↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many high-stakes decisions rely on AI predictions, but these algorithms often fail to consider contextual information accessible to human experts. This difference in information availability can limit the accuracy of AI predictions, especially when dealing with complex or ambiguous situations. While algorithms may generally outperform humans on average, incorporating human insight can significantly enhance the prediction quality.

This research introduces a novel framework to improve AI predictions by selectively incorporating human expertise. It uses ‘algorithmic indistinguishability’ to identify inputs that appear similar to the algorithm but are significantly different in a human expert’s view. By focusing human effort on these specific instances, the approach provably improves any feasible algorithm. Experiments on chest X-rays reveal this method can boost accuracy by identifying nearly 30% of cases where human expertise offers valuable additions to algorithmic predictions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it offers a novel framework for combining human expertise and AI in prediction tasks. It provides a principled method for improving predictions by leveraging human judgment in situations where algorithms struggle, opening avenues for more effective human-AI collaboration across various high-stakes fields. The findings are especially relevant given the increasing reliance on AI in decision-making, addressing the limitations of algorithmic predictors and highlighting the continued importance of human judgment.

Visual Insights#

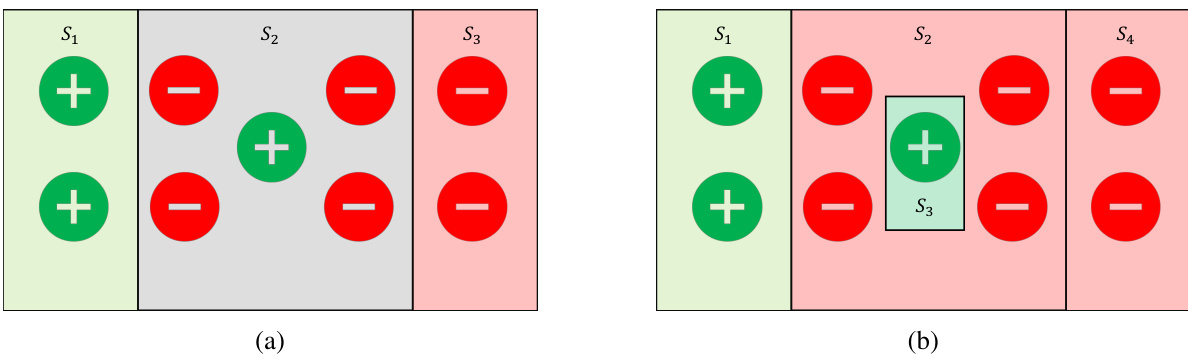

This figure illustrates the concept of approximately multicalibrated partitions using a simple example with hyperplane classifiers. Panel (a) shows a partition of data points into three subsets (S1, S2, S3) where a hyperplane classifier cannot effectively separate positive and negative examples within each subset. Panel (b) presents another example with a different partition, highlighting that there are multiple ways to create such partitions. The key takeaway is that within each subset, there’s not enough signal for a hyperplane classifier to distinguish between the positive and negative outcomes, which is the defining characteristic of an approximately multicalibrated partition.

In-depth insights#

Human-AI Synergy#

Human-AI synergy explores the potential for humans and artificial intelligence to collaborate effectively, exceeding the capabilities of either alone. A key aspect is identifying where human judgment adds value, particularly in situations where algorithms struggle. This may involve areas with nuanced contextual understanding, interpretation of ambiguous data, or tasks requiring creative problem-solving. Effective synergy necessitates understanding algorithmic limitations, recognizing which predictions are trustworthy and where human expertise is crucial for improved accuracy. Successful collaboration also requires effective communication and data integration between human and AI systems. This might involve using intuitive interfaces that facilitate human input and feedback mechanisms that enable AI to learn from human corrections. Building trust and transparency is essential as AI systems become more integral to decision-making processes; humans need to understand how the AI arrives at its conclusions and feel confident in its capabilities. Ultimately, human-AI synergy aims to create robust and reliable systems, capitalizing on the unique strengths of both while minimizing their individual weaknesses.

Algorithmic Limits#

The heading ‘Algorithmic Limits’ prompts a rich discussion on the inherent boundaries of AI prediction. It suggests exploring where algorithms fall short, focusing on the types of information they fail to capture, such as nuanced contextual details, subtle visual cues, and human intuition. This leads to a consideration of the limitations of training data, how biases within datasets might limit predictive capabilities, and how these limitations affect the reliability of algorithmic predictions in high-stakes situations. A key consideration is the complementarity between human and algorithmic predictions. While algorithms excel at tasks with well-defined patterns, humans often prove invaluable in tasks requiring judgment, common sense, or contextual understanding that algorithms lack. Finally, discussing ‘Algorithmic Limits’ also necessitates examining the ethical implications of deploying AI systems with limited prediction capabilities, especially in domains where decisions have far-reaching consequences. Exploring these boundaries and acknowledging the limits of algorithms is crucial for developing ethical and effective human-AI collaborations.

X-Ray Experiments#

In hypothetical X-ray experiments, the core aim would be to assess the efficacy of incorporating human expertise into algorithmic predictions for medical image analysis. The study would likely involve comparing the performance of algorithms alone versus a human-in-the-loop approach. A key aspect would be defining what constitutes ‘algorithmic indistinguishability’, meaning instances where algorithms struggle to differentiate. Human experts, potentially radiologists, could be tasked with classifying these challenging cases. The research would then quantify the improvement (or lack thereof) achieved by incorporating human judgment. Crucially, it would analyze whether humans consistently outperform algorithms or only improve on a specific subset of difficult cases, identifying patterns to enable more effective human-AI collaboration. Ultimately, the goal is to explore the complementary strengths of humans and algorithms, aiming to refine AI performance while understanding the specific conditions under which human input is most valuable.

