↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current AI-assisted research methods struggle with accurately assessing AI-generated ideas and incorporating feedback loops, hindering the goal of fully automated scientific research. Existing works either rely on human evaluation or use simplified datasets, lacking a true feedback mechanism between idea generation and experimental validation.

DOLPHIN, a novel closed-loop framework, tackles these issues by automating the entire research cycle: generating research ideas from relevant literature, performing experiments using automatically generated and debugged code, and analyzing results to refine future ideas. Its task-attribute-guided idea generation and exception-traceback-guided debugging significantly improve efficiency and successful code execution rates. Experimental validation shows DOLPHIN can generate high-quality, novel ideas comparable to state-of-the-art methods and successfully execute experiments in a continuous loop, making substantial progress towards fully automated scientific research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and scientific research because it presents DOLPHIN, the first closed-loop open-ended auto-research framework. This significantly advances automated scientific research by addressing key challenges in idea generation, experimental validation, and feedback mechanisms. The framework’s ability to generate high-quality research ideas comparable to state-of-the-art methods and complete experiments automatically opens exciting new avenues for future research. It provides a valuable foundation for developing more sophisticated AI-driven research systems and will undoubtedly shape future research methodologies.

Visual Insights#

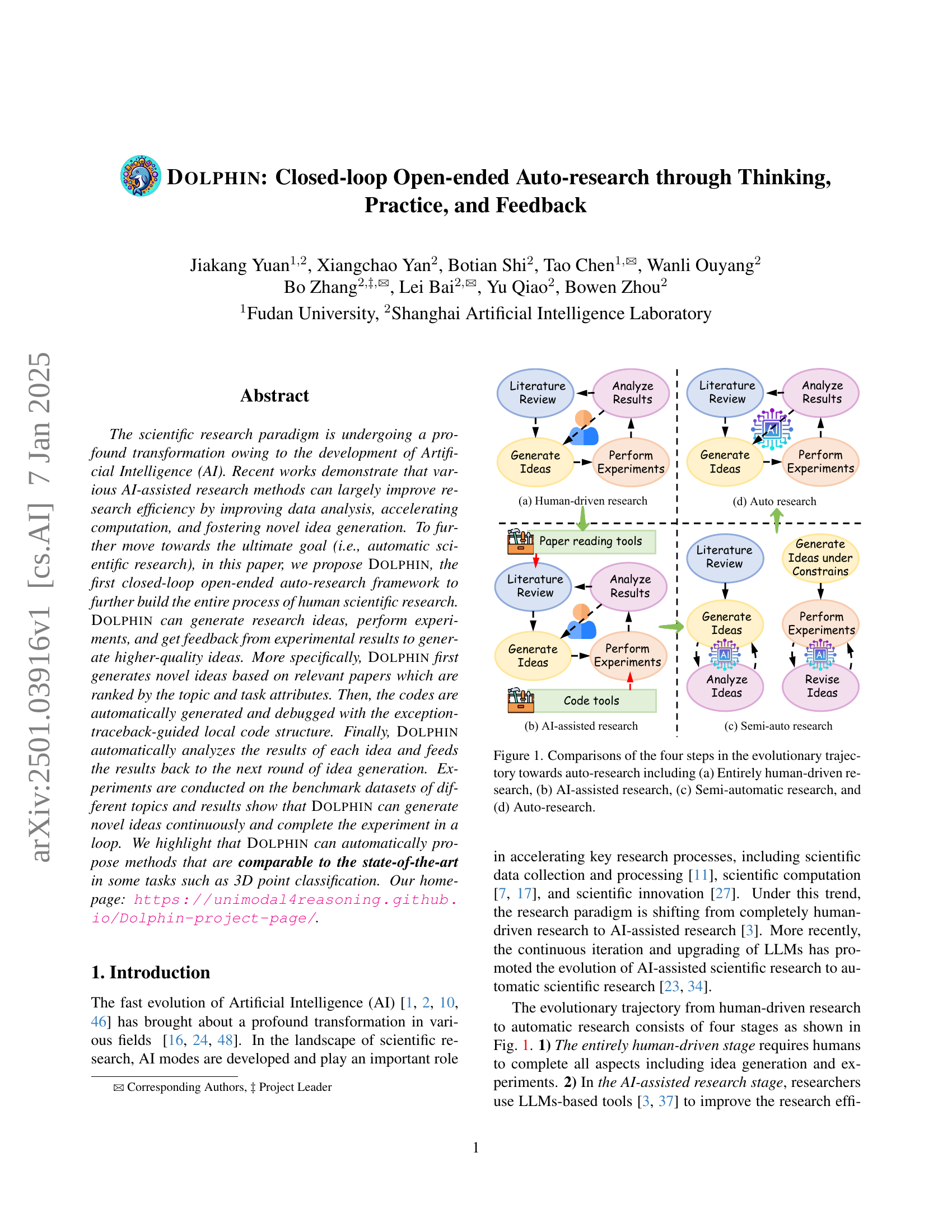

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of scientific research methods, progressing from fully manual processes to complete automation. (a) shows the traditional human-driven approach where all steps, from idea generation to experimentation and analysis, are performed by researchers. (b) depicts AI-assisted research, where AI tools enhance specific steps such as data analysis or computation. (c) represents semi-automatic research, characterized by partial automation of the research workflow. Finally, (d) showcases the ultimate goal of fully automated scientific research, where AI autonomously handles the entire research process, from idea generation and experimentation to result analysis.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparisons of the four steps in the evolutionary trajectory towards auto-research including (a) Entirely human-driven research, (b) AI-assisted research, (c) Semi-automatic research, and (d) Auto-research.

