TL;DR#

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) are trained and tested on consistent visual-textual inputs, but their ability to handle inconsistencies in real-world content remains an open question. There’s a lack of evaluation in mismatched or contradictory info, a common real-world occurrence. To solve this, the paper introduces Multimodal Inconsistency Reasoning (MMIR) benchmark. It evaluates how effectively MLLMs identify semantic mismatches within layout-rich artifacts like webpages or slides.

MMIR has 534 challenging samples with synthetic errors across five categories. Experiments on 6 MLLMs revealed models struggle, especially with cross-modal conflicts. The paper provides detailed error analyses based on category, modality and layout complexity. Probing experiments showed prompting yields marginal gains, revealing a bottleneck in cross-modal reasoning. This highlights the need for advanced reasoning, paving the way for inconsistency research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper introduces a new benchmark for evaluating MLLMs in handling inconsistencies, filling a critical gap in the field. It highlights the limitations of current models in real-world scenarios and provides a valuable resource for developing more robust multimodal reasoning systems, paving the way for future research.

Visual Insights#

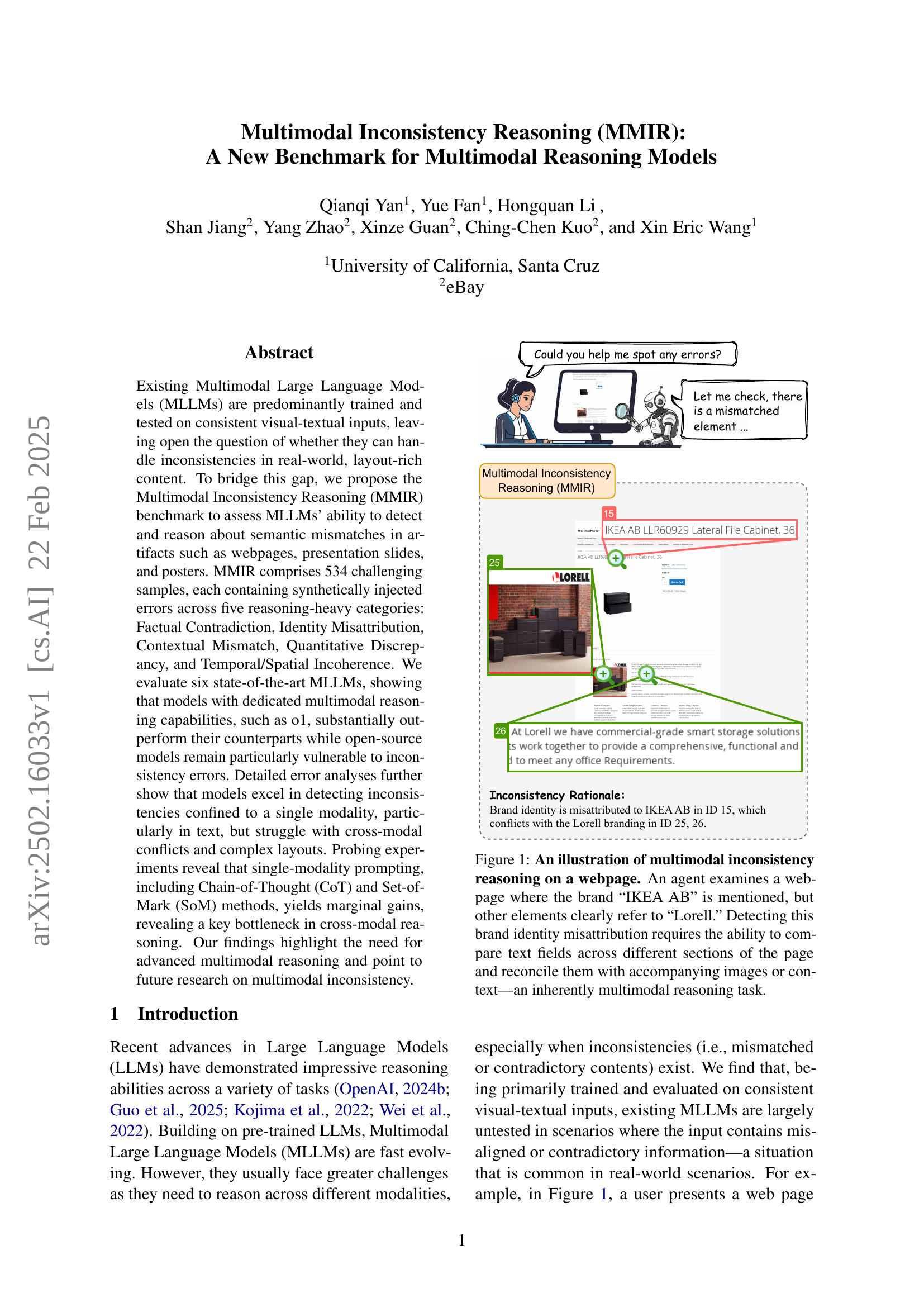

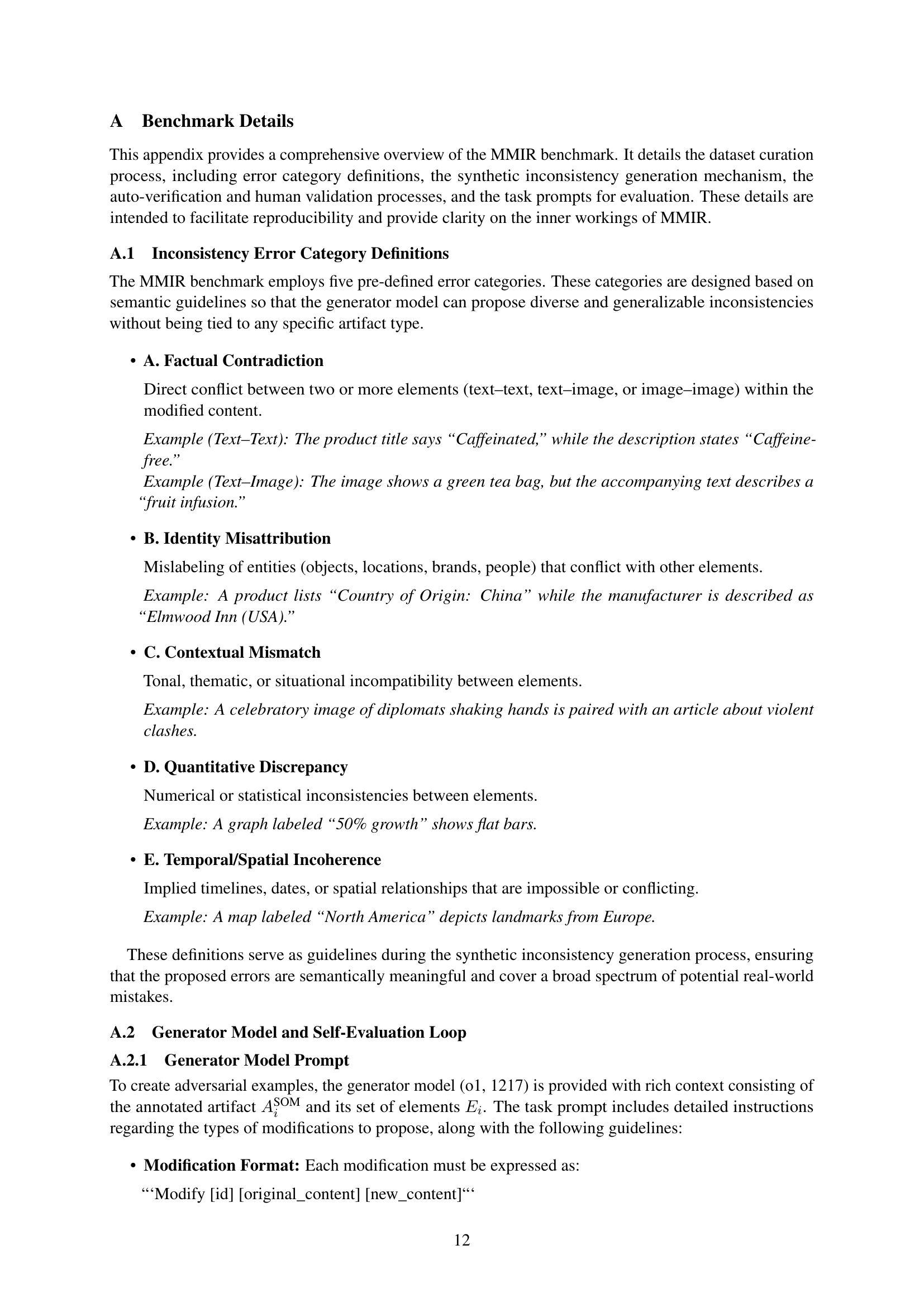

🔼 The figure shows a webpage with conflicting information. The text mentions the brand ‘IKEA AB’, but other visual elements (images and text) clearly indicate the brand is ‘Lorell’. The task of identifying this inconsistency requires a multimodal reasoning model to integrate information from both text and images, comparing textual information across different parts of the page and relating it to the corresponding visuals to determine the correct brand.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of multimodal inconsistency reasoning on a webpage. An agent examines a webpage where the brand “IKEA AB” is mentioned, but other elements clearly refer to “Lorell.” Detecting this brand identity misattribution requires the ability to compare text fields across different sections of the page and reconcile them with accompanying images or context—an inherently multimodal reasoning task.