Multicalibration Use#

Multicalibration, in the context of this research paper, is presented as a powerful technique to identify subsets of data points that are indistinguishable to a given class of prediction models. This indistinguishability is not about identical data, but rather about instances where even the best models within that class cannot reliably differentiate outcomes. The utility of this concept lies in its ability to isolate areas where human expertise might offer unique insights that algorithms miss. By carefully incorporating human judgments on these subsets, the researchers show a provable improvement in prediction accuracy over solely algorithmic approaches. This framework is particularly valuable for applications where, despite algorithmic superiority on average, human input can significantly enhance model performance on specific, identifiable cases. The approach offers a principled method for human-AI collaboration, moving beyond simple heuristics towards a theoretically grounded integration of human and machine intelligence.

Noncompliance Robustness#

The concept of ‘Noncompliance Robustness’ in prediction systems tackles the challenge of user autonomy and varied adoption of algorithmic recommendations. It acknowledges that users, such as physicians using a diagnostic risk score, may choose to ignore or override the algorithm’s suggestions based on their own judgment or external factors. This section highlights the crucial problem that a single, universally optimal predictive model might not exist when user compliance is heterogeneous. Instead of designing individualized models for each user, the focus shifts to creating a single robust model that performs well despite varied compliance behaviors. This requires sophisticated modeling of user compliance patterns and careful design to achieve near-optimal performance across diverse user decision-making strategies. The key challenge lies in understanding and quantifying the impact of noncompliance on algorithmic effectiveness and developing prediction techniques that minimize losses under various user response scenarios. The discussion suggests that this might be possible by using multicalibrated partitions to ensure that the prediction algorithm doesn’t make similar mistakes on subsets of instances, enhancing the robustness to non-uniform compliance. This approach necessitates a move beyond minimizing average errors across all users to handling the heterogeneity of compliance patterns while still ensuring optimal predictions, thus providing more meaningful and reliable outputs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

