TL;DR#

Foundation models have revolutionized text, image, and video processing, but 3D intelligence lags behind. At Roblox, the goal is to create a foundation model that empowers developers to generate 3D objects/scenes, rig characters, and produce object behavior scripts. This requires addressing challenges like limited 3D data, unbounded input/output sizes, and the need for multi-modal collaboration.

To tackle this, the paper introduces Cube, focusing on 3D shape tokenization. This converts shapes into discrete tokens, enabling applications like text-to-shape/scene generation and scene analysis. It uses techniques like phase-modulated positional encoding and a self-supervised loss to improve training and reconstruction quality, paving the way for a unified foundation model for 3D.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important for researchers because it presents a new approach to 3D shape tokenization, a key challenge in building foundation models for 3D intelligence. The proposed techniques offer a promising way to represent and generate 3D shapes, with potential applications in various fields.

Visual Insights#

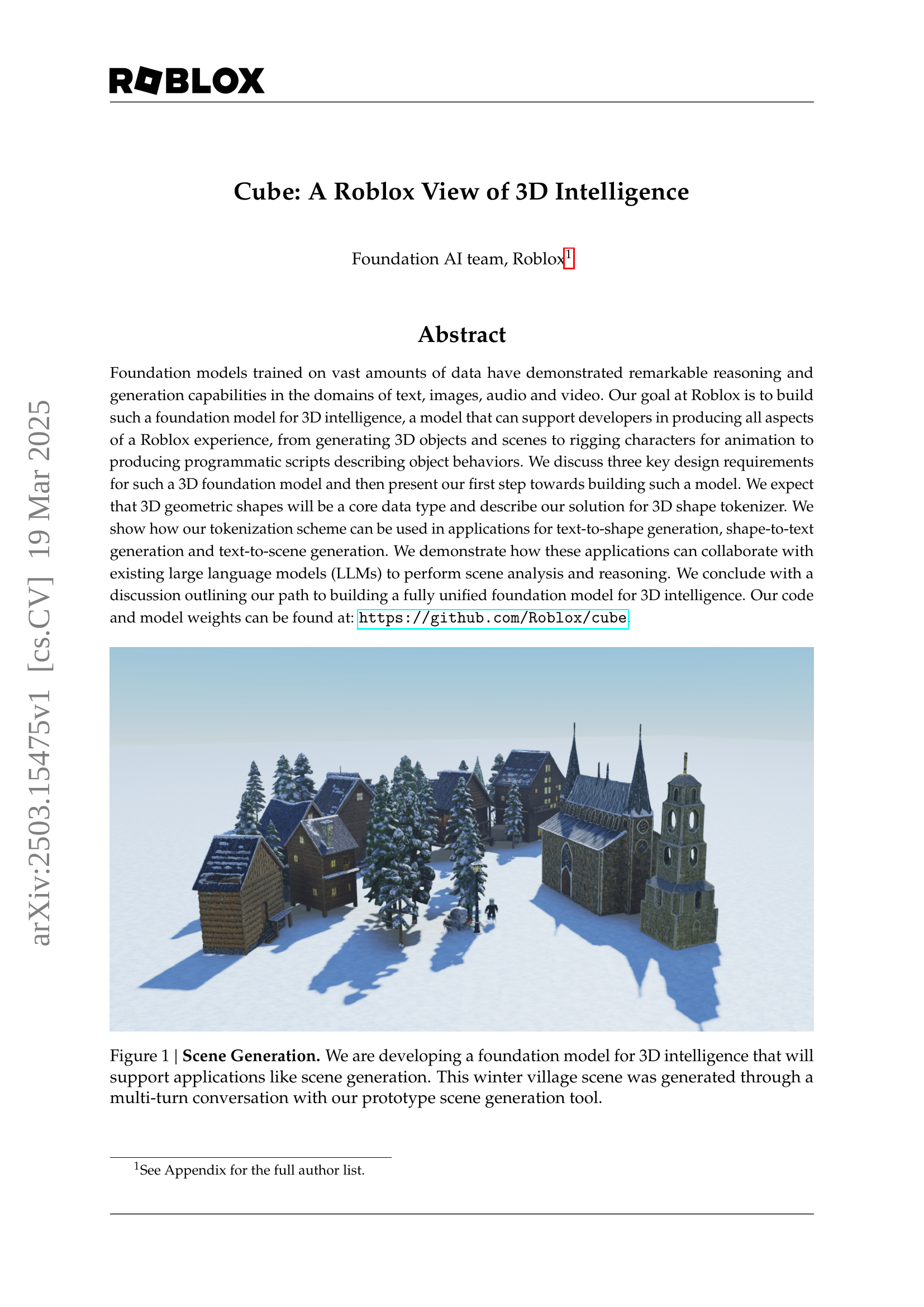

🔼 This figure showcases a winter village scene generated using a prototype 3D scene generation tool. The scene is used as an example to illustrate the capabilities of the foundation model for 3D intelligence being developed by Roblox. The model supports multi-turn conversations allowing users to iteratively refine generated scenes. This demonstrates the system’s potential for applications in virtual world creation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Scene Generation. We are developing a foundation model for 3D intelligence that will support applications like scene generation. This winter village scene was generated through a multi-turn conversation with our prototype scene generation tool.

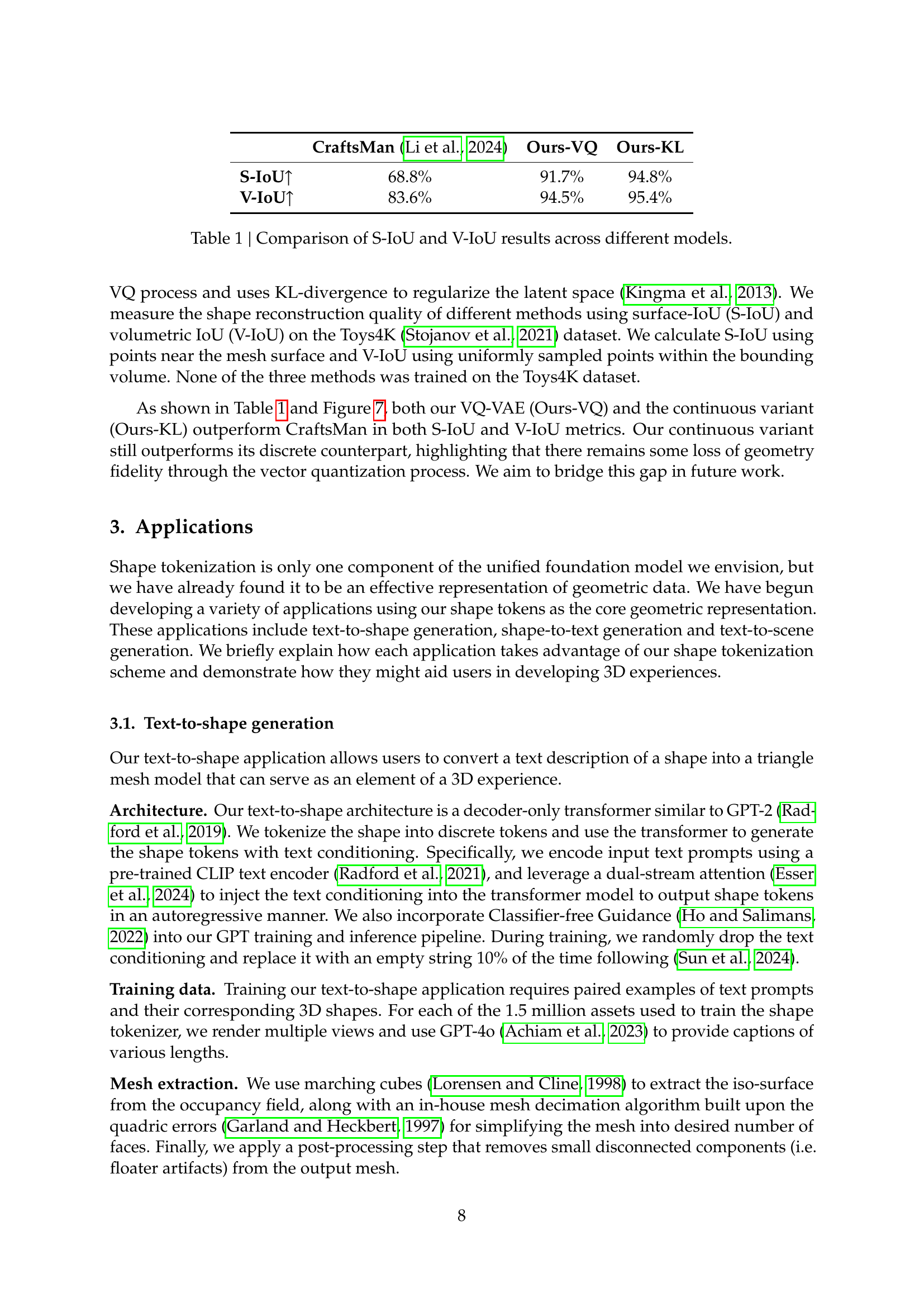

| CraftsMan (Li et al., 2024) | Ours-VQ | Ours-KL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-IoU | 68.8% | 91.7% | 94.8% |

| V-IoU | 83.6% | 94.5% | 95.4% |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of three different 3D shape reconstruction models: CraftsMan, Ours-VQ (our model with vector quantization), and Ours-KL (our continuous model). The models are evaluated using two metrics: surface IoU (S-IoU) and volumetric IoU (V-IoU), calculated on the Toys4K dataset. Higher values indicate better reconstruction quality. The results demonstrate that both our proposed models outperform Craftsman.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of S-IoU and V-IoU results across different models.

