↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Adapting large language models (LLMs) to new tasks efficiently is crucial. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) methods like LoRA offer a solution, but often underperform compared to full fine-tuning, especially with complex datasets. This is because of training interference between tasks and inefficient parameter usage.

HydraLoRA, a novel asymmetric LoRA architecture, tackles this by using a shared parameter matrix for commonalities across tasks while having specialized matrices for each task’s unique aspects. This asymmetric structure automatically identifies and adapts to “intrinsic components” within datasets, improving efficiency and performance over traditional LoRA and other PEFT methods. The method leverages a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) framework for enhanced inference. Experimental results show significant improvements across various benchmarks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical challenge in large language model (LLM) adaptation: the trade-off between efficiency and performance in parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT). HydraLoRA offers a novel solution by improving the efficiency of LoRA without sacrificing performance, opening new avenues for research on more efficient and effective LLM adaptation techniques and benefiting the broader AI community.

Visual Insights#

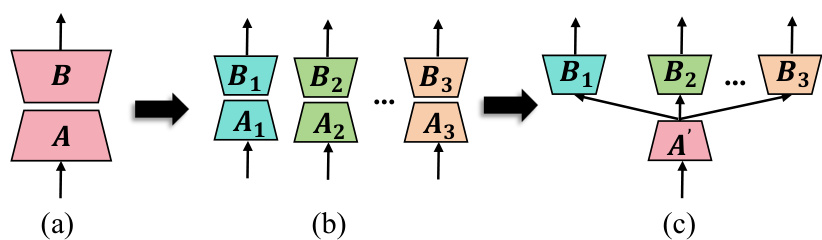

This figure illustrates the evolution of the LoRA architecture from its original symmetric form to the asymmetric HydraLoRA. Panel (a) shows the standard LoRA with matrices A and B. Panel (b) demonstrates how a single, larger LoRA can be broken into multiple smaller LoRA units to alleviate training interference. Panel (c) presents the final HydraLoRA architecture, which utilizes a shared A matrix across multiple B matrices for improved efficiency.

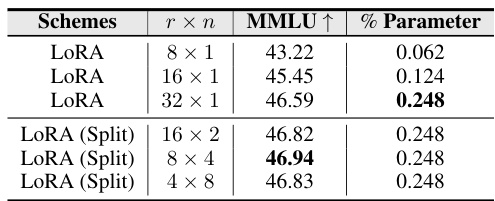

This table presents the performance of different LoRA configurations on the instruction tuning task using Dolly-15K and evaluated using MMLU. It shows the impact of varying the rank (r) and number (n) of LoRA modules on the final performance. The ‘LoRA (Split)’ configurations demonstrate that splitting a high-rank LoRA into multiple smaller LoRAs can improve performance.

In-depth insights#

LoRA Limitations#

LoRA, while efficient, suffers from limitations primarily concerning performance relative to full fine-tuning, especially with complex datasets. The low-rank approximation inherent in LoRA can restrict the model’s capacity to learn intricate relationships within data, leading to suboptimal performance on tasks requiring a broader parameter space. Another key limitation is the potential for interference between tasks when adapting a single LoRA model to multiple downstream applications. This interference manifests as performance degradation compared to training separate LoRA models for each task. Furthermore, the optimal rank for the low-rank decomposition is often task-specific and requires careful tuning; a suboptimal choice can significantly impact performance. LoRA’s reliance on rank decomposition also introduces challenges regarding the effective initialization and training of the low-rank matrices. Finally, LoRA’s effectiveness can be sensitive to dataset characteristics, with performance often degrading when dealing with heterogeneous or imbalanced datasets.

HydraLoRA Design#

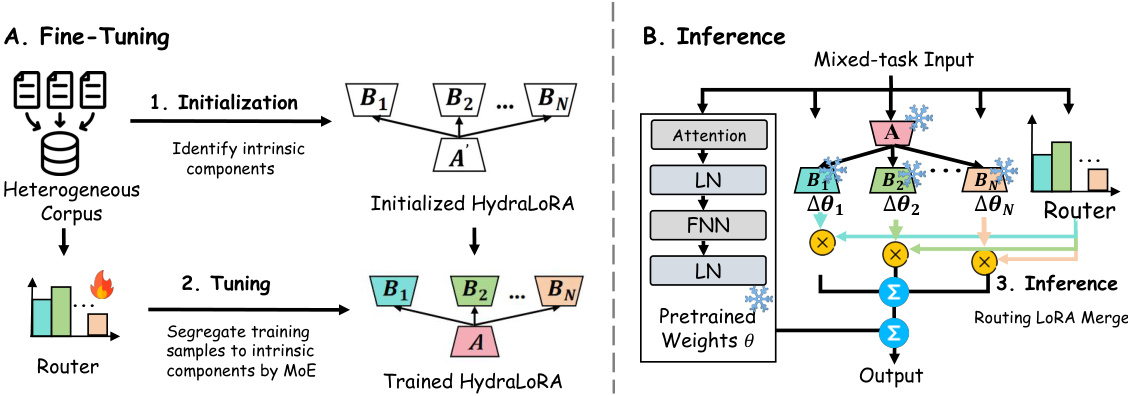

The HydraLoRA design cleverly addresses limitations of traditional LoRA by introducing an asymmetric architecture. Unlike LoRA’s symmetric structure with paired rank decomposition matrices (A and B) for each layer, HydraLoRA employs a shared A matrix across multiple tasks and distinct B matrices for each specific task or subdomain. This asymmetry allows HydraLoRA to learn shared, common features through the A matrix, while effectively capturing task-specific nuances through separate B matrices, thereby reducing redundancy and improving efficiency. The design also incorporates a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) approach to manage the multiple B matrices during both training and inference, dynamically routing inputs to the relevant expert. This adaptive routing removes the need for manual task assignment or domain expertise, making HydraLoRA highly flexible and robust for diverse downstream tasks. Automatic identification of intrinsic components within a dataset further enhances HydraLoRA’s adaptability and overall effectiveness, improving upon the performance of previous parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods.

