TL;DR#

Current Large Language Models (LLMs) excel in various domains like mathematics and logic, but their physics-based reasoning abilities remain largely unexplored. Existing physics benchmarks suffer from oversimplification and neglect step-by-step evaluation, hindering a thorough understanding of model capabilities and limitations. This paper introduces PhysReason, a comprehensive benchmark with 1200 problems of varying difficulty levels, designed to accurately assess the physics-based reasoning prowess of LLMs. The problems feature multi-step reasoning, and 81% include diagrams, assessing visual-textual comprehension.

To effectively evaluate model performance, the authors propose a new evaluation framework called Physics Solution Auto Scoring (PSAS), which includes both answer-level and step-level evaluations. The results reveal that even top-performing models achieve less than 60% accuracy, highlighting the significant challenges in physics-based reasoning. The step-level analysis identifies critical bottlenecks like theorem application, process understanding, and calculation. This systematic evaluation approach and the comprehensive benchmark dataset provided by the authors are significant contributions to the field, prompting further research and advancements in LLMs’ ability to reason within the realm of physics.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and physics because it introduces PhysReason, a novel benchmark for evaluating physics-based reasoning in large language models (LLMs). This addresses a critical gap in current LLM evaluation, focusing on multi-step reasoning and visual-textual integration. The findings reveal key limitations in current LLMs’ abilities and pave the way for developing more sophisticated models capable of true physics-based understanding. PhysReason provides valuable insights into how LLMs approach complex problems involving physics principles, fostering further innovation and development of more robust and reliable models.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 shows an example problem from the PhysReason benchmark dataset. The problem involves a ball suspended from a point O by a string, colliding with an identical ball on a table below. The figure displays the diagram of the problem setup, the context which describes the setup, and sub-questions that need to be answered. The solution is not entirely shown in the figure, but it does show an example of a ‘Step Analysis’ in order to demonstrate the structure of the answer. The full solution with annotations for this problem, along with annotations for all problems in the benchmark dataset, is available in Appendix D. PhysReason focuses on multi-step physics reasoning problems that often involve diagrams and require application of multiple physics theorems.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of example from our PhysReason benchmark. Due to space constraints, only key components are shown. Please refer to Appendix D for complete annotations.

