TL;DR#

Current computer vision models struggle with real-world usability in referring to specific people in images because existing benchmarks focus on one-to-one referring and neglect multiple individuals. Existing models don’t capture attributes, spatial relations, interactions, and reasoning effectively.

To address these issues, the paper introduces HumanRef, a new dataset designed for human referring tasks, and RexSeek, a novel model designed for this task. The new dataset includes 103,028 referring statements for multiple instances, and model integrates a multimodal large language model (MLLM) with an object detection framework.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the limitations of existing human referring models by introducing a new benchmark and a novel MLLM. It opens new avenues for research in human-centric CV, encouraging the development of more robust and generalizable models.

Visual Insights#

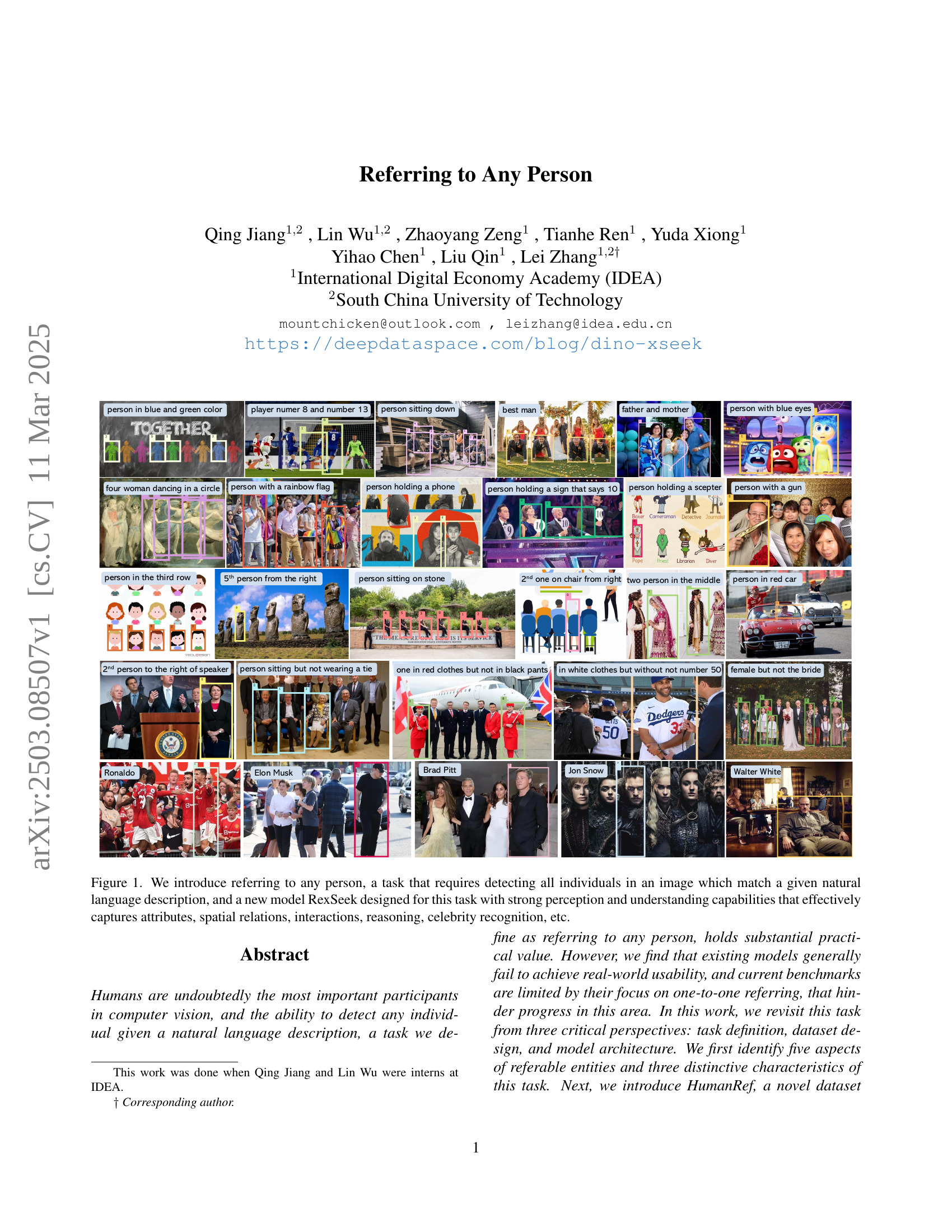

🔼 Figure 1 showcases the ‘Referring to Any Person’ task, a new computer vision challenge. The task involves identifying every person in an image that matches a given natural language description. The figure displays a wide variety of example images and their corresponding descriptions, highlighting the complexity and diversity of the task. These descriptions range from simple attributes (e.g., ‘person in blue’) to complex spatial relationships (e.g., ‘5th person from the right’) and even include celebrity recognition (e.g., ‘Elon Musk’). The figure also introduces RexSeek, a novel model specifically designed to tackle this challenge, demonstrating its ability to effectively capture various attributes, spatial relationships, interactions, and reasoning involved in accurately identifying the described individuals.

read the caption

Figure 1: We introduce referring to any person, a task that requires detecting all individuals in an image which match a given natural language description, and a new model RexSeek designed for this task with strong perception and understanding capabilities that effectively captures attributes, spatial relations, interactions, reasoning, celebrity recognition, etc.

