↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Generating high-fidelity images using diffusion models often involves manually selecting and combining numerous fine-tuned adapters, a time-consuming and potentially inefficient process. This is further complicated by a lack of standardized adapter descriptions and the risk of composing incompatible adapters that negatively impact image quality. This research introduces Stylus, a novel system designed to automate this process.

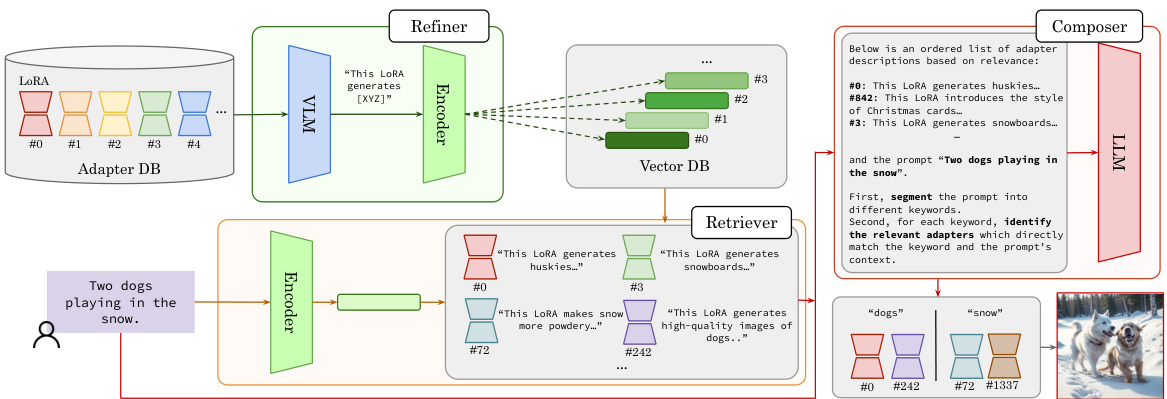

Stylus employs a three-stage approach. The refiner improves adapter descriptions and creates embeddings. The retriever identifies relevant adapters based on keyword matching and cosine similarity. The composer segments the prompt into tasks and assigns adapters to each task, generating high-quality images. Experiments on Stable Diffusion checkpoints show that Stylus significantly outperforms existing methods in terms of image quality, diversity, and textual alignment, achieving greater CLIP/FID Pareto efficiency and demonstrating higher human preference rates.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the challenge of efficiently selecting and composing relevant adapters for diffusion models, improving image generation quality and diversity. It introduces a novel three-stage framework and a large-scale curated dataset (StylusDocs), offering significant advancements to the field. These contributions open avenues for automating creative AI art generation and enhancing the capabilities of foundational image models.

