TL;DR#

The research explores whether state-of-the-art generative video models truly understand physics, or simply mimic visual realism without grasping physical laws. Existing benchmarks primarily focus on visual fidelity rather than physical understanding, neglecting whether models can reliably extrapolate knowledge to novel scenarios involving complex interactions. This lack of evaluation leads to an ongoing debate about the true capabilities of these models.

To address this, researchers developed Physics-IQ, a benchmark dataset designed to specifically test physical understanding. This dataset includes diverse scenarios requiring knowledge of multiple physical principles such as fluid dynamics, solid mechanics, and optics. The evaluation involved testing several popular video generation models on this dataset and employing novel metrics to assess not only where and when actions occur but also how much and how they happen. Results showed that even the best-performing models demonstrated limited physical understanding, highlighting the critical need for improved physical reasoning in AI video generation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel benchmark, Physics-IQ, to rigorously evaluate physical understanding in video generative models. It reveals a significant gap between visual realism and actual physical comprehension in current models, highlighting a critical area for improvement and opening avenues for future research in AI and physical reasoning.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 presents example scenarios from the Physics-IQ benchmark dataset, designed to evaluate the physical understanding capabilities of video generative models. Each scenario tests a specific aspect of physics (Solid Mechanics, Fluid Dynamics, Optics, Thermodynamics, and Magnetism). The models receive either a single frame (for image-to-video models) or a 3-second video clip (for video-to-video models) as input, and are then tasked with predicting the next 5 seconds of the video. Successful prediction necessitates an understanding of the relevant physical principles involved in each scene.

read the caption

Figure 1: Sample scenarios from the Physics-IQ dataset for testing physical understanding in generative video models. Models are shown the beginning of a video (single frame for image2video models; 3 seconds for video2video models) and need to predict how the video continues over the next 5 seconds, which requires understanding different physical properties: Solid Mechanics, Fluid Dynamics, Optics, Thermodynamics, and Magnetism. See here for an animated version of this figure.

| Model | Spatial IoU | Spatiotemporal IoU | Weighted spatial IoU | MSE | Physics-IQ Score |

| Physical Variance | 0.645 | 0.512 | 0.626 | 0.002 | 100.0 |

| VideoPoet (multiframe) | 0.245 | 0.143 | 0.054 | 0.010 | 24.1 |

| Runway Gen 3 (i2v) | 0.220 | 0.109 | 0.044 | 0.015 | 18.4 |

| Lumiere (multiframe) | 0.170 | 0.146 | 0.034 | 0.013 | 18.2 |

| VideoPoet (i2v) | 0.175 | 0.106 | 0.057 | 0.012 | 18.0 |

| Lumiere (i2v) | 0.138 | 0.165 | 0.024 | 0.016 | 17.1 |

| Stable Video Diffusion (i2v) | 0.139 | 0.054 | 0.088 | 0.021 | 13.5 |

| Pika 1.0 (i2v) | 0.151 | 0.034 | 0.026 | 0.014 | 9.5 |

| Sora (i2v) | 0.142 | 0.041 | 0.055 | 0.036 | 8.7 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of eight different video generative models’ performance on four metrics designed to evaluate physical understanding in videos. Each metric assesses a different aspect of physical realism: Spatial IoU (location of action), Spatiotemporal IoU (location and timing of action), Weighted spatial IoU (location and amount of action), and MSE (pixel-level accuracy). The table shows each model’s score on each metric, with the best-performing model for each metric highlighted in bold. Crucially, the ‘Physical Variance’ row provides a baseline representing the inherent variability found in real-world physical phenomena – representing the best possible score attainable, a score achieved by the natural variation of two recordings of the same physical event. This allows comparison of how well models capture true physical understanding compared to just replicating visual similarities of real videos.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of metric scores for different models. The best-performing model for each metric is marked in bold. Note that Physical Variance serves as a performance upper bound for each metric, representing the difference between two real videos and capturing the inherent variability in real-world scenarios.

