TL;DR#

Existing methods for 3D human avatar creation often require extensive per-subject optimization, limiting their real-world use. They struggle with variations in body shape, pose, and clothing, leading to deformation artifacts and high computational costs. Many techniques also rely on laborious manual design or controlled environments, making them impractical for everyday applications. Reconstructing animatable avatars from casually taken photos remains a significant challenge.

This paper introduces FRESA, a novel method for reconstructing personalized 3D human avatars from only a few images. It uses a feed-forward approach, generalizing to casually taken phone photos without fine-tuning. FRESA learns a universal prior from a large dataset of clothed humans, enabling instant generation and zero-shot generalization. It jointly infers personalized avatar shape, skinning weights, and pose-dependent deformations. A 3D canonicalization process and multi-frame feature aggregation reduce artifacts and fuse a plausible avatar, preserving person-specific identities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper introduces an innovative method for creating personalized 3D avatars from a few images, which can be useful in XR, gaming and virtual try-on. It offers a fast and efficient way to generate realistic avatars, reducing the reliance on complex setups or manual design, and opens avenues for real-time avatar creation and animation.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 showcases the results of FRESA, a novel feed-forward method for reconstructing personalized skinned avatars. Panel (a) displays example input images: a few casually taken phone photos of a person. Panel (b) presents the generated 3D avatar, highlighting the personalized skinning weights (influencing how the avatar deforms) associated with key joints. Panel (c) illustrates the pose-dependent animation capabilities of the reconstructed avatar, with colormaps visualizing the magnitude of per-vertex displacement (how much each point on the mesh moves) during animation. FRESA’s key innovation is its ability to create realistic, personalized avatars and animations from limited input data without any per-person fine-tuning.

read the caption

Figure 1: FRESA. We present a novel method to reconstruct personalized skinned avatars with realistic pose-dependent animation all in a feed-forward approach, which generalizes to causally taken phone photos without any fine-tuning. We visualize the predicted skinning weights associated with the most important joints in (b) and colormaps of per-vertex displacement magnitudes222Scales normalized across all vertices to highlight large deformation.during animation in (c).

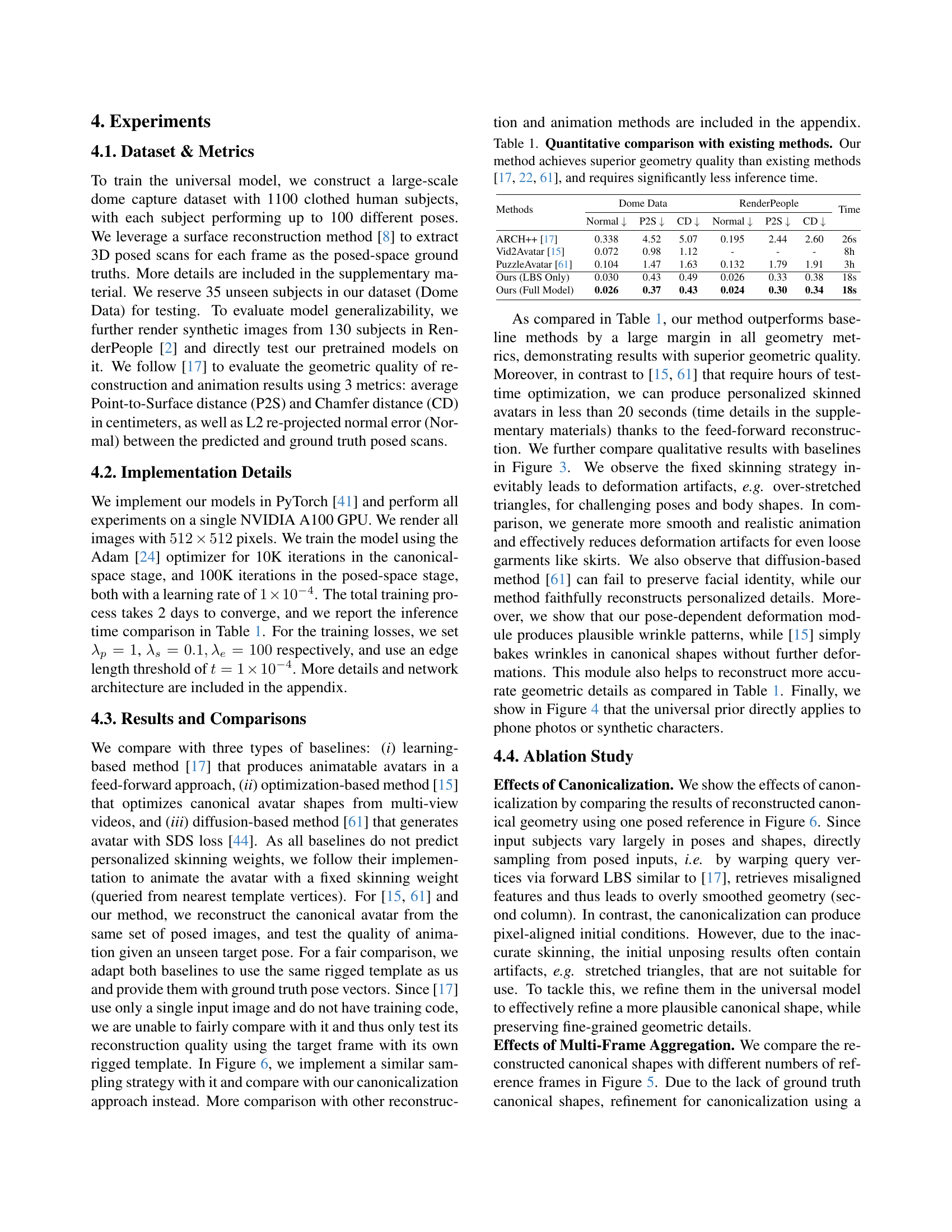

| Methods | Dome Data | RenderPeople | Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | P2S | CD | Normal | P2S | CD | ||

| ARCH++ [17] | 0.338 | 4.52 | 5.07 | 0.195 | 2.44 | 2.60 | 26s |

| Vid2Avatar [15] | 0.072 | 0.98 | 1.12 | - | - | - | 8h |

| PuzzleAvatar [61] | 0.104 | 1.47 | 1.63 | 0.132 | 1.79 | 1.91 | 3h |

| Ours (LBS Only) | 0.030 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.026 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 18s |

| Ours (Full Model) | 0.026 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.024 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 18s |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed FRESA method against existing state-of-the-art methods for 3D clothed human reconstruction and animation. The comparison is done using three metrics: average Point-to-Surface distance (P2S), Chamfer distance (CD), and L2 re-projected normal error (Normal). Lower values indicate better performance. The table shows that FRESA achieves superior geometry reconstruction accuracy (lower P2S, CD, and Normal values) compared to the baseline methods, while simultaneously requiring significantly less inference time.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative comparison with existing methods. Our method achieves superior geometry quality than existing methods [17, 61, 22], and requires significantly less inference time.

