TL;DR#

Generating synchronized video and audio has been a difficult task, requiring larger and more complex models. The generation of dance movements from music is challenging due to the need to simultaneously consider multiple aspects, like style and beat. Current methods depend on motion capture data which is resource-intensive. To resolve this, the paper introduces MusicInfuser.

MusicInfuser adapts pre-trained text-to-video models to condition on music tracks using music-video cross-attention and a low-rank adapter. This method generates videos synchronized with the input music, with styles and appearances controllable via text prompts. MusicInfuser preserves the rich knowledge in the text modality, enabling various forms of control, while also introducing an evaluation framework using Video-LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper introduces MusicInfuser, a method to generate synchronized dance videos, offering a promising direction for AI-driven content creation. It leverages existing diffusion models, enhancing their capabilities without extensive retraining, and opens avenues for further exploration in AI-assisted choreography.

Visual Insights#

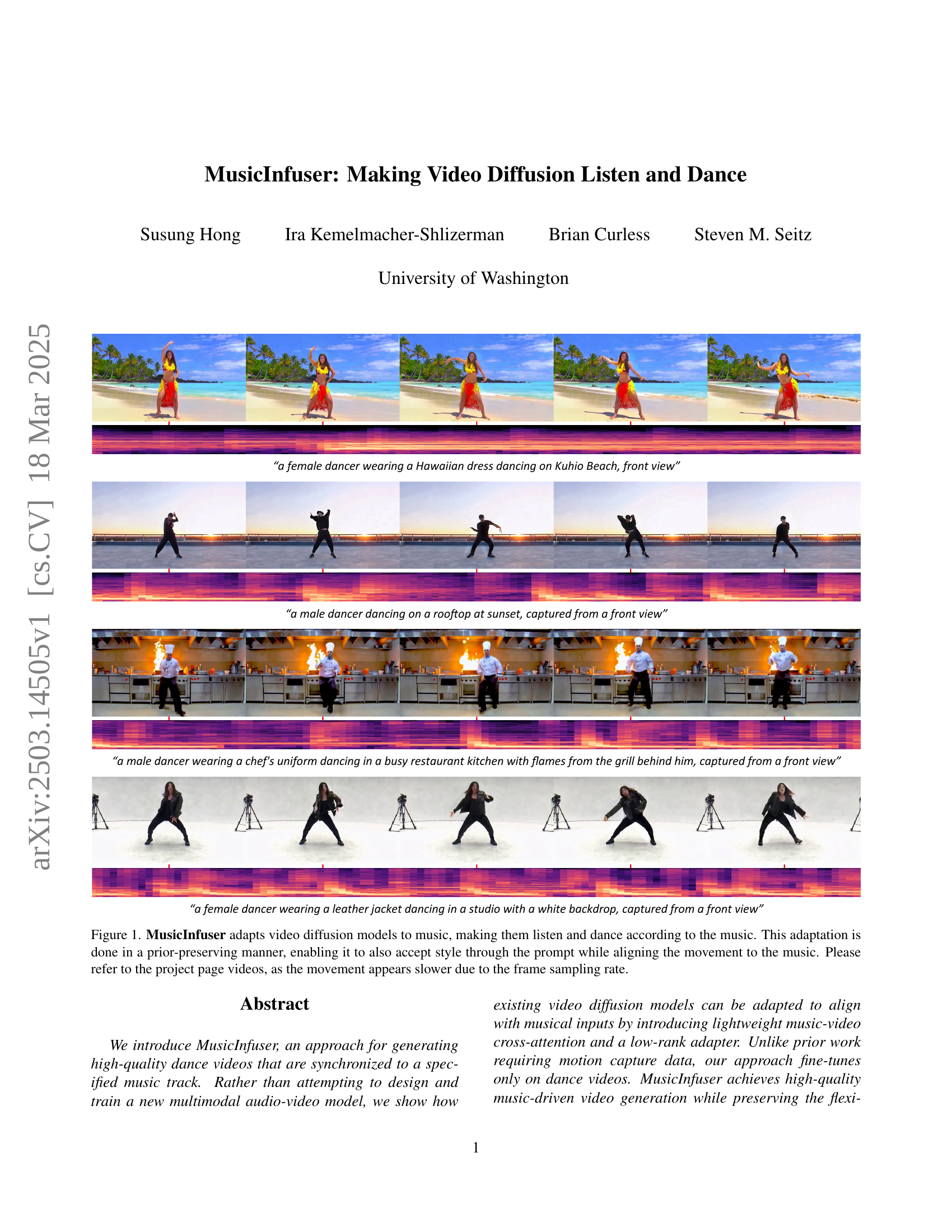

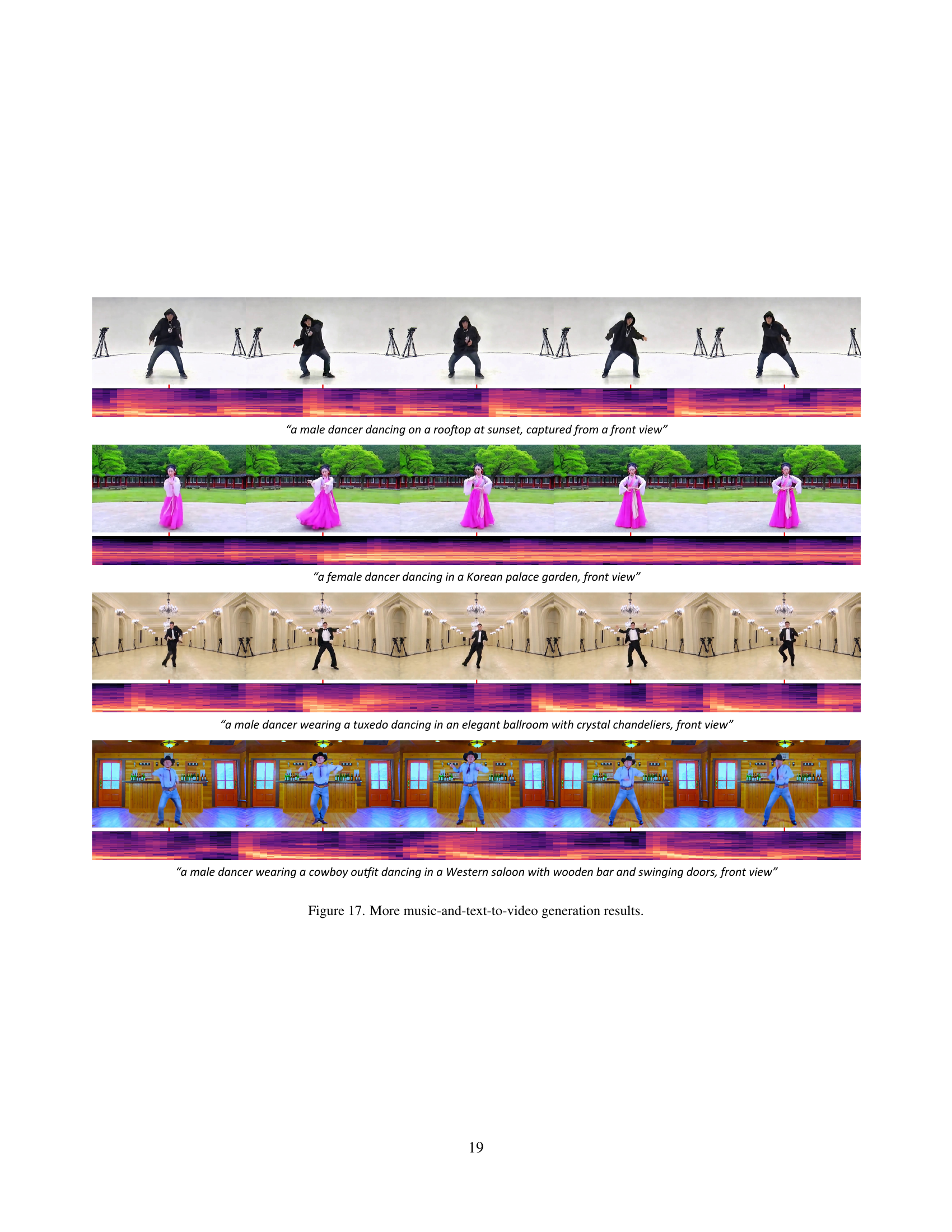

🔼 MusicInfuser modifies pre-trained video diffusion models to generate dance videos synchronized with music. It does this by adding a lightweight cross-attention module and a low-rank adapter that aligns the model’s output to the rhythm and style of the music input. The figure shows four examples of generated dance videos, each conditioned on a specific text prompt and a music track. Note that the movement may appear slower than in the actual videos due to the frame rate used to create the figure.

read the caption

Figure 1: MusicInfuser adapts video diffusion models to music, making them listen and dance according to the music. This adaptation is done in a prior-preserving manner, enabling it to also accept style through the prompt while aligning the movement to the music. Please refer to the project page videos, as the movement appears slower due to the frame sampling rate.

| Model | Modality | Style | Beat | Body | Movement | Choreography | Dance Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment | Alignment | Representation | Realism | Complexity | Average | ||

| AIST Dataset (GT) [46] | A+V | 7.46 | 8.95 | 7.53 | 8.67 | 7.45 | 8.01 |

| MM-Diffusion [39] | A+V | 7.16 | 8.56 | 5.52 | 7.05 | 7.53 | 7.16 |

| Mochi [44] | T+V | 7.20 | 8.34 | 7.47 | 7.68 | 7.82 | 7.70 |

| MusicInfuser (Ours) | T+A+V | 7.56 | 8.89 | 7.16 | 8.24 | 7.90 | 7.95 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the dance generation quality produced by different models: MusicInfuser (the proposed model), MM-Diffusion, and Mochi. The quality is assessed across six key aspects: style alignment, beat alignment, body representation, movement realism, choreography complexity, and an overall dance quality score. Each metric is scored on a scale, and for models using text input (MusicInfuser and Mochi), an average score across a predefined set of prompts is reported, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Dance quality metrics comparing different models. A, V, and T denote audio, video, and text input modalities, respectively. For the models that have text input modality, we report an average of scores using a predefined benchmark of prompts.

