TL;DR#

Video inpainting, while powerful, often struggles with controllable object insertion and handling long videos. Existing methods primarily focus on scene completion and lack the flexibility to insert new objects with customized trajectories. Text-to-video diffusion models offer promise, but adapting them for inpainting is limited by task unification, input controllability, and long video processing issues.

This paper introduces MTV-Inpaint, a multi-task video inpainting framework built on a T2V diffusion model. It unifies object insertion and scene completion using a dual-branch spatial attention mechanism in the U-Net. It enhances control through an I2V mode, integrating image inpainting tools, and addresses long videos with a two-stage pipeline: keyframe inpainting followed by in-between frame propagation, ensuring temporal consistency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This work introduces a versatile video inpainting framework, MTV-Inpaint, offering multimodal control and addressing long video challenges. It advances video editing capabilities, streamlines complex tasks, and opens avenues for future research in video generation and manipulation.

Visual Insights#

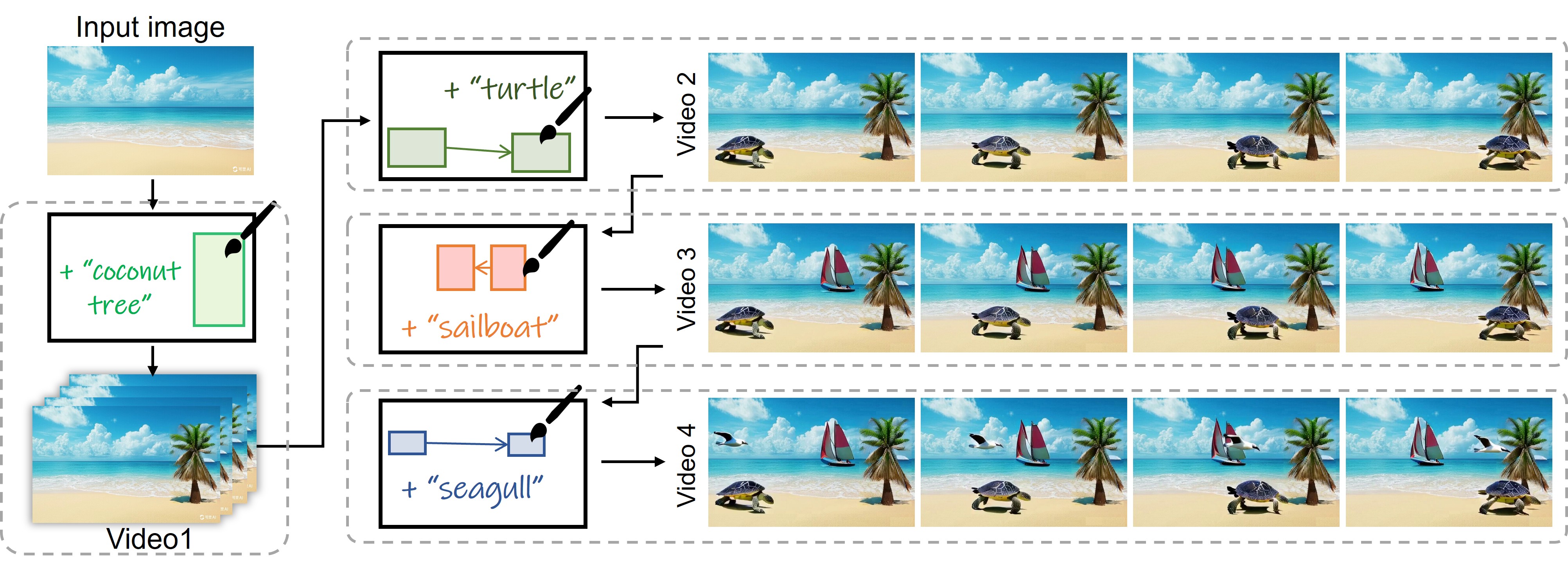

🔼 Figure 1 showcases the versatility of MTV-Inpaint, a novel video inpainting framework. It demonstrates the framework’s ability to perform multiple tasks, including text-guided and image-guided object insertion (adding new objects into a video), scene completion (filling in missing parts of a video), object editing (modifying existing objects), and object removal (removing unwanted objects). The figure visually presents examples of each task, highlighting MTV-Inpaint’s capacity to seamlessly handle these diverse operations within a single unified framework. Furthermore, it illustrates the framework’s capability to process and inpaint long videos composed of hundreds of frames, overcoming a limitation present in many existing video inpainting methods.

read the caption

Figure 1. MTV-Inpaint is a unified video inpainting framework that supports multiple tasks, such as text/image-guided object insertion, scene completion, and derived applications like object editing and removal. It is also capable of handling long videos with hundreds of frames.

| CLIP-T | TempCons | mIOU(%) | ImageReward | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeroscope-blend | 27.35 | 93.03 | 41.14 | -0.290 |

| Animate-Inpaint | 28.01 | 93.15 | 78.82 | -0.099 |

| CoCoCo | 28.53 | 93.16 | 57.63 | 0.026 |

| MTV-Inpaint (Ours) | 28.78 | 94.82 | 85.00 | 0.106 |

🔼 Table 1 presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object insertion in videos. It shows the performance of various approaches across four key metrics: CLIP-T (evaluating the alignment between the generated object and the textual description), TempCons (measuring the temporal consistency of the generated object across video frames), mIOU (assessing the spatial accuracy of object insertion by comparing the generated object’s bounding box to the ground truth mask), and ImageReward (evaluating the overall visual quality of the generated video). This allows for a comprehensive comparison of the effectiveness of each method in generating high-quality, temporally consistent, and accurately placed objects within videos.

read the caption

Table 1. Quantitative comparison for object insertion evaluation.

In-depth insights#

Multi-Task U-Net#

While the term isn’t explicitly used as a heading in the provided text, the concept of a Multi-Task U-Net is central to the described MTV-Inpaint framework. The architecture seems to leverage a U-Net backbone, a common choice for generative tasks. The ‘multi-task’ aspect likely refers to the U-Net’s ability to handle both scene completion and object insertion simultaneously. This is achieved through a dual-branch spatial attention mechanism, allowing the network to process different types of inpainting tasks. One branch specializes in object insertion and the other in scene completion, but both branches share a temporal block. This sharing promotes temporal consistency across frames, a critical requirement for video inpainting. This design enables a unified model, rather than separate architectures for different tasks, leading to a more efficient and flexible system. Moreover, the network is trained with multiple masking modes, including T2V, I2V, and K2V, further enhancing its versatility.

