↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

The scientific research process, while effective, is often hampered by time constraints, human limitations, and resource scarcity. This paper explores how Large Language Models (LLMs) can address these limitations by automating various stages of research, from hypothesis generation and experiment planning to writing and peer review. Existing efforts have used LLMs for literature-based discovery and inductive reasoning tasks, demonstrating potential for novel findings.

This research systematically analyzes the role of LLMs in the four main stages of scientific research. It presents task-specific methodologies and evaluation benchmarks, highlighting the transformative potential of LLMs while also identifying current challenges and offering insights into future research directions. The survey concludes that LLMs, although limited by several factors, show promise for revolutionizing various research processes and boosting productivity. This work provides a comprehensive overview of current developments and serves as a guide for the wider scientific community interested in incorporating LLMs into scientific research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers as it systematically reviews the applications of Large Language Models (LLMs) across all stages of scientific research. It identifies challenges and proposes future research directions, stimulating further innovation and collaboration in the field. The comprehensive overview and identification of limitations in current LLM applications will be highly valuable for researchers seeking to leverage LLMs effectively in their work.

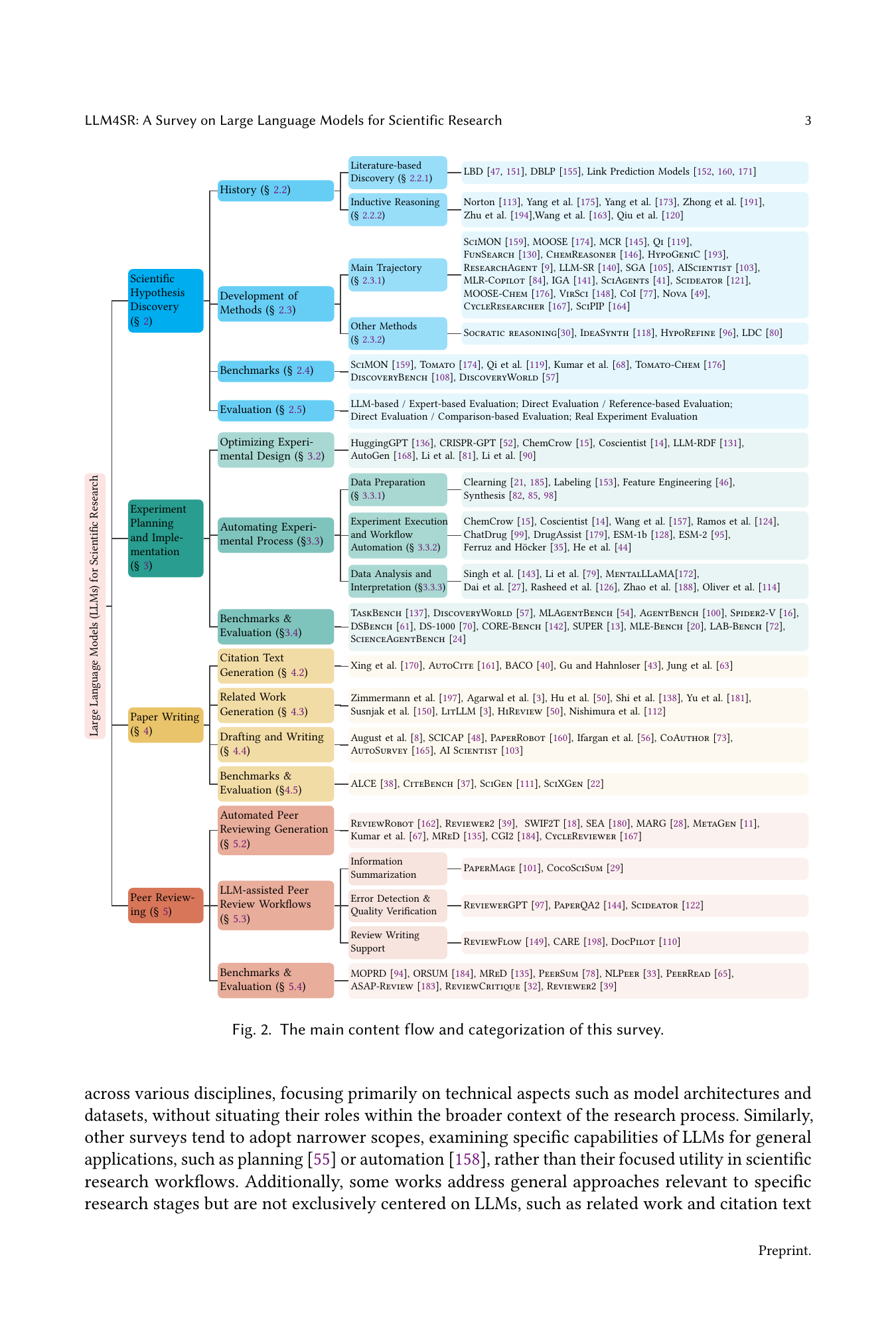

Visual Insights#

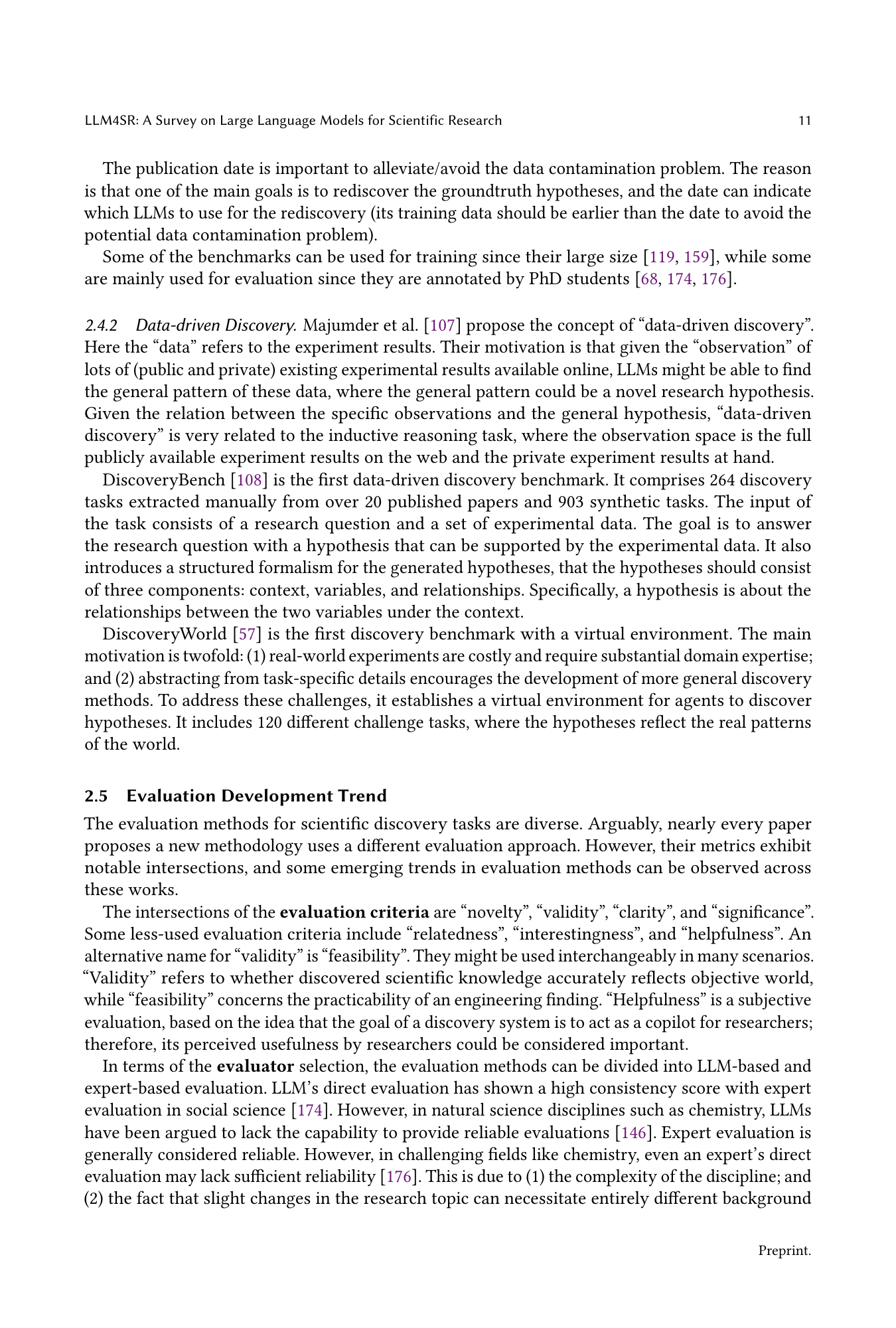

| Methods | Inspiration Retrieval Strategy | NF | VF | CF | EA | LMI | R | AQC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SciMON [Wang et al., 2024a] | Semantic & Concept & Citation Neighbors | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MOOSE [Yang et al., 2024a] | LLM Selection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ |

