↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models are computationally expensive, hindering their deployment on resource-constrained devices. Current efficient inference methods, like Binary Neural Networks, involve translating abstract neural network representations into executable logic, incurring a significant computational cost. Differentiable Logic Gate Networks (LGNs) learn logic gate combinations directly, optimizing inference at the hardware level. However, initial LGN approaches were limited by random connections, hindering their capability to learn spatial relations in image data.

This research extends differentiable LGNs using deep logic gate tree convolutions, logical OR pooling, and residual initializations. These additions allow LGNs to scale to much larger networks while utilizing the paradigm of convolution. Their approach demonstrates significant improvements on CIFAR-10, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy with only 61 million logic gates—a 29x reduction compared to existing methods. This work addresses the limitations of previous LGNs, paving the way for more efficient and scalable deep learning models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to building efficient and accurate deep learning models using logic gates. It offers a significant improvement in inference speed and reduced computational costs compared to traditional methods. The research opens new avenues for hardware-aware model design, particularly for resource-constrained environments like embedded systems. It also addresses the current challenges of high inference costs associated with deep learning, which is highly relevant to the field.

Visual Insights#

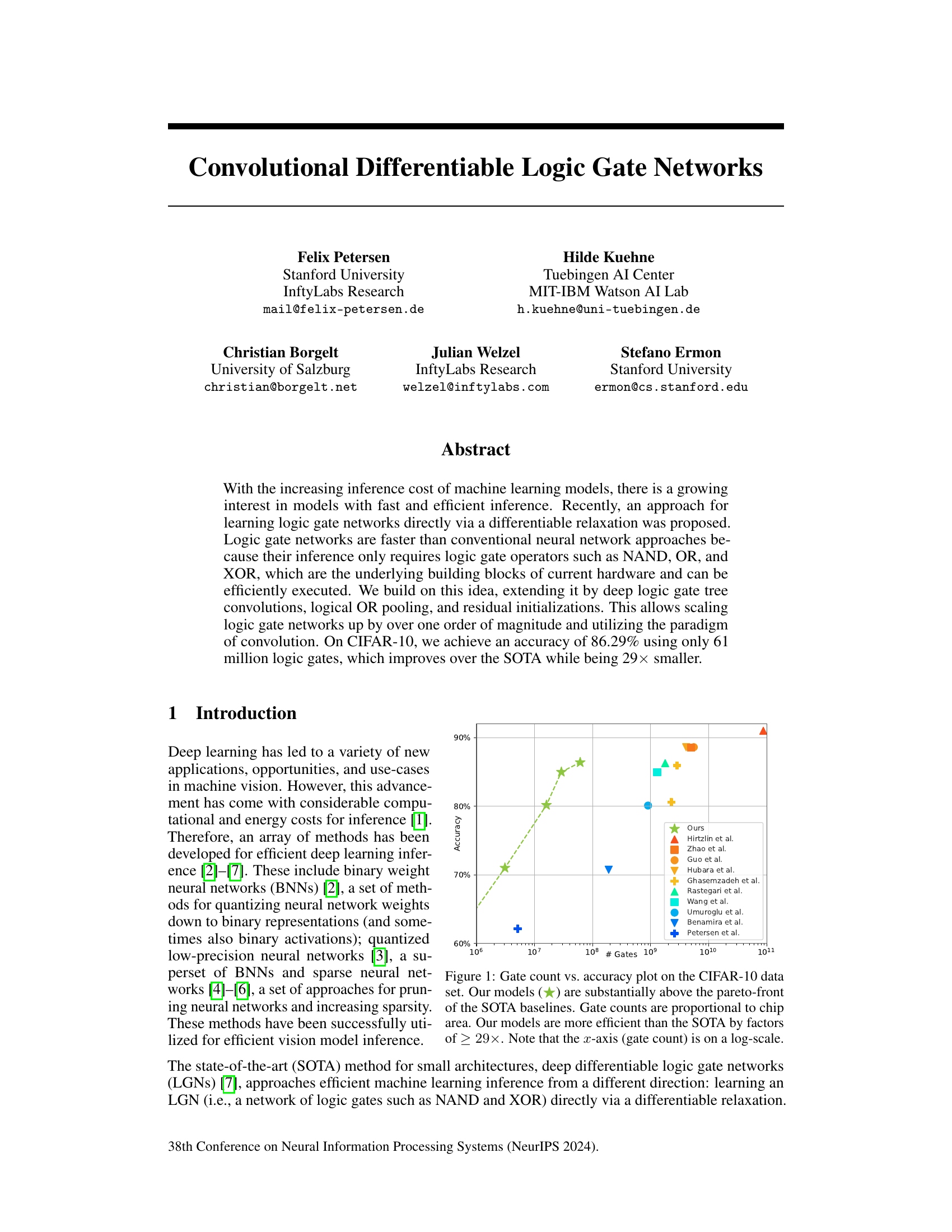

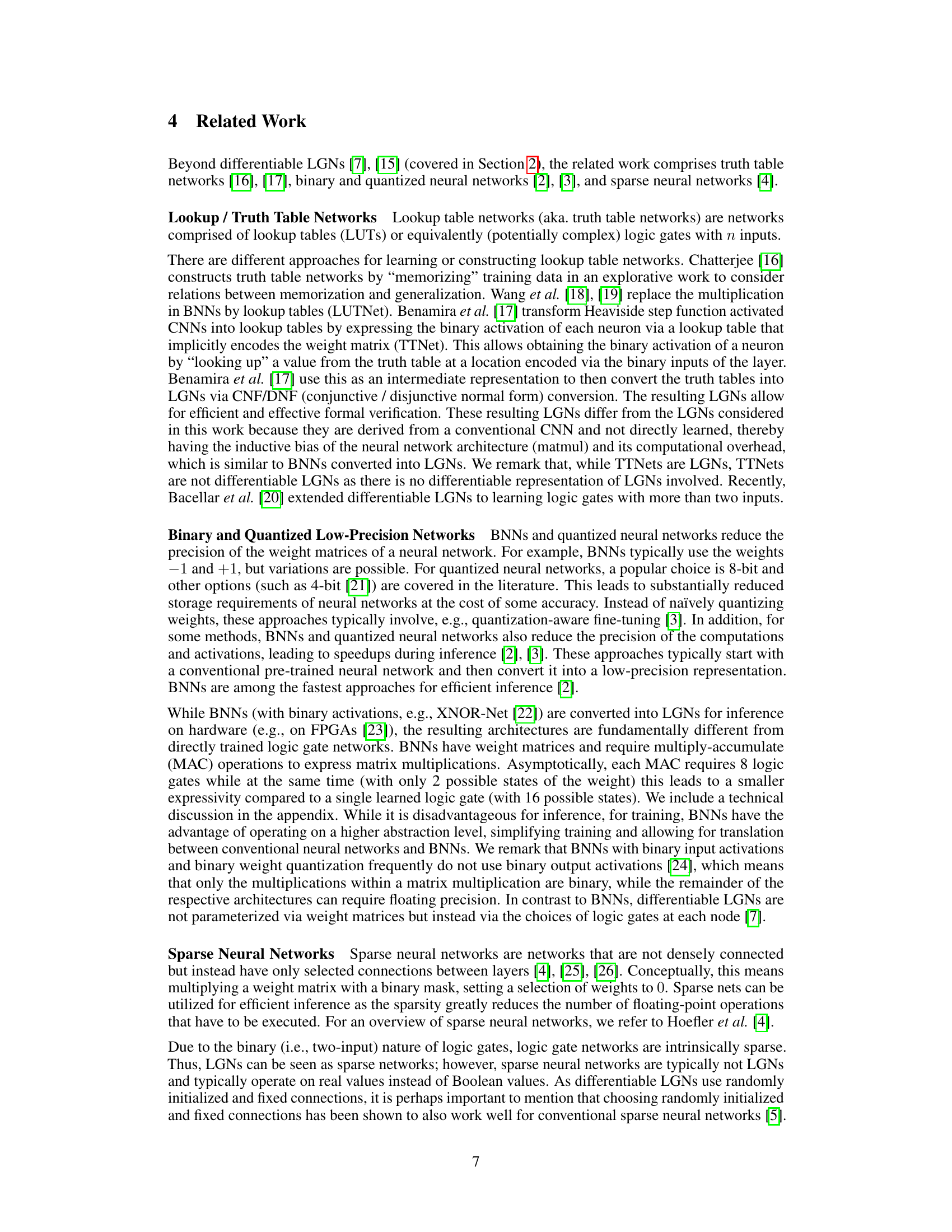

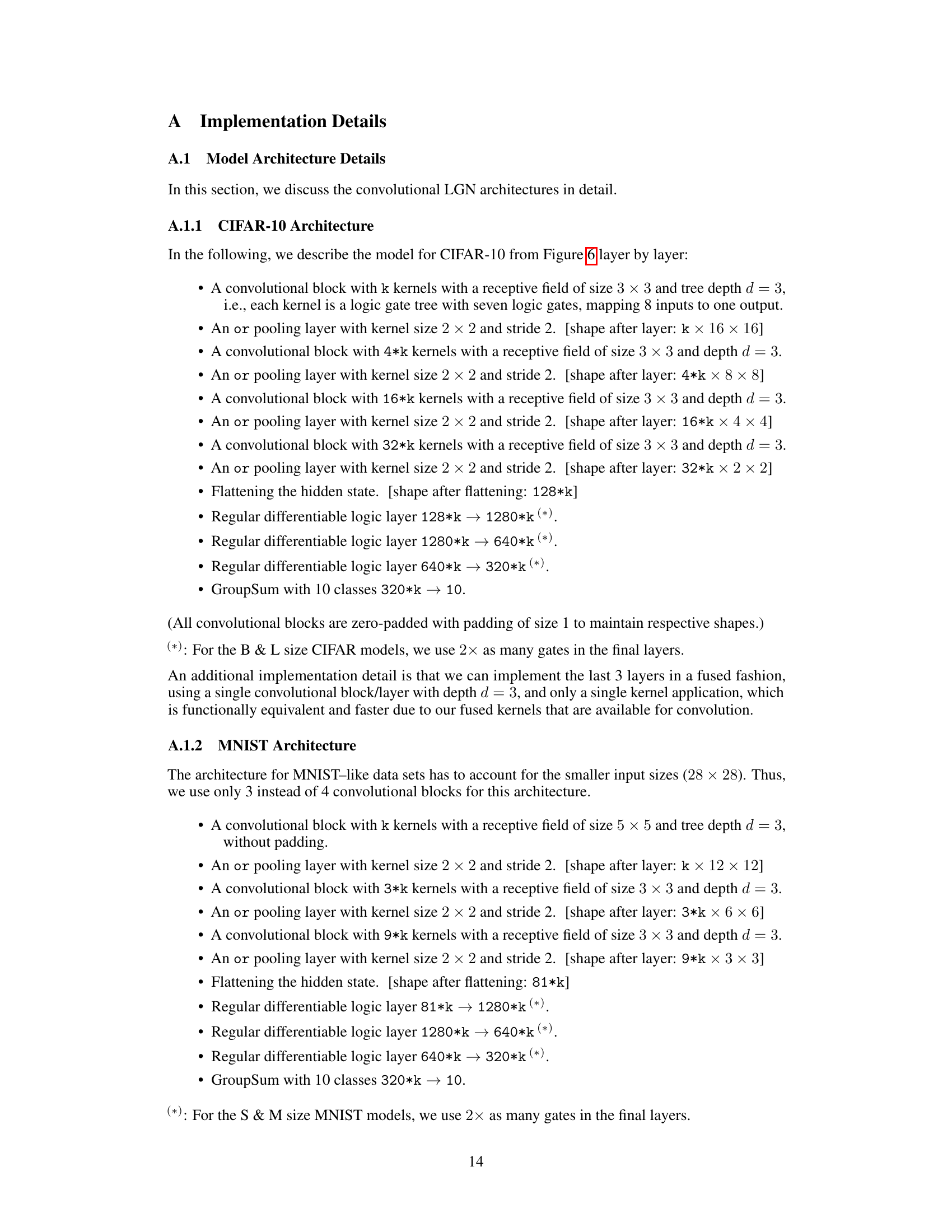

This figure shows a comparison of different neural network architectures on the CIFAR-10 dataset, plotting accuracy against the number of logic gates used. The authors’ models significantly outperform existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) models in terms of efficiency (fewer gates for higher accuracy). The x-axis uses a logarithmic scale to accommodate the wide range of gate counts.

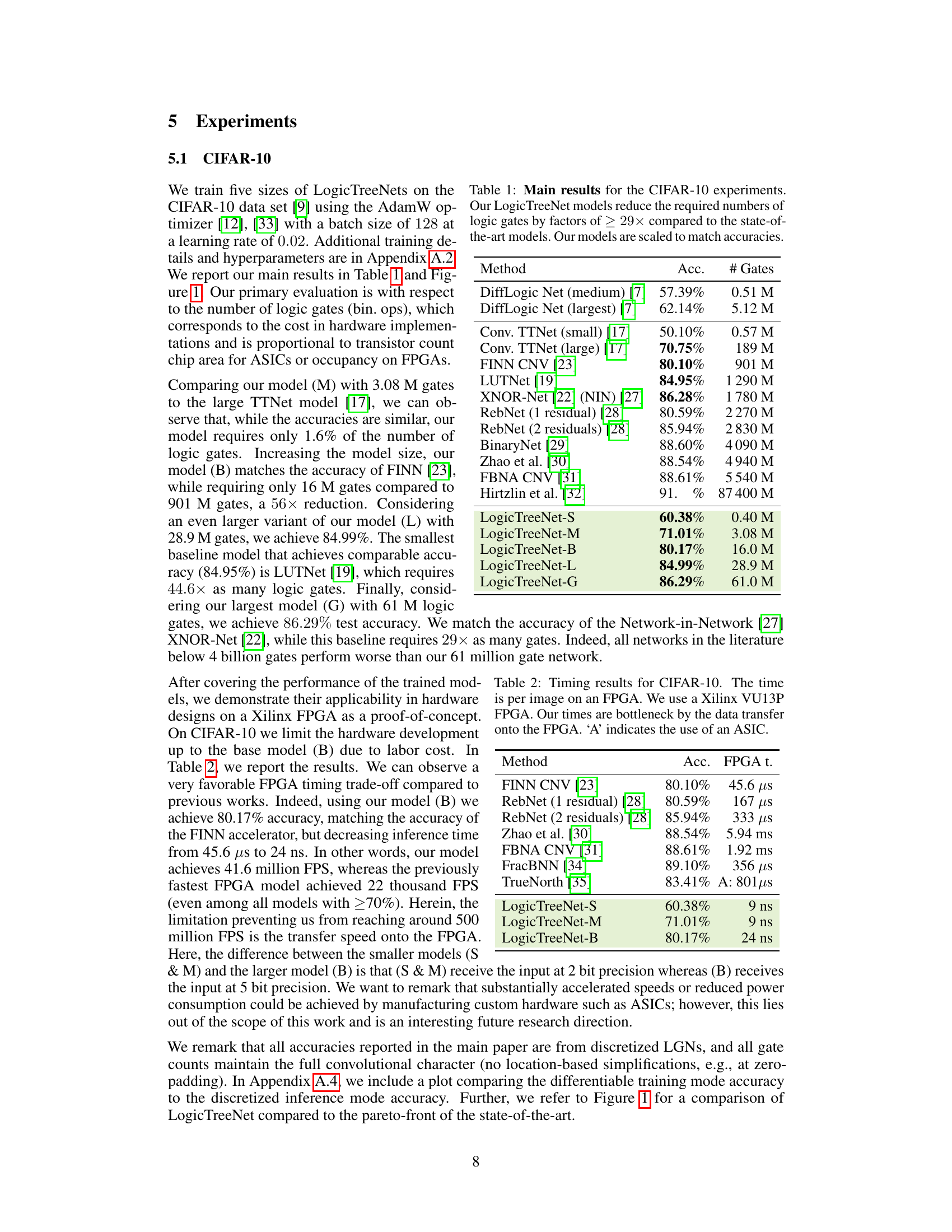

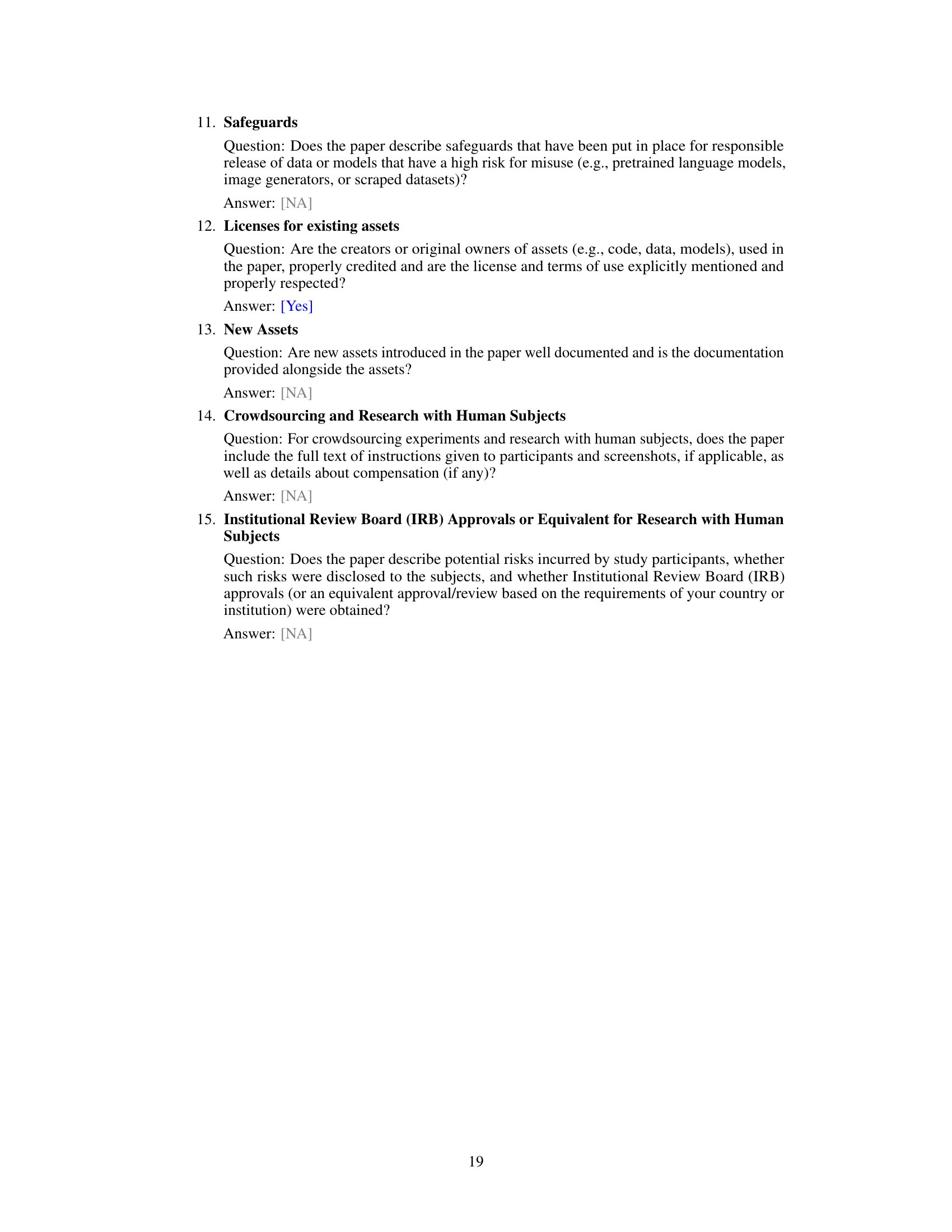

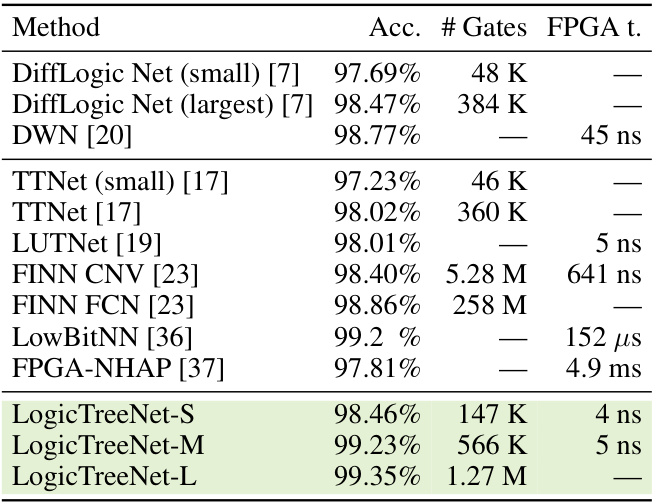

This table presents the main results of the CIFAR-10 experiments. It compares the accuracy and number of logic gates used by various models, including the authors’ LogicTreeNet models and several state-of-the-art baselines. The LogicTreeNet models show significantly fewer gates while achieving comparable or better accuracy than existing methods.

