↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Interactive preference learning systems traditionally rely on binary choices to infer user preferences. However, this approach has limitations as it does not capture the strength of preferences. This paper addresses this issue by incorporating human response times as complementary information to choices, acknowledging the inverse relationship between response time and preference strength. This means quicker responses indicate stronger preferences.

The study introduces a computationally efficient method that combines both choices and response times to estimate user preferences. This method is theoretically and empirically compared to traditional choice-only methods, demonstrating superior performance, particularly for easy queries (those with strong preferences). This efficient method is then successfully integrated into preference-based linear bandits for fixed-budget best-arm identification, showing significant performance gains in simulations using real-world datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it introduces a novel approach to enhance preference-based bandit algorithms by leveraging human response times as an additional source of information. This improves the efficiency of preference learning, particularly for problems with many options or weak preferences. This research opens new avenues for developing more effective and user-friendly interactive systems in various applications.

Visual Insights#

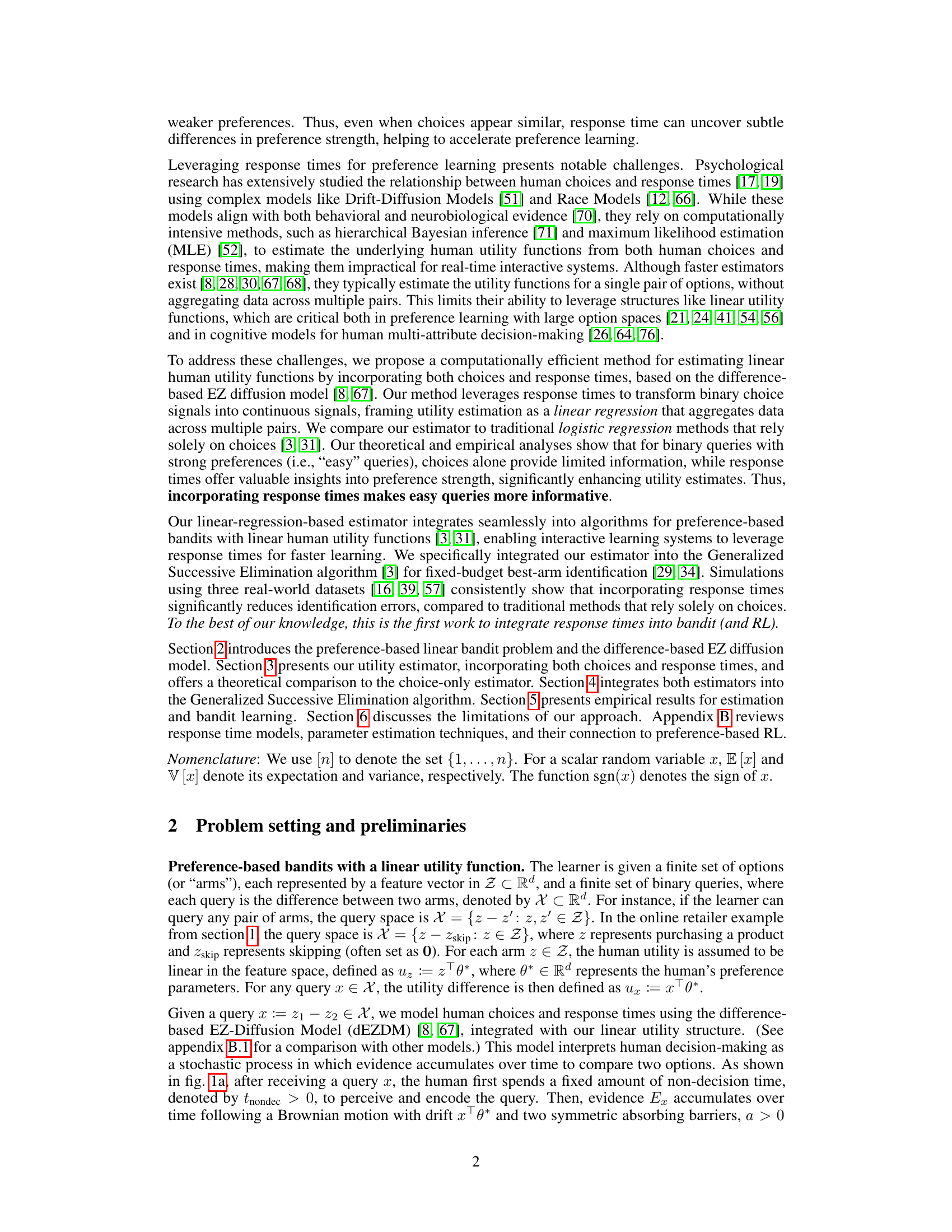

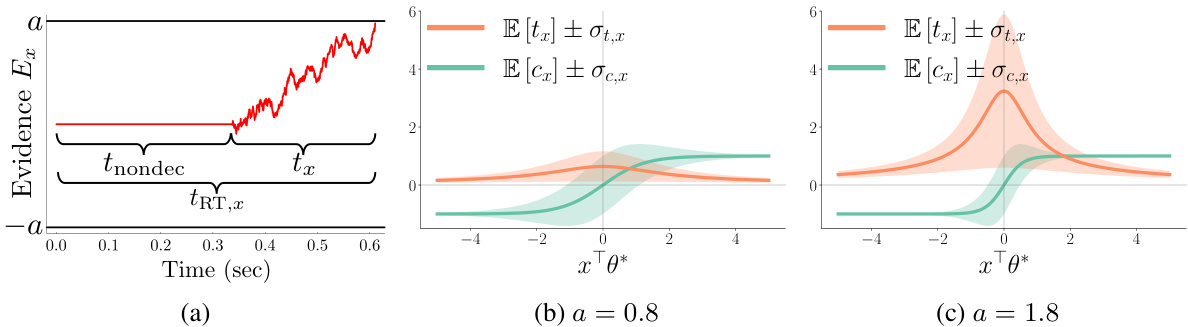

This figure illustrates the human decision-making process as a diffusion process and shows how choice and response time depend on the utility difference and the barrier parameter. Panel (a) shows a graphical representation of the process, illustrating the accumulation of evidence until a decision threshold is reached. Panels (b) and (c) show how the expected choice and response time vary with the utility difference for different barrier values.

