↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current research on Chain-of-Thought (CoT) in large language models (LLMs) lacks quantitative metrics and optimization guidance. This limits our understanding and hinders progress in improving LLM reasoning capabilities. Existing studies offer qualitative assessments, but lack the quantitative tools needed for objective comparison and optimization.

This paper introduces a Reasoning Boundary Framework (RBF) to address these limitations. RBF defines a reasoning boundary (RB) to quantify CoT’s upper bound and establishes a combination law for multiple RBs. It also proposes three categories of RBs for optimization, guiding improvements through RB promotion and reasoning path optimization. The framework’s effectiveness is validated through extensive experiments, providing insights into CoT strategies and offering valuable guidance for future optimization efforts.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) and chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting. It provides a novel framework for quantifying and optimizing CoT reasoning, addressing critical gaps in existing research. The quantitative metrics and optimization strategies proposed can significantly advance the field, paving the way for more effective and efficient LLM applications.

Visual Insights#

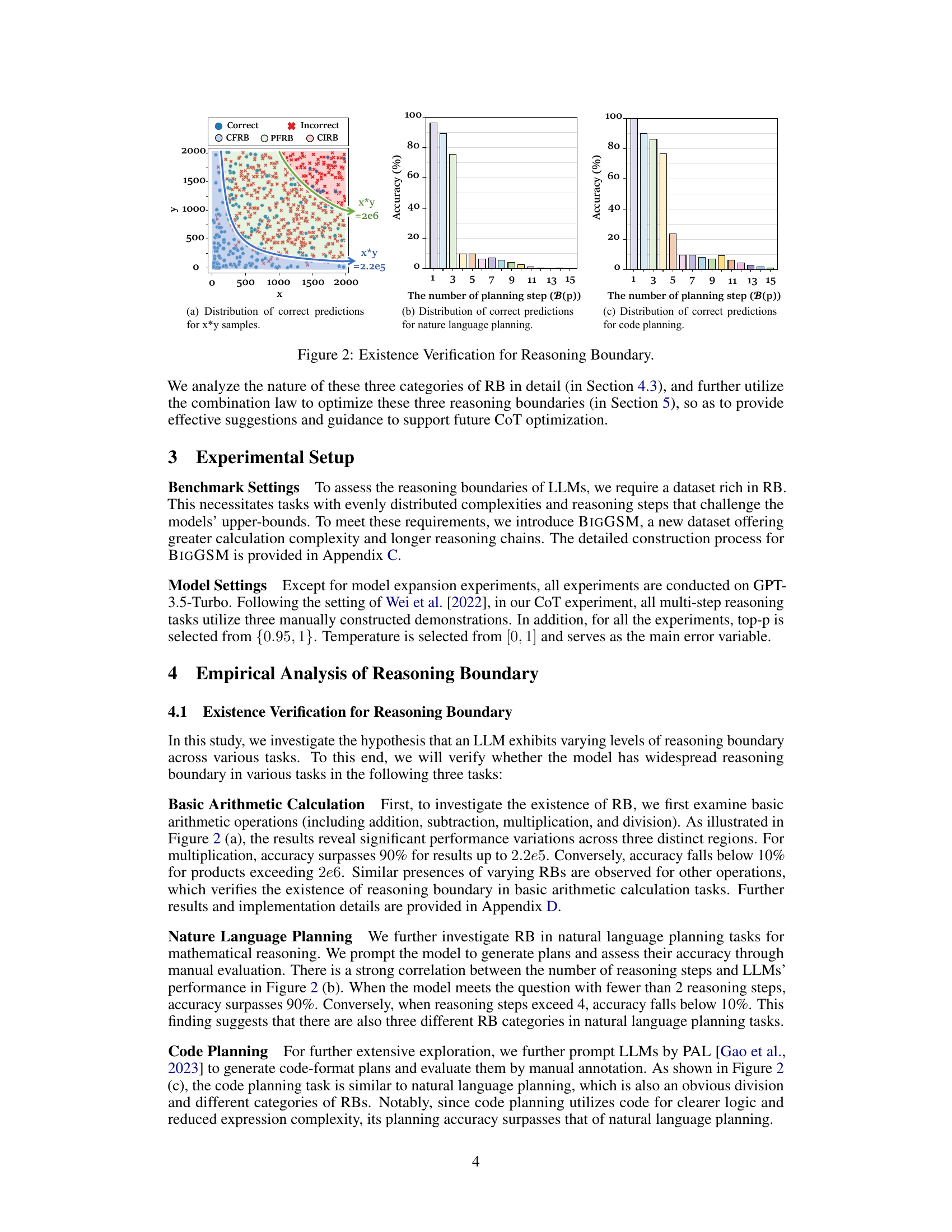

This figure provides a visual representation of the three core concepts introduced in the paper: Reasoning Boundary (RB), Combination Law of Reasoning Boundary, and Categories of Reasoning Boundary. The Reasoning Boundary illustrates how a model’s accuracy changes as task difficulty increases, with the boundary representing the point where accuracy significantly degrades. The Combination Law demonstrates how multiple RBs can be combined to quantify the upper bound of a more complex CoT task. Finally, the Categories of Reasoning Boundary shows three classifications of RBs based on accuracy: Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary (CFRB), Partially Feasible Reasoning Boundary (PFRB), and Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary (CIRB).

