TL;DR#

Current portrait relighting techniques often rely on Light Stage data, which is expensive and limited. Other methods struggle with generating realistic illumination effects and often fail to preserve the identity of the subject. This research addresses the limitations by using a novel approach. The core challenge was to bridge the gap between synthetic training data and real images. This paper proposes using a diffusion model and two training strategies: multi-task learning on synthetic and real data, and classifier-free guidance for fine-grained control during inference. This approach effectively preserves important image details while accurately capturing the effects of relighting.

The proposed method, SynthLight, demonstrates state-of-the-art results in relighting portraits. Quantitative results on a Light Stage dataset are comparable to other advanced methods. Qualitative results showcase high-quality illumination effects and excellent generalization to in-the-wild images. User studies confirm the superiority of SynthLight over other methods in terms of visual quality, lighting accuracy, and identity preservation. The researchers successfully demonstrate the capability of learning-based re-rendering for high-quality image manipulation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to portrait relighting using diffusion models and synthetic data. It addresses the limitations of existing methods that rely on expensive and limited Light Stage data or struggle with complex illumination effects. The proposed method offers high-quality results on real-world images and opens up new avenues for research in image editing and generation.

Visual Insights#

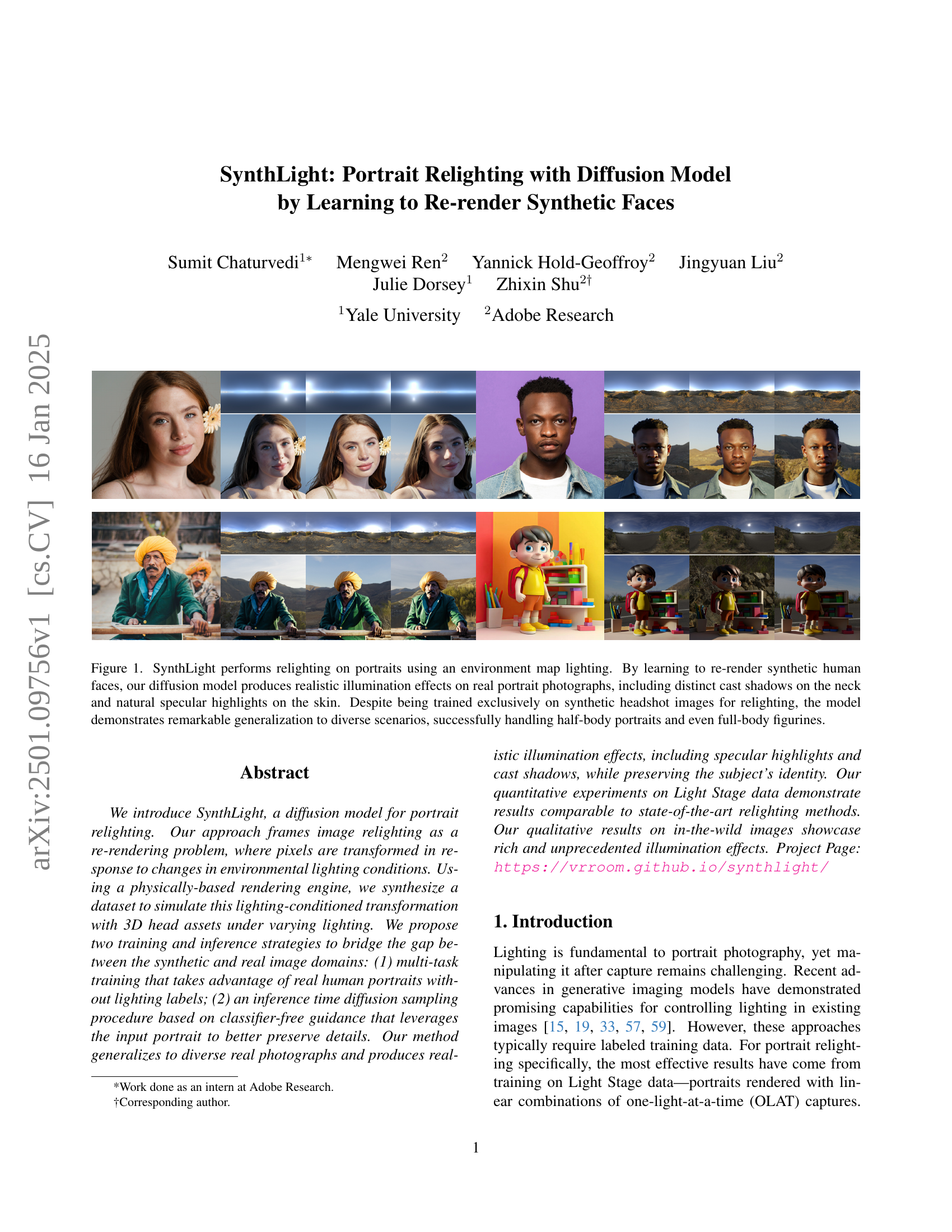

🔼 The figure showcases the capabilities of SynthLight, a diffusion model trained on synthetic human face headshots, to relight real portrait photographs realistically. SynthLight uses environment map lighting to produce illumination effects, including subtle cast shadows and specular highlights. Notably, it generalizes well beyond its training data, effectively relighting not only headshots, but also half-body and full-body images.

read the caption

Figure 1: SynthLight performs relighting on portraits using an environment map lighting. By learning to re-render synthetic human faces, our diffusion model produces realistic illumination effects on real portrait photographs, including distinct cast shadows on the neck and natural specular highlights on the skin. Despite being trained exclusively on synthetic headshot images for relighting, the model demonstrates remarkable generalization to diverse scenarios, successfully handling half-body portraits and even full-body figurines.

![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_11/col_00.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_11/col_03.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_11/col_06.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_11/col_09.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_10/col_00.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_10/col_02.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_10/col_05.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_results/teaser_row_10/col_08.jpg) |

![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_figures/extra_teaser_row_06/col_00.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_figures/extra_teaser_row_06/col_01.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_figures/extra_teaser_row_06/col_03.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/extra_figures/extra_teaser_row_06/col_09.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/teaser_figure/teaser_row_22/col_00.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/toy_figures_3/toy_figure_row_00/col_08.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/toy_figures_3/toy_figure_row_00/col_02.jpg) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](extracted/6136146/figures/toy_figures_3/toy_figure_row_00/col_09.jpg) |