In-depth insights#

Response Time’s Role#

Response times, often overlooked in preference learning, offer valuable insights into the strength of user preferences. This paper argues that incorporating response times enhances utility estimates, especially for “easy” queries where preferences are strong. The inverse relationship between response time and preference strength (faster responses indicate stronger preferences) provides complementary information to binary choices alone. The authors propose a computationally efficient method to integrate response times with choices for improved preference estimation. This enhancement leads to more accurate utility function estimations and, importantly, accelerates preference learning in interactive systems like recommender systems and assistive robotics, significantly improving efficiency and reducing error in applications requiring quick preference inference.

EZ Diffusion Model#

The EZ Diffusion Model, a simplified version of the Drift Diffusion Model (DDM), offers a computationally efficient approach for modeling human decision-making by incorporating both choices and response times. Its key advantage lies in its closed-form solutions for choice and response time moments, which contrasts with the computationally intensive methods often required for DDM parameter estimation. The model assumes a deterministic drift, reflecting the utility difference between options, and a fixed starting point, facilitating parameter estimation with a linear regression method in a linear utility structure. This efficiency is crucial in real-time applications like interactive preference learning systems, where the model must quickly adapt to incoming human responses. However, the model’s simplicity also introduces limitations. Assumptions such as deterministic drift and fixed parameters might not fully capture the variability of human decision-making. Despite these limitations, its efficiency for transforming binary choice signals into continuous signals makes the EZ Diffusion Model a powerful tool for integrating human response time data in preference learning and bandit algorithms.

Bandit Algorithm#

The core of this research paper revolves around preference-based bandit algorithms, a type of machine learning designed to learn user preferences through interactive queries. The algorithm efficiently balances exploration (trying different options) and exploitation (choosing the currently best-known option), aiming to maximize cumulative reward while minimizing the number of queries. The key innovation lies in leveraging human response times as additional feedback, supplementing traditional binary choice data. Response time, it is hypothesized, inversely correlates with preference strength, providing a richer signal than choices alone. The paper introduces a novel, computationally efficient method for estimating utility functions, incorporating both choice and response time data, which is theoretically compared and empirically validated against conventional choice-only estimators. This enhancement drastically accelerates preference learning, allowing the algorithm to make better arm selection with fewer interactions, especially when dealing with easy queries (strong preferences). The integration of the proposed estimator into the Generalized Successive Elimination algorithm further streamlines the learning process, enabling faster and more accurate best-arm identification in real-world scenarios.

Real-World Datasets#

The utilization of real-world datasets is crucial for evaluating the efficacy and generalizability of the proposed method. The paper’s selection of three diverse datasets, encompassing different modalities (food choices, snack preferences), enhances the study’s robustness. Each dataset presents unique characteristics which allow for a thorough examination of algorithm performance across various scenarios. The inclusion of varied sample sizes further strengthens the analysis, enabling the assessment of scalability and efficiency. However, a detailed description of data preprocessing steps is essential, as this can significantly influence the results. Transparency in data handling is crucial, especially for ensuring replicability. It is important to note that the paper focuses on the fixed-budget setting, potentially overlooking other crucial aspects of real-world applications. While datasets allow for practical evaluation, a wider range might further validate the findings.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on incorporating human response times in interactive preference learning systems are abundant. Improving the robustness of response time handling is crucial, particularly addressing situations with inconsistent attention or noisy data. Developing algorithms that adaptively leverage response times based on query difficulty would significantly enhance efficiency. Exploring alternative models beyond the EZ-diffusion model, such as race models or attentional DDM, is necessary to broaden applicability and potentially capture more nuanced aspects of human decision-making. Investigating the ethical implications of utilizing response times for preference learning, such as potential biases related to response speed and privacy concerns, must be carefully addressed. Developing robust methods for estimating non-decision time directly from observed data would remove the dependency on prior assumptions. Finally, extending this framework to more complex scenarios, encompassing contextual bandits or reinforcement learning settings, holds significant promise for a variety of real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

