↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) demonstrate a remarkable ability to solve tasks not explicitly seen during training. This phenomenon, often attributed to in-context learning and skill composition, is poorly understood. Existing research mostly focuses on continuous tasks, leaving a gap in understanding how LLMs generalize on discrete problems like modular arithmetic. This paper aims to address this gap by investigating the emergence of in-context learning and skill composition in a series of modular arithmetic tasks.

The study uses a GPT-style transformer to explore the effects of increasing training tasks and model depth on generalization. The key finding is a phase transition, moving from memorization to generalization as training progresses. The research also identifies different algorithmic approaches used by the models, highlighting a shift from simpler methods to more advanced ones. Finally, the researchers offer interpretability insights, revealing the structured representations learned by the models and showing how these contribute to successful task completion.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers exploring in-context learning and skill composition in large language models. It introduces a novel algorithmic dataset for studying these phenomena, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms behind model generalization. The findings offer new avenues for interpretability research and understanding the emergence of complex capabilities in LLMs, informing future model design and improving their performance on complex tasks.

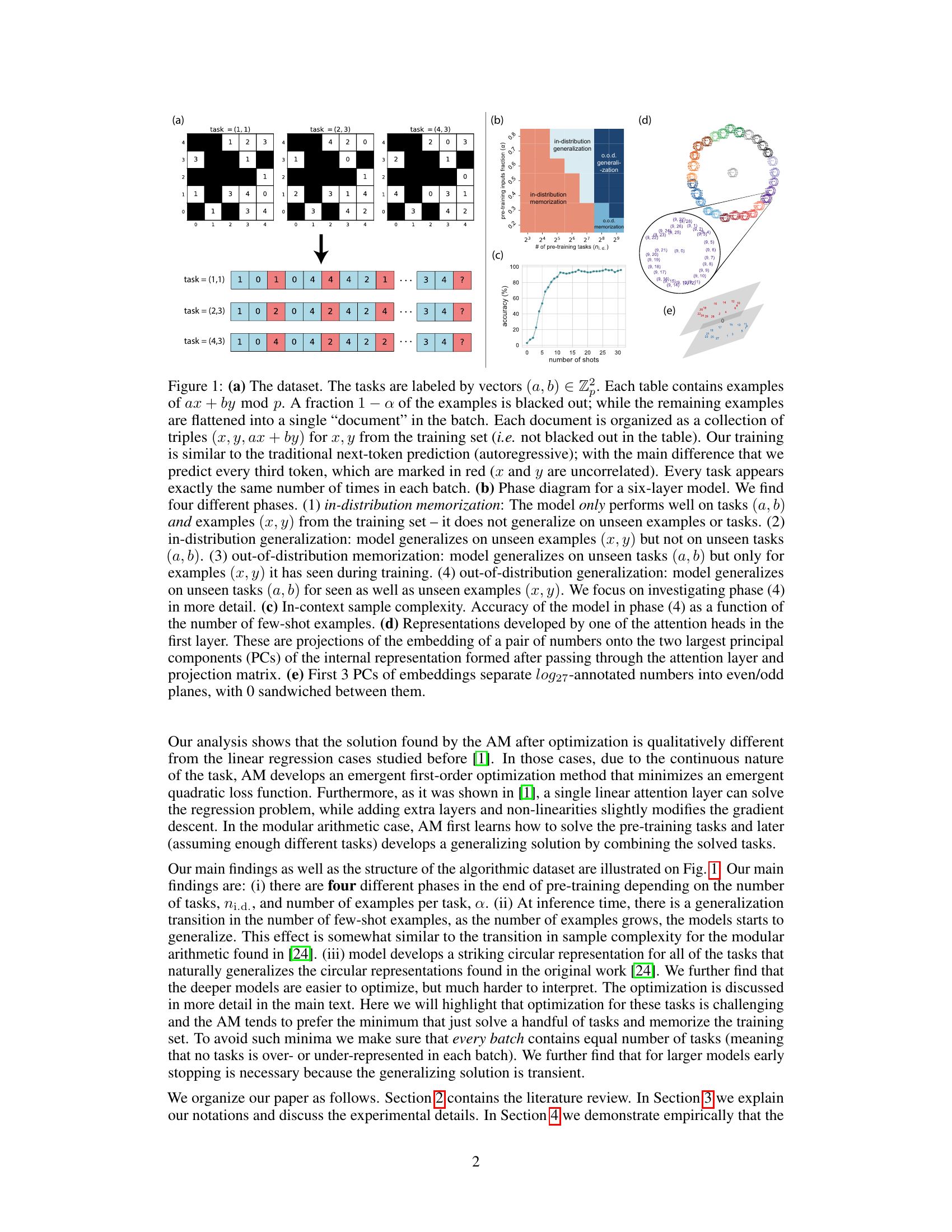

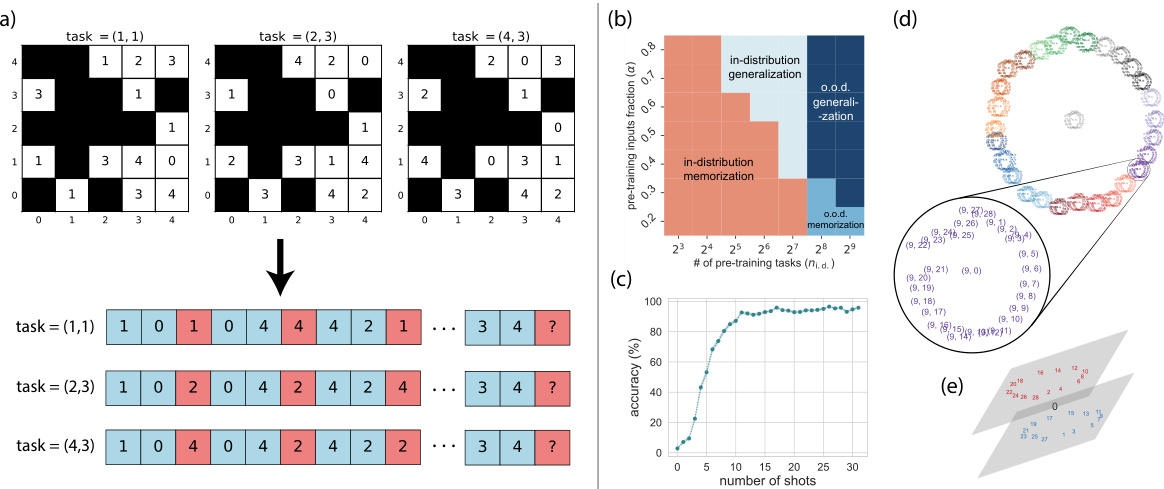

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the dataset used for training and testing the model. The modular arithmetic tasks are represented as tables (a), where a fraction of examples is hidden. The model is trained to predict the output given input x and y. The phase diagram (b) illustrates the four different phases of model generalization, ranging from in-distribution memorization to out-of-distribution generalization. The in-context sample complexity (c) shows the accuracy as a function of the number of few-shot examples. The attention head representation (d) and principal component analysis (e) provide insights into the model’s internal representations.

