↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many natural processes and generative models rely on diffusion processes, typically characterized by drift, interaction, and stochastic components. Learning these components from observational data is challenging, with existing methods often employing complex bilevel optimization and focusing solely on drift estimation. This leads to limitations in representational power, scalability, and accuracy.

This research introduces JKOnet*, a novel approach leveraging first-order optimality conditions of the Jordan-Kinderlehrer-Otto (JKO) scheme. JKOnet* directly minimizes a quadratic loss, enabling efficient and accurate recovery of all three components (potential, interaction, and internal energy). Its closed-form solution for linearly parametrized functionals and superior performance in real-world cellular process predictions showcase its enhanced efficiency and versatility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is vital for researchers in diffusion processes and generative models due to its significant speed improvements and enhanced representational capabilities. It offers a novel, computationally efficient method for learning diffusion processes from observational data, opening new avenues for research in biological systems, and machine learning applications.

Visual Insights#

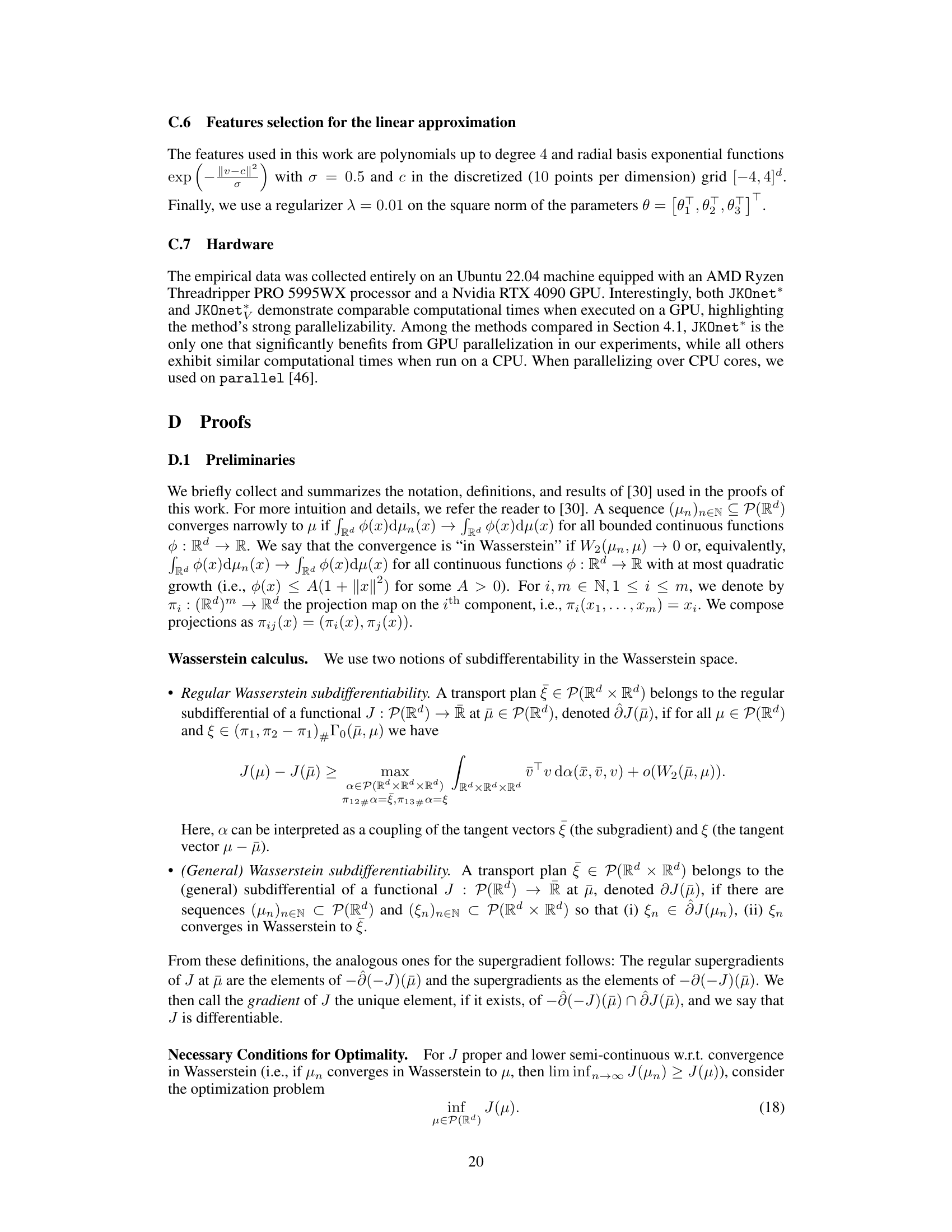

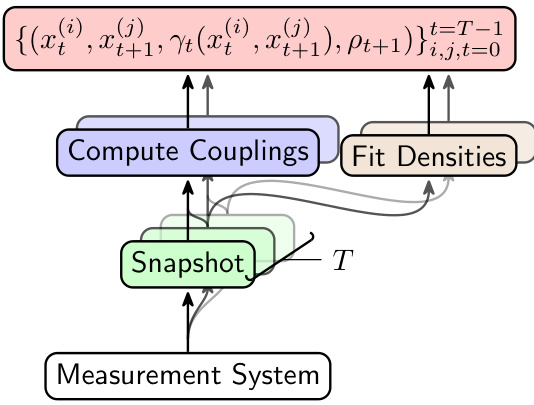

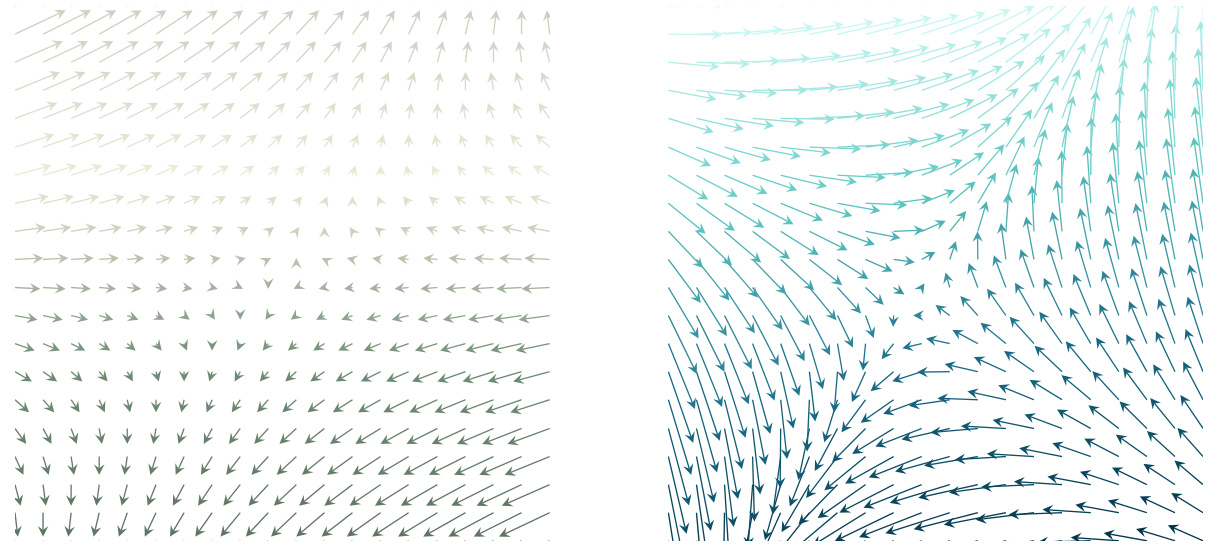

The figure illustrates the core idea of JKOnet*. Given a sequence of snapshots representing the evolution of a population of particles undergoing diffusion, the goal is to learn the parameters of an energy function that best describes this evolution. The figure shows how the model minimizes the Wasserstein distance between the observed particle trajectory and the trajectory predicted by iteratively solving the JKO (Jordan-Kinderlehrer-Otto) scheme using the learned energy function. The mismatch, visually depicted by the different arrow lengths, represents the difference between the gradients of the true and estimated energy functions. Minimizing this mismatch is the key objective of the model.

