↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Quadratic computation complexity of softmax attention in Transformers limits its application to long sequences. Researchers have explored linear alternatives, but optimal design remained unclear. Existing models like LinFormer, SSM, and LinRNN exhibit suboptimal performance, raising the need for a unified theoretical understanding and improved design.

MetaLA is proposed as a unified optimal linear attention approximation, satisfying three crucial design conditions: dynamic memory, static approximation, and least parameter usage. Empirical results across diverse tasks (MQAR, language modeling, image classification, LRA) demonstrate MetaLA’s effectiveness over existing linear models. The work also addresses open questions about improving linear attention and potential capacity limits.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on efficient attention mechanisms in Transformers. It unifies existing linear attention models, providing a theoretical framework for optimal design. This opens avenues for developing more efficient and effective attention mechanisms, improving model performance and reducing computational costs in various NLP and computer vision tasks. The proposed MetaLA offers a practical solution that outperforms current state-of-the-art linear models.

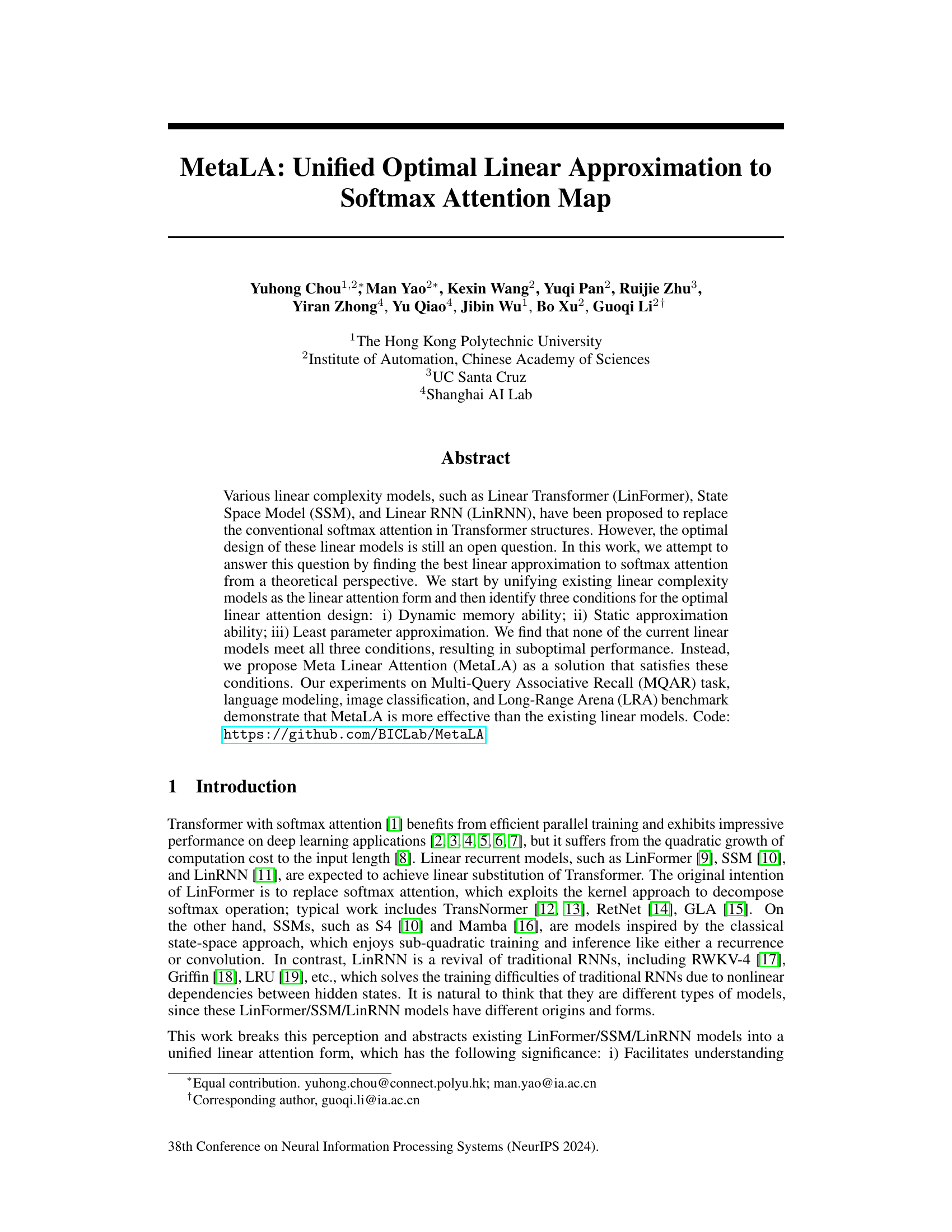

Visual Insights#

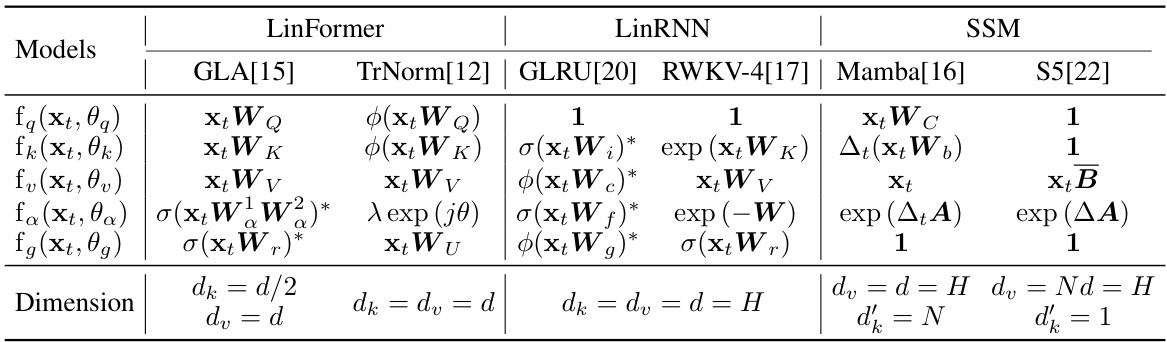

This figure shows the unified model of LinFormer, SSM, and LinRNN. It highlights that these seemingly different models share a common underlying structure, differing mainly in how they maintain the hidden state and the specific functions used for query, key, and value mappings. The figure illustrates both parallel and recurrent computation modes, showcasing the flexibility and efficiency of the unified model.