In-depth insights#

Music-Aligned T2V#

The concept of ‘Music-Aligned T2V’ (Text-to-Video) focuses on generating videos where the visual content is synchronized with and responsive to a given music track. This involves more than just adding background music; it requires the AI model to understand the nuances of the music, such as its rhythm, tempo, and emotional tone, and translate these into corresponding visual movements and actions within the generated video. A key challenge is ensuring the generated motion isn’t simply random but meaningfully related to the audio, creating a cohesive and aesthetically pleasing experience. This can be achieved through techniques like incorporating cross-modal attention mechanisms, which allow the model to learn correlations between audio features and visual elements. The ultimate goal is to enable users to create compelling and engaging video content that seamlessly integrates music and visuals, opening up new possibilities for artistic expression and creative applications in fields like music visualization, dance performance, and interactive media.

ZICA for Fidelity#

Zero-Initialized Cross-Attention (ZICA) likely aims to preserve the fidelity of a generative model when incorporating a new modality (e.g., audio). By initializing the cross-attention weights to zero, the model initially ignores the audio input, ensuring it continues to generate images or videos consistent with its pre-trained knowledge. This prevents abrupt changes in the output structure and style. As training progresses, the cross-attention weights gradually increase, allowing the audio to influence the generation process in a controlled manner. This approach helps to maintain the core visual structure and stylistic elements the model already knows how to produce, then gently nudge it using musical cues. A balanced method to adapt to new modalities, preserving a rich style!

HR-LoRA for Motion#

HR-LoRA which stands for Higher Rank Low-Rank Adaptation aims to adapt the attention weights for diffusion transformer blocks. The adapter serves two key purposes: (1) to effectively integrate audio features into the text-video processing pipeline, and (2) to shift the domain toward our target application, synthesizing clear choreography. To effectively model motion adaptation separately from spatial adaptation, the optimal rank for the linear map is increased compared to what is needed for static images. For adapting video tokens, a higher rank is required compared to image tokens, since video tokens contain temporal information.

Video-LLM Eval#

Regarding “Video-LLM Eval,” my thoughts center on the crucial role of Video Large Language Models (LLMs) in evaluating video generation quality. Traditional metrics often fail to capture nuanced aspects like motion realism, style adherence, and synchronization in dance videos. Video-LLMs offer a promising avenue by leveraging their ability to understand both visual content and natural language. A Video-LLM evaluation framework could assess multiple dimensions of dance quality, video quality, and prompt alignment. Challenges include designing effective prompts for the Video-LLM and ensuring its evaluation aligns with human perception. Training or fine-tuning the Video-LLM specifically for evaluating dance videos might be necessary. The framework should also consider the inherent subjectivity in evaluating creative content. Addressing these challenges could lead to a more comprehensive and reliable assessment of dance video generation, pushing the boundaries of automated evaluation in multimodal AI.

Wild Data Robust.#

Considering the idea of a “Wild Data Robust” heading, it suggests a focus on model performance and generalization in real-world, uncontrolled environments. Research in this area would likely explore techniques to make systems resilient to the noise, variability, and biases inherent in uncurated data. Key aspects would involve data augmentation strategies to simulate diverse conditions, robust loss functions that down-weight outliers, and domain adaptation methods to transfer knowledge from labeled to unlabeled or weakly labeled wild datasets. Evaluating robustness would necessitate benchmarks that accurately reflect the challenges of real-world deployment, focusing on metrics beyond average performance to capture worst-case scenarios and fairness across different subgroups. Investigations might involve leveraging self-supervised learning or continual learning paradigms to enable models to adapt and improve over time as they encounter new and evolving wild data distributions, making them more reliable and less prone to failure in unpredictable settings. A primary goal is to bridge the gap between idealized training conditions and the complexities of real-world applications, improving the practical utility of AI systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

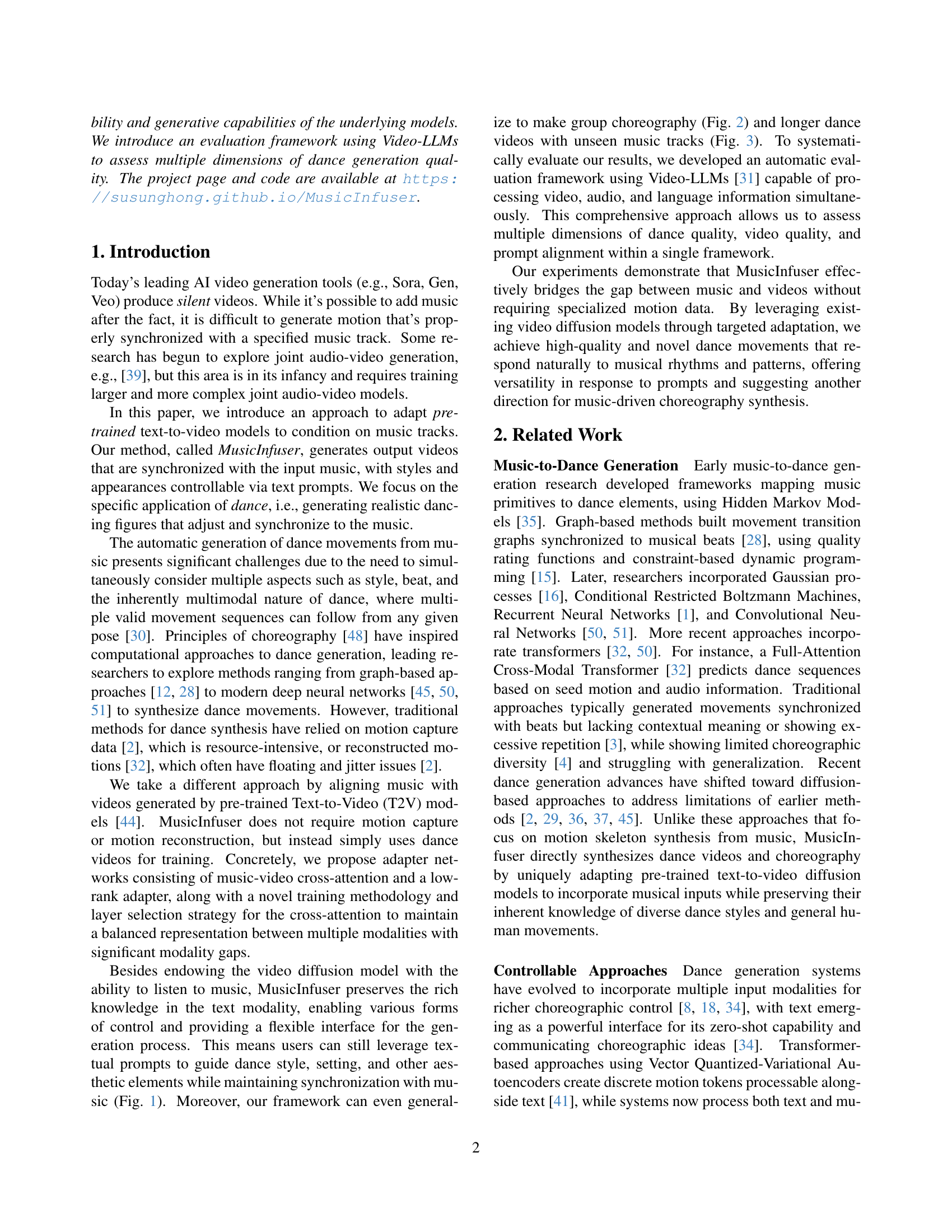

🔼 Figure 2 demonstrates the model’s ability to generate group dance videos. The key is leveraging the model’s existing knowledge of dance and text, and modifying only the prompt. By changing the word ‘[DANCERS]’ in the prompt ‘’[DANCERS] dancing in a studio with a white backdrop, captured from a front view’ to specify the number of dancers (e.g., ‘a male and female dancer’, ‘multiple dancers’, ‘a group of dancers’), the model generates corresponding videos with the correct number of dancers performing synchronized choreography.

read the caption

Figure 2: Due to the conservation of knowledge in video and text modalities, our model generalizes to generate group dance videos by modulating the prompt. To show this, the prompt is set to “[DANCERS] dancing in a studio with a white backdrop, captured from a front view,” where [DANCERS] denotes the description for each number of dancers.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate longer dance videos (twice the length of training videos) using unseen music. Each row shows a different video generated using synthetic K-pop music (a genre not present in the AIST dataset) and the prompt ‘a professional dancer dancing K-pop…’. The consistent synchronization between the dance moves and music beat, along with stylistic consistency, highlights the model’s generalizability and robustness to new, unseen music.

read the caption

Figure 3: We generate longer dance videos that are 2 times longer than the videos used for training. For each row, we use synthetic in-the-wild music tracks with a keyword “K-pop,” a type of music not existing in AIST [46], and use a prompt “a professional dancer dancing K-pop ….” This shows our method is highly generalizable, even extending to longer videos with an unheard cateory of the music. The beat and style alignment can be more clearly observed in the videos on the project page.