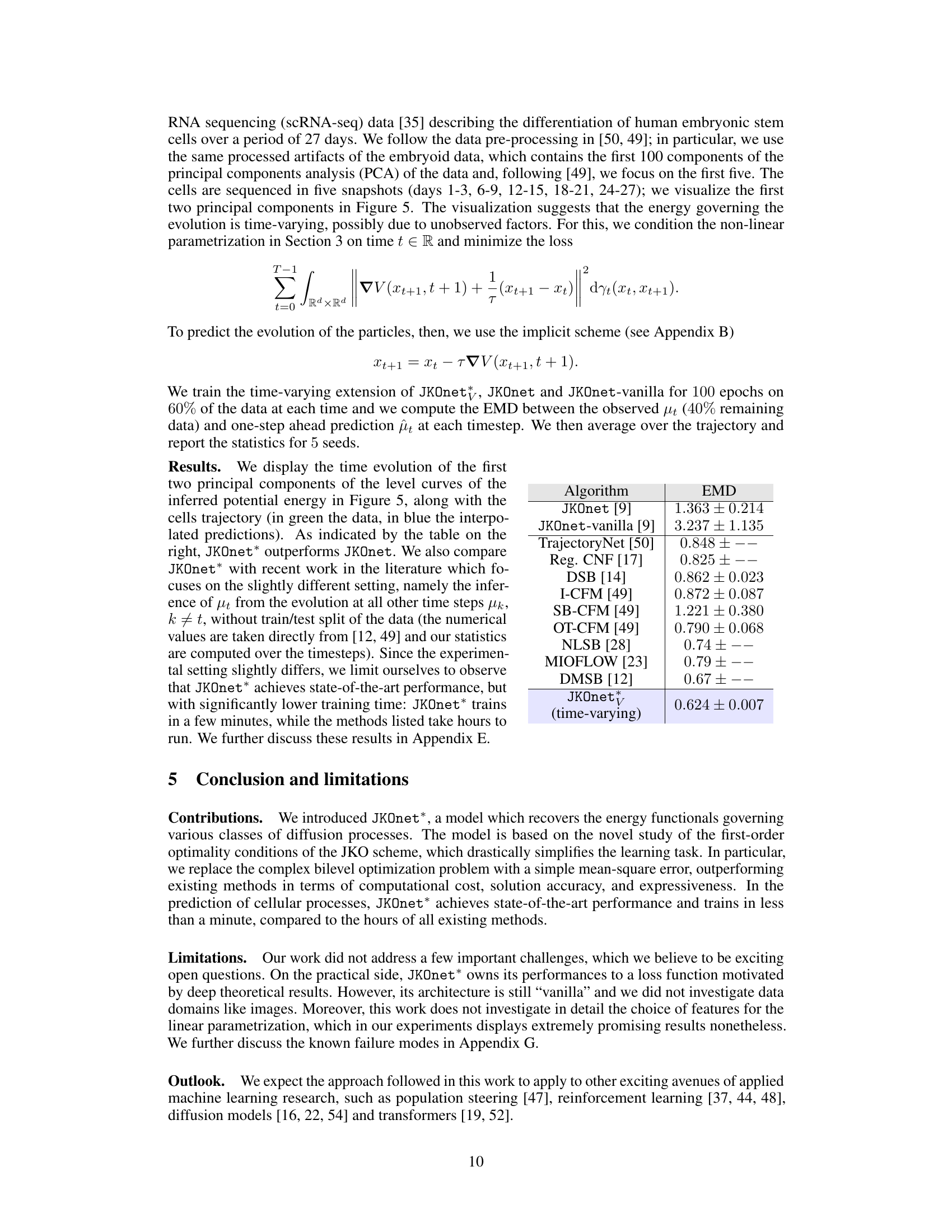

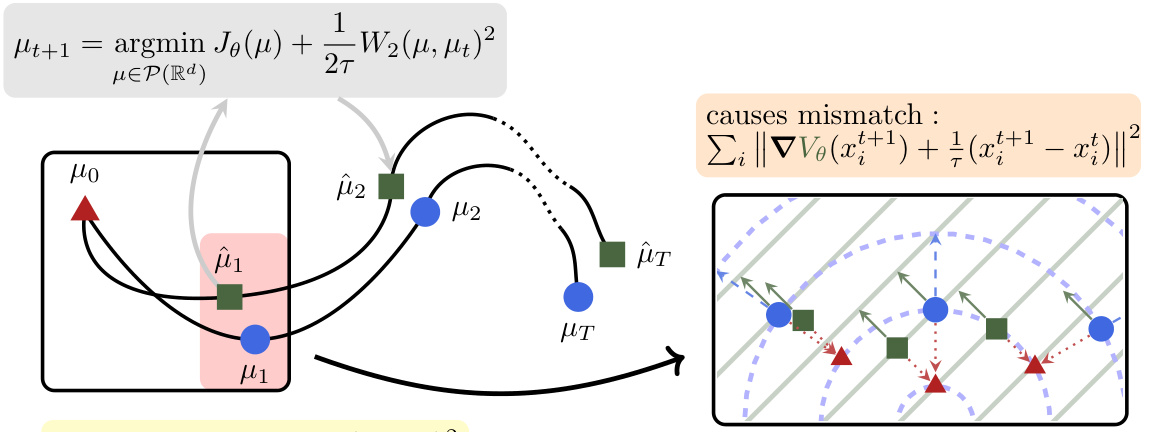

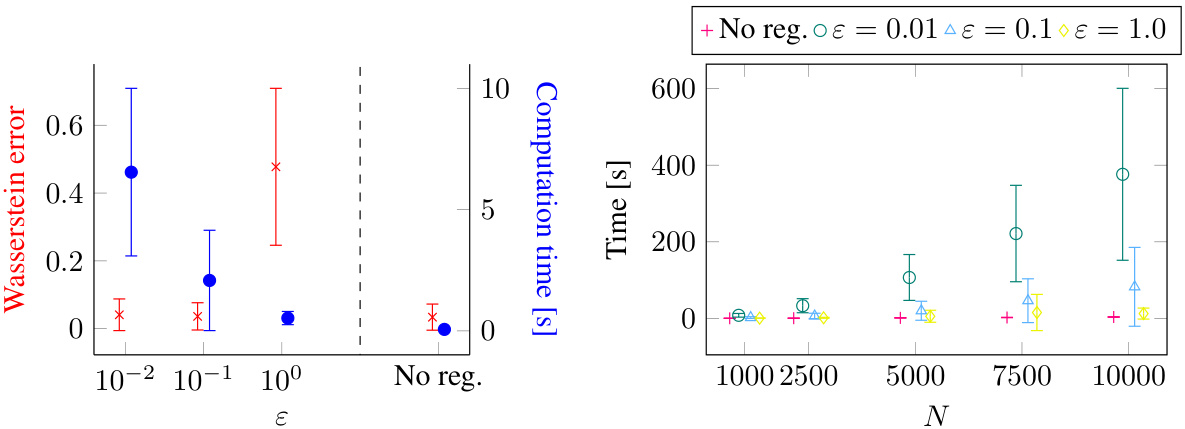

This table compares the computational complexity of different models in terms of FLOPS per epoch and sequential operations per particle. It breaks down the complexity based on different parameters such as trajectory length, number of particles, dimensionality, and number of features in the linear parametrization. It also notes the ability of each model to learn different energy components of the diffusion process (potential, interaction, and internal energy).

In-depth insights#

JKOnet* Algorithm#

The JKOnet* algorithm offers a novel approach to learning diffusion processes from population data by directly tackling the first-order optimality conditions of the JKO scheme. This method cleverly bypasses the complexities of existing bilevel optimization techniques, leading to a computationally efficient and accurate solution. JKOnet’s key innovation lies in its ability to recover not only the potential energy but also the interaction and internal energy components of the underlying diffusion process.* This enhanced representational power results in superior performance compared to existing baselines across various metrics, including sample efficiency and accuracy. Furthermore, JKOnet provides closed-form solutions for linearly parametrized functionals, simplifying implementation and enhancing scalability.* The algorithm’s theoretical grounding and empirical validation on real-world datasets, particularly in the context of cellular processes, demonstrate its effectiveness and practical utility. While it elegantly sidesteps complexities, it still relies on certain assumptions such as the differentiability of the energy functionals. The closed-form solution, however, is limited to linear cases, requiring numerical methods for non-linear functionals. Despite these limitations, JKOnet represents a significant advancement in learning diffusion processes, offering a more efficient, accurate, and interpretable framework* compared to previous methods.

Optimal Transport#

Optimal transport (OT) plays a crucial role in the research paper, providing a theoretical framework for understanding and modeling diffusion processes. The paper leverages the JKO scheme, which interprets diffusion as an energy-minimizing trajectory in the probability space, a concept fundamentally rooted in OT. This perspective enables the estimation of the underlying energy functional from population data, sidestepping the complexities of traditional approaches. The JKO scheme’s first-order optimality conditions are particularly valuable, forming the basis of a novel, efficient learning algorithm. This approach offers significant advantages over prior methods in terms of computational cost and accuracy. Notably, the paper also extends the applicability of OT to learning not just potential energies but also interaction and internal energy components, thus offering a more comprehensive and realistic model of diffusion processes. This highlights the power of OT in handling complex probability distributions and their evolution.

Diffusion Learning#

Diffusion learning is a rapidly evolving field at the intersection of machine learning and probability theory. It leverages the properties of diffusion processes, which describe the gradual spread of information or particles over time, to develop powerful generative models. A key advantage is its ability to generate high-quality samples from complex data distributions. The core idea involves learning a reversible diffusion process, transforming data into noise and then learning a reverse process to reconstruct the original data. This reverse process effectively learns the underlying data distribution and enables sample generation. Recent advancements focus on improving efficiency and scalability, addressing limitations of earlier approaches like computational complexity and sample quality. Key challenges include the design of efficient architectures and optimization strategies, as well as understanding and mitigating potential issues such as mode collapse or vanishing gradients. Future research should focus on developing more robust and versatile diffusion models, exploring novel architectures and theoretical frameworks for better understanding and control of the diffusion process. This could lead to improved performance across various machine learning tasks and broaden the applicability of diffusion learning to broader data domains and applications. Furthermore, exploring the theoretical foundations of diffusion processes is crucial, as a deeper understanding could lead to new insights and innovations.

Empirical Results#

An ‘Empirical Results’ section in a research paper would typically present the quantitative findings obtained through experiments or simulations, comparing the proposed method’s performance against established baselines. A strong section would go beyond simply stating numerical results; it would provide insightful analysis, including discussion of error metrics (e.g., precision, recall, F1-score, RMSE, etc.), statistical significance tests (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals), and visualizations such as graphs or tables illustrating key trends. A good section would also acknowledge limitations or potential biases in the experimental setup, ensuring transparency and reproducibility. Further, it should thoroughly address the research questions, emphasizing whether the method met the pre-defined goals and how it performed under different settings or conditions. Detailed descriptions of experimental parameters and hyperparameter tuning strategies would also feature prominently, enabling others to reproduce the results and verify the claims made. Finally, a robust section would integrate quantitative results with qualitative observations, potentially including failure cases or unexpected behaviors observed during experimentation. In essence, the strength of the section lies in the depth of analysis presented, not just the sheer volume of numbers reported.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section presents an opportunity for insightful expansion. Extending JKOnet’s capabilities to handle time-varying interactions and internal energies more robustly* is crucial. This involves exploring more sophisticated parametrizations and potentially incorporating more advanced optimization techniques. Investigating the model’s performance on higher-dimensional datasets and complex, real-world scenarios would strengthen its practical applicability. A key area for improvement is developing a more principled method for feature selection, especially in the context of non-linear parametrizations, to overcome the reliance on heuristic approaches. Furthermore, a deeper theoretical analysis of JKOnet’s limitations and failure modes, especially concerning non-diffusion processes and situations with non-observable energy components,* is necessary to build a more robust and reliable method. Finally, exploring connections to and integration with other machine learning frameworks, such as transformers and diffusion models, could unlock new opportunities and potentially lead to breakthroughs in areas like trajectory prediction and generative modeling.