In-depth insights#

Zero-Shot Avatars#

The concept of “Zero-Shot Avatars” is compelling because it suggests creating personalized 3D avatars from minimal input, ideally unseen data. The main idea is to build a universal prior from a large, diverse dataset of 3D human scans. This prior is learned during training and enables instant avatar generation and zero-shot generalization. During inference, the model can generate realistic avatars from a few casually taken images, without per-subject optimization or fine-tuning. It may leverage canonicalization to resolve pose variations, multi-frame aggregation to generate a plausible avatar, and personalized skinning weights to ensure realistic animation. It addresses the limitations of existing methods by achieving efficient feed-forward reconstruction and improved realism. Extensive experiments are needed to validate generalization across different body shapes, cloth types, and image qualities. The method outperforms state-of-the-art reconstruction and animation techniques, and it is directly applied to inputs from casually taken phone photos or synthetic characters.

Canon. Improves Detail#

While “Canon. Improves Detail” isn’t a direct heading from the paper, the idea of canonicalization enhancing detail is central to FRESA. The method uses 3D canonicalization to obtain pixel-aligned initial conditions, which normalizes pose variations and helps to resolve ambiguities between canonical shapes and skinning weights. This allows for better feature extraction and reconstruction of fine-grained details compared to directly sampling from posed inputs. The multi-frame aggregation further reduces artifacts from the canonicalization process. In essence, the canonicalization acts as a crucial pre-processing step, enabling the universal model to learn and generate more plausible and detailed avatars, as seen in the ablation study where results show improvement by mitigating over-smoothing.

Multi-frame Fusion#

Multi-frame fusion, in the context of 3D human avatar reconstruction from few images, is a crucial technique for enhancing the robustness and fidelity of the generated models. Given the challenges posed by varying poses, clothing styles, and potential occlusions in individual frames, a method that effectively integrates information from multiple views or temporal snapshots can significantly improve the overall quality of the reconstructed avatar. The core idea is to leverage complementary information from different frames to mitigate the impact of noise and artifacts present in any single view. This involves extracting relevant features from each frame, such as geometric details, texture cues, and semantic information. Then aggregate these features into a unified representation which can be further used to generate a more complete and accurate 3D model. Crucially, the fusion process should be designed to be robust to imperfect pose estimation and misalignment between frames. A well-designed multi-frame fusion strategy can lead to more realistic and detailed avatars, with improved animation capabilities and better overall visual quality. This aggregation can be performed at various stages of the reconstruction pipeline, such as feature level, mesh level or image level.

Animation Artifacts#

The research confronts challenges regarding animation artifacts that stem from imperfect skinning techniques. Existing methods relying on nearest-neighbor skinning from rigged templates often produce unrealistic deformations, especially in challenging poses. To mitigate this, they employ personalized skinning weights and pose-dependent deformation modules, improving animation quality and reducing artifacts. Jointly optimizing canonical shapes and skinning weights, alongside a novel 3D canonicalization process, further refines geometric details, ensuring authentic reconstructions and animations. The use of a universal clothed human model is key, enabling instant feed-forward generation and zero-shot generalization to diverse inputs, including casually taken phone photos. Additionally, multi-frame feature aggregation robustly reduces artifacts introduced during canonicalization.

Pose Limits#

The ‘Pose Limits’ section of a research paper focusing on human avatar reconstruction likely addresses the constraints and challenges imposed by extreme or unusual poses. Existing methods often struggle with complex articulations due to self-occlusion, non-linear deformations, and data scarcity. The section might discuss how these limitations affect the accuracy and realism of avatar generation, potentially exploring techniques to mitigate pose-related artifacts. It could involve strategies like data augmentation with synthetic poses, incorporating priors based on biomechanical constraints, or developing pose-invariant features. Furthermore, it could elaborate on specific pose-dependent deformation models or skinning techniques to handle the issue of incorrect rigging when body parts intersect. The section may compare against pose-robust methods that can efficiently reconstruct plausible 3D avatars despite strong pose variation, and discuss the trade-off between model complexity, computational cost, and overall quality of the reconstructed avatars in extreme poses.