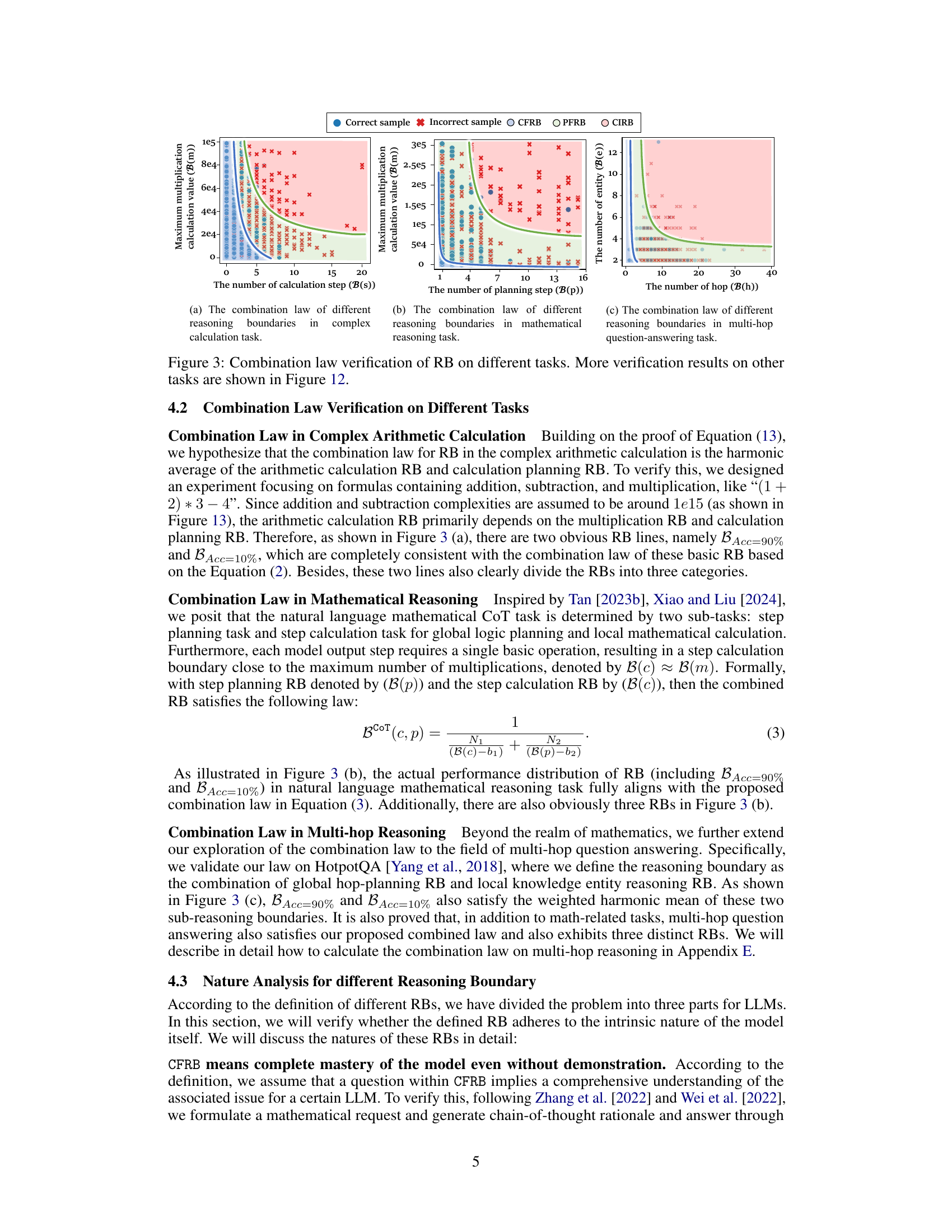

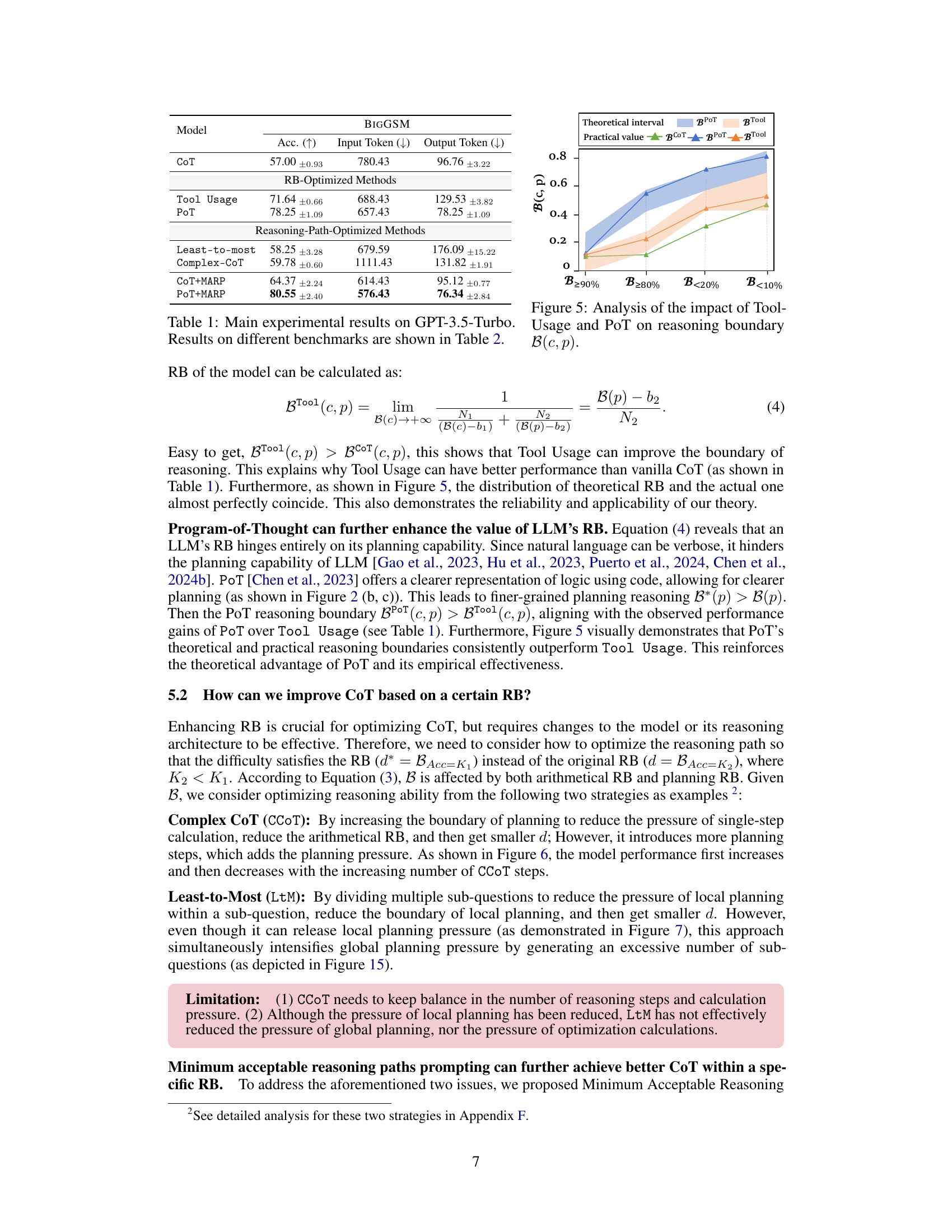

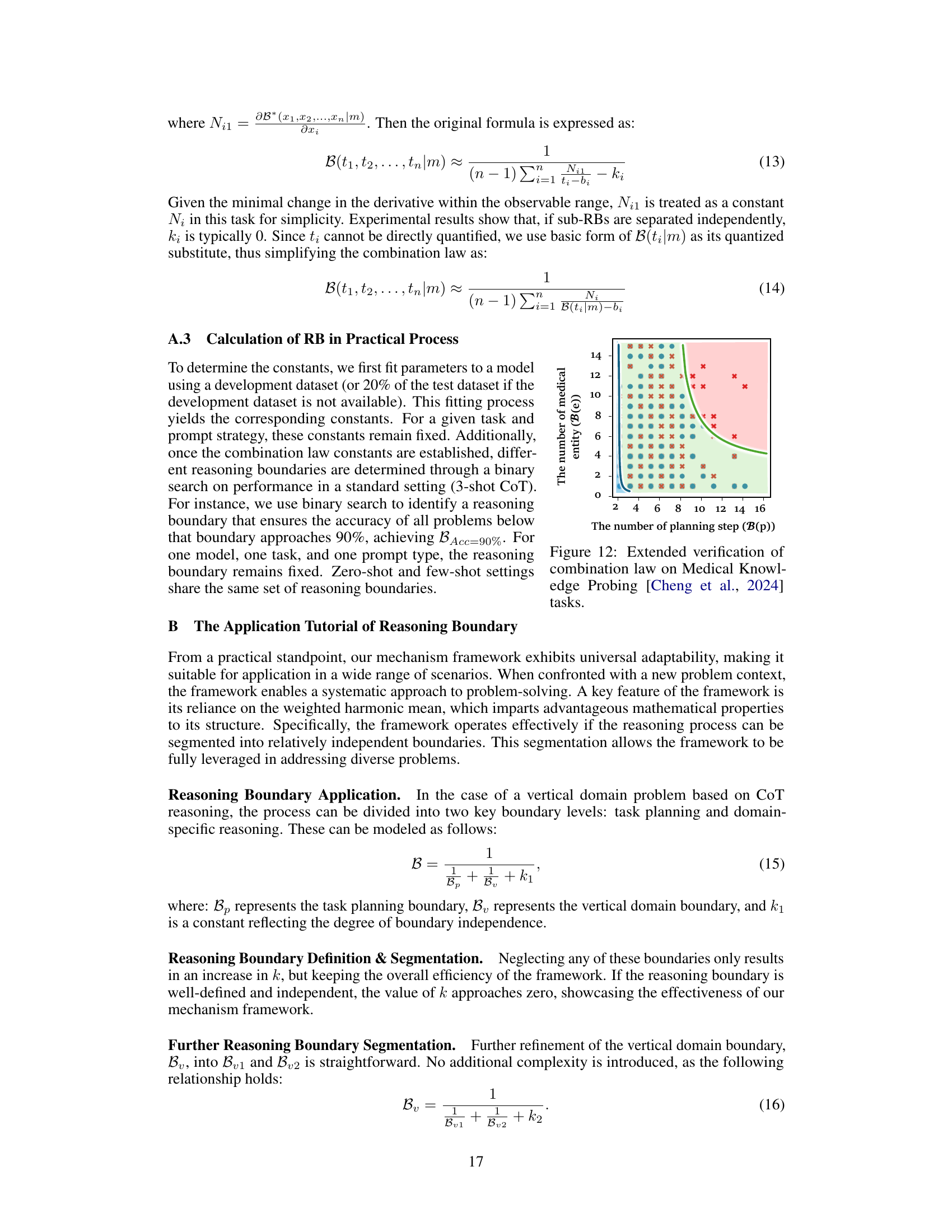

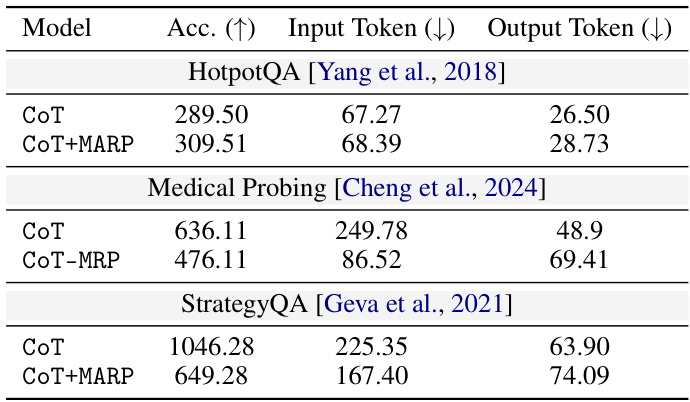

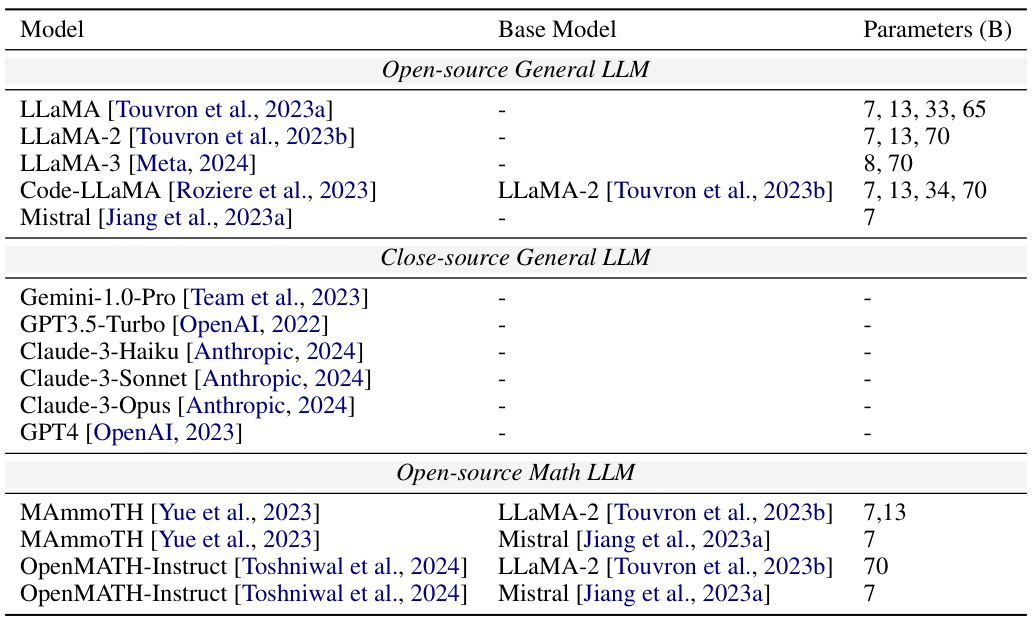

This table presents the main experimental results obtained using the GPT-3.5-Turbo model. It shows the accuracy, input token count, and output token count for various methods on the BIGGSM benchmark. The methods are categorized into three groups: CoT (Chain-of-Thought), RB-Optimized Methods (methods focusing on optimizing reasoning boundaries), and Reasoning-Path-Optimized Methods (methods focusing on optimizing the reasoning path). The table highlights the impact of different optimization strategies on model performance. More detailed benchmark results are provided in Table 2.

In-depth insights#

CoT Quantification#

CoT Quantification in large language models (LLMs) is a crucial yet underdeveloped area. Current methods often rely on qualitative assessments, hindering objective comparisons and the identification of performance limits. A robust CoT quantification framework should establish clear metrics for measuring the reasoning capabilities of LLMs. This would involve defining appropriate measures of reasoning complexity and accuracy, accounting for factors such as the number of reasoning steps, the type of reasoning involved, and the difficulty of the task. Further, the framework needs to handle the inherent variability within LLMs, perhaps by focusing on aggregate performance across multiple runs or by using techniques to measure consistency in reasoning paths. Benchmark datasets are necessary for evaluating and validating these metrics, requiring carefully designed tasks spanning different reasoning domains with varying levels of difficulty. Ultimately, a successful CoT quantification framework would enable a more precise understanding of LLMs’ capabilities, facilitate more targeted model development, and pave the way for more effective and efficient optimization strategies.

Reasoning Boundary#

The concept of “Reasoning Boundary” offers a novel framework for understanding the limitations of large language models (LLMs) in complex reasoning tasks. It proposes that LLMs have a quantifiable limit to their reasoning capabilities, a boundary beyond which their performance significantly degrades. This boundary isn’t static; it varies based on task type, model architecture, and input characteristics. The framework suggests methods to quantify this boundary, using metrics such as the maximum problem difficulty a model can solve with a given accuracy threshold. Further, it explores different categories of reasoning boundaries (e.g., completely feasible, partially feasible, and completely infeasible), each with implications for optimization strategies. Optimizing reasoning within these boundaries becomes crucial. The proposed framework provides valuable insights into improving LLM reasoning performance by either enhancing the reasoning capacity (e.g., via tool use or improved prompting) or by refining the reasoning process to operate within a model’s existing limits.

CoT Optimization#