K2V Noise Init#

The K2V Noise Init section introduces a technique to improve temporal consistency in video inpainting. It addresses the discrepancy between diffusion model training and inference, where training involves denoising slightly corrupted data while inference starts from pure noise. This can lead to abrupt transitions. The approach leverages information from neighboring keyframes to initialize the noise, guiding the generation process. By interpolating features from adjacent keyframes, a more informed starting point is established, thus promoting greater temporal smoothness. It uses linear interpolation and Fourier transforms to synthesize noise, ensuring a harmonious blend of local details with overall coherence. This enhances the visual quality of the generated frames and also reduces artifacts that arise from abrupt temporal shifts, making the video more visually appealing and realistic.

Dual Spatial Branch#

The dual spatial branch seems to be an architectural design aimed at handling two distinct but related tasks simultaneously. It likely involves splitting the processing pathway into two separate branches early in the network, each specializing in a specific aspect of the input data or a particular task requirement. This could be beneficial when dealing with data that has inherent dualities or when trying to achieve different objectives concurrently. By dedicating separate branches, the network can learn more specialized features and potentially improve overall performance compared to a single, unified architecture. This approach allows for task-specific optimization within each branch, while possibly sharing information or features at later stages to maintain coherence or achieve synergy.

I2V Controllability#

I2V (Image-to-Video) controllability in video inpainting refers to the degree of control a user has over the inpainting process when using an image as a reference. This is important, as relying solely on text prompts may not provide sufficient control for achieving the desired result. Effective I2V controllability enables users to guide the inpainting process with visual cues, specifying the appearance, style, or content of the inpainted regions. One approach is to integrate existing powerful image inpainting tools, allowing users to leverage their diverse capabilities for video inpainting. This can be achieved by using an image inpainting model to inpaint the first frame of the video, and then propagating the changes to the subsequent frames. Controllable conditions could be incorporated to define the initial pose, vision-language models could be employed to filter suitable first-frame candidates from a batch of generated results, addressing unrealistic motion from third-party image inpainting models.

Motion Conflict#

While ‘Motion Conflict’ isn’t explicitly a titled section, the paper implicitly addresses it as a challenge in video inpainting. The core issue arises when the desired object motion, dictated by a user’s mask trajectory, clashes with the underlying video scene’s inherent motion or lack thereof. This discordance can lead to visual artifacts, unrealistic object placement, or a jarring viewing experience. The paper’s limitations section touches upon this, highlighting that attempting to insert a static object using a moving mask will create artificial motion. It is crucial for the in-painting algorithm to balance the imposed motion with contextual information, or the user may introduce visual artifacts. Future work could explore methods to automatically detect and resolve such conflicts, potentially by incorporating scene understanding or employing more sophisticated motion blending techniques. A key focus would be on ensuring the inserted objects interact believably with the surrounding environment, including aspects such as shadows and reflections. Moreover, the quality of the output relies heavily on the capacity of the diffusion based base T2V model and the accuracy of the object tracking.

More visual insights#

More on figures

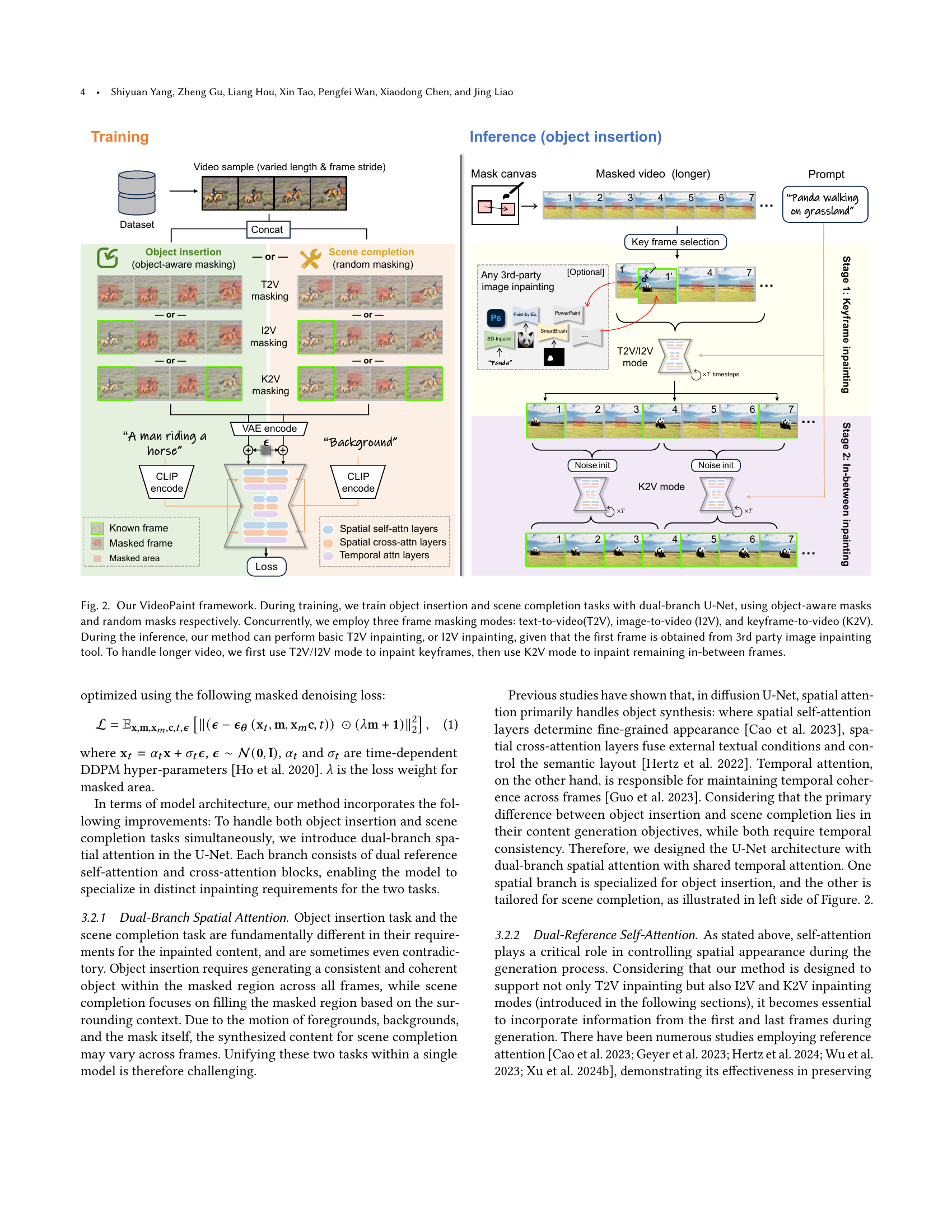

🔼 This figure illustrates the MTV-Inpaint framework’s training and inference stages. During training, a dual-branch U-Net architecture is used to simultaneously handle object insertion (using object-aware masks) and scene completion (using random masks). Three different frame masking modes (T2V, I2V, and K2V) are employed concurrently for comprehensive training. The inference stage allows for several operation modes. Basic text-to-video (T2V) inpainting or image-to-video (I2V) inpainting (using a third-party tool for the first frame) are options for shorter videos. For longer videos, a two-stage approach is used: keyframes are first inpainted using T2V or I2V, and then intermediate frames are inpainted using the keyframe-to-video (K2V) method. This ensures smooth temporal consistency across the entire video.