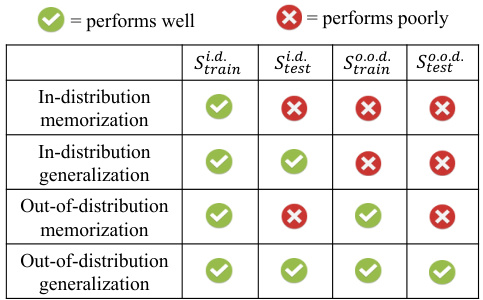

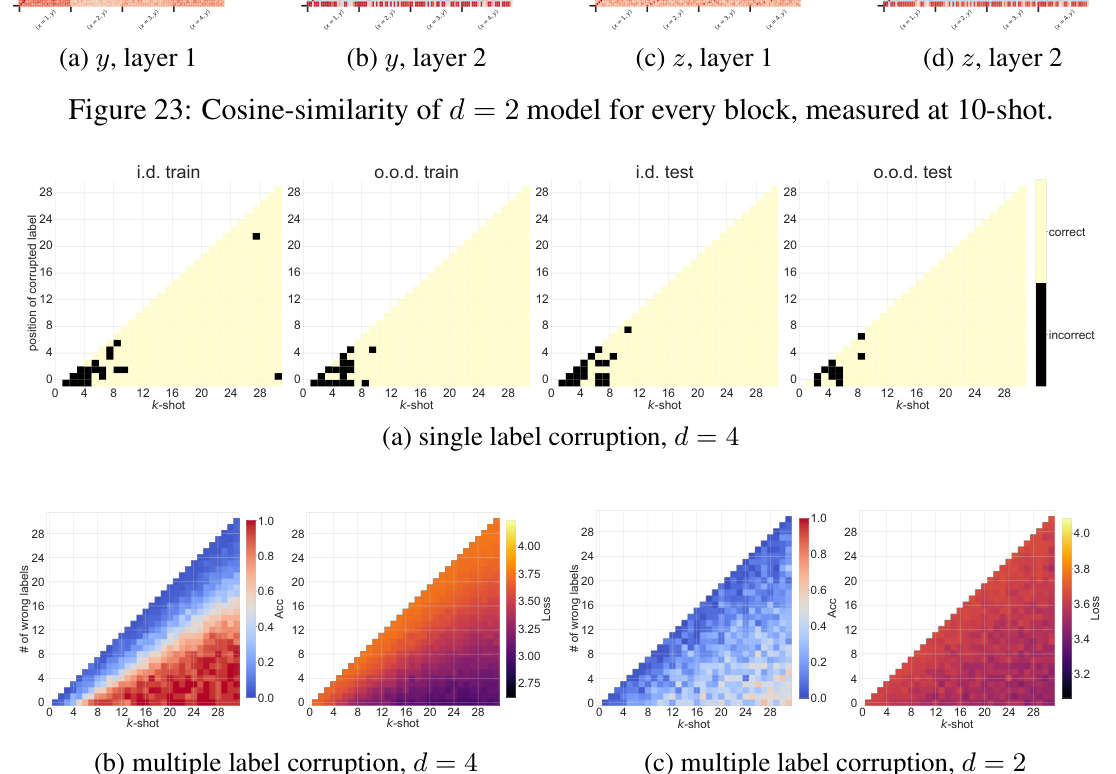

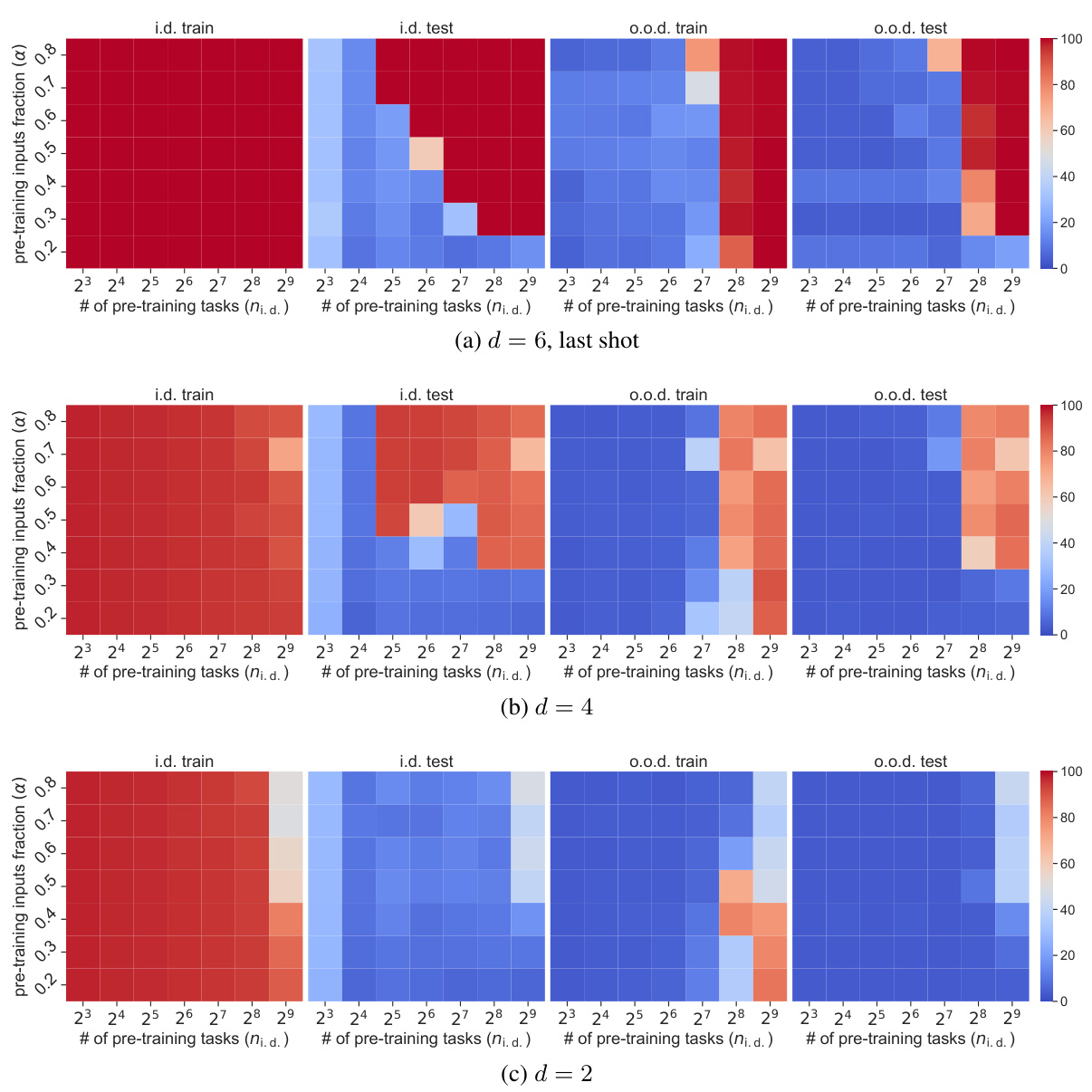

This table shows the four distinct phases of generalization observed in the model’s performance. It distinguishes between in-distribution (i.d.) and out-of-distribution (o.o.d.) generalization, based on whether the model has seen the task vector during pre-training. Each phase is characterized by its performance on four different sequence sets: in-distribution training, in-distribution testing, out-of-distribution training, and out-of-distribution testing. The symbols (☑, ✕) indicate whether the model performs well or poorly in each phase.

In-depth insights#

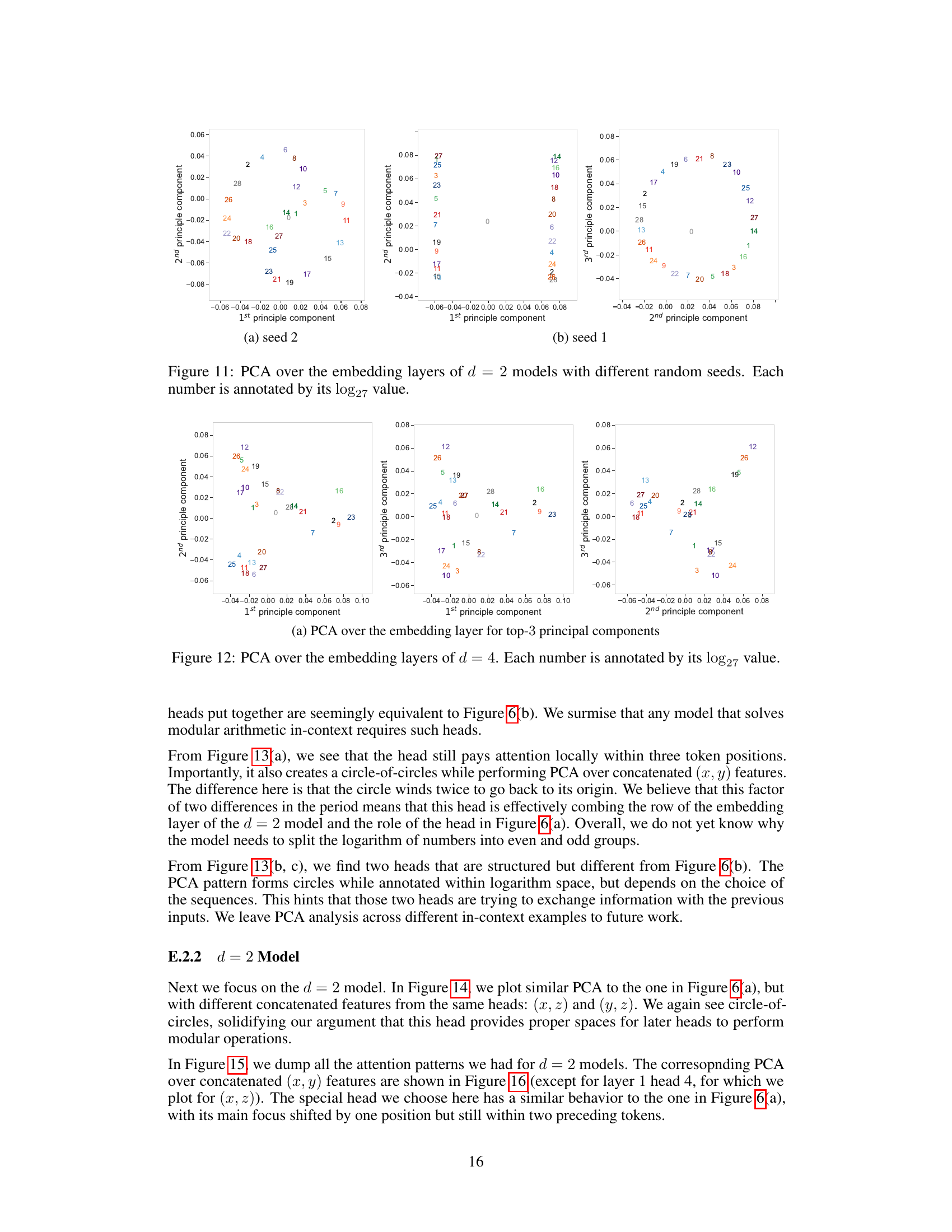

Modular Arithmetic#

The concept of modular arithmetic, focusing on operations within a finite set of integers (modulo p), provides a unique lens for investigating in-context learning in large language models. The use of modular arithmetic tasks offers a controlled environment, allowing researchers to isolate and analyze specific emergent skills in LLMs, such as the ability to compose simple skills into complex ones. By carefully designing modular arithmetic problems, the research can effectively probe whether LLMs learn algorithmic solutions or merely memorize input-output pairs. The results provide valuable insight into how LLMs generalize to unseen tasks, highlighting the importance of factors like model depth and the number of training tasks in determining whether out-of-distribution generalization emerges. The analysis of the learned algorithms reveals whether models utilize efficient, generalizable strategies, or rely on simpler, less scalable methods.