More visual insights#

More on figures

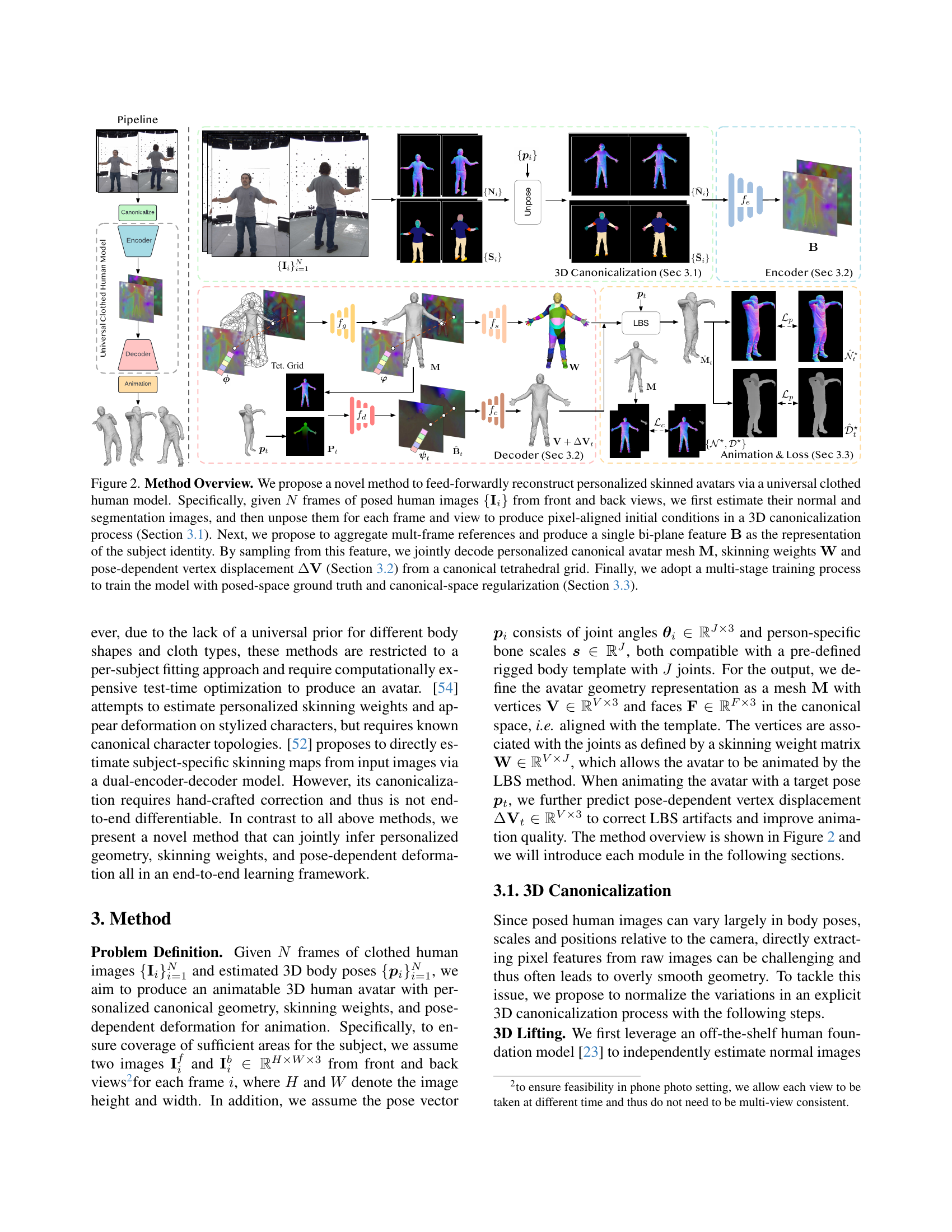

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed method, FRESA, for feed-forward reconstruction of personalized skinned avatars. Starting with multiple frames of posed images, the system first performs 3D canonicalization to create pixel-aligned initial conditions. These are then processed to produce a bi-plane feature representing the subject’s identity. This feature is used to decode the personalized canonical avatar mesh, skinning weights, and pose-dependent vertex displacement from a canonical tetrahedral grid. The model is trained using a multi-stage process that incorporates both posed-space ground truth and canonical-space regularization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Method Overview. We propose a novel method to feed-forwardly reconstruct personalized skinned avatars via a universal clothed human model. Specifically, given N𝑁Nitalic_N frames of posed human images {𝐈i}subscript𝐈𝑖\{\mathbf{I}_{i}\}{ bold_I start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT } from front and back views, we first estimate their normal and segmentation images, and then unpose them for each frame and view to produce pixel-aligned initial conditions in a 3D canonicalization process (Section 3.1). Next, we propose to aggregate mult-frame references and produce a single bi-plane feature 𝐁𝐁\mathbf{B}bold_B as the representation of the subject identity. By sampling from this feature, we jointly decode personalized canonical avatar mesh 𝐌𝐌\mathbf{M}bold_M, skinning weights 𝐖𝐖\mathbf{W}bold_W and pose-dependent vertex displacement Δ𝐕Δ𝐕{\Delta}\mathbf{V}roman_Δ bold_V (Section 3.2) from a canonical tetrahedral grid. Finally, we adopt a multi-stage training process to train the model with posed-space ground truth and canonical-space regularization (Section 3.3).