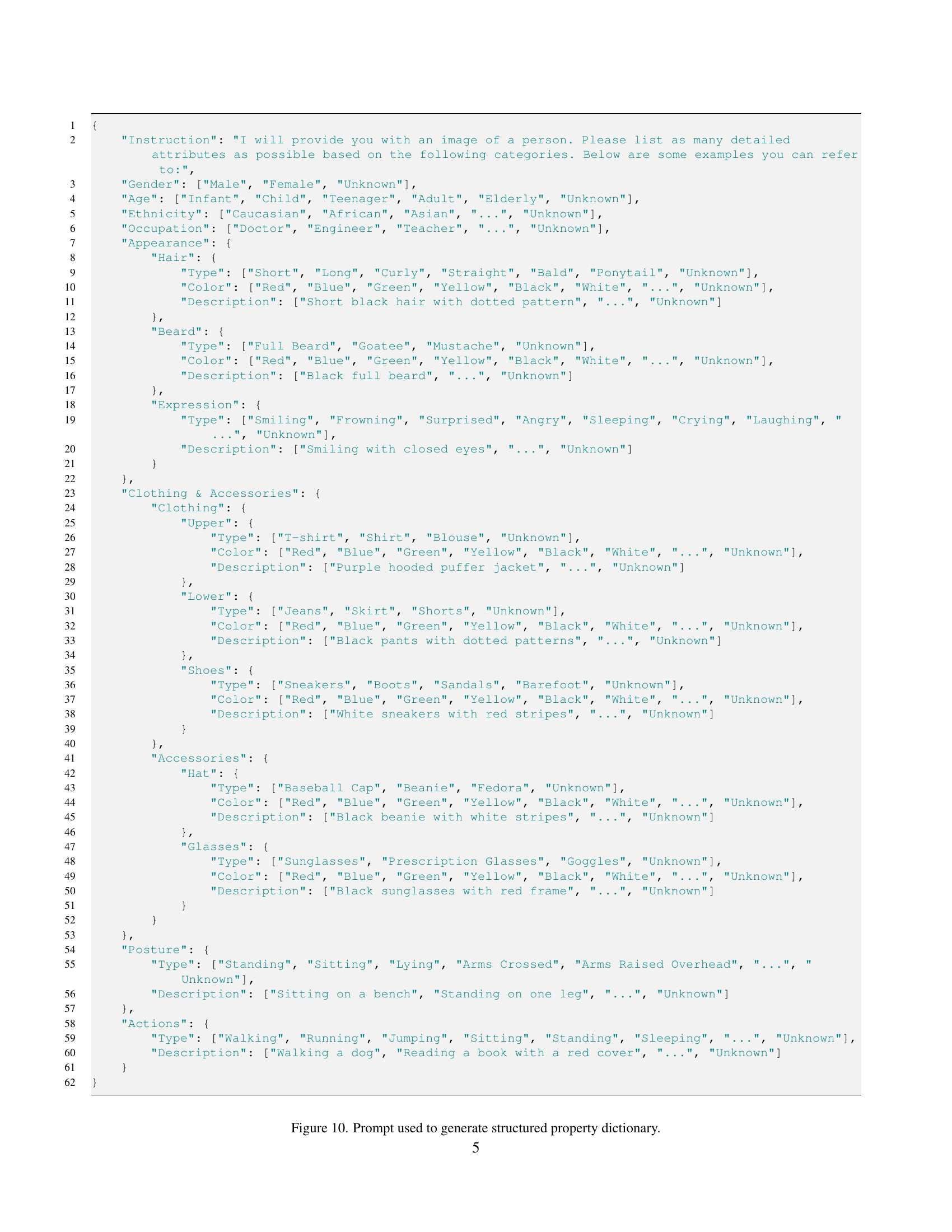

| domain | sub-domains | examples | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| attribute |

|

| ||||||

| position |

|

| ||||||

| interaction |

|

| ||||||

| reasoning |

|

| ||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| rejection | attribute, position, interaction, reasoning | a man in red hat, three women in a circle |

