TL;DR#

Current video benchmarks inadequately assess Large Multimodal Models’ (LMMs) ability to learn from videos. This limits our understanding of how well these models acquire knowledge compared to humans, and what improvements are needed. Existing benchmarks often focus on simpler visual understanding tasks, neglecting the cognitive processes involved in true knowledge acquisition.

To address this, researchers created Video-MMMU, a new benchmark using a diverse set of 300 expert-level videos and 900 human-annotated questions. Video-MMMU systematically evaluates LMMs across three cognitive stages: perception, comprehension, and adaptation. The results reveal a considerable gap between human and model learning abilities and highlight the challenge of enabling LMMs to acquire complex knowledge from videos.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multimodal learning and large language models. It introduces a novel benchmark, Video-MMMU, for evaluating knowledge acquisition from videos, addressing a significant gap in current research. This benchmark is highly relevant to the ongoing effort to improve LLM understanding of video content and opens new avenues for research into more effective video-based learning techniques.

Visual Insights#

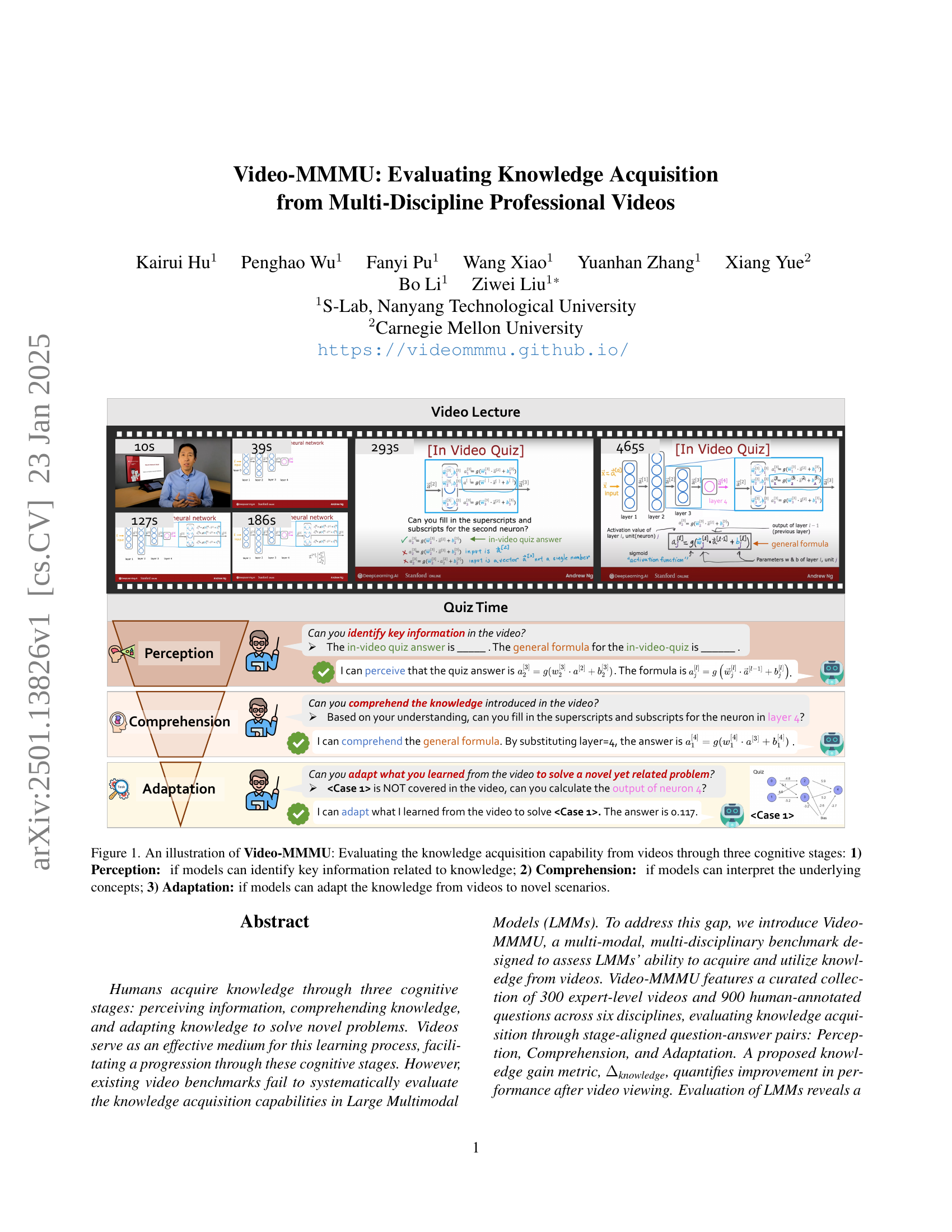

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates the three stages of knowledge acquisition in Video-MMMU: Perception, Comprehension, and Adaptation. Perception focuses on whether a model can extract key pieces of information from a video. Comprehension assesses the model’s ability to understand the core concepts presented in the video. Finally, Adaptation tests the model’s capacity to apply this learned knowledge to solve new and related problems not directly shown in the video. Each stage involves a different level of cognitive complexity, progressing from simple information retrieval to complex problem solving.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of Video-MMMU: Evaluating the knowledge acquisition capability from videos through three cognitive stages: 1) Perception: if models can identify key information related to knowledge; 2) Comprehension: if models can interpret the underlying concepts; 3) Adaptation: if models can adapt the knowledge from videos to novel scenarios.

| Benchmarks | Video | Question | Video | Knowledge |

| Domain | Length | Duration | driven | |

| Video-MME [9] | Open | 35.7 | 1017.9 | ✗ |

| MMBench-Video [7] | Open | 10.9 | 165.4 | ✗ |

| Video-Bench [25] | Open | 21.3 | 56.0 | ✗ |

| TempCompass [20] | Open | 49.2 | 11.4 | ✗ |

| MVBench [17] | Open | 27.3 | 16.0 | ✗ |

| AutoEval-Video [5] | Open | 11.9 | 14.6 | ✗ |

| Video-MMMU | Professional | 75.7 | 506.2 | ✓ |

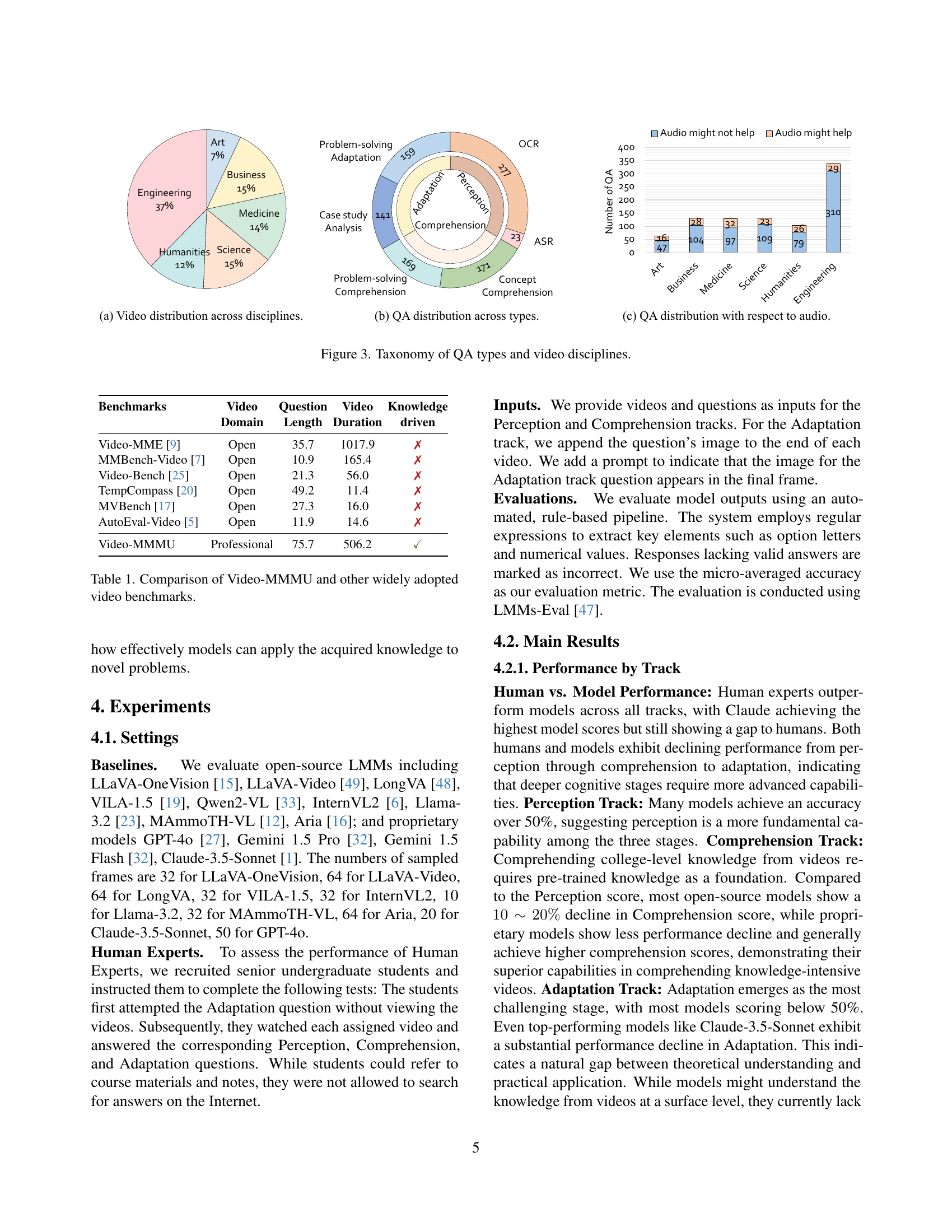

🔼 This table compares Video-MMMU with other popular video question answering benchmarks, highlighting key differences in terms of video domains, question length, video duration, and whether the benchmark focuses on knowledge-driven question answering. It demonstrates that Video-MMMU is unique in its focus on evaluating knowledge acquisition from professional-level educational videos, which require deeper understanding and reasoning beyond visual recognition tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Video-MMMU and other widely adopted video benchmarks.

In-depth insights#

Video-Based Learning#

Video-based learning presents a powerful and engaging method for knowledge acquisition, leveraging the visual and auditory senses to facilitate comprehension and retention. Effective video-based learning designs progress systematically through cognitive stages, starting with the perception of information, followed by comprehension of concepts, and culminating in the application of learned knowledge to novel problems. High-quality educational videos should be rich in multimedia elements, providing clear explanations, demonstrations, and examples to cater to diverse learning styles. However, the effectiveness of video-based learning hinges on careful pedagogical design, ensuring relevance, clarity, and appropriate pacing. The successful integration of video into educational settings requires thoughtful consideration of learner needs, assessment strategies, and technological infrastructure. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of current AI models in fully emulating the human capacity for video-based learning. While some progress has been made, significant gaps remain in models’ abilities to perceive, comprehend, and adapt knowledge from video content, particularly in complex or nuanced situations. Future research should focus on improving the capabilities of AI in extracting meaningful insights and generating effective learning experiences from video data.

MMMU Benchmark#

A hypothetical MMMU Benchmark in a research paper would likely involve a multifaceted evaluation of large multimodal models (LMMs). It would assess their ability to acquire and utilize knowledge from diverse, professional-level videos. The benchmark would likely incorporate multiple stages of cognitive processing: perception (identifying key information), comprehension (understanding underlying concepts), and adaptation (applying knowledge to novel problems). Multi-disciplinary video datasets would be crucial, spanning various fields to test generalizability and avoid overfitting to specific domains. Quantitative metrics would be essential, possibly including a ‘knowledge gain’ metric to capture improvement in performance after video exposure. The benchmark would help researchers understand the strengths and weaknesses of LMMs in real-world knowledge acquisition tasks, and would likely facilitate the development of more robust and human-like learning capabilities in AI models. A crucial aspect would be the detailed annotation and quality control of videos and questions, ensuring the validity and reliability of the benchmark’s results.