In-depth insights#

Physics IQ Dataset#

The Physics-IQ dataset represents a novel benchmark designed to rigorously evaluate the physical understanding of video generative models. Unlike previous benchmarks that rely on synthetic data, Physics-IQ leverages real-world videos depicting diverse physical phenomena. This focus on real-world data is crucial as it bridges the gap between simulated environments and the complexities of the physical world. The dataset’s strength lies in its carefully designed scenarios, testing understanding across various physical principles (fluid dynamics, optics, solid mechanics, thermodynamics, magnetism), and the use of multiple camera angles to capture diverse perspectives. By requiring models to predict video continuations, Physics-IQ assesses not just visual realism, but also genuine understanding of physical laws. The use of multiple evaluation metrics provides a multifaceted assessment of model performance, going beyond simple visual fidelity.

Model Evaluation#

Model evaluation in this research is multifaceted and crucial. The authors wisely move beyond simple visual metrics (like PSNR or SSIM) which don’t capture physical understanding. Instead, they introduce a novel benchmark, Physics-IQ, with metrics assessing not only where and when actions occur, but also how much and how realistically they unfold. This nuanced approach using metrics like Spatial IoU, Spatiotemporal IoU, Weighted Spatial IoU, and MSE is vital for distinguishing true comprehension of physics from mere visual mimicry. The inclusion of a multimodal large language model (MLLM) evaluation provides an additional layer, assessing the visual realism independent of physical accuracy, highlighting the critical difference between visual fidelity and genuine physical understanding. The results underscore the limitations of current models in grasping physical principles, despite achieving considerable visual realism in some cases. This comprehensive evaluation strategy is a major strength of the paper, offering a more robust and insightful analysis than solely relying on superficial metrics.

Visual vs. Physics#

The core question explored in the research is whether visually realistic video generation automatically implies an understanding of underlying physics. The paper contrasts visual realism, achieved through sophisticated pattern recognition and prediction, with true physical understanding, requiring knowledge of fundamental physical principles. The key finding is a significant disconnect between these two aspects: models can generate impressive visuals without necessarily grasping the physics behind the scenes. This highlights a crucial limitation of current AI video generation: visual fidelity is not a sufficient proxy for genuine understanding of the physical world. The benchmark developed in the paper directly assesses physical understanding, offering valuable insights into the limitations of current approaches and potential avenues for future research focusing on imbuing AI models with a more robust grasp of physics. Future work should focus on bridging this gap, perhaps through methods that incorporate interaction and causal reasoning. The results underscore the importance of moving beyond solely evaluating visual quality and embracing assessment of the fundamental physical knowledge embedded within the generated videos.

Limitations & Bias#

A critical analysis of the research paper should include a section on limitations and biases. Dataset limitations could stem from the real-world nature of the data, leading to uncontrolled variability and making it difficult to isolate specific factors. The benchmark’s focus on specific physical principles might limit its generalizability to broader AI capabilities. Model selection may not be fully representative of the current state of AI video generation, creating bias in the conclusions. The evaluation metrics, while novel, are proxy measures for physical understanding and may not fully capture the intricacies of complex physical reasoning. Subjectivity in the selection of success and failure examples also introduces potential bias. A thorough discussion of these limitations and biases is crucial for assessing the validity and robustness of the research findings and paving the way for future improvements in the field. Finally, acknowledging the limitations of the study design strengthens its credibility by highlighting areas where further research is needed.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize developing more sophisticated metrics for evaluating physical understanding in video generation models, moving beyond simplistic visual comparisons to capture nuanced aspects of physical interaction. Exploring alternative training paradigms that incorporate active interaction and feedback, rather than passive observation, could significantly improve a model’s ability to learn true physical principles. Investigating different model architectures explicitly designed for physics simulation, possibly incorporating physics engines or symbolic reasoning, could also lead to breakthroughs. Furthermore, it’s crucial to create larger and more diverse datasets that cover a wider range of physical phenomena and environmental conditions, ensuring better generalization and robustness. Finally, addressing hallucinations and biases present in current models through improved training techniques or model regularization is essential to enhance the reliability and accuracy of generated videos.