| MCR [Sprueill et al., 2023] | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Qi [Qi et al., 2023] | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - |

| FunSearch [Romera-Paredes et al., 2024] | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| ChemReasoner [Sprueill et al., 2024] | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| HypoGeniC [Zhou et al., 2024b] | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| ResearchAgent [Baek et al., 2024] | Concept Co-occurrence Neighbors | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| LLM-SR [Shojaee et al., 2024] | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| SGA [Ma et al., 2024] | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| AIScientist [Lu et al., 2024] | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| MLR-Copilot [Li et al., 2024f] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| IGA [Si et al., 2024] | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| SciAgents [Ghafarollahi and Buehler, 2024] | Random Selection | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Scideator [Radensky et al., 2024a] | Semantic & Concept Matching | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MOOSE-Chem [Yang et al., 2024b] | LLM selection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| VirSci [Su et al., 2024] | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ |

| CoI [Li et al., 2024g] | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Nova [Hu et al., 2024a] | LLM selection | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| CycleResearcher [Weng et al., 2024] | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| SciPIP [Wang et al., 2024b] | Semantic & Concept & Citation Neighbors | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

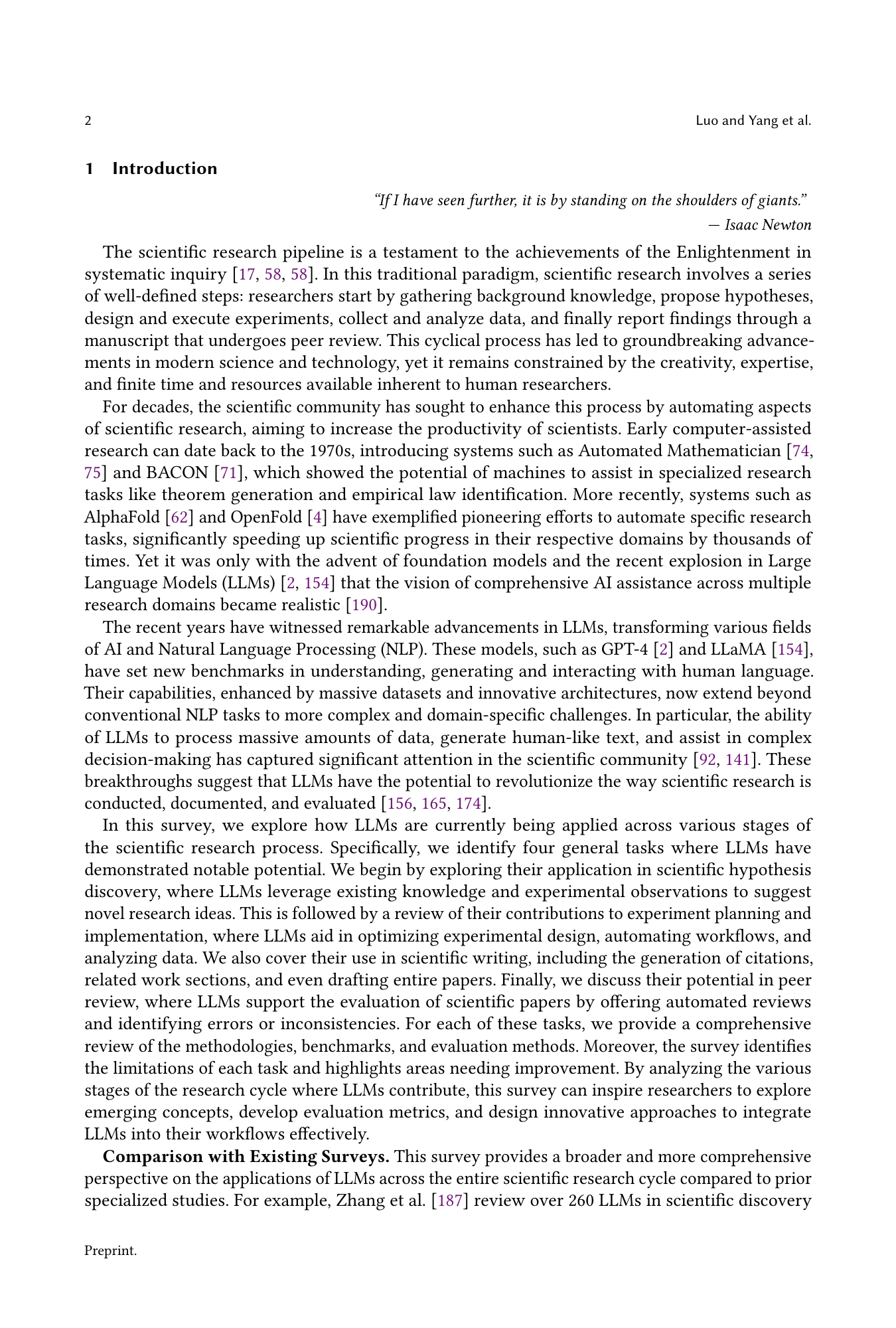

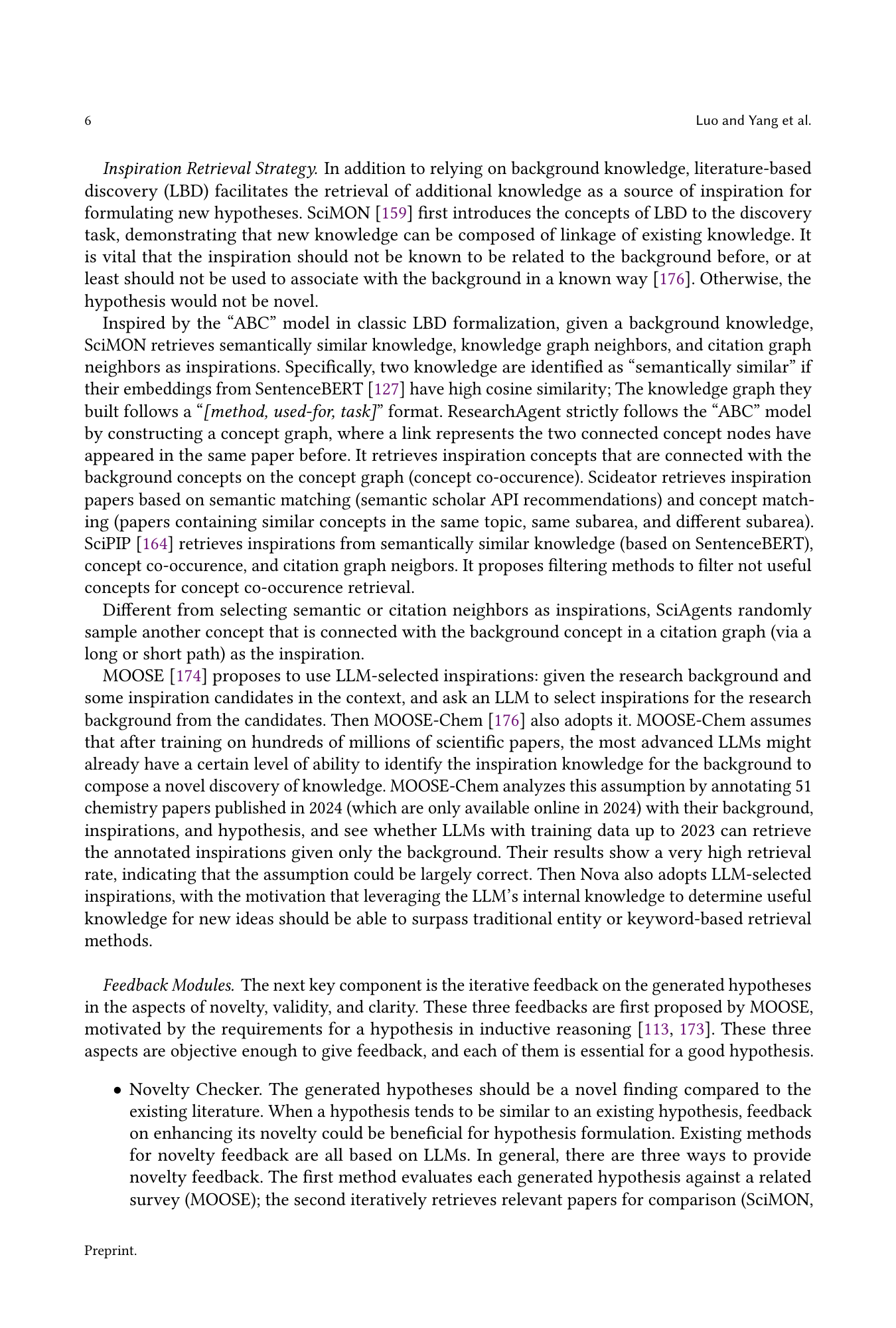

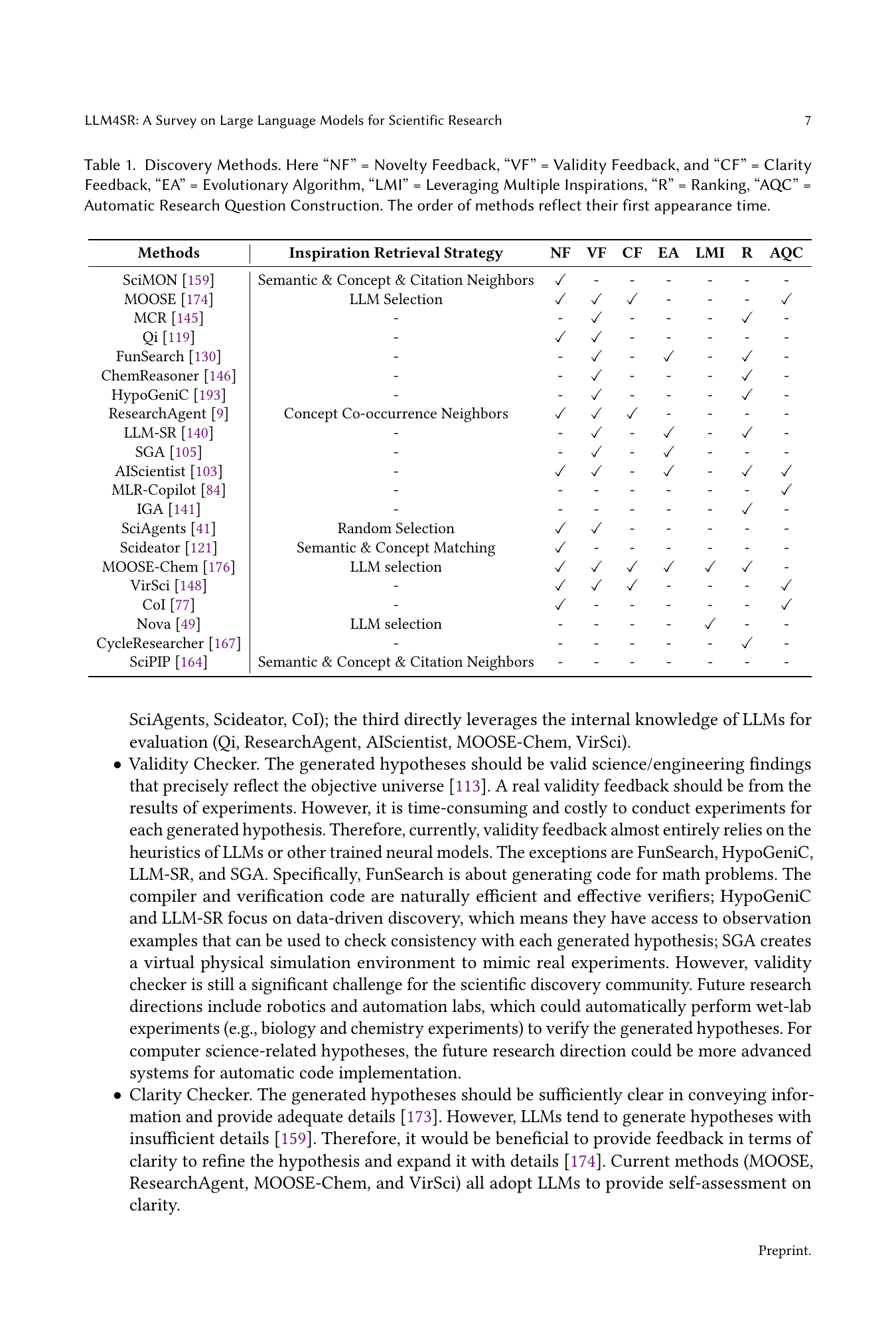

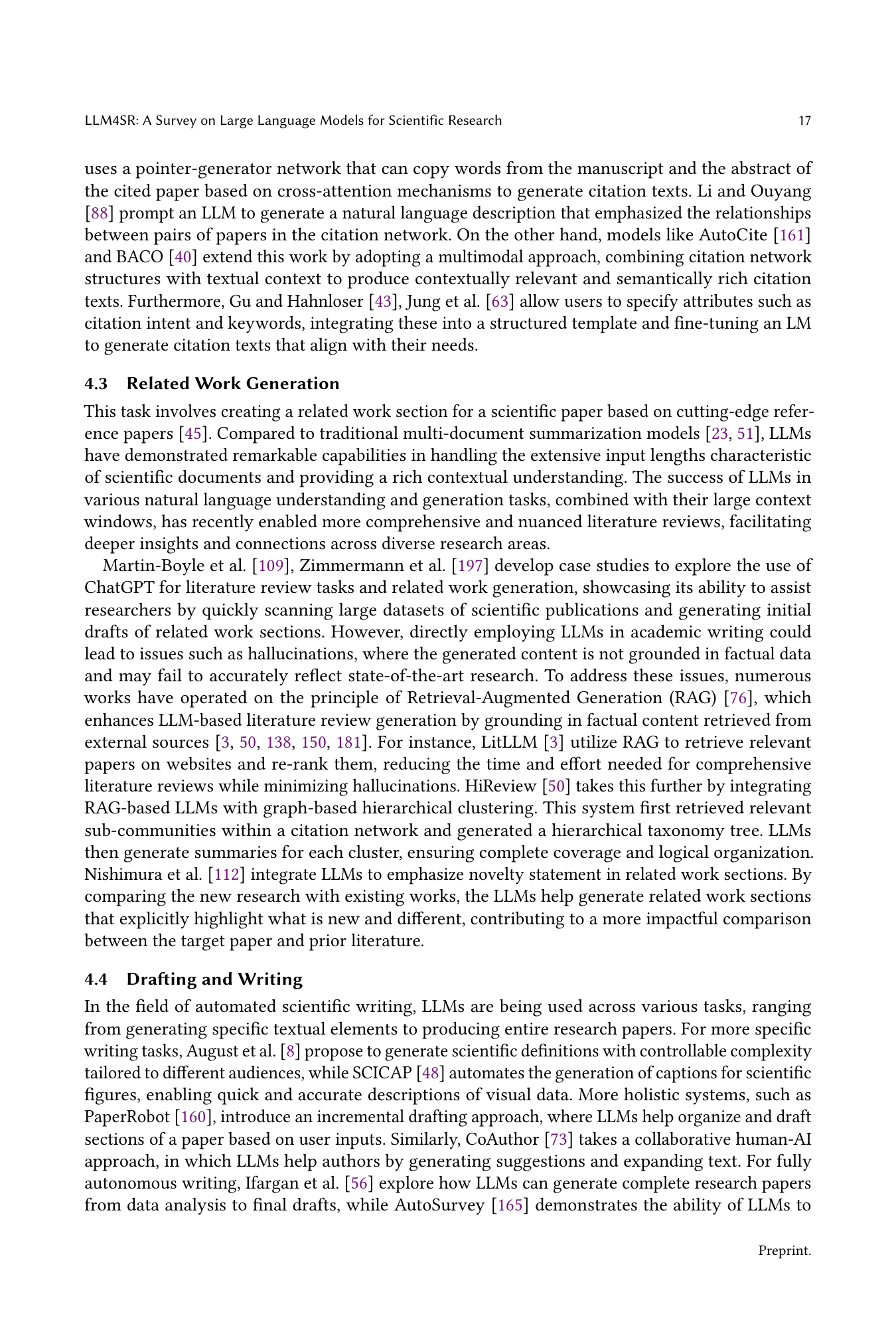

🔼 This table summarizes the key characteristics and components of various methods used for scientific hypothesis discovery. It contrasts different approaches to literature-based discovery (LBD) and inductive reasoning, showcasing their use of inspiration retrieval strategies, feedback mechanisms (novelty, validity, and clarity), evolutionary algorithms, and techniques for leveraging multiple inspirations and ranking hypotheses. It also indicates whether each method incorporates automated research question construction. The methods are ordered chronologically by their first appearance in the scientific literature.

read the caption

Table 1. Discovery Methods. Here “NF” = Novelty Feedback, “VF” = Validity Feedback, and “CF” = Clarity Feedback, “EA” = Evolutionary Algorithm, “LMI” = Leveraging Multiple Inspirations, “R” = Ranking, “AQC” = Automatic Research Question Construction. The order of methods reflect their first appearance time.