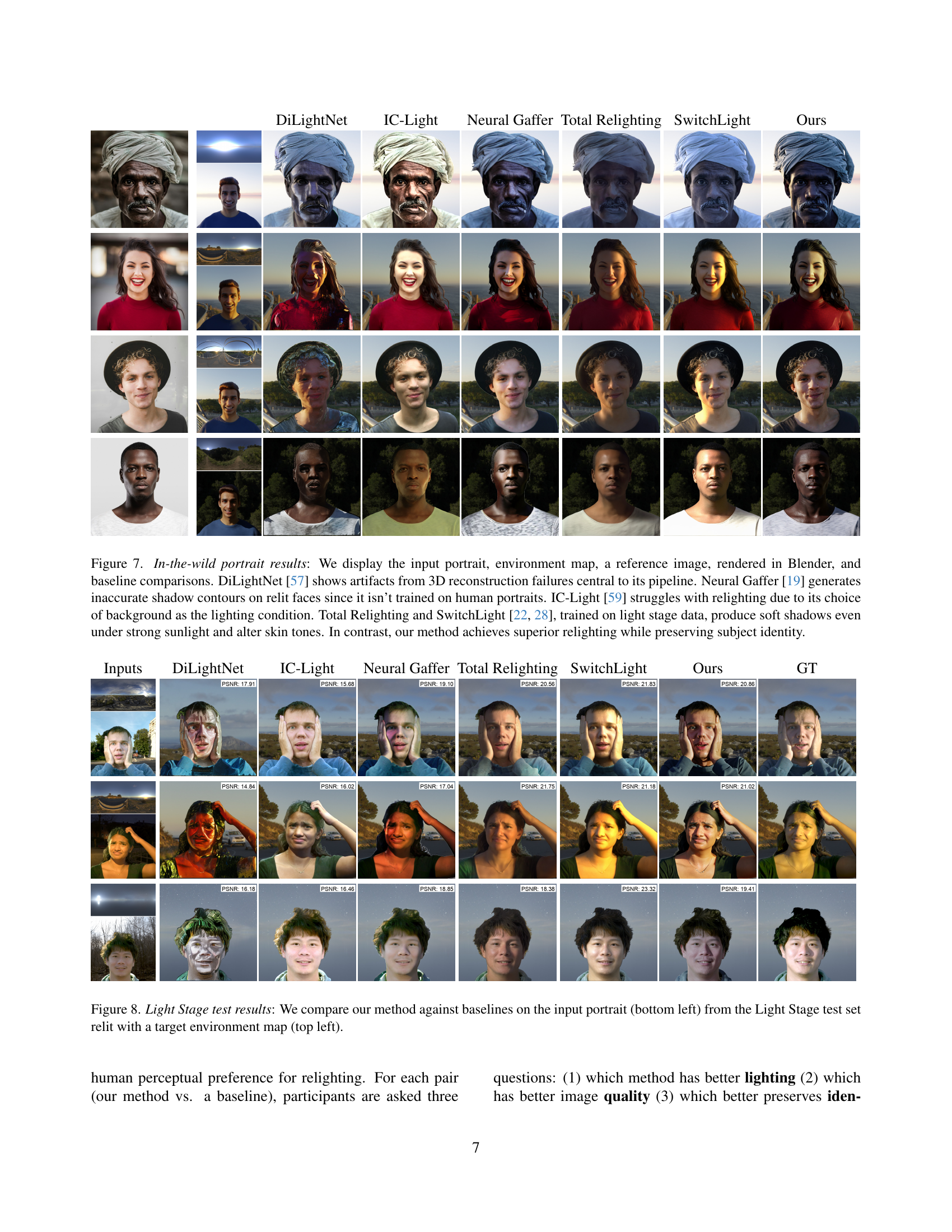

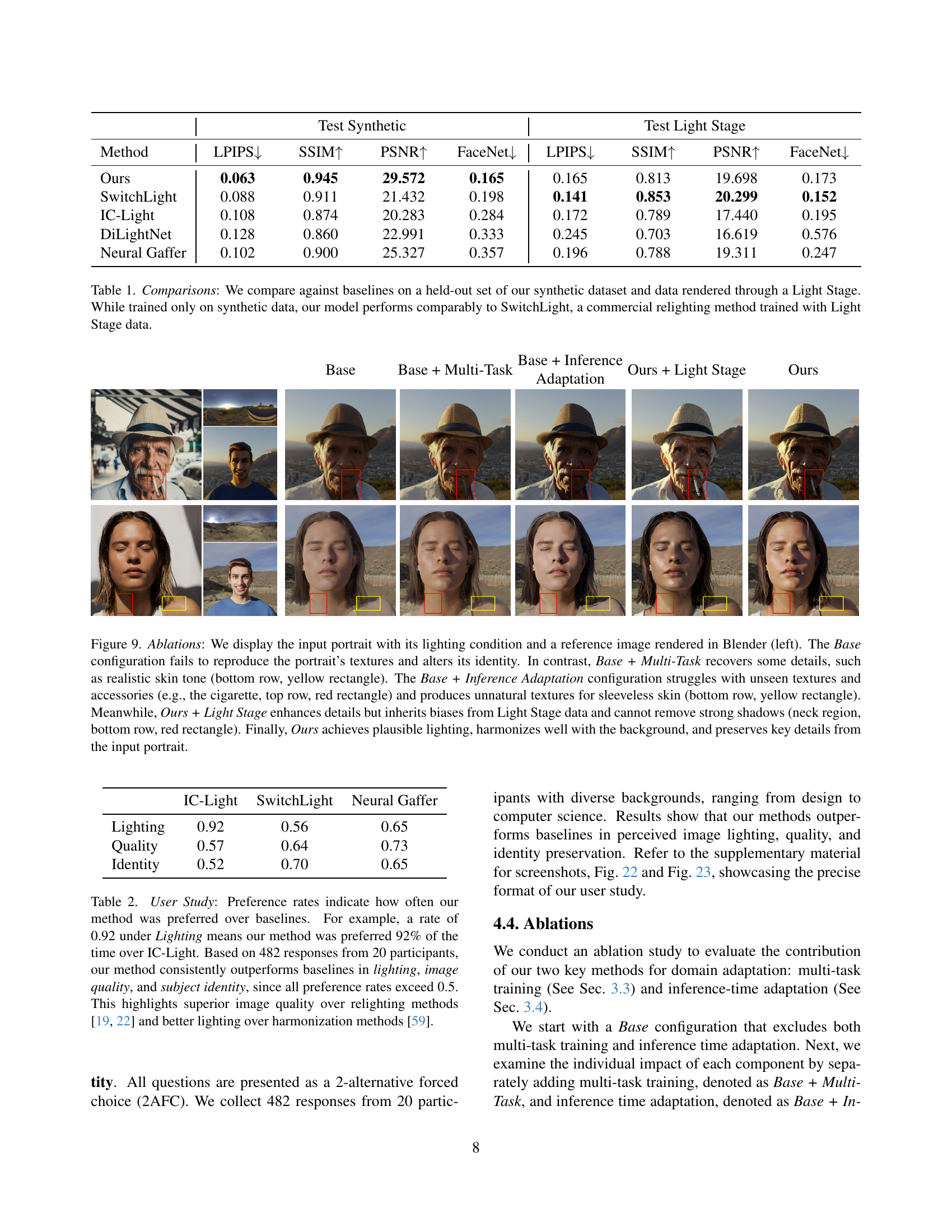

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed SynthLight model against several state-of-the-art baselines for portrait relighting. The comparison is performed using two distinct test sets: a held-out subset of the synthetic dataset used for training and a separate dataset of images rendered using a Light Stage. Performance is measured using standard image quality metrics (LPIPS, SSIM, PSNR) and a face-recognition metric (FaceNet), assessing both the image fidelity and preservation of identity. Remarkably, despite SynthLight being trained exclusively on synthetic data, its performance on both datasets is comparable to or better than that of SwitchLight, a commercially available relighting model trained on Light Stage data. This showcases the effectiveness of SynthLight in learning robust relighting capabilities from synthetic data.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparisons: We compare against baselines on a held-out set of our synthetic dataset and data rendered through a Light Stage. While trained only on synthetic data, our model performs comparably to SwitchLight, a commercial relighting method trained with Light Stage data.