In-Context Learning#

In-context learning (ICL) is a remarkable ability of large language models (LLMs) to solve tasks not explicitly present in their training data by using a few examples provided in the input prompt. This paper investigates ICL within the context of modular arithmetic, demonstrating that the emergence of out-of-distribution generalization is directly linked to the number of pre-training tasks. The transition from memorization to generalization is explored, revealing a crucial role of model depth and the composition of simple skills into complex ones. The study finds that deeper models exhibit a transient phase of ICL and require early stopping, whereas shallower models showcase a direct transition to generalization. Interpretability analyses reveal that models leverage structured representations in attention heads and MLPs, employing algorithms like ratio matching and modular regression. These findings offer valuable insights into the mechanisms behind ICL and highlight the trade-off between memorization and generalization during the learning process, shedding light on the emergent capabilities of LLMs.

Grokking Emergence#

The concept of “Grokking Emergence” in the context of large language models (LLMs) refers to the sudden and unexpected improvement in model performance on a specific task after a certain amount of training. This phenomenon is often associated with the emergence of structured representations within the model’s internal architecture, which are believed to facilitate the development of sophisticated algorithms. This contrasts with traditional learning, where performance usually shows a gradual improvement. The emergence of these representations is often abrupt and difficult to predict. Investigating this phenomenon is critical to understanding the capabilities of LLMs and improving their ability to solve complex tasks. It also offers a valuable insight into the nature of intelligence itself, as the process resembles aspects of human learning and problem solving. Further research is needed to pinpoint the specific mechanisms underlying grokking and to find reliable ways to induce it more consistently in the training process.

Algorithmic Shifts#

The concept of “Algorithmic Shifts” in large language models (LLMs) is intriguing. It suggests that as models are trained on more data, and grow in size and complexity, their internal workings fundamentally change. This isn’t merely a quantitative improvement, but a qualitative shift in the way the model solves problems. Early in training, LLMs might rely on memorization or simple heuristics, focusing on patterns directly observed during training. As training progresses, they transition to more sophisticated, abstract algorithms, which generalize better to unseen data. This shift represents a transition from rote learning to genuine understanding, possibly an emergent property of complex systems. Deep models might exhibit transient phases, where a generalized solution emerges, but then fades as the model continues to train, perhaps highlighting an instability or the necessity of early stopping to capture beneficial emergent behavior. Identifying and characterizing these algorithmic shifts is crucial for advancing our comprehension of LLMs. This would facilitate better model design, improved training strategies, and more nuanced analyses of model capabilities and limitations. Ultimately, the nature of these shifts and their relationship to model performance and generalization are rich areas requiring further investigation.

Interpretability Study#

An interpretability study of a model trained on modular arithmetic tasks would ideally involve examining the internal representations to understand how the model learns and generalizes. Analyzing attention weights could reveal if the model focuses on specific input patterns or relationships between inputs and outputs. Investigating the activation patterns of neurons in the model’s layers may reveal the emergence of structured representations indicative of algorithmic understanding. Probing the model’s internal computations could reveal whether the model relies on simple pattern matching or more complex methods, such as modular arithmetic operations. A comparison between models with different depths might provide further insight into the emergence of these structured representations and any algorithmic shifts that occur with increased depth and training data. Visualizations, such as heatmaps of attention weights and activation patterns, can be crucial tools to aid in understanding how the model operates internally. By combining various methods and analyses, a comprehensive interpretability study can help illuminate the inner workings of the model and its ability to generalize beyond the training data.

More visual insights#

More on figures

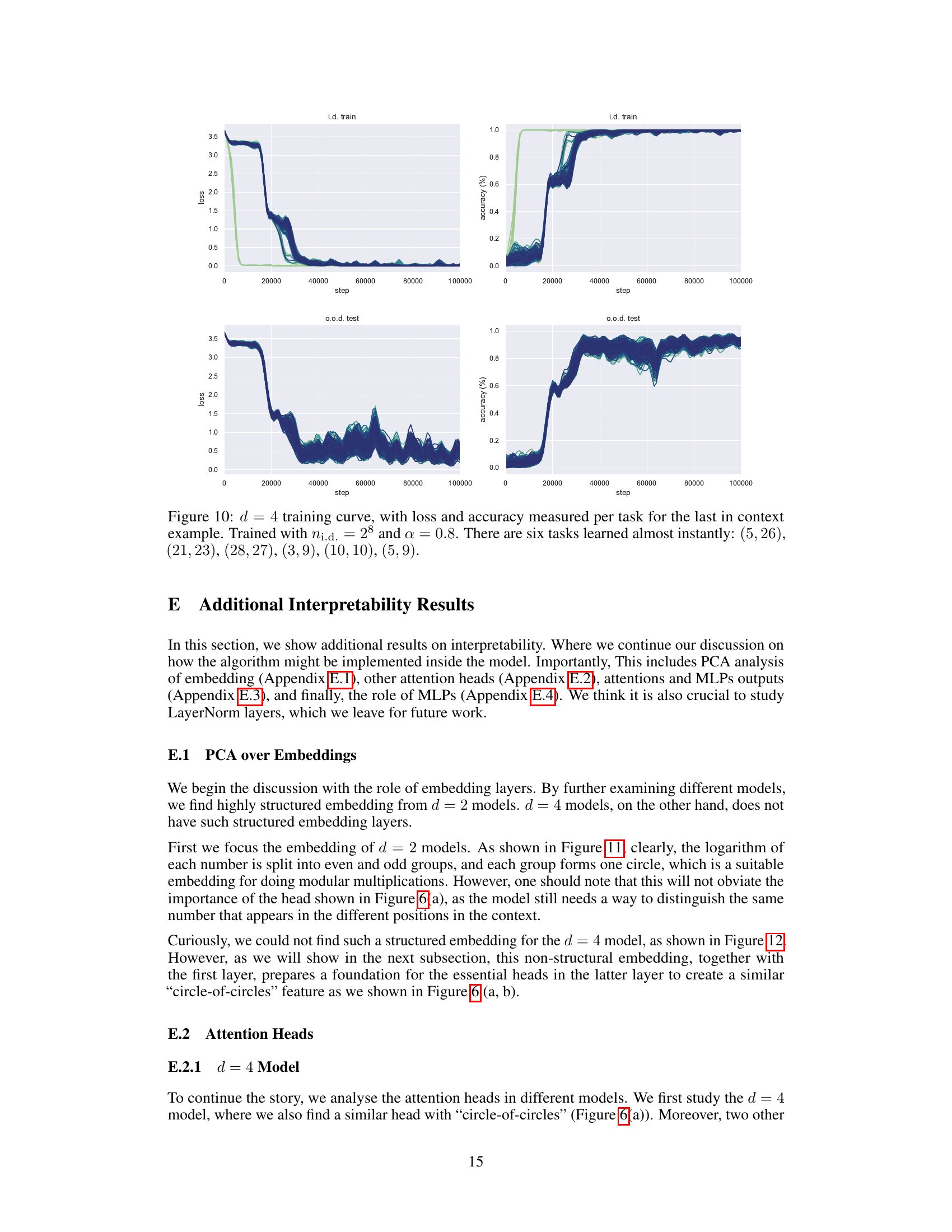

This figure illustrates the methodology for selecting pre-training tasks and designing sequences. Panel (a) shows a schematic of the rectangular rule used for task selection. New tasks are chosen by incrementally adjusting one parameter (a or b) while keeping the other constant. This ensures a systematic exploration of the task space and facilitates the model’s learning process. Panel (b) demonstrates the structure of the pre-training sequences. Each batch contains an equal number of sequences for each task, and the sequences are structured to ensure that the model learns task vectors in a coherent, step-wise fashion. The consistent sequence structure throughout all batches contributes to effective learning, reducing confusion and noise.