| Category | #Questions | Ave. #Elements |

| Artifact Categories | ||

| Web | 240 | 38.8 |

| - Shopping | 108 | 46.1 |

| - Wiki | 28 | 44.9 |

| - Classifieds | 104 | 29.5 |

| Office | 223 | 9.1 |

| - Slides | 102 | 9.4 |

| - Tables/Charts | 61 | 4.1 |

| - Diagrams | 60 | 13.9 |

| Poster | 71 | 27.6 |

| Total | 543 | 24.9 |

| Error Categories | ||

| Factual Contradiction | 138 | – |

| Identity Misattribution | 84 | – |

| Contextual Mismatch | 141 | – |

| Quantitative Discrepancy | 76 | – |

| Temporal/Spatial Incoherence | 95 | – |

| Total | 543 | – |

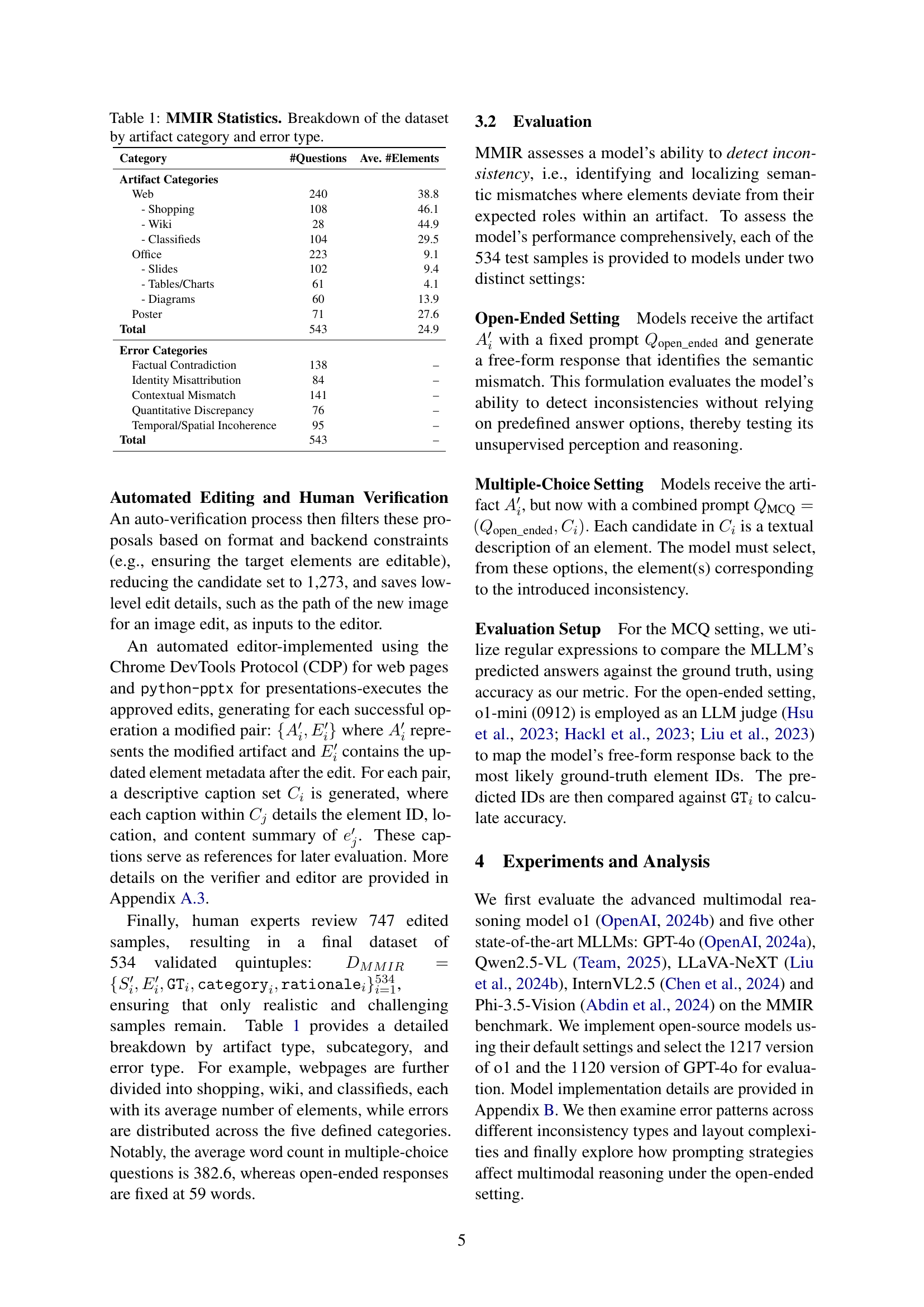

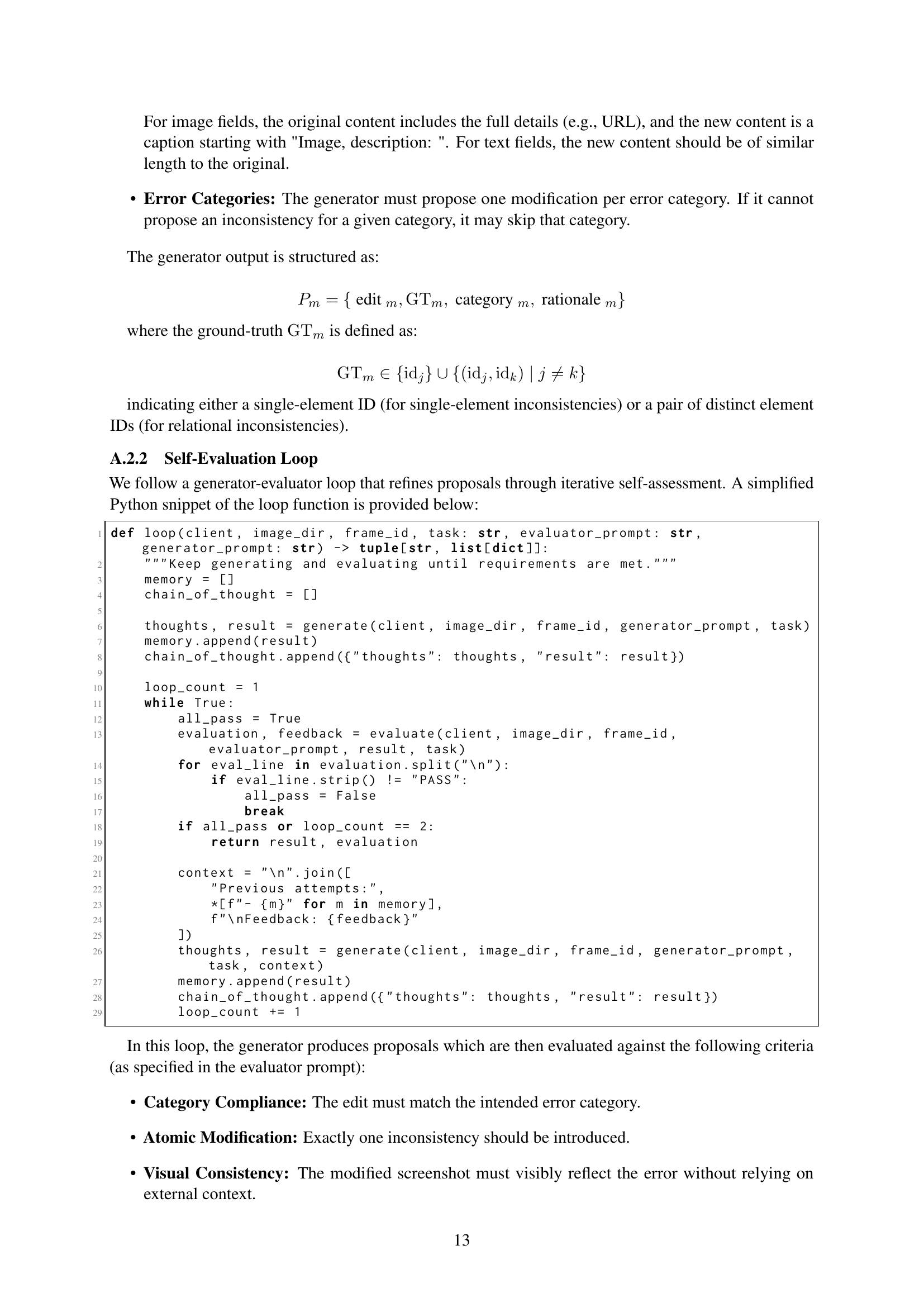

🔼 Table 1 presents a statistical overview of the MMIR benchmark dataset, categorized by artifact type and inconsistency type. It shows the number of questions, the average number of elements per question, and the distribution of questions across different artifact categories (webpages, office documents, posters) and inconsistency categories (factual contradiction, identity misattribution, contextual mismatch, quantitative discrepancy, temporal/spatial incoherence). This breakdown provides insights into the dataset’s composition and the relative prevalence of different types of inconsistencies.

read the caption

Table 1: MMIR Statistics. Breakdown of the dataset by artifact category and error type.

In-depth insights#

MMIR Benchmark#

The MMIR benchmark, standing for Multimodal Inconsistency Reasoning, is a pivotal contribution for assessing MLLMs’ ability to handle semantic mismatches in real-world artifacts. It is innovative because it contains diverse error types, like factual contradictions and temporal incoherence. The challenging nature lies in requiring intricate reasoning rather than pattern recognition, focusing on identifying inconsistencies within complex, layout-rich content. The benchmark aids in future multimodal reasoning studies and exposes MLLMs limitations.

Multimodal Reasoning#

Multimodal reasoning is at the heart of the paper’s focus, driving the need for a new benchmark (MMIR). The paper highlights how existing Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) often struggle with inconsistencies when dealing with real-world, layout-rich content. This implies that current models are primarily trained on consistent data and lack the robustness to handle the variations and complexities of the real world. The authors emphasize the significance of robust reasoning in handling data from multiple modalities, especially in cases where inconsistencies are present. This reasoning must go beyond simple pattern recognition, requiring the models to cross-reference, analyze, and reconcile information from text, images, and layouts. The MMIR benchmark pushes models towards intricate reasoning processes, prompting advancements in the field.

Inconsistency Type#

Inconsistency type is a critical aspect in multimodal reasoning, highlighting semantic mismatches within content. Categories like factual contradiction, identity misattribution, contextual mismatch, quantitative discrepancy, and temporal/spatial incoherence are essential for assessing model abilities. These types demand intricate reasoning beyond simple pattern recognition, posing significant challenges for MLLMs. Addressing these inconsistencies is vital for robust, real-world applications.

Probing Methods#

The probing methods section is aimed at understanding the limits of solely relying on textual or visual cues for inconsistency detection. It explores Chain-of-Thought (CoT), Set-of-Mark (SoM), and a multimodal interleaved CoT (MM-CoT) approach. The findings reveal that simply injecting explicit reasoning steps (CoT) or enhancing visual perception (SoM) often provides little improvements. The key lies in creating a system where the model can iteratively go back and forth between text and vision to successfully detect inconsistencies.

Dataset Details#

The paper introduces the Multimodal Inconsistency Reasoning Benchmark (MMIR) to assess how well models identify semantic mismatches. The dataset comprises 534 challenging samples across diverse real-world artifacts, including webpages, slides, and posters. Data curation followed a four-stage pipeline. Artifacts were collected and parsed, synthetic inconsistencies were injected, then auto-editing & human verification followed. MMIR assesses models’ ability to detect inconsistencies in open-ended and multiple-choice settings. The team will release the dataset for open research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