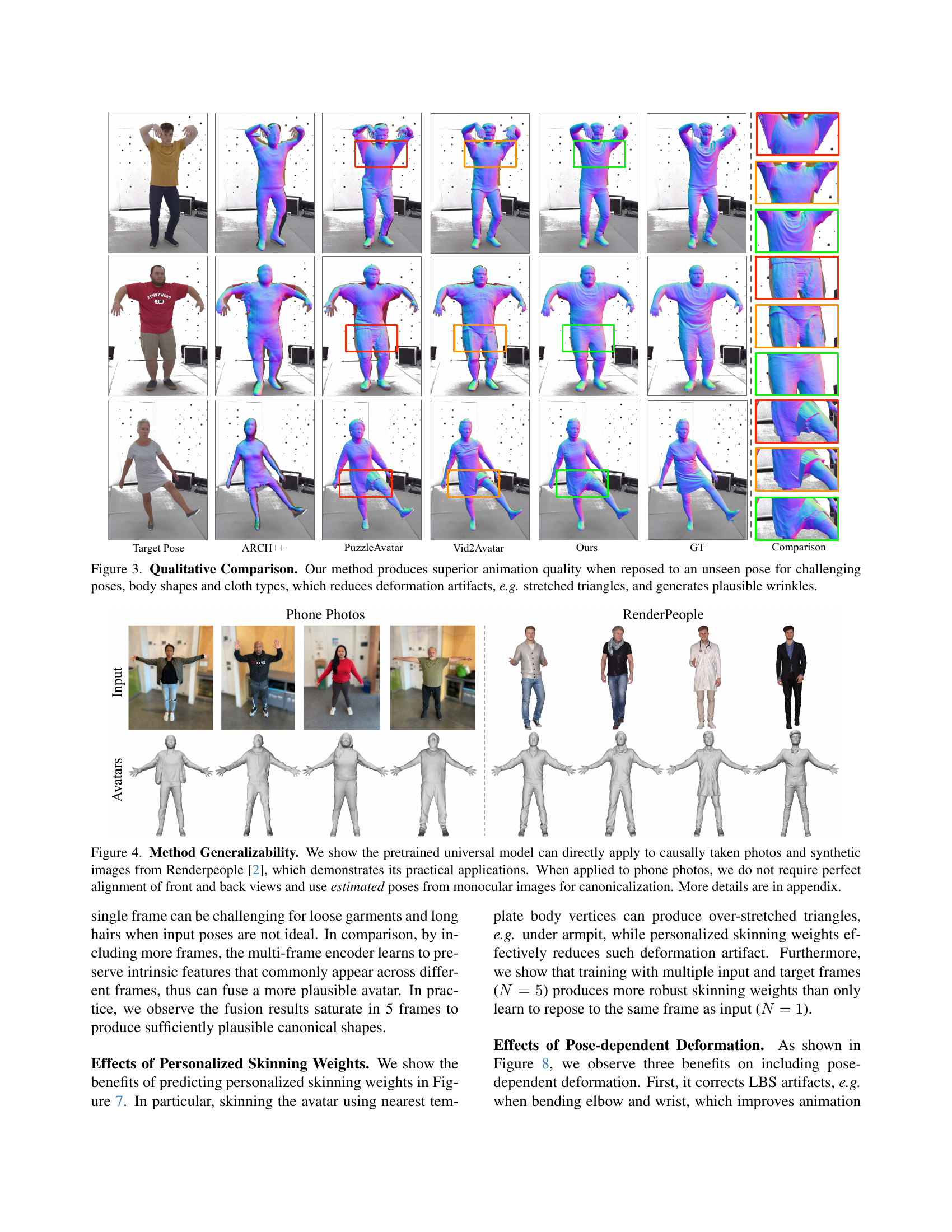

🔼 This figure compares the animation results of different methods when applied to challenging poses and body shapes. The results demonstrate that the proposed method (Ours) produces significantly better animation quality by minimizing deformation artifacts (such as stretched triangles) and creating more realistic wrinkles in clothing compared to existing methods such as ARCH++, PuzzleAvatar, and Vid2Avatar. The ground truth (GT) animation is also included for comparison.

read the caption

Figure 3: Qualitative Comparison. Our method produces superior animation quality when reposed to an unseen pose for challenging poses, body shapes and cloth types, which reduces deformation artifacts, e.g. stretched triangles, and generates plausible wrinkles.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the generalizability of the proposed method, FRESA, by showcasing its ability to reconstruct 3D clothed human avatars from various input sources. The leftmost column shows casually taken photos of individuals in various poses. The images are unconstrained and do not require any specific setup (such as multiple camera views perfectly aligned). The model successfully reconstructs avatars using only estimated poses from monocular (single-view) images. Subsequent columns show results when the model is applied to synthetic data (RenderPeople dataset), further showcasing the model’s versatility and ability to generalize well to unseen data. The results highlight the effectiveness of FRESA’s universal prior in handling variations in body shapes, poses, and clothing styles.

read the caption

Figure 4: Method Generalizability. We show the pretrained universal model can directly apply to causally taken photos and synthetic images from Renderpeople [2], which demonstrates its practical applications. When applied to phone photos, we do not require perfect alignment of front and back views and use estimated poses from monocular images for canonicalization. More details are in appendix.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of multi-frame aggregation on the quality of canonical shape reconstruction. The left side shows a set of unposed normal frames from a single person in various poses. The right side displays the results of reconstructing canonical shapes using an increasing number of frames (N=1, 3, 5, 10). As more frames are included in the aggregation process, the reconstructed shapes become more refined, accurately capturing fine details such as skirts and hair, and minimizing artifacts caused by the initial unposing step, while maintaining individual characteristics.

read the caption

Figure 5: Effects of multi-frame aggregation. Given a set of unposed normal frames from different poses in the left, we show results of fused canonical shapes using the first N𝑁Nitalic_N frames at each column in the right. we observe that aggregation from multiple frames produces more plausible canonical shapes by correcting unposing artifacts, e.g. on skirts and hairs, while preserving person-specific details.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the 3D canonicalization process in improving the quality of reconstructed avatars. The leftmost column shows the results of directly warping features from posed input images, as done in the ARCH++ method ([17]). This approach leads to noticeable artifacts due to pose variations. The following columns show how the universal model leverages the canonicalized representations (produced via the canonicalization process) to reduce these artifacts and achieve higher fidelity reconstructions that better preserve fine-grained details. This highlights the benefit of normalizing pose variations before feeding data into the neural network, resulting in more accurate and detailed 3D avatar reconstruction.

read the caption

Figure 6: Effects of canonicalization. By taking canonicalization results as inputs, the universal model can learn to reduce unposing artifacts and preserve fine-grained details, compared to directly sampling features from posed inputs via forward warping as [17].

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of using personalized skinning weights versus using weights derived from the nearest template vertices. The images show that using personalized weights results in fewer artifacts, particularly around areas such as the armpits, due to the model’s ability to better account for individual body shapes. The results also illustrate that training the model on multiple input and target frames improves the robustness and accuracy of the personalized skinning weight estimation, leading to more natural and realistic deformations in the avatar.

read the caption

Figure 7: Effects of personalized skinning weights. We show personalized skinning weights reduce deformation artifacts, e.g. under armpit, and can be more robustly estimated when trained with multiple input and target frames. Note we show results deformed by LBS only, i.e. without pose-dependent deformation.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of the pose-dependent deformation module on animation quality. The top row showcases examples where the module corrects Linear Blend Skinning (LBS) artifacts, specifically addressing unnatural bending in wrists and arms that often occur during animation. The bottom row highlights the module’s ability to generate realistic garment dynamics, such as the natural draping of sleeves, which greatly enhances the realism of the animation. This improved realism is achieved by adding the deformation module to compensate for shortcomings in standard LBS animation techniques.

read the caption

Figure 8: Effects of Pose-dependent Deformation. The deformation module can correct LBS artifacts (wrist and arm bending in first row) and generate plausible garment dynamics (sleeves draping in second row), which improves animation realism.