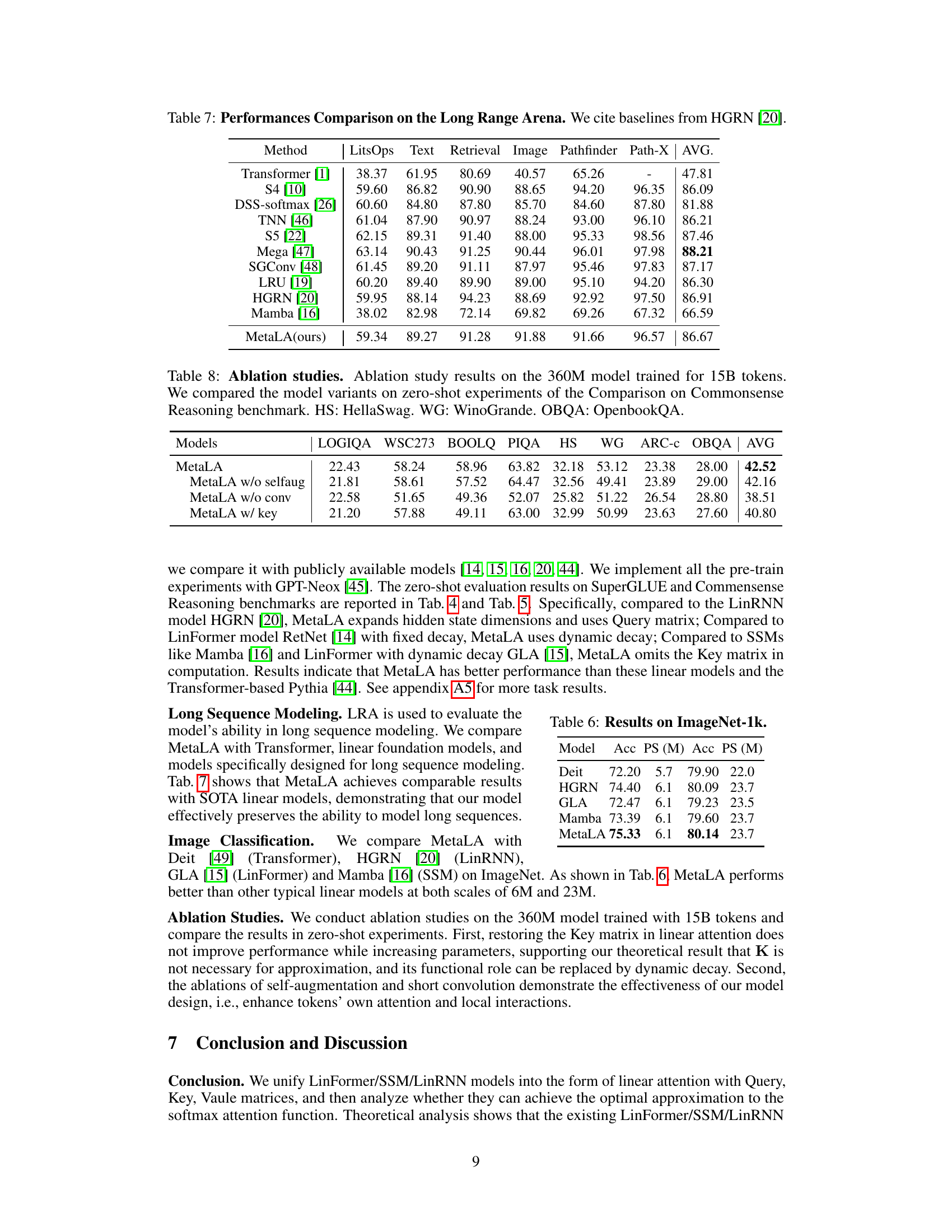

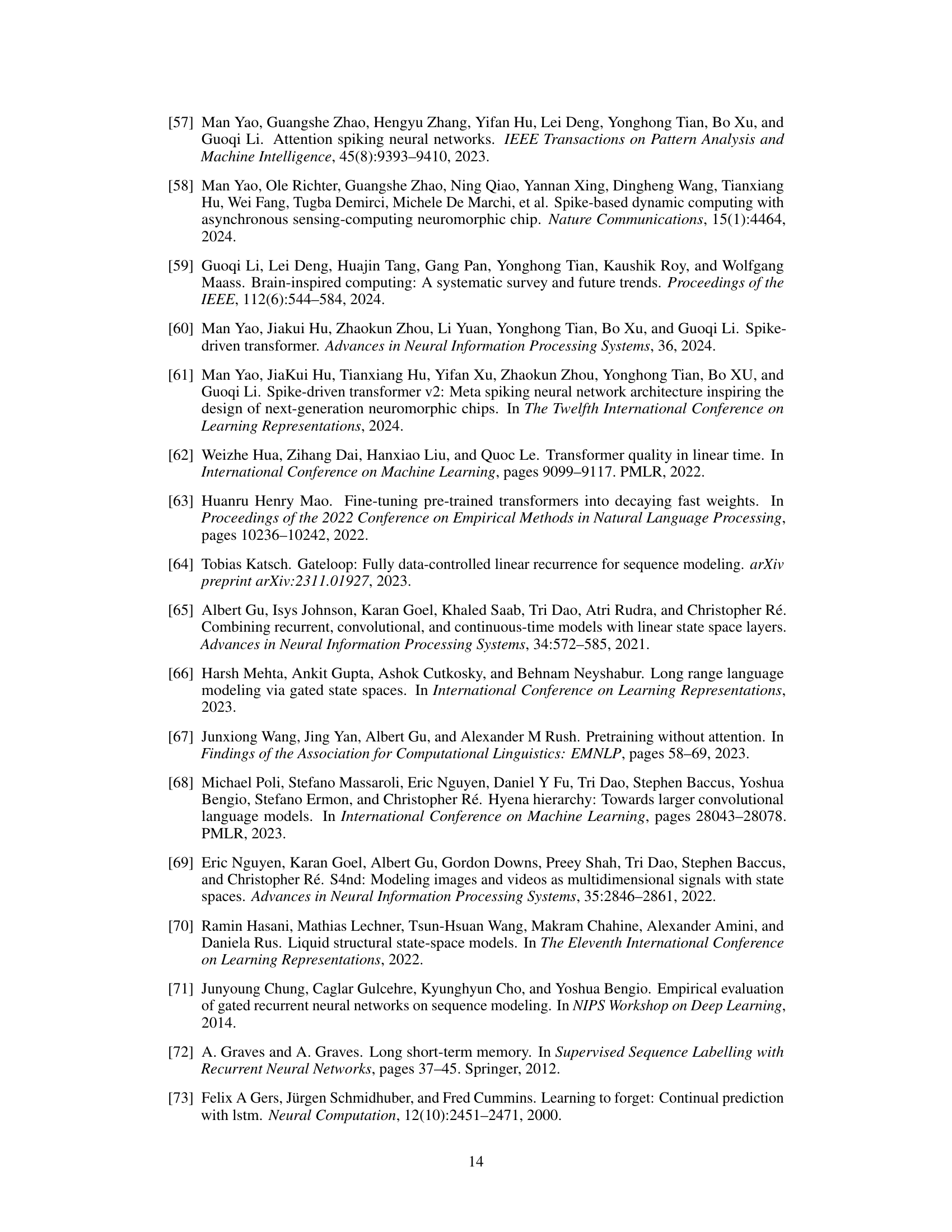

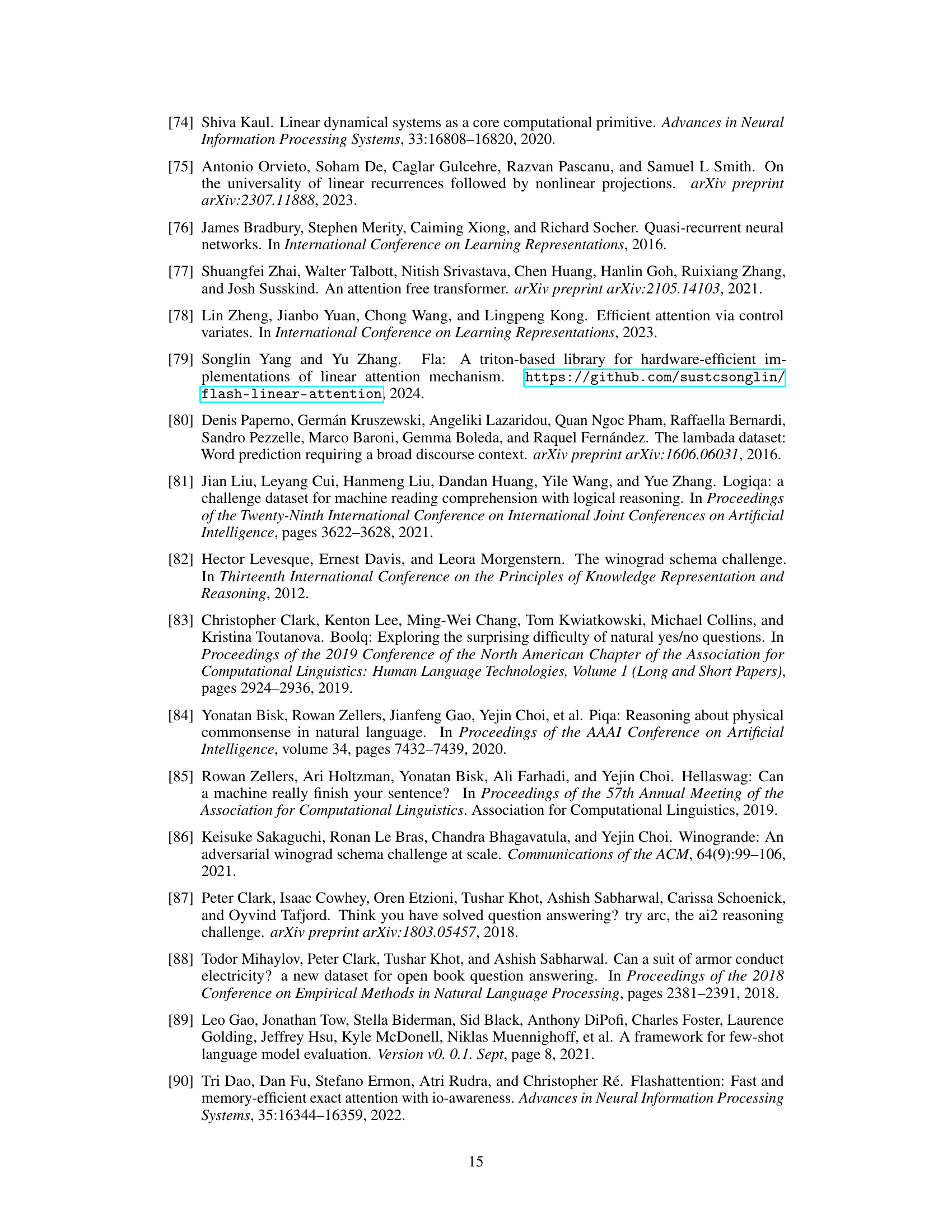

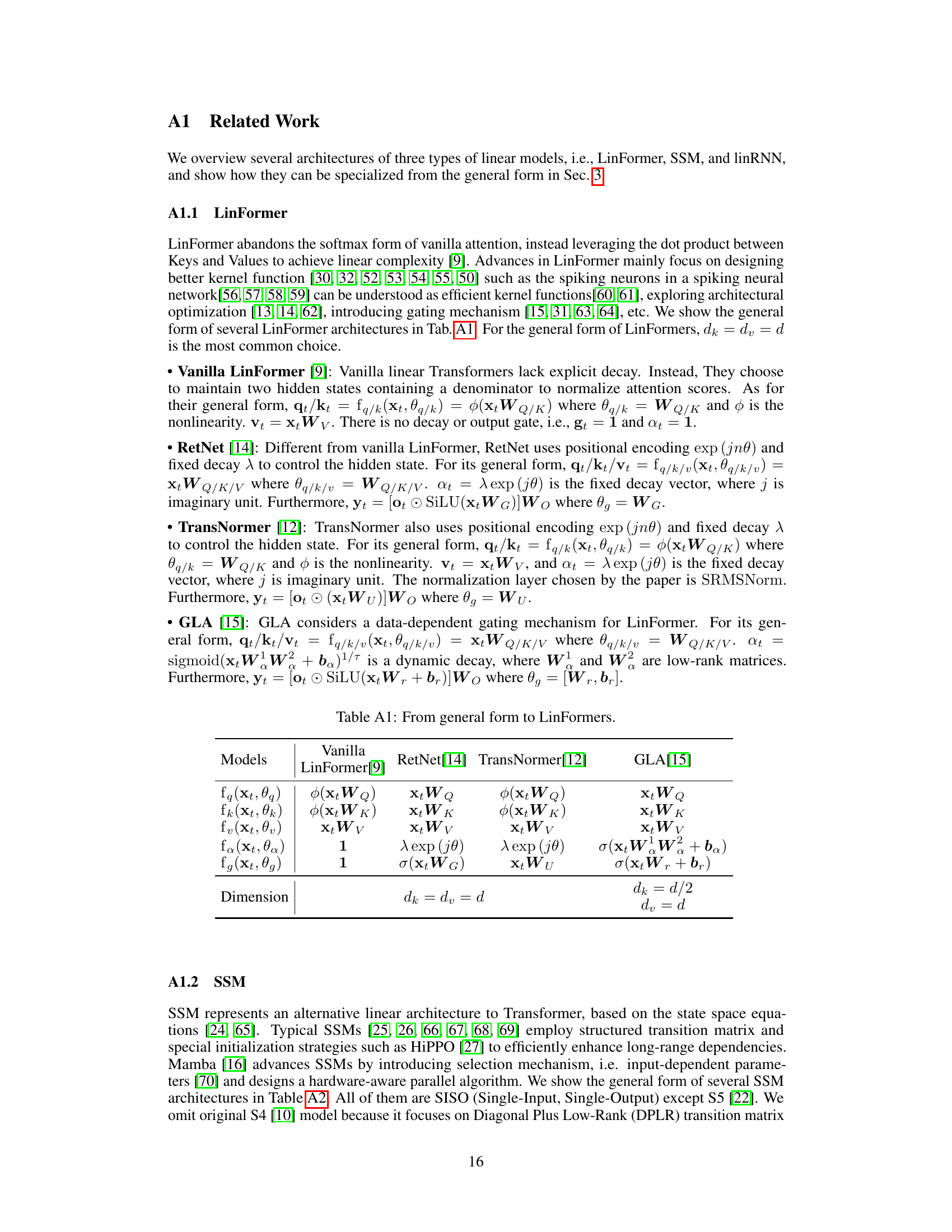

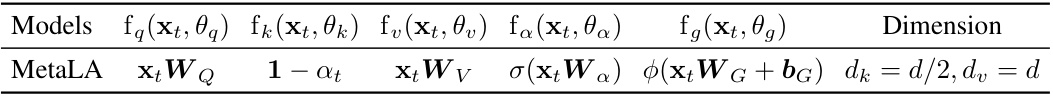

This table demonstrates how existing linear attention models (LinFormer, SSM, and LinRNN) can be derived from a unified general form. It shows the functions used for query (fq), key (fk), value (fv), decay (fa), and output gate (fg), along with the dimensionality of key/query (dk), value (dv), and hidden state (H) for each model. The table highlights the key differences in parameterization and hidden state representation across these model types.