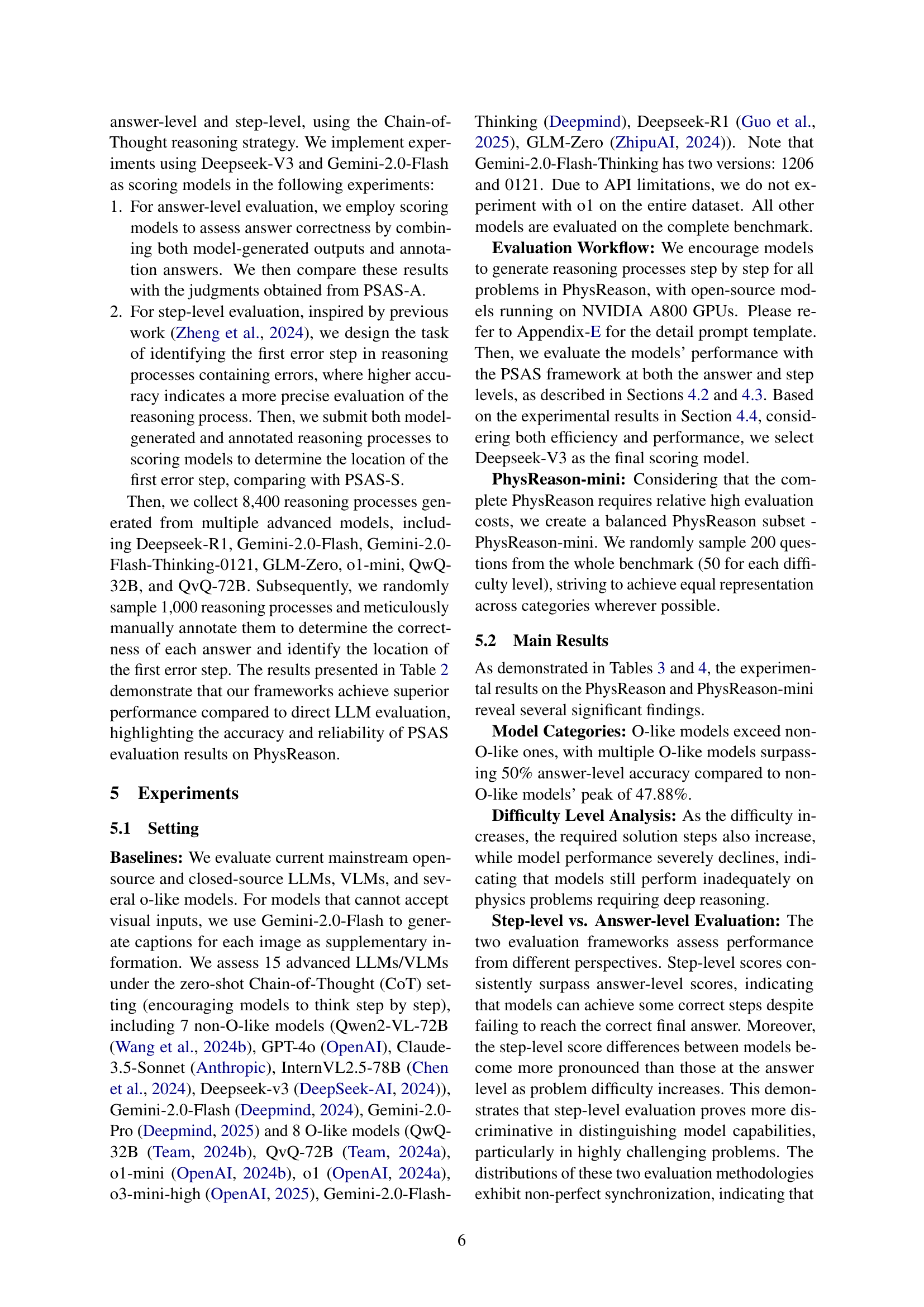

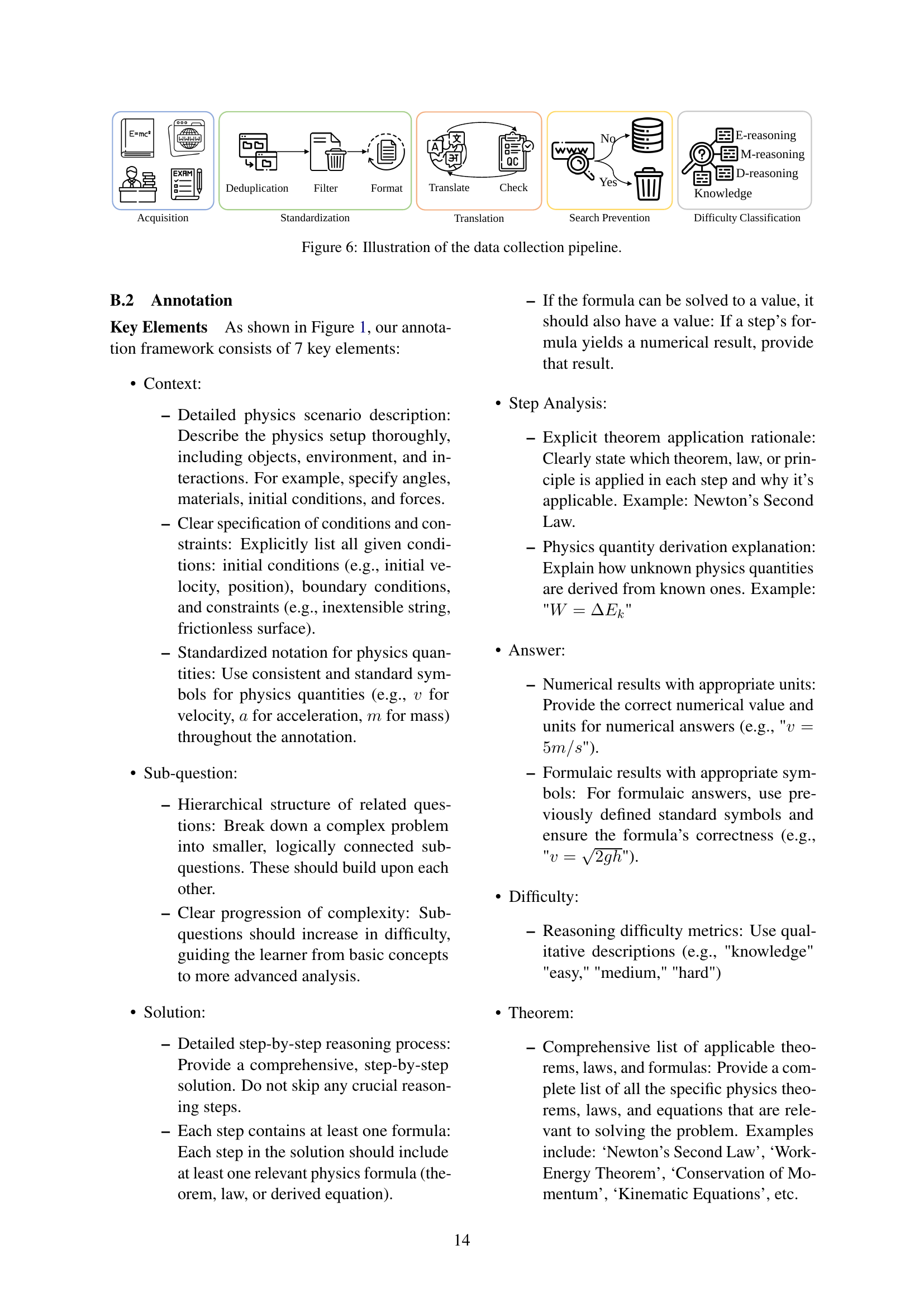

| Model | Input | Knowledge | Easy | Medium | Hard | Avg. |

| Non-O-like Models | ||||||

| Qwen2VL-72B | Q, I | 25.40 | 27.00 | 11.4 | 8.5 | 18.07 |

| InternVL2.5-78B | Q, I | 37.90 | 20.60 | 18.14 | 7.97 | 21.15 |

| GPT-4o | Q, I | 51.12 | 31.95 | 20.75 | 12.54 | 29.09 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet | Q, I | 49.00 | 40.43 | 23.45 | 12.33 | 31.3 |