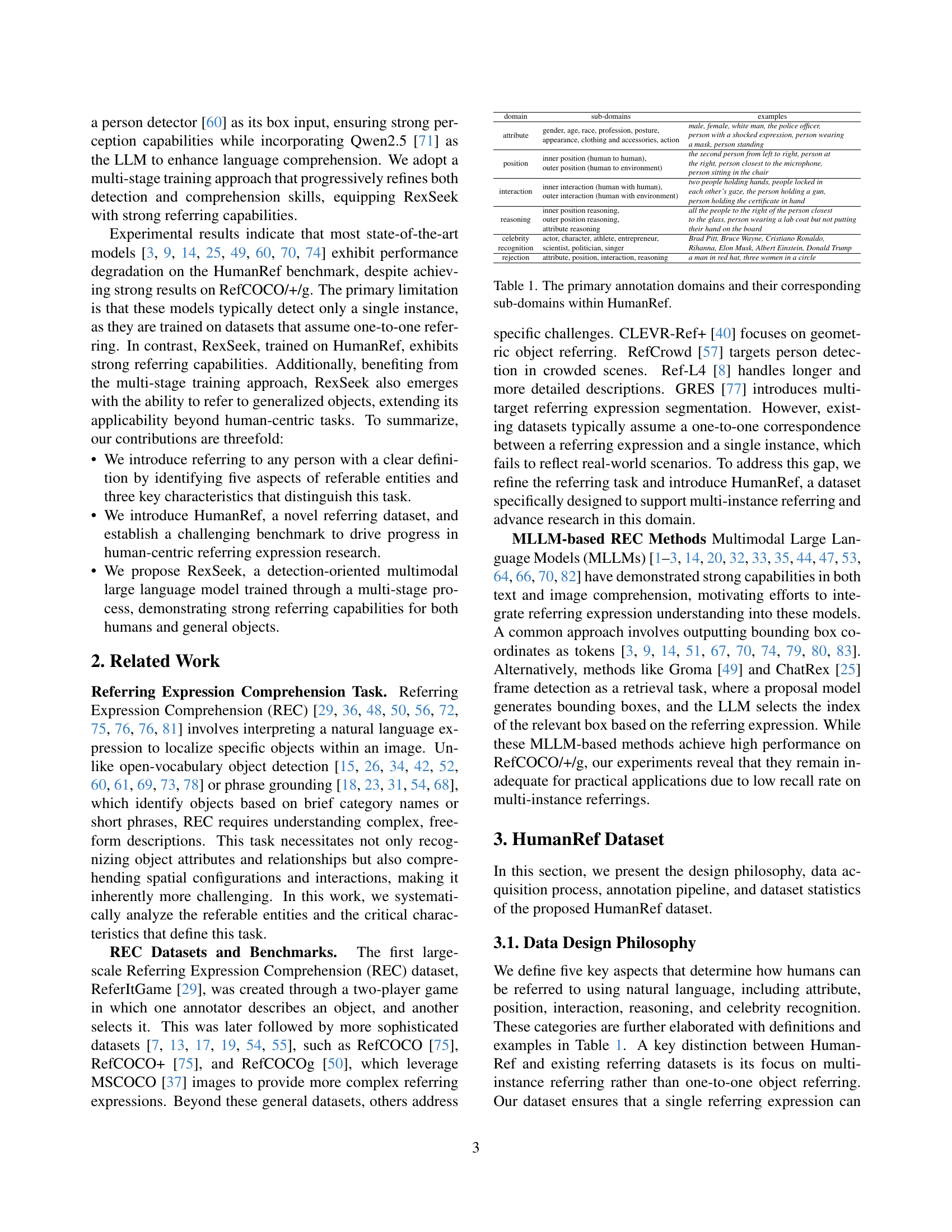

🔼 Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of the annotation domains and sub-domains used in the HumanRef dataset. It shows how different aspects of human appearance, spatial relations, actions, and identities are categorized and annotated for more comprehensive understanding. These annotations are fundamental to the task of referring to any person, ensuring that the dataset accurately reflects the complexity of real-world scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: The primary annotation domains and their corresponding sub-domains within HumanRef.

In-depth insights#

Refer Any Person#

Referring to Any Person is a pivotal task in computer vision, demanding the ability to identify and detect individuals based on natural language descriptions. This capability holds substantial practical value across diverse applications, including human-robot interaction and healthcare. This area of research aims to overcome the limitations of existing models that often struggle with real-world usability due to unclear task definitions and a lack of high-quality data. The task involves capturing a number of aspects in which humans can be referred to. This includes attributes, position, interaction, reasoning, and celebrity recognition. Developing robust models for referring to any person requires addressing challenges such as multi-instance referring, multi-instance discrimination, and rejection of non-existence. The focus on real-world scenarios necessitates models that can accurately identify multiple individuals and avoid hallucinating results when the referred person is not present in the image.

HumanRef Dataset#

The HumanRef dataset is introduced to address the limitations of existing datasets in real-world human referring scenarios, particularly the multi-instance referring where a single expression relates to multiple individuals. A key design choice is including diverse human contexts such as natural settings, industrial scenes, healthcare, and sports. Five key aspects define how humans are referred: attributes, position, interaction, reasoning, and celebrity recognition. Data acquisition involves filtering high-resolution images with at least four individuals to ensure multi-instance discrimination. The dataset’s annotation process includes manual labeling for attributes, position, interaction, and reasoning with automated pipelines for celebrity recognition and rejection. HumanRef aims to better reflect complex, real-world interactions and requires models to possess both robust perception and strong language comprehension.

RexSeek Design#

The RexSeek design emphasizes a robust perception ability and strong language comprehension. It integrates a person detector (DINO-X) for reliable individual detection and a multimodal LLM (Qwen2.5) for accurate interpretation of complex language. RexSeek formulates referring as a retrieval-based process, using vision encoders (CLIP, ConvNext) to extract image features. Rol features and positional embeddings capture object context, combined with text tokens, and fed into the LLM to identify the corresponding bounding box indices. This design enables RexSeek to excel at both human and general object referring, overcoming limitations of existing models.

Multi-Instance#

The concept of multi-instance is crucial for advancing computer vision, especially in tasks like referring expression comprehension. Existing datasets often assume a one-to-one correspondence, limiting their applicability in real-world scenarios where expressions can refer to multiple objects or people. Addressing this requires models to accurately identify and locate all relevant instances, not just a single one. This necessitates a shift in training data and evaluation metrics to accommodate multi-instance scenarios, pushing for more robust and practical vision systems. Failure to account for multi-instance referring leads to models with low recall and limited usability in complex, real-world environments.

Rejection Tests#

Rejection tests are crucial for assessing a model’s ability to abstain from making predictions when an object is absent. A high-performing model should not hallucinate objects. Current models struggle with this, often predicting bounding boxes even when the referred object doesn’t exist. Addressing hallucination necessitates careful dataset design and training strategies. Incorporating negative examples during training can significantly enhance rejection capabilities. Evaluation metrics must accurately quantify the model’s performance in rejection scenarios. In this context, the model must be able to identify if the person is not present and avoid hallucinating an output.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 Figure 2 presents a comparison of three state-of-the-art models (Qwen2.5-VL, InternVL-2.5, and DeepSeek-VL2) performance on a human referring task. The models are shown to successfully identify single individuals in images, as evidenced by their good performance on the RefCOCO+/g benchmark. However, when the task requires identifying multiple individuals within a single image based on a natural language description, these same models often fail. This failure is attributed to an insufficient number of bounding boxes produced by the models, indicating a difficulty in detecting all relevant individuals within the image.

read the caption

Figure 2: Visualization results of Qwen2.5-VL [3], InternVL-2.5 [14], and DeepSeek-VL2 [70] on the human referring task. Despite achieving strong results on referring benchmarks RefCOCO/+/g [50, 75], state-of-the-art models struggle when tasked with identifying multiple individuals as they output an insufficient number of bounding boxes.