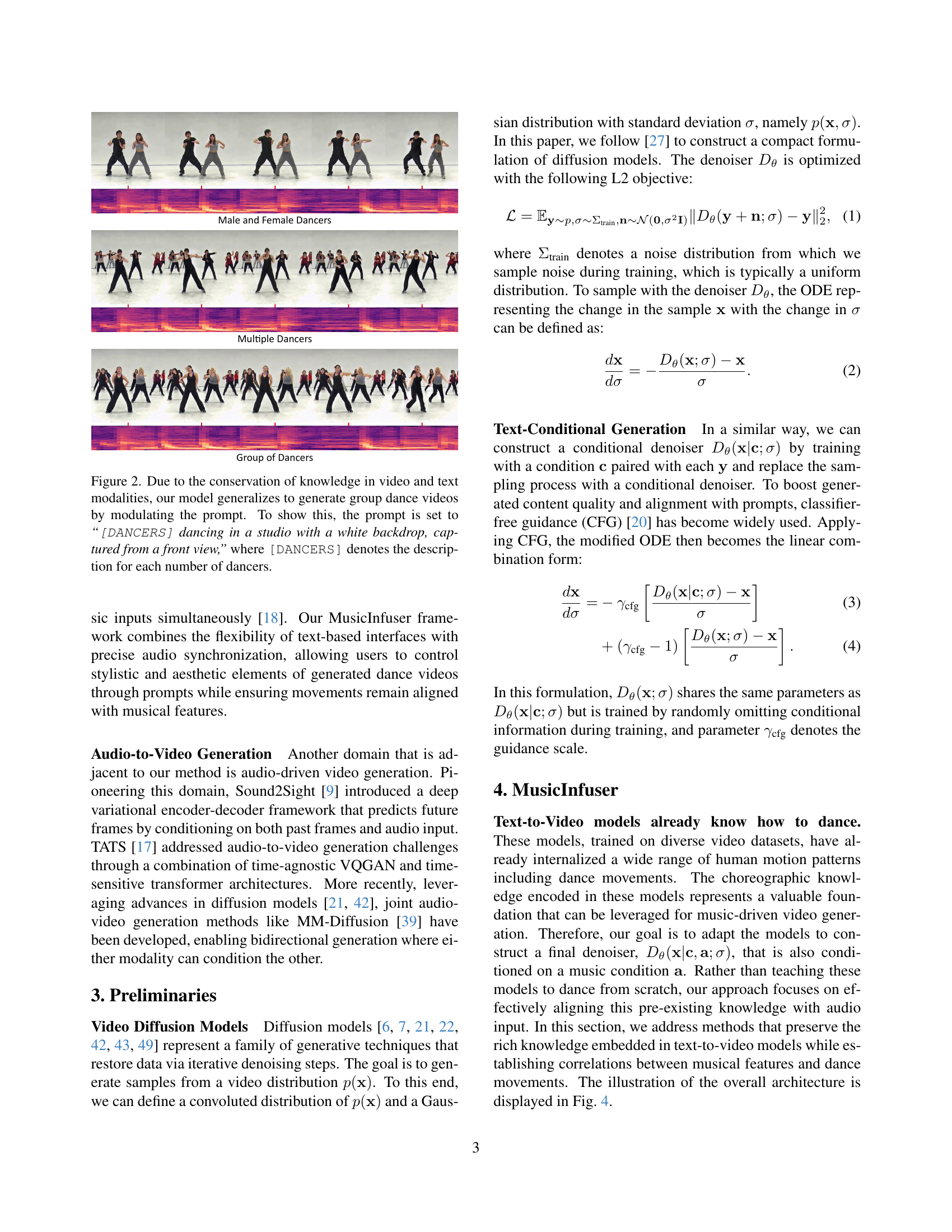

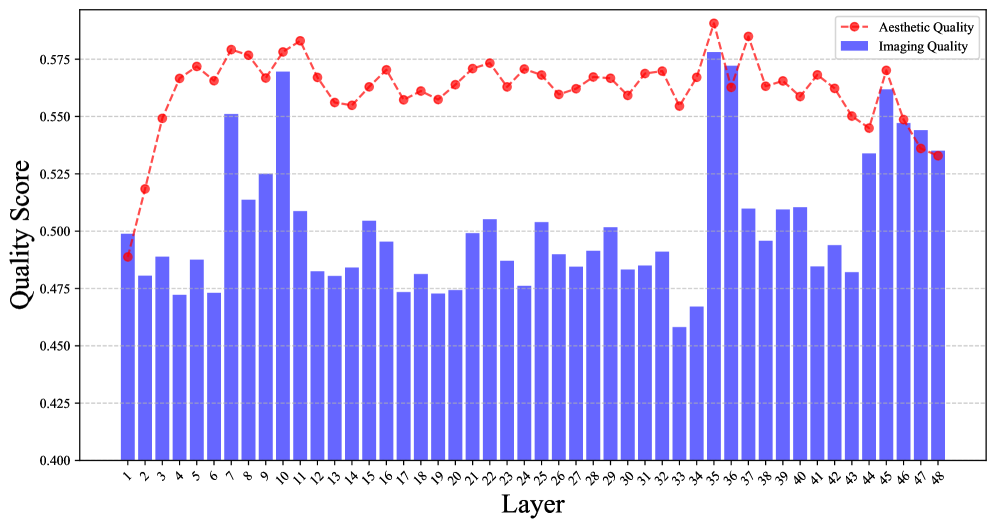

🔼 MusicInfuser’s architecture modifies a pretrained text-to-video diffusion model to incorporate music. It does so by adding two types of adapter networks: Zero-Initialized Cross-attention (ZICA) blocks and High-Rank LoRA (HR-LoRA) blocks. ZICA blocks introduce music information using cross-attention, while HR-LoRA blocks adapt the attention weights within the diffusion model’s transformer layers. The placement of the ZICA blocks is strategically determined to balance the impact on different aspects of the generated video while minimizing computational cost, using a layer adaptability strategy described in section 4.6. The diagram visually depicts the flow of information (text, audio, and video) through these components, indicating which blocks are trainable and showing the overall process of music-conditioned video generation.

read the caption

Figure 4: Overall architecture of MusicInfuser. Our framework adapts a pre-trained diffusion model with audio embedding using ZICA blocks (Sec. 4.1) and HR-LoRA blocks (Sec. 4.2). The placement of ZICA blocks is selected based on layer adaptability (Sec. 4.6).

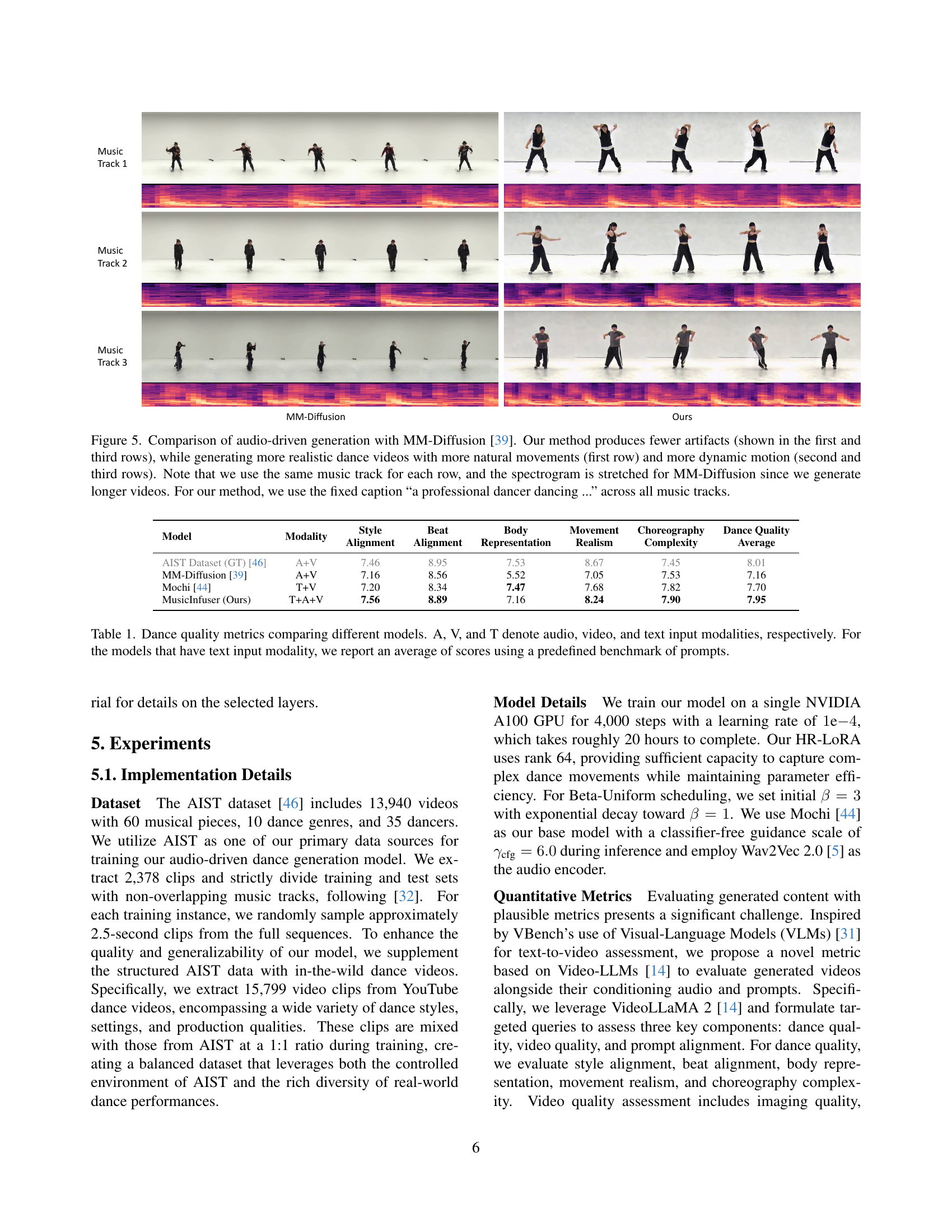

🔼 Figure 5 compares the dance videos generated by MusicInfuser and MM-Diffusion [39], a prior state-of-the-art method. The figure uses three music tracks as input. For each track, both methods generate dance videos. The first and third rows show that MusicInfuser produces fewer artifacts compared to MM-Diffusion. The first row demonstrates that MusicInfuser generates videos with more realistic and natural movements. The second and third rows highlight the more dynamic motion produced by MusicInfuser. Note that the same music track was used for each row, but the spectrogram is stretched for MM-Diffusion because MusicInfuser generates longer videos than MM-Diffusion. For MusicInfuser, the prompt ‘a professional dancer dancing…’ was consistently used for all music tracks.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparison of audio-driven generation with MM-Diffusion [39]. Our method produces fewer artifacts (shown in the first and third rows), while generating more realistic dance videos with more natural movements (first row) and more dynamic motion (second and third rows). Note that we use the same music track for each row, and the spectrogram is stretched for MM-Diffusion since we generate longer videos. For our method, we use the fixed caption “a professional dancer dancing …” across all music tracks.