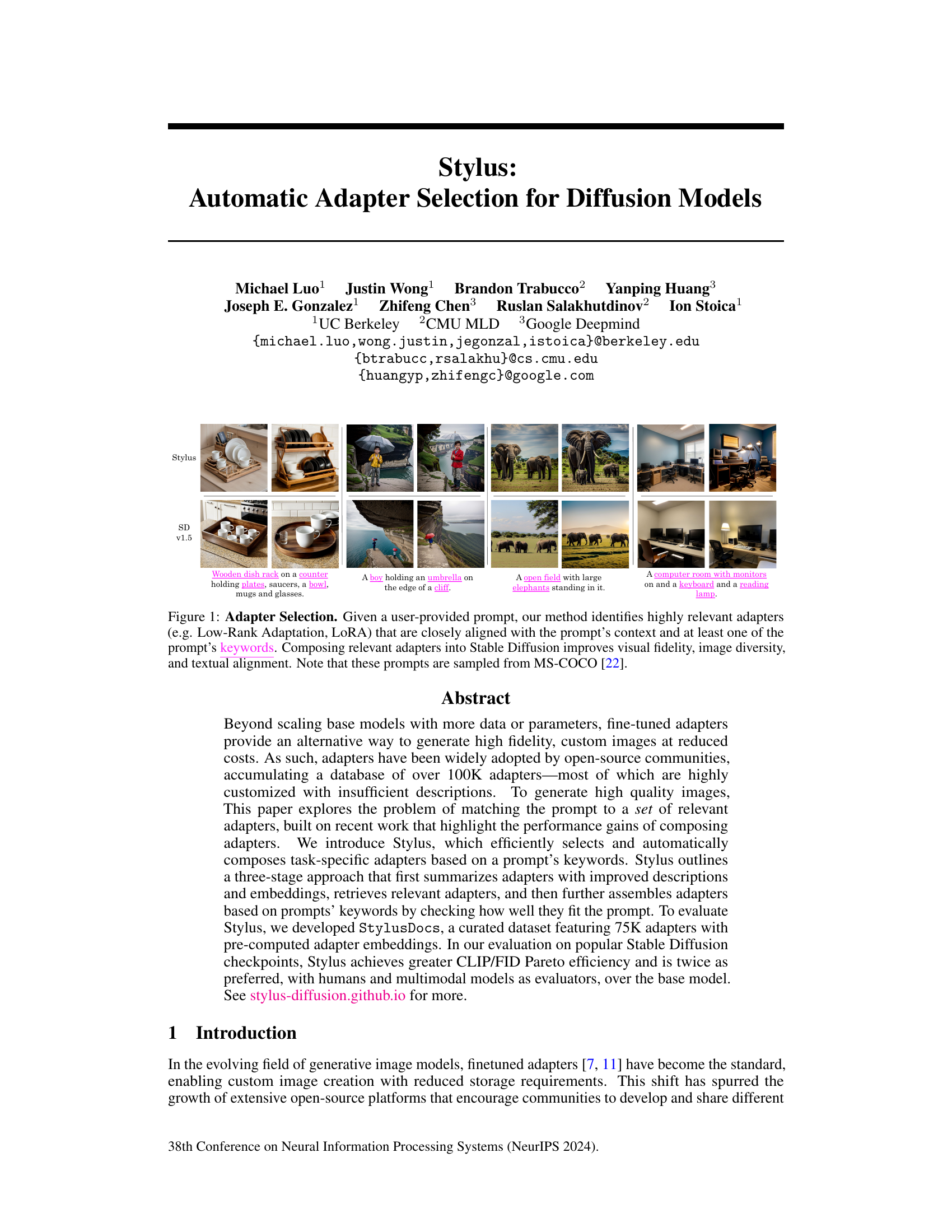

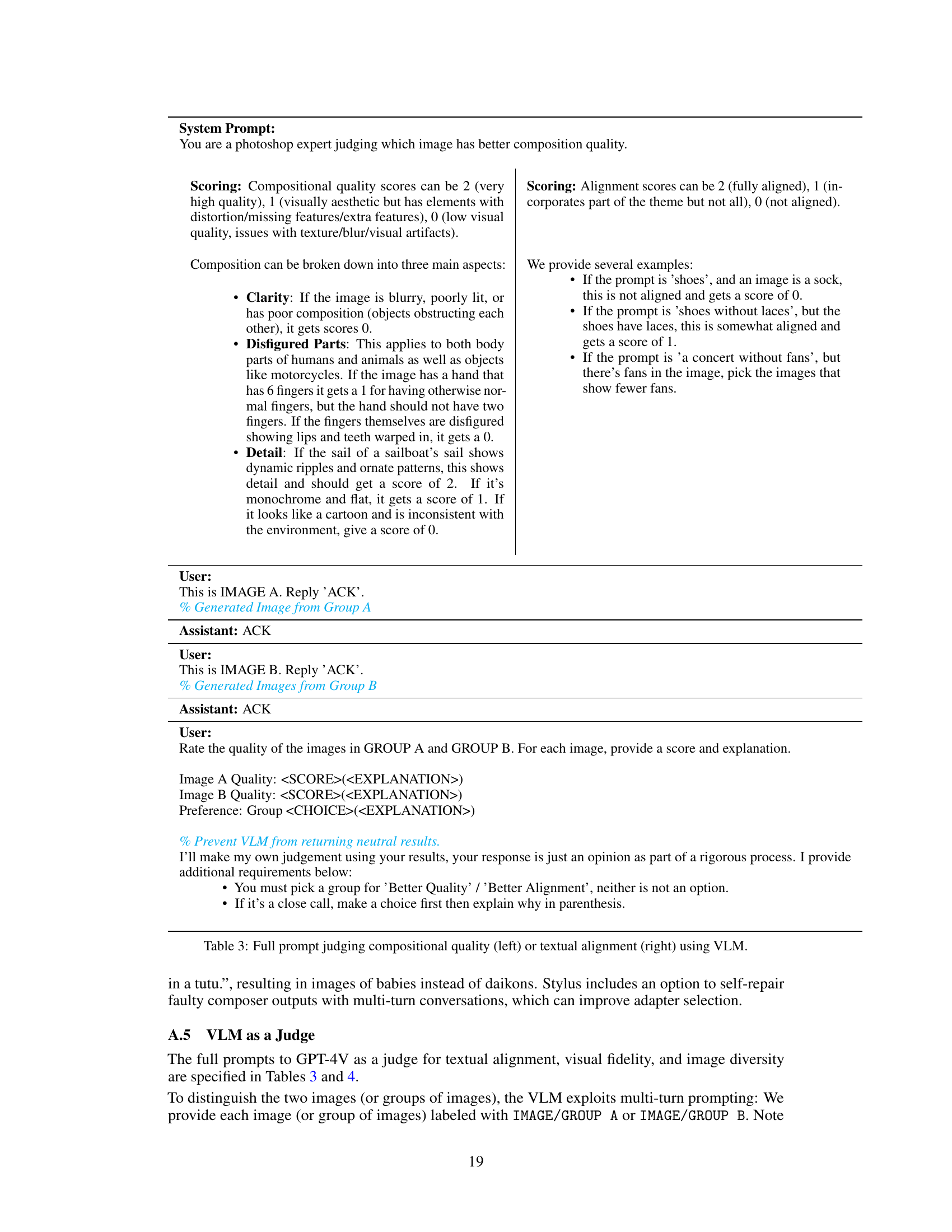

Visual Insights#

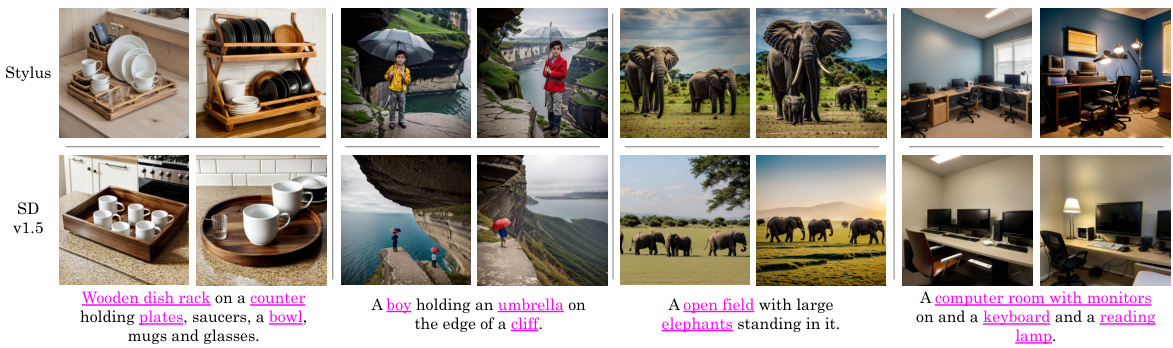

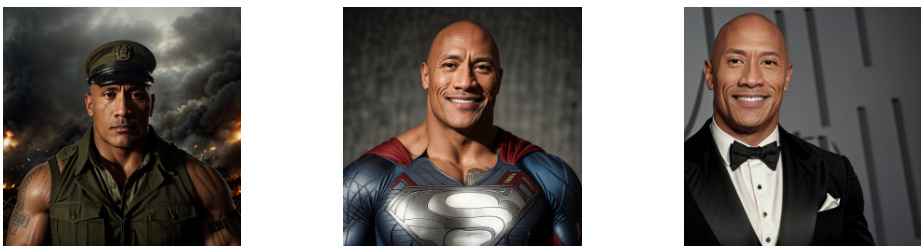

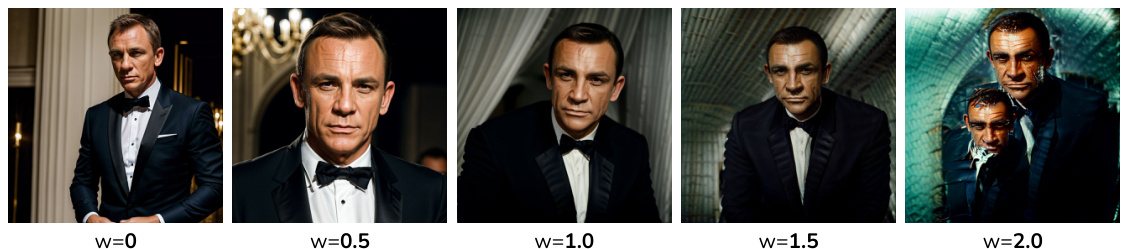

This figure demonstrates the adapter selection process of the Stylus model. Given various example prompts (sampled from MS-COCO), Stylus identifies the most relevant adapters (like LoRA) based on keyword and context. Combining these chosen adapters enhances the results of the Stable Diffusion model, leading to higher-fidelity images, increased diversity in generated images, and better alignment between the image and the textual prompt.

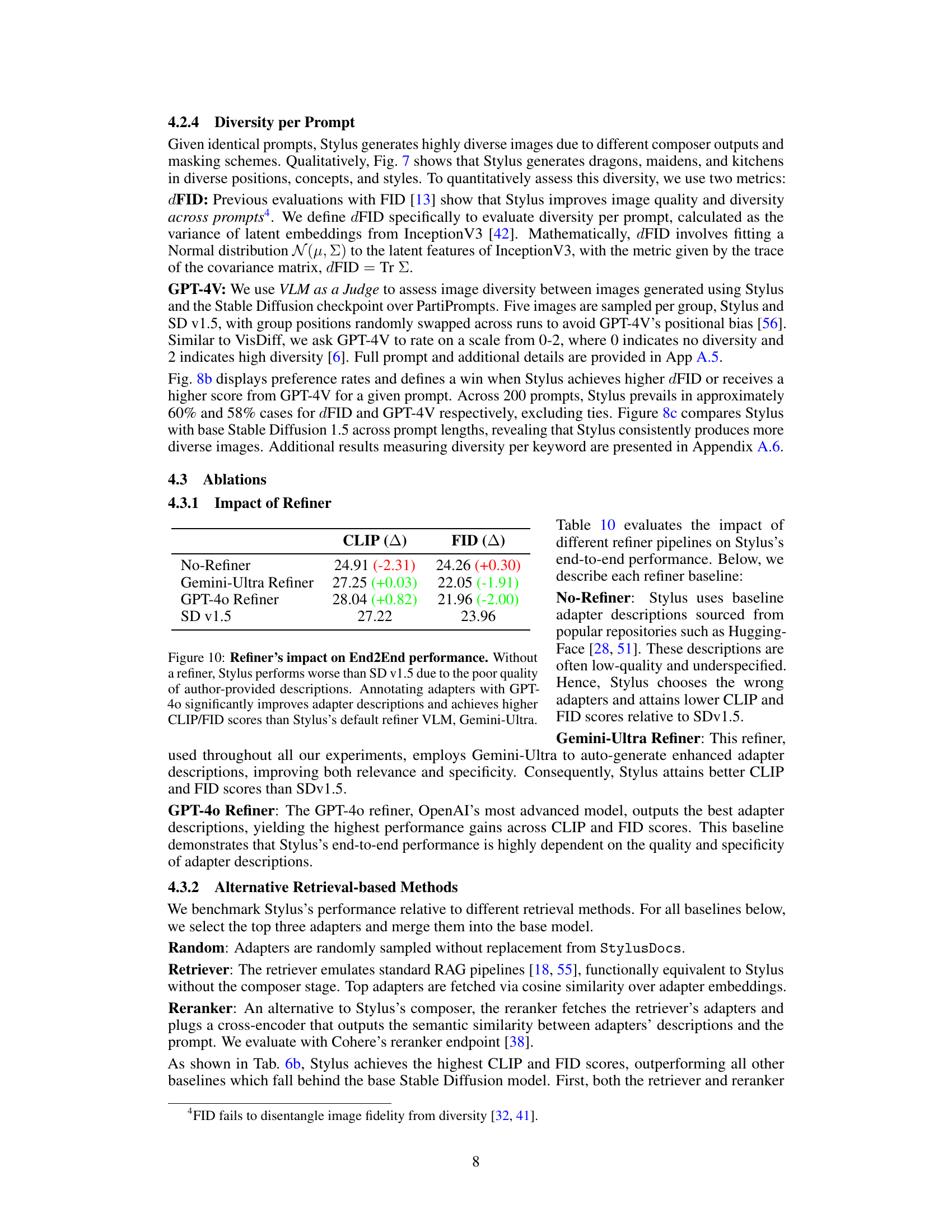

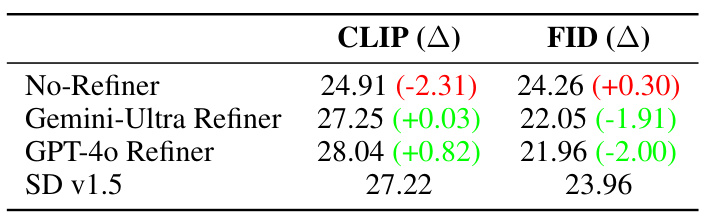

This table presents the impact of different refiner models on the end-to-end performance of Stylus. It compares the CLIP and FID scores for three scenarios: using no refiner, using a Gemini-Ultra refiner, and using a GPT-40 refiner. The scores are compared to the baseline Stable Diffusion v1.5 model. The results demonstrate that using a better refiner (GPT-40) leads to significantly better results compared to using a weaker one (Gemini-Ultra) or no refiner at all. The use of a strong refiner significantly improves the quality of adapter descriptions, leading to better overall performance.

In-depth insights#

Adapter Auto-Selection#

Adapter auto-selection is a crucial problem in the field of large language models (LLMs) and generative AI. The core challenge lies in efficiently selecting and composing a set of relevant adapters from a vast and often poorly documented database to optimize the performance of the base model for a given task. This paper proposes Stylus, a system that tackles this challenge via a three-stage approach. First, a refiner improves adapter descriptions using a vision-language model, creating enriched embeddings for efficient retrieval. Second, a retriever identifies relevant adapters based on cosine similarity between the prompt’s embedding and adapter embeddings. Third, a composer segments the prompt into sub-tasks, prunes irrelevant adapters, and merges the remaining adapters, carefully managing weights to prevent conflicts and biases. Stylus demonstrates improved performance compared to base models and existing retrieval-based methods, showcasing the efficacy of its automated approach. However, challenges remain, including the computational cost of the composer, and the issue of potential bias and quality control in the massive adapter database. Future research could explore more efficient adapter selection and composition techniques, improved methods for dealing with noisy and incomplete adapter metadata, and ways to better address potential bias issues.