| Deepseek-V3-671B | Q, IC | 56.60 | 40.97 | 22.22 | 14.61 | 33.6 |

| Gemini-2.0-Flash | Q, I | 67.80 | 52.10 | 40.00 | 23.19 | 46.52 |

| Gemini-2.0-Pro | Q, I | 69.32 | 53.67 | 44.98 | 26.24 | 48.55 |

| O-like Models | ||||||

| o1-mini | Q, IC | 54.80 | 30.33 | 15.41 | 7.92 | 27.11 |

| QvQ-72B | Q, I | 51.17 | 37.10 | 29.83 | 22.13 | 35.06 |

| QwQ-32B | Q, IC | 64.4 | 50.07 | 38.88 | 27.45 | 45.20 |

| Gemini-2.0-T† | Q, I | 71.47 | 49.97 | 36.83 | 22.97 | 45.42 |

| GLM-Zero | Q, IC | 72.70 | 50.17 | 43.42 | 24.70 | 47.75 |

| o1 | Q, I | 72.47 | 53.37 | 49.31 | 25.32 | 50.12 |

| o3-mini-high | Q, IC | 71.10 | 63.20 | 47.02 | 31.93 | 53.31 |

| Gemini-2.0-T∗ | Q, I | 76.33 | 56.87 | 51.85 | 32.61 | 54.42 |

| Deepseek-R1 | Q, IC | 85.17 | 60.77 | 47.24 | 33.23 | 56.60 |

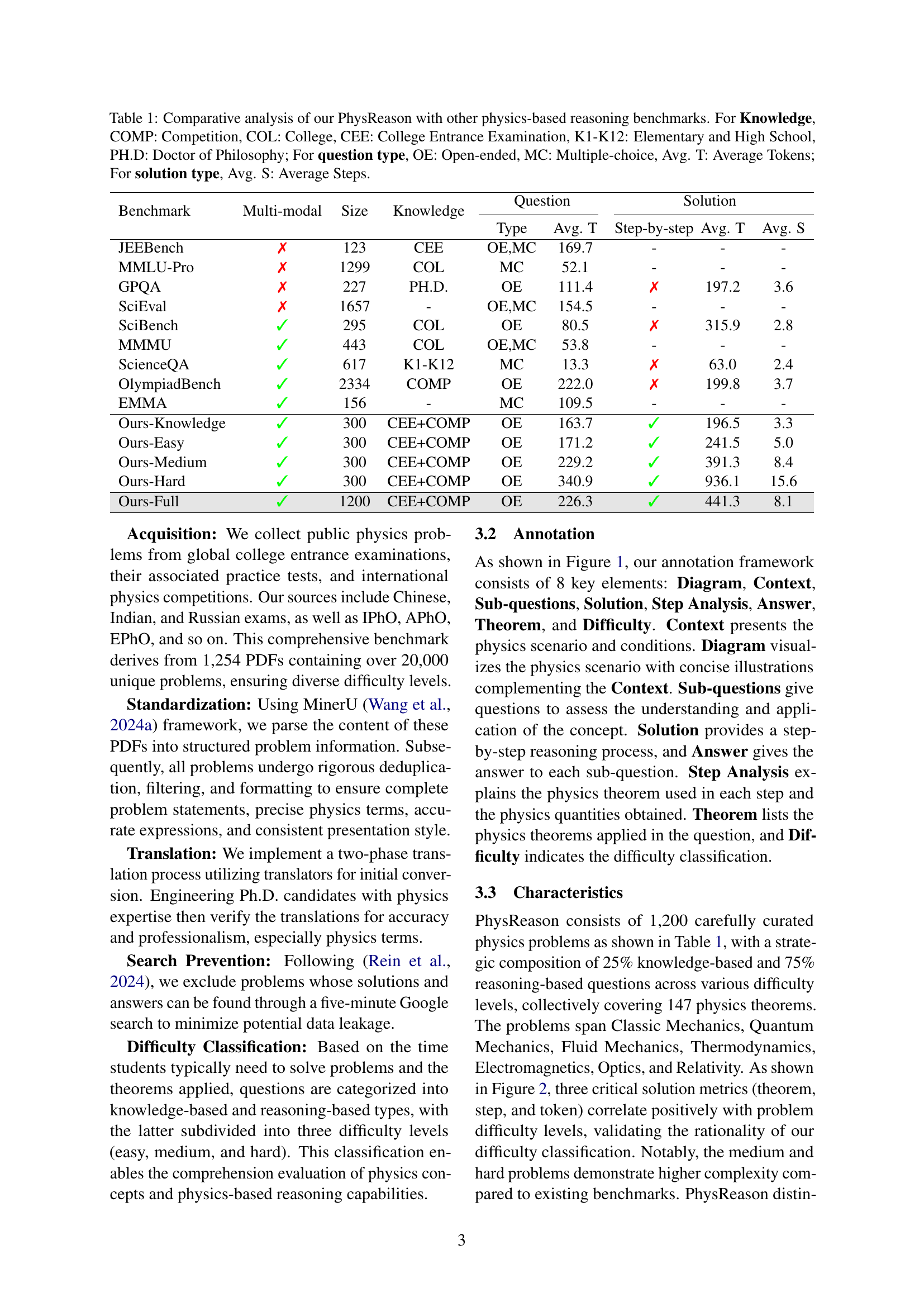

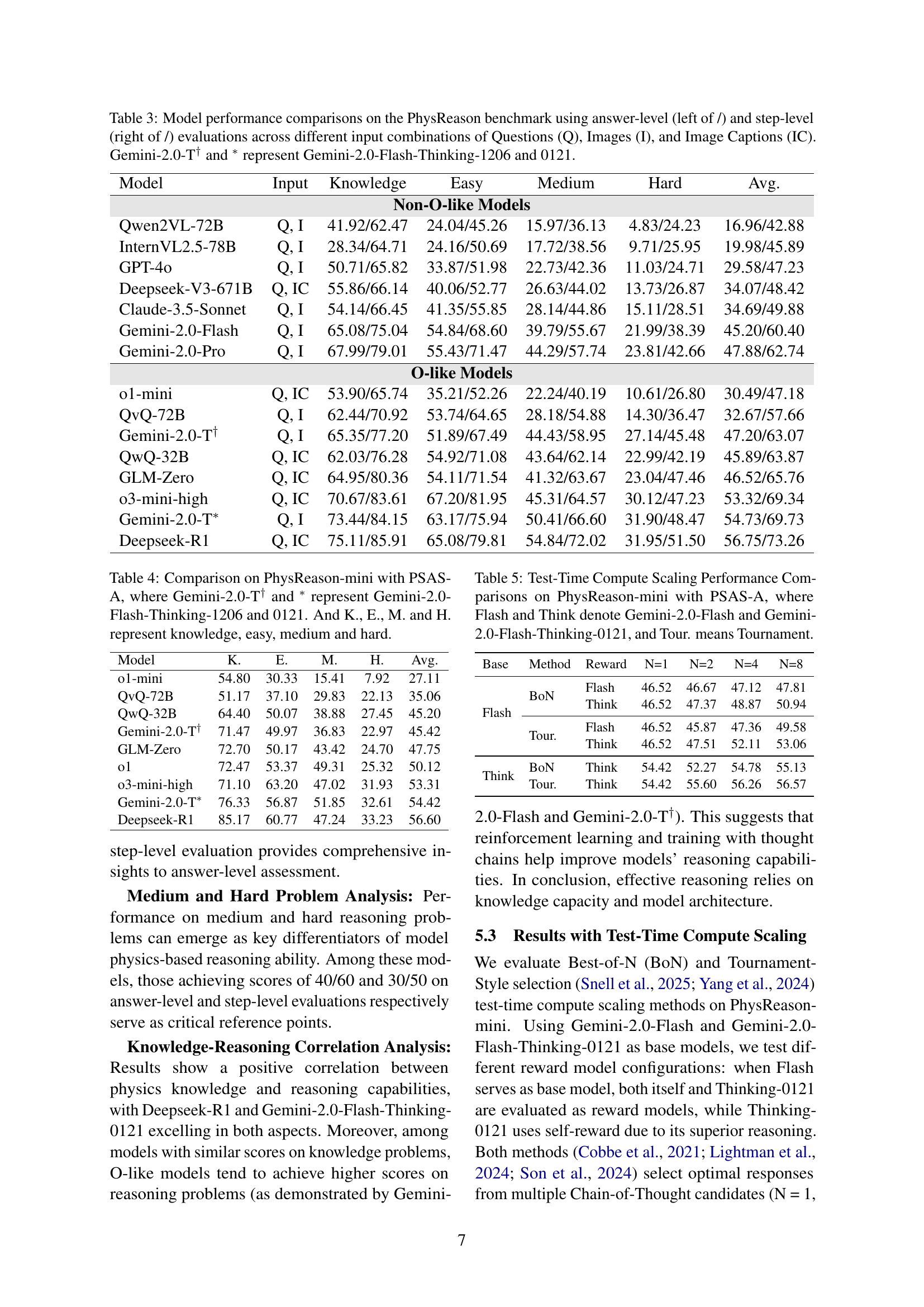

🔼 This table compares the PhysReason benchmark with other physics-based reasoning benchmarks across several key features. These features include the size of the benchmark (number of problems), the type of knowledge assessed (competition problems, college-level, college entrance exams, K-12, or PhD-level), the type of questions (open-ended or multiple choice), the average number of tokens in the questions, whether the benchmark includes multimodal questions (with diagrams or not), the average number of steps in the solution, and the average number of tokens in the solution.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparative analysis of our PhysReason with other physics-based reasoning benchmarks. For Knowledge, COMP: Competition, COL: College, CEE: College Entrance Examination, K1-K12: Elementary and High School, PH.D: Doctor of Philosophy; For question type, OE: Open-ended, MC: Multiple-choice, Avg. T: Average Tokens; For solution type, Avg. S: Average Steps.

In-depth insights#

Physics Reasoning Benchmarks#

Physics reasoning benchmarks are crucial for evaluating the progress of artificial intelligence (AI) in solving physics problems. Existing benchmarks often have limitations, such as oversimplification of reasoning processes and neglecting step-level evaluations. Ideally, a robust benchmark should feature complex, multi-step problems that require the application of multiple physics principles, incorporate diagrams and visual reasoning, and provide comprehensive step-level evaluations to pinpoint areas where AI models struggle. This approach would enable a deeper understanding of the AI model’s strengths and weaknesses and allows for better identification of bottlenecks in the reasoning process, such as physics theorem application, physics process understanding, calculation, and physics condition analysis. A well-designed benchmark will also help guide the development of more sophisticated and robust AI models capable of performing complex physics-based reasoning. The ultimate goal is to build AI systems that can not only solve physics problems but also genuinely understand the underlying physical principles. This requires moving beyond simple numerical answers and focusing on the entire reasoning process. The development of such benchmarks is an active and important area of AI research.

LLM Evaluation Framework#

A robust LLM evaluation framework is crucial for assessing the capabilities of large language models, especially in specialized domains like physics. Such a framework should move beyond simple accuracy metrics, incorporating more nuanced evaluations. It should consider the reasoning process, not just the final answer, perhaps by analyzing the steps taken and identifying specific bottlenecks in the model’s thinking. A multi-faceted approach, examining different aspects of model performance, is key. This might include evaluating the model’s ability to handle diverse problem types, its robustness to varying levels of difficulty, its reliance on external knowledge sources, and its efficiency in terms of computational resources. Developing standardized benchmarks and evaluation protocols is essential for comparing different LLMs fairly. The evaluation framework needs to be easily adaptable and scalable to accommodate the ever-evolving nature of LLMs and the expanding scope of tasks they are expected to handle. Furthermore, the framework must be designed to encourage ongoing improvements in the capabilities of large language models and promote transparency and reproducibility in research.