The paper explores Chain-of-Thought (CoT) optimization strategies for large language models (LLMs). A key contribution is the reasoning boundary framework (RBF), which introduces the concept of a reasoning boundary (RB) to quantify the upper limit of an LLM’s reasoning capabilities. This framework helps to analyze the performance of different CoT strategies and guide optimization efforts. Three categories of RBs are defined (completely feasible, partially feasible, and completely infeasible), each representing different levels of model performance. The combination law of RBs provides a means to analyze the interaction of multiple reasoning skills within a CoT process. The optimization strategies focus on promoting RBs (increasing the upper limit of reasoning ability) and optimizing reasoning paths (improving the efficiency of the reasoning process). Experimental results across various models and tasks validate the framework’s efficacy and demonstrate how proposed optimizations can lead to improvements in CoT performance. The study highlights that understanding and optimizing reasoning boundaries is crucial for maximizing the potential of LLMs in complex reasoning tasks.

RB-based CoT#

The concept of ‘RB-based CoT’ integrates reasoning boundaries (RB) into the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting paradigm for large language models (LLMs). This framework offers a novel approach to quantify and optimize LLM reasoning capabilities. By defining RB as the upper bound of an LLM’s accuracy on a given reasoning task, it allows for a quantitative assessment of CoT performance across various tasks. This opens avenues for optimization strategies, focusing on both increasing the reasoning boundary (RB promotion) and improving the efficiency of reasoning pathways. Three categories of RBs (Completely Feasible, Partially Feasible, and Completely Infeasible) are proposed, facilitating targeted optimization efforts. This RB-based CoT framework thus provides a comprehensive methodology to understand and enhance LLM reasoning, moving beyond qualitative assessments to a more rigorous, quantitative approach for evaluating and improving the efficacy of CoT prompting.

Future of CoT#

The future of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting hinges on addressing its current limitations. Robust quantitative metrics are needed to objectively evaluate CoT’s performance across diverse models and tasks, moving beyond qualitative assessments. Developing optimization strategies that go beyond heuristic rule adjustments is crucial; this may involve incorporating insights from neural architecture search or learning more sophisticated reasoning paths. Bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application requires more research into the underlying mechanisms of CoT. Furthermore, exploring the potential of CoT in complex, real-world scenarios, such as multi-modal reasoning and decision-making, presents exciting avenues. Addressing the issue of computational cost is essential for wider adoption; research into more efficient CoT implementations is vital. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of CoT’s relationship with model architecture, training data, and other factors will be key to its long-term success.