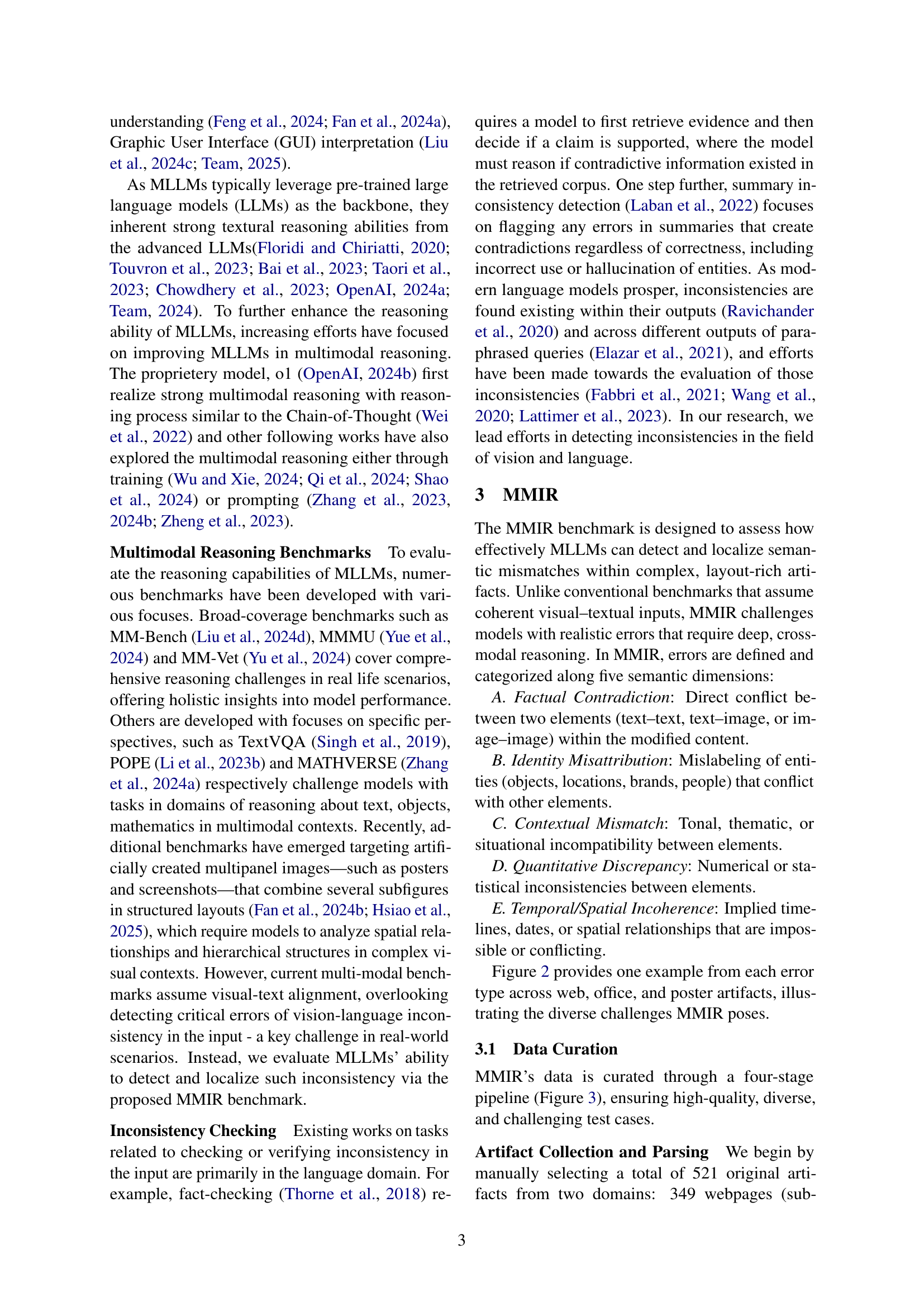

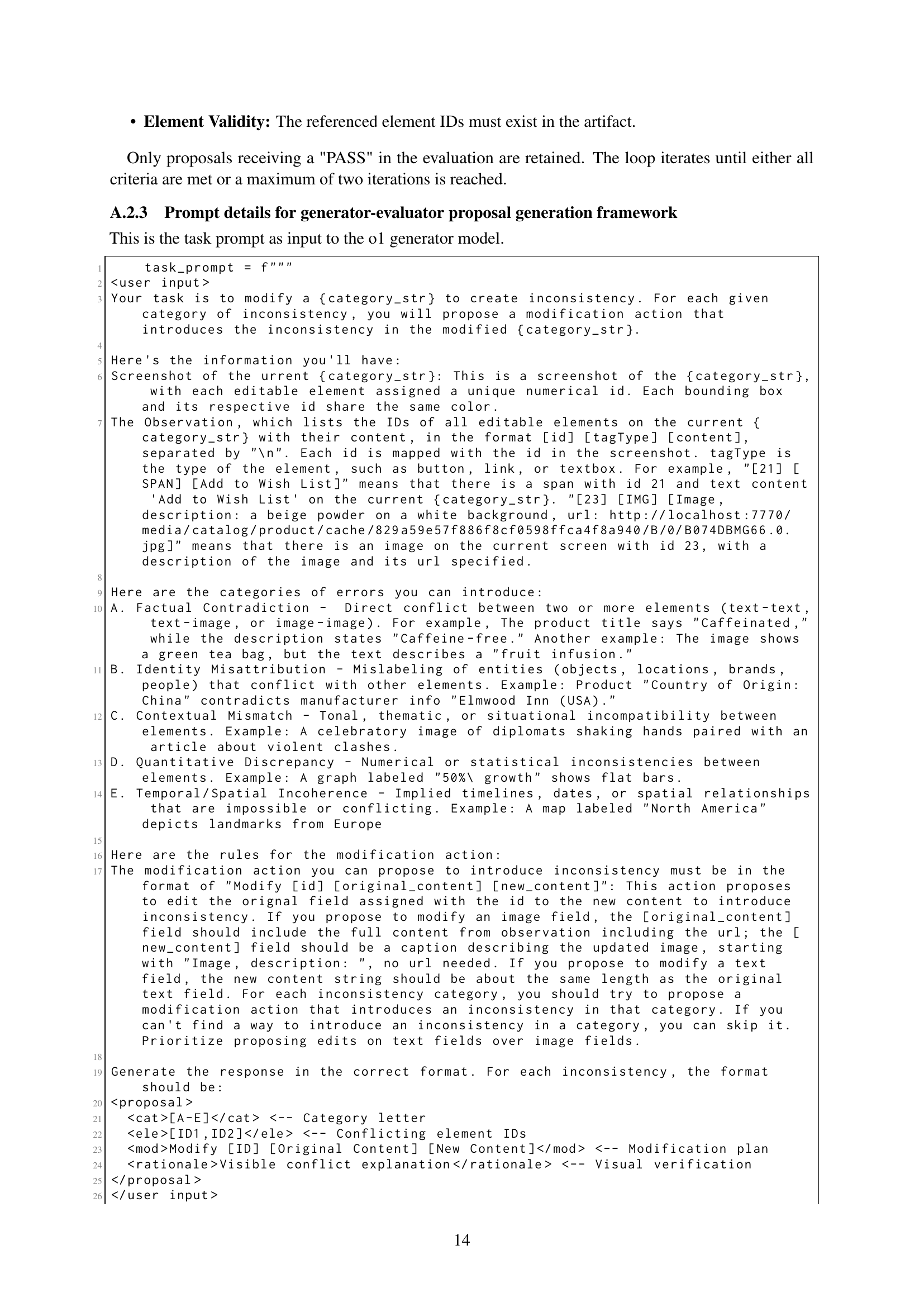

🔼 Figure 2 presents five example inconsistencies from the MMIR benchmark dataset, each representing a different category of multimodal inconsistency. These examples illustrate the diverse challenges that the benchmark presents for multimodal reasoning models. The categories are: Factual Contradiction (a conflict between text and image), Identity Misattribution (mismatched brand information across different elements), Contextual Mismatch (thematic mismatch between elements), Quantitative Discrepancy (numerical errors in a chart compared to text), and Temporal/Spatial Incoherence (time or location conflicts within the presented elements). Each example demonstrates the complexity of detecting inconsistencies across modalities and different layouts.

read the caption

Figure 2: There are five inconsistency categories in the MMIR benchmark, posing diverse challenges.

