↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reinforcement learning (RL) often involves finding optimal policies within Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). While sample complexity for finite-horizon and discounted reward MDPs is well-understood, the average-reward setting remains challenging. This is because the long-run average reward criterion is more complex to analyze than the finite or discounted criteria and existing algorithms exhibit suboptimal dependence on critical problem parameters. This makes it challenging to develop sample-efficient algorithms for solving average-reward MDPs, which are critical for many real-world applications.

This research paper addresses the above issues by establishing tight sample complexity bounds for both weakly communicating and general average-reward MDPs. The authors achieve these results through a novel reduction technique that transforms the average-reward problem into a discounted-reward problem. This approach, combined with refined analysis techniques, allows the researchers to obtain minimax optimal bounds and a significantly improved understanding of average-reward MDPs. The new theoretical framework established by this paper also suggests new directions for future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it resolves the long-standing open problem of optimal sample complexity for average-reward Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). This significantly advances reinforcement learning theory and provides practically useful guidelines for algorithm design. The results are particularly important for real-world applications of RL, where sample efficiency is a primary concern. The improved bounds and new theoretical framework will inspire further research into efficient RL algorithms and their fundamental limits.

Visual Insights#

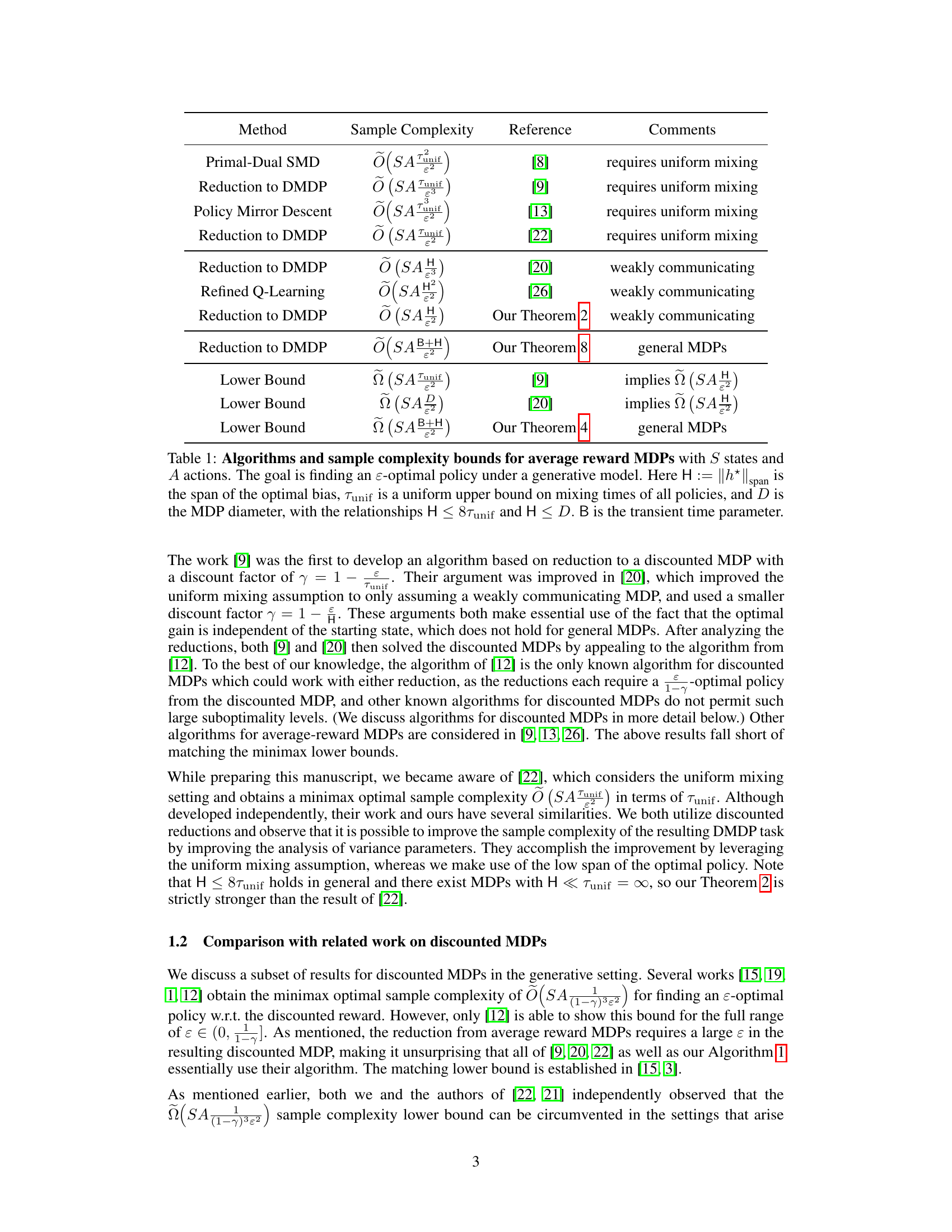

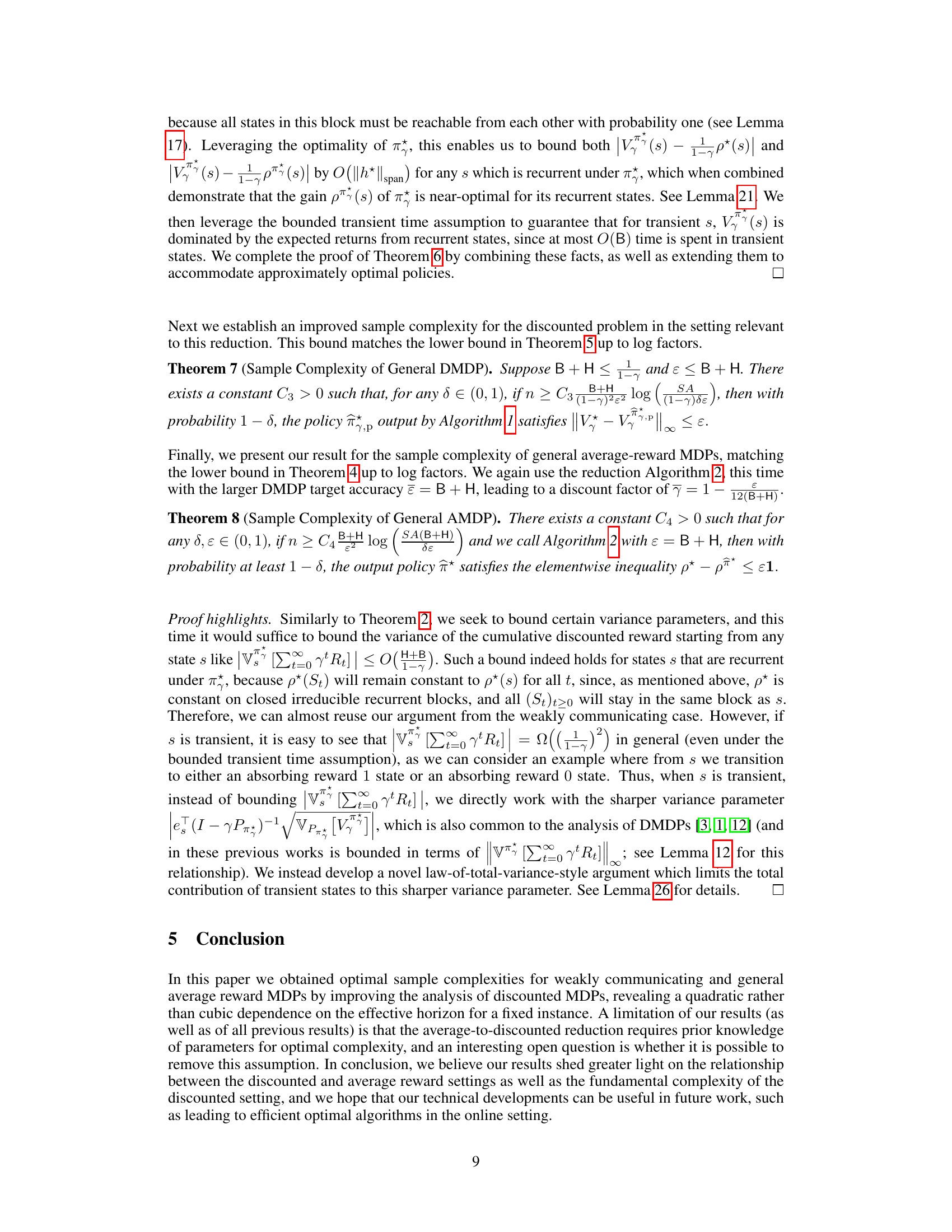

