↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Multimodal mathematical reasoning by large language models (LLMs) is challenging due to the scarcity of high-quality Chain-of-Thought (CoT) training data. Existing models struggle with high-precision CoT reasoning and limited potential during test time. This hinders real-world applications.

This paper introduces URSA, a three-module framework integrating CoT distillation, trajectory rewriting, and format unification. URSA generates a new dataset, MMathCoT-1M, and trains a robust model, URSA-7B, achieving state-of-the-art results. A data synthesis strategy, DualMath-1.1M, and a verifier model, URSA-RM-7B, further boost test-time scaling and out-of-distribution generalization capabilities. The open-sourced model and data are valuable resources for future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical need for high-quality training data in multimodal mathematical reasoning. It introduces a novel data synthesis strategy and a robust model (URSA-7B) that significantly advances the state-of-the-art, opening new avenues for research in test-time scaling and out-of-distribution generalization. The open-sourcing of the model and data further accelerates progress in the field.

Visual Insights#

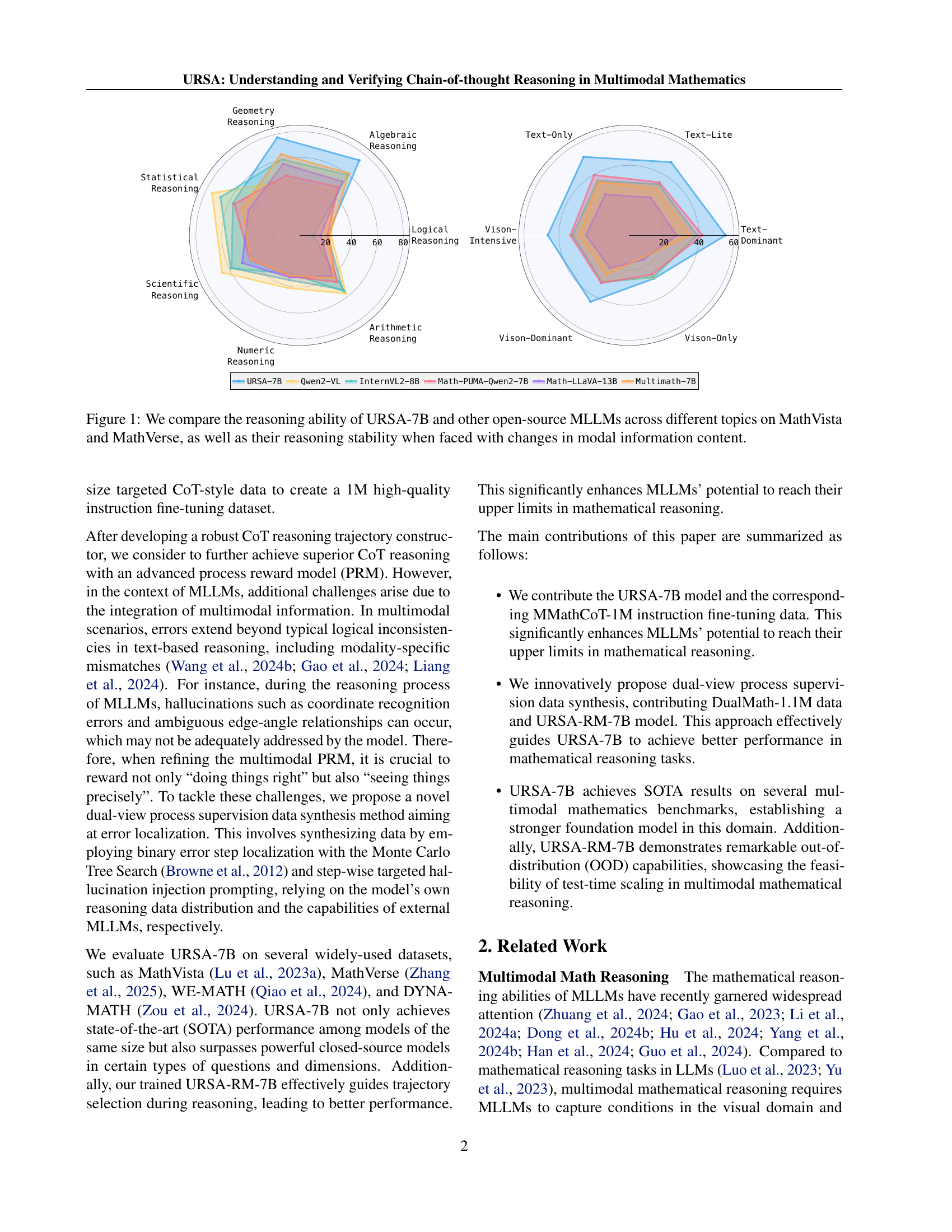

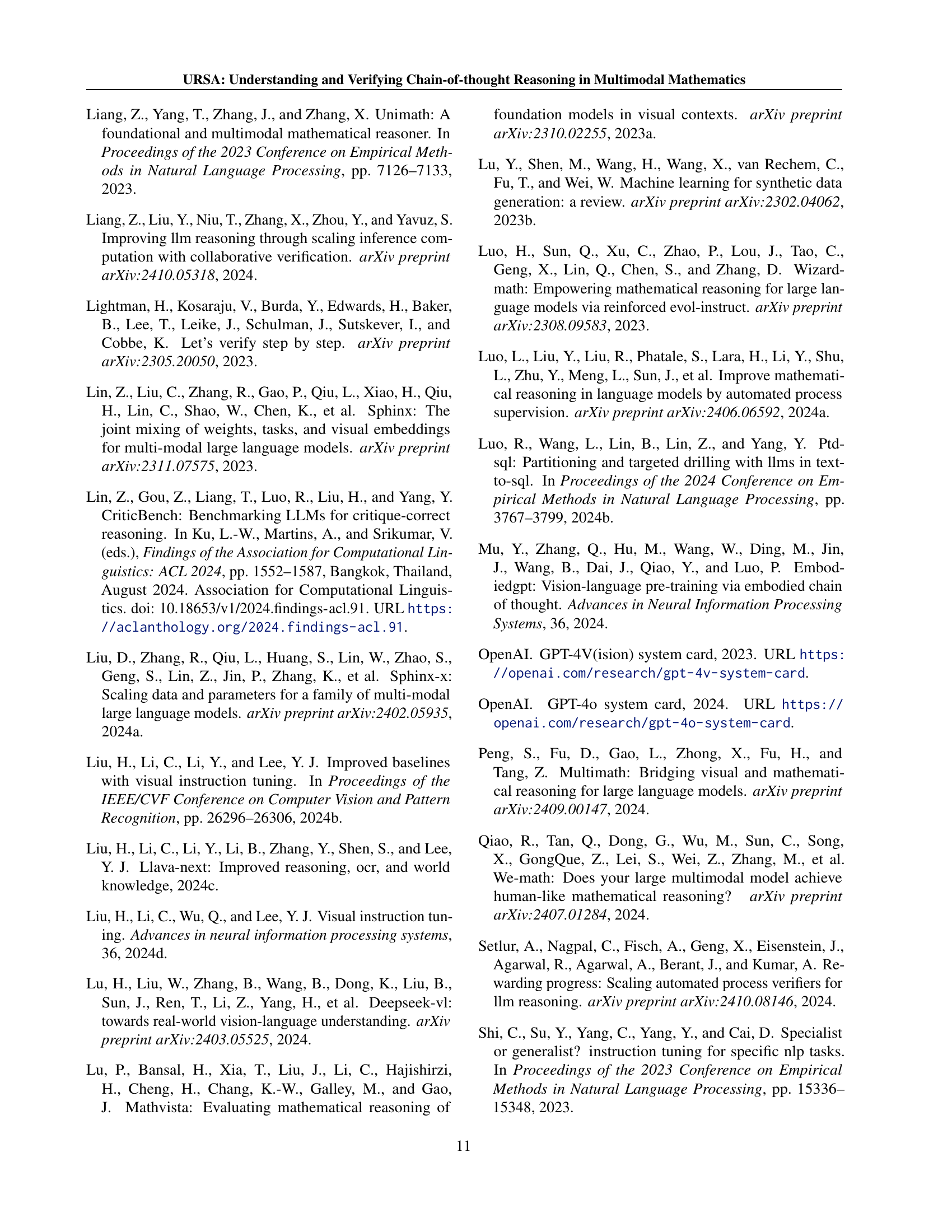

🔼 This figure presents a radar chart comparing the performance of the URSA-7B model against several other open-source large language models (LLMs) on two benchmark datasets: MathVista and MathVerse. Each axis represents a different category of mathematical reasoning problems (e.g., statistical reasoning, geometry reasoning). The lengths of the vectors emanating from the center of the chart represent the accuracy of each model on the corresponding task. The chart also shows how the models perform when the type of input data (text-only, text-lite, etc.) is varied to assess their robustness when the type and amount of modal information change. The overall goal of the figure is to demonstrate the superior reasoning ability and stability of the URSA-7B model across various mathematical problems and different data conditions.

read the caption

Figure 1: We compare the reasoning ability of URSA-7B and other open-source MLLMs across different topics on MathVista and MathVerse, as well as their reasoning stability when faced with changes in modal information content.

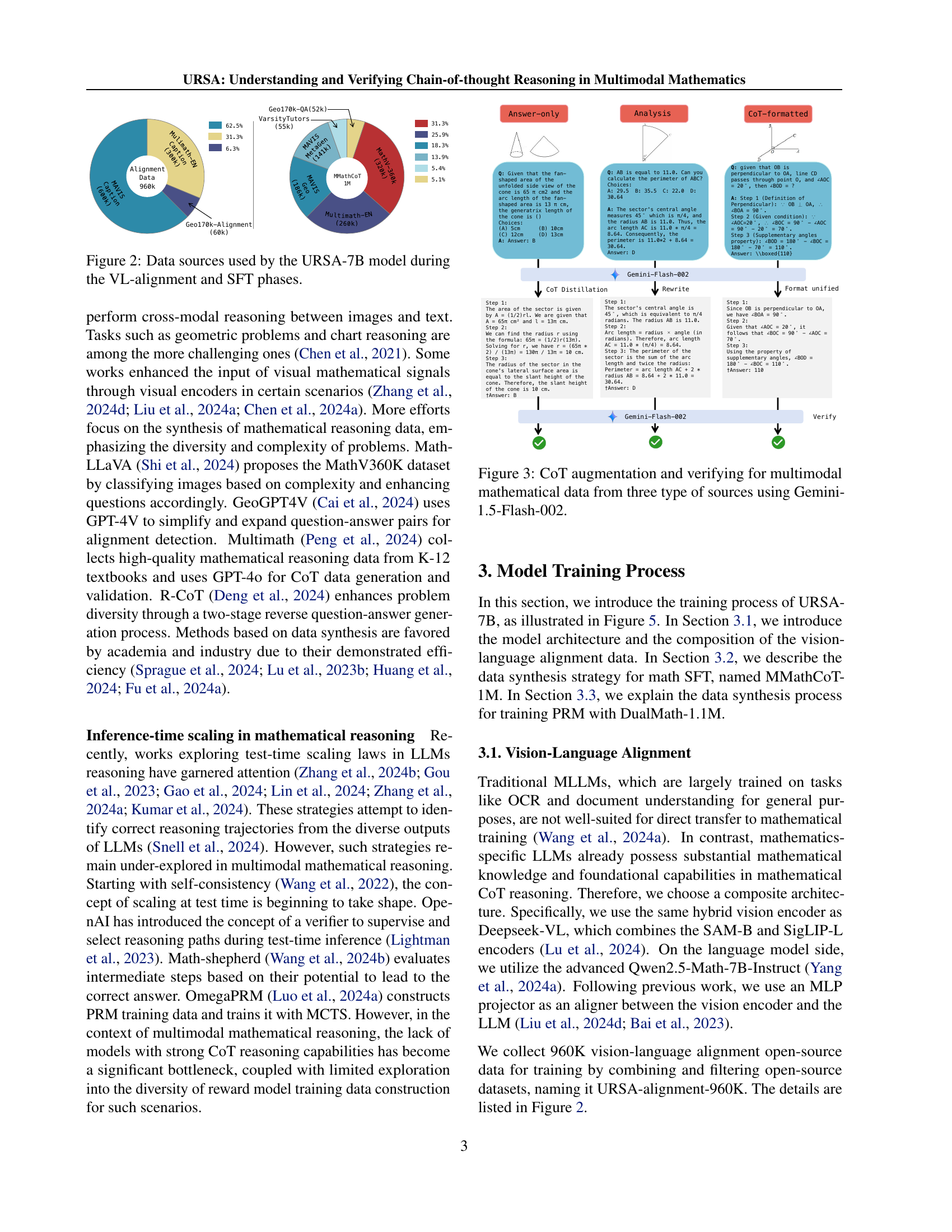

| Model | #Params | MathVista ALL | MathVista GPS | MathVista MWP | MathVista FQA | MathVista TQA | MathVista VQA | MathVerse ALL | MathVerse TD | MathVerse TL | MathVerse TO | MathVerse VI | MathVerse VD | MathVerse VO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselines | ||||||||||||||

| Random | - | 17.9 | 21.6 | 3.8 | 18.2 | 19.6 | 26.3 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 |

| Human | - | 60.3 | 48.4 | 73.0 | 59.7 | 63.2 | 55.9 | 64.9 | 71.2 | 70.9 | 41.7 | 61.4 | 68.3 | 66.7 |

| Closed-Source MLLMs | ||||||||||||||

| GPT-4o [2024] | - | 63.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| GPT-4V [2023] | - | 49.9 | 50.5 | 57.5 | 43.1 | 65.2 | 38.0 | 54.4 | 63.1 | 56.6 | 60.3 | 51.4 | 32.8 | 50.3 |

| Gemini-1.5-002-Flash [2023] | - | 58.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro [2023] | - | 63.9 | - | - | - | - | - | 35.3 | 39.8 | 34.7 | 44.5 | 32.0 | 36.8 | 33.3 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet [2024] | - | 67.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Qwen-VL-Plus [2023] | - | 43.3 | 35.5 | 31.2 | 54.6 | 48.1 | 51.4 | 21.3 | 26.0 | 21.2 | 25.2 | 18.5 | 19.1 | 21.8 |