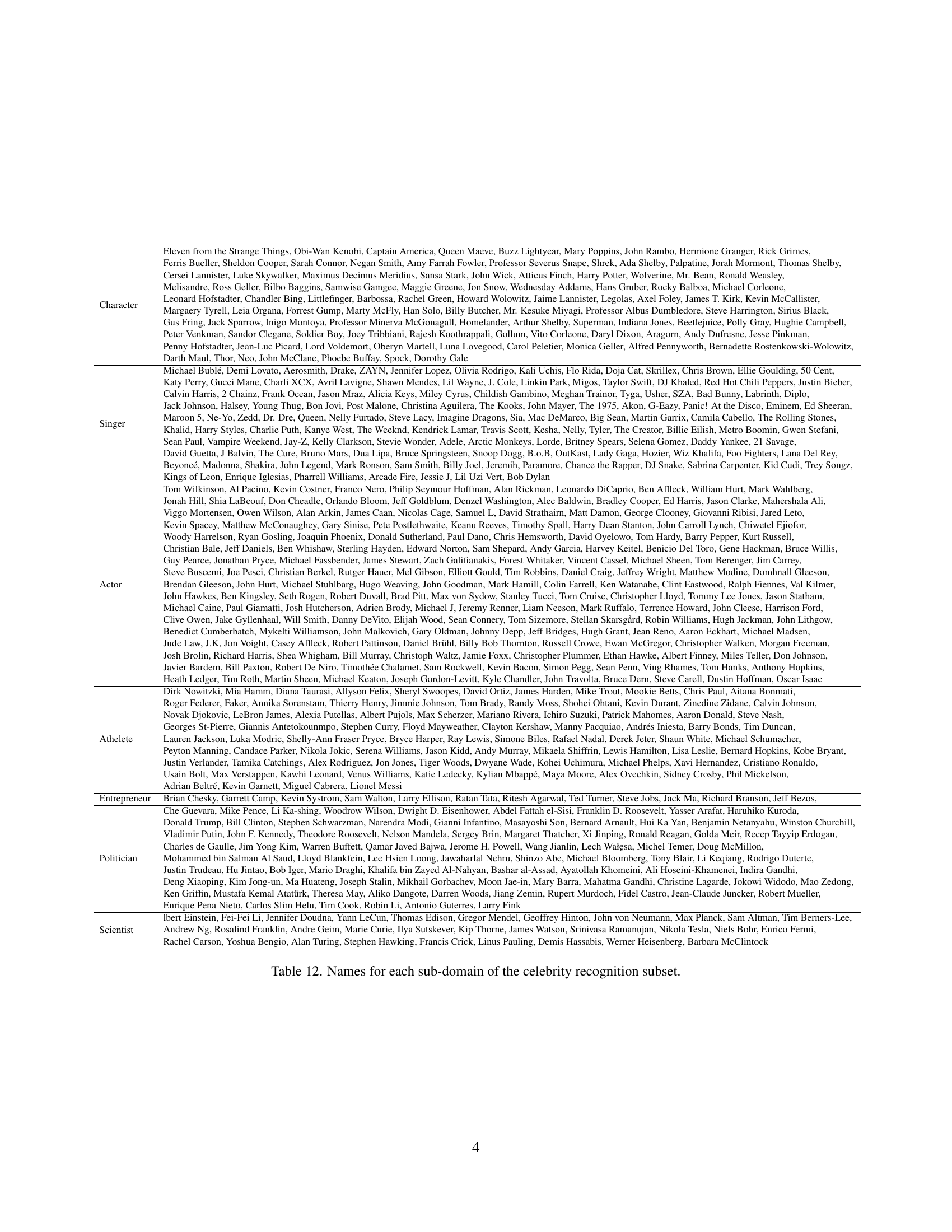

🔼 This figure illustrates the manual annotation process used to create the HumanRef dataset. The process involves three main steps: (1) generating a structured property dictionary using a large language model (LLM) to list potential properties for each individual in an image; (2) assigning these properties to the corresponding individuals; and (3) using the LLM to translate these structured property assignments into natural language referring expressions. The figure visualizes these three steps, showing how properties are extracted, assigned, and converted into the final annotations.

read the caption

Figure 3: Overview of the mannual annotation pipeline of the HumanRef dataset.