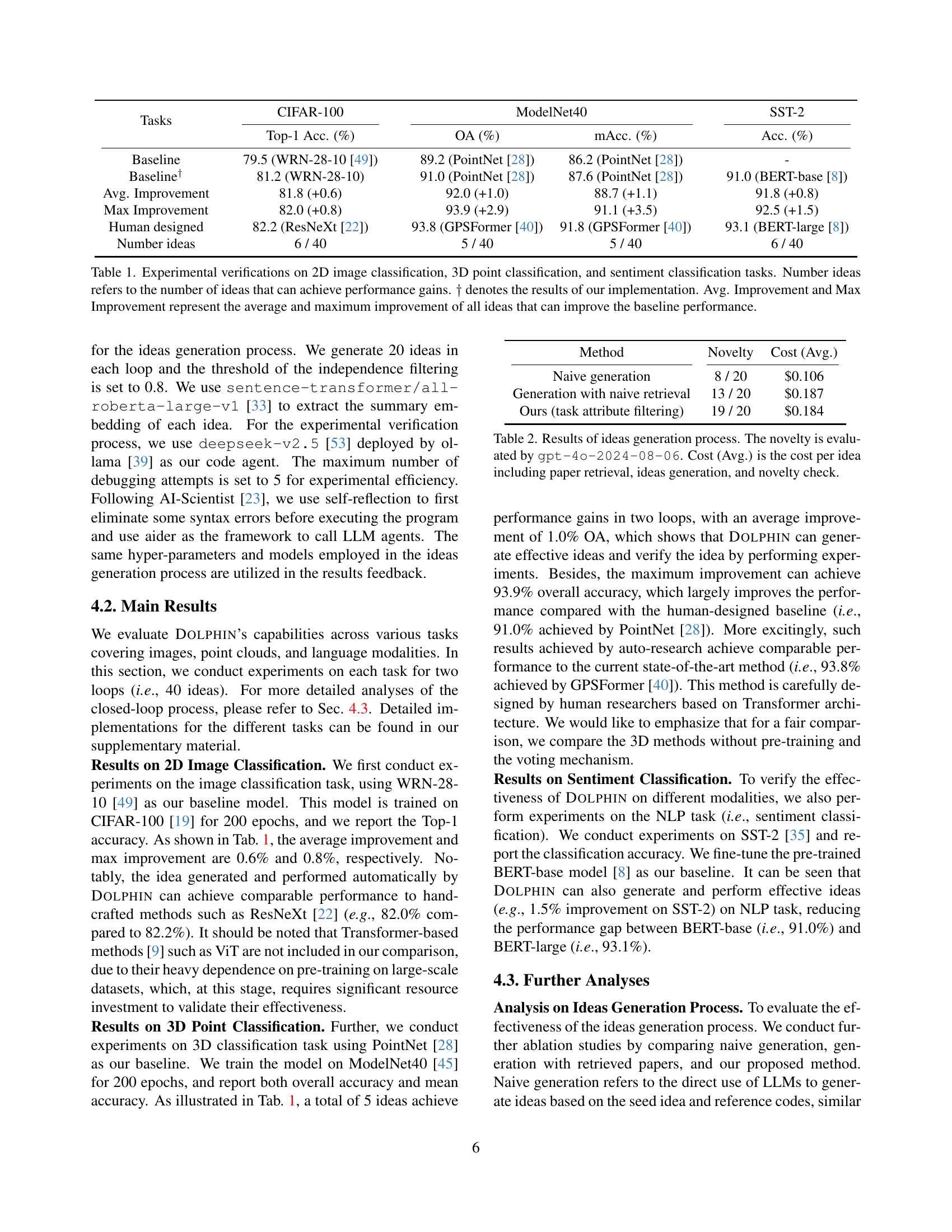

| Tasks | CIFAR-100 | ModelNet40 | SST-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top-1 Acc. (%) | OA (%) | mAcc. (%) | Acc. (%) | |||

| Baseline | 79.5 (WRN-28-10 [49]) | 89.2 (PointNet [28]) | 86.2 (PointNet [28]) | |||

| Baseline† | 81.2 (WRN-28-10) | 91.0 (PointNet [28]) | 87.6 (PointNet [28]) | |||

| Avg. Improvement | 81.8 (+0.6) | 92.0 (+1.0) | 88.7 (+1.1) | |||

| Max Improvement | 82.0 (+0.8) | 93.9 (+2.9) | 91.1 (+3.5) | |||

| Human designed | 82.2 (ResNeXt [22]) | 93.8 (GPSFormer [40]) | 91.8 (GPSFormer [40]) | |||

| Number ideas | 6 / 40 | 5 / 40 | 5 / 40 |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the DOLPHIN framework on three different tasks: 2D image classification, 3D point cloud classification, and sentiment classification. For each task, the table shows the top-1 accuracy or overall accuracy achieved by a baseline model. It then shows the average and maximum improvement in accuracy achieved by DOLPHIN across multiple automatically generated ideas. The ‘Number of ideas’ column indicates how many of the generated ideas resulted in performance gains compared to the baseline. The results marked with † denote those obtained using the DOLPHIN implementation.

read the caption

Table 1: Experimental verifications on 2D image classification, 3D point classification, and sentiment classification tasks. Number ideas refers to the number of ideas that can achieve performance gains. ††\dagger† denotes the results of our implementation. Avg. Improvement and Max Improvement represent the average and maximum improvement of all ideas that can improve the baseline performance.

In-depth insights#

Auto-research Intro#

An ‘Auto-research Intro’ section would ideally set the stage by defining the core concept of automated scientific research. It should clearly distinguish auto-research from AI-assisted research, highlighting the critical difference of complete autonomy versus human-in-the-loop augmentation. The introduction should then establish the need for auto-research, perhaps by discussing limitations of current human-driven processes like time constraints, biases, and scalability issues. A compelling case could be made by demonstrating how automation could overcome these hurdles, accelerating scientific progress and tackling complex problems beyond human capacity. This section should also provide a high-level overview of the proposed auto-research framework, outlining its key components and methodology, without going into excessive detail, which would be left for subsequent sections. Finally, the introduction should state the main contributions of the paper and its significance in advancing the field of automated scientific discovery, potentially emphasizing novel aspects of the framework or its experimental validation.

DOLPHIN’s Design#

DOLPHIN’s design is a closed-loop, open-ended auto-research framework aiming to automate the entire scientific research process. Its core strength lies in its iterative, feedback-driven nature, mimicking the human research cycle. The framework begins with idea generation, leveraging LLMs and a novel task-attribute-guided paper ranking system to ensure relevant and high-quality ideas. Crucially, these ideas are not just evaluated for novelty, but also experimentally verified. The experimental verification phase involves automatic code generation, debugging (using an exception-traceback-guided approach), and execution. Results are automatically analyzed, providing feedback which influences subsequent idea generation, thus closing the loop. This cyclical process allows for continuous refinement and enhancement of research outputs, moving beyond the limitations of current AI-assisted research systems which often lack true closed-loop feedback or comprehensive experimental validation. The design’s innovative combination of LLMs, automated code handling, and feedback mechanisms represents a significant step towards achieving truly autonomous scientific research.

Experiment Results#

The ‘Experiment Results’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the hypotheses and assessing the effectiveness of the proposed methods. A strong results section should go beyond merely presenting numbers; it needs to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings, presented in a way that is easily understandable and interpretable. Visualizations such as graphs and tables are essential for effectively communicating complex data. The discussion should highlight significant trends and patterns, while acknowledging any limitations or unexpected outcomes. Statistical analysis is key to determining the significance of the findings and to support claims of improvement over existing methods. The paper should compare results to baseline methods or previous work to demonstrate progress. A critical analysis of the results should be included, discussing potential sources of error and areas for future research, such as limitations imposed by the experimental design, dataset biases, or other uncontrolled variables. Robust error analysis and consideration of potential confounding factors are crucial aspects. Clearly stated conclusions that directly relate back to the research questions are necessary. Ultimately, the results section should persuade the reader of the validity and importance of the research findings, providing a convincing argument that supports the paper’s overall contributions.

Future of Auto-research#

The future of auto-research hinges on several key advancements. Firstly, more sophisticated AI models are needed, capable of handling the nuances of scientific inquiry beyond current limitations. This includes improved abilities in hypothesis generation, experimental design, and result interpretation, moving beyond simple pattern recognition to genuinely creative problem-solving. Secondly, robust feedback mechanisms are crucial; AI systems must learn from both successful and failed experiments, adapting strategies and refining their approaches over time. This necessitates high-quality datasets meticulously labelled and curated to ensure accurate learning. Thirdly, ethical considerations will play an increasingly vital role. Addressing potential biases in AI-generated research, ensuring transparency in the research process, and mitigating unintended consequences are paramount. Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential, integrating AI expertise with domain-specific scientific knowledge to achieve meaningful breakthroughs. The future of auto-research is not about replacing human researchers, but augmenting their capabilities, leading to a more efficient and potentially revolutionary scientific landscape.

