TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated excellent capabilities across various domains, especially in code generation, however, critique benchmarks often lack comprehensive code related tasks. Existing critique benchmarks prioritize general reasoning, overlooking vital aspects of software development such as error identification and code QA. This gap hinders the development of robust LLM-based coding assistance and automated code review systems. To address this, a comprehensive and specialized evaluation is needed.

To address the limitations, The paper introduces CodeCriticBench, a holistic benchmark for code critique by LLMs. It covers code generation and QA with varied difficulty, incorporating basic/advanced evaluations for comprehensive ability analysis. The findings reveal that LLMs face unique challenges in code-related critique tasks, marking a significant step towards enhancing LLMs for software development and ensuring thorough evaluation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This research offers a new benchmark for assessing code critique in LLMs, which is essential for developing coding assistance and review systems. It contributes to advancing LLMs in coding tasks and fosters further research into the analytical capabilities of LLMs.

Visual Insights#

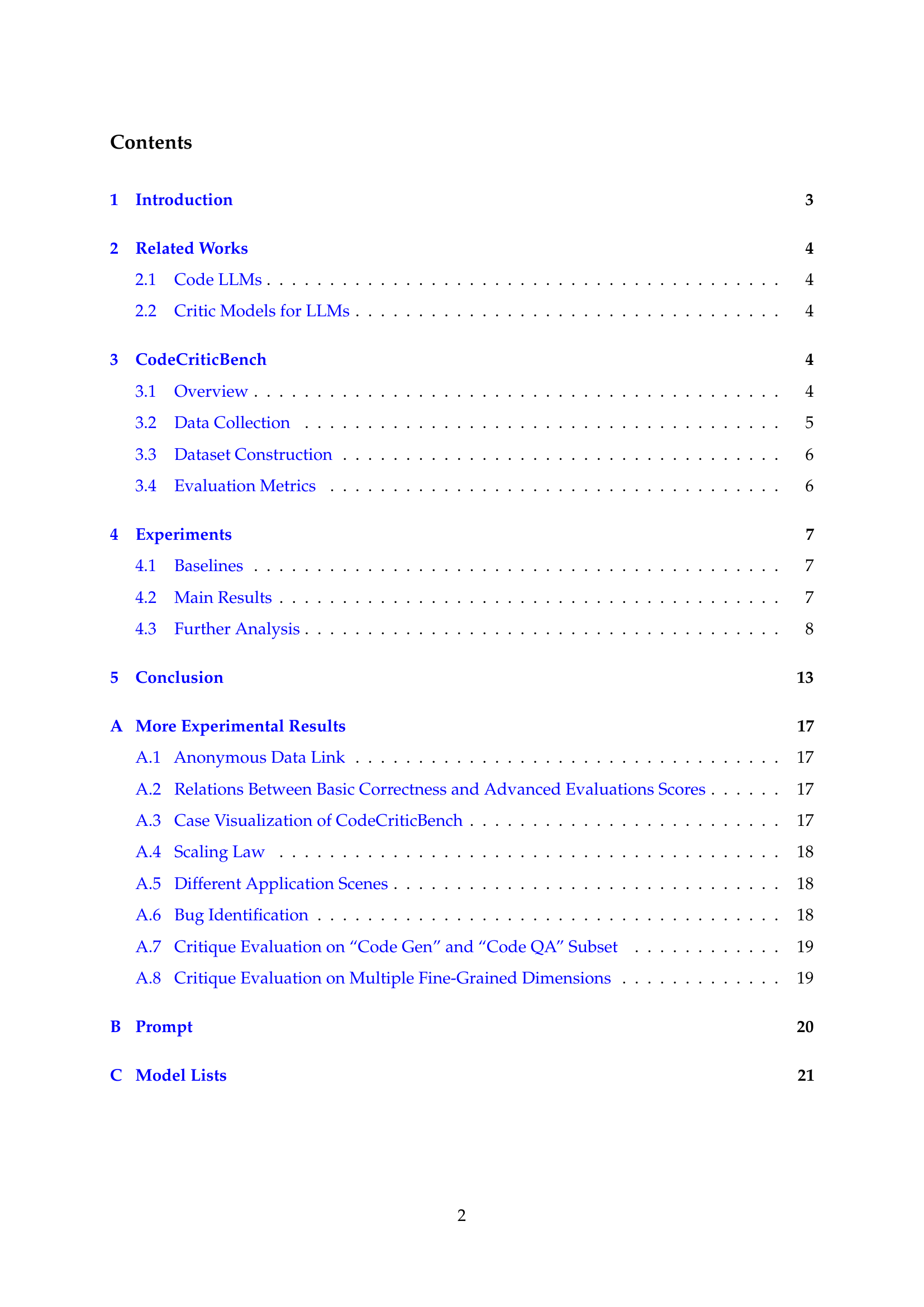

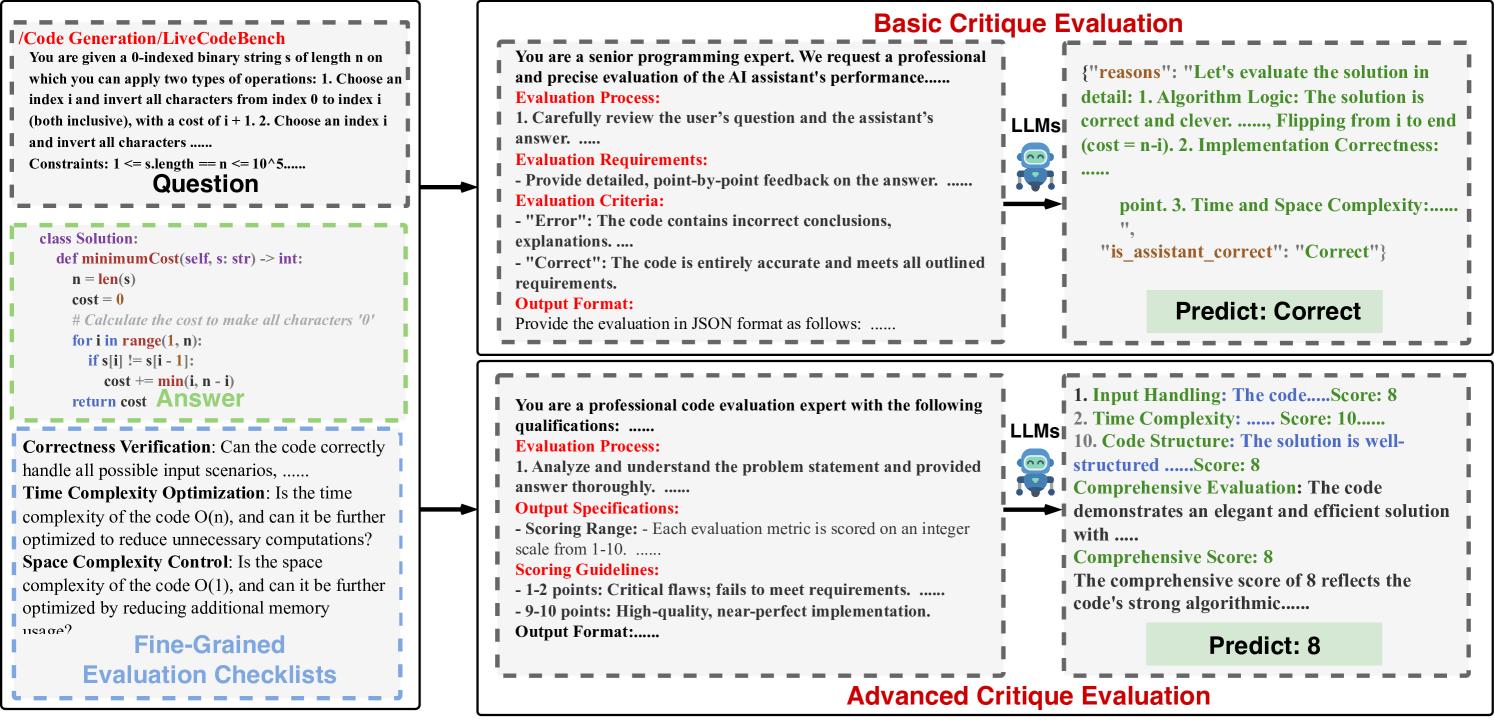

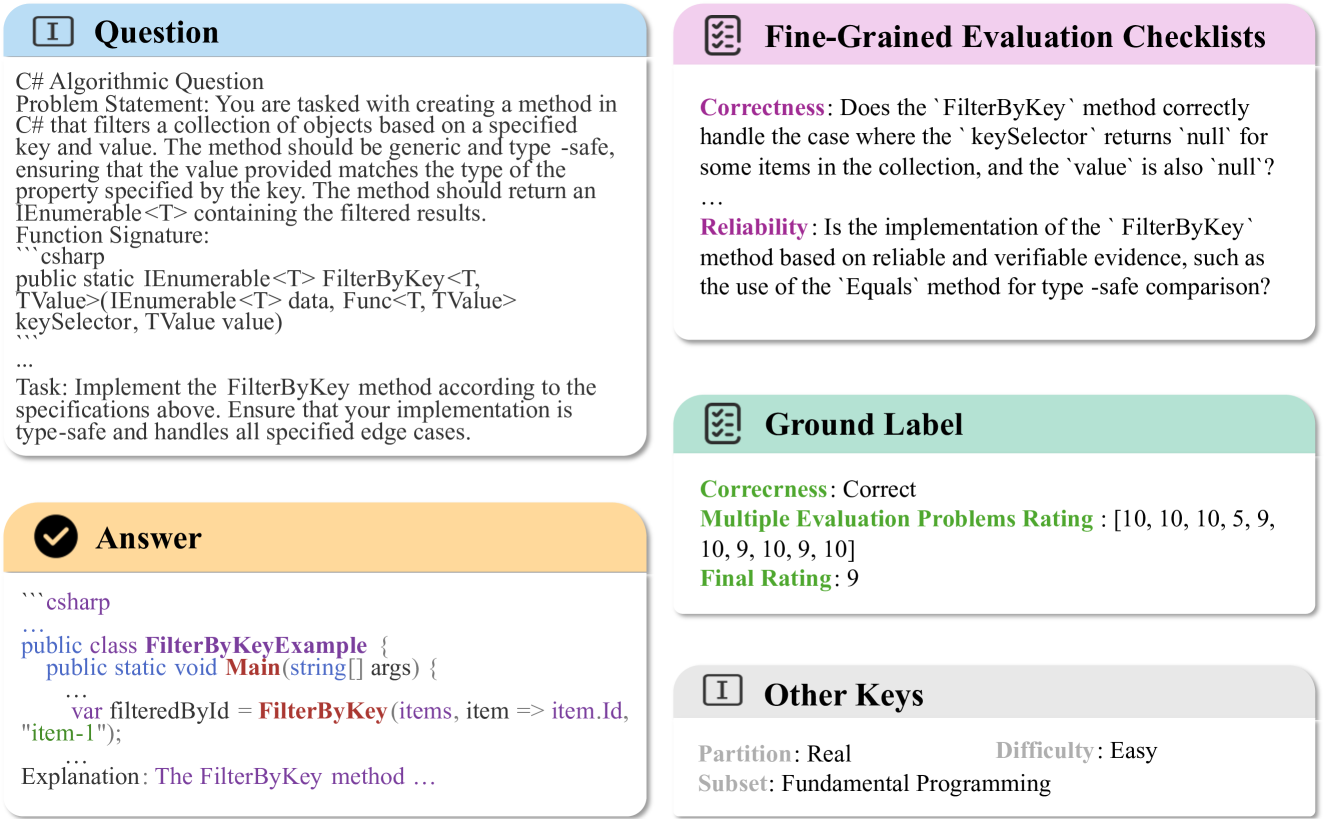

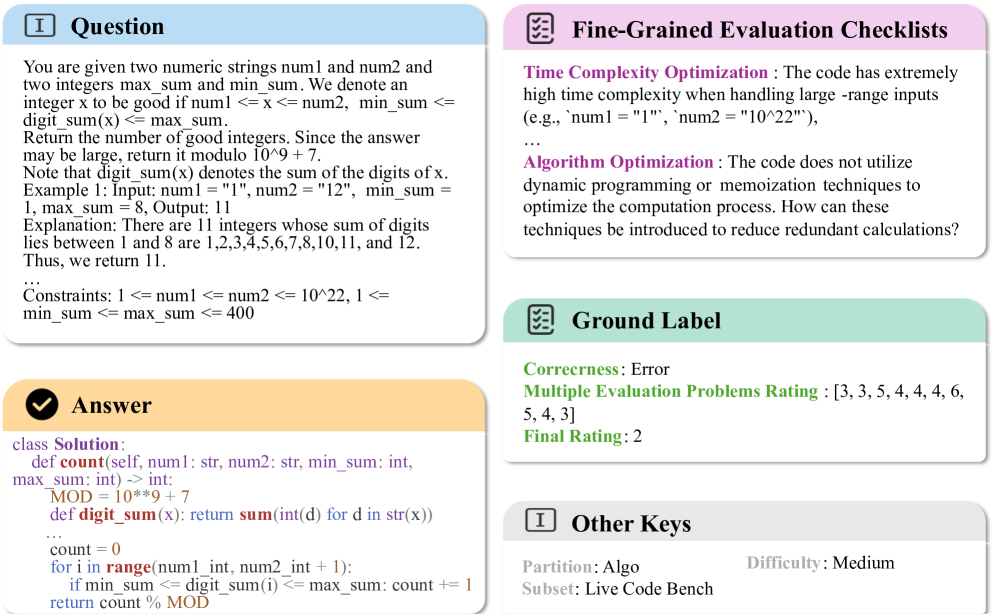

🔼 This figure illustrates the two evaluation protocols used in CodeCriticBench: basic and advanced critique evaluation. The basic critique evaluation involves a simple correct/incorrect judgment with a justification. The advanced critique evaluation uses a more detailed, fine-grained evaluation checklist with scores (1-10) for various aspects of the AI assistant’s response, leading to a comprehensive score.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the Basic Critique Evaluation and Advanced Critique Evaluation.