In-depth insights#

Logic Gate Convolutions#

Logic gate convolutions represent a novel approach to incorporating the strengths of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) into the architecture of logic gate networks (LGNs). This involves replacing traditional convolutional kernels with structures composed of interconnected logic gates, such as AND, OR, XOR, and NAND. Instead of weighted sums, these kernels perform logic operations on sets of input activations. The key advantage is the potential for significantly faster and more energy-efficient inference, as LGNs are inherently more compatible with the low-level operations of digital hardware compared to traditional floating-point CNNs. The use of logic gate trees within the convolutional kernels adds further depth and expressive power, capturing complex spatial relationships in the input data beyond simple pairwise logic. The convolutional paradigm maintains the translation equivariance beneficial for image processing tasks, while the underlying logic operations yield a different form of non-linearity compared to traditional activation functions. This fusion of CNN and LGN properties aims to achieve a high performance-to-cost ratio, bridging the gap between deep learning models’ computational demand and hardware capabilities.

Differentiable Relaxations#

The concept of “Differentiable Relaxations” in the context of logic gate networks addresses the inherent non-differentiability of discrete logic operations. Standard logic gates (AND, OR, XOR, etc.) produce discrete outputs, preventing the use of gradient-based optimization methods crucial for training neural networks. Differentiable relaxations overcome this limitation by approximating discrete logic functions with continuous, differentiable counterparts. This allows the application of backpropagation algorithms, enabling the network to learn the optimal configuration of logic gates through gradient descent. The choice of relaxation function is crucial, balancing computational tractability with the accuracy of the approximation. A good relaxation technique will maintain sufficient information about the underlying discrete logic to still allow effective learning, while avoiding complexities that would hinder efficient training or inference. The differentiable relaxation approach is key to enabling the training of complex logic gate networks, allowing them to be applied to machine learning problems typically solved by conventional neural networks while maintaining computational efficiency. This offers a path towards hardware-optimized inference, as logic gates are efficiently implemented in modern computing hardware.

Hardware Efficiency#

The research paper emphasizes hardware efficiency by focusing on the design of Convolutional Differentiable Logic Gate Networks (LGNs). These LGNs utilize logic gates as fundamental building blocks, enabling faster inference compared to conventional neural networks. The paper showcases how this approach leads to significant reductions in gate counts, resulting in smaller and more energy-efficient models. Deep logic gate tree convolutions and logical OR pooling are introduced to enhance the model’s capability and scalability, further improving hardware efficiency. The use of residual initializations and efficient training strategies further optimizes the model for hardware implementation, resulting in considerable cost reductions. FPGA implementation results demonstrate the practical benefits of these designs, achieving impressive inference speeds and surpassing the state-of-the-art in both accuracy and efficiency. The work highlights a promising direction for resource-constrained machine learning applications.

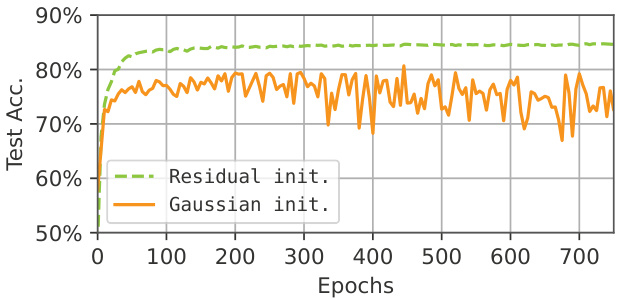

Residual Initializations#

The concept of “Residual Initializations” addresses a critical limitation in training deep Differentiable Logic Gate Networks (LGNs). Standard Gaussian initialization leads to washed-out probability distributions over logic gates, resulting in vanishing gradients and hindering training of deeper networks. Residual initializations counteract this by biasing the initial probability distribution towards a feedforward logic gate, such as ‘A’. This ensures that information is not lost during early training, preventing vanishing gradients. The approach acts as a differentiable form of residual connections without requiring additional logic gates. The key advantage lies in maintaining information flow throughout the network, allowing for the training of significantly deeper and more complex LGNs. This innovation is particularly crucial for achieving high accuracy in complex tasks, as it addresses the key bottleneck of vanishing gradients in deep networks, effectively enabling the scale and depth required for tackling sophisticated machine learning challenges. The technique is further enhanced by its compatibility with efficient training and its natural suitability for hardware implementations.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on convolutional differentiable logic gate networks (LGNs) could explore several promising avenues. Scaling to even larger datasets and more complex tasks beyond CIFAR-10 and MNIST is crucial to demonstrate the generalizability and practical applicability of LGNs. Investigating the effectiveness of different logic gate choices and tree structures within the convolutional kernels, moving beyond random selection and exploring learned connectivity, could significantly improve performance and efficiency. Furthermore, research into hardware-aware optimization techniques is vital. This would involve designing specialized hardware architectures tailored to the unique computational properties of LGNs for more efficient and energy-conscious inference. Finally, combining LGNs with other efficient deep learning paradigms, such as quantization or sparsity, represents a potential path to further enhance their speed and resource efficiency. The exploration of these areas will significantly broaden the impact and practical applicability of this novel approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

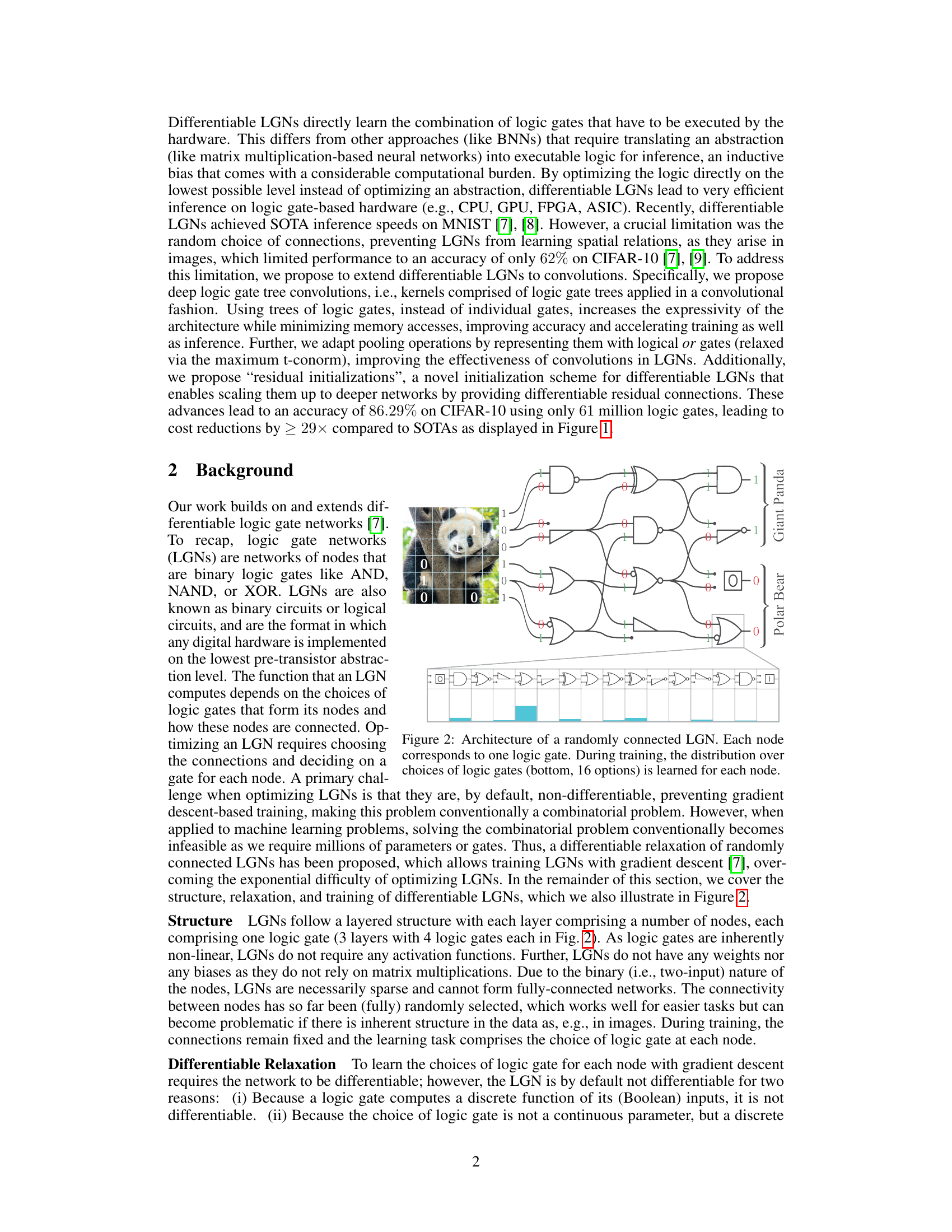

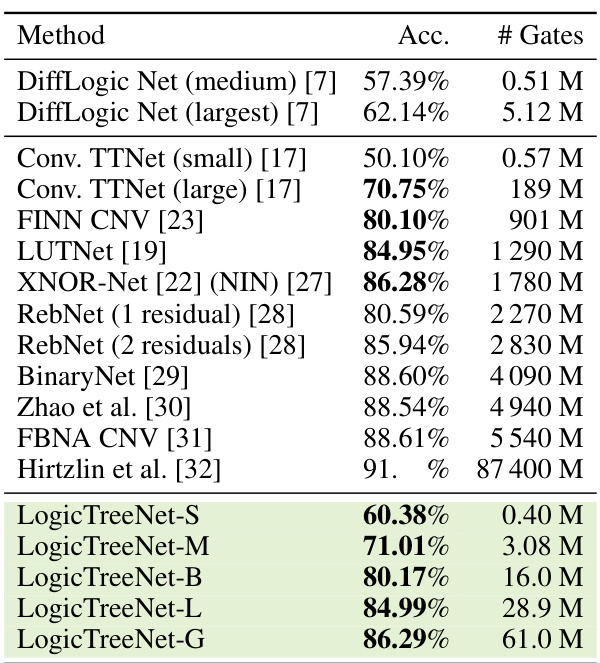

This figure illustrates the architecture of a randomly connected Logic Gate Network (LGN). Each node in the network represents a single logic gate (e.g., AND, NAND, XOR). The network’s function is determined by the choice of logic gate at each node and the connections between them. The bottom part of the diagram shows that during training, the network learns the optimal combination of logic gates for each node by selecting from a distribution of 16 possible gates. The example given in the figure shows how an LGN processes binary inputs representing image pixels (of a panda and a polar bear) to classify them.