read the caption

Figure 2. Our VideoPaint framework. During training, we train object insertion and scene completion tasks with dual-branch U-Net, using object-aware masks and random masks respectively. Concurrently, we employ three frame masking modes: text-to-video(T2V), image-to-video (I2V), and keyframe-to-video (K2V). During the inference, our method can perform basic T2V inpainting, or I2V inpainting, given that the first frame is obtained from 3rd party image inpainting tool. To handle longer video, we first use T2V/I2V mode to inpaint keyframes, then use K2V mode to inpaint remaining in-between frames.

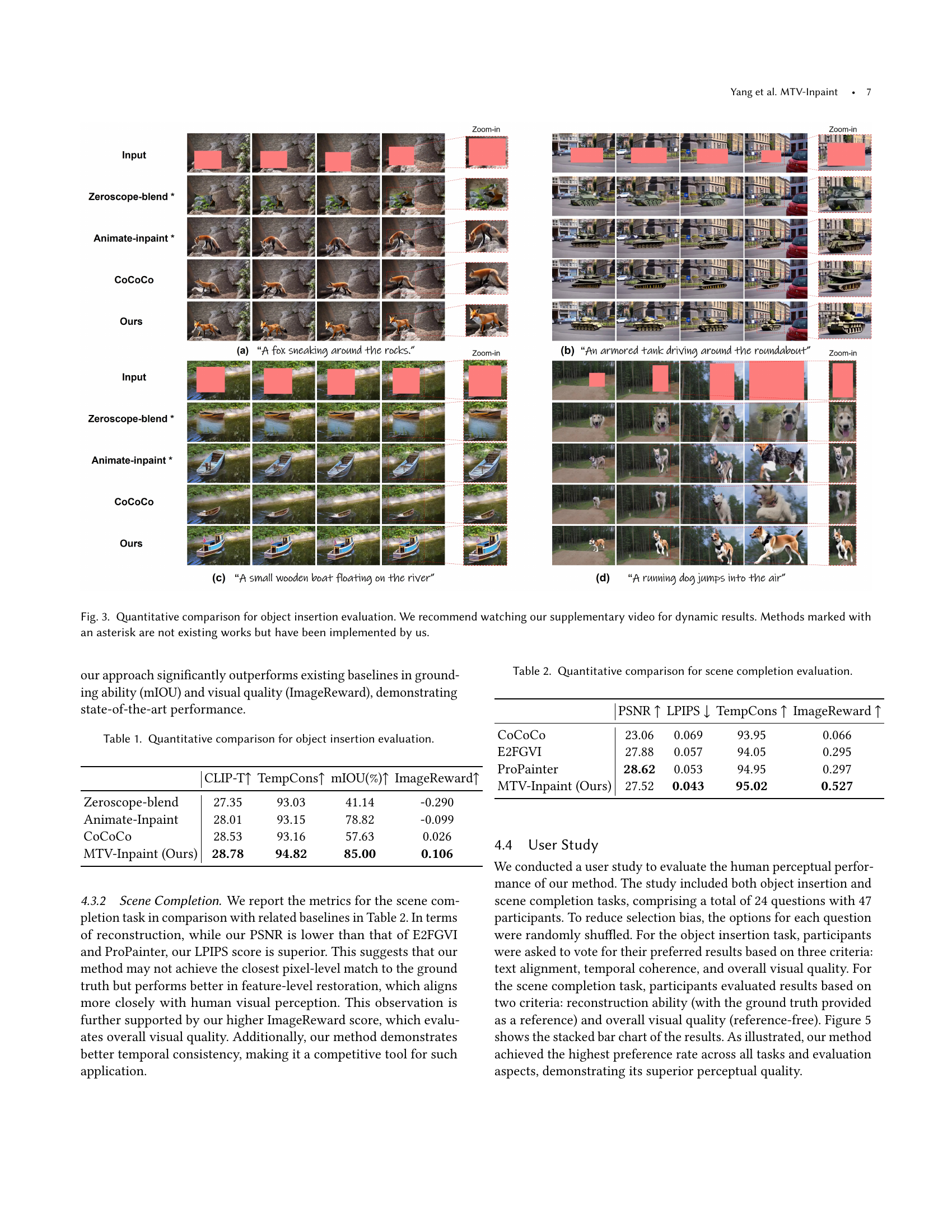

🔼 Figure 3 presents a qualitative comparison of object insertion results from various methods, including the proposed MTV-Inpaint model and several baselines. Each row shows results for a particular video inpainting task. The input videos contain masked regions where objects need to be inserted. The methods are compared based on the quality and realism of the inserted objects. The supplementary video provides a more dynamic view to fully appreciate the differences in performance. The methods marked with an asterisk (*) were not existing published methods, but were implemented by the authors of the paper for comparative purposes.

read the caption

Figure 3. Quantitative comparison for object insertion evaluation. We recommend watching our supplementary video for dynamic results. Methods marked with an asterisk are not existing works but have been implemented by us.