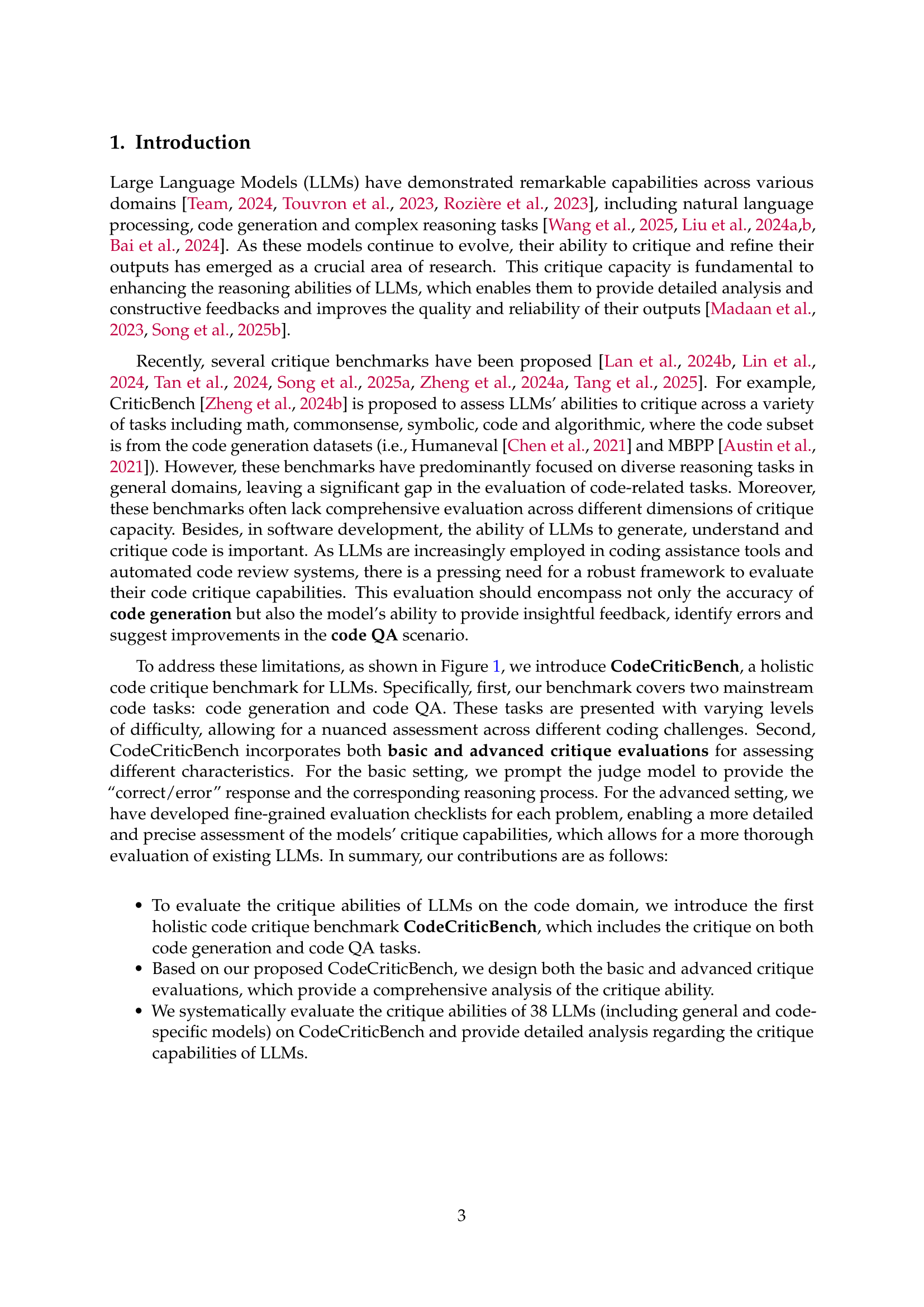

| Benchmark | Data Size | Code Gen. | Code QA | Basic | Advanced |

| CriticBench | 3,825 | 464 | - | ✓ | × |

| CriticEval | 3,608 | 1,340 | - | ✓ | × |

| JudgeBench | 350 | 42 | - | ✓ | × |

| RealCritic | 2,093 | - | - | ✓ | × |

| CodeCriticBench | 4,300 | 3,200 | 1,100 | ✓ | ✓ |

🔼 This table presents a statistical overview of the CodeCriticBench dataset. It includes the number of problems, their distribution across difficulty levels (easy, medium, hard), and the length of questions and answers in terms of tokens. Token counts are determined using the LLaMA3 tokenizer. The table also provides the maximum, minimum, and average token lengths for questions, answers, and fine-grained evaluation checklists.

read the caption

Table 1: Dataset statistics of CodeCriticBench.

In-depth insights#

LLM Code Critique#

The paper introduces CodeCriticBench, a benchmark for evaluating LLMs’ code critique abilities. It addresses limitations in existing benchmarks by focusing on diverse code-related tasks (generation and QA) and offering comprehensive evaluation across dimensions. Crucially, the benchmark includes both basic (correct/incorrect) and advanced critique evaluations, with fine-grained checklists for detailed assessments. This comprehensive approach allows for a more thorough analysis of LLMs’ critique capabilities, including identifying errors, providing insightful feedback, and suggesting improvements. By evaluating a wide range of LLMs, the authors provide valuable insights into their code critique performance, paving the way for future research.

Basic vs. Advanced#

Basic critique likely involves simple correctness checks, while advanced critique dives deeper. Advanced methods could use fine-grained metrics, offering richer insights than basic ‘correct/incorrect’ judgments. Fine-grained analysis with well-designed checklists can offer more detailed and precise assessment of the models’ critique capabilities than basic evaluation.

CodeCriticBench#

CodeCriticBench, a novel benchmark, aims to address limitations in existing critique benchmarks, particularly regarding code-related tasks. It offers a holistic approach by including both code generation and code QA tasks with varying difficulties. Existing benchmarks primarily focus on general domains and may lack comprehensive evaluation. This benchmark provides two evaluation protocols, specifically basic and advanced, to thoroughly assess the critique abilities of LLMs. The advanced critique evaluation features fine-grained checklists for detailed analysis and the existing LLMs’ experimental results showcase the effectiveness of CodeCriticBench.