Multi-task Tuning#

Multi-task tuning in large language models (LLMs) presents a significant challenge due to potential interference between tasks. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, while efficient, often underperform compared to full fine-tuning, especially in heterogeneous datasets. This is because a single LLM might not be optimal for multiple tasks within a single dataset. Effective multi-task tuning strategies need to address this inherent conflict. One approach is to utilize multiple, smaller LoRA heads, each dedicated to a specific downstream task, minimizing interference. This modular approach allows for specialized adaptation to task-specific nuances, but may increase overall parameter count compared to a monolithic LoRA. HydraLoRA addresses this by employing a shared A matrix (for commonalities) and multiple B matrices (for task-specific diversities), creating an asymmetric structure. This asymmetric approach reduces redundancy and improves efficiency, while the use of a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) router ensures flexible and dynamic merging of B matrices during inference, further enhancing efficiency and adapting to diverse tasks.

Efficiency Analysis#

An efficiency analysis of a large language model (LLM) fine-tuning method would require a multifaceted approach. It should examine parameter efficiency, comparing the number of trainable parameters in the proposed method against traditional full fine-tuning and other parameter-efficient techniques. Key metrics would include the relative performance achieved with fewer parameters. Next, computational efficiency needs to be assessed. This entails measuring training time, memory usage, and energy consumption, comparing the proposed method against existing methods. A crucial aspect is generalization performance: how well the fine-tuned model performs on unseen data and diverse tasks, demonstrating robustness. The analysis should also address implementation complexity: ease of integration into existing LLM pipelines and the level of expertise required. Finally, a cost-benefit analysis, considering the trade-off between performance gains and resource consumption, is crucial. A strong efficiency analysis would use rigorous quantitative metrics and detailed comparisons, providing strong evidence for the advantages of the proposed method.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from the HydraLoRA paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending HydraLoRA to other PEFT methods beyond LoRA would broaden its applicability and reveal insights into the general principles of efficient multi-task adaptation. Investigating the interplay between the MoE gating mechanism and the asymmetric LoRA architecture warrants further attention, potentially leading to improved routing strategies and enhanced performance. A deeper investigation into the optimal number of experts (B matrices) and their initialization techniques could also be beneficial. Exploring the robustness of HydraLoRA under various data conditions (e.g., noisy, imbalanced datasets) would provide valuable insights into its practical applicability. Finally, a thorough comparison with state-of-the-art methods in a broader range of multi-task scenarios is vital to establish its true performance capabilities and identify areas for future enhancements. The generalizability and efficiency of HydraLoRA across diverse LLMs is another intriguing area for future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

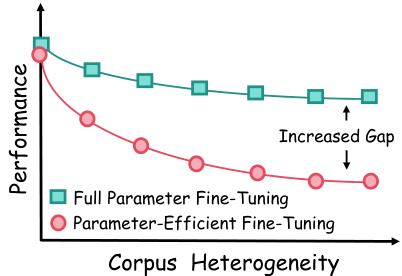

The figure shows two lines representing the performance of ‘Full Parameter Fine-tuning’ and ‘Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning’ methods as corpus heterogeneity increases. The line representing full fine-tuning shows a relatively small decrease in performance as heterogeneity increases, while the parameter-efficient line shows a much steeper decline. The difference between the two lines (the gap) widens as heterogeneity increases, illustrating the limitation of parameter-efficient methods when dealing with diverse datasets.