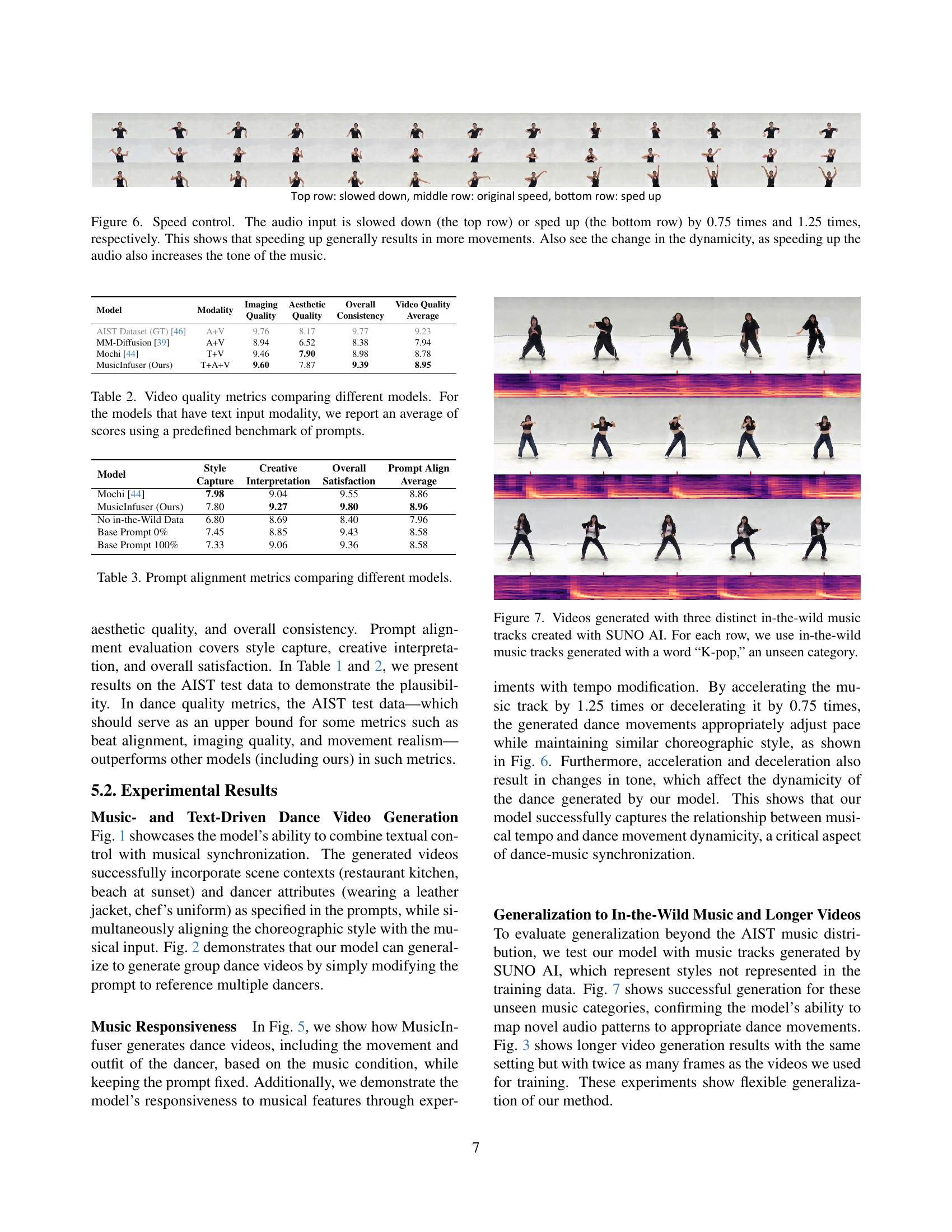

🔼 Figure 6 demonstrates the impact of altering the speed of the input audio on the generated dance video. The top row shows the dance when the audio is slowed down by a factor of 0.75, the middle row shows the original-speed dance, and the bottom row shows the dance when the audio is sped up by a factor of 1.25. The figure illustrates that increasing the audio speed leads to a greater number of movements in the generated dance and also changes the overall dynamic intensity and tone of the resulting dance.

read the caption

Figure 6: Speed control. The audio input is slowed down (the top row) or sped up (the bottom row) by 0.75 times and 1.25 times, respectively. This shows that speeding up generally results in more movements. Also see the change in the dynamicity, as speeding up the audio also increases the tone of the music.

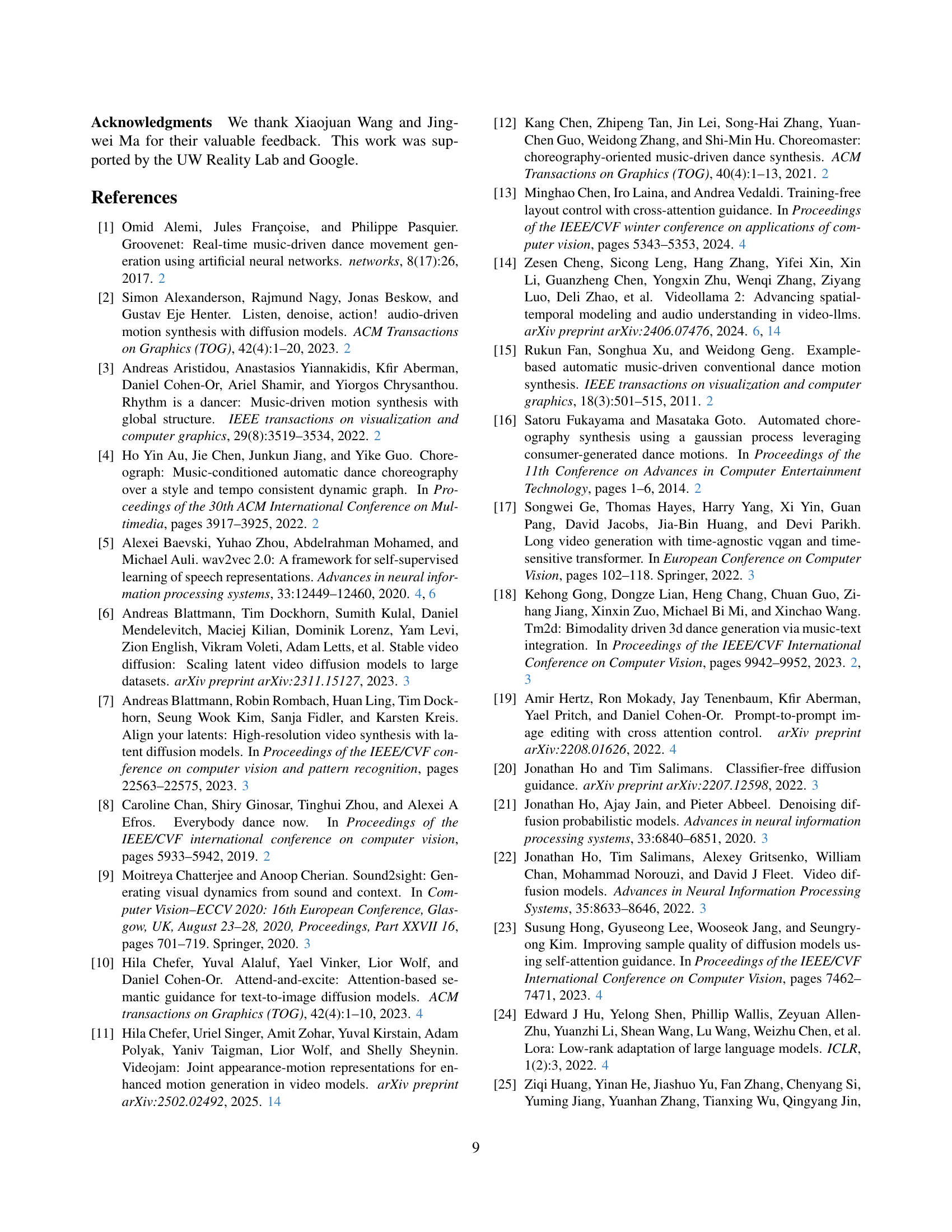

🔼 Figure 7 showcases the model’s ability to generalize to unseen music styles. Three distinct dance videos are generated, each synchronized to a different ‘K-pop’ music track created using SUNO AI. The ‘K-pop’ genre was not present in the training data, demonstrating the model’s ability to adapt and generate appropriate choreography for new musical styles.

read the caption

Figure 7: Videos generated with three distinct in-the-wild music tracks created with SUNO AI. For each row, we use in-the-wild music tracks generated with a word “K-pop,” an unseen category.

🔼 Figure 8 showcases the diversity achievable by MusicInfuser. Using the same music track and the text prompt “a professional dancer dancing…”, altering only the random seed results in several unique dance sequences. Each generated dance video features a distinct choreography, demonstrating the model’s capacity to produce varied creative outputs from the same inputs.

read the caption

Figure 8: By changing the seed, our method can produce diverse results given the same music and text. The generated choreography of each dance is different from each other. We use the fixed prompt “a professional dancer dancing ….”