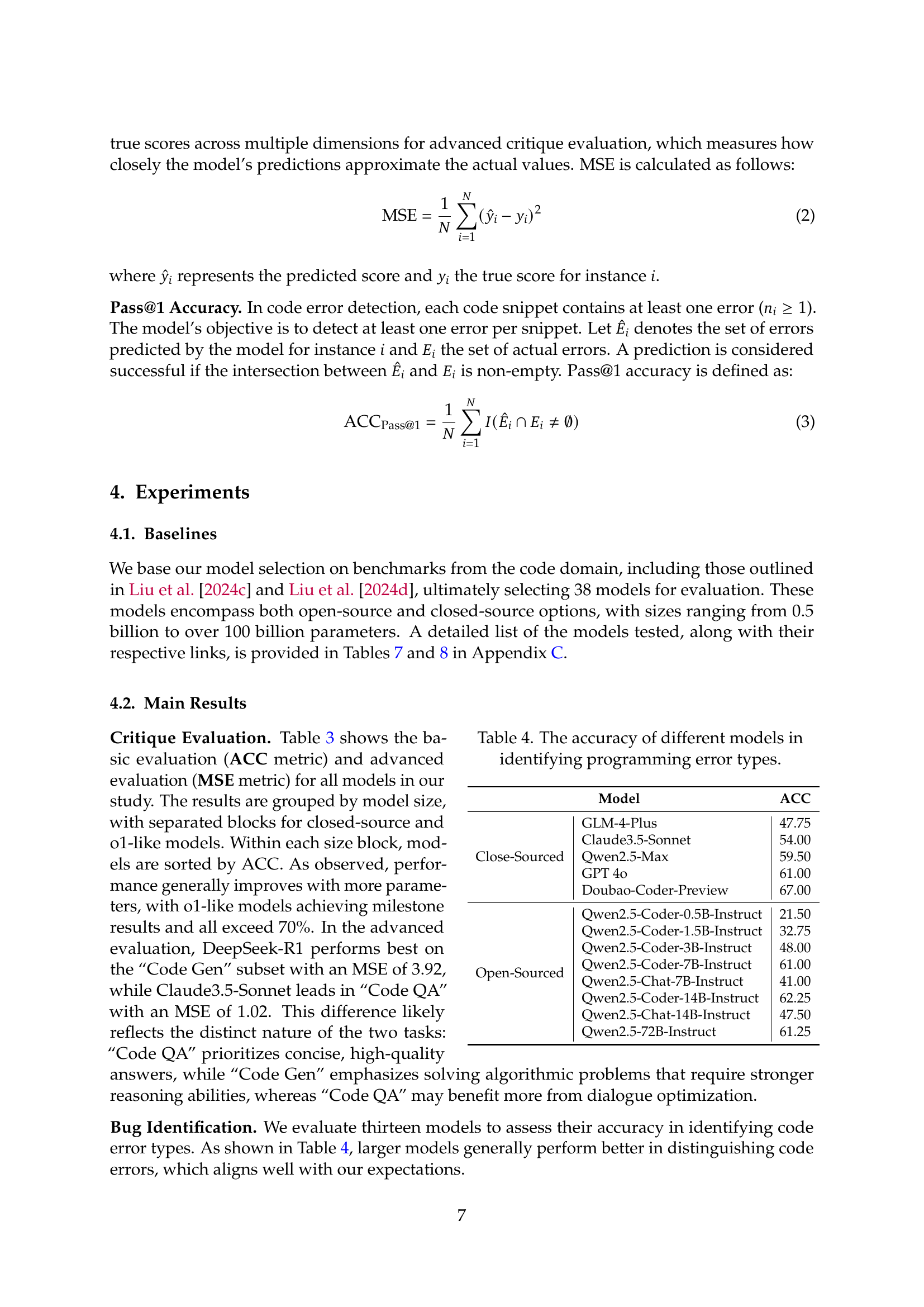

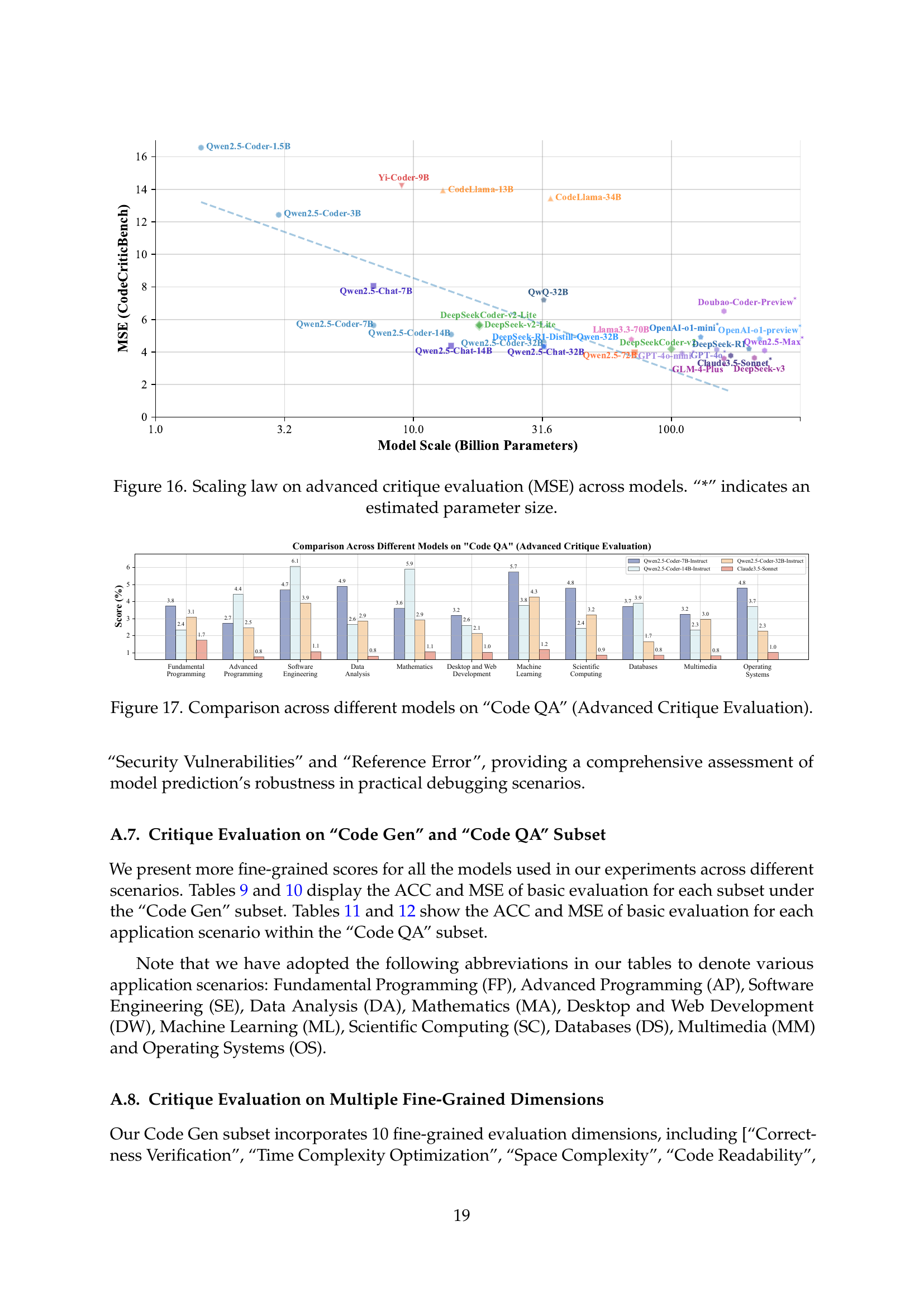

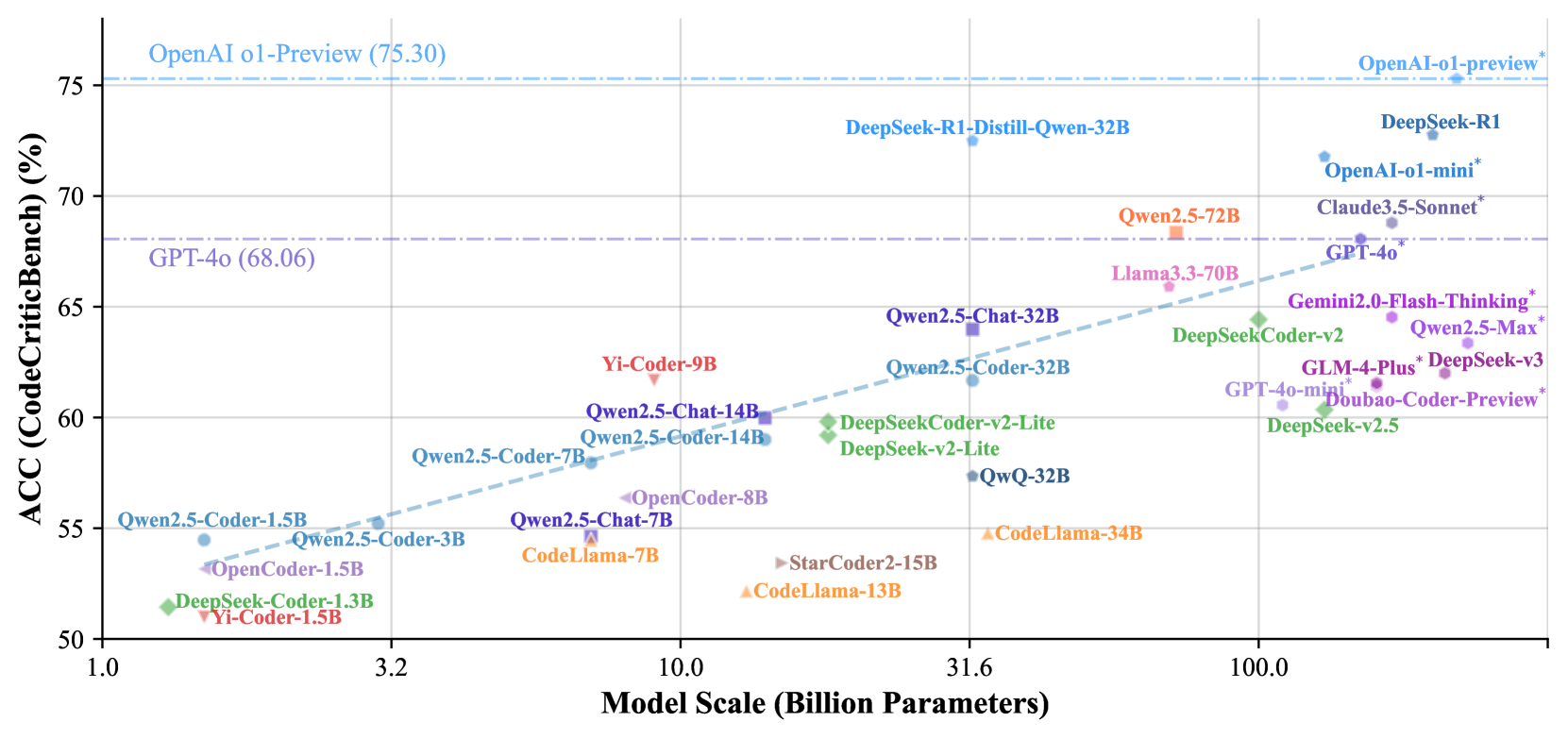

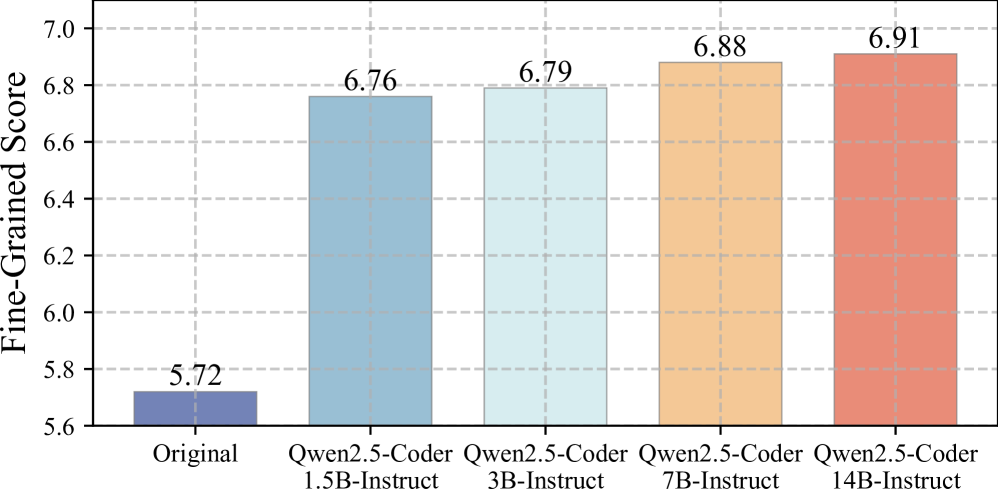

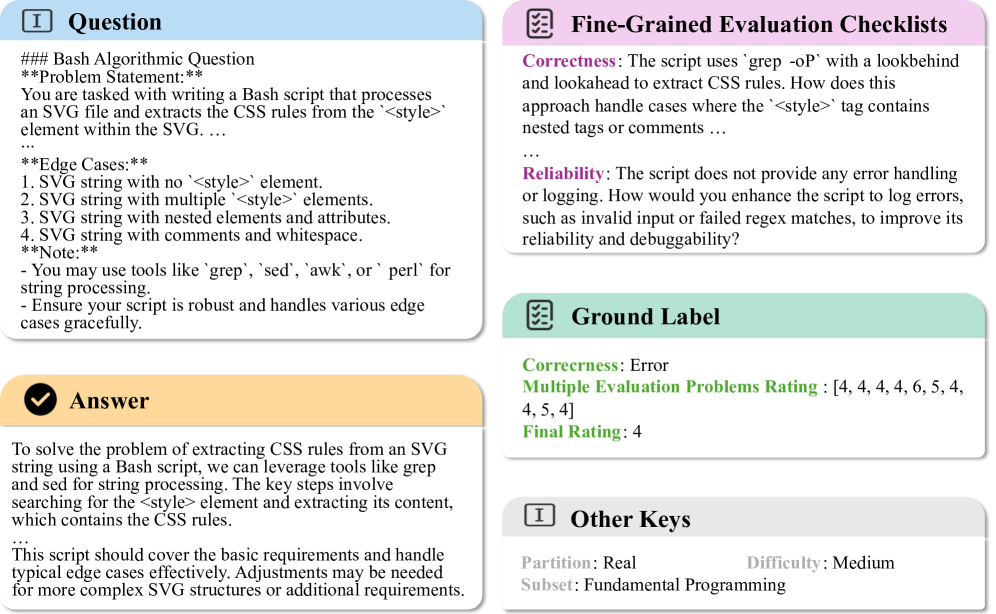

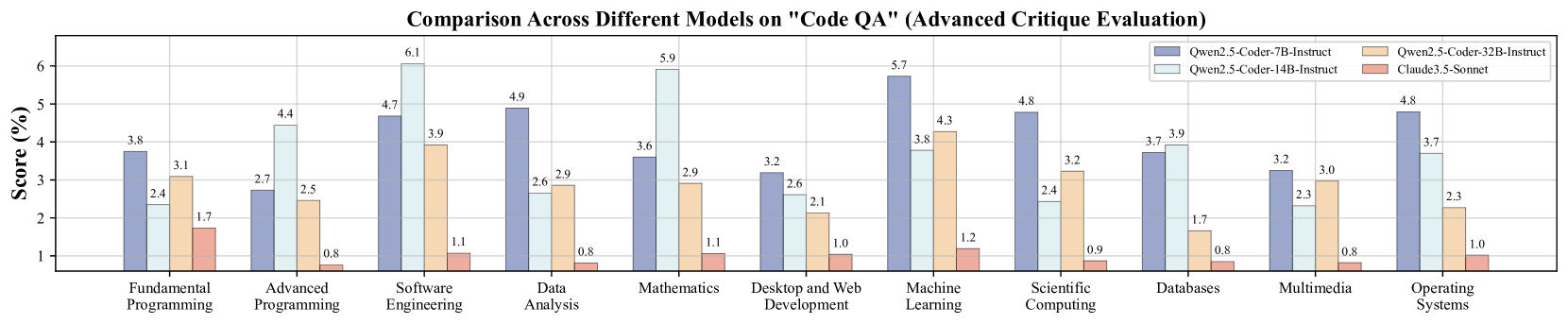

Scaling Analysis#

Scaling analysis is a critical aspect of evaluating the performance of language models. Model size is clearly important; with more parameters, accuracy increases, showcasing dataset strength. The relationship between parameters and performance validates the dataset’s robustness, which is seen in the clear improvement as model size increases. These scaling trends are essential for researchers to optimize resource allocation and develop more efficient models, while also further solidifying trust in the datasets used to train the model with reliable benchmarks. The robustness of models is what scaling laws measure.

Future: Repo Critique#

The prospect of a future ‘Repo Critique’ domain presents fascinating challenges. It envisions LLMs evaluating code repositories, demanding nuanced comprehension. This goes beyond single-file analysis, requiring understanding of inter-file dependencies, project structure, commit history, and collaborative dynamics. This area will test LLMs’ ability to reason about code at multiple levels of abstraction. It will also necessitate incorporating contextual information like documentation, issue trackers, and version control metadata. Developing robust metrics will be crucial, perhaps involving simulations of real-world development tasks. The scope is huge, needing LLMs to consider quality and security within the context of practical coding scenarios and team collaboration. In essence, the ‘Repo Critique’ sets high benchmarks to fully evaluate the code reasoning capabilities of LLMs within realistic, intricate and time based software projects.