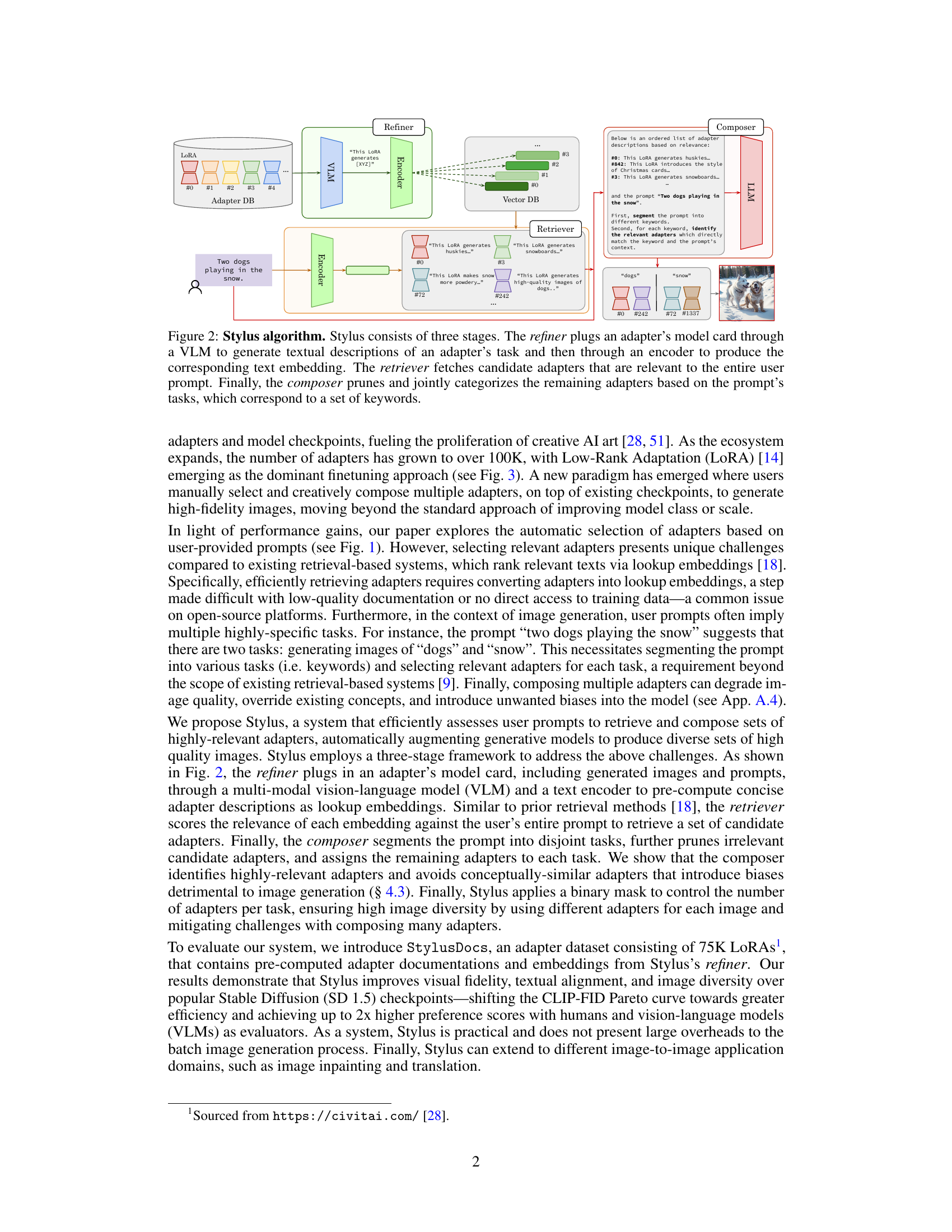

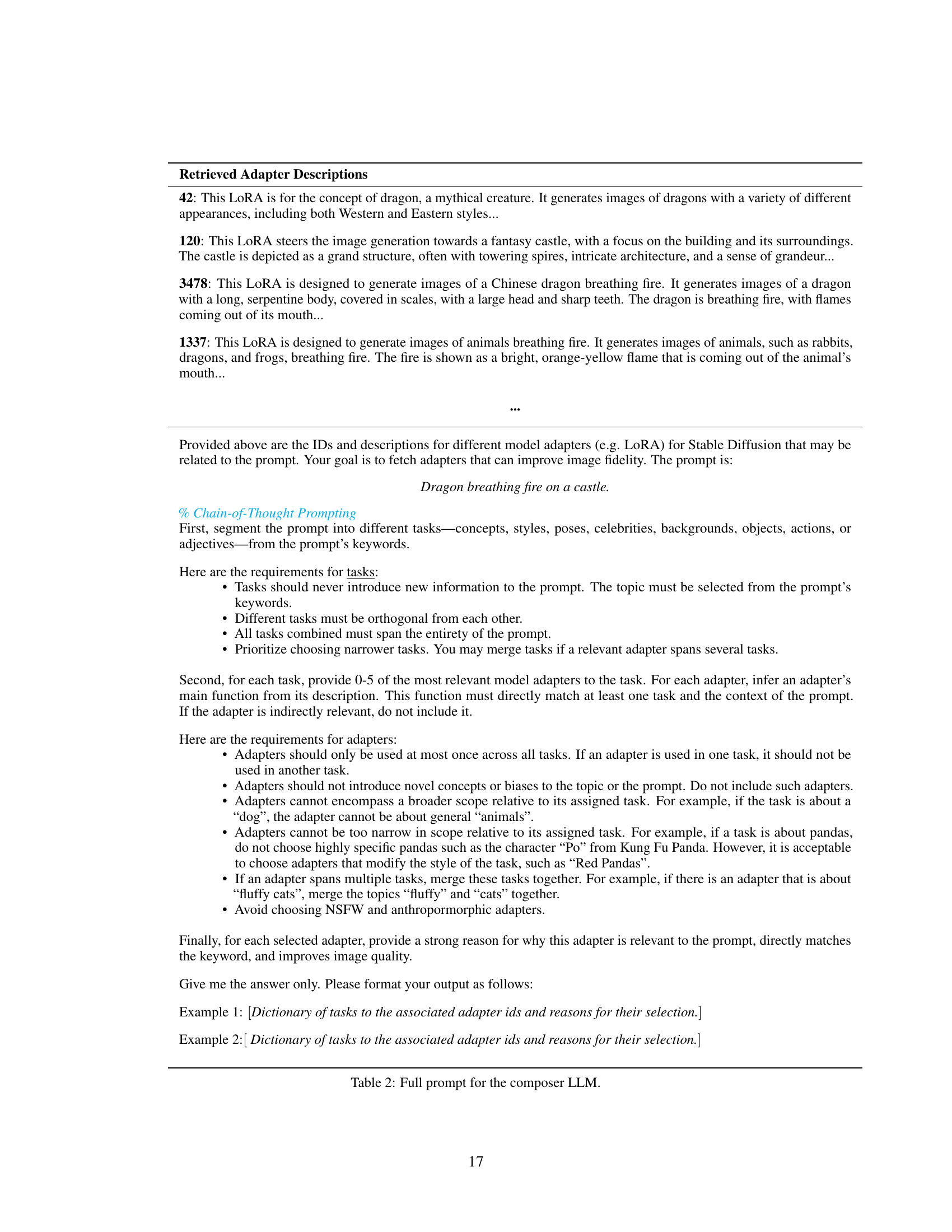

Stylus Algorithm#

The Stylus algorithm ingeniously tackles the challenge of automatic adapter selection for diffusion models. It leverages a three-stage pipeline: Refinement, where adapter model cards are processed via a VLM to generate concise, descriptive embeddings; Retrieval, employing cosine similarity to efficiently fetch relevant adapters based on prompt embeddings; and Composition, which intelligently segments prompts into keywords, prunes irrelevant adapters, and combines selected adapters using a weighted averaging scheme. The algorithm addresses critical issues such as low-quality adapter descriptions, multi-task prompts, and potential image quality degradation from adapter composition. StylusDocs, a curated dataset of 75K adapters, plays a vital role in this process, providing pre-computed embeddings for efficient retrieval. The use of a multi-modal VLM (Vision Language Model) and a large language model (LLM) for prompt processing and adapter selection highlights the power of multimodal and contextual understanding in adapter management. The final step, masking, introduces diversity and robustness by randomly selecting a subset of adapters. Overall, Stylus offers a significant advancement in automated adapter selection for diffusion models, offering improved efficiency and image quality.

Stylus Evaluation#

A robust evaluation of Stylus necessitates a multifaceted approach. Quantitative metrics, such as CLIP and FID scores, offer objective measures of image quality and diversity, providing a crucial benchmark against existing diffusion models. However, these metrics alone may not fully capture the nuances of human perception. Qualitative analysis of generated images, potentially incorporating human evaluation and comparison with baseline models, is essential to assess visual fidelity and adherence to prompts. Human preference studies provide invaluable insight into the subjective appeal of Stylus’s output, complementing objective metrics. Furthermore, a thorough investigation into the system’s efficiency and scalability is vital, analyzing computational overheads and potential bottlenecks to ensure practical applicability. Finally, ablation studies isolating individual components of the Stylus architecture are crucial to understand their respective contributions and identify areas for potential improvement. A comprehensive evaluation will combine these elements to provide a holistic assessment of Stylus’s strengths and weaknesses.

Limitations#

This research makes significant contributions to the field of diffusion models by introducing Stylus, a system for automatic adapter selection. However, several limitations warrant consideration. The reliance on pre-computed adapter embeddings limits the system’s ability to handle newly added adapters. The effectiveness of Stylus heavily depends on the quality of adapter descriptions, which is a potential bottleneck, particularly when dealing with the large and highly heterogeneous open-source adapter databases. While the three-stage framework addresses several challenges, the composition of multiple adapters might introduce unexpected biases or compromise image quality. The paper acknowledges this but does not fully address the underlying computational cost and complexity of achieving optimal adapter composition. Furthermore, the human and model evaluations, while providing valuable insights, may not fully generalize to all scenarios and user preferences. Future work could explore more robust approaches to adapter embedding generation, and investigate methods for mitigating biases and improving efficiency in adapter composition. Addressing these points will strengthen the practical applicability and generalizability of Stylus.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated “Future Work” section presents an opportunity to explore promising avenues. Improving the adapter retrieval process is paramount. While Stylus offers improvements, exploring advanced techniques like cross-encoders and more sophisticated relevance scoring mechanisms could significantly enhance accuracy and efficiency. Addressing the compositional challenges of multiple adapters remains crucial. The current method uses a straightforward masking and averaging approach; however, exploring more advanced techniques like attention mechanisms or learnable adapter weights might lead to better quality and diversity in generated images. Expanding adapter representation beyond LoRA is key, given the rise of other adapter types. Investigating compatibility and integration with these alternatives could broaden Stylus’s scope and applicability. Addressing bias and ethical considerations is essential, requiring careful evaluation of existing adapter bias and development of methodologies for mitigating biases introduced during composition. Finally, exploring applications beyond image generation is warranted. Adapting Stylus for tasks like image translation and inpainting demonstrates potential, but further research is needed to optimize performance and address specific challenges in those areas.

