TL;DR#

The paper “Evolution and The Knightian Blindspot of Machine Learning” identifies a critical limitation in current machine learning (ML) methods: a lack of robustness to unforeseen events. It argues that ML heavily relies on quantifiable uncertainties, neglecting the ‘unknown unknowns’ or Knightian Uncertainty (KU), which are inherently unpredictable. This is highlighted by contrasting the relative fragility of reinforcement learning (RL) with the impressive robustness of biological evolution, which routinely produces agents capable of thriving in open-world, ever-changing environments. The paper emphasizes the need for ML to address this blind spot to create truly robust AI.

The researchers suggest that existing ML approaches, like meta-learning and continual learning, do not fully address KU, as they often make assumptions that implicitly rule out the unknowable. They propose exploring alternative paradigms such as artificial life and open-endedness, which may offer novel mechanisms to build robustness to KU. Re-examining RL’s core formalisms is also advocated for, to allow for a deeper engagement with KU. The paper’s main contribution is to highlight this critical limitation of ML and suggest potential solutions, potentially leading to a paradigm shift in how robustness and general intelligence are approached in AI.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers because it highlights a critical blind spot in current machine learning (ML) approaches: the lack of robustness to unknown unknowns. It challenges the field to reconsider its core formalisms and explore alternative strategies informed by the robustness of biological evolution. This opens new avenues for research in AI safety, artificial life, and open-endedness, ultimately leading to more robust and reliable AI systems.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates four key mechanisms contributing to evolution’s robustness against Knightian Uncertainty (KU), which is the inability to quantify unknown future events. (a) depicts an open-ended search space allowing for a wide variety of complex adaptations. (b) shows how diversification pressure leads to diverse evolutionary strategies, each a bet on survival. (c) illustrates that novel adaptations create new environmental challenges, testing organisms’ robustness. Finally, (d) shows that only successful lineages persist, discarding unsuccessful ‘bets’. These four factors interact to generate and evaluate hypotheses about handling KU, mirroring scientific inquiry’s falsifiability.

read the caption

Figure 1. Interlocking principles enabling evolution’s robustness to Knightian Uncertainty. (a) Evolution happens within a search space that is open-ended enough such that a vast array of complex adaptations can be encoded, e.g. the human brain, multicellularity, developmental systems as a whole, and photosynthesis. (b) Diversification pressure in evolution continually creates new behaviors and adaptations from the set of open-ended possibilities, which implicitly can be seen as bets about how the organism and its lineage can persist into the future. (c) Because organisms form part of the environment of other organisms, novel behaviors and adaptations in one lineage create novel unforeseen situations for other organisms as an externality, e.g. the high branches of a tree provide a novel situation a giraffe can exploit. (d) Organisms unable to persist across the uncertainty created by other organisms are filtered away, in effect invalidating their bets about how to persist through KU; the image shows a coelacanth, a fish that has persisted for 400 million years. In concert, these factors can be seen as a form of open-ended generation and falsification of bets about how to deal with KU. We believe there may be ways to adapt these principles to ML research (see discussion in Section 5).

| Knowns | Unknowns | |

|---|---|---|

| Known | Deterministic (Known Knowns) | Risk (Known Unknowns) |

| Unknown | Implicit Knowledge (Unknown Knowns) | Knightian Uncertainty (Unknown Unknowns) |

🔼 This table categorizes different types of uncertainty, from deterministic scenarios with complete information (known knowns) to those with unknown unknowns (Knightian uncertainty). It highlights the increasing complexity of optimization as uncertainty increases. While machine learning excels in handling known unknowns (risk), it struggles with situations involving unknown unknowns, which is the main focus of this paper. The category of ‘unknown knowns’ (implicit knowledge) is mentioned but deemed less relevant to the paper’s central argument.

read the caption

Table 1. Types of Risk and Uncertainty. Optimization is most straightforward in deterministic settings with complete information, and more challenging in situations of risk, where there are unknowns, but their parameters are known or estimable. More challenging still are situations where there exist unknown unknowns, i.e. future possibilities that are qualitatively novel and difficult or impossible to anticipate (though they may seem obvious in hindsight) – the central topic of this paper. The fourth quadrant of unknown knowns (e.g. where an agent or system has implicit knowledge that is not explicitly known) is also important but less relevant to arguments here. In short, machine learning excels at situations of determinism or risk, but struggles to model Knightian uncertainty.