More visual insights#

More on figures

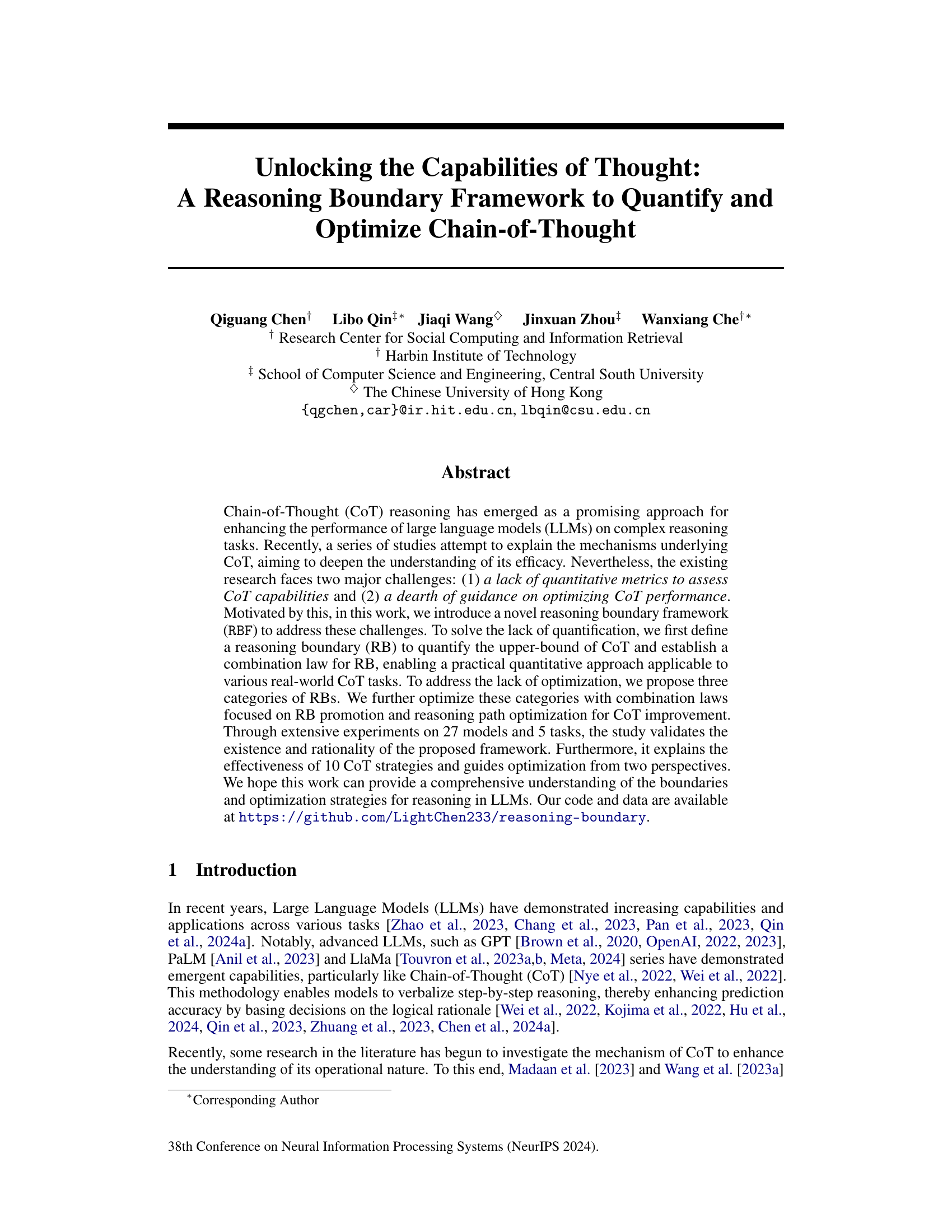

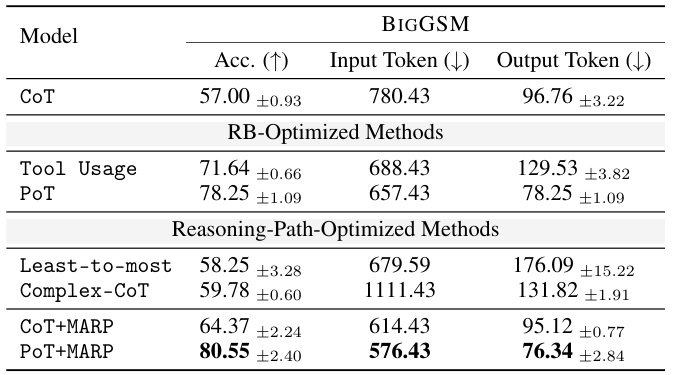

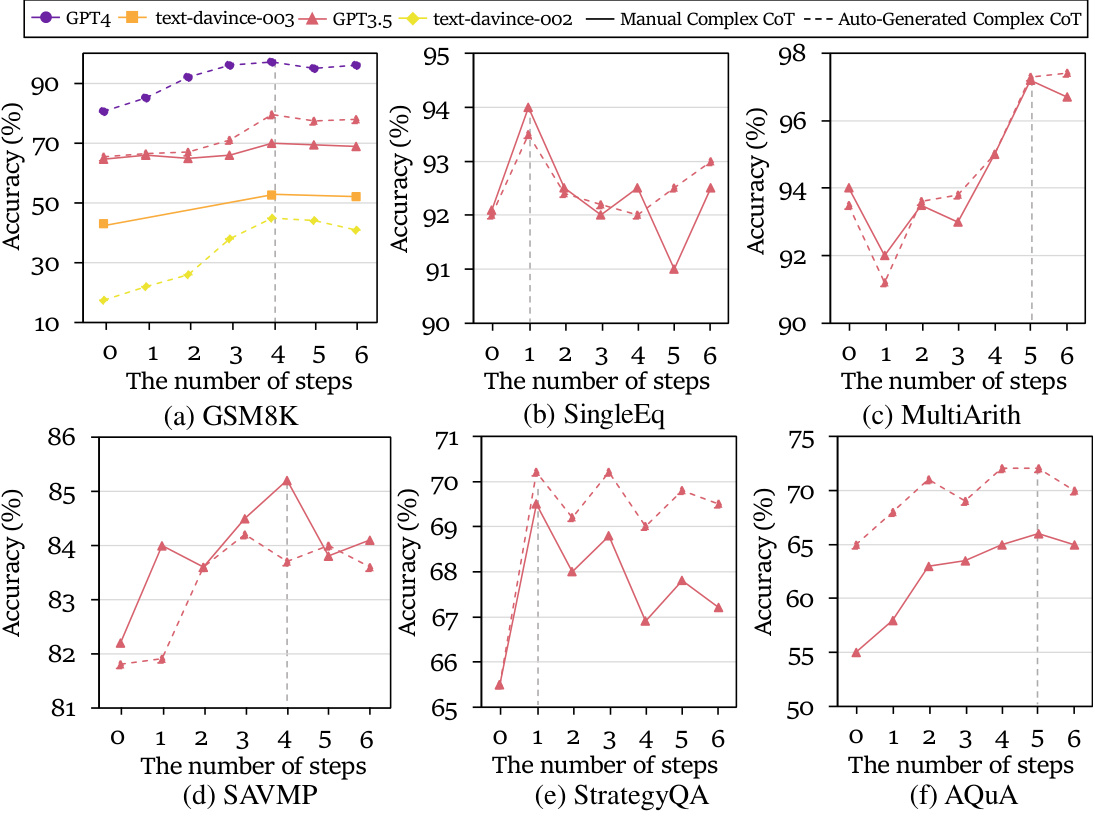

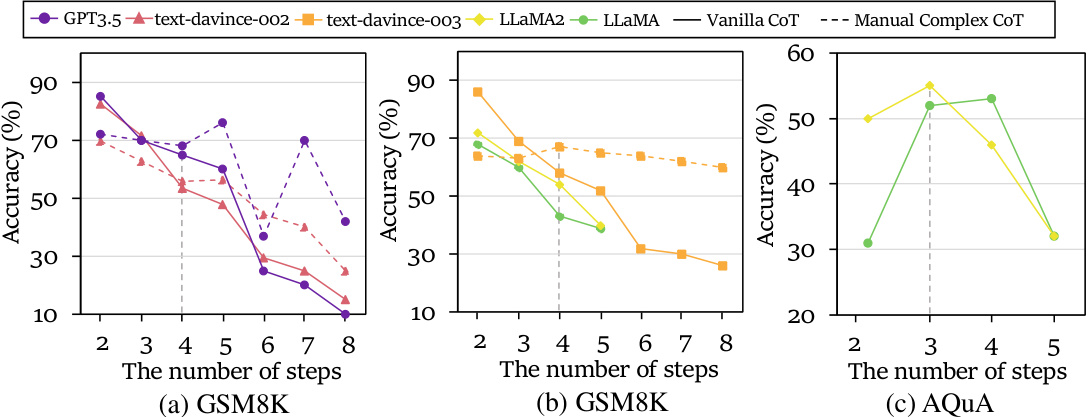

This figure demonstrates the existence and rationality of the proposed reasoning boundary (RB) framework. It shows the distribution of correct predictions for three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation (multiplication specifically), natural language planning, and code planning. In each case, the x-axis represents a measure of task difficulty, and the y-axis represents the model’s accuracy. The three distinct regions (Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary, Partially Feasible Reasoning Boundary, Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary) in each graph visually represent varying levels of model performance as a function of reasoning difficulty. This provides evidence for the existence of a reasoning boundary for LLMs.