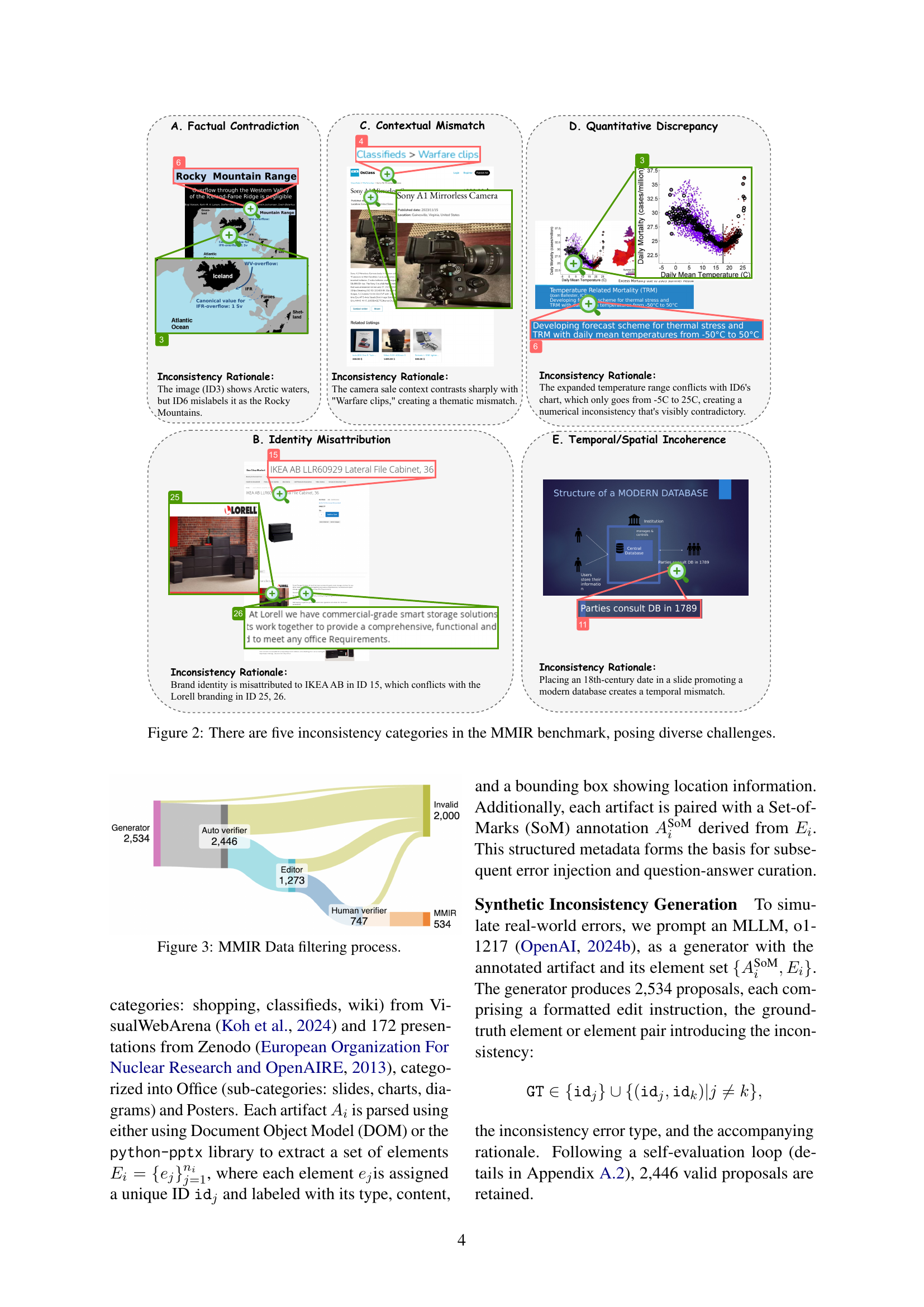

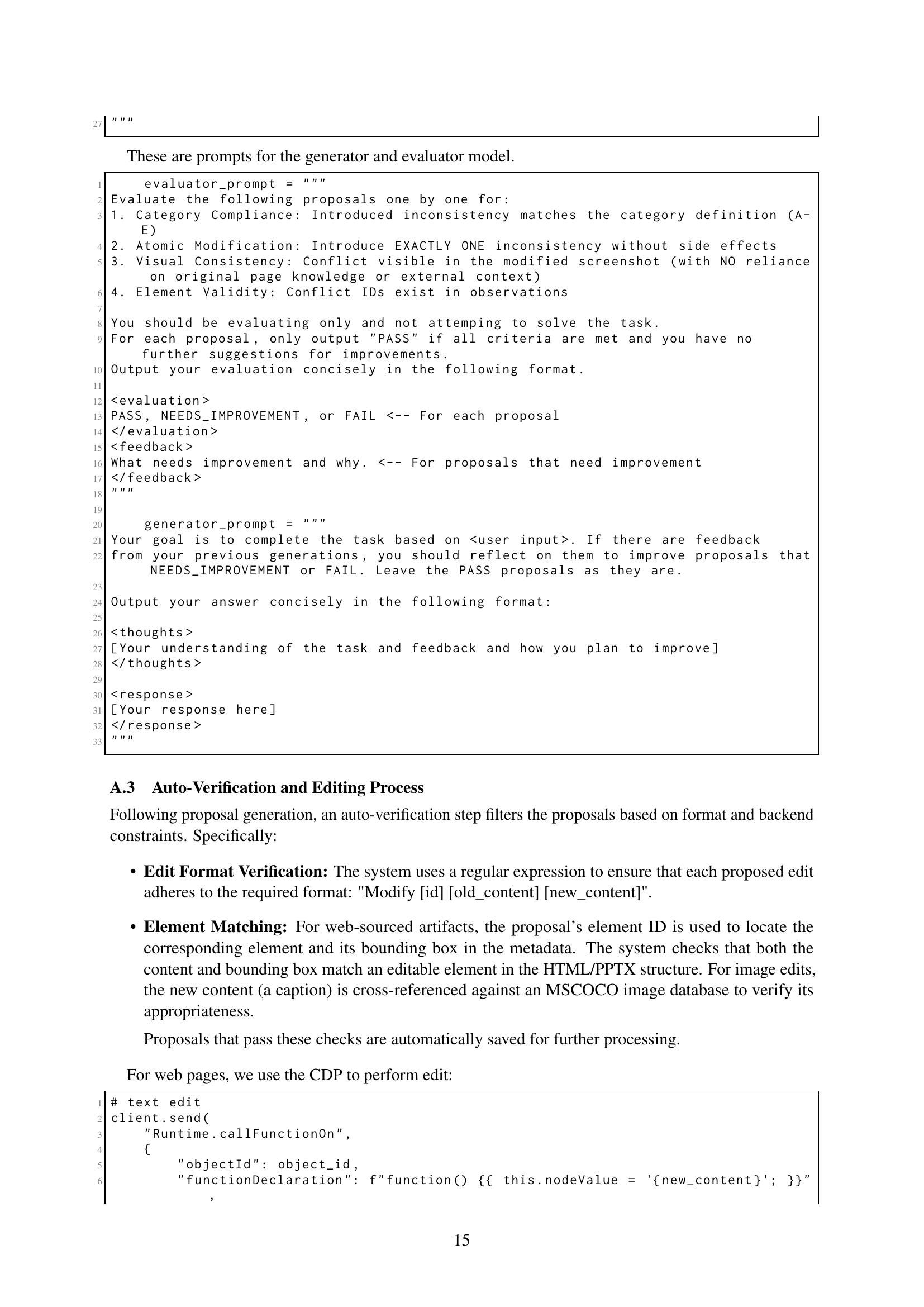

🔼 The figure illustrates the four-stage process of MMIR data curation. It begins with the collection and parsing of 521 artifacts, followed by the synthetic injection of inconsistencies using the 01-1217 language model, resulting in 2,534 proposals. After automated editing and human verification, the final dataset of 534 validated quintuples is obtained. These quintuples consist of the modified artifact, its elements, the type of inconsistency introduced, and the rationale behind it. This filtered dataset forms the MMIR benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 3: MMIR Data filtering process.