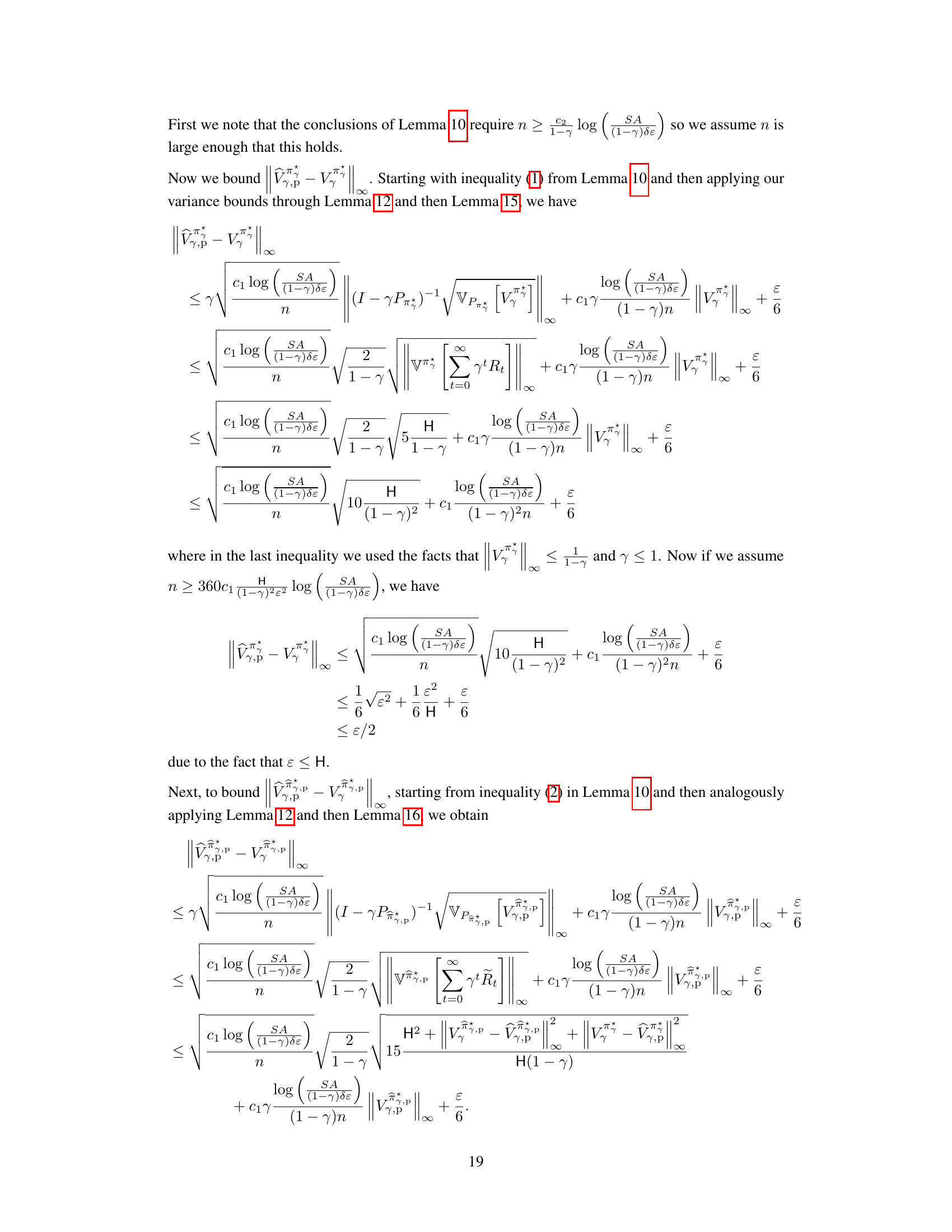

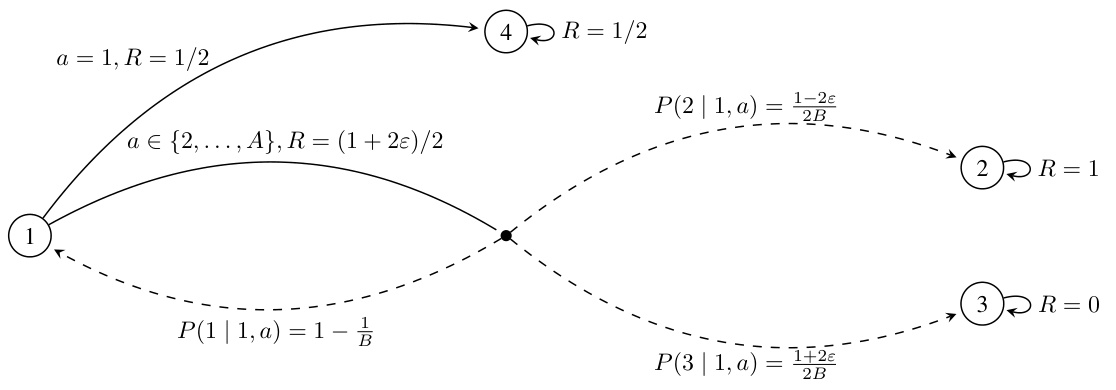

This figure presents a general Markov Decision Process (MDP) with three states and one transient state, where the discounted approximation method fails unless the discount factor γ is greater than or equal to Ω(T), which is significantly larger than the span of the optimal bias function (||h*||span). The MDP includes a transient state (state 1) with two actions. Action 1 leads to an immediate reward of 1 and then transitions to the absorbing state 3 with reward 0, while action 2 transitions to the absorbing state 2 with a reward of 0.5. The parameter T controls the expected number of steps before leaving the transient state. The figure illustrates that the long-term average reward depends on this transient behavior, making the discounted approximation (which focuses on short-term rewards) ineffective unless γ is sufficiently large to account for this long-term behavior.