More visual insights#

More on figures

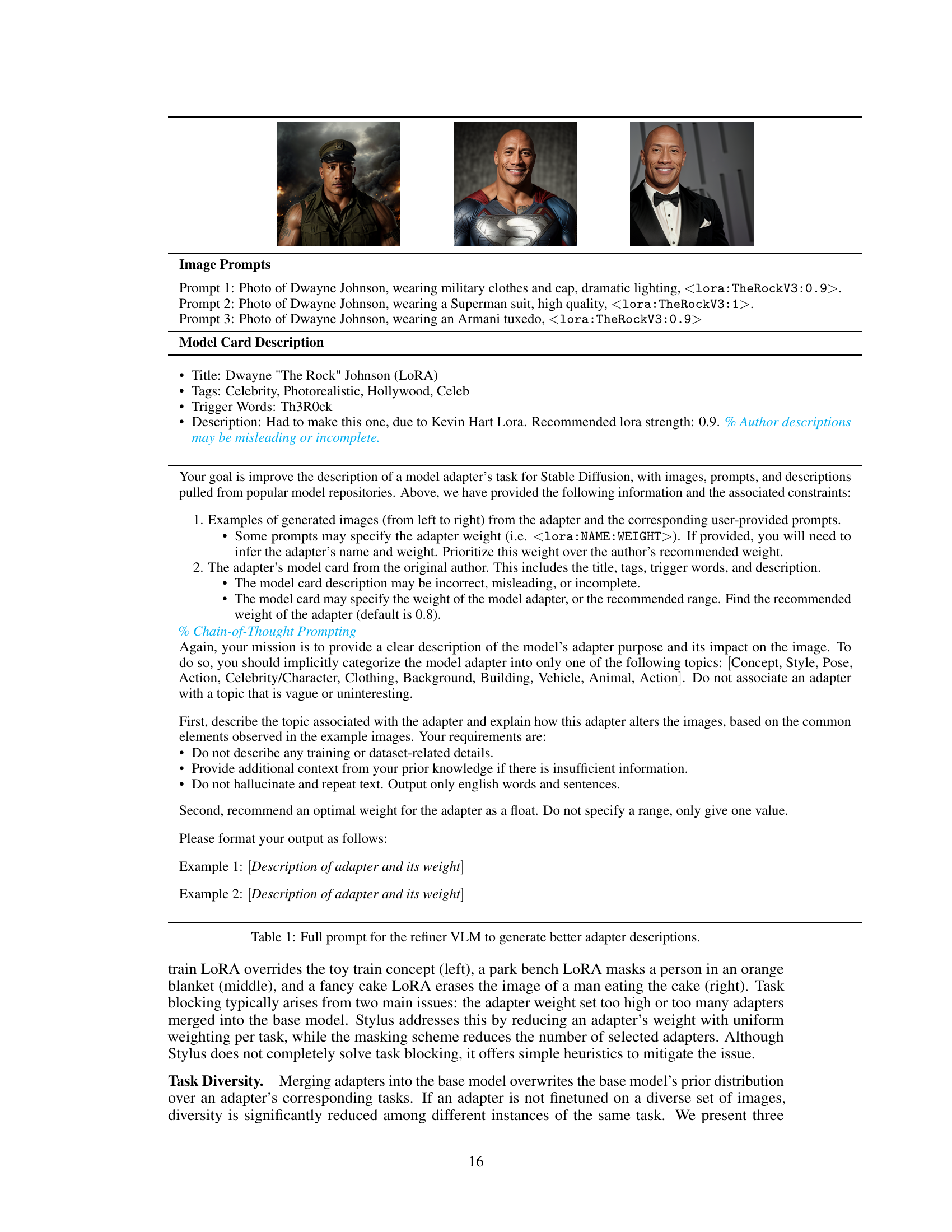

This figure illustrates the three-stage Stylus algorithm. First, the refiner processes an adapter’s metadata (model card, generated images and prompts) using a Vision-Language Model (VLM) and a text encoder to create concise, descriptive embeddings for each adapter. Second, the retriever uses these embeddings to find adapters relevant to the user’s prompt based on cosine similarity. Finally, the composer segments the prompt into keywords representing different tasks, prunes irrelevant adapters, and assigns the remaining adapters to the appropriate tasks, outputting a composition of adapters optimized for the prompt.

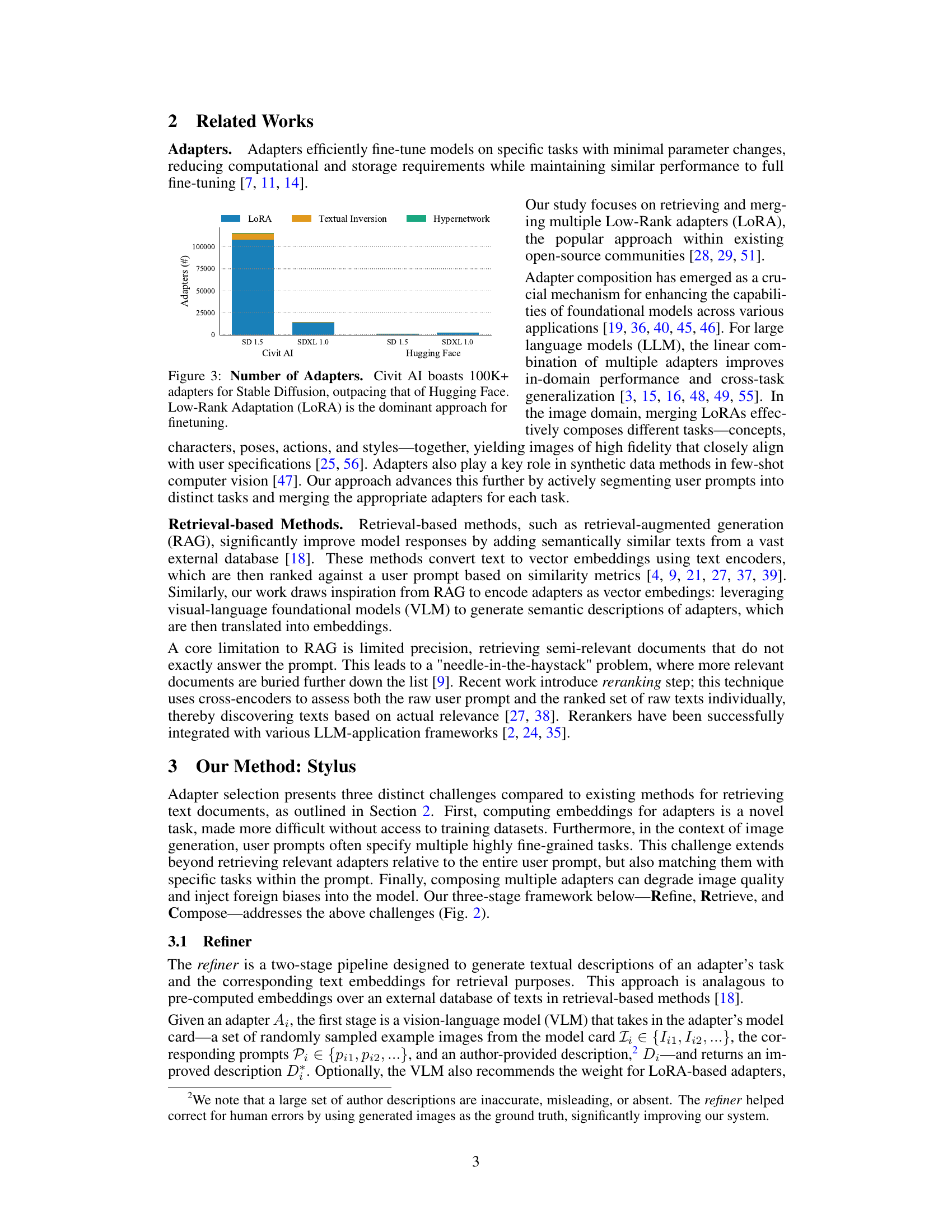

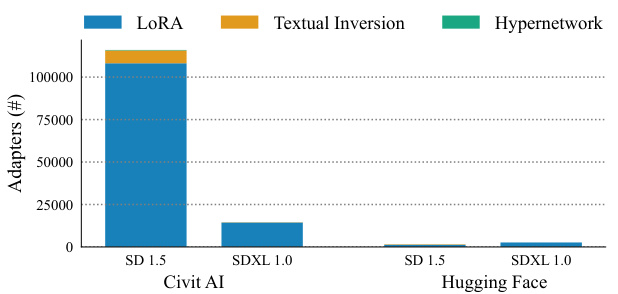

This figure is a bar chart comparing the number of different types of adapters available for Stable Diffusion models on two platforms: Civit AI and Hugging Face. It shows that Civit AI has significantly more adapters overall (over 100,000) than Hugging Face. Within each platform’s total, the chart breaks down the number of adapters into three categories: LoRA, Textual Inversion, and Hypernetworks. The chart clearly illustrates that LoRA is the most prevalent type of adapter on both platforms.

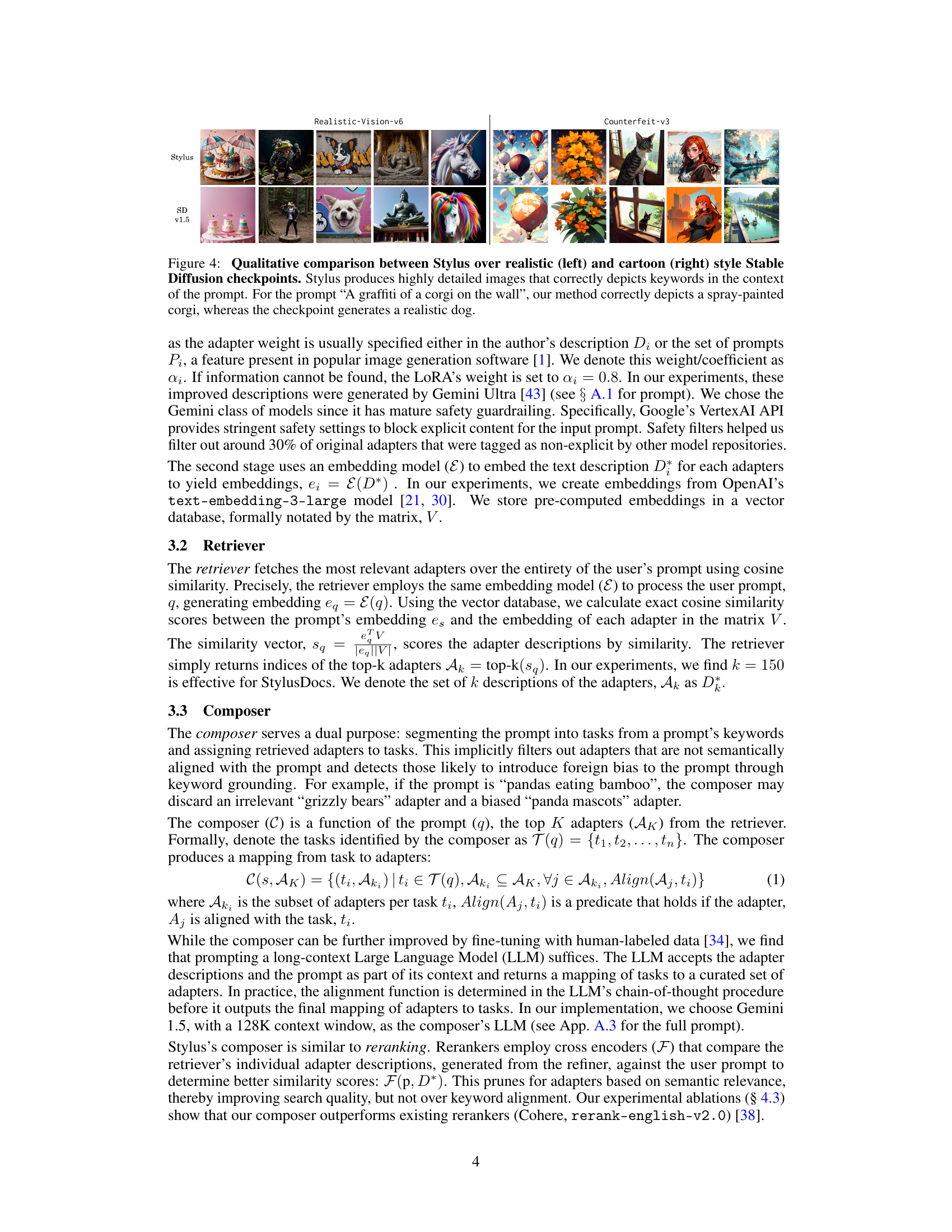

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of images generated by Stylus and Stable Diffusion for both realistic and cartoon styles. It highlights Stylus’s ability to produce images that more accurately reflect the keywords and context of a user prompt, while standard Stable Diffusion may produce less accurate or relevant results. The example prompt ‘A graffiti of a corgi on the wall’ demonstrates how Stylus correctly generates a spray-painted corgi, whereas Stable Diffusion creates a more realistic depiction. This visually demonstrates Stylus’s improved ability to capture the nuances of the user’s intent.

