↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional physics simulators struggle with large-scale scenes due to the computational cost of rigid-body interactions, especially collision detection. Learned simulators offer an alternative, but existing methods based on meshes scale poorly to scenes with many objects or detailed shapes. This limits their application in robotics, computer graphics, and other domains requiring realistic simulations of complex environments.

This work introduces SDF-Sim, a new learned rigid-body simulator that addresses these limitations. SDF-Sim uses learned signed distance functions (SDFs) to represent object shapes and optimize collision detection. This approach significantly reduces computational costs and memory requirements, enabling simulations with hundreds of objects and millions of nodes. The results demonstrate that SDF-Sim achieves state-of-the-art scalability and accuracy, outperforming existing learned simulators on large-scale benchmarks. Furthermore, SDF-Sim successfully simulates real-world scenes reconstructed from images, showcasing its potential in bridging the sim-to-real gap.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in robotics, computer graphics, and AI. It significantly advances the scalability of learned simulators, a critical area for complex simulations. The techniques presented open new avenues for research in large-scale scene modeling and sim-to-real transfer, impacting various applications.

Visual Insights#

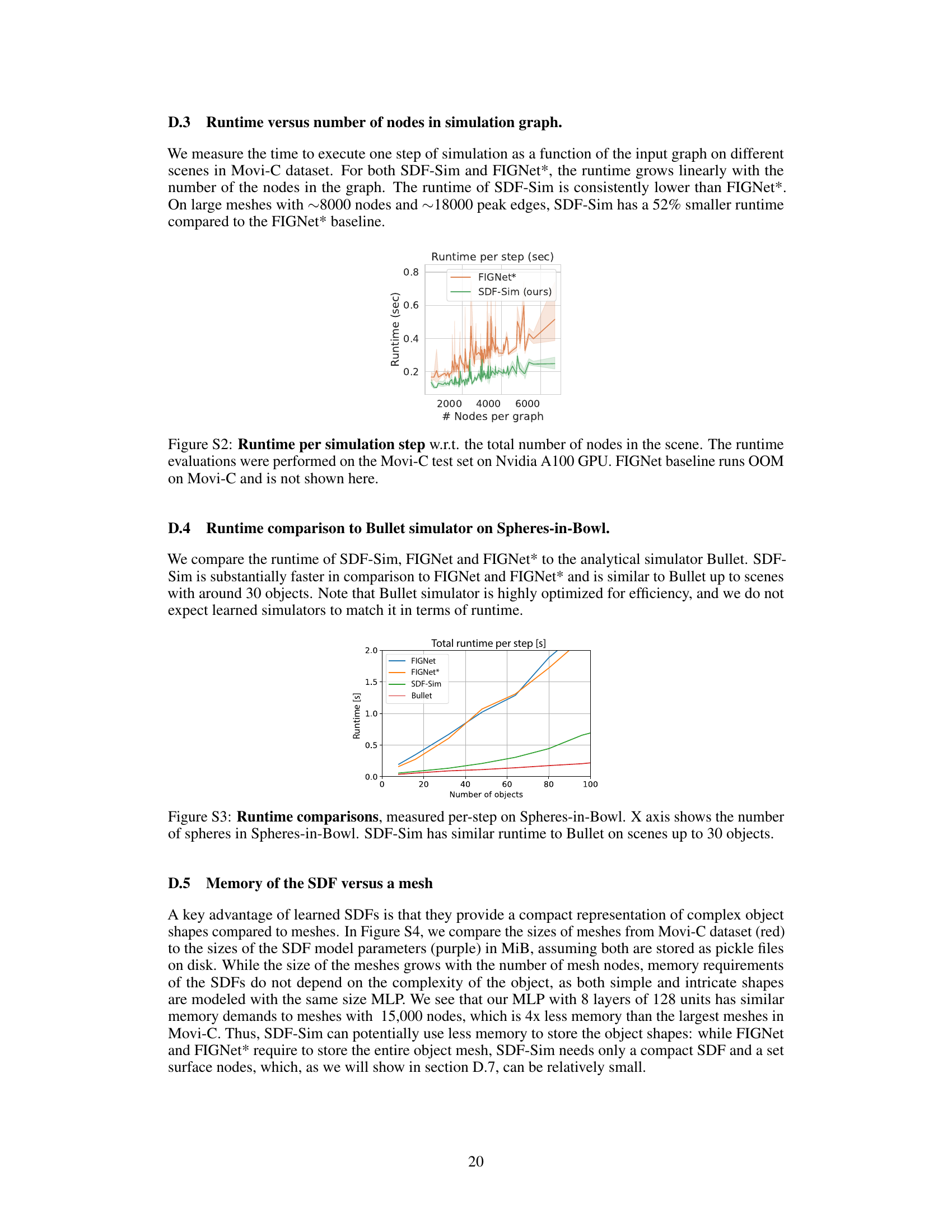

This figure shows a schematic overview of the SDF-Sim pipeline. It starts with objects represented as learned signed distance functions (SDFs). Each SDF is parameterized by a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) that implicitly defines the object’s shape and distance field. These SDFs are then fed into a graph neural network (GNN)-based simulator, which predicts the object’s dynamics (position, rotation, etc.) for the next simulation step, showing how the SDF representation allows the model to predict the next timestep given the current SDFs and object states.

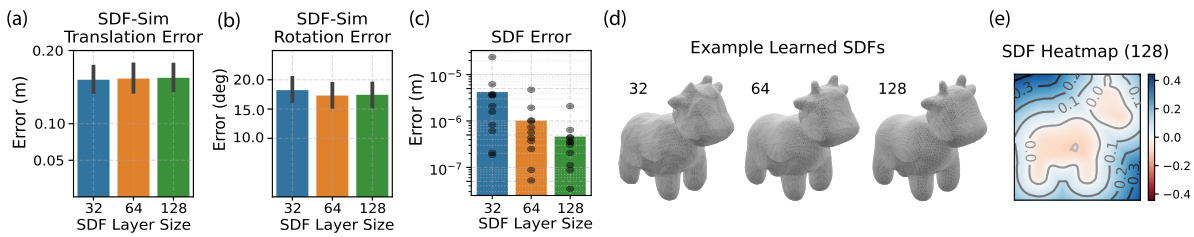

This table presents the average and maximum number of nodes and triangles for each object type in the Movi-B and Movi-C datasets from the Kubric benchmark. These meshes are used specifically for collision detection during simulation, and are different from the detailed meshes used for training the SDFs (Table 1). The difference in mesh complexity highlights the need for efficient collision detection methods like those employing SDFs.

In-depth insights#

SDF-Sim: A Novel Approach#

SDF-Sim introduces a novel approach to rigid-body simulation by leveraging learned signed distance functions (SDFs) within a graph neural network (GNN) framework. This approach significantly addresses limitations of prior learned simulators, which often struggle with scalability due to mesh-based representations. SDF-Sim’s key innovation lies in representing object shapes implicitly via learned SDFs. This drastically reduces the computational cost associated with collision detection and distance queries, enabling the simulation of scenes with hundreds of objects and millions of nodes—a significant leap in scale compared to existing methods. The use of learned SDFs allows for efficient distance computations in constant time, regardless of object complexity. Furthermore, SDF-Sim’s architecture, coupled with a carefully designed graph structure, further enhances efficiency and scalability. Its ability to handle large-scale scenarios opens doors for applications in robotics, computer vision, and game development that were previously computationally prohibitive. While the methodology demonstrates impressive scaling and accuracy, future work could explore techniques to further enhance the accuracy of learned SDFs and broaden the types of interactions supported.

Learned Physics at Scale#

The concept of “Learned Physics at Scale” represents a significant advancement in simulating complex physical systems. Traditional physics engines often struggle with large-scale simulations due to computational constraints and the difficulty of precisely modeling intricate interactions. Learning-based approaches offer a potential solution, leveraging the power of machine learning to approximate physical dynamics from data. This approach can potentially address the limitations of hand-crafted models, enabling simulations with vastly more objects and detail than previously feasible. However, challenges remain. Data requirements for training such models can be substantial, and ensuring generalizability across diverse scenarios is crucial. Furthermore, interpreting and debugging learned models is complex, and transparency in decision-making is essential for trust in simulation results. Successfully navigating these challenges will be key to realizing the full potential of learned physics in large-scale applications.

Collision Handling via SDFs#

This section would detail how the authors leverage Signed Distance Functions (SDFs) to efficiently handle collisions in their learned rigid-body simulator. A key advantage of SDFs is their ability to quickly compute distances between objects, avoiding the computational bottleneck of traditional mesh-based collision detection methods which scale poorly with the number of objects. The authors likely describe how they use learned SDFs, possibly trained from images or meshes, to represent object shapes implicitly. This implicit representation allows for constant-time distance queries, regardless of object complexity. The discussion might then explore the specific algorithmic approach used to detect and resolve collisions using these SDFs, perhaps detailing how they create and use a graph network to model interactions, or highlighting any techniques used to optimize performance and scalability. Efficiency is paramount, given the aim to handle large-scale scenes with numerous objects. The methodology will likely involve efficient collision detection techniques adapted for SDFs, and a robust system for handling collision impulses to ensure realistic and stable simulations.

Vision-Based Simulation#

Vision-based simulation represents a significant advancement in the field of computer graphics and robotics, aiming to bridge the gap between simulated and real-world environments. This approach leverages computer vision techniques to capture real-world scenes and their dynamics, then uses this data to create and control simulations. The key advantage is the ability to directly learn physical properties and interactions from real-world data, mitigating the limitations of hand-crafted models that often fail to accurately reflect complex real-world phenomena. However, challenges remain. Accurately capturing 3D geometry from 2D images or videos is computationally demanding and subject to error, impacting the realism of the simulation. Robustness to noise, occlusion, and variations in lighting conditions are crucial for successful vision-based simulation. Furthermore, processing real-world sensor data for large-scale or high-fidelity simulations necessitates considerable computational power and efficient algorithms. Despite these limitations, the ability to create physically-accurate and data-driven simulations makes vision-based simulation a promising area of research with far-reaching implications for robotics, autonomous systems, and training environments.

