TL;DR#

Text and reference-based image editing methods often fall short in complex spatial transformations due to limitations in expressing geometric details or transferring non-rigid poses. To address these limitations, this paper introduces a novel task, Edit Transfer, where the model learns a transformation from a single source-target editing example and applies it to a new query image. This approach aims to mitigate the shortcomings of existing methods by explicitly learning the editing transformation.

The paper proposes a visual relation in-context learning paradigm, inspired by in-context learning in large language models, to capture complex spatial transformations from minimal examples. By arranging the edited example and the query image into a unified four-panel composite and applying lightweight LoRA fine-tuning to a DiT-based text-to-image model, the method effectively transfers both single and compositional non-rigid edits, even with limited training data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper introduces a novel image editing approach, Edit Transfer, that leverages visual in-context learning to enable complex, non-rigid transformations from minimal examples. The research addresses limitations of text and reference-based methods, opening avenues for few-shot visual relation learning in image manipulation.

Visual Insights#

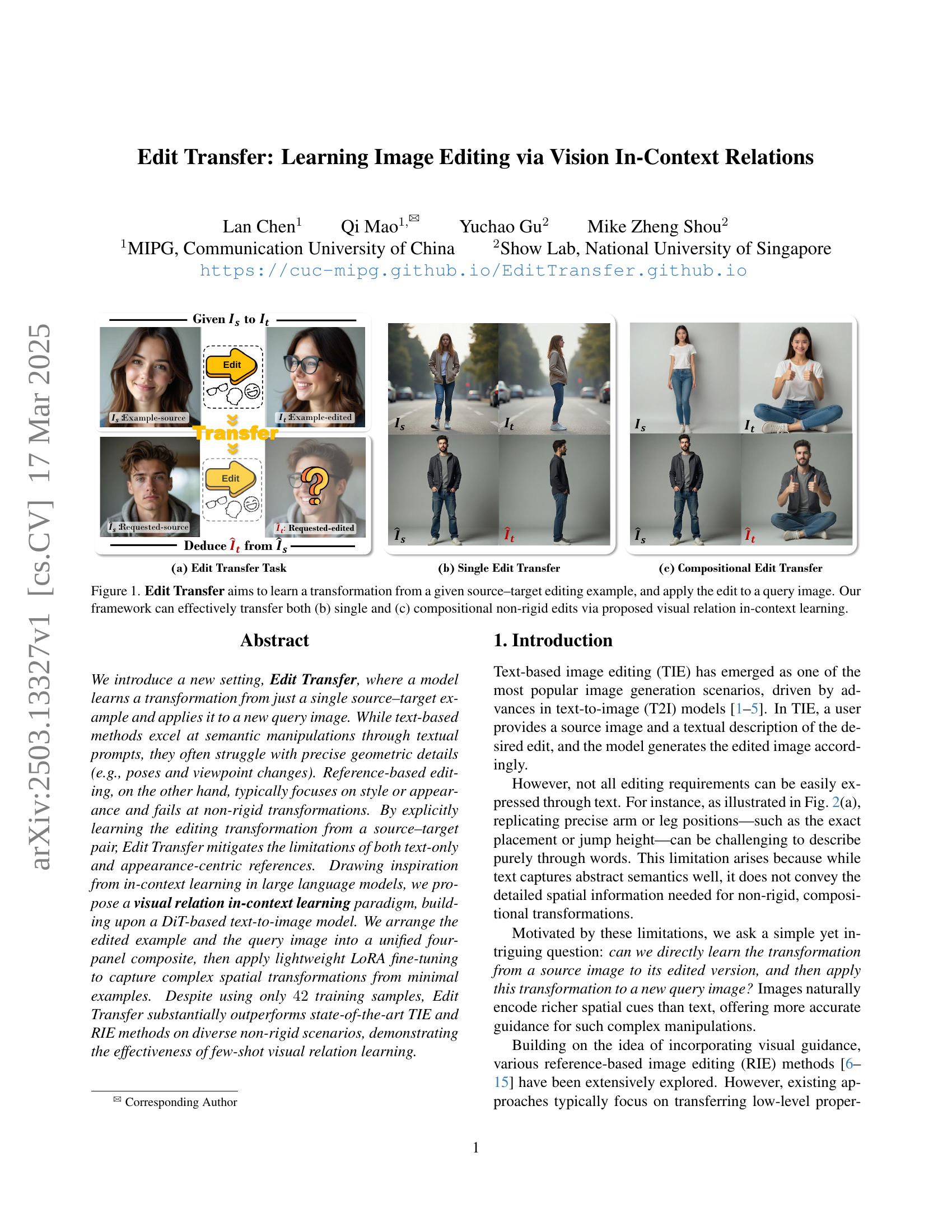

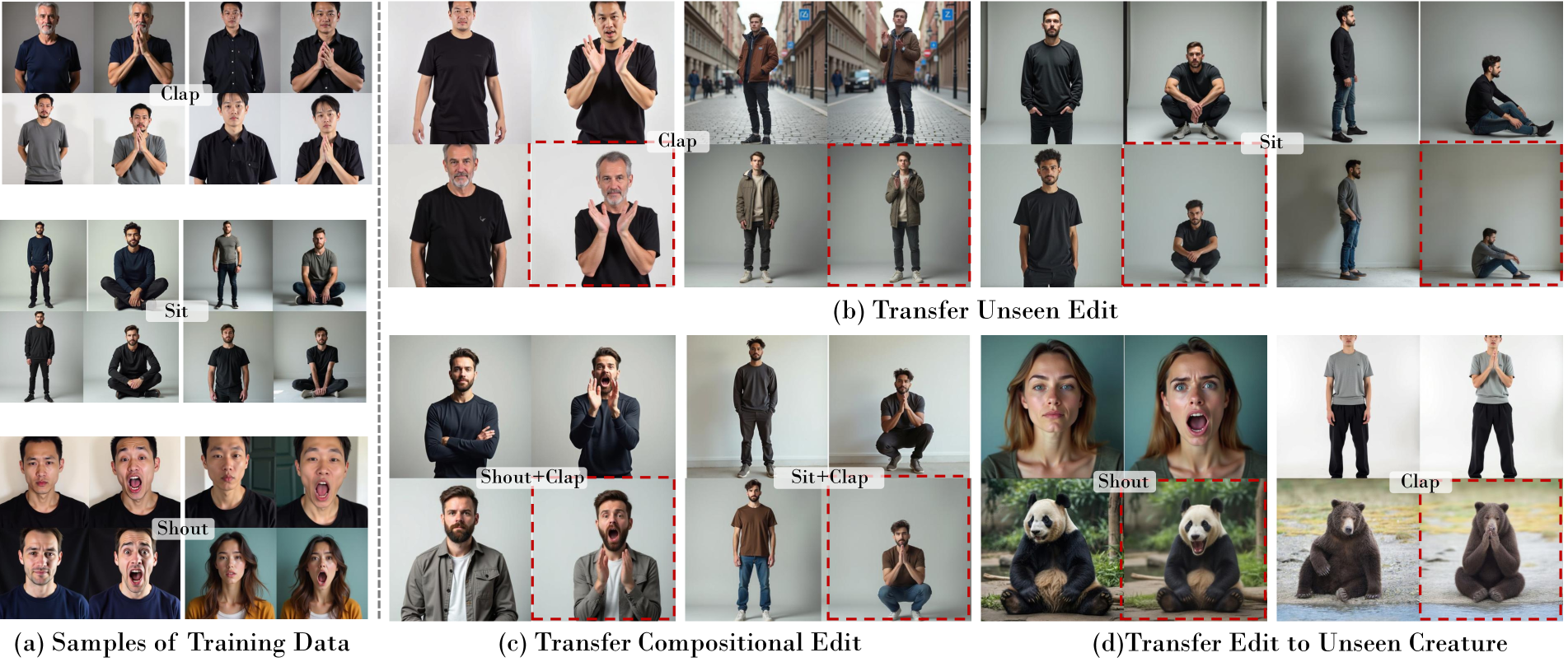

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates the core concept of Edit Transfer. Given a single example of an image and its edited version (source-target pair), the model learns the transformation applied. This learned transformation is then applied to a new, unseen query image to produce a corresponding edit. The figure showcases two main applications: (b) transferring single edits (e.g., changing a person’s pose) and (c) transferring compositional edits (e.g., combining multiple pose changes and other modifications simultaneously). This capability is achieved through the paper’s proposed visual relation in-context learning approach.