| Open-Source General MLLMs | ||||||||||||||

| mPLUG-Owl2-7B [2023] | 7B | 22.2 | 23.6 | 10.2 | 22.7 | 27.2 | 27.9 | 10.3 | 11.6 | 11.4 | 13.8 | 11.1 | 9.4 | 8.0 |

| MiniGPT4-7B [2023] | 7B | 23.1 | 26.0 | 13.4 | 18.6 | 30.4 | 30.2 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 12.5 | 14.8 | 8.7 |

| LLaVA-1.5-13B [2024b] | 13B | 27.7 | 22.7 | 18.9 | 23.8 | 43.0 | 30.2 | 12.7 | 17.1 | 12.0 | 22.6 | 12.6 | 12.7 | 9.0 |

| SPHINX-V2-13B [2023] | 13B | 36.7 | 16.4 | 23.1 | 54.6 | 41.8 | 43.0 | 16.1 | 20.8 | 14.1 | 14.0 | 16.4 | 15.6 | 16.2 |

| LLaVA-NeXT-34B [2024c] | 34B | 46.5 | - | - | - | - | - | 34.6 | 49.0 | 37.6 | 30.1 | 35.2 | 28.9 | 22.4 |

| InternLM-XComposer2-VL [2024a] | 7B | 57.6 | 63.0 | 73.7 | 55.0 | 56.3 | 39.7 | 25.9 | 36.9 | 28.3 | 42.5 | 20.1 | 24.4 | 19.8 |

| Deepseek-VL [2024] | 7B | 34.9 | 28.4 | 55.9 | 26.8 | 32.9 | 34.6 | 19.3 | 23.0 | 23.2 | 23.1 | 20.2 | 18.4 | 11.8 |

| InternVL2-8B [2024b] | 8B | 58.3 | 62.0 | 59.1 | 58.7 | 61.4 | 49.7 | 35.9 | 39.0 | 33.8 | 36.0 | 32.2 | 30.9 | 27.7 |

| Qwen2-VL [2024a] | 7B | 58.9 | 40.9 | 64.0 | 69.1 | 60.1 | 58.1 | 33.6 | 37.4 | 33.5 | 35.0 | 31.3 | 30.3 | 28.1 |

| Open-Source Math MLLMs | ||||||||||||||

| G-LLaVA-7B [2023] | 7B | 25.1 | 48.7 | 3.6 | 19.1 | 25.0 | 28.7 | 16.6 | 20.9 | 20.7 | 21.1 | 17.2 | 14.6 | 9.4 |

| Math-LLaVA-13B [2024] | 13B | 46.6 | 57.7 | 56.5 | 37.2 | 51.3 | 33.5 | 22.9 | 27.3 | 24.9 | 27.0 | 24.5 | 21.7 | 16.1 |

| Math-PUMA-Qwen2-7B [2024] | 7B | 47.9 | 48.1 | 68.3 | 46.5 | 46.2 | 30.2 | 33.6 | 42.1 | 35.0 | 39.8 | 33.4 | 31.6 | 26.0 |

| Math-PUMA-DeepSeek-Math [2024] | 7B | 44.7 | 39.9 | 67.7 | 42.8 | 42.4 | 31.3 | 31.8 | 43.4 | 35.4 | 47.5 | 33.6 | 31.6 | 14.7 |

| MAVIS-7B [2024d] | 7B | - | 64.1 | - | - | - | - | 35.2 | 43.2 | 37.2 | - | 34.1 | 29.7 | 31.8 |

| InfiMM-Math [2024] | 7B | - | - | - | - | - | - | 34.5 | 46.7 | 32.4 | - | 38.1 | 32.4 | 15.8 |

| MultiMath-7B [2024] | 7B | 50.0 | 66.8 | 61.8 | 40.1 | 50.0 | 33.0 | 27.7 | 34.8 | 30.8 | 35.3 | 28.1 | 25.9 | 15.0 |

| URSA-7B | 7B | 59.8 | 79.3 | 75.3 | 44.6 | 63.9 | 40.2 | 45.7 | 55.3 | 48.3 | 51.8 | 46.4 | 43.9 | 28.6 |

| Δ over SOTA Open-Source Math MLLMs | - | +9.8 | +12.5 | +7.0 | -1.9 | +12.6 | +6.7 | +10.5 | +8.6 | +11.1 | +4.3 | +8.3 | +11.5 | -3.2 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on two mathematical reasoning benchmarks: MATHVISTA and MATHVERSE. The models are categorized into closed-source and open-source, with open-source models further divided into general-purpose and those specifically designed for mathematical reasoning. Performance is measured across several sub-tasks within each benchmark and is indicated by numerical scores. The table highlights the best-performing model for each task in bold, and the second-best is underlined. To help distinguish performance levels, the best closed-source model results are shown in green, while the best and second-best open-source model results are shown in red and blue, respectively.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with closed-source MLLMs and open-source MLLMs on MATHVISTA testmini and MATHVERSE testmini. The best is bold, and the runner-up is underline. The best results of Closed-source MLLMs are highlighted in green. The best and second-best results of Open-source MLLMs are highlighted in red and blue respectively.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal CoT#

Multimodal Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning extends the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) by integrating visual information with textual reasoning. This multimodal approach presents unique challenges, such as handling modality-specific mismatches (e.g., discrepancies between visual and textual data) and generating high-quality training data. A key benefit of multimodal CoT is the ability to tackle complex problems requiring both visual interpretation and logical deduction, which are beyond the scope of unimodal LLMs. However, effective multimodal CoT relies on robust data synthesis strategies for both training and testing, due to the scarcity of real-world multimodal CoT data. Furthermore, robust evaluation metrics are needed to assess the true capabilities of multimodal CoT systems, as traditional metrics may not capture the nuances of this approach. Future research in this area should focus on developing innovative data synthesis techniques and refined evaluation methods to fully realize the potential of multimodal CoT in various fields.

URSA-7B Model#

The URSA-7B model, as described in the research paper, represents a significant advancement in multimodal mathematical reasoning. Its core strength lies in its ability to perform chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning, a crucial step toward solving complex problems by breaking them down into smaller, manageable steps. The model’s effectiveness is significantly boosted by the MMathCoT-1M dataset, a meticulously curated instruction fine-tuning dataset specifically designed for multimodal mathematics. This dataset plays a vital role in enabling URSA-7B to achieve state-of-the-art performance across various benchmarks. Furthermore, the innovative dual-view process supervision, using DualMath-1.1M, elevates URSA-7B’s reasoning capabilities by addressing both logical and visual accuracy, leading to superior performance and robustness, particularly in scenarios with complex visual inputs. The integration of URSA-RM-7B as a verifier further enhances the model’s capabilities for test-time scaling, showcasing a comprehensive approach to addressing challenges within multimodal mathematical reasoning.

DualMath-1.1M#

The proposed DualMath-1.1M dataset is a crucial contribution to advancing multimodal mathematical reasoning. Its focus on dual-view process supervision—incorporating both logical correctness and visual accuracy—addresses limitations in existing datasets which primarily focus on logical accuracy alone. By synthesizing data with targeted hallucination injection and binary error localization, DualMath-1.1M offers a sophisticated training resource that enables models to not only produce correct answers, but also robust and reliable reasoning steps. This dual-view approach directly addresses the complexity introduced by multimodal data, which may contain inconsistencies between textual and visual information. The dataset’s impact extends beyond immediate performance gains; it pushes the boundary of test-time scaling methods by offering a rigorous means to evaluate and enhance reasoning processes. The success of DualMath-1.1M in training a verifier model (URSA-RM-7B) showcases its potential in improving the efficiency and reliability of future multimodal mathematical reasoning systems.

Test-Time Scaling#

Test-time scaling in large language models (LLMs) focuses on improving reasoning performance without retraining the model. This is crucial for deploying LLMs in resource-constrained settings or when rapid adaptation is needed. The paper explores this by introducing a data synthesis strategy that generates process annotation datasets. This approach moves beyond simply producing correct answers, emphasizing the generation of high-quality reasoning trajectories. By training a separate verifier model, the system enhances the selection of correct reasoning paths at inference time, leading to improved accuracy and robustness. This dual-pronged approach, combining data augmentation and model verification, represents a significant step forward in efficient LLM deployment and demonstrates the potential for achieving substantial performance gains without the need for additional training data or increased model size.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on multimodal mathematical reasoning could explore several promising avenues. Extending the model’s capabilities to handle even more complex mathematical problems and diverse problem types is crucial. Investigating improved data synthesis techniques that generate more sophisticated and nuanced reasoning trajectories is key for improving model accuracy. This includes exploring methods to better capture the subtleties of visual information within the context of mathematical problems. Additionally, developing more robust and effective verification methods is essential to ensure accuracy and enhance test-time scaling. The current verification model could be enhanced by incorporating more sophisticated evaluation metrics and potentially incorporating external knowledge bases. Finally, exploring alternative architectures and training methodologies may reveal further performance improvements. This could include exploring the integration of other advanced techniques like reinforcement learning and self-supervised learning to further enhance the model’s capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

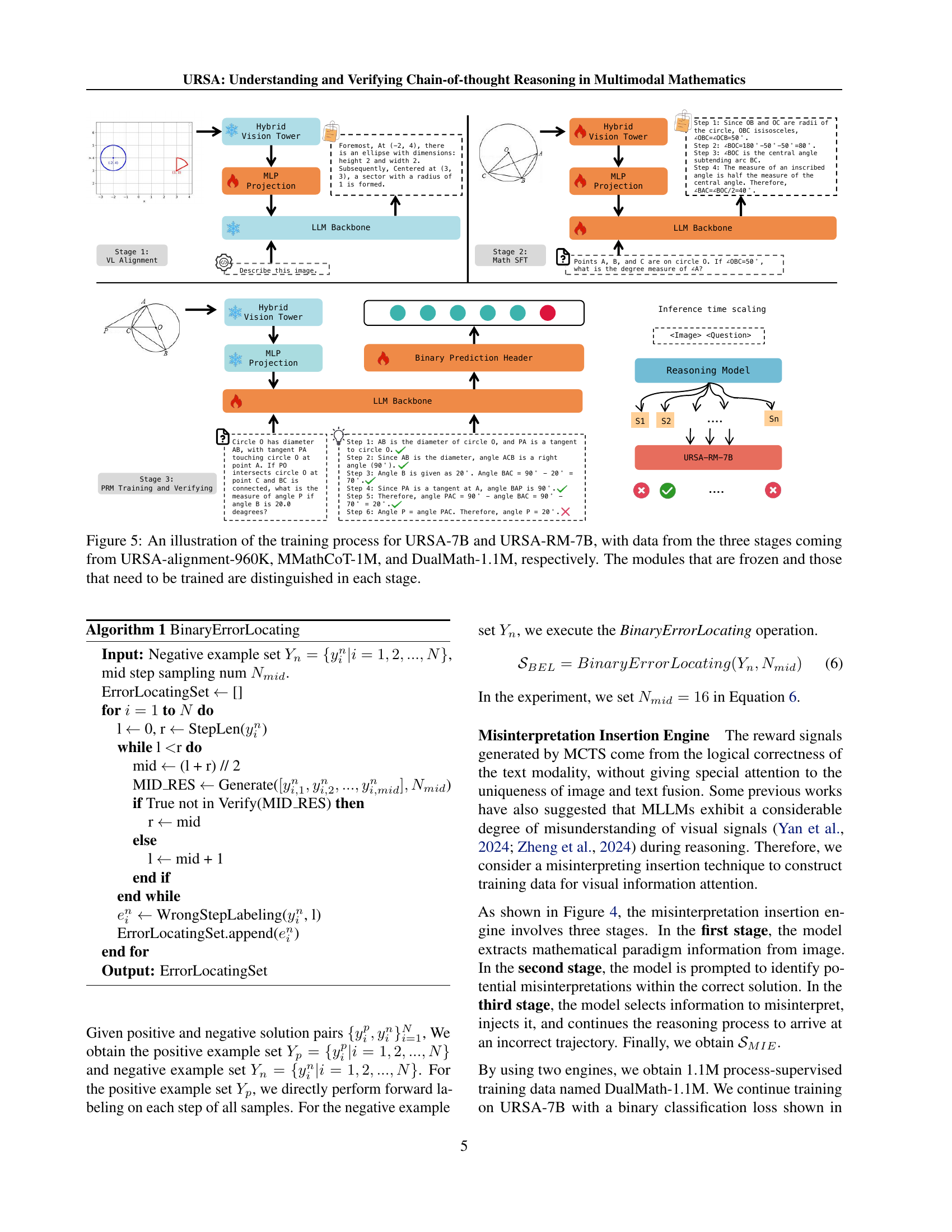

🔼 This figure shows the data sources used to train the URSA-7B model. It breaks down the composition of the URSA-alignment-960K dataset used in the vision-language alignment phase and the MMathCoT-1M dataset used in the subsequent supervised fine-tuning (SFT) phase. The figure visually represents the percentage contribution of each dataset to the overall training data. It highlights the diversity of sources, including datasets focusing on various mathematical problem types and formats (e.g., geometry, word problems, and tables).

read the caption

Figure 2: Data sources used by the URSA-7B model during the VL-alignment and SFT phases.

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of generating high-quality chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning data for multimodal mathematics. It uses Gemini-1.5-Flash-002 to augment existing datasets in three ways: CoT distillation, trajectory rewriting, and format unification. The figure shows examples of how input data from three different sources is transformed using these techniques to create a more consistent and comprehensive CoT dataset for training and validating multimodal mathematical reasoning models. Each step demonstrates how Gemini-1.5-Flash-002 is used to enhance the reasoning process, leading to a unified, improved CoT format suitable for fine-tuning.

read the caption

Figure 3: CoT augmentation and verifying for multimodal mathematical data from three type of sources using Gemini-1.5-Flash-002.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the process of inserting misinterpretations into a reasoning chain. The example shows a chart about public opinion on labor unions, broken down by age, education level, and political leaning. The model initially extracts information correctly, identifying that certain groups have more favorable views toward unions. However, a misinterpretation is then introduced, such as incorrectly interpreting the data for one group. Following the misinterpretation, the model continues to reason and draw incorrect conclusions based on this flawed interpretation. This illustrates how the engine creates training data by highlighting logical errors stemming from visual misinterpretations.

read the caption

Figure 4: Demonstration of Misinterpretation Insertion Engine.