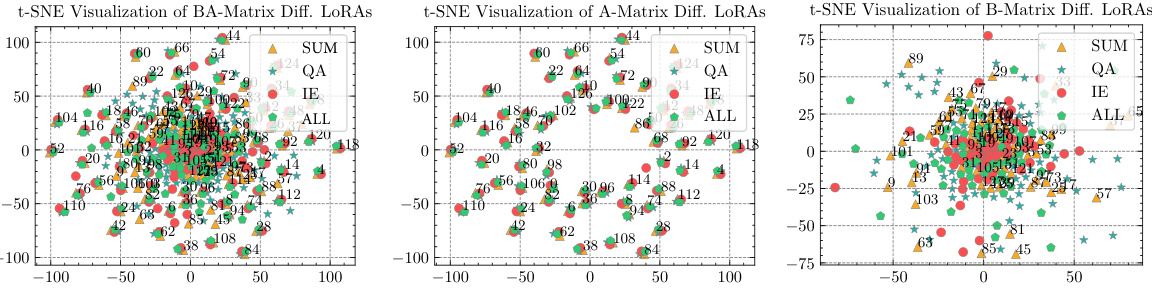

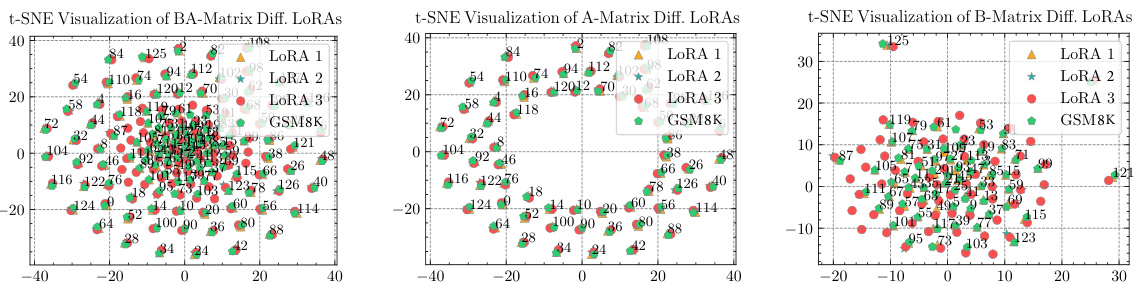

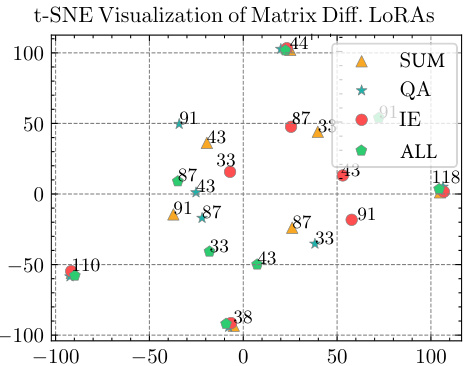

This figure uses t-SNE to visualize the parameters of LoRA modules trained on different subtasks of the Dolly-15K dataset. It shows that the parameters of matrix A (even submodules) are similar across different tasks, while the parameters of matrix B (odd submodules) are distinct, highlighting the role of matrix B in task-specific adaptation.

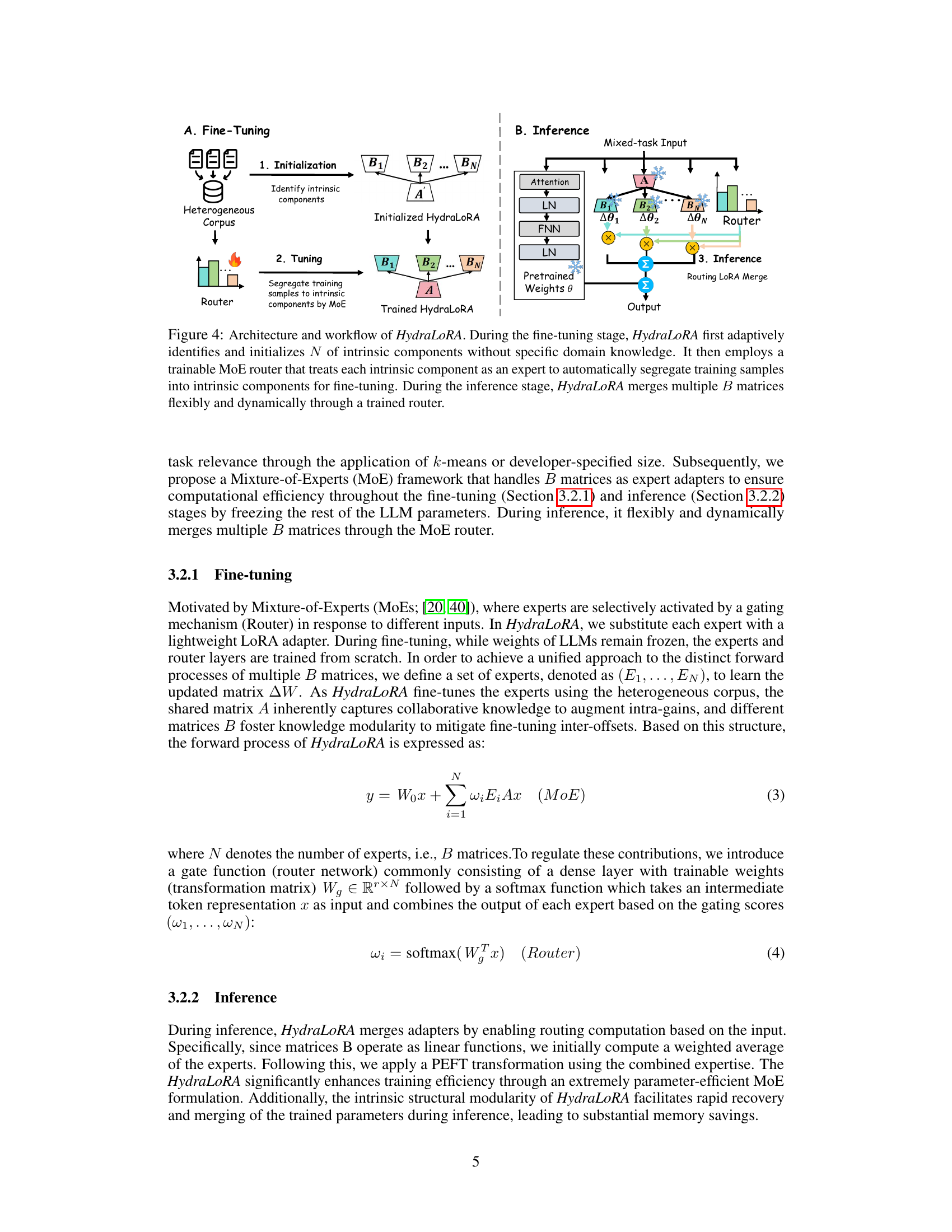

This figure illustrates the architecture and workflow of HydraLoRA, a novel asymmetric LoRA architecture. The fine-tuning process involves an adaptive identification and initialization of intrinsic components, followed by a training phase using a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) router to segregate training samples. During inference, multiple B matrices are merged dynamically using a trained router. This figure shows the process of both fine-tuning and inference phases.