More visual insights#

More on figures

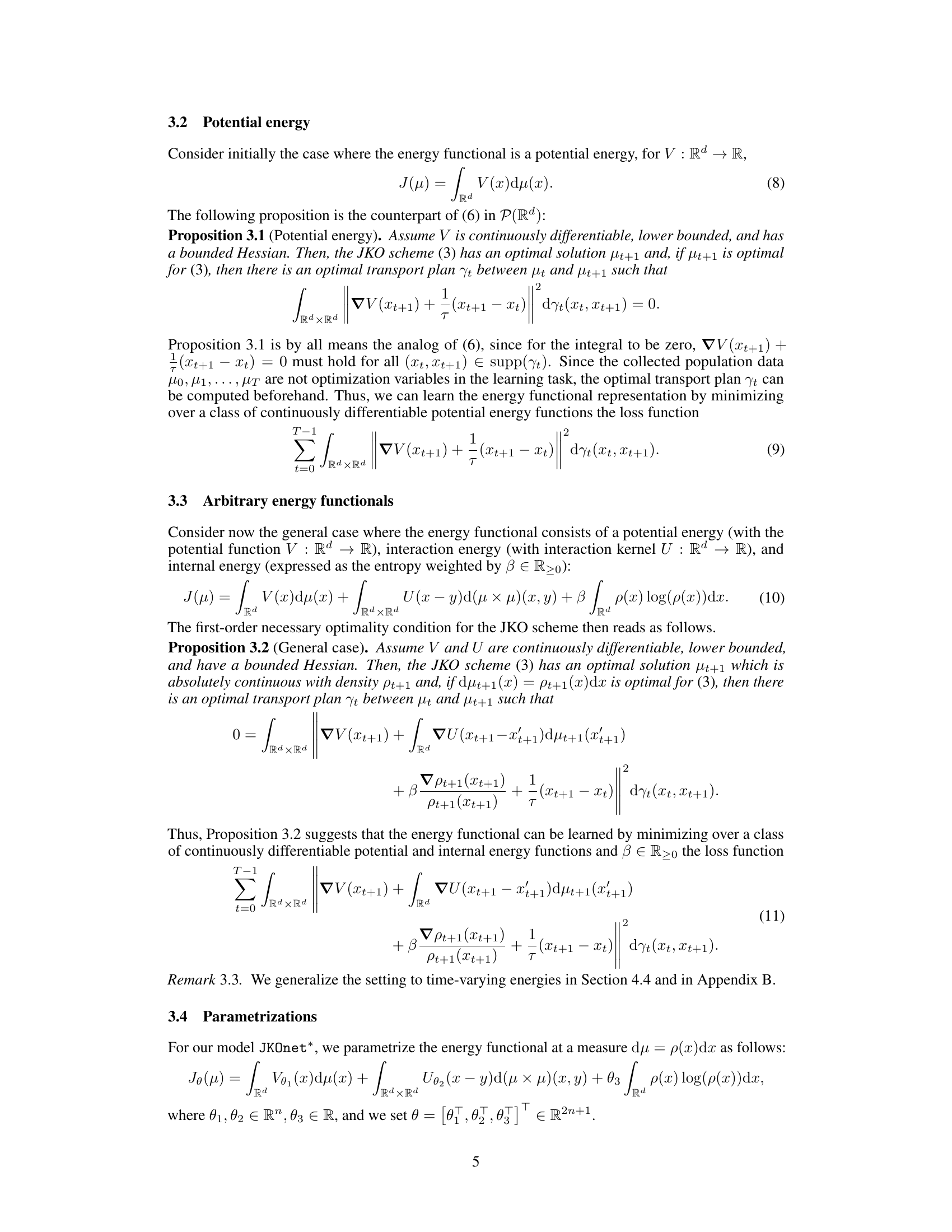

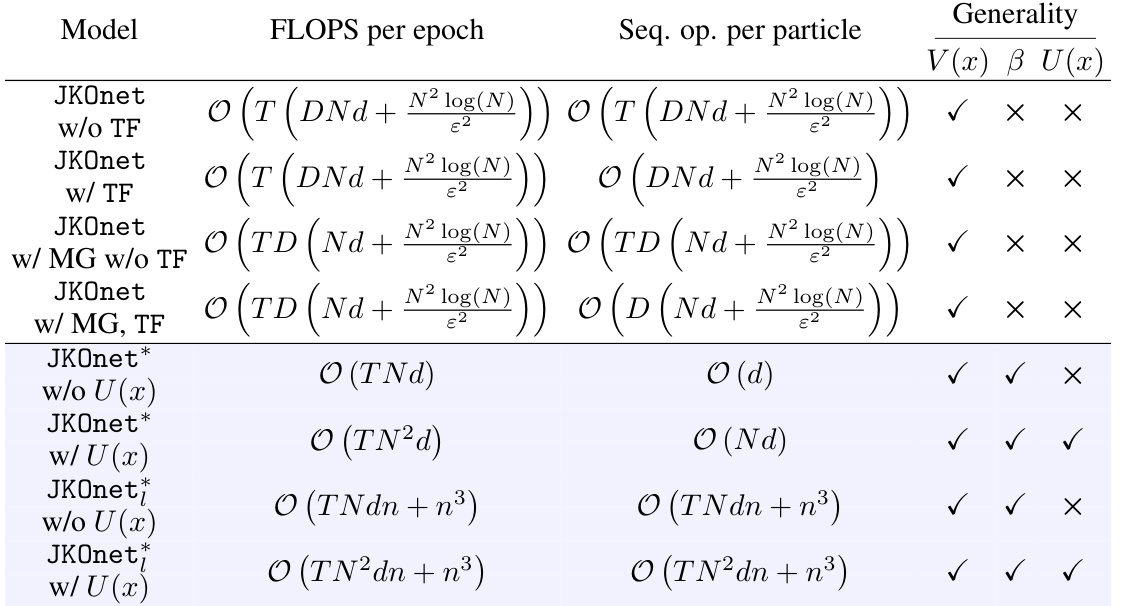

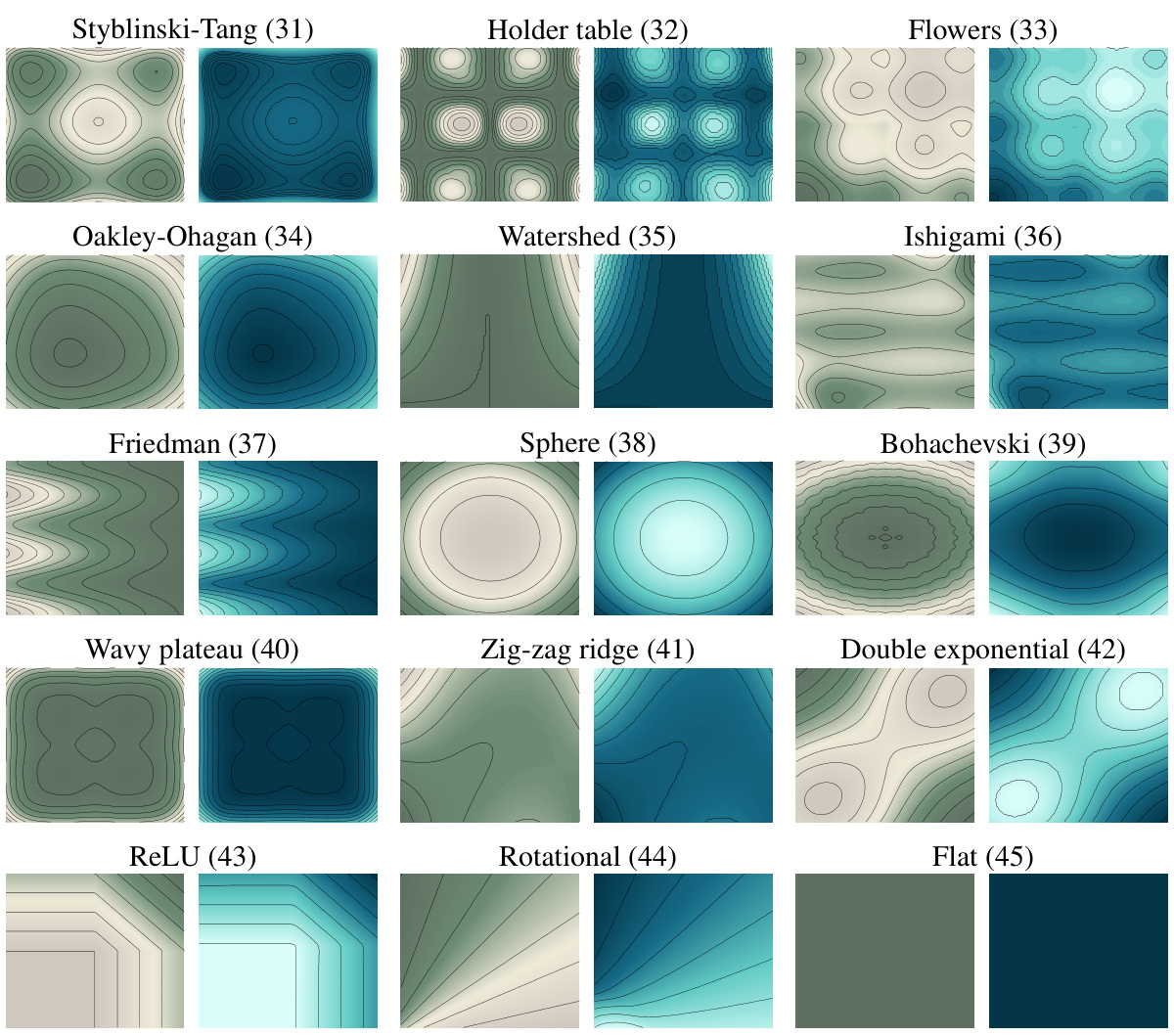

This figure displays the level curves of four different potential functions (Styblinski-Tang, Flowers, Ishigami, and Friedman) used in the experiments. It shows both the true potentials (in green) and the potentials estimated by the JKOnet* model (in blue). This visual comparison helps to assess the accuracy of the model in learning the underlying energy functionals.