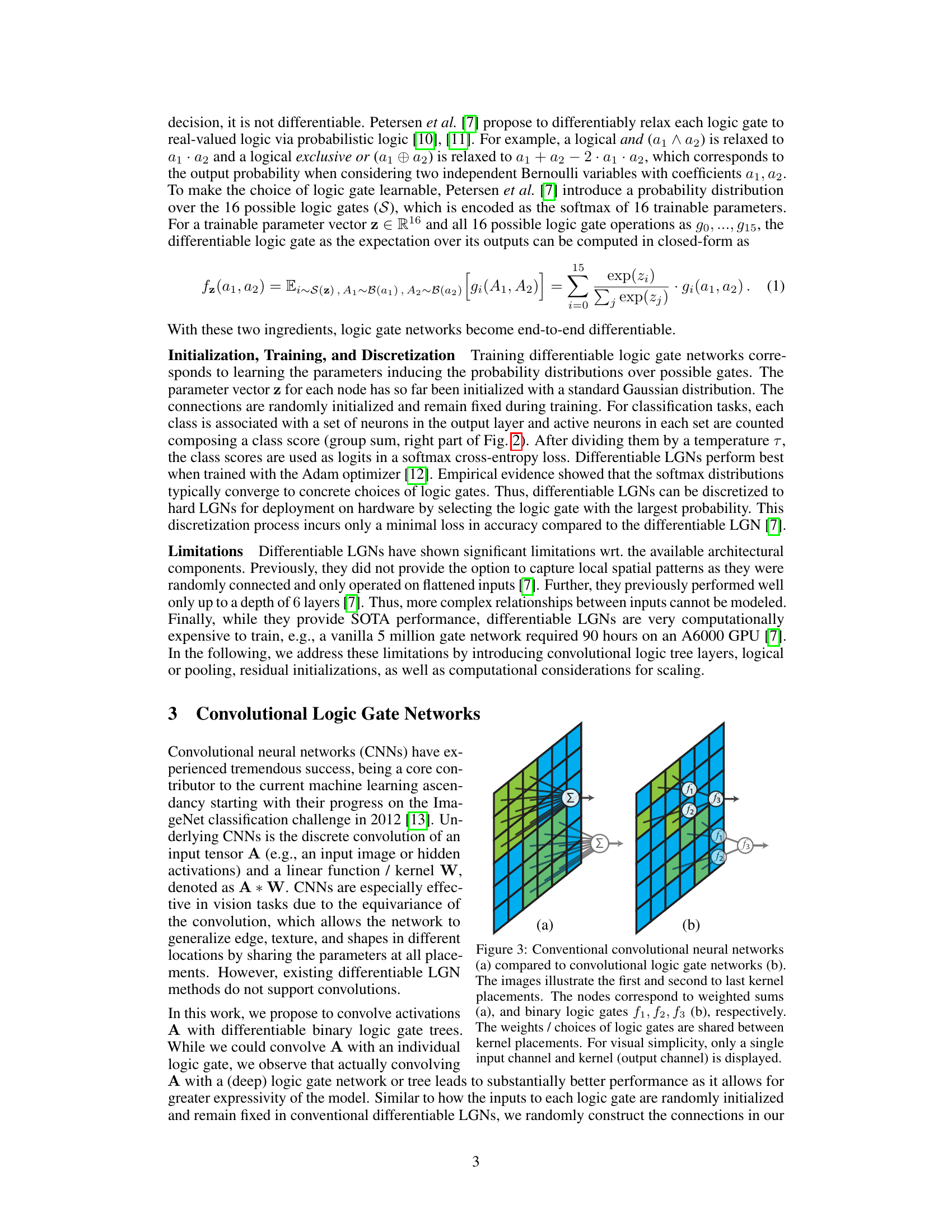

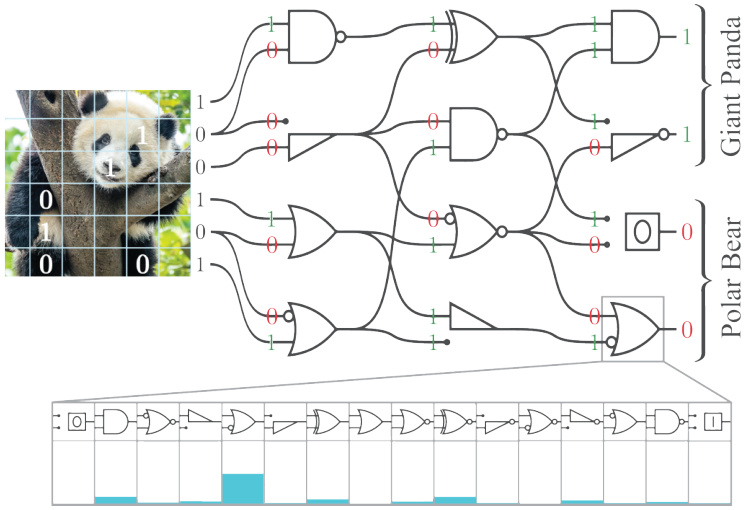

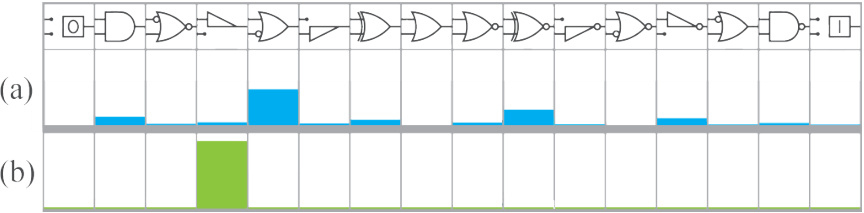

This figure compares the conventional convolutional neural networks with the proposed convolutional logic gate networks. The left side (a) shows a conventional CNN where kernel weights are summed. The right side (b) shows the proposed convolutional logic gate network which uses logic gates (f1, f2, f3) instead of weighted sums. Both illustrations depict shared weights/logic gate choices across kernel placements for spatial efficiency. Only one input and output channel is shown for clarity.