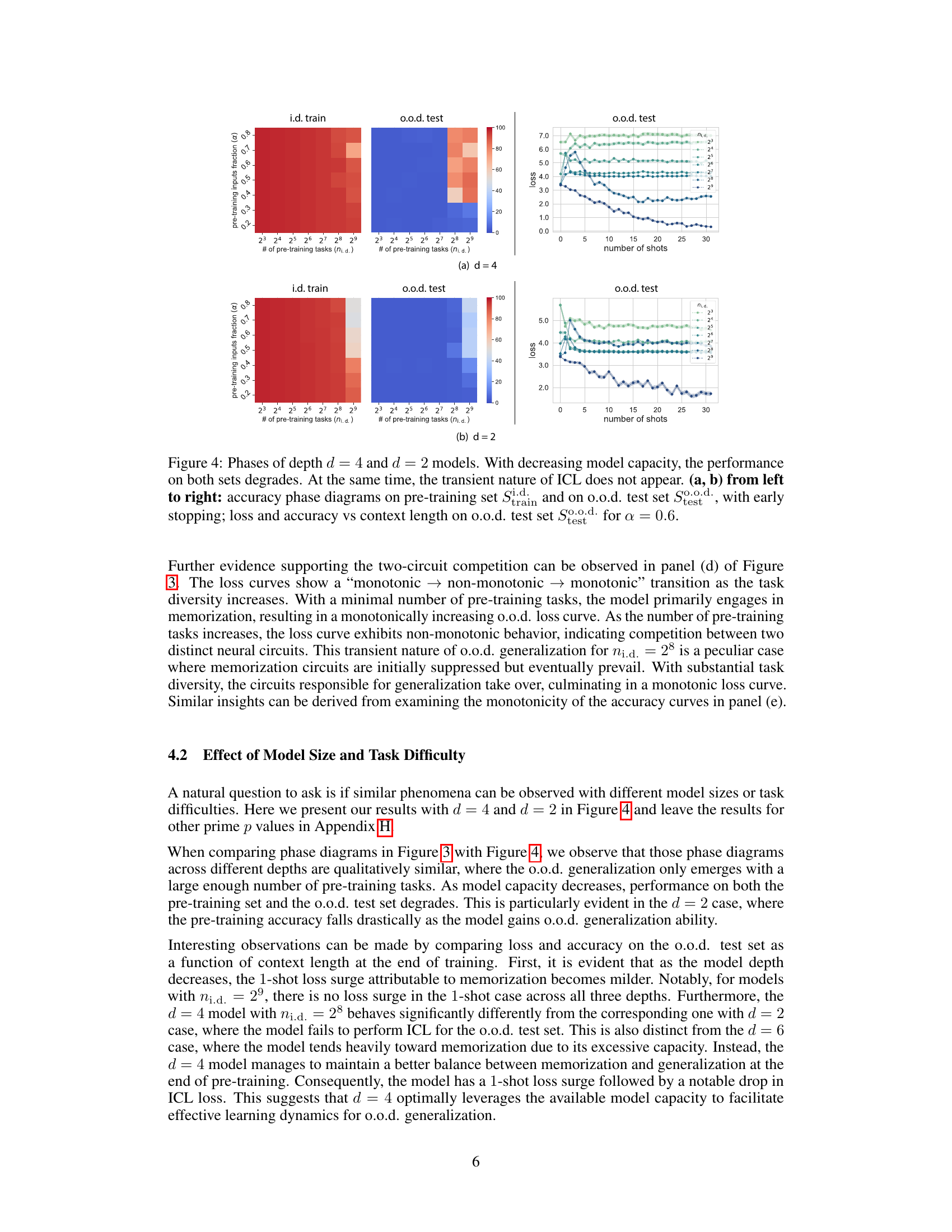

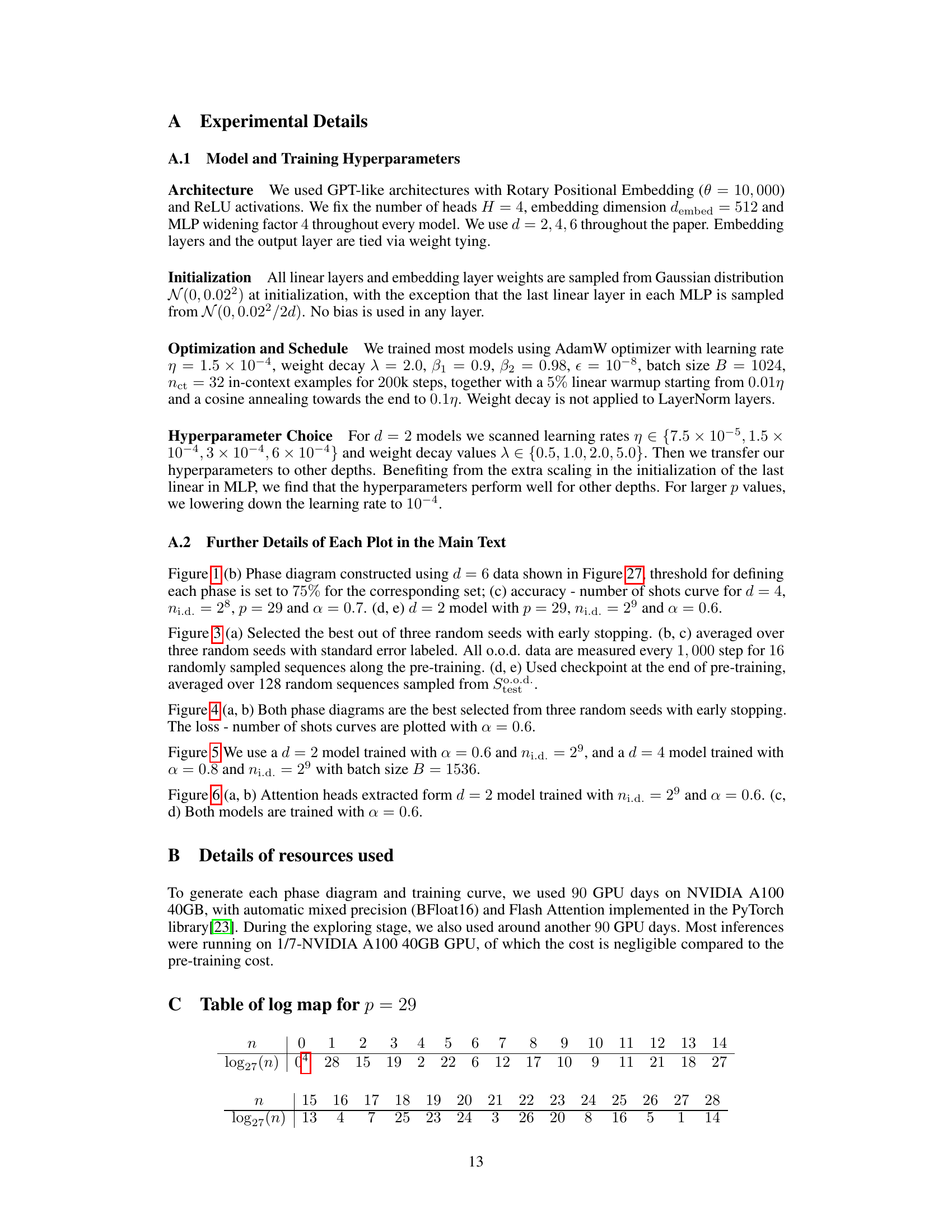

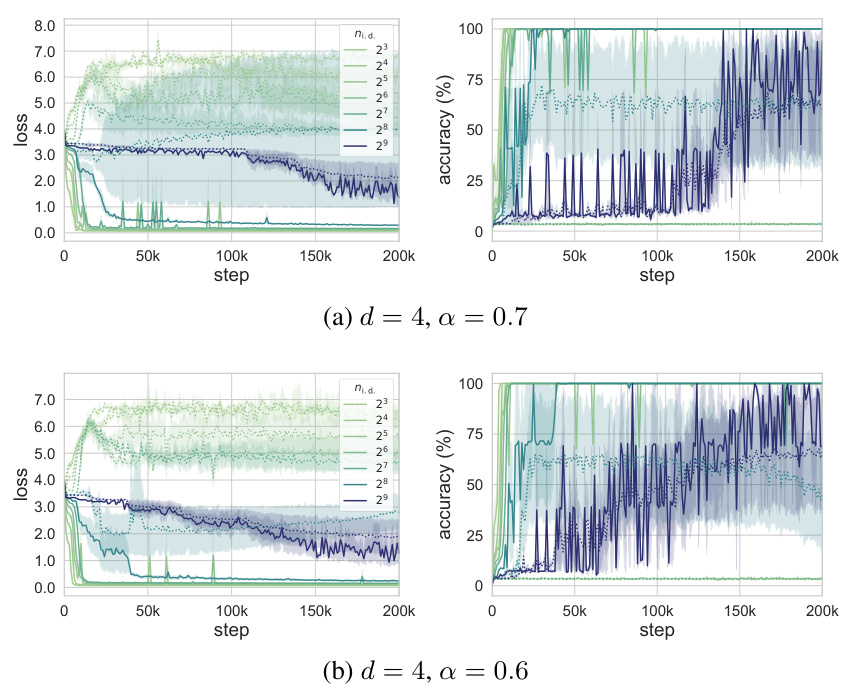

This figure shows a phase diagram for a 6-layer transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. It illustrates the transition between different generalization phases as the number of pre-training tasks and the number of in-context examples vary. The four phases are: in-distribution memorization, in-distribution generalization, out-of-distribution memorization, and out-of-distribution generalization. Notably, the figure shows that out-of-distribution generalization is a transient phenomenon for deeper models, requiring early stopping to achieve optimal performance. The plots also demonstrate the relationship between loss and accuracy, as a function of the number of training steps and the number of in-context shots.

This figure shows the phase diagram for a six-layer transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. It illustrates four distinct phases of generalization behavior as a function of the number of training tasks (ni.d.) and the fraction of training data used (a) at inference time. These phases are: in-distribution memorization, in-distribution generalization, out-of-distribution memorization, and out-of-distribution generalization. The figure also presents training and testing accuracy curves, showing how the out-of-distribution generalization ability of the model improves initially and then degrades with more training steps for a specific number of training tasks (ni.d. = 28). Finally, it shows loss and accuracy curves as a function of the context length (number of shots) used at inference time, further illustrating the trade-off between memorization and generalization in the model’s behavior.