DOLPHIN Limitations#

DOLPHIN, while innovative, faces limitations. Data dependency is a significant constraint; its performance hinges on the quality and relevance of benchmark datasets, which might not always generalize well to other research areas. Computational cost is another factor; running extensive experiments across multiple loops demands considerable computational resources. The reliance on LLMs introduces inherent biases and limitations in idea generation and code debugging; the system’s output quality is directly tied to the LLM’s capabilities. Feedback mechanism efficacy requires further investigation to ensure continuous improvements in subsequent iterations. The interpretability of DOLPHIN’s generated ideas and decisions remains a challenge, which needs further work for building trust and understanding. Finally, generalizability is crucial; while showing promise, its effectiveness needs to be evaluated across diverse scientific domains beyond the initial benchmarks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

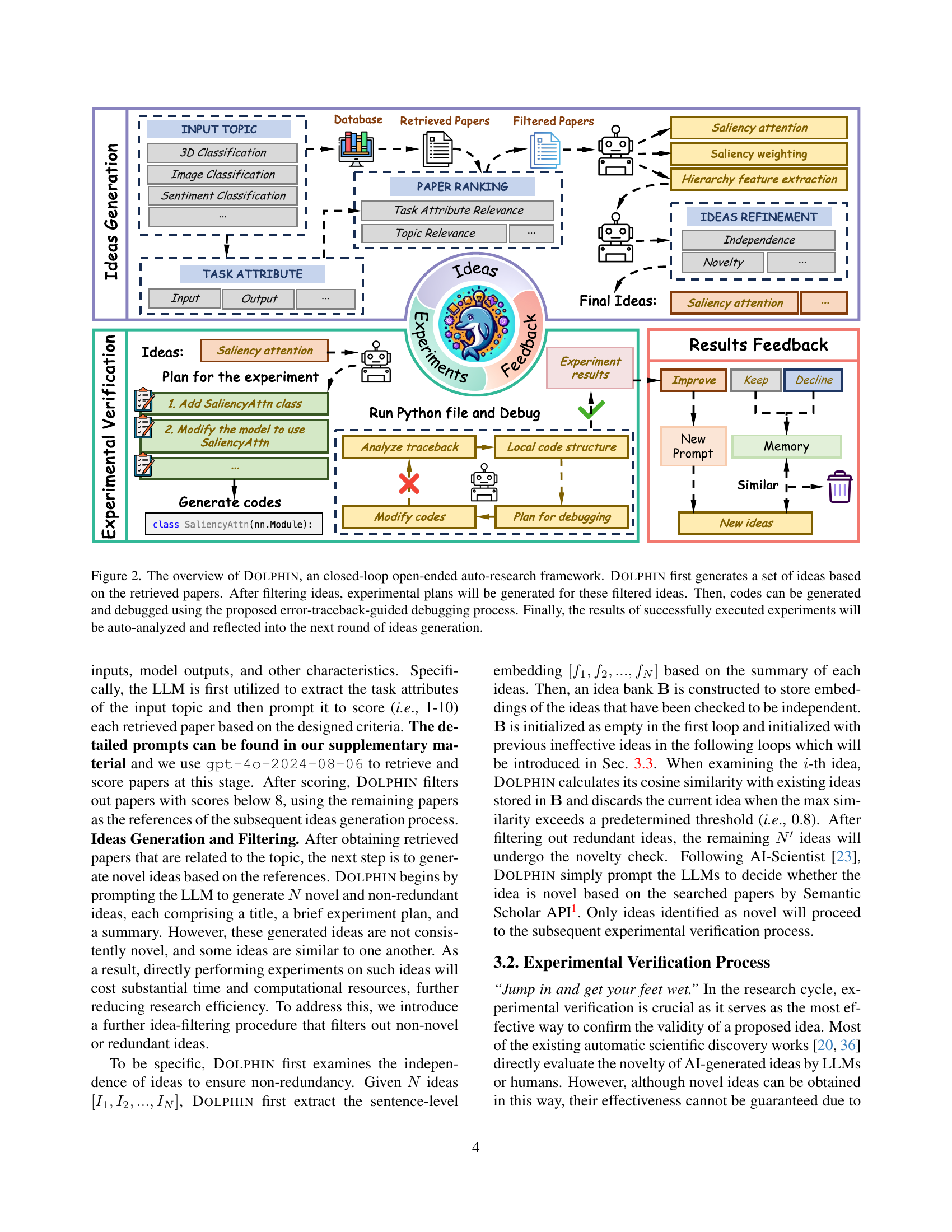

🔼 The figure illustrates the DOLPHIN framework, a closed-loop, open-ended auto-research system. It details the iterative process of scientific research automation. First, DOLPHIN retrieves relevant papers and generates research ideas based on those papers. These ideas then undergo a filtering process to select the most promising ones. For each selected idea, an experimental plan is created and subsequently used to generate the necessary code. The generated code is then automatically debugged using an error-traceback-guided approach. Finally, DOLPHIN automatically analyzes the results of successful experiments, feeding that information back into the system to improve the quality of future idea generation. This iterative cycle repeats to continuously refine the research process.

read the caption

Figure 2: The overview of Dolphin, an closed-loop open-ended auto-research framework. Dolphin first generates a set of ideas based on the retrieved papers. After filtering ideas, experimental plans will be generated for these filtered ideas. Then, codes can be generated and debugged using the proposed error-traceback-guided debugging process. Finally, the results of successfully executed experiments will be auto-analyzed and reflected into the next round of ideas generation.