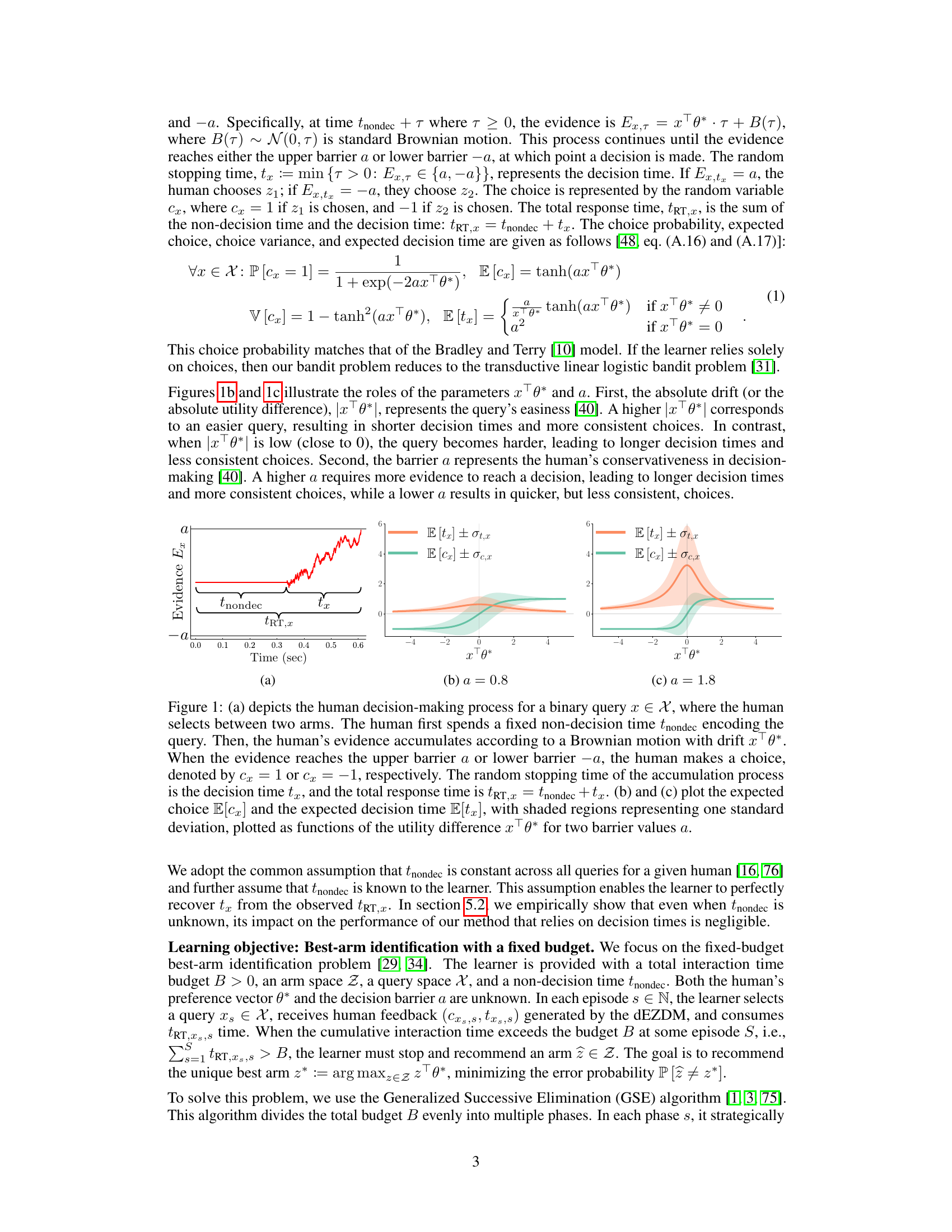

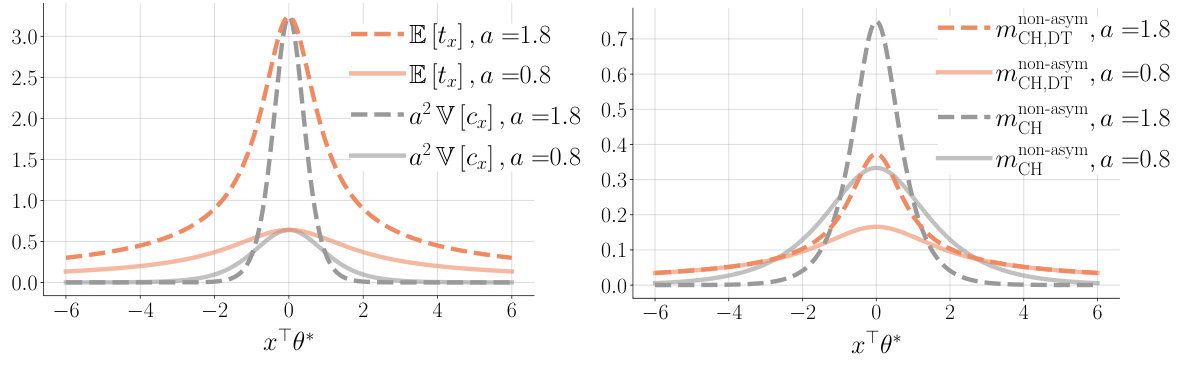

This figure shows the key terms from the theoretical analysis comparing the choice-decision-time estimator and choice-only estimator. Panel (a) compares the asymptotic variances, highlighting how incorporating response times makes easy queries more informative. Panel (b) compares the weights in non-asymptotic concentration bounds, showing similar trends.