More visual insights#

More on figures

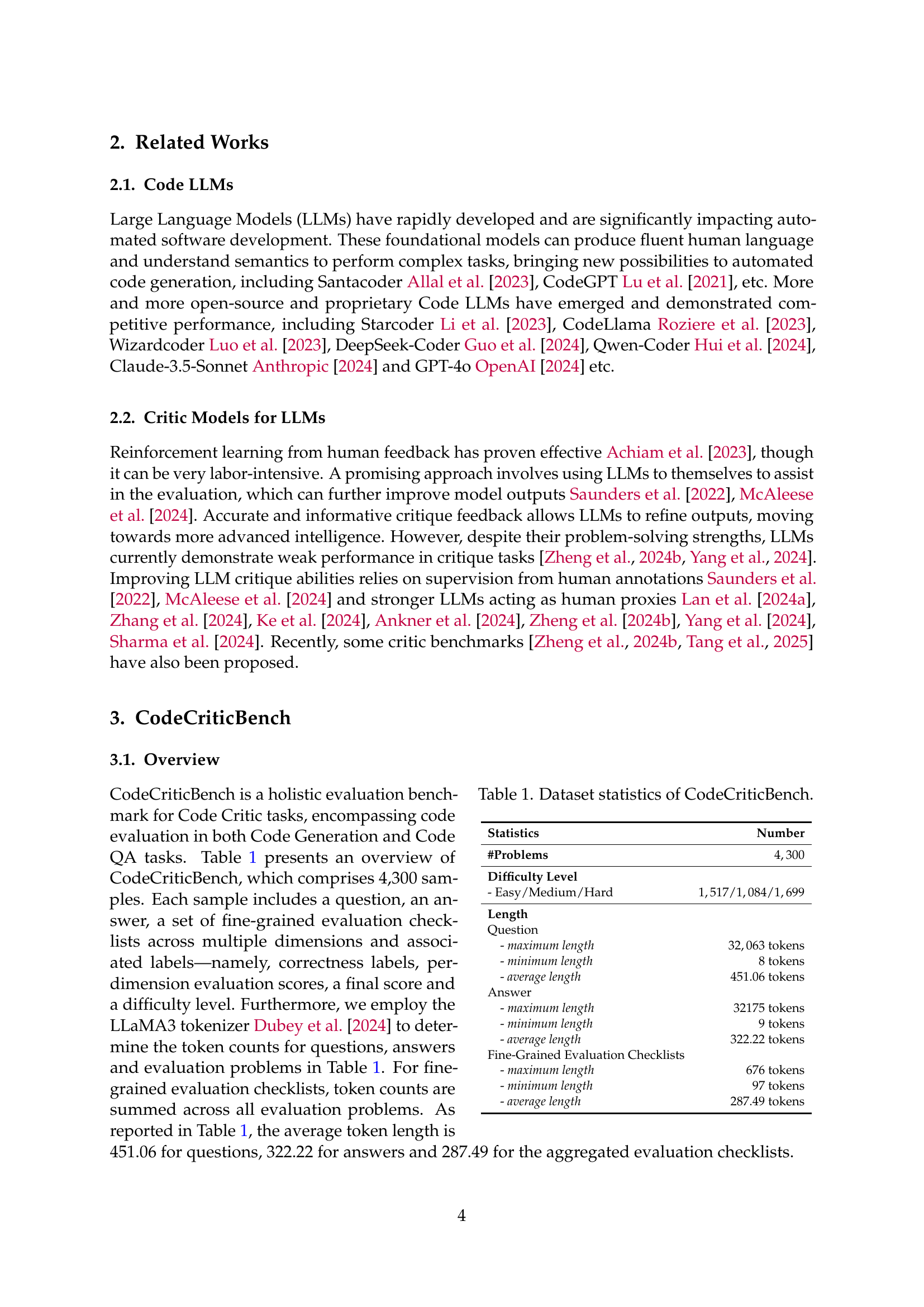

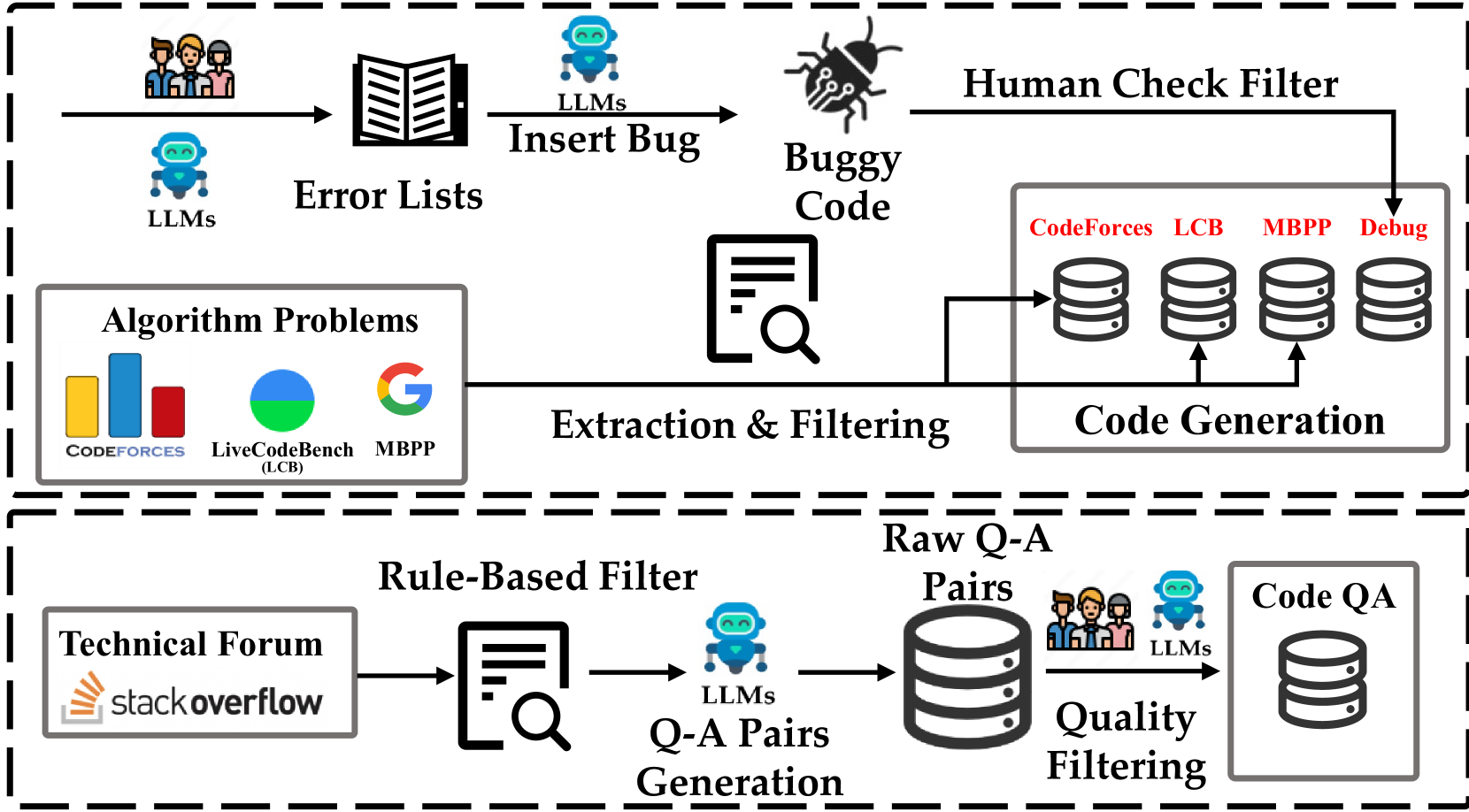

🔼 The figure illustrates the process of collecting data for the CodeCriticBench benchmark. It begins with selecting algorithm problems from CodeForces, MBPP, and LiveCodeBench datasets. These problems are then used to generate code using LLMs. A bug insertion process is implemented, introducing various error types into the correct code generated by LLMs. These samples undergo filtering rounds: first a sandbox execution to confirm error triggering, then a manual review to confirm error alignment with the intended categories. For the code QA task, a rule-based filtering process first cleans the raw question-answer pairs collected from StackOverflow. Qwen2.5-72B is then used to generate new questions, while manual filtering and LLM-assisted reviews ensure high quality.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of data collection process.

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the size of large language models (LLMs) and their accuracy in basic code critique tasks. The x-axis represents the number of parameters (model size) in billions, while the y-axis shows the accuracy (ACC) in percentage. Each point represents a specific LLM, and the size of the points may represent the model’s relative performance. The plot indicates a general trend of improved accuracy as the model size increases. The ‘*’ symbol is used to denote that the parameter size is estimated for certain models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Scaling law on basic critique evaluation (ACC) across models. “*” indicates an estimated parameter size.