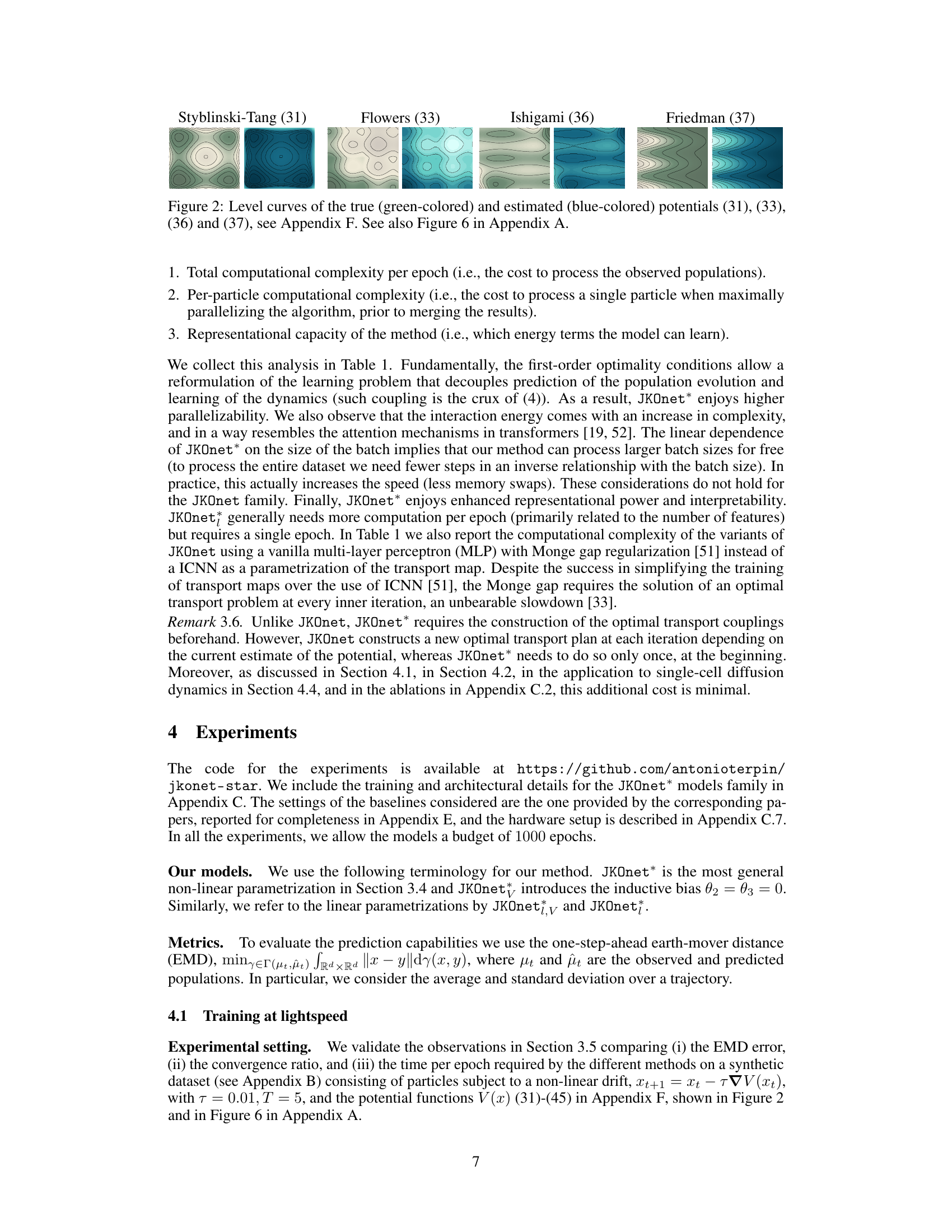

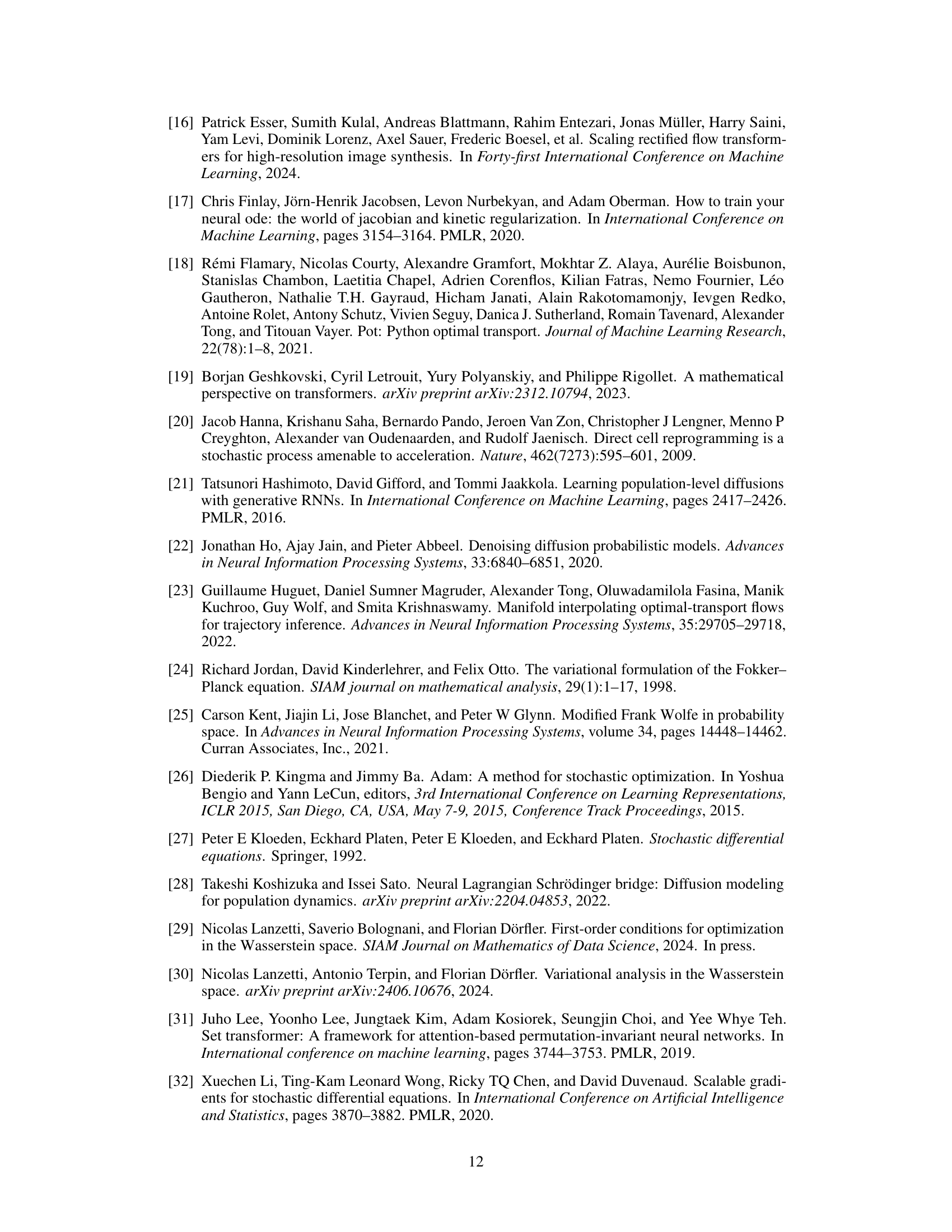

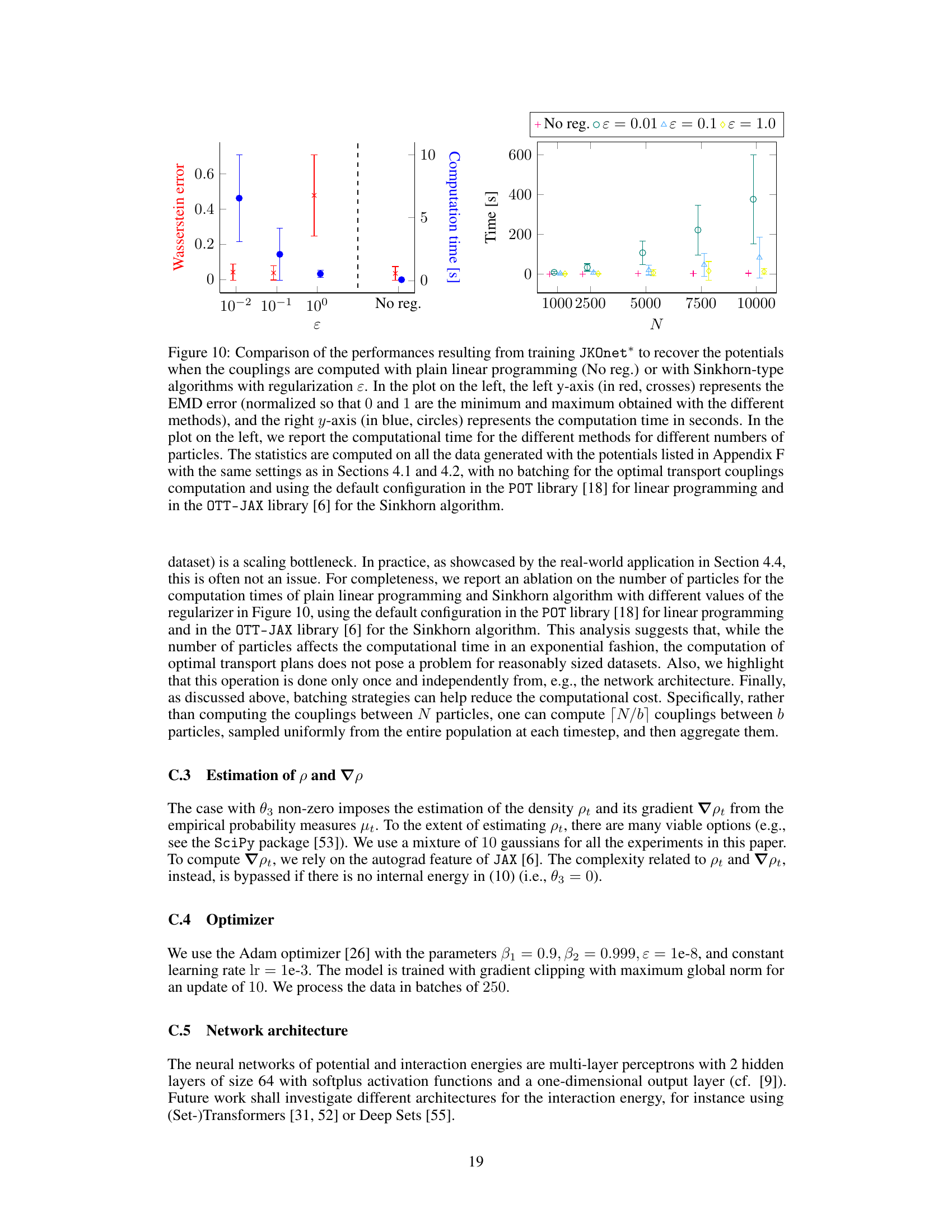

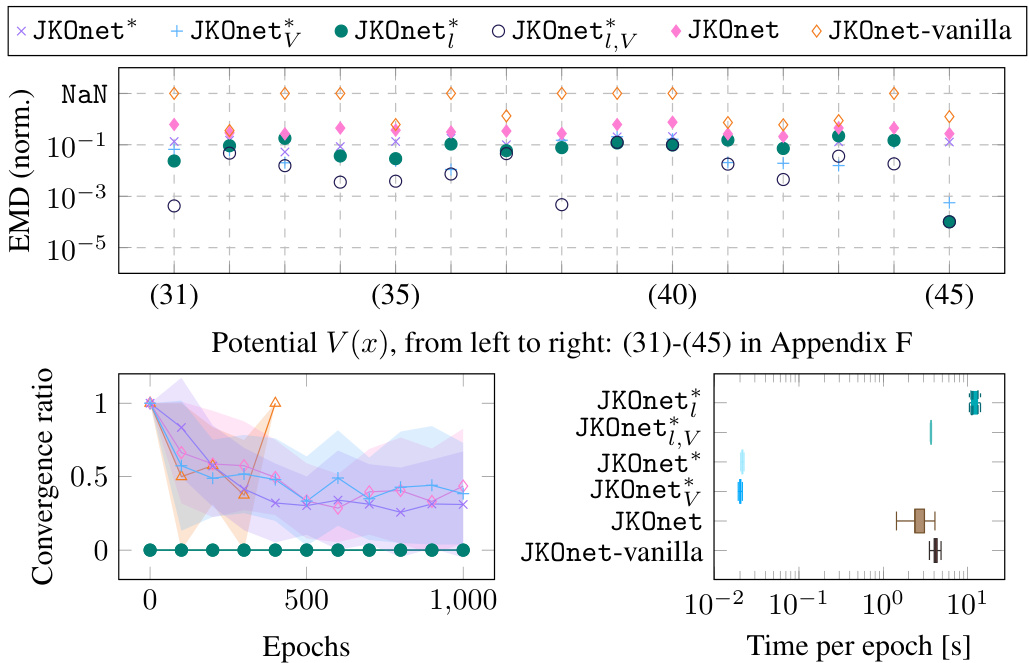

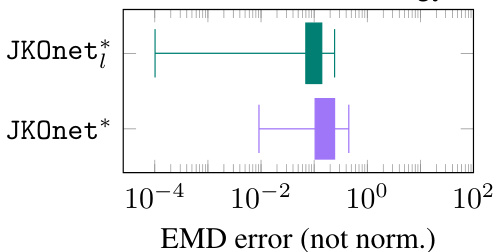

The figure presents a comparative analysis of different models (JKOnet*, JKOnet variants, and baselines) in learning diffusion processes. The scatter plot visualizes the EMD (Earth Mover’s Distance) error for each model on different potential energy functions, with missing values (NaN) indicating divergence. The line plot illustrates the EMD error’s convergence behavior over epochs, highlighting the training efficiency. Finally, the boxplot provides a comparison of the time per epoch for each model.