In-depth insights#

Linear Attention Forms#

Linear attention mechanisms offer a compelling alternative to traditional softmax attention, addressing its quadratic complexity. Three prominent approaches—LinFormer, State-Space Models (SSMs), and Linear RNNs—each employ distinct strategies to achieve linear time complexity. LinFormers leverage kernel methods to approximate softmax attention. SSMs utilize state-space representations to model sequences efficiently, while Linear RNNs simplify recurrent architectures to reduce computation. A key insight is that these seemingly disparate methods share underlying similarities, suggesting a potential unified framework. By abstracting away specific implementation details, a generalized linear attention form can be formulated, highlighting the core components (Query, Key, Value) and their interactions. This unification facilitates a more systematic analysis and comparison of existing models, enabling the identification of optimal design principles and informing the creation of novel, more efficient architectures. Future research could focus on exploring this unified framework, potentially revealing new design choices and optimizing existing methods for superior performance.

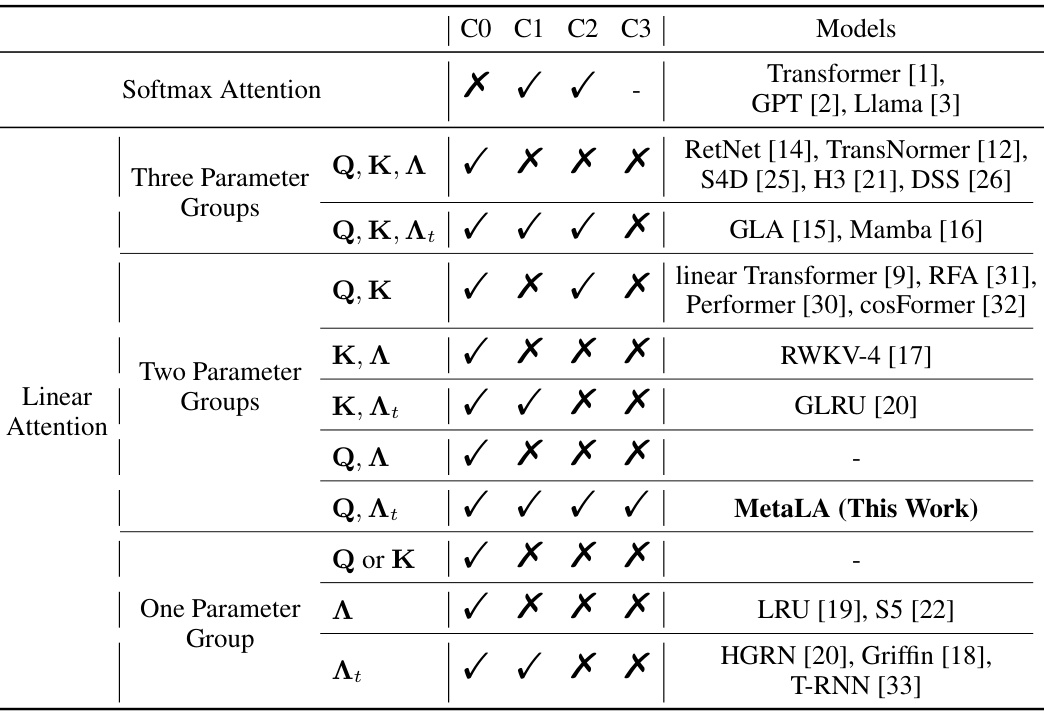

Optimal Approximation#

The core of the “Optimal Approximation” section lies in formally defining the conditions for a linear attention mechanism to optimally approximate softmax attention. This involves establishing criteria for dynamic memory ability (adaptively storing and forgetting information), static approximation ability (modeling any softmax attention map), and least parameter approximation (minimizing parameters while satisfying the previous conditions). The authors critically analyze existing linear attention models (LinFormer, SSM, LinRNN) against these criteria, highlighting their shortcomings and demonstrating that none fully achieve optimality. This rigorous framework unifies seemingly disparate linear models, paving the way for a principled approach to future linear attention design. The theoretical analysis provides a crucial foundation for the proposed MetaLA, which satisfies all three defined criteria, and serves as a significant contribution toward a deeper understanding of the optimal balance between computational efficiency and representational power in attention mechanisms.

MetaLA: Design & Tests#

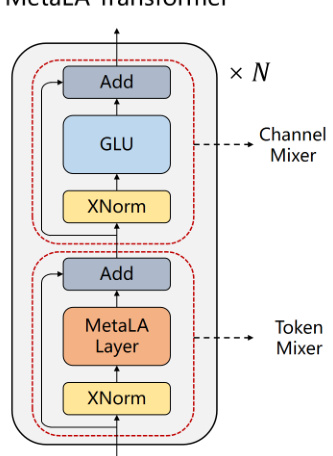

A hypothetical research paper section, ‘MetaLA: Design & Tests’, would delve into the architecture and empirical evaluation of the MetaLA model. The design aspect would detail MetaLA’s core components, focusing on its unified linear attention mechanism and how it addresses the quadratic complexity of softmax attention. This would likely involve a comparison with existing linear attention models, highlighting MetaLA’s novel features like the omission of key matrices, self-augmentation techniques, and short convolutions. The testing methodology would describe the datasets used (e.g., language modeling benchmarks, image classification datasets), the evaluation metrics (e.g., accuracy, perplexity), and the experimental setup. The results section would present the model’s performance, potentially comparing it against various baselines and analyzing the impact of its architectural choices. Ablation studies investigating the effect of individual components on the overall performance would likely be included. Finally, the section would interpret the results, offering insights into the strengths and weaknesses of the MetaLA model, along with potential avenues for future improvement.