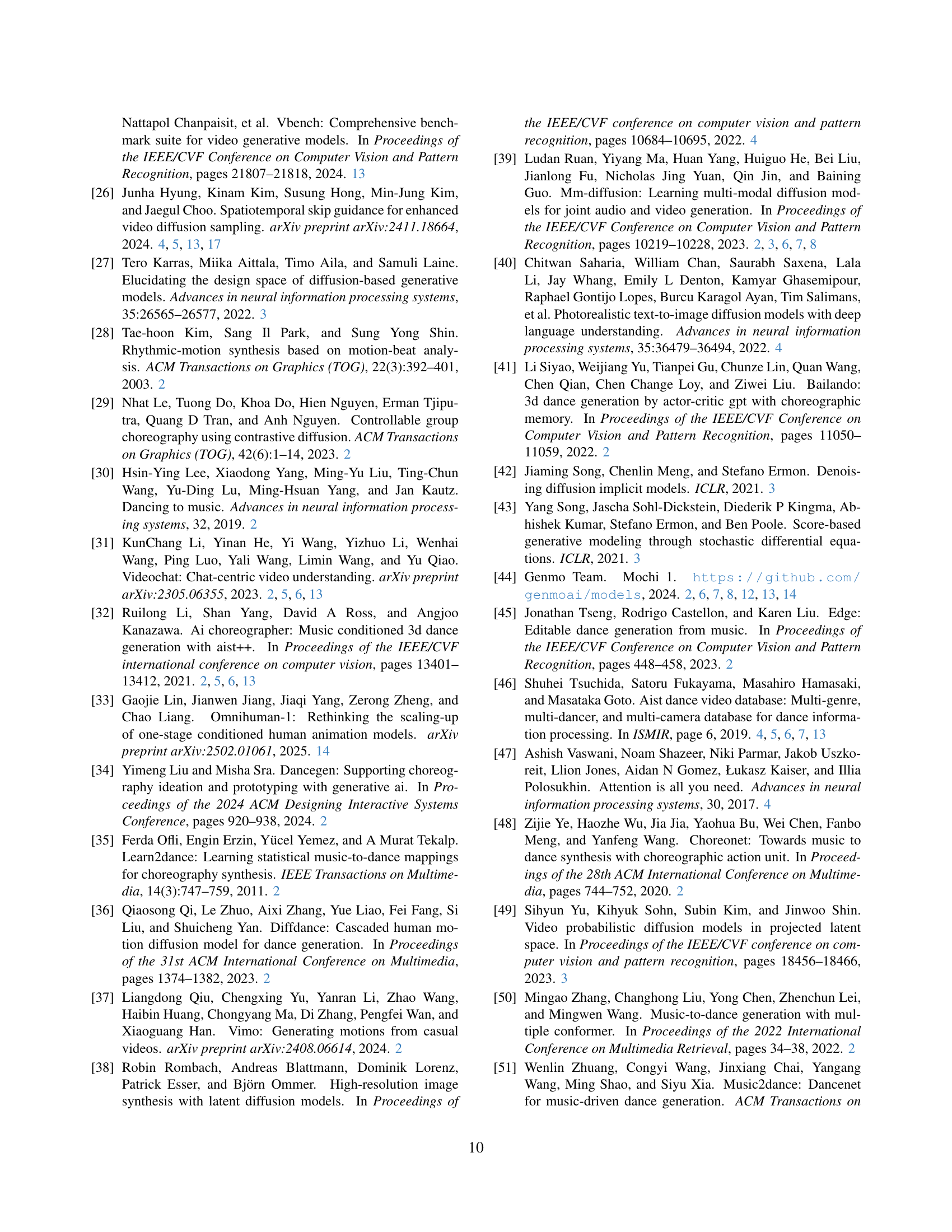

🔼 This figure shows a set of curves representing beta distributions with varying parameters. The x-axis represents the values of the beta distribution, and the y-axis shows the probability density. Each curve corresponds to a different beta distribution, with the parameter β changing from 3.0 to 1.0 in increments. The curves illustrate how the shape of the beta distribution changes with the parameter β, going from a distribution concentrated near 0 to a uniform distribution as β approaches 1. This visualization helps to understand the Beta-Uniform scheduling strategy used in the MusicInfuser model, where the noise distribution is gradually transitioned from a Beta distribution to a uniform distribution during the training process.

read the caption

Figure 9: Beta distributions.

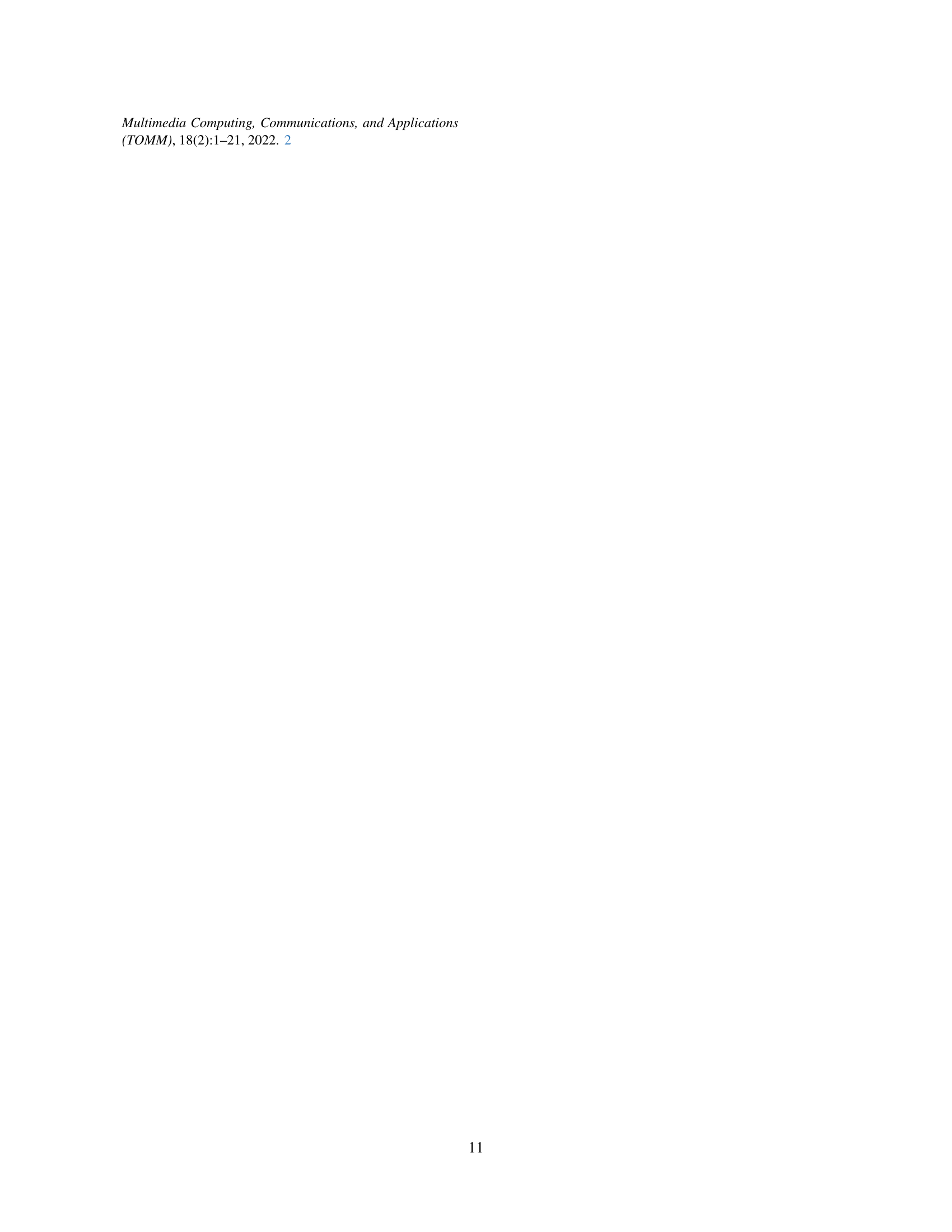

🔼 This figure demonstrates how the model’s generated choreography changes in complexity based on the prompt used. The top row showcases basic dance movements generated with a simple prompt. The middle row shows increased complexity with a more specific style and setting. The bottom row displays the most complex choreography, generated by a detailed and descriptive prompt. This illustrates the model’s ability to control the level of detail and sophistication in the generated dance sequences via textual prompts.

read the caption

Figure 10: Changes in the complexity of choreography.

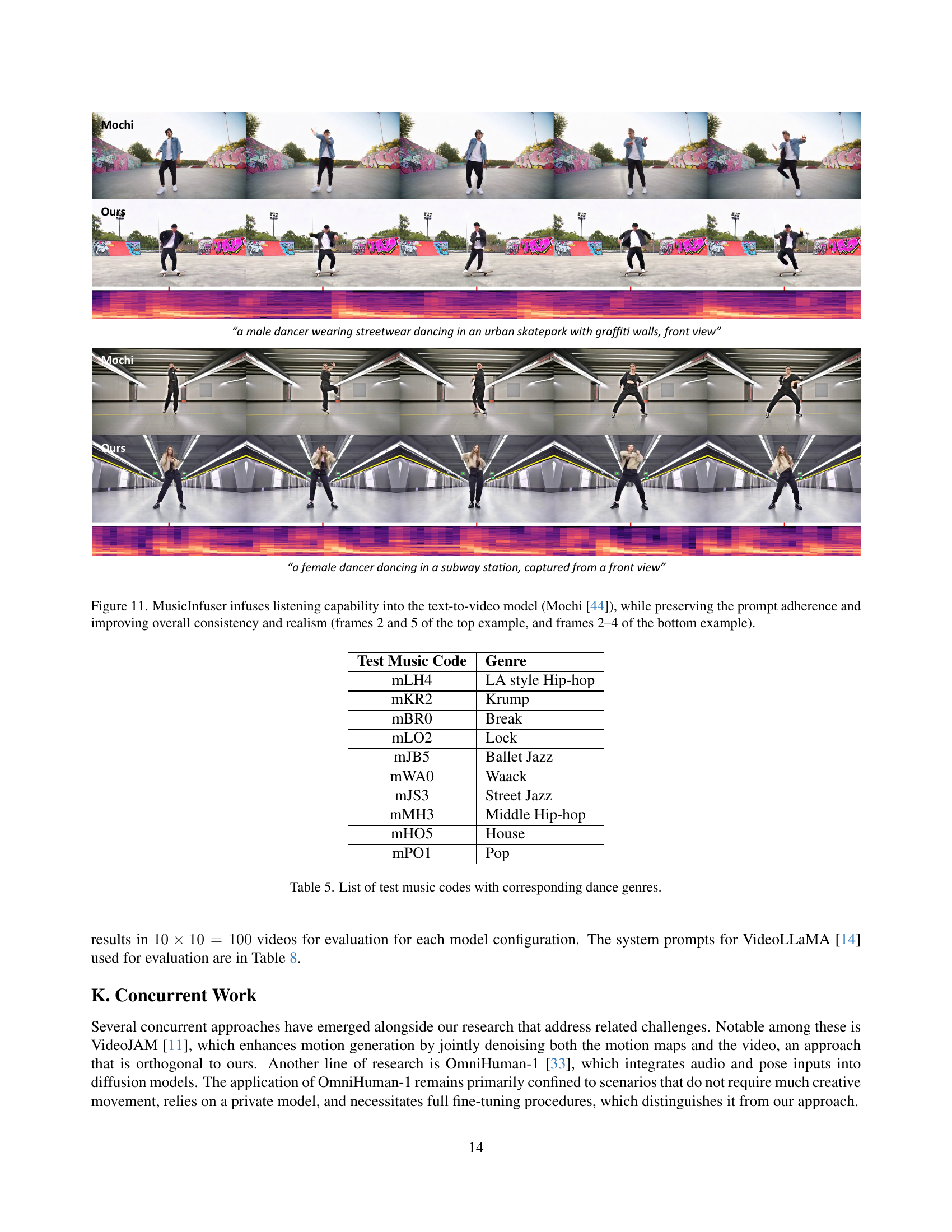

🔼 This figure compares the results of generating dance videos using two different methods: MusicInfuser and Mochi. MusicInfuser, the authors’ proposed method, uses the Mochi text-to-video model as a base but adds audio conditioning through their cross-attention mechanism. The figure showcases two examples where each method is prompted to generate a video of a dancer in a specific setting, based on the provided text. The comparisons in this figure highlight how MusicInfuser is able to generate videos that better adhere to the prompt and have higher levels of overall consistency and realism compared to the base Mochi model. Specifically, the authors point out that frames 2 and 5 in the top example, and frames 2-4 in the bottom example, most clearly illustrate this improvement in adherence and quality.

read the caption

Figure 11: MusicInfuser infuses listening capability into the text-to-video model (Mochi [44]), while preserving the prompt adherence and improving overall consistency and realism (frames 2 and 5 of the top example, and frames 2–4 of the bottom example).