PhysReason Analysis#

A thorough PhysReason analysis would involve a multifaceted investigation. First, it needs to quantitatively assess model performance across various problem types and difficulty levels, comparing results against existing benchmarks. Second, it should qualitatively analyze model strengths and weaknesses, identifying specific areas where models excel or struggle (e.g., theorem application, process understanding, calculations). Third, a crucial aspect would be to investigate error patterns to understand why models fail and what types of reasoning challenges they face. A strong analysis will then relate these findings to model architecture and training methodologies, providing insights into how to improve future models. Finally, the study should discuss limitations and potential biases of PhysReason itself, ensuring the results’ generalizability and validity within the broader context of LLM capabilities.

Benchmark Limitations#

A significant limitation of many physics-based reasoning benchmarks, including the one discussed, is their focus on idealized scenarios. Real-world physics problems are messy, incorporating factors like friction, air resistance, and complex interactions not easily modeled in simplified benchmark tasks. This discrepancy limits the ability of benchmarks to accurately assess a model’s performance in practical applications. Another crucial limitation is the over-reliance on final answers in evaluating model performance. This approach fails to capture the nuances of the problem-solving process, neglecting intermediate steps and reasoning strategies. A more comprehensive evaluation should incorporate a step-by-step analysis of the model’s approach, providing detailed insights into its strengths and weaknesses at each stage. Furthermore, the current benchmarks often lack the multi-modality inherent in real-world scenarios. Physics problems frequently involve diagrams, graphs, and other visual elements that contribute significantly to the problem-solving process. Ignoring these visual aspects diminishes the benchmark’s ability to fully evaluate models’ overall reasoning capabilities. Lastly, the generalizability and scalability of the benchmarks are open questions. Can these benchmarks adequately evaluate models’ performance across a wide spectrum of physics problems, beyond those specifically included in the dataset? Future work should focus on creating more realistic, comprehensive, and scalable benchmarks that effectively bridge the gap between idealized testing environments and real-world physics applications.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this physics reasoning benchmark could explore several key areas. Expanding the benchmark’s scope to encompass more diverse problem types and real-world scenarios is crucial, moving beyond idealized physics settings to better reflect the complexity of real-world applications. Improving the evaluation framework is also vital; current methods, while effective, are computationally expensive and could benefit from optimized approaches that maintain accuracy while reducing resource needs. Incorporating more sophisticated reasoning models that can better handle multi-step reasoning and uncertainty would enhance the benchmark’s ability to discriminate between high-performing models. Finally, investigating the relationship between model architecture, training data, and performance on physics reasoning tasks is essential for advancing LLMs’ capabilities in this domain. Focus on addressing the specific bottlenecks identified in the paper (theorem application, process understanding, calculation, and condition analysis) would provide targeted improvements. By pursuing these directions, the benchmark can continue to evolve as a valuable tool for advancing the field of AI, driving significant progress in physics-based reasoning capabilities of large language models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