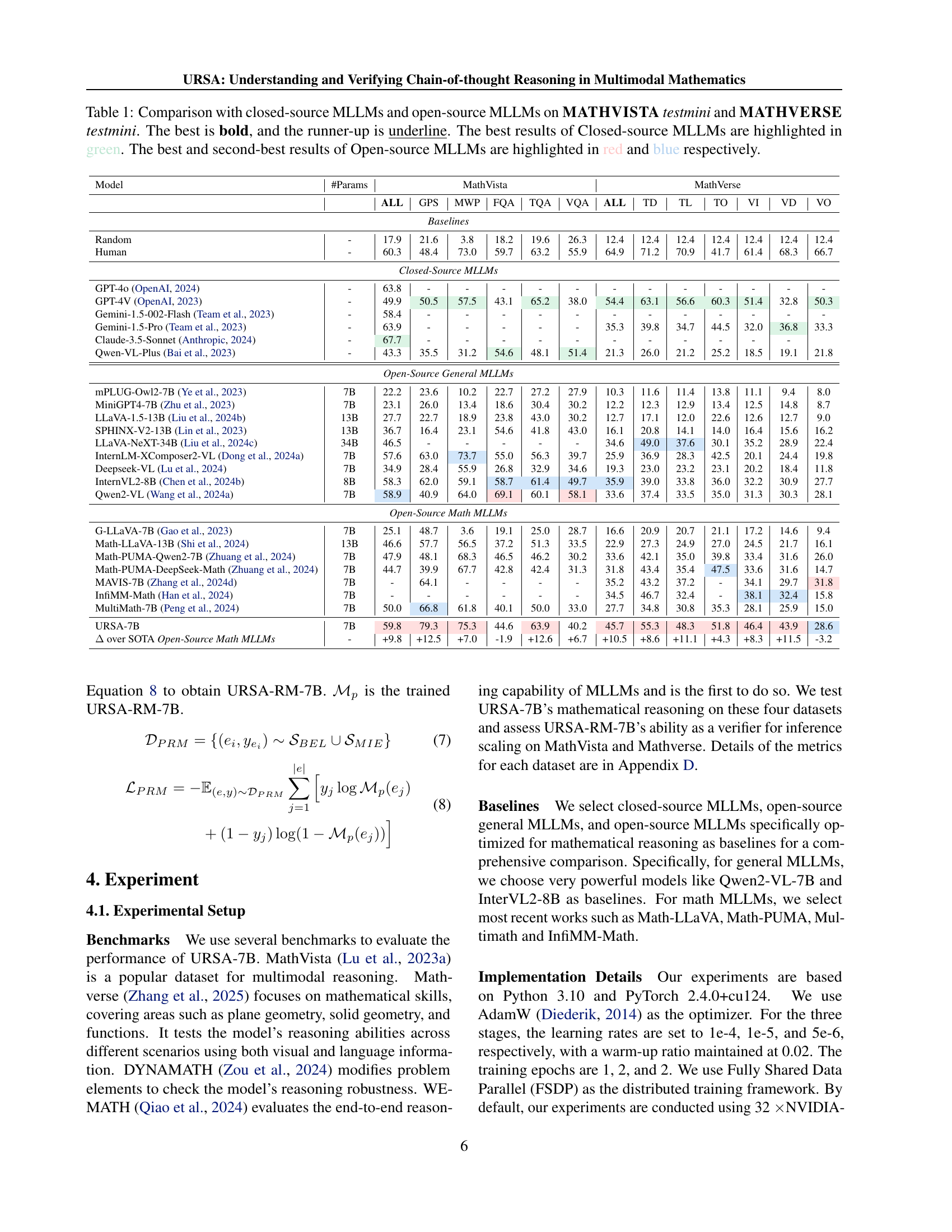

🔼 This figure illustrates the three-stage training process for the URSA-7B and URSA-RM-7B models. Stage 1 involves vision-language alignment using the URSA-alignment-960K dataset, focusing on aligning the vision encoder and language model. Stage 2 performs mathematical instruction fine-tuning on the MMathCoT-1M dataset, enhancing the model’s chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning capabilities. Finally, Stage 3 employs dual-view process supervision using the DualMath-1.1M dataset, training a verifier model (URSA-RM-7B) to enhance the reasoning at test time. The figure clearly shows which model components are frozen and which are trained during each stage.

read the caption

Figure 5: An illustration of the training process for URSA-7B and URSA-RM-7B, with data from the three stages coming from URSA-alignment-960K, MMathCoT-1M, and DualMath-1.1M, respectively. The modules that are frozen and those that need to be trained are distinguished in each stage.

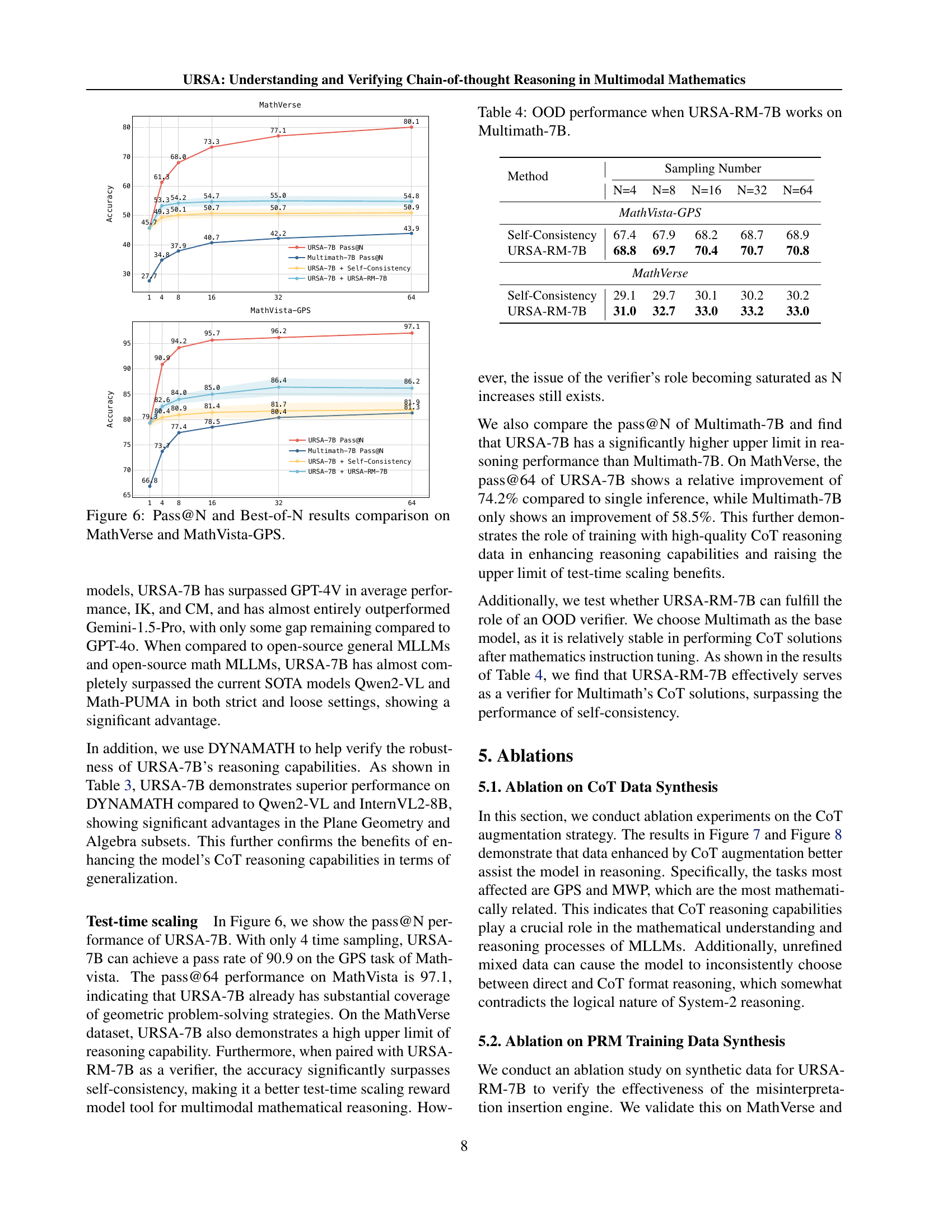

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different methods for improving the accuracy of chain-of-thought reasoning in mathematical problem-solving, specifically focusing on two benchmarks: MathVerse and MathVista-GPS. It shows how the ‘pass@N’ metric (the percentage of times a model correctly answers a question within N attempts) and the ‘best-of-N’ metric (choosing the best answer among N attempts) change with the number of samples (N). The methods compared likely include the baseline model, a self-consistency approach, and the URSA-RM-7B verifier model, which are described in the paper. The results visualize how using multiple samples and the verifier can lead to significant improvements in accuracy compared to relying on a single answer.

read the caption

Figure 6: Pass@N and Best-of-N results comparison on MathVerse and MathVista-GPS.

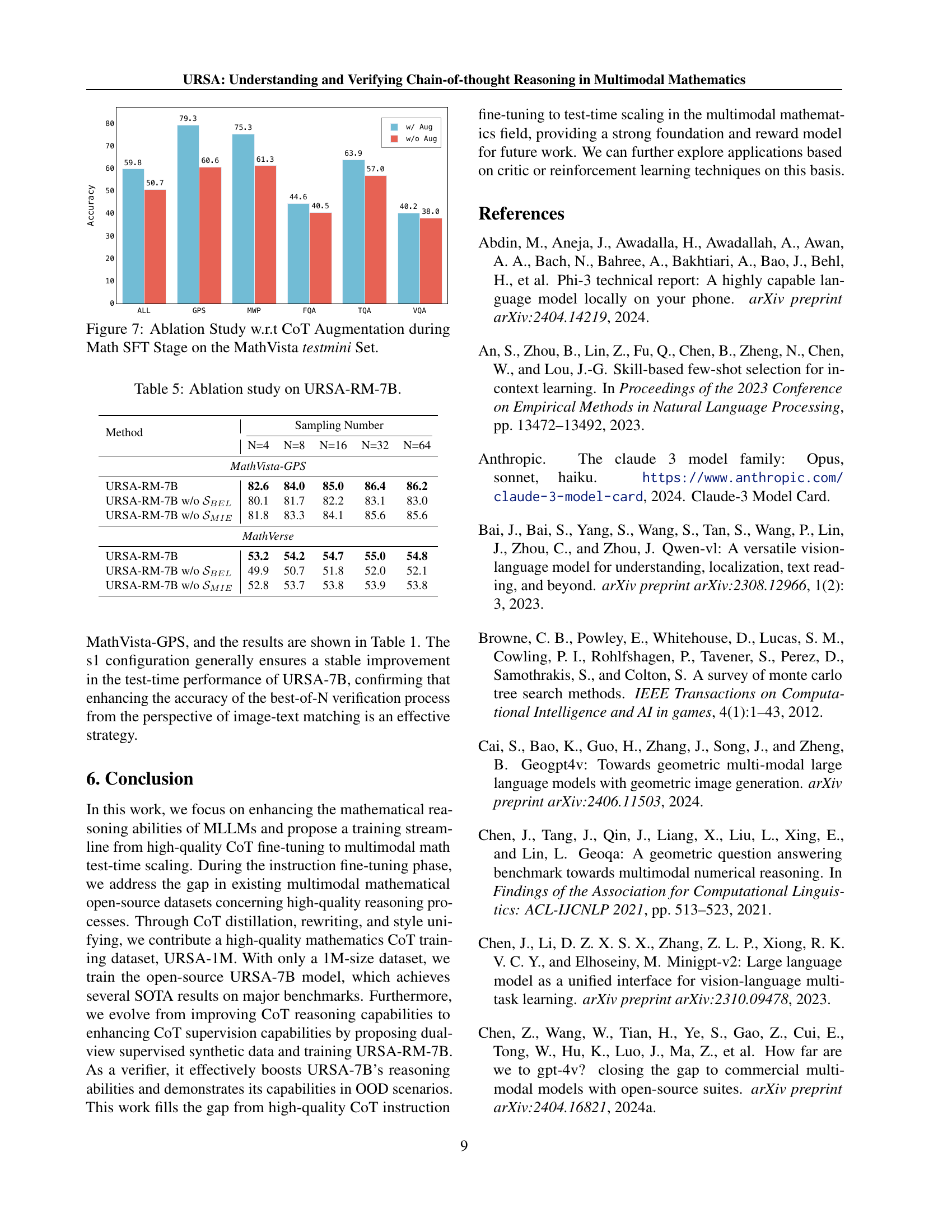

🔼 This figure presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of chain-of-thought (CoT) augmentation during the mathematical instruction fine-tuning (Math SFT) stage on the MathVista testmini dataset. It shows how the performance of the model changes when CoT augmentation is removed, providing a quantitative analysis of the contribution of CoT reasoning to the model’s capabilities on various subtasks within MathVista. This allows for a better understanding of the effectiveness of the CoT augmentation strategy.

read the caption

Figure 7: Ablation Study w.r.t CoT Augmentation during Math SFT Stage on the MathVista testmini Set.