More visual insights#

More on figures

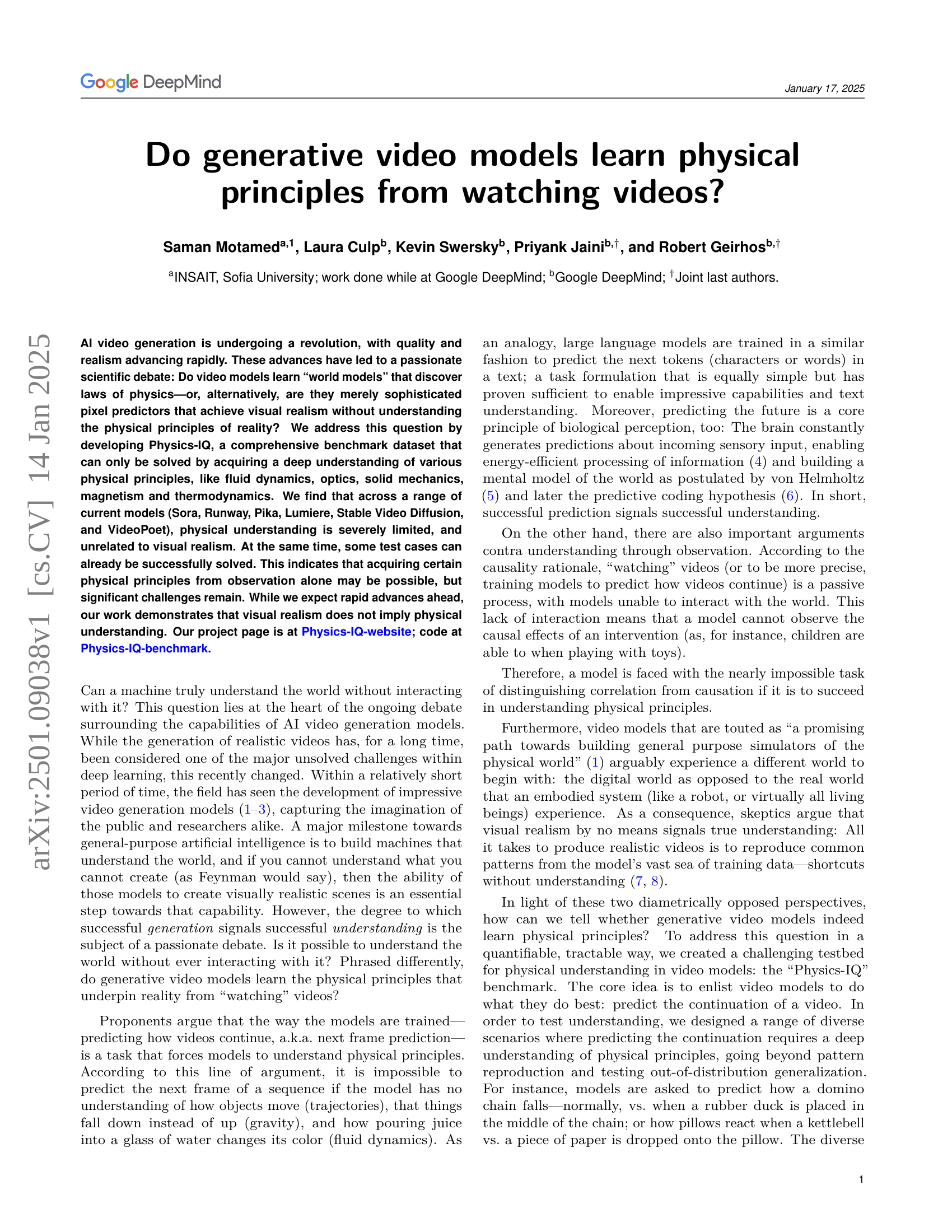

🔼 This figure illustrates the Physics-IQ evaluation process. A video generation model is given a short video clip (conditioning frames) as input, optionally along with a text description if the model supports it. The model then predicts a 5-second continuation of the video. This prediction is compared to the actual video (ground truth test frames) using four metrics: Spatial IoU, Spatiotemporal IoU, Weighted spatial IoU, and MSE. These metrics assess different aspects of physical understanding, such as the location, timing, extent, and precision of the predicted actions. The results from these metrics help determine how well the model understands the physics of the scene. The code for running this evaluation is publicly available on the Physics-IQ-benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of the Physics-IQ evaluation protocol. A video generative model produces a 5 second continuation of the conditioning frame(s), optionally including a textual description of the conditioning frames for models that accept text input. They are compared against the ground truth test frames using four metrics that quantify different properties of physical understanding. The metrics are defined and explained in the methods section. Code to run the evaluation is available at Physics-IQ-benchmark.