🔼 Figure 9 shows examples from the dome capture dataset used in the FRESA paper. The dataset consists of a large number of clothed individuals captured in various poses, with each pose paired with a high-quality 3D scan. These paired data points (images and 3D scans) allow for supervised learning of a robust and generalizable universal prior for clothed human reconstruction, which is crucial for the method’s ability to generate realistic avatars from limited input.

read the caption

Figure 9: Samples of dome data. Our dataset contains diverse posed clothed humans paired with high-quality 3D scans as ground truths, which facilitates learning an effective universal prior.

🔼 Figure 10 compares two methods for unposing 3D surface meshes: naive unposing (used during inference) and a more refined method using optimization (used during data preparation). The naive approach uses an arbitrary skinning weight and a deterministic unposing process, which is faster but can result in artifacts. In contrast, the optimization-based approach finds optimal skinning weights, leading to more accurate and plausible results but at a substantially higher computational cost. The figure visualizes the outputs of both methods, illustrating the tradeoff between speed and accuracy. Edges shorter than 1e-4 are filtered to minimize noise.

read the caption

Figure 10: Unposing Comparison. We compare the results between naive unposing (used in the inference pipeline) and pseudo GT via optimization (used for data preparation). The second approach produces more plausible results but requires significantly more time. Note we filter edges with length larger than 1×10−41superscript1041\times 10^{-4}1 × 10 start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT - 4 end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT to reduce noises.

🔼 Figure 11 demonstrates the flexibility of FRESA in handling casually taken photos. Unlike methods requiring precise multi-view consistency, FRESA only needs a front and back view of a subject. The images don’t have to be perfectly aligned or taken at the same time. The system uses estimated body poses instead of relying on perfectly accurate pose data, making the process more practical for real-world applications where such precision is often unattainable.

read the caption

Figure 11: Illustration of settings for photos. We use estimated body poses and do not require perfect alignment between views.

🔼 This figure visualizes the intermediate step of 3D canonicalization in the FRESA pipeline. The input is a set of posed images of a clothed human. These images are first processed to generate a surface mesh for each view (front and back). A process called ‘unposing’ then aims to align these meshes to a canonical (neutral) pose. However, due to the challenges of estimating accurate skinning weights at this stage, the unposing process may result in some geometric artifacts, such as overly stretched triangles. These artifacts are removed in a subsequent step. The figure shows the two unposed surface meshes, before artifact removal, highlighting the fact that they are not perfectly aligned at their boundaries due to imperfections in the unposing process.

read the caption

Figure 12: Illustration of Lifted Surface Meshes. Note we removed the over-stretched edges after unposing. The lifting process produces two unposed surface meshes but can not be perfectly aligned in boundary.

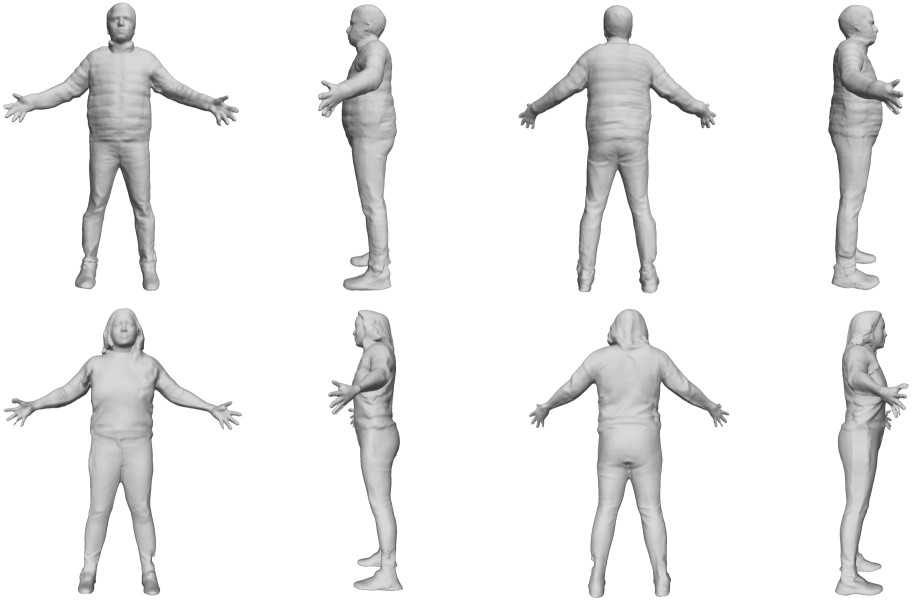

🔼 This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate a complete 3D avatar from only front and back views. The input consists of images from the front and back, and the output shows four views (front, back, and two side views) of the generated 3D model, highlighting that the model can infer a plausible side view geometry that is consistent with the front and back views, producing a coherent overall representation of the body shape.

read the caption

Figure 13: Visualization in Four Views. By only taking inputs of front and back views, our method can infer plausible side-view geometry and produce a consistent boundary.

🔼 Figure 14 visualizes the results of inferred body shapes produced by the proposed method. The figure demonstrates that the method’s ability to generate personalized body shapes is not limited by the initial template shape. Instead, the algorithm infers the body shape directly from the input data, leading to more accurate and realistic results.

read the caption

Figure 14: Results of Inferred Body Shape. Our method can produce personalized body shapes based on input conditions and is not restricted to the template shape.

🔼 This figure compares the animation results of the proposed FRESA method and the SCANimate method [49]. Both methods generate animated avatars. However, for SCANimate, the authors used the 3D avatar meshes reconstructed by FRESA as input to ensure a fair comparison. The comparison highlights the differences in animation quality, particularly noting that the SCANimate method, being based on the SMPL model, lacks the detailed hand motion capabilities exhibited by the FRESA method.

read the caption

Figure 15: Animation comparison with SCANimate. For [49], we use FRESA reconstructions as reference posed meshes. Note that hand motions are missing as it is SMPL-based.