In-depth insights#

Diffusion Model Relighting#

Diffusion models present a novel approach to image relighting, framing it as a re-rendering problem. Unlike traditional methods relying on inverse rendering or explicit scene decomposition, diffusion models learn a direct mapping between input images and lighting conditions to produce realistic relit outputs. This is achieved by training on synthetically generated data, leveraging physically-based rendering techniques to control lighting parameters. Domain adaptation strategies are crucial, bridging the gap between the synthetic training domain and real-world images. Multi-task learning and classifier-free guidance at inference time are effective strategies to achieve high-quality results while preserving image details and identity. The advantage of this approach lies in its ability to handle complex lighting effects, such as inter-reflections and subsurface scattering, which are often difficult for traditional methods to capture. However, challenges remain, particularly in accurately rendering fine details and complex textures present in real-world images, indicating that further research into domain adaptation and model architectures is warranted for improved performance.

Multi-task Training#

The heading ‘Multi-task Training’ suggests a sophisticated approach to training the diffusion model for portrait relighting. Instead of solely focusing on the relighting task using synthetic data, a multi-task learning strategy likely incorporates a second task, potentially a text-to-image generation task. This is crucial because training exclusively on synthetic data often leads to a domain gap, resulting in poor generalization to real-world images. The added task, using real-world images, helps the model learn essential features from the real image domain such as texture, color, and identity. By learning to generate realistic portraits from text prompts concurrently with the relighting task, the model better understands the complexities of human faces, minimizing distributional shifts and improving overall relighting quality. This combined training strategy effectively bridges the synthetic and real image domains, improving the model’s ability to transfer knowledge from the synthetic training data to realistic photographs, leading to more accurate and natural-looking relighting results. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to leverage the strengths of both synthetic and real data, overcoming the limitations of relying on only synthetic or real data alone.

Synthetic Data#

The utilization of synthetic data is a crucial aspect of this research, enabling the training of a diffusion model for portrait relighting without relying on scarce and expensive real-world datasets. The process involves rendering pairs of images with varied lighting conditions using a physically based rendering engine. This strategy allows for precise control over lighting parameters, which is difficult to achieve with real photographs. The synthetic dataset’s limitations are acknowledged, namely the lack of the diversity present in real-world images. To address this, techniques like multi-task training and classifier-free guidance are employed, bridging the gap between synthetic and real domains. Multi-task learning leverages real images alongside synthetic ones to improve generalization. Classifier-free guidance, used during inference, helps to preserve details in the real input image during the relighting process. The combination of these approaches is key to achieving realistic relighting effects on real-world portraits, despite training primarily on a synthetic dataset. Future work could explore even richer synthetic datasets, incorporating more complex scenes and textures to further enhance the model’s accuracy and adaptability.

Domain Adaptation#

The section on domain adaptation tackles the critical challenge of bridging the gap between synthetic training data and real-world images. Synthetic data, while offering control and scalability, often suffers from a domain mismatch, leading to poor generalization on real images. The authors cleverly address this by employing a multi-task training strategy. This approach leverages a pre-trained text-to-image diffusion model, combining synthetic portrait relighting data with real images from the internet, mitigating the distributional shift. Furthermore, an inference-time adaptation technique, based on classifier-free guidance, further refines the output by preserving crucial details from the input real portrait. This two-pronged approach, combining training and inference time adjustments, showcases a sophisticated understanding of domain adaptation challenges and offers a practical, effective solution to the problem of realistic portrait relighting using only synthetic training data.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for SynthLight could explore several key areas. Improving the realism of synthetic data is crucial; incorporating more diverse head meshes, clothing styles, and accessories, along with higher-resolution textures and physically-based rendering techniques that capture finer details like subsurface scattering and complex lighting interactions, would significantly enhance the model’s generalization capabilities. Addressing the limitations of the current diffusion model is another priority. Investigating alternative architectures or training strategies could improve upon the model’s ability to preserve fine details in real-world portraits while achieving high-fidelity relighting. Exploring methods to handle unseen occluders and complex lighting scenarios, such as those found in outdoor scenes, would make the system more robust. Finally, developing a user-friendly interface with intuitive controls for lighting adjustments would broaden its appeal and usability. The incorporation of real-time feedback mechanisms to aid users in making accurate and effective lighting choices will allow it to be better accepted and used.