In-depth insights#

3D Tokenization#

3D Tokenization is a crucial step towards building foundation models for 3D intelligence. It involves converting 3D shapes into a discrete set of tokens. The process requires a representation that captures geometric properties, including smooth surfaces, sharp edges, and high-frequency details. This conversion enables the use of transformer-based architectures. A continuous shape representation, such as 3DShape2VecSet, is adapted into discrete tokens for native handling. Tokenization involves sampling points from the mesh surface, encoding them using positional encoding. A transformer encodes these points into continuous latent vectors. Optimal-transport vector quantization converts these vectors into discrete shape tokens, which can be decoded into an occupancy field for mesh extraction. Stochastic gradient shortcut and self-supervised latent space regularization address training challenges. It is an approach to improve the perceiver transformer’s ability to disambiguate spatially distinct points.

PMPE Encoding#

PMPE Encoding (Phase-Modulated Positional Encoding) enhances spatial awareness in transformers for 3D data. Traditional positional encoding struggles to differentiate distant points due to periodic variations, causing issues in cross-attention. PMPE addresses this by modulating phase offsets across sinusoidal functions, ensuring spatially distant points have distinct encodings. This improves reconstruction fidelity and reduces artifacts. The encoding function combines traditional positional encoding with a phase-modulated component, controlled by a hyperparameter to avoid resonance. PMPE uses the same frequency, but varies phase offset. Empirically, results indicate significantly improved reconstruction fidelity, particularly for complex geometric details. Additionally, PMPE minimizes artifacts like disconnected components, commonly seen with traditional positional encoding approaches. The ability is increased to preserve fine-grained shape information while enhancing distinction between spatial locations.

Self-Supervised#

Self-supervision is a powerful technique in machine learning that enables models to learn from unlabeled data, crucial when labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain. The core idea involves creating pseudo-labels from the data itself, guiding the model to learn meaningful representations. Contrastive learning, a common approach, trains models to distinguish between similar and dissimilar data points, improving feature extraction. In the context of 3D shape processing, self-supervision can involve tasks like predicting surface normals, completing partial shapes, or enforcing geometric consistency. By leveraging the inherent structure of 3D data, these techniques can significantly enhance the performance of downstream tasks such as shape reconstruction, completion, and generation. Careful design of the pretext task is essential to ensure that the learned representations capture relevant geometric and structural information, leading to more robust and generalizable models. Regularization is also key in preventing overfitting.

Text-to-Shape#

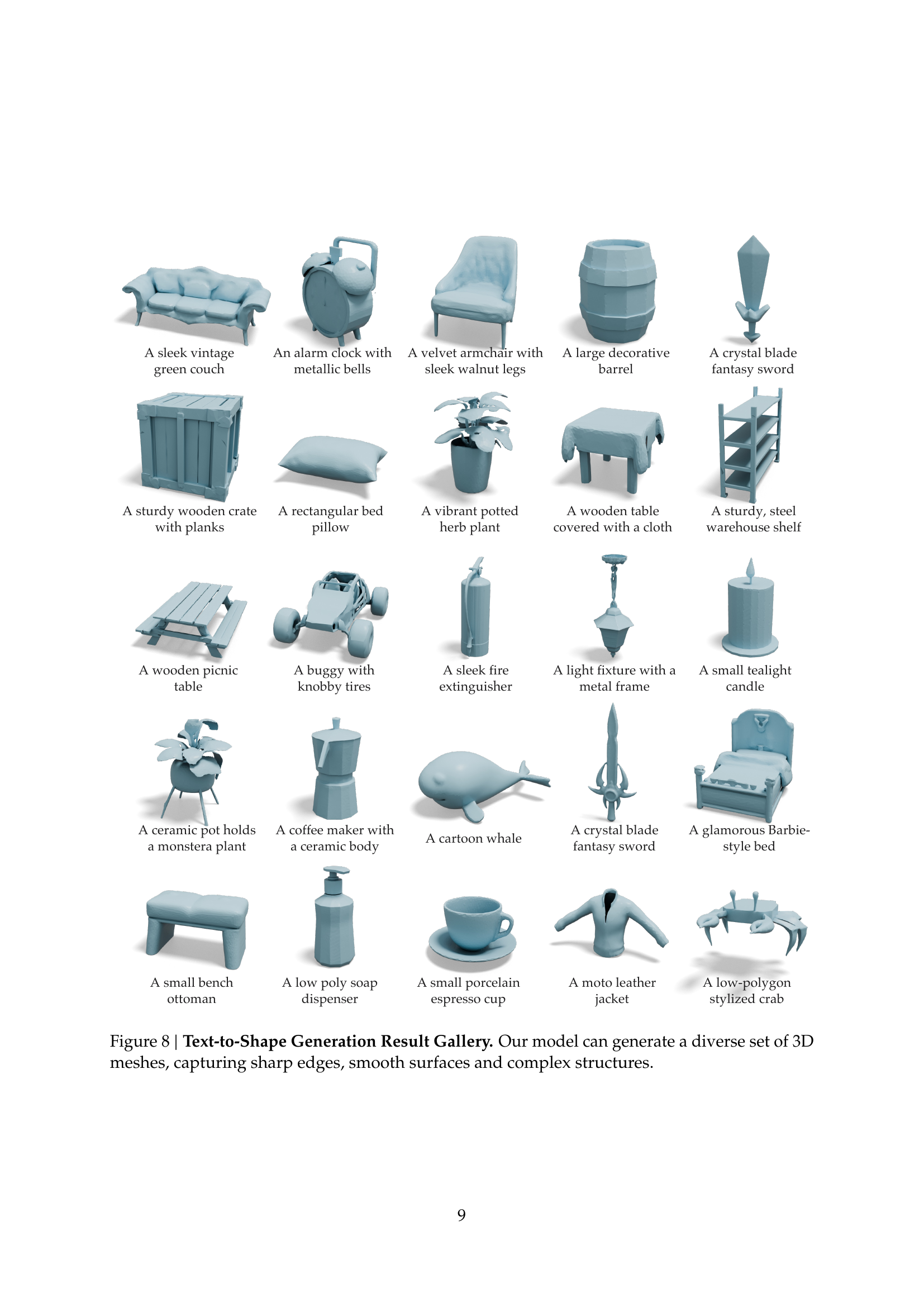

The ‘Text-to-Shape’ task, as highlighted in the research, involves converting textual descriptions into 3D models. This is a critical step towards bridging the gap between natural language understanding and 3D content creation. A key element to consider is the architecture; the paper highlights a decoder-only transformer similar to GPT-2 which has the discrete shape tokens and uses the transformer to generate the shape tokens with text conditioning. By leveraging a pre-trained CLIP text encoder with a dual-stream attention, the text conditioning is injected into the transformer model to output shape tokens in an autoregressive manner. Classifier-free Guidance is also incorporated to training and inference pipeline, helping to improve the diversity and quality of the generated shapes. Training the text-to-shape model requires paired examples of text prompts and corresponding 3D shapes to render multiple views of each of the assets in a dataset. The 3D shape extraction uses marching cubes to extract the iso-surface from the occupancy field, coupled with a mesh decimation algorithm and post-processing to improve geometry. The use of discrete shape tokens allows producing a diversity of 3D meshes with smooth surfaces and complex structures.

4D Behavior Gen#

4D behavior generation signifies a crucial frontier in creating more immersive and interactive virtual experiences, particularly within platforms like Roblox. It moves beyond static 3D models by incorporating dynamic elements like animation and scripted interactions based on player actions. An AI-based behavior generator would need to produce ‘riggable geometry,’ including detailed head meshes, bodies, and clothing that respond realistically. This entails creating objects that react contextually; a steering wheel turns the car wheels, or a door opens when a player approaches. It moves from pre-defined to generative. Such systems need to understand physical constraints, game logic, and player intent. Current 4D behavior design requires a deep understanding of physics, animation principles, and coding. An AI model needs to incorporate all of these skills. If combined with LLMs, this could provide an avenue for rapid iteration and prototyping of game mechanics, potentially revolutionizing content creation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