Limitations and Future#

The research paper’s limitations primarily revolve around the reliance on pre-trained SDFs, which require individual training for each object, creating a potential bottleneck for large-scale applications. The need for pre-trained SDFs introduces a computational overhead and limits the ease of integration of new objects. Furthermore, although the method shows impressive scaling capabilities, future work could explore optimization techniques to further enhance efficiency. Generalization to more complex scenarios, including flexible and articulated objects or multi-physics interactions (e.g., fluid-rigid body coupling), would be a significant next step. Finally, while the paper demonstrates promising accuracy, exploring methods to further refine the accuracy of the simulation, particularly in handling complex collisions, will be crucial for expanding applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

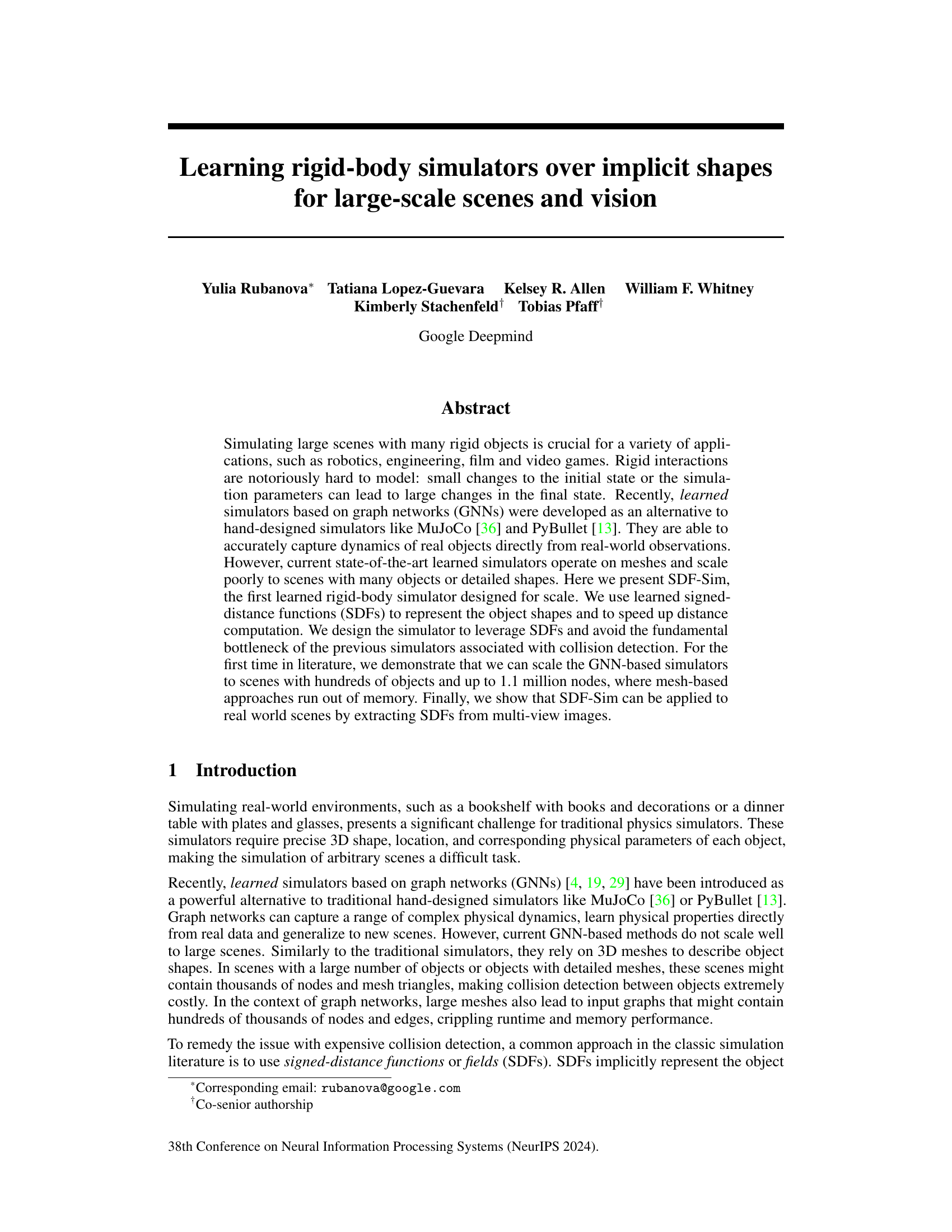

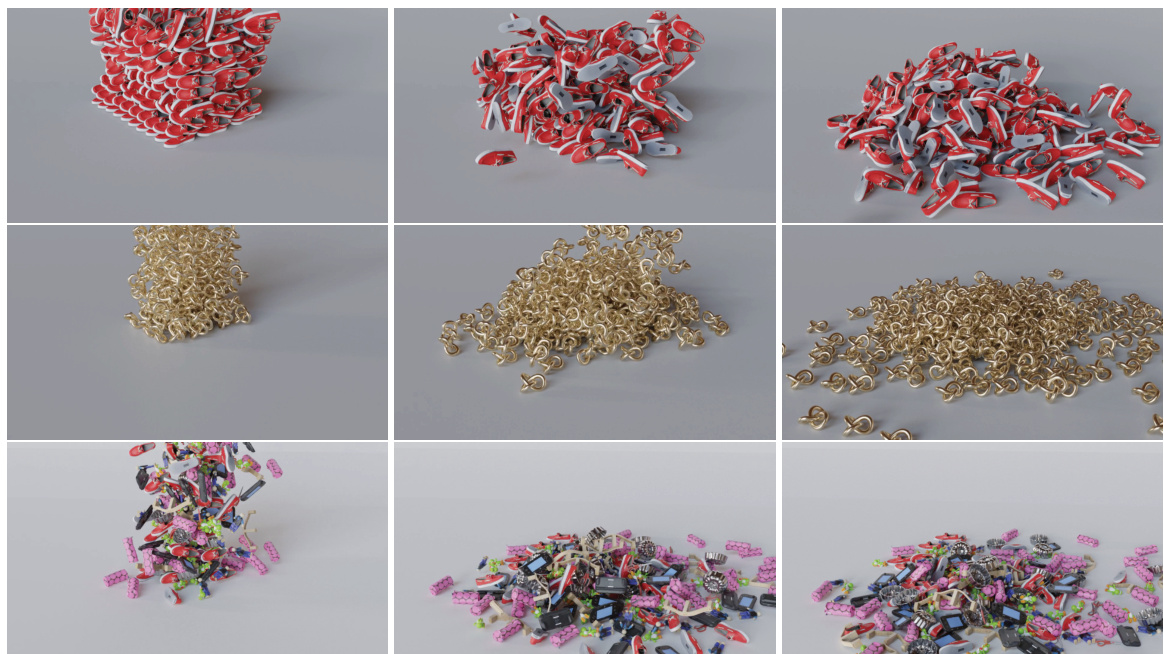

This figure showcases three large-scale simulations produced by SDF-Sim, each with a different set of objects and a high number of nodes. The top panel shows 300 shoes falling onto a floor; the middle panel displays 270 knots in a similar setting; and the bottom panel presents 380 diverse objects. These simulations demonstrate SDF-Sim’s scalability to extremely large scenes (up to 1.1 million nodes), a significant advancement compared to previous learned simulators which struggle at far fewer nodes. The provided URL links to videos showing these simulations.

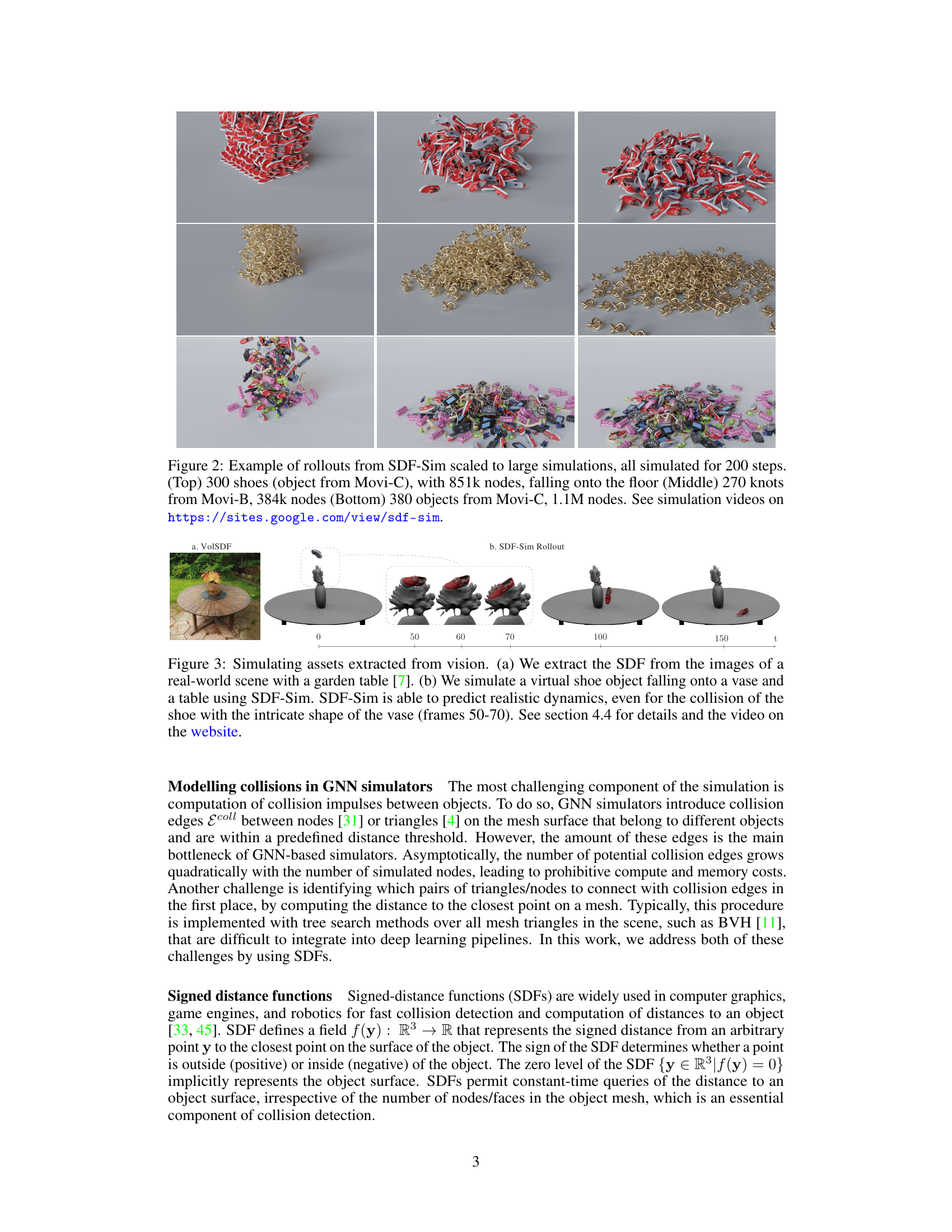

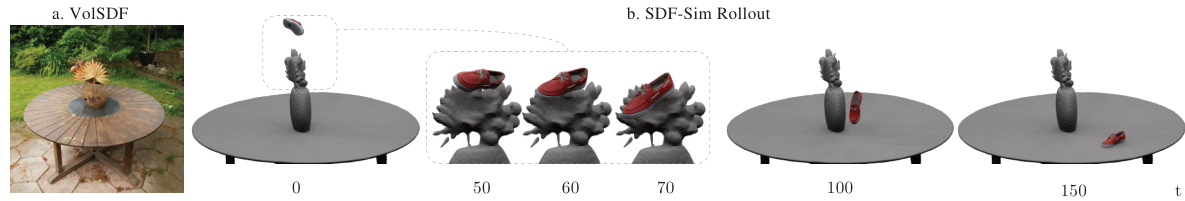

This figure shows the application of SDF-Sim to real-world scenes by extracting SDFs from images. Panel (a) displays a real-world scene with a garden table, which was used to extract the SDFs. Panel (b) shows the simulation results, demonstrating how the learned SDF-Sim model accurately simulates a shoe falling onto a vase and a table, even capturing complex interactions with the vase’s shape.