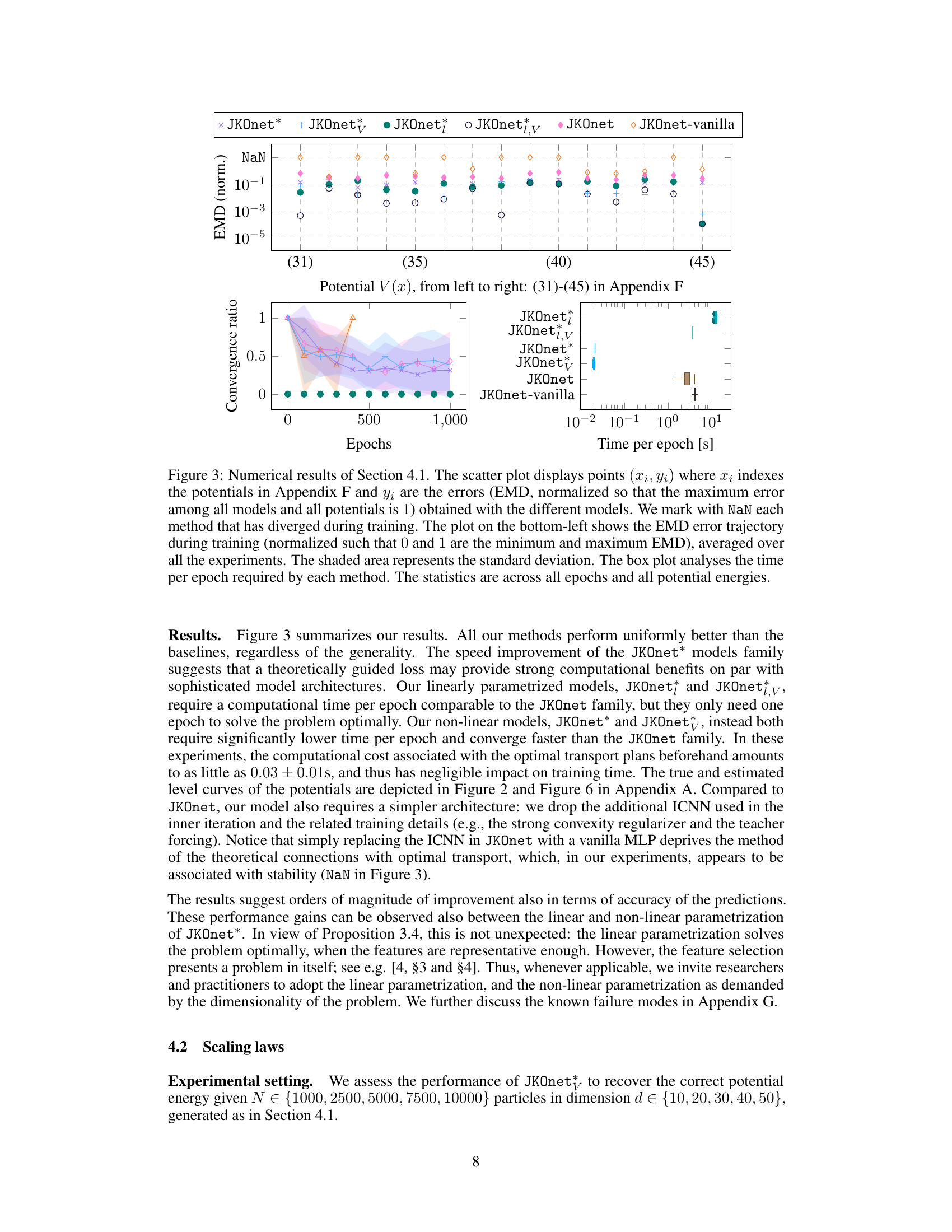

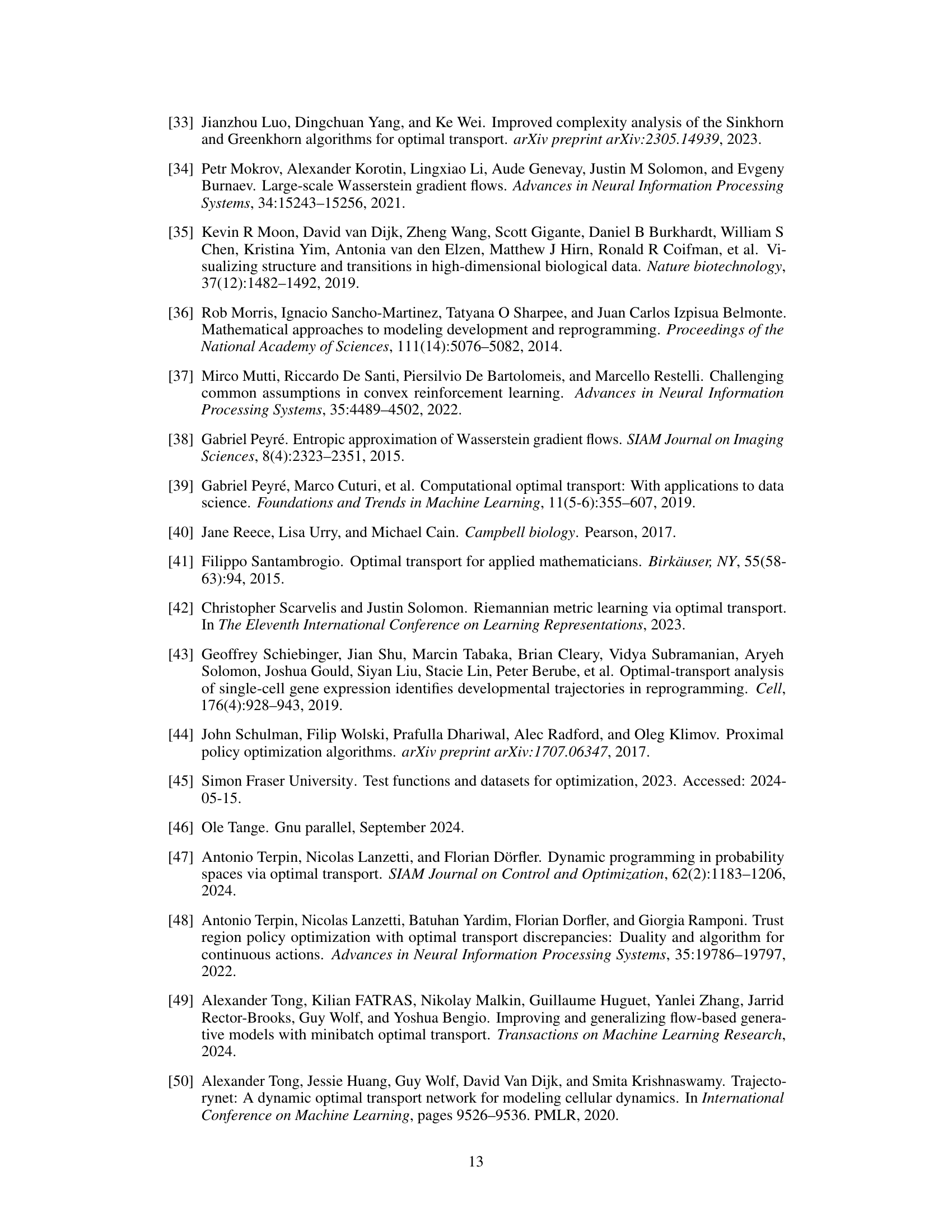

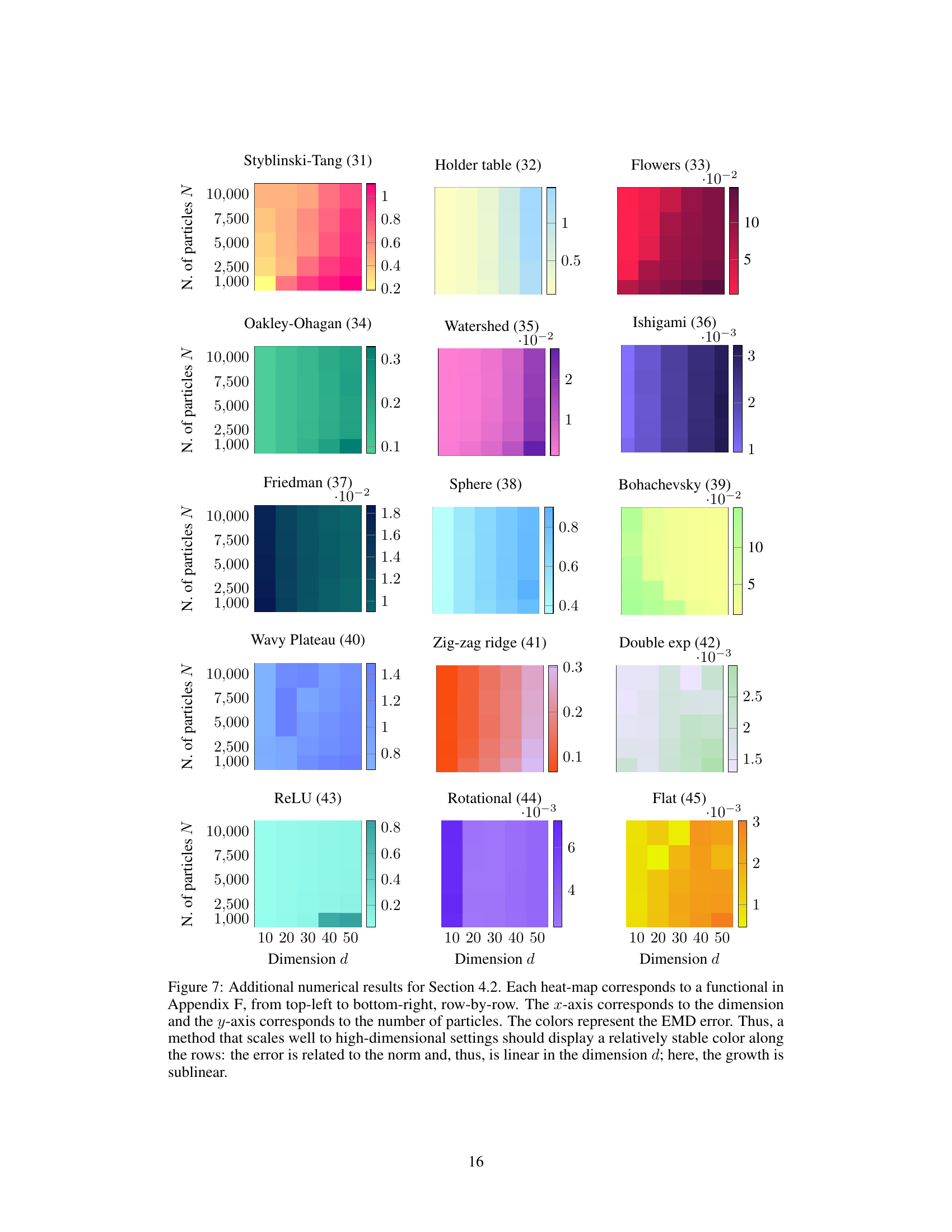

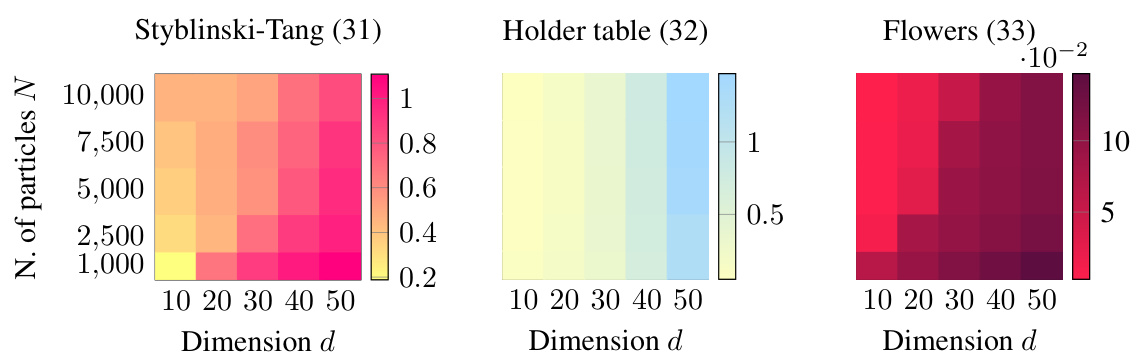

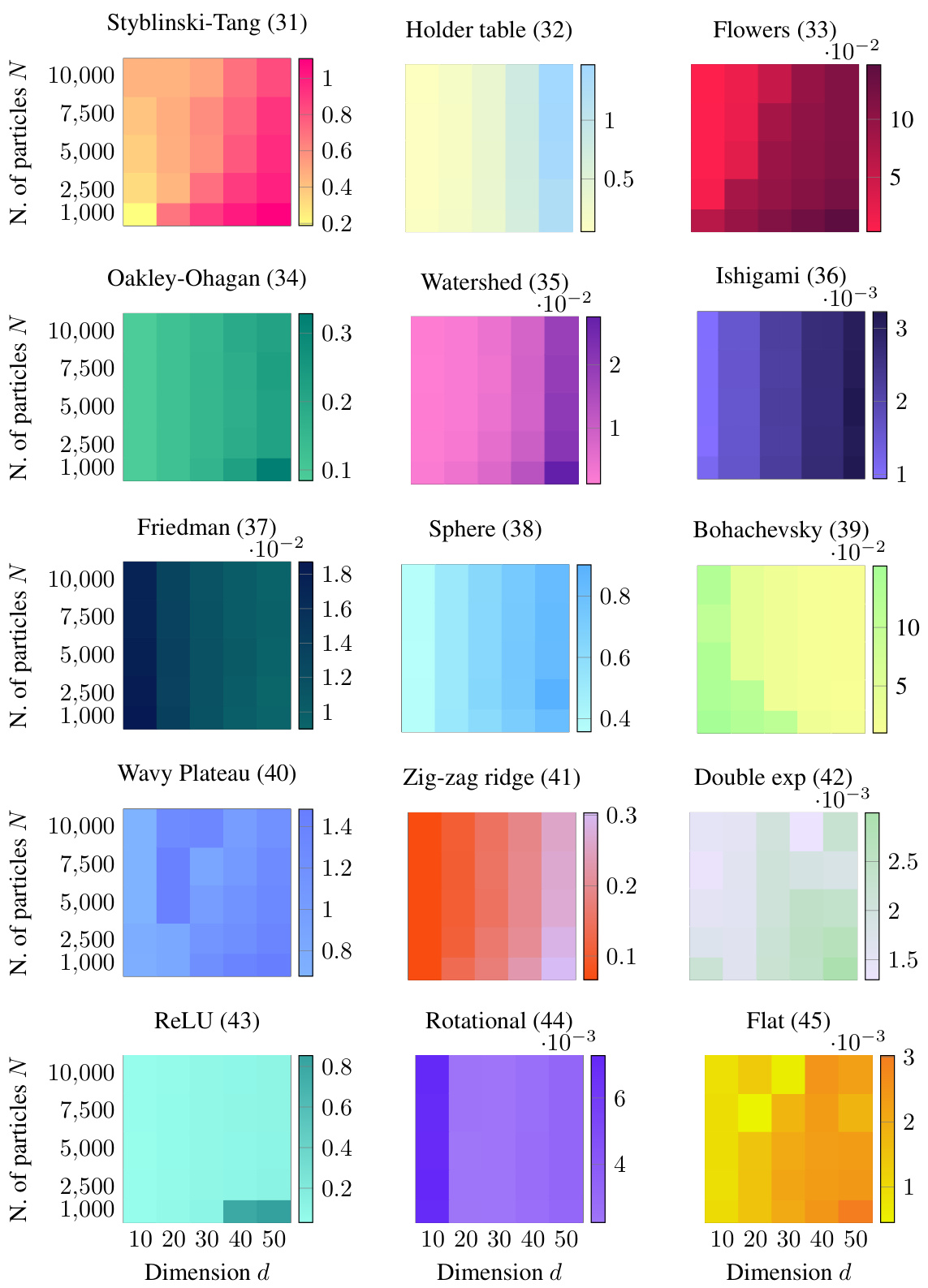

This figure shows the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) error for different numbers of particles and dimensions. The color intensity represents the EMD, with darker colors indicating higher errors. The results suggest that the EMD scales sublinearly with the dimension d, meaning the error does not increase proportionally with the dimension. This is a key finding from the scaling laws experiment in Section 4.2, demonstrating the effectiveness of JKOnet* in high-dimensional settings.