read the caption

Figure 1: Edit Transfer aims to learn a transformation from a given source–target editing example, and apply the edit to a query image. Our framework can effectively transfer both (b) single and (c) compositional non-rigid edits via proposed visual relation in-context learning.

| Method | TIE | RIE | Ours | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2P [20] | RF-Solver-Edit [23] | Mimic-Brush [13] | ||

| CLIP-T () | 20.22 | 19.83 | - | 22.58 |

| CLIP-I () | - | - | 0.804 | 0.810 |

| PickScore () | 20.60 | 20.96 | 20.34 | 21.50 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed Edit Transfer method against several baseline methods for image editing. The comparison is done using three different metrics: CLIP-T score, CLIP-I score, and PickScore. CLIP-T assesses the alignment between text and image, CLIP-I measures the similarity between the edited image and a reference image, and PickScore evaluates the overall image quality. Higher scores indicate better performance. The table highlights the superior performance of Edit Transfer across all metrics, demonstrated by boldfaced values indicating the best results for each metric.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative comparisons of baselines and our Edit Transfer. Bold indicates the best value.

In-depth insights#

Edit Transfer#

Edit Transfer as a concept is intriguing, offering a potential bridge between the precision of reference-based image editing and the semantic flexibility of text-based methods. The core idea of learning a transformation from a single source-target example is ambitious, given the complexity of image manipulations. By mitigating the limitations of text-only and appearance-centric references, it is a significant development. A visual relation in-context learning paradigm promises to capture complex spatial transformations, which surpasses current method. The use of lightweight LoRA fine-tuning on a DiT-based model is also a smart approach. The fact that such edits can be transferred is impressive, particularly in non-rigid scenarios.

In-Context Visuals#

Considering the title ‘In-Context Visuals’, the research likely explores how visual information is processed and understood within a specific visual environment or context. This suggests that the meaning of a visual element is not inherent but is derived from its surroundings. The study might investigate how surrounding images, spatial relationships, or even abstract visual cues influence perception, interpretation, and decision-making. Furthermore, the research could delve into how humans and perhaps AI models leverage contextual information to disambiguate ambiguous visuals, infer hidden information, or generate more accurate or relevant responses. It may also focus on visual reasoning where the system needs to learn relationships between objects, their attributes, and the overall scene. The core contribution here could be a novel architecture or a training paradigm that enhances a model’s ability to effectively incorporate visual context, leading to improved performance in tasks such as image editing, visual question answering, or object recognition. The research might emphasize that learning to discern these contextual relationships from limited examples is key to achieving human-like perception and decision-making in complex visual scenarios.

Few-Shot LoRA#

The concept of “Few-Shot LoRA” is intriguing, suggesting an attempt to adapt large pre-trained models with minimal data using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). This approach addresses the challenge of fine-tuning large models which is data-hungry and computationally expensive. By focusing on few-shot learning, the method aims to enable rapid adaptation to new tasks or domains using only a handful of examples. LoRA’s efficiency comes from training low-rank matrices instead of the entire model, significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters and computational resources. A key challenge is maintaining generalization ability with so few examples, necessitating careful design of the training data and potentially employing techniques like meta-learning or regularization to prevent overfitting. The success of Few-Shot LoRA would have significant implications, allowing for personalized or specialized models to be quickly created with limited resources, democratizing access to advanced AI capabilities.

Beyond TIE/RIE#

Going beyond Text-based Image Editing (TIE) and Reference-based Image Editing (RIE) suggests a move towards more nuanced and versatile image manipulation techniques. TIE, while powerful for semantic edits, often struggles with precise geometric control. RIE improves upon TIE by incorporating visual guidance but primarily excels at appearance transfer, falling short in complex spatial transformations. Future research may focus on integrating the strengths of both approaches while addressing their limitations. This could involve developing methods that can simultaneously understand and apply both high-level semantic instructions and fine-grained spatial relationships. Ideally, the next generation of image editing tools should enable users to intuitively manipulate images with a combination of textual cues, visual references, and direct spatial control. Furthermore, exploring entirely new paradigms beyond TIE/RIE, such as learning transformations from example editing pairs, holds promise for unlocking more advanced and intuitive image editing capabilities. The ultimate goal is to create tools that are not only powerful but also accessible, allowing users to achieve complex edits without requiring specialized knowledge or technical expertise.

Spatial Limits#

Thinking about ‘Spatial Limits’ in the context of image editing suggests exploring the boundaries of manipulation. How far can an edit go before it’s no longer recognizable or realistic? We might consider the physical constraints – like anatomical impossibilities or the limits of perspective. Also, ‘Spatial Limits’ could refer to the extent of an edit’s influence. Does a small change cascade into larger, unintended consequences across the image? The concept also brings up the tension between local edits and global consistency. Can one area be dramatically altered without disrupting the overall scene’s coherence? Furthermore, ‘Spatial Limits’ might allude to the amount of geometric transformation (rotation, scaling, translation) an image can endure while preserving its integrity. There’s a threshold beyond which distortions become visually jarring, highlighting the challenge of balancing creative freedom with maintaining realistic spatial relationships.