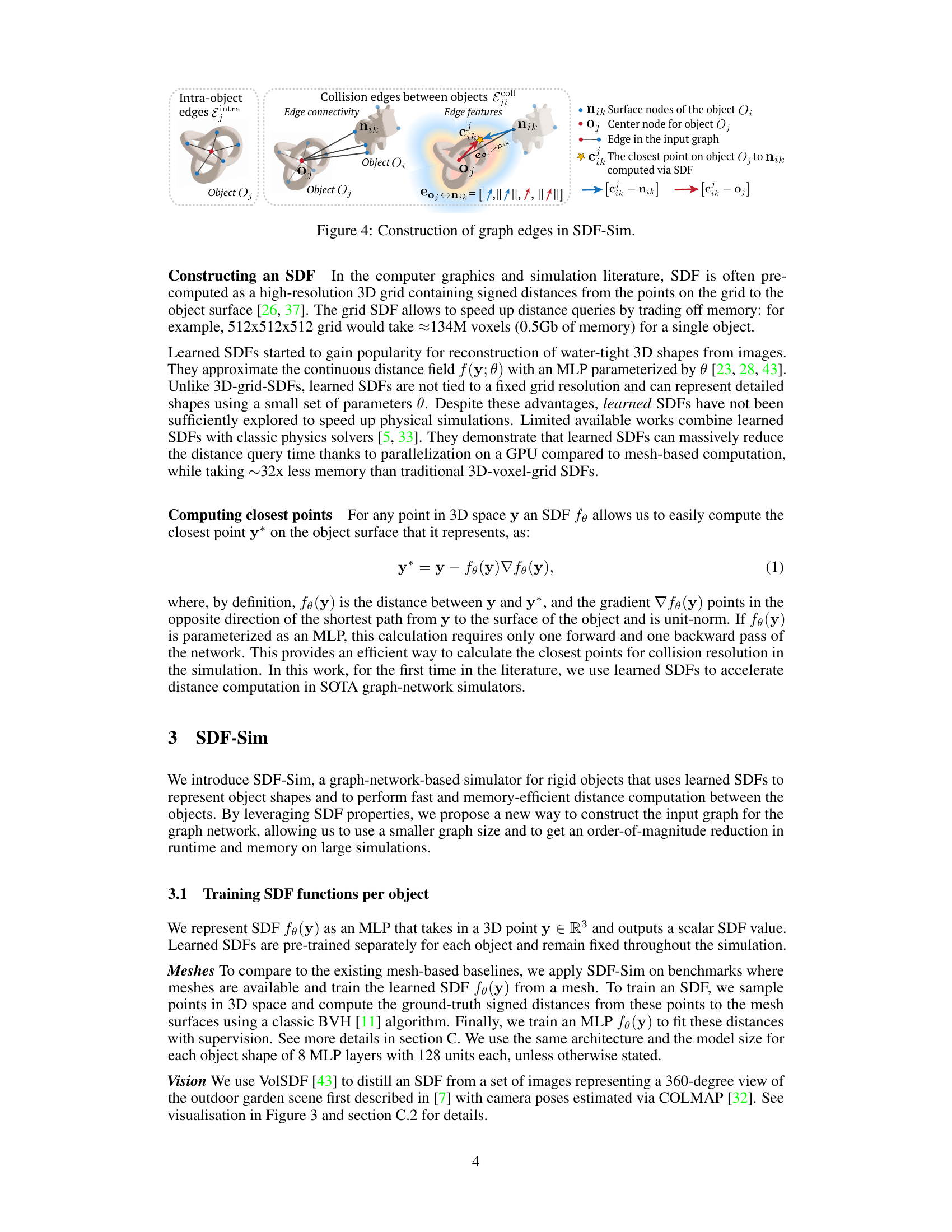

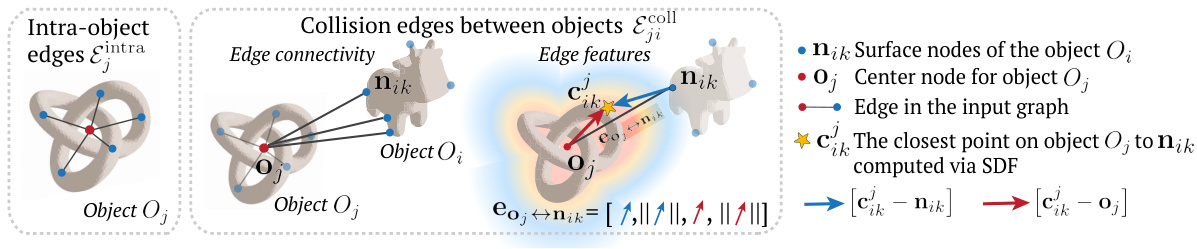

The figure illustrates the construction of graph edges in the SDF-Sim architecture. It shows how intra-object edges connect surface nodes to the object’s center node, while inter-object (collision) edges connect surface nodes of different objects if they are within a certain distance threshold, as determined by the SDF. Edge features, which include distances and relative positions, are also detailed. This efficient graph construction avoids the quadratic complexity of traditional mesh-based methods for collision detection, making SDF-Sim scalable to large scenes.

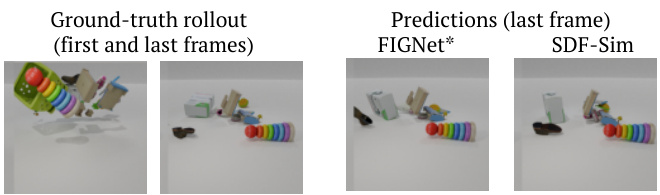

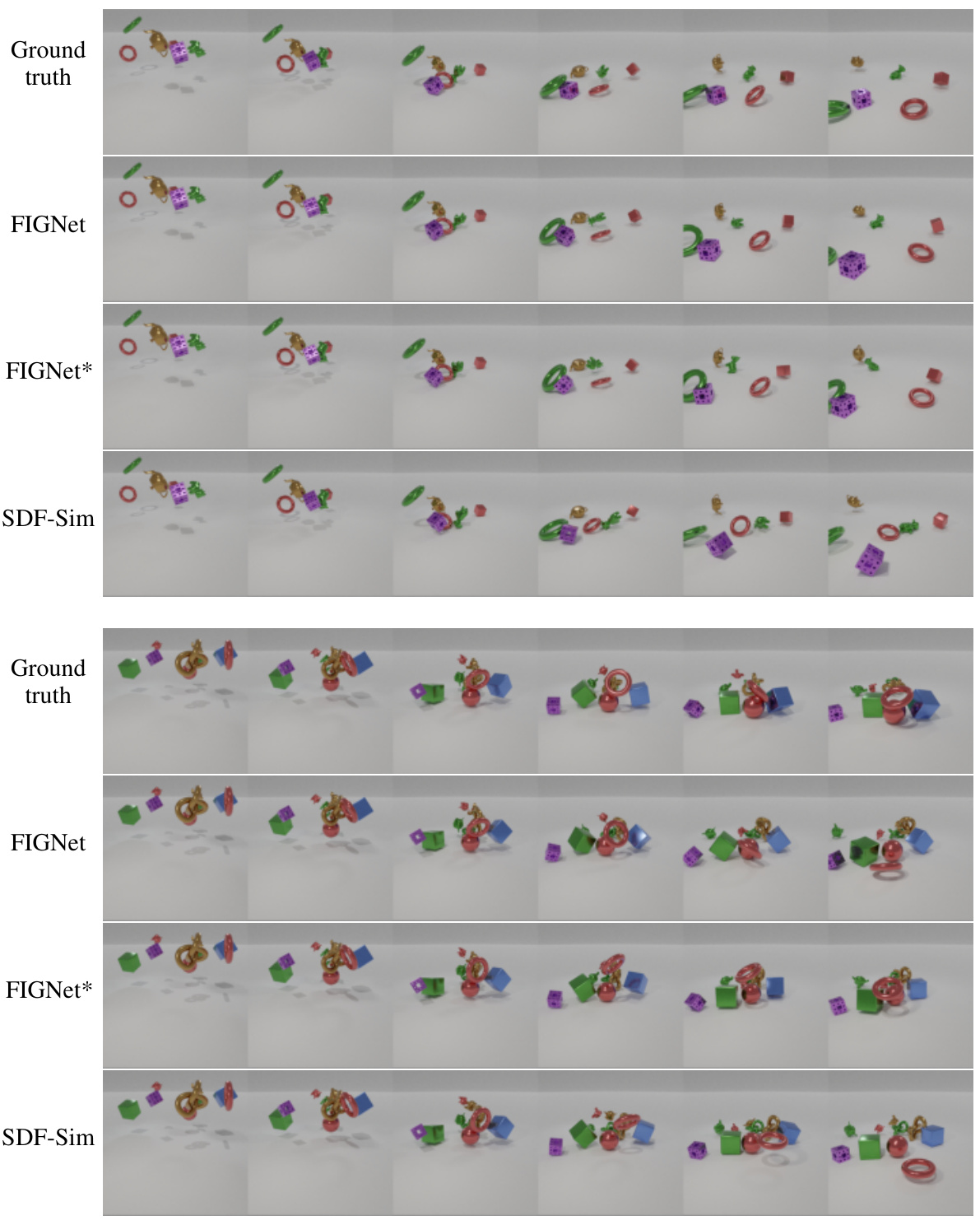

This figure compares the last frames of simulations generated by FIGNet*, a state-of-the-art learned simulator based on mesh, and SDF-Sim, a novel learned simulator using SDFs, against the ground truth. It highlights the accuracy of SDF-Sim in predicting the final state of a scene, demonstrating its ability to capture complex dynamics involving multiple objects.