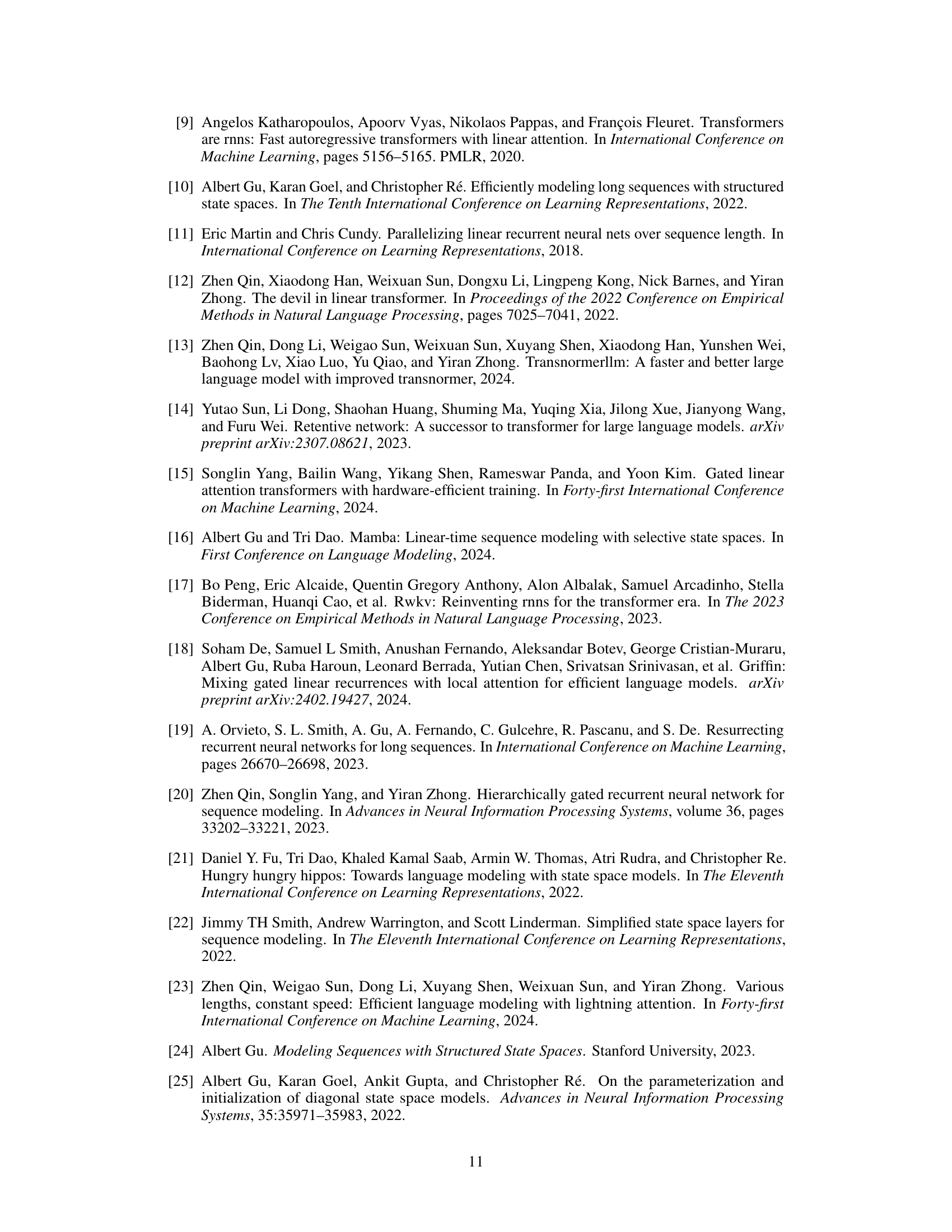

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In this context, an ablation study on MetaLA might involve removing the Query matrix, self-augmentation, short convolutions, or the dynamic decay mechanism, one at a time or in combination. By evaluating performance after each removal, researchers gain insights into which components are essential and how they interact to achieve the model’s overall performance. For example, if removing the Query matrix significantly degrades performance, it would highlight its crucial role in selective attention. Similarly, diminishing returns after removing self-augmentation would indicate its effectiveness in mitigating attention dilution. These controlled experiments provide a more granular understanding of the model’s strengths and weaknesses. The findings directly inform design choices for future iterations, suggesting which components to prioritize and how to better optimize the model for efficiency and efficacy. Such analysis provides not only quantitative results but also valuable qualitative insights into MetaLA’s architecture. Therefore, ablation studies are critical for justifying design choices and enhancing the overall trustworthiness of the proposed MetaLA model.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this paper on MetaLA could explore several promising avenues. Improving the approximation of softmax attention is a key area, potentially through advanced techniques in kernel design or by developing more sophisticated gating mechanisms. Investigating the capacity limits of linear attention, especially regarding its ability to match or surpass the performance of softmax attention on specific tasks, requires further analysis. The research also indicates the need to better understand the interactions between dynamic memory, approximation ability, and parameter efficiency. Exploring these relationships could lead to the development of even more efficient and powerful linear attention mechanisms. Finally, applying MetaLA to a broader range of tasks and evaluating its performance against various state-of-the-art models is crucial for establishing its true potential and identifying any limitations or areas requiring further refinement.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the recurrent form of the MetaLA (Meta Linear Attention) model. The diagram illustrates the flow of information through the model, highlighting three key enhancements made to improve performance: (1) Removal of unnecessary Key matrices, (2) Self-augmentation to enhance a token’s attention to itself (avoiding attention dilution), and (3) The use of short convolutions to improve local interactions. These three key enhancements are marked in red in the diagram. The diagram shows the input (xt), the hidden state (St-1), the updated hidden state (St), the output (yt), and several intermediate components involved in calculations for Query (qt), Value (vt), decay (αt), output gate (gt), and augmented output (ot).

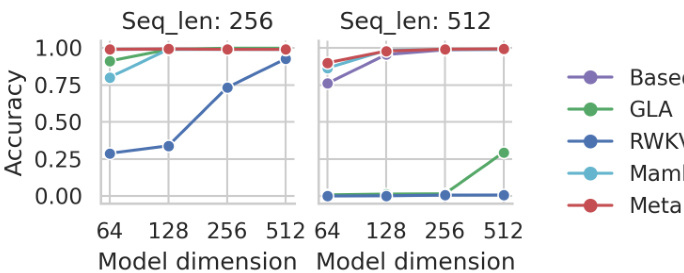

This figure shows the accuracy achieved on a synthetic Multi-Query Associative Recall (MQAR) task, comparing MetaLA against several other linear attention models (Base, GLA, RWKV, Mamba). The results are shown for both sequence lengths of 256 and 512, and across varying model dimensions (64, 128, 256, 512). It demonstrates the relative performance of MetaLA compared to other approaches, highlighting its superior accuracy, particularly at higher model dimensions and sequence length.

This figure illustrates the general form of LinFormer, SSM, and LinRNN mechanisms, unifying their recurrent and parallel computation modes. The unified form reveals shared components, including query, key, and value matrices, despite the differences in their origins and forms. The recurrent form maintains a hidden state which is updated to maintain history information, similar to how softmax attention uses a KV cache. The parallel form computes the attention mechanism in parallel but still demonstrates a relationship to the hidden state. This unification facilitates a deeper understanding of these models and their relationship to softmax attention.

This figure illustrates the unified form of LinFormer, SSM, and LinRNN mechanisms. It shows that these seemingly different models can be represented by a common structure encompassing Query, Key, and Value matrices, along with parallel and recurrent computation modes. This unification highlights the key design differences between these linear models, mainly focusing on hidden state size and maintenance, as well as how they map parameters, and facilitates understanding their relationship to softmax attention.