More visual insights#

More on figures

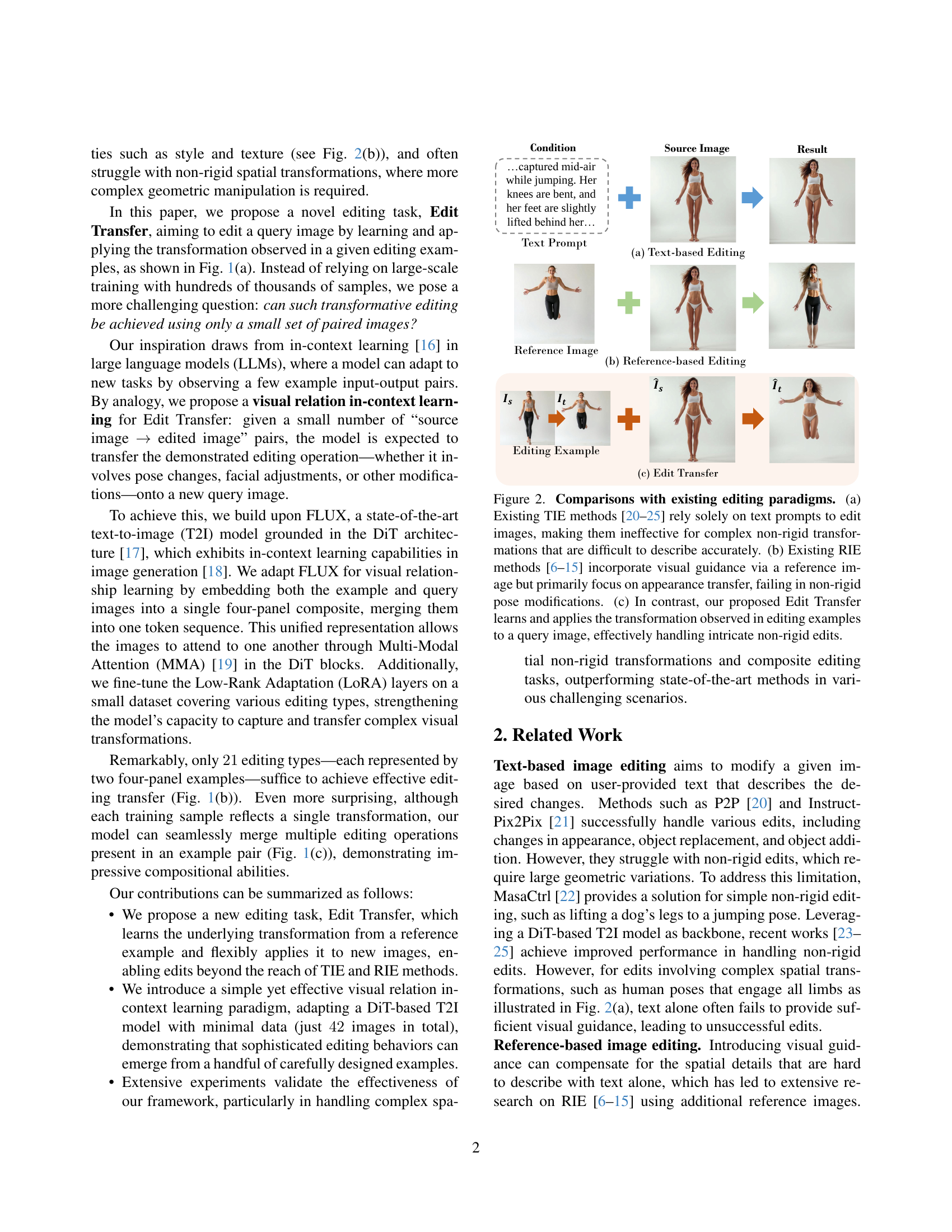

🔼 This figure compares three image editing approaches: text-based image editing (TIE), reference-based image editing (RIE), and the proposed Edit Transfer method. (a) illustrates the limitations of TIE, showing that complex, non-rigid transformations are hard to describe accurately using only text prompts. (b) demonstrates how RIE methods, while incorporating visual guidance, often struggle with non-rigid pose changes because they mainly focus on transferring appearance. (c) highlights that the novel Edit Transfer method overcomes these limitations by learning the transformation from a source-target pair and effectively applying it to new images, thus handling complex non-rigid edits.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparisons with existing editing paradigms. (a) Existing TIE methods [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] rely solely on text prompts to edit images, making them ineffective for complex non-rigid transformations that are difficult to describe accurately. (b) Existing RIE methods [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] incorporate visual guidance via a reference image but primarily focus on appearance transfer, failing in non-rigid pose modifications. (c) In contrast, our proposed Edit Transfer learns and applies the transformation observed in editing examples to a query image, effectively handling intricate non-rigid edits.