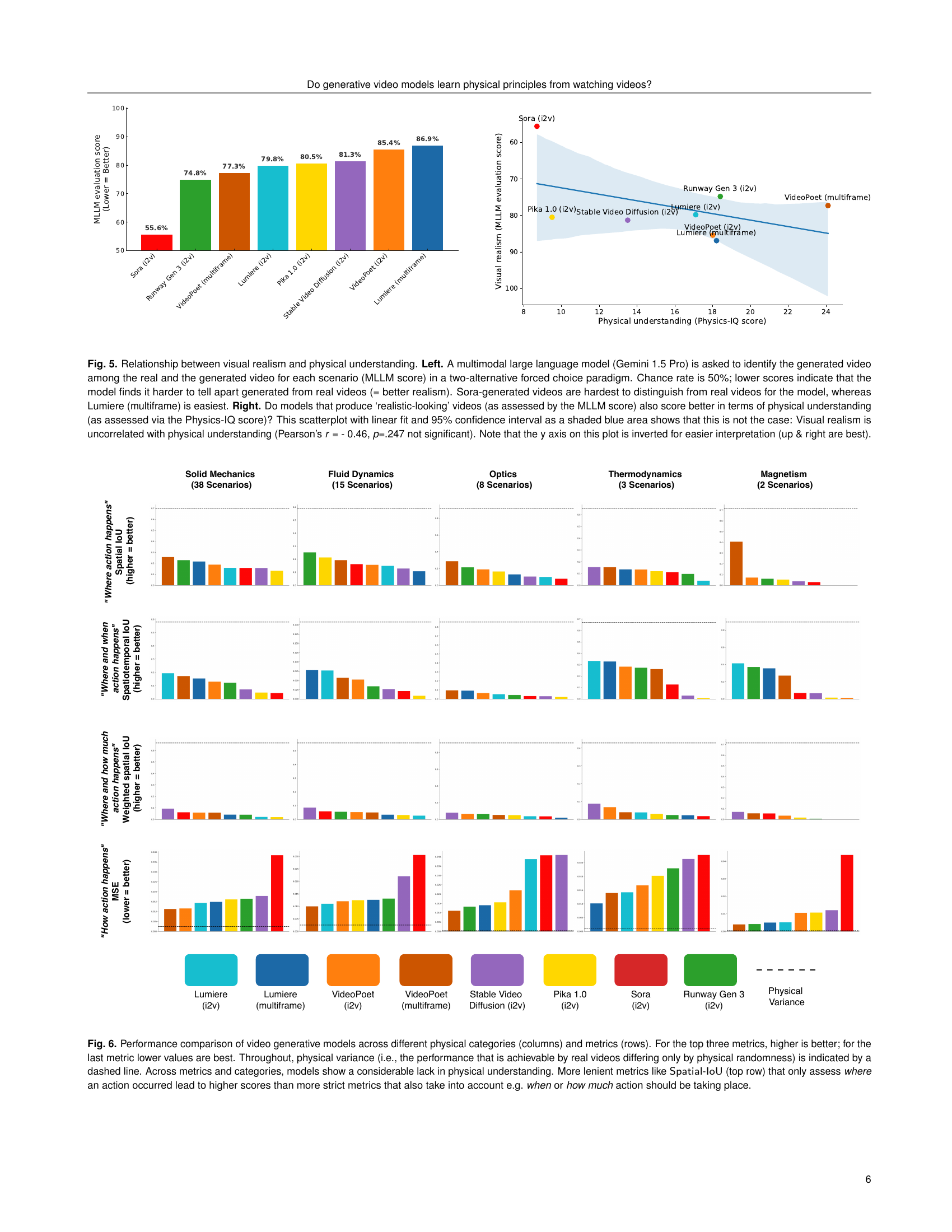

🔼 Figure 3 showcases several existing datasets used for evaluating physical reasoning in AI models. These datasets, including CRAFT, IntPhys, Physion, ESPRIT, Physion++, CoPhy, CLEVERER, and PhyWorld, all use synthetic data (computer-generated) rather than real-world video data. While effective for their intended purposes, using them to evaluate models trained on real videos is problematic because the characteristics of the simulated environments differ significantly from the real-world data distribution, potentially leading to inaccurate assessment of a model’s capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 3: A qualitative overview of recent synthetic datasets related to physical understanding (19, 20, 17, 38, 18, 36, 37, 39). These datasets are great for the purposes they were designed for, but not ideal for evaluating models trained on real-world videos due to the distribution shift.

🔼 Figure 4 assesses the physical understanding of eight different video generative models using the Physics-IQ benchmark. The left panel displays the Physics-IQ scores, which aggregate four individual metrics (Spatial IoU, Spatiotemporal IoU, Weighted spatial IoU, and MSE) measuring different aspects of physical understanding. The scores are normalized so that pairs of real videos differing only by random physical variations score 100%. The results reveal a significant gap between model performance and this upper bound, with the best-performing model reaching only 24.1%, highlighting the models’ limited physical understanding. The right panel complements this by showing the mean rank of models across the four metrics. The high Spearman correlation (-0.87, p < 0.005) between the aggregated Physics-IQ scores and the mean ranks confirms that aggregating the four metrics into a single Physics-IQ score effectively reflects model performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: How well do current video generative models understand physical principles? Left. The Physics-IQ score is an aggregated measure across four individual metrics, normalized such that pairs of real videos that differ only by physical randomness score 100%. All evaluated models show a large gap, with the best model scoring 24.1%, indicating that physical understanding is severely limited. Right. In addition, the mean rank of models across all four metrics is shown here; the Spearman correlation between aggregated results on the left and mean rank on the right is high (-.87,p<.005-.87p.005\text{-}.87,\emph{p}<.005- .87 , p < .005), thus aggregating to a single Physics-IQ score largely preserves model rankings.