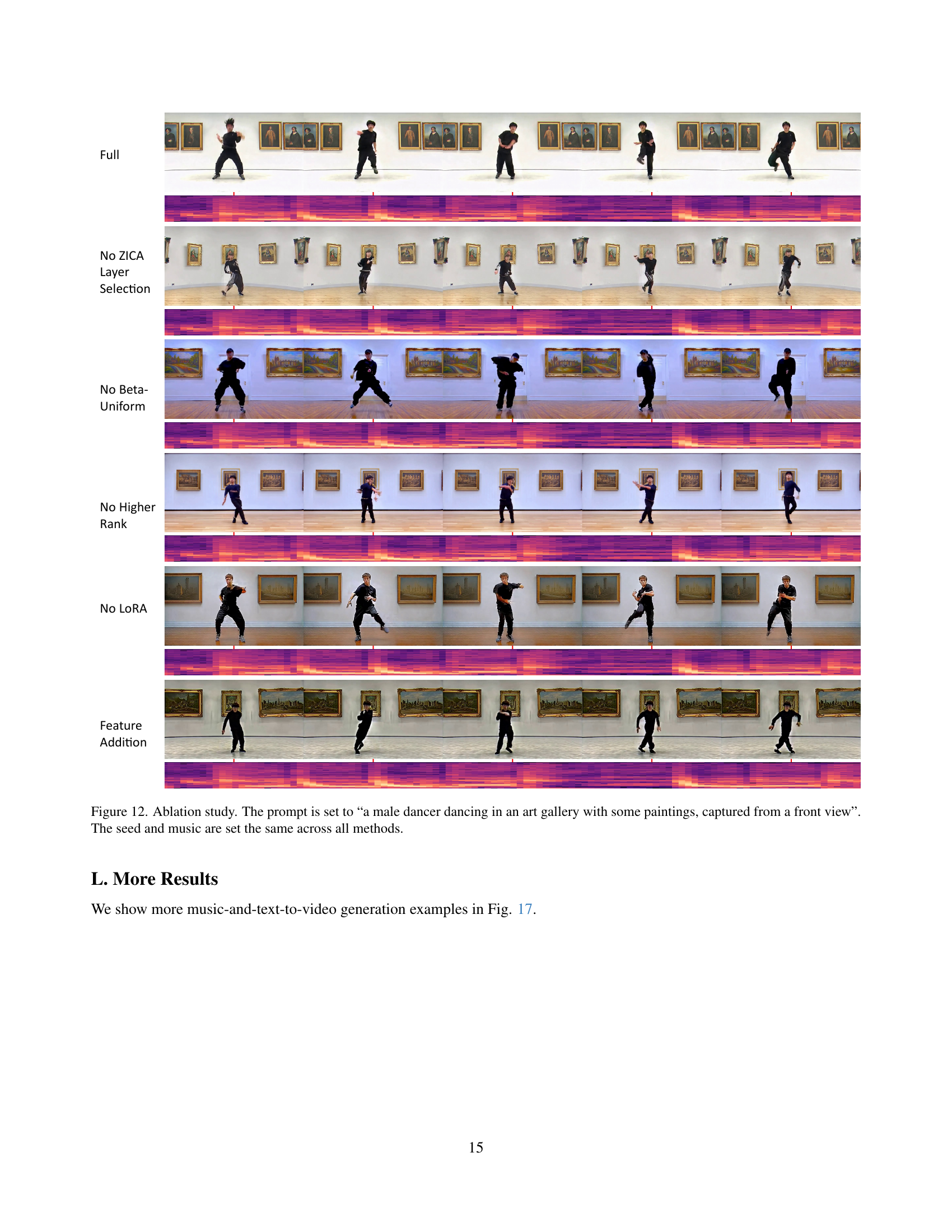

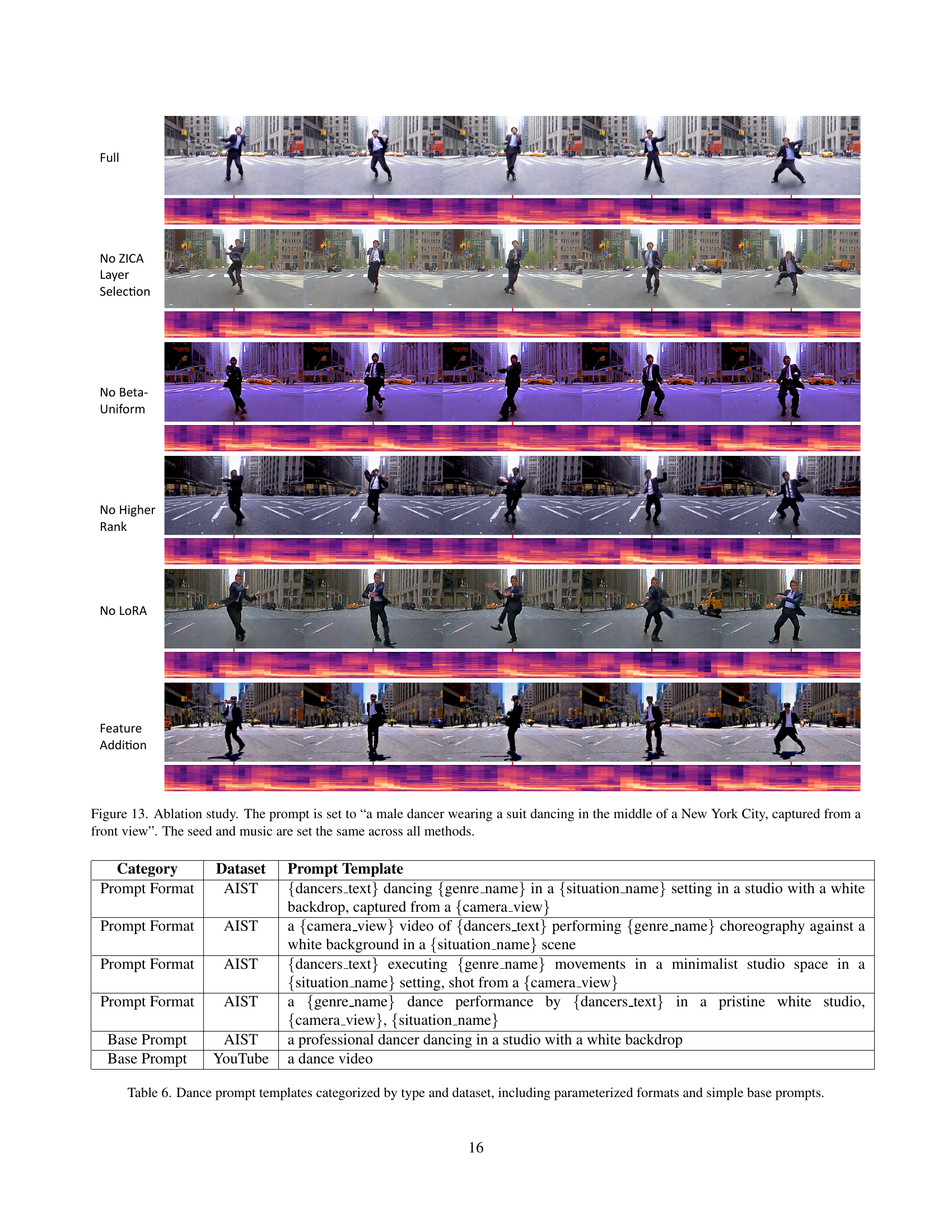

🔼 Figure 12 presents an ablation study comparing different model variations of MusicInfuser. All results use the same music track, random seed, and text prompt: ‘a male dancer dancing in an art gallery with some paintings, captured from a front view’. This allows a clear visual comparison of how each component (ZICA layer selection, Beta-Uniform scheduling, higher-rank LoRA, standard LoRA, and the addition of raw audio features) affects the generated dance video. Differences in dance quality, style adherence, and movement smoothness are easily observable.

read the caption

Figure 12: Ablation study. The prompt is set to “a male dancer dancing in an art gallery with some paintings, captured from a front view”. The seed and music are set the same across all methods.

🔼 This ablation study visualizes the impact of different components of the MusicInfuser model on dance video generation. The experiment uses a consistent prompt (‘a male dancer wearing a suit dancing in the middle of a New York City, captured from a front view’), music track, and random seed across all model variations. Each row shows the results for a specific model variant: the full MusicInfuser model, a model without the zero-initialized cross-attention layer selection, a model without the beta-uniform scheduling, a model without higher-rank LoRA, a model without LoRA, and a model using feature addition instead of the ZICA adapter. The generated video sequences allow for a visual comparison of how each model component affects the final dance generated.

read the caption

Figure 13: Ablation study. The prompt is set to “a male dancer wearing a suit dancing in the middle of a New York City, captured from a front view”. The seed and music are set the same across all methods.