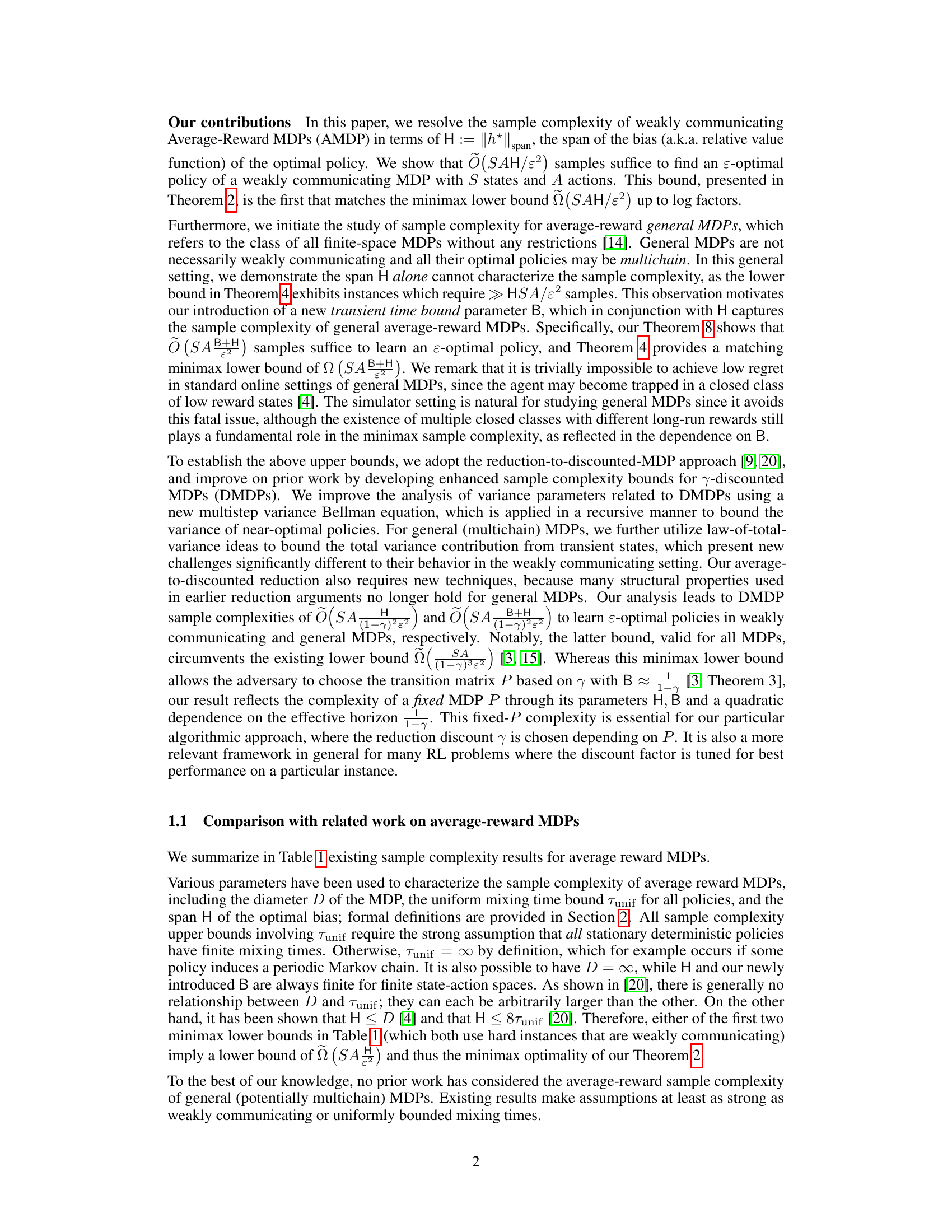

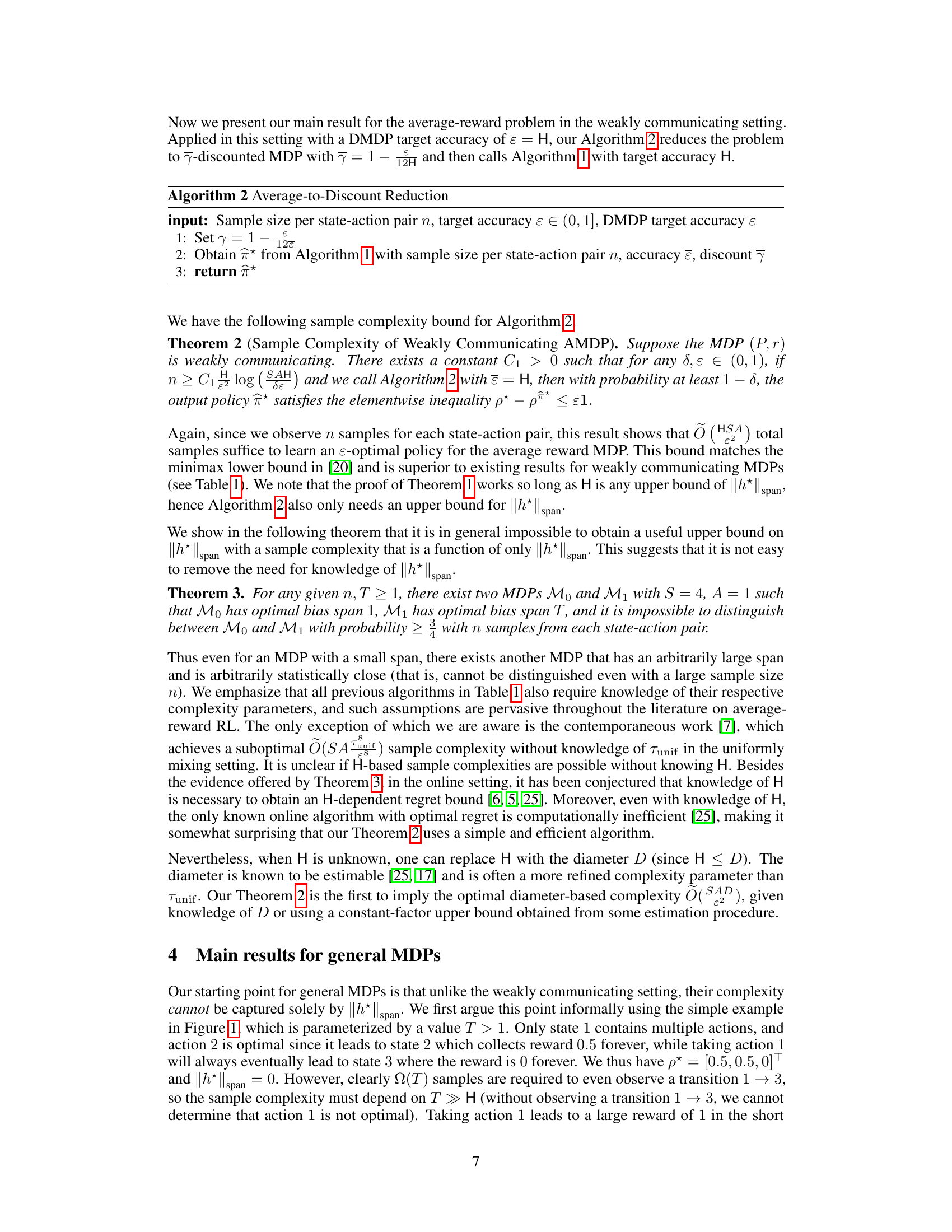

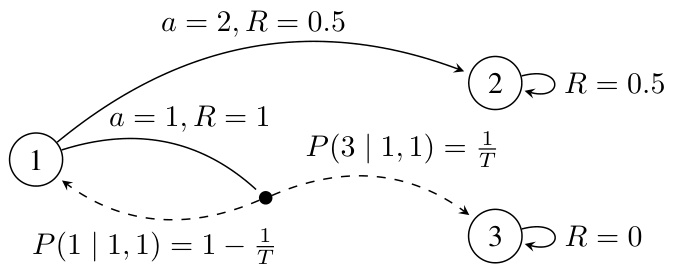

This table compares existing algorithms and their sample complexities for solving average reward Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) under a generative model. It shows different methods used, their associated sample complexity bounds (expressed in terms of the number of states S, actions A, and other relevant parameters), and any assumptions required (such as uniform mixing times or weak communication). The table also highlights the minimax optimality or suboptimality of these bounds, helping to situate the authors’ contributions within the existing literature. Key parameters include the span of the optimal bias function (H), the diameter of the MDP (D), a uniform mixing time bound (Tunif), and a new parameter introduced by the authors, B (transient time).

In-depth insights#

Span-Based Complexity#

The concept of “Span-Based Complexity” in the context of reinforcement learning (RL) and Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) centers on quantifying the difficulty of solving an MDP using the span of the optimal bias function (H). The span measures the difference between the maximum and minimum relative values of the optimal policy across all states. A smaller span implies a simpler problem to solve, while a larger span suggests a more complex one. In average-reward MDPs, this metric is particularly valuable because the sample complexity often depends directly on it. This contrasts with traditional metrics like diameter or mixing times, which might be infinite in the presence of multiple recurrent classes, but which also might not fully capture complexity in some specific MDPs. This span-based approach provides a more refined and informative measure of complexity in weakly communicating and general average-reward MDPs, particularly because it’s always finite for finite MDPs, leading to tighter sample complexity bounds that are minimax optimal, up to logarithmic factors. The key finding relates the sample complexity to both the span (H) and a novel transient time parameter (B), offering a comprehensive complexity characterization for various MDPs. This approach significantly improves understanding of the inherent hardness of average-reward RL problems and opens doors for the development of more efficient algorithms.

