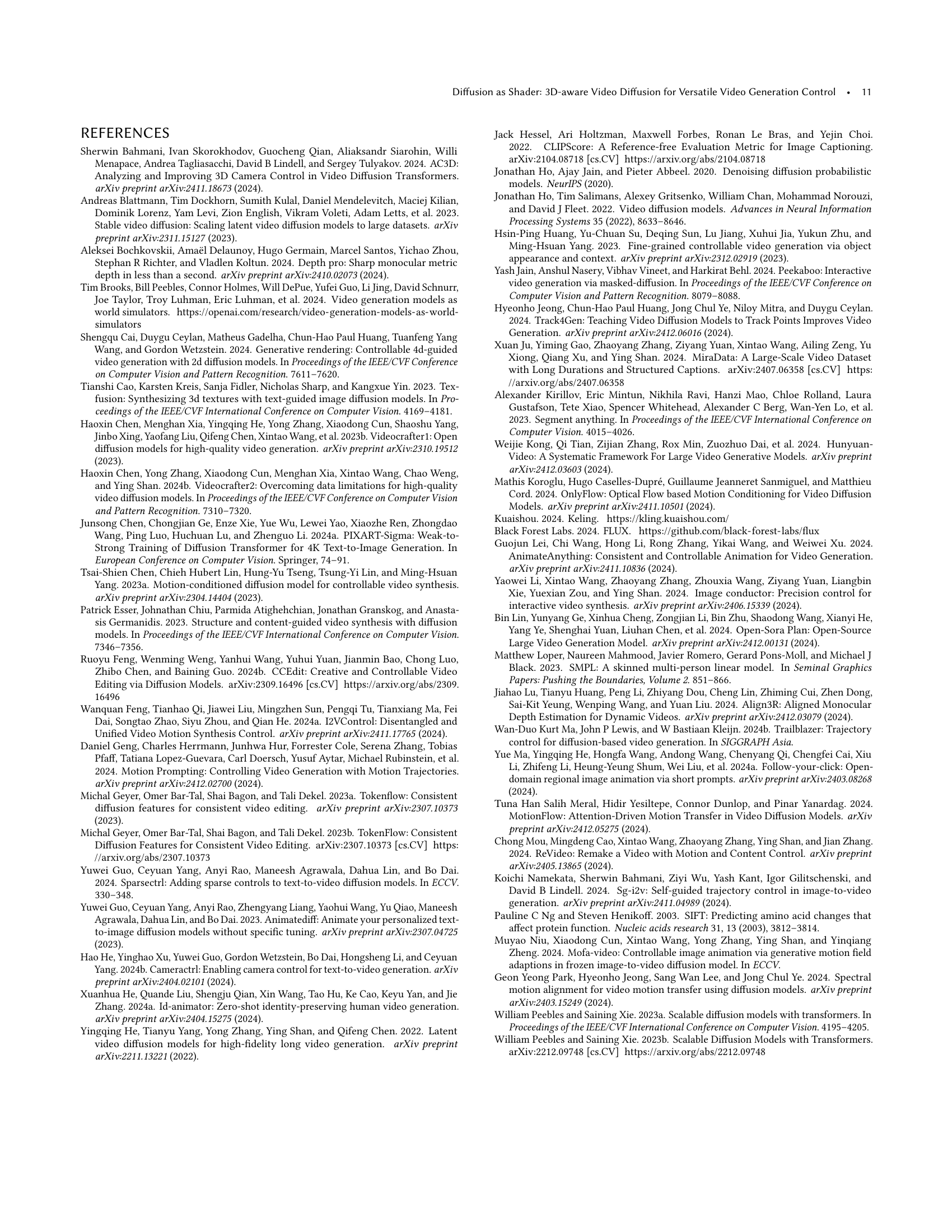

🔼 Figure 9 presents qualitative results demonstrating the object manipulation capabilities of the Diffusion as Shader (DaS) model. The top half showcases examples of object translation, where the object’s position changes within the scene. The bottom half displays object rotation, showing how DaS can modify the object’s orientation. Each example includes the input image and the result generated by DaS, illustrating the model’s ability to seamlessly integrate object manipulation into video generation.

read the caption

Figure 9. Qualitative results of our method on the object manipulation task. The top part shows the results of translation while the bottom part shows the results of rotating the object.