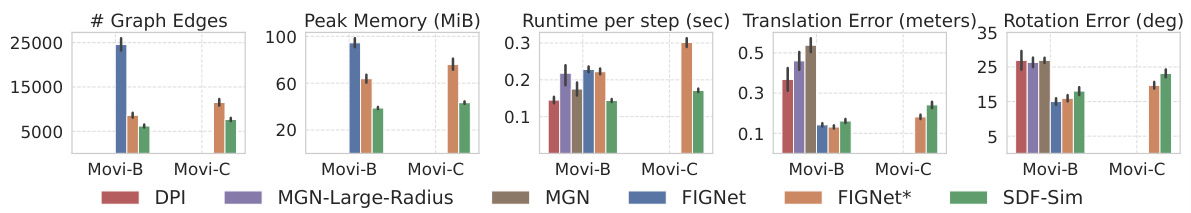

This figure compares the performance of SDF-Sim with several mesh-based baselines (DPI, MGN, MGN-Large-Radius, FIGNet, FIGNet*) on the Movi-B and Movi-C benchmark datasets. It shows the number of graph edges, peak memory usage, runtime per step, translation error, and rotation error for each method. The results highlight that SDF-Sim achieves comparable accuracy with significantly reduced memory consumption and faster runtime, especially on the larger Movi-C dataset where many baselines run out of memory.

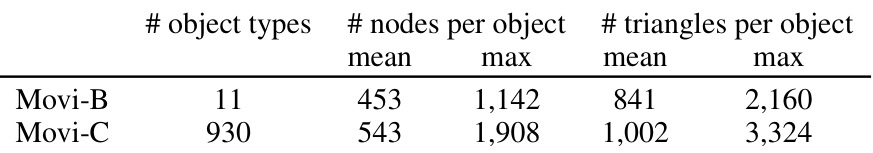

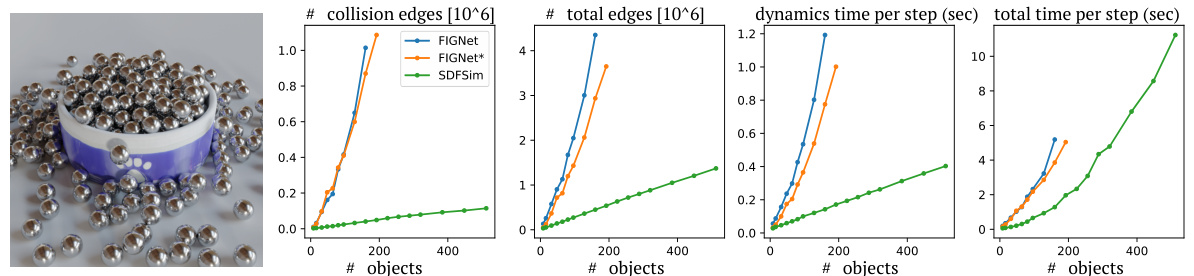

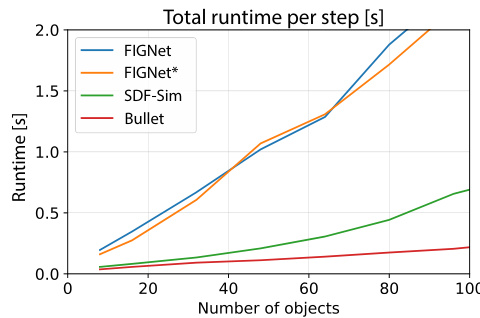

This figure demonstrates the scalability of SDF-Sim compared to other methods (FIGNet and FIGNet*) for large-scale simulations. The left panel shows a simulation with 512 spheres. The right panel plots the number of edges and runtime against the number of spheres. It highlights that SDF-Sim uses significantly fewer edges and has much faster runtime, especially as the number of spheres (and hence complexity) increases, allowing it to handle large-scale simulations where other methods fail due to memory limitations.

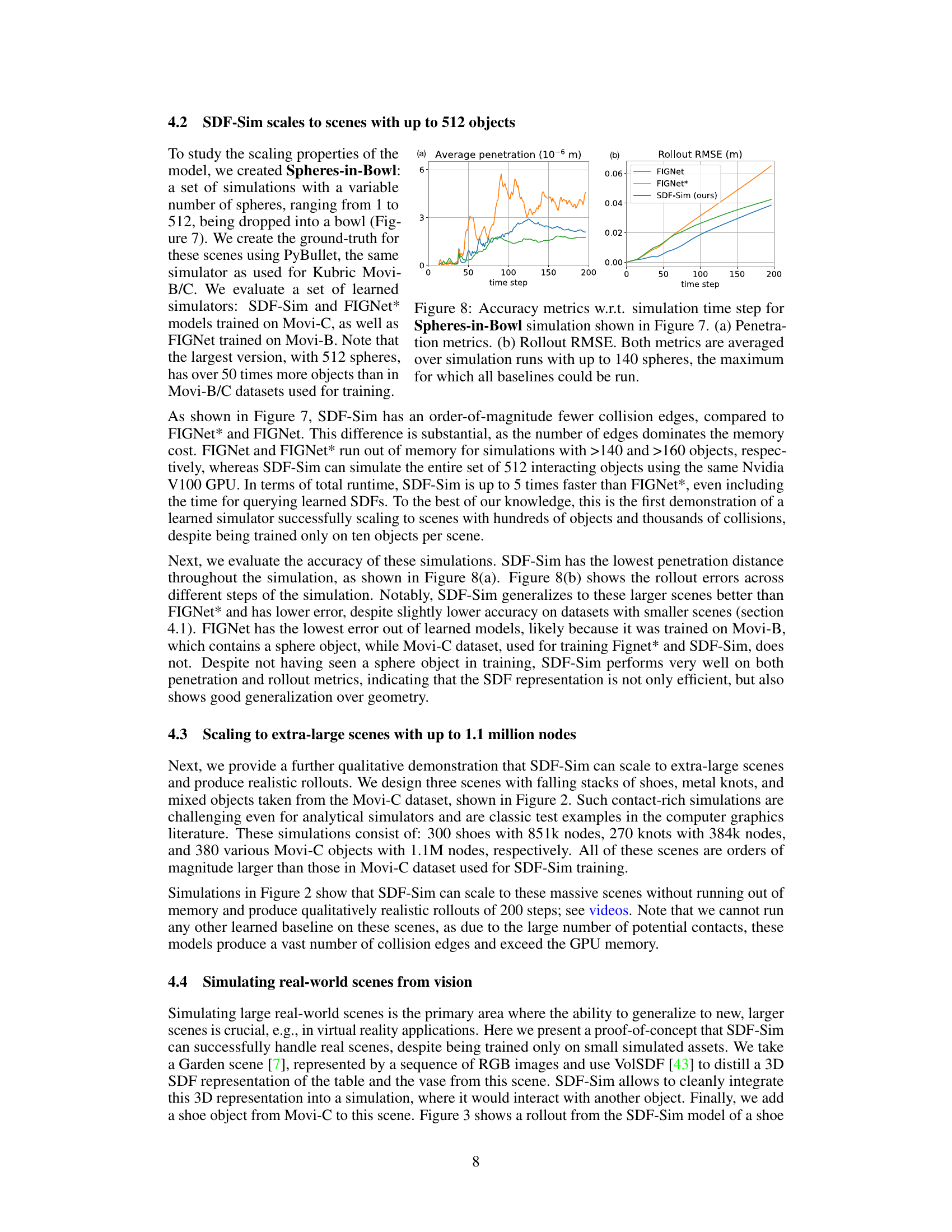

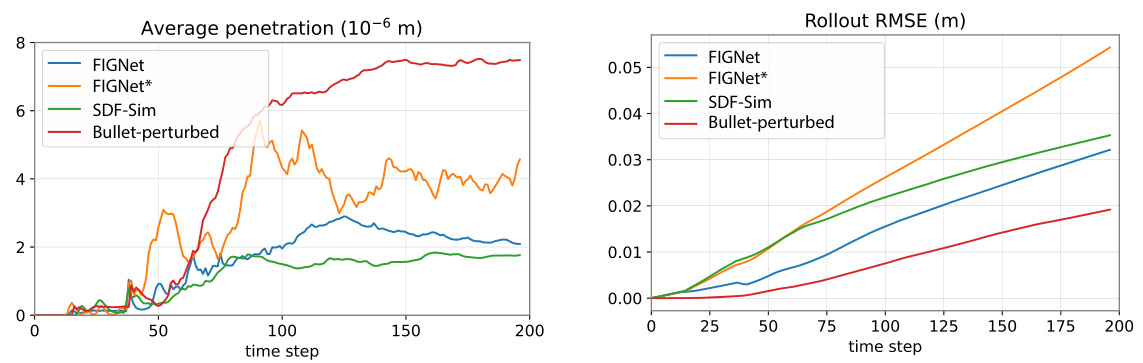

This figure shows the accuracy of different methods in simulating the Spheres-in-Bowl scene. The left panel shows average penetration depth over time, while the right panel shows the root mean square error (RMSE) of the rollout compared to the ground truth. The results are averaged over simulations with up to 140 spheres, reflecting the scalability limitations of some methods.

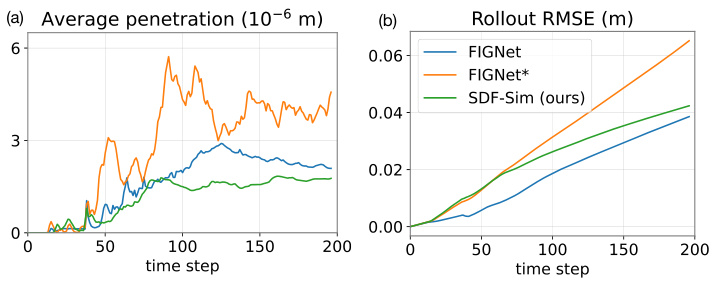

This figure shows an ablation study on the impact of learned SDF model size on the performance of SDF-Sim. It includes plots showing translation and rotation error for different SDF layer sizes, the mean squared error of predicted SDF estimates near the surface, visualizations of a cow shape reconstructed with different SDF sizes, and a cross-section of a learned SDF heatmap.

This figure compares the performance of SDF-Sim against other methods (DPI, MGN, MGN-Large-Radius, FIGNet, FIGNet*) on the Movi-B and Movi-C benchmarks in terms of accuracy (translation and rotation error), memory usage (peak memory), and runtime (per step). It highlights that SDF-Sim achieves competitive accuracy while using significantly less memory and runtime, especially on the larger Movi-C dataset where many baselines run out of memory. The y-axis scales are different for each metric to better present the results.