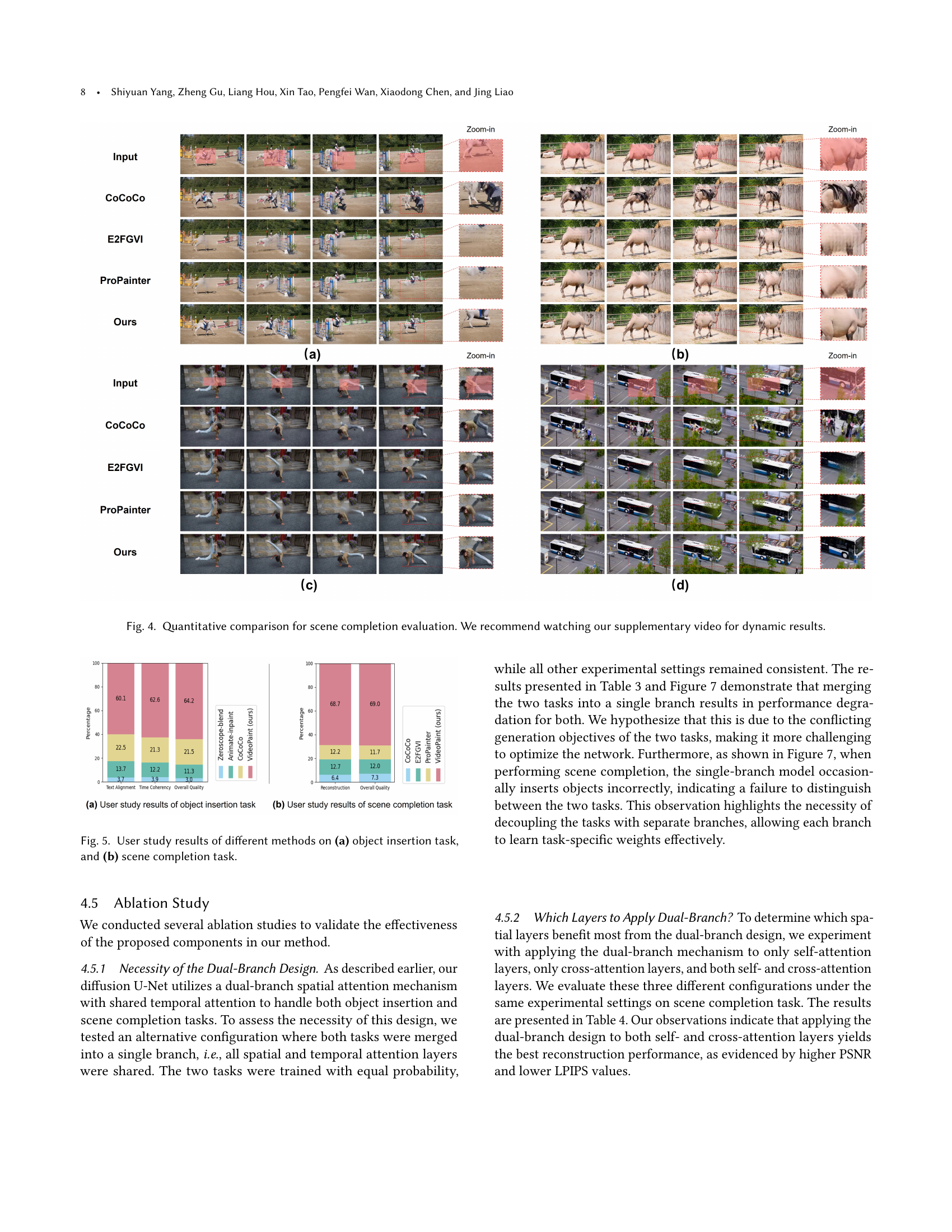

🔼 Figure 4 presents a qualitative comparison of various video inpainting methods on the scene completion task. It showcases several examples of input videos with masked regions alongside the results produced by different methods, including the authors’ MTV-Inpaint model, CoCoCo, E2FGVI, and ProPainter. The figure highlights the differences in visual quality, the ability to handle complex semantic content, and the overall visual fidelity achieved by each method. To fully appreciate the temporal consistency and finer details, it is recommended to view the accompanying supplementary video.

read the caption

Figure 4. Quantitative comparison for scene completion evaluation. We recommend watching our supplementary video for dynamic results.

🔼 This figure presents the results of a user study comparing the performance of different video inpainting methods. Specifically, it shows user preferences for various methods across two tasks: object insertion and scene completion. Each bar chart represents the percentage of users who selected each method as superior based on criteria such as text alignment, temporal coherence, overall visual quality, and reconstruction accuracy. This provides a qualitative measure of each method’s visual appeal and effectiveness in meeting user expectations, supplementing the quantitative results presented elsewhere in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 5. User study results of different methods on (a) object insertion task, and (b) scene completion task.