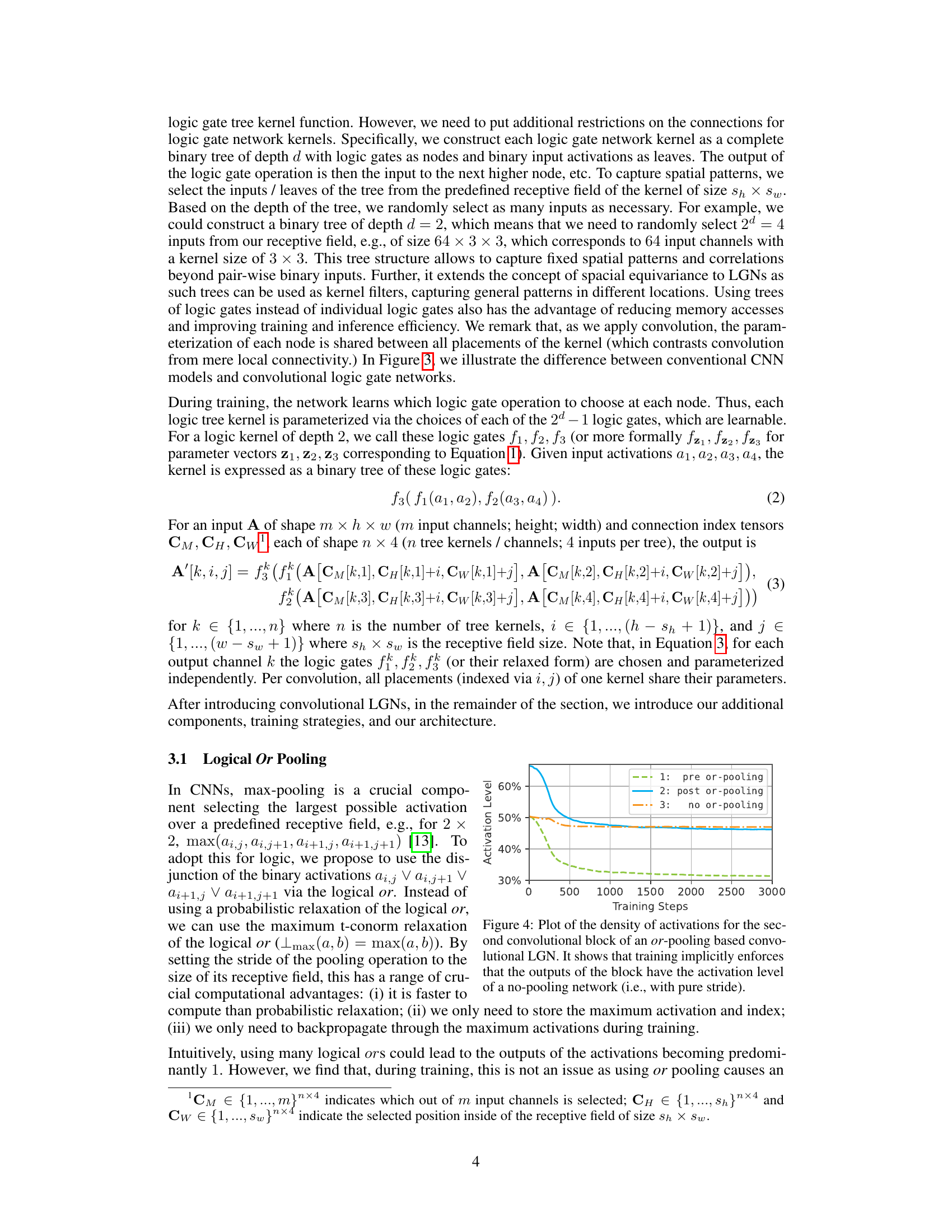

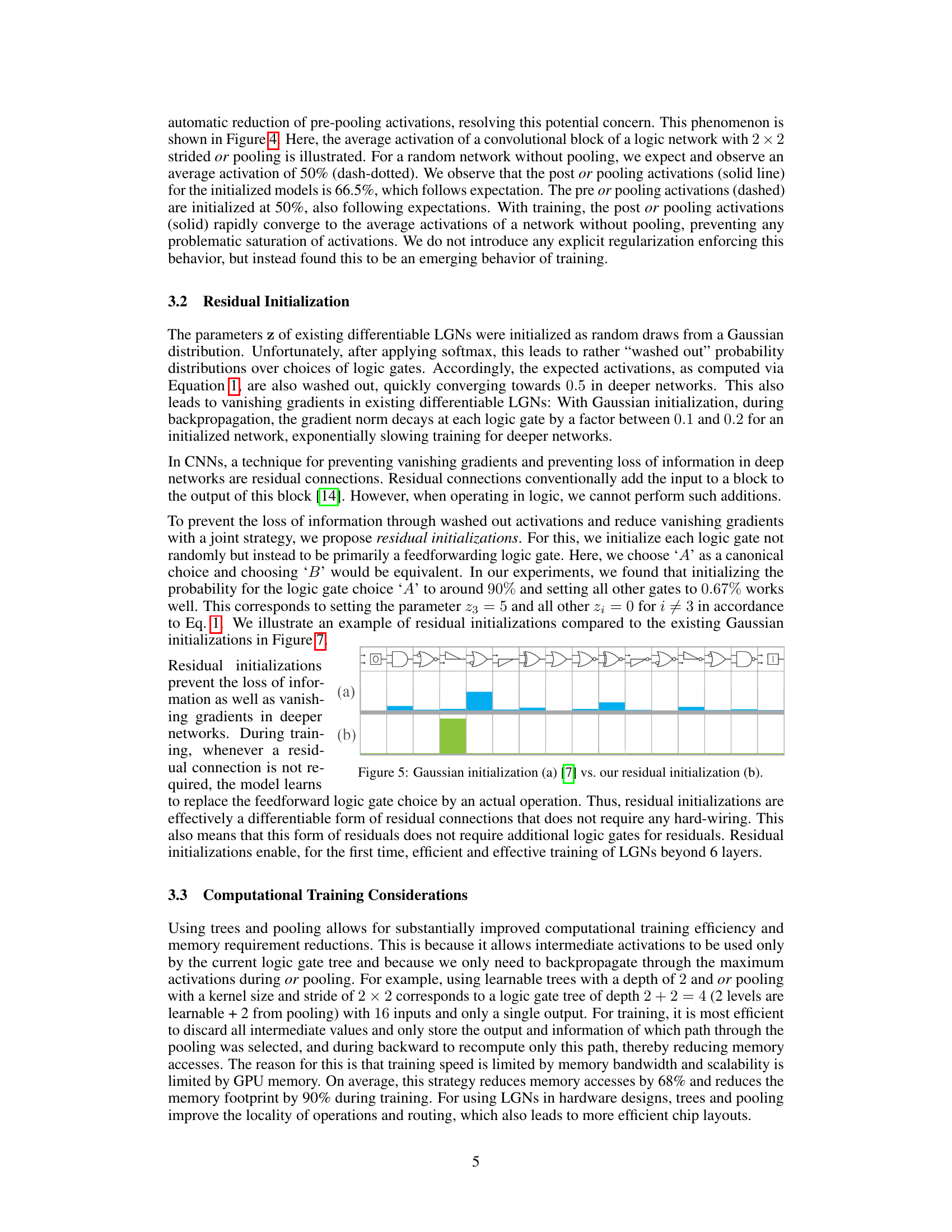

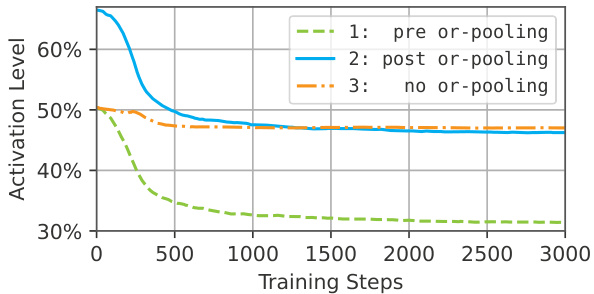

This figure shows the activation level during training for three different scenarios: with pre-or-pooling, with post-or-pooling, and without or-pooling. It demonstrates that, even without explicit regularization, training implicitly leads to the activation levels of the no-or-pooling scenario when using or-pooling.

This figure compares the architecture of conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with the proposed convolutional logic gate networks (CLGNs). In CNNs, each kernel performs a weighted sum of the inputs, while in CLGNs, kernels consist of binary logic gates (f1, f2, f3) arranged in a tree structure. The weights in CNNs are replaced by the choices of logic gates in CLGNs, which are learned during training. The figure highlights that the logic gate choices are shared across different locations within the image, mimicking the weight sharing in CNNs. The simplified representation uses a single input and output channel for clarity.

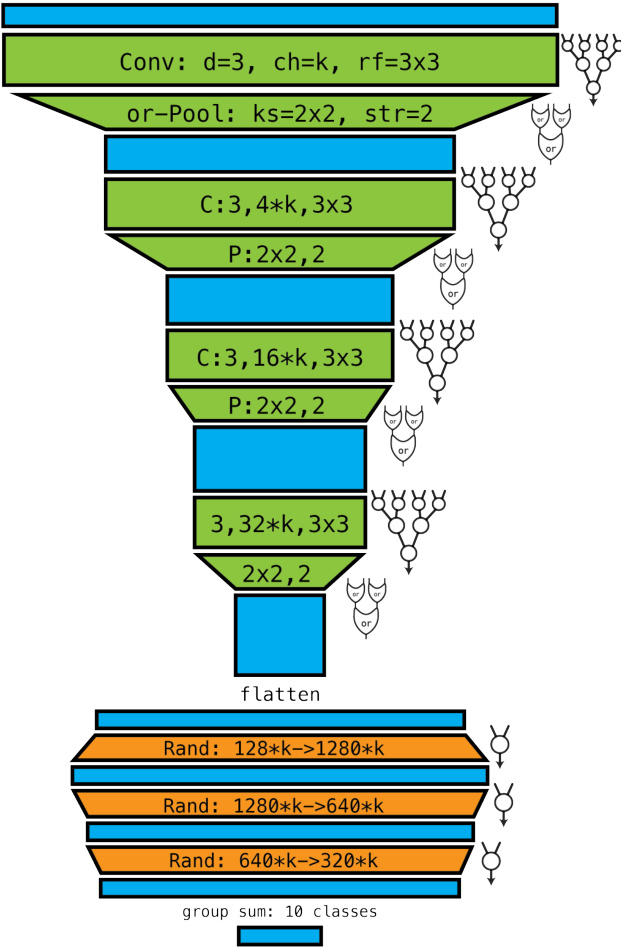

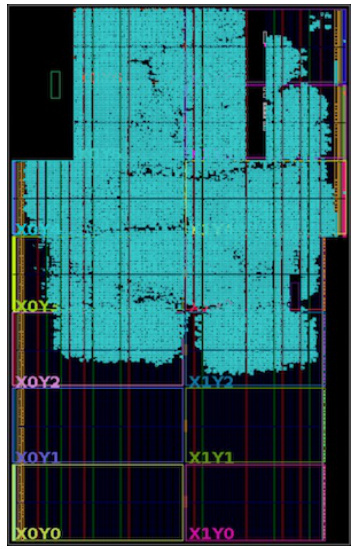

This figure shows the architecture of the LogicTreeNet used in the paper. It’s a convolutional neural network specifically designed for efficient inference using logic gates. The architecture consists of convolutional blocks, each containing logic gate trees, followed by or-pooling layers to reduce dimensionality. The final layers are fully connected using randomly connected logic gates, ultimately leading to a group sum for classification. The diagram visually depicts the structure, highlighting the learnable logic gates (circles) and fixed or-gates.

This figure shows the trade-off between the number of logic gates and accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The plot compares the performance of the proposed Convolutional Differentiable Logic Gate Networks (CDLGNs) with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) baselines. The authors’ models significantly outperform the existing methods, achieving higher accuracy with considerably fewer logic gates. The x-axis is logarithmic, highlighting the substantial efficiency gains.