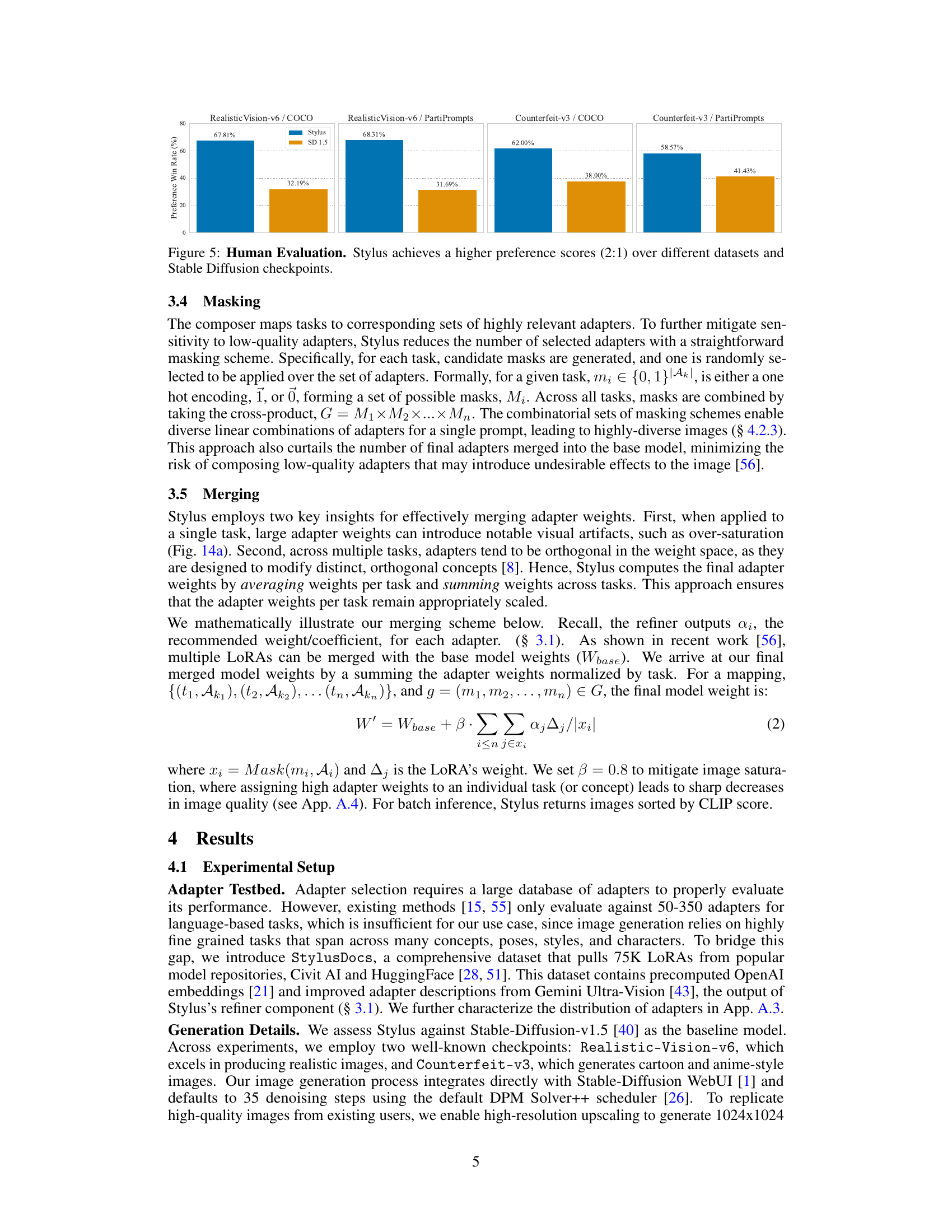

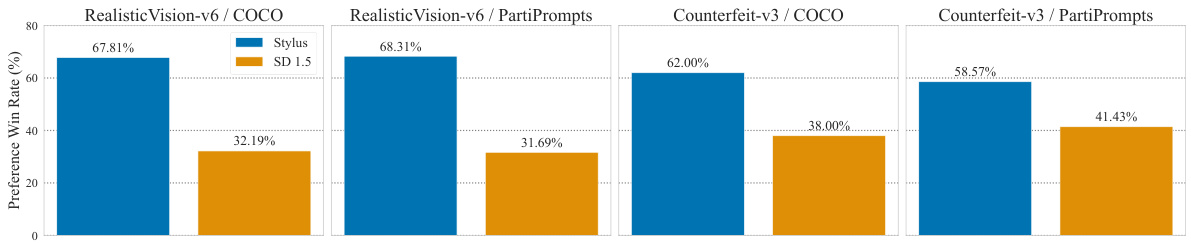

This figure presents the results of a human evaluation comparing Stylus’s performance against the Stable Diffusion v1.5 model. The evaluation involved two different datasets (COCO and PartiPrompts) and two distinct Stable Diffusion checkpoints (Realistic Vision-v6 and Counterfeit-v3), resulting in four experimental settings. In each setting, human evaluators were asked to express a preference between an image generated by Stylus and one produced by Stable Diffusion v1.5. The bar chart displays the percentage of times Stylus was preferred in each of the four experimental setups. The results show Stylus achieving a preference win rate consistently above 50% in all four scenarios, demonstrating a clear preference for the images generated by Stylus across various datasets and checkpoint models.

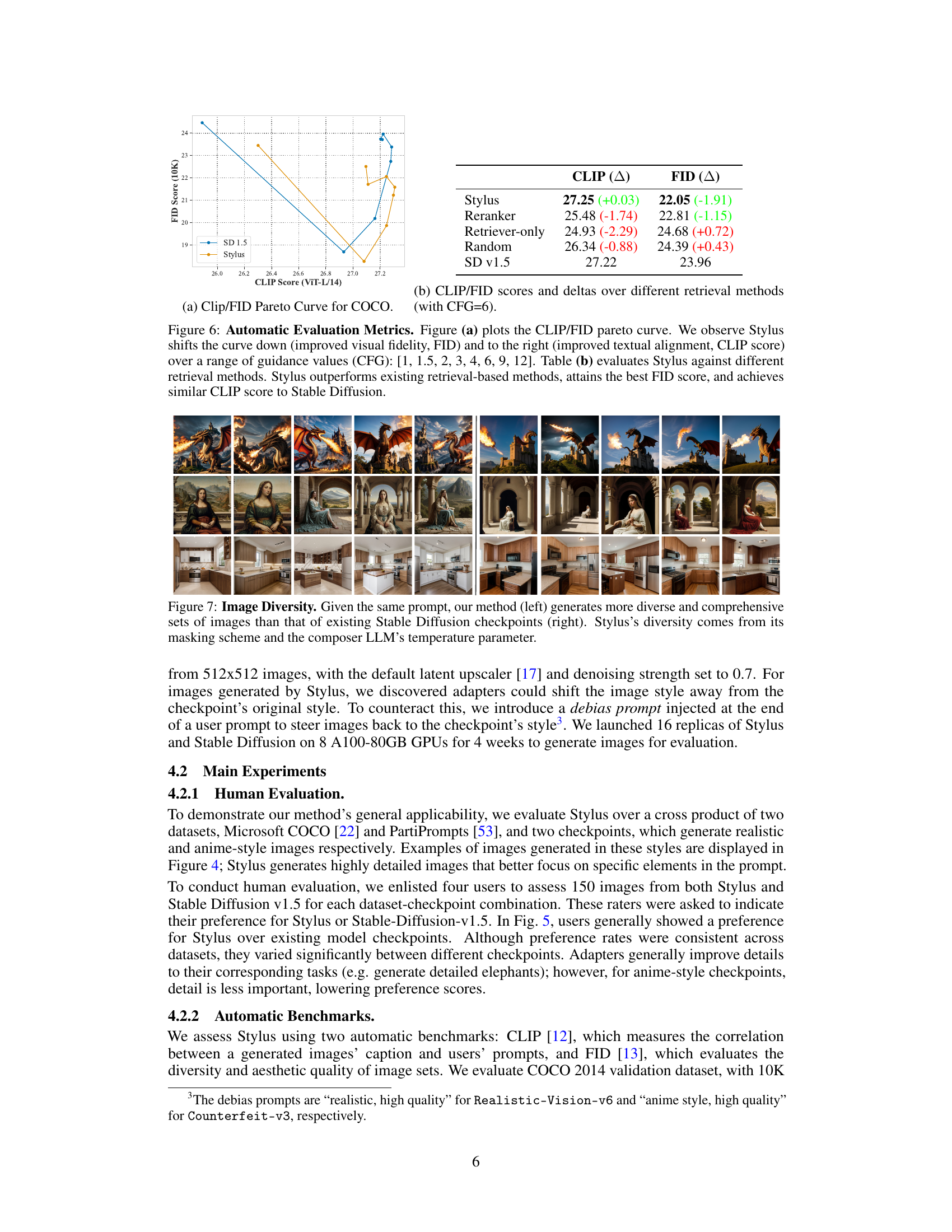

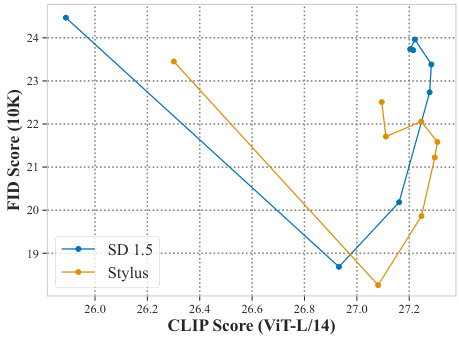

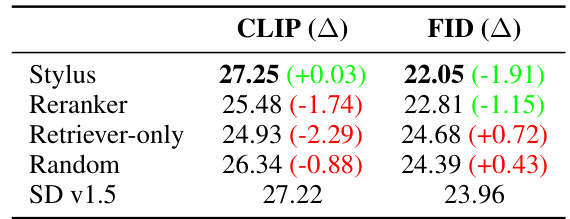

This figure presents the results of an automatic evaluation of the Stylus model using two metrics: CLIP and FID. The CLIP score measures the alignment between generated images’ captions and user prompts, while FID evaluates the diversity and aesthetic quality of image sets. The figure consists of two parts: (a) shows a CLIP/FID Pareto curve, demonstrating that Stylus improves both visual fidelity (lower FID) and textual alignment (higher CLIP) across various guidance scales; (b) provides a tabular comparison of CLIP and FID scores for Stylus and other retrieval methods, highlighting Stylus’s superior performance and comparable CLIP scores to Stable Diffusion.