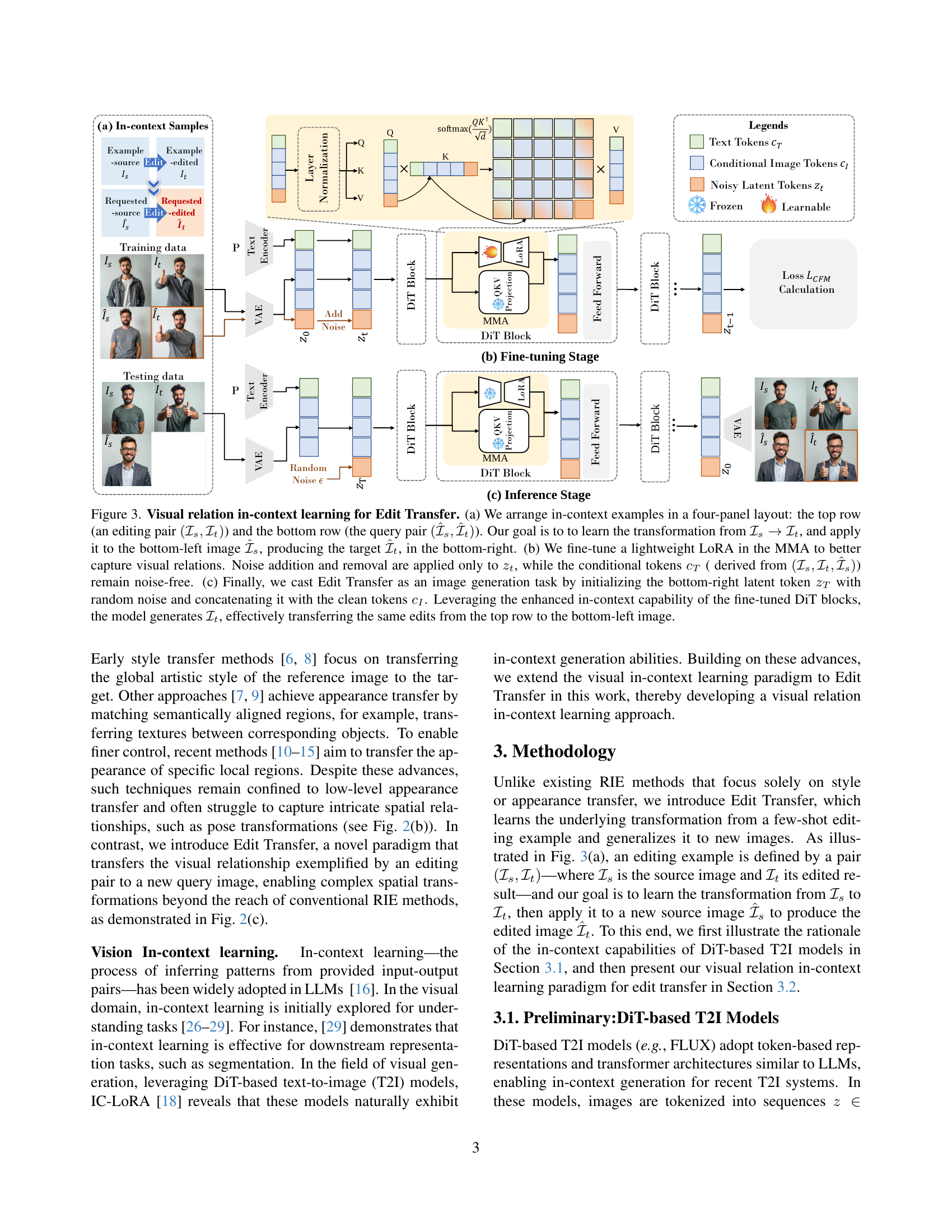

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the visual relation in-context learning process used in Edit Transfer. Panel (a) shows the four-panel input arrangement: the top row contains an example source image and its corresponding edited version, while the bottom row shows a new query image and its to-be-generated edited version. The model learns the transformation from the top row and applies it to the query image. Panel (b) details the fine-tuning process where a lightweight LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) is applied to the Multi-Modal Attention (MMA) module to improve the model’s ability to capture the visual relationship between the images. Noise is added and removed only from the latent tokens representing the edited image, while the conditional tokens remain noise-free. Panel (c) depicts the final image generation step, where the latent token is initialized with random noise, combined with clean tokens, and then passed through the refined DiT (Diffusion Transformer) blocks to produce the final edited query image.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual relation in-context learning for Edit Transfer. (a) We arrange in-context examples in a four-panel layout: the top row (an editing pair (ℐs,ℐt)subscriptℐ𝑠subscriptℐ𝑡(\mathcal{I}_{s},\mathcal{I}_{t})( caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT )) and the bottom row (the query pair (ℐ^s,ℐ^t)subscript^ℐ𝑠subscript^ℐ𝑡(\mathcal{\hat{I}}_{s},\mathcal{\hat{I}}_{t})( over^ start_ARG caligraphic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , over^ start_ARG caligraphic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT )). Our goal is to to learn the transformation from ℐs→ℐt→subscriptℐ𝑠subscriptℐ𝑡\mathcal{I}_{s}\to\mathcal{I}_{t}caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT → caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, and apply it to the bottom-left image ℐ^ssubscript^ℐ𝑠\hat{\mathcal{I}}_{s}over^ start_ARG caligraphic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, producing the target ℐ^tsubscript^ℐ𝑡\hat{\mathcal{I}}_{t}over^ start_ARG caligraphic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, in the bottom-right. (b) We fine-tune a lightweight LoRA in the MMA to better capture visual relations. Noise addition and removal are applied only to ztsubscript𝑧𝑡z_{t}italic_z start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, while the conditional tokens cTsubscript𝑐𝑇c_{T}italic_c start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( derived from (ℐs,ℐt,ℐ^s)subscriptℐ𝑠subscriptℐ𝑡subscript^ℐ𝑠(\mathcal{I}_{s},\mathcal{I}_{t},\hat{\mathcal{I}}_{s})( caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , over^ start_ARG caligraphic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT )) remain noise-free. (c) Finally, we cast Edit Transfer as an image generation task by initializing the bottom-right latent token zTsubscript𝑧𝑇z_{T}italic_z start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT with random noise and concatenating it with the clean tokens cIsubscript𝑐𝐼c_{I}italic_c start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_I end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. Leveraging the enhanced in-context capability of the fine-tuned DiT blocks, the model generates ℐtsubscriptℐ𝑡\mathcal{I}_{t}caligraphic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, effectively transferring the same edits from the top row to the bottom-left image.