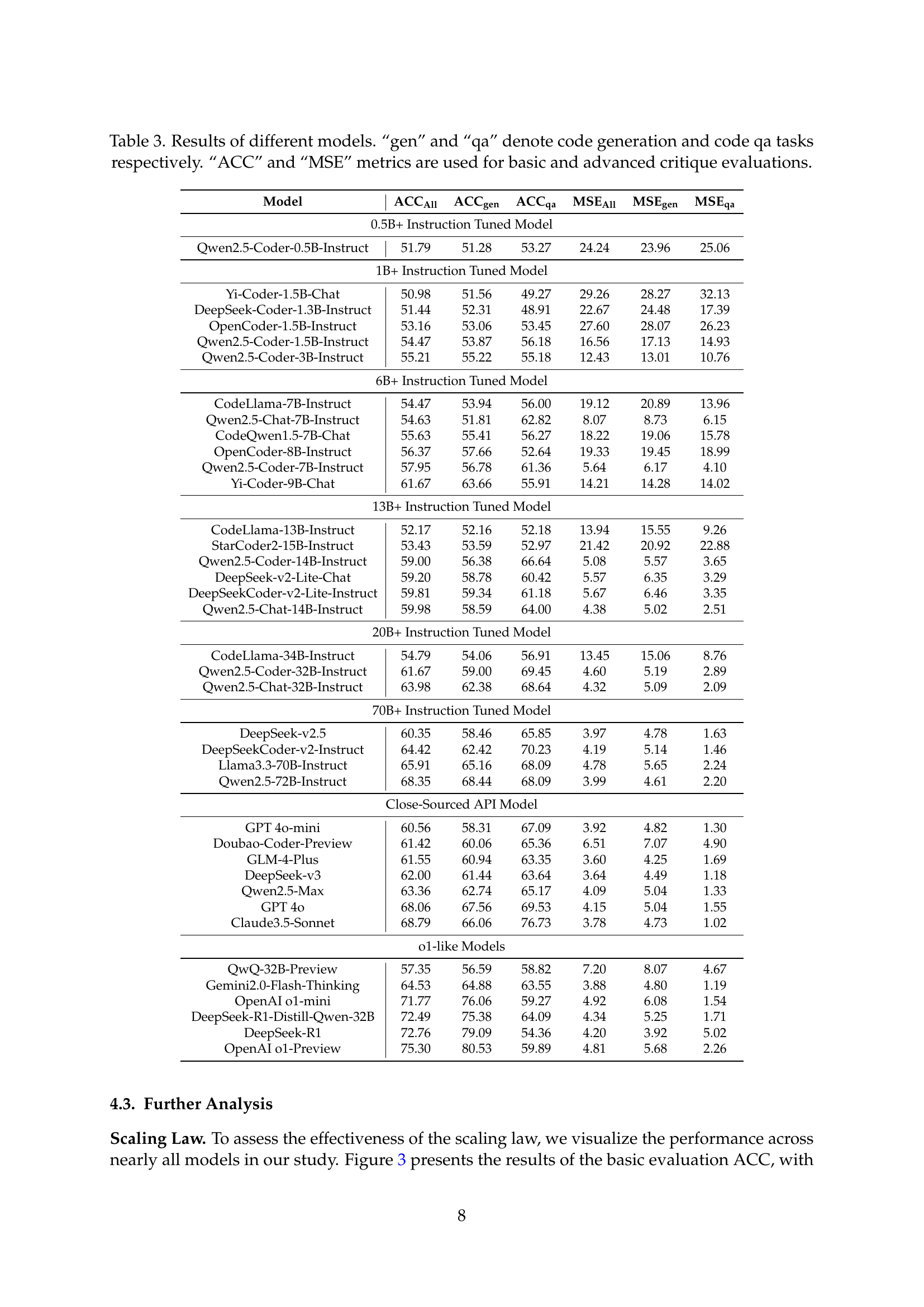

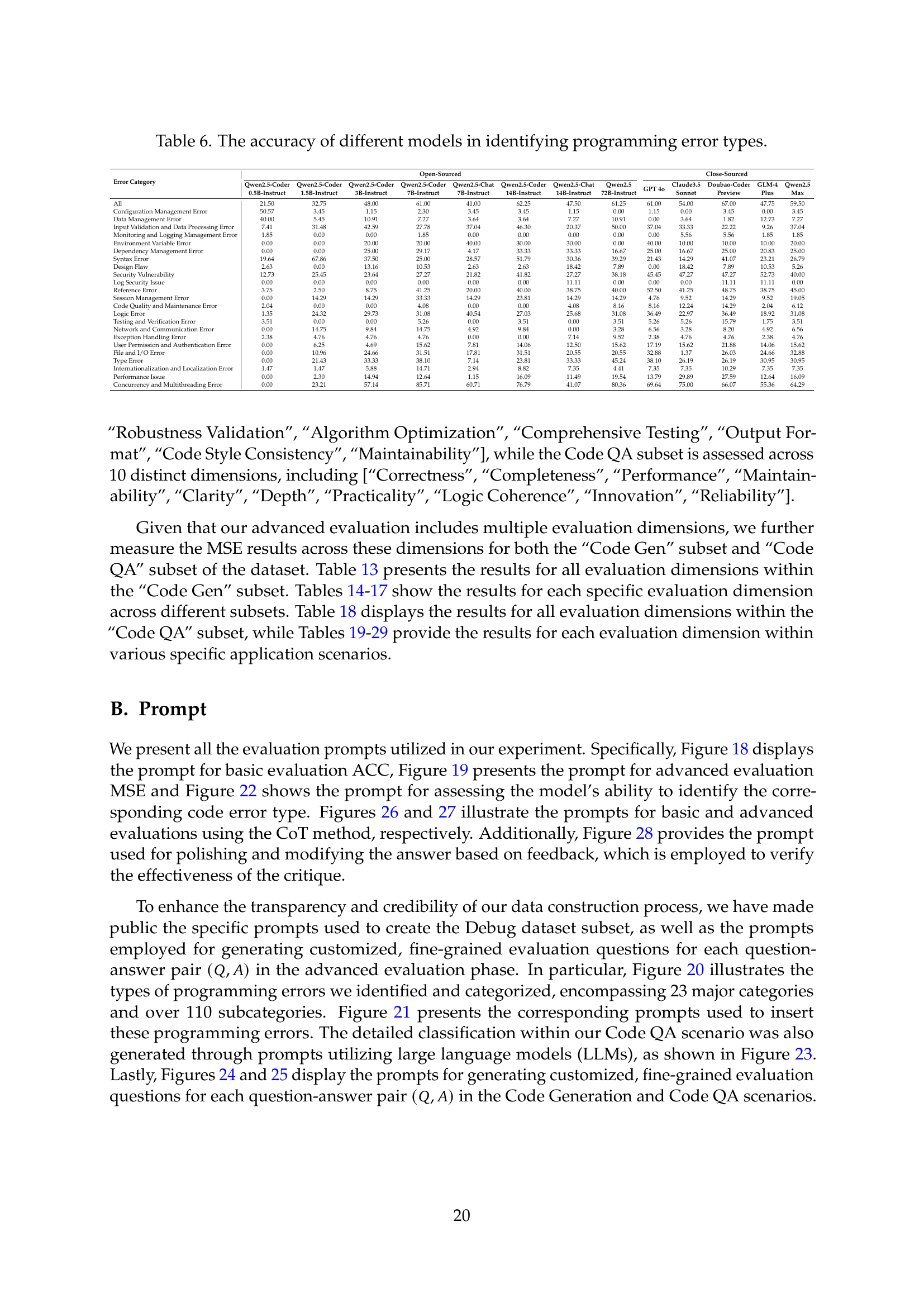

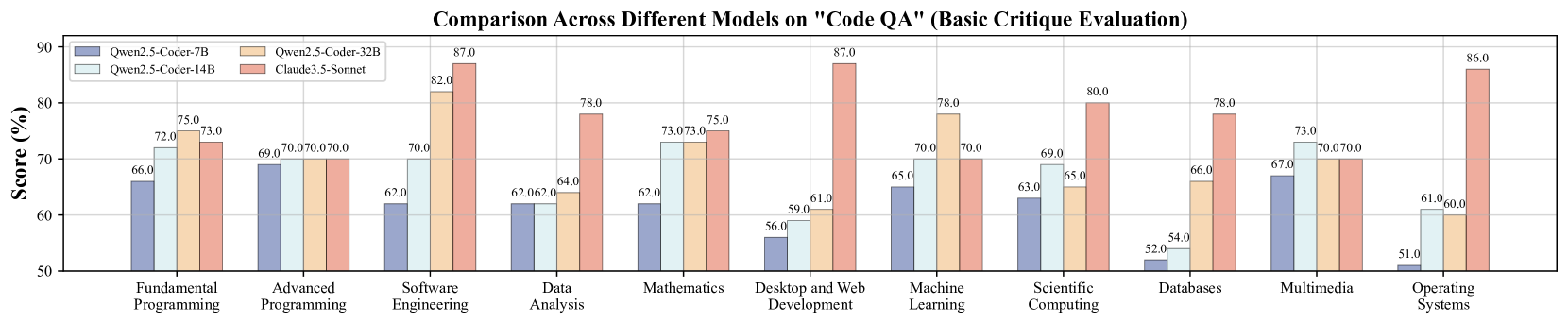

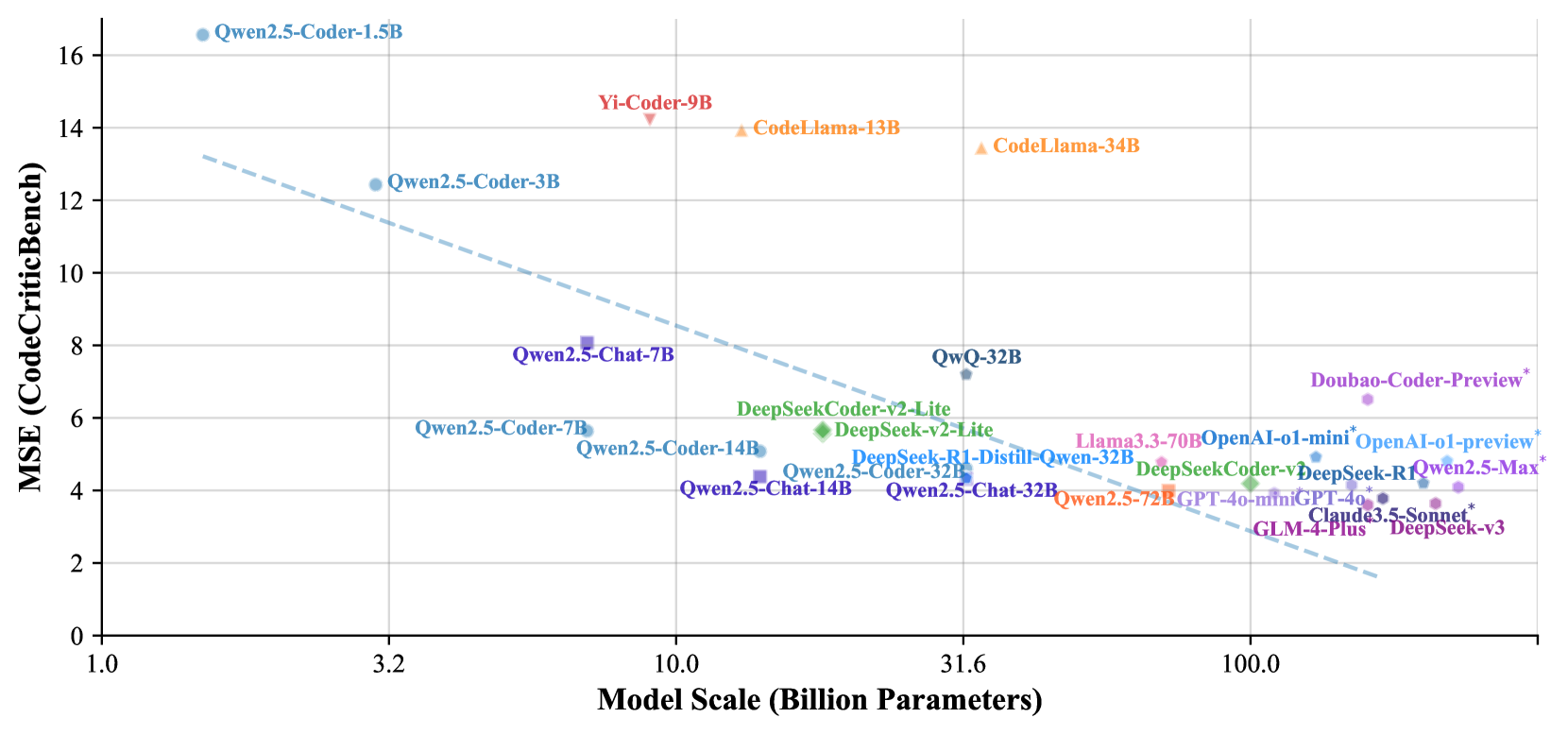

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of the performance of various models on the Code QA task, specifically focusing on the basic critique evaluation. It showcases how different models, categorized by size, perform on the task of evaluating code correctness based on the accuracy metric. The chart likely presents a bar graph, where each bar represents a model’s performance, and models are grouped by parameter size. It provides a visual representation of the effectiveness of different models in correctly identifying errors or assessing the accuracy of code provided in response to natural language questions.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison across different models on “Code QA” (Basic Critique Evaluation).

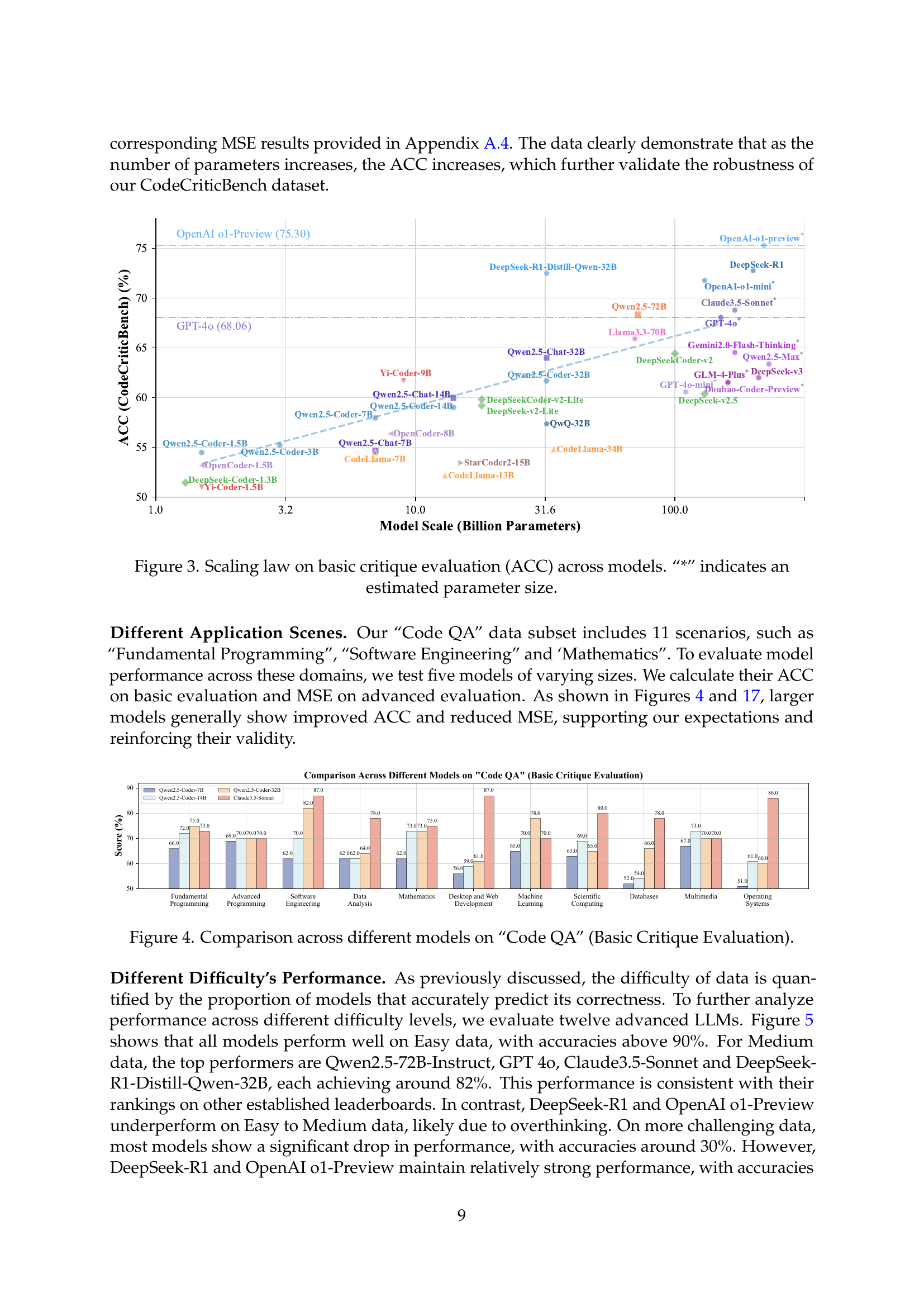

🔼 This figure displays the accuracy (ACC) of various large language models (LLMs) in performing basic code critique tasks, categorized by the difficulty level of the tasks. The difficulty levels (Easy, Medium, Hard) are determined by the percentage of LLMs that correctly answer the questions. The x-axis represents the different LLMs tested, and the y-axis shows the accuracy, providing a visual comparison of model performance across different difficulty levels.

read the caption

Figure 5: Model performance (ACC) on different difficulty levels (Basic Critique Evaluation) .

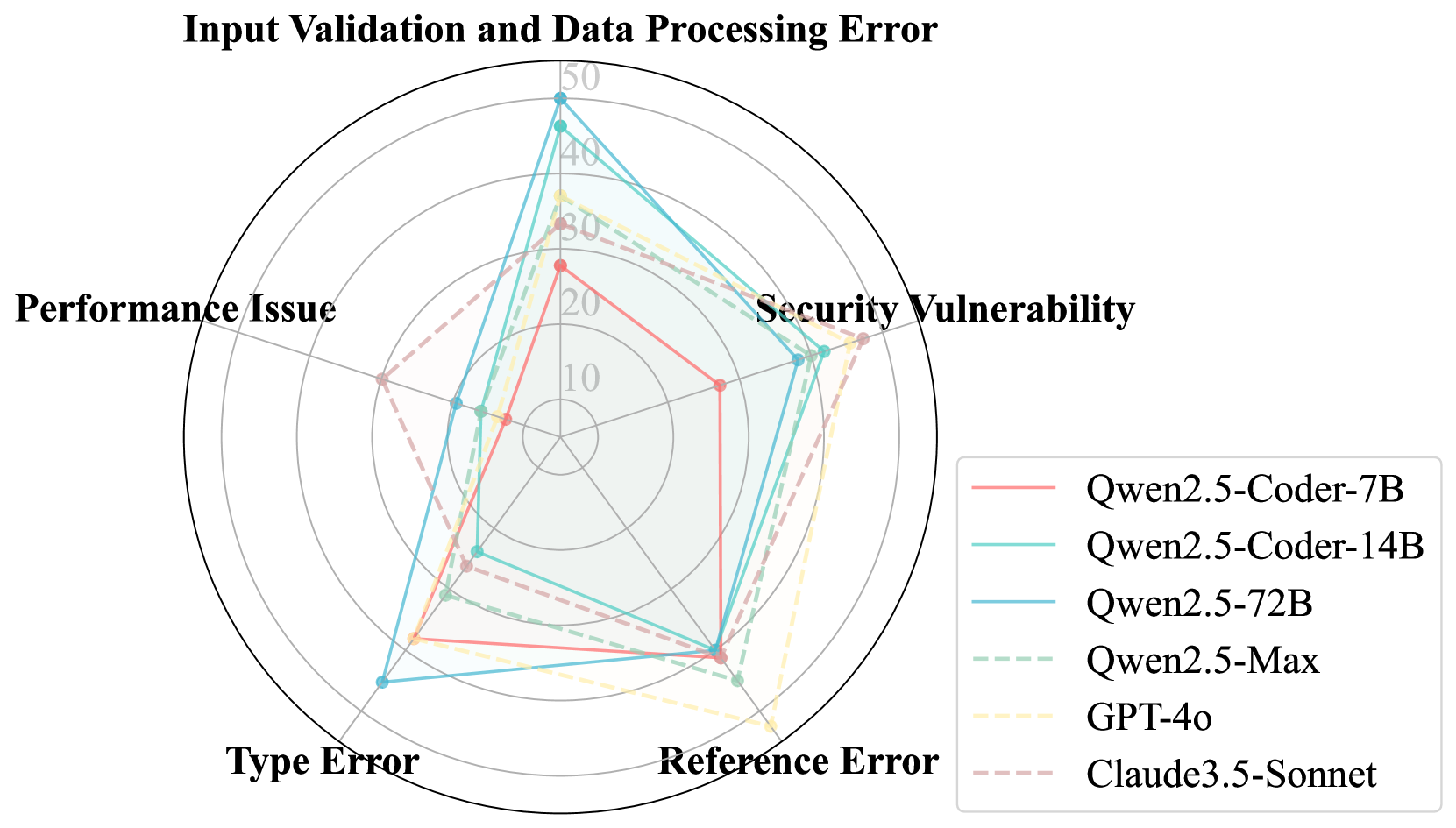

🔼 This figure visualizes the performance of various LLMs in identifying five common programming errors: Input Validation and Data Processing Errors, Performance Issues, Security Vulnerabilities, Type Errors, and Reference Errors. The accuracy of each model in correctly identifying these errors is presented, allowing for a comparison across different models. The results show that model accuracy generally improves with increased model size, reflecting the enhanced capabilities of larger models in identifying and classifying these types of programming errors.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparison of the accuracy of different models in identifying five common programming error types.