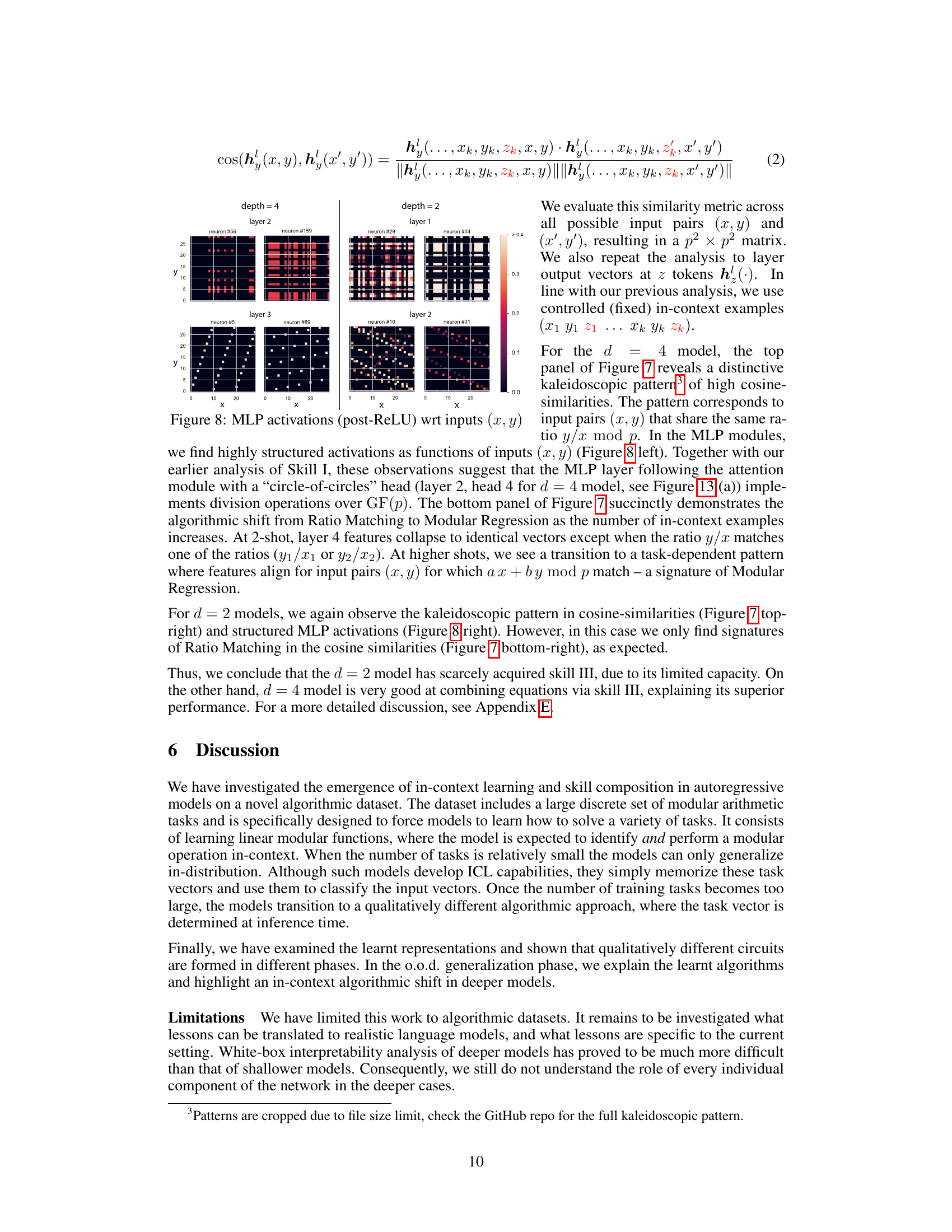

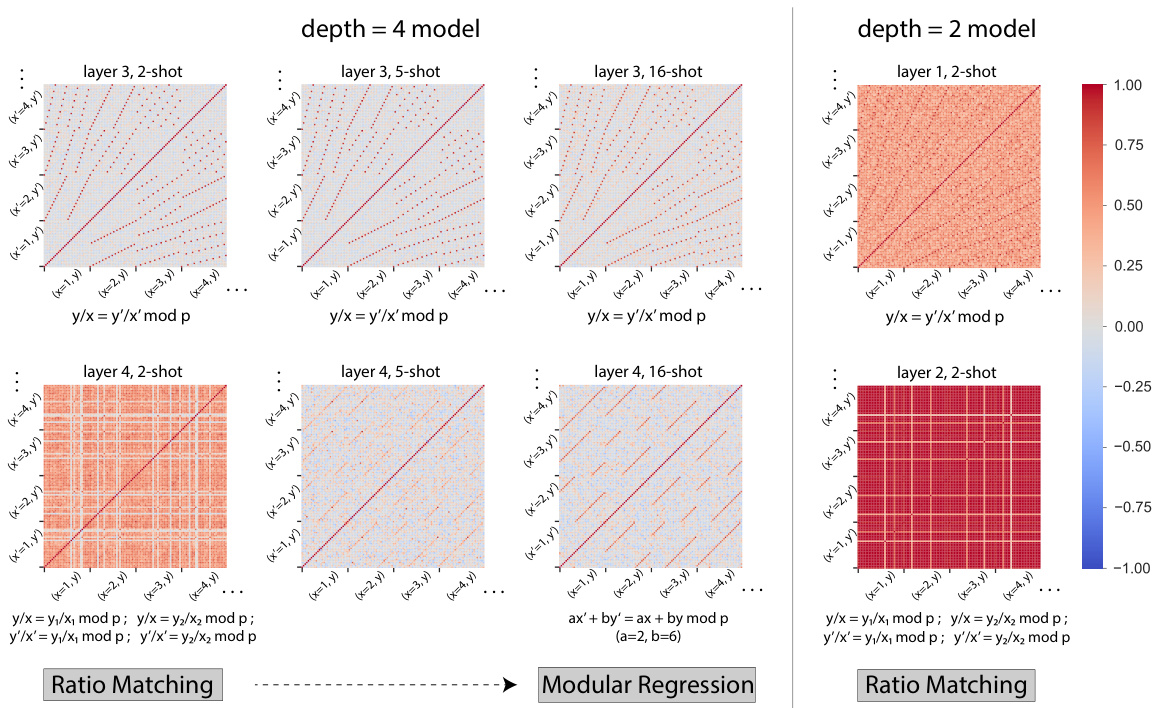

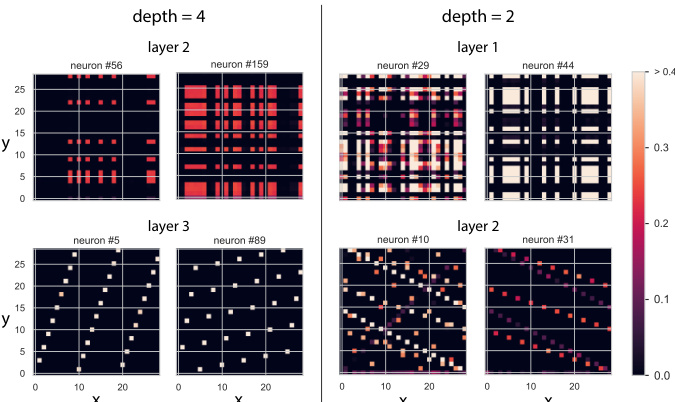

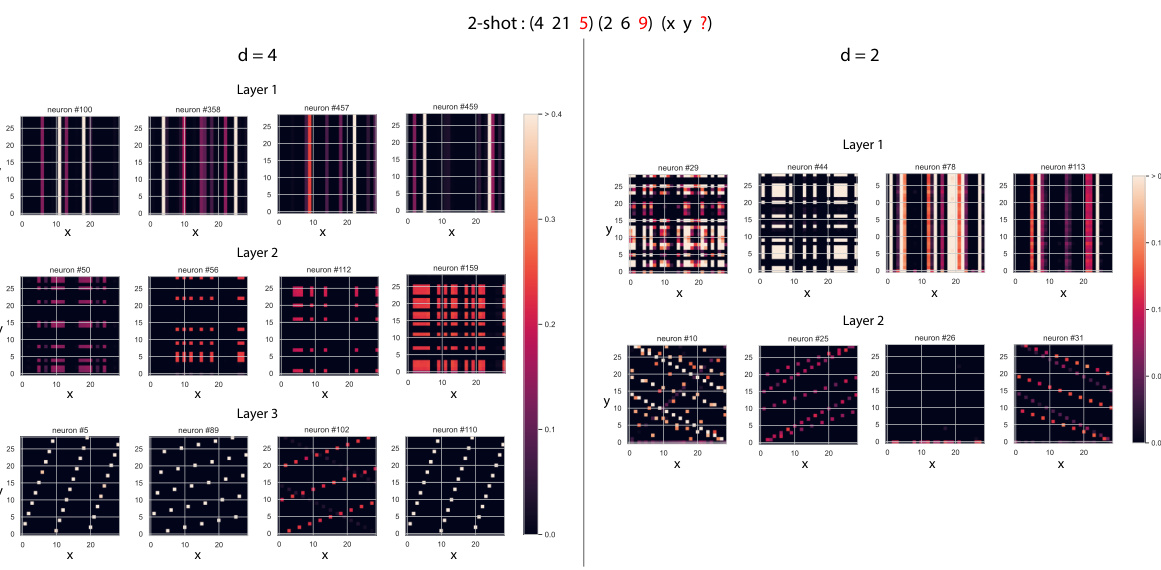

This figure compares the performance of depth 4 and 2 models on a modular arithmetic task with varying numbers of in-context examples (k-shot). Row 1 shows the models’ predictions, Row 2 shows the predictions based on the Modular Regression algorithm, and Row 3 highlights the differences. Red points indicate where the model outperforms Ratio Matching, while blue points show where Ratio Matching outperforms the model. The depth 4 model shows better ability to combine in-context examples.