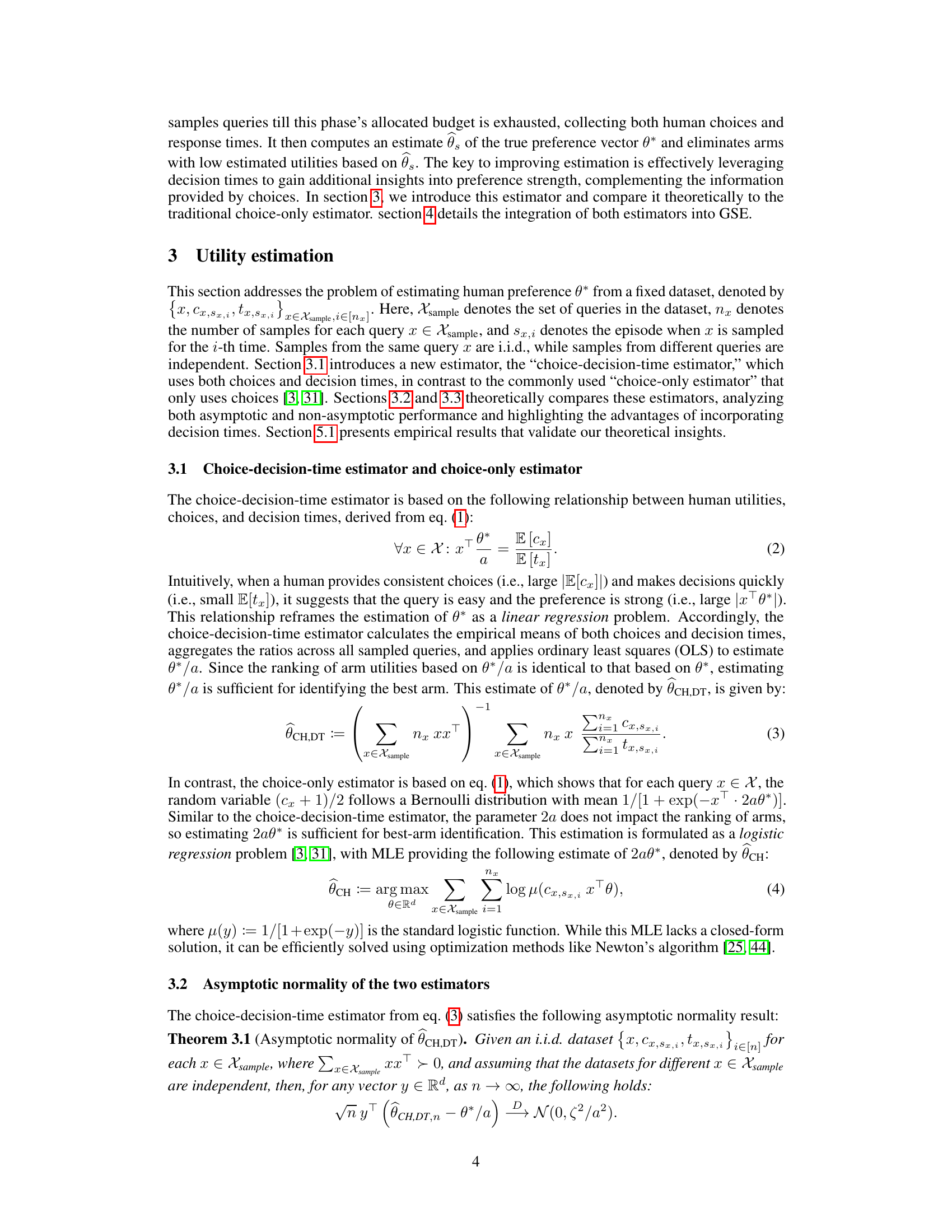

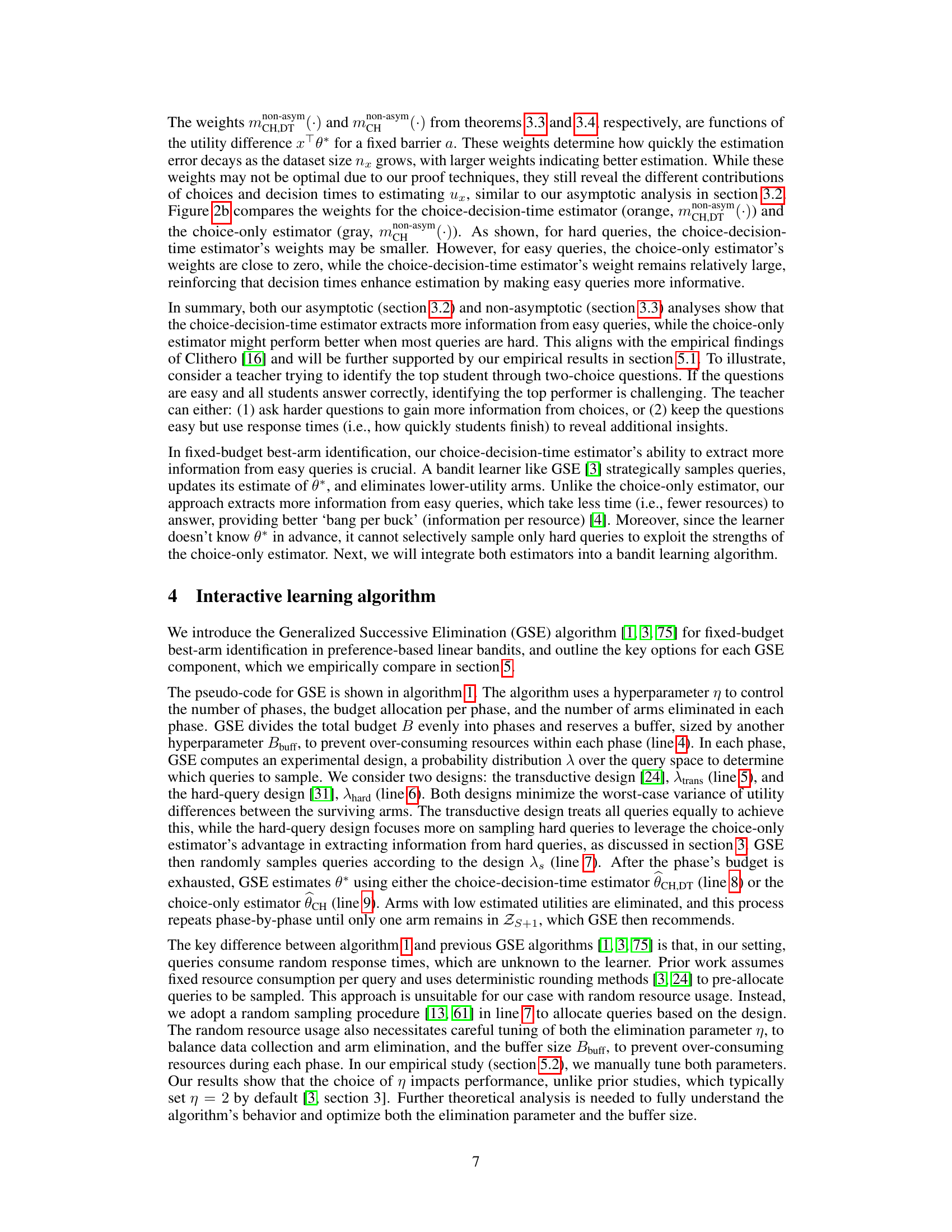

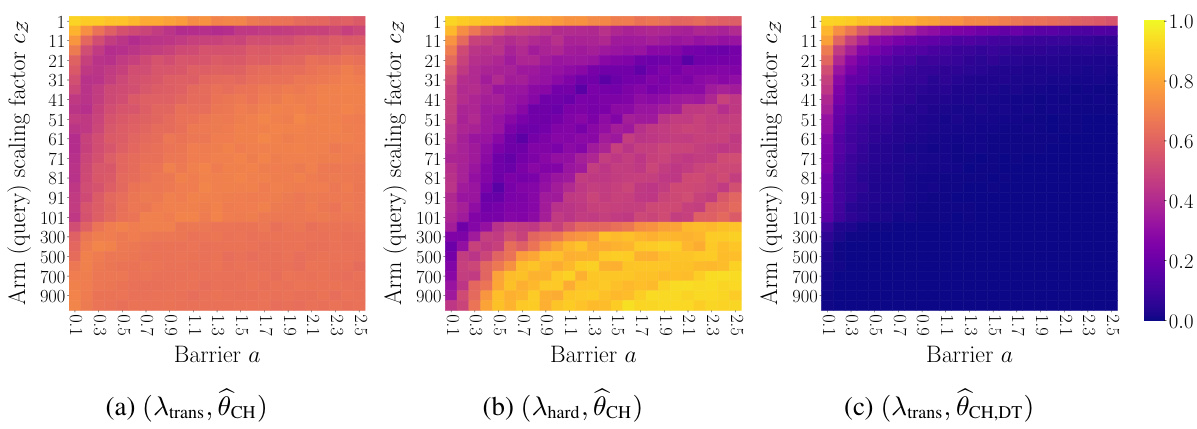

This figure compares the estimation performance of three GSE variations using synthetic data. The x-axis represents the barrier a, and the y-axis represents the scaling factor cz. Each heatmap shows the error probability of incorrectly identifying the best arm. The results demonstrate that the choice-decision-time estimator consistently outperforms the choice-only estimator, especially when queries are easy (high cz).