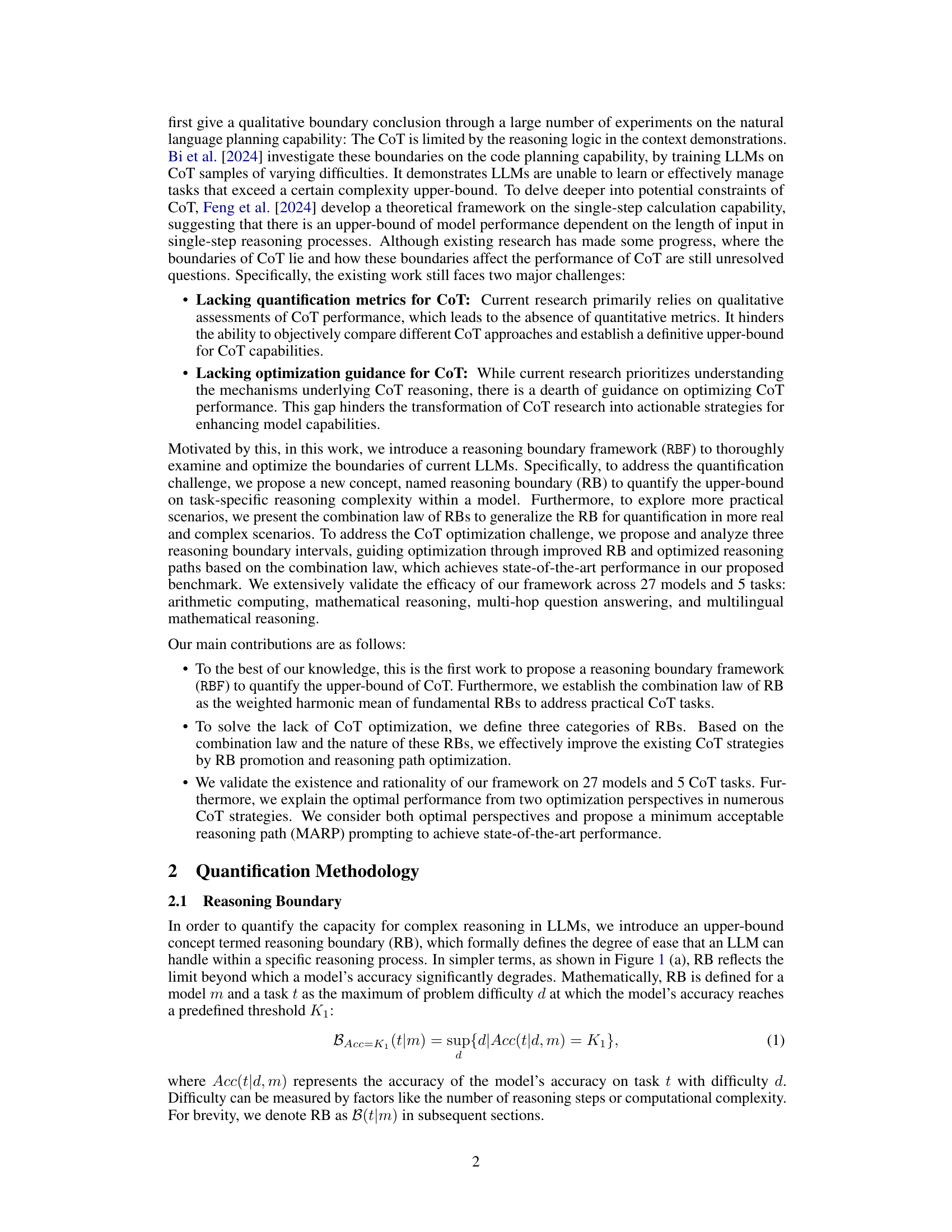

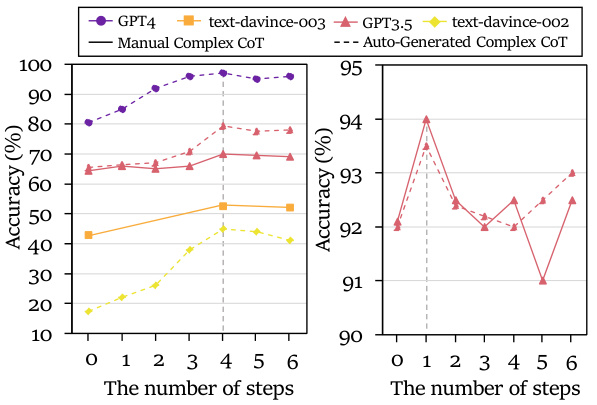

This figure displays the verification of the combination law of reasoning boundaries (RBs) across three different tasks: complex arithmetic calculation, mathematical reasoning, and multi-hop question answering. Each subplot shows the relationship between different RBs and the model’s accuracy. The combination law, represented mathematically in the paper, predicts how different reasoning abilities combine to influence overall task performance. The plots demonstrate the effectiveness of this combination law in practice, showing the predicted RB boundaries closely align with the empirical results. Figure 12 in the paper provides further verification results on additional tasks.