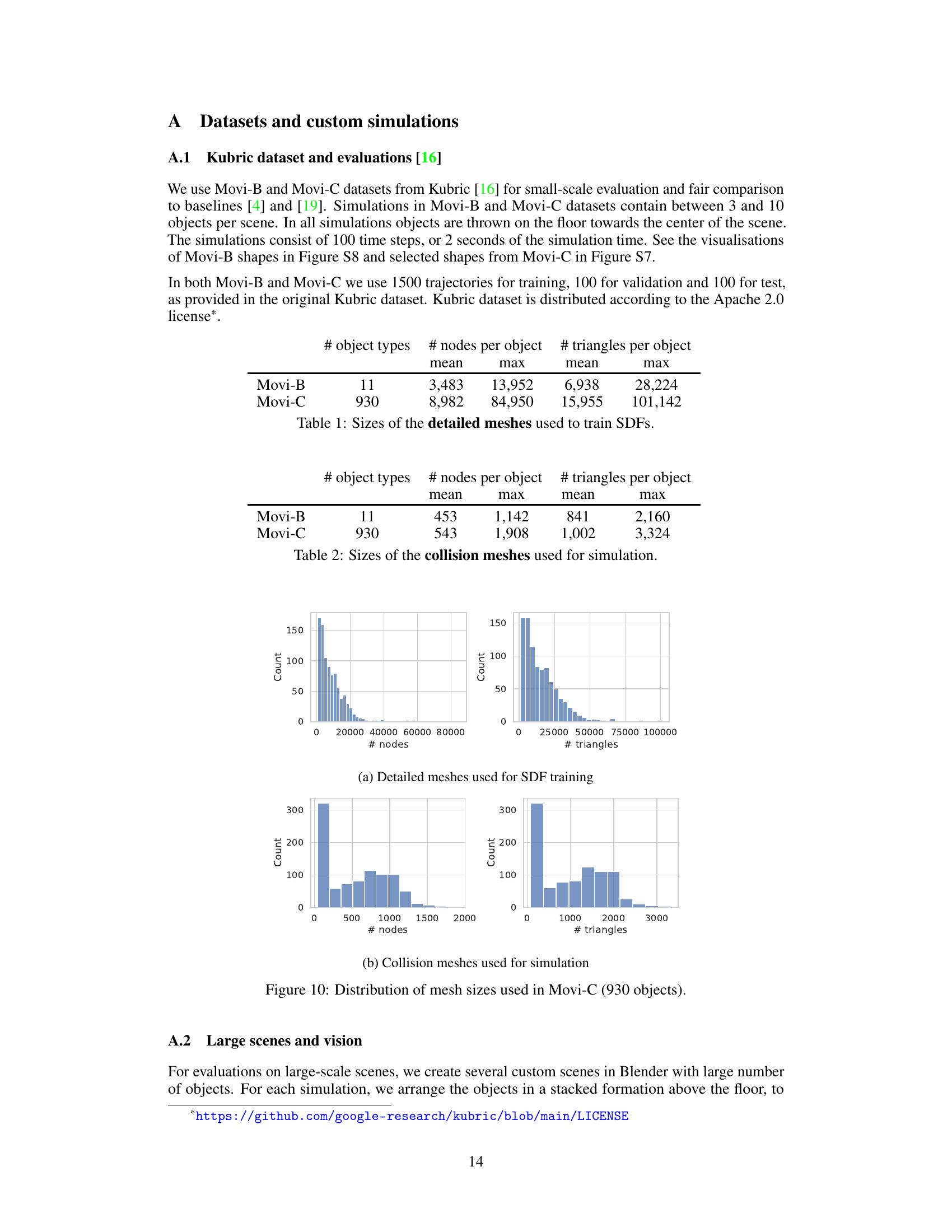

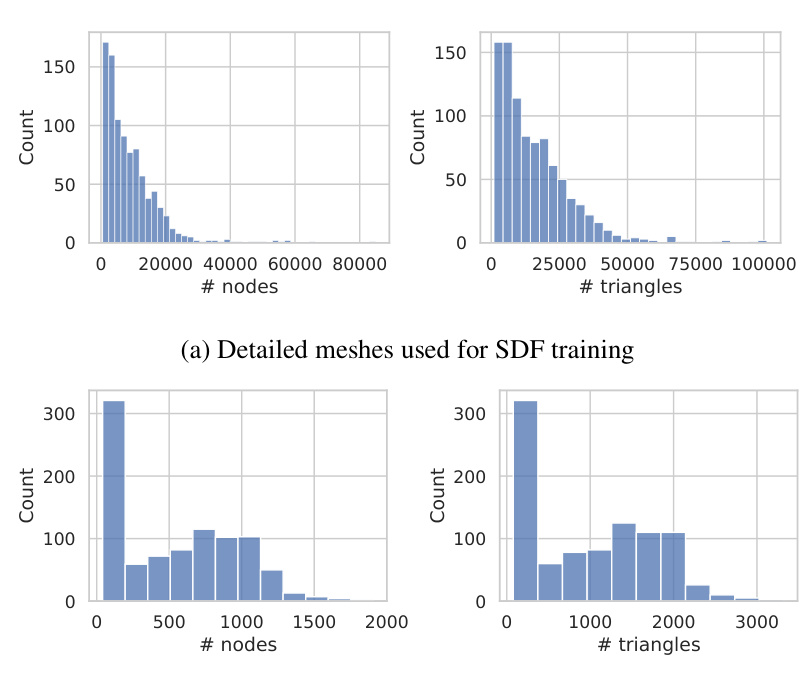

This figure shows the distribution of the number of nodes and triangles in the meshes used for training SDFs (left) and simulation (right) for the Movi-C dataset from the Kubric benchmark. The plots reveal that the meshes used for training are significantly larger and more complex, with a longer tail in the distribution, compared to the meshes used in the simulation itself. This difference is important because the complexity of the meshes directly influences the computational cost of traditional physics simulation and the memory usage of learned simulators like FIGNet. The SDF-Sim approach, which leverages implicit shape representations (SDFs), avoids this computational bottleneck.

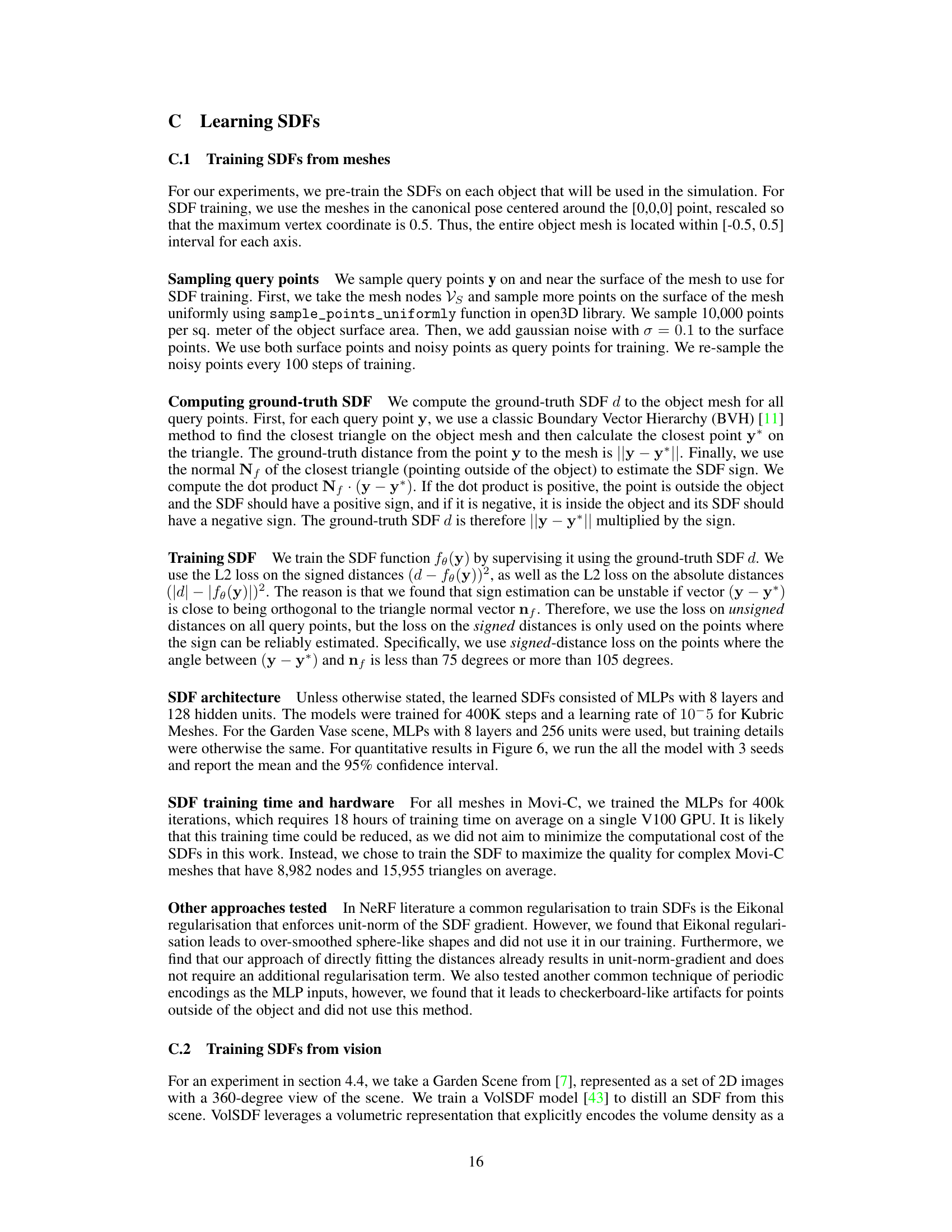

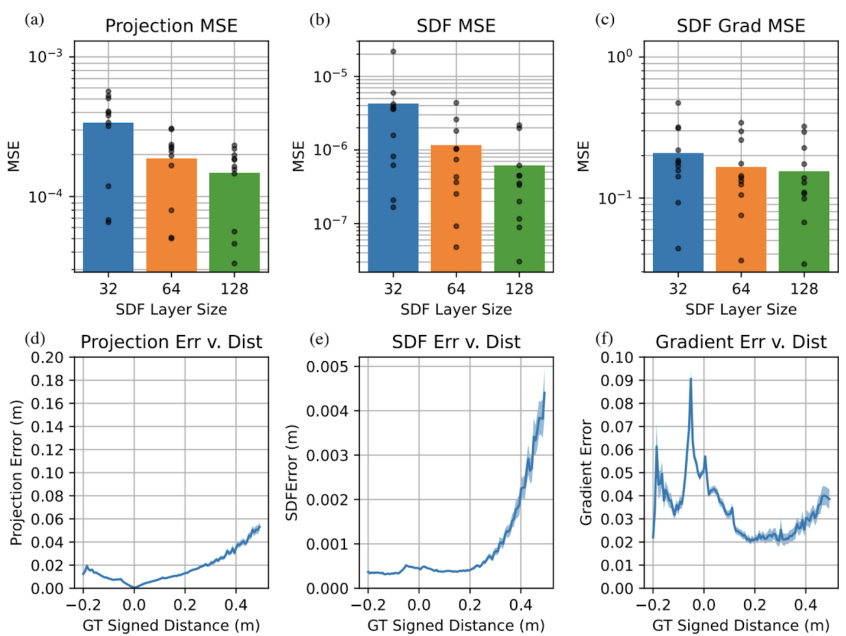

Figure S1 presents additional metrics evaluating the quality of learned Signed Distance Functions (SDFs) used in SDF-Sim. The figure shows mean squared error (MSE) analyses for projection, SDF, and gradient values, comparing different SDF model sizes (32, 64, and 128 layers). It also provides visualizations demonstrating how these errors relate to the distance from an object’s surface. The results indicate that larger SDF models generally lead to improved accuracy, with errors remaining relatively low even near the object’s surface, despite increasing slightly with greater distances.