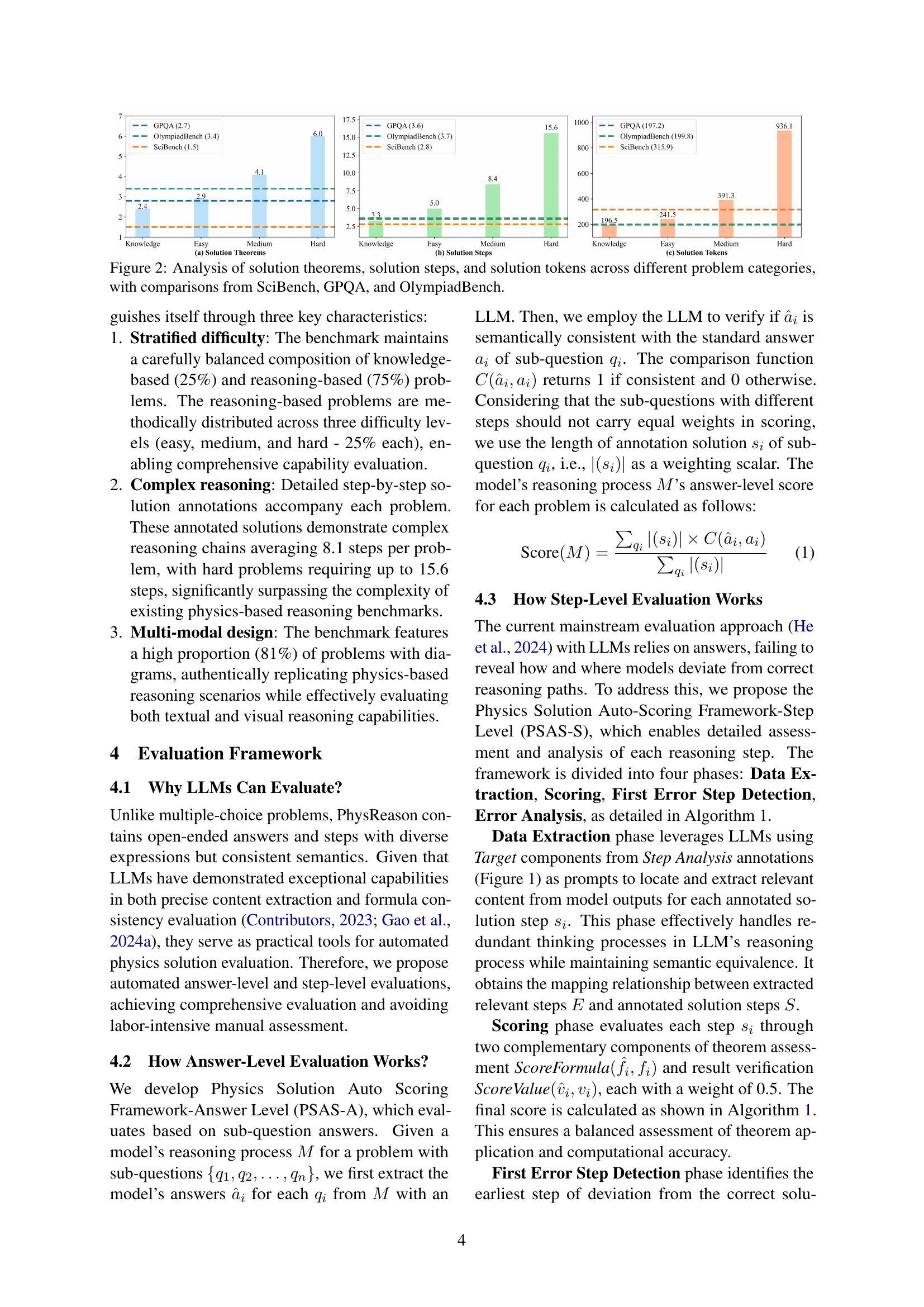

🔼 This figure compares the number of theorems, steps, and tokens used in solving problems across different difficulty levels (Knowledge, Easy, Medium, Hard) in the PhysReason benchmark. It also includes a comparison with three other physics-based reasoning benchmarks: SciBench, GPQA, and OlympiadBench, showing how PhysReason problems are more complex, requiring more steps and tokens to solve, especially at the harder levels. The purpose is to illustrate the increased difficulty and complexity of physics-based reasoning problems in PhysReason compared to existing benchmarks.

read the caption

Figure 2: Analysis of solution theorems, solution steps, and solution tokens across different problem categories, with comparisons from SciBench, GPQA, and OlympiadBench.

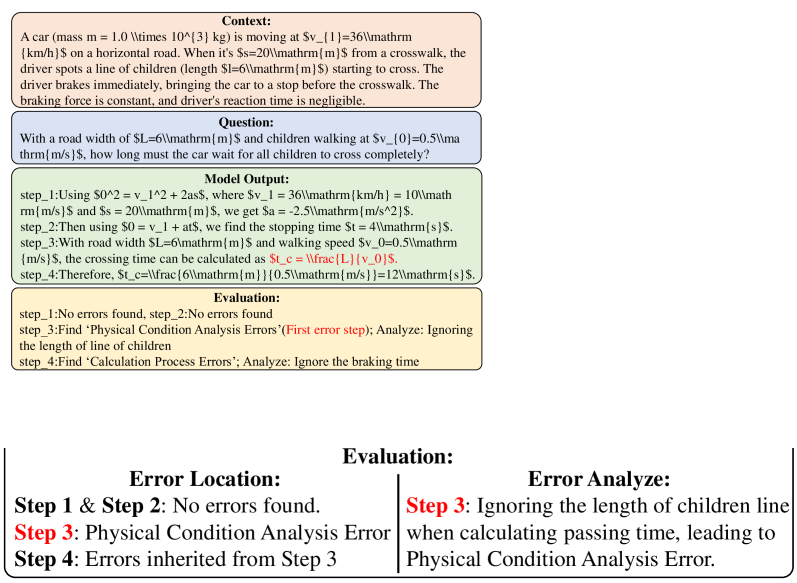

🔼 This figure showcases a step-level evaluation example generated using the Physics Solution Auto-Scoring Framework (PSAS-S). PSAS-S is an automated evaluation method designed to assess the accuracy of reasoning steps within a physics problem solution. The example demonstrates how PSAS-S extracts relevant information from a language model’s response, compares it against the correct solution step-by-step, and provides an error analysis if necessary. The figure highlights the detailed breakdown of the evaluation process, showing specific steps identified as correct or incorrect and indicating the error type. This illustrative example helps to clarify how PSAS-S achieves a comprehensive step-level evaluation accuracy, exceeding 98% in the experimental results.

read the caption

Figure 3: Step-level evaluation example obtained from PSAS-S framework.