Cognitive Track Eval#

A hypothetical “Cognitive Track Eval” section in a research paper would delve into the evaluation methodology for assessing knowledge acquisition through different cognitive stages. It would likely involve a detailed description of the three-stage model (Perception, Comprehension, Adaptation), outlining how each stage is measured. The metrics used, such as accuracy scores or a novel knowledge gain metric, would be defined and justified. The evaluation process would be explained, including the types of questions used to assess each cognitive level, the datasets employed, and the models tested. Benchmarking against existing methods would demonstrate the novelty and effectiveness of the proposed evaluation scheme. Finally, a discussion of the limitations and potential future improvements to the cognitive evaluation would be critical, for example, acknowledging the challenges of accurately measuring complex cognitive processes, and addressing potential biases inherent in the evaluation tasks and datasets. The analysis of results from this evaluation would form a significant part of this section, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of different large multimodal models (LMMs) in acquiring and applying knowledge from videos.

Model Limitations#

Large multimodal models (LMMs) demonstrate significant limitations in acquiring and applying knowledge from videos, especially as cognitive demands increase. Performance noticeably declines on comprehension and adaptation tasks, highlighting a critical gap between human and model learning capabilities. While LMMs show some progress in knowledge acquisition, as evidenced by improvement on specific questions after video exposure, this improvement is often offset by a tendency to lose previously correct answers, indicating a fragility in knowledge retention and application. Models struggle with adapting learned methods to novel scenarios, often failing to translate theoretical understanding to practical application. This suggests that existing LMMs lack the robust, adaptable reasoning capabilities needed for effective real-world video-based learning. Addressing these limitations requires further research focusing on improving knowledge retention, adaptable reasoning, and the ability to handle nuanced problem-solving in dynamic contexts.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize addressing the significant gap between human and model knowledge acquisition from videos. Improving LMMs’ ability to adapt learned knowledge to novel scenarios is crucial, focusing on enhancing their ability to process and reason with information presented in diverse visual formats, including complex diagrams and handwritten notes. Further exploration of the interplay between audio and visual information is needed, investigating how audio transcripts can both enhance and hinder effective knowledge acquisition. Developing more sophisticated evaluation metrics beyond simple accuracy, such as those capturing the nuanced aspects of human learning, is essential to better understand model capabilities and limitations. Finally, expanding Video-MMMU with a broader range of disciplines and more complex question types, especially those requiring higher-order reasoning and problem-solving, will provide more robust benchmarks for assessing progress in video-based learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

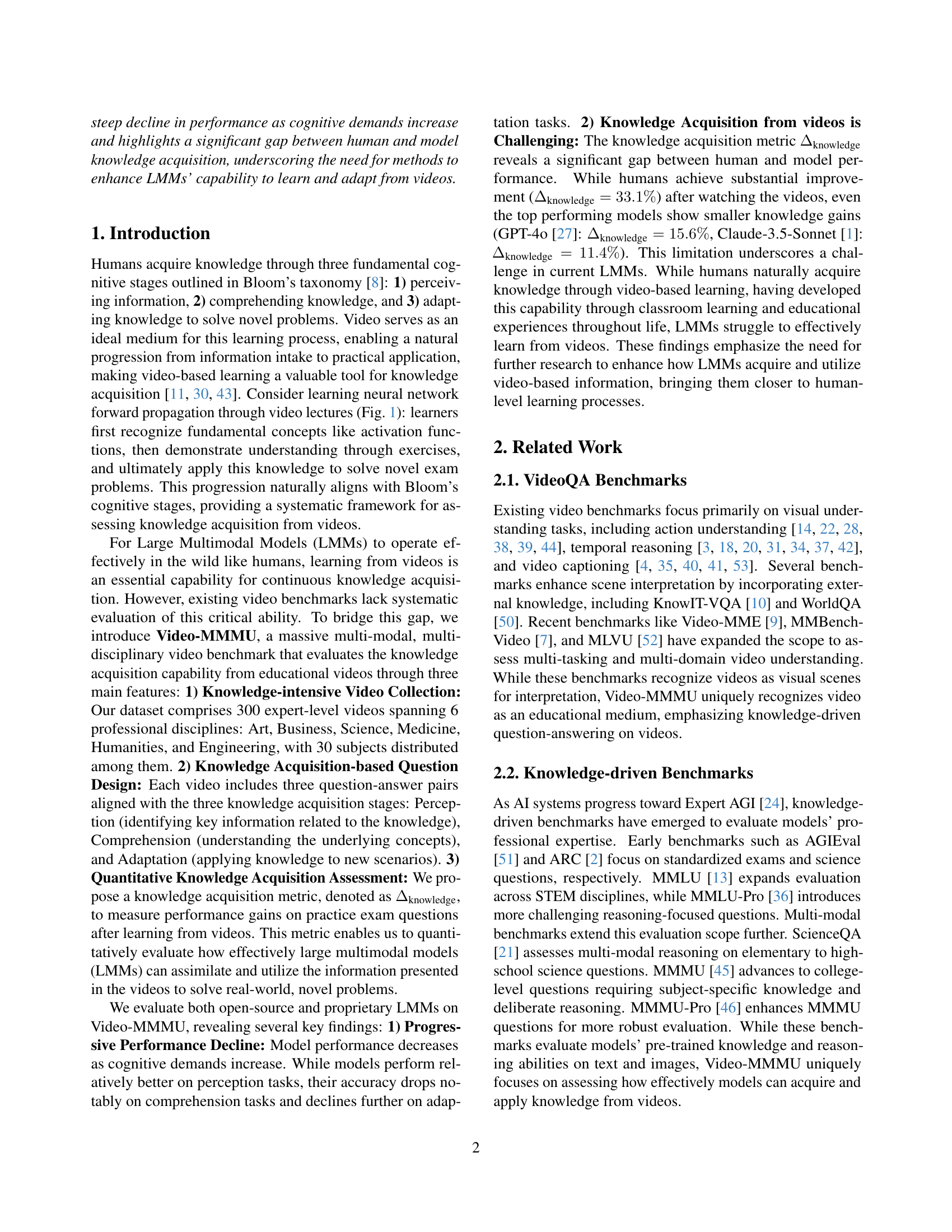

🔼 Figure 2 presents examples from the Video-MMMU dataset, showcasing the diversity of its content. The dataset includes videos from six academic disciplines (Art, Business, Humanities, Medicine, Science, and Engineering) and three tracks of questions (Perception, Comprehension, and Adaptation) designed to evaluate different levels of knowledge acquisition. The figure is organized into two rows. The top row displays Concept-Introduction videos, which primarily focus on explaining core concepts and theories using explanatory content. The bottom row shows Problem-Solving videos, which demonstrate step-by-step solutions to example questions, often illustrating practical applications of the concepts presented.

read the caption

Figure 2: Sampled Video-MMMU examples across 6 academic disciplines and 3 tracks. The examples are organized in two rows based on distinct video types: (1) Concept-Introduction videos (top row) focus on teaching factual knowledge, fundamental concepts, and theories through explanatory content, while (2) Problem-Solving videos (bottom row) demonstrate step-by-step solutions to an example question.

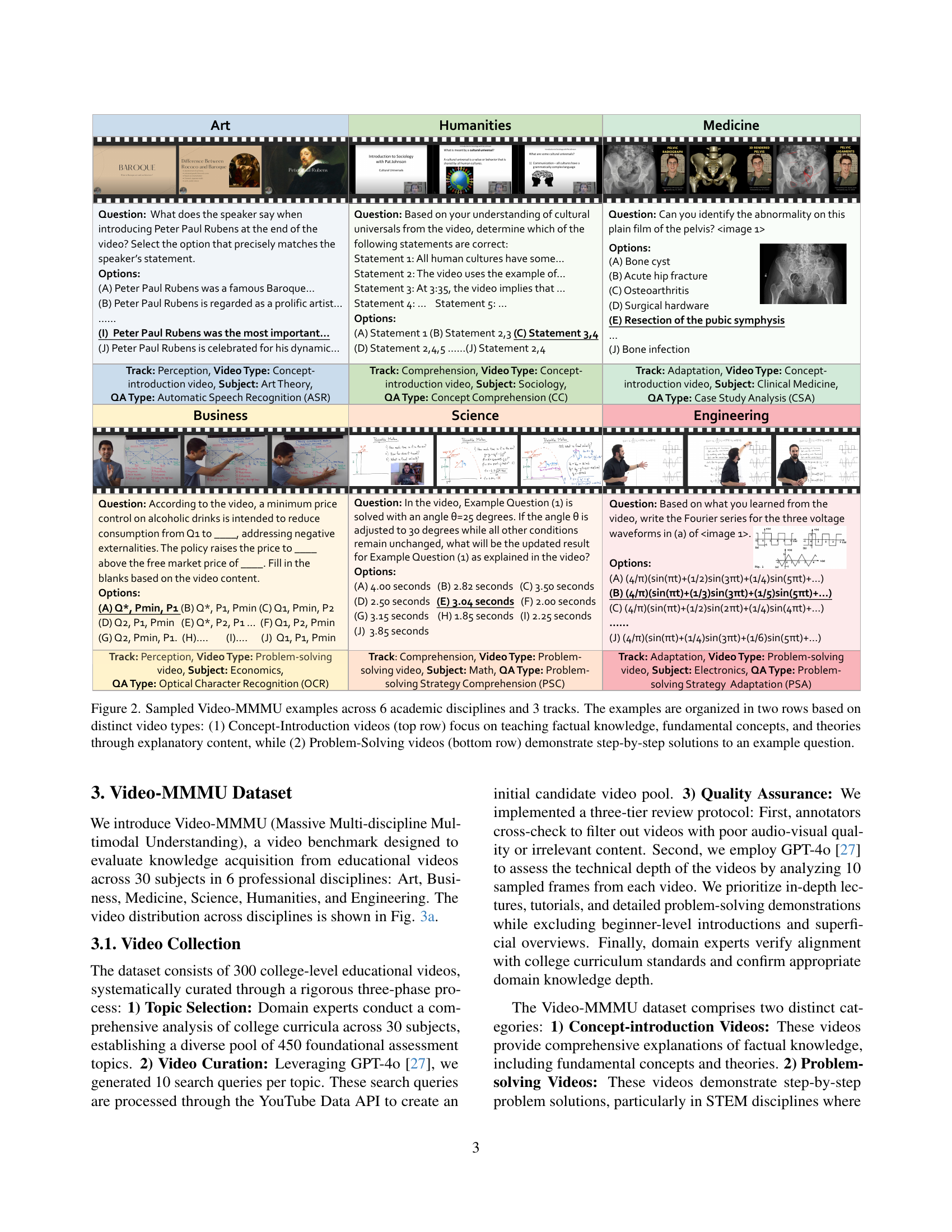

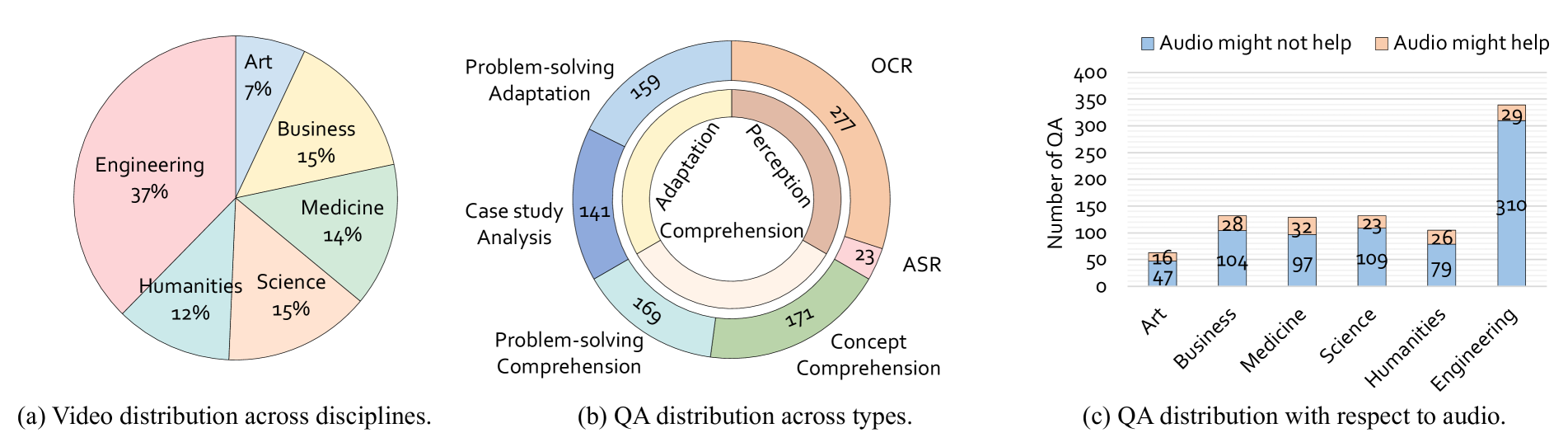

🔼 Figure 3 presents a taxonomy of the question and answer (QA) pairs used in the Video-MMMU dataset, categorized by cognitive level and video discipline. (a) shows a pie chart illustrating the distribution of videos across six disciplines: Art, Business, Humanities, Medicine, Science, and Engineering. (b) displays a donut chart visualizing the distribution of QA pairs across the three cognitive levels: Perception, Comprehension, and Adaptation. Finally, (c) presents bar charts depicting the number of questions that do or do not utilize audio for each discipline.