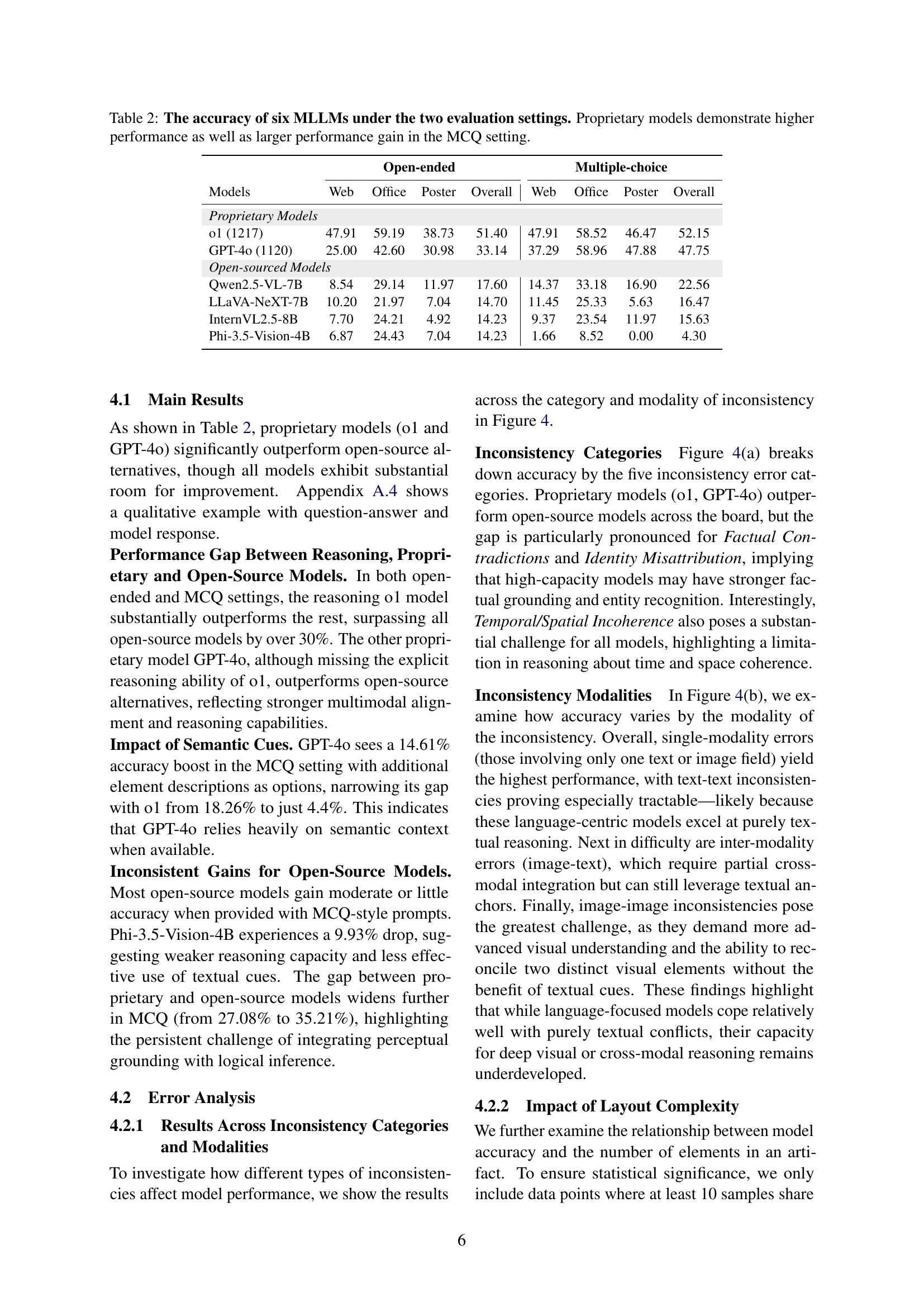

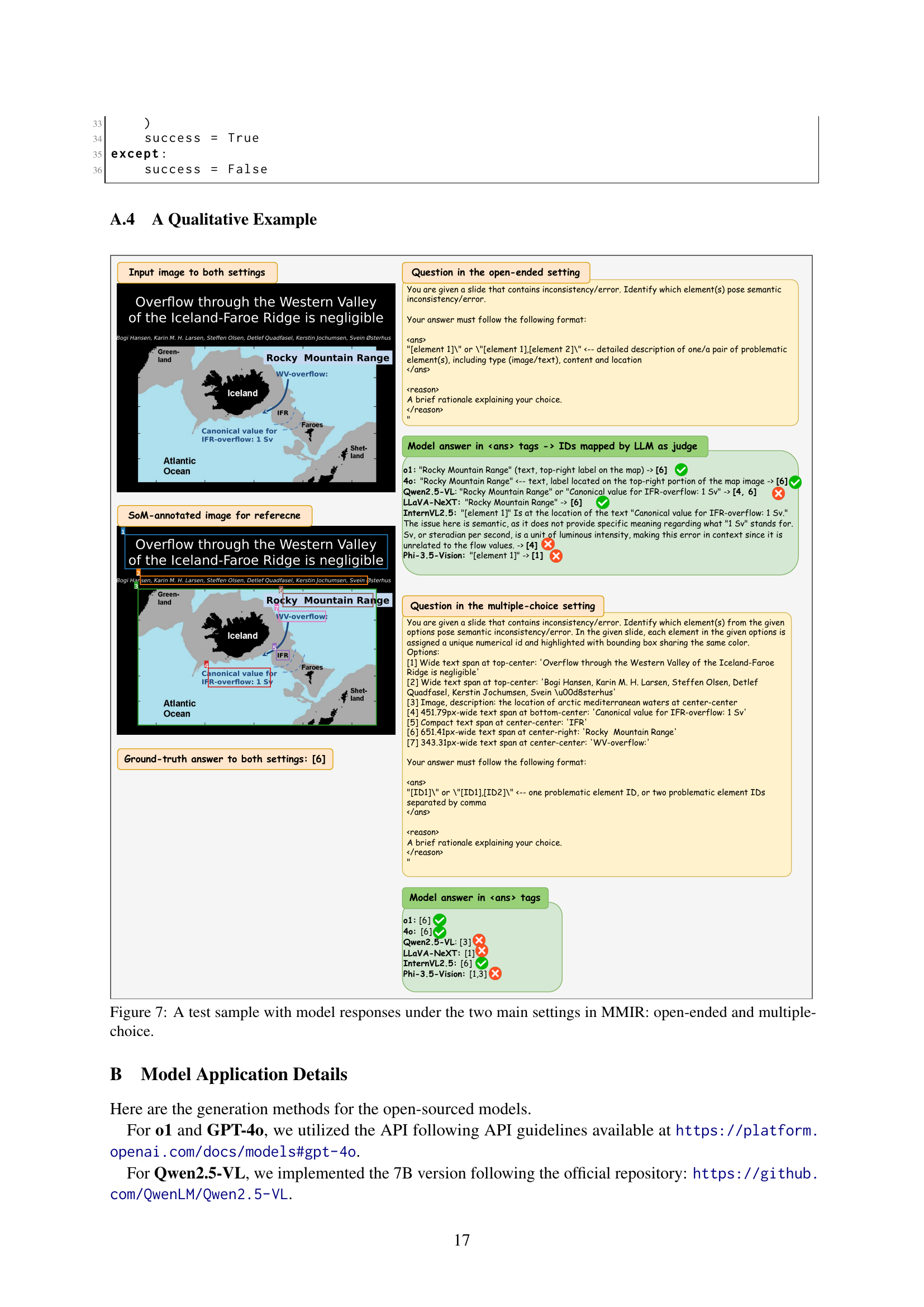

🔼 This figure presents a detailed breakdown of model performance on the MMIR benchmark. Panel (a) shows accuracy broken down by the five types of inconsistencies (factual contradiction, identity misattribution, contextual mismatch, quantitative discrepancy, and temporal/spatial incoherence). Panel (b) displays accuracy broken down by the type of modality involved in the inconsistency (text-only, image-only, text and image). The figure shows that models perform better on inconsistencies involving a single modality, particularly text, and struggle more with cross-modal inconsistencies. The superior performance of proprietary models (o1 and GPT-40) is also evident across all inconsistency categories and modalities.