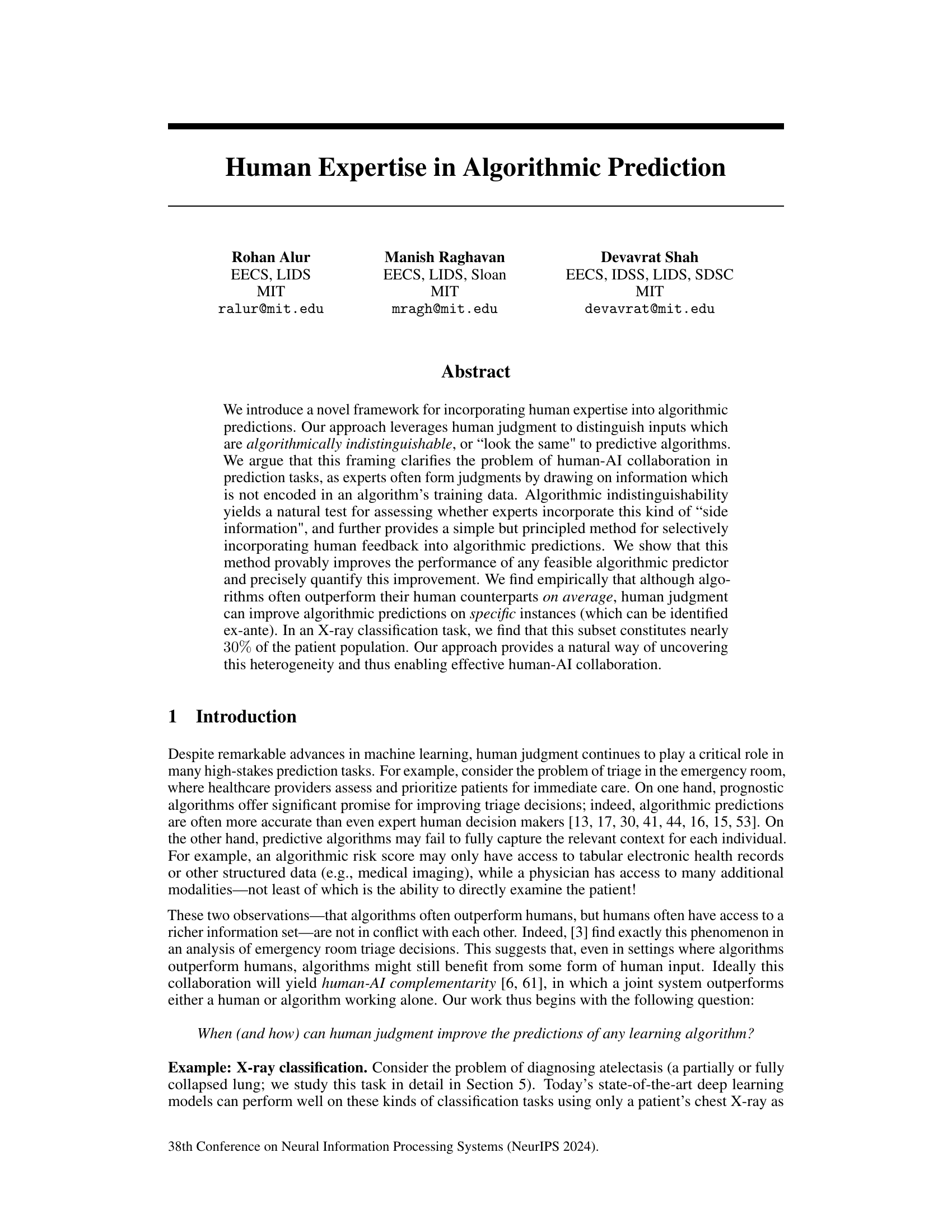

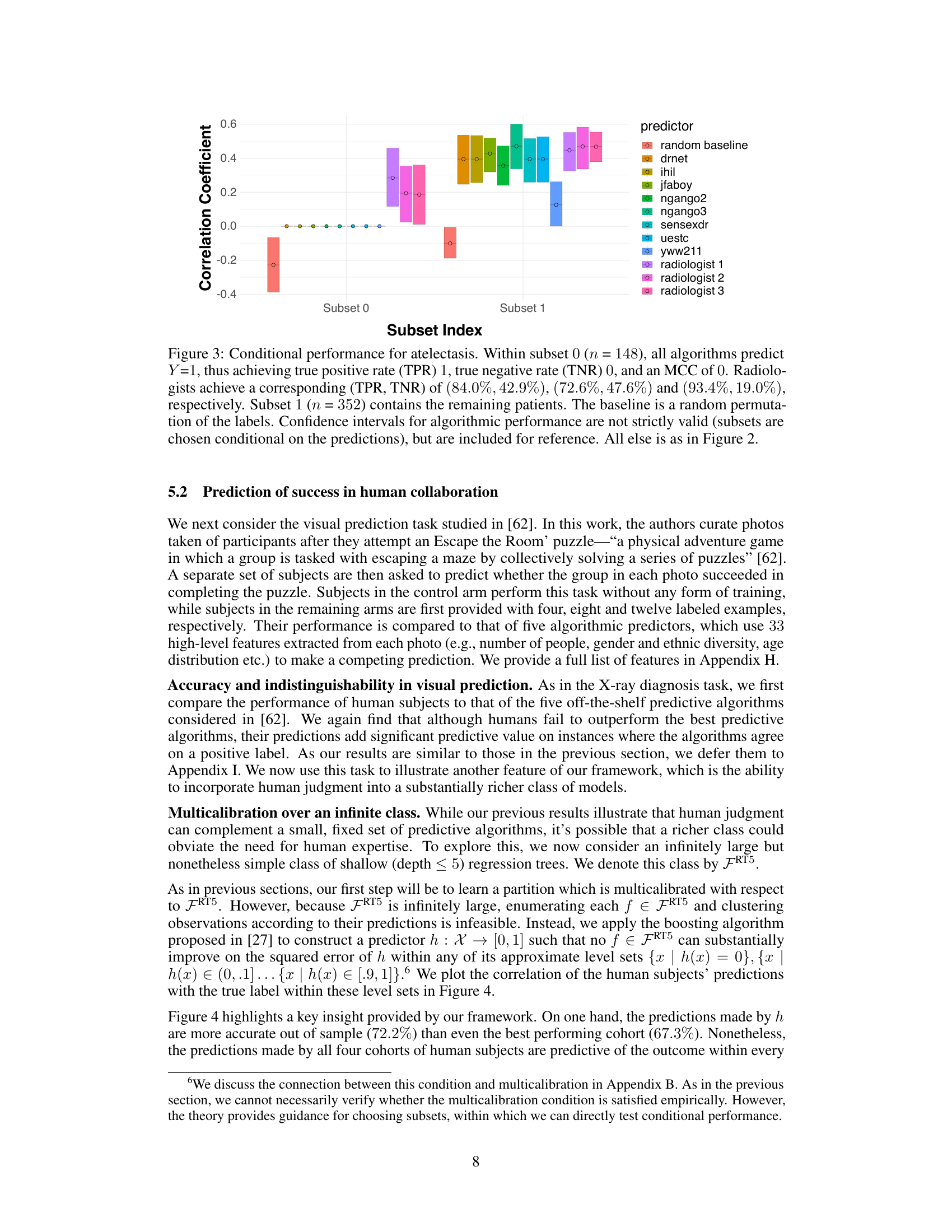

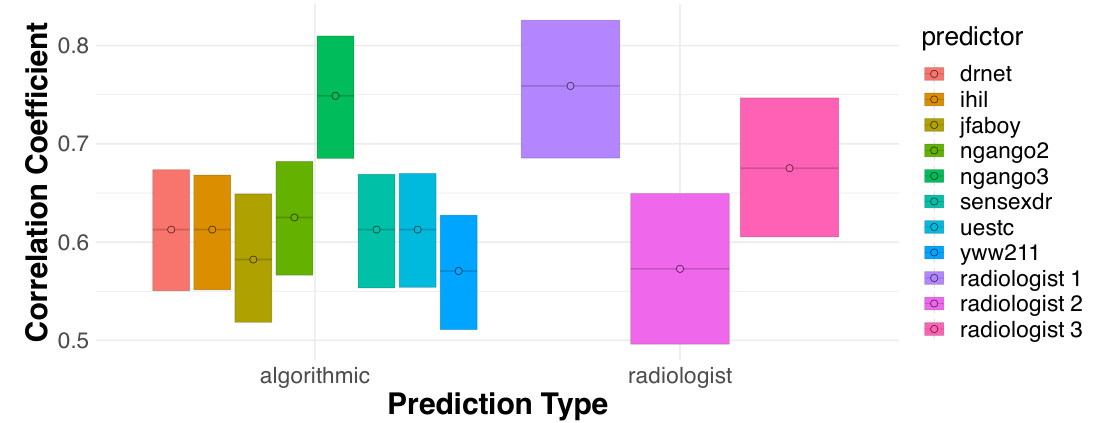

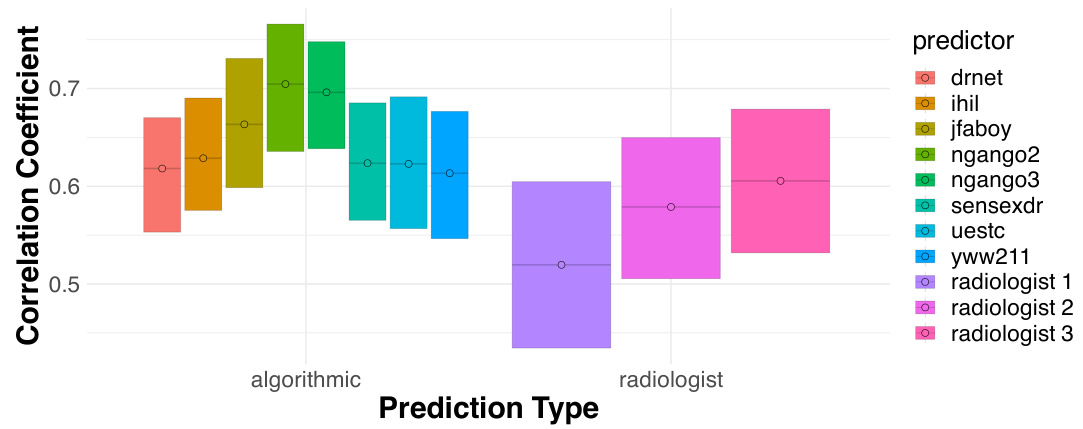

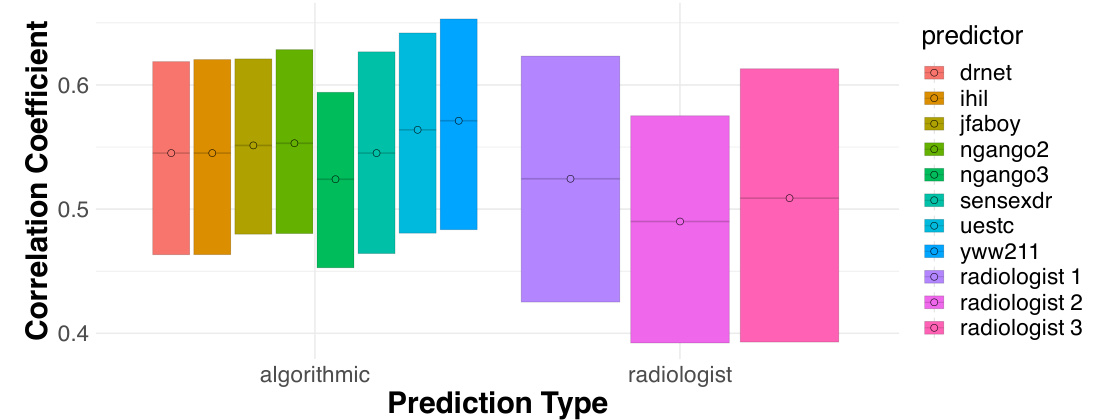

This figure compares the performance of three radiologists against eight algorithmic prediction models on a chest X-ray classification task for detecting atelectasis. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is used as the performance metric. Error bars represent 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, showing the statistical significance of the results. The results indicate that there is no statistically significant difference in the overall performance between radiologists and the algorithms.