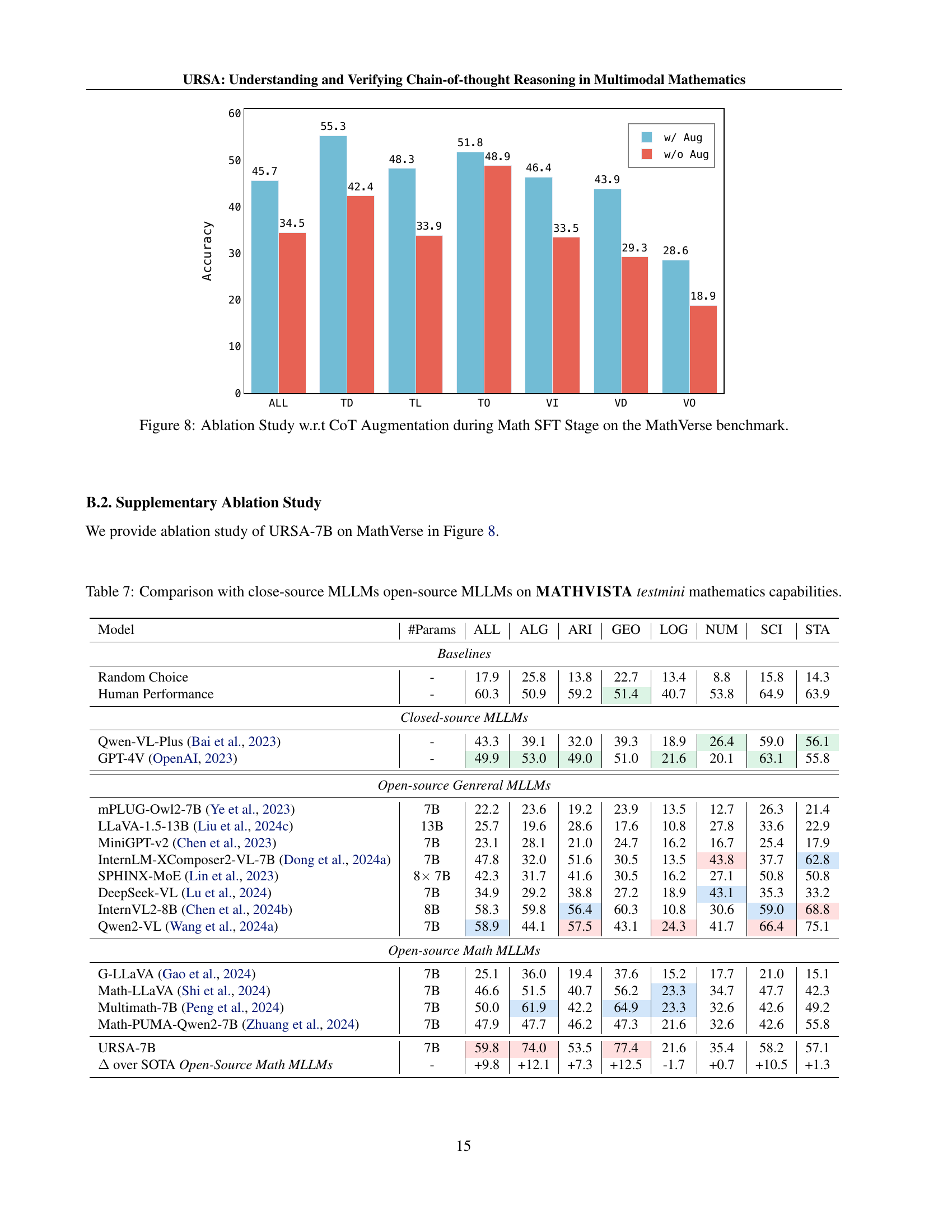

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study with respect to chain-of-thought (CoT) augmentation during the mathematical instruction fine-tuning (Math SFT) stage on the MathVerse benchmark. It visually compares the performance of the model with and without CoT augmentation across various sub-tasks within the MathVerse benchmark. The graph likely shows accuracy or a similar performance metric on the y-axis, and different sub-tasks or aspects of the MathVerse benchmark on the x-axis. This allows readers to see how much the addition of CoT augmentation improves the model’s performance on each MathVerse sub-task.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation Study w.r.t CoT Augmentation during Math SFT Stage on the MathVerse benchmark.

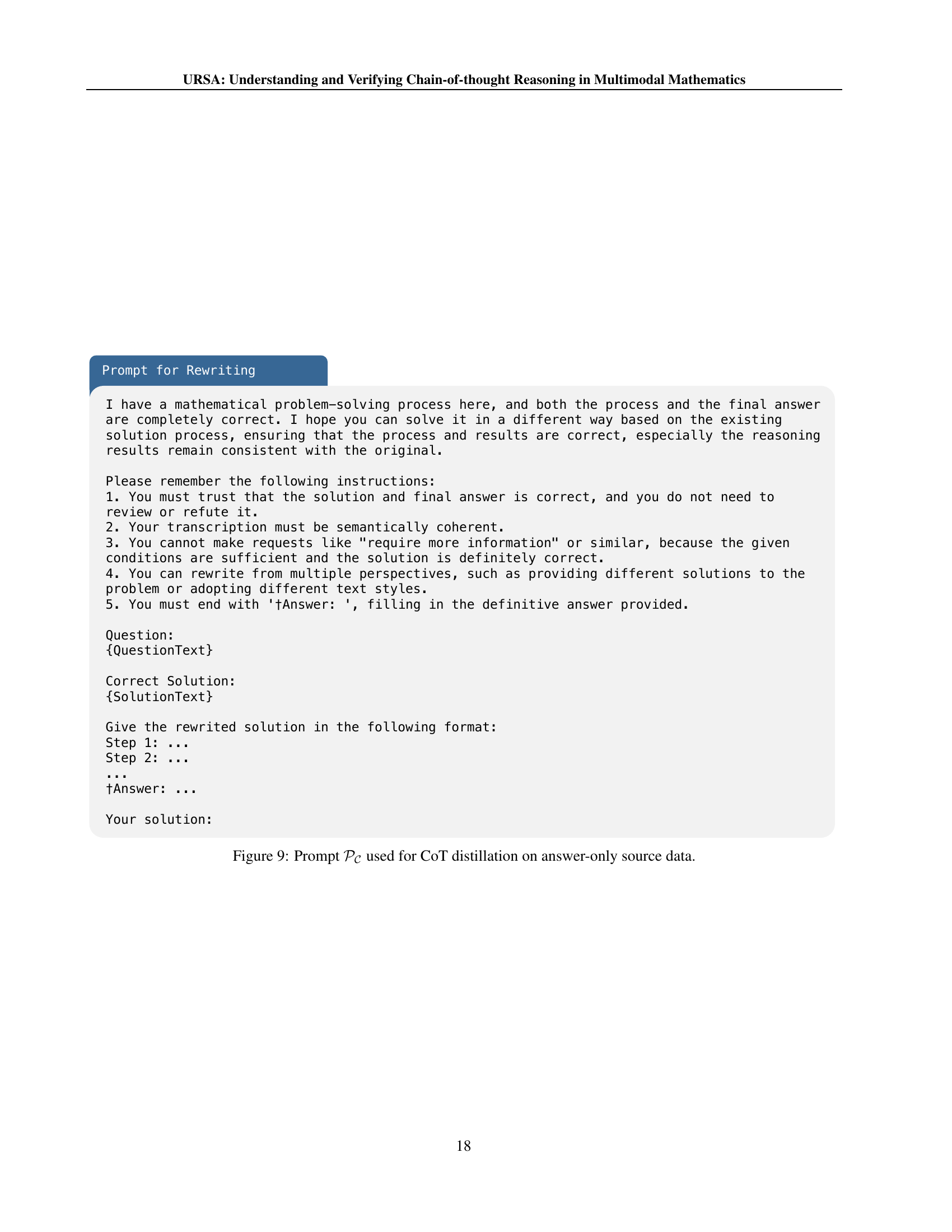

🔼 Prompt 𝒫𝒞 for CoT distillation is used to generate chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning from answer-only data. The prompt instructs the model to produce a step-by-step solution that leads to the given answer, emphasizing the importance of maintaining consistency between the generated reasoning and the provided answer. The prompt also ensures that the model doesn’t request additional information or express uncertainty, focusing instead on a clear and concise solution.

read the caption

Figure 9: Prompt 𝒫𝒞subscript𝒫𝒞\mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{C}}caligraphic_P start_POSTSUBSCRIPT caligraphic_C end_POSTSUBSCRIPT used for CoT distillation on answer-only source data.

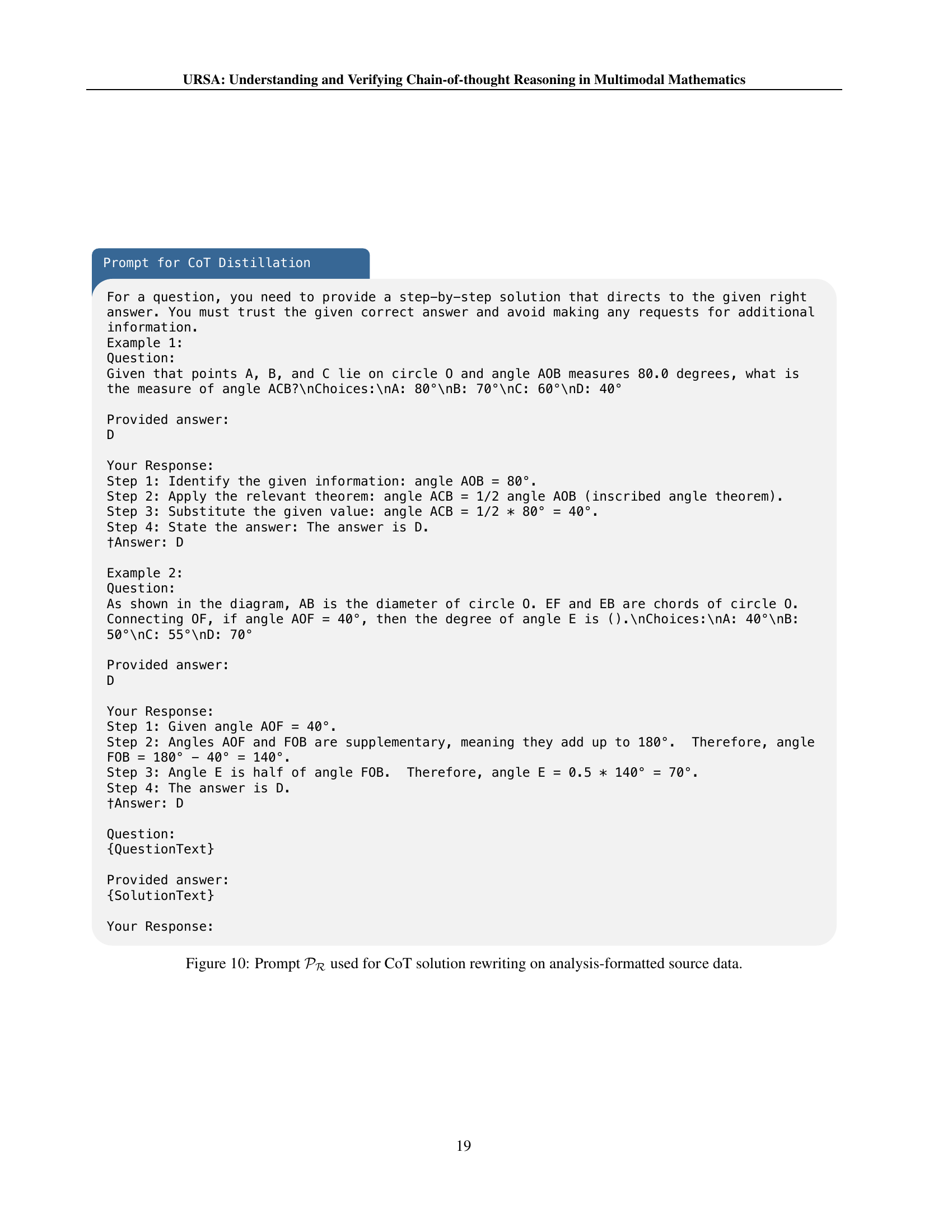

🔼 This figure shows the prompt used in the paper for the CoT solution rewriting task on analysis-formatted data. The prompt instructs the model to rewrite a given solution while maintaining the correctness of both the process and the final answer. It emphasizes the need for semantically coherent transcription and forbids the model from making requests or altering parts of the given solution.

read the caption

Figure 10: Prompt 𝒫ℛsubscript𝒫ℛ\mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{R}}caligraphic_P start_POSTSUBSCRIPT caligraphic_R end_POSTSUBSCRIPT used for CoT solution rewriting on analysis-formatted source data.

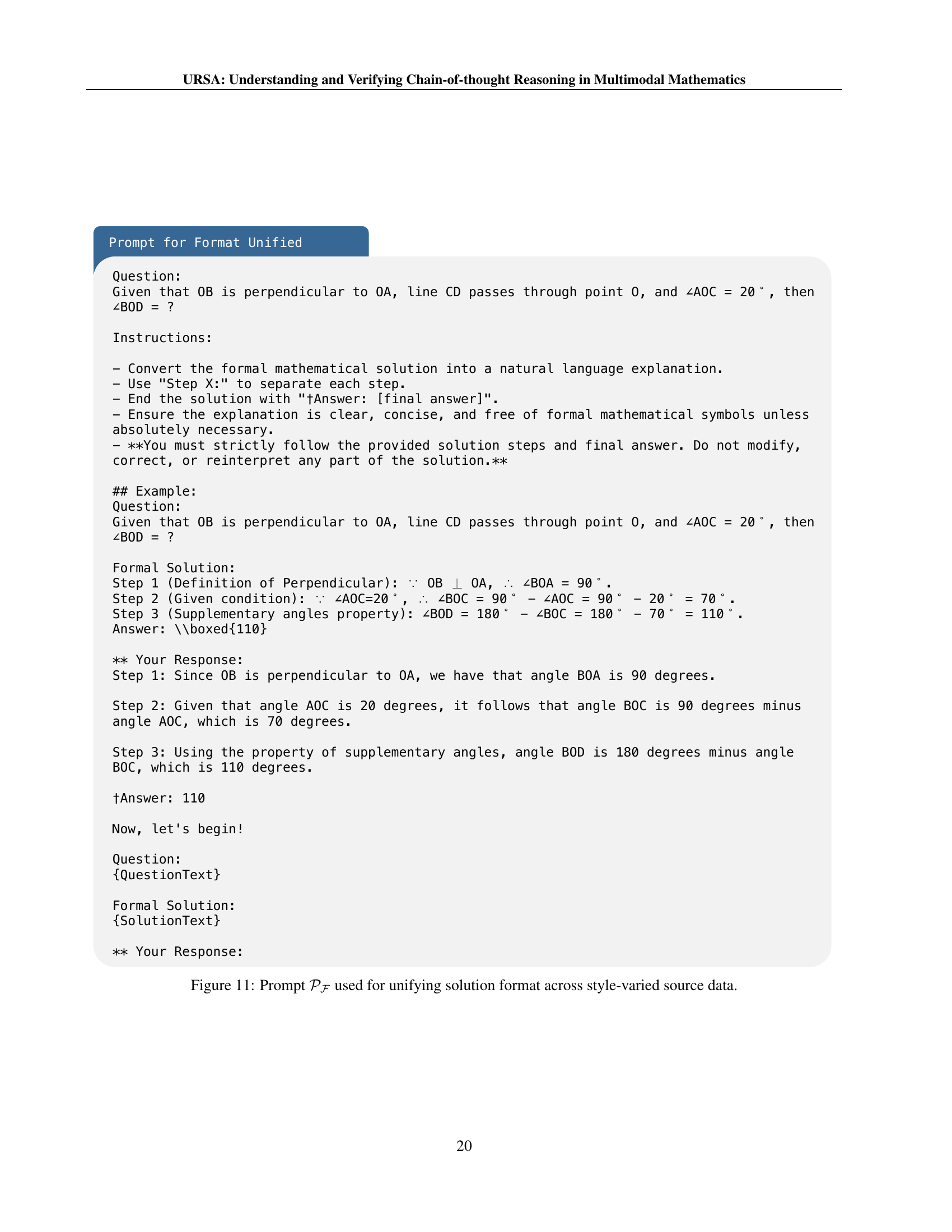

🔼 Prompt 𝒫ℱ used for unifying solution format across style-varied source data. This prompt is used in the data synthesis process for the instruction fine-tuning of the URSA-7B model. The prompt instructs the model to convert a formal mathematical solution into a natural language explanation, ensuring clarity, conciseness, and adherence to the original solution’s steps and final answer, avoiding modifications or reinterpretations.

read the caption

Figure 11: Prompt 𝒫ℱsubscript𝒫ℱ\mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{F}}caligraphic_P start_POSTSUBSCRIPT caligraphic_F end_POSTSUBSCRIPT used for unifying solution format across style-varied source data.