In-depth insights#

Knightian Uncertainty#

Knightian Uncertainty (KU), as discussed in the research paper, centers on the challenge of making decisions under conditions of qualitatively unknown unknowns. Unlike traditional risk assessment, which quantifies probabilities of known possibilities, KU acknowledges the existence of unforeseen events that defy quantification. The paper highlights that machine learning (ML), particularly reinforcement learning (RL), often overlooks KU by operating under simplifying assumptions of closed, predictable environments. The focus on known unknowns, or risks that can be statistically modeled, leaves ML vulnerable to unforeseen changes in the open world. The authors argue that a lack of engagement with KU contributes to the fragility of current ML systems and propose that incorporating KU-aware strategies, inspired by biological evolution’s robustness to novel situations, is crucial for developing truly intelligent and robust AI. The paper stresses the importance of embracing open-endedness and abandoning the rigid formalism of current ML approaches to better navigate this fundamental challenge of the unknown.

Evolution’s Robustness#

The paper delves into the remarkable robustness of biological evolution, contrasting it with the relative fragility of current machine learning (ML) systems. Evolution’s success stems from its open-ended and opportunistic nature, continually generating diverse strategies for survival and adaptation without relying on explicit formalisms. This contrasts sharply with the closed-world assumptions of typical ML models. Evolution’s success relies on a continuous cycle of diversification and filtering, where novel situations expose weaknesses and drive selection for more robust designs. The absence of a pre-defined objective, combined with the immense computational power of nature, allows evolution to explore a vast search space and find unexpected, highly effective solutions. This contrasts with ML’s reliance on pre-defined objectives and narrowly tailored solutions, often failing in open-world scenarios where novel or unforeseen events arise. The paper highlights the need for ML to adopt more evolutionary principles, emphasizing exploration, diversity, and the ability to adapt to qualitative changes, to achieve true open-world robustness. A key takeaway is to shift away from a solely optimization-focused paradigm to one that prioritizes open-endedness and continual adaptation, moving closer to evolution’s principles.

RL’s Time Blindness#

The section ‘RL’s Time Blindness’ critiques reinforcement learning’s (RL) limited handling of time, crucial for managing Knightian uncertainty (KU). RL often treats time as discrete episodes, assuming stationary environments and fixed training distributions, ignoring how real-world conditions change continually. The discount factor in standard RL objectives further limits the algorithm’s sensitivity to long-term consequences. RL’s time horizons are often short, prioritizing immediate rewards over potential long-term risks. Unlike biological evolution, which naturally manages temporal dependencies across generations, RL often processes data devoid of its temporal context. This time-blindness prevents RL from fully grasping the dynamic nature of open-world problems, and hence it limits its robustness in the face of unexpected events. The inability to learn from past mistakes across different phases of learning or to appropriately weigh short-term gains against long-term risks is highlighted as a core shortcoming. The authors suggest this time-blindness stems from foundational assumptions inherent in the formalism of RL, which they argue, obstructs a proper engagement with the complexities of KU.

Open-Endedness Promise#

The promise of open-endedness in addressing the Knightian blind spot of machine learning lies in its capacity to generate novelty continuously. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that operate within predefined frameworks and assumptions, open-endedness embraces an unconstrained search space, mirroring the dynamic nature of real-world environments. This allows for the discovery of solutions that are not only robust but also adaptable to unforeseen circumstances. By mimicking biological evolution’s capacity for open-ended exploration and diversification, open-ended systems may develop strategies to manage unknown unknowns, a key aspect of general intelligence that is currently lacking in most AI formalisms. This approach suggests that algorithmic advancements might be less important than the creation of scalable systems that foster ongoing adaptation and creativity to genuinely manage the uncertainties inherent in real-world complexity.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize bridging the gap between theoretical frameworks and practical applications. Addressing Knightian uncertainty (KU) requires moving beyond closed-world assumptions and developing algorithms robust to qualitatively novel, unforeseen situations. This necessitates a paradigm shift, potentially incorporating elements from biological evolution such as open-endedness and continual diversification. Investigating the use of artificial life (ALife) and open-endedness approaches offers promising avenues. Revising core RL formalisms to explicitly incorporate time’s continuous flow and the interconnectedness of events is crucial. Furthermore, research must explore how to effectively integrate diverse data and insights from LLMs to improve generalization and robustness in real-world deployments. Emphasis should be placed on developing algorithms that learn to recognize and respond to KU gracefully, rather than relying solely on ever-increasing data or computational power. Finally, the implications of KU for AI safety warrant deeper investigation, particularly concerning potential emergent risks associated with correlated failures in large-scale systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