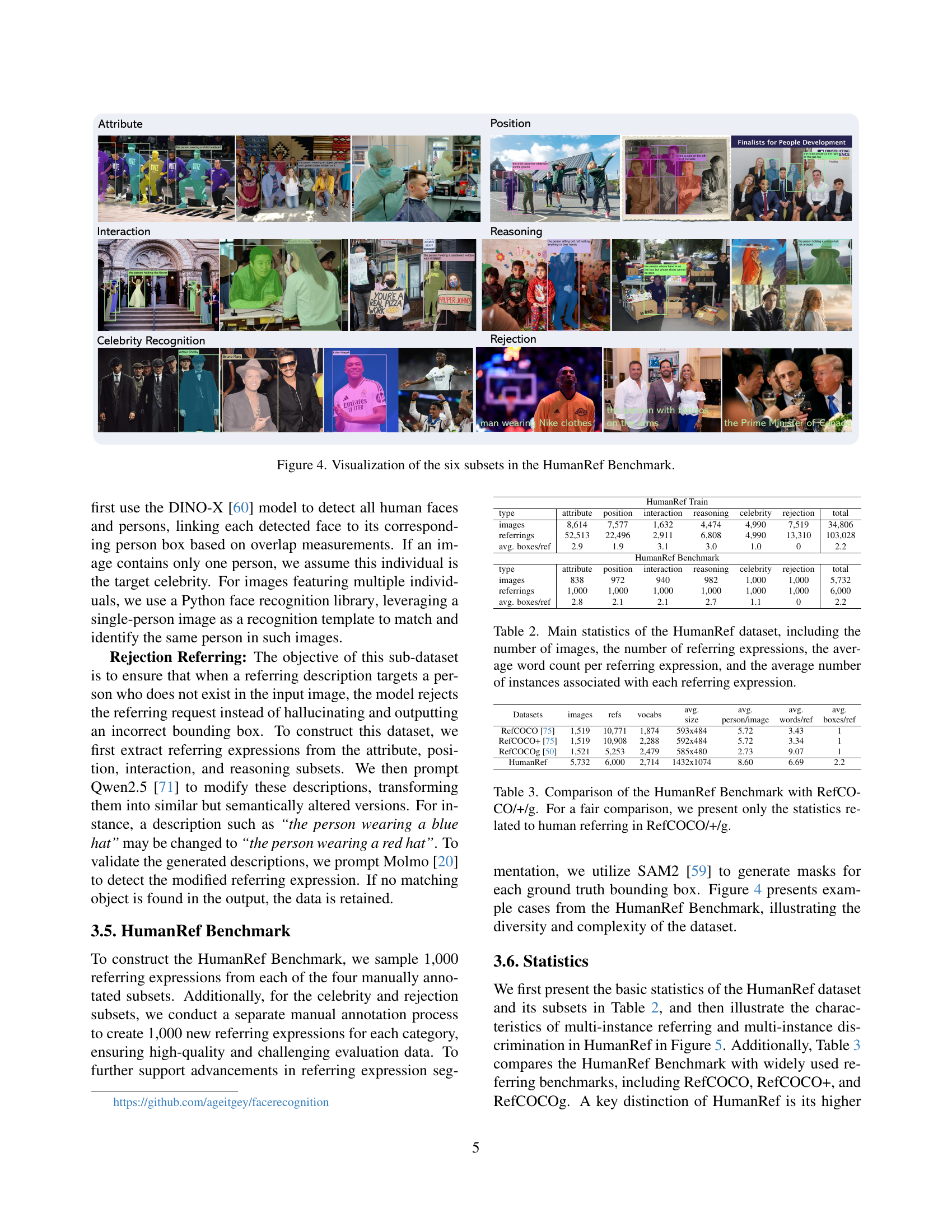

🔼 This figure visualizes the six subsets of the HumanRef benchmark dataset. Each subset focuses on a specific aspect of referring to people in images: attributes (describing characteristics like gender, age, clothing), position (spatial relationships between people and the environment), interaction (actions between people or with objects), reasoning (multi-step inferences to identify individuals), celebrity recognition (identifying famous people), and rejection (handling cases where a referred person isn’t present). Each subfigure shows example images and annotations illustrating the type of data and complexities within each subset.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of the six subsets in the HumanRef Benchmark.

🔼 This figure presents two histograms visualizing the distribution of the number of individuals present in each image of the HumanRef dataset and the number of individuals referenced by each referring expression within the dataset. The first histogram shows how many images contain a certain number of people (e.g., the number of images with 1 person, 2 people, 3 people, and so on). The second histogram depicts the distribution of the number of individuals referenced within each referring expression in the dataset. This provides insights into the dataset’s complexity and challenges regarding the multi-instance nature of the referring task.

read the caption

Figure 5: Distribution of the number of individuals per image and the number of individuals referenced by each referring expression.

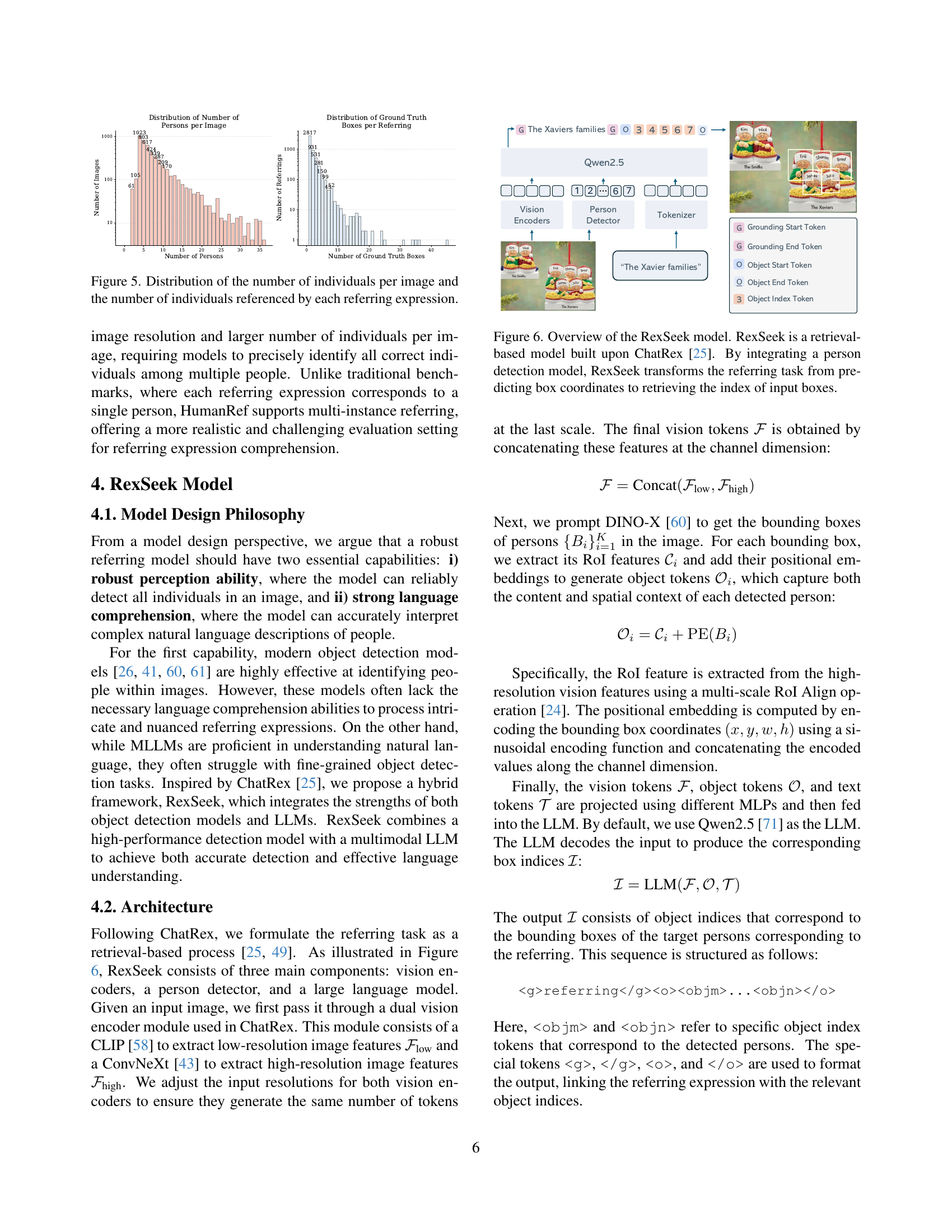

🔼 RexSeek is a retrieval-based model that leverages a person detection model and a large language model (LLM). Instead of directly predicting bounding box coordinates for referring expressions, RexSeek transforms the referring task into a retrieval problem. The model first uses a person detector to identify individuals in an image, generating corresponding object tokens. These tokens, along with vision tokens from the image and text tokens from the referring expression, are input to the LLM. The LLM then outputs a sequence of object indices that directly correspond to the individuals matching the referring expression.

read the caption

Figure 6: Overview of the RexSeek model. RexSeek is a retrieval-based model built upon ChatRex [25]. By integrating a person detection model, RexSeek transforms the referring task from predicting box coordinates to retrieving the index of input boxes.