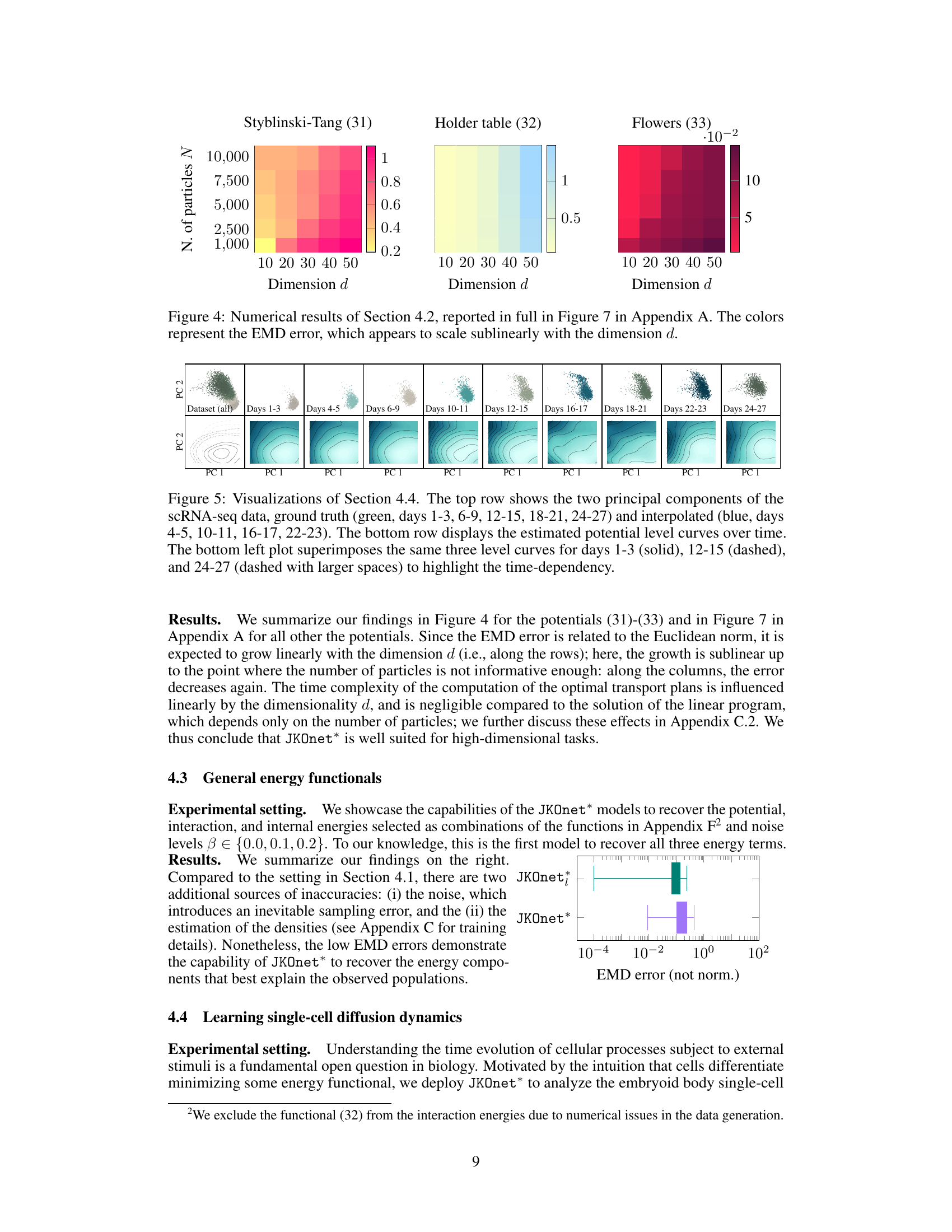

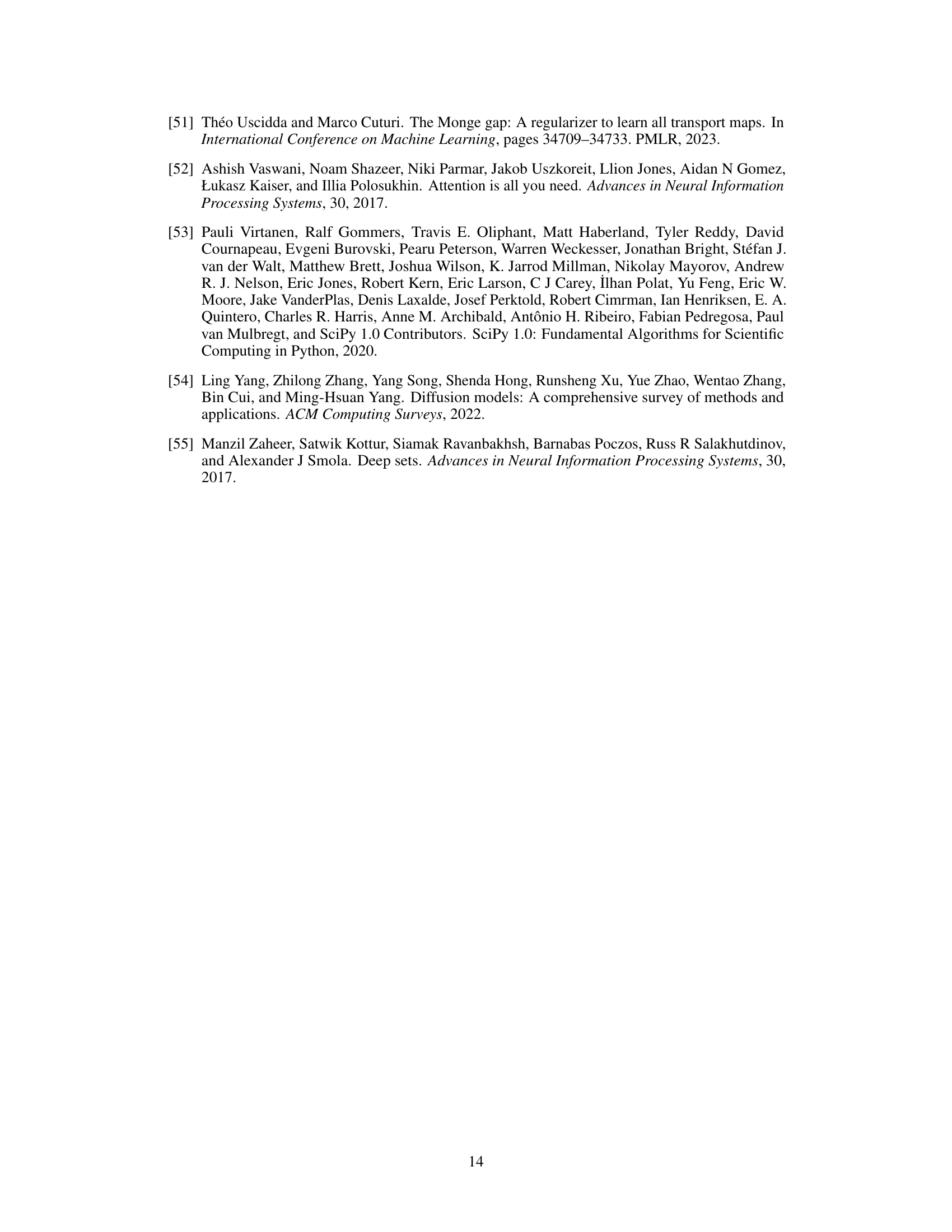

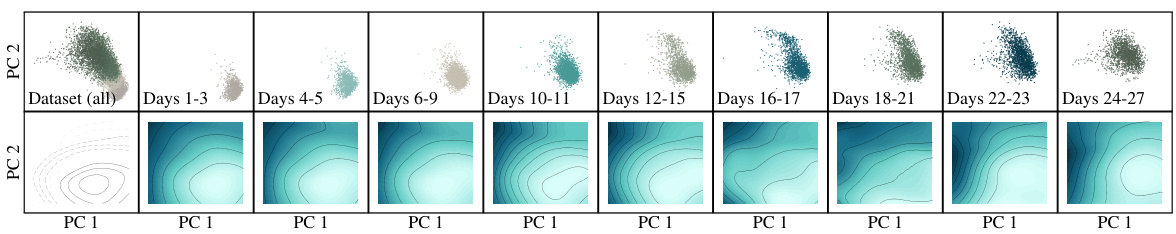

This figure visualizes the results from Section 4.4, which focuses on applying the JKOnet* model to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data to predict cellular processes. The top row displays the first two principal components of the scRNA-seq data, showing both the ground truth (green) and the interpolated predictions (blue) for different time points. The bottom row shows the estimated potential energy level curves over time, providing a visual representation of the energy landscape that drives the cellular processes. The bottom-left subplot highlights the time dependency of the potential energy level curves by superimposing those from three different time points.

This figure presents a comparison of different models’ performance in learning potential energy functions. The scatter plot shows the normalized EMD error for various potential functions, highlighting JKOnet*’s superior accuracy and the time per epoch for each model, demonstrating JKOnet*’s efficiency. The bottom left plot displays the EMD error trajectory over training epochs for a more detailed analysis of model convergence.

This figure shows the level curves of the true and estimated potentials for different test functions described in Appendix F. The true potential is represented in green, and the estimated potential (obtained using JKOnet*) is in blue. Each row shows a different test function, illustrating how the model performs in different scenarios.

This figure displays the results of an experiment testing the scalability of the proposed JKOnet* method. The heatmaps show the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) error for different numbers of particles and dimensions. Lower EMD indicates better performance. The results suggest sublinear scaling of the EMD error with respect to the dimension, indicating good scalability of JKOnet* for high-dimensional problems.