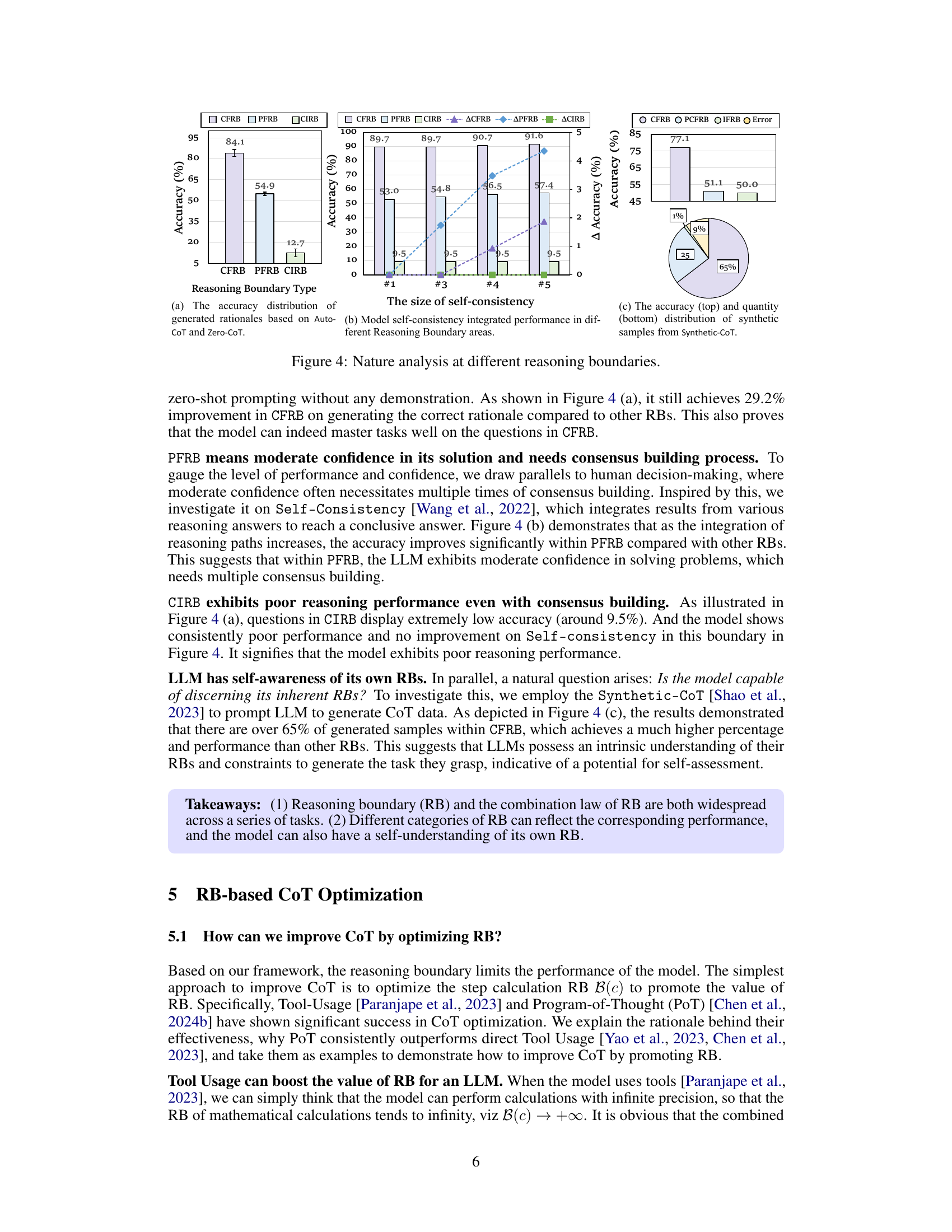

This figure presents a nature analysis of different reasoning boundaries (RBs) categorized as Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary (CFRB), Partially Feasible Reasoning Boundary (PFRB), and Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary (CIRB). Subfigure (a) shows the accuracy distribution of generated rationales based on Auto-CoT and Zero-CoT, highlighting the varying success rates across the RB categories. Subfigure (b) illustrates the performance enhancement through model self-consistency integrated across the different RB areas, revealing how the method improves performance specifically in PFRB (partially feasible). Subfigure (c) shows the accuracy and quantity distribution of synthetic samples generated through Synthetic-CoT, demonstrating the model’s self-awareness of its own reasoning boundaries. The results indicate the model’s capabilities and confidence level varies depending on the task difficulty, confirming the validity and relevance of the proposed reasoning boundary framework.

This figure displays the impact of Tool Usage and Program-of-Thought (PoT) on the reasoning boundary (RB). It compares the theoretical and practical values of RB for different accuracy thresholds (B≥90%, B≥80%, B<20%, B<10%). The shaded areas represent theoretical intervals for Tool Usage and PoT, while the points show practical values for vanilla CoT, PoT, and Tool Usage. The results demonstrate that Tool Usage and PoT effectively improve reasoning boundary by enhancing model performance.

This figure shows the results of experiments to verify the existence of reasoning boundaries in three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation, natural language planning, and code planning. The plots show the relationship between the accuracy of the model and the difficulty of the task (measured by the number of planning steps or the magnitude of numbers involved). In each task, the model’s performance exhibits significant variation across three distinct regions corresponding to three categories of Reasoning Boundaries: Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary (CFRB), Partially Feasible Reasoning Boundary (PFRB), and Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary (CIRB). The results verify that the reasoning boundaries exist and vary across different tasks, supporting the proposed framework’s main hypothesis.

The figure displays the results of experiments conducted to verify the existence of Reasoning Boundary (RB) across three distinct tasks: basic arithmetic calculations, natural language planning, and code planning. It visually demonstrates that LLMs exhibit varying performance levels depending on task complexity, showcasing three distinct regions of RB: completely feasible (CFRB), partially feasible (PFRB), and completely infeasible (CIRB). The graphs illustrate the relationship between accuracy and task difficulty (e.g., the number of reasoning steps or calculation magnitude), visually confirming the hypothesis that LLMs possess a reasoning boundary that limits their performance on complex reasoning tasks.

This figure shows the results of experiments designed to verify the existence of reasoning boundaries in LLMs across three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation, natural language planning, and code planning. Each graph shows the model’s accuracy across a range of difficulty levels, revealing distinct regions where performance is high (Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary), moderate (Partially Feasible Reasoning Boundary), and low (Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary). The results support the hypothesis that LLMs have a limited capacity for complex reasoning, with performance significantly degrading beyond a certain difficulty threshold, and that this threshold varies depending on the task.

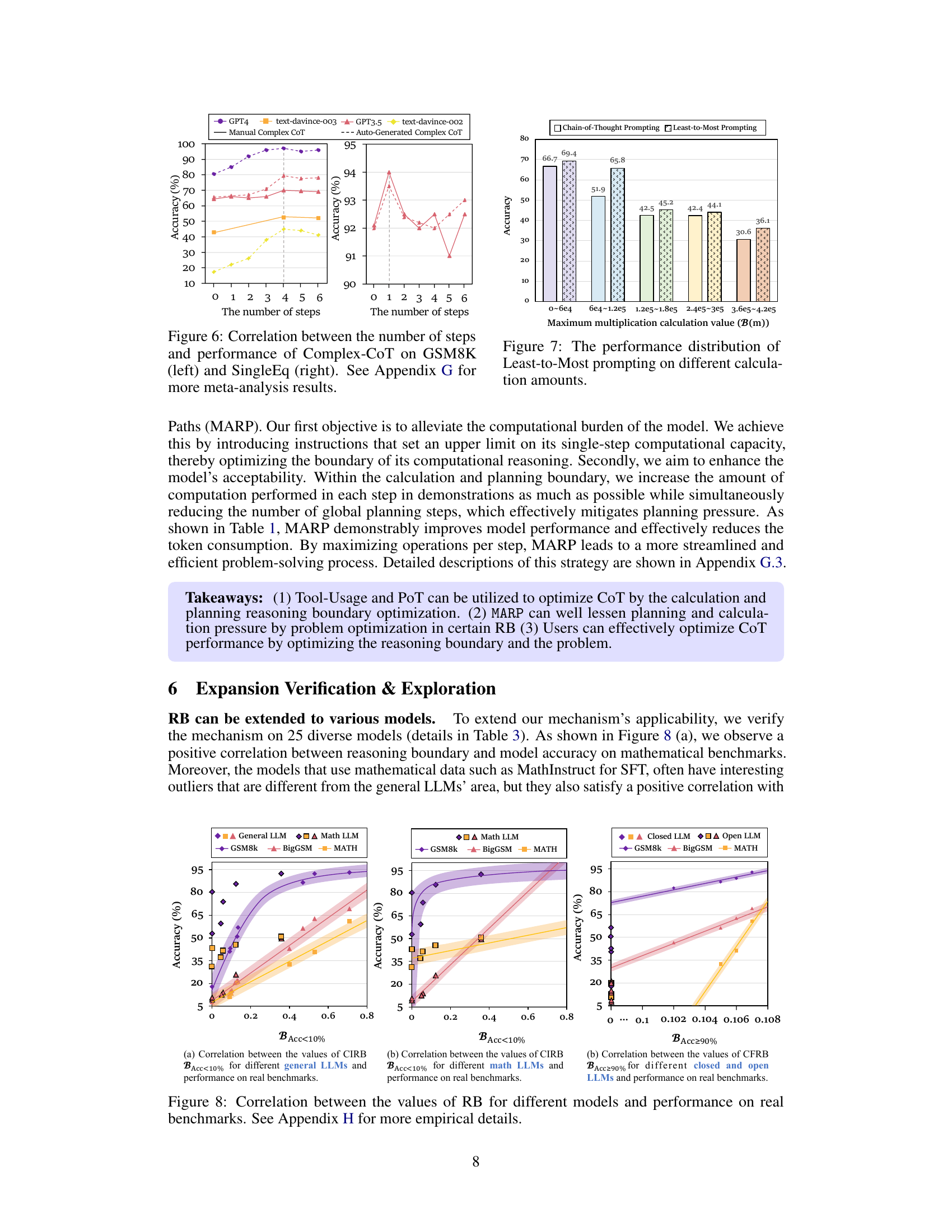

This figure displays the scaling law correlation between model parameters and the Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary (CIRB). It shows how CIRB, representing the lower bound of a model’s reasoning ability, changes as the number of parameters in the model increases. The upward trend suggests that larger models, with more parameters, generally exhibit a higher CIRB.