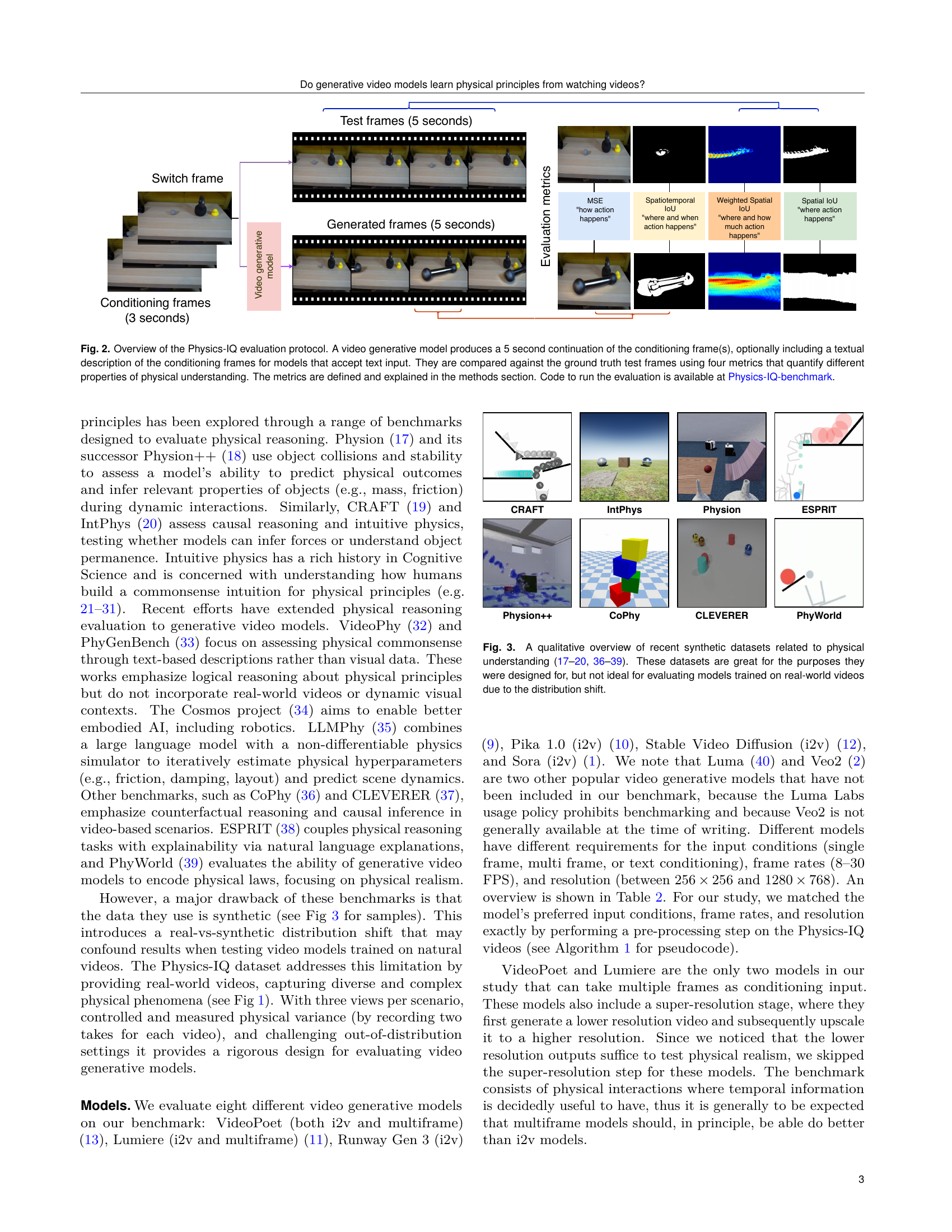

🔼 This figure investigates the relationship between visual realism and physical understanding in video generation models. The left panel shows the results of a two-alternative forced-choice experiment where a large language model (MLLM) distinguished between real and generated videos. Lower scores indicate higher visual realism, with Sora achieving the lowest score (best realism) and Lumiere (multiframe) the highest. The right panel displays a scatter plot examining the correlation between visual realism (MLLM score) and physical understanding (Physics-IQ score). The plot reveals a lack of correlation, suggesting that high visual realism does not necessarily imply strong physical understanding (Pearson’s r = -0.46, p = .247).

read the caption

Figure 5: Relationship between visual realism and physical understanding. Left. A multimodal large language model (Gemini 1.5 Pro) is asked to identify the generated video among the real and the generated video for each scenario (MLLM score) in a two-alternative forced choice paradigm. Chance rate is 50%; lower scores indicate that the model finds it harder to tell apart generated from real videos (= better realism). Sora-generated videos are hardest to distinguish from real videos for the model, whereas Lumiere (multiframe) is easiest. Right. Do models that produce ‘realistic-looking’ videos (as assessed by the MLLM score) also score better in terms of physical understanding (as assessed via the Physics-IQ score)? This scatterplot with linear fit and 95% confidence interval as a shaded blue area shows that this is not the case: Visual realism is uncorrelated with physical understanding (Pearson’s r = - 0.46, p=.247 not significant). Note that the y axis on this plot is inverted for easier interpretation (up & right are best).