In-depth insights#

LLM-Driven Discovery#

LLM-driven discovery represents a paradigm shift in scientific research, leveraging the power of large language models to accelerate the hypothesis generation process. Instead of relying solely on human intuition and exhaustive literature reviews, LLMs can analyze vast datasets of scientific literature and experimental data to identify patterns and suggest novel hypotheses. This approach offers the potential to significantly speed up the research cycle and uncover previously undiscovered relationships between existing concepts. However, challenges remain. Ensuring the validity and novelty of LLM-generated hypotheses is crucial, requiring robust evaluation methods and careful consideration of potential biases in the training data. The ethical implications of using LLMs for discovery, such as concerns about intellectual property and the potential for automation bias, must also be thoroughly addressed. Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of LLM-driven discovery are substantial. It could lead to faster scientific progress, the exploration of novel research areas, and the democratization of scientific discovery, potentially making cutting-edge research more accessible to a broader range of researchers.

Experiment Automation#

Automating experiments using LLMs presents a transformative opportunity for scientific research. LLMs can streamline various stages, from initial experimental design and optimization to execution and data analysis. By leveraging LLMs’ ability to process vast amounts of data and generate human-like text, researchers can optimize experimental workflows, enhancing efficiency and reducing human error. LLMs can decompose complex experiments into smaller, manageable sub-tasks, making them more approachable and facilitating collaboration. Furthermore, LLMs can automate data preparation tasks, such as cleaning and labeling, freeing up researchers’ time for higher-level tasks. However, challenges remain: LLMs’ capacity for complex planning and the potential for inaccuracies (hallucinations) need careful consideration. To fully realize the potential of experiment automation with LLMs, robust validation methods and human-in-the-loop systems are essential to ensure reliability and accuracy. The ethical implications of using LLMs to automate scientific processes should also be carefully addressed.

AI-Augmented Writing#

AI-augmented writing represents a paradigm shift in scholarly communication, offering both exciting possibilities and significant challenges. Automation of traditionally time-consuming tasks, such as citation generation, reference management, and initial draft creation, promises increased efficiency and productivity for researchers. LLMs can assist in generating text, identifying relevant literature, and even drafting entire sections of a paper, allowing authors to focus on higher-level tasks like analysis and argumentation. However, the integration of AI also raises concerns about potential biases, ethical considerations, and the maintenance of academic integrity. Ensuring factual accuracy, avoiding plagiarism, and retaining human oversight to guarantee the originality and quality of the work are crucial considerations. The potential for algorithmic bias and the homogenization of writing styles warrant ongoing evaluation. Effective implementation requires careful attention to human-in-the-loop systems, robust evaluation metrics, and clear ethical guidelines to ensure responsible AI integration within the research process. Future development must balance automation with human oversight to leverage the strengths of both while mitigating potential risks. The ultimate success of AI-augmented writing hinges on achieving a responsible and ethical implementation that enhances, rather than replaces, the crucial role of human researchers in creating and disseminating knowledge.

Automated Reviewing#

Automated reviewing, a rapidly evolving field, leverages AI, particularly large language models (LLMs), to streamline the peer-review process. While offering the potential for increased efficiency and consistency, this technology also introduces significant challenges. LLMs can provide valuable assistance in tasks like summarization, error detection, and initial assessment, but they cannot replace the critical thinking and judgment of human experts. Bias, hallucination, and a lack of nuanced understanding of specialized scientific domains remain significant limitations. Successful implementation requires careful consideration of ethical implications, including addressing issues of transparency and potential biases, and the establishment of robust evaluation methodologies to compare and contrast AI-generated reviews with those produced by humans. The future of automated reviewing lies in the development of human-AI collaborative workflows, which leverage the strengths of both human expertise and AI capabilities to enhance the overall quality and efficiency of the peer-review process.

Future of LLMs in Science#

The future of LLMs in science is incredibly promising, with the potential to revolutionize research across all stages. LLMs can automate numerous tedious tasks, freeing up scientists to focus on higher-level thinking and creative problem-solving. This includes accelerating hypothesis generation, optimizing experimental design and execution, analyzing massive datasets, and even drafting scientific papers. However, challenges remain. These include addressing potential biases, improving the reliability and accuracy of LLM outputs, ensuring transparency and accountability in their use, and resolving ethical concerns surrounding authorship and intellectual property. Successful integration will likely depend on collaborative human-AI workflows, where LLMs serve as powerful tools to assist researchers, rather than replace them entirely. Further research is necessary to develop more robust evaluation metrics, explore strategies for enhancing LLM reasoning and interpretability, and establish ethical guidelines for responsible use in scientific discovery and publication.

More visual insights#

More on tables

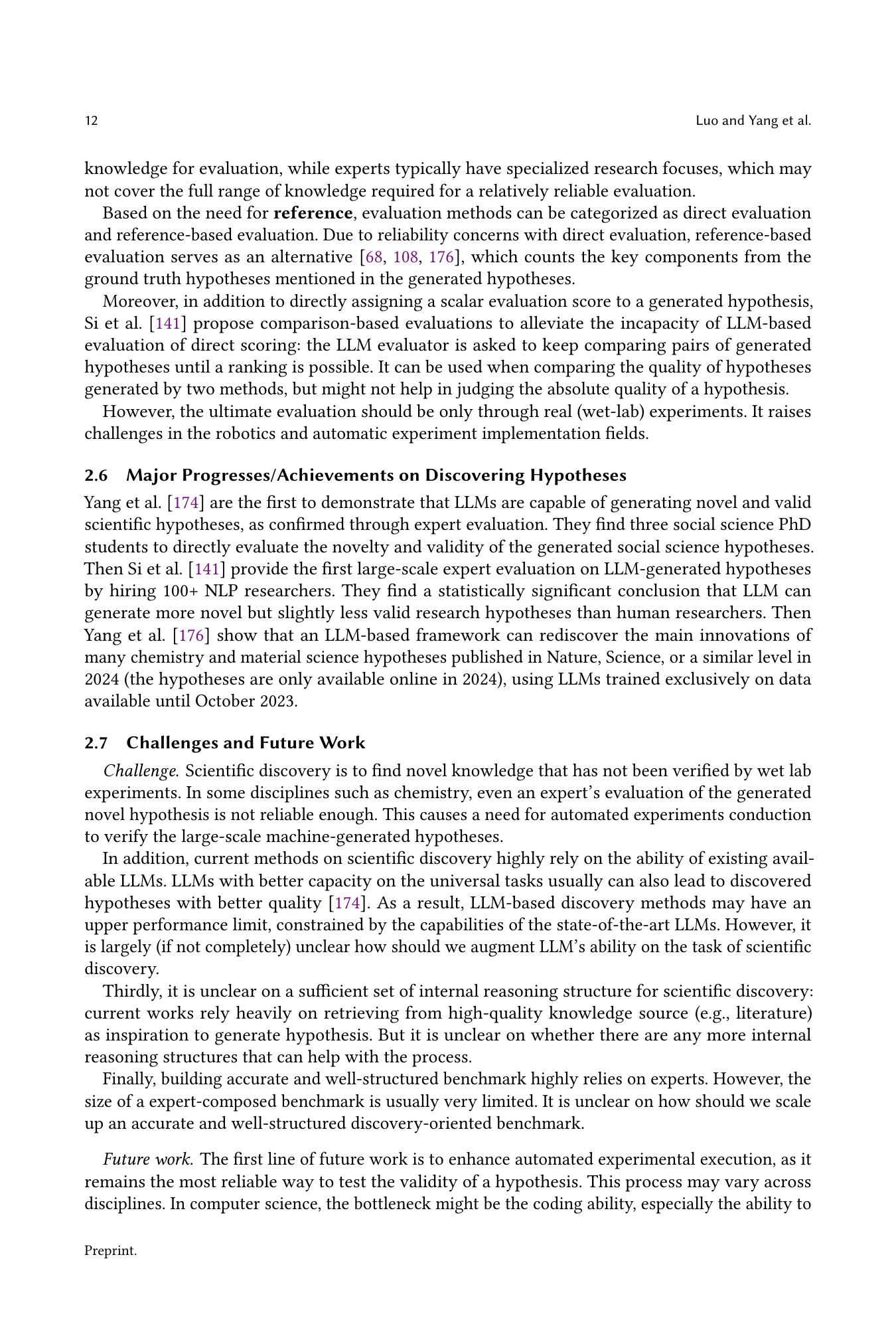

| Name | Annotator | RQ | BS | I | H | Size | Discipline | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SciMON (Wang et al., 2024a) | IE models | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | 67,408 | NLP & Biomedical | from 1952 to June 2022 (NLP) |

| Tomato (Yang et al., 2024a) | PhD students | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | 50 | Social Science | from January 2023 |

| Qi et al. (2023) | ChatGPT | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | 2900 | Biomedical | from August 2023 (test set) |

| Kumar et al. (2024) | PhD students | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | 100 | Five disciplines | from January 2022 |

| Tomato-Chem (Yang et al., 2024b) | PhD students | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 51 | Chemistry & Material Science | from January 2024* |