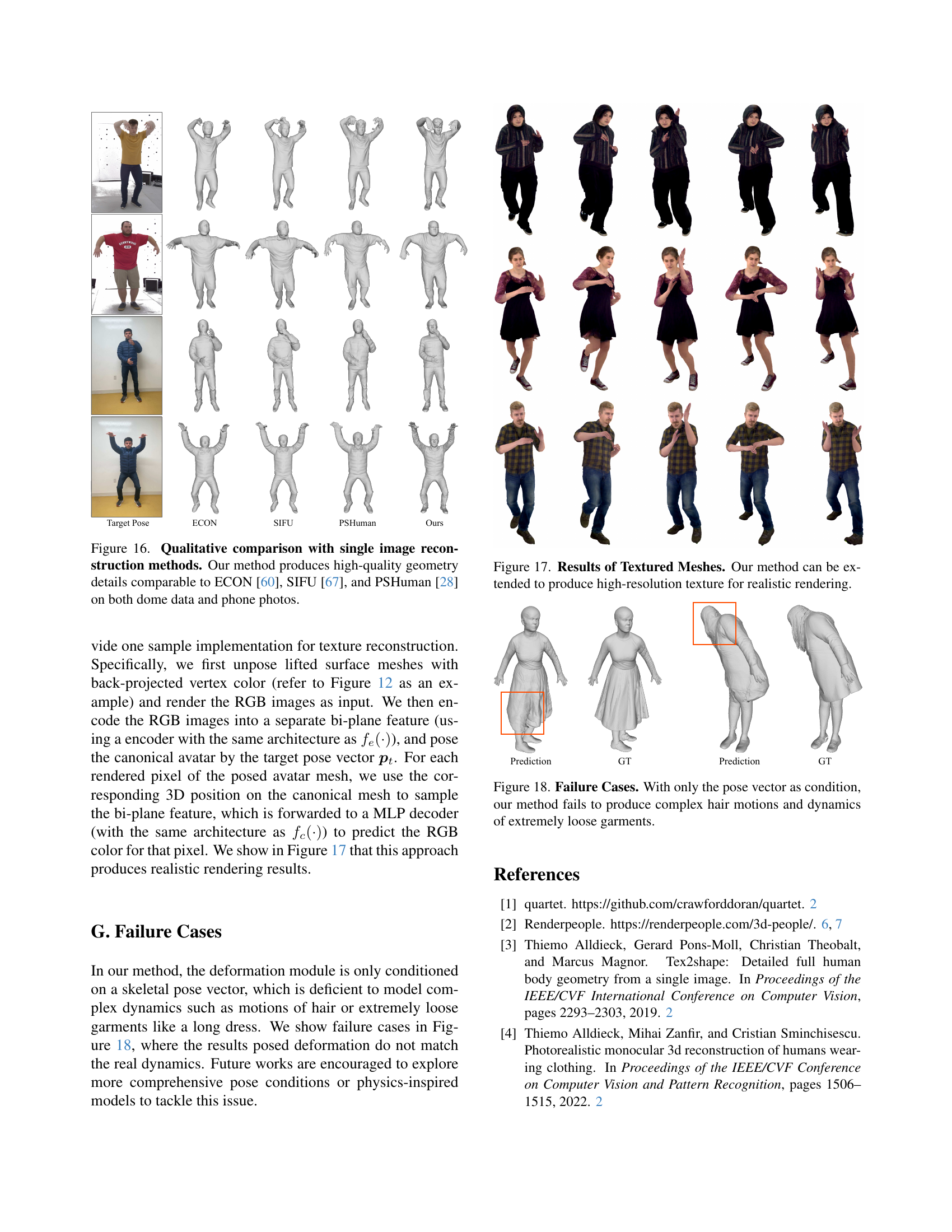

🔼 Figure 16 presents a qualitative comparison of 3D human reconstruction results between the proposed method and three state-of-the-art single-image reconstruction methods: ECON, SIFU, and PSHuman. The comparison highlights the ability of the proposed method to achieve high-quality geometric details comparable to these existing methods, even when using both dome-captured data and casually taken phone photos as input. This demonstrates the robustness and generalizability of the proposed approach for reconstructing high-fidelity 3D human models from various data sources.

read the caption

Figure 16: Qualitative comparison with single image reconstruction methods. Our method produces high-quality geometry details comparable to ECON [60], SIFU [67], and PSHuman [28] on both dome data and phone photos.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the extension of the proposed method to generate high-resolution textures for the reconstructed avatars. It showcases realistic rendering of clothed human avatars with detailed and accurate textural mapping, significantly enhancing the visual fidelity of the results. The texture generation process leverages the method’s capabilities to produce a plausible rendering.

read the caption

Figure 17: Results of Textured Meshes. Our method can be extended to produce high-resolution texture for realistic rendering.

🔼 This figure showcases the limitations of the model when dealing with complex, dynamic elements such as hair and extremely loose-fitting clothing. Because the model is primarily conditioned on the pose vector, it struggles to accurately generate the realistic movement and interaction of these elements, resulting in less accurate or unnatural-looking animations. The figure highlights instances where the model fails to properly simulate the physics and intricacies of hair and loose clothing, demonstrating a key area where the model’s capabilities are limited.

read the caption

Figure 18: Failure Cases. With only the pose vector as condition, our method fails to produce complex hair motions and dynamics of extremely loose garments.