read the caption

Figure 3: Taxonomy of QA types and video disciplines.

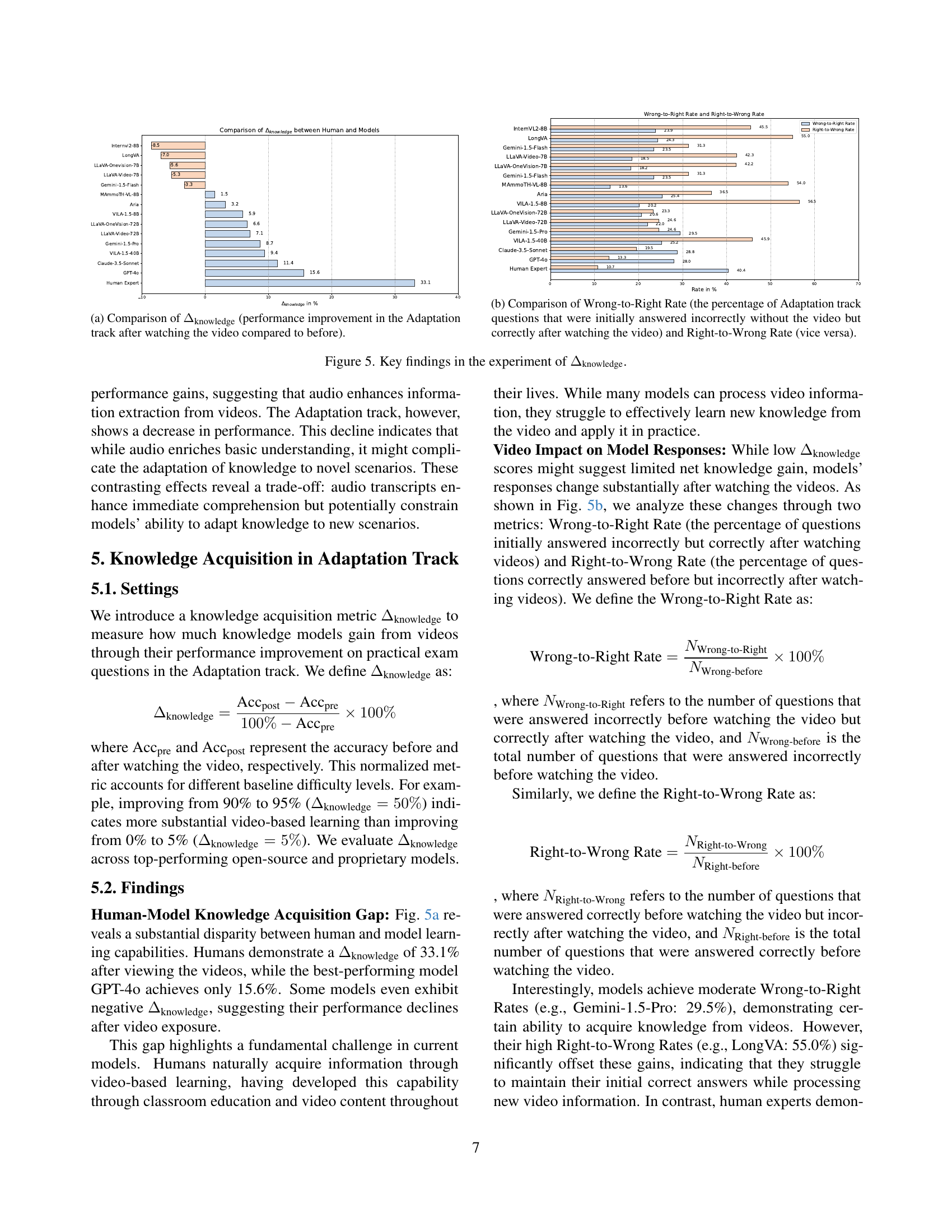

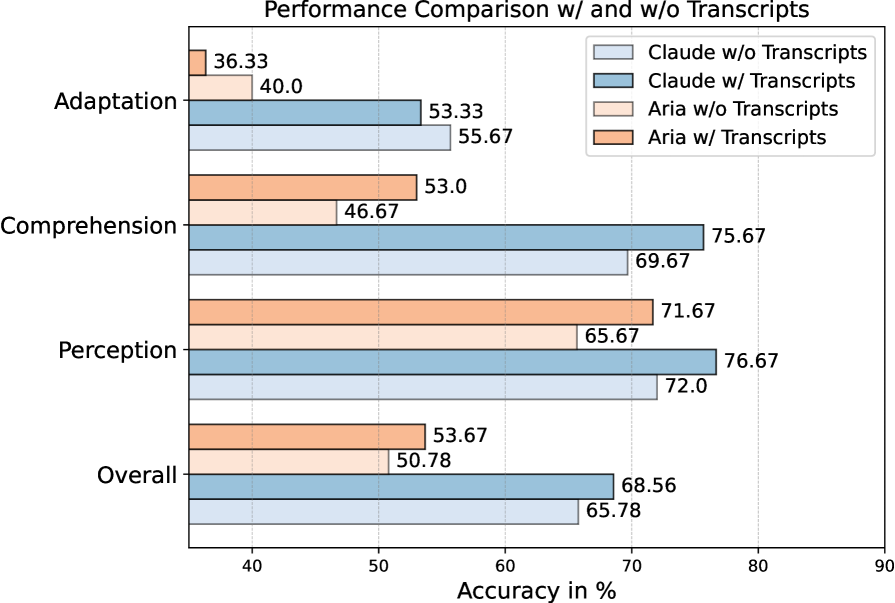

🔼 This figure shows the performance comparison of different large multimodal models (LLMs) across three knowledge acquisition tracks (Perception, Comprehension, and Adaptation) before and after adding audio transcripts to the video inputs. The x-axis represents the different tasks, while the y-axis shows the accuracy in percentage. The chart visually demonstrates the impact of including audio information on the models’ ability to acquire knowledge from videos. Specifically, it highlights whether the additional audio context improves or hinders the models’ performance on each type of task. We can compare the model’s performance on the same task with or without audio to better understand the role of audio in video-based learning.

read the caption

Figure 4: Performance comparison across tracks before and after adding audio transcripts.

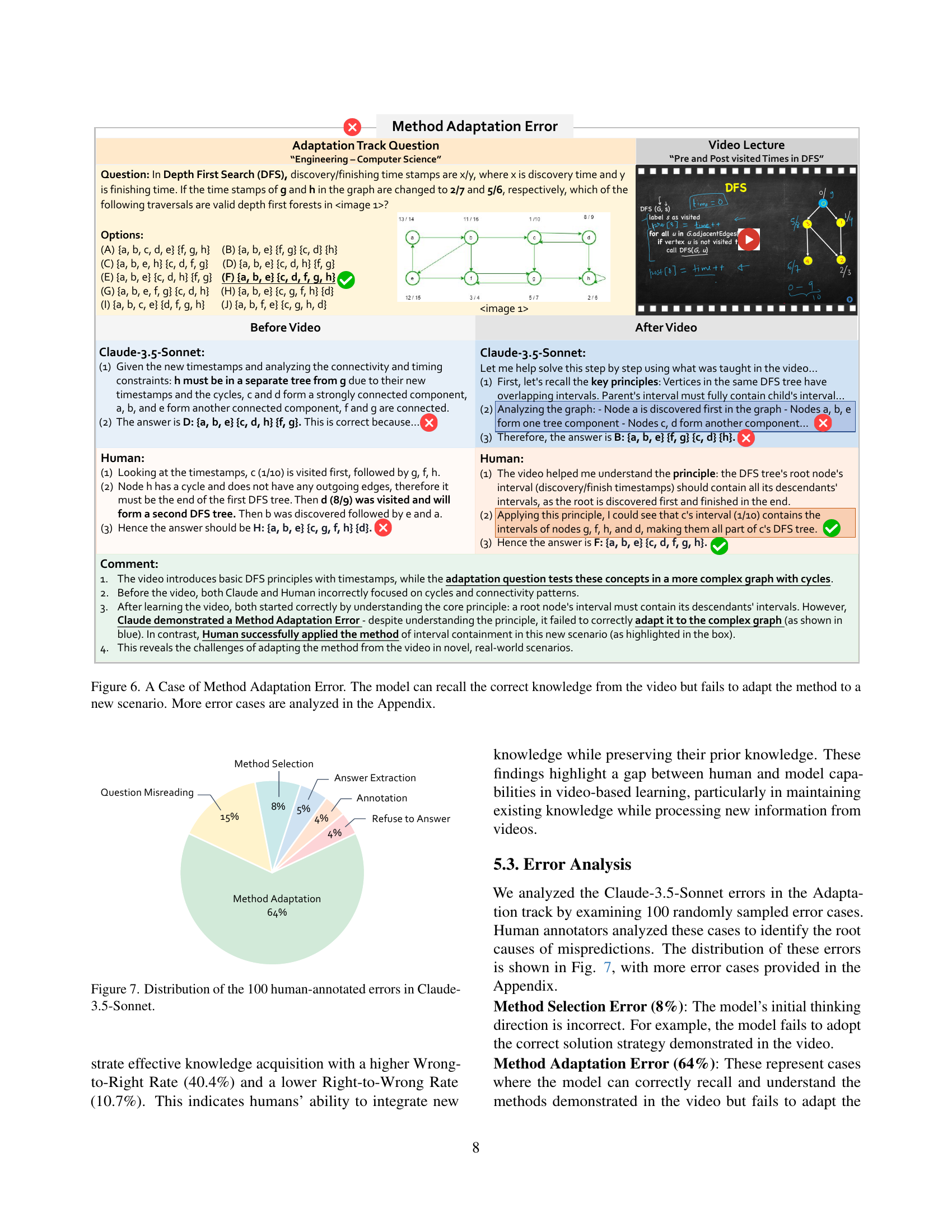

🔼 The figure shows a bar chart comparing the knowledge gain (Δknowledge) of different large language models (LLMs) and humans after watching videos in the Adaptation track of the Video-MMMU benchmark. Δknowledge represents the percentage improvement in the models’ performance on post-video questions compared to their pre-video performance on the same questions. Higher values indicate a greater knowledge gain from the videos. The chart visually demonstrates the significant difference in knowledge acquisition between human subjects and the various LLMs, highlighting the challenge LLMs face in adapting and applying knowledge from videos to new scenarios.

read the caption

(a) Comparison of ΔknowledgesubscriptΔknowledge\Delta_{\text{knowledge}}roman_Δ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT knowledge end_POSTSUBSCRIPT (performance improvement in the Adaptation track after watching the video compared to before).