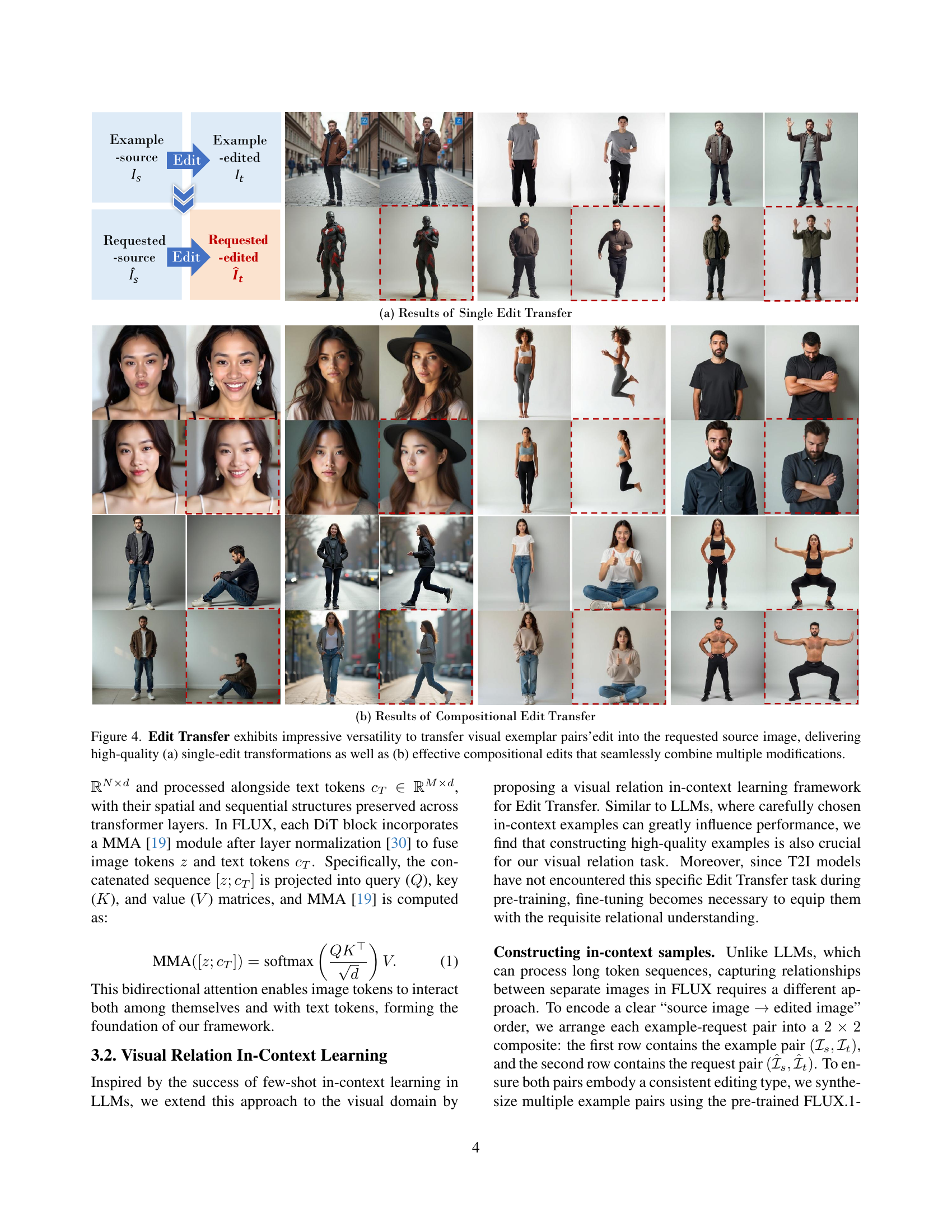

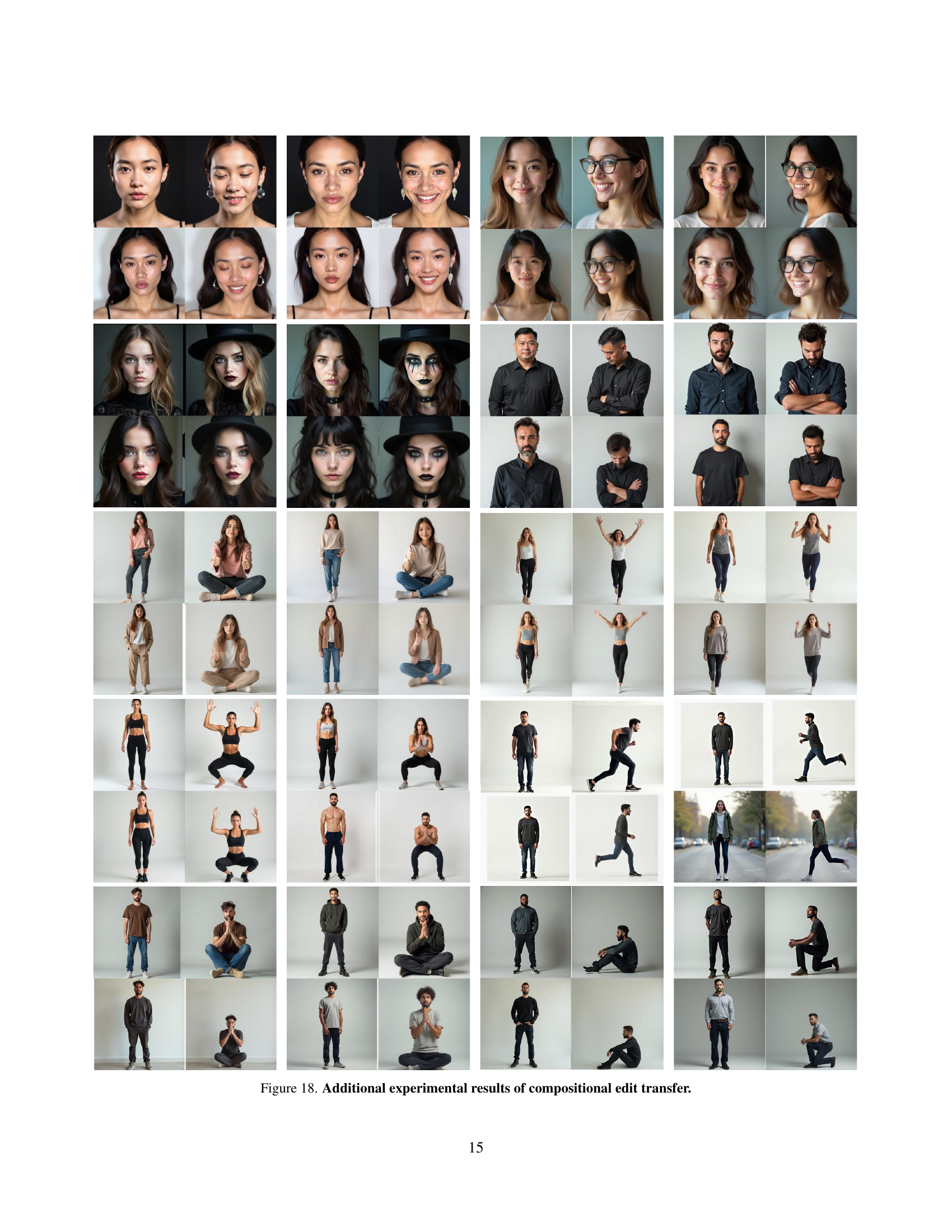

🔼 Figure 4 demonstrates the capabilities of Edit Transfer in handling both single and multiple edits. The top row (a) showcases examples where a single editing transformation (e.g., changing a person’s pose) from a source-target image pair is successfully applied to a new query image. The bottom row (b) shows examples of ‘compositional edits,’ where multiple edits from a single source-target example are successfully combined and applied to a new image. This highlights the model’s ability to learn complex transformations and apply them effectively to unseen images.

read the caption

Figure 4: Edit Transfer exhibits impressive versatility to transfer visual exemplar pairs’edit into the requested source image, delivering high-quality (a) single-edit transformations as well as (b) effective compositional edits that seamlessly combine multiple modifications.

🔼 Figure 5 presents a qualitative comparison of different image editing methods. It showcases the results of several techniques, including text-based image editing (TIE), reference-based image editing (RIE), and the proposed Edit Transfer method. The goal is to illustrate the Edit Transfer method’s superior performance in handling complex, non-rigid transformations, such as changes in pose and viewpoint. The figure displays a series of image edits performed by each technique, allowing for a visual comparison of the results. Detailed text prompts used for TIE methods are provided separately in Section B.1 of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative comparisons. Compared with TIE and RIE methods, our method consistently outperforms in various non-rigid editing tasks. We provide the detailed text prompt of TIE methods in Section B.1.

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comparison of Edit Transfer with three other image editing methods: P2P, RF-Solver-Edit, and MimicBrush. The comparison is done through both a user study and a VLM (Vision-Language Model) evaluation. Part (a) shows the percentage of users who preferred Edit Transfer over the other methods. Part (b) displays the average scores assigned to each method by the GPT-40 model, indicating the overall performance perceived by the AI.

read the caption

Figure 6: Results of user study and VLM evaluation. We compare our Edit Transfer (IV) with P2P [20] (I), RF-Solver-Edit [23] (II) and MimicBrush [13] (III). (a) The values show the proportion of users who prefer our method over the others. (b) The values represent the average scores given to each method by GPT-4o [31].

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of dataset size on the model’s performance in Edit Transfer. Panel (a) shows that using only two training samples per editing type is enough to achieve effective non-rigid edits, even with a limited number (10) of editing types. Panel (b) illustrates that expanding the dataset to 21 editing types significantly improves the model’s ability to handle subtle local edits and enhances its generalization capabilities, even when there is a spatial mismatch between the editing example and the query image.

read the caption

Figure 7: Influence of dataset scale. (a) Setting the number of training samples per editing type to Nc=2subscript𝑁𝑐2N_{c}=2italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_c end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 2 is sufficient for learning effective non-rigid edits, even when the total number of editing types NT=10subscript𝑁𝑇10N_{T}=10italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 10. (b) Increasing NT=21subscript𝑁𝑇21N_{T}=21italic_N start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = 21 further improves the model’s ability to capture subtle local edits and enhances its generalization to cases where the editing example and query image are spatially misaligned.