read the caption

Figure 4: Fine-grained analysis of model performance.

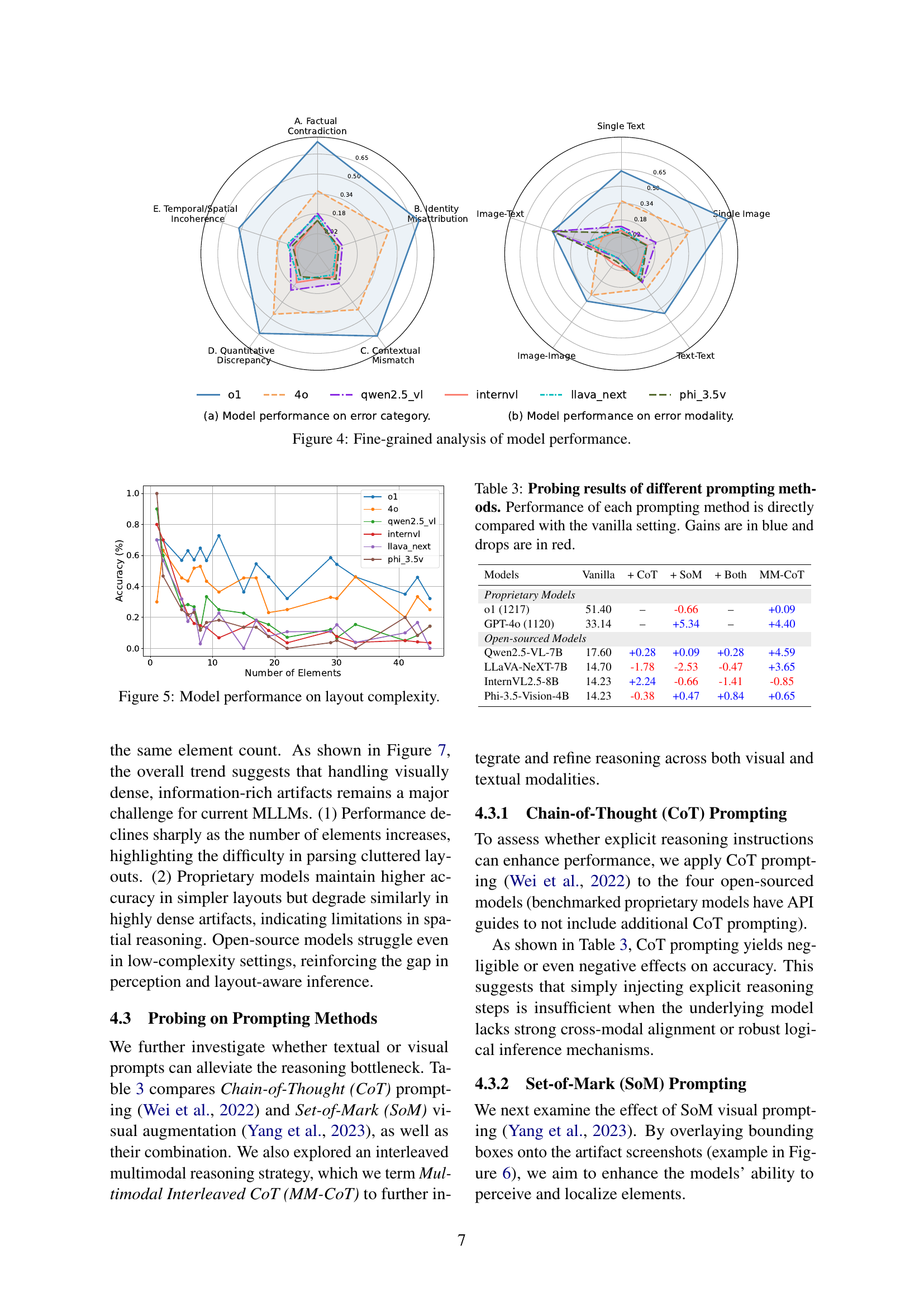

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the number of elements in an artifact and model performance on the MMIR benchmark. It reveals that as the complexity of the layout increases (i.e., more elements in the artifact), the accuracy of all models decreases. Proprietary models maintain higher accuracy in simpler layouts but show a similar decline in performance as complexity increases compared to open-source models. Open-source models struggle even with low-complexity artifacts.

read the caption

Figure 5: Model performance on layout complexity.