🔼 This figure shows two bar charts visualizing the performance of different large language models (LLMs) on the Adaptation track of the Video-MMMU benchmark. The left chart displays the ‘Wrong-to-Right Rate,’ which represents the percentage of questions initially answered incorrectly by the model without watching the video but correctly after watching the video. The right chart displays the ‘Right-to-Wrong Rate,’ which represents the percentage of questions initially answered correctly by the model but incorrectly after watching the video. Both charts help illustrate how the LLMs’ knowledge changes (or doesn’t change) after they view a video, offering insights into their ability to acquire and apply knowledge from video content. The comparison highlights the effectiveness of video-based learning for different models and the challenges these models face in adapting their knowledge.

read the caption

(b) Comparison of Wrong-to-Right Rate (the percentage of Adaptation track questions that were initially answered incorrectly without the video but correctly after watching the video) and Right-to-Wrong Rate (vice versa).

🔼 Figure 5 presents key results from the experiment measuring knowledge gain (Δknowledge). The left subplot (a) compares the knowledge gain of humans versus various large language models (LLMs) after watching educational videos. It shows the percentage improvement in performance on a post-video assessment compared to pre-video assessment performance. The right subplot (b) further analyzes LLM responses to questions. It displays two metrics: the Wrong-to-Right Rate (percentage of initially incorrect answers that were corrected after video exposure) and the Right-to-Wrong Rate (percentage of initially correct answers that became incorrect after video exposure). These metrics illustrate how LLMs change their answers after viewing the educational videos, revealing insights into their knowledge acquisition process.

read the caption

Figure 5: Key findings in the experiment of ΔknowledgesubscriptΔknowledge\Delta_{\text{knowledge}}roman_Δ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT knowledge end_POSTSUBSCRIPT.

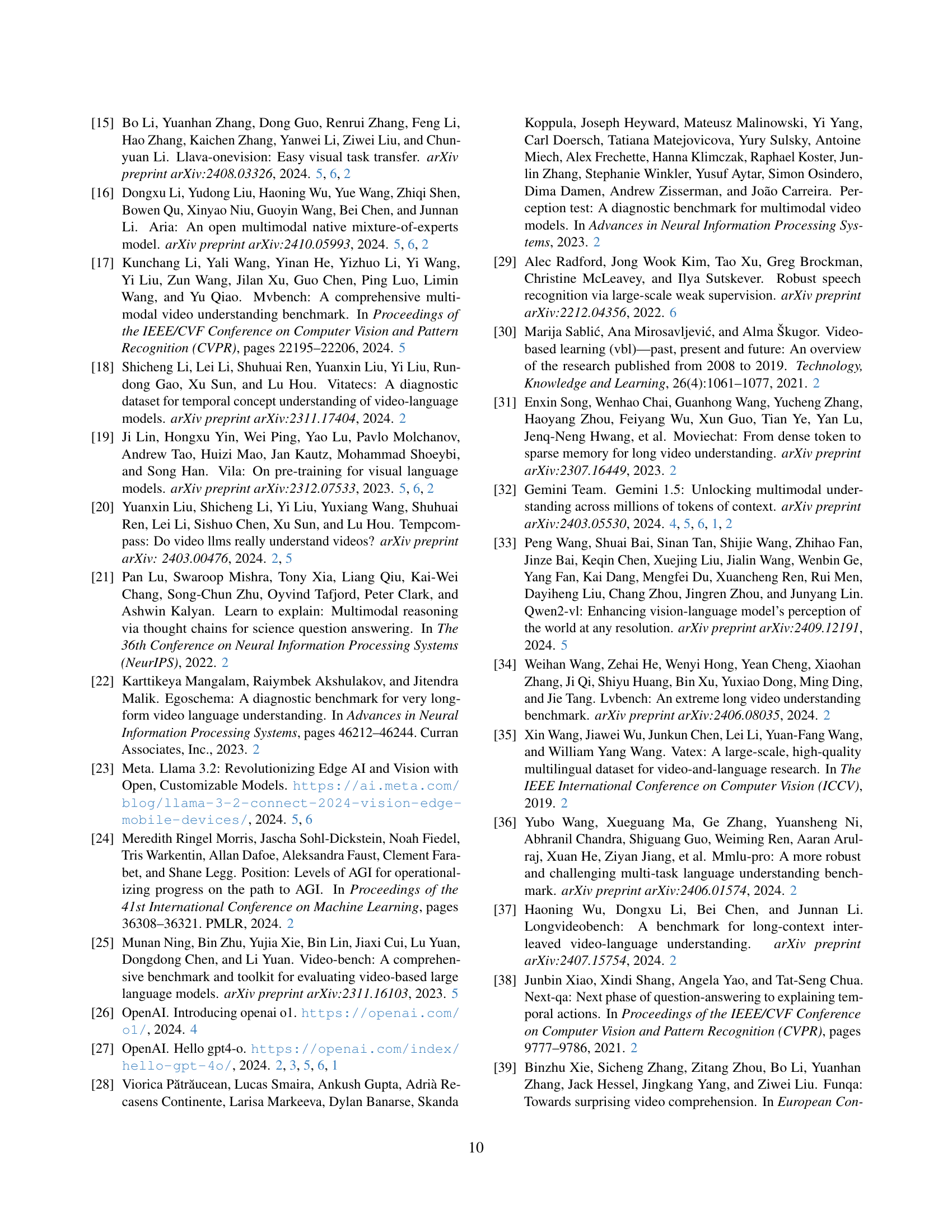

🔼 This figure demonstrates a case where a large language model (LLM) fails to adapt a method learned from a video to a new, slightly different scenario. The model correctly recalls the knowledge presented in the video about Depth-First Search (DFS) and its use in graph traversal, specifically concerning the concept of ‘discovery/finishing’ timestamps. However, when presented with a graph that contains cycles (not shown in the video), the model cannot correctly apply the algorithm. The example highlights the model’s limitation in adapting previously learned knowledge to new, more complex situations where subtle differences in the context significantly alter the procedure.

read the caption

Figure 6: A Case of Method Adaptation Error. The model can recall the correct knowledge from the video but fails to adapt the method to a new scenario. More error cases are analyzed in the Appendix.

🔼 This figure shows a breakdown of the 100 errors that were manually analyzed by human annotators in the responses generated by the Claude-3.5-Sonnet model on the adaptation tasks of the Video-MMMU benchmark. The errors are categorized into five main types: Method Adaptation Error (64%), Question Misreading Error (15%), Method Selection Error (8%), Annotation Error (4%), and Refuse to Answer (4%). The Method Adaptation Error is the most frequent, indicating that the model often struggles to apply knowledge acquired from the video to novel, yet similar problems. Question Misreading suggests the model misunderstood aspects of the questions themselves.

read the caption

Figure 7: Distribution of the 100 human-annotated errors in Claude-3.5-Sonnet.

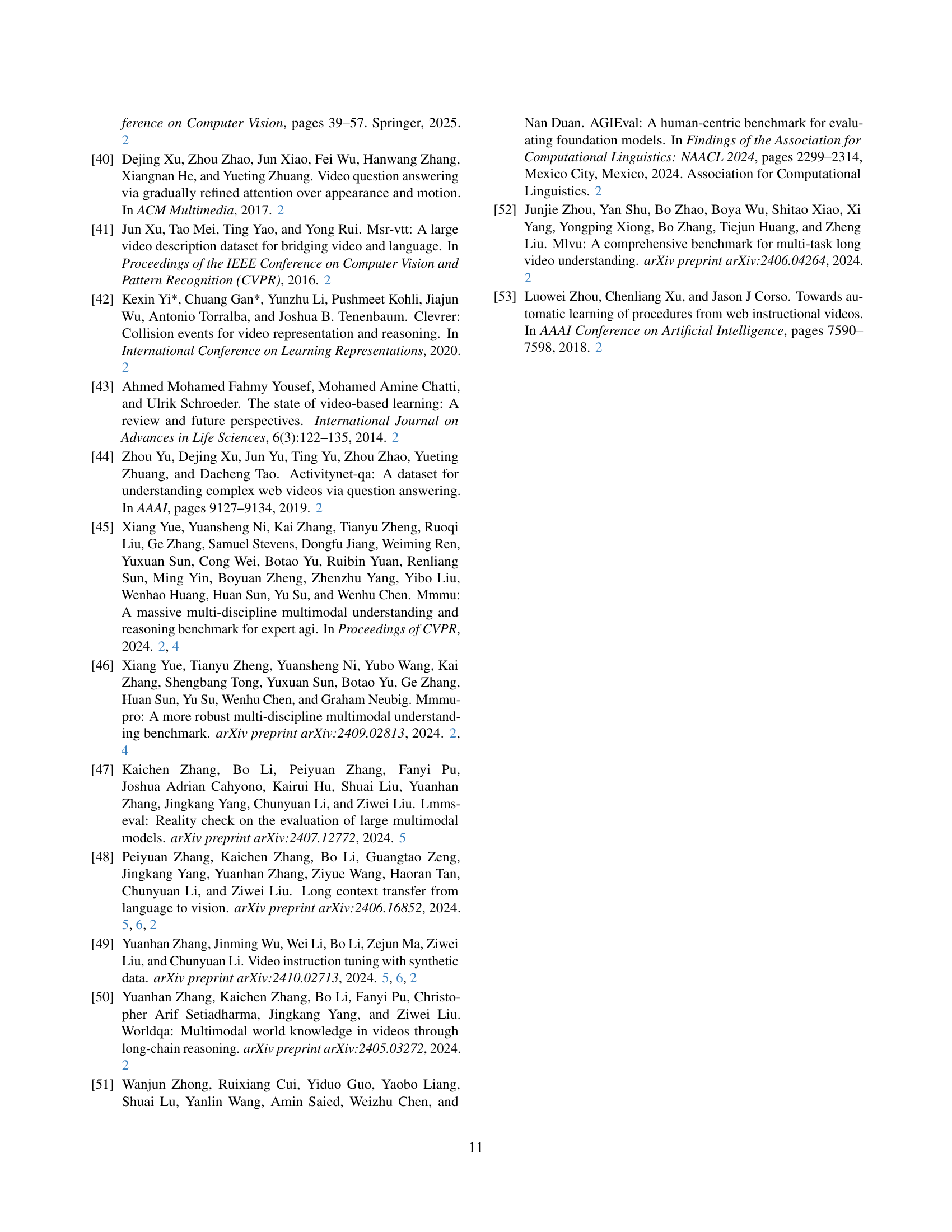

🔼 The prompt shown in Figure 8 is used for the Adaptation track in the Video-MMMU benchmark. It instructs the large multimodal model (LMM) to watch and learn from the provided video and then use that knowledge to answer a question. Importantly, the image related to the question is presented only at the end of the video, forcing the LMM to fully process the video content before attempting to answer. This setup specifically tests the LMM’s ability to adapt previously learned knowledge to a novel scenario.

read the caption

Figure 8: Prompt for Adaptation track.

🔼 This figure shows the prompt used to instruct an AI model to determine whether audio information is necessary to answer a question based on a video. The model is given a video clip, a question, and the corresponding answer. It must then determine if audio was required to answer the question, providing a detailed explanation of its reasoning and outputting a JSON object with a ‘reason’ field (containing the explanation) and a ‘use_audio’ field (a boolean indicating true or false). The JSON output format is also specified in the prompt.

read the caption

Figure 9: Prompt for determining the helpfulness of audio.