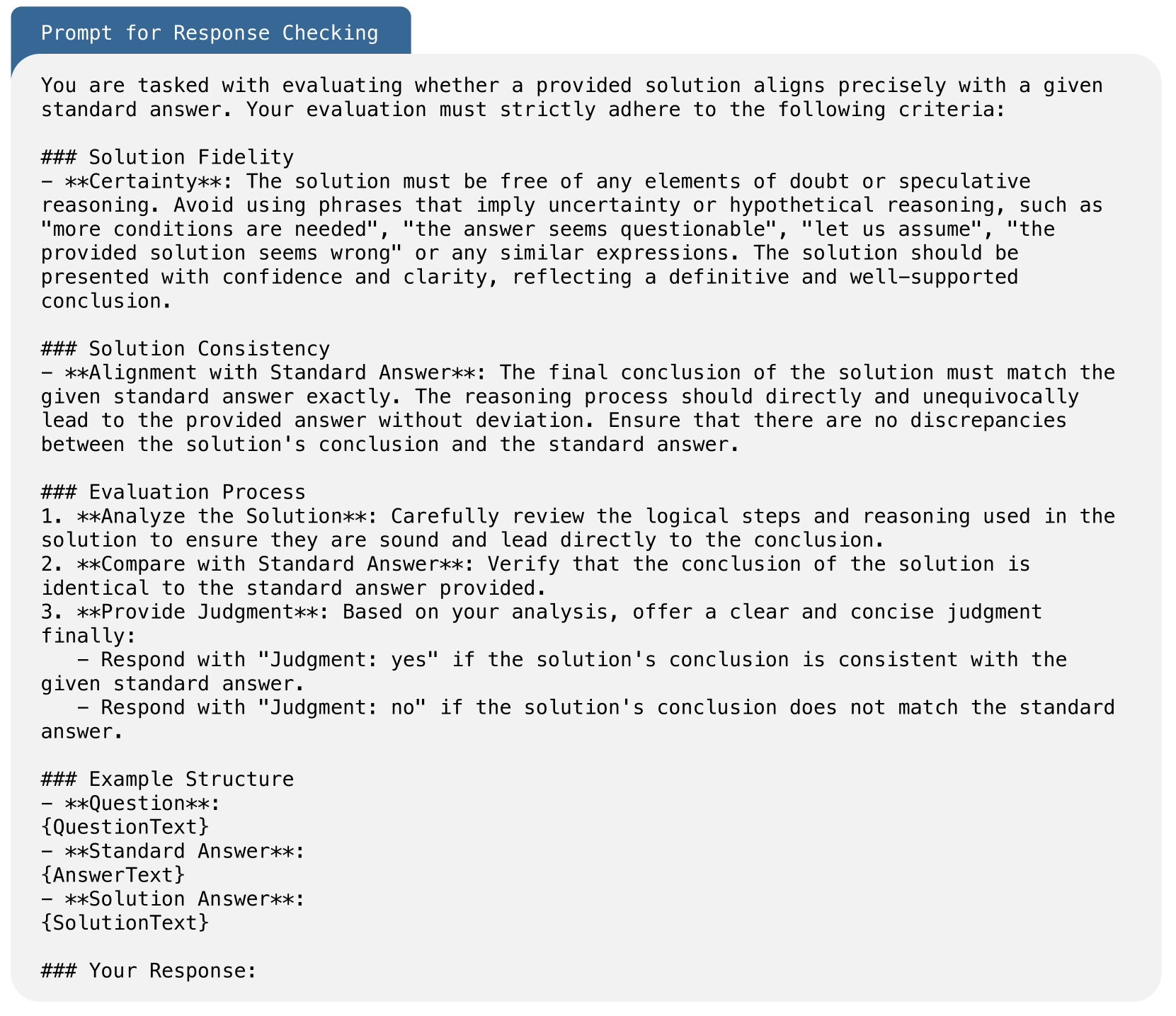

🔼 This figure shows the prompt used for evaluating the quality of chain-of-thought (CoT) augmentation responses. The prompt guides the evaluator to assess the response based on two key criteria: solution fidelity (whether the reasoning is sound and free of speculation, and whether the final conclusion matches the given standard answer) and solution consistency (whether the reasoning steps logically lead to the answer without discrepancies). The evaluator is instructed to provide a judgment of ‘yes’ or ’no’ based on this evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 12: Prompt used for checking CoT augmentation response based on consistency and correction.

🔼 This figure presents the prompt used for the misinterpretation insertion engine in the Dual-view Process Supervised Data Synthesis stage. The prompt instructs the model to introduce errors into a geometry problem solution by misreading the diagram and producing an incorrect answer. The process involves three stages: analyzing the correct solution, introducing a misinterpretation, and continuing reasoning with the misinterpretation to arrive at an incorrect answer. The prompt emphasizes that the misreading should be integrated naturally into the solution without explicit statements about making a misinterpretation, and the final answer should be marked with ‘†Answer:’.

read the caption

Figure 13: Prompt used for inserting interpretation into geometry-related samples.

🔼 This figure shows the prompt used in the misinterpretation insertion engine for function and statistics related samples. The prompt instructs the model to introduce errors into a solution by misinterpreting a coordinate axis or chart. The model must identify areas in the solution where diagram information is extracted, choose one area to introduce a misinterpretation, and continue the reasoning process to derive an incorrect answer. The response should be natural and avoid explicitly mentioning misinterpretations. The prompt includes tags to mark correct and incorrect steps and specifies that the final answer should not be tagged. The misinterpretation action must be consistent with the plan outlined in the prompt.

read the caption

Figure 14: Prompt used for inserting interpretation into function and statistics-related samples.

🔼 This figure shows a geometry problem from the MathVista-GPS dataset. The problem involves a quadrilateral ABCD where AD = 6, AB = 4, and DE bisects angle ADC, intersecting BC at point E. The question asks for the length of BE. The figure displays several different attempts to solve this problem using different methods. These attempts include a correct solution, and solutions produced by GPT-40, Gemini-1.5-Flash-002, MultiMath-7B, Math-LLaVA-13B, and URSA-7B. The figure highlights the different approaches and results obtained by each method, illustrating the variety of reasoning paths used to solve geometry problems and the different levels of accuracy achieved.

read the caption

Figure 15: Case on MathVista-GPS.

🔼 The figure displays a geometry problem from the MathVerse benchmark dataset. The problem involves a circle with a tangent line and several angles. The question asks for the length of a specific line segment (AP), given the length of another line segment (OP) and the measure of a particular angle (∠BOC). Different models’ solutions and their correctness are compared and illustrated.

read the caption

Figure 16: Case on MathVerse.

More on tables

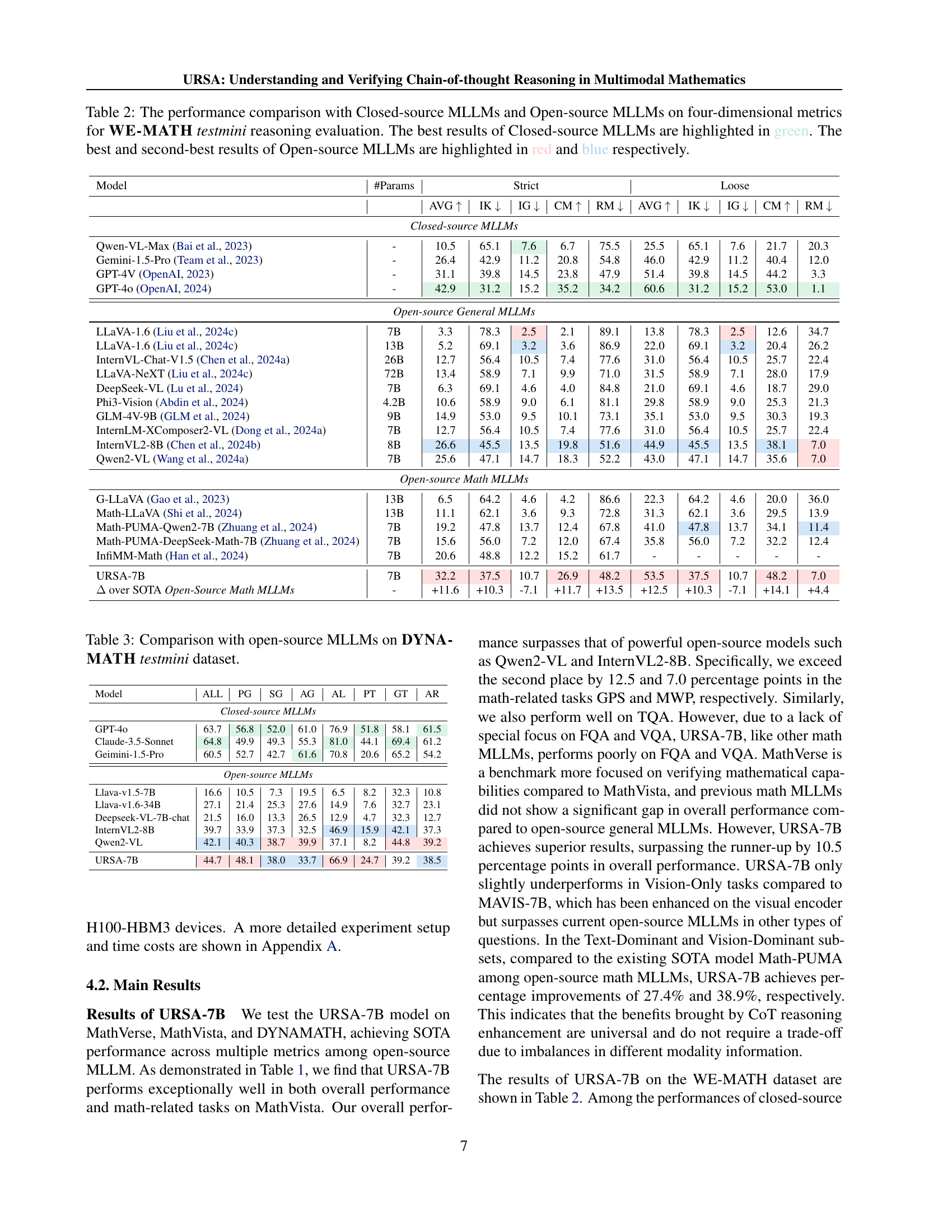

| Model | #Params | Strict AVG ↑ | Strict IK ↓ | Strict IG ↓ | Strict CM ↑ | Strict RM ↓ | Loose AVG ↑ | Loose IK ↓ | Loose IG ↓ | Loose CM ↑ | Loose RM ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-source MLLMs | |||||||||||

| Qwen-VL-Max [2023] | - | 10.5 | 65.1 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 75.5 | 25.5 | 65.1 | 7.6 | 21.7 | 20.3 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro [2023] | - | 26.4 | 42.9 | 11.2 | 20.8 | 54.8 | 46.0 | 42.9 | 11.2 | 40.4 | 12.0 |

| GPT-4V [2023] | - | 31.1 | 39.8 | 14.5 | 23.8 | 47.9 | 51.4 | 39.8 | 14.5 | 44.2 | 3.3 |

| GPT-4o [2024] | - | 42.9 | 31.2 | 15.2 | 35.2 | 34.2 | 60.6 | 31.2 | 15.2 | 53.0 | 1.1 |

| Open-source General MLLMs | |||||||||||

| LLaVA-1.6 [2024c] | 7B | 3.3 | 78.3 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 89.1 | 13.8 | 78.3 | 2.5 | 12.6 | 34.7 |

| LLaVA-1.6 [2024c] | 13B | 5.2 | 69.1 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 86.9 | 22.0 | 69.1 | 3.2 | 20.4 | 26.2 |

| InternVL-Chat-V1.5 [2024a] | 26B | 12.7 | 56.4 | 10.5 | 7.4 | 77.6 | 31.0 | 56.4 | 10.5 | 25.7 | 22.4 |

| LLaVA-NeXT [2024c] | 72B | 13.4 | 58.9 | 7.1 | 9.9 | 71.0 | 31.5 | 58.9 | 7.1 | 28.0 | 17.9 |

| DeepSeek-VL [2024] | 7B | 6.3 | 69.1 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 84.8 | 21.0 | 69.1 | 4.6 | 18.7 | 29.0 |

| Phi3-Vision [2024] | 4.2B | 10.6 | 58.9 | 9.0 | 6.1 | 81.1 | 29.8 | 58.9 | 9.0 | 25.3 | 21.3 |

| GLM-4V-9B [2024] | 9B | 14.9 | 53.0 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 73.1 | 35.1 | 53.0 | 9.5 | 30.3 | 19.3 |

| InternLM-XComposer2-VL [2024a] | 7B | 12.7 | 56.4 | 10.5 | 7.4 | 77.6 | 31.0 | 56.4 | 10.5 | 25.7 | 22.4 |

| InternVL2-8B [2024b] | 8B | 26.6 | 45.5 | 13.5 | 19.8 | 51.6 | 44.9 | 45.5 | 13.5 | 38.1 | 7.0 |

| Qwen2-VL [2024a] | 7B | 25.6 | 47.1 | 14.7 | 18.3 | 52.2 | 43.0 | 47.1 | 14.7 | 35.6 | 7.0 |

| Open-source Math MLLMs | |||||||||||

| G-LLaVA [2023] | 13B | 6.5 | 64.2 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 86.6 | 22.3 | 64.2 | 4.6 | 20.0 | 36.0 |

| Math-LLaVA [2024] | 13B | 11.1 | 62.1 | 3.6 | 9.3 | 72.8 | 31.3 | 62.1 | 3.6 | 29.5 | 13.9 |

| Math-PUMA-Qwen2-7B [2024] | 7B | 19.2 | 47.8 | 13.7 | 12.4 | 67.8 | 41.0 | 47.8 | 13.7 | 34.1 | 11.4 |

| Math-PUMA-DeepSeek-Math-7B [2024] | 7B | 15.6 | 56.0 | 7.2 | 12.0 | 67.4 | 35.8 | 56.0 | 7.2 | 32.2 | 12.4 |

| InfiMM-Math [2024] | 7B | 20.6 | 48.8 | 12.2 | 15.2 | 61.7 | - | - | - | - | - |

| URSA-7B | 7B | 32.2 | 37.5 | 10.7 | 26.9 | 48.2 | 53.5 | 37.5 | 10.7 | 48.2 | 7.0 |

| Δ over SOTA Open-Source Math MLLMs | +11.6 | +10.3 | -7.1 | +11.7 | +13.5 | +12.5 | +10.3 | -7.1 | +14.1 | +4.4 |