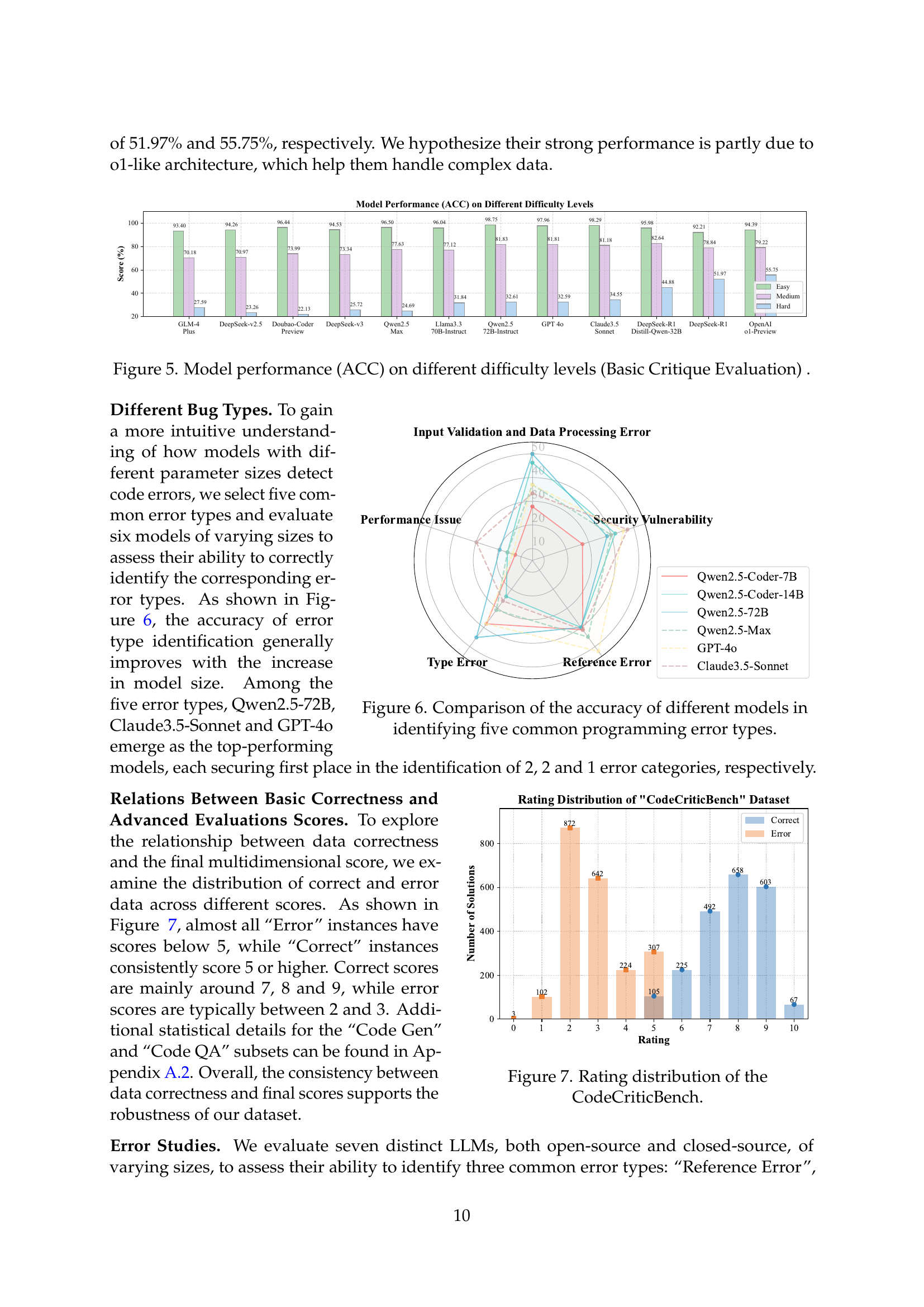

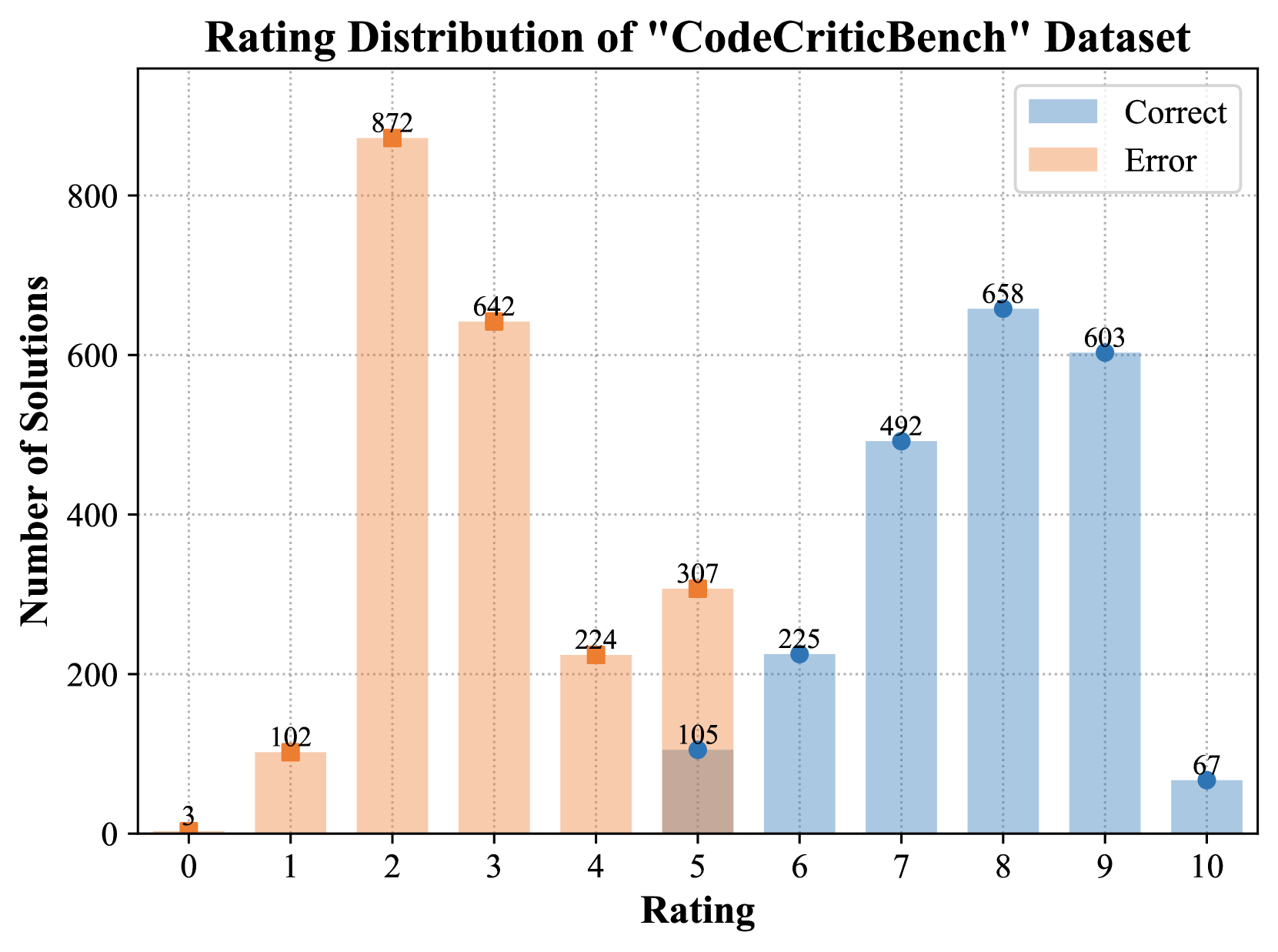

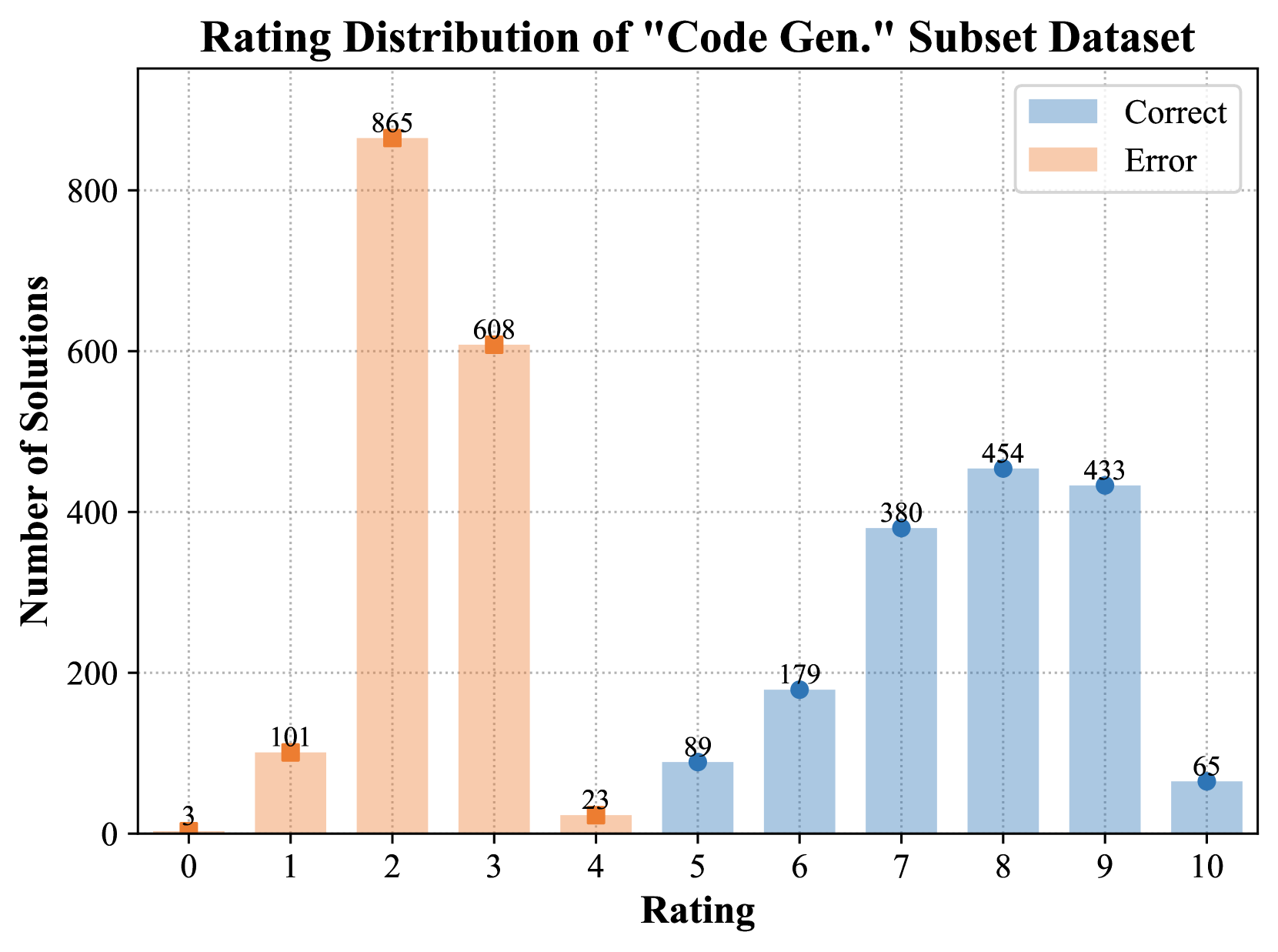

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of ratings in the CodeCriticBench dataset. It displays the number of code samples that received each rating (1-10), separately for correct and incorrect code solutions. This visualization helps to understand the difficulty level and quality distribution of the benchmark problems.

read the caption

Figure 7: Rating distribution of the CodeCriticBench.

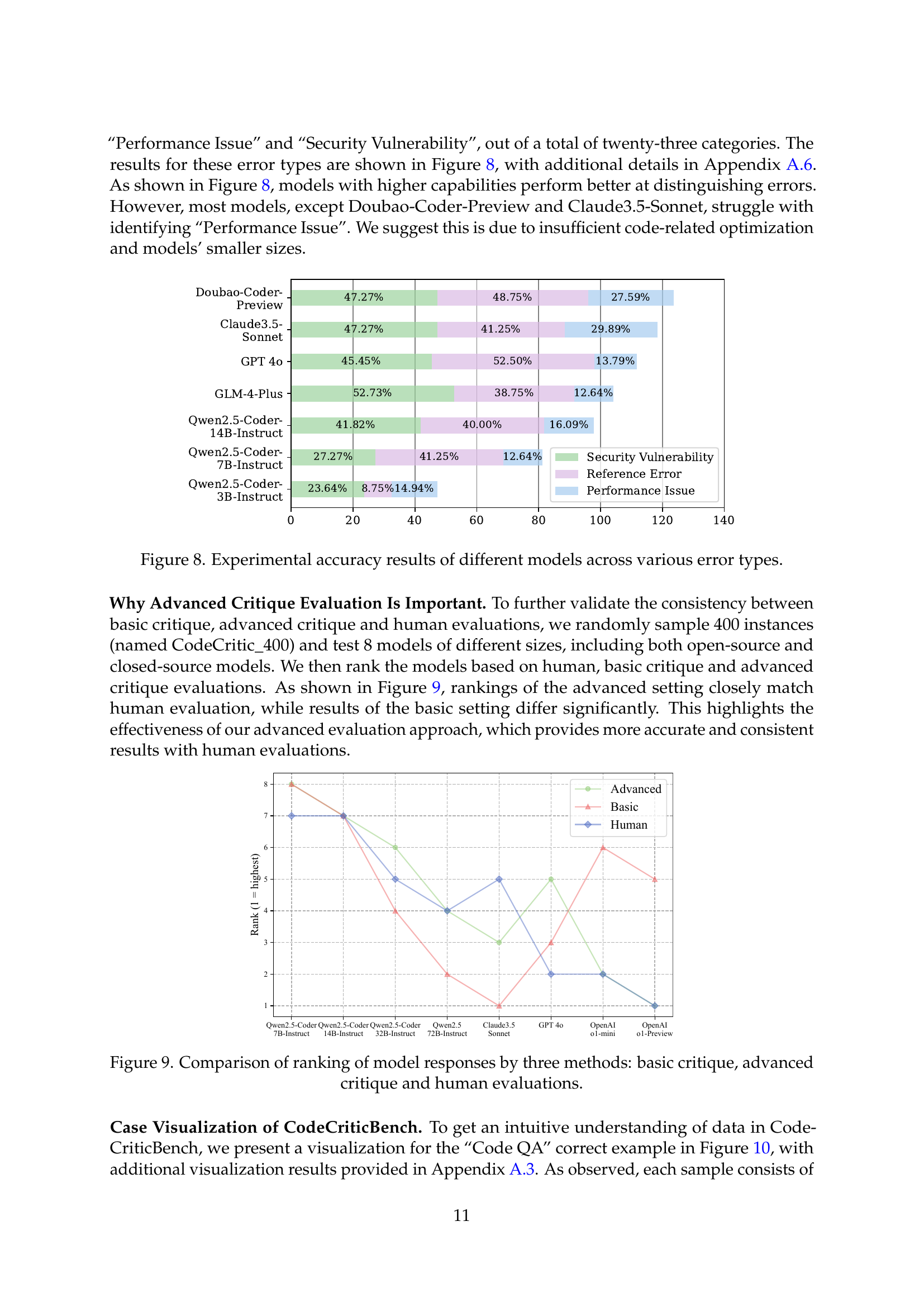

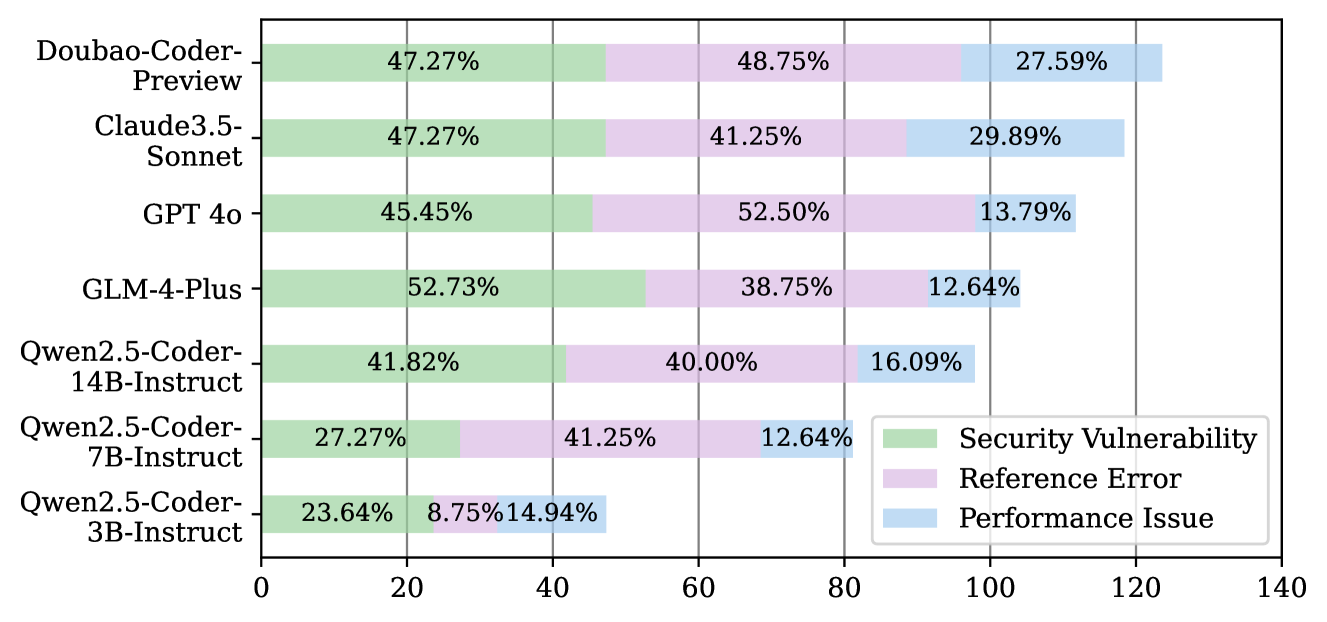

🔼 The figure shows the accuracy of various large language models in identifying different types of programming errors. The x-axis represents the different error types (Performance Issues, Security Vulnerabilities, Reference Errors, etc.), while the y-axis shows the accuracy percentage. Each bar represents a different model, with colors differentiating between open-source and closed-source models. The model’s size (in terms of parameters) is also implicitly included by grouping similar sized models. This allows for a comparison of accuracy across various error types and model sizes.

read the caption

Figure 8: Experimental accuracy results of different models across various error types.