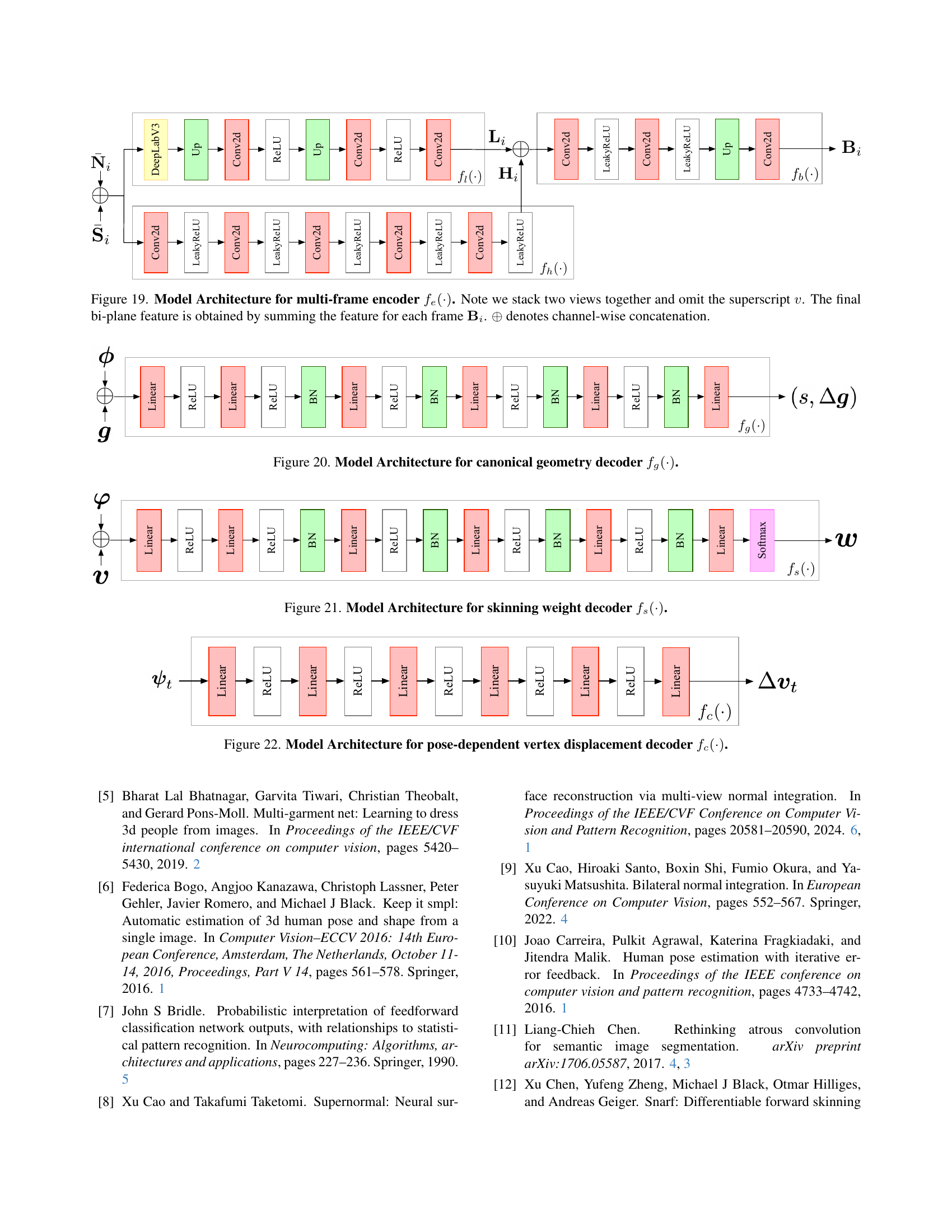

🔼 Figure 19 details the architecture of the multi-frame encoder, a crucial part of the FRESA model. The encoder processes input images from both front and back views, which are stacked to take advantage of information from both perspectives. The model uses two branches: one focusing on fine-grained details and the other on global identity. These two branches extract feature maps which are then concatenated. The features from all input frames (N frames in total) are aggregated by averaging these concatenated feature maps to produce a final bi-plane feature. This bi-plane feature is a key representation of the subject’s identity, summarizing information from multiple views and frames, while also filtering pose variations. This final bi-plane feature is then fed into later stages for avatar reconstruction and animation.

read the caption

Figure 19: Model Architecture for multi-frame encoder fe(⋅)subscript𝑓𝑒⋅f_{e}(\cdot)italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_e end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( ⋅ ). Note we stack two views together and omit the superscript v𝑣vitalic_v. The final bi-plane feature is obtained by summing the feature for each frame 𝐁isubscript𝐁𝑖\mathbf{B}_{i}bold_B start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. ⊕direct-sum\oplus⊕ denotes channel-wise concatenation.