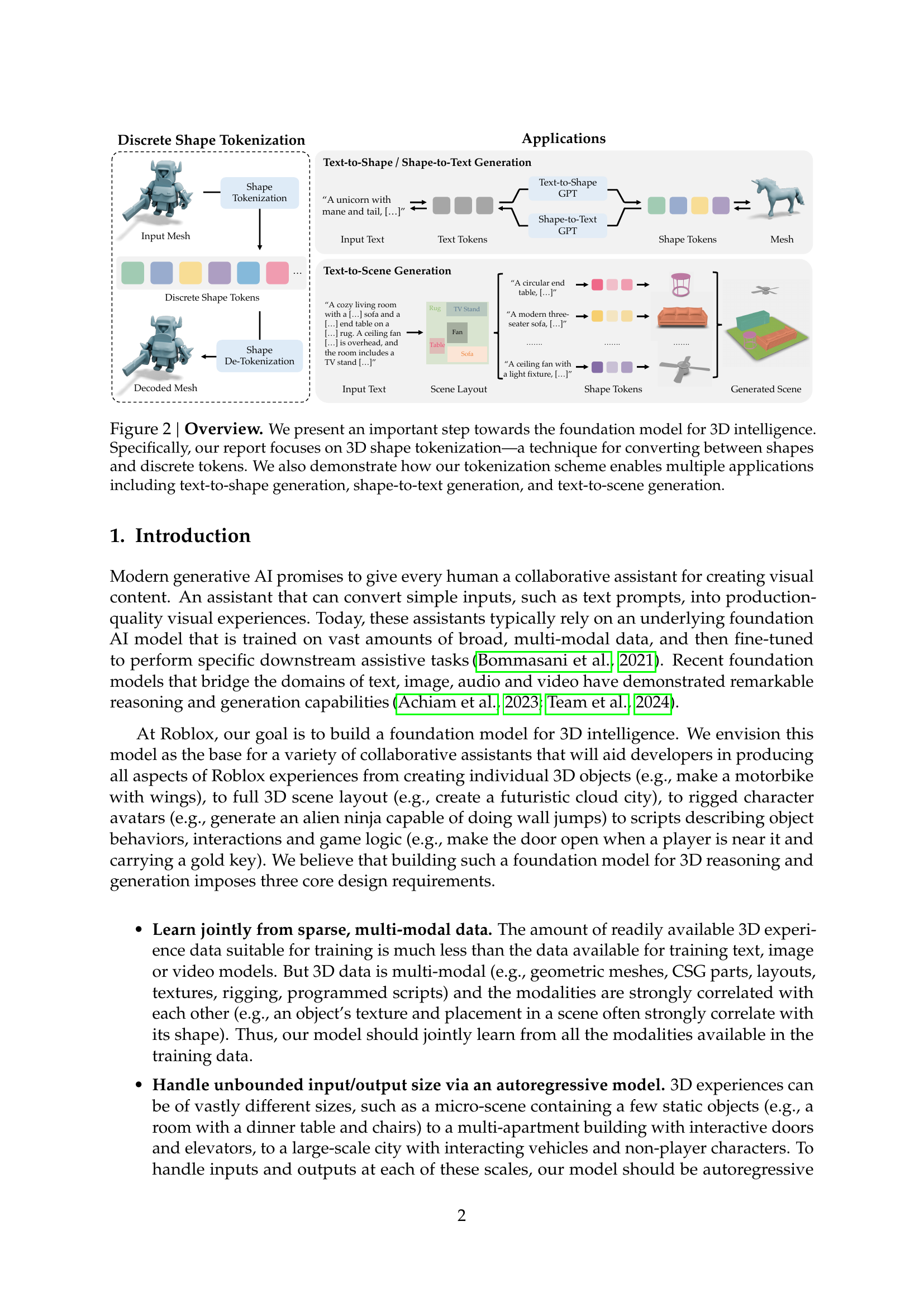

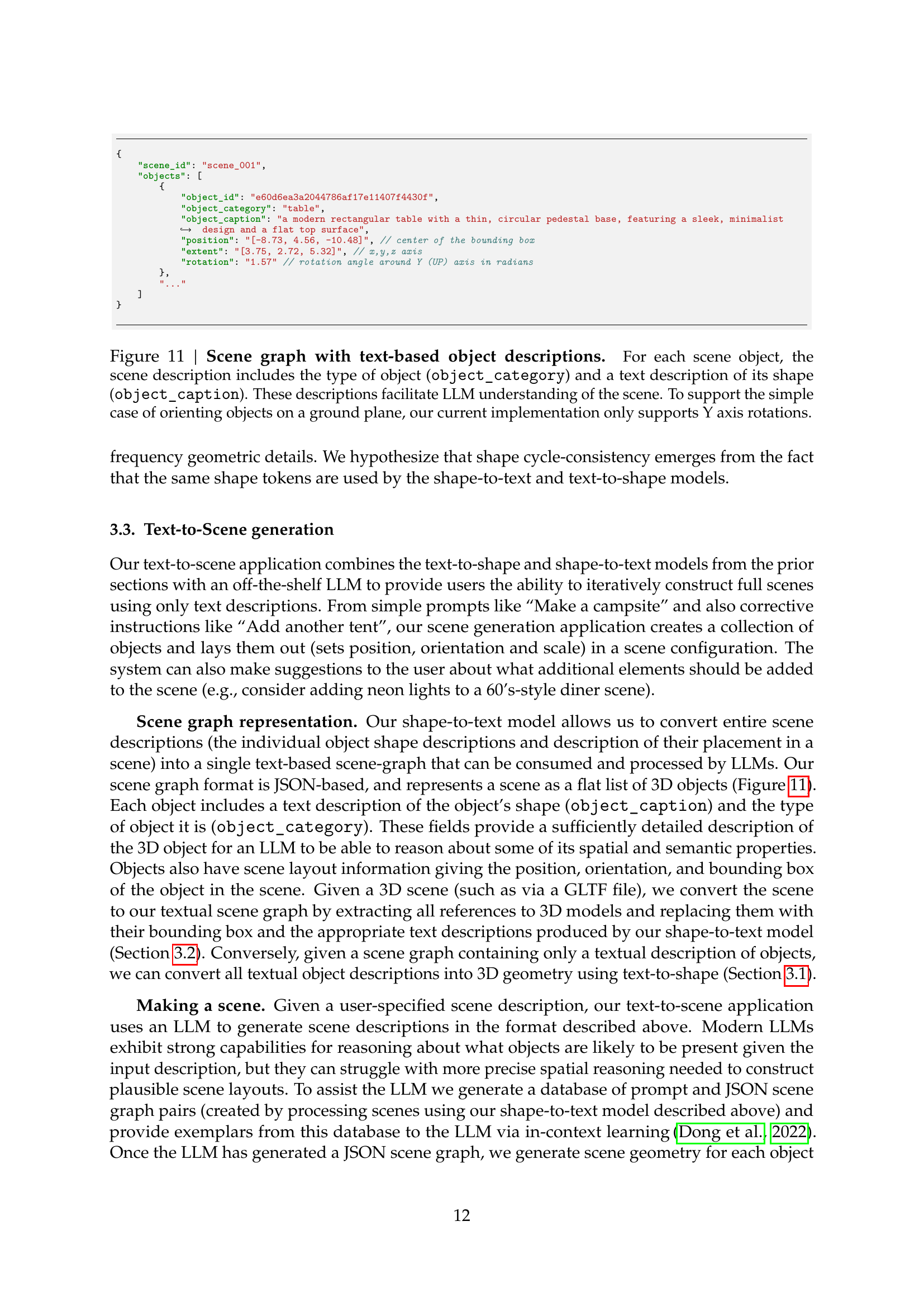

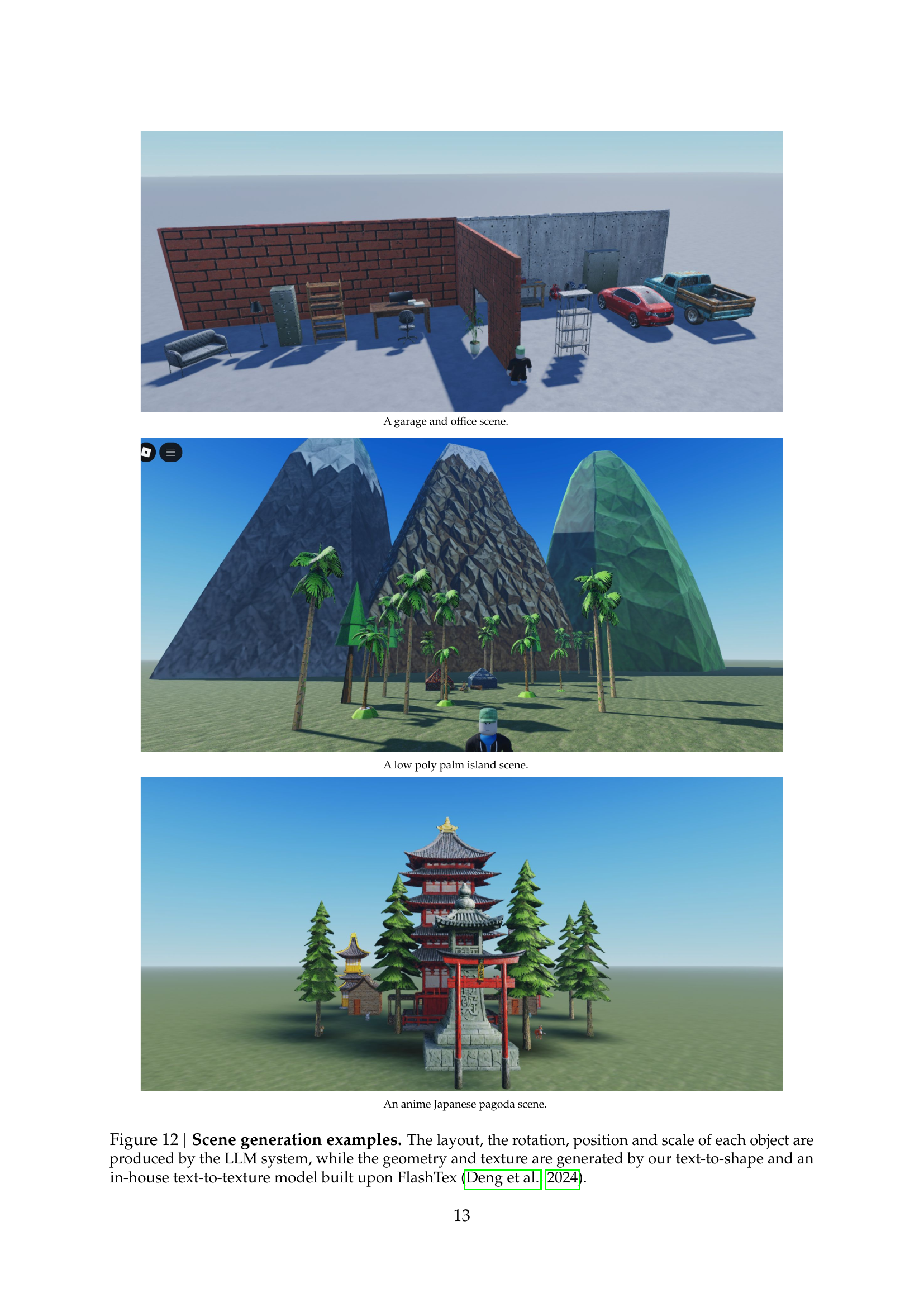

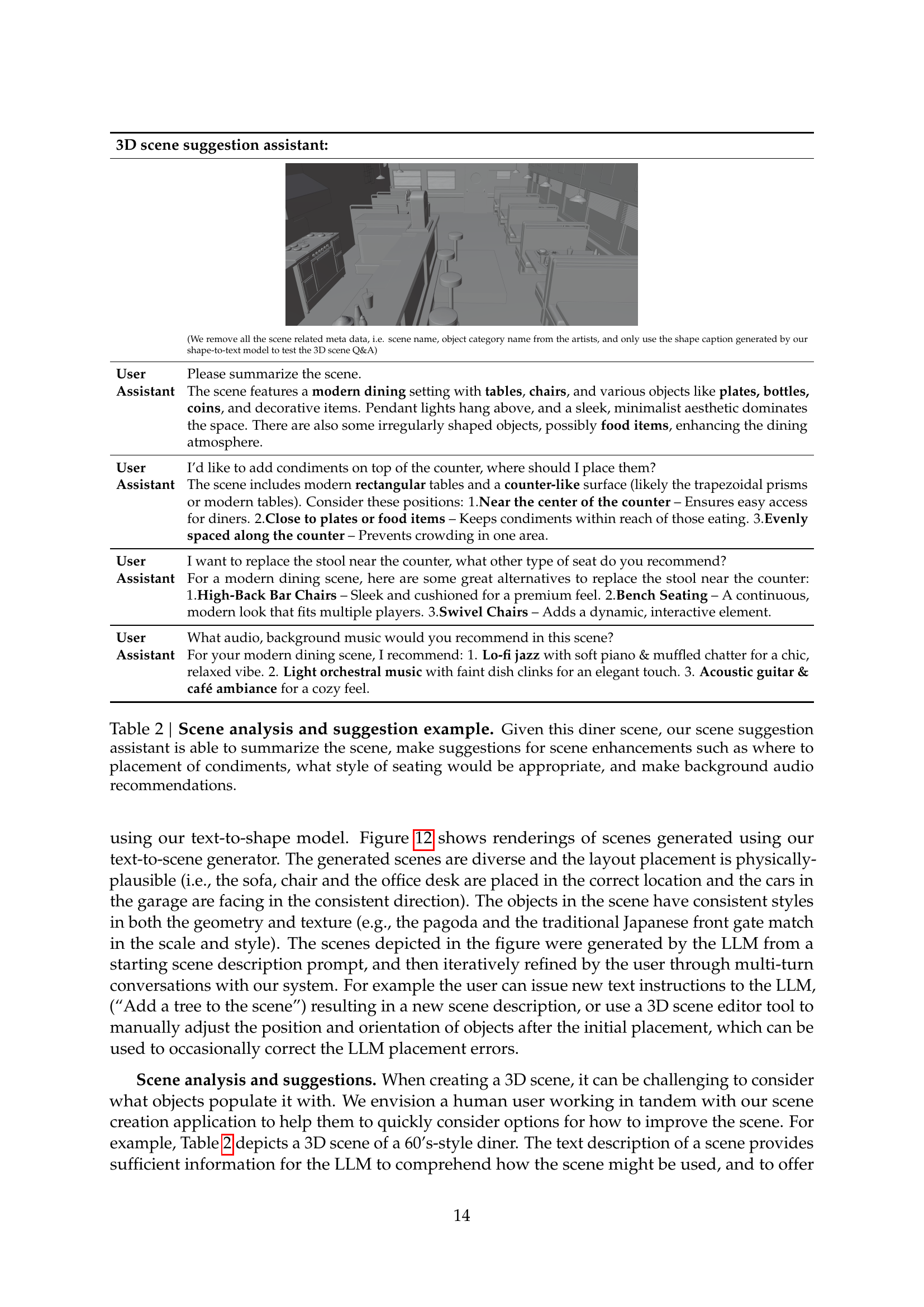

🔼 This figure illustrates the key steps in the development of a foundation model for 3D intelligence at Roblox. The central concept is 3D shape tokenization, a method for converting 3D shapes into discrete tokens, similar to how words are tokenized in natural language processing. This tokenization process is shown to enable three core applications: text-to-shape generation (creating 3D shapes from text descriptions), shape-to-text generation (generating text descriptions from 3D shapes), and text-to-scene generation (building entire 3D scenes from textual descriptions). The figure visually depicts the workflow of each application, highlighting how the discrete shape tokens serve as a common intermediary.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview. We present an important step towards the foundation model for 3D intelligence. Specifically, our report focuses on 3D shape tokenization—a technique for converting between shapes and discrete tokens. We also demonstrate how our tokenization scheme enables multiple applications including text-to-shape generation, shape-to-text generation, and text-to-scene generation.