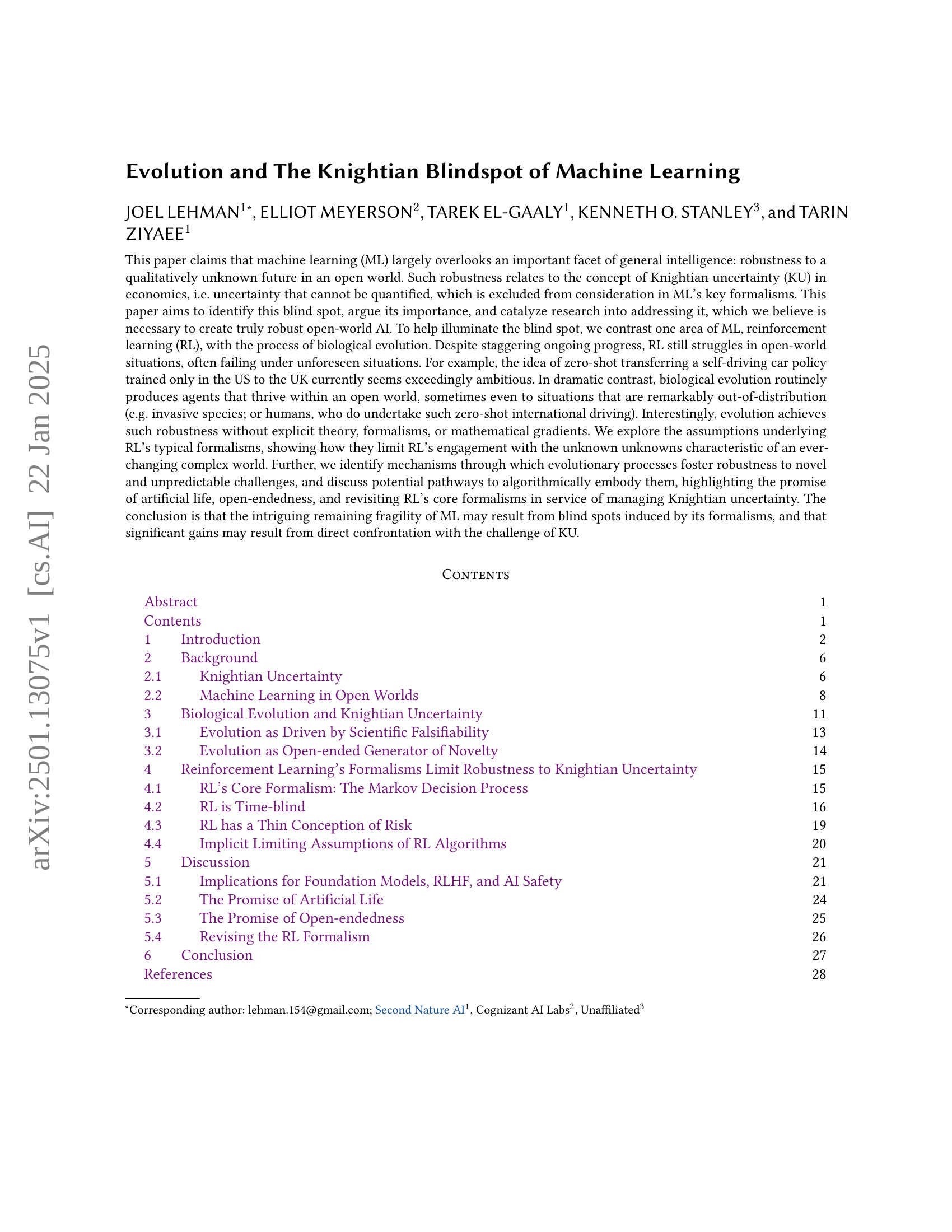

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates two contrasting approaches to handling an open, dynamic world. The ‘diversify and filter’ method (a) continuously generates and tests diverse solutions, with unsuccessful ones eliminated over time. This mirrors how evolution and scientific progress operate. The ‘anticipate and train’ method (b), prevalent in machine learning, involves collecting known challenges and training a single model to solve them. This approach, however, can fail due to its reliance on generalization and closed-world assumptions. The figure highlights that machine learning could benefit from incorporating aspects of the ‘diversify and filter’ approach.