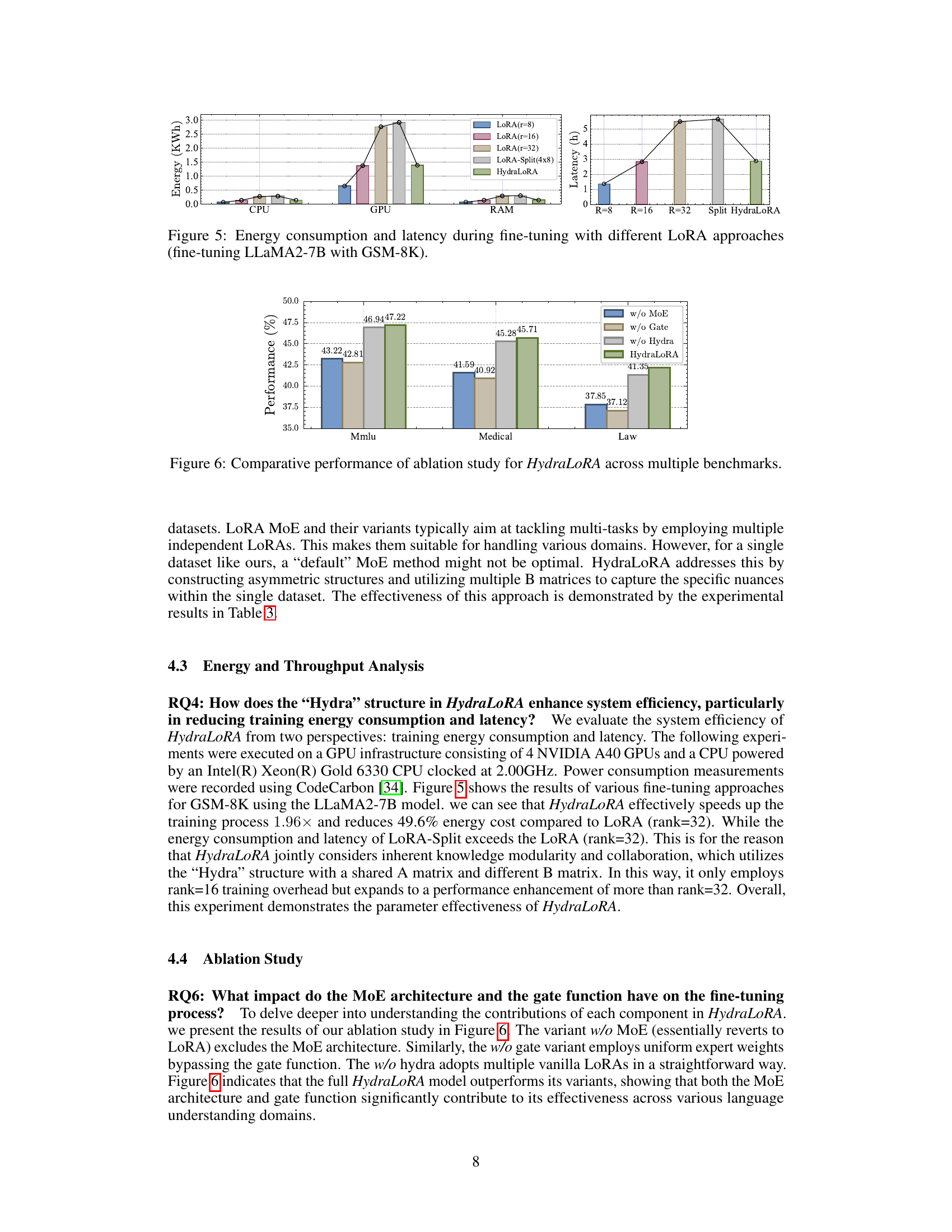

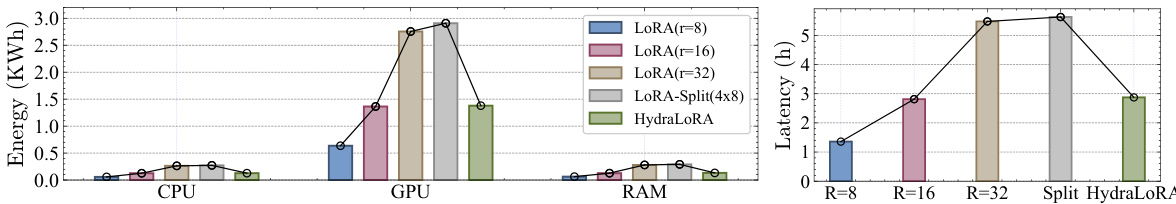

This figure compares the energy consumption (in kWh) and latency (in hours) of different LoRA approaches during the fine-tuning process of the LLaMA2-7B model on the GSM-8K dataset. The energy consumption is broken down by CPU, GPU, and RAM usage. The latency is shown as a single value for each approach. The different LoRA approaches compared include LoRA with ranks 8, 16, and 32, LoRA-Split (4x8), and HydraLoRA.