Weakly Communicating MDPs#

In the context of reinforcement learning, weakly communicating Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) represent a specific class of MDPs with structural properties that simplify analysis and algorithm design. These MDPs are characterized by a partition of states into two subsets: transient states and recurrent states. All policies lead to a unique recurrent state, making long-run average reward analysis tractable. The primary simplification is that transient states’ long-run impact on the average reward is negligible; algorithms can focus on the recurrent states. This characteristic makes weakly communicating MDPs more amenable to theoretical analysis, particularly regarding sample complexity bounds. Optimal sample complexity analysis, as achieved by the authors, leverages this structure to obtain tighter bounds than those possible for general MDPs. The span of the optimal bias function, a key parameter reflecting the complexity, becomes a crucial element in determining sample complexity. The assumption of weak communication allows for efficient algorithms to find near-optimal policies using a reasonable number of samples, a crucial finding in the context of RL algorithm efficiency.

General Average Reward#

The study of “General Average Reward” Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) presents a significant challenge in reinforcement learning due to the complexities introduced by multichain structures. Unlike weakly communicating MDPs, where the optimal policy is unichain, general MDPs allow for optimal policies that may involve multiple closed recurrent classes, each with a distinct average reward. This multichain characteristic necessitates a more nuanced approach to understanding and addressing the problem. The span of the optimal bias function (H) alone is insufficient to capture the complexities of general MDPs. A new parameter, the transient time bound (B), is introduced to quantify the expected time spent in transient states before reaching a recurrent state, which significantly impacts the sample complexity. The introduction of B provides a more complete characterization of the sample complexity in general average-reward MDPs, showing that it scales with both B and H, thus capturing both the transient and recurrent aspects of the problem. This finding highlights a key difference between weakly communicating and general MDPs, demonstrating that existing methods relying solely on H are fundamentally inadequate for the general case. The optimal sample complexity is determined by a balance between exploring the transient states to find the optimal recurrent class, and then learning the optimal policy within that class. Minimax optimal bounds are established for general MDPs, demonstrating the theoretical limits of efficient learning in this complex setting.

Discounted MDP Reduction#

The concept of “Discounted MDP Reduction” centers on simplifying the complexities of average-reward Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) by transforming them into discounted-reward MDPs. This approach is particularly valuable because solving discounted-reward MDPs is computationally more tractable. The core idea involves introducing a discount factor (gamma) that weighs future rewards less heavily than immediate ones. This reduction is not always straightforward, requiring careful consideration of the specific properties of the average-reward MDP, such as its communication structure (e.g., weakly communicating vs. general MDPs). A key challenge lies in selecting an appropriate discount factor that balances the need for computational efficiency with the accuracy of the approximation. The choice of gamma is crucial because an excessively small value may preserve the subtleties of the average-reward problem but render the discounted problem computationally intensive, while an overly large value might lead to a poor approximation that does not reflect the long-term average behavior. The success of the reduction approach often relies on the assumption that the average-reward MDP satisfies certain properties, which if violated, could significantly limit the applicability of this method. Therefore, the reduction to discounted MDPs offers a powerful avenue for solving average-reward MDPs, but its effectiveness hinges on careful consideration of the discount factor and the underlying assumptions about the MDP structure.

Minimax Optimality#

The concept of minimax optimality is central to the study of reinforcement learning algorithms. It signifies that an algorithm achieves optimal performance in the worst-case scenario, guaranteeing a certain level of effectiveness regardless of the environment’s characteristics. In the context of this research paper, establishing minimax optimality likely involves demonstrating that the proposed algorithm’s sample complexity (the number of samples needed to learn an optimal policy) is no worse than the theoretically proven lower bound. This lower bound represents the fundamental limit on how well any algorithm can perform, given the problem’s inherent difficulty. Thus, proving minimax optimality is a strong theoretical result, demonstrating that the algorithm’s performance is not only good, but also the best possible within certain assumptions, such as those concerning the generative model (access to independent samples of the environment’s dynamics). The paper likely focuses on achieving this minimax optimality concerning relevant parameters such as the number of states (S) and actions (A) within a Markov Decision Process (MDP), as well as parameters that may quantify the problem’s complexity, such as the span of the bias function of the optimal policy or a transient-time parameter (B). The demonstrated optimality underscores the algorithm’s robustness and efficiency, giving strong assurance of its performance in practical applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