🔼 Figure 6 presents a detailed comparison of eight different video generative models’ performance across various physical phenomena and evaluation metrics. The models are assessed on their ability to predict the continuation of short video clips depicting events governed by different physical principles (solid mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, thermodynamics, and magnetism). Four distinct metrics are used to evaluate the models: Spatial IoU (measuring the correctness of the location of actions), Spatiotemporal IoU (assessing both location and timing accuracy), Weighted Spatial IoU (considering both location and the amount of action), and MSE (measuring the pixel-level difference between the generated and real videos). Each metric’s results are displayed for each physical category and model, allowing for a comprehensive comparison of model performance. A dashed line indicates the ‘physical variance’, representing the performance limit imposed by inherent variability in real-world physical events. The figure demonstrates that while some models perform reasonably well on less stringent metrics like Spatial IoU, they struggle with more demanding metrics that require understanding not only where but also when and how much action takes place, highlighting a general lack of robust physical understanding in current video generative models.

read the caption

Figure 6: Performance comparison of video generative models across different physical categories (columns) and metrics (rows). For the top three metrics, higher is better; for the last metric lower values are best. Throughout, physical variance (i.e., the performance that is achievable by real videos differing only by physical randomness) is indicated by a dashed line. Across metrics and categories, models show a considerable lack in physical understanding. More lenient metrics like 𝖲𝗉𝖺𝗍𝗂𝖺𝗅-𝖨𝗈𝖴𝖲𝗉𝖺𝗍𝗂𝖺𝗅-𝖨𝗈𝖴\mathsf{Spatial}\text{-}\mathsf{IoU}sansserif_Spatial - sansserif_IoU (top row) that only assess where an action occurred lead to higher scores than more strict metrics that also take into account e.g. when or how much action should be taking place.

🔼 Figure 7 shows example successes and failures of two top-performing video generation models (VideoPoet and Runway Gen 3) on tasks requiring an understanding of fluid dynamics and solid mechanics. The figure demonstrates that while the models can accurately simulate some simple physics-based scenarios (e.g., smearing paint or pouring liquid), they struggle with more complex scenarios that involve interactions and precise movements (e.g., a ball falling into a crate or a knife cutting a tangerine). The examples highlight the limitations of current generative video models in realistically representing physical interactions.

read the caption

Figure 7: We here visualize success and failure scenarios within the fluid dynamics and solid mechanics categories for the two best models, VideoPoet and Runway Gen 3, according to our metrics. Both models are able to generate physics plausible frames for scenarios such as smearing paint on glass (VideoPoet) and pouring red liquid on a rubber duck (Runway Gen 3). At the same time, the models fail to simulate a ball falling into a crate or cutting a tangerine with a knife. See here for an animated version.

🔼 The figure shows the setup used to record videos for the Physics-IQ dataset. The top panel displays three Sony Alpha a6400 cameras mounted on tripods, positioned to capture three different perspectives (left, center, right) of the same scene. The bottom panel shows example images captured from each of these three perspectives, demonstrating the slightly varied viewpoints obtained.

read the caption

Figure 8: Illustration of recording setup (top) and perspectives (bottom).