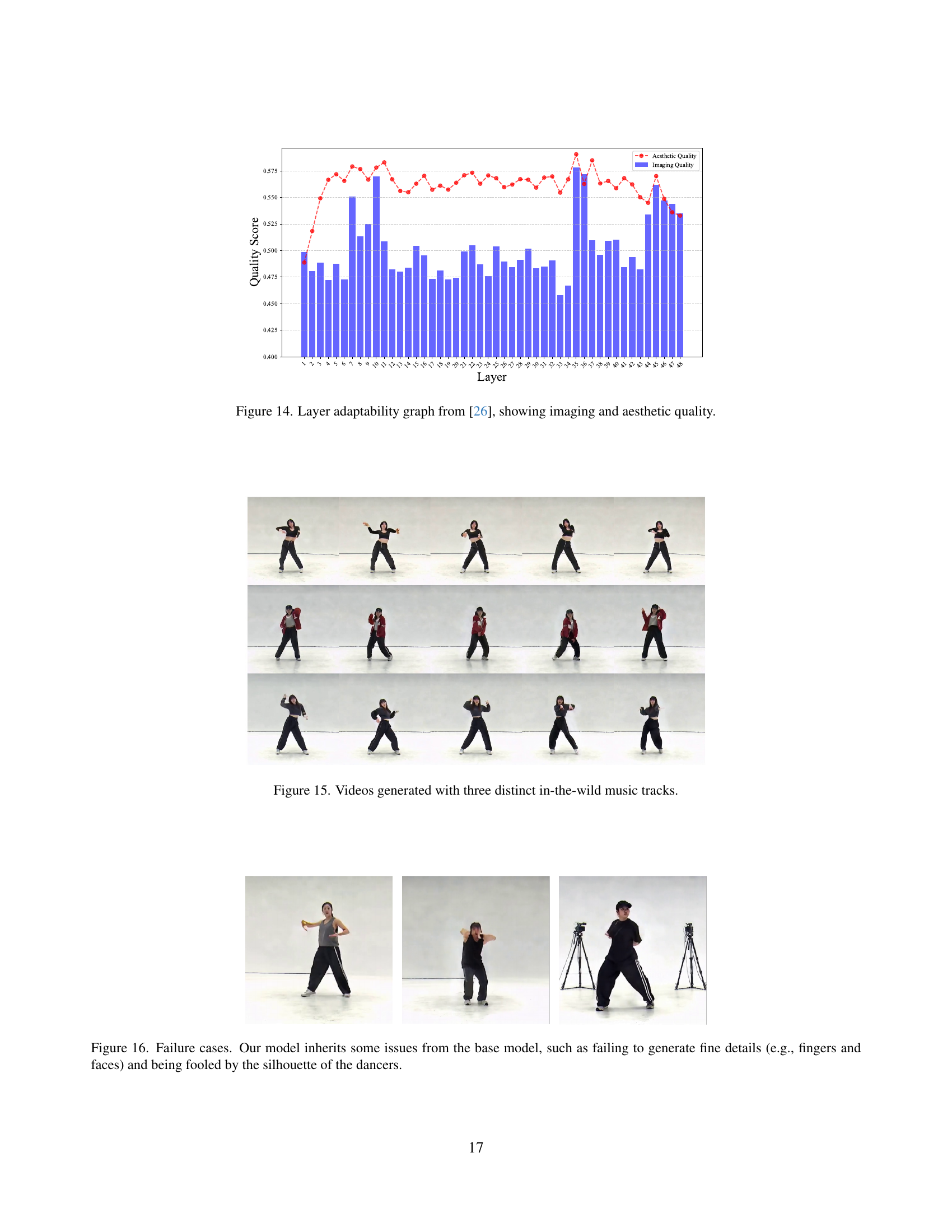

🔼 This figure displays a graph showing the layer adaptability results from the paper [26]. It specifically illustrates how the imaging and aesthetic quality change across different layers of the model. This information is crucial for determining the optimal layer selection strategy within a video generation model.

read the caption

Figure 14: Layer adaptability graph from [26], showing imaging and aesthetic quality.

🔼 This figure showcases three example videos generated by the MusicInfuser model, each synchronized to a different music track sourced from the internet. This demonstrates the model’s capability to generalize to unseen music styles and maintain high-quality dance generation.

read the caption

Figure 15: Videos generated with three distinct in-the-wild music tracks.

🔼 Figure 16 shows examples where the MusicInfuser model fails to generate high-fidelity details, such as fingers and facial features. These failures are inherited from limitations in the underlying base model. Additionally, the model demonstrates a susceptibility to errors caused by focusing primarily on the silhouette of the dancers rather than precise details of their pose and movement. In essence, the model struggles with generating fine-grained details and can be misled by overall body shape.

read the caption

Figure 16: Failure cases. Our model inherits some issues from the base model, such as failing to generate fine details (e.g., fingers and faces) and being fooled by the silhouette of the dancers.

More on tables

| Model | Modality | Imaging | Aesthetic | Overall | Video Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | Quality | Consistency | Average | ||

| AIST Dataset (GT) [46] | A+V | 9.76 | 8.17 | 9.77 | 9.23 |

| MM-Diffusion [39] | A+V | 8.94 | 6.52 | 8.38 | 7.94 |

| Mochi [44] | T+V | 9.46 | 7.90 | 8.98 | 8.78 |

| MusicInfuser (Ours) | T+A+V | 9.60 | 7.87 | 9.39 | 8.95 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of video quality across four different models: the ground truth (GT) from the AIST dataset, MM-Diffusion, Mochi, and the proposed MusicInfuser method. The metrics used to evaluate video quality are: imaging quality, aesthetic quality, overall consistency, and average video quality. The AIST dataset ground truth provides a baseline for comparison. For models that utilize text input (Mochi and MusicInfuser), the scores represent an average derived from a standardized set of prompts, ensuring fair comparison.

read the caption

Table 2: Video quality metrics comparing different models. For the models that have text input modality, we report an average of scores using a predefined benchmark of prompts.

| Model | Style | Creative | Overall | Prompt Align |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capture | Interpretation | Satisfaction | Average | |

| Mochi [44] | 7.98 | 9.04 | 9.55 | 8.86 |

| MusicInfuser (Ours) | 7.80 | 9.27 | 9.80 | 8.96 |

| No in-the-Wild Data | 6.80 | 8.69 | 8.40 | 7.96 |

| Base Prompt 0% | 7.45 | 8.85 | 9.43 | 8.58 |

| Base Prompt 100% | 7.33 | 9.06 | 9.36 | 8.58 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the prompt alignment capabilities of different models, including MusicInfuser, Mochi, and a baseline with no in-the-wild data. The metrics assess how well the generated videos align with various aspects of the prompts, such as style capture, creative interpretation, and overall satisfaction. It helps demonstrate MusicInfuser’s effectiveness at generating videos that accurately reflect user-specified parameters.

read the caption

Table 3: Prompt alignment metrics comparing different models.

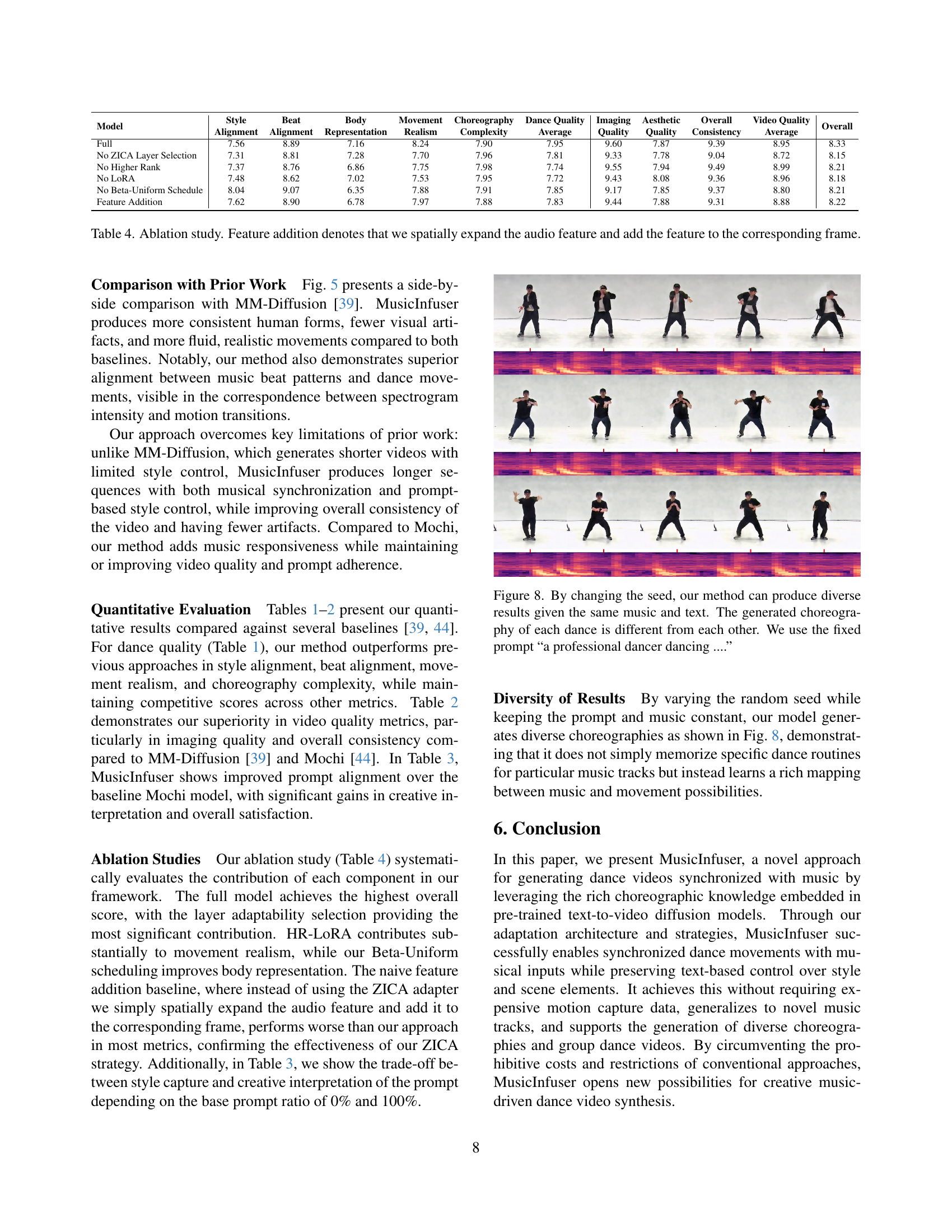

| Model | Style | Beat | Body | Movement | Choreography | Dance Quality | Imaging | Aesthetic | Overall | Video Quality | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment | Alignment | Representation | Realism | Complexity | Average | Quality | Quality | Consistency | Average | ||

| Full | 7.56 | 8.89 | 7.16 | 8.24 | 7.90 | 7.95 | 9.60 | 7.87 | 9.39 | 8.95 | 8.33 |

| No ZICA Layer Selection | 7.31 | 8.81 | 7.28 | 7.70 | 7.96 | 7.81 | 9.33 | 7.78 | 9.04 | 8.72 | 8.15 |

| No Higher Rank | 7.37 | 8.76 | 6.86 | 7.75 | 7.98 | 7.74 | 9.55 | 7.94 | 9.49 | 8.99 | 8.21 |

| No LoRA | 7.48 | 8.62 | 7.02 | 7.53 | 7.95 | 7.72 | 9.43 | 8.08 | 9.36 | 8.96 | 8.18 |

| No Beta-Uniform Schedule | 8.04 | 9.07 | 6.35 | 7.88 | 7.91 | 7.85 | 9.17 | 7.85 | 9.37 | 8.80 | 8.21 |

| Feature Addition | 7.62 | 8.90 | 6.78 | 7.97 | 7.88 | 7.83 | 9.44 | 7.88 | 9.31 | 8.88 | 8.22 |