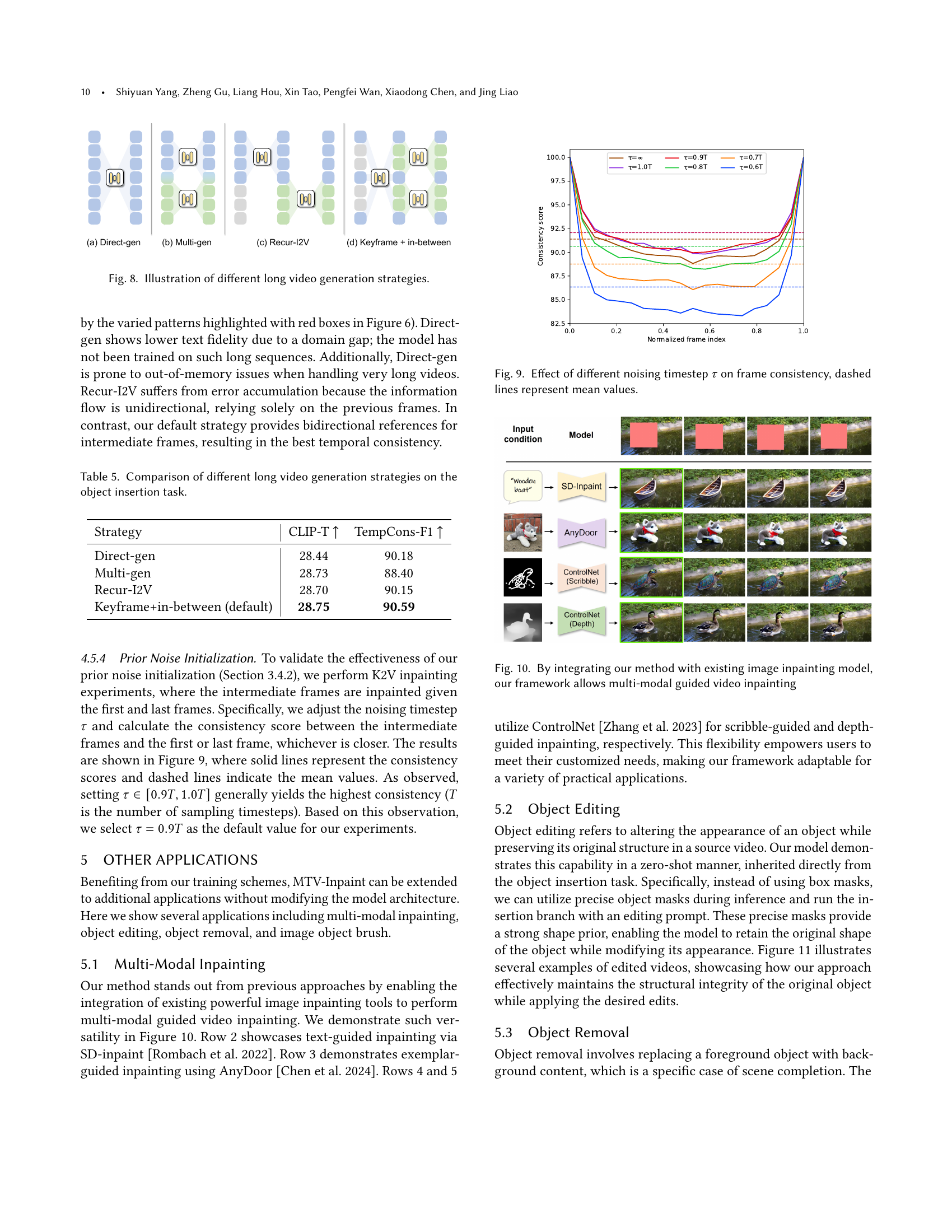

🔼 This figure showcases a comparison of four different strategies used in the paper for long video generation, applied to the task of video inpainting. The strategies include: (1) Directly generating the entire video at once. (2) Generating multiple overlapping sub-clips and averaging the overlapped frames. (3) Recursively inpainting the video clips in an image-to-video mode, relying on the previous clip’s last frame as conditioning. (4) The proposed method, a two-stage approach involving keyframe inpainting followed by intermediate frame inpainting. Each strategy’s results demonstrate how the inpainting quality and temporal coherence vary, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage method for handling longer videos.

read the caption

Figure 6. Visual examples from different long video generation strategies.

🔼 Figure 7 demonstrates the effectiveness of using a dual-branch architecture in the MTV-Inpaint model for video inpainting, specifically focusing on scene completion tasks. The dual-branch design allows the model to distinctly handle scene completion and object insertion tasks, preventing confusion between the two. In contrast, a single-branch architecture struggles with this differentiation, sometimes inappropriately inserting objects into scenes where only scene completion is needed. The figure visually compares the results of both architectural approaches on several scene completion examples, highlighting the errors (circled in red) made by the single-branch model where objects are incorrectly inserted.

read the caption

Figure 7. Comparison of dual-branch and single-branch architectures for scene completion tasks. The dual-branch approach effectively separates scene completion from object insertion task. The single-branch model sometimes fails to distinguish between the two tasks, leading to undesired object insertion during scene completion (circled in red).

🔼 Figure 8 compares four different approaches for generating long videos using the MTV-Inpaint model. These approaches vary in how they handle the temporal aspect of the video generation: 1. Direct-gen: This method directly inpaints all frames of the long video simultaneously. This is the simplest approach but might be computationally expensive and may struggle to maintain temporal coherence across the entire video. 2. Multi-gen: This approach divides the long video into overlapping sub-clips, processing them concurrently, and averaging the overlapping regions for a smoother transition. This method aims to address the computational cost of Direct-gen and improve temporal consistency. 3. Recur-I2V: This iterative approach processes the long video in sequential, non-overlapping segments. Each segment’s inpainting uses the output from the previous segment as a condition, building on prior results. This strategy potentially reduces computational needs and might maintain better consistency compared to Direct-gen but may lead to error accumulation across segments. 4. Keyframe + in-between: This two-stage approach first inpaints keyframes (selected frames throughout the video) independently, then fills in the intermediate frames using information from the adjacent keyframes. It’s designed to improve both efficiency and temporal coherence.

read the caption

Figure 8. Illustration of different long video generation strategies.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of different noise levels (controlled by the noising timestep τ) on the temporal consistency of the video inpainting results. The x-axis represents the normalized frame index within a video sequence, while the y-axis shows the frame consistency score. Multiple lines represent results obtained with various noise levels. The dashed lines indicate the average consistency scores for each noise level. The graph helps to determine the optimal noising timestep that results in the highest temporal consistency during video inpainting.

read the caption

Figure 9. Effect of different noising timestep τ𝜏\tauitalic_τ on frame consistency, dashed lines represent mean values.

🔼 Figure 10 showcases the versatility of MTV-Inpaint by demonstrating its ability to integrate with various existing image inpainting models to achieve multi-modal video inpainting. It displays examples of video inpainting guided by text, exemplar images, scribbles, and depth maps, highlighting how different input modalities can be used to control the inpainting process and achieve diverse results. This demonstrates the framework’s flexibility and extensibility.

read the caption

Figure 10. By integrating our method with existing image inpainting model, our framework allows multi-modal guided video inpainting