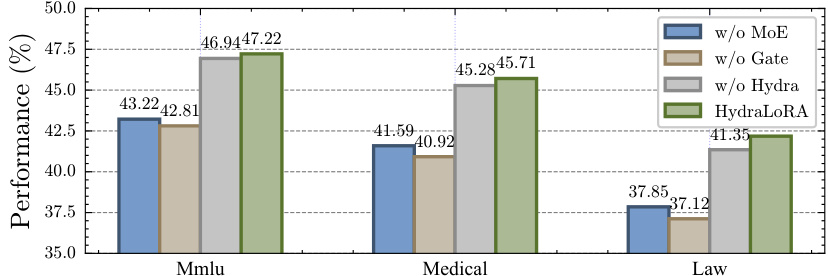

The figure displays the performance comparison of HydraLoRA with ablation studies across three benchmarks: Mmlu, Medical, and Law. It shows the performance drop when removing the MoE architecture, the gating mechanism, and the Hydra architecture itself, demonstrating the contribution of each component to the overall performance of HydraLoRA.

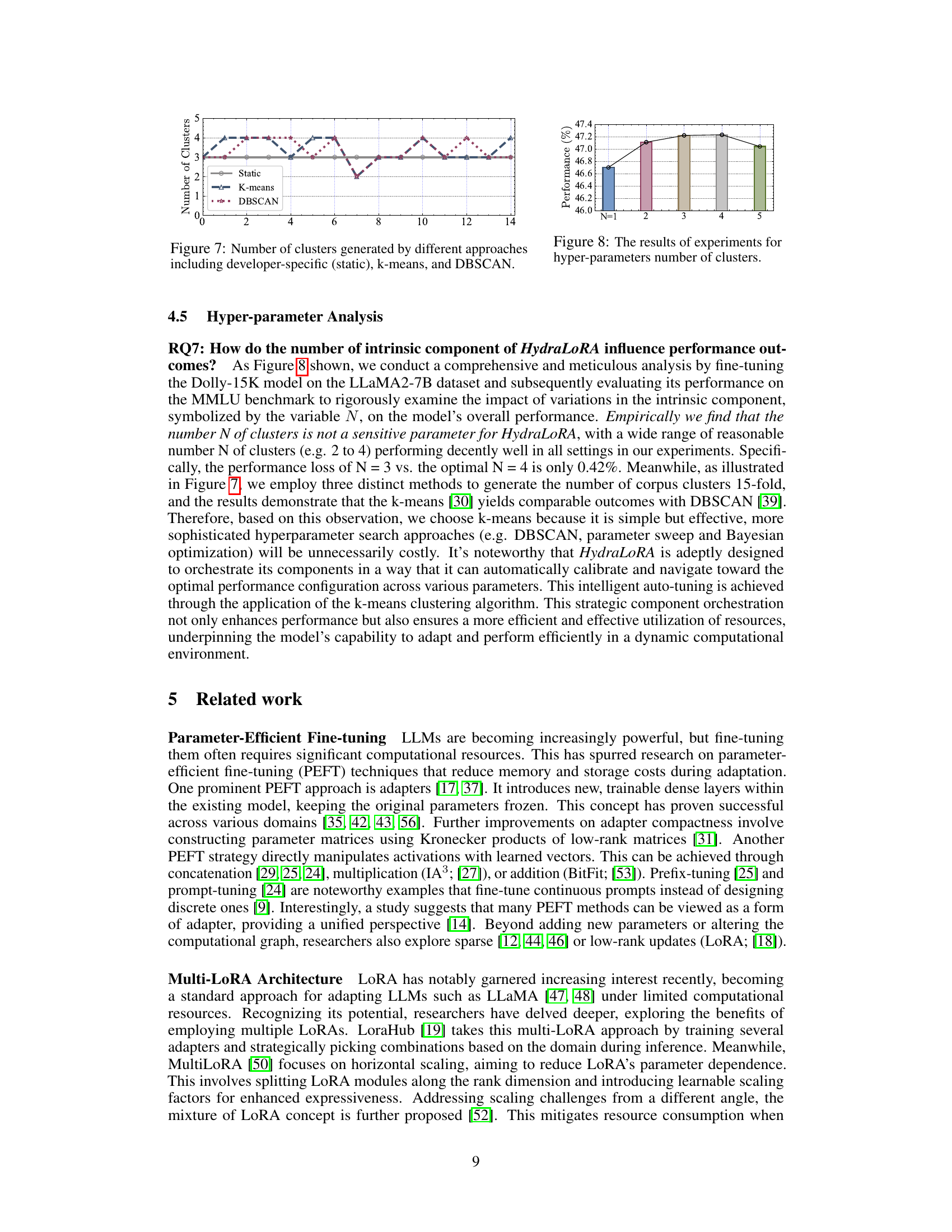

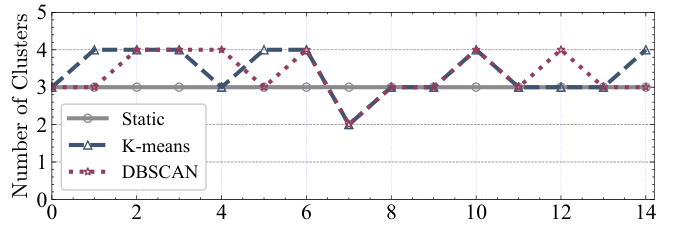

This figure shows the number of clusters identified by three different methods: a statically defined number of clusters (Static), the k-means clustering algorithm (K-means), and the DBSCAN density-based clustering algorithm (DBSCAN). The x-axis represents the trial number, while the y-axis shows the number of clusters identified in each trial. The figure illustrates the variation in the number of clusters identified by each method across multiple trials, highlighting the different behavior and sensitivity of each algorithm to data characteristics and variations across trials.