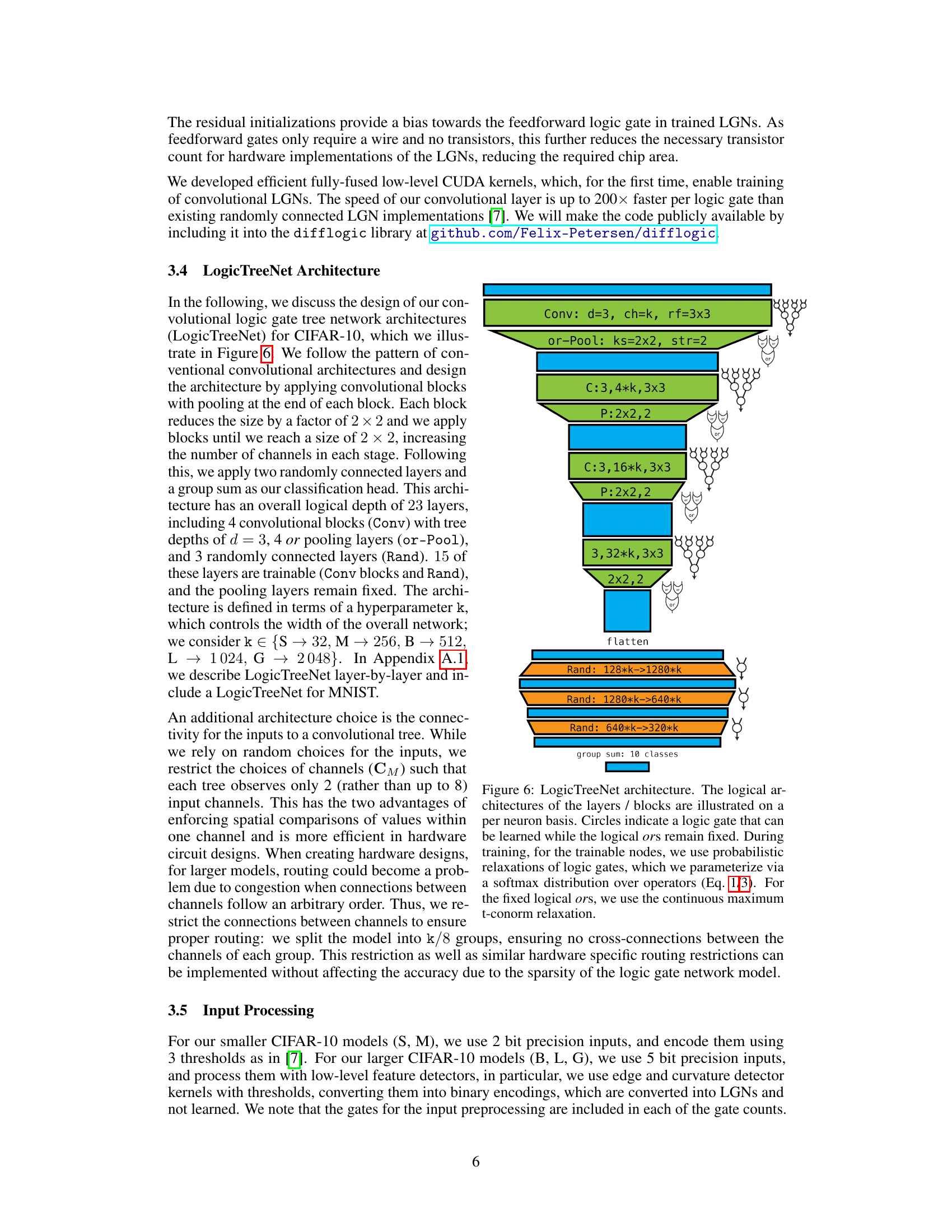

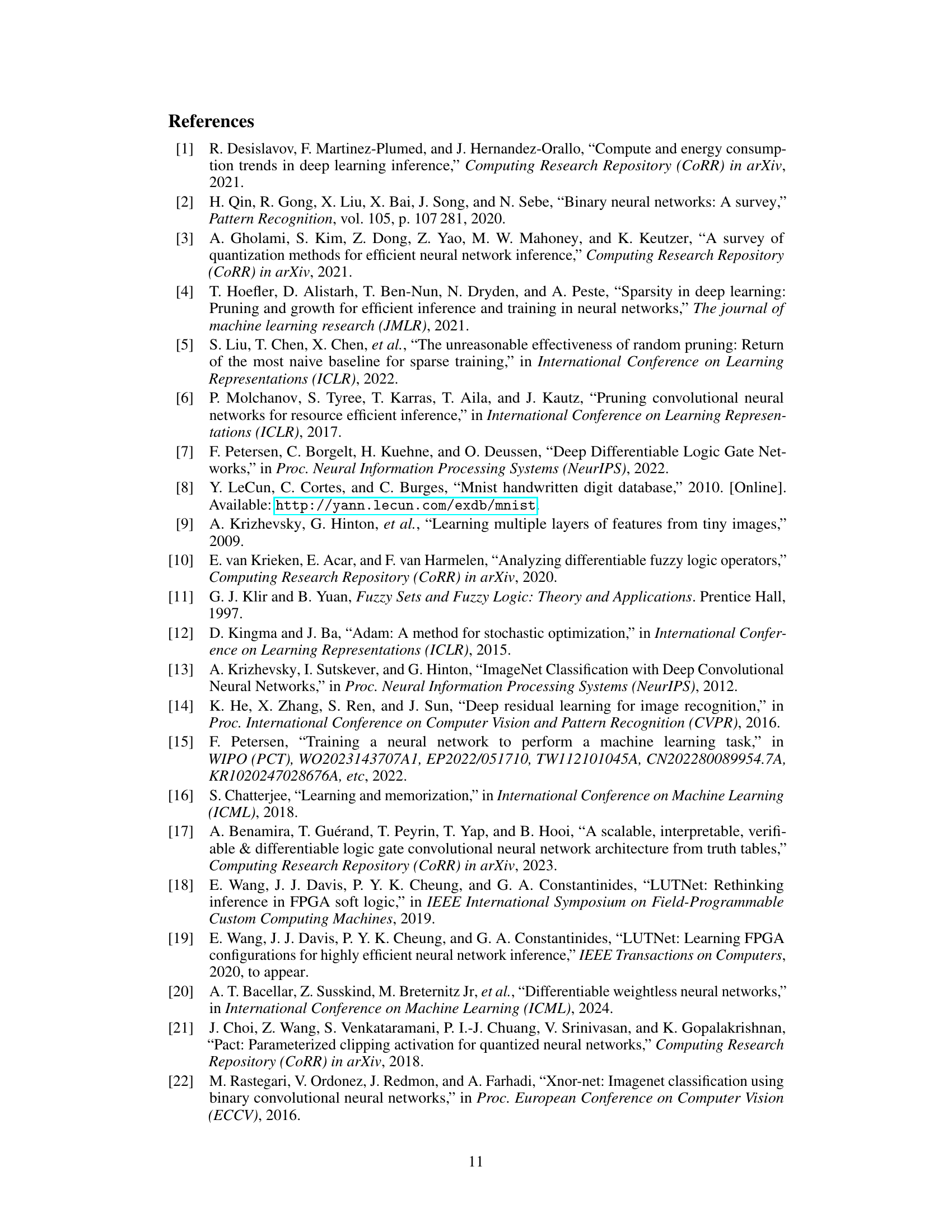

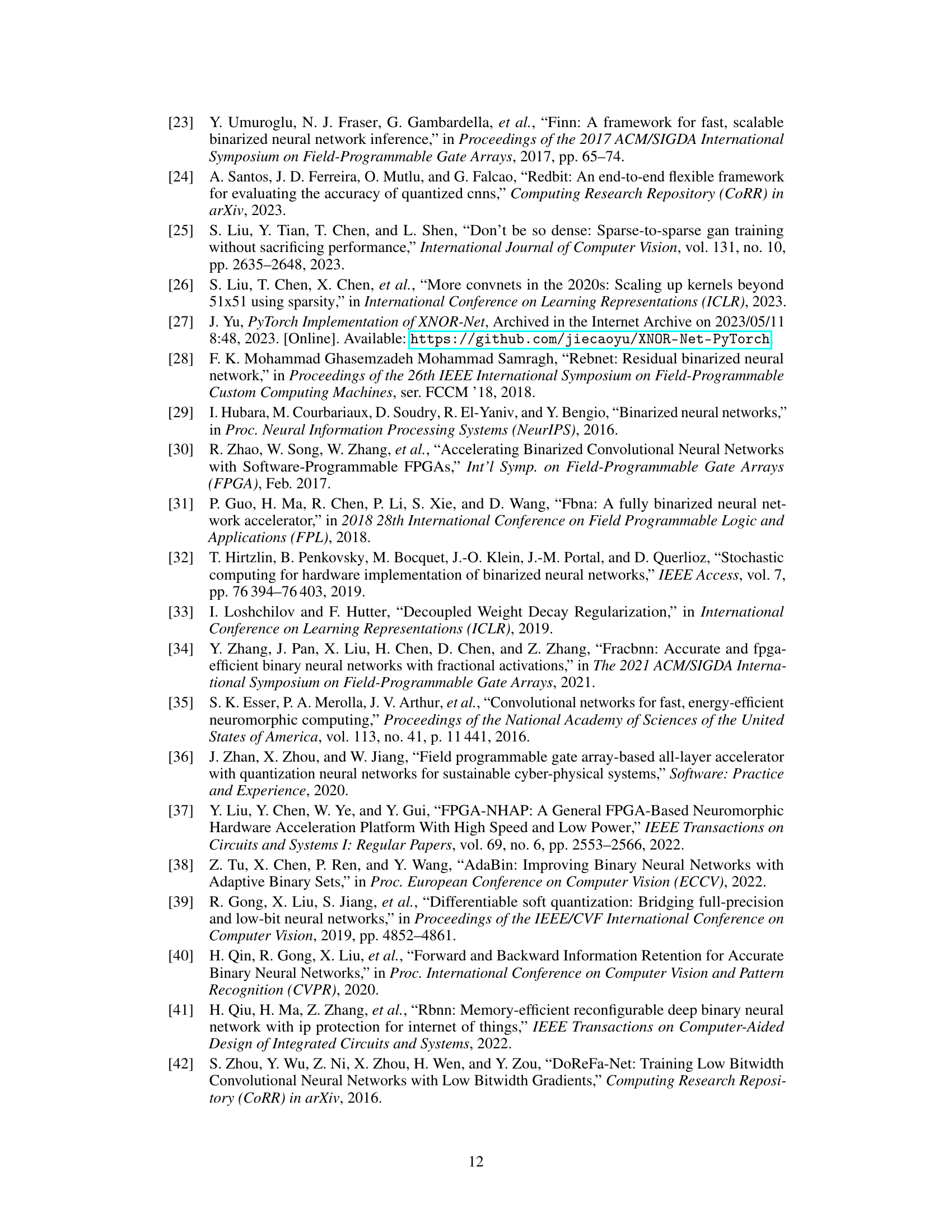

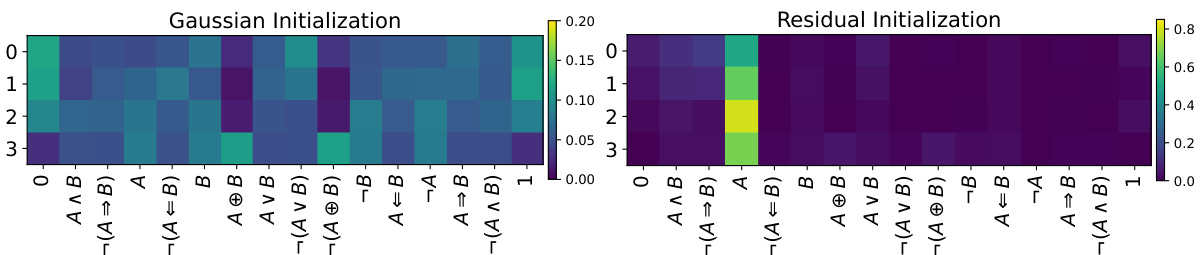

This figure compares the distribution of logic gates chosen during training for a MNIST model using two different initialization methods: Gaussian and Residual. Each cell in the heatmaps represents the probability of a specific logic gate being selected for a particular layer and gate position. The Gaussian initialization shows a more uniform distribution across the gates in most layers, indicating a less biased training process. In contrast, the Residual initialization demonstrates a strong bias towards the identity gate (‘A’) in many layers, potentially stemming from the intentional bias used in this initialization method to improve training stability and mitigate vanishing gradients. The color intensity represents the probability; darker colors mean lower probability.

This figure shows the architecture of the LogicTreeNet model for CIFAR-10. The architecture is composed of convolutional blocks with or-pooling layers, followed by randomly connected layers and a group sum for classification. Each block reduces the spatial size of the feature maps. The figure highlights the use of logic gate trees, where circles represent learnable logic gates, while the logical OR gates for pooling are fixed. The training process involves learning the probability distributions over logic gates using a softmax function and applying a continuous maximum t-conorm relaxation to the fixed OR gates.

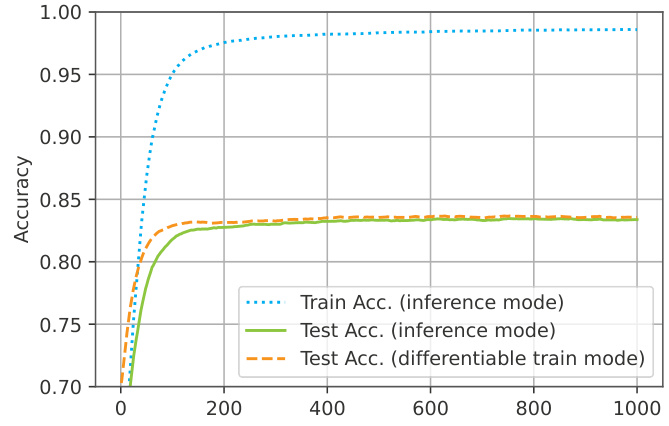

This figure shows the training and testing accuracy curves for a convolutional LGN model trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Three curves are presented: training accuracy in inference mode (discretized), testing accuracy in inference mode (discretized), and testing accuracy during differentiable training. The plot highlights that the discrepancy between differentiable training accuracy and inference accuracy is minimal towards the end of training, indicating a successful relaxation and discretization process.