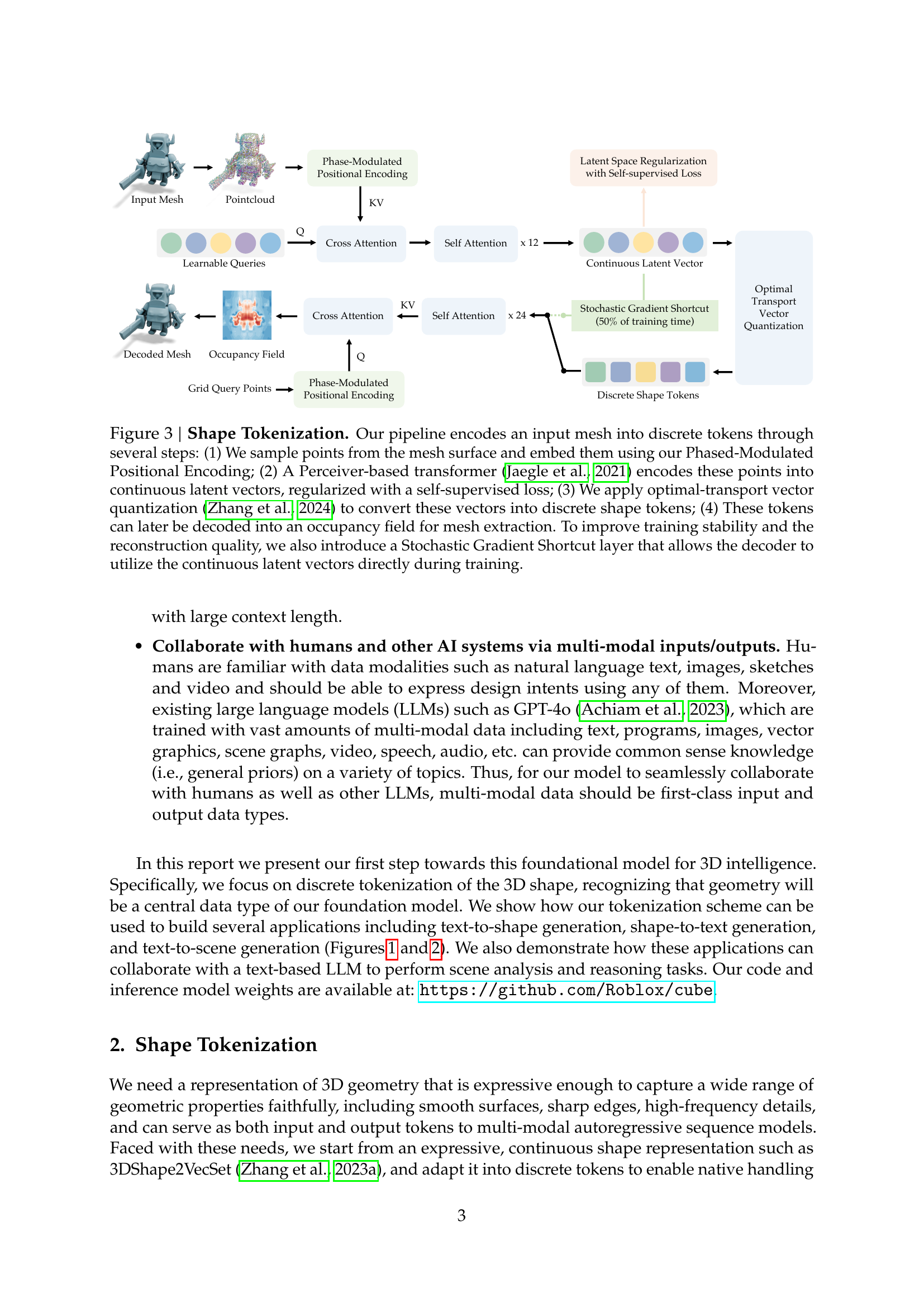

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the process of shape tokenization, a crucial step in converting 3D shapes into a format suitable for processing by a transformer-based neural network. The process begins by sampling points from the surface of a 3D mesh. These points are then encoded using a custom ‘Phased-Modulated Positional Encoding’ technique designed to preserve spatial relationships between points. Next, a Perceiver transformer processes these encoded points, transforming them into continuous latent vectors. A self-supervised loss function is applied to regularize the latent space, leading to more robust and stable training. The continuous latent vectors are subsequently converted to discrete shape tokens via optimal transport vector quantization. Finally, these discrete tokens can be decoded back into an occupancy field, which can then be used to reconstruct the original 3D mesh. A ‘Stochastic Gradient Shortcut’ is incorporated to enhance training stability and reconstruction quality by enabling the decoder to directly use the continuous latent vectors during training.

read the caption

Figure 3: Shape Tokenization. Our pipeline encodes an input mesh into discrete tokens through several steps: (1) We sample points from the mesh surface and embed them using our Phased-Modulated Positional Encoding; (2) A Perceiver-based transformer (Jaegle et al., 2021) encodes these points into continuous latent vectors, regularized with a self-supervised loss; (3) We apply optimal-transport vector quantization (Zhang et al., 2024) to convert these vectors into discrete shape tokens; (4) These tokens can later be decoded into an occupancy field for mesh extraction. To improve training stability and the reconstruction quality, we also introduce a Stochastic Gradient Shortcut layer that allows the decoder to utilize the continuous latent vectors directly during training.

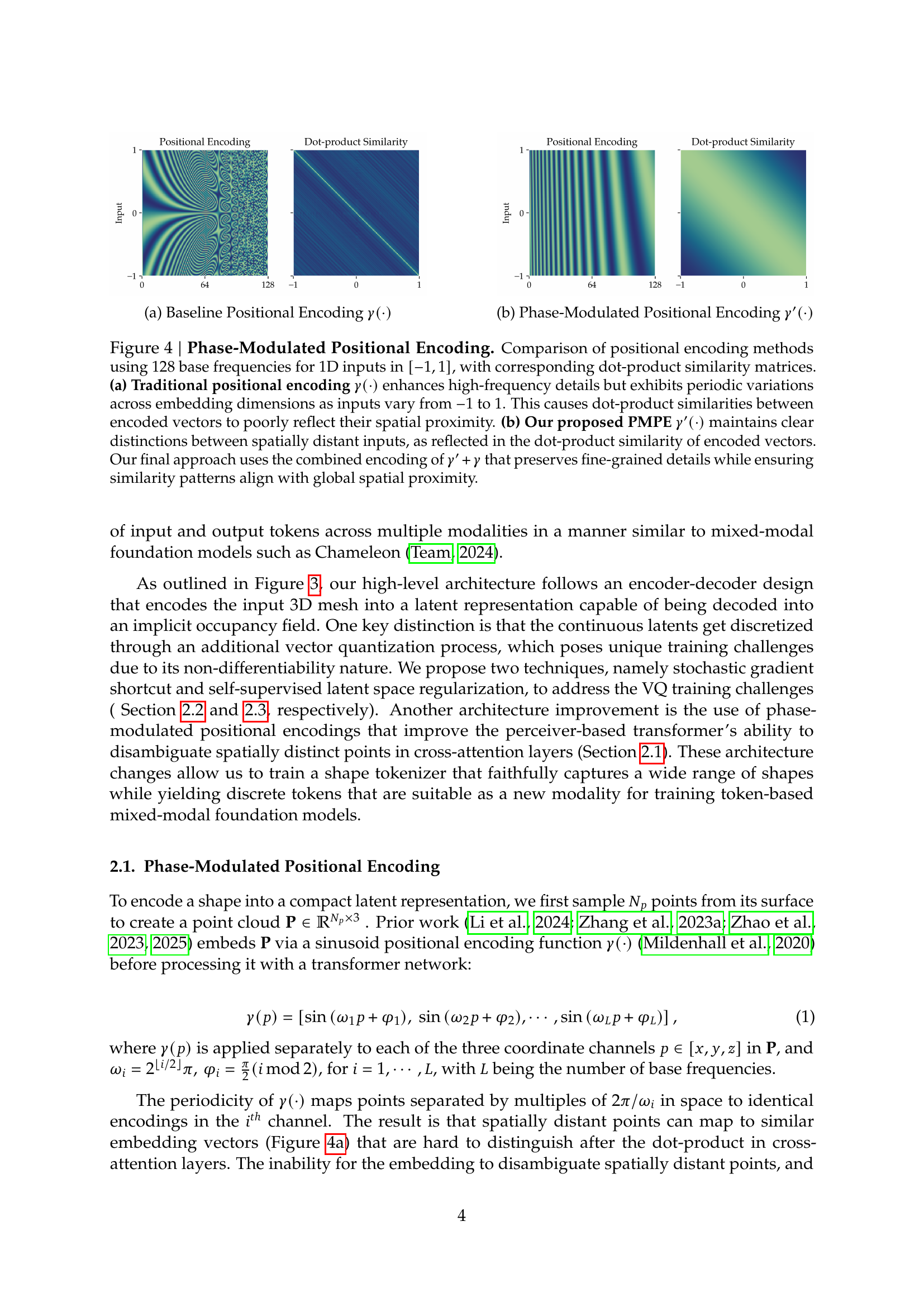

🔼 The figure shows a comparison of traditional positional encoding with the proposed Phase-Modulated Positional Encoding (PMPE). Traditional positional encoding, shown in (a), uses sinusoidal functions to encode the position of input points but creates periodic variations across embedding dimensions, causing dot-product similarity to not reflect actual spatial proximity well. PMPE (b), in contrast, produces an encoding that clearly distinguishes between spatially distinct points via phase modulation, resulting in improved spatial proximity representation.

read the caption

(a) Baseline Positional Encoding γ(⋅)𝛾⋅\gamma(\cdot)italic_γ ( ⋅ )

🔼 The figure shows a comparison between traditional positional encoding and the proposed phase-modulated positional encoding (PMPE). Traditional positional encoding exhibits periodic variations across embedding dimensions, poorly reflecting spatial proximity. In contrast, PMPE maintains clear distinctions between spatially distant inputs, improving the transformer’s ability to disambiguate spatially distinct points.

read the caption

(b) Phase-Modulated Positional Encoding γ′(⋅)superscript𝛾′⋅\gamma^{\prime}(\cdot)italic_γ start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ′ end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ( ⋅ )

🔼 Figure 4 illustrates the comparison between two positional encoding methods for handling 1D inputs ranging from -1 to 1. The top panel (a) shows a traditional positional encoding where high-frequency details are enhanced, but periodic variations across embedding dimensions cause issues with accurately reflecting spatial proximity in dot-product similarity matrices. In contrast, the bottom panel (b) presents the proposed Phase-Modulated Positional Encoding (PMPE). PMPE effectively maintains clear distinctions between spatially distant inputs, resulting in a dot-product similarity that better aligns with true spatial relationships. The final method combines both encoding schemes to retain fine-grained details while ensuring spatial proximity.

read the caption

Figure 4: Phase-Modulated Positional Encoding. Comparison of positional encoding methods using 128 base frequencies for 1D inputs in [−1,1]11[-1,1][ - 1 , 1 ], with corresponding dot-product similarity matrices. (a) Traditional positional encoding γ(⋅)𝛾⋅\gamma(\cdot)italic_γ ( ⋅ ) enhances high-frequency details but exhibits periodic variations across embedding dimensions as inputs vary from −11-1- 1 to 1111. This causes dot-product similarities between encoded vectors to poorly reflect their spatial proximity. (b) Our proposed PMPE γ′(⋅)superscript𝛾′⋅\gamma^{\prime}(\cdot)italic_γ start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ′ end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ( ⋅ ) maintains clear distinctions between spatially distant inputs, as reflected in the dot-product similarity of encoded vectors. Our final approach uses the combined encoding of γ′+γsuperscript𝛾′𝛾\gamma^{\prime}+\gammaitalic_γ start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ′ end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT + italic_γ that preserves fine-grained details while ensuring similarity patterns align with global spatial proximity.