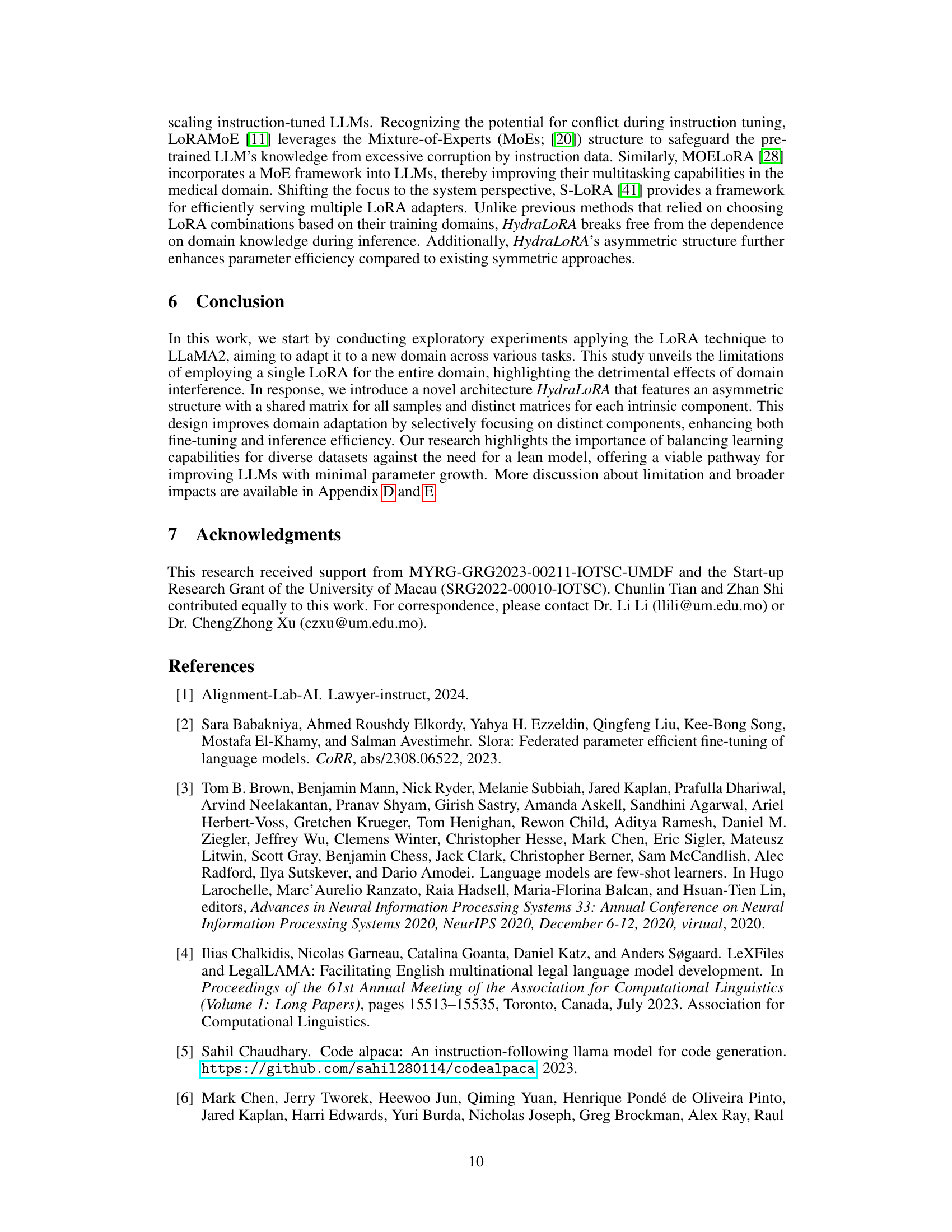

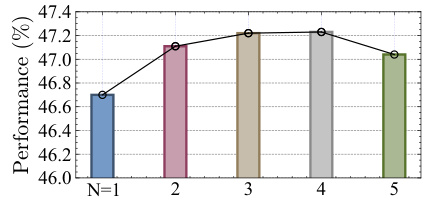

This figure shows the performance of HydraLoRA on the MMLU benchmark with different numbers of clusters (N) generated by k-means. The x-axis represents the number of clusters (N), ranging from 1 to 5. The y-axis shows the model’s performance, measured as a percentage. The figure demonstrates that the performance of HydraLoRA is relatively insensitive to the number of clusters within a reasonable range, with only a small performance drop when using 5 clusters compared to the optimal number of clusters (3 or 4).

This figure presents a t-SNE visualization of the parameters of LoRA modules fine-tuned on three different subtasks of the Dolly-15K dataset. It shows that the parameters of matrix A are similar across different tasks, while the parameters of matrix B are distinct. This observation supports the hypothesis that matrix A captures commonalities across tasks, while matrix B adapts to task-specific diversities.