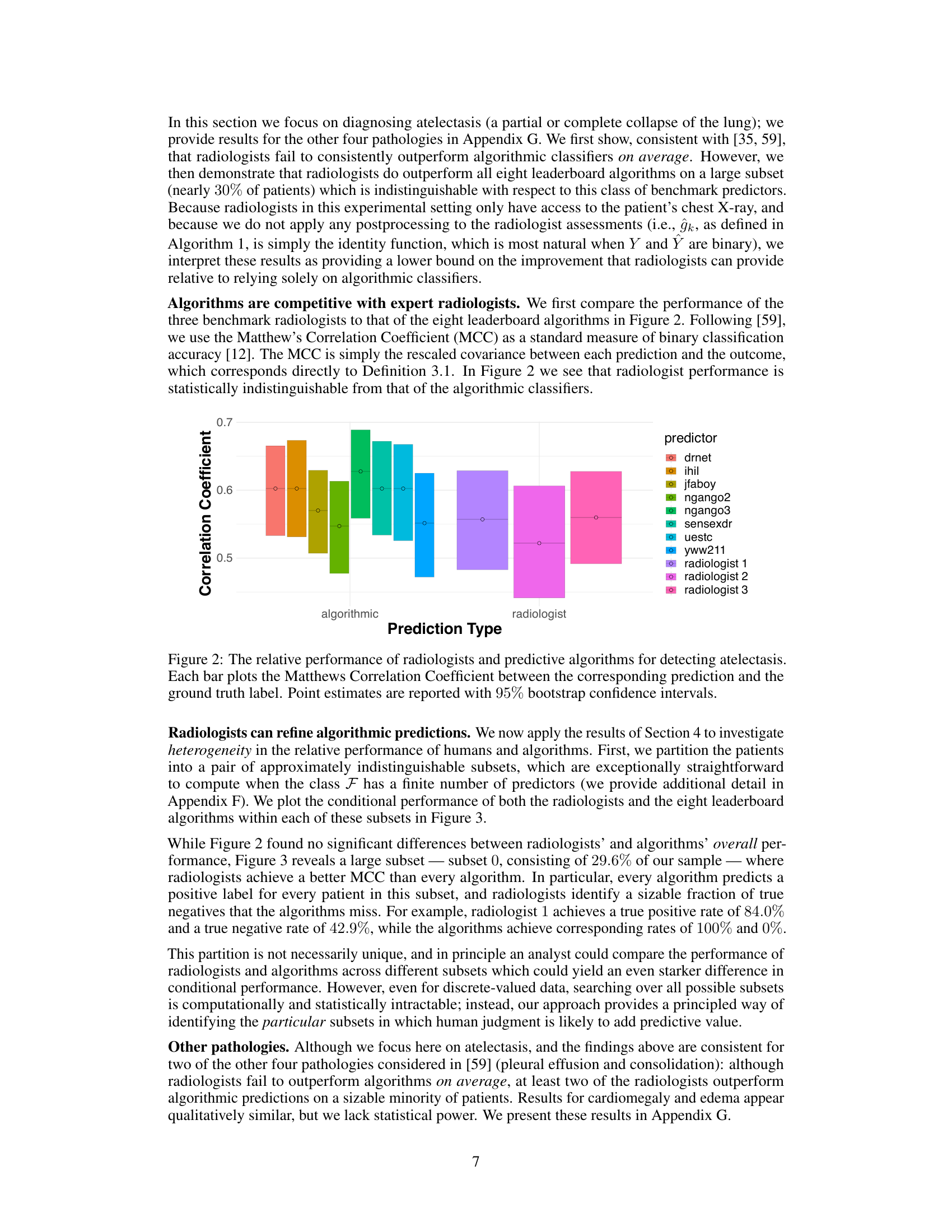

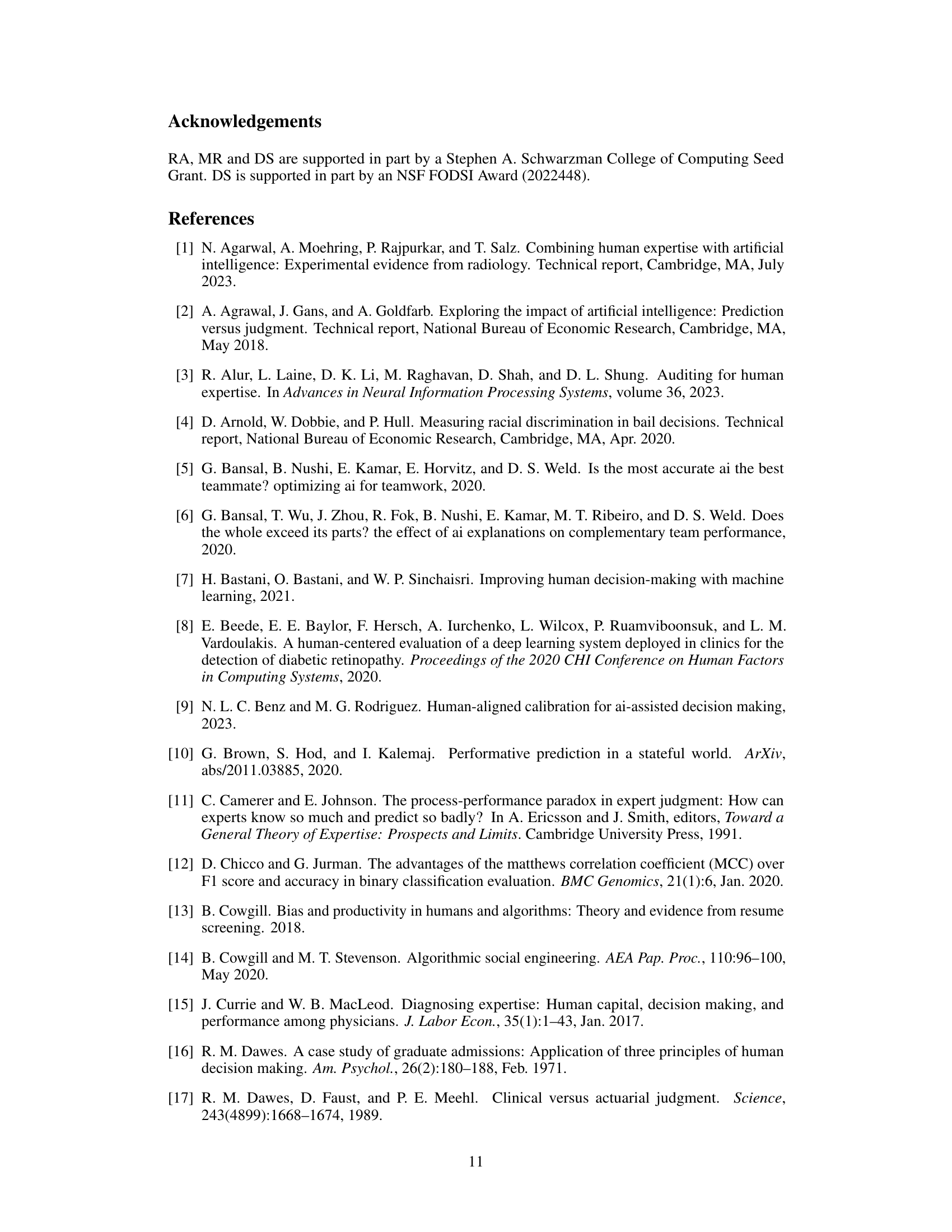

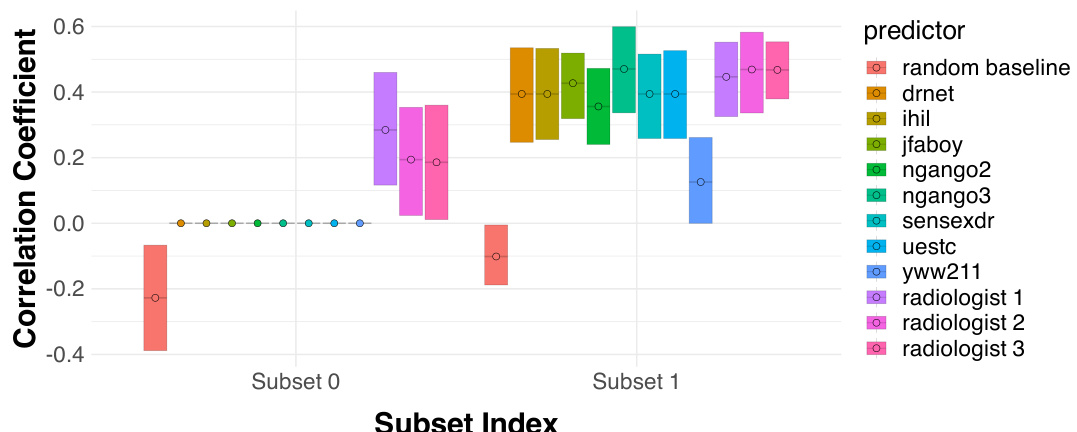

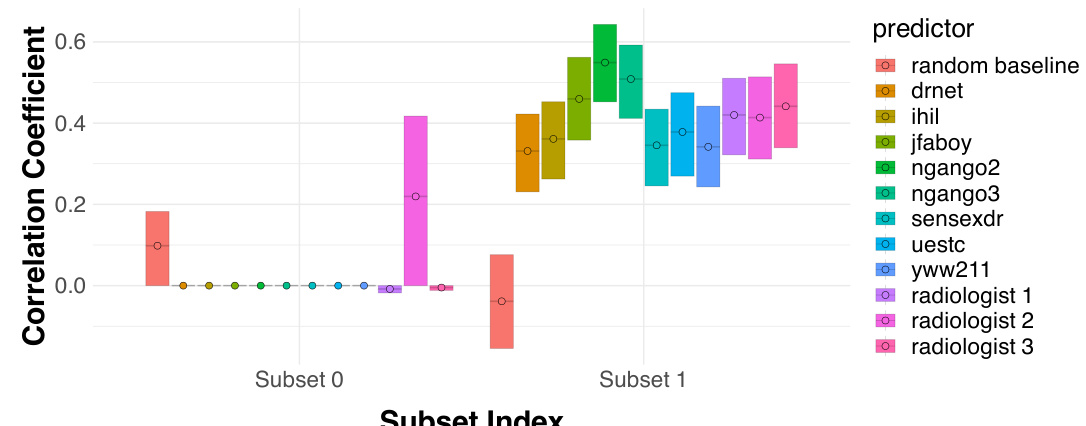

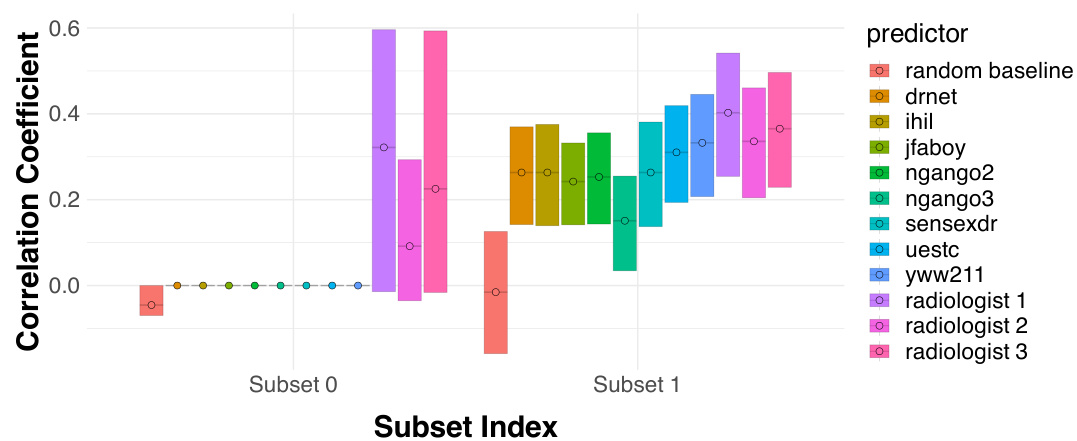

This figure shows the conditional performance of radiologists and eight different algorithms in two subsets of patients with atelectasis. Subset 0, comprising nearly 30% of the patients, shows radiologists outperforming all algorithms because the algorithms incorrectly predict a positive label for all patients in this subset while radiologists correctly identify some true negatives. Subset 1 includes the remaining patients, where the performances of radiologists and algorithms are comparable. This illustrates how human expertise can improve predictions in specific instances, even when algorithms are superior overall.