read the caption

Figure 2. Two Strategies for Dealing with an Open World. This figure describes two possible strategies for coping with an open changing world. In (a) diversify-and-filter, a process continually refreshes and adapts its diverse hypotheses about how to persist through the open-ended future. Such hypotheses are filtered through empirical success at tackling later unanticipated problems. Evolution, market competition, and science can be seen to largely operate through this paradigm. There is no explicit formalism, although robustness implicitly relies on the Lindy effect (Taleb, 2014), i.e. an adaptable solution long-tested by time is more likely than an untested one to persist yet longer. In (b) anticipate-and-train, diverse problems are first collected, and augmented through human anticipation about what novel situations might later arise. Then, a single policy is trained to solve the problems to convergence, and that policy is then deployed into a changing world. Much of current ML adopts this paradigm; although the closed-world formalism adopted in training mismatches the open world it is deployed into, the hope is that generalization will enable sufficient robustness to unforeseen challenges. One conclusion is that nothing precludes machine learning from more deeply integrating diversify-and-filter approaches into its methods (Lehman and Stanley, 2010; Kumar et al., 2020; Jaderberg et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2023). Another conclusion is that diversify-and-filter leverages the temporal structure of when novel problems arise, and forces agents to directly grapple with the issue of KU (if they do not, they are discarded).