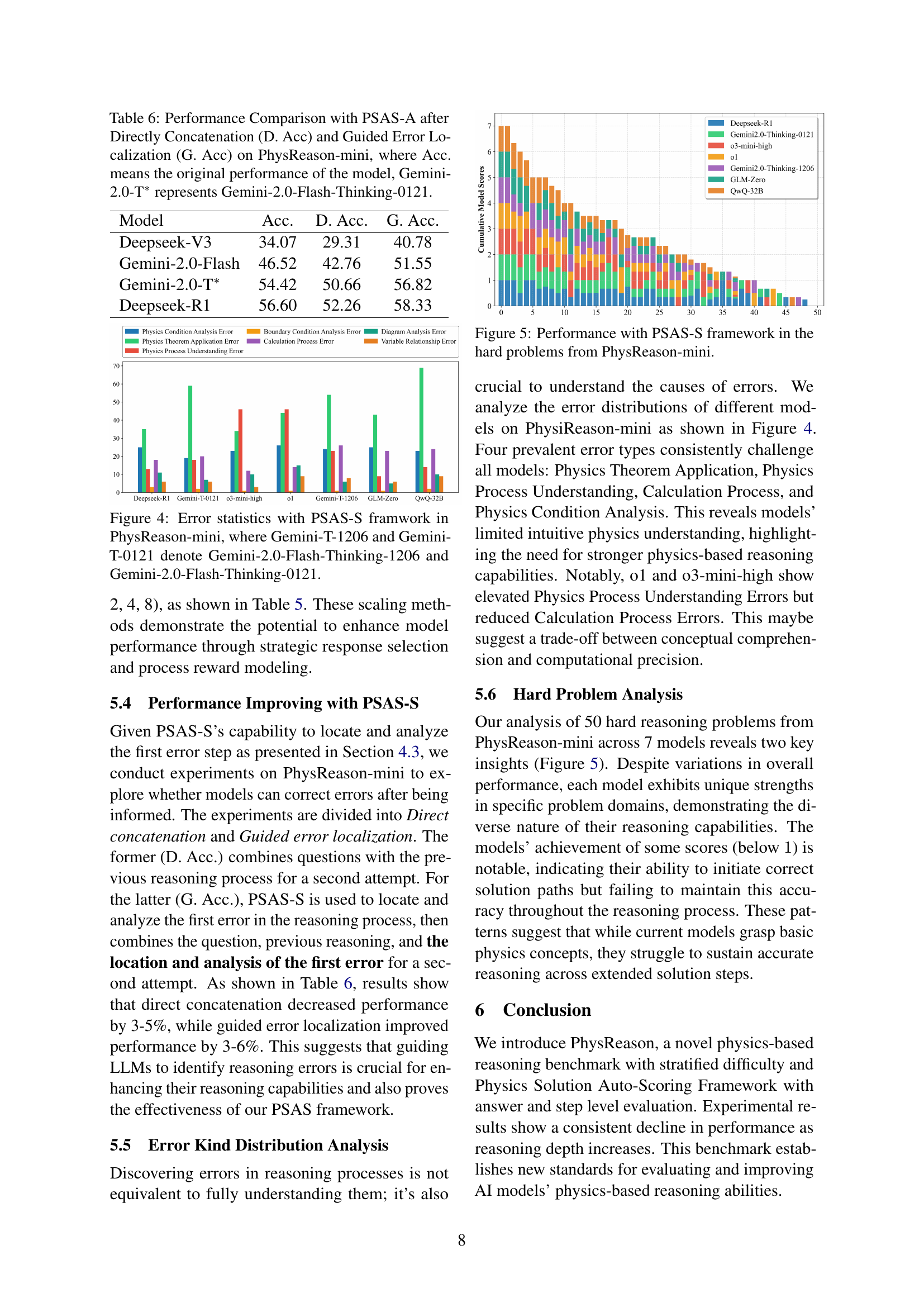

🔼 Figure 4 presents a bar chart visualizing the distribution of various error types identified by the Physics Solution Auto-Scoring Framework - Step Level (PSAS-S) within the PhysReason-mini benchmark. The error types are: Diagram Analysis Errors, Physics Theorem Application Errors, Physics Process Understanding Errors, Physics Condition Analysis Errors, Calculation Process Errors, Boundary Condition Analysis Errors, and Variable Relationship Errors. The chart shows the frequency or percentage of each error type for several different language models. These models include Deepseek-R1, Gemini 2.0 Flash-Thinking-0121, Gemini 2.0 Flash-Thinking-1206, GLM-Zero, QwQ-32B, and 01-mini. The figure highlights the types of errors that each model tends to make more frequently, offering insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each model’s physics-based reasoning capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 4: Error statistics with PSAS-S framwork in PhysReason-mini, where Gemini-T-1206 and Gemini-T-0121 denote Gemini-2.0-Flash-Thinking-1206 and Gemini-2.0-Flash-Thinking-0121.