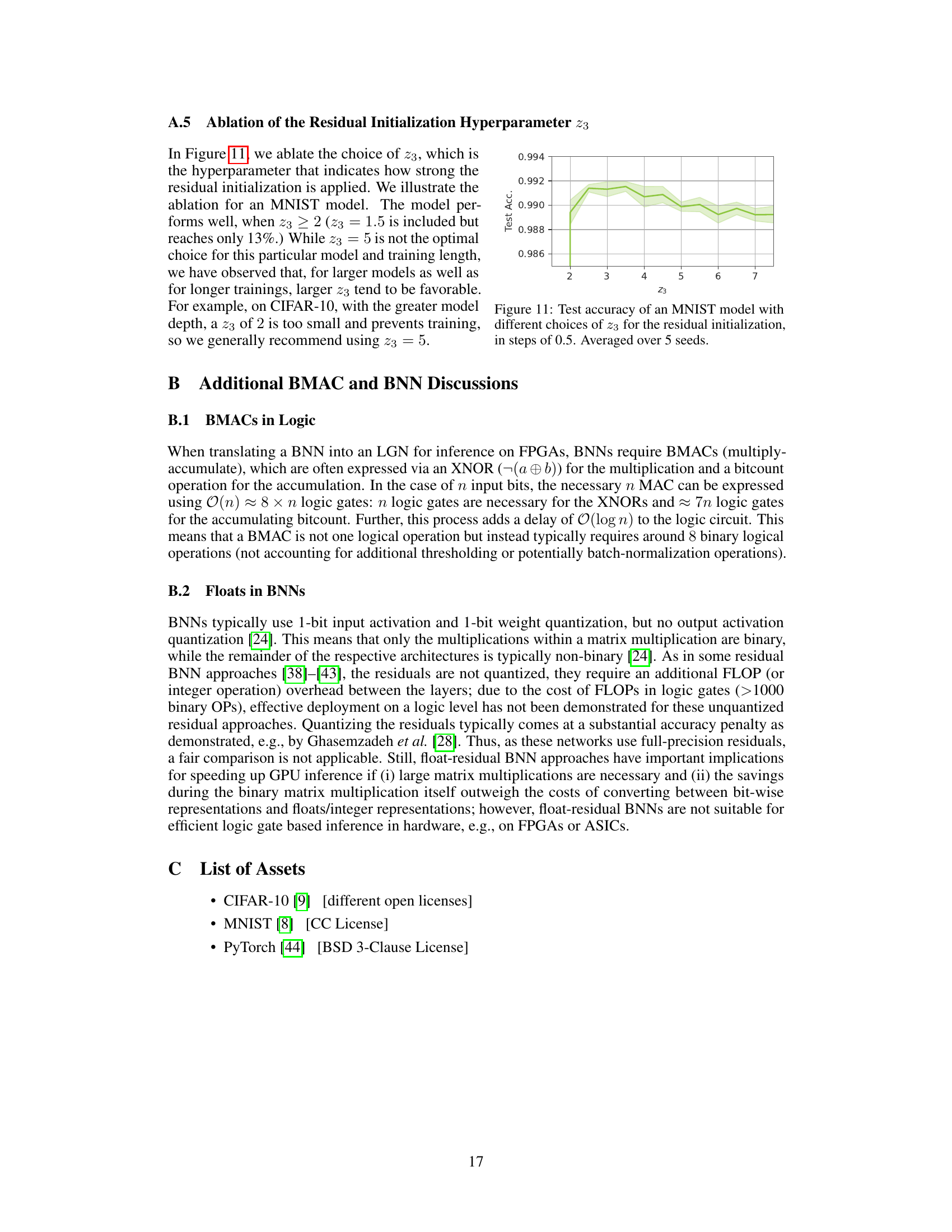

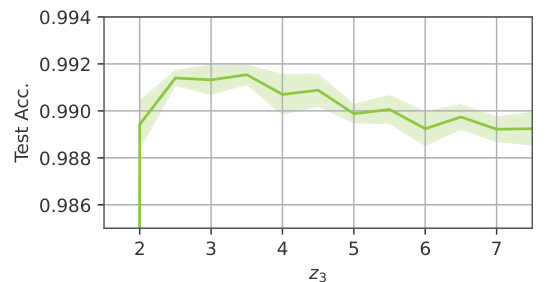

This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the hyperparameter z3, which controls the strength of the residual initialization in an MNIST model. The x-axis represents different values of z3, and the y-axis shows the corresponding test accuracy. The plot reveals that the model performs well when z3 is greater than or equal to 2, achieving high accuracy around z3=5. Values of z3 below 2 lead to significantly lower accuracy. The error bars represent the average over 5 different random seeds used for training, indicating the variability in performance.

More on tables

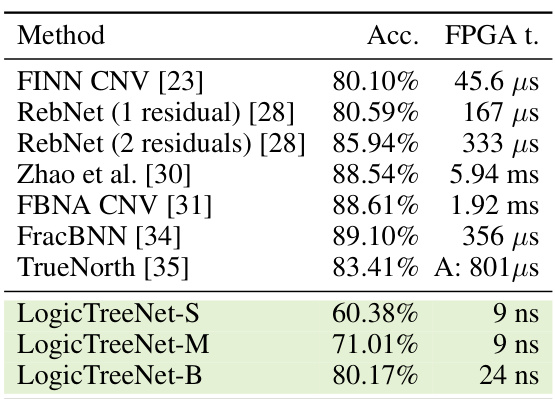

This table compares the inference time per image on a Xilinx VU13P FPGA for various methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The time is the bottleneck of data transfer to FPGA. The methods compared include FINN CNV, RebNet (with one and two residual blocks), Zhao et al., FBNA CNV, FracBNN, TrueNorth, and three different sizes of the LogicTreeNet model (S, M, and B). Note that TrueNorth uses an ASIC instead of an FPGA.

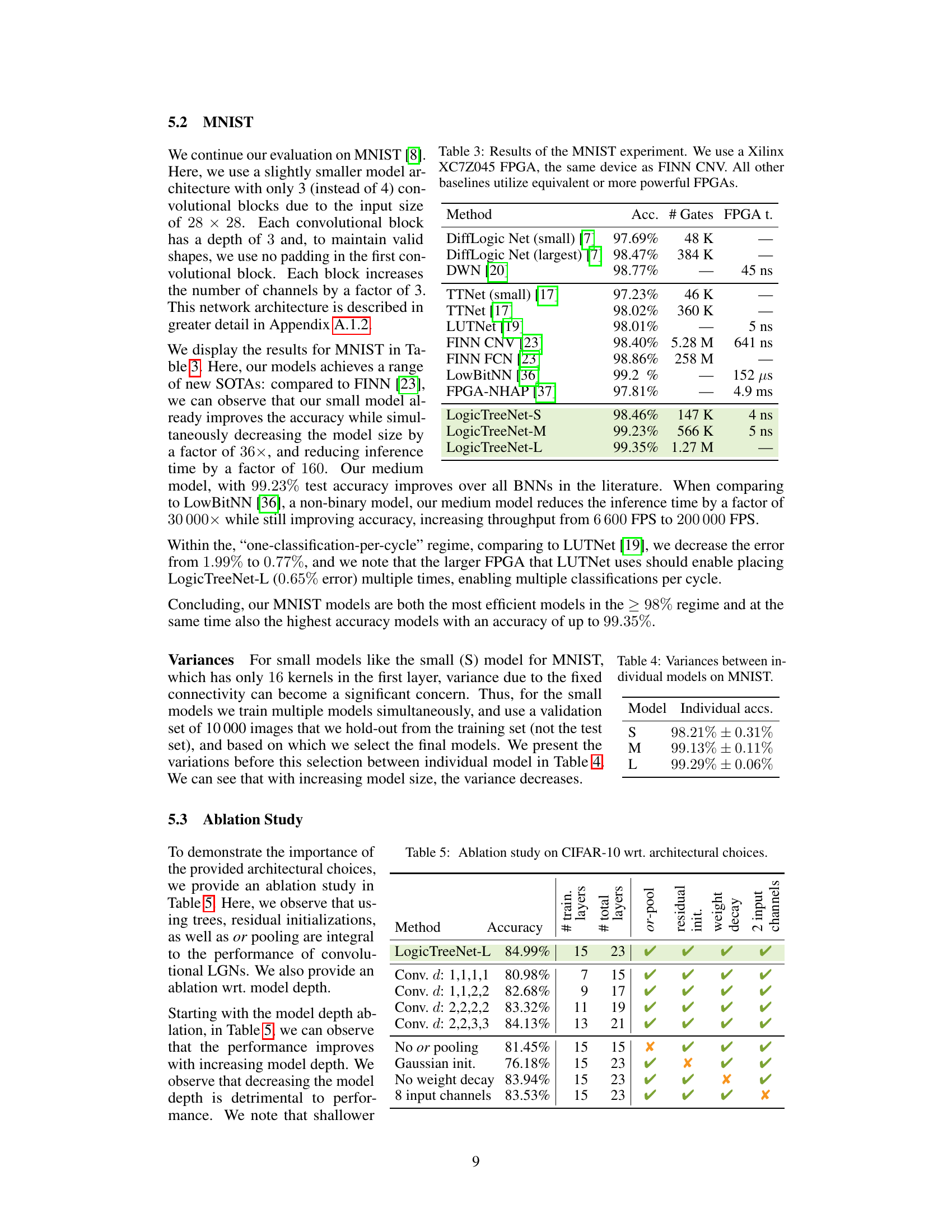

This table presents the results of the MNIST experiments, comparing the proposed LogicTreeNet models to various existing state-of-the-art methods. It shows the accuracy, number of logic gates used, and FPGA inference time for each method. The table highlights the superior efficiency and accuracy of the LogicTreeNet models compared to other approaches in terms of both accuracy and the number of gates used, which is directly proportional to hardware costs.

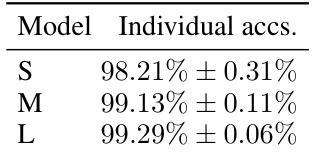

This table shows the accuracy variations observed across multiple runs of different MNIST models (S, M, and L). The variations are presented as mean accuracy ± standard deviation, highlighting the impact of random initialization and fixed connectivity on model performance.