More visual insights#

More on figures

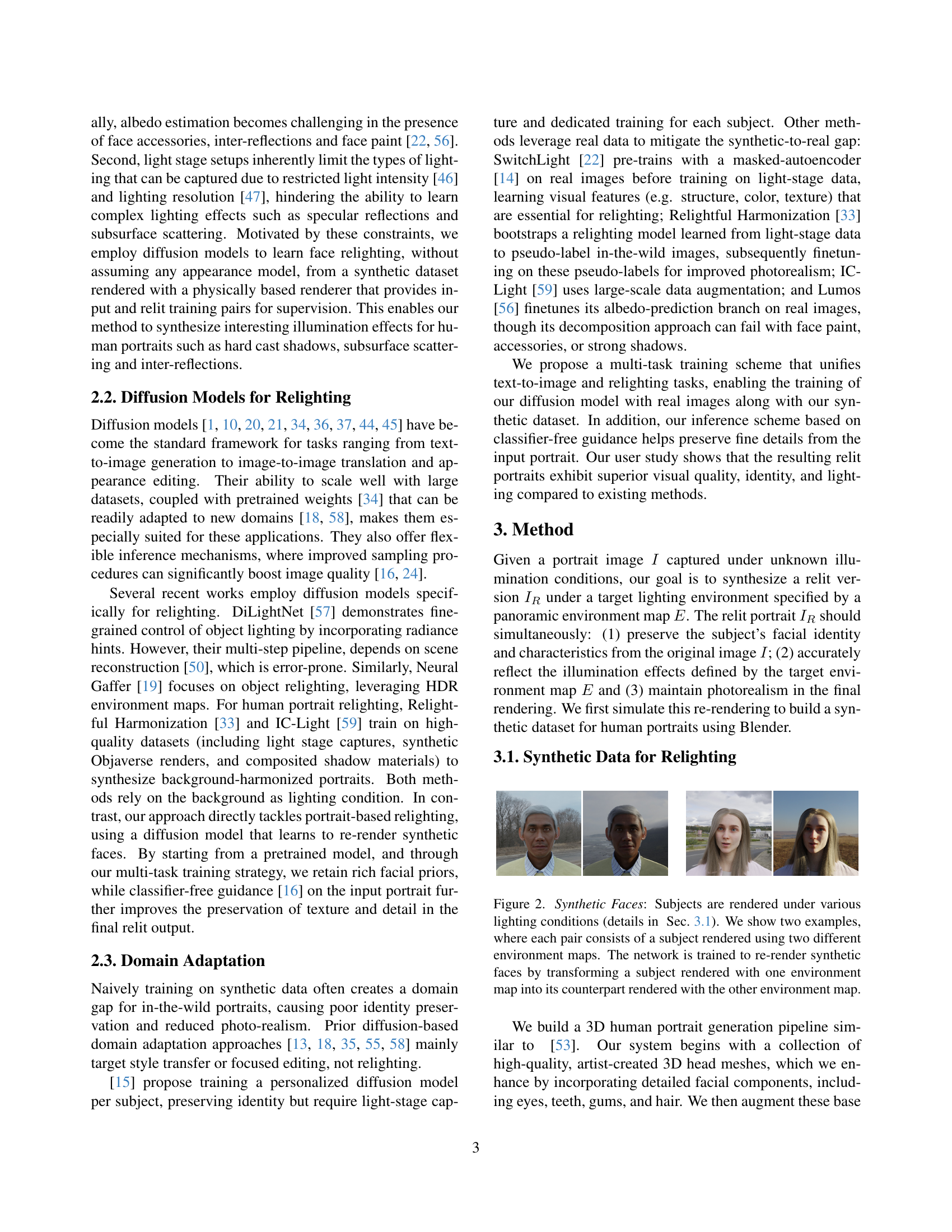

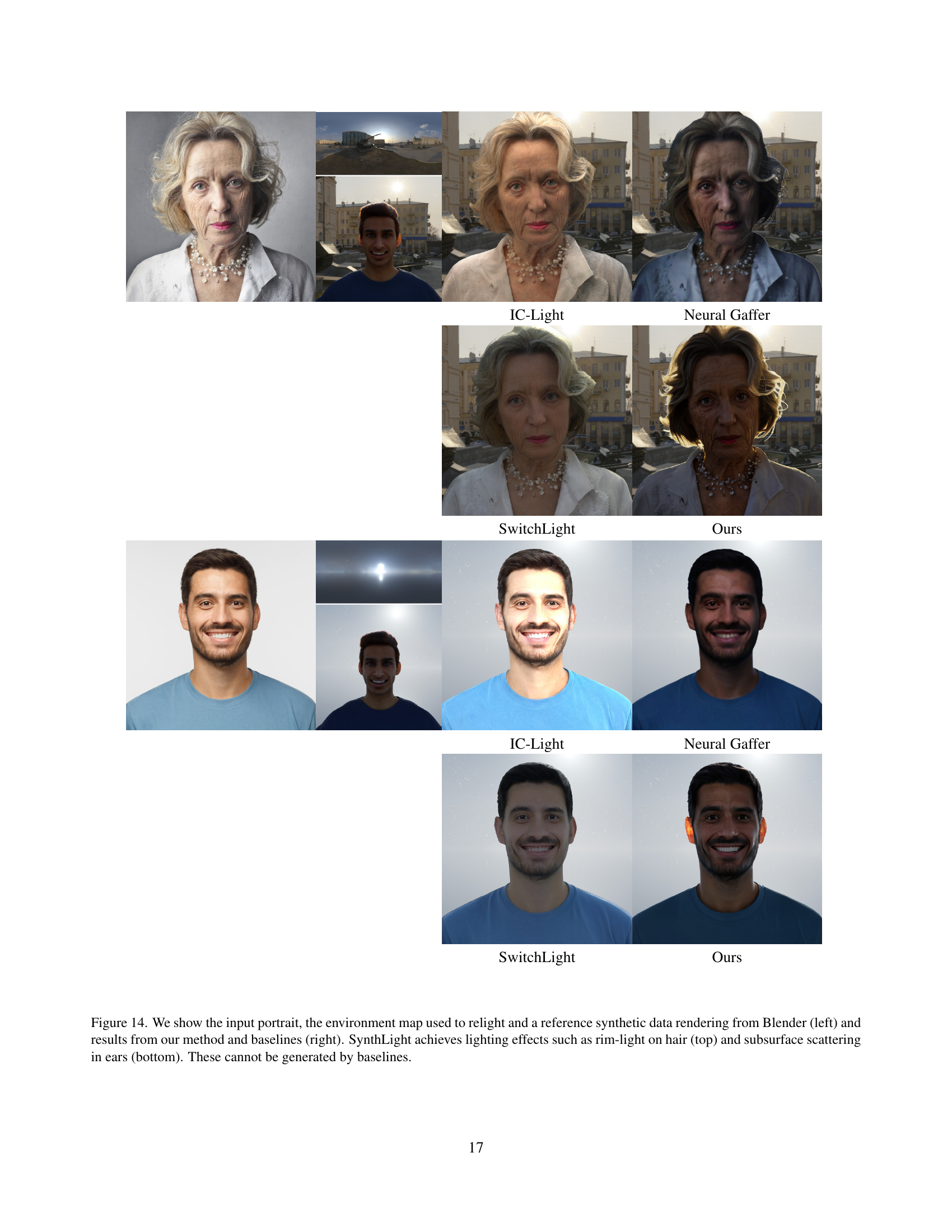

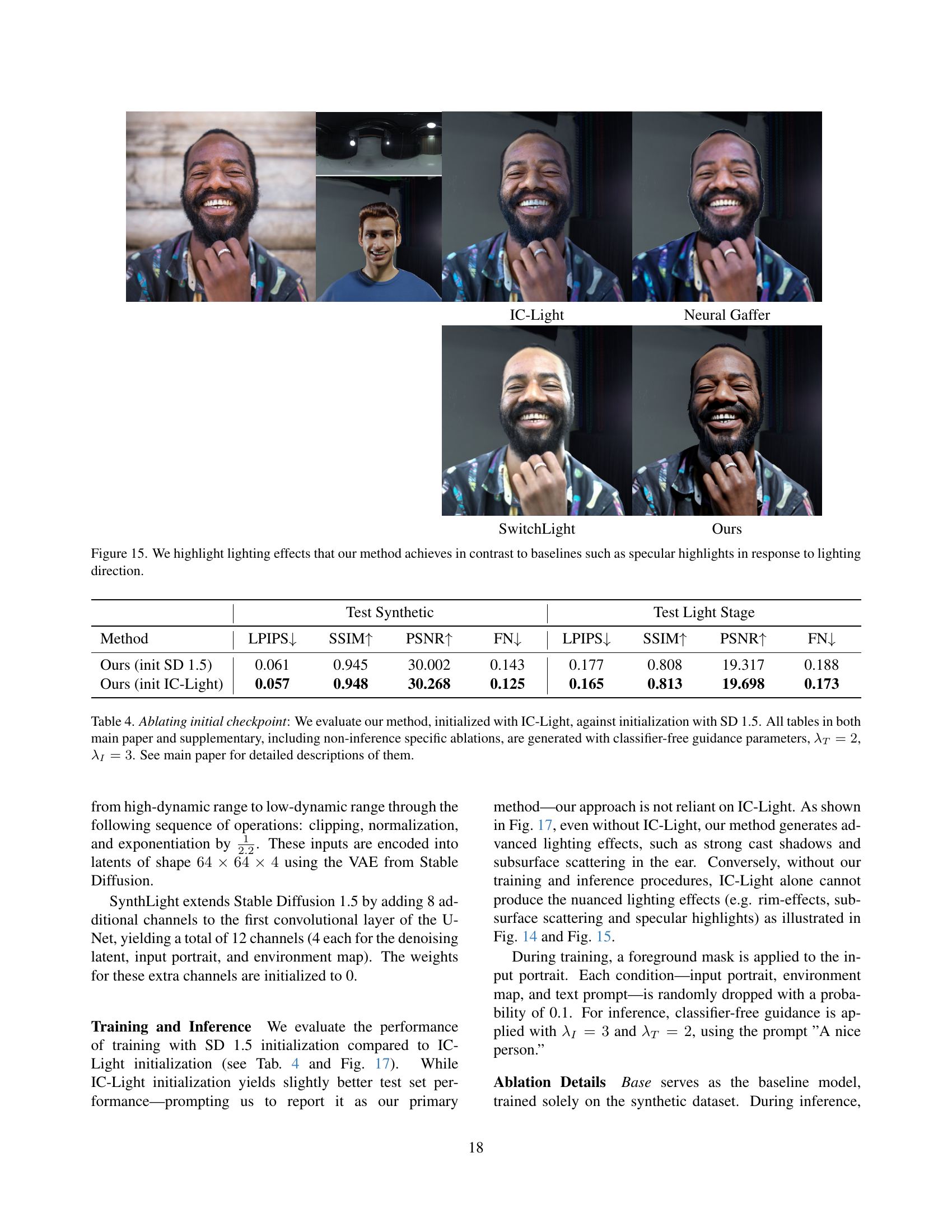

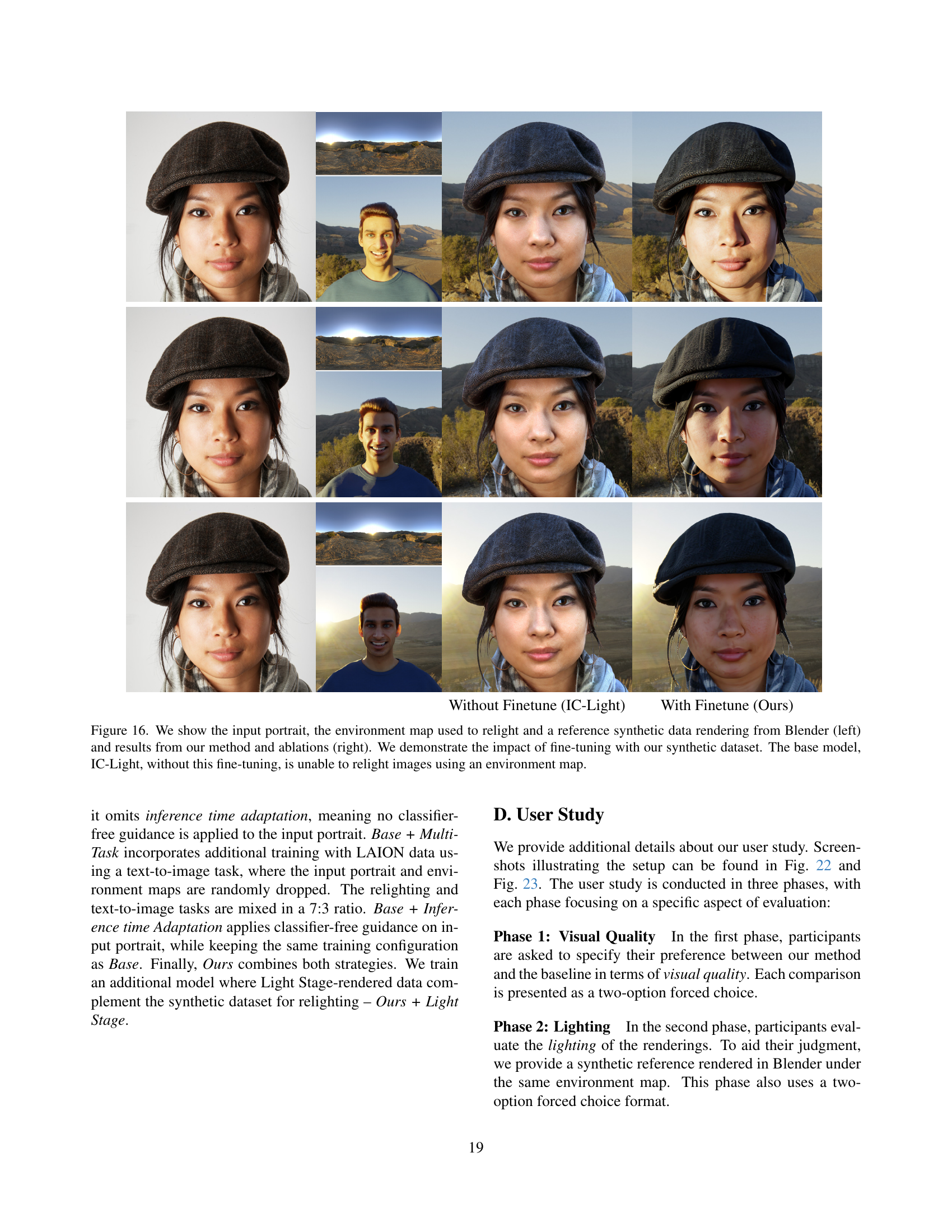

🔼 This figure shows pairs of synthetic human faces rendered under different lighting conditions. Each pair shows the same 3D face model illuminated by two different environment maps (HDR). The goal is to train a neural network to transform an image of a face rendered under one lighting condition to its counterpart image rendered under another lighting condition. This demonstrates how the model learns to re-render faces under varying lighting scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 2: Synthetic Faces: Subjects are rendered under various lighting conditions (details in Sec. 3.1). We show two examples, where each pair consists of a subject rendered using two different environment maps. The network is trained to re-render synthetic faces by transforming a subject rendered with one environment map into its counterpart rendered with the other environment map.