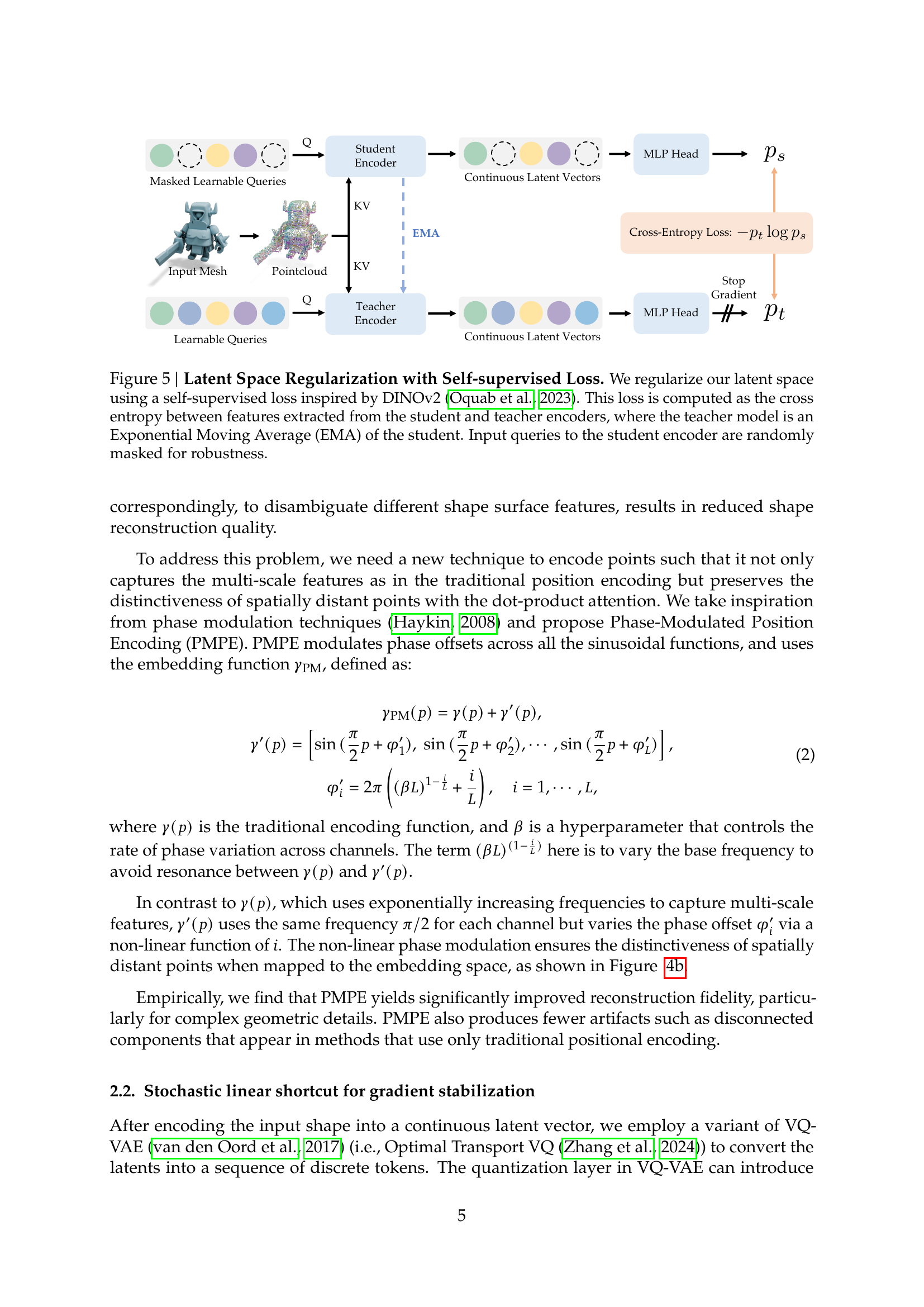

🔼 This figure illustrates the self-supervised learning method used to regularize the latent space of the shape tokenizer. A student encoder and a teacher encoder (an exponential moving average of the student) are employed. A cross-entropy loss is calculated between features extracted from both encoders. To enhance robustness, input queries to the student encoder are randomly masked.

read the caption

Figure 5: Latent Space Regularization with Self-supervised Loss. We regularize our latent space using a self-supervised loss inspired by DINOv2 (Oquab et al., 2023). This loss is computed as the cross entropy between features extracted from the student and teacher encoders, where the teacher model is an Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of the student. Input queries to the student encoder are randomly masked for robustness.