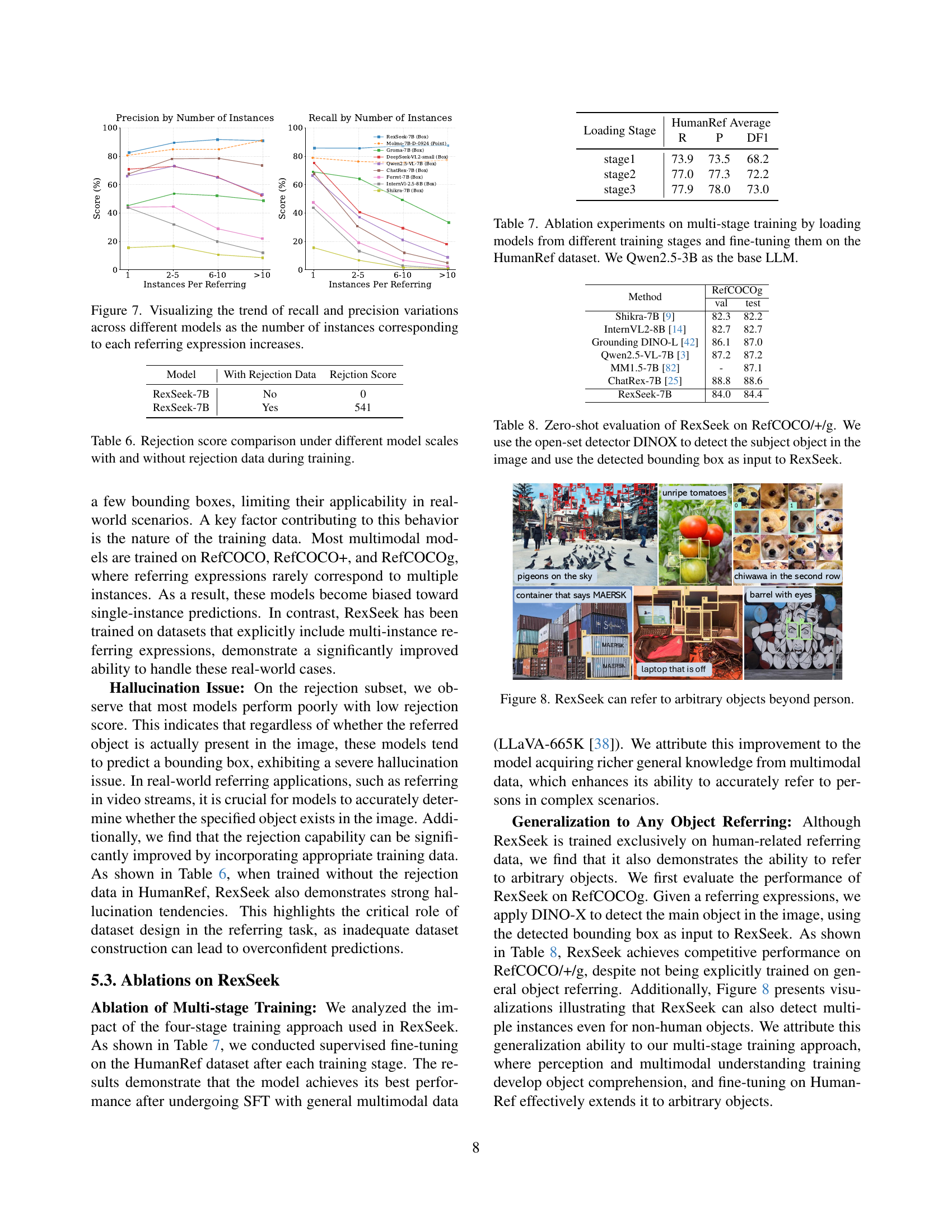

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the performance of various multi-modal models on the HumanRef benchmark, specifically focusing on how their recall and precision change as the number of instances associated with each referring expression increases. The x-axis represents the number of instances (individuals) referenced by a single expression, categorized into ranges (1, 2-5, 6-10, >10). The y-axis displays the recall and precision scores (in percentage). The different lines represent different models, illustrating their performance across this range of complexities.

read the caption

Figure 7: Visualizing the trend of recall and precision variations across different models as the number of instances corresponding to each referring expression increases.

More on tables

| gender, age, race, profession, posture, |

| appearance, clothing and accessories, action |

🔼 Table 2 presents a comprehensive statistical overview of the HumanRef dataset, a crucial component of the research on referring to any person. It details the dataset’s size and composition, providing key metrics for understanding its scale and complexity. These metrics include: the total number of images in the dataset, the total count of referring expressions used to describe individuals within those images, the average length (word count) of each referring expression, and the average number of individuals referenced by a single expression. This information is essential for evaluating the size and scope of the dataset, gauging the complexity of the referring expressions, and comprehending the scale of the multi-instance referring challenges that the dataset addresses.

read the caption

Table 2: Main statistics of the HumanRef dataset, including the number of images, the number of referring expressions, the average word count per referring expression, and the average number of instances associated with each referring expression.

| male, female, white man, the police officer, |

| person with a shocked expression, person wearing |

| a mask, person standing |

🔼 Table 3 compares the HumanRef benchmark dataset with the RefCOCO+/g datasets, focusing solely on statistics related to human references for a fair comparison. It highlights key differences in the number of images, referring expressions, average word count per expression, and average number of persons per image and per referring expression.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of the HumanRef Benchmark with RefCOCO/+/g. For a fair comparison, we present only the statistics related to human referring in RefCOCO/+/g.