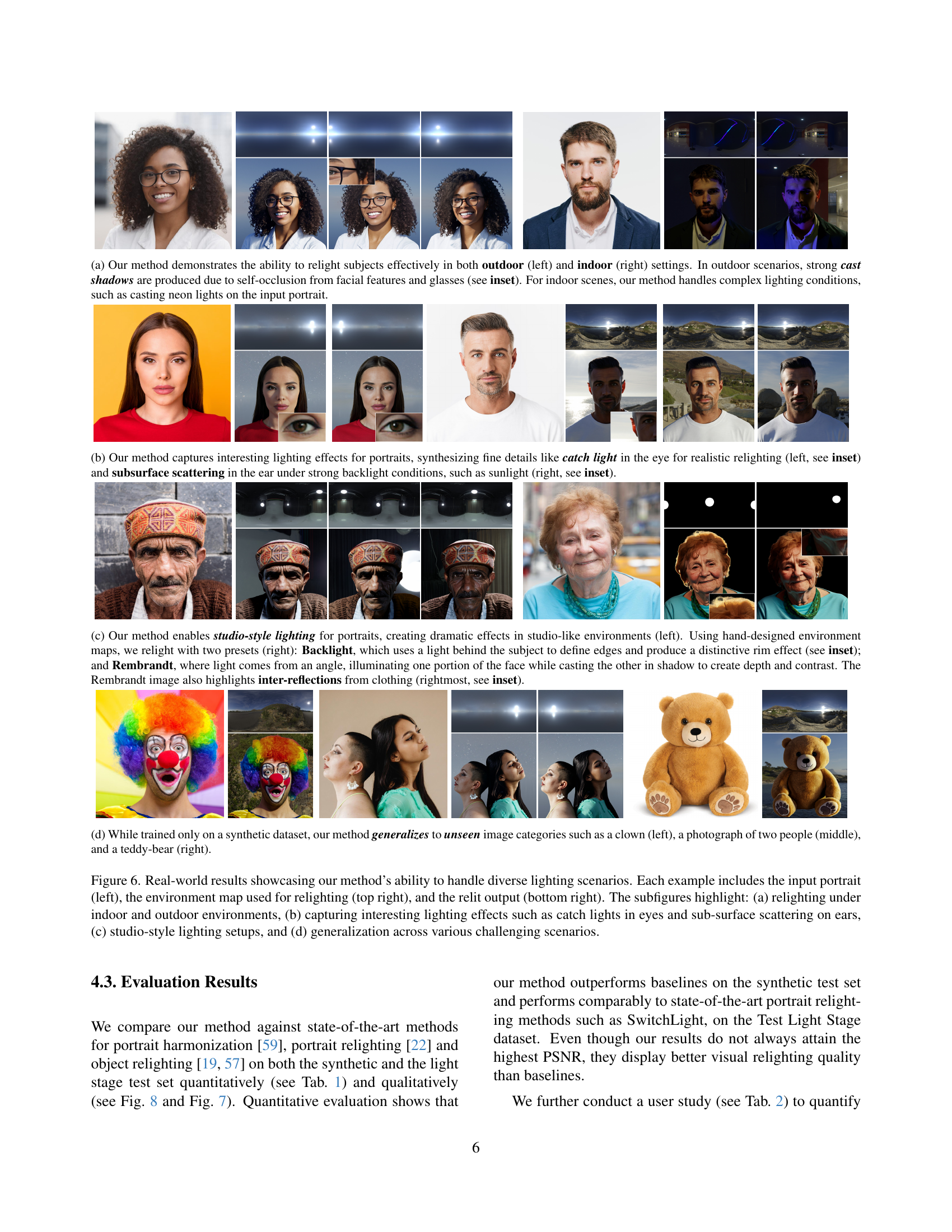

🔼 This figure illustrates the training pipeline of the SynthLight model. The pipeline uses a multi-task learning approach, combining synthetic relighting data (Task 1) with real-world text-to-image data (Task 2). Task 1 trains the model on synthetically generated portrait images, rendered under different lighting conditions, to learn to relight images. Task 2 uses real-world image data to minimize the domain gap between synthetic training data and real images and improve photorealism. The model is based on Latent Diffusion Models (LDM), comprising a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) and a U-Net. For clarity, the VAE is omitted from the diagram.

read the caption

Figure 3: Training pipeline of SynthLight. We first enable the relighting modeling by training the diffusion backbone with synthetic relighting tuples (Task 1, top row), detailed in Sec. 3.2. To further alleviate the domain gap between synthetic and real image domain, we include a joint training of the text-to-image task (Task 2, bottom row), detailed in Sec. 3.3. Our model is based on LDM [34] and is composed of a VAE and a UNet. For simplicity, VAE is omitted in the diagram.

🔼 This figure illustrates the inference-time adaptation method used in SynthLight. It shows how classifier-free guidance is used to balance identity preservation and relighting effects. The method proportionally adjusts the contribution of image-conditional and unconditional scores during the diffusion process, allowing for control over how strongly the input image’s details are preserved while incorporating the desired relighting effects specified by the environment map. The equation (Eq. 2) that is referenced shows the mathematical formula used to compute the balanced score.

read the caption

Figure 4: We employ the image-conditioning classifier-free guidance during inference to proportionally balance between identity preservation, and relighting effects. The final score estimate is computed as per Eq. 2.

More on tables

|  |  |  |

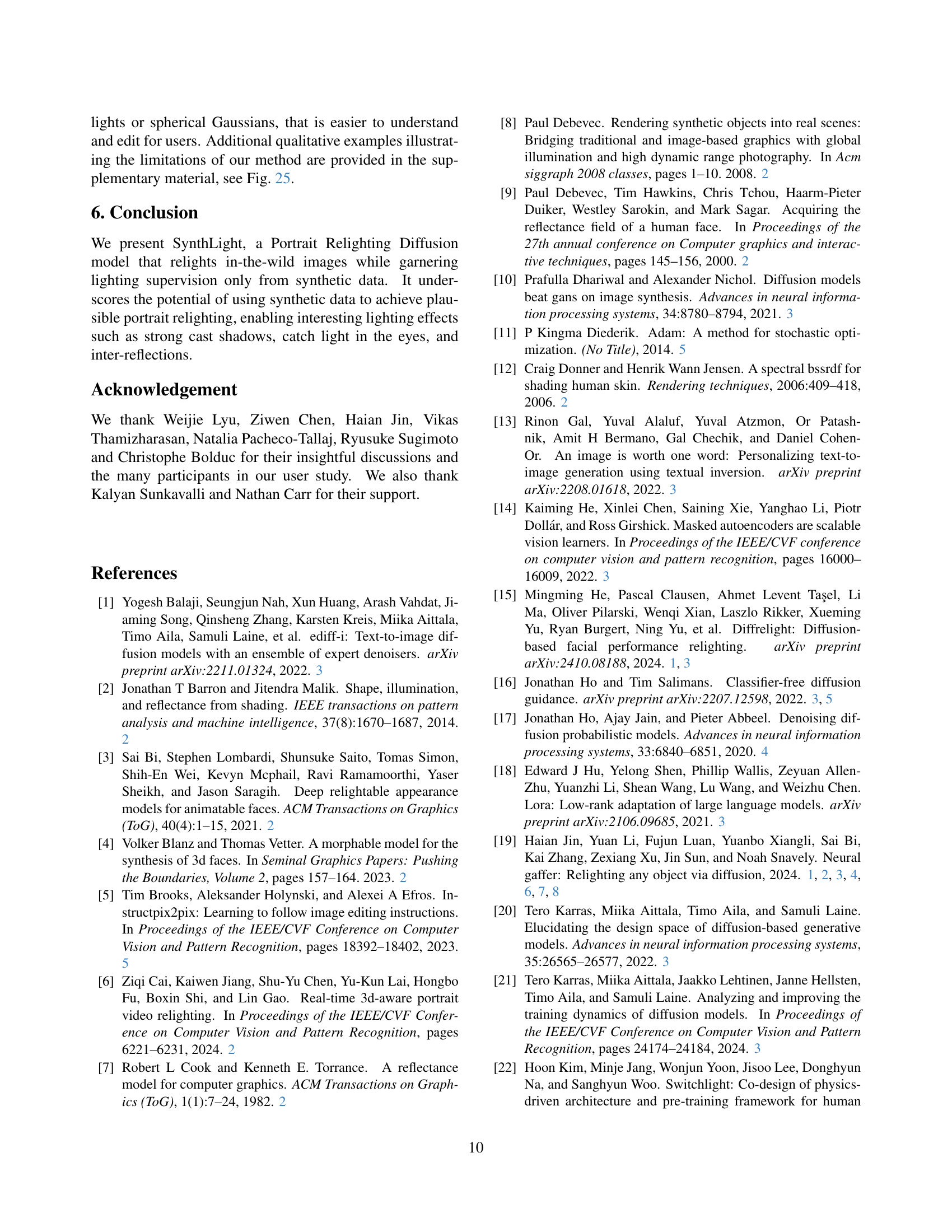

🔼 This table presents the results of a user study comparing SynthLight’s performance against other state-of-the-art methods for portrait relighting. Twenty participants provided 482 responses in total. Each comparison used a pairwise forced-choice format, asking participants to indicate which method (SynthLight or a baseline) they preferred based on specific criteria: lighting, overall image quality, and preservation of subject identity. The results show that SynthLight consistently outperforms baselines across all three criteria, achieving preference rates above 50% in each case. This indicates that SynthLight produces superior image quality compared to relighting methods ([22], [19]), and better lighting compared to harmonization methods ([59]).