🔼 Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the WE-MATH testmini dataset, focusing on four key performance metrics: Average (AVG), Insufficient Knowledge (IK), Inadequate Generalization (IG), and Complete Mastery (CM). The models are categorized into closed-source and open-source LLMs, with the top-performing closed-source models highlighted in green and the top two open-source models highlighted in red and blue, respectively. This allows for a nuanced understanding of each model’s strengths and weaknesses in different aspects of mathematical reasoning, providing valuable insights into the current state-of-the-art in multimodal mathematical reasoning.

read the caption

Table 2: The performance comparison with Closed-source MLLMs and Open-source MLLMs on four-dimensional metrics for WE-MATH testmini reasoning evaluation. The best results of Closed-source MLLMs are highlighted in green. The best and second-best results of Open-source MLLMs are highlighted in red and blue respectively.

| Model | ALL | PG | SG | AG | AL | PT | GT | AR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-source MLLMs | ||||||||

| GPT-4o | 63.7 | 56.8 | 52.0 | 61.0 | 76.9 | 51.8 | 58.1 | 61.5 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet | 64.8 | 49.9 | 49.3 | 55.3 | 81.0 | 44.1 | 69.4 | 61.2 |

| Geimini-1.5-Pro | 60.5 | 52.7 | 42.7 | 61.6 | 70.8 | 20.6 | 65.2 | 54.2 |

| Open-source MLLMs | ||||||||

| Llava-v1.5-7B | 16.6 | 10.5 | 7.3 | 19.5 | 6.5 | 8.2 | 32.3 | 10.8 |

| Llava-v1.6-34B | 27.1 | 21.4 | 25.3 | 27.6 | 14.9 | 7.6 | 32.7 | 23.1 |

| Deepseek-VL-7B-chat | 21.5 | 16.0 | 13.3 | 26.5 | 12.9 | 4.7 | 32.3 | 12.7 |

| InternVL2-8B | 39.7 | 33.9 | 37.3 | 32.5 | 46.9 | 15.9 | 42.1 | 37.3 |

| Qwen2-VL | 42.1 | 40.3 | 38.7 | 39.9 | 37.1 | 8.2 | 44.8 | 39.2 |

| URSA-7B | 44.7 | 48.1 | 38.0 | 33.7 | 66.9 | 24.7 | 39.2 | 38.5 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of URSA-7B against other open-source large language models (LLMs) specifically designed for mathematical reasoning on the DYNAMATH testmini dataset. DYNAMATH is a benchmark designed to evaluate the robustness of LLMs in multimodal mathematical reasoning across different mathematical skill areas, problem types and difficulty levels. The table presents performance scores across various subtests of the DYNAMATH dataset, allowing for a detailed comparison of the models’ abilities in different mathematical reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison with open-source MLLMs on DYNAMATH testmini dataset.

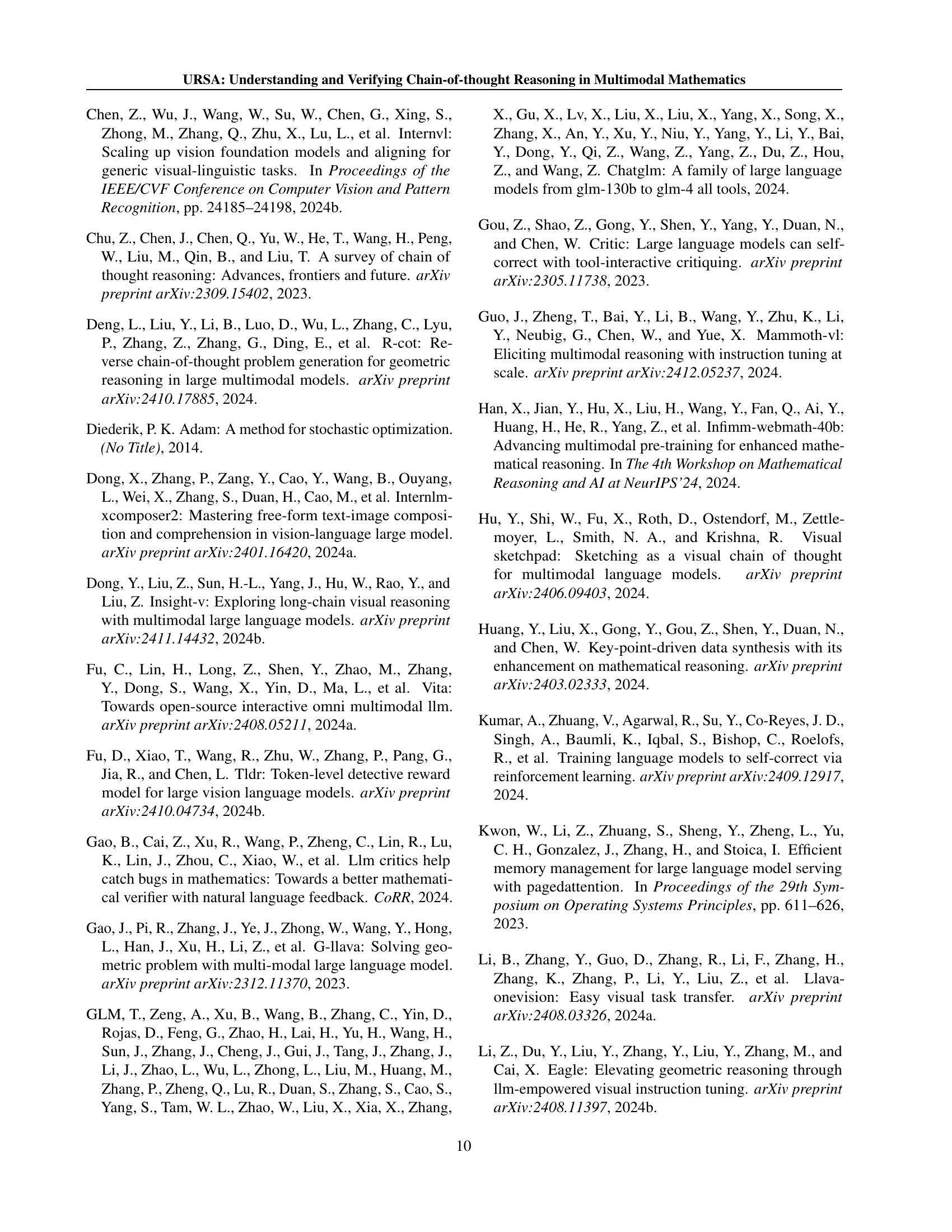

| Method | N=4 | N=8 | N=16 | N=32 | N=64 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MathVista-GPS | |||||

| Self-Consistency | 67.4 | 67.9 | 68.2 | 68.7 | 68.9 |

| URSA-RM-7B | 68.8 | 69.7 | 70.4 | 70.7 | 70.8 |

| MathVerse | |||||

| Self-Consistency | 29.1 | 29.7 | 30.1 | 30.2 | 30.2 |

| URSA-RM-7B | 31.0 | 32.7 | 33.0 | 33.2 | 33.0 |

🔼 This table presents the out-of-distribution (OOD) performance of the URSA-RM-7B model, which acts as a verifier, when evaluated on the Multimath-7B dataset. It compares the accuracy of URSA-RM-7B against a baseline method (Self-Consistency) for different sampling numbers (N). The results show how effectively URSA-RM-7B can enhance the reasoning capabilities of URSA-7B by identifying correct reasoning trajectories, particularly in OOD scenarios.

read the caption

Table 4: OOD performance when URSA-RM-7B works on Multimath-7B.

| Method | N=4 | N=8 | N=16 | N=32 | N=64 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MathVista-GPS | |||||

| URSA-RM-7B | 82.6 | 84.0 | 85.0 | 86.4 | 86.2 |

| URSA-RM-7B w/o 𝒮BEL | 80.1 | 81.7 | 82.2 | 83.1 | 83.0 |

| URSA-RM-7B w/o 𝒮MIE | 81.8 | 83.3 | 84.1 | 85.6 | 85.6 |

| MathVerse | |||||

| URSA-RM-7B | 53.2 | 54.2 | 54.7 | 55.0 | 54.8 |

| URSA-RM-7B w/o 𝒮BEL | 49.9 | 50.7 | 51.8 | 52.0 | 52.1 |

| URSA-RM-7B w/o 𝒮MIE | 52.8 | 53.7 | 53.8 | 53.9 | 53.8 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the URSA-RM-7B model. The study investigates the impact of removing specific components of the model’s training process on its performance. Specifically, it compares the performance of the full URSA-RM-7B model against versions where either the BinaryErrorLocating (SBEL) engine or the Misinterpretation Insertion Engine (SMIE) are removed. Results are reported for two separate benchmarks, MathVista-GPS and MathVerse, indicating how the removal of each component affects overall accuracy.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study on URSA-RM-7B.

| Hyperparameters & Cost | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 1e-4 | 1e-5 | 5e-6 |

| Epoch | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Warm-up Ratio | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Weight Decay | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Batch Size | 64 | 128 | 128 |

| Trainable Parts | Aligner | Vision Encoder, Aligner, Base LLM | Base LLM |

| Data Size | 960K | 1.0M | 1.1M |

| Time Cost | ~3.5h | ~11h | ~12h |

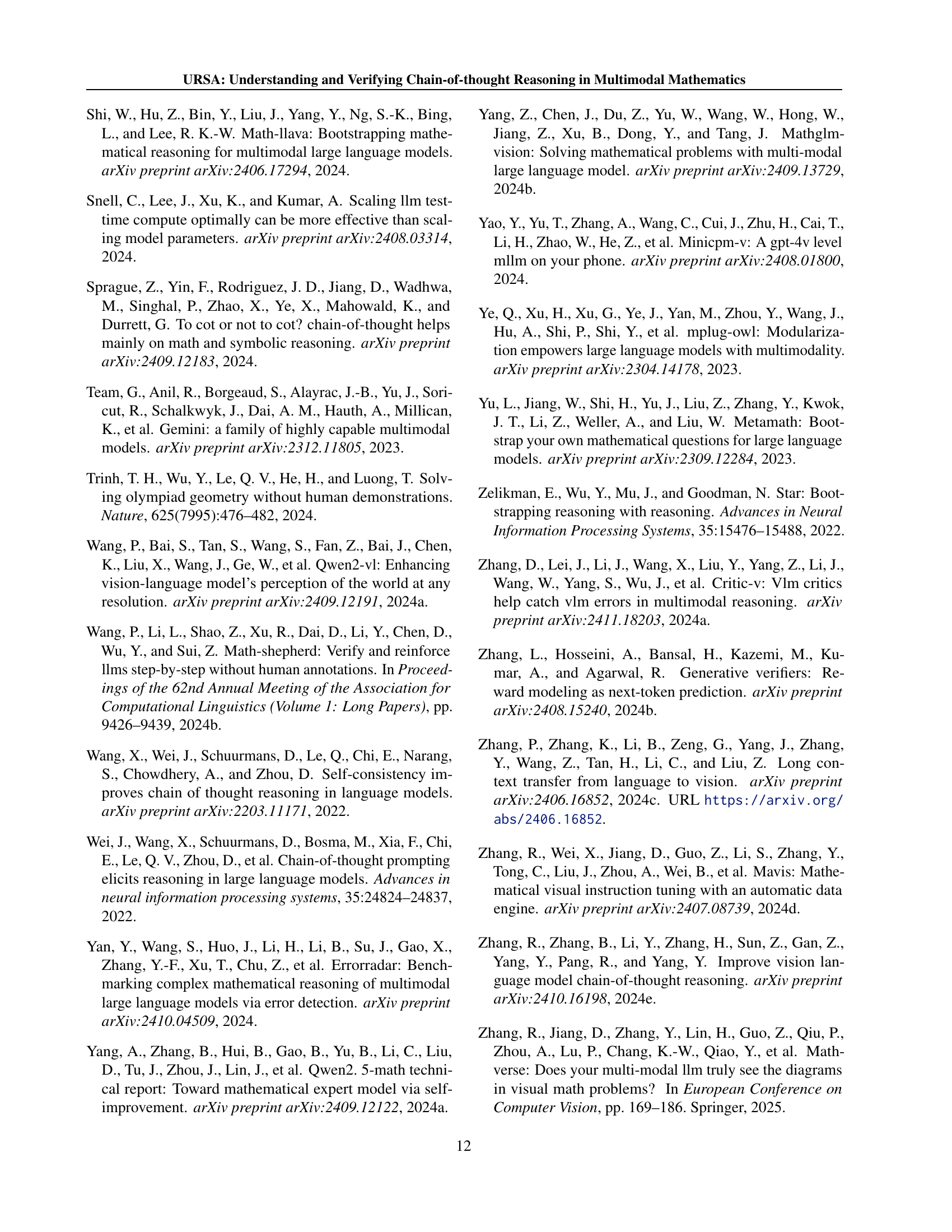

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used and the training time taken for each of the three stages in the training process of the URSA-7B model. It includes information such as learning rate, number of epochs, batch size, and which parts of the model were trained at each stage. The time cost is also provided for each stage.