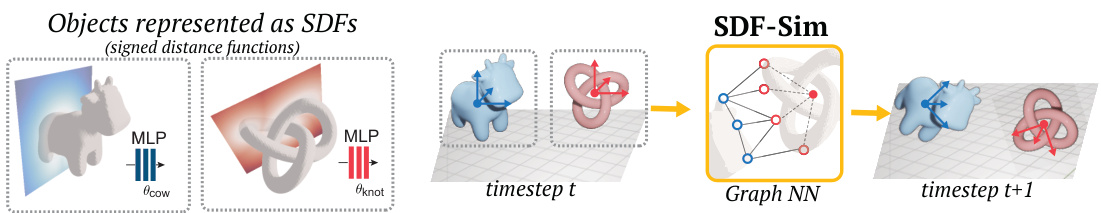

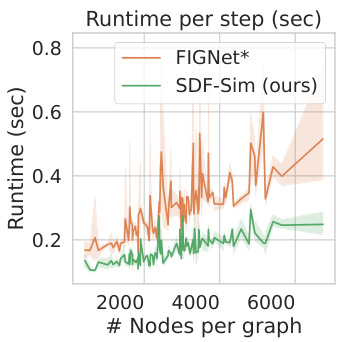

This figure shows the runtime per simulation step plotted against the total number of nodes in the scene’s graph for both SDF-Sim and FIGNet*. The results demonstrate that SDF-Sim consistently exhibits faster runtime compared to FIGNet*, especially as the number of nodes increases. The experiment was conducted using an Nvidia A100 GPU, and FIGNet ran out of memory (OOM) on the Movi-C dataset and is therefore excluded from the comparison.

This figure demonstrates the scalability of SDF-Sim compared to other methods (FIGNet, FIGNet*). The left panel shows a simulation with 512 spheres; the right shows how the number of edges and runtime scale with the number of spheres. SDF-Sim handles significantly more spheres and edges without running out of memory, unlike the other methods.

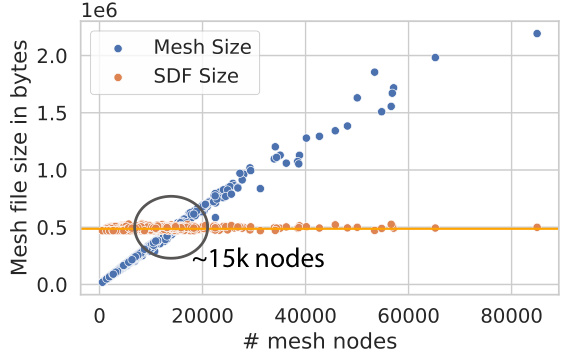

This figure compares the memory usage of storing mesh data versus storing the parameters of learned signed distance functions (SDFs). It shows that the memory footprint of meshes increases linearly with the number of nodes in the mesh, whereas the memory usage of SDFs remains relatively constant regardless of mesh complexity. A circle highlights that an SDF model requires roughly the same memory as a mesh with ~15,000 nodes. This demonstrates the compactness of SDF representations for objects compared to traditional mesh representations.

This figure compares the penetration and rollout RMSE for different simulators on the Spheres-in-Bowl dataset. It shows that SDF-Sim has lower penetration than the Bullet simulator (optimized for speed). Although the rollout error in SDF-Sim is higher than a perturbed Bullet simulation, it is lower than that of other learned simulators like FIGNet*.

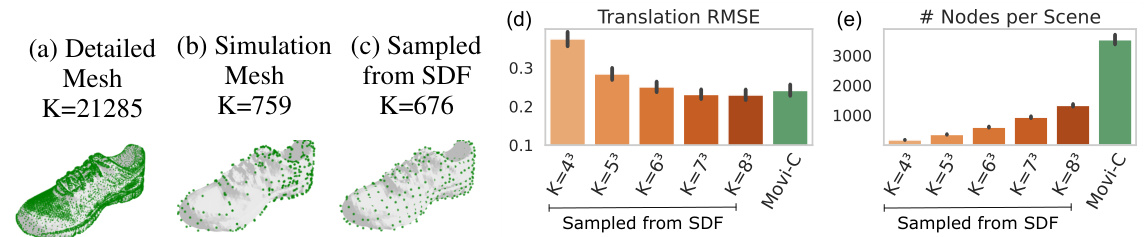

This figure shows a comparison of different node sampling strategies for representing a shoe object from the Movi-C dataset in the SDF-Sim model. It compares using the original high-resolution mesh, a simplified collision mesh used for simulation, and a new method of sampling nodes directly from the learned SDF. The results demonstrate that sampling from the learned SDF offers a favorable trade-off between accuracy (translation RMSE) and the number of nodes required, leading to potentially significant computational savings. The original mesh is shown for context, illustrating its high complexity compared to the alternative approaches.

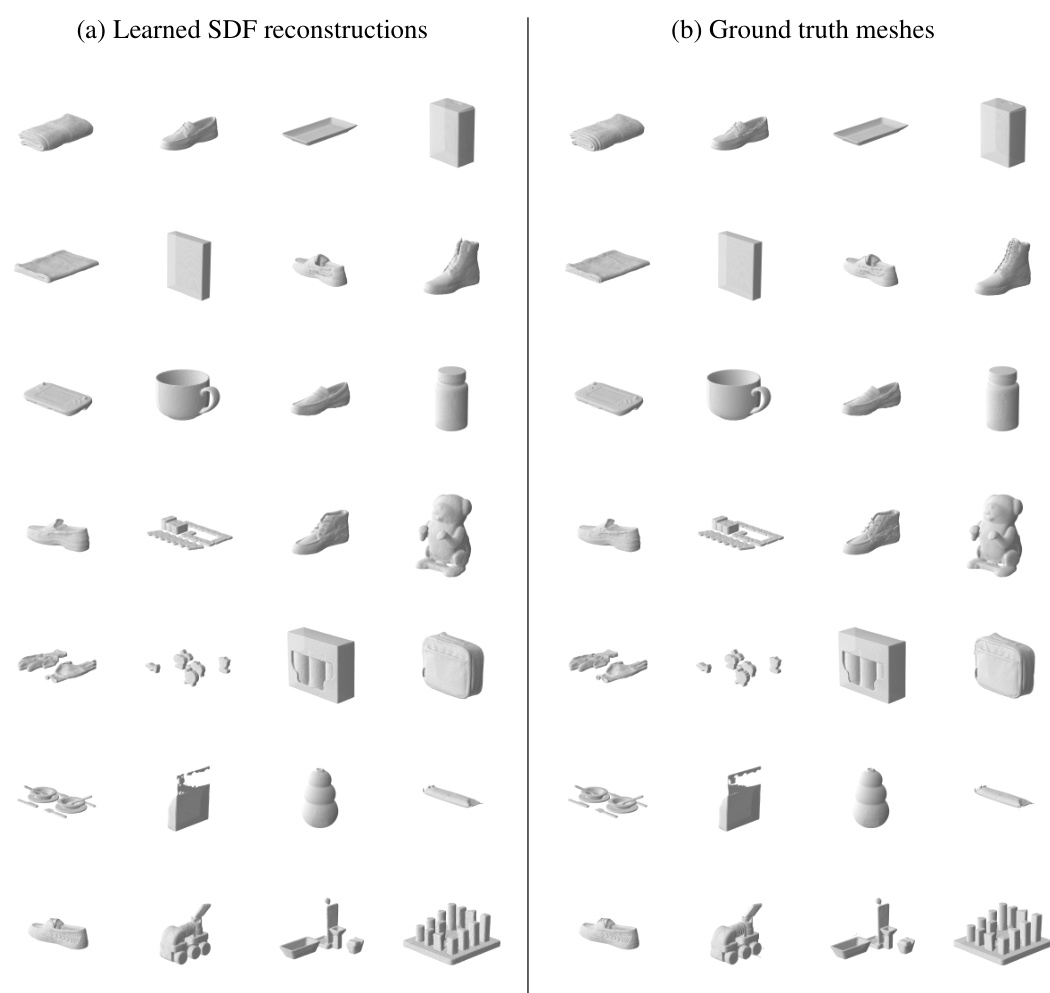

This figure shows a comparison between learned SDF reconstructions and ground truth meshes for a selection of objects from the Movi-C dataset. The left column (a) displays 3D models generated from learned Signed Distance Functions (SDFs). The right column (b) shows the original, ground truth meshes used to train the SDFs. The visual similarity highlights the effectiveness of the learned SDFs in representing object shapes.

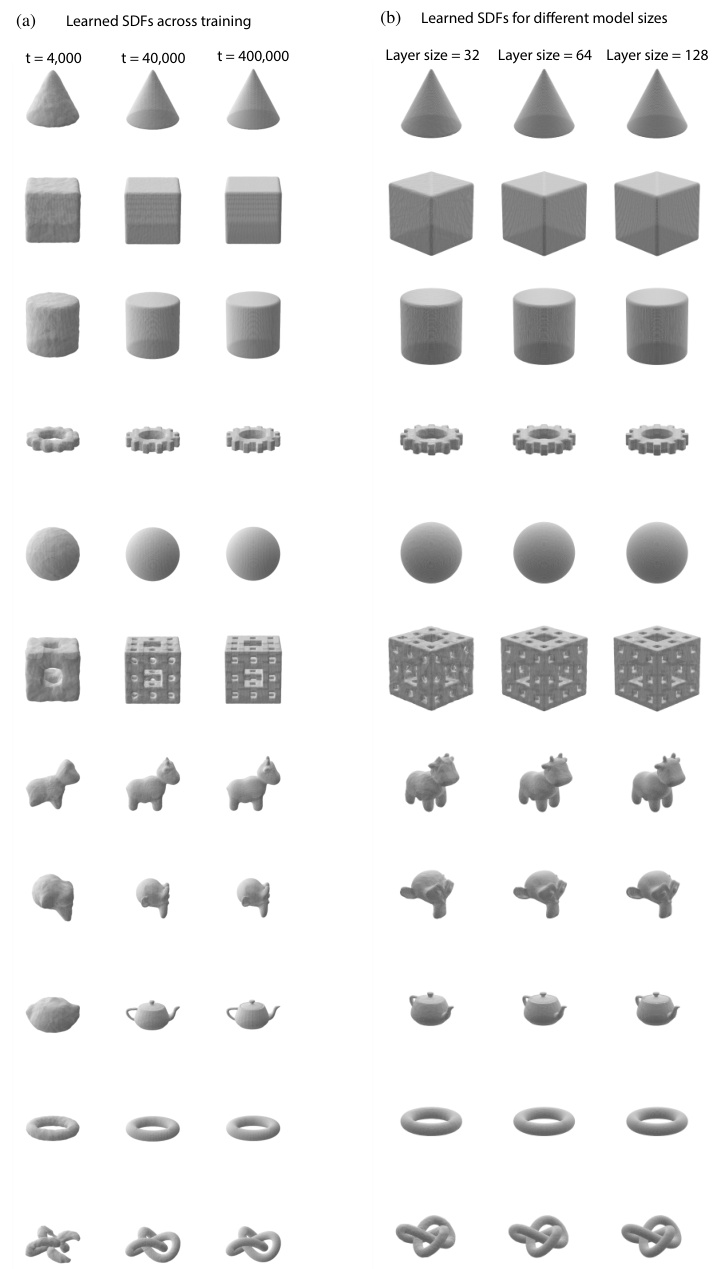

This figure shows the learned signed distance functions (SDFs) for different training iterations and model sizes. The left side (a) demonstrates how the learned SDFs improve in accuracy with more training steps (4000, 40000, and 400000 iterations). The right side (b) displays the impact of model size (MLP layers with 32, 64, or 128 units) on the final SDF representation. Each row represents a different object, illustrating the effect of training duration and model complexity on the resulting 3D shape representation. The visualization uses Marching Cubes to convert the implicit SDF representation into a mesh for better understanding.