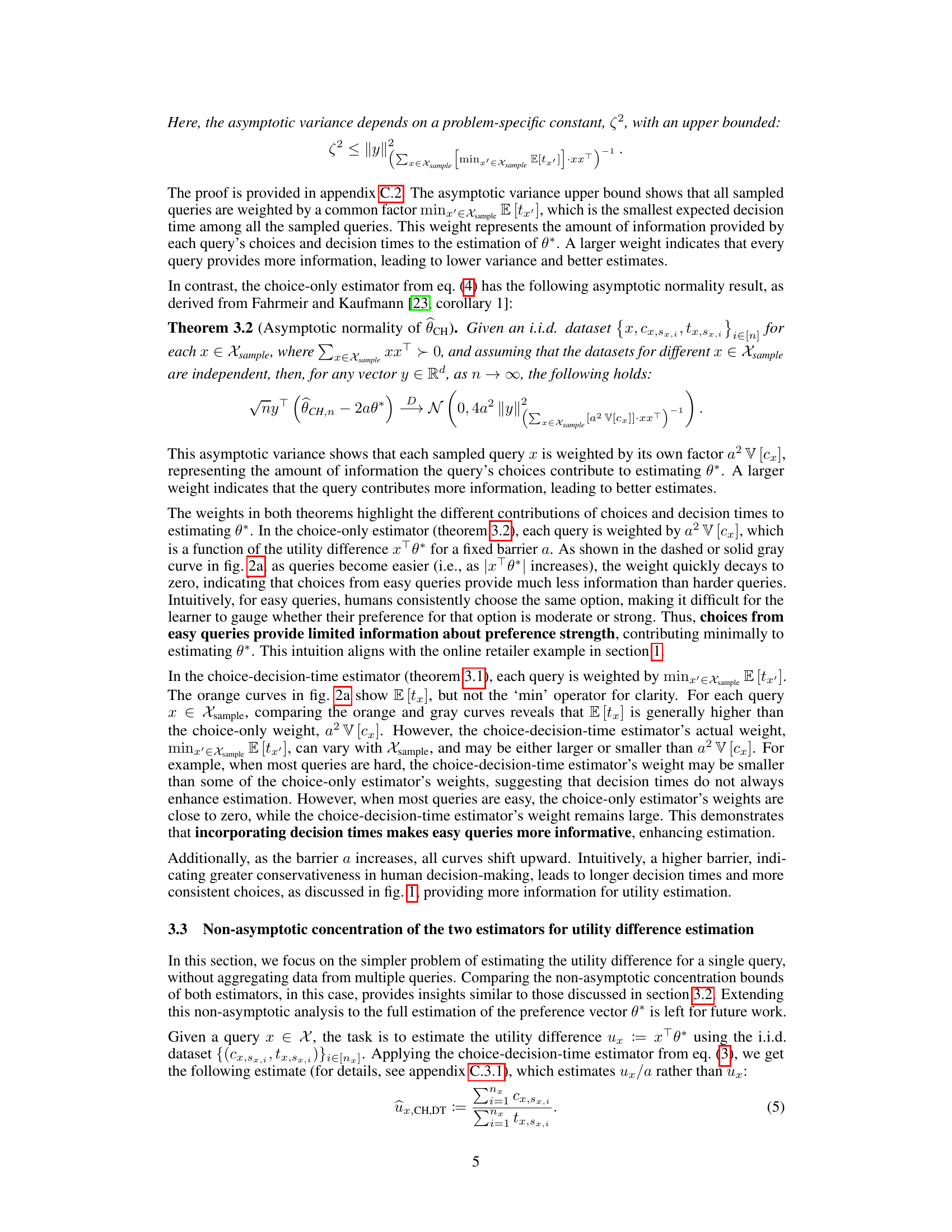

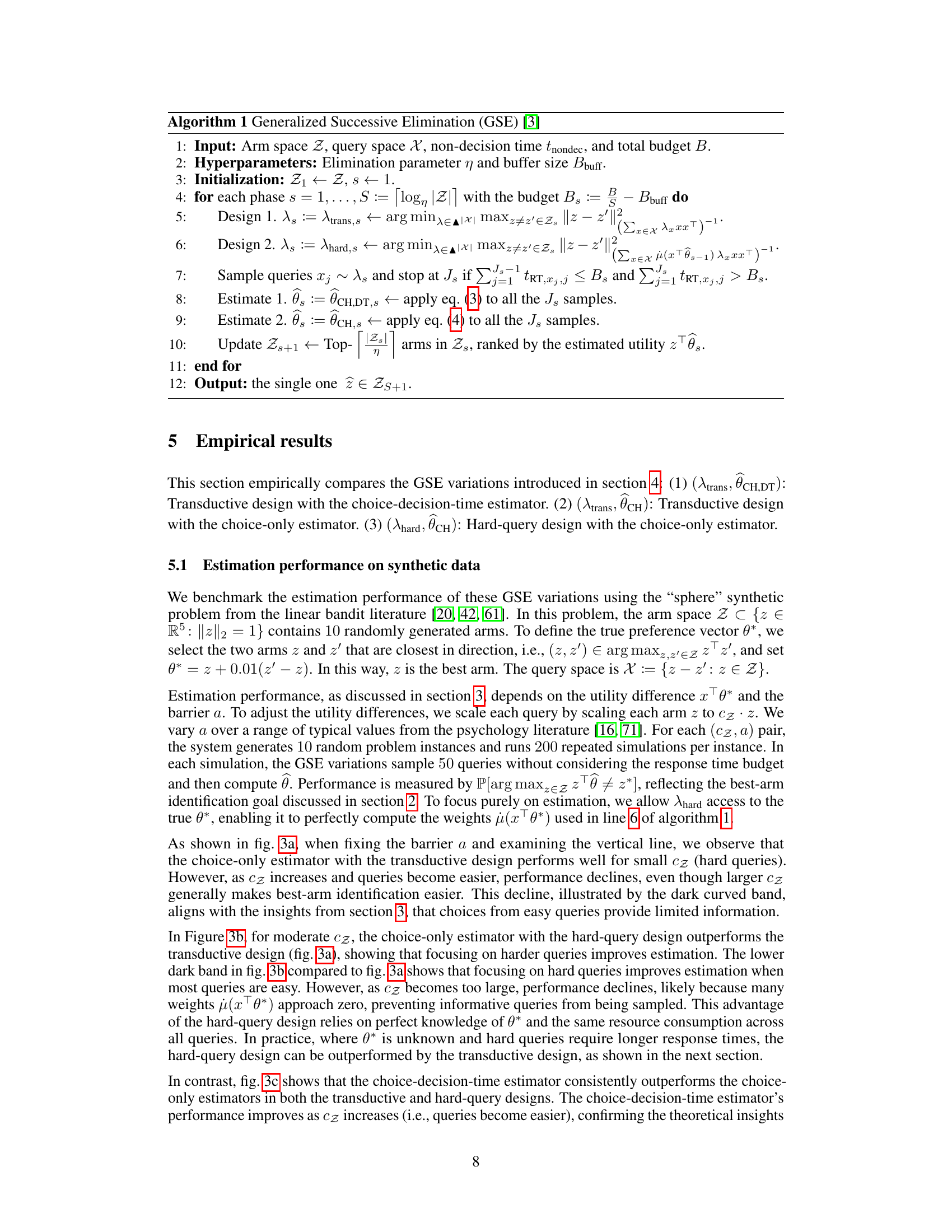

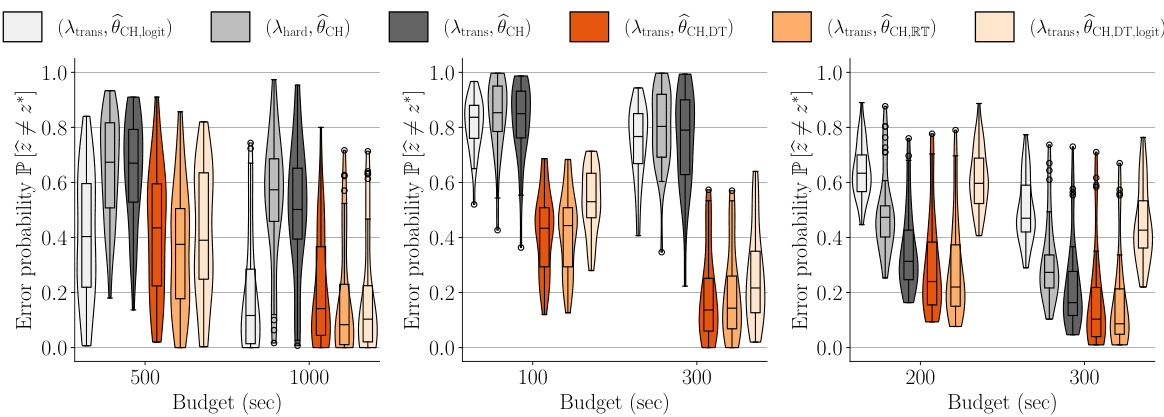

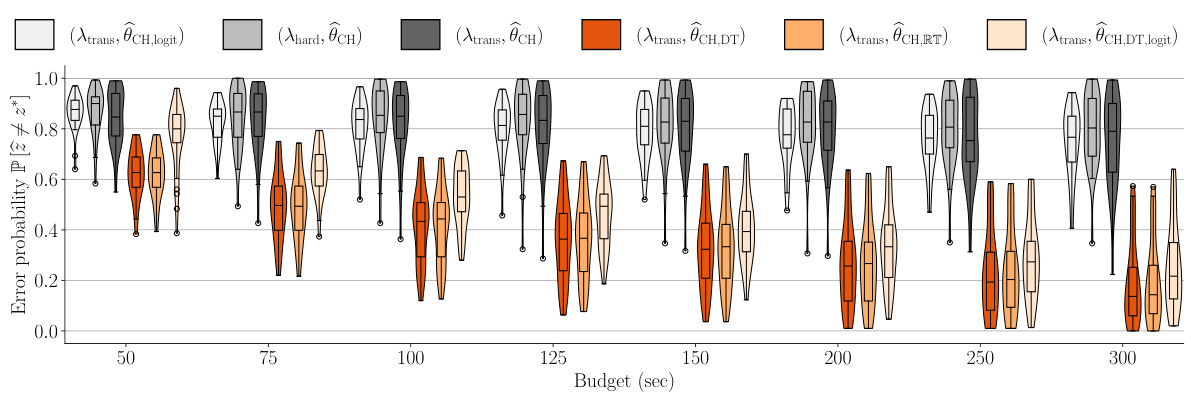

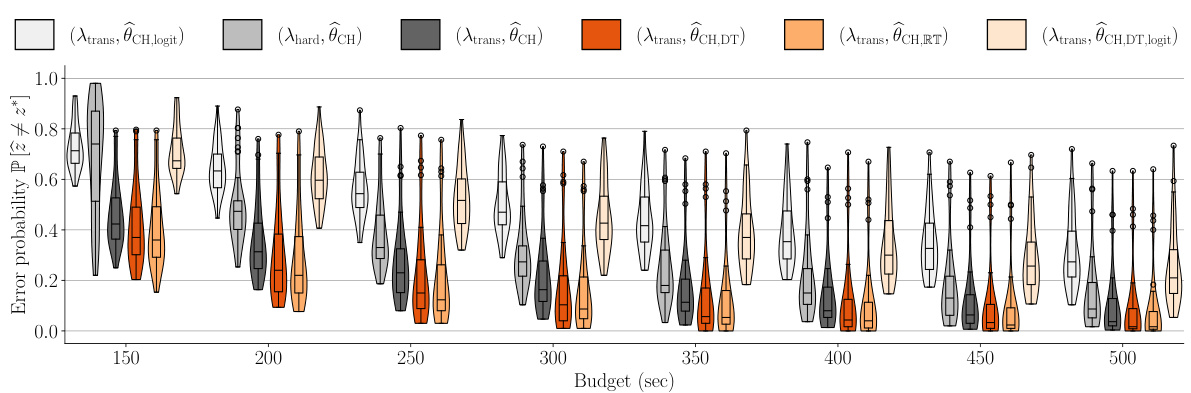

Figure 4 presents the best-arm identification error probability for six GSE variations across three datasets and two budgets. Each plot shows violin and box plots summarizing error probabilities from 300 simulations, with error bars illustrating the range and distribution of results. The variations represent different combinations of experimental design and utility estimator.

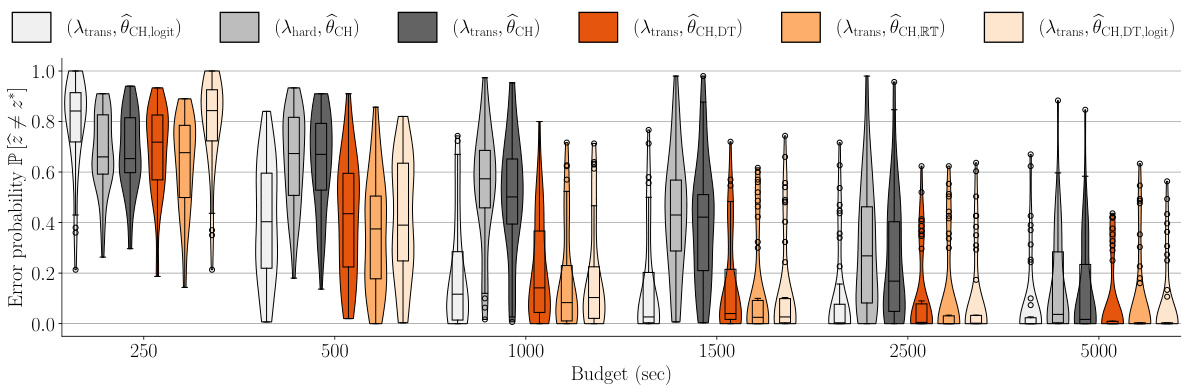

This figure shows the best-arm identification error probability as a function of budget for six different GSE variations using the food-risk dataset. Violin plots and box plots are used to show the distributions of error probabilities. The results indicate that the choice-decision-time estimator consistently outperforms the choice-only estimators in the task.

This figure compares the performance of three GSE variations in estimating human preferences (θ*) from synthetic data. The three variations differ in their approach to using response times (choice-decision-time estimator vs. choice-only estimator) and the query selection strategy (transductive vs hard-query design). The heatmaps show the error probability of identifying the best arm as a function of arm scaling factor (cz, representing query easiness) and decision barrier (a, representing human decision making conservativeness). The figure demonstrates that incorporating response times significantly improves estimation, especially when queries are easy (large cz).

This figure compares the performance of six different GSE variations on the food-risk dataset using a violin plot. The x-axis shows different budgets, and the y-axis shows the error probability. Each violin plot represents the distribution of error probabilities across multiple simulations for a specific GSE variation. The plot shows that incorporating response time into the estimator consistently outperforms the traditional choice-only estimators across various budgets.