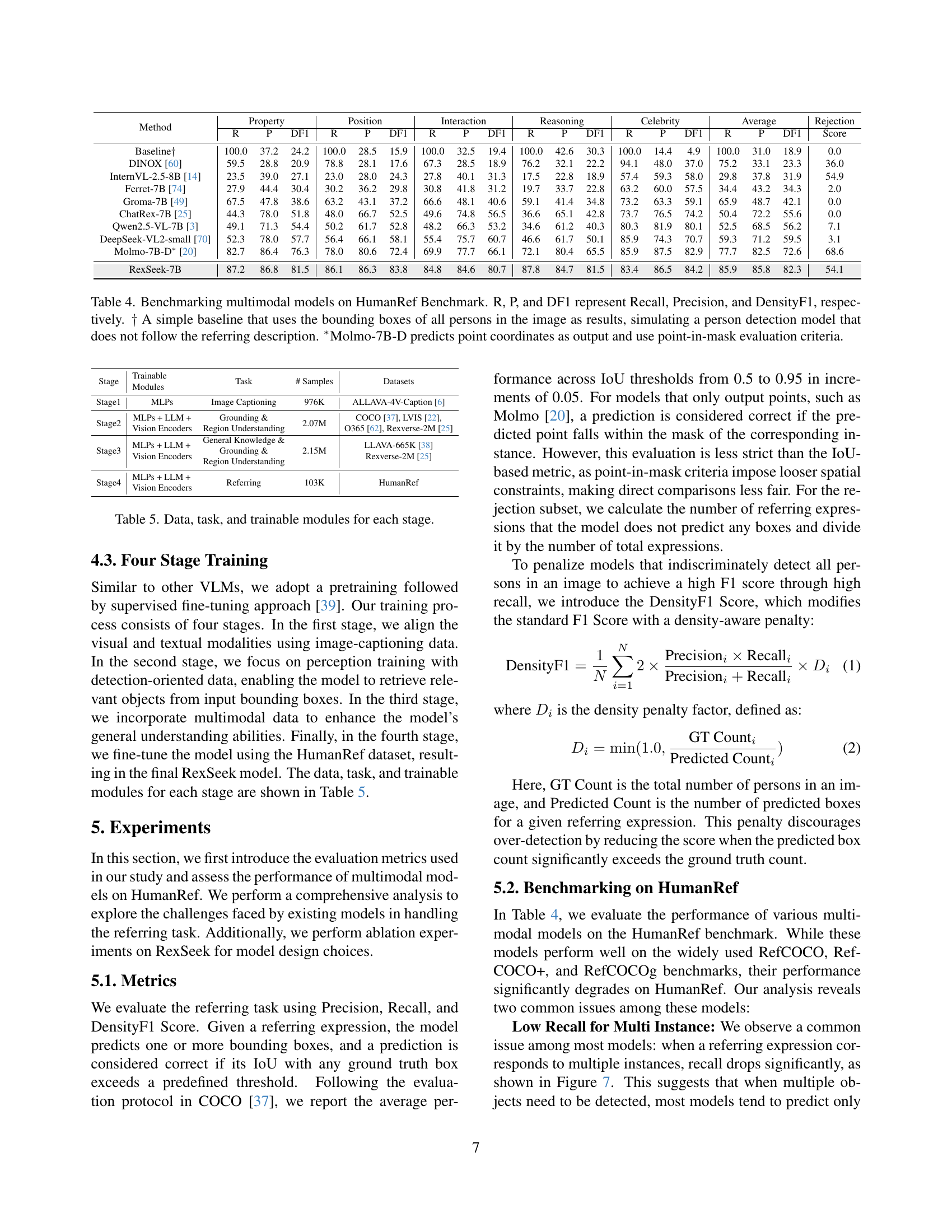

| inner position (human to human), |

| outer position (human to environment) |

🔼 This table presents a benchmark comparison of various multimodal models on the HumanRef dataset, a novel dataset designed for evaluating human referring tasks. The performance of each model is assessed across five sub-tasks: Attribute, Position, Interaction, Reasoning, and Celebrity. The evaluation metrics include Recall (R), Precision (P), Density F1 (DF1), and a rejection score. A simple baseline is included that simulates a person detection model without understanding the language description, simply using all detected person bounding boxes as predictions. Note that one model, Molmo-7B-D, uses a different evaluation metric (point-in-mask), which differs from the IoU-based metric used for other models. This difference in metric is noted in the caption. The results highlight the challenges of existing models in handling the complexities of multi-instance referring and the importance of appropriate dataset design and model training strategies.

read the caption

Table 4: Benchmarking multimodal models on HumanRef Benchmark. R, P, and DF1 represent Recall, Precision, and DensityF1, respectively. ††\dagger† A simple baseline that uses the bounding boxes of all persons in the image as results, simulating a person detection model that does not follow the referring description. ∗Molmo-7B-D predicts point coordinates as output and use point-in-mask evaluation criteria.

| the second person from left to right, person at |

| the right, person closest to the microphone, |

| person sitting in the chair |

🔼 This table details the four-stage training process for the RexSeek model. Each stage uses different datasets, training tasks, and sets of trainable model modules to progressively enhance the model’s capabilities. Stage 1 focuses on aligning visual and textual modalities. Stage 2 concentrates on visual perception tasks. Stage 3 improves the model’s general understanding abilities. Finally, Stage 4 fine-tunes the model on the HumanRef dataset for human referring.

read the caption

Table 5: Data, task, and trainable modules for each stage.

| inner interaction (human with human), |

| outer interaction (human with environment) |

🔼 This table compares the rejection scores achieved by different sized models (indicated by the number after the model name) when trained both with and without rejection data. The rejection score reflects how often the model correctly identifies when the referenced person is not in the image, avoiding the generation of incorrect bounding boxes (hallucination). A higher rejection score indicates better performance in this crucial aspect of the referring task.

read the caption

Table 6: Rejection score comparison under different model scales with and without rejection data during training.

| two people holding hands, people locked in |

| each other’s gaze, the person holding a gun, |

| person holding the certificate in hand |

🔼 This table presents ablation study results on the impact of multi-stage training for the RexSeek model. Different versions of the RexSeek model, each pre-trained to varying degrees of completion (stage1, stage2, stage3), were fine-tuned on the HumanRef dataset. The results, using Recall (R), Precision (P), and DensityF1 (DF1), demonstrate how each pre-training stage affects the final model’s performance on the HumanRef benchmark. The base Large Language Model (LLM) used was Qwen2.5-3B.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation experiments on multi-stage training by loading models from different training stages and fine-tuning them on the HumanRef dataset. We Qwen2.5-3B as the base LLM.