read the caption

Table 2: User Study: Preference rates indicate how often our method was preferred over baselines. For example, a rate of 0.92 under Lighting means our method was preferred 92% of the time over IC-Light. Based on 482 responses from 20 participants, our method consistently outperforms baselines in lighting, image quality, and subject identity, since all preference rates exceed 0.5. This highlights superior image quality over relighting methods [22, 19] and better lighting over harmonization methods [59].

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

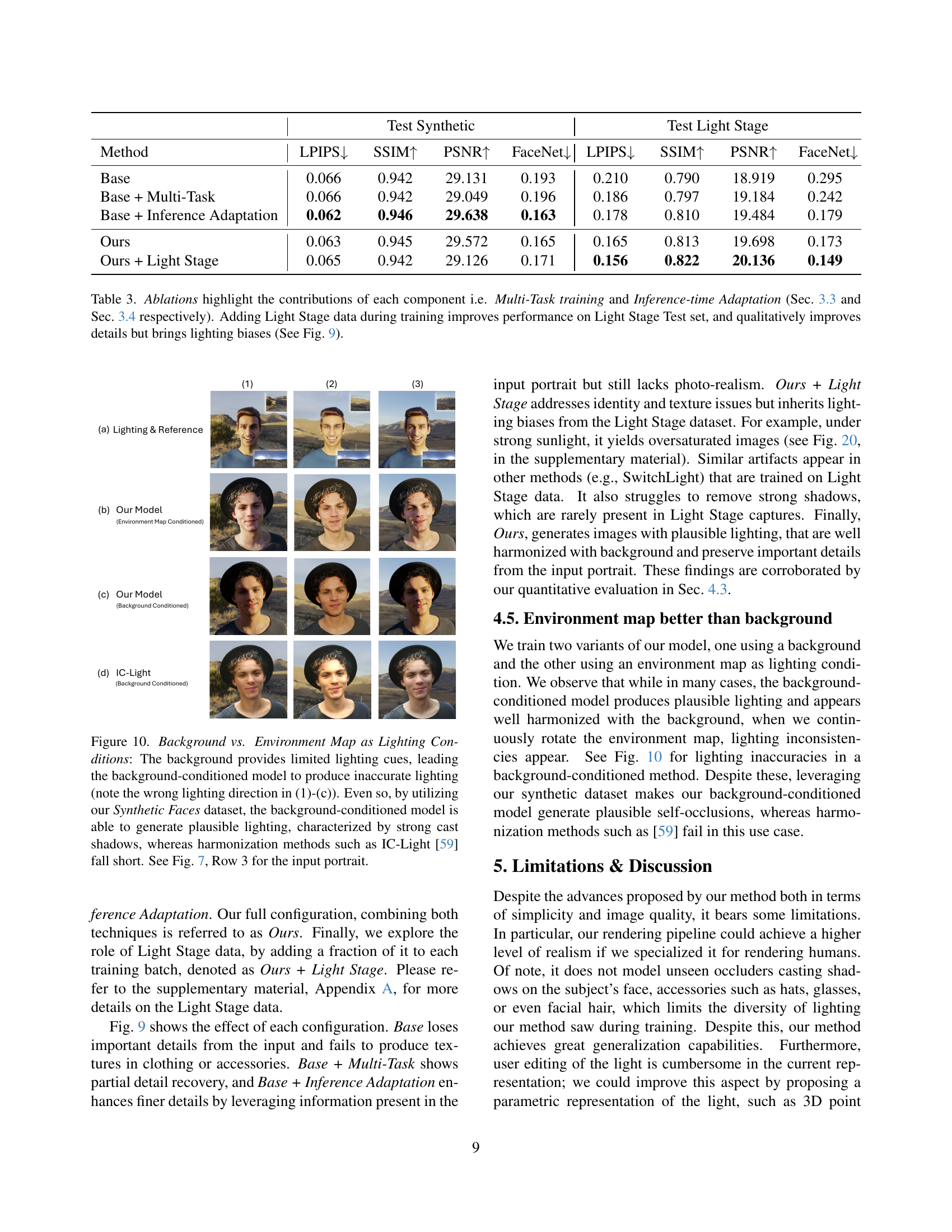

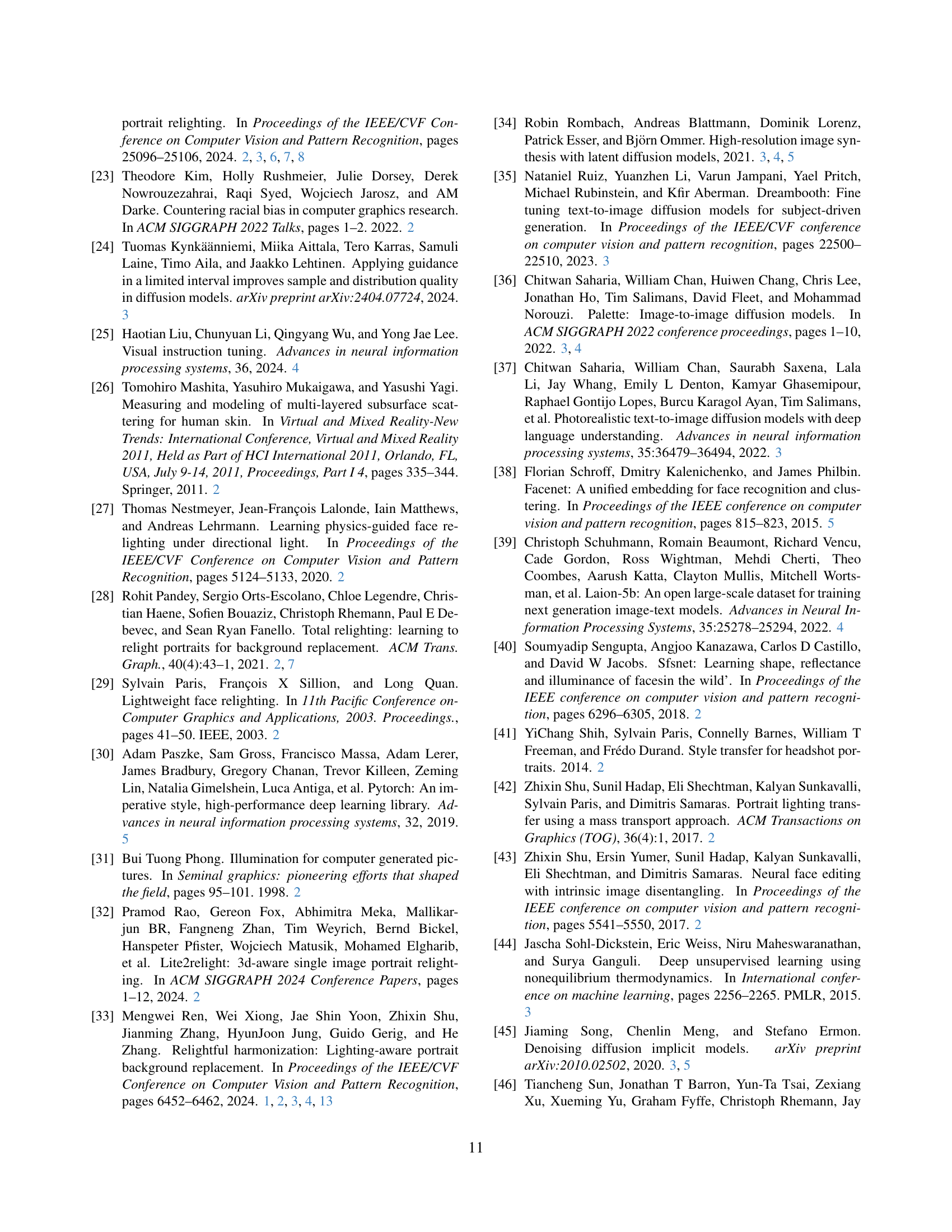

🔼 This table presents an ablation study evaluating the impact of different components on the SynthLight model’s performance. The study compares several model variations: a base model without any additional training strategies or inference-time adaptations; a model incorporating multi-task training (combining relighting and text-to-image tasks); a model with inference-time adaptation (using classifier-free guidance); the full SynthLight model incorporating both multi-task training and inference-time adaptation; and finally, a model trained with both synthetic and Light Stage data. The results are assessed using both quantitative metrics (LPIPS, SSIM, PSNR, and FaceNet) on synthetic and Light Stage test datasets and qualitative observations regarding the level of detail and lighting accuracy. The results show that the addition of Light Stage data improves quantitative results on the Light Stage dataset but can introduce lighting biases (as shown in Figure 9 in the paper).

read the caption