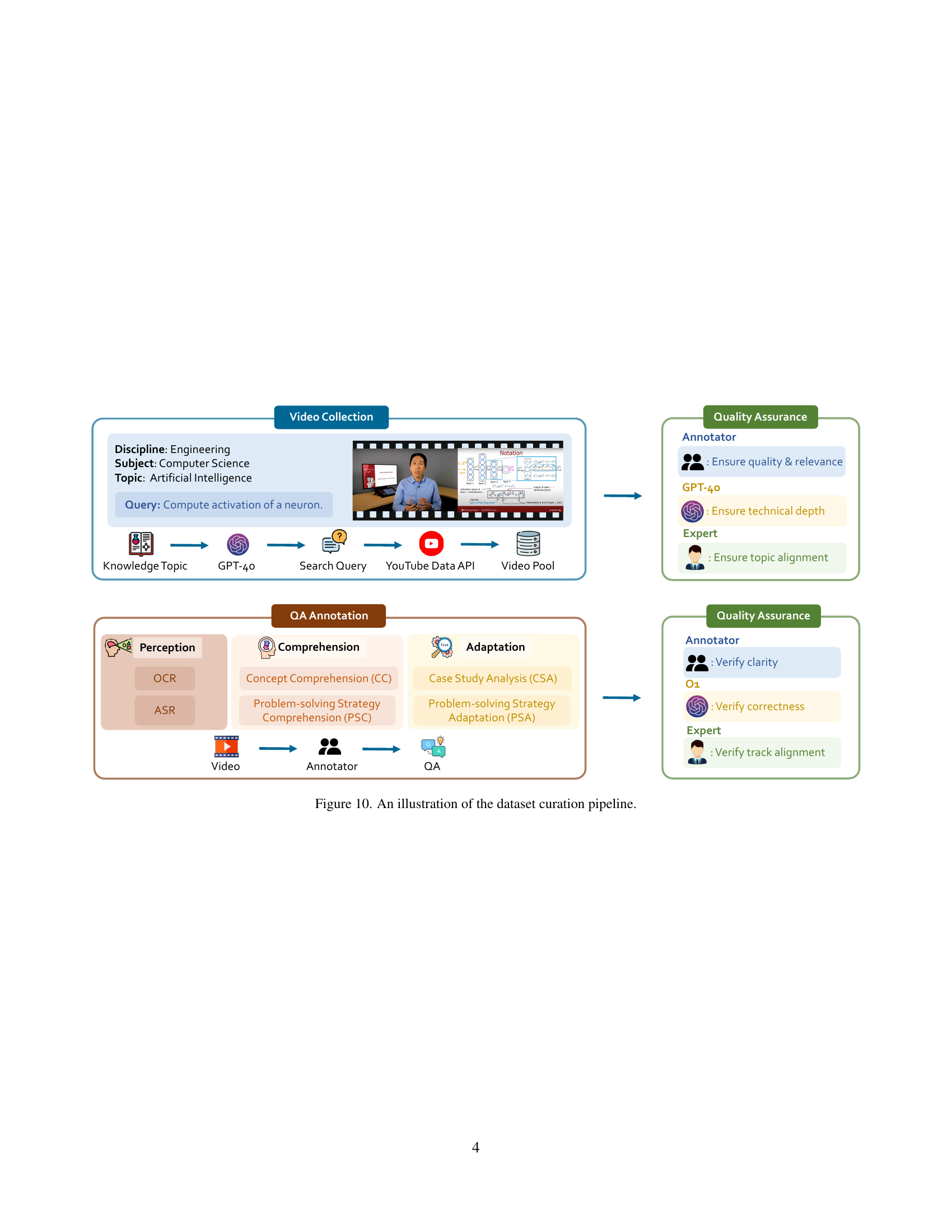

🔼 The figure illustrates the detailed steps involved in creating the Video-MMMU dataset. It starts with selecting topics and curating videos from YouTube using the YouTube Data API and GPT-40. A three-tier quality assurance process is then applied, involving annotators, GPT-40, and domain experts. Next, question-answer pairs (QA) are annotated, categorizing questions into three cognitive levels (Perception, Comprehension, and Adaptation). Each level has different question types (e.g., OCR, ASR, CC, PSC, CSA, PSA). Finally, the audio processing step uses Gemini 1.5 Pro to analyze each video-question pair and assess the potential helpfulness of audio to the models.

read the caption

Figure 10: An illustration of the dataset curation pipeline.

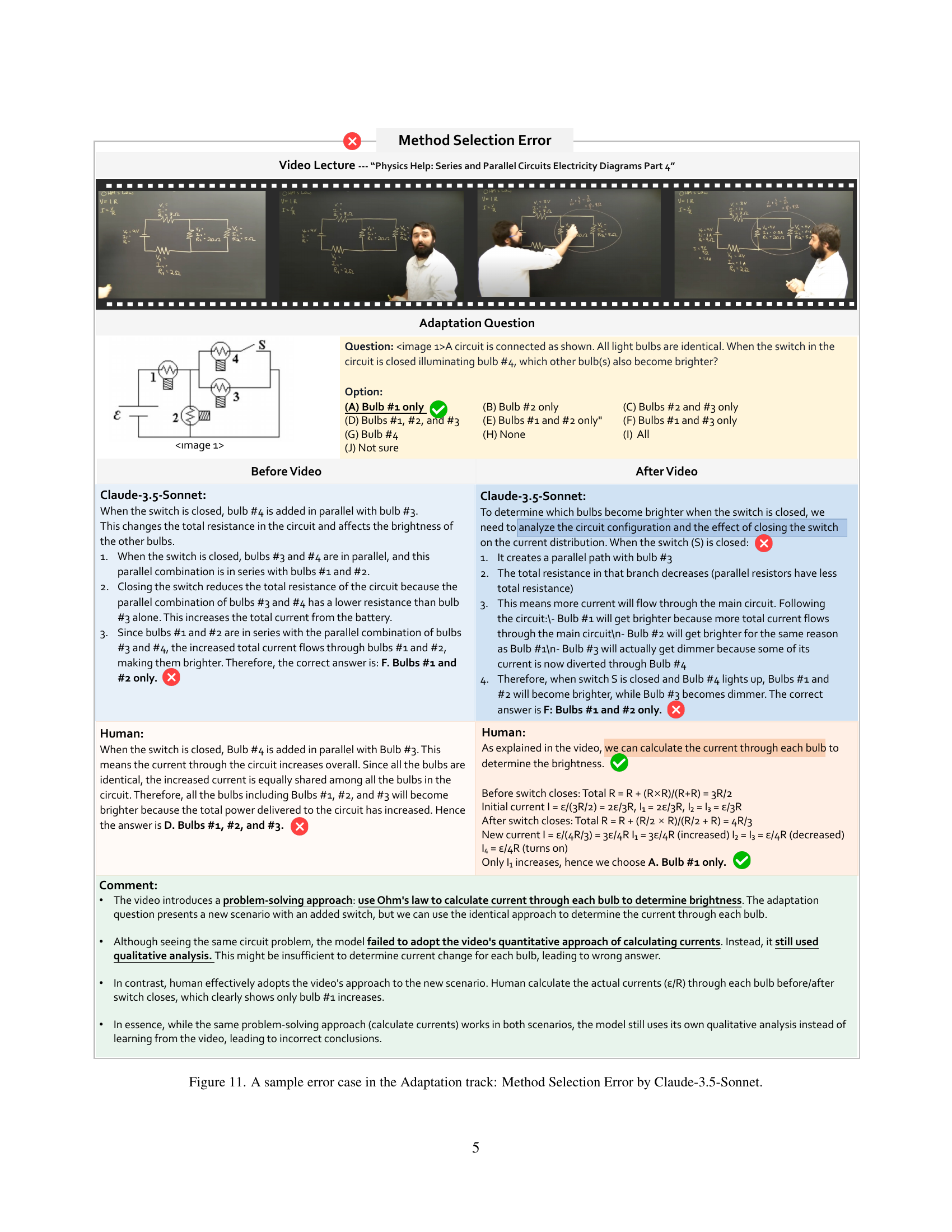

🔼 This figure shows a sample error case from the Adaptation track of the Video-MMMU benchmark. The model, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, is presented with a circuit problem where a switch is added to a parallel circuit. The model fails to correctly adapt the quantitative analysis method of calculating currents from the video example, leading to a wrong answer. The human response correctly applies the method to solve the new problem. This illustrates a Method Selection Error where the model chooses the wrong approach rather than failing to understand the concepts.

read the caption

Figure 11: A sample error case in the Adaptation track: Method Selection Error by Claude-3.5-Sonnet.

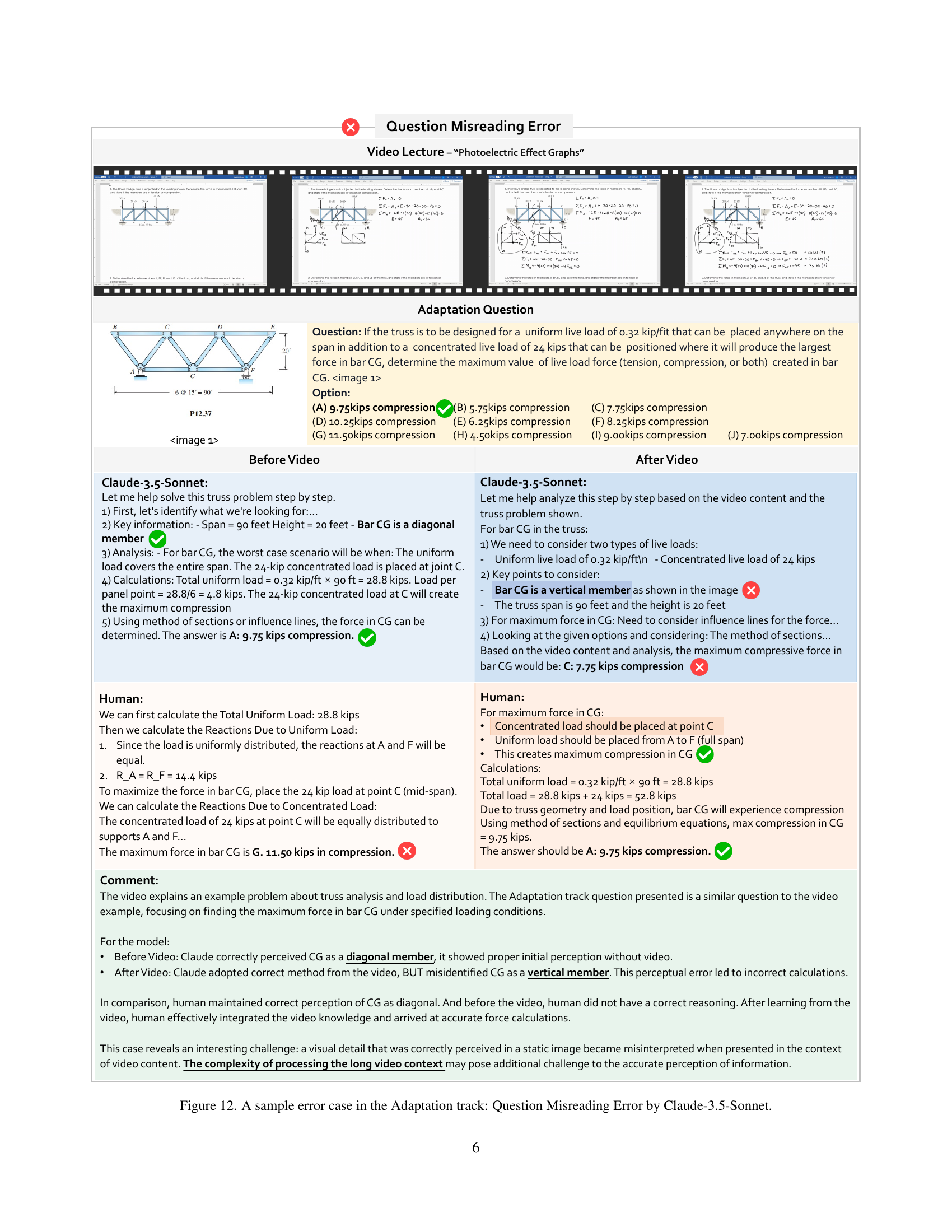

🔼 This figure showcases a case where Claude-3.5-Sonnet, a large language model, made an error in solving an adaptation task due to misinterpreting the question. The task involves analyzing a Howe bridge truss structure under a specified load, specifically calculating the maximum force in bar CG. The model correctly identifies the necessary steps (calculating reactions, applying the method of sections) but misinterprets a key detail in the problem statement: it incorrectly assumes that bar CG is a vertical member, leading to inaccurate calculations. In contrast, a human expert correctly identifies CG as a diagonal member and performs the calculations accurately, resulting in a different answer. This highlights a limitation of the model in precisely extracting information and applying it correctly to problem solving within the context of the presented information.

read the caption

Figure 12: A sample error case in the Adaptation track: Question Misreading Error by Claude-3.5-Sonnet.