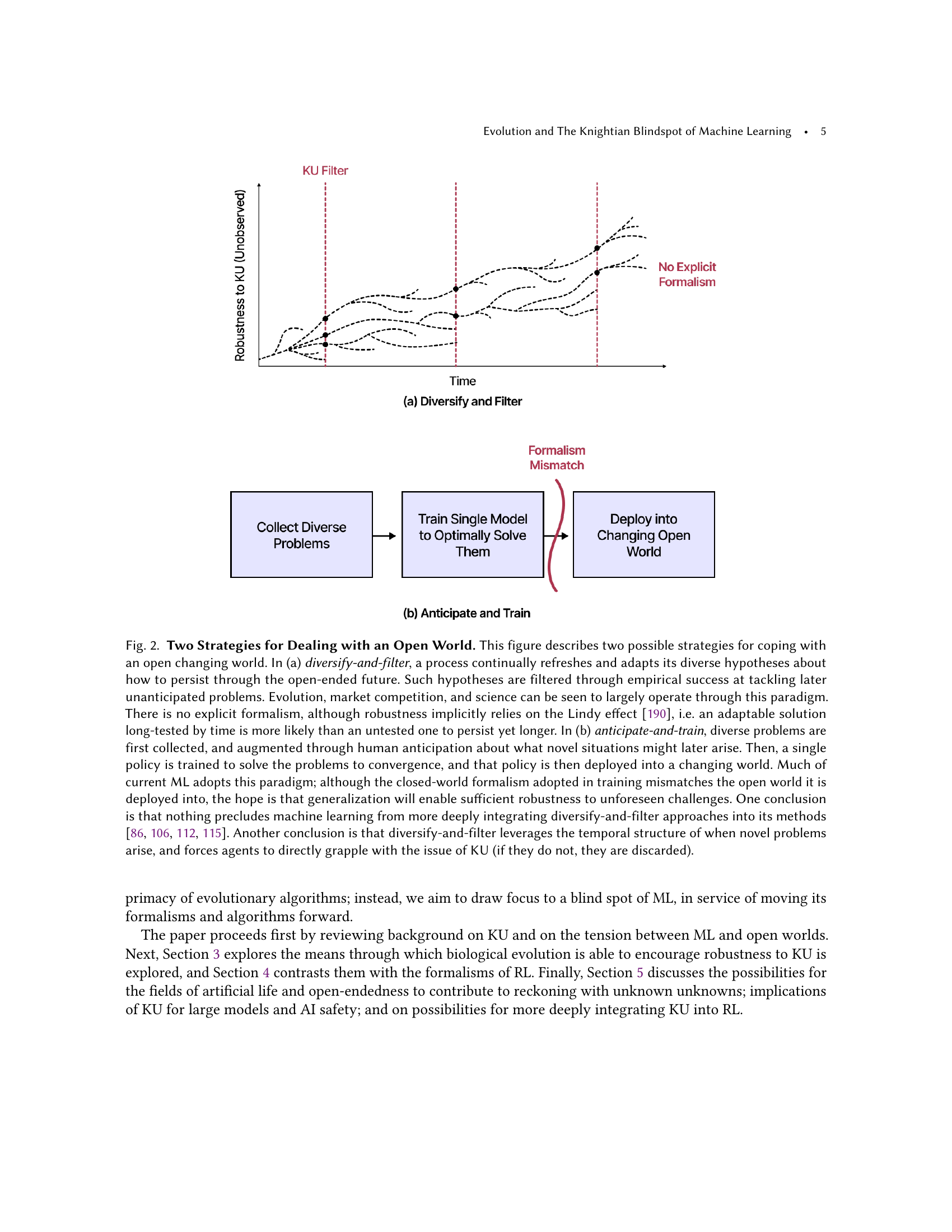

🔼 The figure illustrates how focusing solely on known risks (known unknowns) during training can negatively impact an agent’s ability to handle unknown unknowns (Knightian uncertainty) in real-world scenarios. A closed-world optimization approach, while improving performance within the anticipated training environment, inadvertently makes the agent overly reliant on its learned assumptions. This over-reliance leads to increased fragility when faced with unexpected situations outside of the training data, hence increasing the risk from Knightian uncertainty. The figure uses a Venn diagram to visually represent the relationship between known and unknown risks, demonstrating how optimizing for known risks can leave the agent vulnerable to unforeseen circumstances.

read the caption

Figure 3. Optimizing for known unknowns can exacerbate risk from Knightian uncertainty. An optimization formalism that makes closed-world assumptions will indeed improve an agent’s performance on the situations an experimenter anticipates. However, if such a closed-world optimizer aggressively trains an open-world agent, the agent may perversely become more brittle to Knightian uncertainty, as it is incentivized to internalize the closed-world assumptions as true.