Table 3: Ablations highlight the contributions of each component i.e. Multi-Task training and Inference-time Adaptation (Sec. 3.3 and Sec. 3.4 respectively). Adding Light Stage data during training improves performance on Light Stage Test set, and qualitatively improves details but brings lighting biases (See Fig. 9).

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

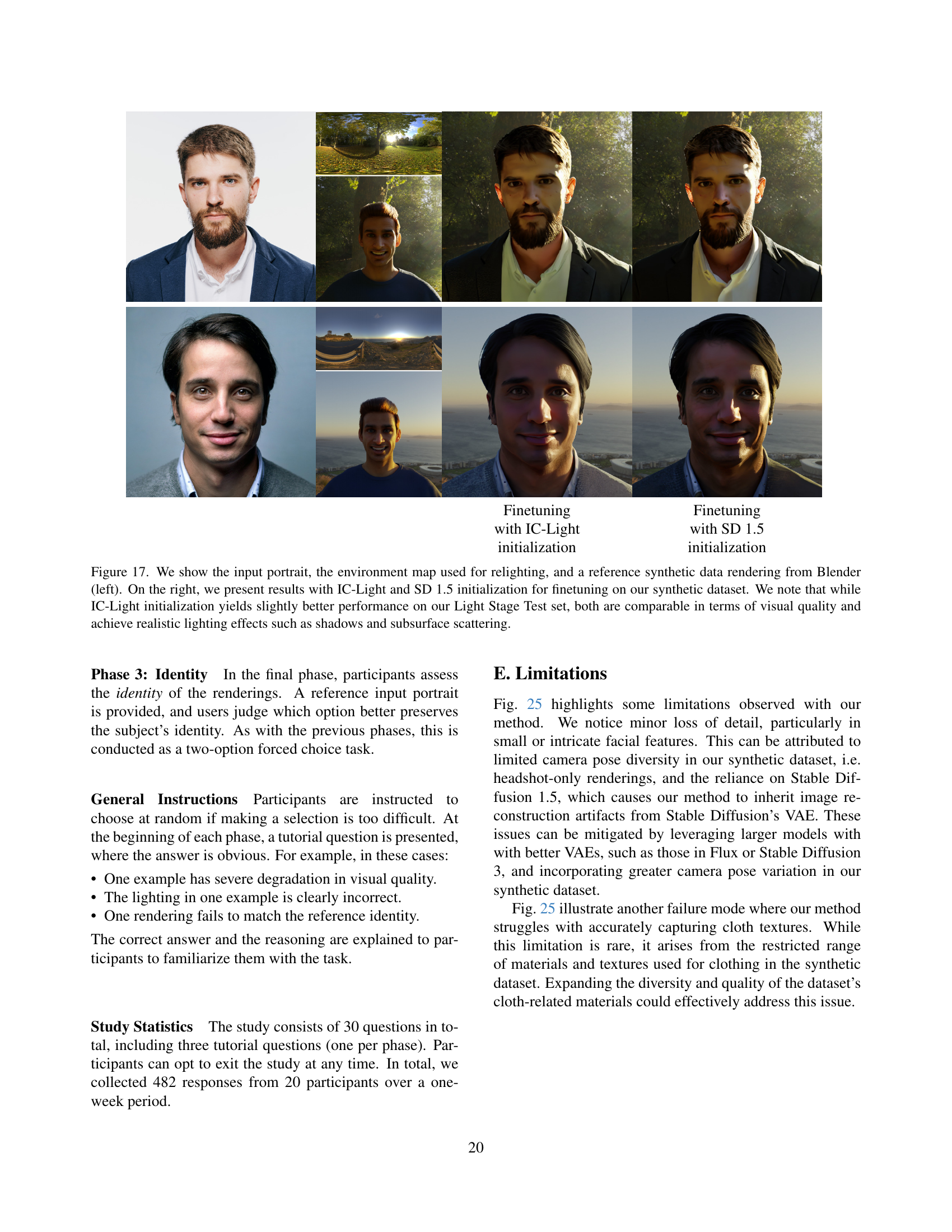

🔼 This table compares the performance of the SynthLight model when initialized with two different pre-trained models: IC-Light and Stable Diffusion 1.5. The comparison focuses on the results obtained from both synthetic and Light Stage test datasets. The metrics used include LPIPS (lower is better), SSIM (higher is better), PSNR (higher is better), and FaceNet (lower is better). The experiment uses classifier-free guidance with parameters λT=2 and λI=3 during both training and inference. The results show that while initializing with IC-Light provides slightly better performance, both initializations lead to good overall results, demonstrating the model’s robustness.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablating initial checkpoint: We evaluate our method, initialized with IC-Light, against initialization with SD 1.5. All tables in both main paper and supplementary, including non-inference specific ablations, are generated with classifier-free guidance parameters, λT=2subscript𝜆𝑇2\lambda_{T}=2italic_λ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 2, λI=3subscript𝜆𝐼3\lambda_{I}=3italic_λ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_I end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 3. See main paper for detailed descriptions of them.

Full paper#