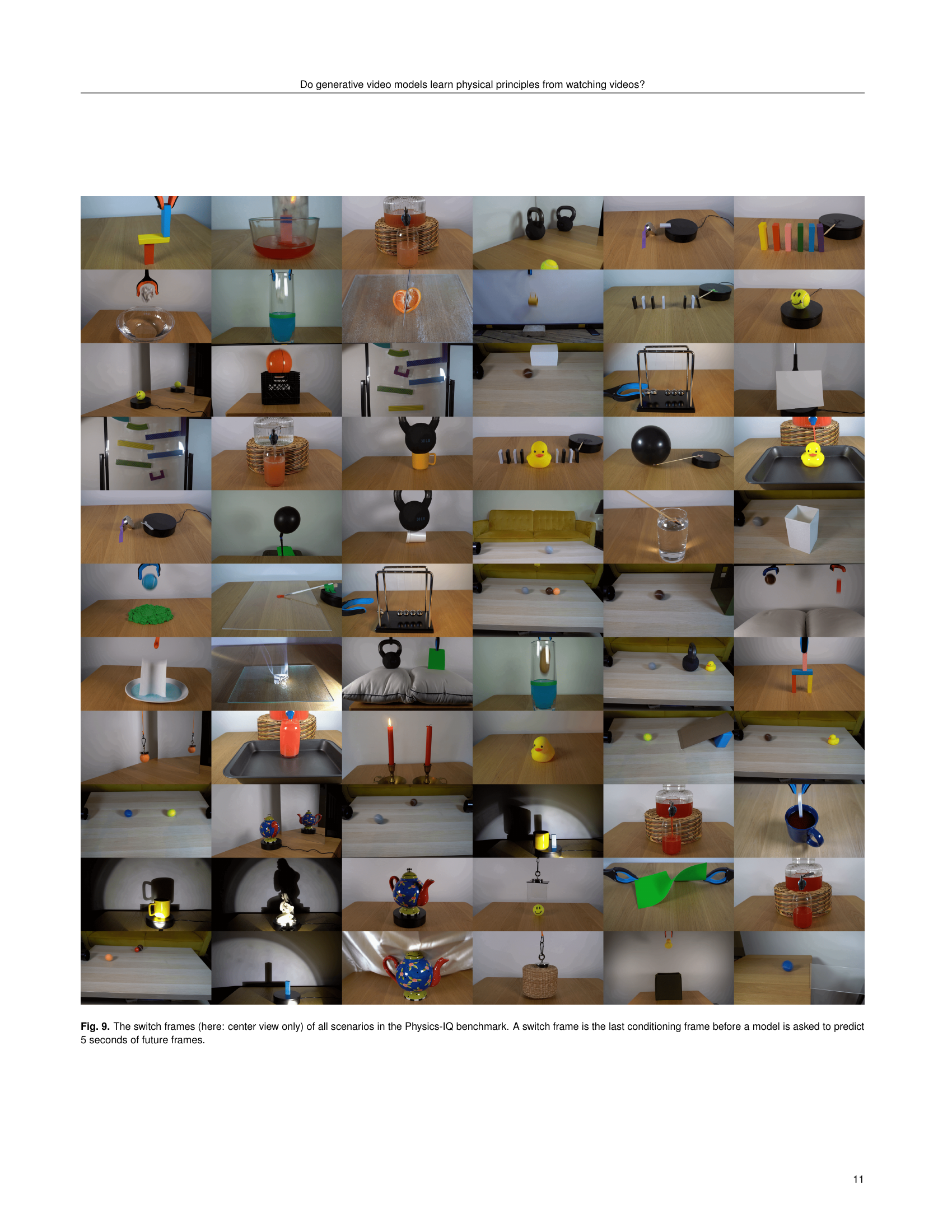

🔼 Figure 9 shows the ‘switch frames’ from the Physics-IQ benchmark dataset. Each image represents the final frame of a 3-second conditioning video shown to a generative video model. The model is then tasked with predicting the next 5 seconds of video based on this single frame. The figure provides a visual overview of all 66 scenarios included in the benchmark, allowing for a visual inspection of the diversity and complexity of physical phenomena represented.

read the caption

Figure 9: The switch frames (here: center view only) of all scenarios in the Physics-IQ benchmark. A switch frame is the last conditioning frame before a model is asked to predict 5 seconds of future frames.

🔼 Figure 10 demonstrates how different levels of mean squared error (MSE) affect image quality. MSE is a metric used to evaluate how close a generated image is to the ground truth image. The figure shows a series of images, all starting from a clear, original image of a puppy in a field. As the MSE value increases (MSE = 0.001, MSE = 0.005, MSE = 0.01, MSE = 0.02, MSE = 0.04), progressive distortions are added to the image. This visually demonstrates how higher MSE values correspond to greater noise and a blurring effect, ultimately resulting in a less clear and more distorted image. The figure provides a visual aid to help readers better understand what different MSE scores represent in terms of the visual quality of images and videos.

read the caption

Figure 10: Since mean squared error (MSE) values can be hard to interpret, this figure shows the effect of a distortion applied to the scene, serving as a rough intuition for the effect of a MSE at different noise levels.

Full paper#