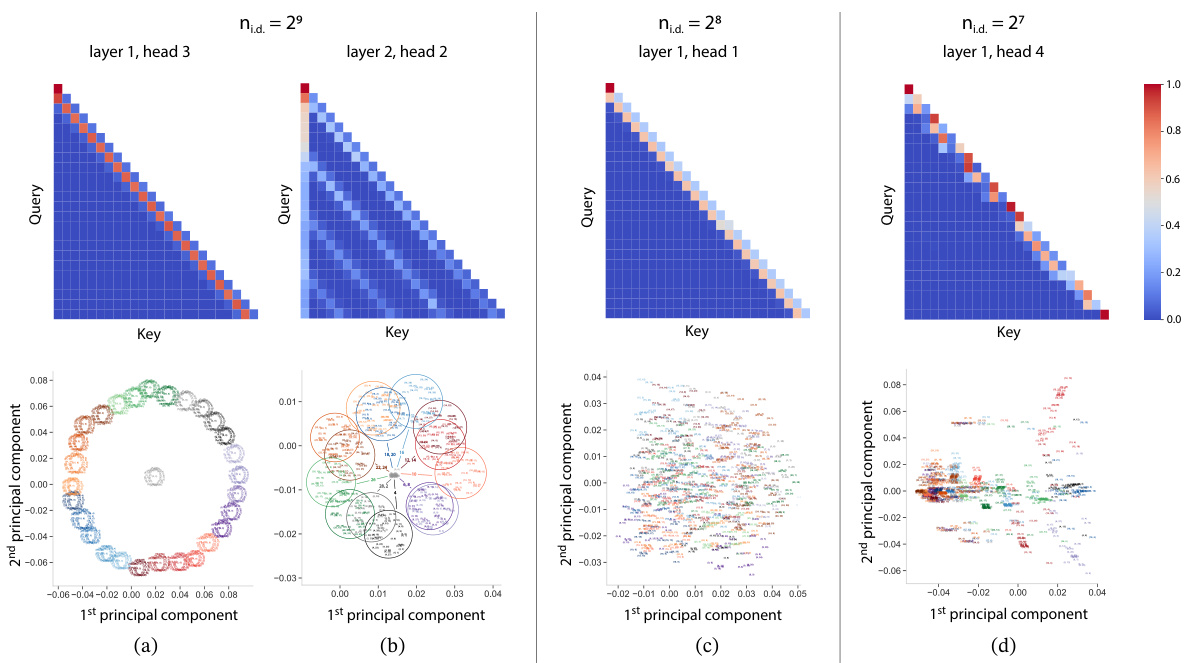

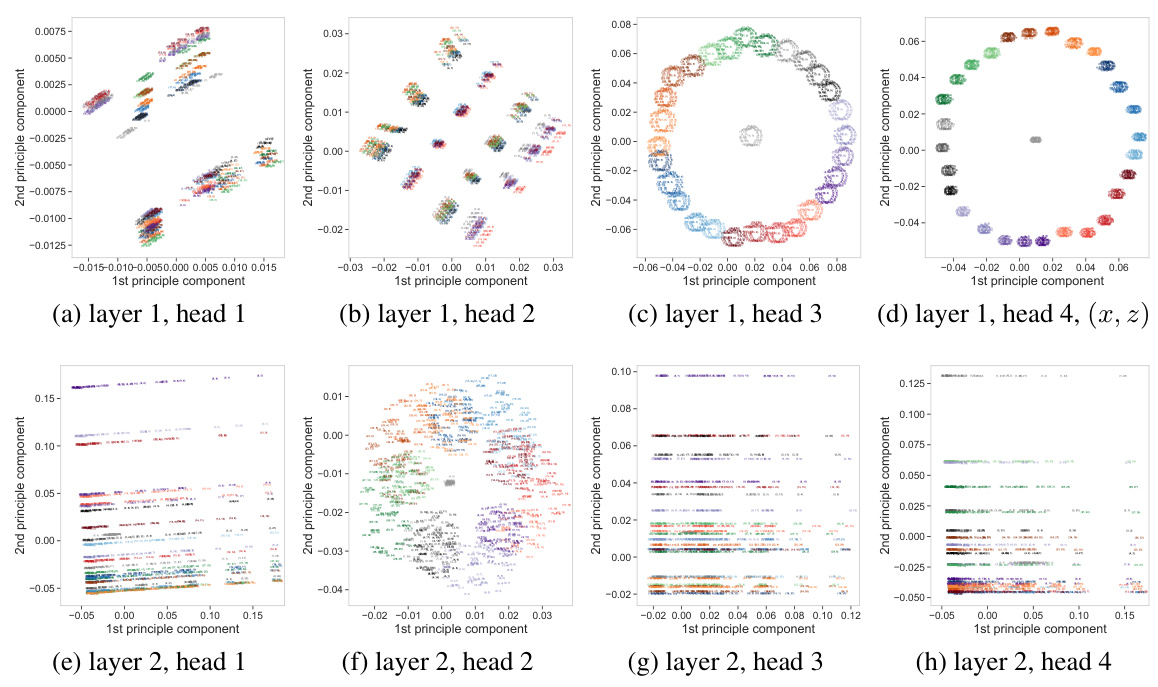

This figure demonstrates that models capable of out-of-distribution generalization exhibit more structured attention maps and principal component analysis (PCA) patterns compared to models lacking this ability. The structure is visualized through a ‘circle of circles’ pattern, where the outer circle’s position is determined by one of the input values. This pattern persists across various task vectors and shot choices. The less structured patterns in models without out-of-distribution generalization are also shown for comparison.

This figure compares the performance of two models (depth 4 and depth 2) on a modular arithmetic task with varying numbers of in-context examples (k-shot). It shows that the deeper model (d=4) is able to leverage in-context examples to perform Modular Regression effectively, while the shallower model (d=2) primarily uses Ratio Matching, which is less effective. The figure highlights the difference in algorithmic capabilities between the models due to their differences in capacity. Red and blue points indicate cases where the models deviate from the expected behavior of the respective algorithms.