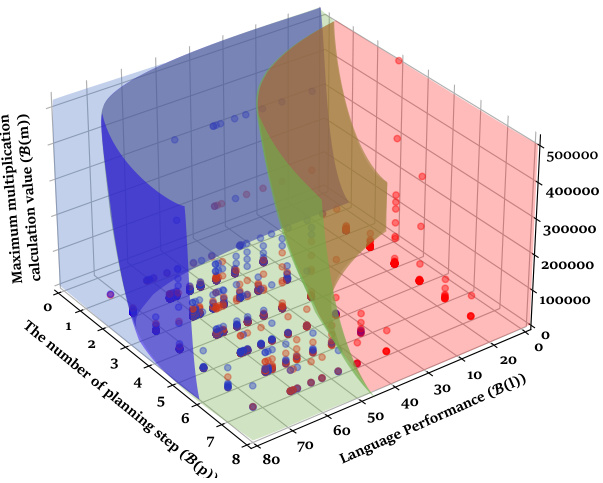

This 3D plot visualizes the different reasoning boundaries observed in the MGSM dataset. The x-axis represents the number of planning steps (B(p)), the y-axis represents language performance (B(l)), and the z-axis represents the maximum multiplication calculation value (B(m)). Different colors represent the three categories of reasoning boundaries: completely feasible (CFRB), partially feasible (PFRB), and completely infeasible (CIRB). The plot shows how the reasoning boundary changes with different numbers of planning steps, language performance, and calculation difficulty. This visualization helps in understanding the interplay of multiple factors in determining the overall reasoning capabilities of LLMs.

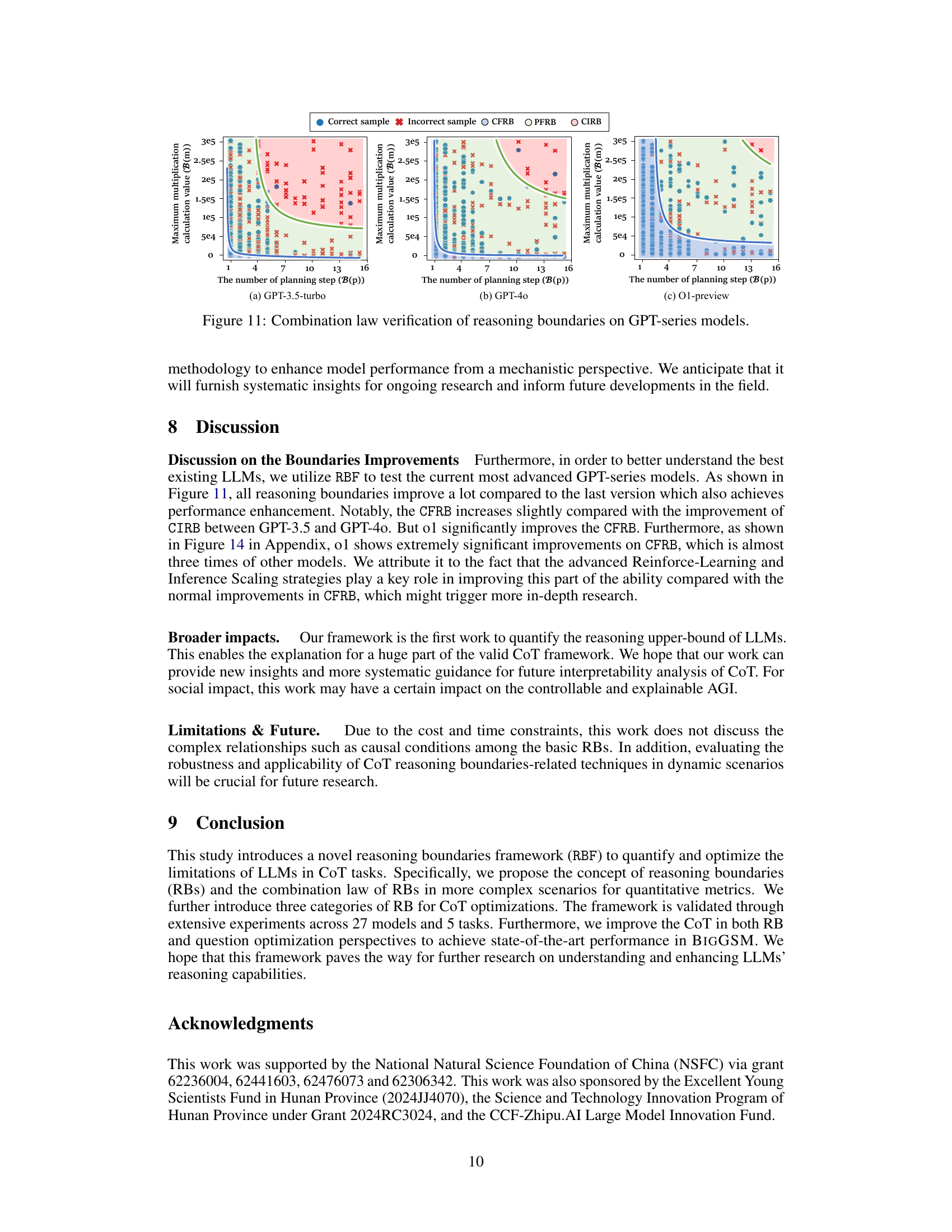

This figure shows the combination law verification of reasoning boundaries on three different GPT series models: GPT-3.5-turbo, GPT-4.0, and O1-preview. The x-axis represents the number of planning steps, while the y-axis shows the maximum multiplication calculation value. The colored dots represent different categories of reasoning boundaries (CFRB, PFRB, CIRB) based on the accuracy of the model’s predictions. The curves illustrate the boundaries separating these categories. The figure demonstrates that the combination law for reasoning boundaries holds across different models and tasks.

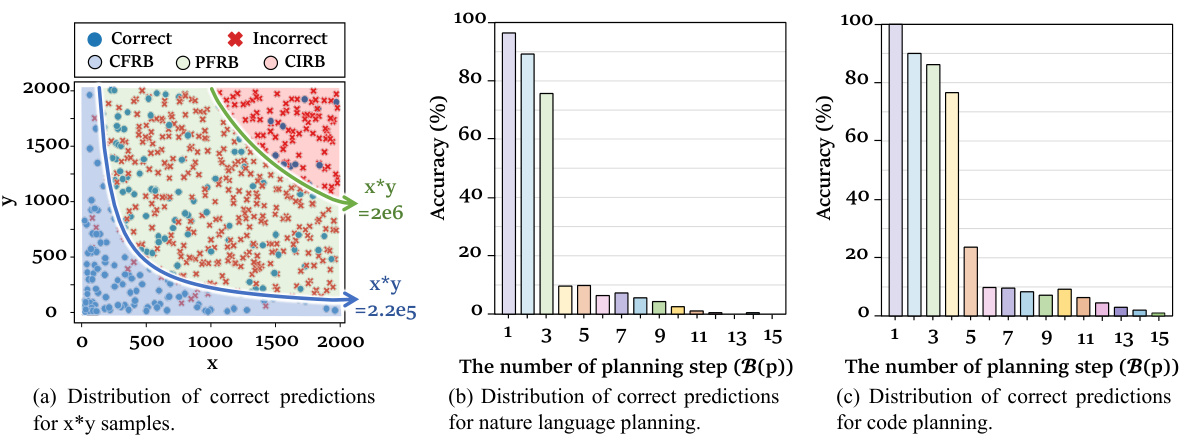

This figure shows the extended verification of the combination law of reasoning boundary on the Medical Knowledge Probing dataset. The x-axis represents the number of planning steps, and the y-axis represents the number of medical entities. The colored regions represent different categories of reasoning boundary (CFRB, PFRB, CIRB), based on the model’s accuracy. The points plotted show the actual results from the experiments, illustrating the relationship between the number of planning steps and medical entities in determining the reasoning boundary. This visualization confirms that the combination law accurately predicts the reasoning boundary in this complex task, demonstrating its broad applicability.