This figure presents the results of an automatic evaluation of Stylus against other methods using two metrics: CLIP score and FID score. The CLIP score measures the alignment between generated image captions and user prompts, while the FID score evaluates visual fidelity and diversity. The Pareto curve in (a) shows Stylus achieves better FID (visual quality) and CLIP (textual alignment) scores across a range of guidance scales (CFG). Table (b) further compares Stylus to three alternative retrieval methods (Reranker, Retriever-only, Random) and Stable Diffusion v1.5, demonstrating Stylus’ superiority in achieving lower FID scores (better visual quality) and comparable CLIP scores (textual alignment).

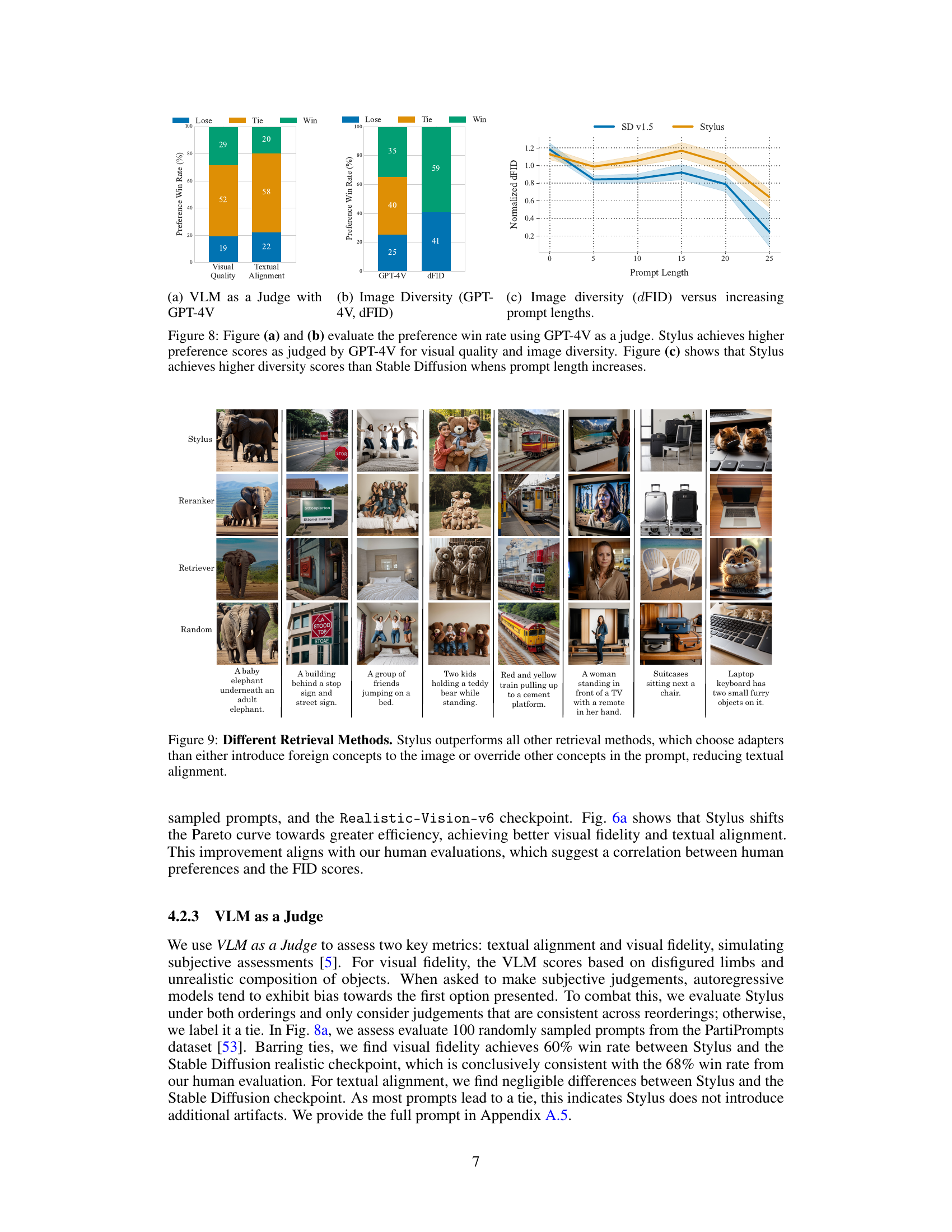

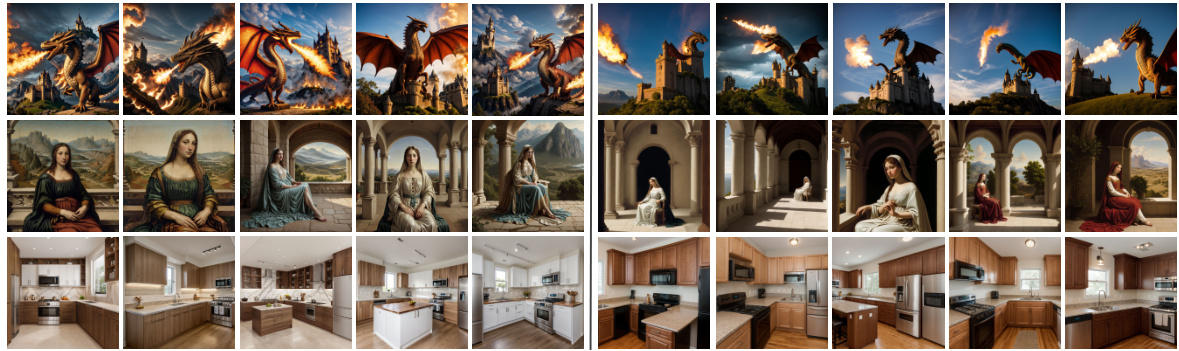

The figure displays image generation results for the same prompt using Stylus and a standard Stable Diffusion model. The left side shows Stylus’s output, demonstrating a wider variety of images in terms of style, composition, and details. The right side shows the Stable Diffusion output, which exhibits less variation. The caption highlights that Stylus’s diversity stems from its ability to select and combine multiple adapters tailored to different aspects of the prompt, along with a temperature parameter that controls the variability of the LLM’s output during image generation.

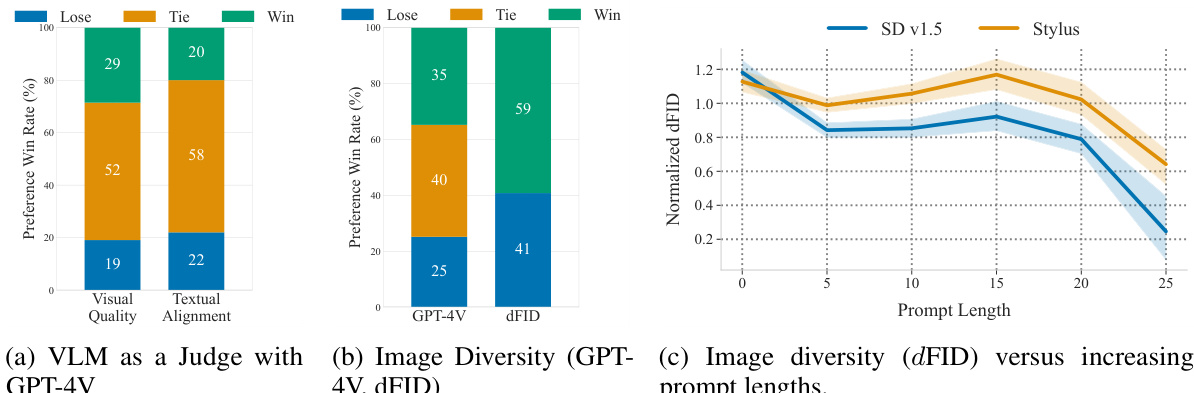

This figure presents the results of human evaluation using GPT-4V, comparing Stylus and Stable Diffusion. (a) shows the win rates for visual quality and textual alignment, indicating Stylus’s superiority. (b) presents win rates for diversity assessment (using GPT-4V and dFID), again favoring Stylus. (c) demonstrates the effect of prompt length on diversity (dFID), showcasing Stylus’s consistent advantage even with longer prompts.