read the caption

Table 6: Hyperparameter setting and training time cost.

| Model | #Params | ALL | ALG | ARI | GEO | LOG | NUM | SCI | STA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselines | |||||||||

| Random Choice | - | 17.9 | 25.8 | 13.8 | 22.7 | 13.4 | 8.8 | 15.8 | 14.3 |

| Human Performance | - | 60.3 | 50.9 | 59.2 | 51.4 | 40.7 | 53.8 | 64.9 | 63.9 |

| Closed-source MLLMs | |||||||||

| Qwen-VL-Plus (Bai et al., 2023) | - | 43.3 | 39.1 | 32.0 | 39.3 | 18.9 | 26.4 | 59.0 | 56.1 |

| GPT-4V (OpenAI, 2023) | - | 49.9 | 53.0 | 49.0 | 51.0 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 63.1 | 55.8 |

| Open-source Genreral MLLMs | |||||||||

| mPLUG-Owl2-7B (Ye et al., 2023) | 7B | 22.2 | 23.6 | 19.2 | 23.9 | 13.5 | 12.7 | 26.3 | 21.4 |

| LLaVA-1.5-13B (Liu et al., 2024c) | 13B | 25.7 | 19.6 | 28.6 | 17.6 | 10.8 | 27.8 | 33.6 | 22.9 |

| MiniGPT-v2 (Chen et al., 2023) | 7B | 23.1 | 28.1 | 21.0 | 24.7 | 16.2 | 16.7 | 25.4 | 17.9 |

| InternLM-XComposer2-VL-7B (Dong et al., 2024a) | 7B | 47.8 | 32.0 | 51.6 | 30.5 | 13.5 | 43.8 | 37.7 | 62.8 |

| SPHINX-MoE (Lin et al., 2023) | 8x7B | 42.3 | 31.7 | 41.6 | 30.5 | 16.2 | 27.1 | 50.8 | 50.8 |

| DeepSeek-VL (Lu et al., 2024) | 7B | 34.9 | 29.2 | 38.8 | 27.2 | 18.9 | 43.1 | 35.3 | 33.2 |

| InternVL2-8B (Chen et al., 2024b) | 8B | 58.3 | 59.8 | 56.4 | 60.3 | 10.8 | 30.6 | 59.0 | 68.8 |

| Qwen2-VL (Wang et al., 2024a) | 7B | 58.9 | 44.1 | 57.5 | 43.1 | 24.3 | 41.7 | 66.4 | 75.1 |

| Open-source Math MLLMs | |||||||||

| G-LLaVA (Gao et al., 2024) | 7B | 25.1 | 36.0 | 19.4 | 37.6 | 15.2 | 17.7 | 21.0 | 15.1 |

| Math-LLaVA (Shi et al., 2024) | 7B | 46.6 | 51.5 | 40.7 | 56.2 | 23.3 | 34.7 | 47.7 | 42.3 |

| Multimath-7B (Peng et al., 2024) | 7B | 50.0 | 61.9 | 42.2 | 64.9 | 23.3 | 32.6 | 42.6 | 49.2 |

| Math-PUMA-Qwen2-7B (Zhuang et al., 2024) | 7B | 47.9 | 47.7 | 46.2 | 47.3 | 21.6 | 32.6 | 42.6 | 55.8 |

| URSA-7B | 7B | 59.8 | 74.0 | 53.5 | 77.4 | 21.6 | 35.4 | 58.2 | 57.1 |

| Δ over SOTA Open-Source Math MLLMs | - | +9.8 | +12.1 | +7.3 | +12.5 | -1.7 | +0.7 | +10.5 | +1.3 |

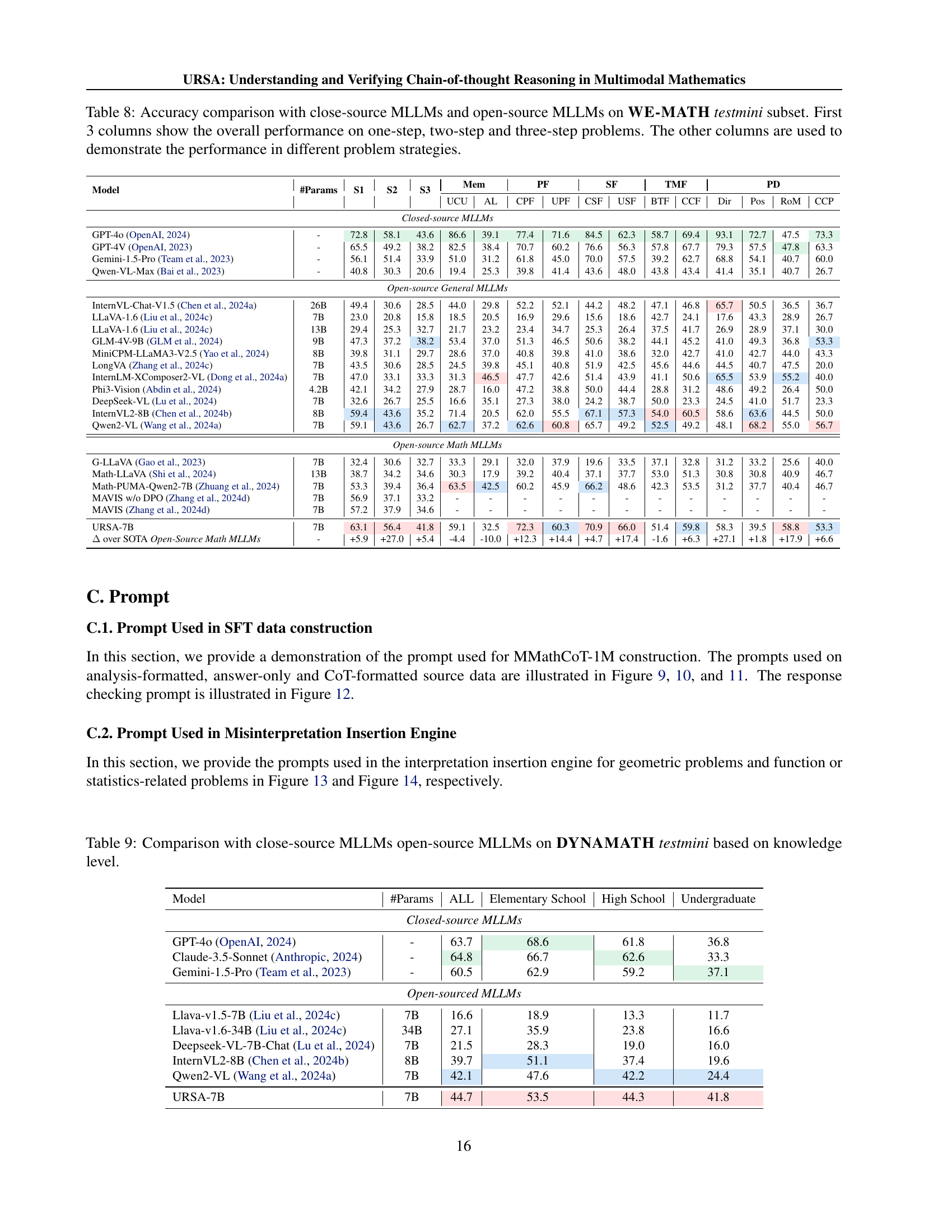

🔼 Table 7 presents a comparison of the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the MATHVISTA testmini dataset, focusing on their mathematical reasoning abilities. It compares both closed-source and open-source LLMs, providing a detailed breakdown of their accuracy across different mathematical subtasks (Algebra, Arithmetic, Geometry, Logic, Number, Science, Statistics). The table helps in assessing the relative strengths and weaknesses of different models in various mathematical domains.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison with close-source MLLMs open-source MLLMs on MATHVISTA testmini mathematics capabilities.

| Model | #Params | S1 | S2 | S3 | Mem UCU | Mem AL | PF CPF | PF UPF | SF CSF | SF USF | TMF BTF | TMF CCF | PD Dir | PD Pos | PD RoM | PD CCP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-source MLLMs | ||||||||||||||||

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) | - | 72.8 | 58.1 | 43.6 | 86.6 | 39.1 | 77.4 | 71.6 | 84.5 | 62.3 | 58.7 | 69.4 | 93.1 | 72.7 | 47.5 | 73.3 |

| GPT-4V (OpenAI, 2023) | - | 65.5 | 49.2 | 38.2 | 82.5 | 38.4 | 70.7 | 60.2 | 76.6 | 56.3 | 57.8 | 67.7 | 79.3 | 57.5 | 47.8 | 63.3 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro (Team et al., 2023) | - | 56.1 | 51.4 | 33.9 | 51.0 | 31.2 | 61.8 | 45.0 | 70.0 | 57.5 | 39.2 | 62.7 | 68.8 | 54.1 | 40.7 | 60.0 |

| Qwen-VL-Max (Bai et al., 2023) | - | 40.8 | 30.3 | 20.6 | 19.4 | 25.3 | 39.8 | 41.4 | 43.6 | 48.0 | 43.8 | 43.4 | 41.4 | 35.1 | 40.7 | 26.7 |

| Open-source General MLLMs | ||||||||||||||||

| InternVL-Chat-V1.5 (Chen et al., 2024a) | 26B | 49.4 | 30.6 | 28.5 | 44.0 | 29.8 | 52.2 | 52.1 | 44.2 | 48.2 | 47.1 | 65.7 | 50.5 | 36.5 | 36.7 | |

| LLaVA-1.6 (Liu et al., 2024c) | 7B | 23.0 | 20.8 | 15.8 | 18.5 | 20.5 | 16.9 | 29.6 | 15.6 | 18.6 | 42.7 | 24.1 | 17.6 | 43.3 | 28.9 | 26.7 |

| LLaVA-1.6 (Liu et al., 2024c) | 13B | 29.4 | 25.3 | 32.7 | 21.7 | 23.2 | 23.4 | 34.7 | 25.3 | 26.4 | 37.5 | 41.7 | 26.9 | 28.9 | 37.1 | 30.0 |

| GLM-4V-9B (GLM et al., 2024) | 9B | 47.3 | 37.2 | 38.2 | 53.4 | 37.0 | 51.3 | 46.5 | 50.6 | 38.2 | 44.1 | 45.2 | 41.0 | 49.3 | 36.8 | 53.3 |

| MiniCPM-LLaMA3-V2.5 (Yao et al., 2024) | 8B | 39.8 | 31.1 | 29.7 | 28.6 | 37.0 | 40.8 | 39.8 | 41.0 | 38.6 | 32.0 | 42.7 | 41.0 | 42.7 | 44.0 | 43.3 |

| LongVA (Zhang et al., 2024c) | 7B | 43.5 | 30.6 | 28.5 | 24.5 | 39.8 | 45.1 | 40.8 | 51.9 | 42.5 | 45.6 | 44.6 | 44.5 | 40.7 | 47.5 | 20.0 |

| InternLM-XComposer2-VL (Dong et al., 2024a) | 7B | 47.0 | 33.1 | 33.3 | 31.3 | 46.5 | 47.7 | 42.6 | 51.4 | 43.9 | 41.1 | 50.6 | 65.5 | 53.9 | 55.2 | 40.0 |

| Phi3-Vision (Abdin et al., 2024) | 4.2B | 42.1 | 34.2 | 27.9 | 28.7 | 16.0 | 47.2 | 38.8 | 50.0 | 44.4 | 28.8 | 31.2 | 48.6 | 49.2 | 26.4 | 50.0 |

| DeepSeek-VL (Lu et al., 2024) | 7B | 32.6 | 26.7 | 25.5 | 16.6 | 35.1 | 27.3 | 38.0 | 24.2 | 38.7 | 50.0 | 23.3 | 24.5 | 41.0 | 51.7 | 23.3 |

| InternVL2-8B (Chen et al., 2024b) | 8B | 59.4 | 43.6 | 35.2 | 71.4 | 20.5 | 62.0 | 55.5 | 67.1 | 57.3 | 54.0 | 60.5 | 58.6 | 63.6 | 44.5 | 50.0 |

| Qwen2-VL (Wang et al., 2024a) | 7B | 59.1 | 43.6 | 26.7 | 62.7 | 37.2 | 62.6 | 60.8 | 65.7 | 49.2 | 52.5 | 49.2 | 48.1 | 68.2 | 55.0 | 56.7 |

| Open-source Math MLLMs | ||||||||||||||||

| G-LLaVA (Gao et al., 2023) | 7B | 32.4 | 30.6 | 32.7 | 33.3 | 29.1 | 32.0 | 37.9 | 19.6 | 33.5 | 37.1 | 32.8 | 31.2 | 33.2 | 25.6 | 40.0 |

| Math-LLaVA (Shi et al., 2024) | 13B | 38.7 | 34.2 | 34.6 | 30.3 | 17.9 | 39.2 | 40.4 | 37.1 | 37.7 | 53.0 | 51.3 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 40.9 | 46.7 |

| Math-PUMA-Qwen2-7B (Zhuang et al., 2024) | 7B | 53.3 | 39.4 | 36.4 | 63.5 | 42.5 | 60.2 | 45.9 | 66.2 | 48.6 | 42.3 | 53.5 | 31.2 | 37.7 | 40.4 | 46.7 |

| MAVIS w/o DPO (Zhang et al., 2024d) | 7B | 56.9 | 37.1 | 33.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MAVIS (Zhang et al., 2024d) | 7B | 57.2 | 37.9 | 34.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| URSA-7B | 7B | 63.1 | 56.4 | 41.8 | 59.1 | 32.5 | 72.3 | 60.3 | 70.9 | 66.0 | 51.4 | 59.8 | 58.3 | 39.5 | 58.8 | 53.3 |

| Δ over SOTA Open-Source Math MLLMs | - | +5.9 | +27.0 | +5.4 | -4.4 | -10.0 | +12.3 | +14.4 | +4.7 | +17.4 | -1.6 | +6.3 | +27.1 | +1.8 | +17.9 | +6.6 |