🔼 This ablation study analyzes the individual contributions of different components within the MusicInfuser model. It shows the impact of removing the Zero-Initialized Cross-attention (ZICA) layer selection, the Beta-Uniform scheduling, the Higher Rank (HR-LORA) adapter, and the LORA adapter itself, as well as the impact of a naive ‘Feature Addition’ baseline. The ‘Feature Addition’ method simply expands the audio feature spatially and adds it directly to corresponding frames, lacking the more sophisticated integration methods used in the full MusicInfuser model. The results reveal the relative importance of each component in achieving the model’s performance in terms of style and beat alignment, body representation, movement realism, choreography complexity, and overall dance quality.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study. Feature addition denotes that we spatially expand the audio feature and add the feature to the corresponding frame.

| Test Music Code | Genre |

|---|---|

| mLH4 | LA style Hip-hop |

| mKR2 | Krump |

| mBR0 | Break |

| mLO2 | Lock |

| mJB5 | Ballet Jazz |

| mWA0 | Waack |

| mJS3 | Street Jazz |

| mMH3 | Middle Hip-hop |

| mHO5 | House |

| mPO1 | Pop |

🔼 This table lists the music tracks used for testing the MusicInfuser model. Each track is identified by a unique code and is categorized by its corresponding dance genre. This allows for evaluating the model’s performance across various dance styles and provides context for the generated dance videos.

read the caption

Table 5: List of test music codes with corresponding dance genres.

| Category | Dataset | Prompt Template |

|---|---|---|

| Prompt Format | AIST | {dancers_text} dancing {genre_name} in a {situation_name} setting in a studio with a white backdrop, captured from a {camera_view} |

| Prompt Format | AIST | a {camera_view} video of {dancers_text} performing {genre_name} choreography against a white background in a {situation_name} scene |

| Prompt Format | AIST | {dancers_text} executing {genre_name} movements in a minimalist studio space in a {situation_name} setting, shot from a {camera_view} |

| Prompt Format | AIST | a {genre_name} dance performance by {dancers_text} in a pristine white studio, {camera_view}, {situation_name} |

| Base Prompt | AIST | a professional dancer dancing in a studio with a white backdrop |

| Base Prompt | YouTube | a dance video |

🔼 This table presents various prompt templates used to generate dance videos. It categorizes the prompts by their format (parameterized or simple) and the dataset they are associated with (AIST or YouTube). The table provides examples of prompts for different categories such as dancers, dance genre, situation, and camera view, giving a comprehensive overview of the prompt variations used in the research.

read the caption

Table 6: Dance prompt templates categorized by type and dataset, including parameterized formats and simple base prompts.

| Prompts |

|---|

| a male dancer dancing on a rooftop at sunset, captured from a front view |

| a female dancer dancing in a subway station, captured from a front view |

| a male dancer dancing in an art gallery with some paintings, captured from a front view |

| a female dancer wearing a leather jacket dancing in a studio with a white backdrop, captured from a front view |

| a male dancer wearing a hoodie dancing in a studio with a white backdrop, captured from a front view |

| a female dancer wearing a denim vest dancing in a studio with a white backdrop, captured from a front view |

| a female dancer wearing a Hawaiian dress dancing on Waikiki Beach at sunset with Diamond Head in the background, captured from a front view |

| a male dancer wearing a suit dancing in the middle of a New York City, captured from a front view |

| a male dancer wearing a chef’s uniform dancing in a busy restaurant kitchen with flames from the grill behind him, captured from a front view |

| a female dancer wearing a Renaissance gown dancing in a Venetian masquerade ball with ornate chandeliers overhead, captured from a front view |

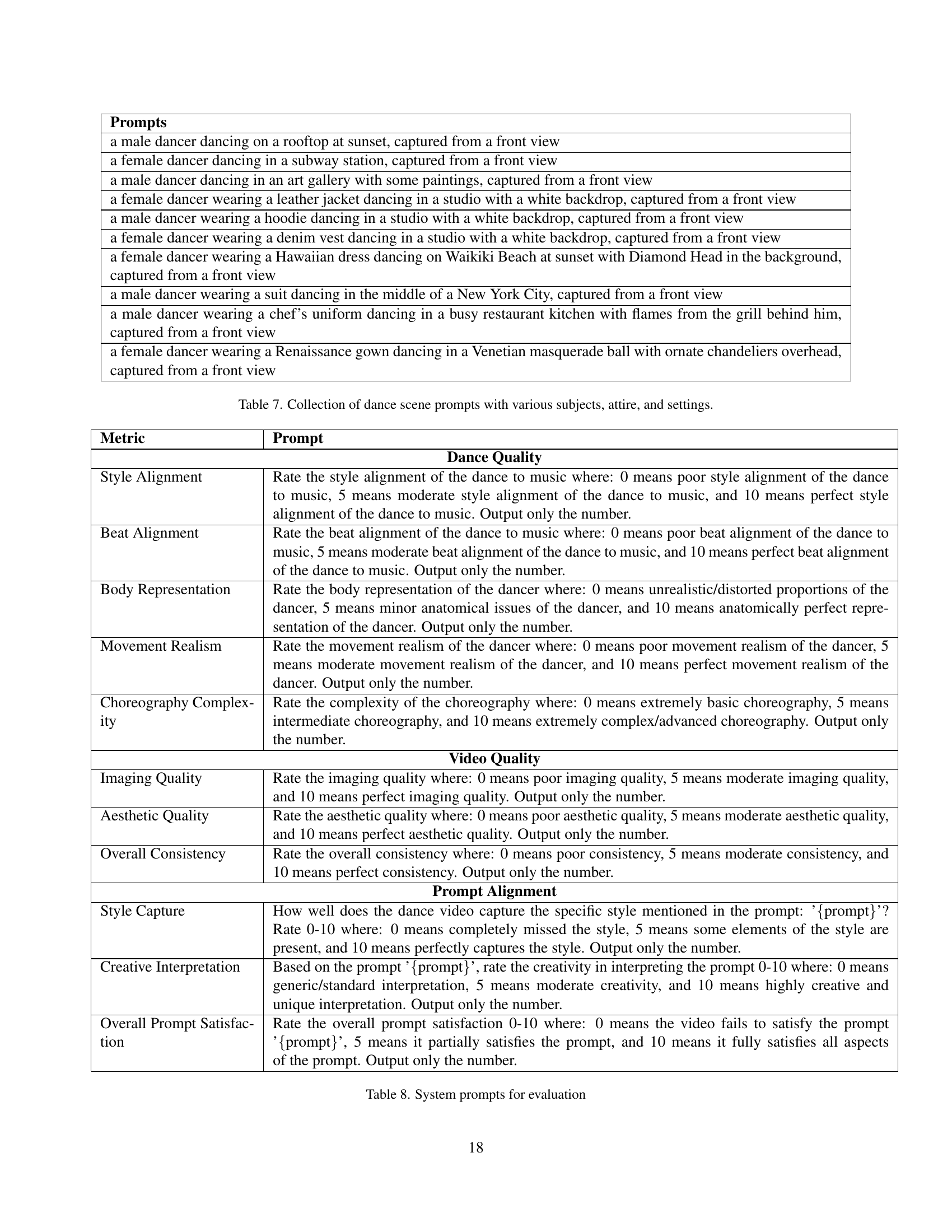

🔼 This table presents a collection of prompts used to generate dance videos. Each prompt describes a specific scenario, including the dancer’s attire, the setting, and the viewpoint. These prompts are used to evaluate the model’s ability to generate diverse and contextually relevant dance videos.

read the caption

Table 7: Collection of dance scene prompts with various subjects, attire, and settings.

| Metric | Prompt |

| Dance Quality | |

| Style Alignment | Rate the style alignment of the dance to music where: 0 means poor style alignment of the dance to music, 5 means moderate style alignment of the dance to music, and 10 means perfect style alignment of the dance to music. Output only the number. |

| Beat Alignment | Rate the beat alignment of the dance to music where: 0 means poor beat alignment of the dance to music, 5 means moderate beat alignment of the dance to music, and 10 means perfect beat alignment of the dance to music. Output only the number. |

| Body Representation | Rate the body representation of the dancer where: 0 means unrealistic/distorted proportions of the dancer, 5 means minor anatomical issues of the dancer, and 10 means anatomically perfect representation of the dancer. Output only the number. |

| Movement Realism | Rate the movement realism of the dancer where: 0 means poor movement realism of the dancer, 5 means moderate movement realism of the dancer, and 10 means perfect movement realism of the dancer. Output only the number. |

| Choreography Complexity | Rate the complexity of the choreography where: 0 means extremely basic choreography, 5 means intermediate choreography, and 10 means extremely complex/advanced choreography. Output only the number. |

| Video Quality | |

| Imaging Quality | Rate the imaging quality where: 0 means poor imaging quality, 5 means moderate imaging quality, and 10 means perfect imaging quality. Output only the number. |

| Aesthetic Quality | Rate the aesthetic quality where: 0 means poor aesthetic quality, 5 means moderate aesthetic quality, and 10 means perfect aesthetic quality. Output only the number. |

| Overall Consistency | Rate the overall consistency where: 0 means poor consistency, 5 means moderate consistency, and 10 means perfect consistency. Output only the number. |

| Prompt Alignment | |

| Style Capture | How well does the dance video capture the specific style mentioned in the prompt: ’{prompt}’? Rate 0-10 where: 0 means completely missed the style, 5 means some elements of the style are present, and 10 means perfectly captures the style. Output only the number. |

| Creative Interpretation | Based on the prompt ’{prompt}’, rate the creativity in interpreting the prompt 0-10 where: 0 means generic/standard interpretation, 5 means moderate creativity, and 10 means highly creative and unique interpretation. Output only the number. |

| Overall Prompt Satisfaction | Rate the overall prompt satisfaction 0-10 where: 0 means the video fails to satisfy the prompt ’{prompt}’, 5 means it partially satisfies the prompt, and 10 means it fully satisfies all aspects of the prompt. Output only the number. |

🔼 This table details the specific prompts used to evaluate the MusicInfuser model. It lists a series of prompts, each describing a different dance scene with variations in dancer attire, setting, and style. These prompts were used to generate dance videos and assess the model’s ability to generate videos that align with both the textual description and the musical input. The assessment metrics used are also listed and described, indicating how the quality of style, beat alignment, body representation, movement realism, choreography complexity, and overall video quality were evaluated.

read the caption

Table 8: System prompts for evaluation

Full paper#