This figure shows the results of experiments designed to verify the existence of reasoning boundaries in three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation, natural language planning, and code planning. The plots visualize the relationship between task difficulty (e.g., number of planning steps, size of numbers) and the model’s accuracy. Distinct regions of high accuracy (Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary), moderate accuracy (Partially Feasible Reasoning Boundary), and low accuracy (Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary) are observed, supporting the concept of a reasoning boundary.

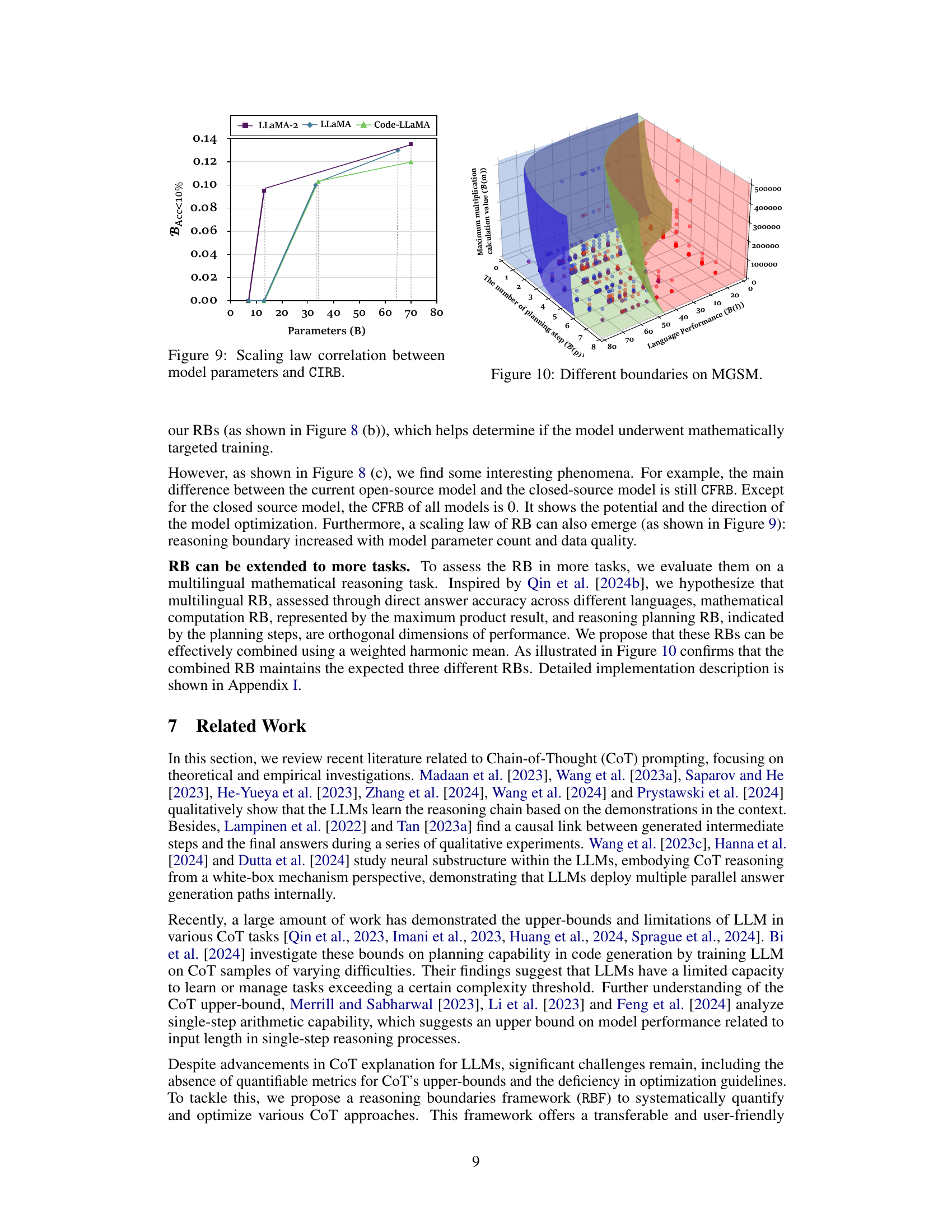

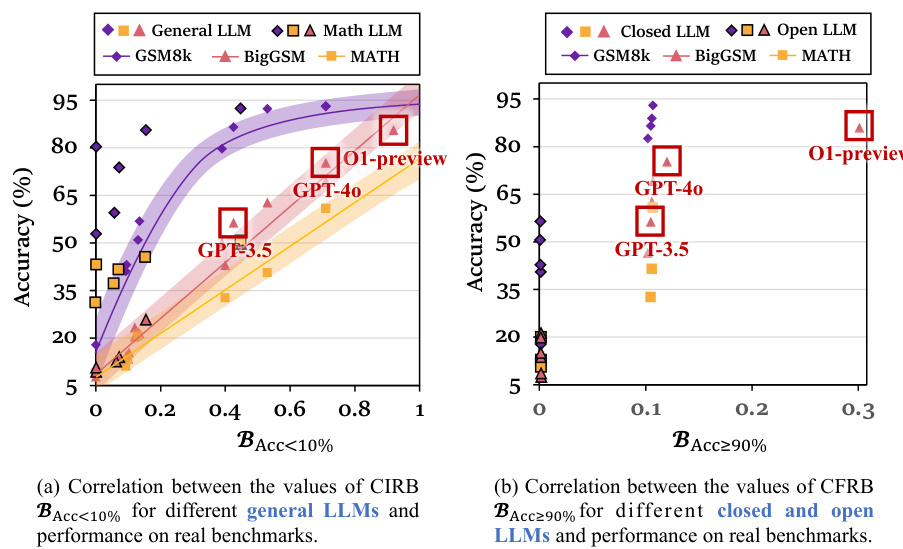

This figure shows the correlation between the reasoning boundary (RB) values and the model’s performance on real-world benchmarks. Panel (a) focuses on the correlation between the Completely Infeasible Reasoning Boundary (CIRB) and performance for different general and mathematical LLMs. Panel (b) shows the correlation between the Completely Feasible Reasoning Boundary (CFRB) and performance for different closed and open LLMs. Appendix H provides more detailed empirical results.

This figure shows the existence of reasoning boundaries (RB) in three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation, natural language planning, and code planning. Each sub-figure displays the distribution of correct and incorrect predictions for various difficulty levels. For example, in (a), the x-axis represents the value of the multiplication calculation, showing high accuracy for smaller values but sharply decreasing accuracy beyond a certain threshold. Similarly, (b) and (c) illustrate the effects of the number of planning steps in natural language and code planning tasks, respectively. These results confirm that LLMs exhibit varying levels of reasoning capacity and limitations across different tasks.

This figure shows the results of experiments conducted to verify the existence of reasoning boundaries in three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation, natural language planning, and code planning. The graphs visually demonstrate that model performance varies significantly across different difficulty levels. There are three distinct regions: high accuracy (completely feasible), moderate accuracy (partially feasible), and low accuracy (completely infeasible). This variation in performance supports the existence of reasoning boundaries as a measurable concept, reflecting limitations in the model’s reasoning capabilities.

This figure shows the results of experiments designed to verify the existence of reasoning boundaries in LLMs across three different tasks: basic arithmetic calculation, natural language planning, and code planning. The plots show the accuracy of the model’s predictions as a function of the problem difficulty (measured as the number of planning steps or the magnitude of the calculation). The results demonstrate that in each task, there is a clear reasoning boundary beyond which the model’s performance decreases significantly. The three distinct regions represent completely feasible reasoning boundary (CFRB), partially feasible reasoning boundary (PFRB), and completely infeasible reasoning boundary (CIRB).

More on tables

This table shows the main experimental results obtained using the GPT-3.5-Turbo model. It presents accuracy, input token count, and output token count for various Chain-of-Thought (CoT) methods across different tasks and models. The results highlight the impact of various optimization techniques on the performance of large language models for complex reasoning tasks. More detailed benchmark results are available in Table 2.

This table presents the main experimental results obtained using the GPT-3.5-Turbo model. It shows the accuracy, input tokens, and output tokens for several different methods, including the baseline Chain-of-Thought (CoT) approach and various RB-based optimization methods such as Tool Usage, Program-of-Thought (PoT), and reasoning path optimization methods. The results highlight the impact of these methods on improving the reasoning capabilities of the model. A second table (Table 2) provides results for different benchmarks.

Full paper#