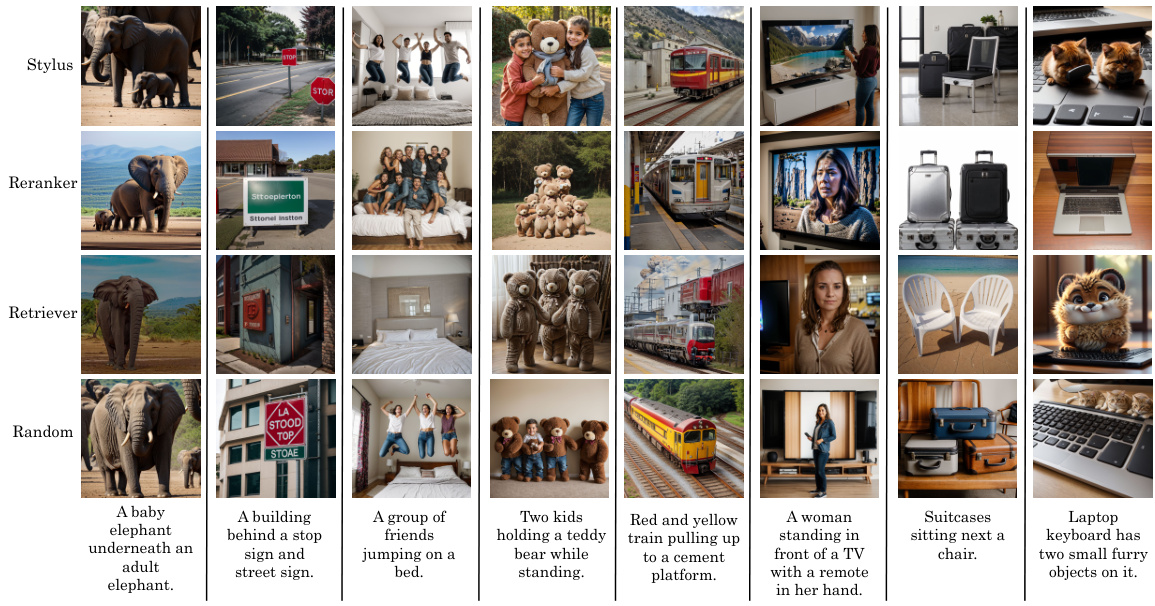

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of image generation results from different adapter retrieval methods: Stylus, Reranker, Retriever, and Random. Each method was given the same set of prompts to generate images. The figure demonstrates that Stylus produces images that are more faithful to the prompt’s description compared to other methods which either introduce irrelevant elements or fail to capture essential aspects of the prompt. This highlights Stylus’s superior ability to select and compose relevant adapters for improved image quality and alignment with the user’s intent.

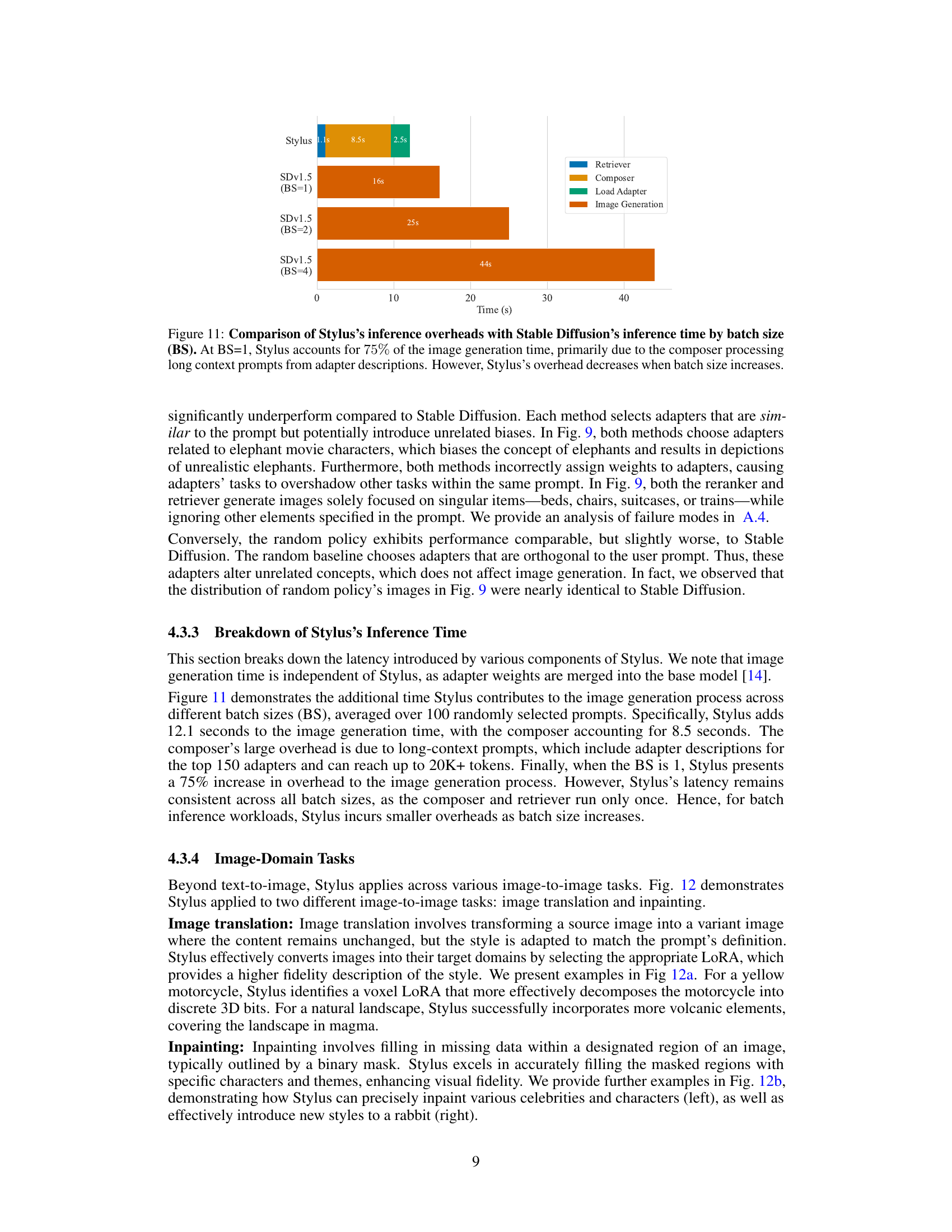

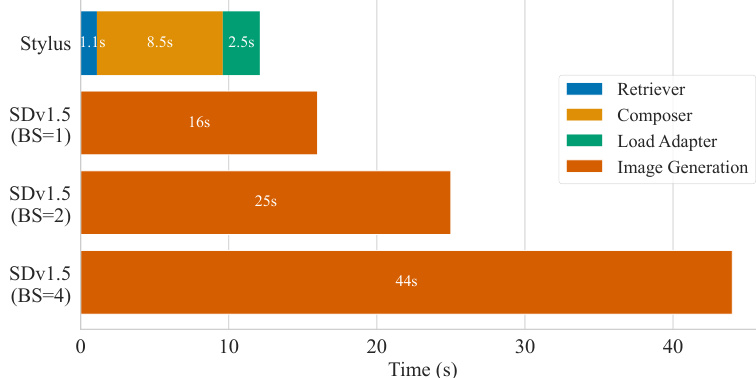

This figure compares the inference time of Stylus and Stable Diffusion (SDv1.5) for different batch sizes (BS). When the batch size is 1, Stylus takes significantly longer than SDv1.5 because the composer needs to process long prompts to make use of the adapter information. However, as the batch size increases, the overhead of Stylus relative to SDv1.5 decreases, demonstrating that Stylus’s additional processing time is largely due to its text-based adapter selection which is performed once per batch.

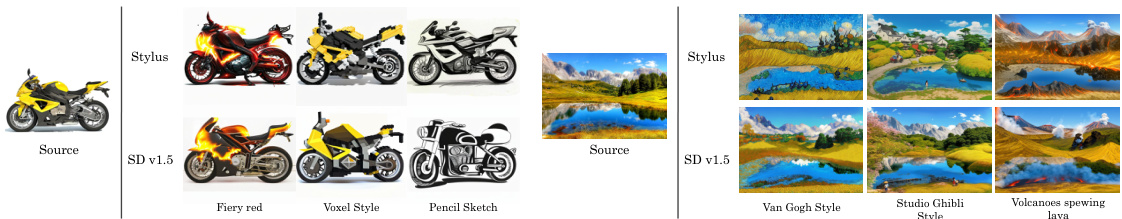

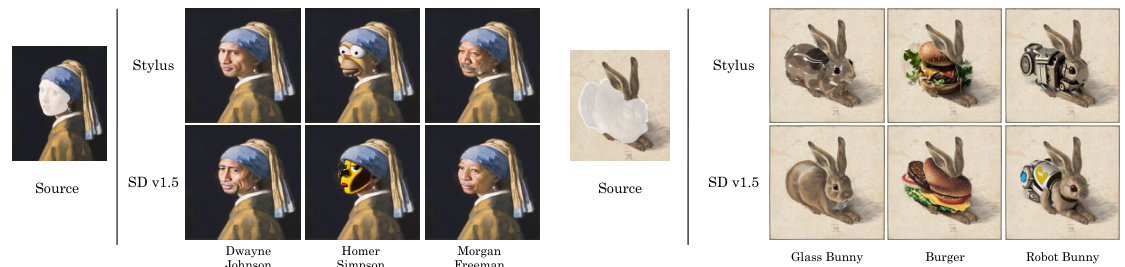

This figure shows the results of applying Stylus to two different image-to-image tasks: image translation and inpainting. The image translation examples demonstrate Stylus’s ability to transform images into different styles (fiery red, voxel style, pencil sketch) while preserving the original content. The inpainting examples illustrate Stylus’s capacity to seamlessly fill in missing regions of images, such as replacing a face with a different person’s face or adding elements like a bunny to an image.

This figure shows two examples of image-to-image tasks performed using the Stylus model and compares the results to those obtained using the Stable Diffusion v1.5 model. The left-hand side demonstrates image translation, where a source image (e.g., a motorcycle) is transformed into a variant image with a different style (e.g., a voxel style or pencil sketch) specified in the prompt. The right-hand side shows image inpainting, where Stylus fills in a missing portion of an image (e.g., a masked region of a rabbit) with new characters or concepts (e.g., a glass bunny, a burger, or a robot bunny). In both cases, Stylus produces images that more accurately reflect the prompt’s specifications compared to the Stable Diffusion v1.5 model.