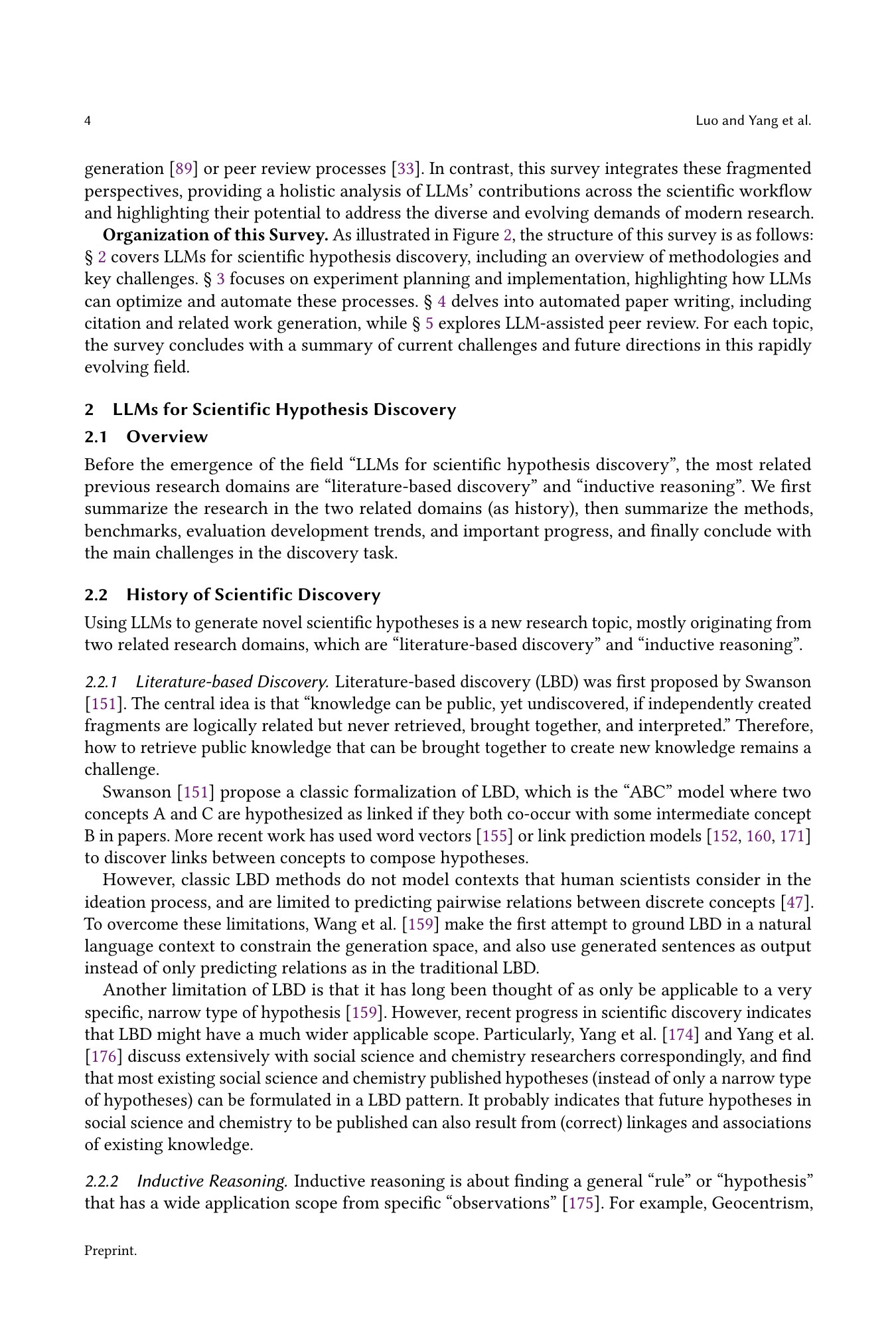

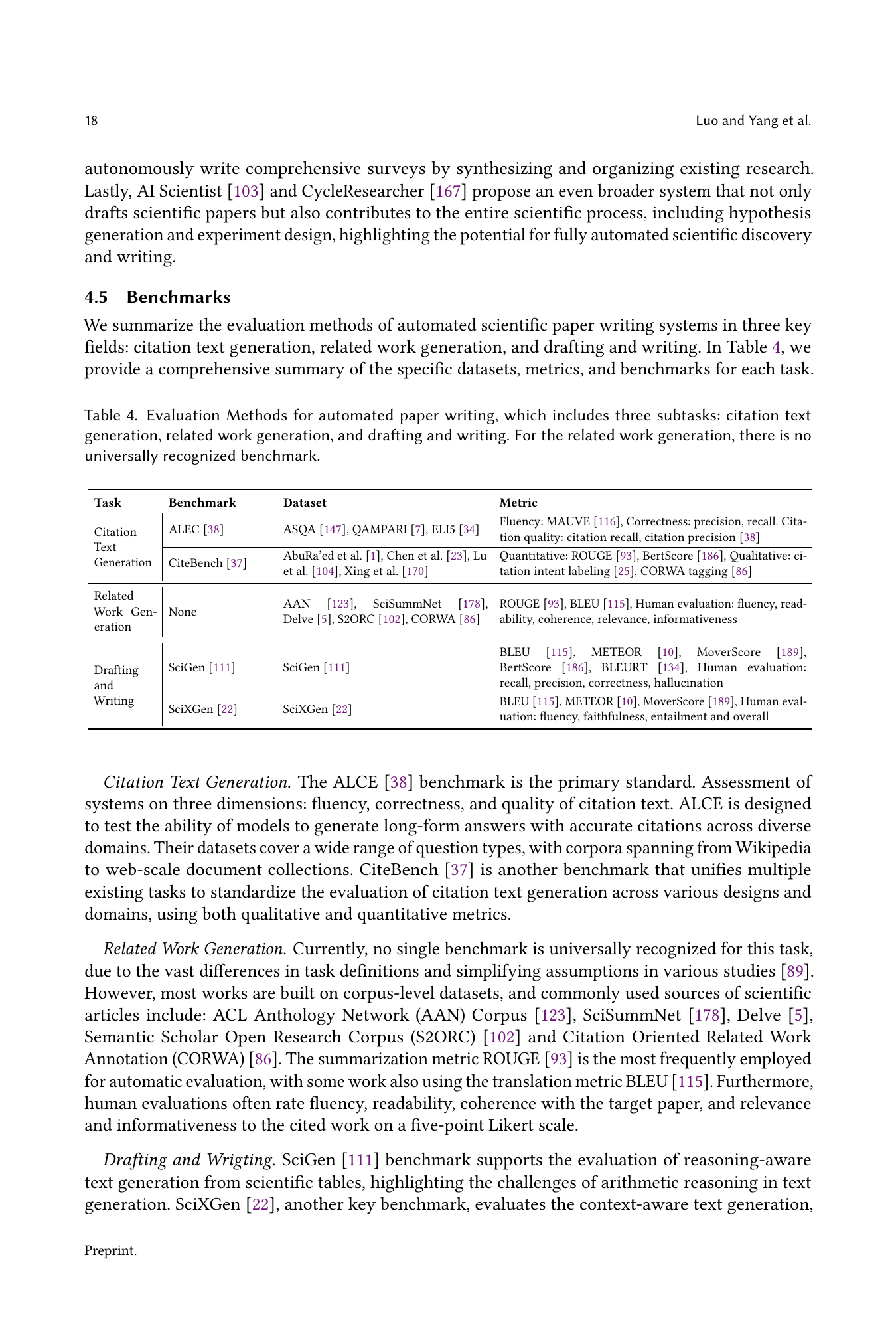

🔼 Table 2 presents benchmarks for evaluating methods that aim to discover novel scientific findings using large language models. The table compares different methods across several key features. These features include the source of annotations used to create the benchmark (human annotators vs. AI models), the presence or absence of a research question, background survey, inspiration, and hypothesis within the dataset, the size of the dataset (number of papers), the disciplines covered (Biomedical, Social Science, Chemistry, Computer Science, Economics, Medical, Physics), and finally, the date range covered by the dataset. Noteworthy points highlighted are the upper limit of the Biomedical data in SciMON to January 2024, the inclusion of a training dataset with papers published prior to January 2023 in Qi et al. (2023), and the criteria for the * symbol in the date column indicating that the papers had not been available online prior to the date.

read the caption

Table 2. Discovery benchmarks aiming for novel scientific findings. The Biomedical data SciMON (Wang et al., 2024a) collected is up to January 2024. RQ = Research Question; BS = Background Survey; I = Inspiration; H = Hypothesis. Qi et al. (2023)’s dataset contains a train set where the publication date of the papers is before January 2023. * in the date column represents the authors have checked the papers should not only be published after the date, but are also not available online before the date (e.g., through arXiv). The five disciplines Kumar et al. (2024) cover are Chemistry, Computer Science, Economics, Medical, and Physics.