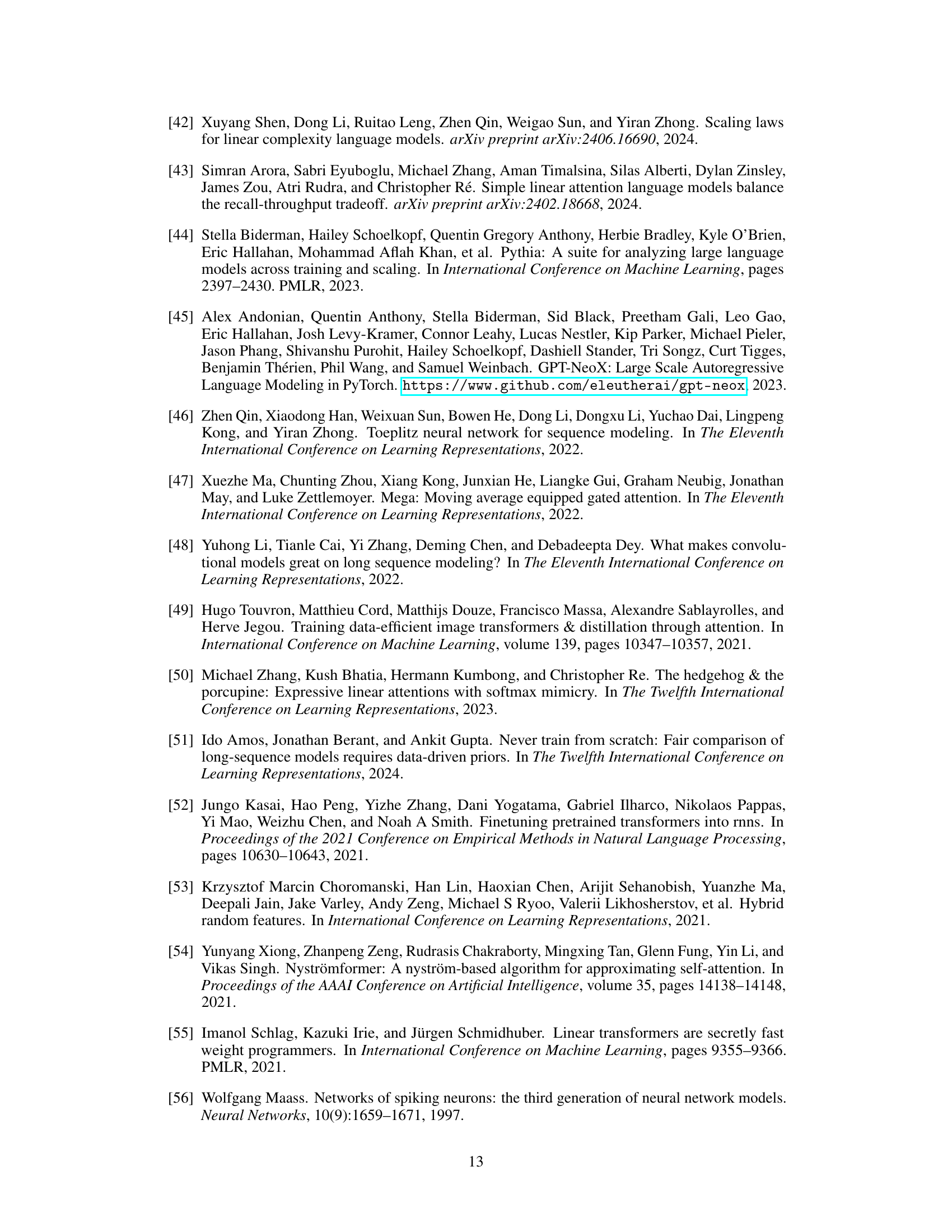

More on tables

This table summarizes the capabilities of existing linear models in terms of satisfying three necessary conditions for optimal linear approximation to softmax attention: Dynamic memory ability, Static approximation ability, and Least parameter approximation. Each model is evaluated based on whether it satisfies these conditions (represented by checkmarks or crosses). The table highlights the deficiencies of existing models and motivates the proposed MetaLA model.

This table demonstrates how existing linear models (LinFormer, SSM, LinRNN) can be derived from the unified linear attention form proposed in the paper. It shows the specific functions used for Query (fq), Key (fk), Value (fv), decay (fa), and output gate (fg) for each model, as well as the dimensions (dk, dv, d) used. The table highlights the key differences between these linear models in terms of parameter functions and hidden state sizes.

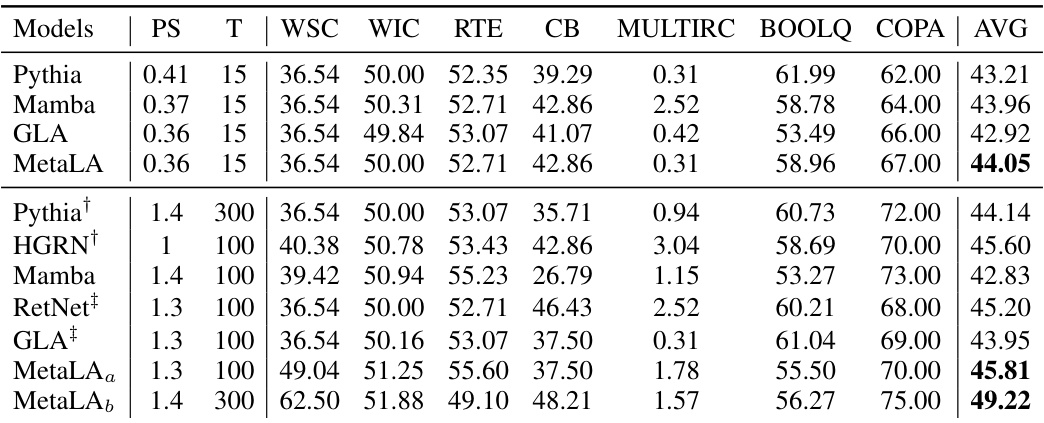

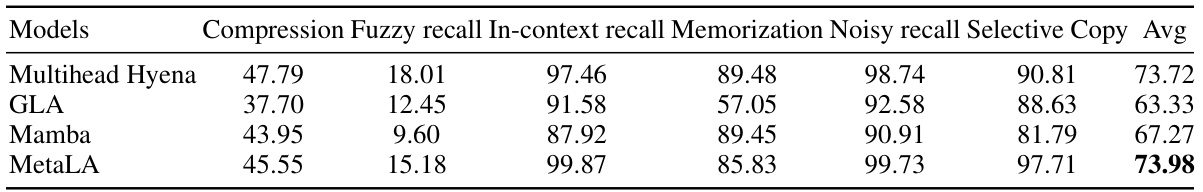

This table compares the performance of MetaLA and other models on the SuperGLUE benchmark. It shows parameter size, number of tokens used for training, and accuracy scores across multiple tasks. Note that some baselines were retrained for fair comparison with MetaLA.