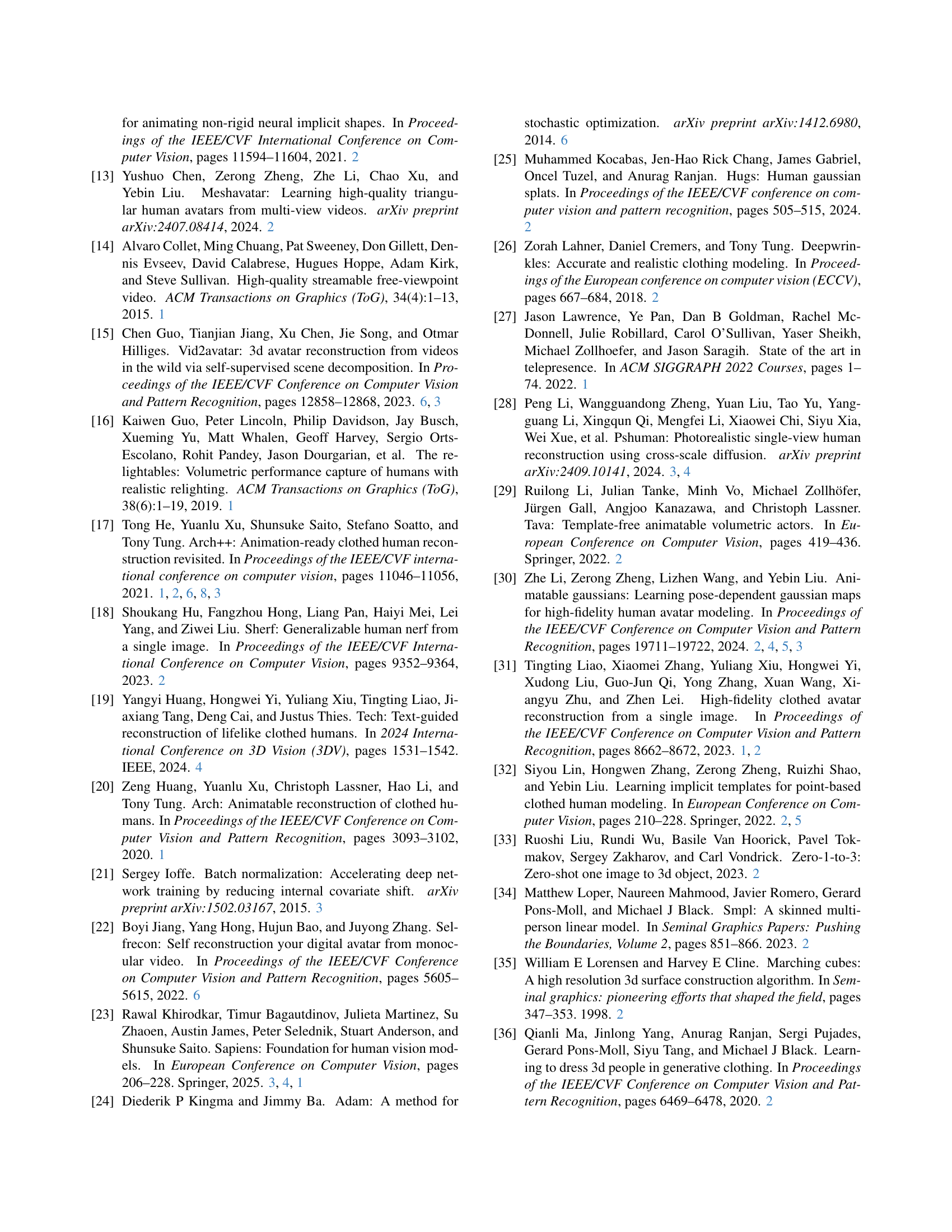

🔼 The figure shows the architecture of the canonical geometry decoder, a crucial component in the FRESA model. This decoder takes as input a feature vector derived from the multi-frame encoder and the 3D position of a grid vertex. It utilizes multiple layers of linear transformations and ReLU activation functions to predict the signed distance field (SDF) values and vertex displacement for each grid vertex in a canonical tetrahedral grid. The output SDF values are subsequently used in a Marching Tetrahedra algorithm to extract a canonical mesh representation of the human avatar.

read the caption

Figure 20: Model Architecture for canonical geometry decoder fg(⋅)subscript𝑓𝑔⋅f_{g}(\cdot)italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_g end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( ⋅ ).

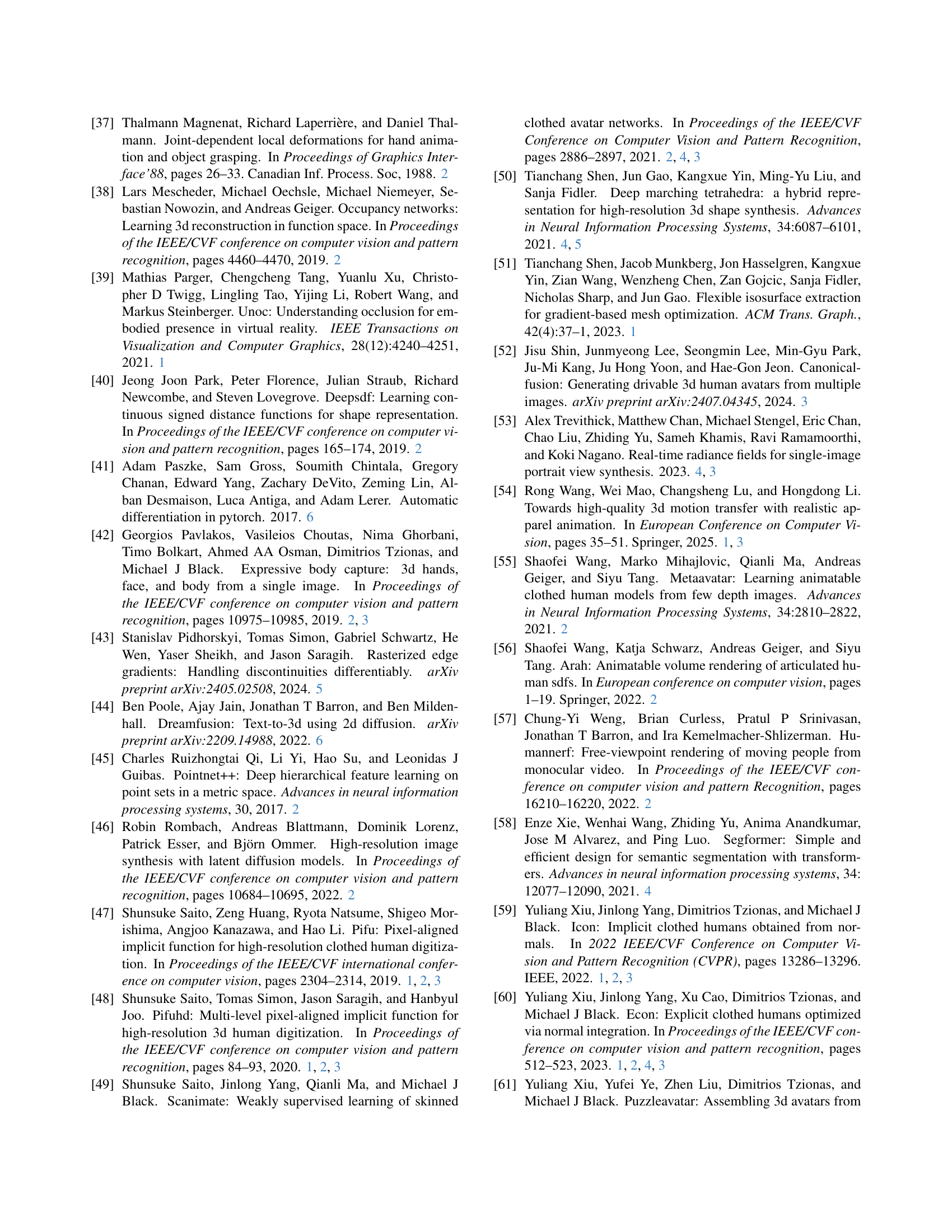

🔼 The figure shows the architecture of the skinning weight decoder, a component of the FRESA model. It takes as input the bi-plane feature and the canonical vertex position, then passes them through several linear layers with batch normalization and ReLU activation before outputting the skinning weights using a softmax layer to ensure valid probabilities. This decoder’s design aims to produce smooth animation by encouraging neighboring vertices to have similar weights, thus generating a more consistent skinning across the whole mesh.

read the caption

Figure 21: Model Architecture for skinning weight decoder fs(⋅)subscript𝑓𝑠⋅f_{s}(\cdot)italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_s end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( ⋅ ).

Full paper#