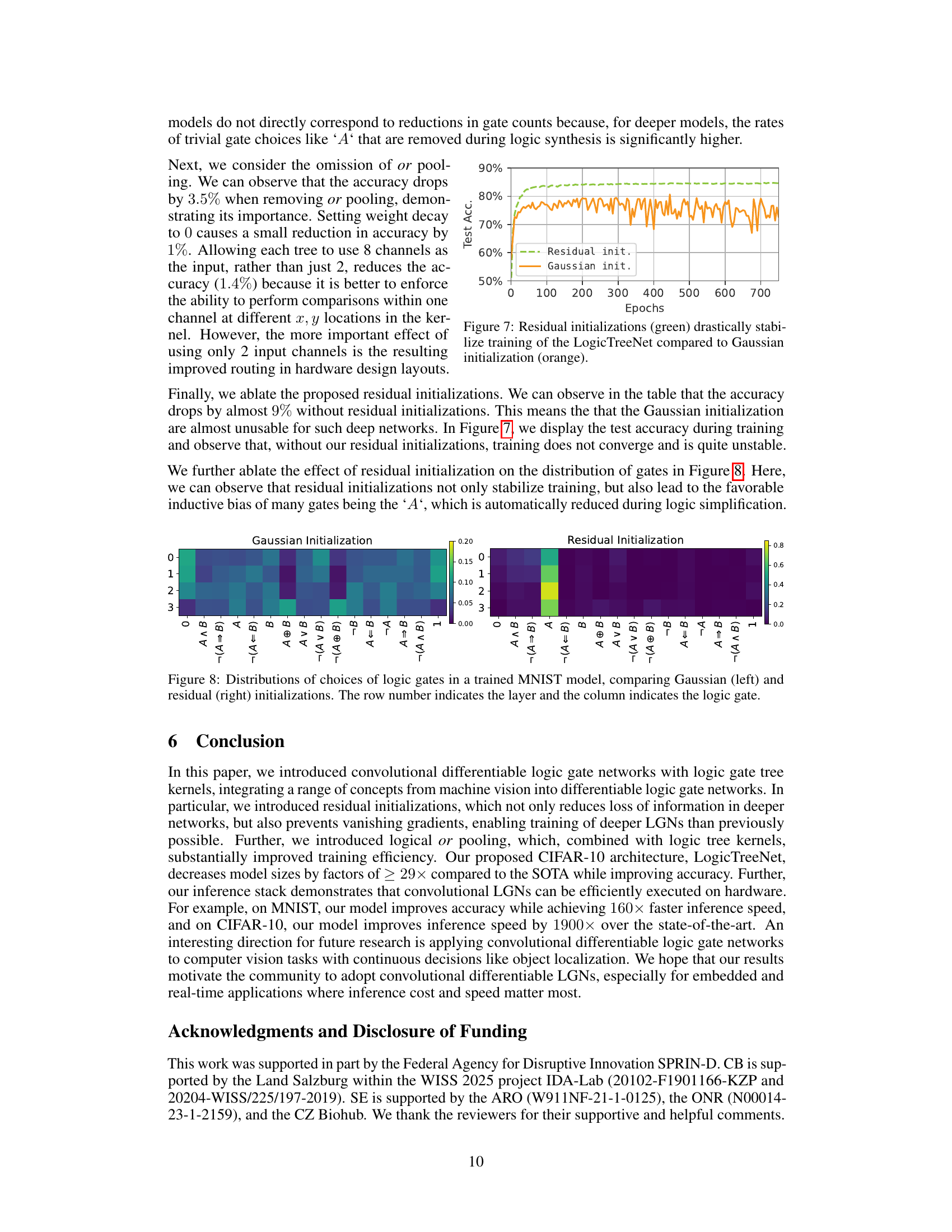

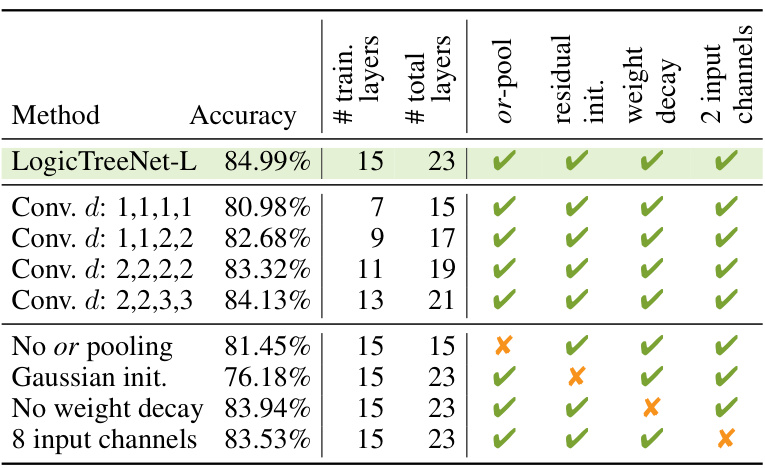

This ablation study analyzes the impact of different architectural components of the LogicTreeNet model on its performance. The table shows the accuracy achieved with various combinations of architectural elements, including the use of trees, residual initializations, or-pooling, weight decay, and the number of input channels. The study demonstrates the importance of each element for the model’s success.

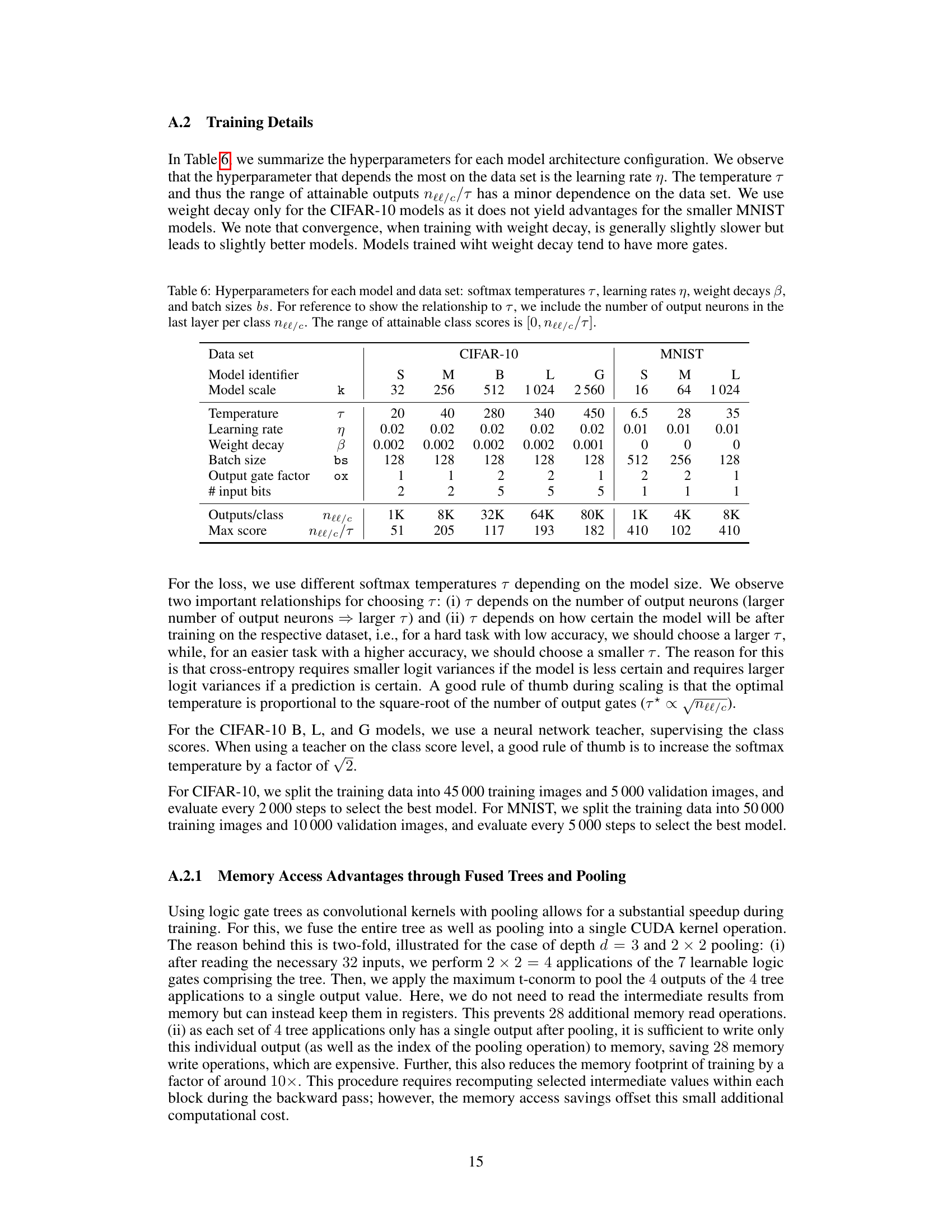

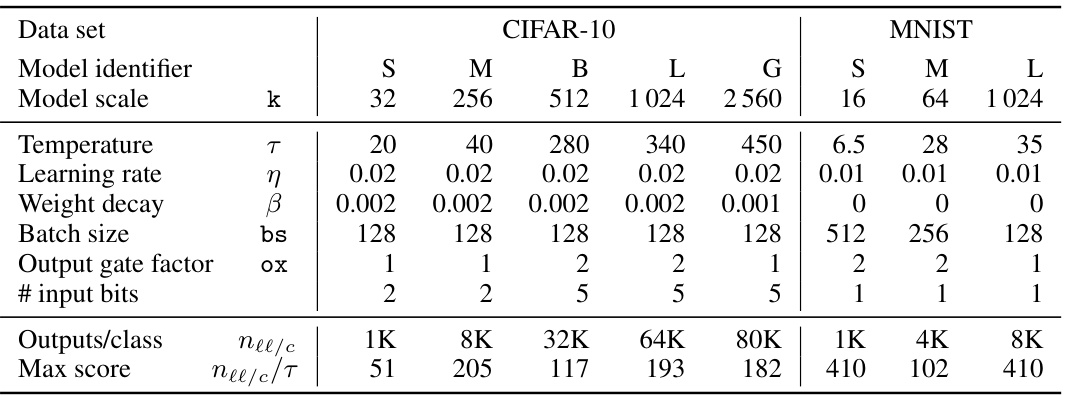

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training different models on CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets. It lists the softmax temperature, learning rate, weight decay, batch size, output gate factor, number of input bits, number of outputs per class, and the maximum attainable class score for each model.

Full paper#