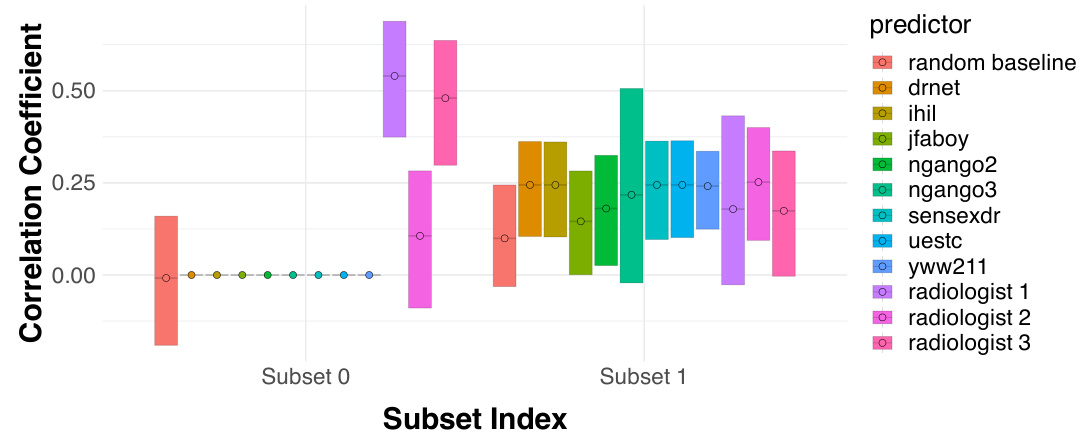

This figure shows the correlation between human predictions and the true outcome within different level sets of a multicalibrated predictor. The predictor, h, was trained using a boosting algorithm to make predictions indistinguishable to a large class of regression tree models. The results show that, even though the multicalibrated predictor outperforms humans overall, the human predictions still provide additional predictive signal within each level set.

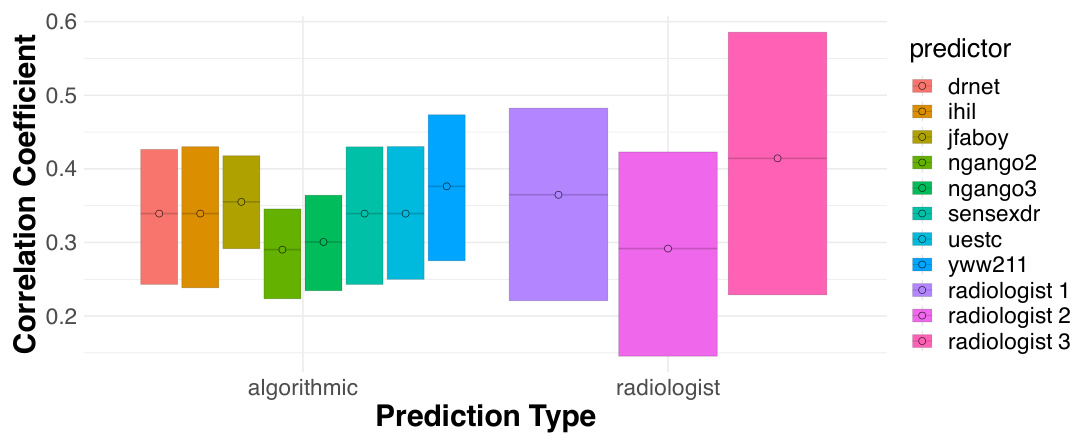

This figure compares the performance of three radiologists against eight algorithmic models in detecting atelectasis using chest X-rays. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), a measure of binary classification accuracy, is used to assess the performance of each predictor. Error bars represent 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, indicating the uncertainty in the estimates.

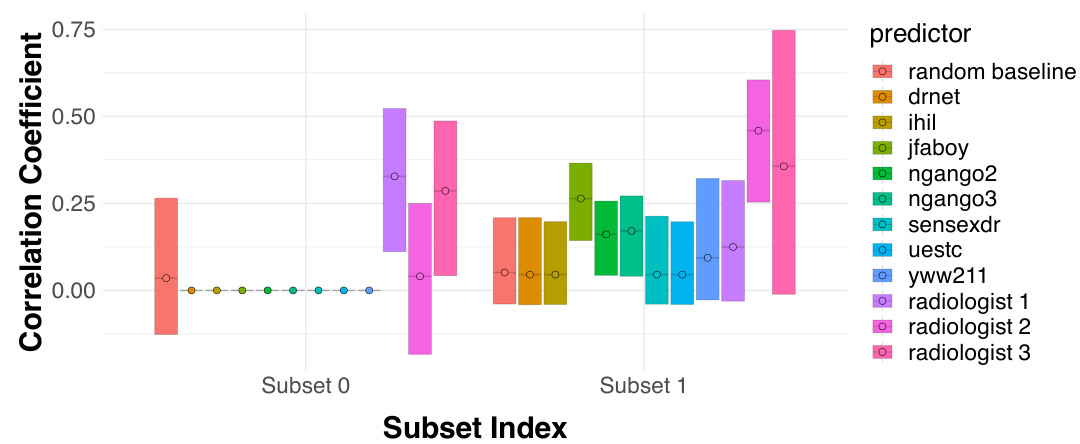

This figure shows the performance of radiologists and algorithms on two subsets of patients for the atelectasis diagnosis task. Subset 0 shows a case where all algorithms always predict a positive outcome, thus resulting in a perfect TPR but 0 TNR. Radiologists show substantially better performance in this subset. Subset 1 is the rest of the patients and shows comparable performance between radiologists and algorithms.

This figure compares the performance of three radiologists and eight algorithmic models in detecting atelectasis using chest X-ray images. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), a measure of binary classification accuracy, is calculated for each predictor, comparing their predictions to ground truth labels. Error bars represent 95% bootstrap confidence intervals, showing the variability of each predictor’s performance.

This figure shows the conditional performance of radiologists and algorithms for detecting atelectasis in two subsets of patients. Subset 0 contains instances where all algorithms predict a positive label and radiologists outperform the algorithms by correctly identifying true negatives. Subset 1 contains the remaining patients, showing no significant performance difference between radiologists and algorithms.