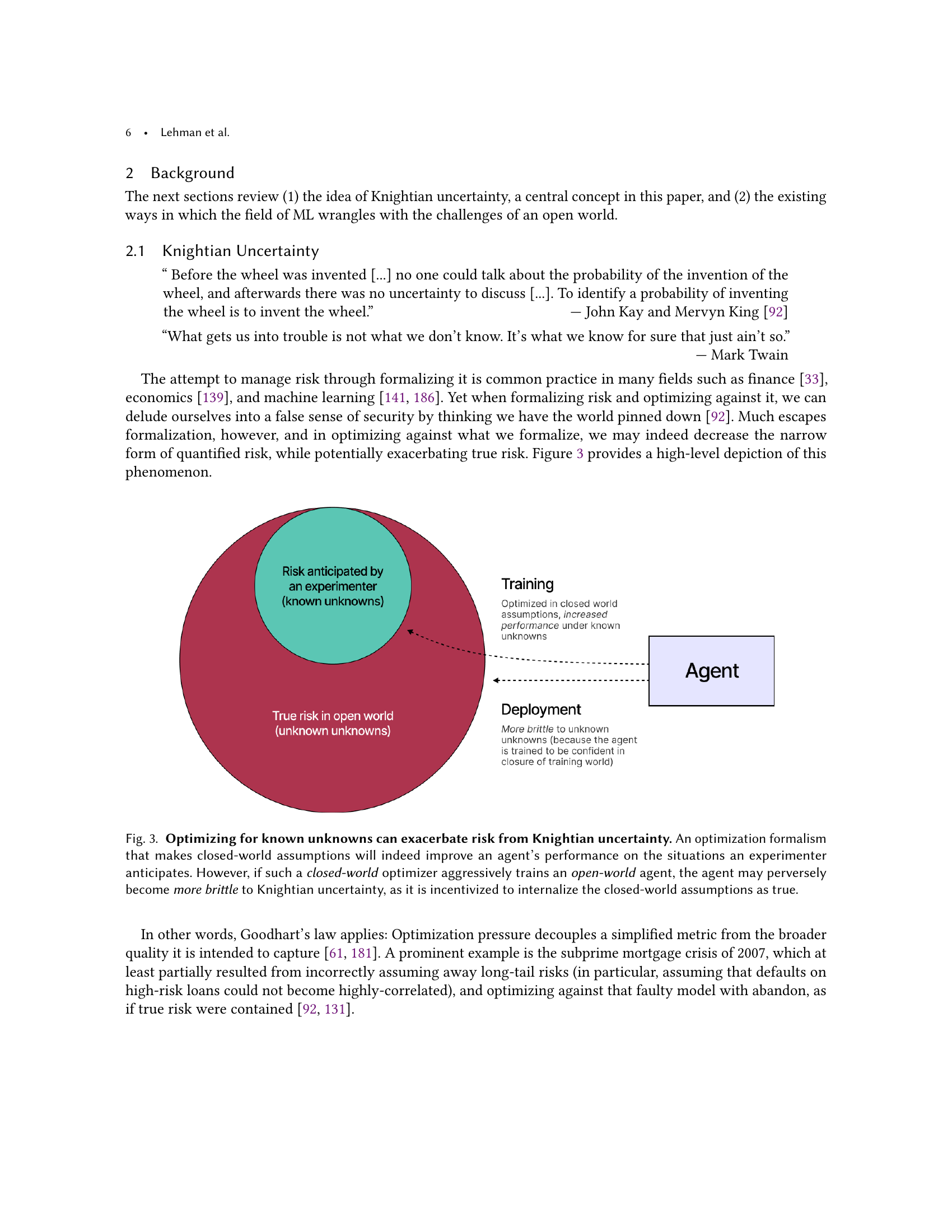

🔼 This figure uses a mushroom-eating scenario to illustrate the limitations of neural network generalization in handling Knightian uncertainty. Panel (a) shows a closed-world scenario where a neural network (NN) is trained to distinguish between edible and poisonous mushrooms based on their cap size and thickness. The NN learns a decision boundary that effectively separates the two types of mushrooms based on the training data. Panel (b) shows that, in this closed world, the NN accurately predicts the edibility of mushrooms during testing, reflecting the training data distribution. However, panel (a) also introduces an open-world scenario. In an open world, unknown mushroom types may exist, or the environment may change (new mushroom species, different ecosystems), leading to situations not covered in the training data. Encountering an unfamiliar mushroom (marked with a question mark), the open-world agent rationally chooses not to consume it due to the unknown risk. This example highlights that simple generalization from known data is insufficient to address the problem of unknown unknowns (Knightian uncertainty).

read the caption

Figure 4. Neural network generalization is not a general cure for Knightian Uncertainty. Imagine as part of a larger reinforcement learning policy, an agent decides whether to eat certain mushrooms, which can either be deadly or edible, and can be separated through features learned in training that correspond to the cap size of the mushroom and its thickness. (a) In a closed world, it is safe to assume that the distribution of mushrooms encountered during training (red ×\times×’s and green +++’s) reflects that encountered during testing, and the (b) NN decision boundary on whether to eat or not eat the mushroom learned through training will likely reflect this assumption. However, in an open world, not all mushroom varieties are known, the policy might be deployed in a slightly different ecosystem, or a new variety of mushroom might evolve or be bred. If encountering the unanticipated mushroom (question mark symbol) at the center of (a), it is likely rational for an open-world agent to forgo eating it, given its novelty and the risk of death. The claim is that simple generalization from what is known does not address Knightian uncertainty.