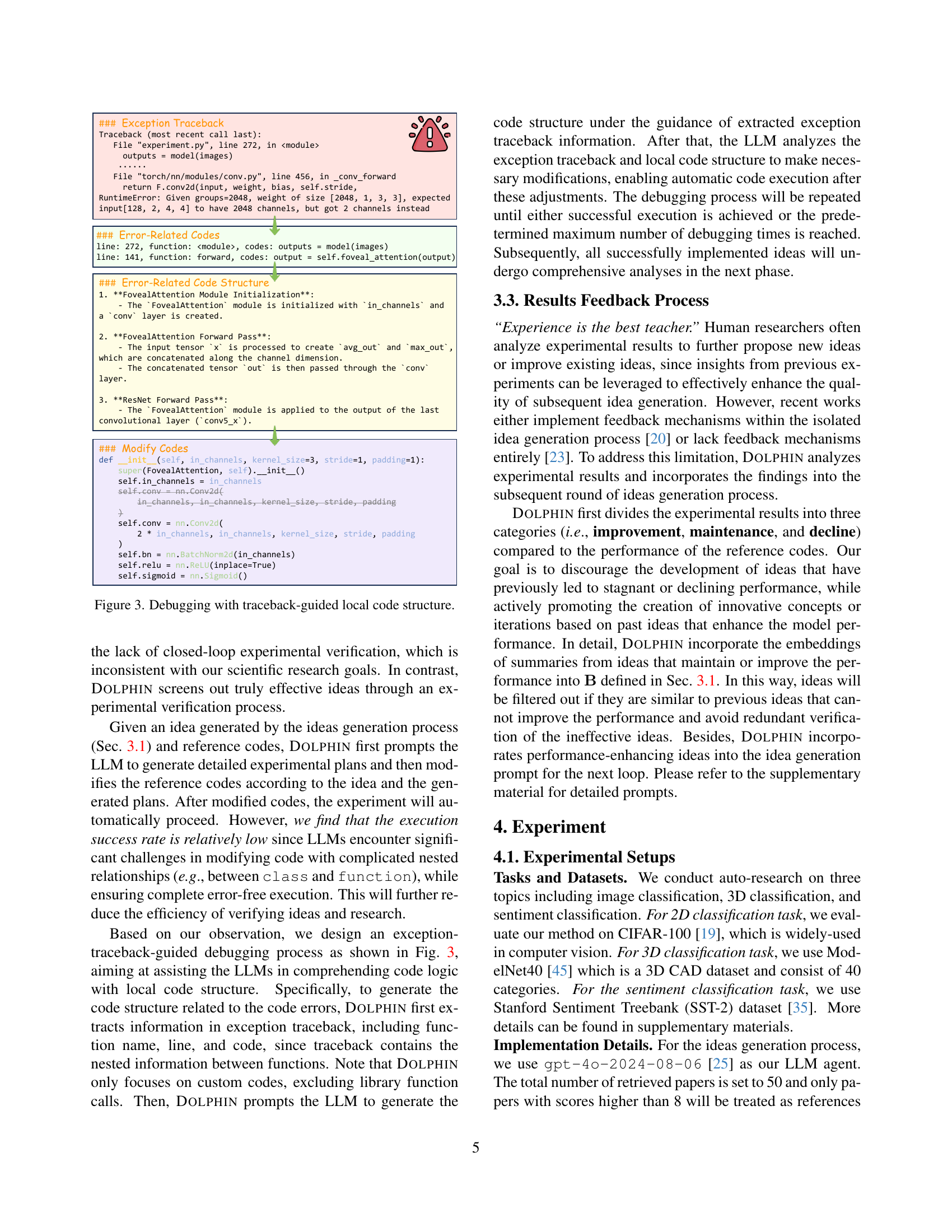

🔼 This figure illustrates DOLPHIN’s exception-traceback-guided debugging process. When an error occurs during code execution, DOLPHIN extracts information from the exception traceback, including the function name, line number, and code snippet causing the error. This information is used to guide the LLM in analyzing the local code structure and identifying the source of the error. The LLM then suggests code modifications to resolve the issue. The figure displays an example of an error (RuntimeError), the relevant code section, and the proposed modification to the code, demonstrating how DOLPHIN uses the traceback to pinpoint and correct errors automatically.

read the caption

Figure 3: Debugging with traceback-guided local code structure.

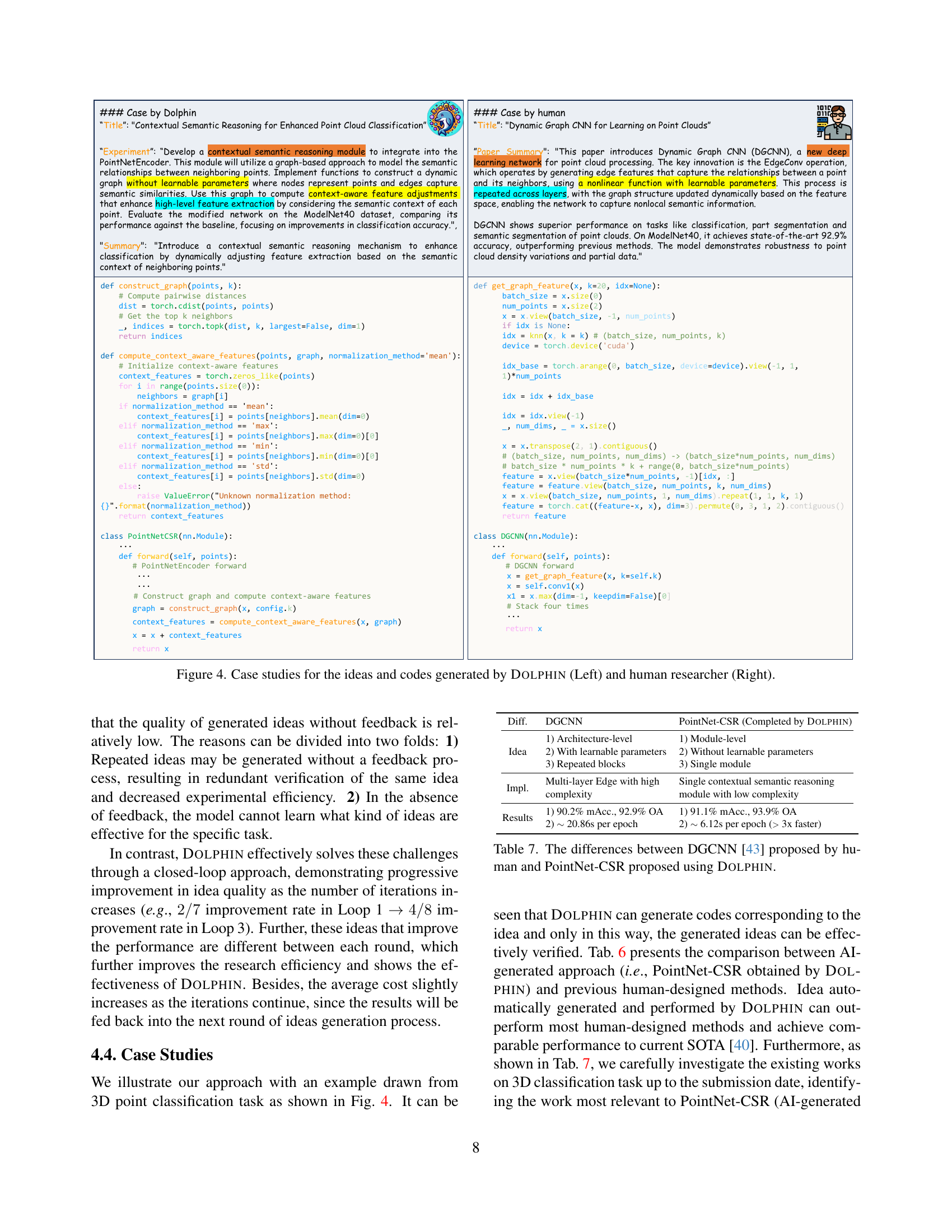

🔼 This figure presents a comparative case study of the idea generation and code implementation process between DOLPHIN and a human researcher. The left panel showcases DOLPHIN’s output: a novel idea for enhancing point cloud classification using contextual semantic reasoning, alongside the automatically generated code. The right panel shows an equivalent example from a human researcher, highlighting a similar task (dynamic graph CNN for point cloud processing) and associated code. The comparison illustrates DOLPHIN’s capacity to generate comparable research ideas and code relative to a human expert.

read the caption

Figure 4: Case studies for the ideas and codes generated by Dolphin (Left) and human researcher (Right).