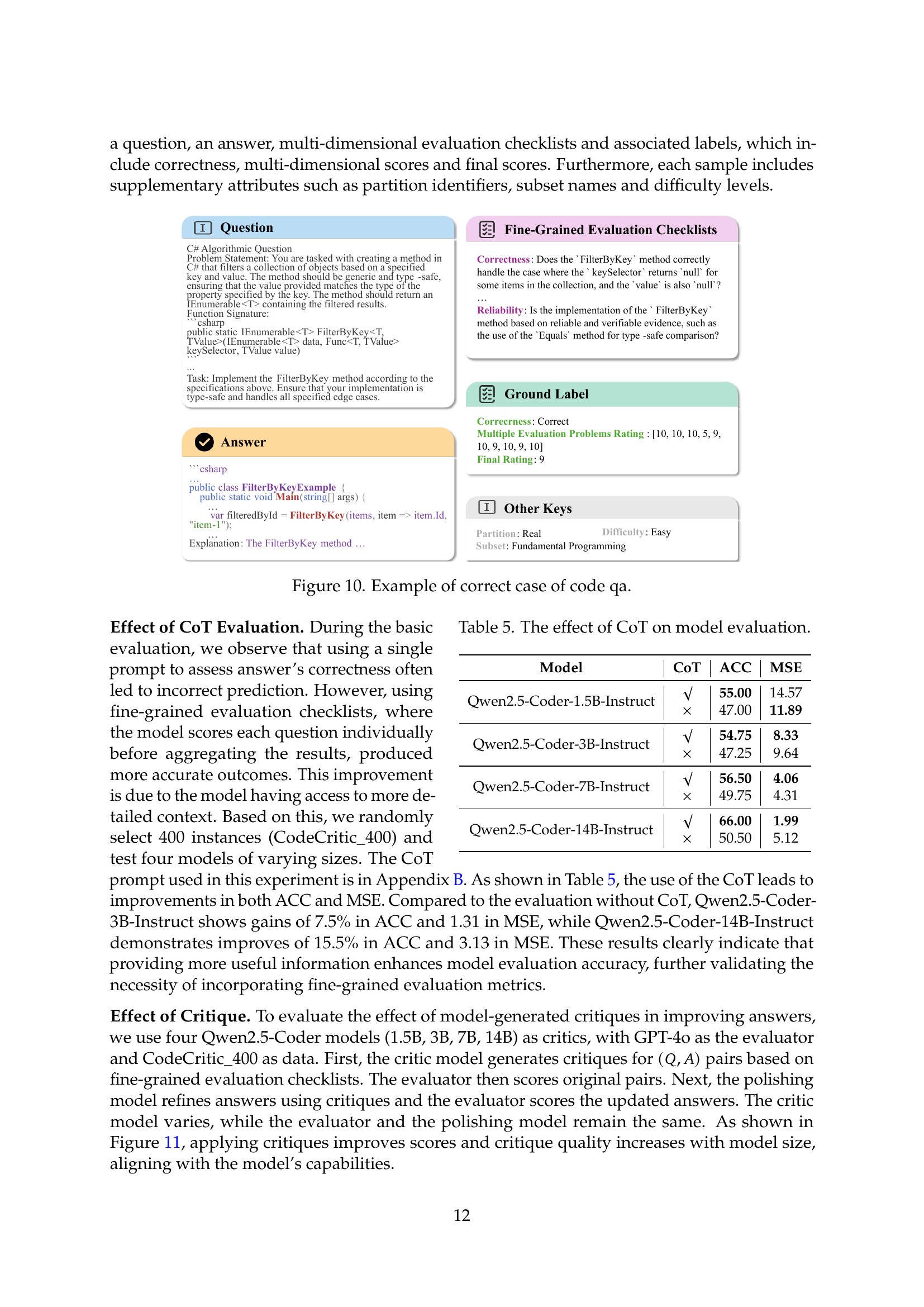

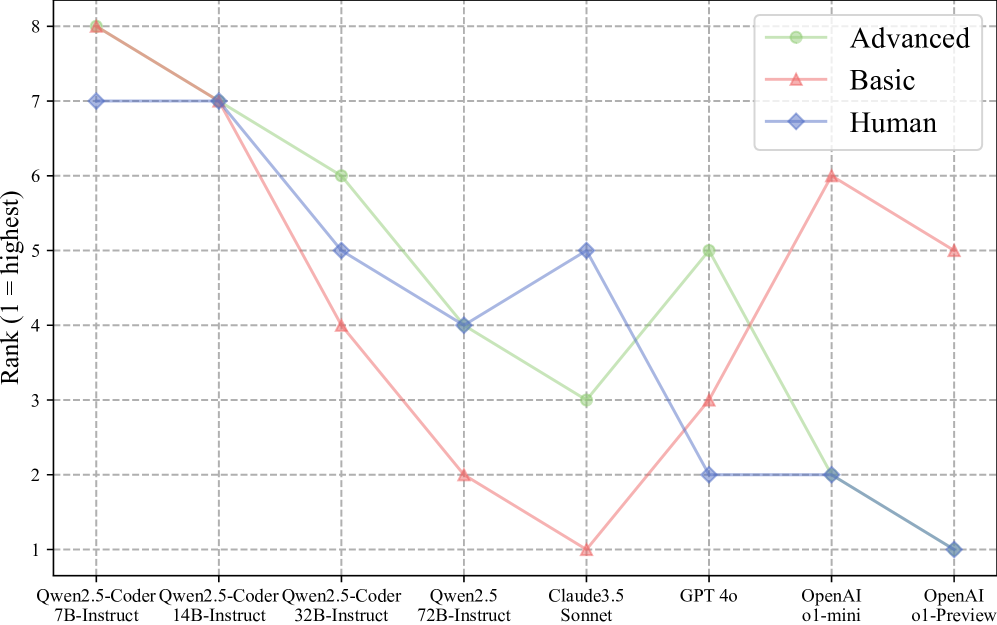

🔼 This figure compares the ranking of large language models (LLMs) based on three different evaluation methods: basic critique, advanced critique, and human evaluation. The x-axis represents different LLMs, and the y-axis shows their rank across the three methods. A lower rank indicates better performance. The figure visually demonstrates whether the different evaluation methods yield consistent ranking results and helps understand the correlation between automated evaluation (basic and advanced critique) and human judgment in evaluating LLM code critique capabilities. The goal is to assess the effectiveness and alignment of the automated critique evaluation methods with human assessment.

read the caption

Figure 9: Comparison of ranking of model responses by three methods: basic critique, advanced critique and human evaluations.

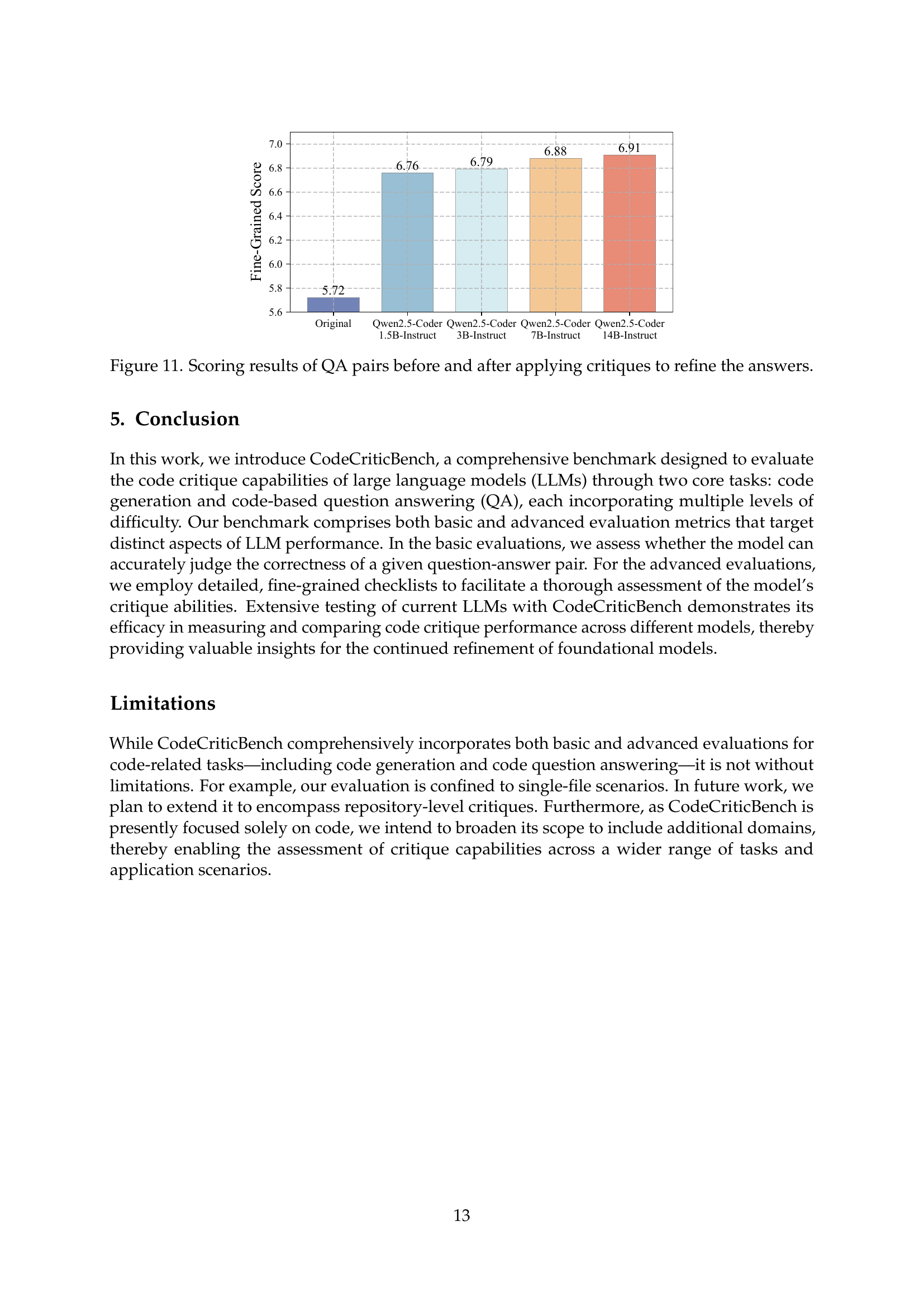

🔼 This figure shows a sample from the Code QA subset of the CodeCriticBench dataset. It shows an example of a correct answer provided by an LLM. The figure includes the question, the correct answer, the fine-grained evaluation checklists and associated labels, such as correctness and overall score.

read the caption

Figure 10: Example of correct case of code qa.

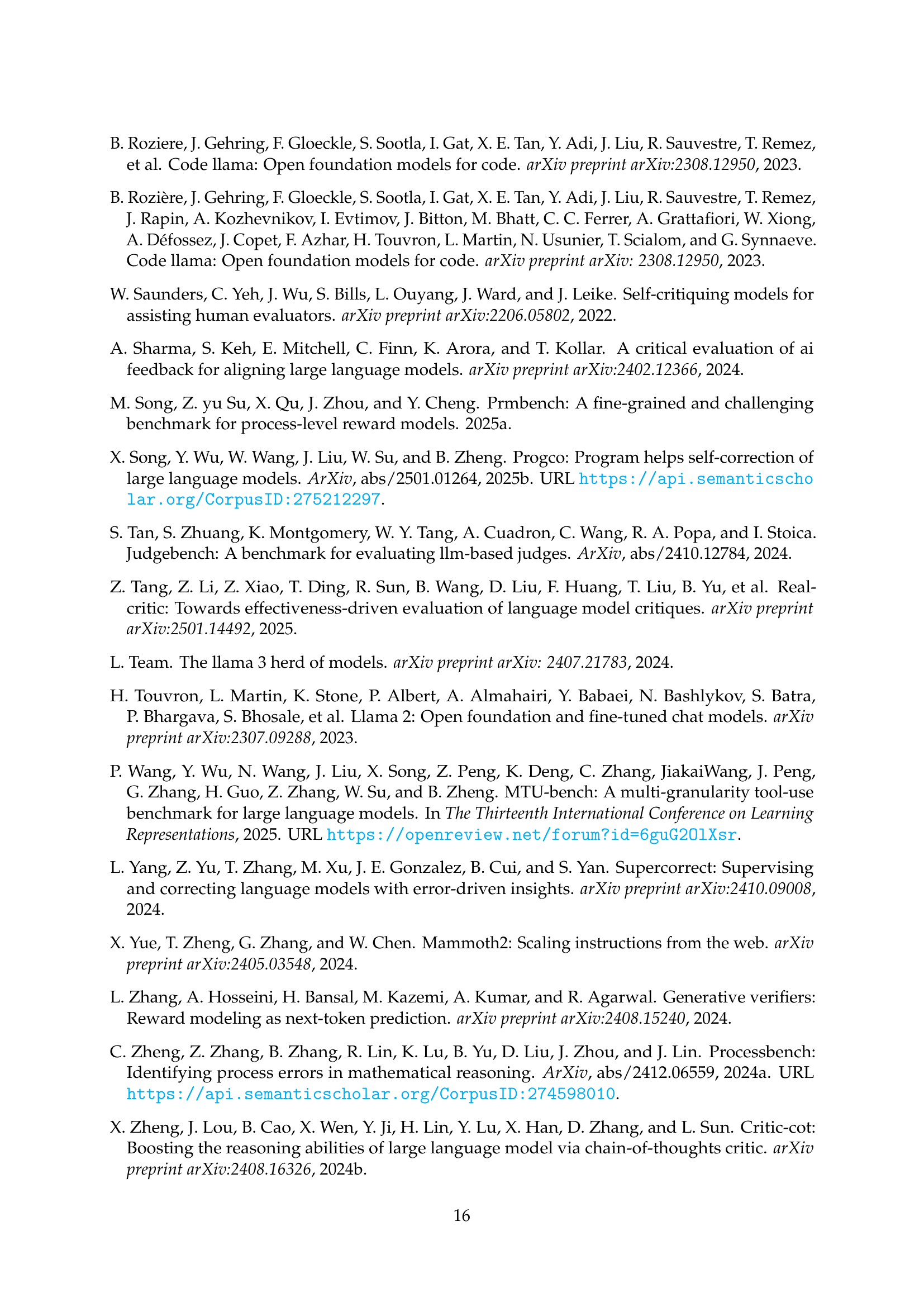

🔼 This figure displays the results of code question-answering (QA) pairs before and after applying critiques generated by LLMs. It illustrates how leveraging model-generated critiques can lead to improved scores for QA pairs by enhancing the answers. The figure likely shows a comparison of scores (e.g., accuracy or a more nuanced evaluation metric) before and after the critique intervention. This visual representation demonstrates the effectiveness of the model’s critique capability in improving the overall quality of the answers.

read the caption

Figure 11: Scoring results of QA pairs before and after applying critiques to refine the answers.