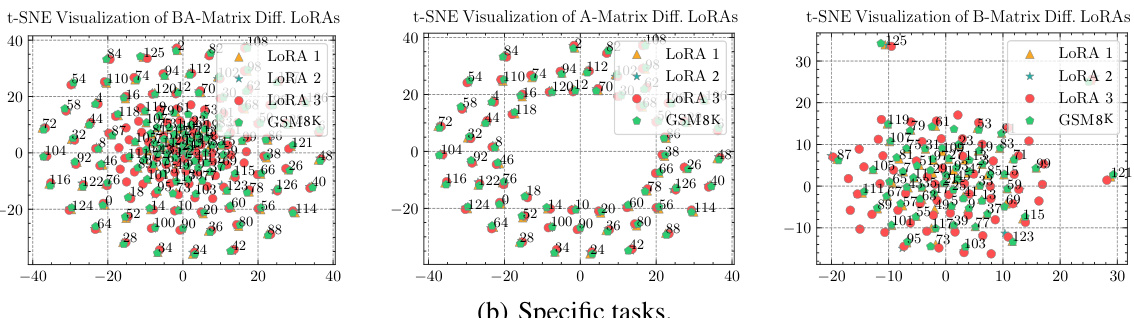

This figure presents a breakdown analysis of LoRA modules using t-SNE visualization. It compares fine-tuned LoRA modules trained on the full GSM8K dataset and its three subsets, each fine-tuned with a different LoRA. The visualization highlights the differences in the A and B matrices across different tasks, showing that the variations primarily stem from the B matrices. This observation supports the paper’s hypothesis that a shared A matrix and multiple B matrices are more effective for efficient fine-tuning.

More on tables

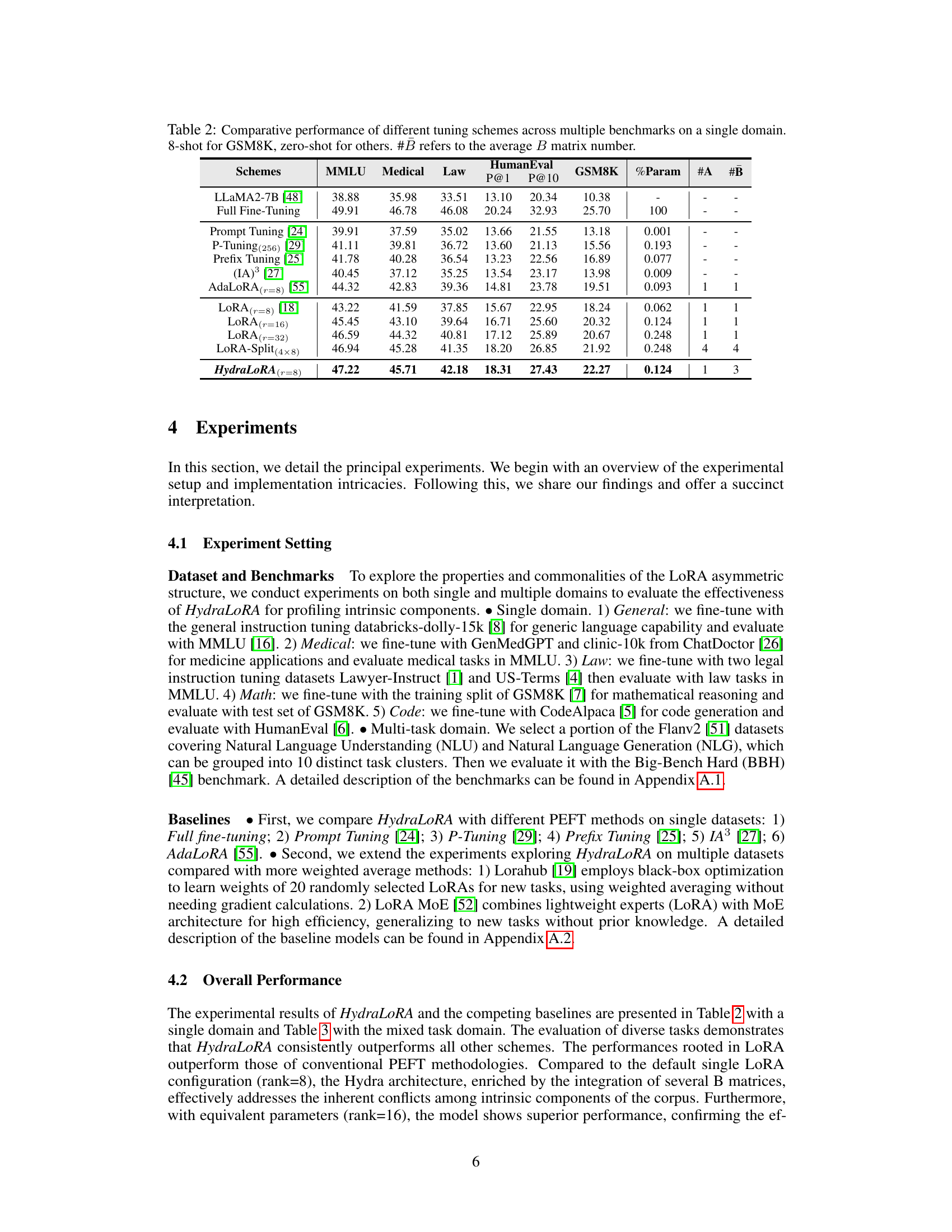

This table compares the performance of several parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods and full fine-tuning on a single domain across various benchmarks (MMLU, Medical, Law, HumanEval, GSM8K). It shows the performance improvements achieved by different approaches (LoRA, AdaLoRA, HydraLoRA, etc.) in terms of percentage parameter usage, the number of A and B matrices, and the performance on each benchmark. Note that some benchmarks used 8-shot learning while others used zero-shot learning.