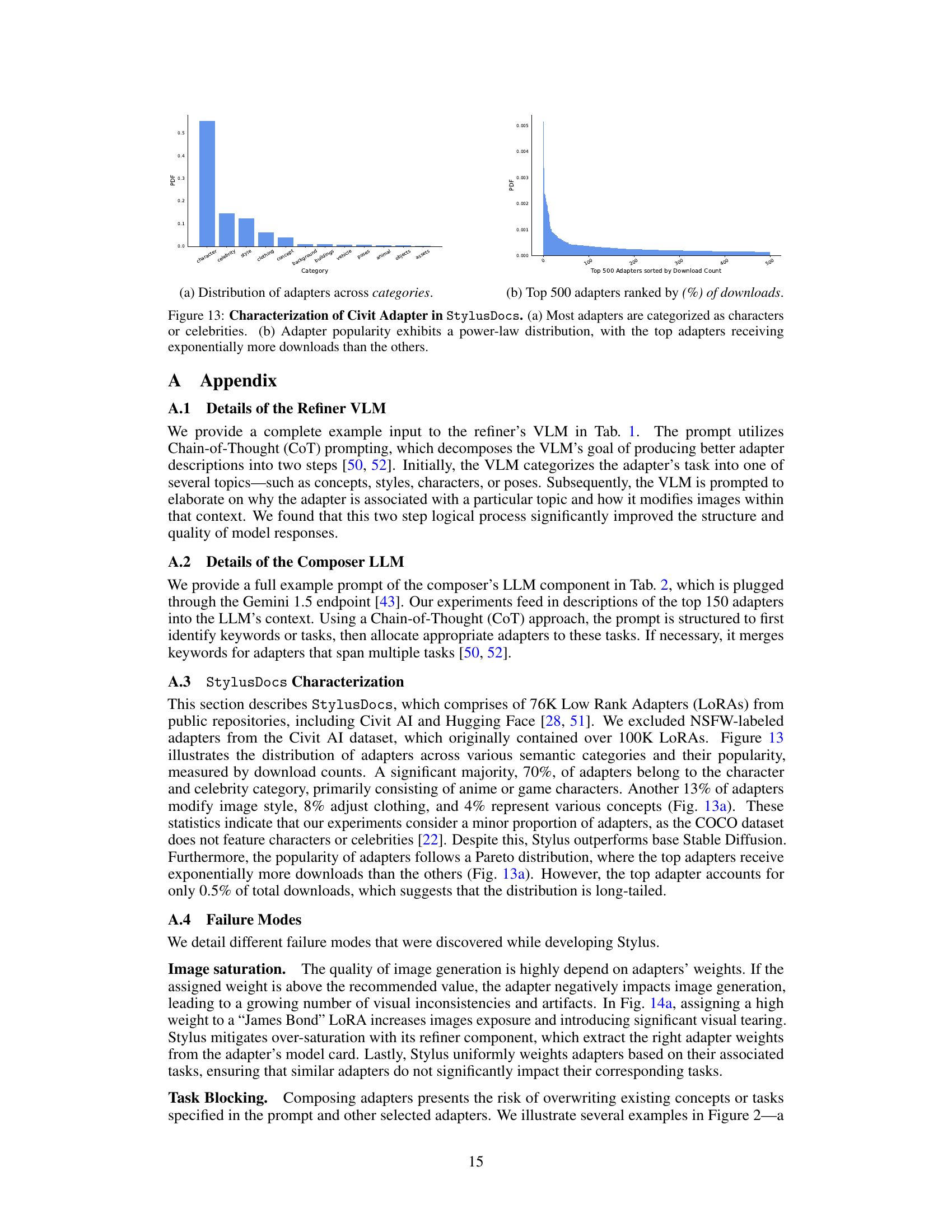

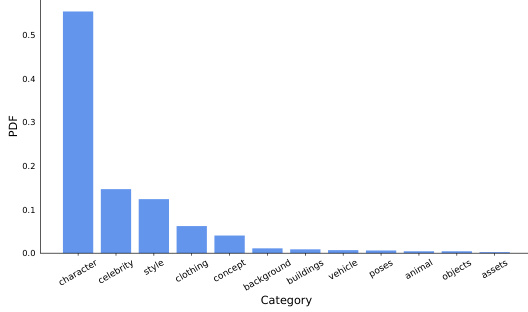

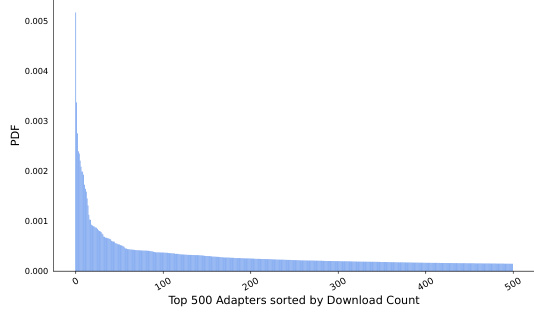

This figure presents a characterization of the adapters found within the StylusDocs dataset. Panel (a) shows a bar chart illustrating the distribution of adapters across various categories, revealing a significant dominance of ‘character’ and ‘celebrity’ categories. Panel (b) displays a histogram showing the distribution of the top 500 adapters based on their download counts. This demonstrates a power-law distribution, where a small number of adapters account for a disproportionately large share of the total downloads, with the most popular adapters having exponentially higher download counts than less popular ones.

This figure shows the distribution of adapters in StylusDocs dataset across different categories and their popularity based on download counts. Subfigure (a) is a bar chart showing the proportion of adapters falling into various categories like character, celebrity, style, etc. It highlights that a significant portion of adapters are related to characters and celebrities. Subfigure (b) is a histogram illustrating the distribution of download counts for the top 500 adapters, demonstrating a power-law distribution where a small number of adapters account for a large portion of the downloads.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of images generated by Stylus and Stable Diffusion base models for both realistic and cartoon styles. Three example prompts are used, demonstrating that Stylus generates images with higher fidelity and more accurately reflects the keywords given in the prompts compared to the base model.

This figure shows examples of different failure modes that can occur when using adapters in image generation. Specifically, it illustrates the problems of image saturation (over-exposure due to high adapter weights), task blocking (where one adapter’s effect overrides another), task diversity (lack of variation in generated images for a single task), low-quality adapters (producing poor image quality), and retrieval errors (incorrect adapter selection). Each subfigure (a-e) provides a visual demonstration of one of these failure modes.

This figure showcases a qualitative comparison of images generated by Stylus and Stable Diffusion (SD v1.5) using two different checkpoints: Realistic-Vision-v6 and Counterfeit-v3. The images demonstrate that Stylus produces higher-quality, more detailed images that accurately reflect the keywords in the given prompt, while the Stable Diffusion model sometimes generates images that don’t fully match the prompt’s intent. The example ‘A graffiti of a corgi on the wall’ illustrates this difference; Stylus shows a spray-painted corgi consistent with graffiti art, while the Stable Diffusion model depicts a realistic dog.

This figure demonstrates the improved diversity achieved by Stylus compared to the Stable Diffusion checkpoints. The same prompt is used for both Stylus and the Stable Diffusion model. Stylus generates a wider variety of images with different compositions, styles, and details, showcasing its ability to produce more comprehensive and diverse outputs. This diversity stems from Stylus’s unique masking scheme and the temperature parameter used in its composer LLM. The masking scheme randomly selects a subset of relevant adapters for each task, leading to different combinations of adapters for each image generation. The temperature parameter in the composer LLM controls the randomness of the adapter selection process, further enhancing the diversity of the generated images.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of image generation results between Stylus and the Stable Diffusion model v1.5, using both realistic and cartoon-style checkpoints. The images illustrate Stylus’s ability to generate higher-fidelity images that more accurately reflect the keywords in the prompt, compared to the Stable Diffusion v1.5 baseline. The example highlights Stylus’s superior ability to incorporate stylistic elements and details specified in the prompt, resulting in more accurate and contextually appropriate outputs.

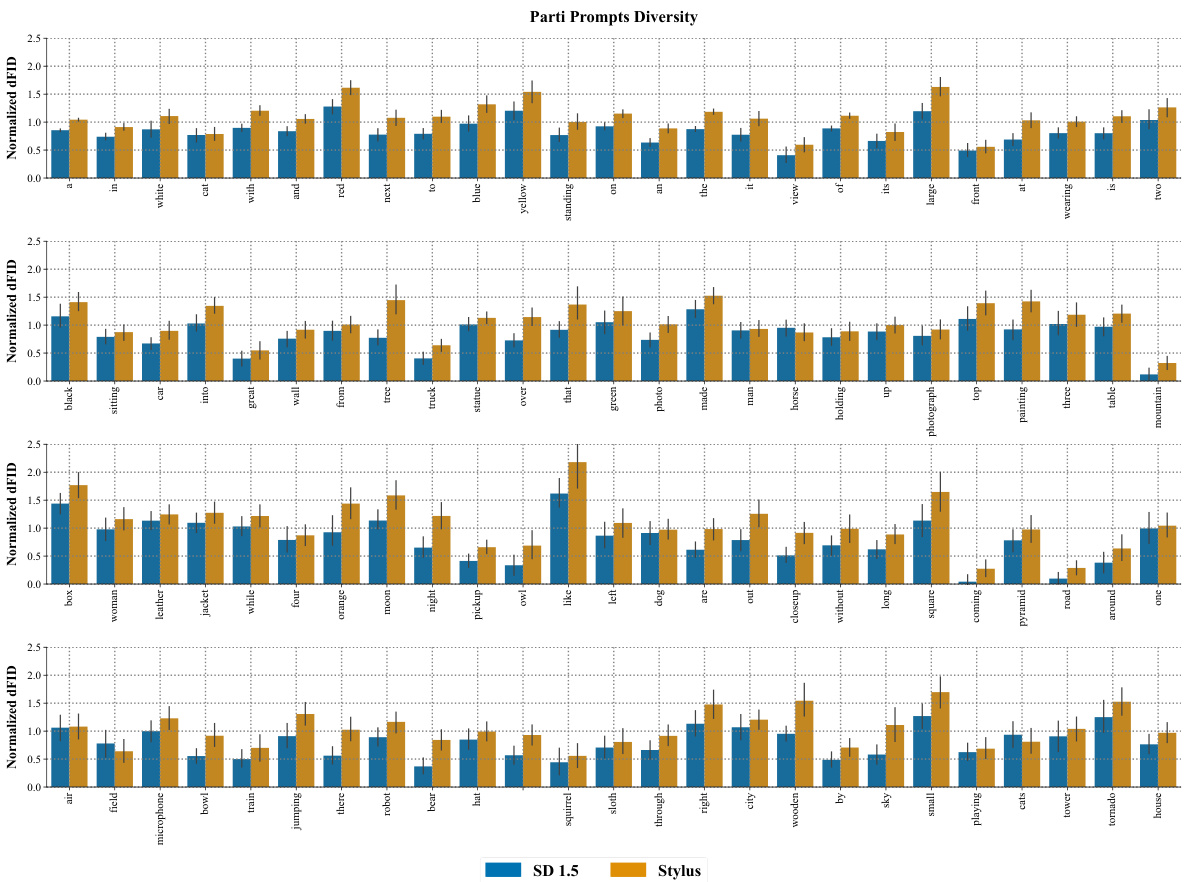

This figure presents a bar chart comparing the diversity (measured by dFID) of images generated by Stylus and Stable Diffusion for the top 100 keywords from the PartiPrompts dataset. The chart is organized into four sub-charts, each showing a subset of the keywords. For each keyword, two bars are displayed: one representing the dFID score for Stable Diffusion, and the other for Stylus. Error bars are included to show variability. The results demonstrate that Stylus consistently achieves higher diversity scores than Stable Diffusion, particularly for keywords representing concepts and attributes rather than simple objects.

Full paper#