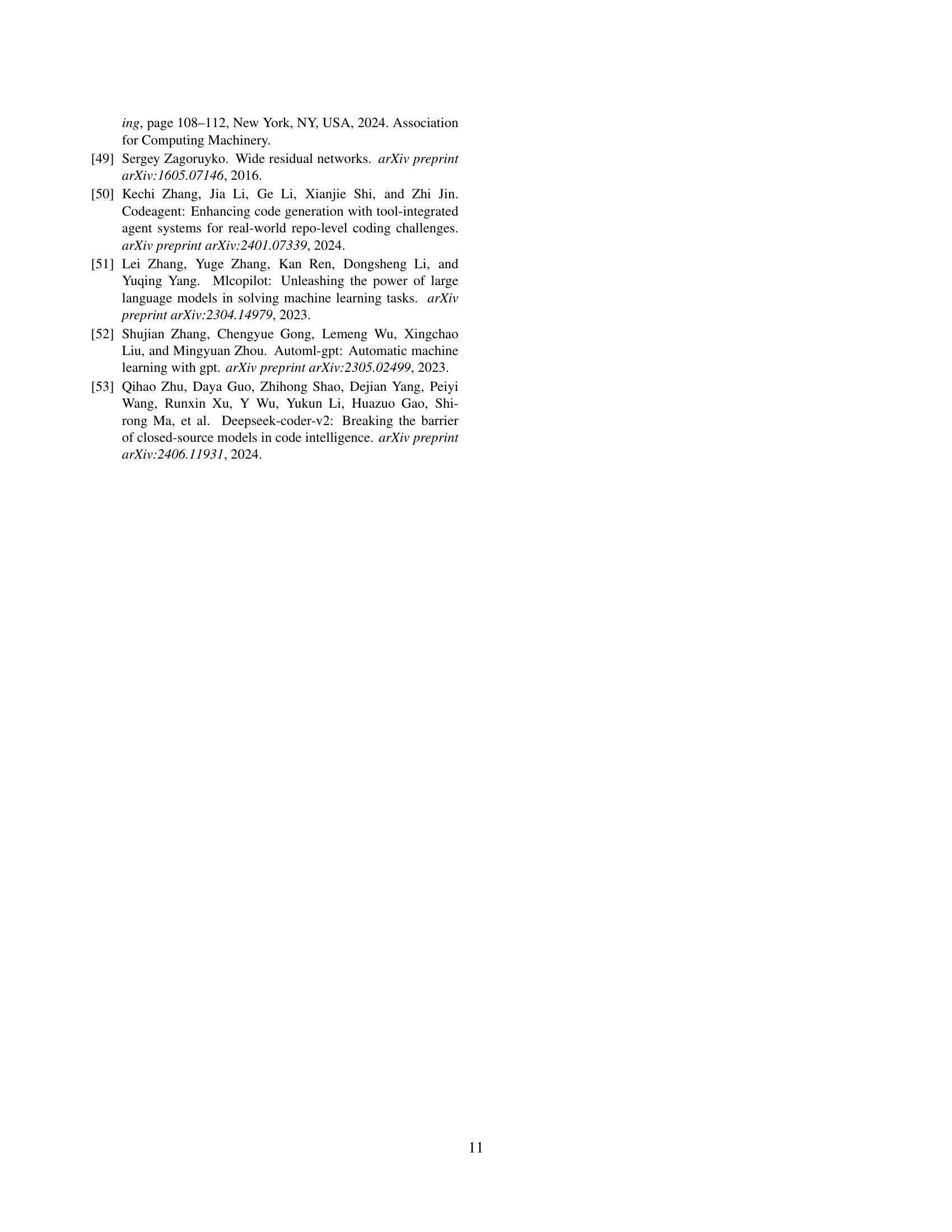

🔼 Figure 5 shows the three prompts used in the DOLPHIN framework for idea generation. The first prompt focuses on extracting relevant task attributes from a given topic description to guide the paper search process. The second prompt instructs the system to retrieve relevant papers using the Semantic Scholar API based on specified keywords. The third prompt guides the system to generate novel and non-redundant research ideas based on retrieved papers, taking into consideration existing knowledge and previous ideas. Each prompt specifies the required input format (e.g., JSON) for the response and guides the system towards generating high-quality ideas.

read the caption

Figure 5: Prompts of paper retrieval, paper ranking, and ideas generation.

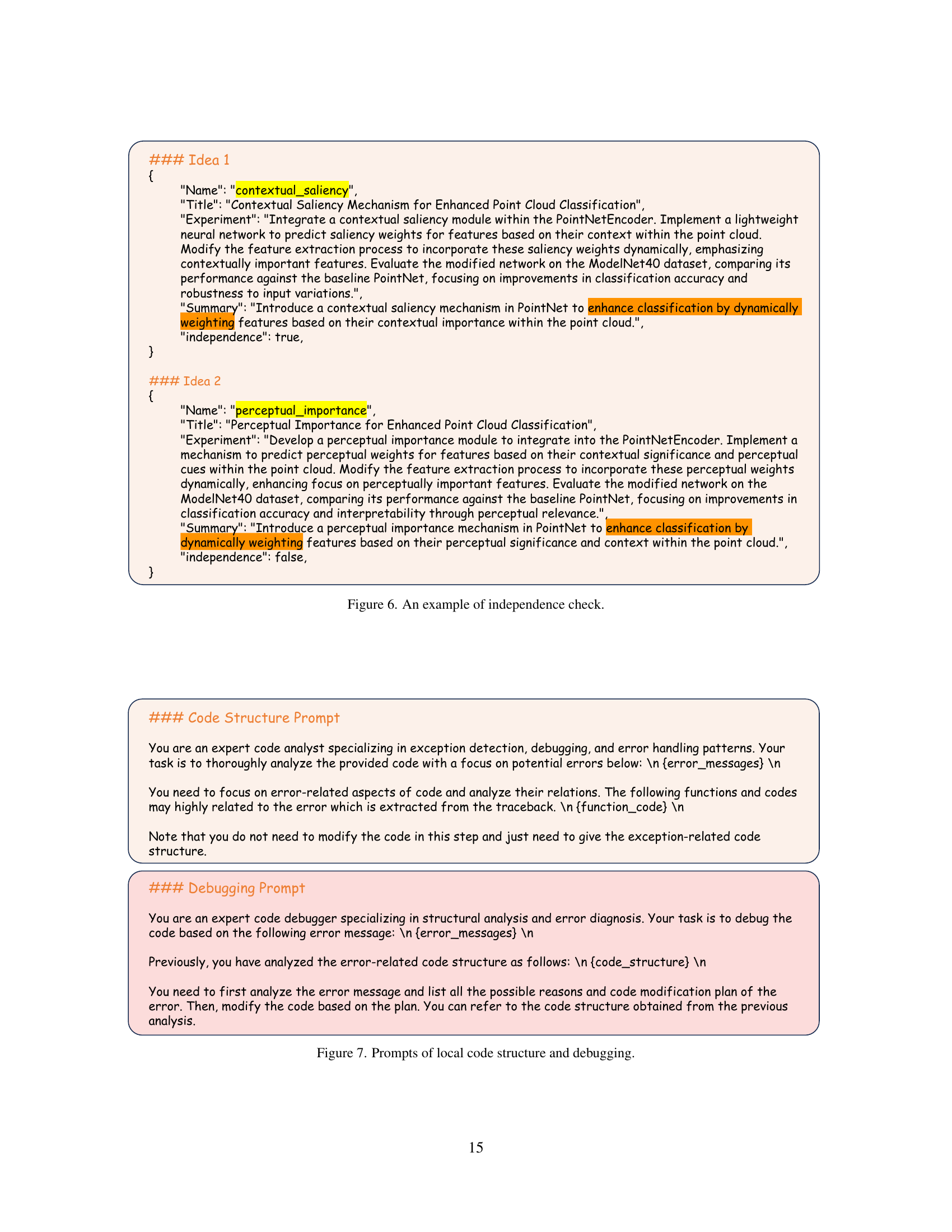

🔼 This figure displays an example of the independence check performed by DOLPHIN, a closed-loop open-ended auto-research framework. DOLPHIN aims to generate novel and non-redundant research ideas. The independence check ensures that newly generated ideas are distinct from those already considered. The figure shows two ideas, both aiming to improve point cloud classification using PointNet. Although the ideas have different titles and brief descriptions, a closer examination reveals a substantial overlap in their underlying methodologies. The independence check flags one as independent and the other as non-independent due to this similarity, preventing redundant experimentation.

read the caption

Figure 6: An example of independence check.