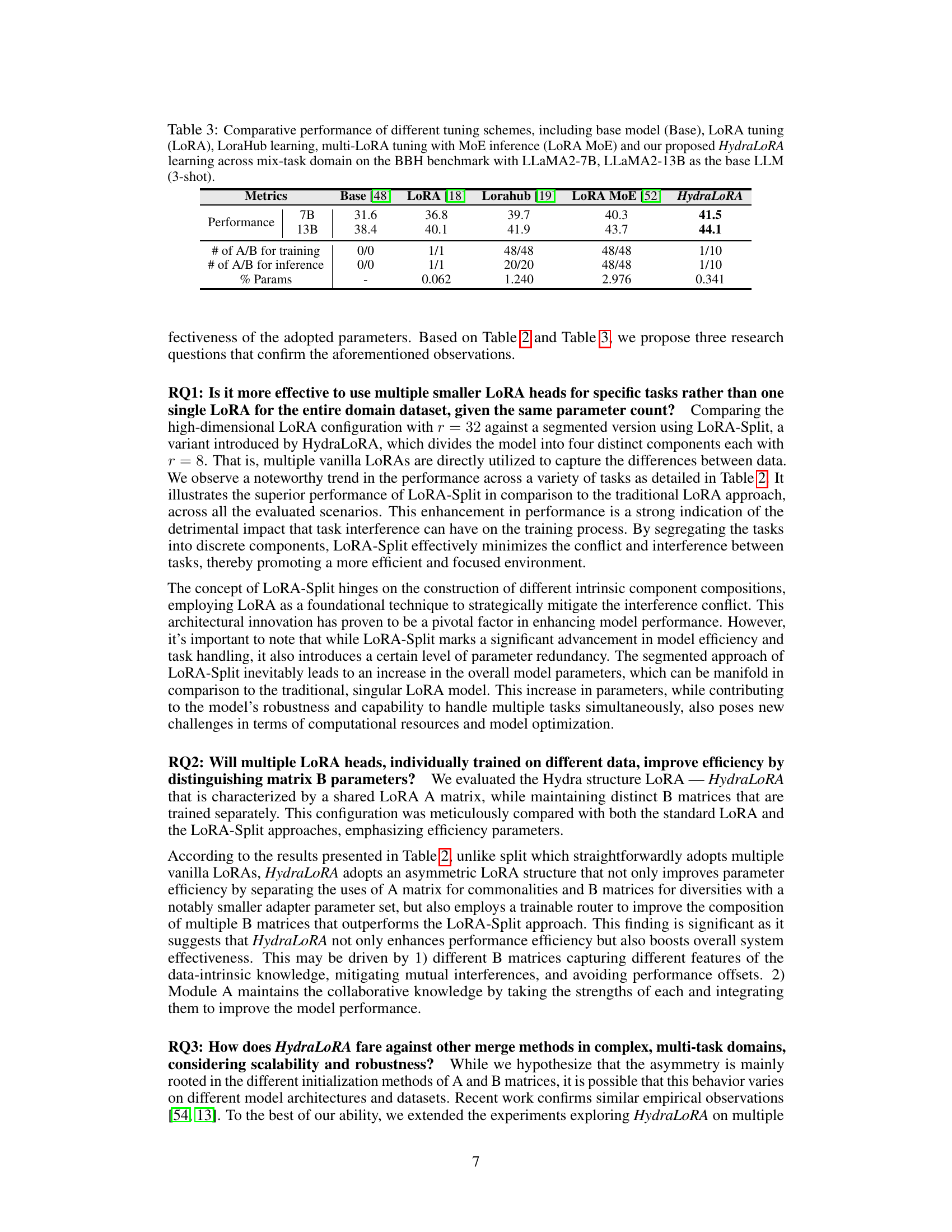

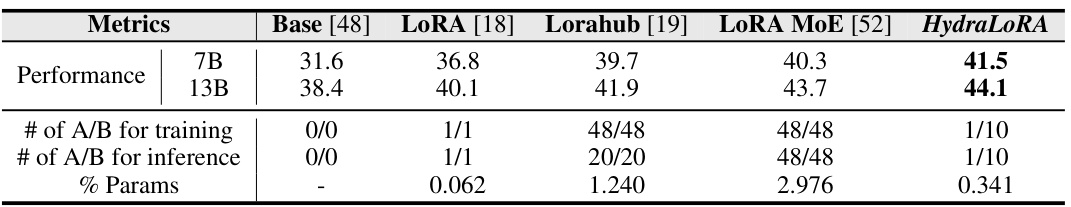

This table compares the performance of several parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods, including HydraLoRA, across multiple tasks on a mixed-domain benchmark (BBH). It evaluates performance using the base LLMs LLaMA2-7B and LLaMA2-13B with 3-shot settings. The metrics include overall performance, the number of A and B matrices used during training and inference, and the percentage of parameters tuned.

This table compares the performance of HydraLoRA against other parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods and full fine-tuning on several downstream tasks within a single domain. The metrics evaluated include performance on the MMLU, Medical, Law, and HumanEval benchmarks, as well as P@1 and P@10 on GSM8K. The number of trainable parameters (#Params) for each method is also shown, along with the number of A and B matrices used in HydraLoRA.

Full paper#