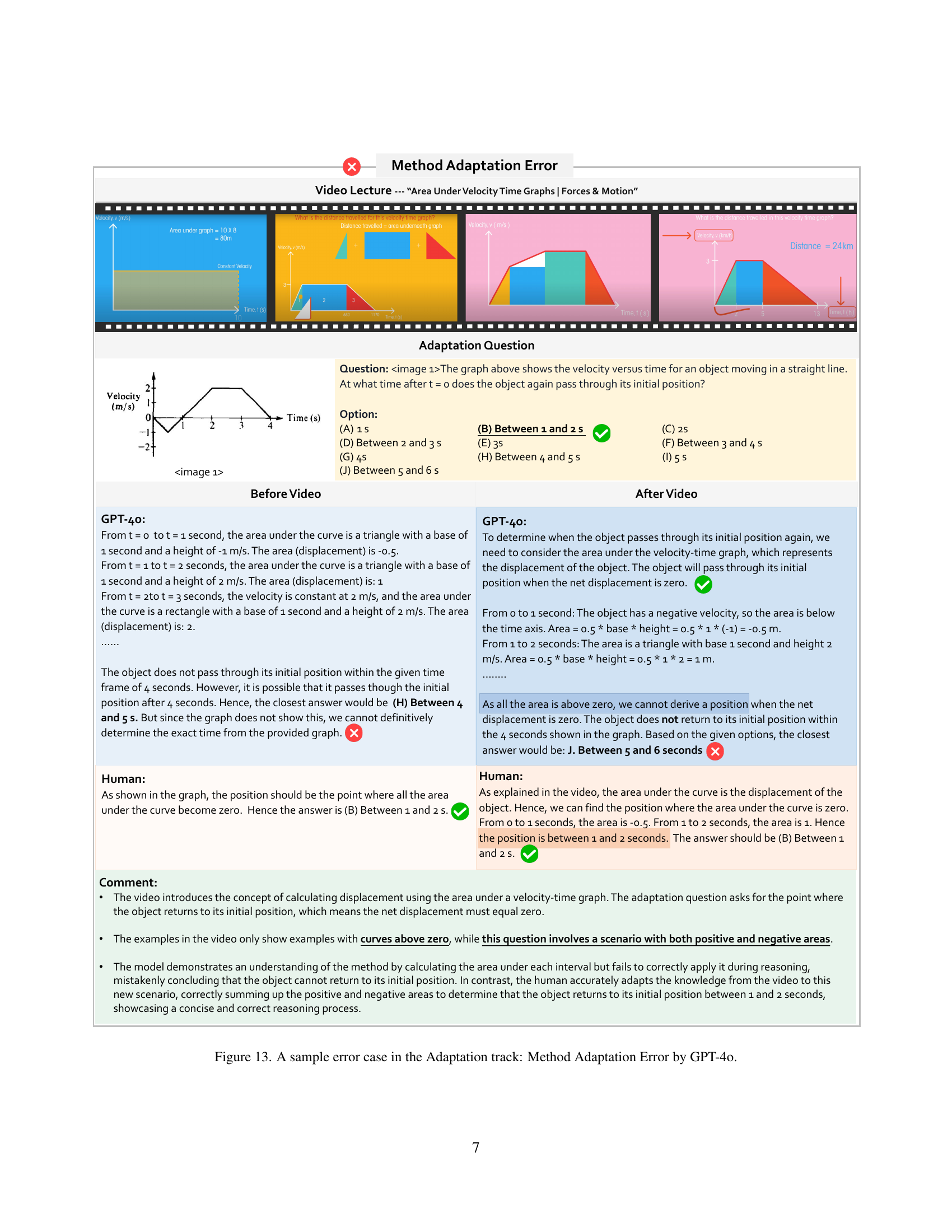

🔼 This figure presents a case where GPT-40, a large language model, demonstrates a method adaptation error during an adaptation task within the Video-MMMU benchmark. The task involves using knowledge from a video lecture on calculating displacement from velocity-time graphs. The question asks to determine the time at which an object returns to its initial position given a velocity-time graph showing both positive and negative velocities. GPT-40 initially displays some understanding of the concept of area under the curve representing displacement, but fails to correctly adapt this knowledge to a scenario with both positive and negative areas. In contrast, a human expert correctly solves the problem by calculating the net displacement, demonstrating the model’s limitation in adapting learned methods to new, similar situations.

read the caption

Figure 13: A sample error case in the Adaptation track: Method Adaptation Error by GPT-4o.

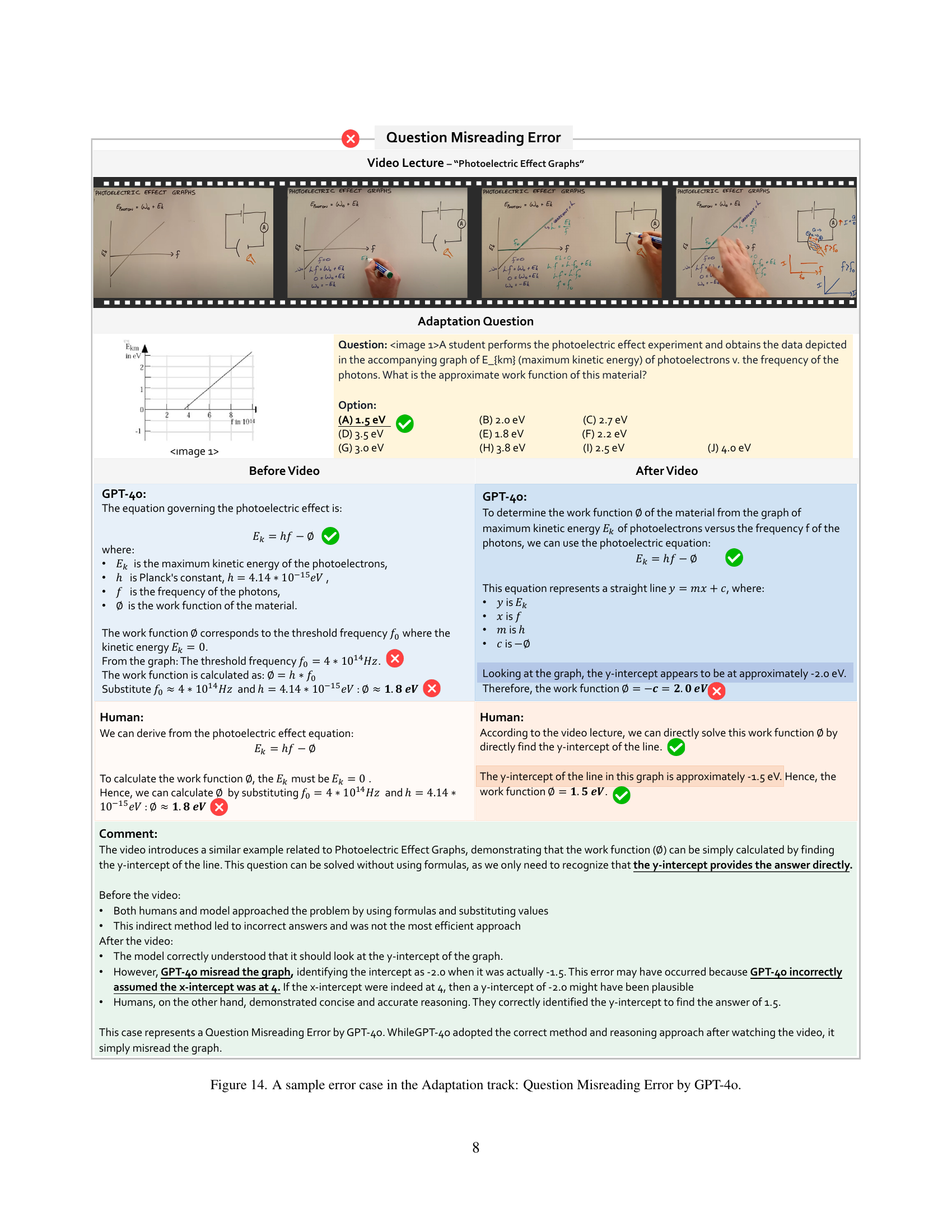

🔼 This figure shows a case where GPT-40 made an error in the Adaptation track due to misreading the question. The video lecture covered the photoelectric effect, and the question asked for the approximate work function of a material, given a graph of maximum kinetic energy of photoelectrons versus the frequency of photons. GPT-40 initially attempted to solve this using formulas and substituting values. However, after reviewing the video, GPT-40 correctly identified the need to find the y-intercept of the graph to find the answer. Yet, GPT-40 misread the y-intercept from the graph, resulting in an incorrect answer. This demonstrates that while the model may have learned the correct method after seeing the video, its performance was hampered by an error in visual interpretation. The human response correctly identifies the y-intercept and calculates the correct answer.

read the caption

Figure 14: A sample error case in the Adaptation track: Question Misreading Error by GPT-4o.