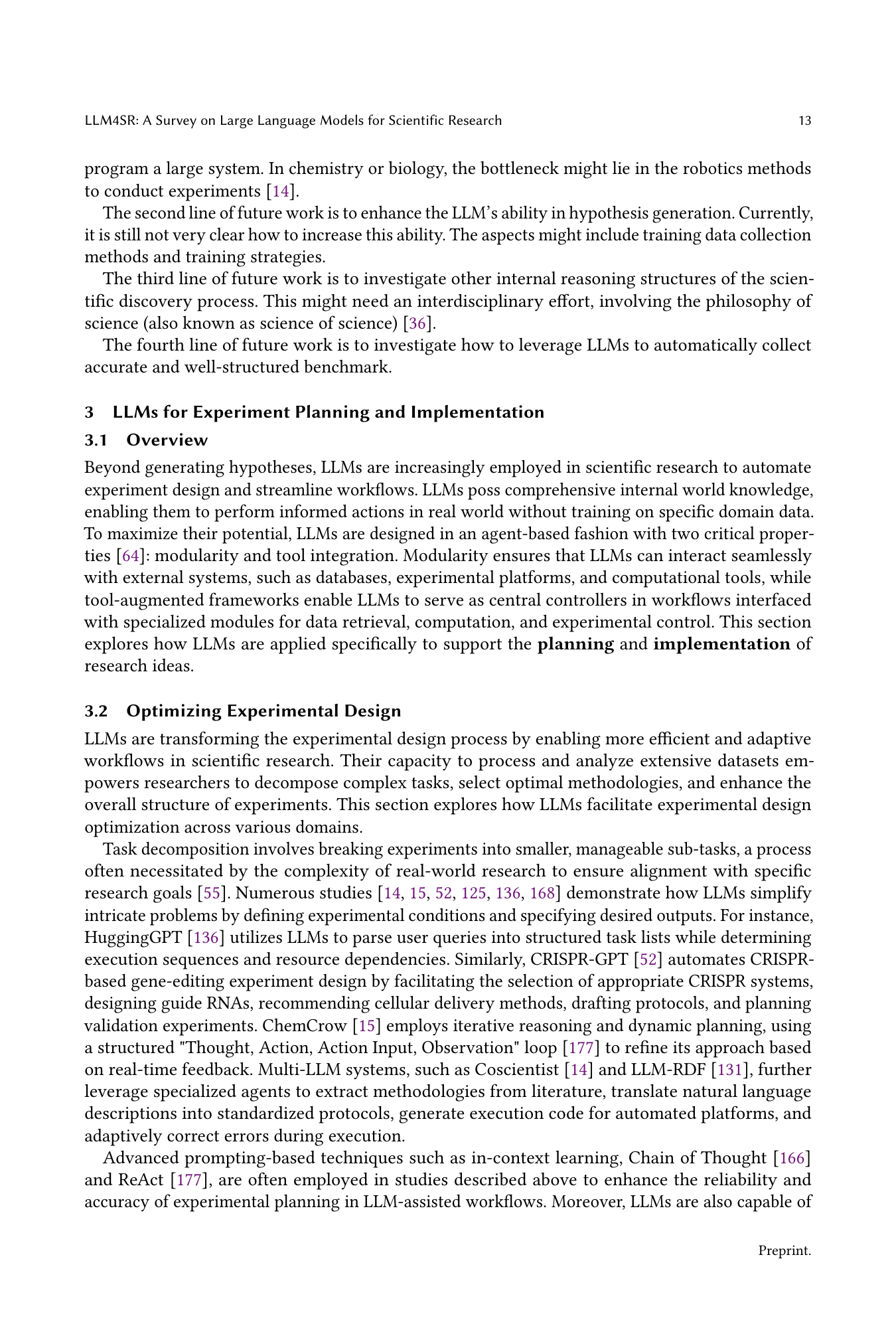

| Benchmark Name | ED | DP | EW | DA | Discipline | Additional Task Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaskBench (Shen et al., 2023b) | ✓ | - | - | - | General | Task decomposition, tool use |

| DiscoveryWorld (Jansen et al., 2024) | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | General | Hypothesis generation, design & testing |

| MLAgentBench (Huang et al., 2024c) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | Machine Learning | Task decomposition, plan selection, optimization |

| AgentBench (Liu et al., 2024b) | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | General | Workflow automation, adaptive execution |

| Spider2-V (Cao et al., 2024) | - | - | ✓ | - | Data Science & Engineering | Multi-step processes, code & GUI interaction |

| DSBench (Jing et al., 2024) | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | Data Science | Data manipulation, data modeling |

| DS-1000 (Lai et al., 2023) | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | Data Science | Code generation for data cleaning & analysis |

| CORE-Bench (Siegel et al., 2024) | - | - | - | ✓ | Computer Science, Social Science & Medicine | Reproducibility testing, setup verification |

| SUPER (Bogin et al., 2024) | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | General | Experiment setup, dependency management |

| MLE-Bench (Chan et al., 2024b) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Machine Learning | End-to-end ML pipeline, training & tuning |

| LAB-Bench (Laurent et al., 2024) | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | Biology | Manipulation of DNA and protein sequences |

| ScienceAgentBench (Chen et al., 2024a) | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Data Science | Data visualization, model development |

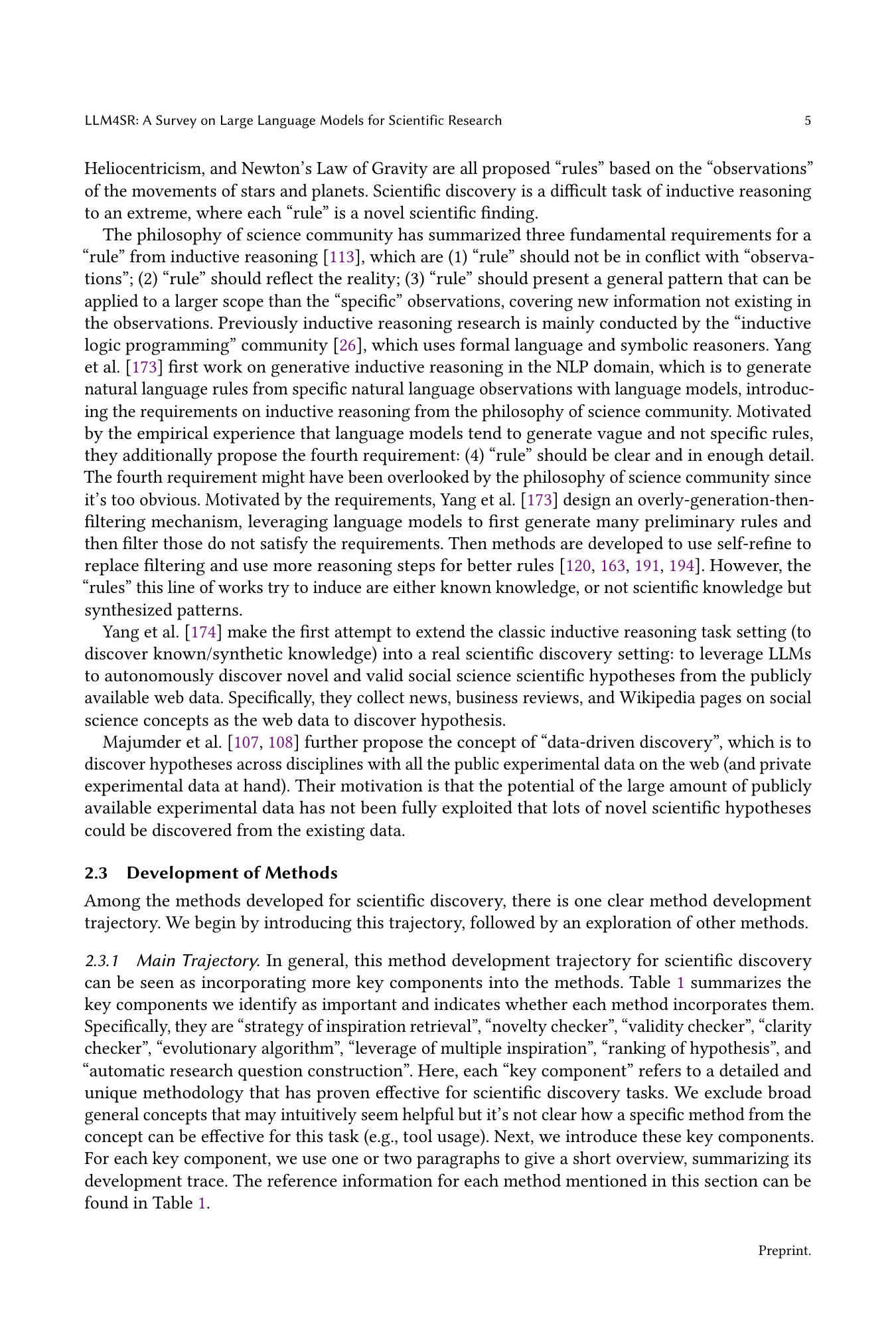

🔼 This table presents benchmarks evaluating Large Language Model (LLM) assistance in the experiment planning and implementation phase of scientific research. It details the benchmarks’ focus on various aspects such as optimizing experimental design (ED), data preparation (DP), automating experiment execution and workflows (EW), and data analysis and interpretation (DA). The ‘discipline’ column indicates whether the benchmark is general-purpose or targeted toward a specific scientific field. For those familiar with this research, it provides a quick overview of the relevant benchmarks and their characteristics. For those less familiar with this research, it serves as a comprehensive summary of the capabilities of LLMs in aiding experimental procedures and data handling.