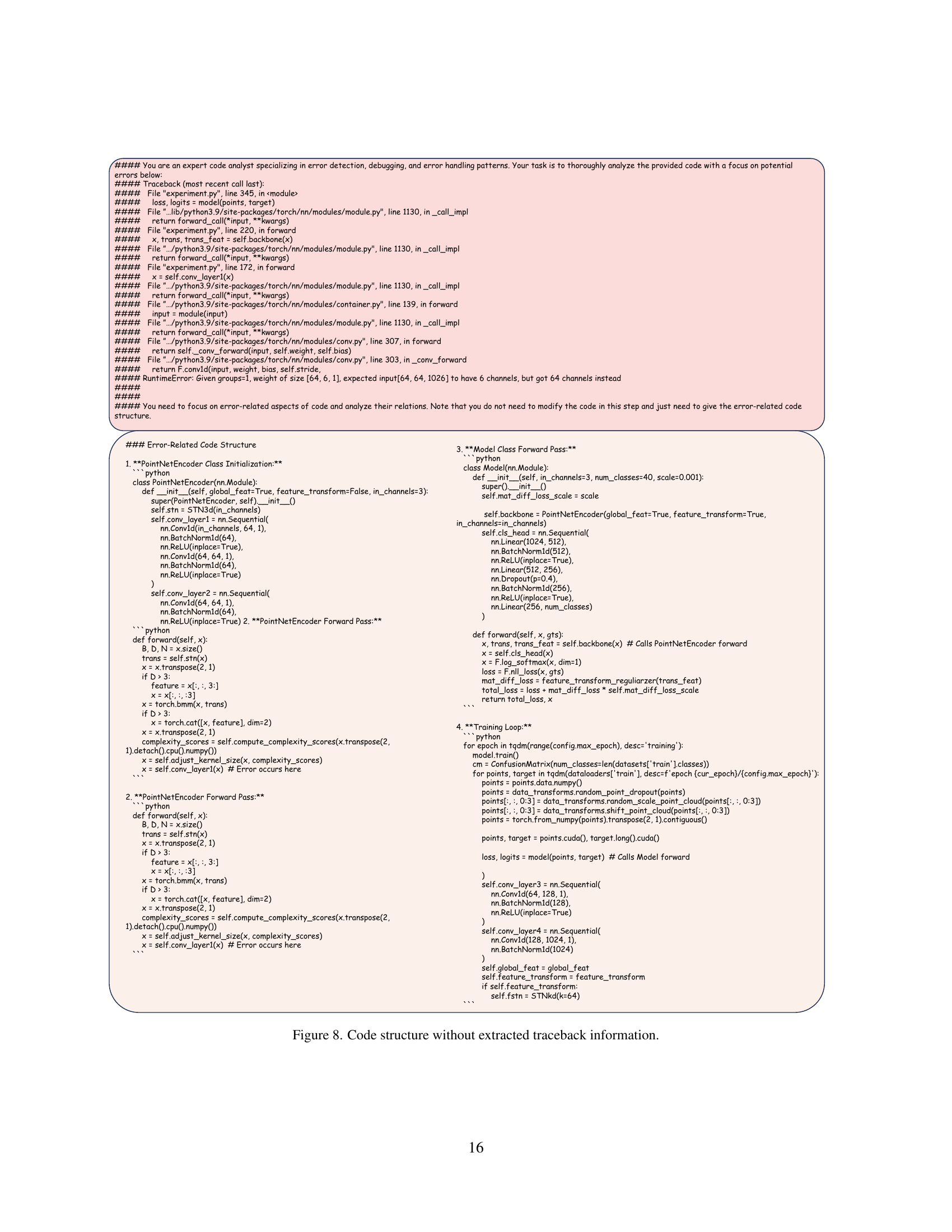

🔼 This figure shows the two prompts used in the DOLPHIN framework for debugging automatically generated code. The first prompt, ‘Code Structure Prompt’, instructs a large language model (LLM) to analyze error messages and traceback information to identify and extract the relevant code structure associated with the error. This structure is then provided to the second prompt, ‘Debugging Prompt,’ which guides the LLM to generate a plan to fix the error within the extracted code, making the necessary modifications and ensuring code functionality. This two-step process uses the LLM to debug automatically generated code, improving efficiency in the auto-research cycle.

read the caption

Figure 7: Prompts of local code structure and debugging.

🔼 Figure 8 shows the code structure before applying the exception-traceback-guided debugging process. The image displays sections of Python code related to a

PointNetEncoderclass and aModelclass, illustrating the code’s architecture and function calls involved in the forward pass of a neural network. This visualization is used to highlight the complexity of the codebase prior to the application of the debugging technique, emphasizing the challenges of automated debugging in this context.read the caption

Figure 8: Code structure without extracted traceback information.

🔼 Figure 9 showcases an example of an idea and its corresponding code generated by the DOLPHIN framework. The idea focuses on enhancing point cloud classification by incorporating a latent space exploration mechanism using an autoencoder. The code implements this mechanism, mapping point cloud data to a latent space for exploration before combining latent features with the original features for improved classification. The results demonstrate a significant performance improvement on the ModelNet40 dataset, achieving 92.34% overall accuracy (OA) and 89.54% mean accuracy (mAcc), representing improvements of +1.34% OA and +1.94% mAcc compared to the baseline PointNet model. This highlights DOLPHIN’s ability to generate effective and novel ideas within the scientific research process.

read the caption

Figure 9: Idea and codes generated by Dolphin which achieves 92.34% OA and 89.54% mAcc. on ModelNet40 (+1.34% OA and +1.94% mAcc. compared to our baseline).