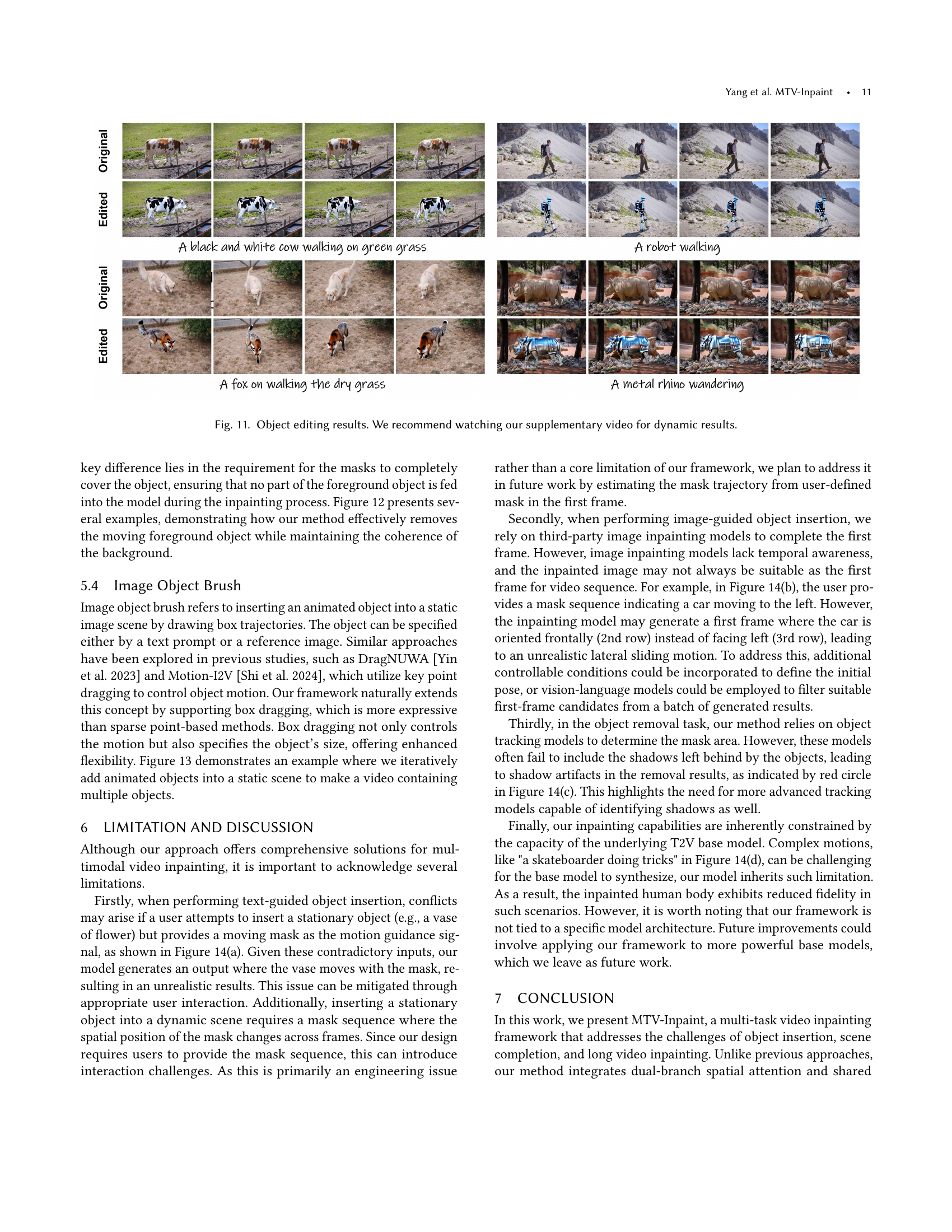

🔼 Figure 11 showcases the results of object editing using the MTV-Inpaint model. The figure presents before-and-after examples of video clips where objects have been modified. The edits appear to seamlessly integrate into the video’s temporal flow, maintaining visual coherence. Specific examples include altering the color of a cow, changing the appearance of a robot, modifying the color of a fox, and modifying the appearance of a rhino. For a more comprehensive understanding of the results, the authors recommend viewing the supplementary video, which likely provides a dynamic demonstration of the changes.

read the caption

Figure 11. Object editing results. We recommend watching our supplementary video for dynamic results.

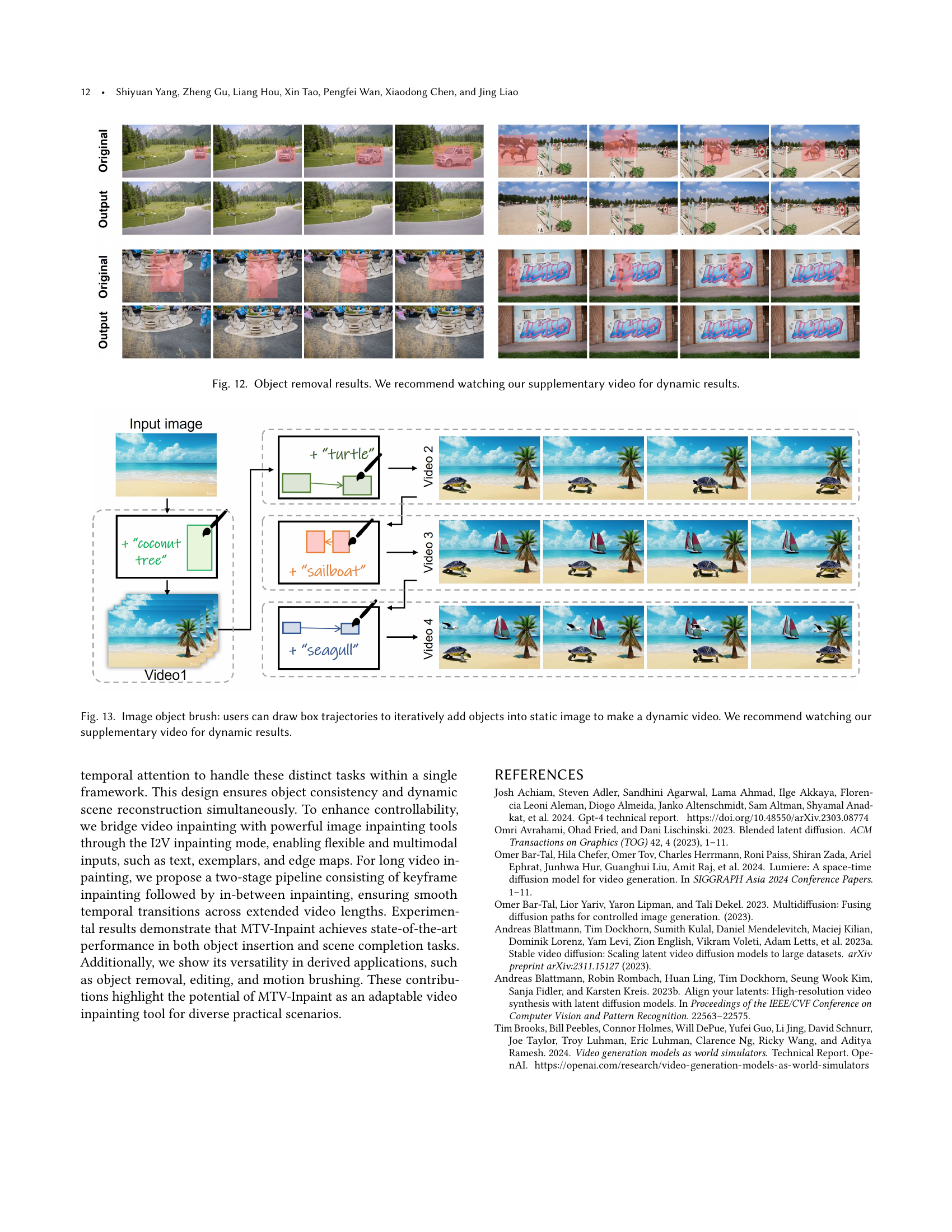

🔼 Figure 12 shows example results of object removal from videos using the MTV-Inpaint model. The input shows the original video with the object to be removed. The output shows the resulting video after object removal, where the removed object’s region has been seamlessly inpainted with contextually appropriate background content. The inpainting aims to maintain temporal consistency and visual coherence in the video. To fully appreciate the results, it is recommended to view the supplementary video provided by the authors, as it will better showcase the seamlessness and fluidity of the inpainted regions across the frames.

read the caption

Figure 12. Object removal results. We recommend watching our supplementary video for dynamic results.