🔼 This figure shows a side-by-side comparison: on the left, the original webpage from the Multimodal Inconsistency Reasoning (MMIR) benchmark; on the right, the same webpage after it has been annotated using the Set-of-Marks (SoM) method for probing experiments. SoM highlights relevant elements (bounding boxes) in the image to help evaluate the effectiveness of prompting methods on visual multimodal reasoning. This helps assess how well models can leverage visual cues when integrated with textual prompting for improved reasoning performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: Example of original artifact in MMIR (left) and artifact annotated with Set-of-Mark in the probing analysis (right).

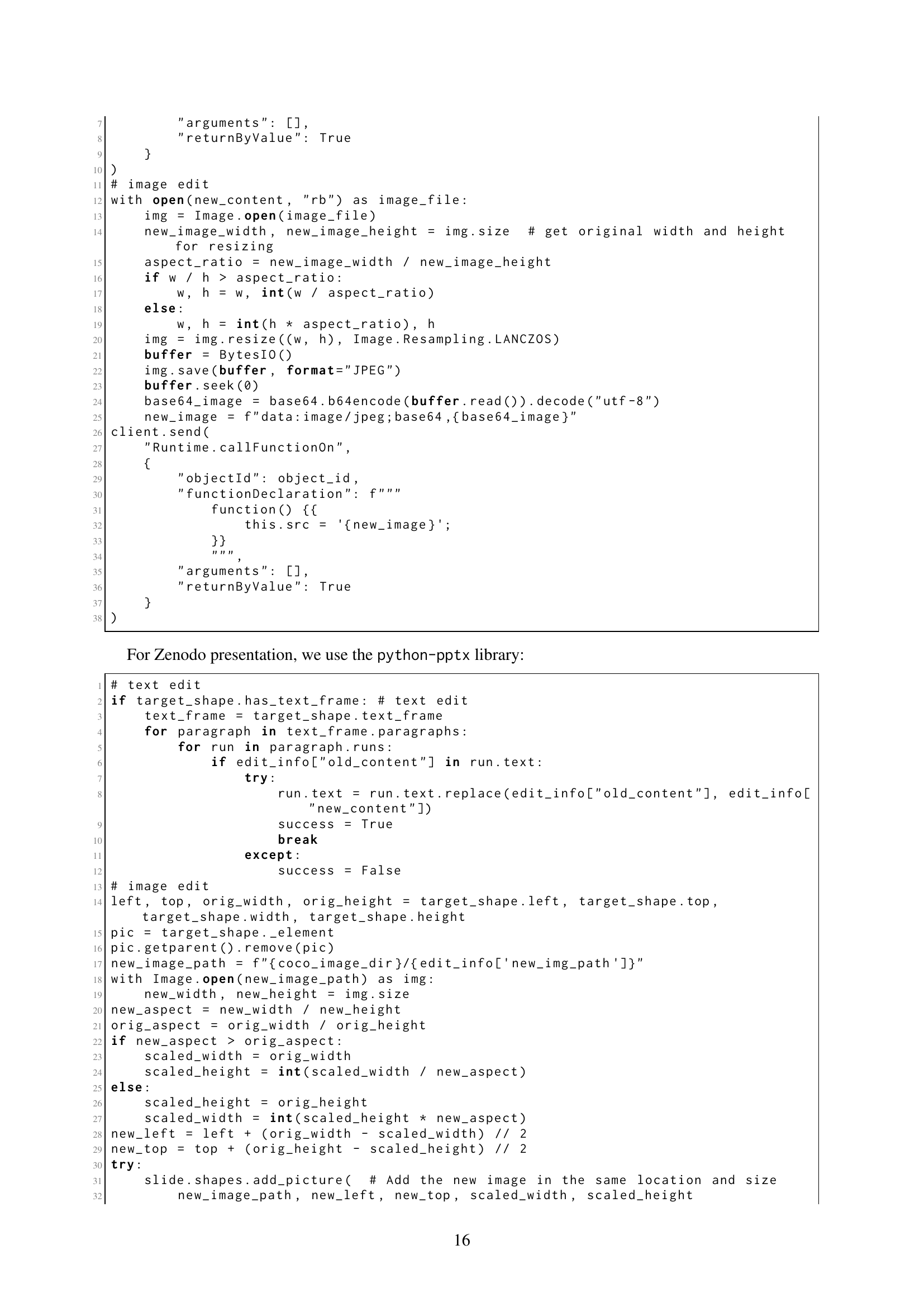

🔼 This figure displays a sample from the MMIR benchmark, illustrating how different models perform under open-ended and multiple-choice evaluation settings. The left side shows the original image, which contains a factual contradiction: a map labels a geographic region as ‘Rocky Mountain Range’ when it is in fact a different arctic region. The right side presents model responses for both question types; open-ended responses show the model’s ability to identify the error without predefined options, while multiple-choice responses test accuracy when provided with choices of potential inconsistent elements.

read the caption

Figure 7: A test sample with model responses under the two main settings in MMIR: open-ended and multiple-choice.