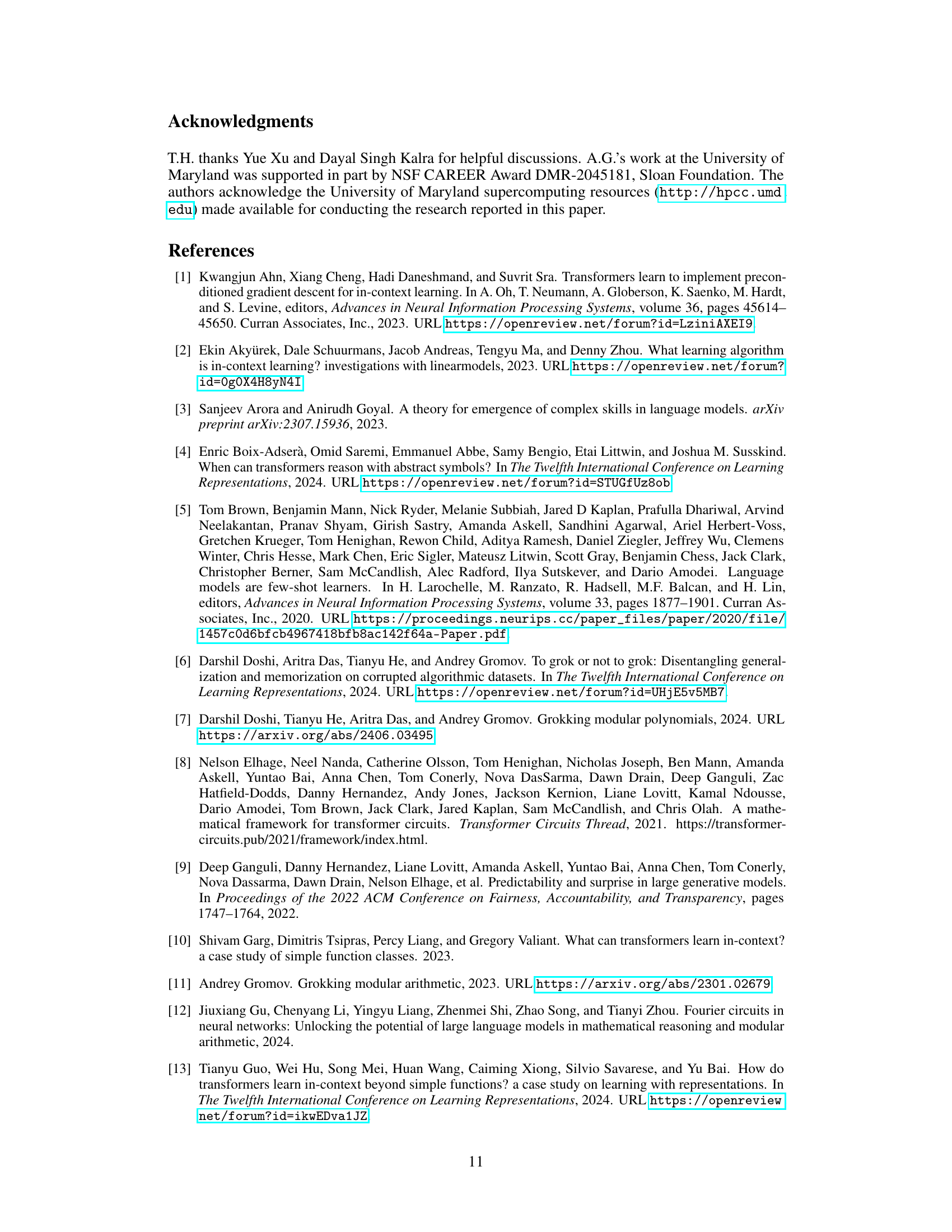

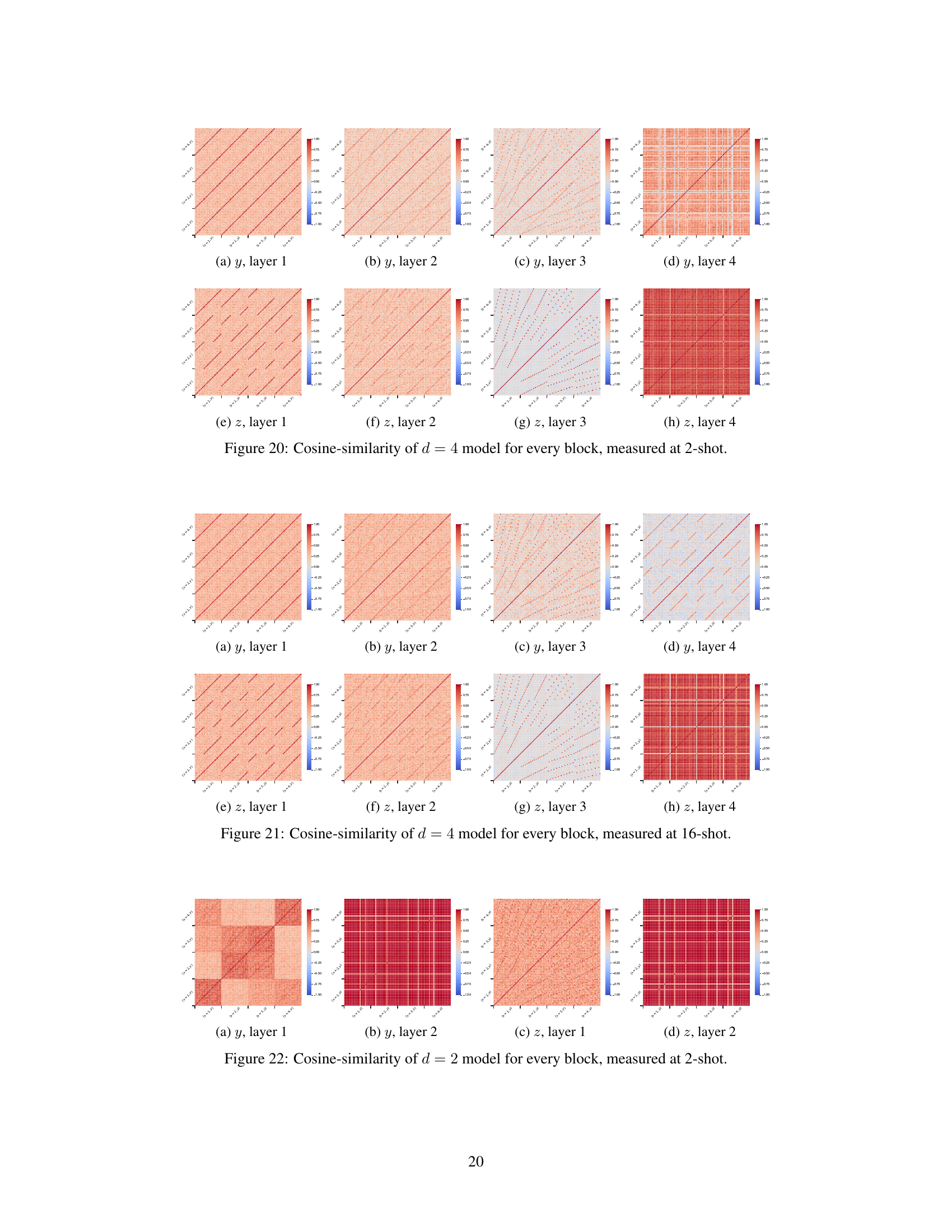

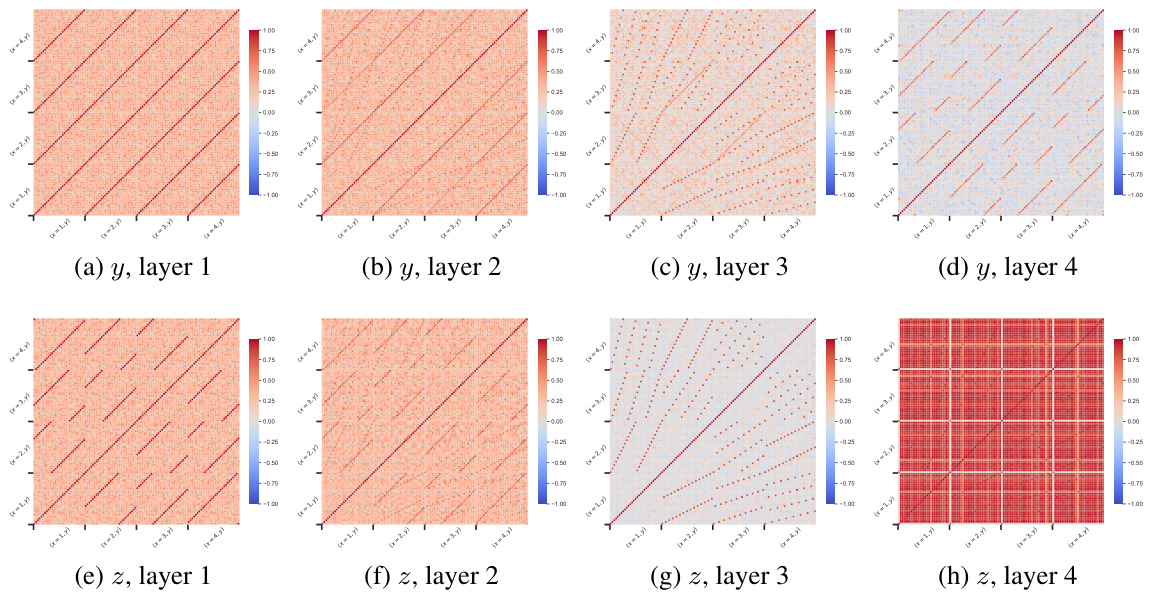

This figure shows the cosine similarity between layer outputs at different token positions for both d=4 and d=2 models. The d=4 model exhibits kaleidoscopic patterns in the third layer, indicating the generation of all possible y/x ratios for computation, and an algorithmic shift to Modular Regression in the final layer. The d=2 model shows a similar kaleidoscopic pattern in the first layer but only uses Ratio Matching in the second layer.

This figure shows a phase diagram for a 6-layer transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. The diagram illustrates four distinct phases of model behavior based on the number of pre-training tasks and the fraction of examples used at inference time. These phases are characterized by different levels of in-distribution and out-of-distribution generalization. The figure also includes plots demonstrating the training accuracy, out-of-distribution test accuracy, loss, and accuracy as functions of the number of training steps and the number of in-context examples, revealing a trade-off between memorization and generalization in certain scenarios. The diagram shows how the out-of-distribution generalization ability emerges and then disappears as training progresses for a specific number of tasks.

This figure shows the phase diagram for a 6-layer transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. The diagram illustrates the model’s performance across four phases: in-distribution memorization, in-distribution generalization, out-of-distribution memorization, and out-of-distribution generalization. It highlights a trade-off between in-distribution and out-of-distribution generalization as the number of training tasks increases, and a transient nature of out-of-distribution generalization ability in deeper models.

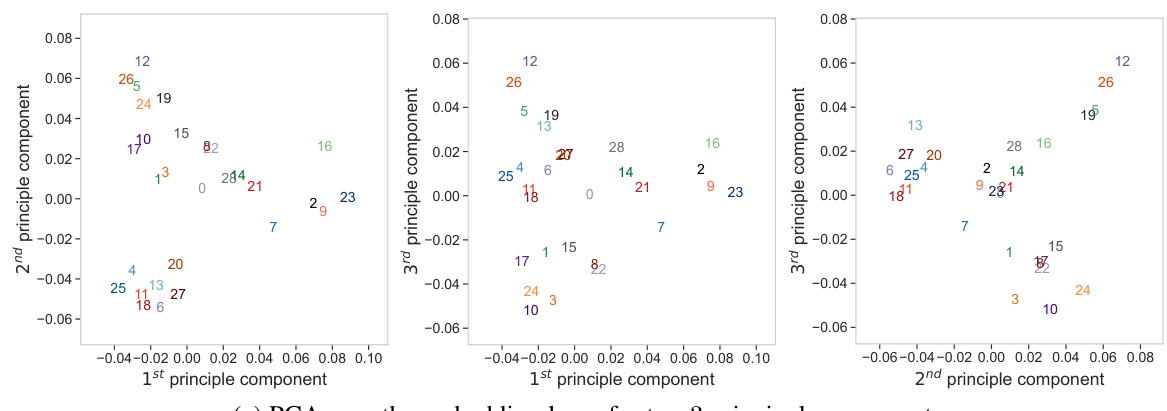

This figure presents several key aspects of the modular arithmetic task dataset and the model’s behavior. Panel (a) shows the data format, where examples of modular arithmetic functions are presented with some masked values. Panel (b) illustrates a phase diagram for a six-layer transformer model, identifying four phases of generalization and memorization on in-distribution (i.d) and out-of-distribution (o.o.d) tasks. Panel (c) explores in-context sample complexity, showing how accuracy changes with the number of shots. Panels (d) and (e) offer insights into the model’s internal representations, visualizing activation patterns in attention heads and the separation of even/odd numbers in the principal component analysis.