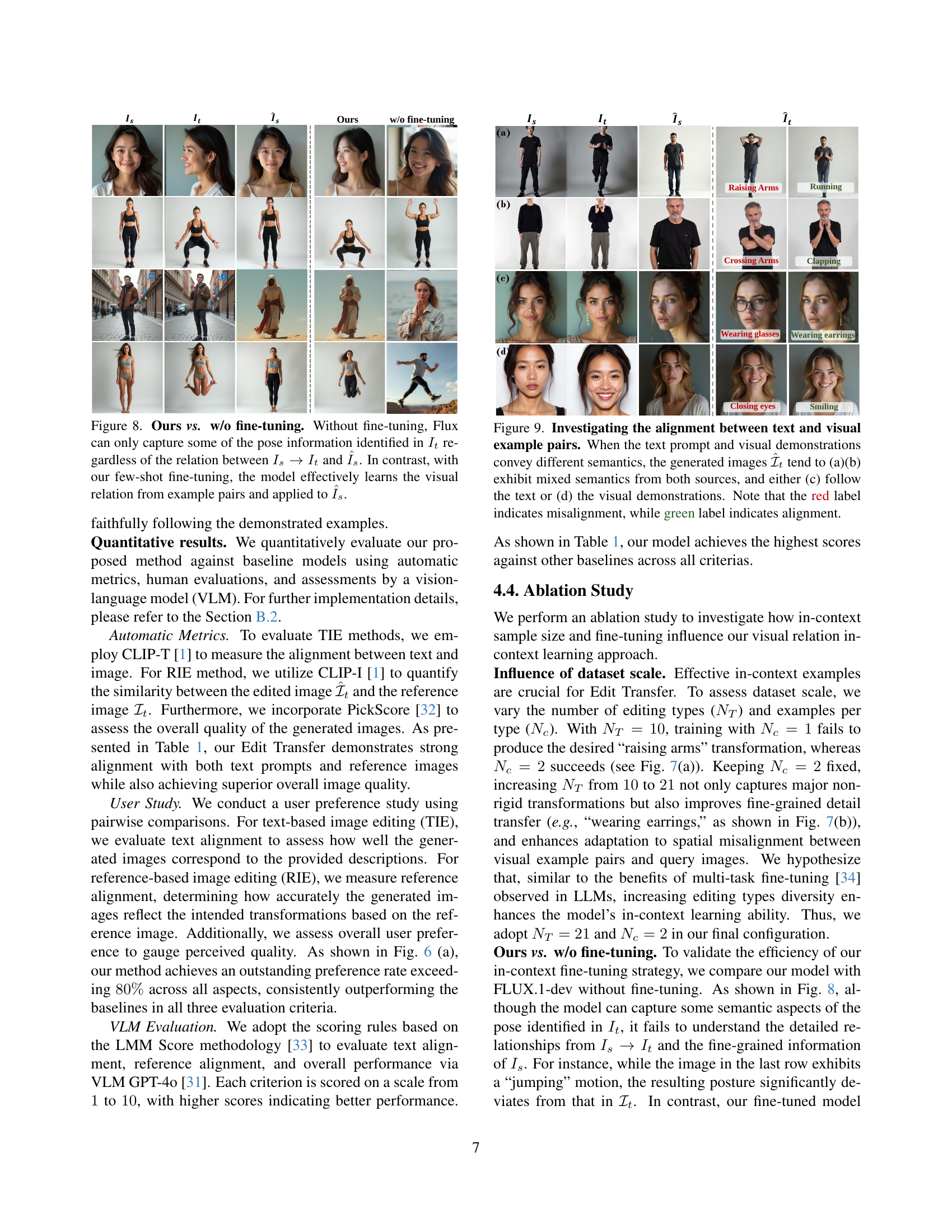

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed Edit Transfer method with and without fine-tuning. The left column shows the results of the proposed method with fine-tuning, demonstrating its ability to accurately transfer complex pose information from a source image-edited image pair to a new query image. In contrast, the right column shows the results without fine-tuning, which only partially captures the pose information from the source image-edited image pair, indicating that fine-tuning is essential for effective visual relation learning. This highlights the few-shot learning capability of the proposed approach, where minimal training data enables effective adaptation to new images.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ours vs. w/o fine-tuning. Without fine-tuning, Flux can only capture some of the pose information identified in Itsubscript𝐼𝑡I_{t}italic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT regardless of the relation between Is→It→subscript𝐼𝑠subscript𝐼𝑡I_{s}\to I_{t}italic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT → italic_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and I^ssubscript^𝐼𝑠\hat{I}_{s}over^ start_ARG italic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. In contrast, with our few-shot fine-tuning, the model effectively learns the visual relation from example pairs and applied to I^ssubscript^𝐼𝑠\hat{I}_{s}over^ start_ARG italic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT.

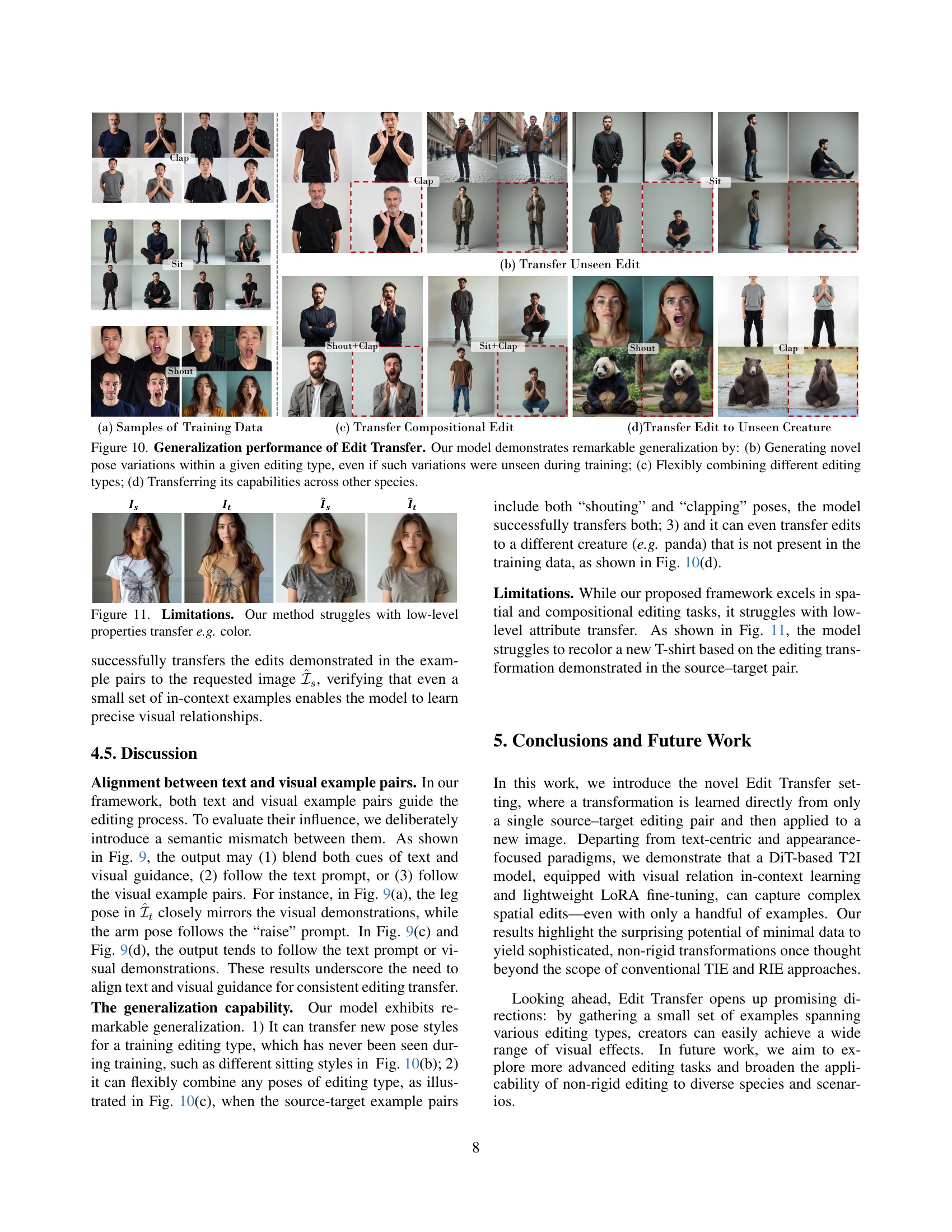

🔼 This figure explores the impact of inconsistencies between textual prompts and visual examples in image editing. The experiment shows that when the text prompt and visual example convey different meanings, the generated images often reflect a blend of both (a, b). In other cases, the generated image may solely reflect the text (c) or the visual example (d). Red labels highlight mismatches between the prompt and generated image, while green indicates alignment.

read the caption

Figure 9: Investigating the alignment between text and visual example pairs. When the text prompt and visual demonstrations convey different semantics, the generated images ℐ^tsubscript^ℐ𝑡\hat{\mathcal{I}}_{t}over^ start_ARG caligraphic_I end_ARG start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT tend to (a)(b) exhibit mixed semantics from both sources, and either (c) follow the text or (d) the visual demonstrations. Note that the red label indicates misalignment, while green label indicates alignment.