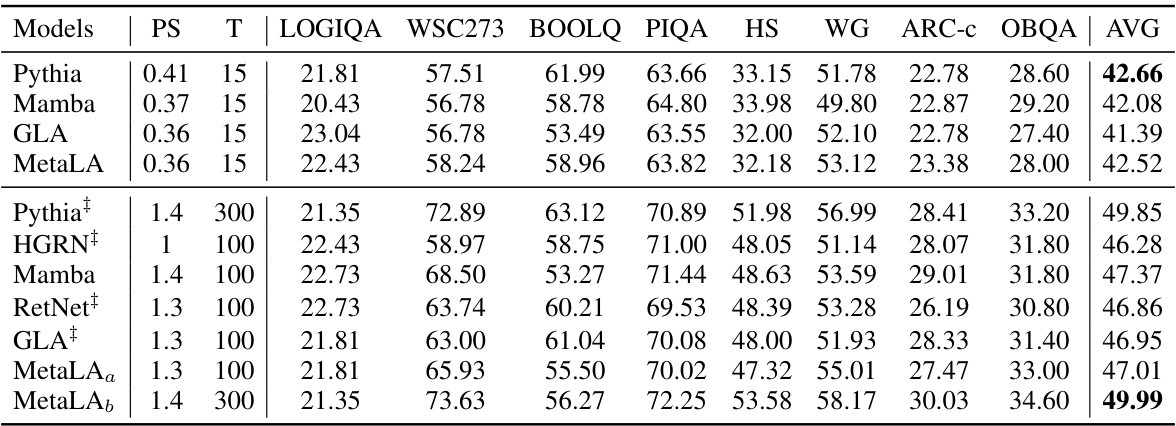

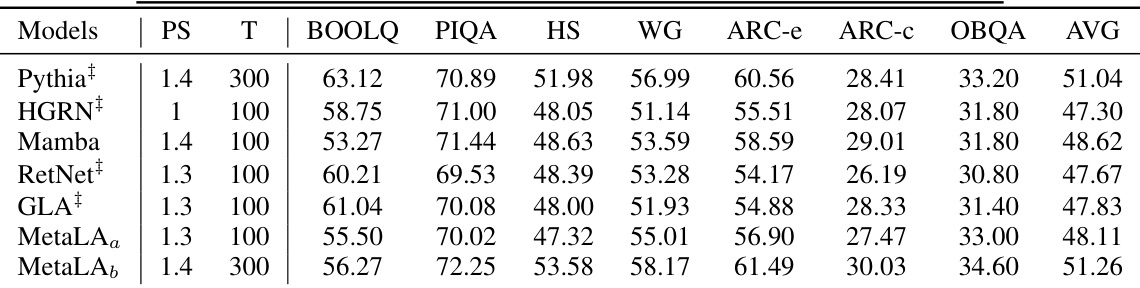

This table compares the performance of different language models on commonsense reasoning tasks. The models are evaluated on several benchmarks, including LOGIQA, WSC273, BOOLQ, PIQA, HellaSwag, Winogrande, ARC-c, and OpenbookQA. The table shows the performance of each model in terms of accuracy or F1 score, depending on the specific benchmark. Some models used open-source checkpoints for testing.

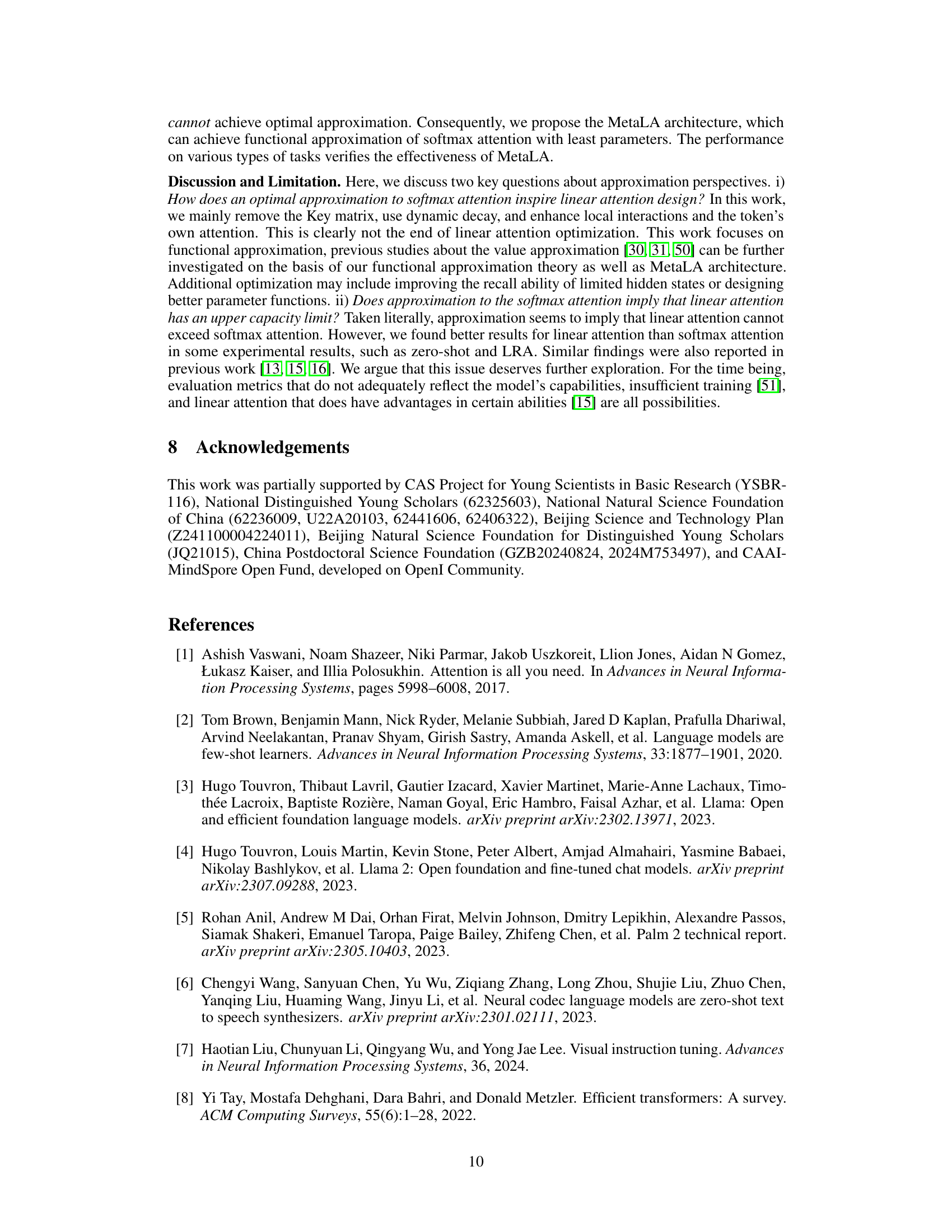

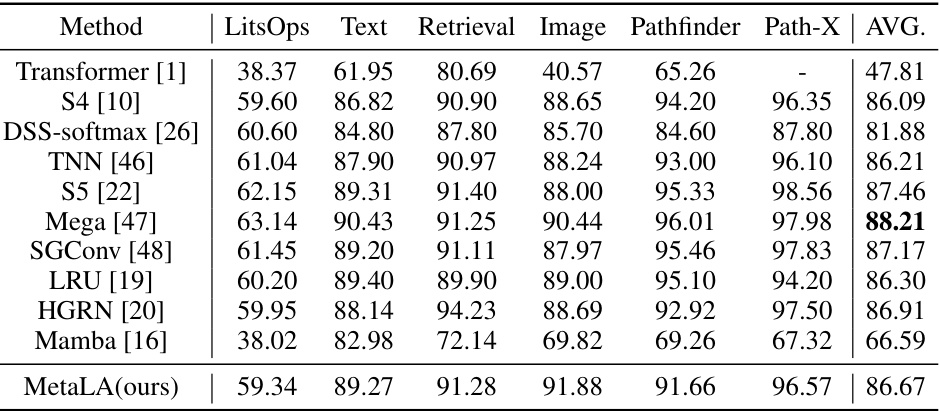

This table compares the performance of MetaLA and other state-of-the-art models on the Long Range Arena benchmark. The benchmark consists of several tasks evaluating different aspects of long-range sequence modeling capabilities, including ListOps, Text Retrieval, Image Pathfinder, and Path-X. The table shows the performance of each model on each task, as well as the average performance across all tasks. The results demonstrate MetaLA’s competitive performance compared to existing methods.