🔼 This figure compares the results of video generation using two different types of 3D control signals: depth maps and 3D tracking videos. The goal was to assess the impact of each method on the temporal consistency of generated videos, meaning how well the generated frames flow together smoothly over time. The image showcases several generated video sequences side-by-side, allowing for a visual comparison of the quality of each approach. The results demonstrate that videos created using 3D tracking videos exhibit substantially better cross-frame consistency than those produced with depth maps.

read the caption

Figure 10. Generated videos using depth maps or 3D tracking videos as control signals. Our 3D tracking videos provide better quality on the cross-frame consistency for video generation than depth maps.

🔼 Figure 11 demonstrates two failure scenarios of the DaS model. The top panel shows a case where an incompatible tracking video (i.e., a video whose 3D points don’t correspond to the input image’s content) is used. As a result, the model generates a video that shifts to a visually similar but different scene. The bottom panel illustrates another failure: when the 3D tracking video lacks data for certain regions of the input image (out-of-tracking range). In this case, the model generates video content for those regions that’s not constrained by the 3D tracking information, resulting in uncontrolled or unrealistic visual elements.

read the caption

Figure 11. Failure cases. (Top) Incompatible tracking video. When a tracking video that does not correspond to the structures of the input image is provided, DaS will generate a video with a scene transition to a compatible new scene. (Bottom) Out of tracking range. For regions without 3D tracking points, the tracking video fails to constrain these regions and DaS may generate some uncontrolled content.

More on tables

| Method | Tex-Ali ↑ | Tem-Con ↑ |

|---|---|---|

| CCEdit | 16.9 | 0.932 |

| Tokenflow | 31.9 | 0.956 |

| Ours | 32.6 | 0.971 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of three different methods for motion transfer in video generation: CCEdit, TokenFlow, and the authors’ proposed method. The comparison is based on two CLIP scores: Text-Ali and Tem-Con. Text-Ali measures the semantic consistency between the generated videos and the corresponding text prompts used to guide the generation process; a higher score indicates better alignment between the generated video content and the intended meaning of the text prompt. Tem-Con measures the temporal consistency of the generated videos, evaluating how well the video’s frames flow smoothly over time; a higher score indicates better temporal coherence. The table allows for a direct comparison of the effectiveness of the three methods in achieving both semantic and temporal consistency in motion transfer.

read the caption

Table 2. CLIP scores for motion transfer of CCEdit (Feng et al., 2024b), TokenFlow (Geyer et al., 2023b), and our method. “Text-Ali” is the semantic CLIP consistency between generated videos and the given text prompts. “Tem-Con” is the temporal CLIP consistency between neighboring frames.

| Depth | Tracking | #Tracks | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ | LPIPS ↓ | FVD ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | - | 18.08 | 0.573 | 0.312 | 645.1 | |

| ✓ | 900 | 18.52 | 0.586 | 0.337 | 765.3 | |

| ✓ | 2500 | 19.17 | 0.632 | 0.263 | 566.4 | |

| ✓ | 4900 | 19.27 | 0.658 | 0.261 | 551.3 | |

| ✓ | 8100 | 19.11 | 0.649 | 0.262 | 599.0 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of using depth maps versus 3D tracking videos as control signals in an image-to-video generation model. The evaluation metrics include PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, and FVD, which measure various aspects of video quality (peak signal-to-noise ratio, structural similarity, learned perceptual image patch similarity, and Fréchet video distance, respectively). The performance is assessed on the validation sets of the DAVIS and MiraData datasets. The table also investigates the impact of varying the number of 3D points used in the 3D tracking video, providing insights into the trade-off between control precision and computational cost. The results highlight the superior performance of 3D tracking videos over depth maps for generating high-quality videos.

read the caption

Table 3. Analysis of applying different 3D control signals for image to video generation. We evaluate PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, and FVD of generated videos on the validation set of the DAVIS and MiraData datasets. “Depth” means using depth maps as the 3D control signals. “Tracking” means using 3D tracking videos as the control signals. #Tracks means the number of 3D points used in the 3D tracking video.

Full paper#