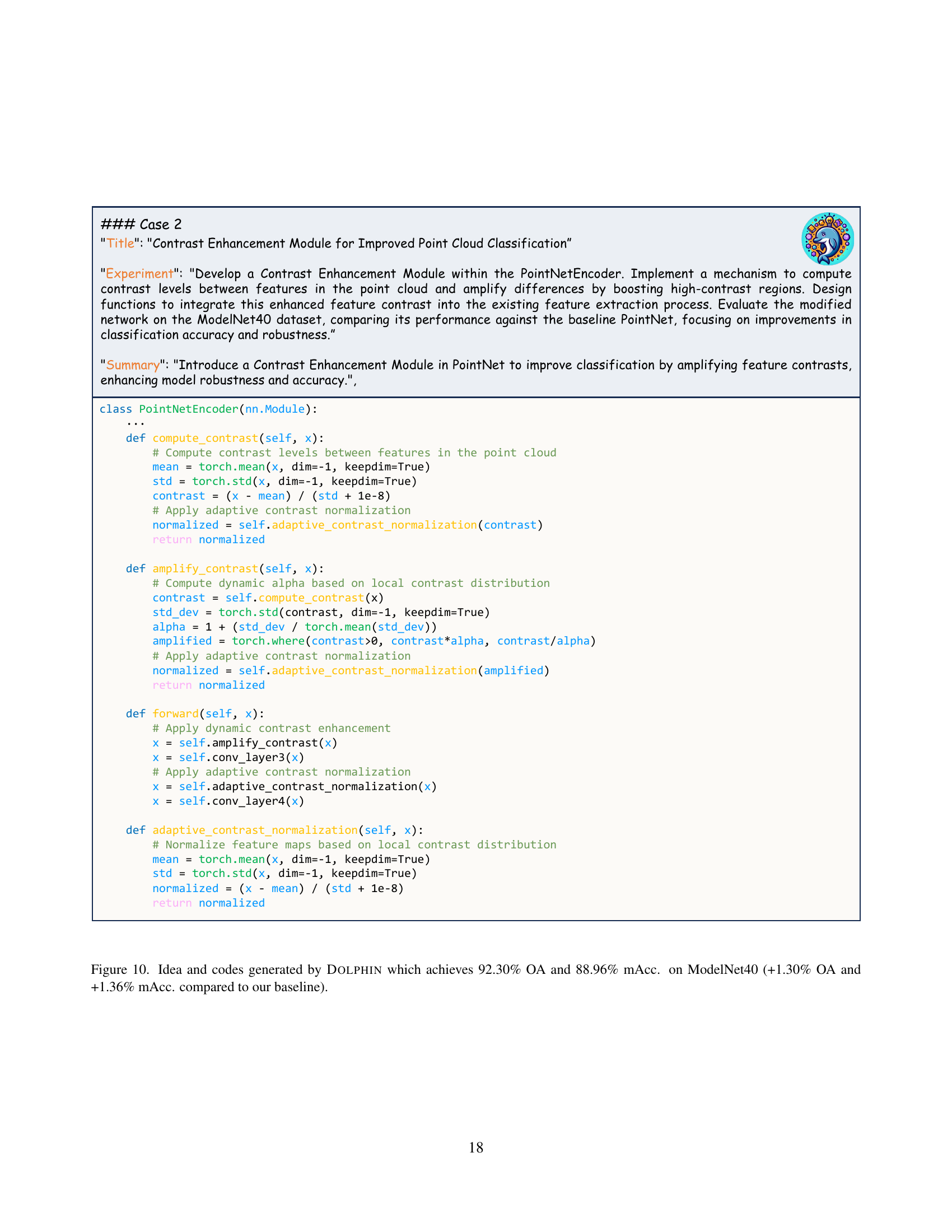

🔼 Figure 10 presents a case study showcasing DOLPHIN’s capabilities. DOLPHIN automatically generated a novel idea and corresponding code for enhancing 3D point cloud classification. This involved creating a ‘Contrast Enhancement Module’ within the PointNet architecture, designed to amplify the contrast between features to improve classification accuracy. The results demonstrate that this DOLPHIN-generated approach achieves 92.30% overall accuracy (OA) and 88.96% mean accuracy (mAcc) on the ModelNet40 dataset. This represents a significant improvement of +1.30% OA and +1.36% mAcc compared to the baseline PointNet model.

read the caption

Figure 10: Idea and codes generated by Dolphin which achieves 92.30% OA and 88.96% mAcc. on ModelNet40 (+1.30% OA and +1.36% mAcc. compared to our baseline).

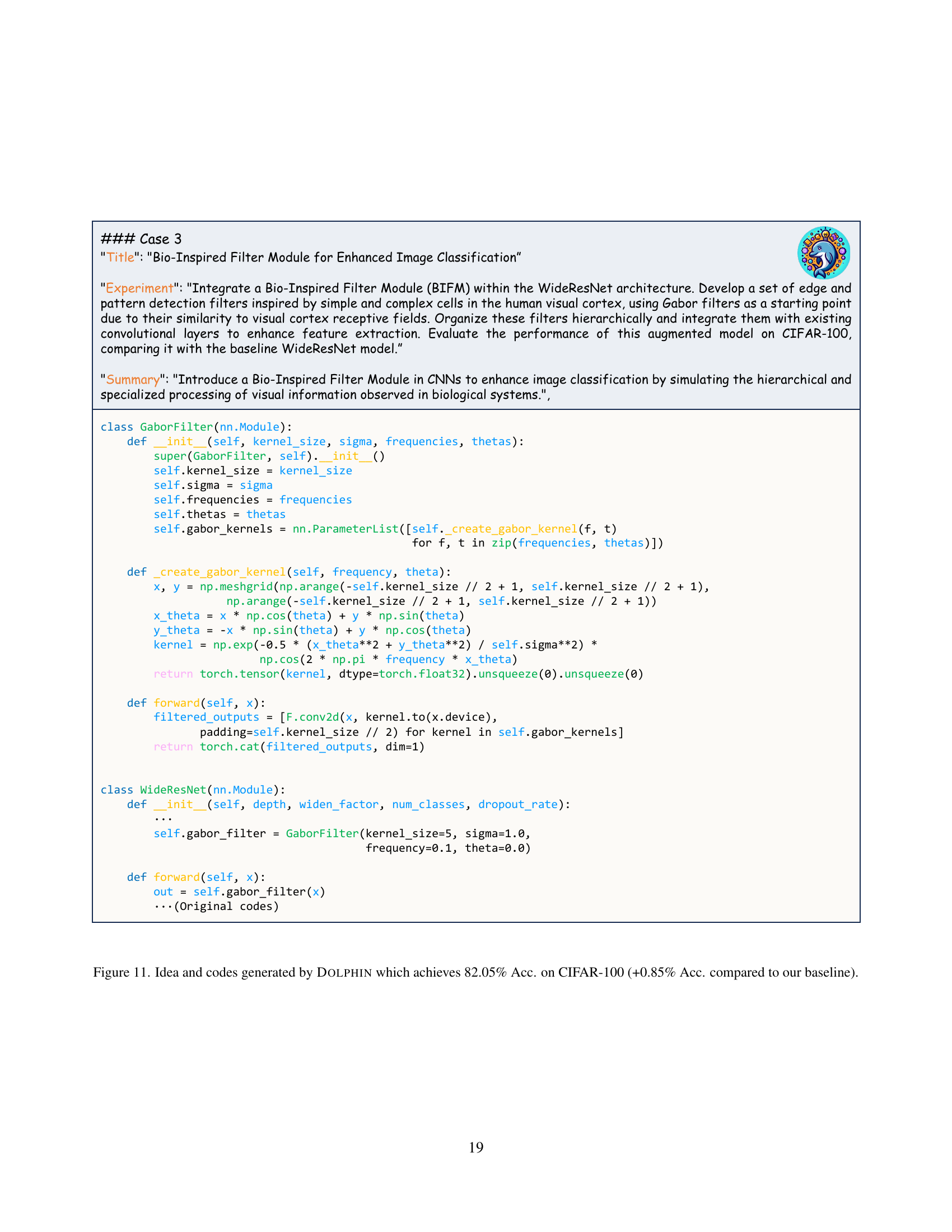

🔼 Figure 11 presents a case study from the DOLPHIN system, showcasing its ability to generate novel research ideas and corresponding code. Specifically, it details an idea for enhancing image classification accuracy on the CIFAR-100 benchmark dataset by integrating a bio-inspired filter module into the WideResNet architecture. This module mimics the functionality of the human visual cortex, using Gabor filters to detect edges and patterns. The generated code implements this module, demonstrating DOLPHIN’s capacity for both conceptual innovation and functional code generation. The result shows a performance improvement of +0.85% in accuracy compared to the baseline WideResNet.

read the caption

Figure 11: Idea and codes generated by Dolphin which achieves 82.05% Acc. on CIFAR-100 (+0.85% Acc. compared to our baseline).

More on tables

| Method | Novelty | Cost (Avg.) |

|---|---|---|

| Naive generation | 8 / 20 | $0.106 |

| Generation with naive retrieval | 13 / 20 | $0.187 |

| Ours (task attribute filtering) | 19 / 20 | $0.184 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of three different approaches to idea generation within the DOLPHIN framework. The first approach is a naive generation method, the second incorporates naive retrieval of papers, and the third is the proposed DOLPHIN method which uses task-attribute filtering to improve relevance. For each approach, the table shows the number of novel ideas generated (as assessed by GPT-4-2024-08-06) out of a total of 20, alongside the average cost per idea, including the costs of paper retrieval, idea generation, and novelty checks. This allows for analysis of the cost-effectiveness and idea generation quality of each approach. The goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed task-attribute filtering in producing more novel ideas at a comparable or lower cost.

read the caption

Table 2: Results of ideas generation process. The novelty is evaluated by gpt-4o-2024-08-06. Cost (Avg.) is the cost per idea including paper retrieval, ideas generation, and novelty check.