read the caption

Table 3. Benchmark for LLM-Assisted Experiment Planning and Implementation. ED = Optimizing Experimental Design, DP = Data Preparation, EW = Experiment Execution & Workflow Automation, DA = Data Analysis & Interpretation. “General” in discipline means a benchmark is not designed for a particular discipline.

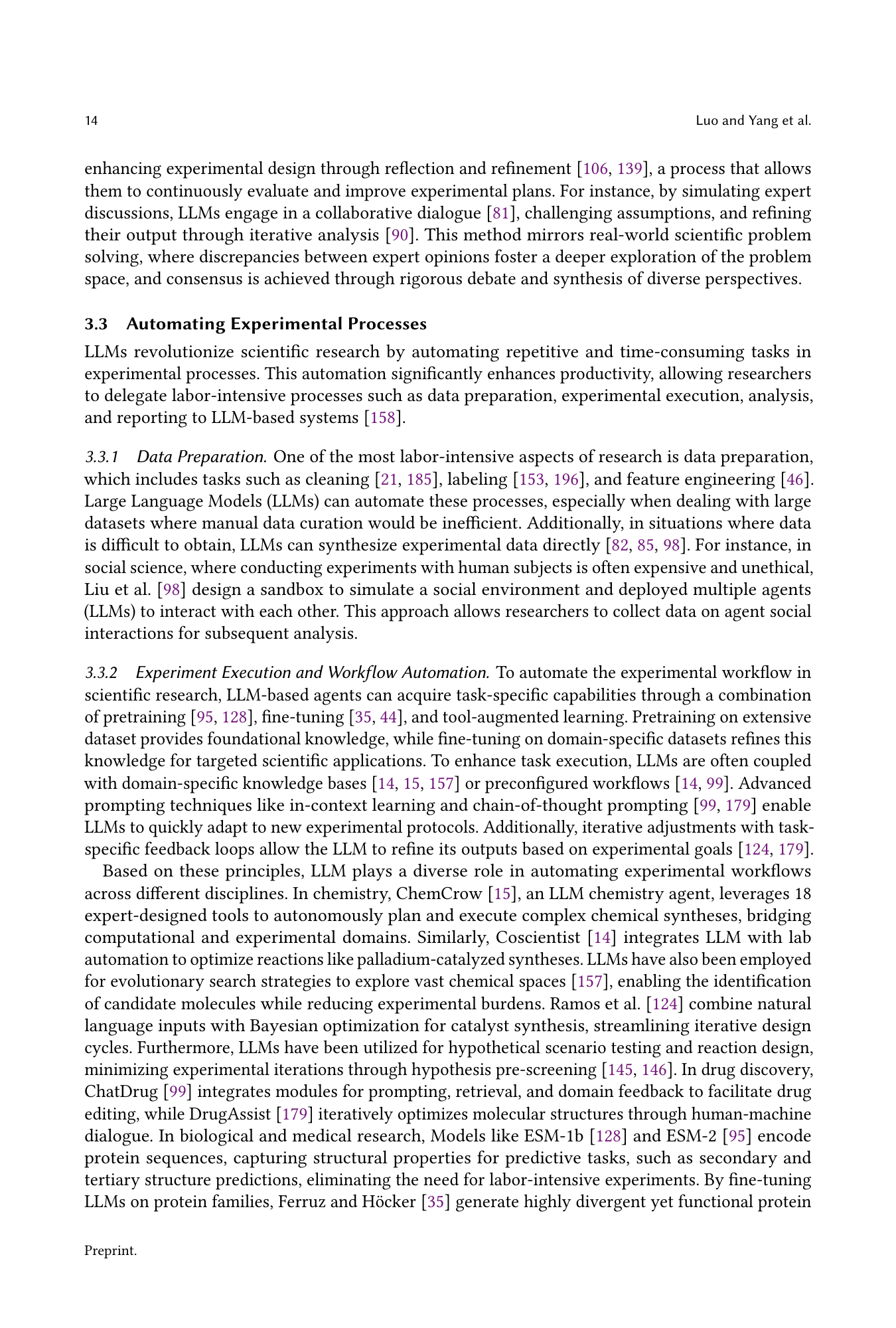

| Task | Benchmark | Dataset | Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citation Text Generation | ALEC (Gao et al., 2023) | ASQA (Stelmakh et al., 2022), QAMPARI (Amouyal et al., 2022), ELI5 (Fan et al., 2019) | Fluency: MAUVE (Pillutla et al., 2021), Correctness: precision, recall. Citation quality: citation recall, citation precision (Gao et al., 2023) |

| CiteBench (Funkquist et al., 2023) | AbuRa’ed et al. (2020), Chen et al. (2021a), Lu et al. (2020), Xing et al. (2020) | Quantitative: ROUGE (Lin, 2004), BertScore (Zhang et al., 2020), Qualitative: citation intent labeling (Cohan et al., 2019), CORWA tagging (Li et al., 2022) | |

| Related Work Generation | None | AAN (Radev et al., 2013), SciSummNet (Yasunaga et al., 2019), Delve (Akujuobi and Zhang, 2017), S2ORC (Lo et al., 2020), CORWA (Li et al., 2022) | ROUGE (Lin, 2004), BLEU (Papineni et al., 2002), Human evaluation: fluency, readability, coherence, relevance, informativeness |

| Drafting and Writing | SciGen (Moosavi et al., 2021) | SciGen (Moosavi et al., 2021) | BLEU (Papineni et al., 2002), METEOR (Banerjee and Lavie, 2005), MoverScore (Zhao et al., 2019), BertScore (Zhang et al., 2020), BLEURT (Sellam et al., 2020), Human evaluation: recall, precision, correctness, hallucination |

| SciXGen (Chen et al., 2021b) | SciXGen (Chen et al., 2021b) | BLEU (Papineni et al., 2002), METEOR (Banerjee and Lavie, 2005), MoverScore (Zhao et al., 2019), Human evaluation: fluency, faithfulness, entailment and overall |