This figure compares the performance of three radiologists against eight different algorithmic models in detecting atelectasis (a partially or fully collapsed lung) using chest X-ray images. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), a measure of the correlation between the prediction and the actual diagnosis, is used to evaluate performance. The figure shows that the performance of radiologists is statistically indistinguishable from that of the best-performing algorithms. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval, indicating the uncertainty of the estimate. This indicates that while algorithms are highly competitive with human radiologists in this task, it does not rule out potential for human contribution to improve prediction accuracy.

This figure shows the conditional performance of radiologists and algorithms in two subsets of patients, which were previously identified as indistinguishable by the eight algorithms. Subset 0 contains patients that were all predicted as positive by the algorithms, while subset 1 contains the rest. This figure demonstrates that, while the algorithm’s overall performance was better than human performance, humans achieve better performance than algorithms on instances where algorithms are not able to distinguish.

This figure compares the performance of three radiologists against eight algorithmic models in predicting atelectasis (a lung collapse). The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), a measure of binary classification accuracy, is used. The bars represent the MCC for each radiologist and algorithm, with error bars showing 95% confidence intervals. The result shows that radiologists and algorithms perform similarly overall.

This figure compares the performance of radiologists and eight different algorithms in classifying atelectasis (a lung condition). Two subsets of patients are compared: Subset 0, where all algorithms predict the same outcome; and Subset 1, which includes the remaining patients. The results reveal that radiologists significantly outperform algorithms in Subset 0, suggesting that human judgment can add value in instances where algorithmic predictions are homogenous.

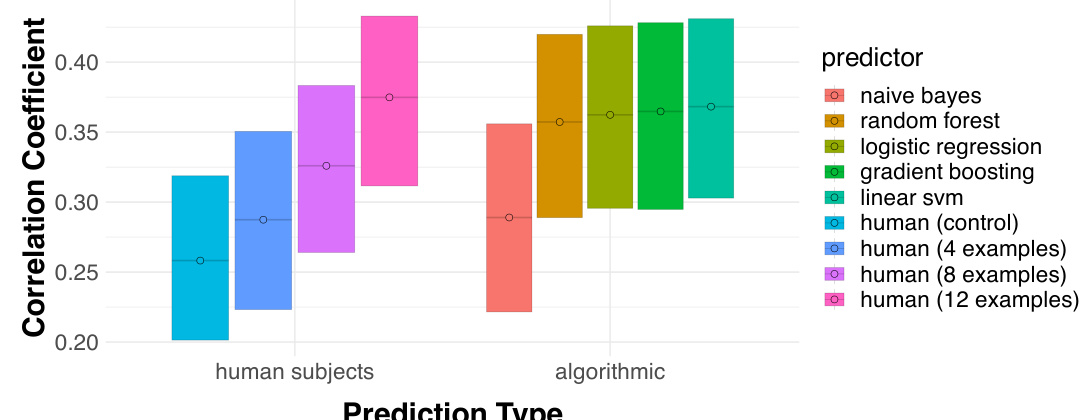

This figure compares the performance of human subjects and five different machine learning algorithms on a visual prediction task. Humans were tested in four different conditions: a control group with no prior training and three groups who were trained with 4, 8, and 12 examples respectively. The figure shows the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) for each group and algorithm, demonstrating that while machine learning algorithms generally perform better than humans, human performance improves as the amount of training increases.

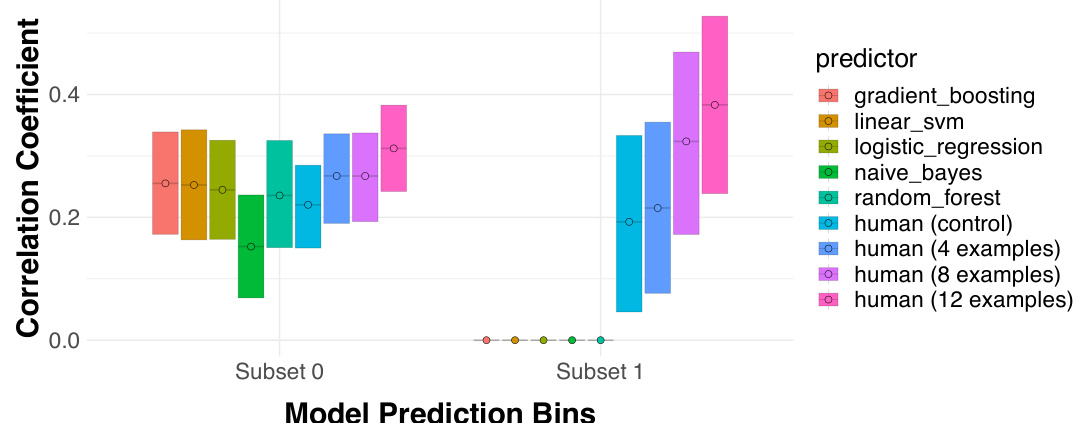

This figure shows the performance comparison of human and algorithmic predictions within two subsets of data points which are algorithmically indistinguishable. Subset 1 contains instances where all five algorithms agree on a positive prediction, and Subset 0 contains the remaining data. The plot displays the correlation coefficient between each prediction type (five algorithms and four human groups with varying levels of training) and the true outcome. It is used to demonstrate the added value of human judgment on the subset where the algorithms are all in agreement, showing that even when algorithms outperform humans overall, human input can refine predictions on specific instances.

Full paper#