More on tables

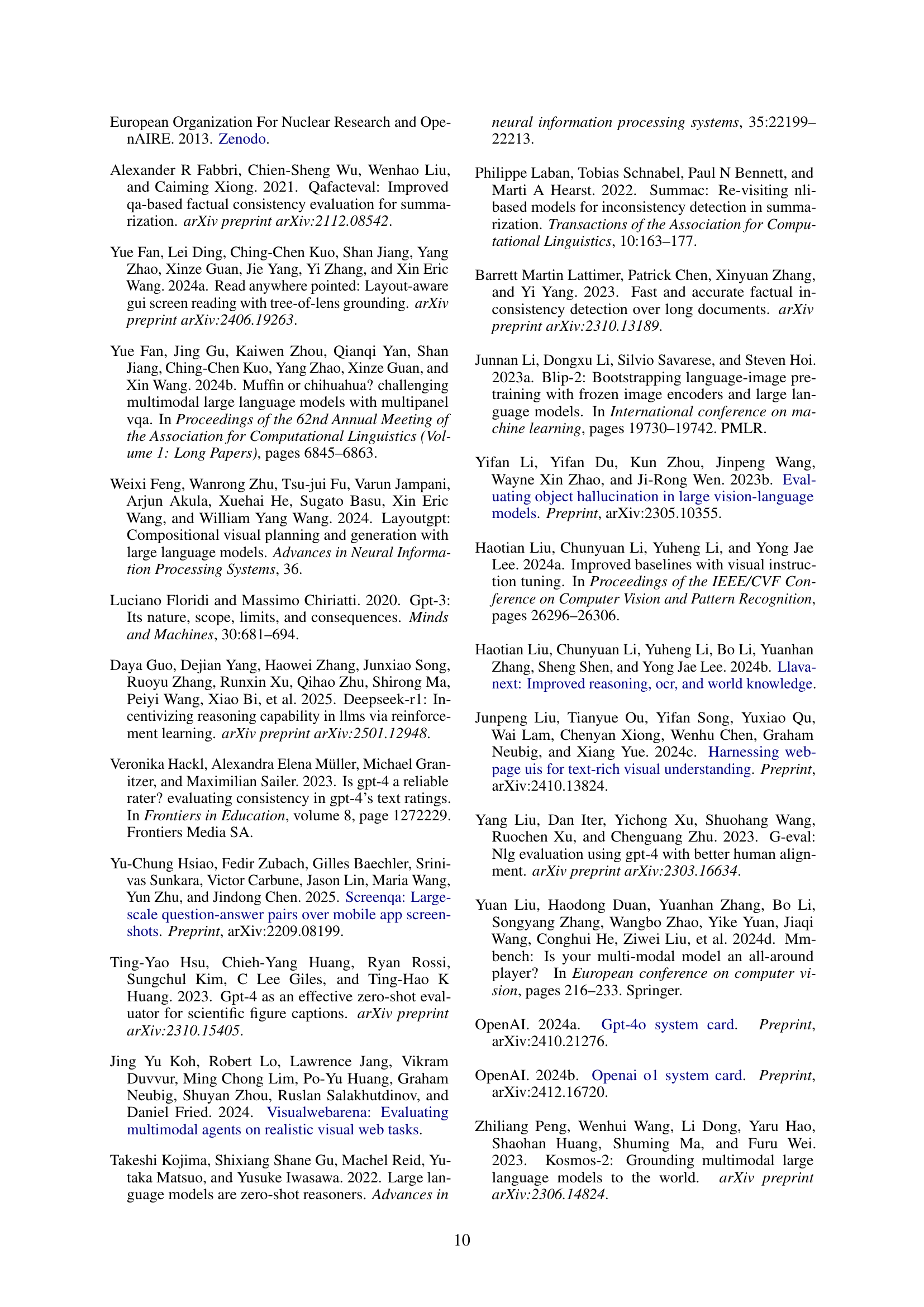

| Open-ended | Multiple-choice | |||||||

| Models | Web | Office | Poster | Overall | Web | Office | Poster | Overall |

| Proprietary Models | ||||||||

| o1 (1217) | 47.91 | 59.19 | 38.73 | 51.40 | 47.91 | 58.52 | 46.47 | 52.15 |

| GPT-4o (1120) | 25.00 | 42.60 | 30.98 | 33.14 | 37.29 | 58.96 | 47.88 | 47.75 |

| Open-sourced Models | ||||||||

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 8.54 | 29.14 | 11.97 | 17.60 | 14.37 | 33.18 | 16.90 | 22.56 |

| LLaVA-NeXT-7B | 10.20 | 21.97 | 7.04 | 14.70 | 11.45 | 25.33 | 5.63 | 16.47 |

| InternVL2.5-8B | 7.70 | 24.21 | 4.92 | 14.23 | 9.37 | 23.54 | 11.97 | 15.63 |

| Phi-3.5-Vision-4B | 6.87 | 24.43 | 7.04 | 14.23 | 1.66 | 8.52 | 0.00 | 4.30 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of six different Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) on a multimodal inconsistency reasoning benchmark (MMIR). The models are evaluated under two settings: an open-ended setting where the model freely generates a response identifying inconsistencies, and a multiple-choice question (MCQ) setting where the model selects from pre-defined options. The results show that proprietary models (those not open-source) significantly outperform open-source models in both settings, demonstrating a substantial performance gap. Moreover, proprietary models show a much larger performance improvement in the MCQ setting compared to the open-ended setting. This highlights the challenges posed by multimodal inconsistency reasoning and the limitations of current open-source MLLMs in this area.

read the caption

Table 2: The accuracy of six MLLMs under the two evaluation settings. Proprietary models demonstrate higher performance as well as larger performance gain in the MCQ setting.

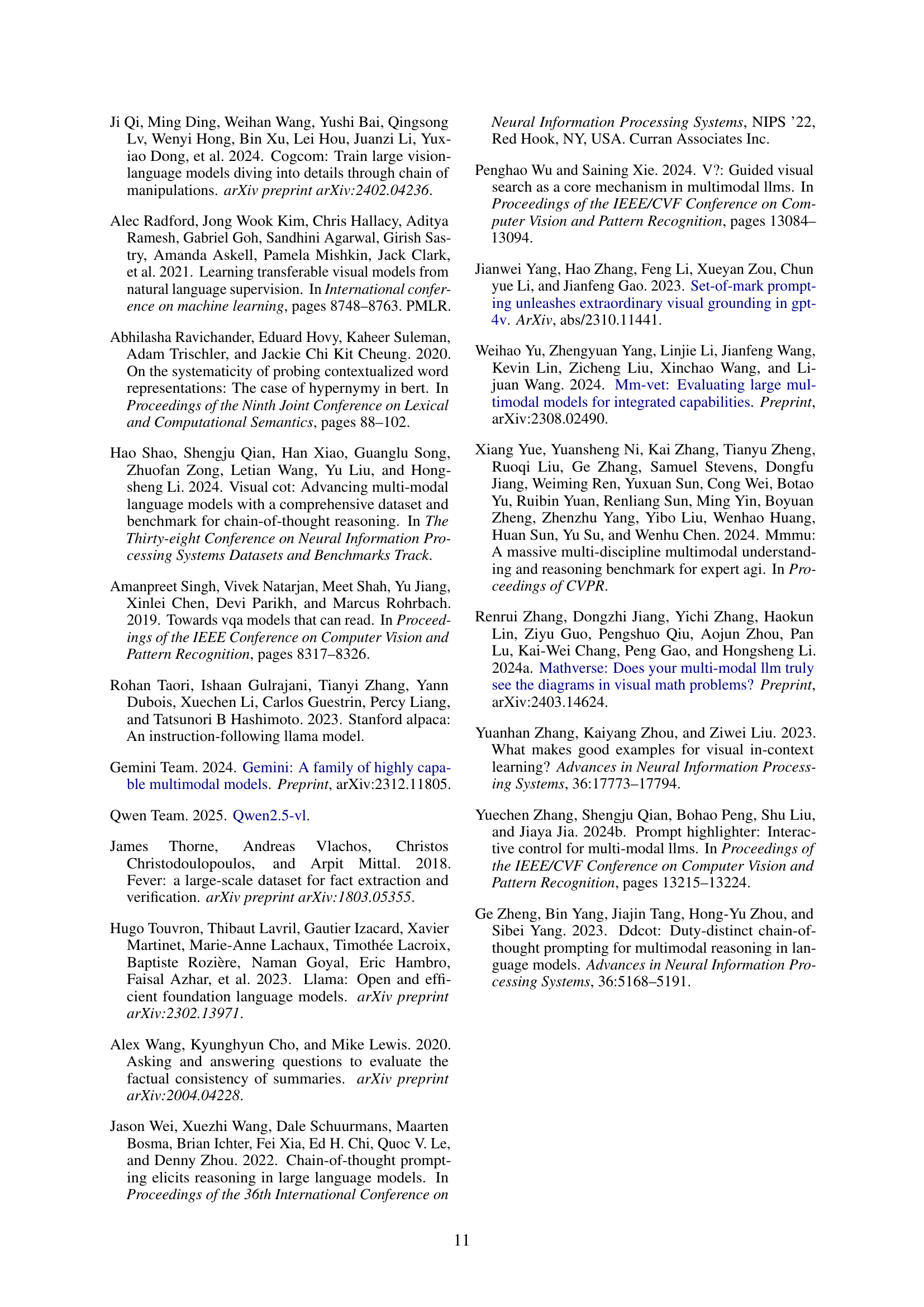

| Models | Vanilla | + CoT | + SoM | + Both | MM-CoT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proprietary Models | |||||

| o1 (1217) | 51.40 | – | -0.66 | – | +0.09 |

| GPT-4o (1120) | 33.14 | – | +5.34 | – | +4.40 |

| Open-sourced Models | |||||

| Qwen2.5-VL-7B | 17.60 | +0.28 | +0.09 | +0.28 | +4.59 |

| LLaVA-NeXT-7B | 14.70 | -1.78 | -2.53 | -0.47 | +3.65 |

| InternVL2.5-8B | 14.23 | +2.24 | -0.66 | -1.41 | -0.85 |

| Phi-3.5-Vision-4B | 14.23 | -0.38 | +0.47 | +0.84 | +0.65 |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating different prompting methods on a multimodal inconsistency reasoning benchmark. The benchmark assesses the ability of large language models to detect inconsistencies in multimodal data. The methods tested include Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, Set-of-Mark (SoM) visual augmentation, a combination of both, and a novel Multimodal Interleaved CoT (MM-CoT) approach. The table compares the performance of each method against a baseline (vanilla) setting, indicating gains or losses in accuracy. The results are categorized by model type (proprietary vs. open-source).

read the caption

Table 3: Probing results of different prompting methods. Performance of each prompting method is directly compared with the vanilla setting. Gains are in blue and drops are in red.

Full paper#