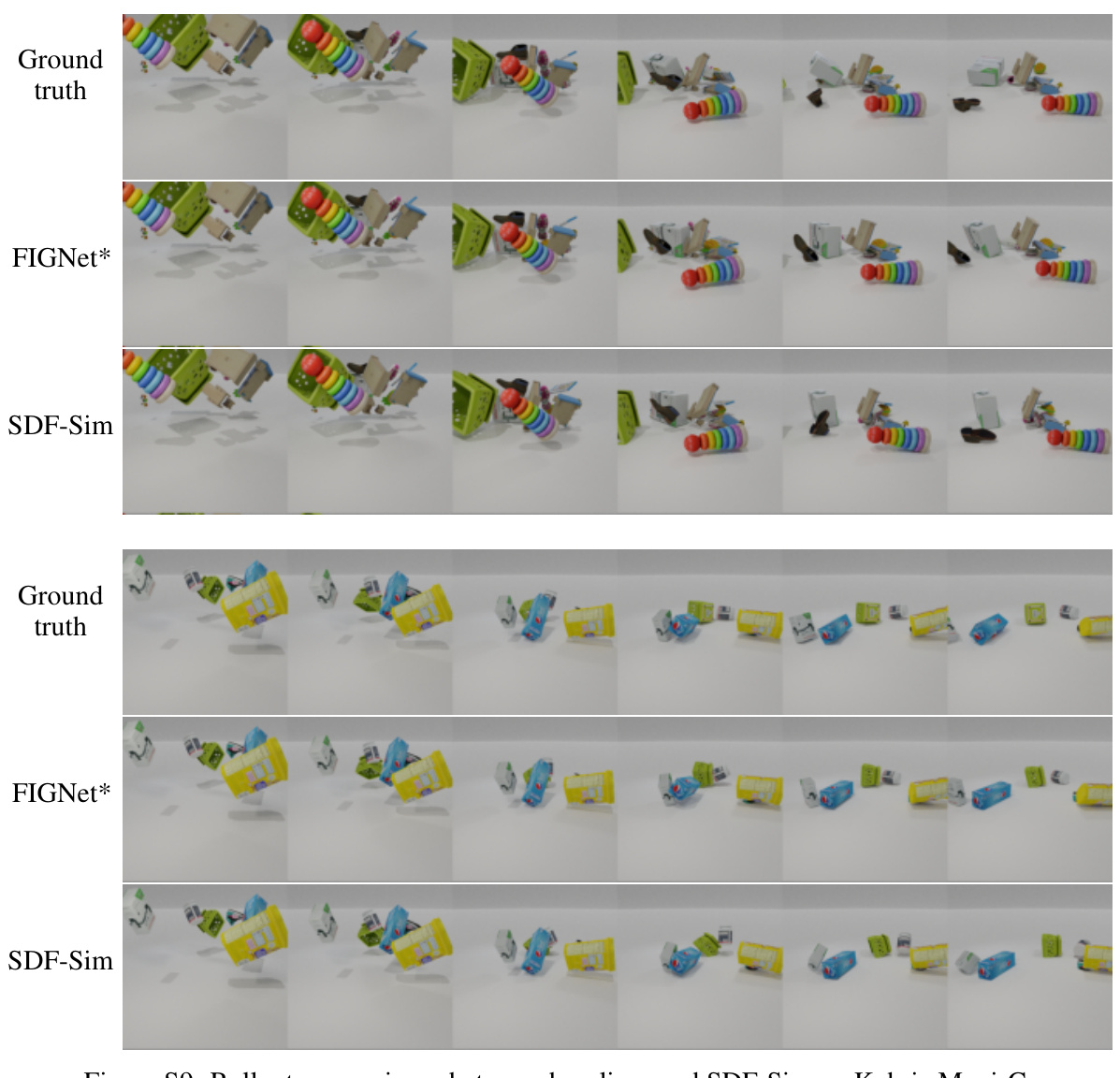

This figure shows a comparison of simulation rollouts between the baselines (FIGNet*) and SDF-Sim on the Kubric Movi-C dataset. It visually demonstrates the differences in the predicted object trajectories and how they compare to the ground truth. Each row represents a different method (ground truth, FIGNet*, SDF-Sim), with multiple columns showing the simulation progression over time for several different scenes within the dataset.

This figure compares the simulation results of three different methods: Ground truth, FIGNet*, and SDF-Sim, on the Kubric Movi-C dataset. Each row represents a different method, and each column shows the simulation at different timesteps. This allows for a visual comparison of the accuracy of each method in predicting the motion of objects in a complex scene.

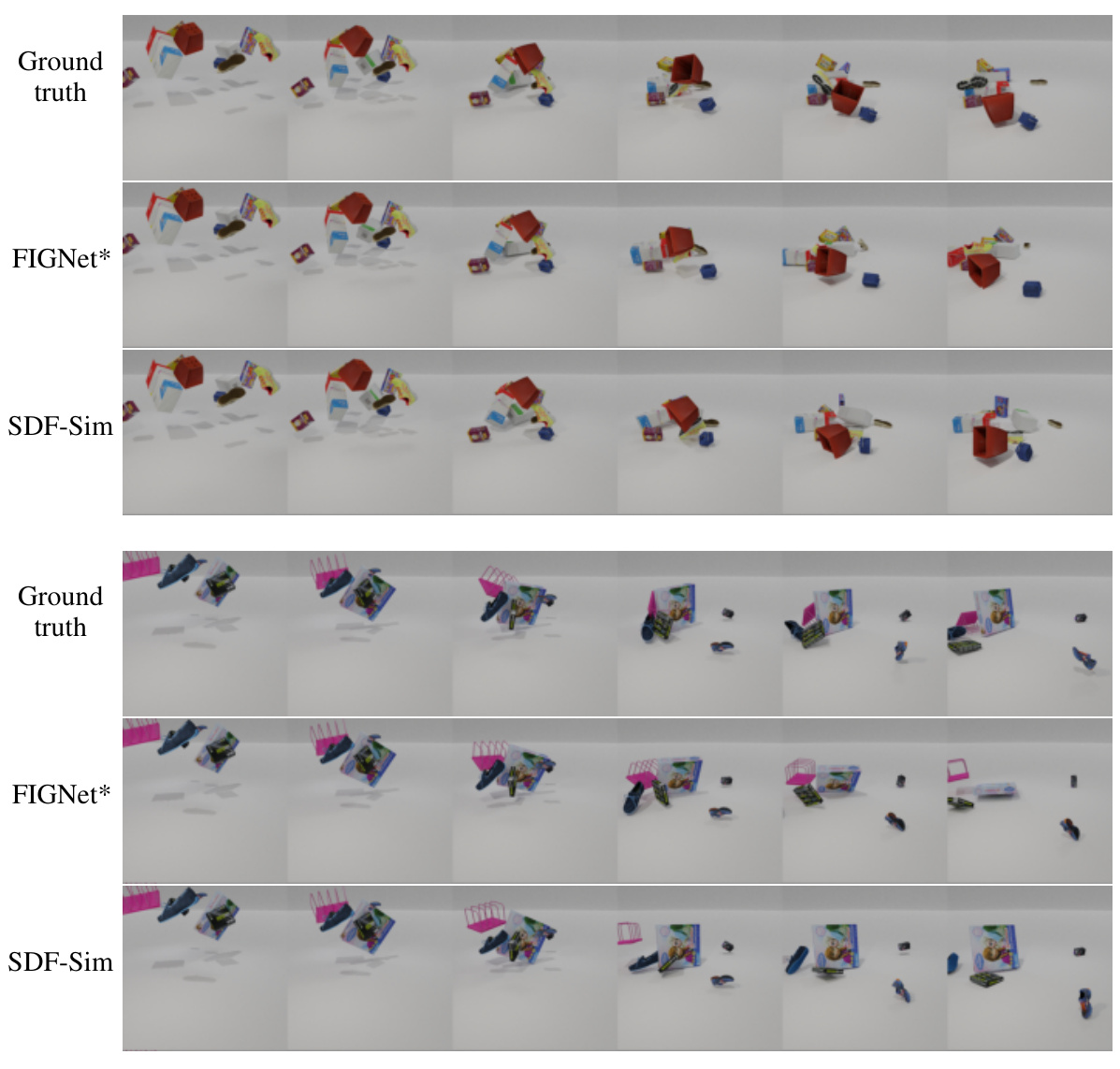

This figure shows a comparison of the simulation results between SDF-Sim and the baseline methods (FIGNet and FIGNet*) on the Kubric Movi-C dataset. The figure displays several rollouts showing the movement of multiple objects over time. It visually compares the accuracy of the different methods in predicting the motion of the objects.