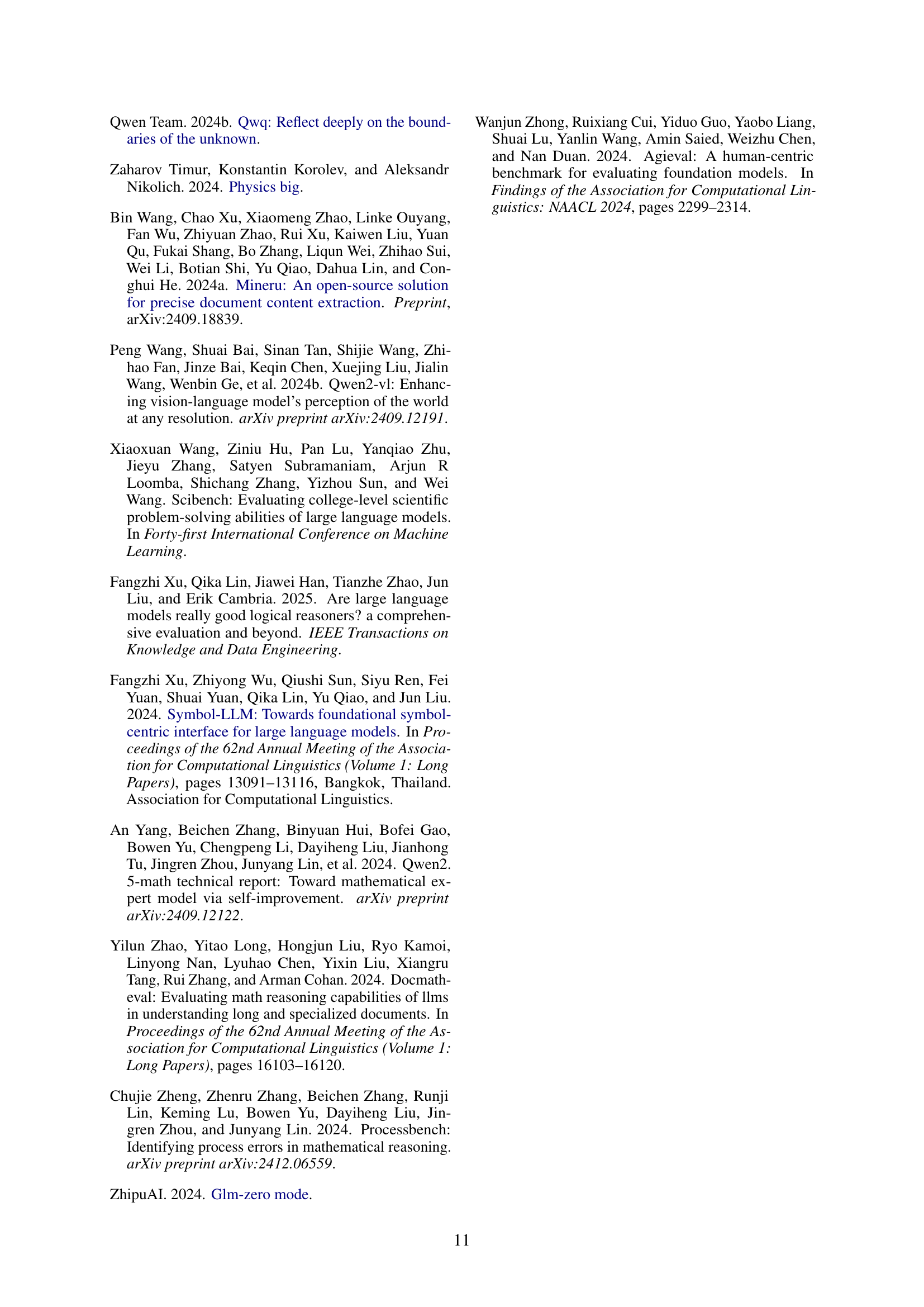

🔼 Figure 5 is a bar chart showing the performance of different large language models (LLMs) on the hard problems within the PhysReason-mini benchmark, using the Physics Solution Auto-Scoring Framework Step Level (PSAS-S) evaluation method. The chart displays the cumulative scores for each model, highlighting their ability to accurately solve the complex, multi-step reasoning tasks presented in these challenging physics problems. Models are ranked by performance, allowing for easy comparison of their strengths and weaknesses in physics-based reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 5: Performance with PSAS-S framework in the hard problems from PhysReason-mini.

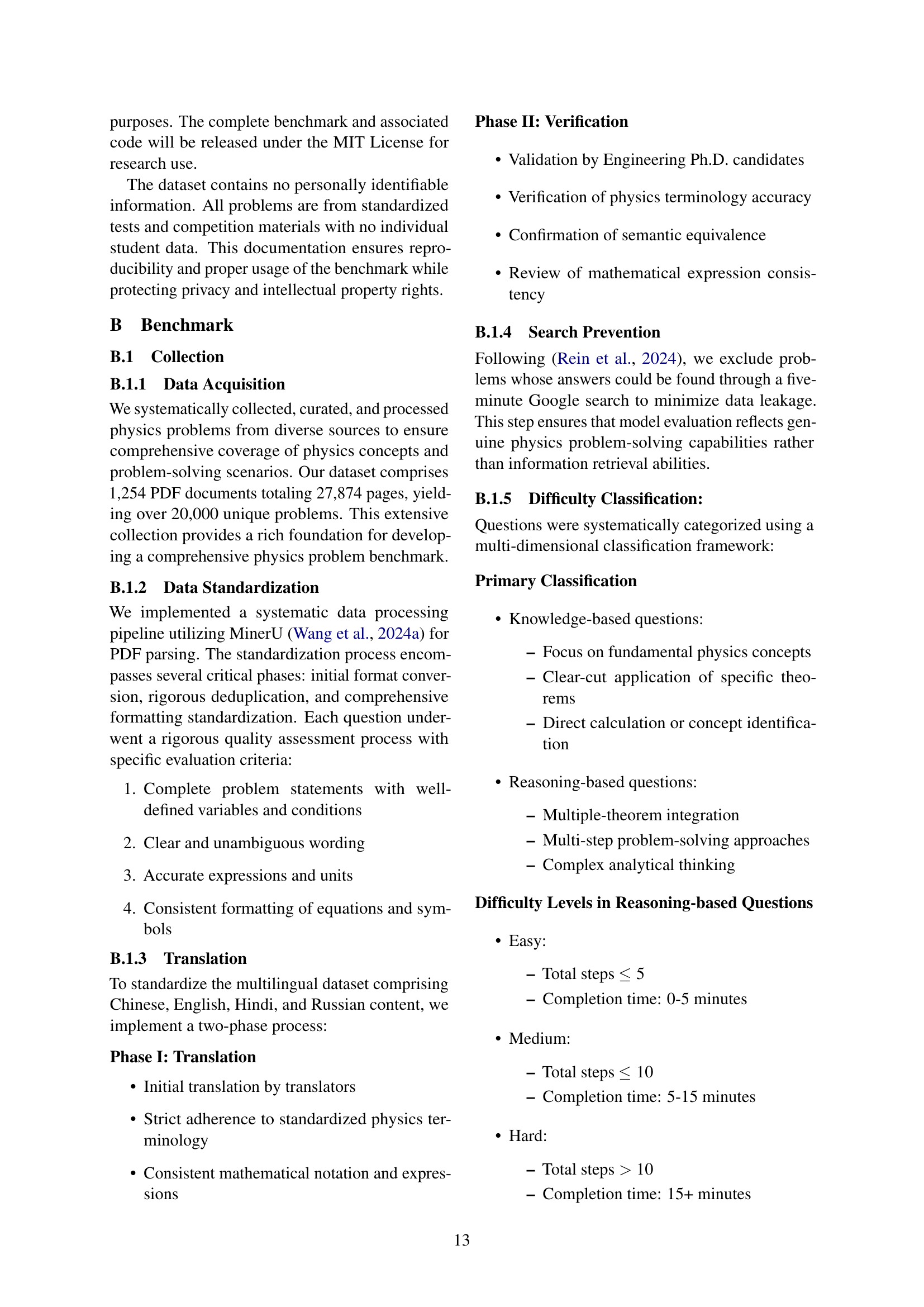

🔼 The figure illustrates the multi-stage data collection pipeline used to build the PhysReason benchmark dataset. Starting with the acquisition of raw data from multiple sources (international physics competitions, college entrance exams, etc.), the pipeline progresses through standardization, translation (to English), search prevention (removing problems easily solvable with internet searches), and finally, difficulty classification (categorizing problems into knowledge-based, easy, medium, and hard reasoning-based). The end result is a comprehensive and rigorously curated dataset ready for use in benchmarking large language models’ physics reasoning abilities.

read the caption

Figure 6: Illustration of the data collection pipeline.