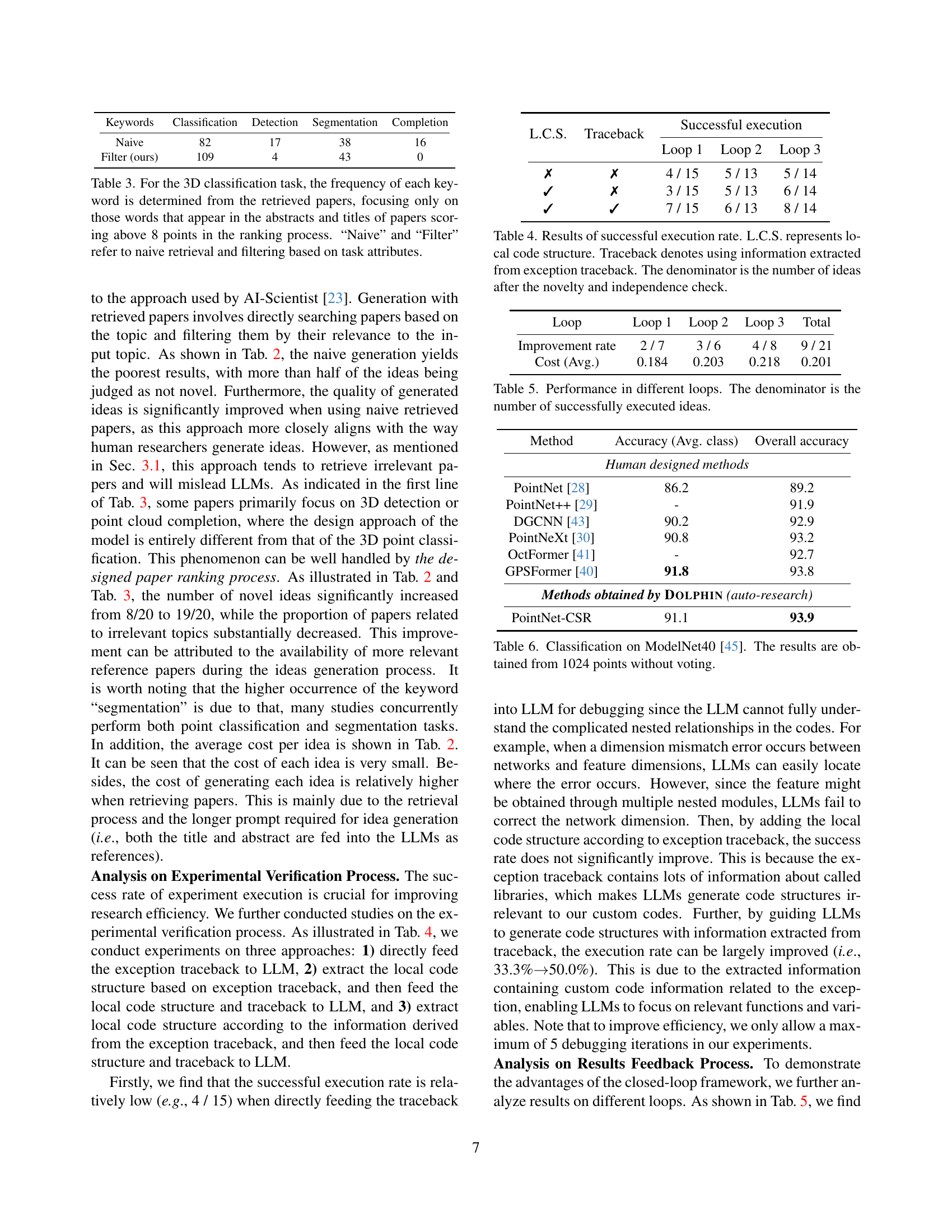

| Keywords | Classification | Detection | Segmentation | Completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | 82 | 17 | 38 | 16 |

| Filter (ours) | 109 | 4 | 43 | 0 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative analysis of keywords extracted from research papers related to 3D classification. Only papers with a score above 8 (indicating high relevance) in a pre-processing ranking step were included in the analysis. The keyword frequencies are compared between two approaches: a ’naive’ method (direct keyword search), and a method employing ‘filtering’ based on task attributes. This comparison highlights the impact of attribute-based filtering on retrieving relevant papers for the 3D classification task.

read the caption

Table 3: For the 3D classification task, the frequency of each keyword is determined from the retrieved papers, focusing only on those words that appear in the abstracts and titles of papers scoring above 8 points in the ranking process. “Naive” and “Filter” refer to naive retrieval and filtering based on task attributes.

| L.C.S. | Traceback | Successful execution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \usym2717 | \usym2717 | 4 / 15 | 5 / 13 | 5 / 14 | |

| \usym2713 | \usym2717 | 3 / 15 | 5 / 13 | 6 / 14 | |

| \usym2713 | \usym2713 | 7 / 15 | 6 / 13 | 8 / 14 |

🔼 This table presents the success rates of code execution in the experimental verification process of the DOLPHIN framework. Three different approaches are compared: using only the exception traceback, incorporating the local code structure (L.C.S.) along with the traceback, and extracting the L.C.S. from the traceback before feeding it to the LLM. The success rate is calculated as the number of successfully executed ideas divided by the total number of ideas after novelty and independence checks. The results show a significant improvement in execution rate when using local code structure information.

read the caption

Table 4: Results of successful execution rate. L.C.S. represents local code structure. Traceback denotes using information extracted from exception traceback. The denominator is the number of ideas after the novelty and independence check.

| Loop | Loop 1 | Loop 2 | Loop 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement rate | 2 / 7 | 3 / 6 | 4 / 8 | 9 / 21 |

| Cost (Avg.) | 0.184 | 0.203 | 0.218 | 0.201 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of DOLPHIN across three different loops of the research process. It shows the improvement rate, calculated as the number of successful experiments that resulted in performance gains divided by the total number of successfully executed ideas. The average cost per idea is also given for each loop. This data illustrates how the efficiency and effectiveness of DOLPHIN evolves across iterations, demonstrating improvement in performance over time.

read the caption

Table 5: Performance in different loops. The denominator is the number of successfully executed ideas.

| Method | Accuracy (Avg. class) | Overall accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Human designed methods | ||

| PointNet [28] | 86.2 | 89.2 |

| PointNet++ [29] | - | 91.9 |

| DGCNN [43] | 90.2 | 92.9 |

| PointNeXt [30] | 90.8 | 93.2 |

| OctFormer [41] | - | 92.7 |

| GPSFormer [40] | 91.8 | 93.8 |

| Methods obtained by Dolphin (auto-research) | ||

| PointNet-CSR | 91.1 | 93.9 |

🔼 Table 6 presents the classification results on the ModelNet40 dataset [45], a widely used benchmark in 3D point cloud analysis. The model’s performance is evaluated using 1024 points per sample, without employing any voting mechanisms to combine predictions from multiple parts of the model. This setup provides a clear and direct evaluation of the model’s inherent ability to classify 3D shapes based on their point cloud representations.

read the caption

Table 6: Classification on ModelNet40 [45]. The results are obtained from 1024 points without voting.

| Diff. | DGCNN | PointNet-CSR (Completed by Dolphin) |

|---|---|---|

| Idea | 1) Architecture-level | 1) Module-level |

| 2) With learnable parameters | 2) Without learnable parameters | |

| 3) Repeated blocks | 3) Single module | |

| Impl. | Multi-layer Edge with high complexity | Single contextual semantic reasoning module with low complexity |

| Results | 1) 90.2% mAcc., 92.9% OA | 1) 91.1% mAcc., 93.9% OA |

| 2) ~ 20.86s per epoch | 2) ~ 6.12s per epoch (> 3x faster) |

🔼 This table compares the human-designed Dynamic Graph CNN (DGCNN) model with the PointNet-CSR model generated by the DOLPHIN framework. It highlights key architectural differences, including the level of design (architecture vs. module), the use of learnable parameters, the number of repeated blocks used, and the overall complexity of the model. The table also presents a comparison of the model’s performance (mAcc and OA), as well as training efficiency in terms of time per epoch.

read the caption

Table 7: The differences between DGCNN [43] proposed by human and PointNet-CSR proposed using Dolphin.

Full paper#