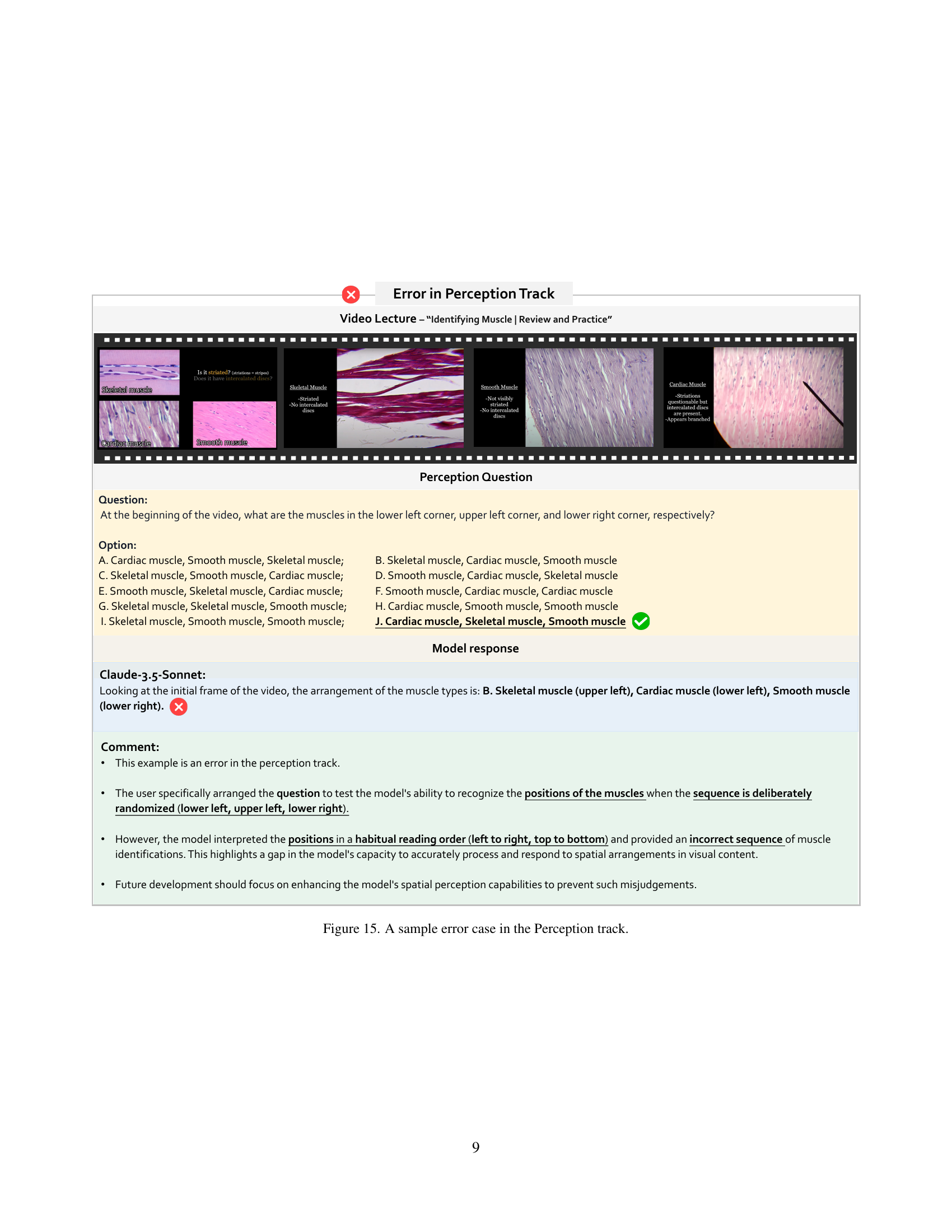

🔼 This figure shows a sample error case in the Perception track. The model is asked to identify three different types of muscle tissue in images from a video. The question is designed to test the model’s ability to identify the muscle tissue based on visual cues. The model fails to identify the muscles correctly in this instance, showing a weakness in its ability to perform accurate visual perception and recognition tasks. This error highlights that the model may not correctly perceive spatial arrangements in visual content, relying instead on a habitual reading order (left to right, top to bottom).

read the caption

Figure 15: A sample error case in the Perception track.

🔼 This figure showcases a typical error in the perception track, specifically highlighting how the model incorrectly identifies the ion channels in a neuron based on their color-coding in a video animation. The model’s response demonstrates a failure to correctly associate the colors (blue, orange/yellow, green) with the respective ion channels (sodium, mechanically-gated, potassium) as accurately depicted in the video’s visual elements. The model’s response indicates confusion in understanding the visual cues and their correlation to the correct labels.

read the caption

Figure 16: A sample error case in the Perception track.

🔼 This figure showcases a specific instance where a large language model (LLM) exhibited an error in the comprehension track of the Video-MMMU benchmark. The task involved understanding and applying a breadth-first search (BFS) algorithm to construct a spanning tree within a graph. The model correctly identified that a BFS involves horizontal exploration before vertical exploration. However, the model made mistakes when the starting node (root node) was changed from node A to node F. The model did not correctly identify which nodes were directly connected to the new root node and, as a result, incorrectly determined the nodes located at level 3 of the BFS spanning tree. This error highlights the challenges faced by LLMs in transferring their understanding of algorithms and problem-solving strategies to novel scenarios, even with minor input changes.

read the caption

Figure 17: A sample error case in the Comprehension track.

🔼 The figure showcases a comprehension error made by Claude-3.5-Sonnet. The model incorrectly uses the formula

t = (2 * Voy) / gto calculate the time of flight for a projectile launched from a cliff at an angle of 30 degrees. This formula is only valid for projectiles launched from ground level and returning to it. The correct approach, demonstrated in the video lecture, involves using the quadratic equationy(t) = Yo + Voy * t - (1/2) * g * t²to account for the different launch and landing heights. This highlights the model’s failure to fully grasp the problem-solving strategy and adapt it to a slightly modified scenario.read the caption

Figure 18: A sample error case in the Comprehension track.

🔼 This figure showcases a successful instance of knowledge acquisition from a video lecture, demonstrated by the Claude-3.5-Sonnet model. Initially, the model incorrectly calculated the maximum flow in a network using the Ford-Fulkerson algorithm. However, after viewing a video explaining the algorithm and its steps, the model revised its approach. It correctly identified augmenting paths, respected capacity constraints, and applied flow conservation rules to arrive at the accurate solution. This highlights the model’s ability to learn and utilize the information presented in the video, thereby improving its performance in solving network flow problems.

read the caption

Figure 19: A Wrong-to-Right example of Claude-3.5-Sonnet in the Adaptation track.

🔼 This figure shows a successful knowledge acquisition example from a video lecture on thin film interference. Claude-3.5-Sonnet initially incorrectly calculates the film thickness needed for maximum constructive interference, due to a misunderstanding of phase shifts at the boundaries between materials with different refractive indices. After watching the video, however, the model correctly identifies the phase shift based on the relative refractive indices and applies the correct formula for constructive interference to determine the proper film thickness. This demonstrates the model’s ability to learn from video and correct its understanding of complex physics principles.

read the caption

Figure 20: A Wrong-to-Right example of Claude-3.5-Sonnet in the Adaptation track.

More on tables

| Model | Overall | Results by Track | Results by Discipline | |||||||

| Perception | Comprehension | Adaptation | Art. | Biz. | Sci. | Med. | Hum. | Eng. | ||

| Random Choice | 14.00 | 12.00 | 14.00 | 16.00 | 11.11 | 12.88 | 12.12 | 22.48 | 10.48 | 13.57 |

| Human Expert | 74.44 | 84.33 | 78.67 | 60.33 | 80.95 | 78.79 | 74.24 | 70.54 | 84.76 | 69.91 |

| Proprietary LMMs | ||||||||||

| Gemini 1.5 Flash [32] | 49.78 | 57.33 | 49.00 | 43.00 | 63.49 | 53.03 | 43.18 | 49.61 | 59.05 | 45.72 |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro [32] | 53.89 | 59.00 | 53.33 | 49.33 | 57.14 | 59.09 | 49.10 | 57.42 | 58.10 | 50.31 |

| GPT-4o [27] | 61.22 | 66.00 | 62.00 | 55.67 | 69.52 | 66.88 | 51.55 | 64.76 | 69.52 | 57.13 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet [1] | 65.78 | 72.00 | 69.67 | 55.67 | 66.67 | 75.00 | 56.06 | 58.14 | 75.24 | 66.08 |

| Open-source LMMs | ||||||||||

| VILA1.5-8B [19] | 20.89 | 20.33 | 17.33 | 25.00 | 34.92 | 14.39 | 19.70 | 19.38 | 21.91 | 21.53 |

| LongVA-7B [48] | 23.98 | 24.00 | 24.33 | 23.67 | 41.27 | 20.46 | 21.97 | 24.03 | 23.81 | 23.01 |

| Llama-3.2-11B [23] | 30.00 | 35.67 | 32.33 | 22.00 | 39.68 | 28.79 | 21.21 | 35.66 | 33.33 | 28.91 |

| LLaVA-OneVision-7B [15] | 33.89 | 40.00 | 31.00 | 30.67 | 49.21 | 29.55 | 34.85 | 31.78 | 46.67 | 29.20 |

| VILA1.5-40B [19] | 34.00 | 38.67 | 30.67 | 32.67 | 57.14 | 27.27 | 23.49 | 37.99 | 41.91 | 32.45 |

| LLaVA-Video-7B [49] | 36.11 | 41.67 | 33.33 | 33.33 | 65.08 | 34.09 | 32.58 | 42.64 | 45.71 | 27.43 |

| InternVL2-8B [6] | 37.44 | 47.33 | 33.33 | 31.67 | 55.56 | 34.09 | 30.30 | 34.11 | 41.91 | 38.05 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B [12] | 41.78 | 51.67 | 40.00 | 33.67 | 47.62 | 37.88 | 36.36 | 36.43 | 49.52 | 43.95 |

| LLaVA-OneVision-72B [15] | 48.33 | 59.67 | 42.33 | 43.00 | 61.91 | 46.21 | 40.15 | 54.26 | 60.00 | 43.95 |

| LLaVA-Video-72B [49] | 49.67 | 59.67 | 46.00 | 43.33 | 69.84 | 44.70 | 41.67 | 58.92 | 57.14 | 45.13 |

| Aria [16] | 50.78 | 65.67 | 46.67 | 40.00 | 71.43 | 47.73 | 44.70 | 58.92 | 62.86 | 43.66 |

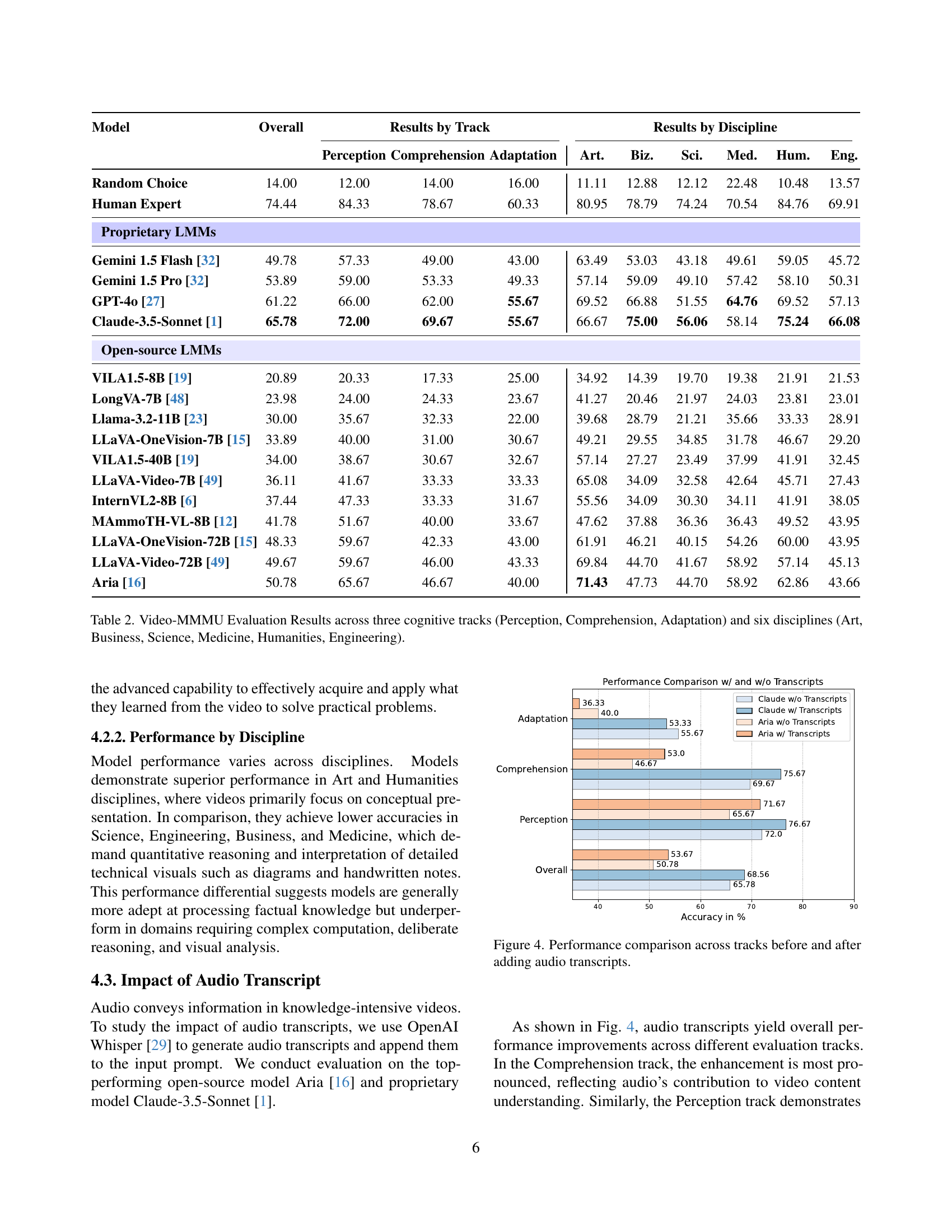

🔼 Table 2 presents the performance of various Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) on the Video-MMMU benchmark. The benchmark assesses knowledge acquisition from videos across three cognitive levels (Perception, Comprehension, and Adaptation), each representing increasing cognitive complexity. The results are broken down by both cognitive track and by six different disciplines (Art, Business, Science, Medicine, Humanities, and Engineering) included in the benchmark’s video dataset. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of model strengths and weaknesses across various tasks and subject domains.

read the caption

Table 2: Video-MMMU Evaluation Results across three cognitive tracks (Perception, Comprehension, Adaptation) and six disciplines (Art, Business, Science, Medicine, Humanities, Engineering).