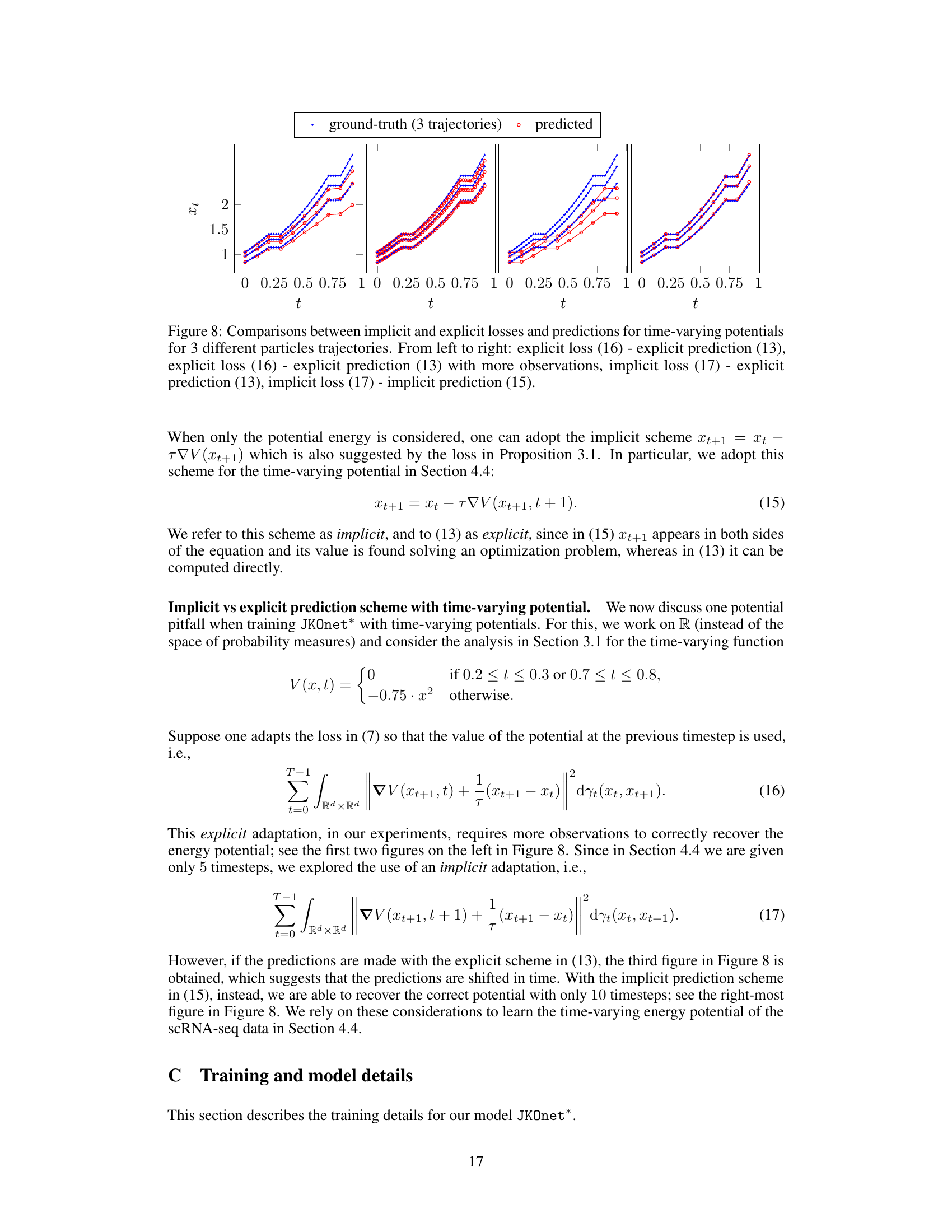

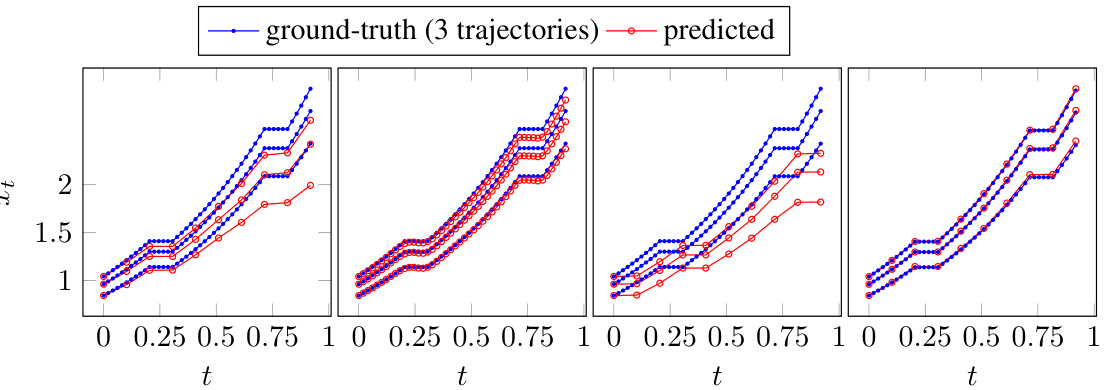

This figure compares the performance of implicit and explicit prediction schemes for time-varying potentials in a diffusion process. It shows four sets of trajectory plots, each representing a different combination of loss function (implicit or explicit) and prediction method (implicit or explicit). The plots illustrate how different methods and parameters affect the accuracy of predictions.

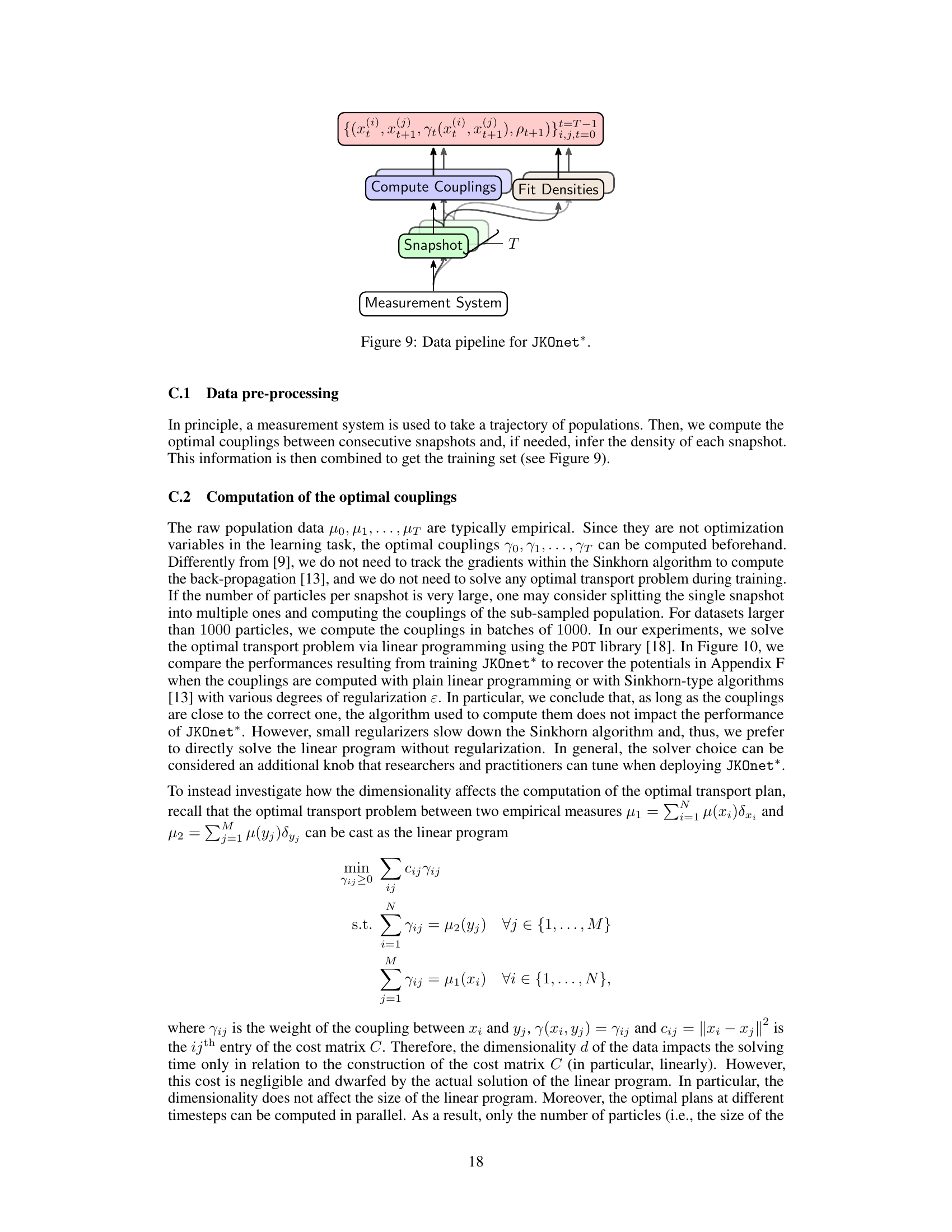

The figure shows the data pipeline for the JKOnet* model. It starts with a measurement system that provides snapshots of the population data at different time steps. These snapshots are then used to compute the optimal couplings between consecutive snapshots, and to fit the densities of each snapshot. The resulting data, which consists of the snapshots, couplings, and densities, is then used to train the JKOnet* model.

The figure presents a comparison of different models’ performance in learning diffusion processes using various potential functions. The scatter plot shows the normalized error (EMD) for each method and potential function, highlighting the superior performance of JKOnet*. The bottom-left plot displays the EMD error trajectory over training epochs for a better understanding of the convergence speed. The box plot visualizes the computation time for each method, confirming the efficiency of JKOnet*.

This figure presents the numerical results of Section 4.1 of the paper. It compares different models’ performance in learning potential energy functions. The scatter plot visualizes the normalized EMD errors, indicating the accuracy of each model. The bottom-left plot shows the EMD error trajectories during training, illustrating convergence speed. Finally, a box plot compares the computational time per epoch for each method.

Full paper#