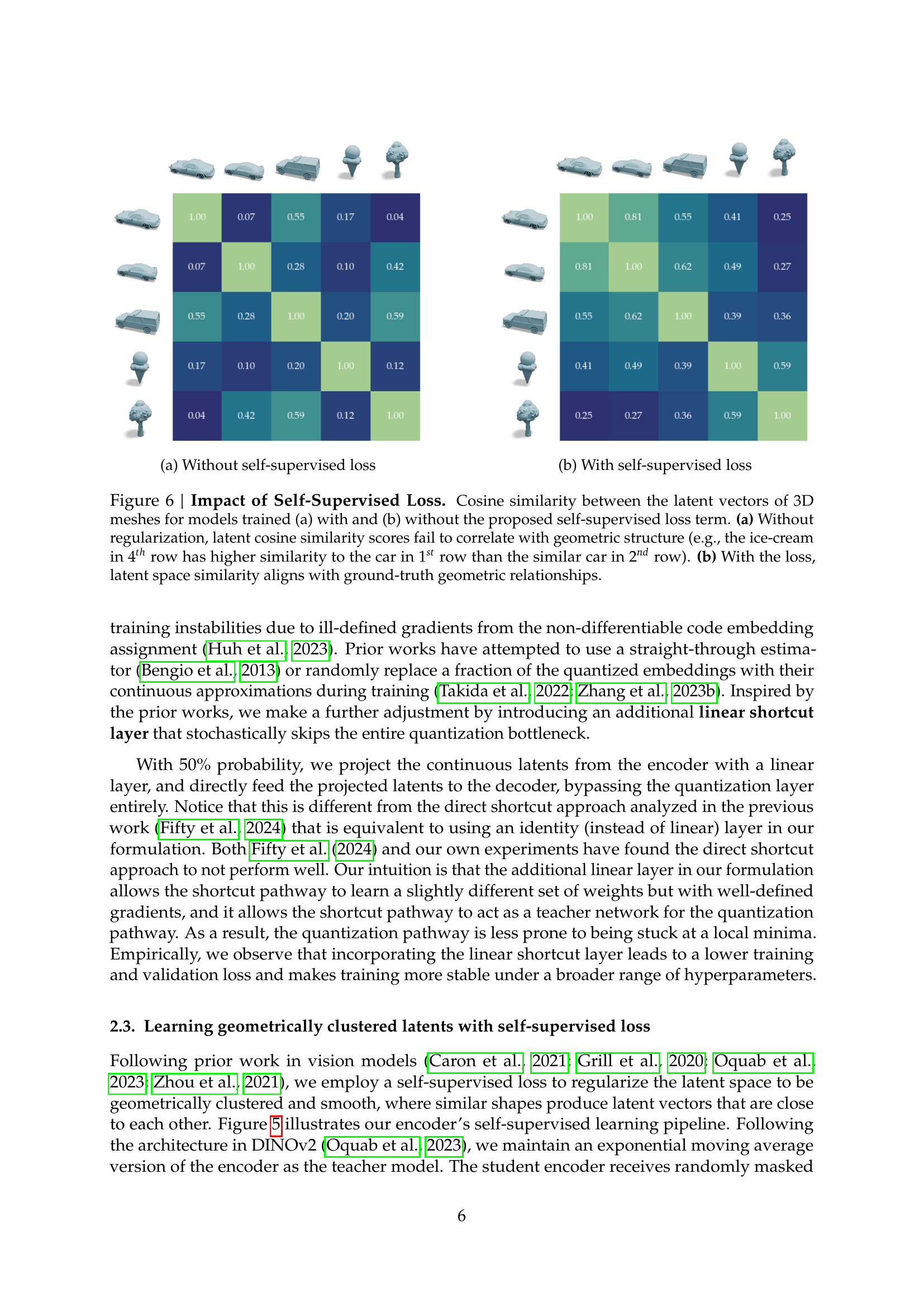

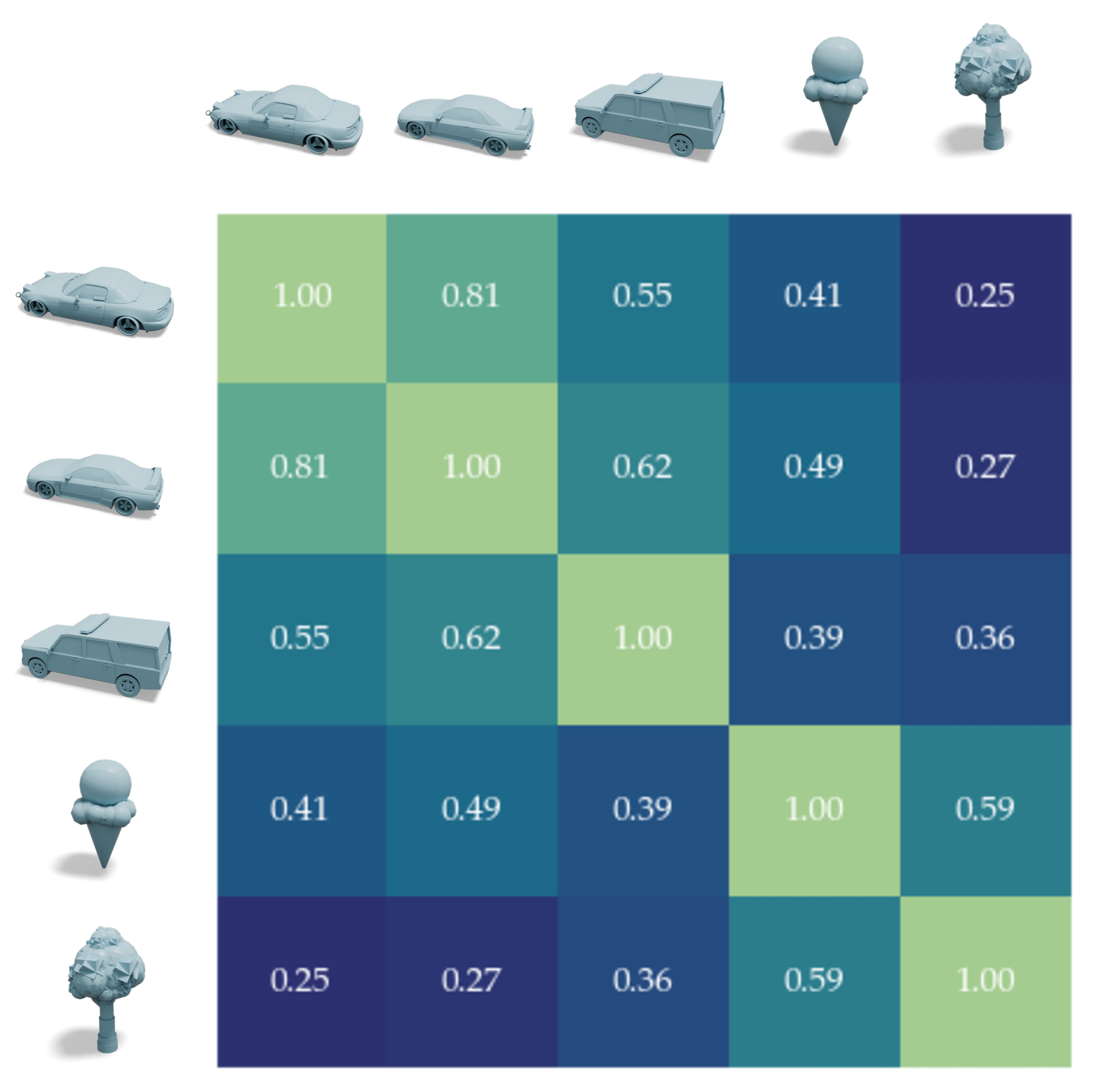

🔼 This figure shows a matrix visualizing the cosine similarity between latent vectors of 3D meshes for a model trained without the self-supervised loss. The lack of regularization results in latent vector similarities that do not correlate well with the geometric similarity of the input meshes. For example, a model trained without the self-supervised loss might show high similarity between dissimilar shapes, and vice versa. This contrasts with the expected behavior that geometrically similar 3D meshes should have similar latent vectors.

read the caption

(a) Without self-supervised loss

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between latent vectors of 3D meshes for models trained with and without the self-supervised loss. The left image (a) demonstrates that without the self-supervised loss, the similarity scores do not accurately reflect the geometric relationships (e.g., an ice cream is closer to a car than to another similar car). The right image (b), however, shows that with the self-supervised loss, the latent space similarities strongly align with the ground-truth geometric relationships, improving the model’s ability to distinguish between similar shapes.

read the caption

(b) With self-supervised loss

🔼 Figure 6 demonstrates the effect of a self-supervised loss on the latent space of a 3D shape encoding model. Two heatmaps show the cosine similarity between latent vectors representing different 3D shapes. (a) shows the results without the self-supervised loss; note the lack of correlation between cosine similarity and visual similarity (e.g., an ice cream is more similar to a car than to another ice cream). (b) shows the results with the self-supervised loss; a strong correlation is now evident between cosine similarity and visual similarity.

read the caption

Figure 6: Impact of Self-Supervised Loss. Cosine similarity between the latent vectors of 3D meshes for models trained (a) with and (b) without the proposed self-supervised loss term. (a) Without regularization, latent cosine similarity scores fail to correlate with geometric structure (e.g., the ice-cream in 4thsuperscript4𝑡ℎ4^{th}4 start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_t italic_h end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT row has higher similarity to the car in 1stsuperscript1𝑠𝑡1^{st}1 start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_s italic_t end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT row than the similar car in 2ndsuperscript2𝑛𝑑2^{nd}2 start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_n italic_d end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT row). (b) With the loss, latent space similarity aligns with ground-truth geometric relationships.

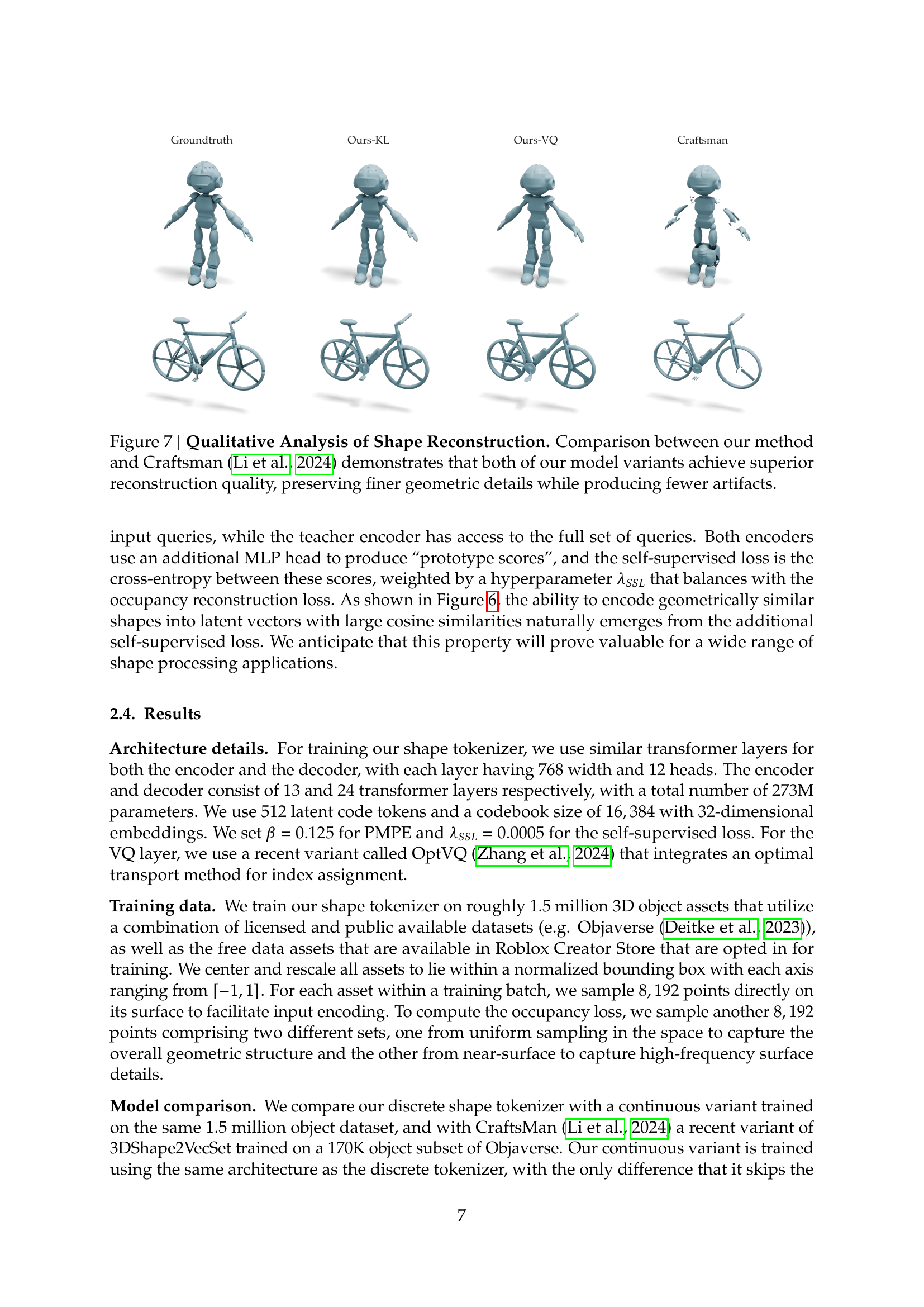

🔼 Figure 7 presents a qualitative comparison of 3D shape reconstruction results between the proposed method and the Craftsman method (Li et al., 2024). The figure visually showcases the superior reconstruction quality achieved by both variants of the proposed model. It highlights the preservation of finer geometric details and a significant reduction in artifacts compared to the Craftsman method.

read the caption

Figure 7: Qualitative Analysis of Shape Reconstruction. Comparison between our method and Craftsman (Li et al., 2024) demonstrates that both of our model variants achieve superior reconstruction quality, preserving finer geometric details while producing fewer artifacts.

🔼 Figure 8 showcases a gallery of 3D models generated by a text-to-shape model. The models demonstrate the model’s capacity to create a wide variety of shapes from textual descriptions, successfully rendering diverse geometries with sharp edges, smooth surfaces, and intricate structures. This highlights the model’s ability to capture complex details from textual input, and generate high-fidelity 3D outputs.

read the caption

Figure 8: Text-to-Shape Generation Result Gallery. Our model can generate a diverse set of 3D meshes, capturing sharp edges, smooth surfaces and complex structures.