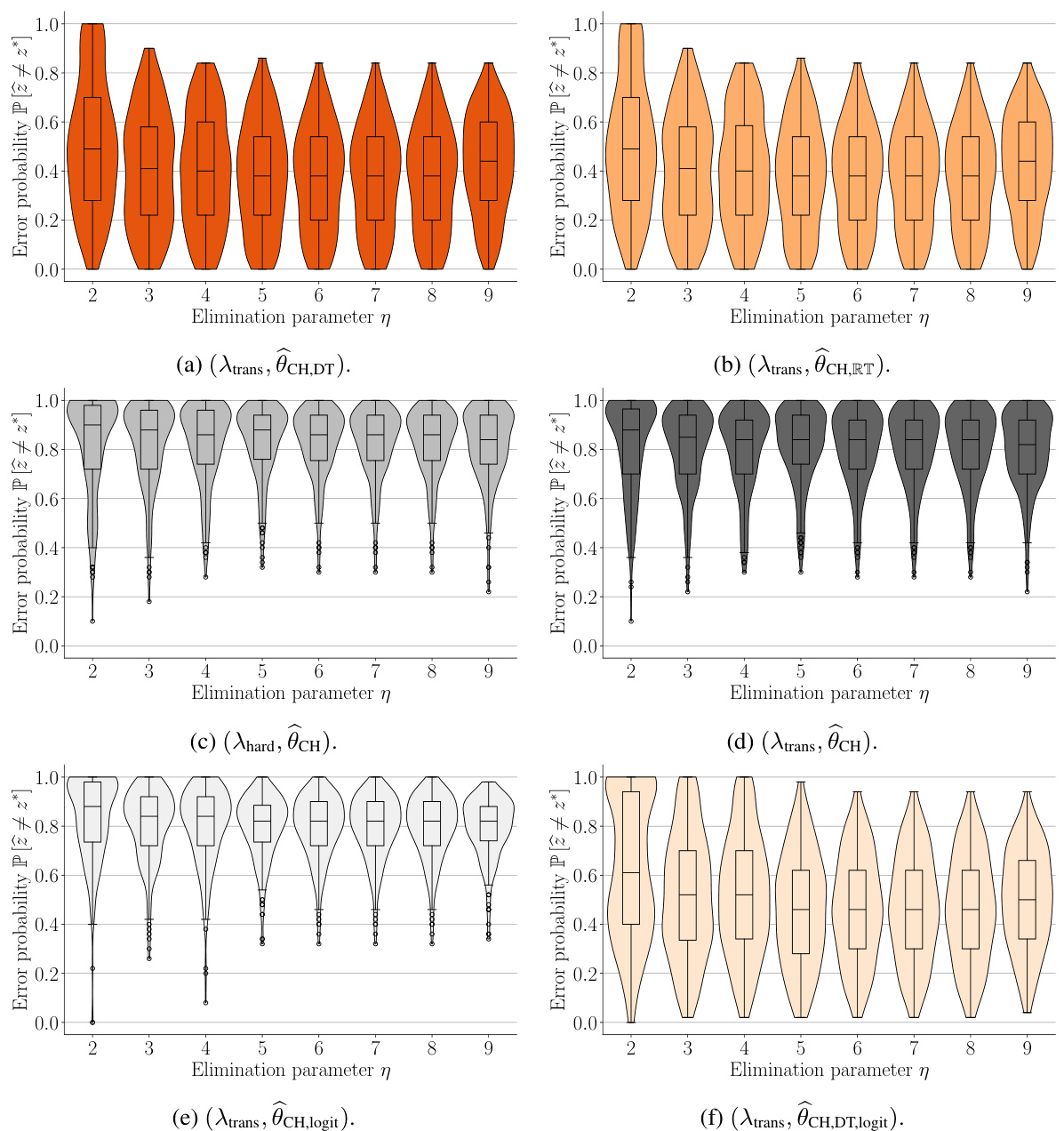

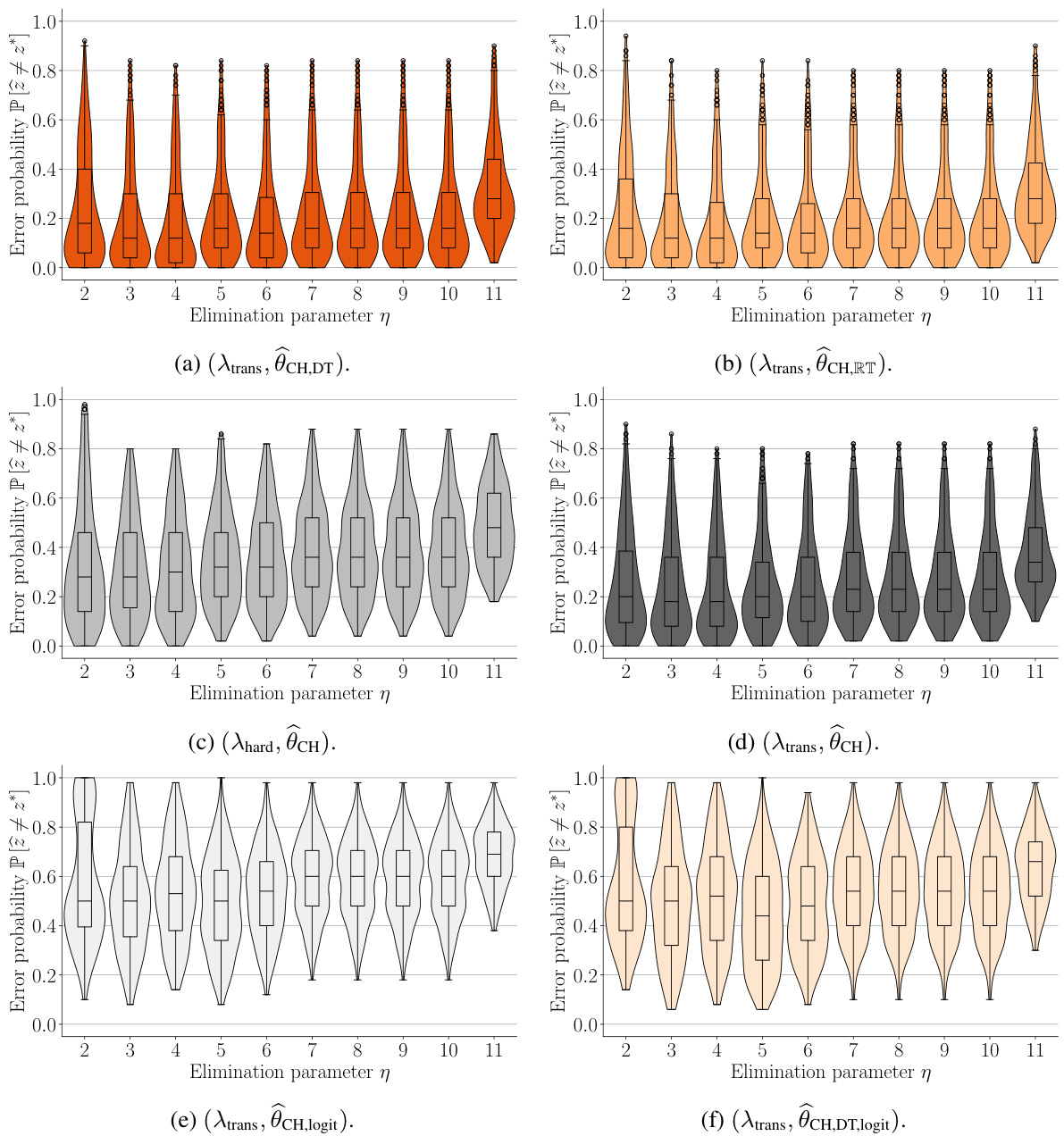

This figure shows the result of tuning the elimination parameter (η) in the GSE algorithm for six different variations. Each plot represents a different GSE variation and displays the best-arm identification error probability as a function of η. Violin plots show the distribution of errors and box plots summarize the central tendencies, offering insights into the effectiveness of the various GSE setups for different η values and offering the best choice of η for each algorithm. The data is from the snack dataset with choices (-1 or 1) [39].

Figure 5 shows the best-arm identification error probability across different GSE variations for varying budgets. The violin plots and overlaid box plots illustrate the distribution of error probabilities across multiple simulations. It is based on the food-risk dataset and displays the performance of various algorithms at different time budgets for identifying the best arm.

Full paper#