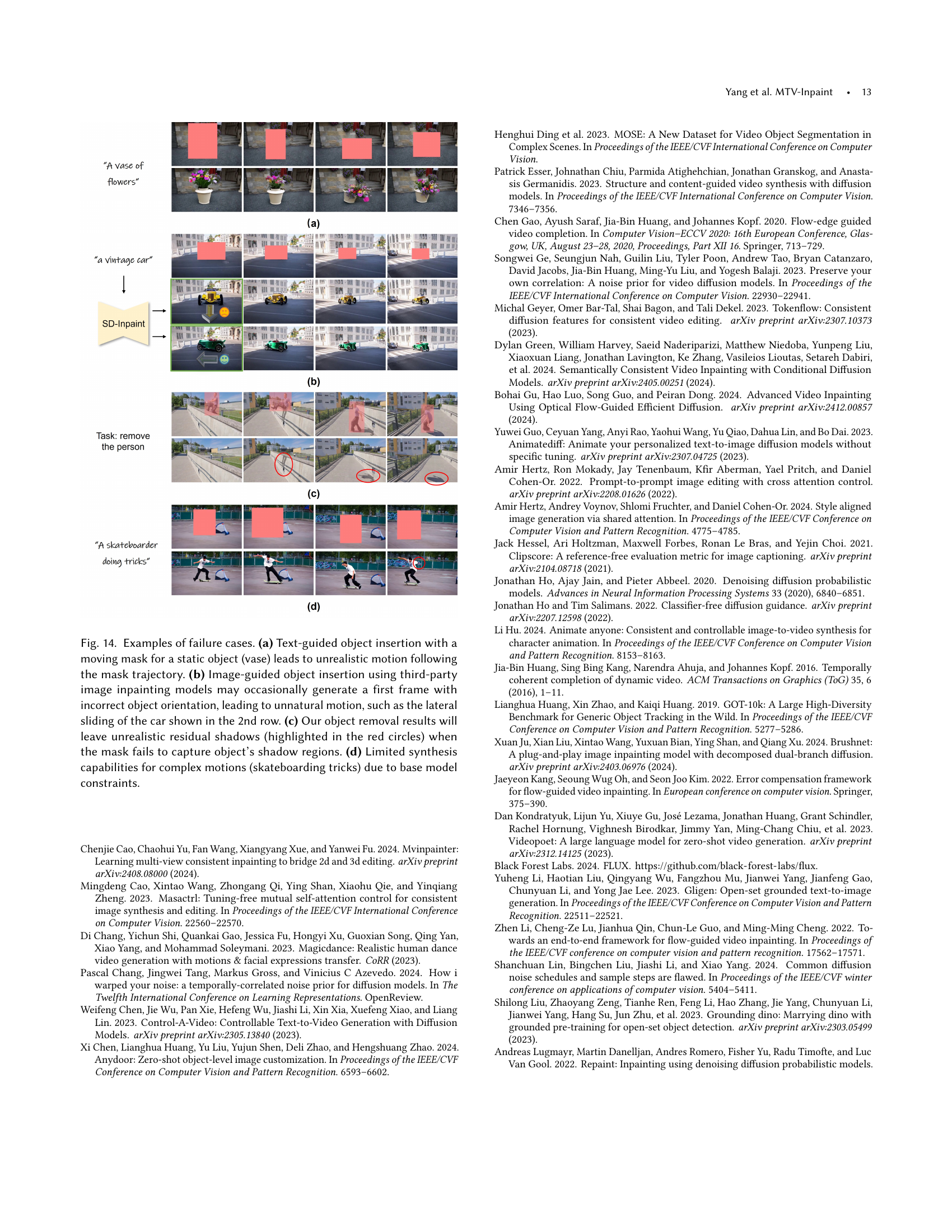

🔼 Figure 13 demonstrates the ‘Image Object Brush’ feature of the MTV-Inpaint model. This feature allows users to interactively add animated objects into a static image to create a dynamic video sequence. The user achieves this by drawing box trajectories on the image, specifying the object’s path and duration. The model then generates a video where the object smoothly moves along the specified trajectory. The objects can be specified either via a text prompt describing the desired object or by providing a reference image. The figure shows an example demonstrating the iterative addition of multiple objects into a single static image to create a final dynamic video. For best viewing, please refer to the supplementary video.

read the caption

Figure 13. Image object brush: users can draw box trajectories to iteratively add objects into static image to make a dynamic video. We recommend watching our supplementary video for dynamic results.