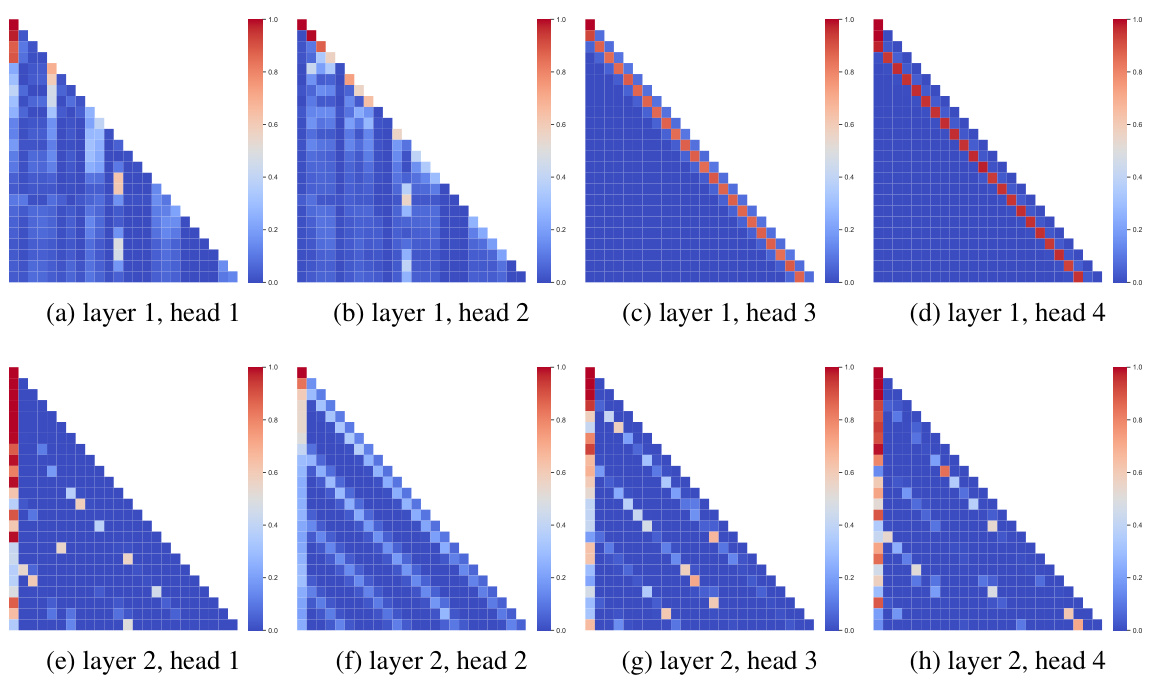

This figure shows the visualization of attention maps and principal component analysis (PCA) of attention head features for models that generalize out-of-distribution (o.o.d) and those that don’t. The o.o.d. generalizing models exhibit highly structured attention maps and PCA patterns forming ‘circles of circles’, indicating the emergence of structured representations that are crucial for generalization. In contrast, models lacking o.o.d. generalization show less structured patterns, highlighting the relationship between structured representations and the ability to generalize to unseen tasks.

This figure shows the attention maps and principal component analysis (PCA) of attention head outputs for models that generalize out-of-distribution (OOD) and those that do not. The OOD models exhibit highly structured attention patterns and PCA plots, forming ‘circles of circles.’ The structure is consistent across different task vectors and shot choices. In contrast, models without OOD generalization show less structured attention maps and PCA plots, demonstrating a correlation between structured representations and OOD generalization ability.

This figure shows the analysis of attention heads in models that generalize out-of-distribution (o.o.d.) and those that do not. The left panels show attention maps which are more structured in the o.o.d. generalizing models. The right panels show less structure. The bottom panels show principal component analysis (PCA) of the attention features. The o.o.d. generalizing models show circular patterns, while the non-generalizing models show less structure. This demonstrates that the structured attention patterns are correlated with the ability to generalize o.o.d.

This figure displays the attention patterns of all attention heads in a depth-2 model. Each subplot shows an attention head’s attention weights, visualized as a heatmap. These heatmaps illustrate the connections and dependencies between different tokens in the input sequence, providing insights into how the model processes information within each head. The patterns observed could reveal specific strategies or mechanisms utilized by the model for processing sequential data and achieving its tasks.

This figure shows the attention maps and principal component analysis (PCA) of the features from attention heads in models with and without out-of-distribution generalization ability. The models that generalize well exhibit highly structured attention maps and PCA patterns forming circles, indicating structured representations. In contrast, models without o.o.d. generalization show less structure. The PCA analysis highlights how the representation changes with the input and the task, and how this structure degrades when the model does not generalize well.

This figure shows the attention maps and PCA analysis of the attention heads in models that generalize out-of-distribution (o.o.d.) versus those that do not. The left side shows models exhibiting structured attention maps and PCA patterns forming ‘circles of circles.’ The structure is consistent across different task vectors and shot choices, indicating a robust, generalized representation. The right side shows models without o.o.d. generalization, exhibiting less structured attention maps and PCA patterns. The lack of structure suggests a memorization-based approach rather than a generalized algorithm.

This figure shows the attention maps and PCA analysis of the attention heads and MLPs for models with and without out-of-distribution generalization ability. The left panels (a,b) show models with strong o.o.d. generalization, exhibiting highly structured attention maps and PCA patterns forming concentric circles. These patterns are consistent across different task vectors and shots. The right panels (c,d) display models lacking o.o.d. generalization, showing less structured attention maps and PCA patterns, indicating a relationship between structured representations and the ability to generalize to unseen tasks. This demonstrates that the model’s ability to generalize is connected to the structure of its representations.

This figure compares the performance of 4-layer and 2-layer transformer models on a modular arithmetic task. It shows that the 4-layer model is better able to generalize to unseen inputs by combining information from multiple in-context examples (using Modular Regression), while the 2-layer model struggles with this task, relying more heavily on simpler pattern matching (Ratio Matching). The figure uses a grid of inputs to systematically evaluate model performance and highlights the differences in algorithmic strategies employed by the models of different depths.

This figure displays cosine similarity matrices for the outputs of different layers in depth-2 and depth-4 models. The matrices show the cosine similarity between the output vectors for different input pairs (x, y) and (x’, y’). The depth-4 model shows a clear transition from Ratio Matching (earlier layers) to Modular Regression (later layers), indicated by the characteristic patterns in the cosine similarity matrices. The depth-2 model shows less structured patterns, suggesting it relies more heavily on Ratio Matching.

This figure displays cosine similarity matrices for layer outputs at token positions z and y in both d=2 and d=4 models, illustrating the internal representations and algorithmic shifts. The d=4 model shows a transition from Ratio Matching to Modular Regression as more in-context examples are provided, reflected in distinctive patterns across layers. The d=2 model exhibits a simpler pattern, mainly showing Ratio Matching.

This figure displays cosine similarity matrices for layer outputs at token positions y and z for both d=4 and d=2 models. The d=4 model shows a distinctive kaleidoscopic pattern in layer 3, indicative of generating all possible y/x ratios for calculations, while transitioning to Modular Regression in the final layer. The d=2 model exhibits a simpler pattern, utilizing Ratio Matching primarily, with layer 2 identifying relevant y/x ratios from given examples.

This figure shows cosine similarity matrices for layer outputs at token positions z and y for both d=4 and d=2 models. The d=4 model exhibits kaleidoscopic patterns in layer 3, suggesting the generation of all possible y/x ratios. In contrast, the d=2 model shows simpler patterns, reflecting the differences in algorithmic complexity between the two models and their transition from Ratio Matching to Modular Regression.

This figure shows a phase diagram for a depth-6 transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. The diagram illustrates the transition from in-distribution to out-of-distribution generalization as the number of pre-training tasks increases. It also shows the effect of training steps and the number of in-context examples on the model’s accuracy. The model exhibits a transient phase where out-of-distribution generalization is observed but eventually degrades with prolonged training, particularly noticeable when the number of pre-training tasks is 28. This suggests a trade-off between memorization and generalization in the model’s learning dynamics.

This figure shows the phase diagram for a 6-layer transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. The diagram illustrates four distinct phases of generalization: in-distribution memorization, in-distribution generalization, out-of-distribution memorization, and out-of-distribution generalization. The transition between these phases depends on the number of pre-training tasks and the number of in-context examples. The plots also show the training accuracy and out-of-distribution test accuracy as a function of the training steps and the number of shots, highlighting the transient nature of out-of-distribution generalization for certain model configurations.

This figure shows the phase diagram for a six-layer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. The diagram illustrates four distinct phases depending on the number of training tasks and the fraction of training data used. The phases are: in-distribution memorization, in-distribution generalization, out-of-distribution memorization, and out-of-distribution generalization. The figure also shows the training accuracy and out-of-distribution test accuracy as functions of the number of training steps and the number of in-context examples. Finally, it demonstrates how the out-of-distribution generalization ability of the model first improves and then degrades as training progresses.

This figure shows the phase diagram for a 6-layer transformer model trained on modular arithmetic tasks. The diagrams illustrate the model’s performance across four distinct phases as the number of pre-training tasks and the fraction of training data used for few-shot learning vary. The phases represent different levels of generalization capability, ranging from memorization of training data to out-of-distribution generalization. Importantly, the figure also highlights a trade-off between in-distribution and out-of-distribution generalization, particularly for a model with 28 pre-training tasks. Additional plots show the training loss and accuracy as a function of training steps and the number of few-shot examples, emphasizing the transient nature of out-of-distribution generalization in deeper models and the impact of context length.

This figure shows the effect of varying task difficulties (controlled by the value of p) on the model’s ability to generalize out-of-distribution. The x-axis represents the number of pre-training tasks (ni.d.), and the y-axis shows both the loss and the accuracy. Different lines represent different values of p (29, 37, 47). The results indicate that as the task difficulty increases (larger p), the model requires a greater number of pre-training tasks to achieve out-of-distribution generalization.

Full paper#