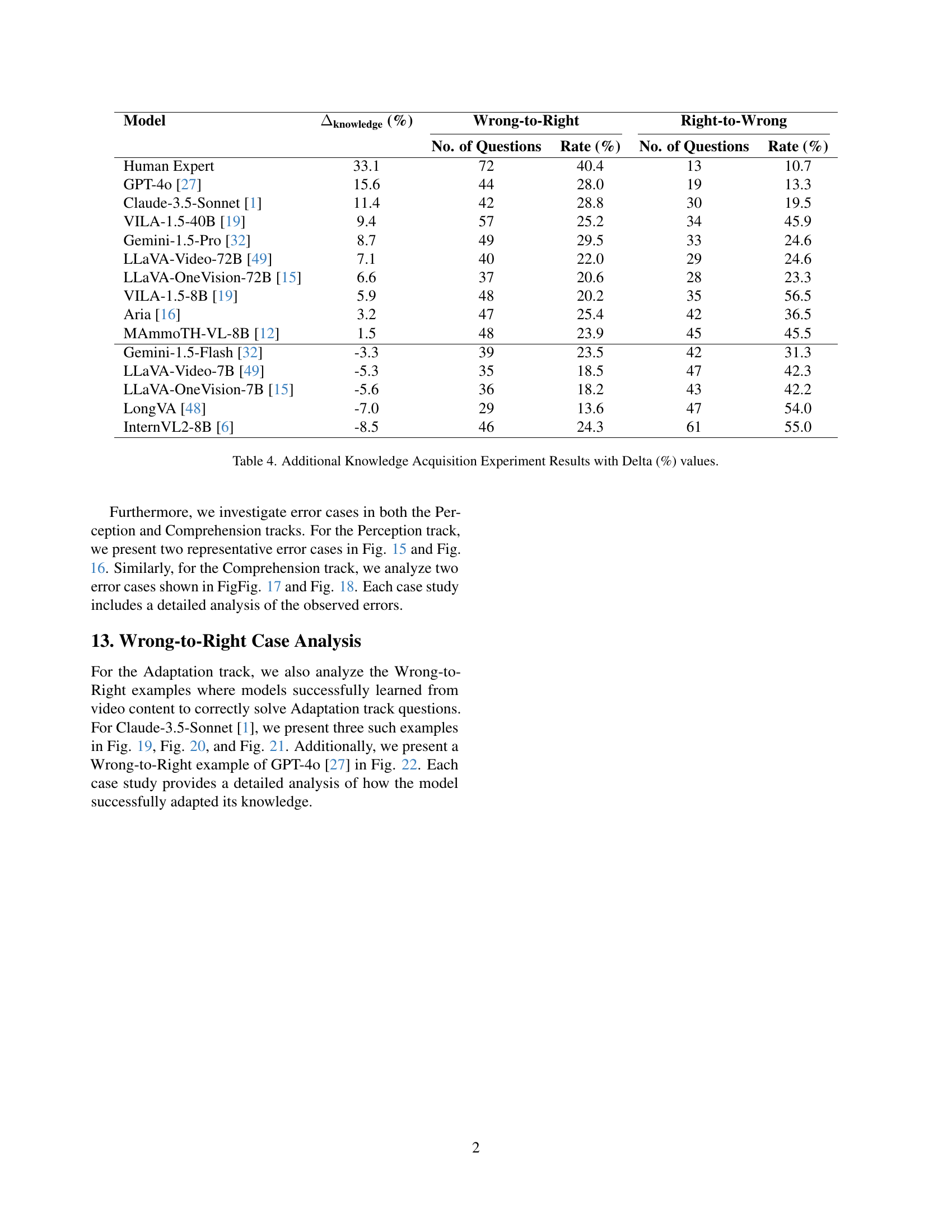

| Discipline | Subjects |

| Art | Art History, Art Theory, Design, Music |

| Business | Accounting, Economics, Finance, Manage, Marketing |

| Science | Biology, Chemistry, Geography, Math, Physics |

| Medicine | Basic Medical Science, Clinical Medicine, Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, Pharmacy, Public Health |

| Humanities | History, Literature, Psychology, Sociology |

| Engineering | Agriculture, Architecture and Engineering, Computer Science, Electronics, Energy and Power, Materials, Mechanical Engineering |

🔼 This table lists the 30 subjects that are included in the Video-MMMU dataset, categorized into six academic disciplines: Art, Business, Medicine, Science, Humanities, and Engineering. Each discipline contains a subset of the 30 subjects, providing a breakdown of the dataset’s coverage across various fields of study.

read the caption

Table 3: Subjects categorized under six disciplines.

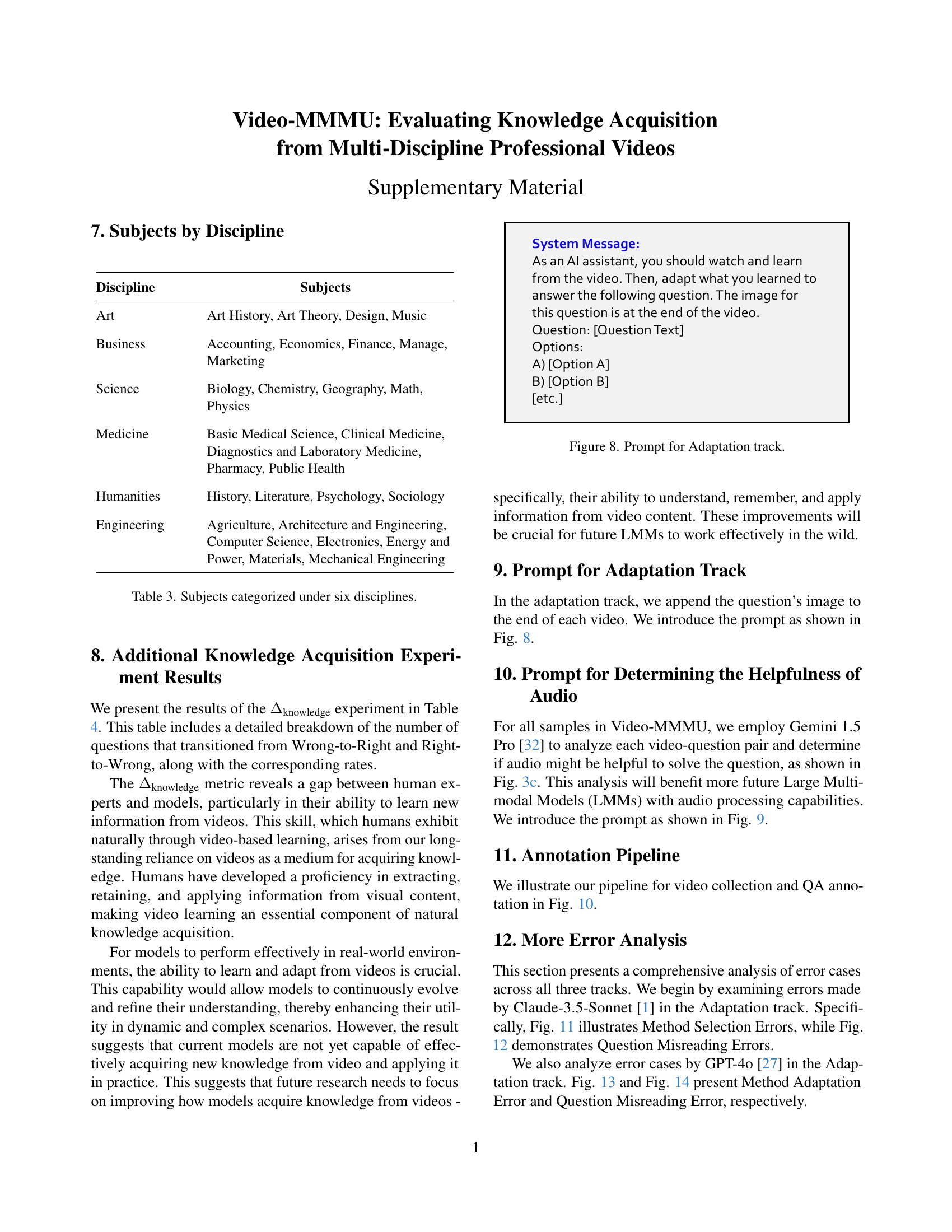

| Model | (%) | Wrong-to-Right | Right-to-Wrong | ||

| No. of Questions | Rate (%) | No. of Questions | Rate (%) | ||

| Human Expert | 33.1 | 72 | 40.4 | 13 | 10.7 |

| GPT-4o [27] | 15.6 | 44 | 28.0 | 19 | 13.3 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet [1] | 11.4 | 42 | 28.8 | 30 | 19.5 |

| VILA-1.5-40B [19] | 9.4 | 57 | 25.2 | 34 | 45.9 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro [32] | 8.7 | 49 | 29.5 | 33 | 24.6 |

| LLaVA-Video-72B [49] | 7.1 | 40 | 22.0 | 29 | 24.6 |

| LLaVA-OneVision-72B [15] | 6.6 | 37 | 20.6 | 28 | 23.3 |

| VILA-1.5-8B [19] | 5.9 | 48 | 20.2 | 35 | 56.5 |

| Aria [16] | 3.2 | 47 | 25.4 | 42 | 36.5 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B [12] | 1.5 | 48 | 23.9 | 45 | 45.5 |

| Gemini-1.5-Flash [32] | -3.3 | 39 | 23.5 | 42 | 31.3 |

| LLaVA-Video-7B [49] | -5.3 | 35 | 18.5 | 47 | 42.3 |

| LLaVA-OneVision-7B [15] | -5.6 | 36 | 18.2 | 43 | 42.2 |

| LongVA [48] | -7.0 | 29 | 13.6 | 47 | 54.0 |

| InternVL2-8B [6] | -8.5 | 46 | 24.3 | 61 | 55.0 |

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the knowledge acquisition results for various models in the Adaptation track of the Video-MMMU benchmark. For each model, it shows the overall knowledge gain (Δknowledge), calculated as the percentage improvement in accuracy on Adaptation questions after watching relevant videos, compared to before watching the videos. Furthermore, it provides a more granular analysis by showing the number and percentage of questions where models initially answered incorrectly but corrected their answer after watching the video (Wrong-to-Right Rate) and vice versa (Right-to-Wrong Rate). This allows a more nuanced understanding of model learning beyond the simple accuracy change, revealing both the ability to learn from the video and the tendency to lose existing knowledge. The data includes both open-source and proprietary Large Multimodal Models (LMMs), providing a comprehensive comparison of their knowledge acquisition capabilities.

read the caption

Table 4: Additional Knowledge Acquisition Experiment Results with Delta (%) values.

Full paper#