This table presents the ablation study results for the 360M MetaLA model trained on 15 billion tokens. It compares the performance of the full MetaLA model against variants where different components (self-augmentation, short convolution, and the key matrix) are removed. The results are evaluated using several zero-shot commonsense reasoning benchmarks, including HellaSwag (HS), WinoGrande (WG), and OpenbookQA (OBQA), with LOGIQA and WSC273 also included. The table helps to determine the contribution of each component to the overall model performance.

This table presents the results of image classification experiments on the ImageNet-1k dataset. It compares the performance of MetaLA against several other linear models (HGRN, GLA, Mamba) and a transformer-based model (Deit). The comparison includes accuracy and the number of model parameters (in millions). The results show that MetaLA achieves the highest accuracy among linear models.

This table shows how the general recurrent form of linear attention can be specialized to existing linear models such as LinFormer, GLA, LinRNN, TransNormer, GLRU, RWKV-4, Mamba and SSMs. It illustrates the differences in the functions used for query, key, value, decay, output gate, and dimension settings for each model. The table highlights how variations in the hidden state size and the method used to maintain that state affect the overall model design and functionality. This demonstrates that the main difference between LinFormer, SSM and LinRNN lies in hidden state size, how to maintain the hidden state, and how to perform parameter mapping.

This table shows how several State-Space Models (SSMs) can be derived from the general recurrent linear form presented earlier in the paper. It details the functions used for query, key, value, decay, and output gate for different SSM models like DSS, S4D, H3, S5, and Mamba. The table also specifies the dimensions used in each model, highlighting differences in parameterization and the usage of independent parameters across channels.

This table shows how the general recurrent form of linear attention used in the paper can be specialized to existing linear models like Linformer, GLRU, and Mamba. It highlights the differences in the functions used for query, key, value, decay, and output gate, and the dimensions used in each model. It helps to unify different linear attention models under a common framework.

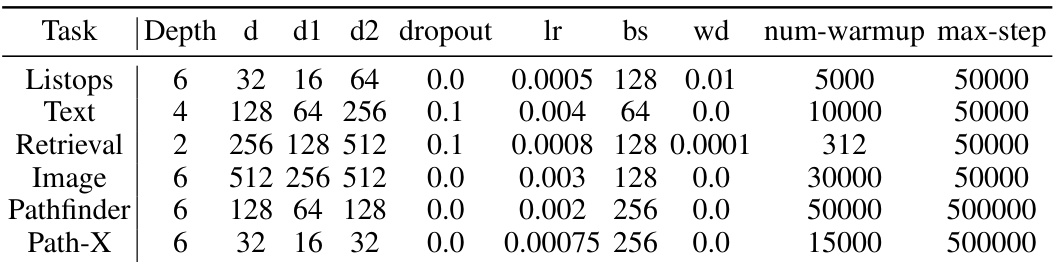

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training the MetaLA model on the Long Range Arena (LRA) benchmark. It specifies the depth of the network, the dimensions of various parameters (d, d1, d2), the dropout rate, the learning rate, batch size, weight decay, number of warmup steps, and the maximum number of training steps. These settings were tailored for optimal performance on each specific subtask of LRA.

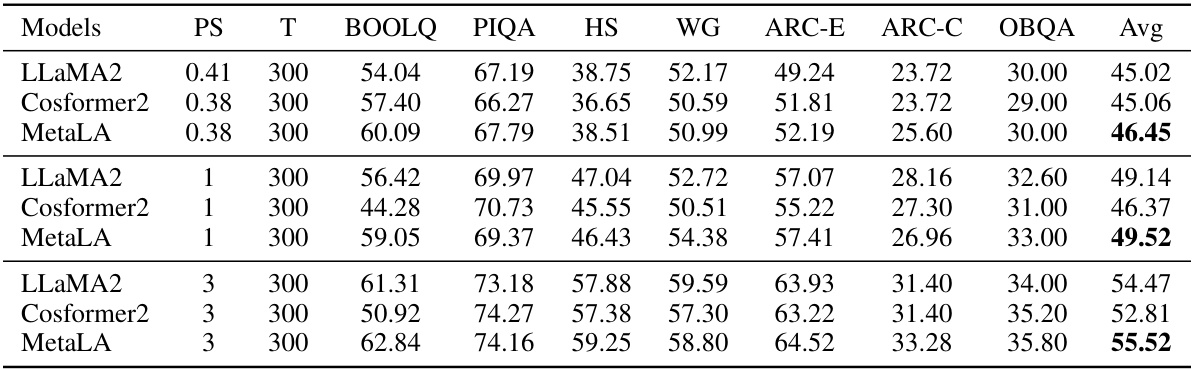

This table compares the performance of different language models on commonsense reasoning tasks. It shows the performance (in terms of accuracy or other relevant metrics) of various models, including MetaLA, on tasks such as LOGIQA, WSC273, BOOLQ, PIQA, HellaSwag, WinoGrande, ARC-c, and OpenbookQA. The table helps to demonstrate the effectiveness of MetaLA by comparing its performance against established baselines.

This table compares the performance of various language models on commonsense reasoning tasks. The models are evaluated on several benchmarks, including LOGIQA, WSC273, BOOLQ, PIQA, HellaSwag (HS), Winogrande (WG), ARC-c, and OpenbookQA (OBQA). The table shows the performance of different models in terms of accuracy or other relevant metrics on these benchmarks. The size (PS) and number of training tokens (T) of the models are also included. The ‘#’ symbol indicates whether open-source checkpoints were used for testing.

This table summarizes the capabilities of existing linear models (Linformer, SSM, LinRNN) in terms of the three criteria defined in the paper for optimal linear approximation to softmax attention: dynamic memory ability, static approximation ability, and least parameter approximation. It shows which models satisfy each criterion and highlights their deficiencies.

This table presents the results of the Multi-Query Associative Recall (MQAR) task, a synthetic benchmark designed to evaluate memory ability. The experiment uses sequences of length 512 and 80 key-value pairs. The table compares the performance of a Transformer model, the Mamba model and the MetaLA model across different model dimensions (64 and 128). It shows that the Transformer model achieves near-perfect accuracy, while Mamba performs poorly. MetaLA demonstrates improved performance compared to Mamba, indicating its effectiveness in handling longer sequences and more information.

This table presents the performance comparison of different models on the Long Range Arena benchmark. The benchmark evaluates the ability of models to handle long sequences. The models compared include various linear attention models (S4, DSS-softmax, TNN, S5, Mega, SGConv, LRU, HGRN, Mamba) and the standard Transformer model. The performance is measured across several subtasks: ListOps, Text Retrieval, Image Pathfinder, Path-X. The average performance across all subtasks is also reported, providing a comprehensive comparison of model performance in handling long-range dependencies.

This table categorizes several existing linear attention models based on three criteria for optimal linear approximation to softmax attention: dynamic memory ability, static approximation ability, and least parameter approximation. It shows which models satisfy each criterion, highlighting the shortcomings of existing methods.

Full paper#