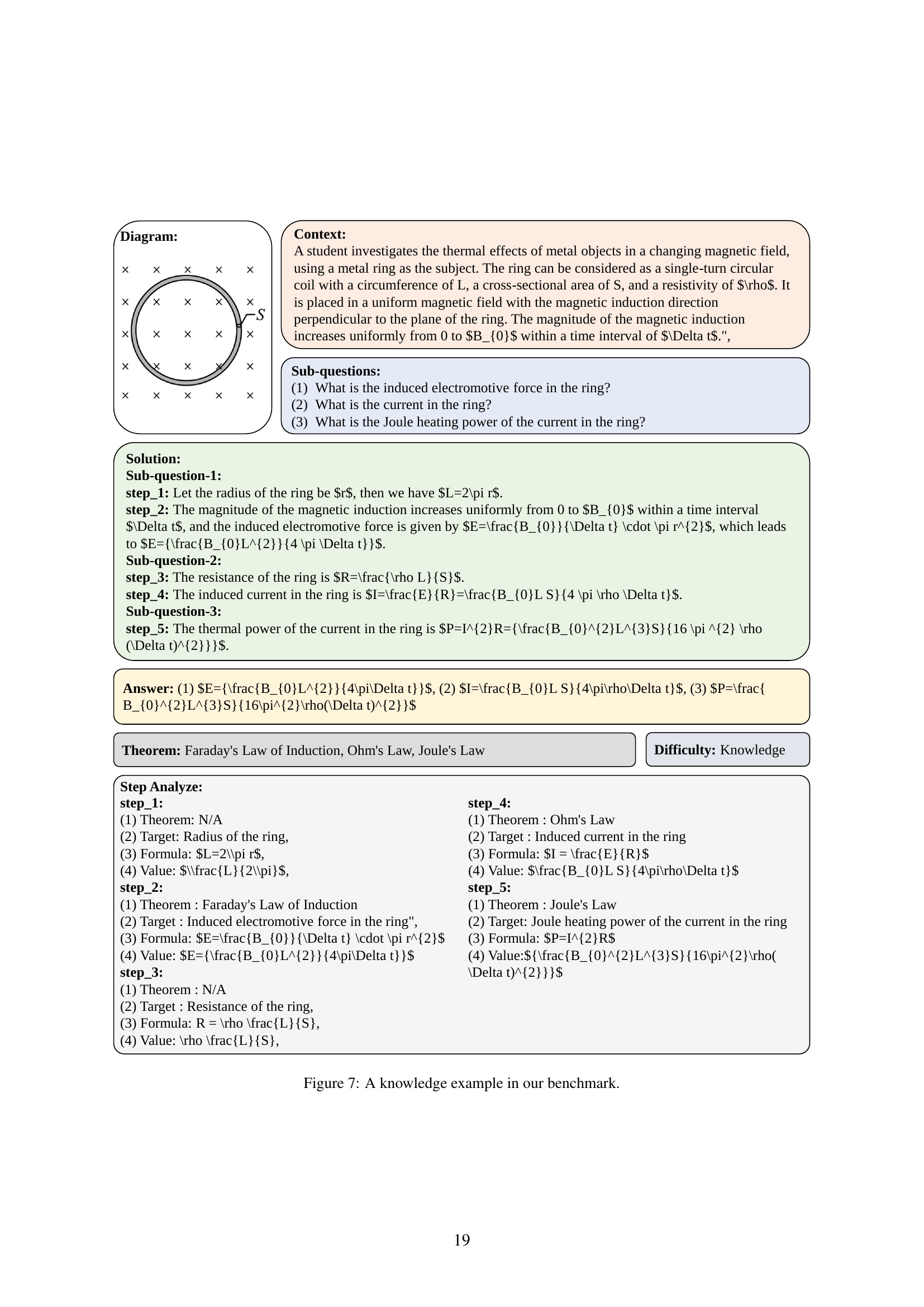

🔼 This figure displays a sample question from the PhysReason benchmark categorized as a ‘knowledge’ level problem. It presents a physics problem involving a circular metal ring within a changing magnetic field. The question requires calculating the induced electromotive force (emf) in the ring, the current flowing through it, and the resulting Joule heating power. The solution steps are shown and make use of Faraday’s law of induction, Ohm’s law, and Joule’s law. The annotation shows the theorems used for each step. This example showcases how the benchmark assesses a fundamental understanding of physics principles and basic formula applications without complex reasoning processes.

read the caption

Figure 7: A knowledge example in our benchmark.

🔼 This figure shows an example of an ’easy’ problem from the PhysReason benchmark. The problem involves a simple collision scenario between two balls: one suspended by a string and another on a frictionless surface. The solution requires applying fundamental physics principles such as the conservation of energy and momentum, with a relatively small number of steps to arrive at the answer. The diagram clearly illustrates the physical setup and the annotation details the solution steps.

read the caption

Figure 8: An easy example in our benchmark.

🔼 This medium-difficulty example presents a thermally conductive cylindrical container with a piston, containing an ideal gas. The problem involves analyzing the gas’s behavior under different orientations (vertical inverted, vertical suspended, horizontal) and temperature changes. It requires applying Boyle’s Law, the Ideal Gas Law, and force equilibrium principles to determine gas volume and temperature under various conditions. The multi-step solution involves calculating pressure under different orientations and utilizing the gas laws to connect volume, pressure, and temperature.

read the caption

Figure 9: A medium example in our benchmark.

🔼 This figure depicts a complex physics problem involving a small slider moving down a ramp, colliding with a ball, and the ball subsequently traversing a circular track and colliding with a prism. The problem requires multiple steps and the application of several physics principles including conservation of energy and momentum, and is designed to assess the model’s ability to handle multi-step reasoning and complex scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 10: A hard example in our benchmark.

Full paper#