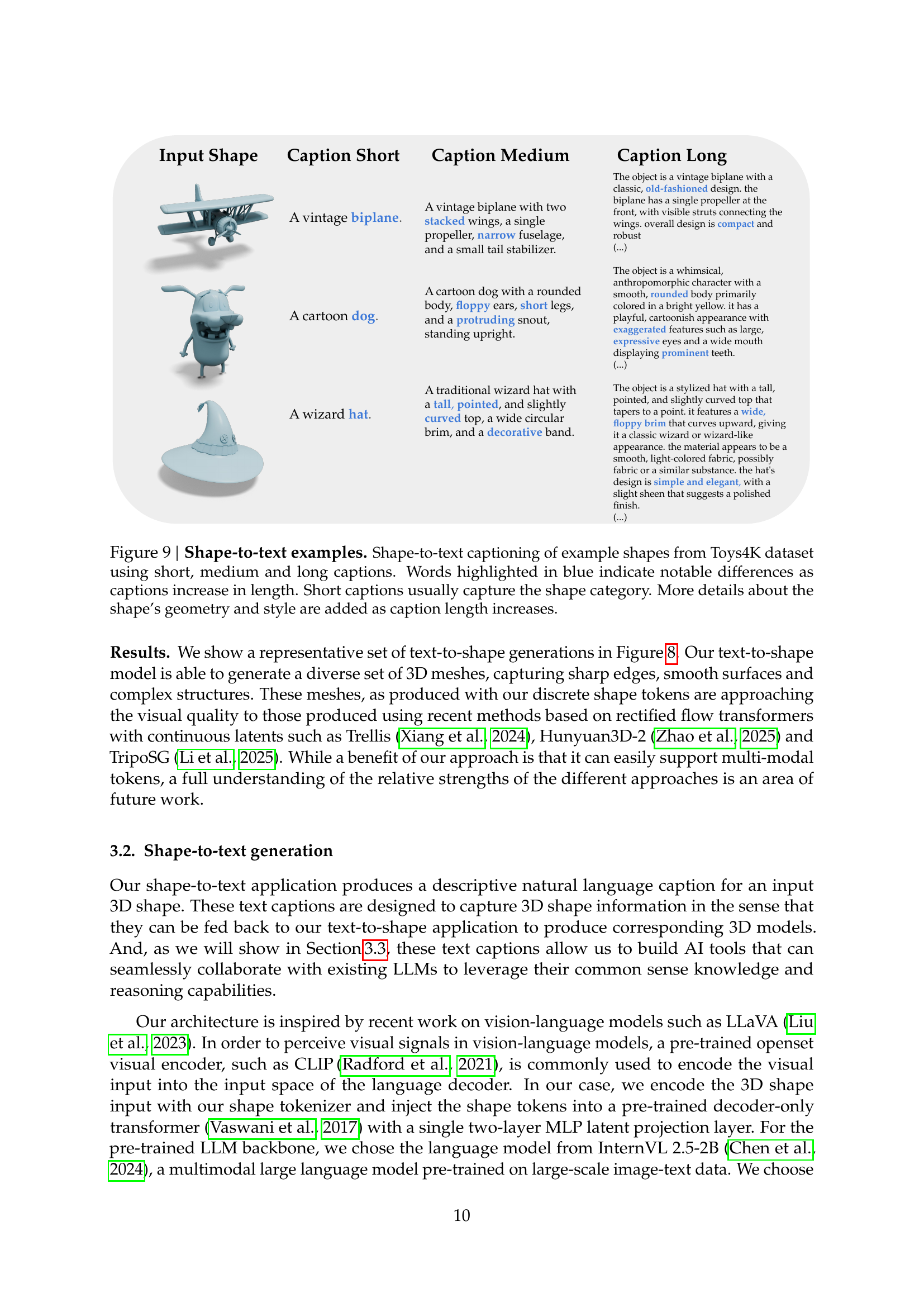

🔼 Figure 9 presents examples of shape-to-text generation from the Toys4K dataset. Three captions of varying lengths (short, medium, and long) are shown for each example shape. The short captions broadly identify the shape category (e.g., ‘A vintage biplane’). As the caption length increases, more details regarding the shape’s specific geometry, style, and features are included, as highlighted by the blue words in the caption. This demonstrates the model’s capacity to generate increasingly detailed and descriptive text from the same visual input as caption length grows.

read the caption

Figure 9: Shape-to-text examples. Shape-to-text captioning of example shapes from Toys4K dataset using short, medium and long captions. Words highlighted in blue indicate notable differences as captions increase in length. Short captions usually capture the shape category. More details about the shape’s geometry and style are added as caption length increases.

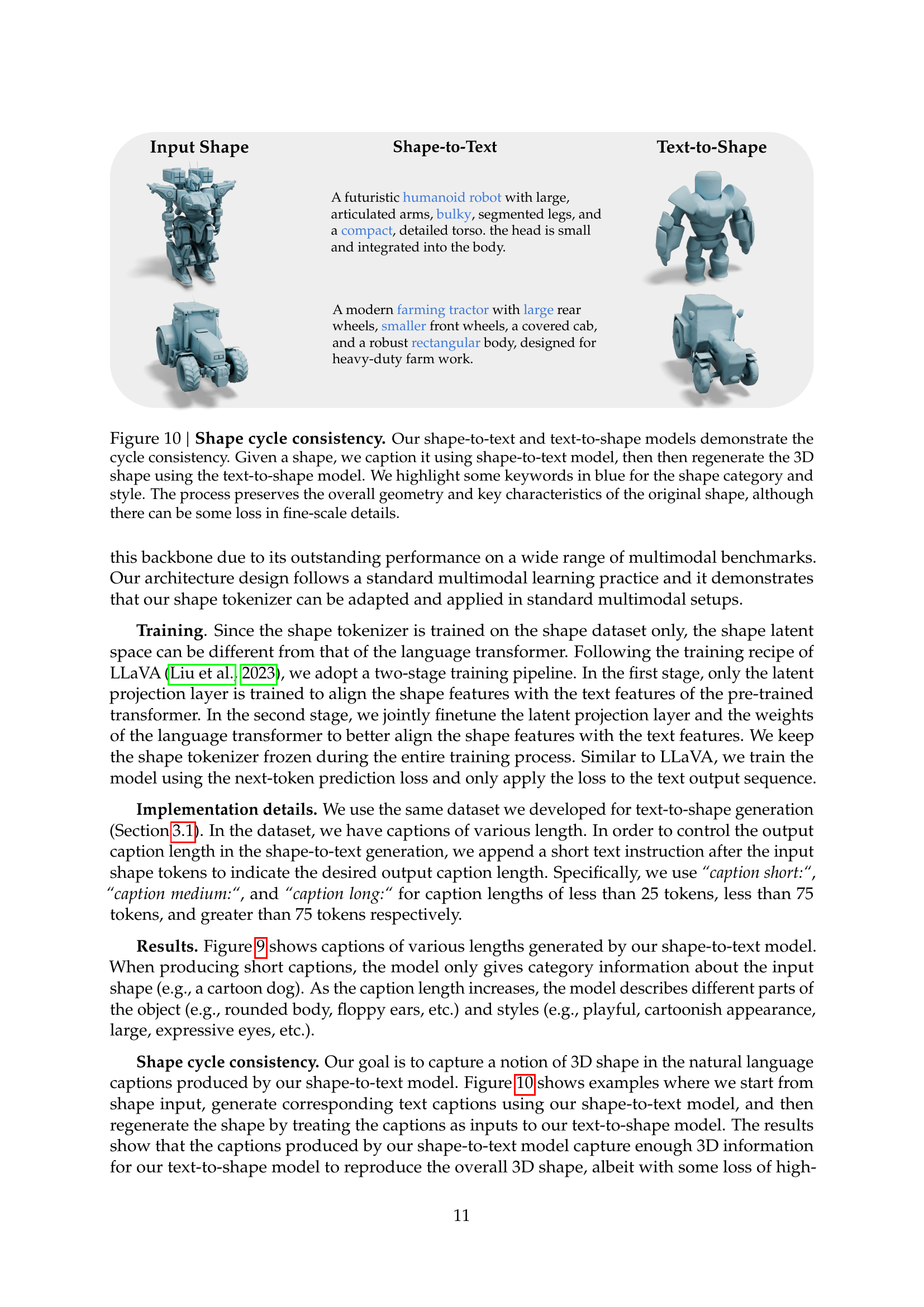

🔼 This figure showcases the cycle consistency of the shape-to-text and text-to-shape models. Starting with a 3D shape, the shape-to-text model generates a textual description. This description is then fed into the text-to-shape model, which attempts to reconstruct the original 3D shape. Key words highlighting the shape category and style are shown in blue. While the overall geometry and main characteristics are preserved, some minor details may be lost in the reconstruction process.

read the caption

Figure 10: Shape cycle consistency. Our shape-to-text and text-to-shape models demonstrate the cycle consistency. Given a shape, we caption it using shape-to-text model, then then regenerate the 3D shape using the text-to-shape model. We highlight some keywords in blue for the shape category and style. The process preserves the overall geometry and key characteristics of the original shape, although there can be some loss in fine-scale details.

Full paper#