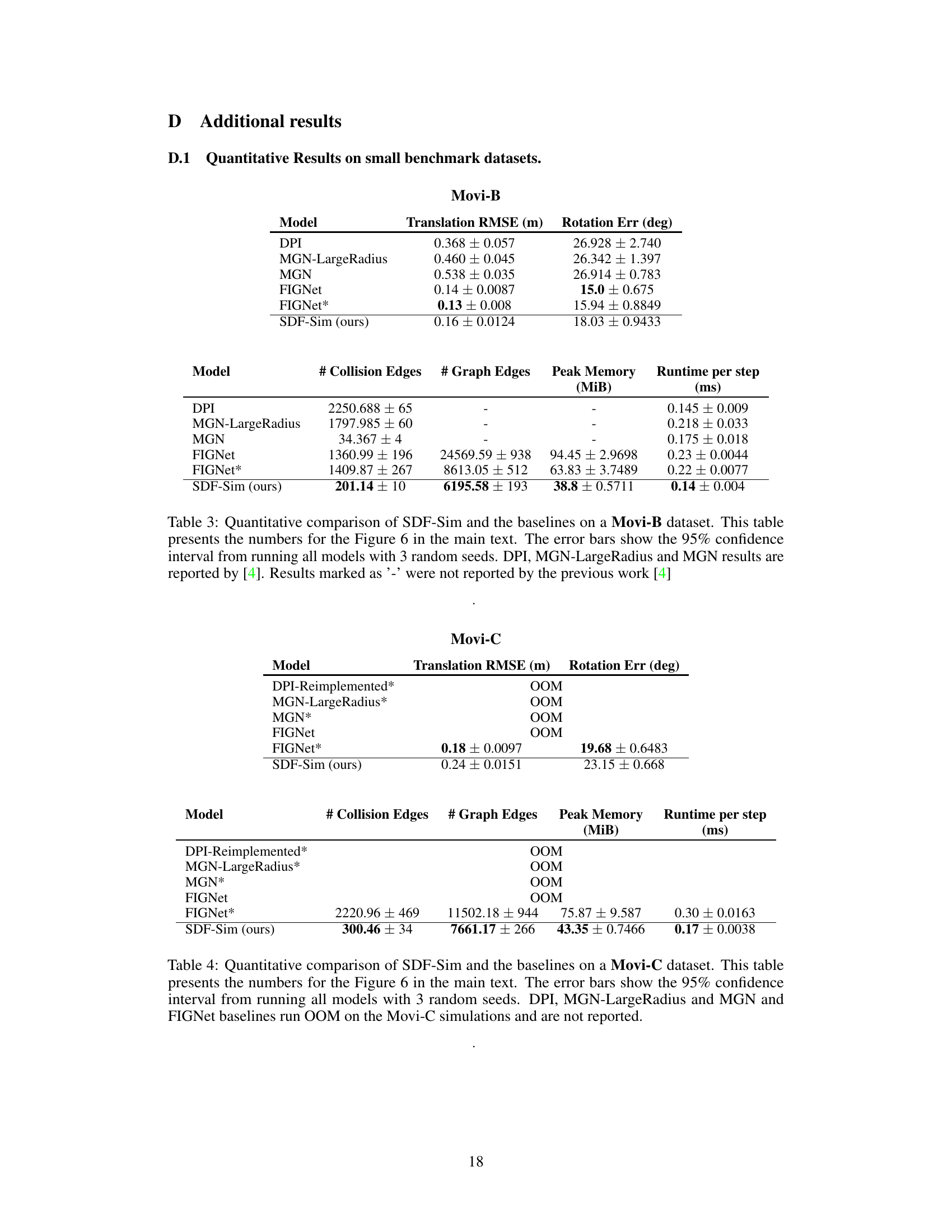

More on tables

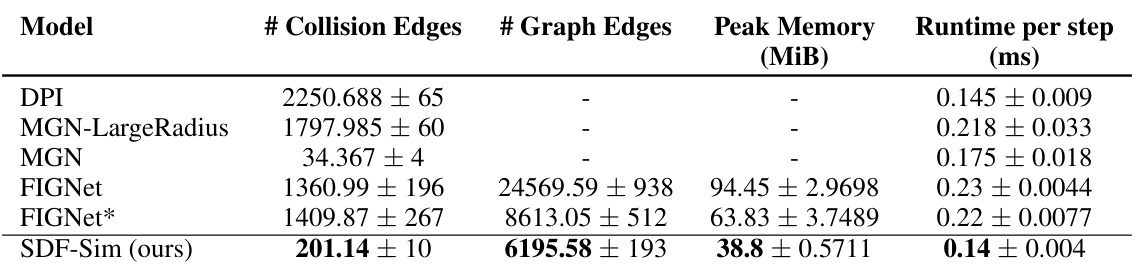

This table compares the performance of several rigid body simulation models on the Movi-B benchmark dataset. It shows the translation and rotation errors, number of collision and graph edges, peak memory usage, and runtime per step for each model. The results highlight SDF-Sim’s efficiency in terms of memory and runtime compared to other approaches. Note that some baselines were not able to complete the evaluation due to memory limitations.

This table compares the performance of SDF-Sim against several baseline models (DPI, MGN-LargeRadius, MGN, FIGNet, FIGNet*) on the Movi-B dataset from the Kubric benchmark. Metrics include the number of collision and graph edges, peak memory usage, and runtime per simulation step. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals from three independent runs. Note that some baseline results are from a previous study and some metrics are not reported for all baselines.

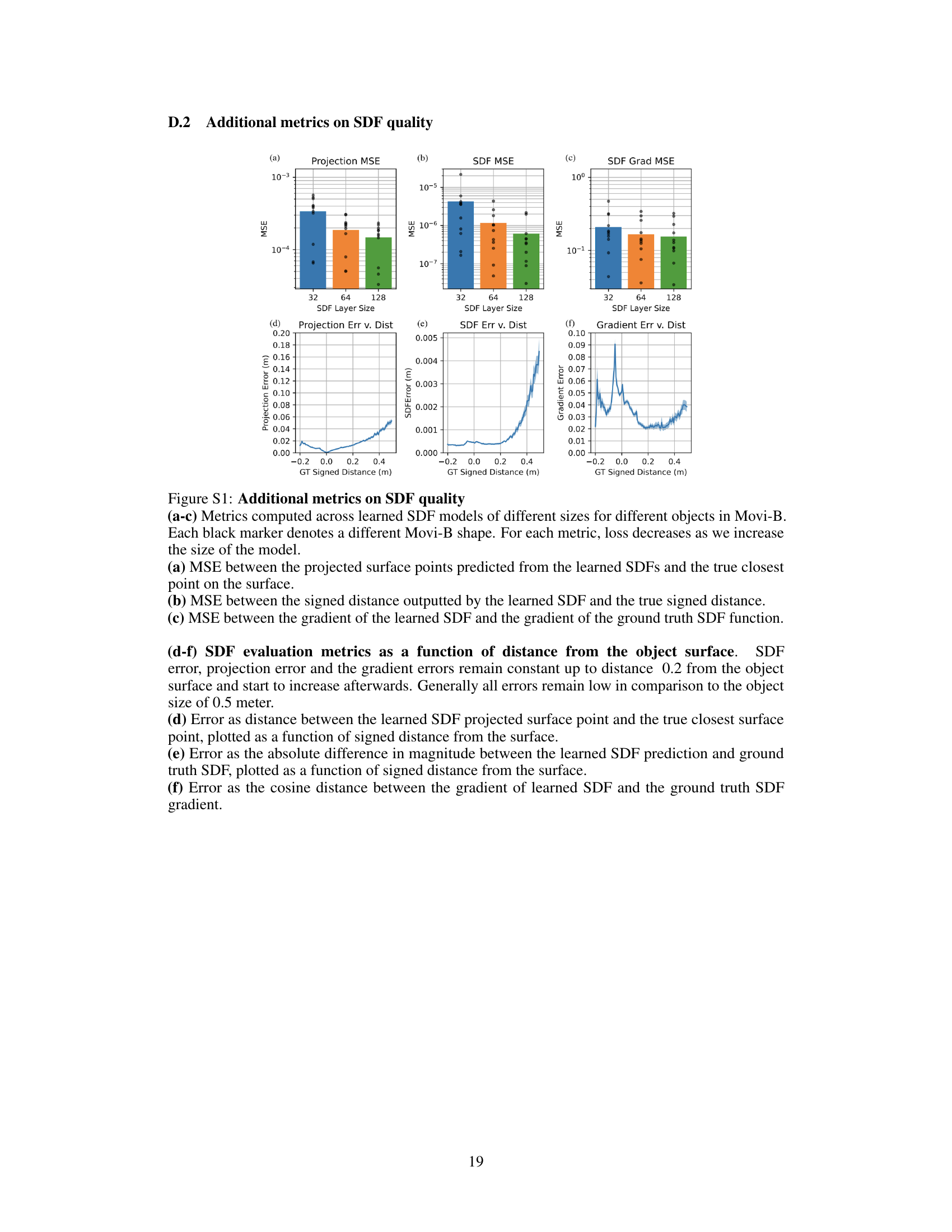

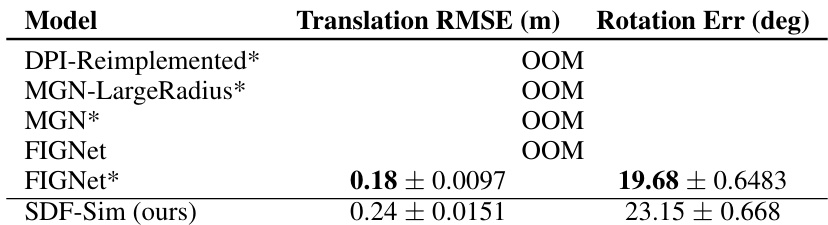

This table shows a quantitative comparison of SDF-Sim against other state-of-the-art learned simulators for rigid body dynamics on the Movi-C dataset from the Kubric benchmark. It reports the translation and rotation errors, along with the number of collision edges and graph edges in the simulation graphs. The results show that SDF-Sim achieves lower translation and rotation errors than FIGNet*, while also having significantly fewer graph edges, indicating a more efficient approach.

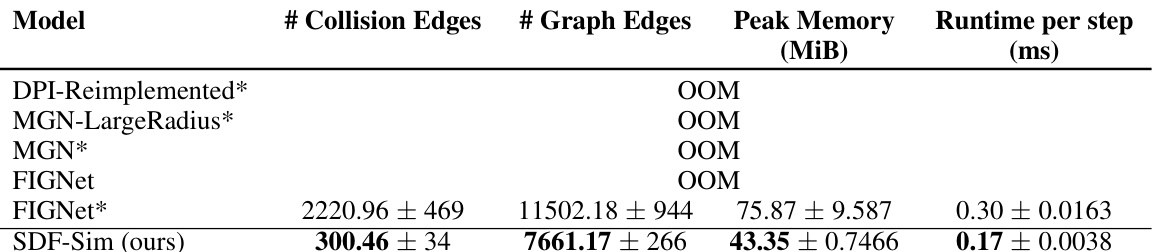

This table compares the performance of SDF-Sim with several baseline models on the Movi-C dataset. It shows the number of collision and graph edges, peak memory usage, and runtime per simulation step for each model. Note that several baseline models ran out of memory (OOM) on this dataset, highlighting the scalability advantage of SDF-Sim.

Full paper#