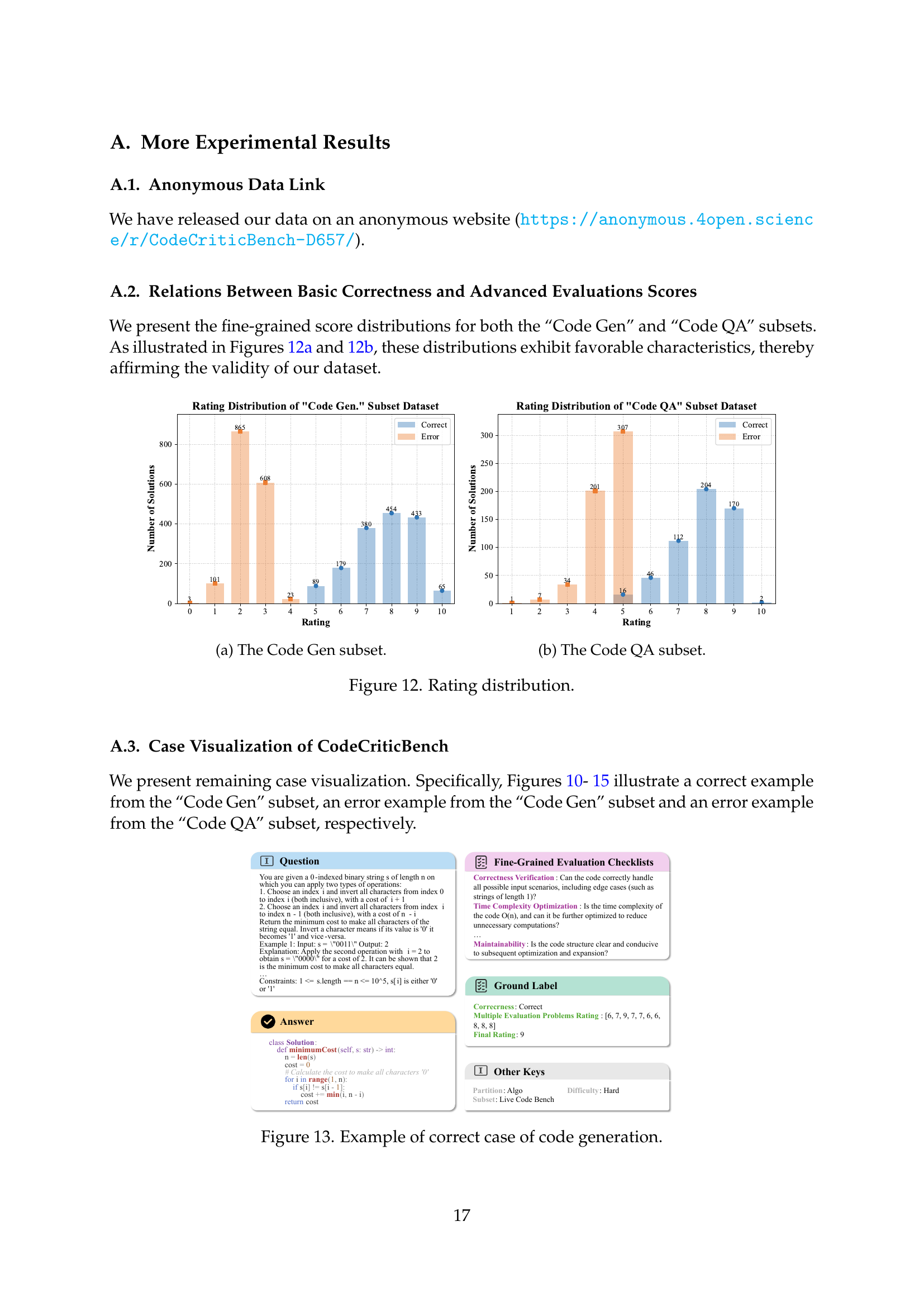

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of ratings for the Code Generation subset of the CodeCriticBench dataset. The x-axis represents the rating score (from 1 to 10), and the y-axis represents the number of code samples. The bars are separated by whether the code sample was correctly generated or not. This visualization helps assess the quality and difficulty of the Code Generation tasks within the benchmark.

read the caption

(a) The Code Gen subset.

🔼 Figure 12(b) shows the distribution of ratings for the Code QA subset of the CodeCriticBench dataset. The x-axis represents the rating score, ranging from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating better quality. The y-axis represents the number of samples with that score. The two bars for each rating show the separate counts for ‘Correct’ and ‘Error’ answers. The distribution helps illustrate the dataset’s balance in difficulty levels and the correlation between the basic correctness label and the fine-grained, multi-dimensional evaluation scores.

read the caption

(b) The Code QA subset.

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of ratings for the CodeCriticBench dataset, separated into the Code Generation and Code QA subsets. The histograms illustrate the frequency of different rating scores (presumably 1-10) given by evaluators to each code example. The distribution helps to demonstrate the difficulty level and the quality of the data samples within each task type. A balanced distribution of ratings across the scores would suggest a well-designed benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 12: Rating distribution.

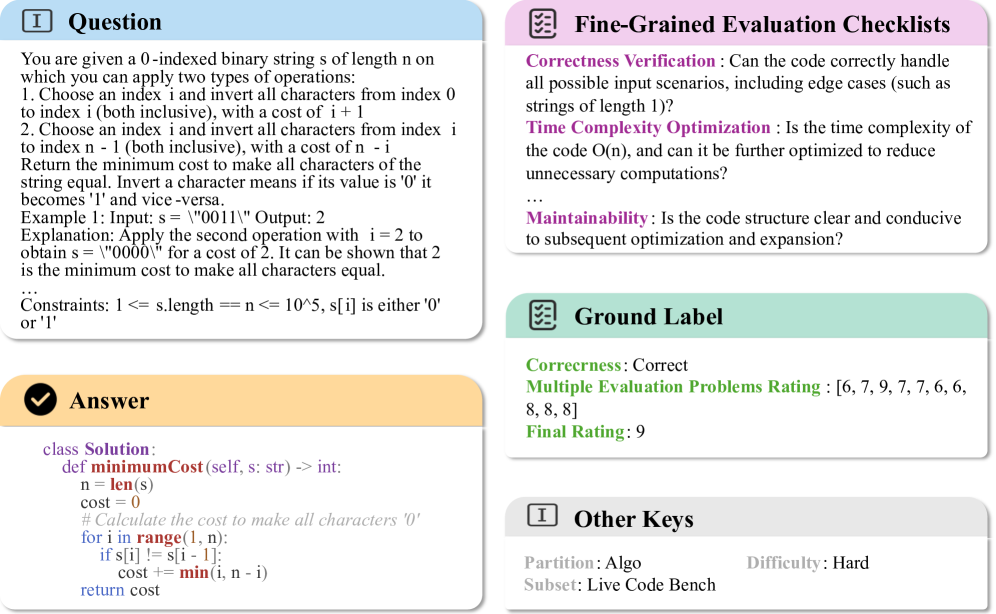

🔼 Figure 13 shows an example from the CodeCriticBench dataset where the LLM correctly generated code. The figure displays the problem statement, the constraints, the example input/output, the generated code, and the evaluation results. The problem requires the LLM to write a function that calculates the minimum cost to make all characters in a binary string equal using two types of operations. The evaluation shows that the generated code passed the correctness verification and time complexity optimization checks, indicating that the model successfully performed the code generation task.

read the caption

Figure 13: Example of correct case of code generation.

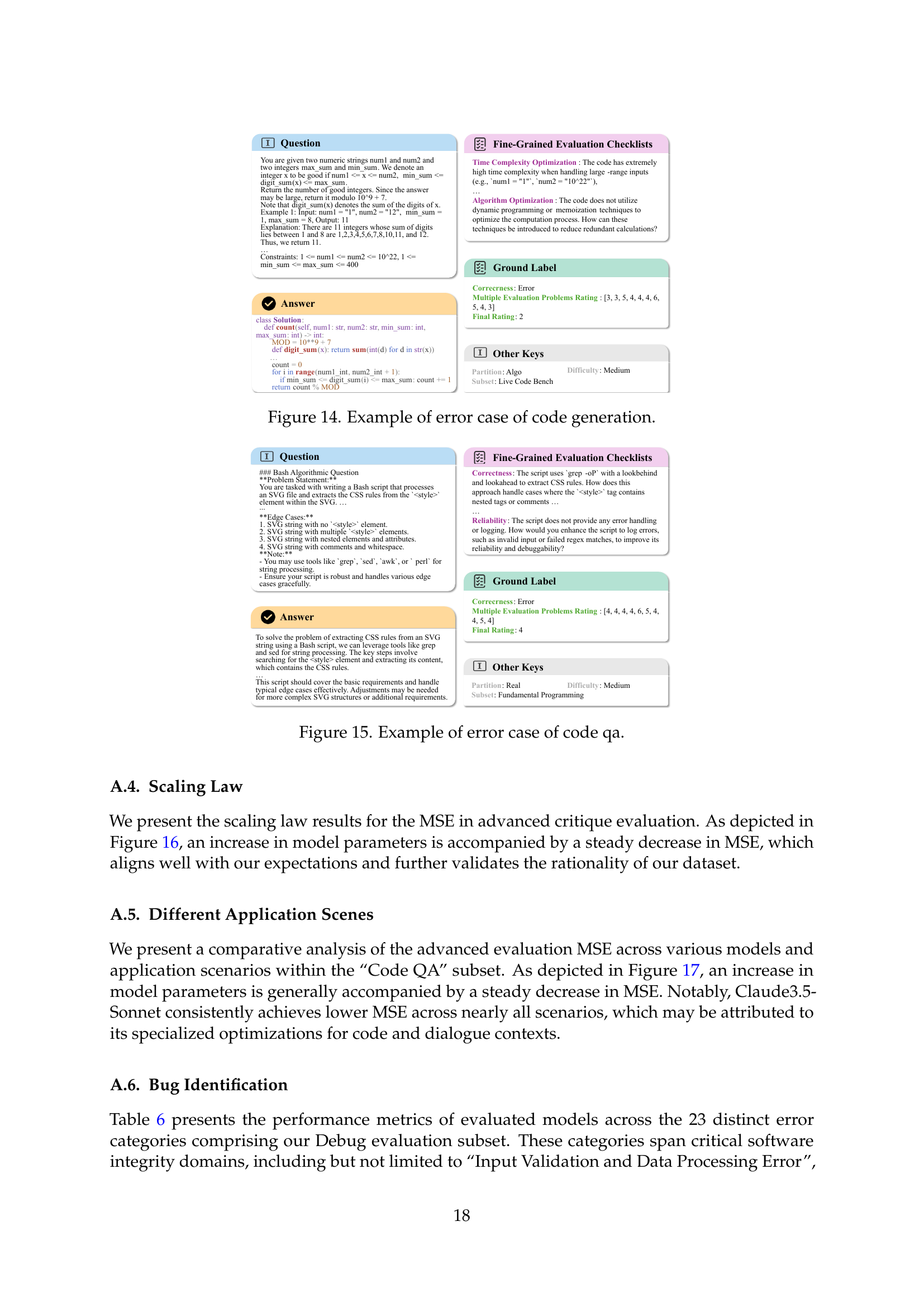

🔼 This figure shows an example from the CodeCriticBench dataset where the generated code is incorrect. It displays the question, the incorrect code generated by a large language model (LLM), the fine-grained evaluation checklist showing the errors, and the final evaluation rating. This example highlights the benchmark’s capability to identify errors in code generation and provide detailed feedback on LLM performance.

read the caption

Figure 14: Example of error case of code generation.

🔼 This figure shows an example of an erroneous response from a large language model (LLM) to a code-based question-answering (QA) task. The example demonstrates an incomplete and flawed response. The provided answer lacks critical elements, fails to handle edge cases, and contains logical errors. The figure highlights the challenges LLMs face in accurately evaluating code and the need for more robust evaluation methods. The details shown include the question, the incorrect LLM answer, and a set of detailed checklists evaluating the response against various quality dimensions, including correctness, time complexity, and maintainability.

read the caption

Figure 15: Example of error case of code qa.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the relationship between the number of parameters in a language model and its performance on advanced code critique tasks. The mean squared error (MSE) is used as the evaluation metric, representing the difference between the model’s predicted scores and human-assigned scores across multiple fine-grained evaluation dimensions. As the number of parameters in the model increases, the MSE generally decreases. This indicates that larger models tend to provide more accurate and comprehensive feedback for code critique.

read the caption

Figure 16: Scaling law on advanced critique evaluation (MSE) across models. “*” indicates an estimated parameter size.

Full paper#