| inner position reasoning, |

| outer position reasoning, |

| attribute reasoning |

🔼 This table presents the results of a zero-shot evaluation of the RexSeek model on the RefCOCO+/g benchmark. Instead of training RexSeek on RefCOCO+/g data, the researchers used a different, pre-trained object detector (DINOX) to locate objects within images. The bounding boxes identified by DINOX were then fed as input to RexSeek, which made its predictions without ever having seen the RefCOCO+/g data during training. This demonstrates RexSeek’s ability to generalize to unseen datasets and tasks.

read the caption

Table 8: Zero-shot evaluation of RexSeek on RefCOCO/+/g. We use the open-set detector DINOX to detect the subject object in the image and use the detected bounding box as input to RexSeek.

| all the people to the right of the person closest |

| to the glass, person wearing a lab coat but not putting |

| their hand on the board |

🔼 This table presents examples illustrating how spatial relationships between individuals are described in the HumanRef dataset. It showcases two categories of positional descriptions: inner position (relative to other people in the image) and outer position (relative to environmental elements). The examples demonstrate the variety and nuance in specifying locations using natural language.

read the caption

Table 9: Examples of Inner and Outer Position References.

| celebrity |

| recognition |

🔼 This table presents examples of how human interactions are categorized in the HumanRef dataset. It shows examples of both ‘inner interactions’ (interactions between people) and ‘outer interactions’ (interactions between people and objects or the environment). Each example provides a natural language description of the interaction. This illustrates the variety of ways human interaction is represented within the dataset, crucial for accurate referring expression comprehension.

read the caption

Table 10: Examples of Inner and Outer Interaction References.

| actor, character, athlete, entrepreneur, |

| scientist, politician, singer |

🔼 This table presents examples of referring expressions that require reasoning to resolve. The expressions demonstrate three types of reasoning: inner position reasoning (relating individuals to each other), outer position reasoning (relating individuals to environment landmarks), and attribute reasoning (combining attributes with negation). Each example highlights the multi-step inference process necessary to identify the correct individual(s).

read the caption

Table 11: Examples of Reasoning-Based Referring Expressions.

| Brad Pitt, Bruce Wayne, Cristiano Ronaldo, |

| Rihanna, Elon Musk, Albert Einstein, Donald Trump |

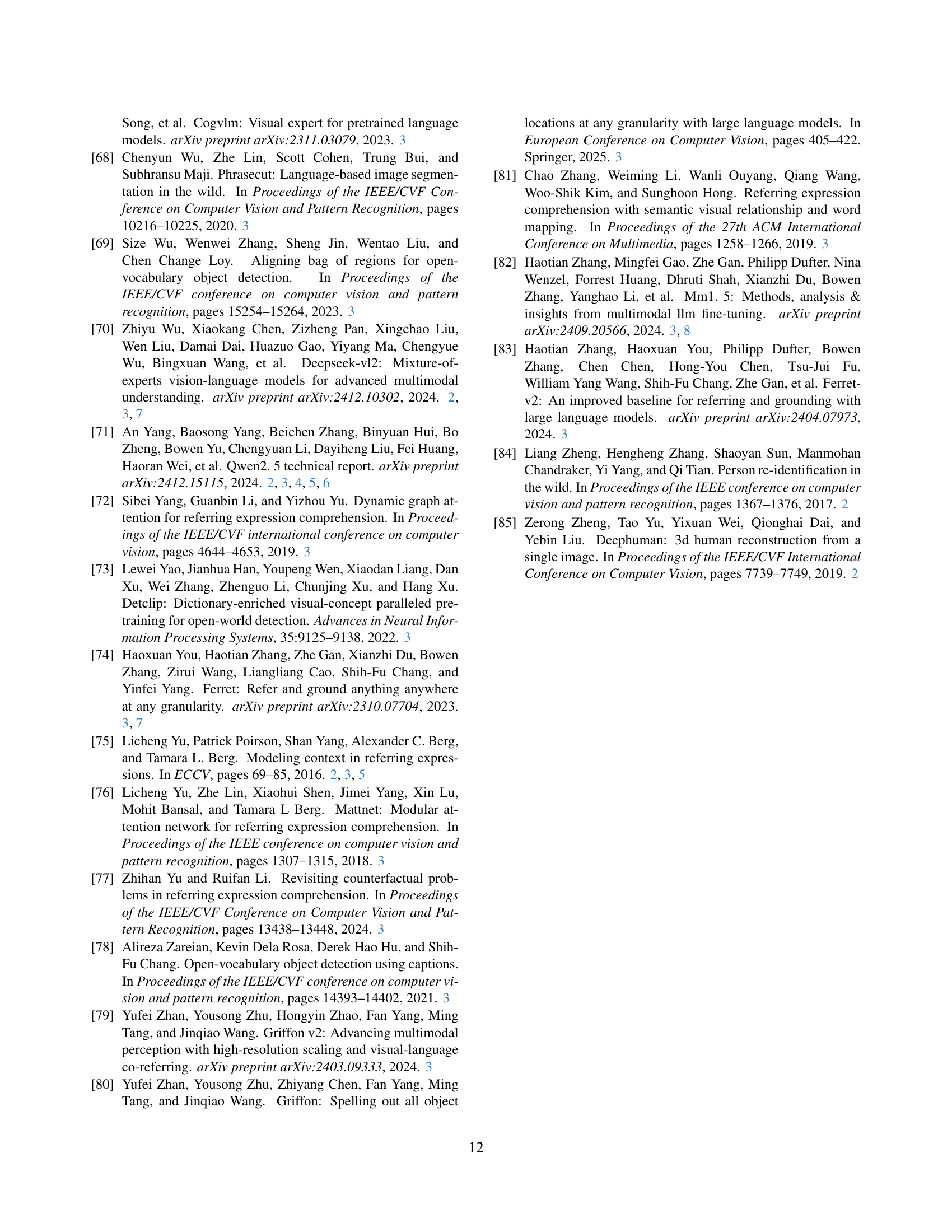

🔼 This table lists the names of celebrities included in the HumanRef dataset’s celebrity recognition subset, categorized into six sub-domains: Character, Singer, Actor, Athlete, Entrepreneur, and Politician. Each sub-domain contains a list of specific individuals representing a variety of well-known people across different fields. This detailed breakdown demonstrates the diversity of celebrity representation within the HumanRef dataset.

read the caption

Table 12: Names for each sub-domain of the celebrity recognition subset.

Full paper#