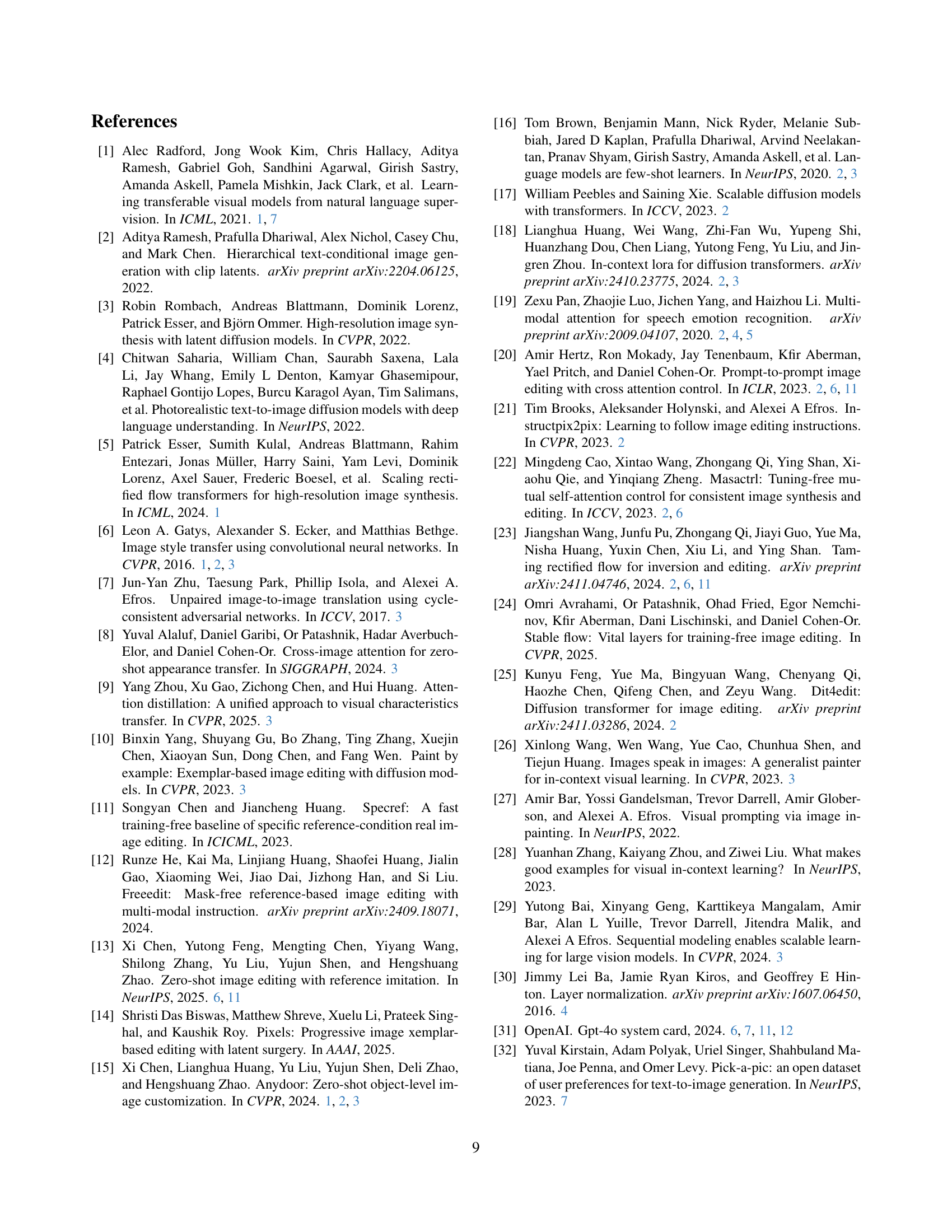

🔼 Figure 10 showcases the generalization capabilities of the Edit Transfer model. The figure demonstrates that the model can (b) generate novel pose variations within a single editing type, even without seeing those variations during training; (c) flexibly combine multiple editing types to create more complex edits; and (d) successfully transfer the learned editing capabilities to images of different species (e.g., applying human pose edits to an animal). This highlights the model’s ability to generalize beyond the specific training examples.

read the caption

Figure 10: Generalization performance of Edit Transfer. Our model demonstrates remarkable generalization by: (b) Generating novel pose variations within a given editing type, even if such variations were unseen during training; (c) Flexibly combining different editing types; (d) Transferring its capabilities across other species.

🔼 Figure 11 demonstrates the limitations of the proposed Edit Transfer method. Specifically, it shows that the model struggles with transferring low-level image properties, such as color changes. While the model excels at transferring complex spatial transformations and pose changes, as shown in previous figures, it cannot reliably change color attributes of an image, even when given a direct example of the desired color change. This highlights a key limitation in the approach and suggests areas for future research to improve the model’s ability to handle low-level property transfers.

read the caption

Figure 11: Limitations. Our method struggles with low-level properties transfer e.g. color.

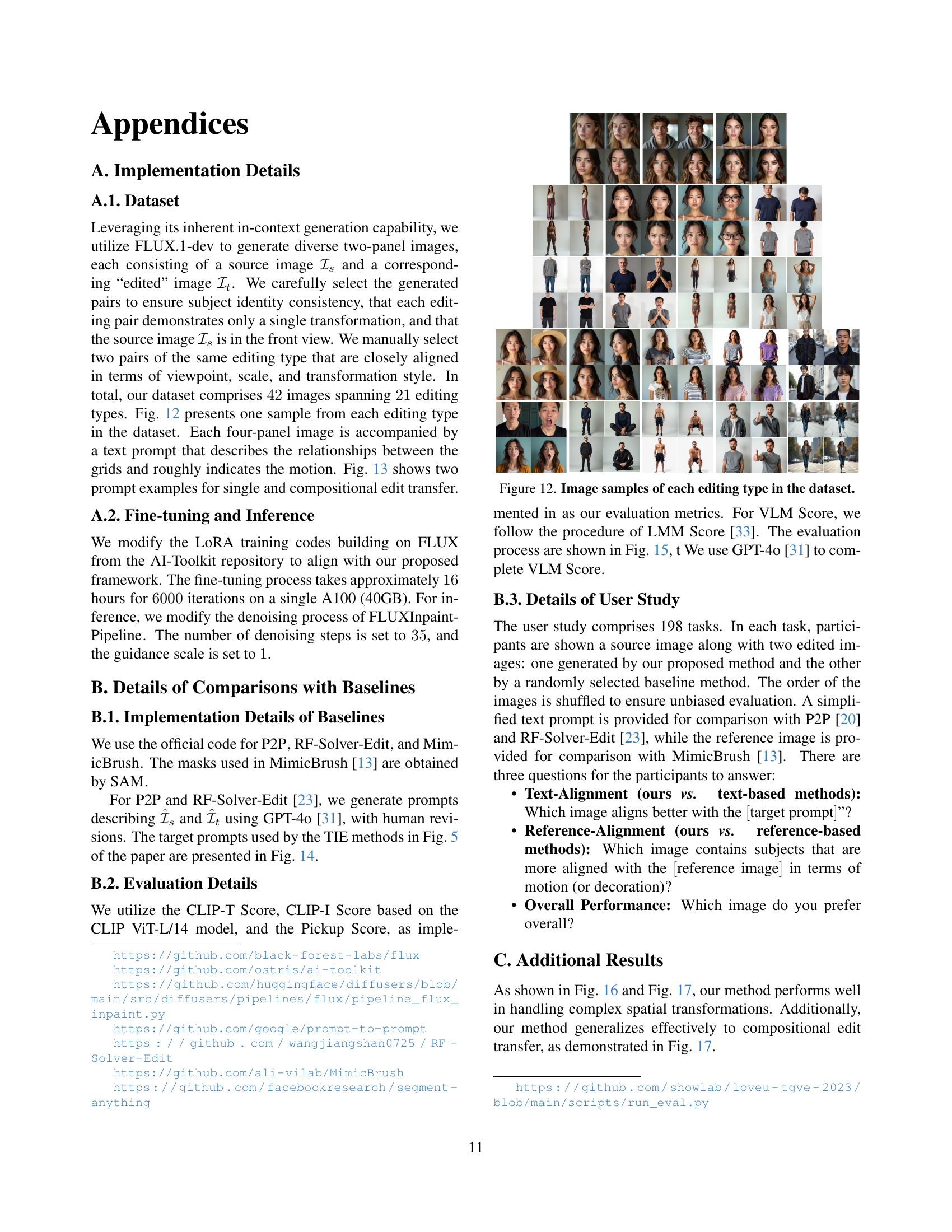

🔼 This figure shows examples of the 21 different editing types used in the Edit Transfer dataset. Each editing type is represented by two example image pairs: a source image and its corresponding edited version. The editing types cover a variety of transformations, including changes in pose, expression, clothing, and accessories. The figure provides a visual representation of the diversity and complexity of the edits that the model is trained to perform.

read the caption

Figure 12: Image samples of each editing type in the dataset.

🔼 This figure details the prompt template used in the Vision-Language Model (VLM) evaluation section of the paper. The prompt guides the evaluator through a role-play scenario, presenting them with source images and editing prompts. Evaluators assess the quality of edited images generated by three different methods based on two metrics: Editing Accuracy (how well the edit matches the prompt) and Overall Performance (the overall quality and coherence of the edited image). The evaluators provide their scores in a structured JSON format for each image.

read the caption

Figure 15: Prompt template of VLM score.