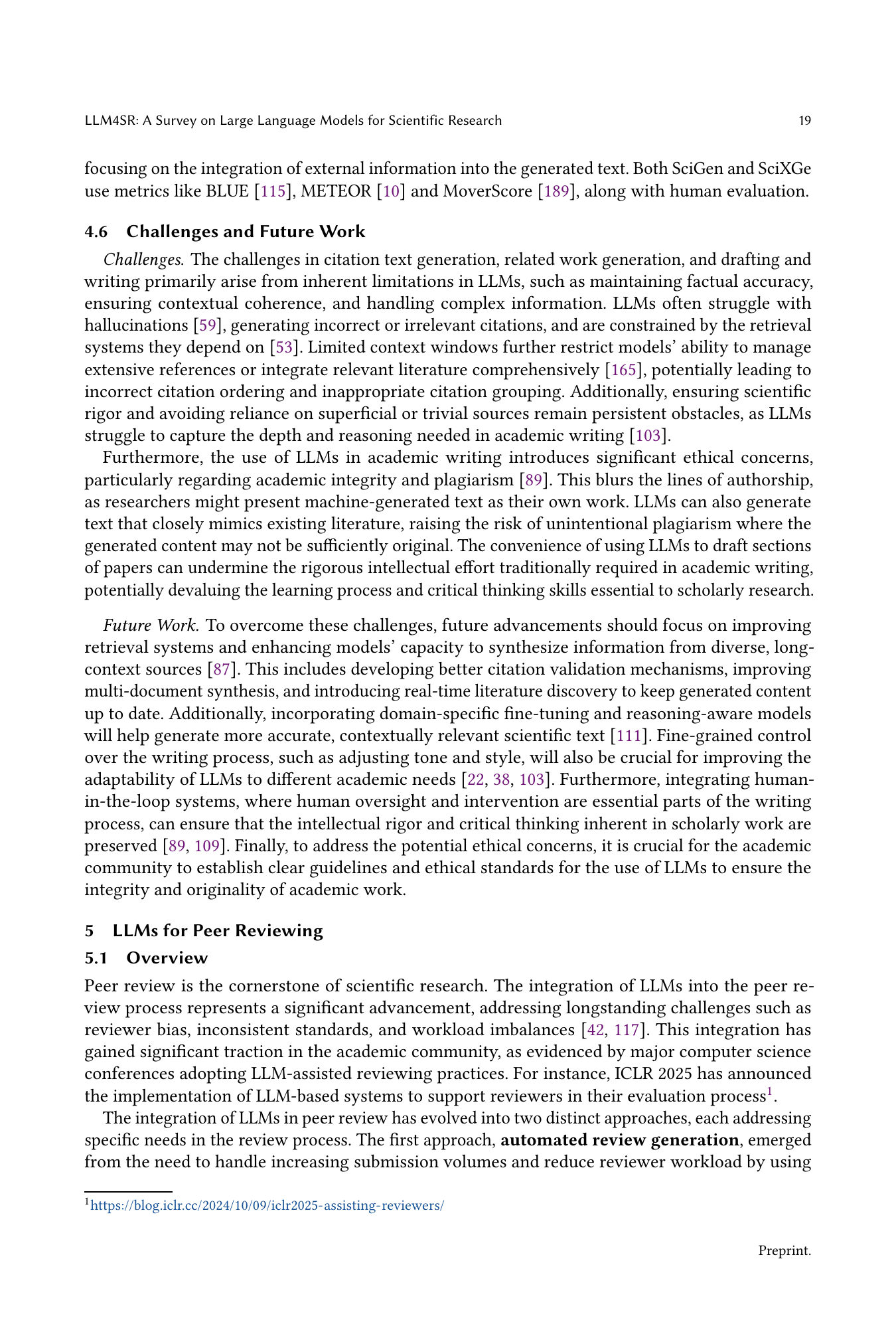

🔼 Table 4 presents evaluation methods used in automated scientific paper writing. It focuses on three key subtasks: citation text generation, related work generation, and drafting & writing. The table details the specific datasets, evaluation metrics (both quantitative and qualitative), and benchmarks used for each subtask to assess the quality and effectiveness of automated writing systems. Notably, it highlights the absence of a universally accepted benchmark for evaluating related work generation.

read the caption

Table 4. Evaluation Methods for automated paper writing, which includes three subtasks: citation text generation, related work generation, and drafting and writing. For the related work generation, there is no universally recognized benchmark.

| Dataset Name | PR | MR | Additional Task | S | C | D | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOPRD (Lin et al., 2023b) | ✓ | ✓ | Editorial decision prediction, Scientometric analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| NLPEER (Dycke et al., 2023) | ✓ | ✓ | Score prediction, Guided skimming, Pragmatic labeling | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| MReD (Shen et al., 2022) | - | ✓ | Structured text summarization | ✓ | - | - | ✓ |

| PEERSUM (Li et al., 2023a) | - | ✓ | Opinion synthesis | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| ORSUM (Zeng et al., 2024) | - | ✓ | Opinion summarization, Factual consistency analysis | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| ASAP-Review (Yuan et al., 2022) | ✓ | - | Aspect-level analysis, Acceptance prediction | ✓ | - | - | - |

| REVIEWER2 (Gao et al., 2024) | ✓ | - | Coverage & specificity enhancement | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| PeerRead (Kang et al., 2018) | ✓ | - | Acceptance prediction, Score prediction | ✓ | - | - | - |

| ReviewCritique (Du et al., 2024) | ✓ | - | Deficiency identification | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

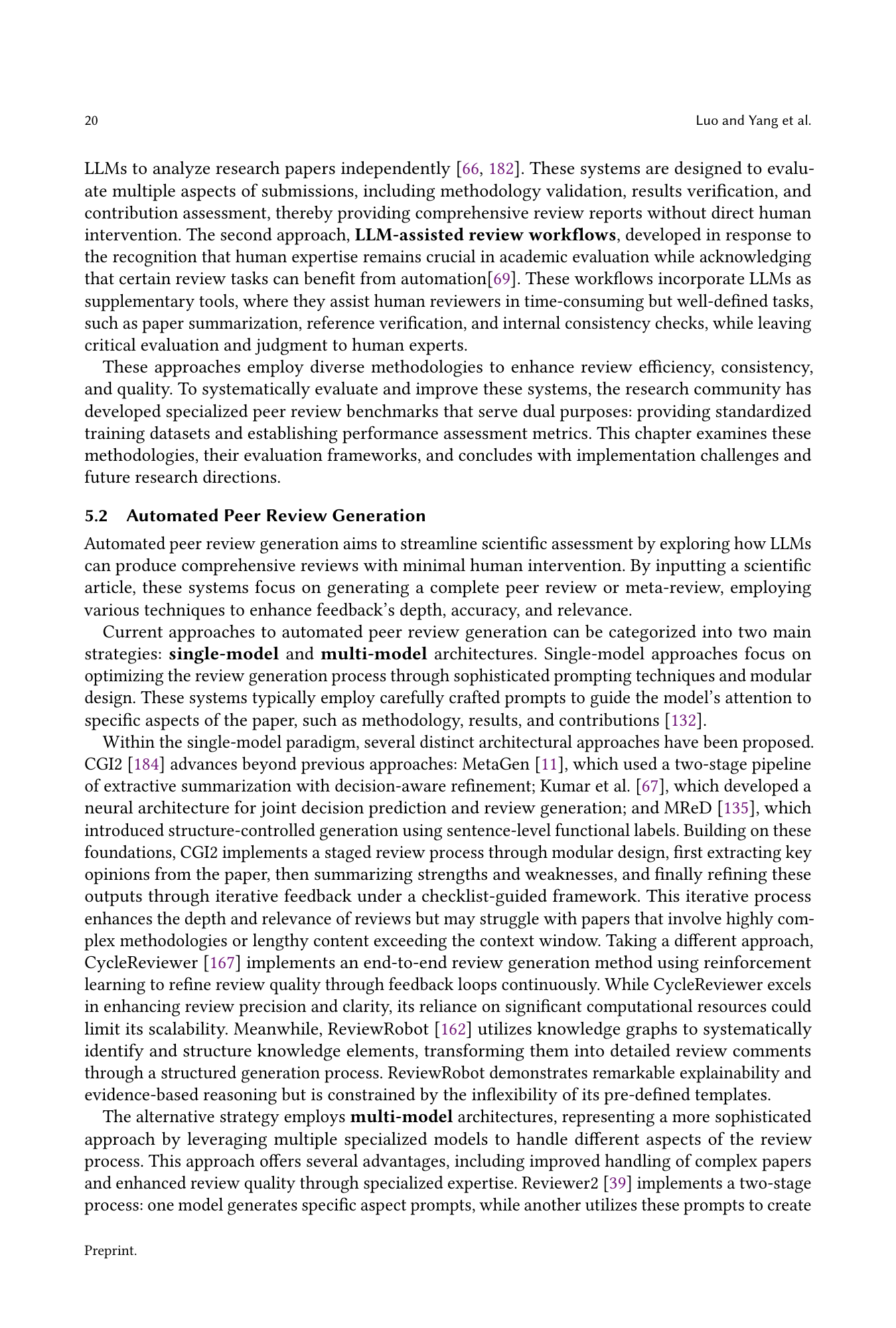

🔼 Table 5 presents a summary of peer review datasets and their evaluation metrics. It lists several datasets used to benchmark and evaluate the effectiveness of Large Language Models (LLMs) in automated peer review and LLM-assisted workflows. For each dataset, it shows whether the dataset evaluates peer reviews (PR), meta-reviews (MR), or both. The table further details which evaluation metrics are used for each dataset. These metrics include: Semantic Similarity (S), measuring how similar the LLM-generated reviews are to human-written reviews; Coherence and Relevance (C), assessing the logical flow and relevance of the reviews; Diversity and Specificity (D), evaluating the range and depth of feedback in the reviews; and Human Evaluation (H), representing human judgments of review quality. The table thus provides a comprehensive overview of the resources and methods used for evaluating the performance of LLM-based peer review systems.

read the caption

Table 5. Peer Review Datasets and Evaluation Metrics. The Evaluation Metrics columns use the following abbreviations: PR (Peer Review), MR (Meta-review), S (Semantic Similarity), C (Coherence & Relevance), D (Diversity & Specificity), and H (Human Evaluation). Columns S, C, D, and H represent the evaluation metrics used in the study.

Full paper#