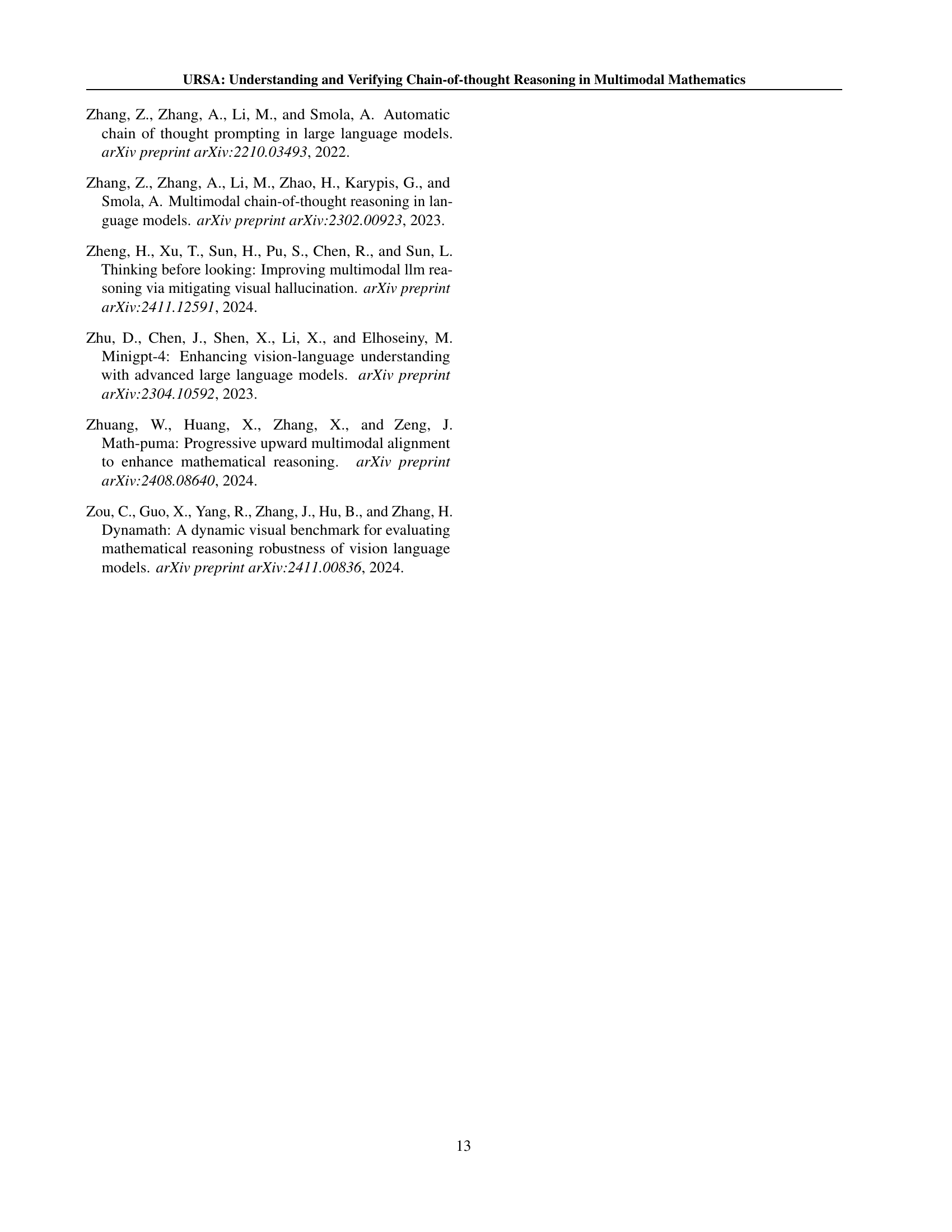

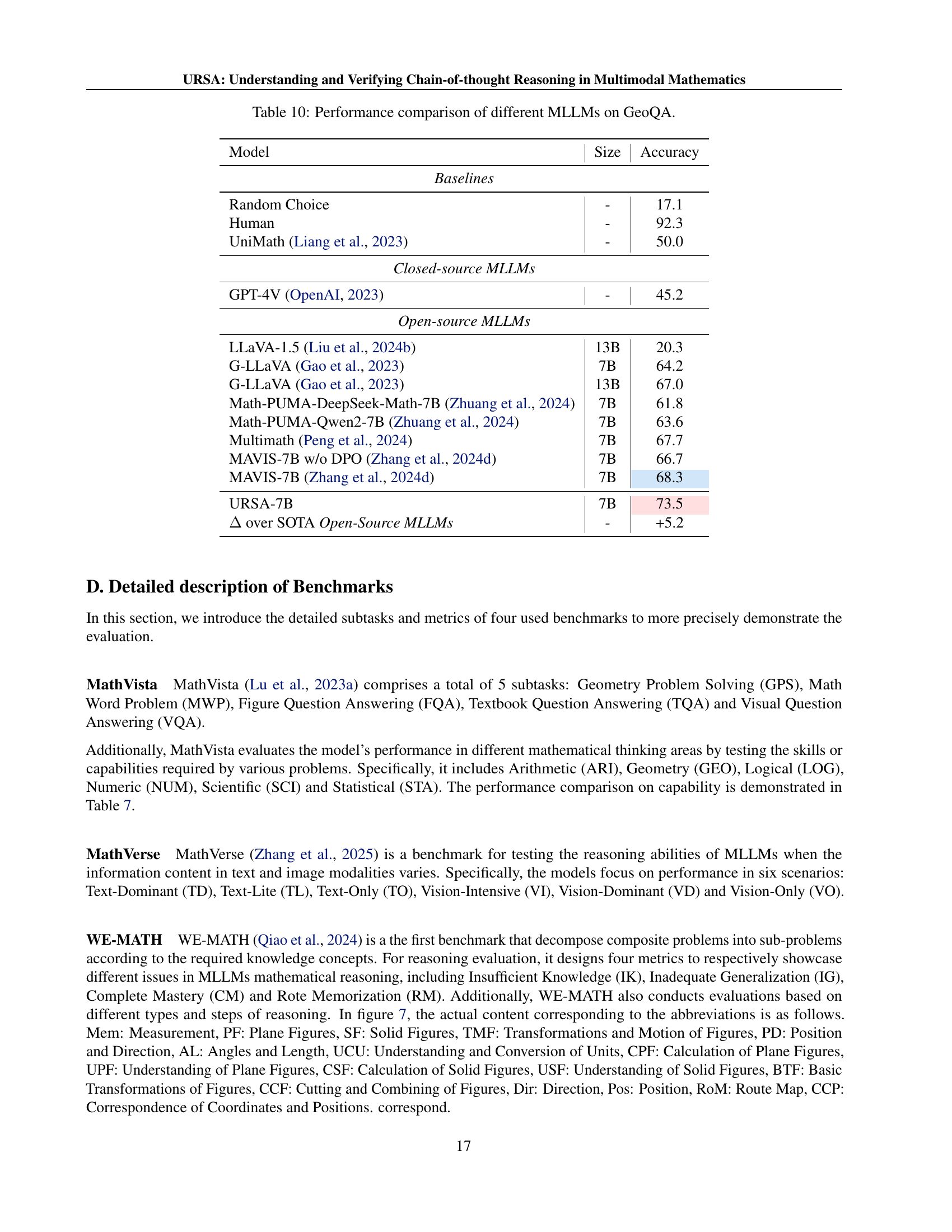

🔼 Table 8 presents a detailed comparison of the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the WE-MATH testmini subset. The table is organized to show the overall accuracy of each model across different problem complexities (one-step, two-step, and three-step problems). Additionally, it provides a more granular breakdown of performance based on different problem-solving strategies, offering insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each model in various mathematical reasoning approaches.

read the caption

Table 8: Accuracy comparison with close-source MLLMs and open-source MLLMs on WE-MATH testmini subset. First 3 columns show the overall performance on one-step, two-step and three-step problems. The other columns are used to demonstrate the performance in different problem strategies.

| Model | #Params | ALL | Elementary School | High School | Undergraduate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-source MLLMs | |||||

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) | - | 63.7 | 68.6 | 61.8 | 36.8 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet (Anthropic, 2024) | - | 64.8 | 66.7 | 62.6 | 33.3 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro (Team et al., 2023) | - | 60.5 | 62.9 | 59.2 | 37.1 |

| Open-sourced MLLMs | |||||

| Llava-v1.5-7B (Liu et al., 2024c) | 7B | 16.6 | 18.9 | 13.3 | 11.7 |

| Llava-v1.6-34B (Liu et al., 2024c) | 34B | 27.1 | 35.9 | 23.8 | 16.6 |

| Deepseek-VL-7B-Chat (Lu et al., 2024) | 7B | 21.5 | 28.3 | 19.0 | 16.0 |

| InternVL2-8B (Chen et al., 2024b) | 8B | 39.7 | 51.1 | 37.4 | 19.6 |

| Qwen2-VL (Wang et al., 2024a) | 7B | 42.1 | 47.6 | 42.2 | 24.4 |

| URSA-7B | 7B | 44.7 | 53.5 | 44.3 | 41.8 |

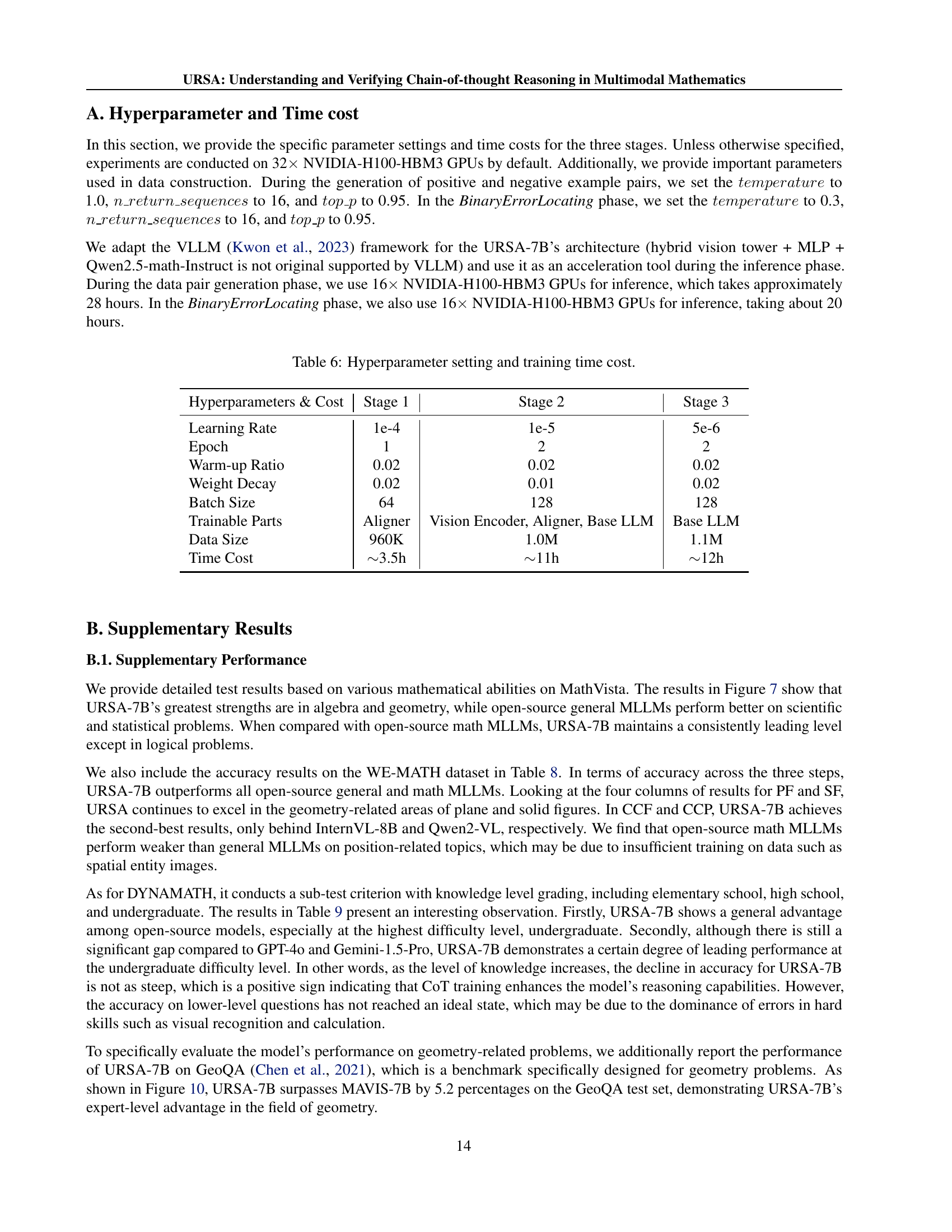

🔼 This table compares the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on the DYNAMATH testmini dataset, categorized by knowledge level (elementary school, high school, undergraduate). It shows the overall accuracy of each model at these three knowledge levels, allowing for comparison of model performance across different levels of mathematical complexity.

read the caption

Table 9: Comparison with close-source MLLMs open-source MLLMs on DYNAMATH testmini based on knowledge level.

| Model | Size | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Baselines | ||

| Random Choice | - | 17.1 |

| Human | - | 92.3 |

| UniMath (Liang et al., 2023) | - | 50.0 |

| Closed-source MLLMs | ||

| GPT-4V (OpenAI, 2023) | - | 45.2 |

| Open-source MLLMs | ||

| LLaVA-1.5 (Liu et al., 2024b) | 13B | 20.3 |

| G-LLaVA (Gao et al., 2023) | 7B | 64.2 |

| G-LLaVA (Gao et al., 2023) | 13B | 67.0 |

| Math-PUMA-DeepSeek-Math-7B (Zhuang et al., 2024) | 7B | 61.8 |

| Math-PUMA-Qwen2-7B (Zhuang et al., 2024) | 7B | 63.6 |

| Multimath (Peng et al., 2024) | 7B | 67.7 |

| MAVIS-7B w/o DPO (Zhang et al., 2024d) | 7B | 66.7 |

| MAVIS-7B (Zhang et al., 2024d) | 7B | 68.3 |

| URSA-7B | 7B | 73.5 |

| Δ over SOTA Open-Source MLLMs | - | +5.2 |

🔼 Table 10 presents a performance comparison of various Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) on the GeoQA benchmark. GeoQA specifically tests the ability of MLLMs to solve geometric reasoning problems. The table compares the accuracy of different models, including both closed-source and open-source models, across varying model sizes (parameters). This allows for an assessment of the impact of model size on geometric reasoning capabilities.

read the caption

Table 10: Performance comparison of different MLLMs on GeoQA.

Full paper#