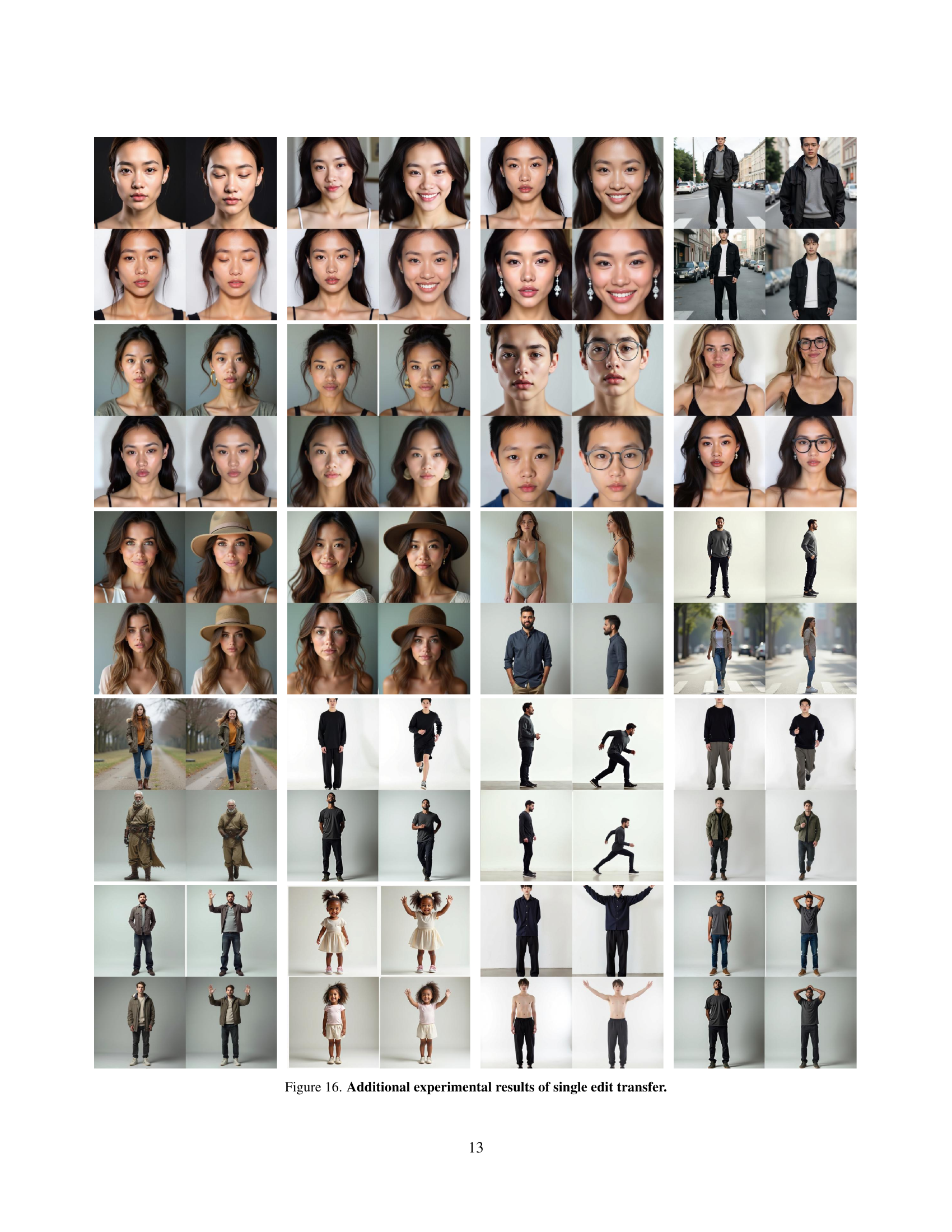

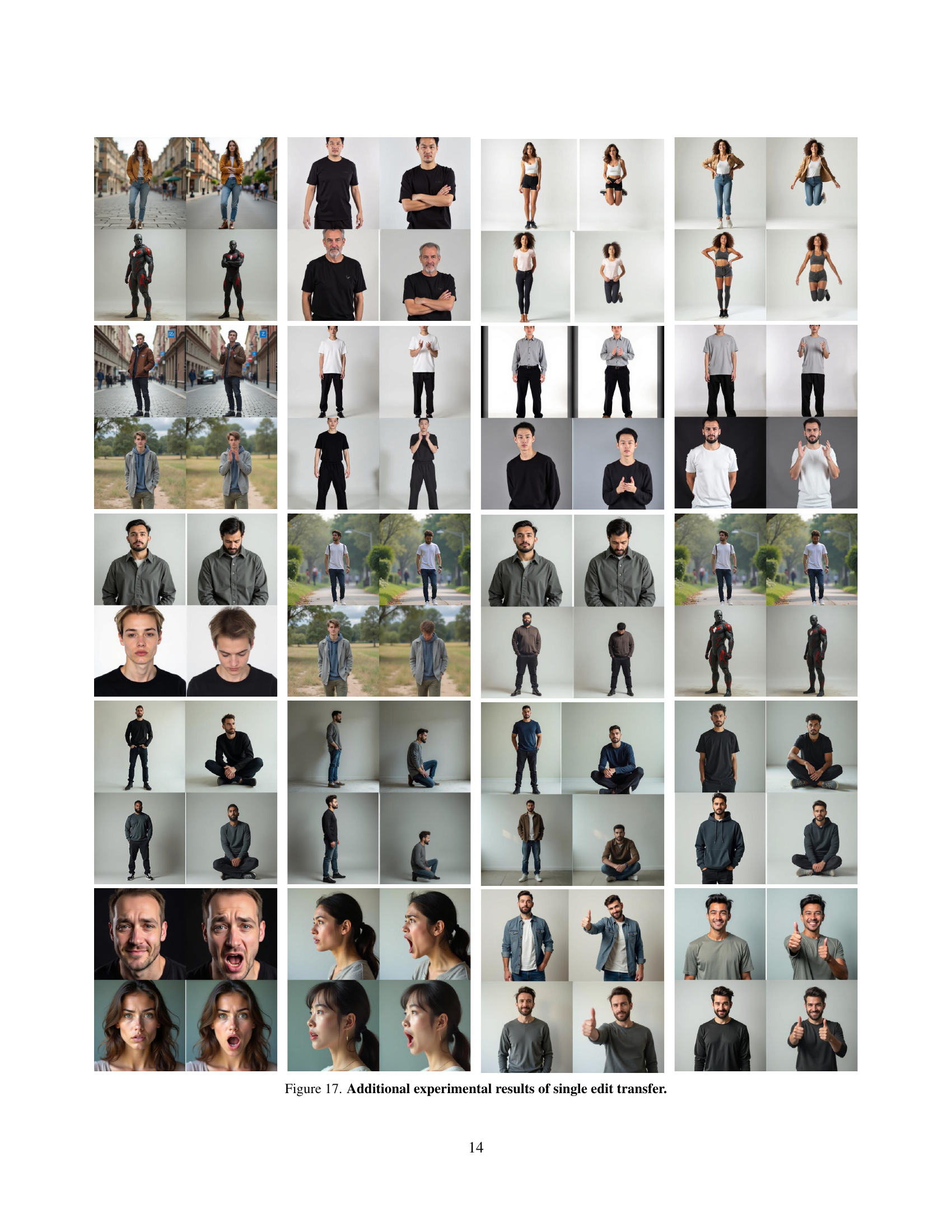

🔼 This figure displays further examples of single edit transfer, showcasing the model’s ability to successfully apply learned transformations from a single source-target example to new query images. The edits demonstrate the model’s capability of handling diverse non-rigid transformations, including changes in pose, facial expressions, clothing, and background. The results highlight the model’s flexibility and generalizability in transferring edits.

read the caption

Figure 16: Additional experimental results of single edit transfer.

Full paper#