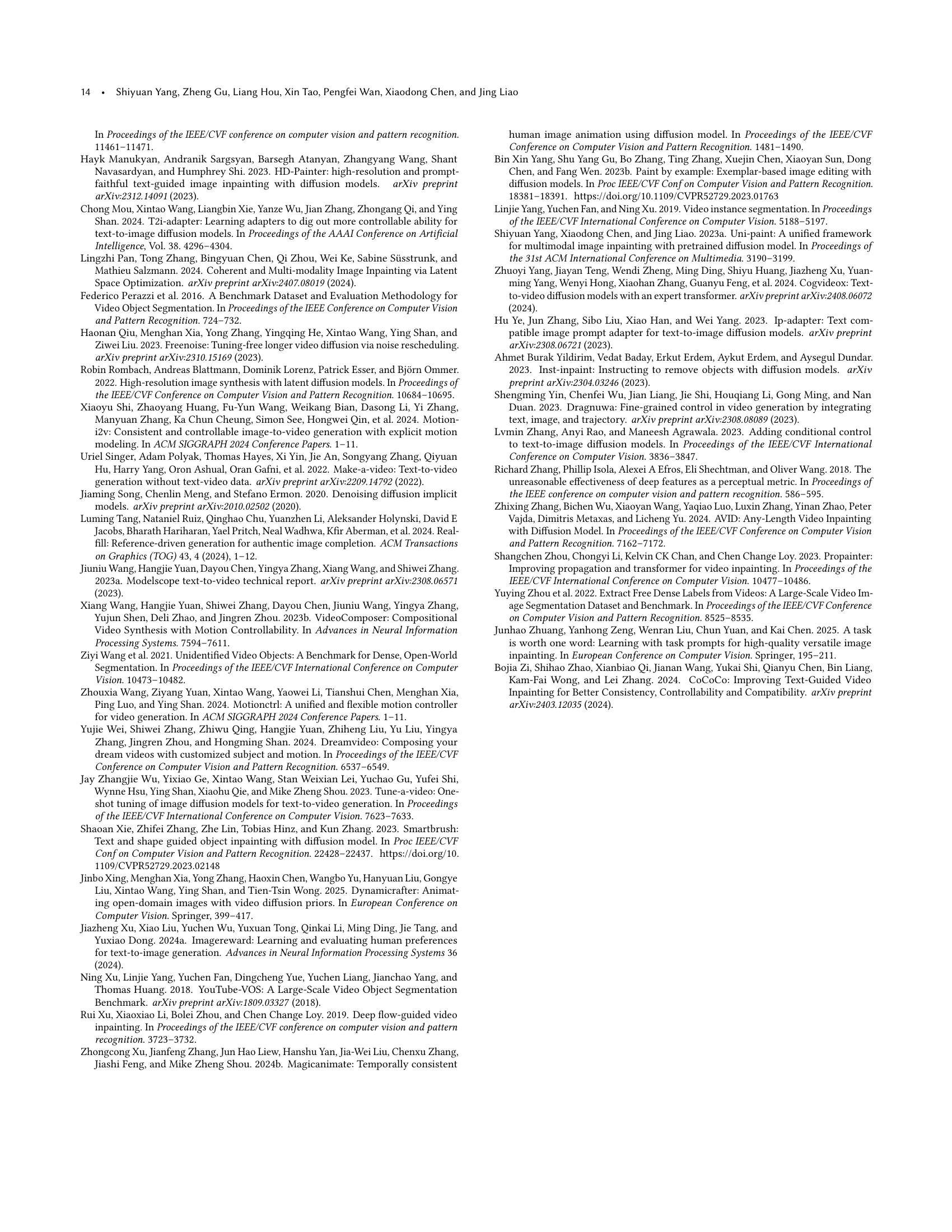

🔼 Figure 14 showcases instances where the MTV-Inpaint model struggles. Panel (a) demonstrates that when a static object (a vase) is requested with a moving mask, the model incorrectly animates the object, following the mask’s movement unrealistically. Panel (b) highlights issues with image-guided insertion; occasionally, the initial frame generated by a third-party inpainting model has an incorrect object orientation, resulting in unnatural movement (as seen with the sideways-sliding car). Panel (c) shows that, during object removal, incomplete masks (failing to encompass the object’s shadow) result in residual shadows. Finally, panel (d) reveals the limitations of the underlying model, illustrating difficulty in synthesizing complex motions like skateboarding tricks.

read the caption

Figure 14. Examples of failure cases. (a) Text-guided object insertion with a moving mask for a static object (vase) leads to unrealistic motion following the mask trajectory. (b) Image-guided object insertion using third-party image inpainting models may occasionally generate a first frame with incorrect object orientation, leading to unnatural motion, such as the lateral sliding of the car shown in the 2nd row. (c) Our object removal results will leave unrealistic residual shadows (highlighted in the red circles) when the mask fails to capture object’s shadow regions. (d) Limited synthesis capabilities for complex motions (skateboarding tricks) due to base model constraints.

More on tables

| PSNR | LPIPS | TempCons | ImageReward | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoCoCo | 23.06 | 0.069 | 93.95 | 0.066 |

| E2FGVI | 27.88 | 0.057 | 94.05 | 0.295 |

| ProPainter | 28.62 | 0.053 | 94.95 | 0.297 |

| MTV-Inpaint (Ours) | 27.52 | 0.043 | 95.02 | 0.527 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different video inpainting methods for the scene completion task. It shows the performance of each method across four metrics: PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), TempCons (Temporal Consistency), and ImageReward (a measure of overall visual quality). Higher PSNR and ImageReward scores indicate better performance, while lower LPIPS scores suggest improved perceptual similarity. TempCons measures the temporal consistency of the generated video.

read the caption

Table 2. Quantitative comparison for scene completion evaluation.

| Object insertion | Scene completion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP-T | TempCons | mIOU (%) | ImageReward | PSNR | LPIPS | TempCons | ImageReward | |

| Single-branch | 26.95 | 93.26 | 81.00 | -0.613 | 26.09 | 0.051 | 93.65 | 0.354 |

| Dual-branch | 28.78 | 94.82 | 85.00 | 0.106 | 27.52 | 0.043 | 95.02 | 0.527 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of single-branch and dual-branch U-Net architectures in object insertion and scene completion tasks. It shows the impact of using separate branches (dual-branch) versus a single branch for handling both tasks. The metrics used for comparison include CLIP-T (measuring the alignment between generated content and text prompt), TempCons (temporal consistency), mIOU (measuring the overlap between predicted and ground truth object masks), and ImageReward (a metric evaluating the visual quality of the generated images). The results demonstrate the superior performance of the dual-branch architecture in achieving higher scores across all metrics, highlighting the benefits of specialized processing for distinct task objectives.

read the caption

Table 3. Comparison between single-branch and dual-branch designs for object insertion and scene completion tasks.

| Self | Cross | PSNR | LPIPS | TCons | ImgReward | Param |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 26.89 | 0.044 | 94.13 | 0.405 | 49.6M (+3.5%) | |

| ✓ | 26.74 | 0.045 | 93.96 | 0.454 | 50.3M (+3.6%) | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 27.44 | 0.043 | 94.14 | 0.424 | 99.9M (+7.1%) |

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of applying the dual-branch design to different attention mechanisms within the model. It compares model performance using three configurations: applying the dual-branch design to self-attention only, cross-attention only, and both self-attention and cross-attention. The results, measured in PSNR, LPIPS, Temporal Consistency (TCons), and ImageReward, assess the effectiveness of each configuration and provide insights into the contribution of different attention components to the overall performance of the model. The parameter count for each variant is also listed.

read the caption

Table 4. Ablation study on applying the dual-branch design to self-attention, cross-attention, or both.

| Strategy | CLIP-T | TempCons-F1 |

|---|---|---|

| Direct-gen | 28.44 | 90.18 |

| Multi-gen | 28.73 | 88.40 |

| Recur-I2V | 28.70 | 90.15 |

| Keyframe+in-between (default) | 28.75 | 90.59 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of four different strategies for generating long videos in the context of object insertion within a video inpainting task. The strategies are evaluated based on two metrics: CLIP-T (measuring the alignment between generated video content and the text prompt) and TempCons-F1 (measuring the temporal consistency of the generated object within the long video sequence, specifically comparing each frame to the first frame). The results demonstrate the relative performance of each strategy in terms of both visual coherence and temporal consistency across long video segments.

read the caption

Table 5. Comparison of different long video generation strategies on the object insertion task.

Full paper#