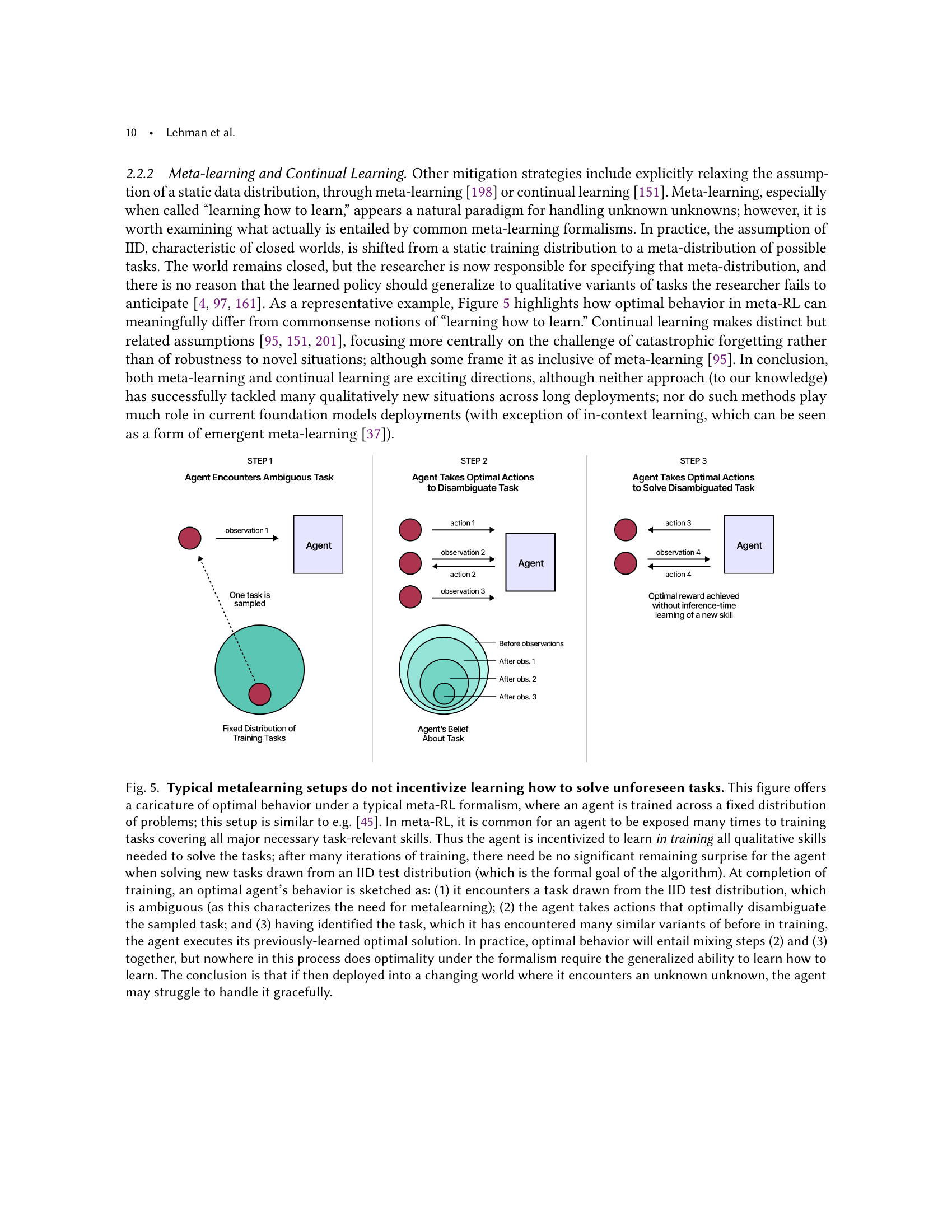

🔼 The figure illustrates the limitations of standard meta-reinforcement learning (meta-RL) approaches in handling unforeseen tasks. Meta-RL typically trains agents on a fixed set of tasks, optimizing their performance on those known tasks. The figure depicts an optimal agent within this framework; it first disambiguates an ambiguous task using prior training and then solves the task using a pre-learned solution. This approach is effective for known tasks but fails to generalize to novel or unexpected tasks. The key takeaway is that the standard meta-RL formalism doesn’t incentivize the ability to learn how to solve genuinely new tasks, which is crucial for true generalization and robustness in open-world scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 5. Typical metalearning setups do not incentivize learning how to solve unforeseen tasks. This figure offers a caricature of optimal behavior under a typical meta-RL formalism, where an agent is trained across a fixed distribution of problems; this setup is similar to e.g. (Duan et al., 2016). In meta-RL, it is common for an agent to be exposed many times to training tasks covering all major necessary task-relevant skills. Thus the agent is incentivized to learn in training all qualitative skills needed to solve the tasks; after many iterations of training, there need be no significant remaining surprise for the agent when solving new tasks drawn from an IID test distribution (which is the formal goal of the algorithm). At completion of training, an optimal agent’s behavior is sketched as: (1) it encounters a task drawn from the IID test distribution, which is ambiguous (as this characterizes the need for metalearning); (2) the agent takes actions that optimally disambiguate the sampled task; and (3) having identified the task, which it has encountered many similar variants of before in training, the agent executes its previously-learned optimal solution. In practice, optimal behavior will entail mixing steps (2) and (3) together, but nowhere in this process does optimality under the formalism require the generalized ability to learn how to learn. The conclusion is that if then deployed into a changing world where it encounters an unknown unknown, the agent may struggle to handle it gracefully.

Full paper#