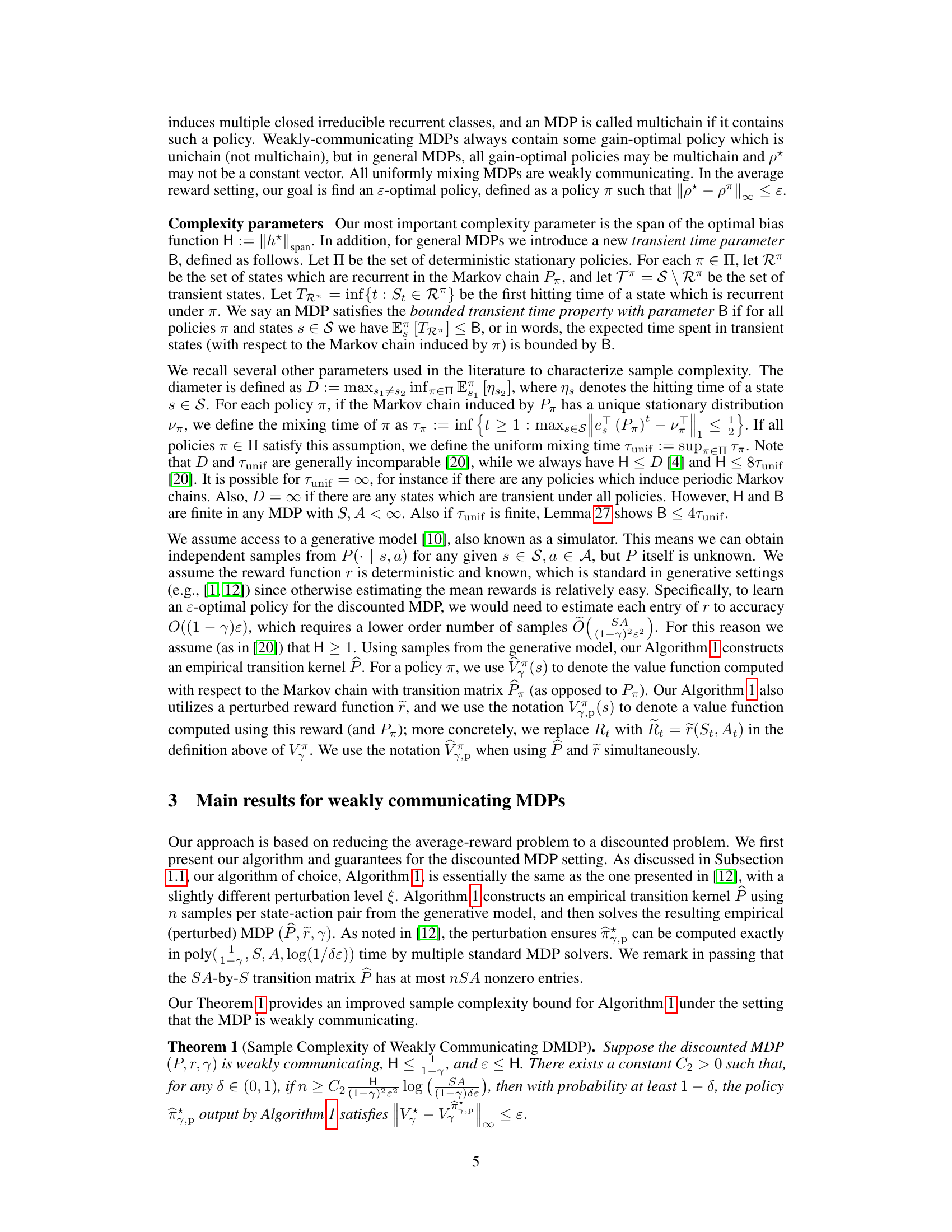

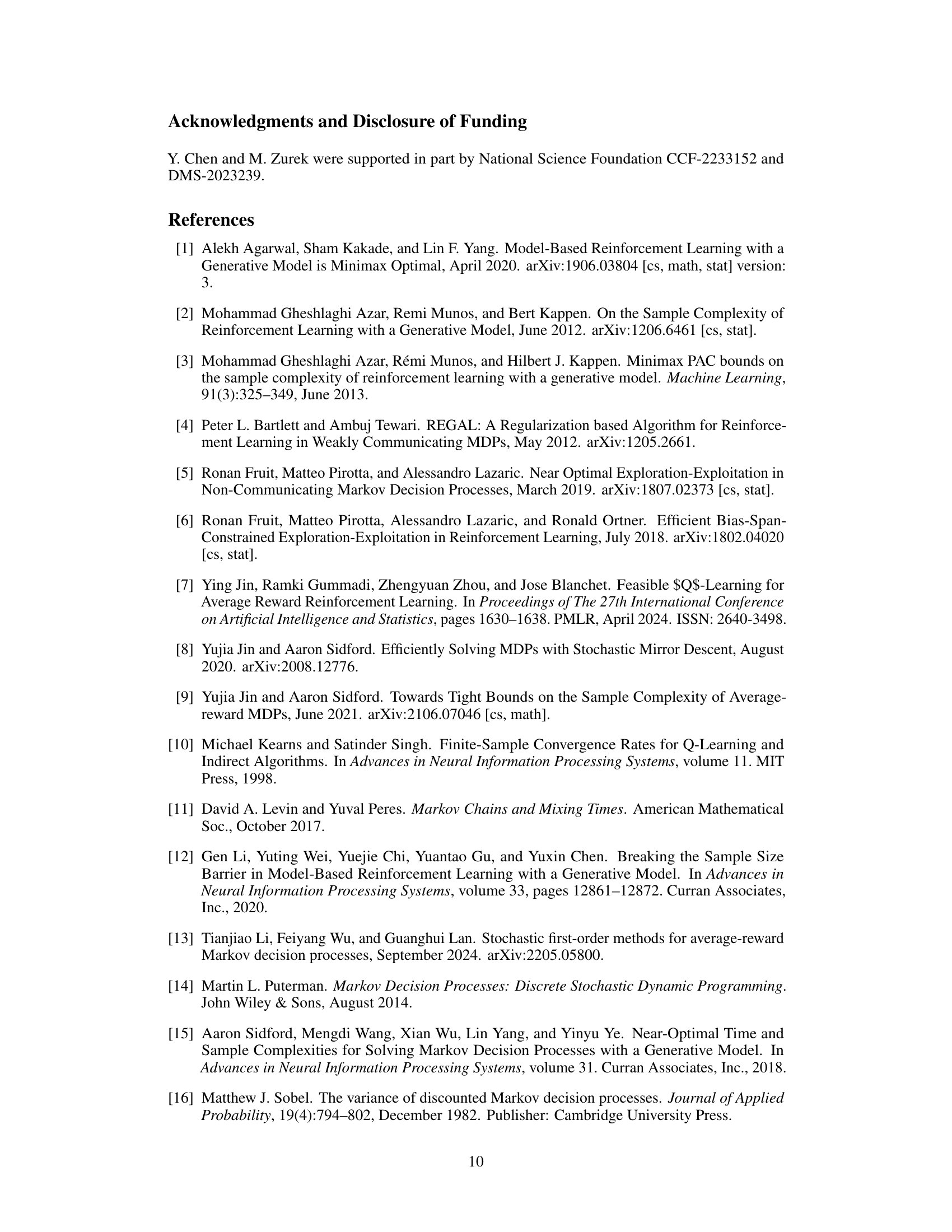

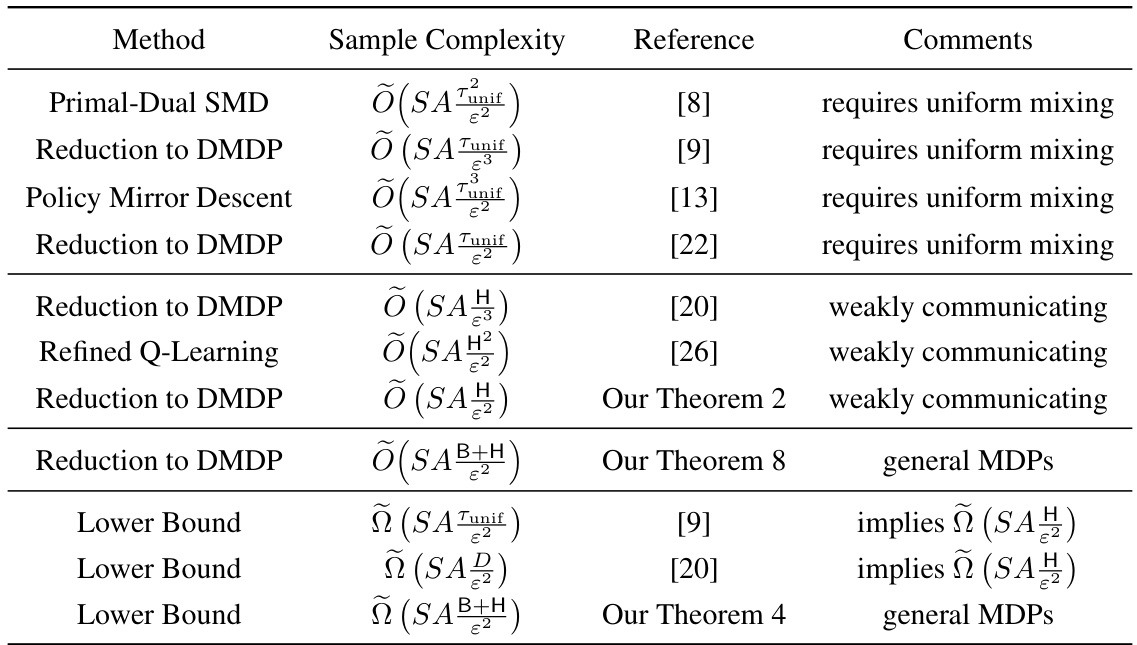

This figure shows two Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). In both MDPs, there are four states and the optimal bias function has a span of 0. The top MDP, M0, has a transition probability of 1/T from state 1 to state 3. The bottom MDP, M1, has a transition probability of (1+2ε)/(2T) from state 1 to state 3. The parameter T controls the expected time before the MDP reaches either a state that gives a reward of 0 or 0.5. This parameter illustrates that the discounted approximation approach for average reward MDPs may fail unless the discount factor is set sufficiently close to 1. This is because transient states (states that are not visited in the long run) can have a significant impact on the long-run performance of the MDP.

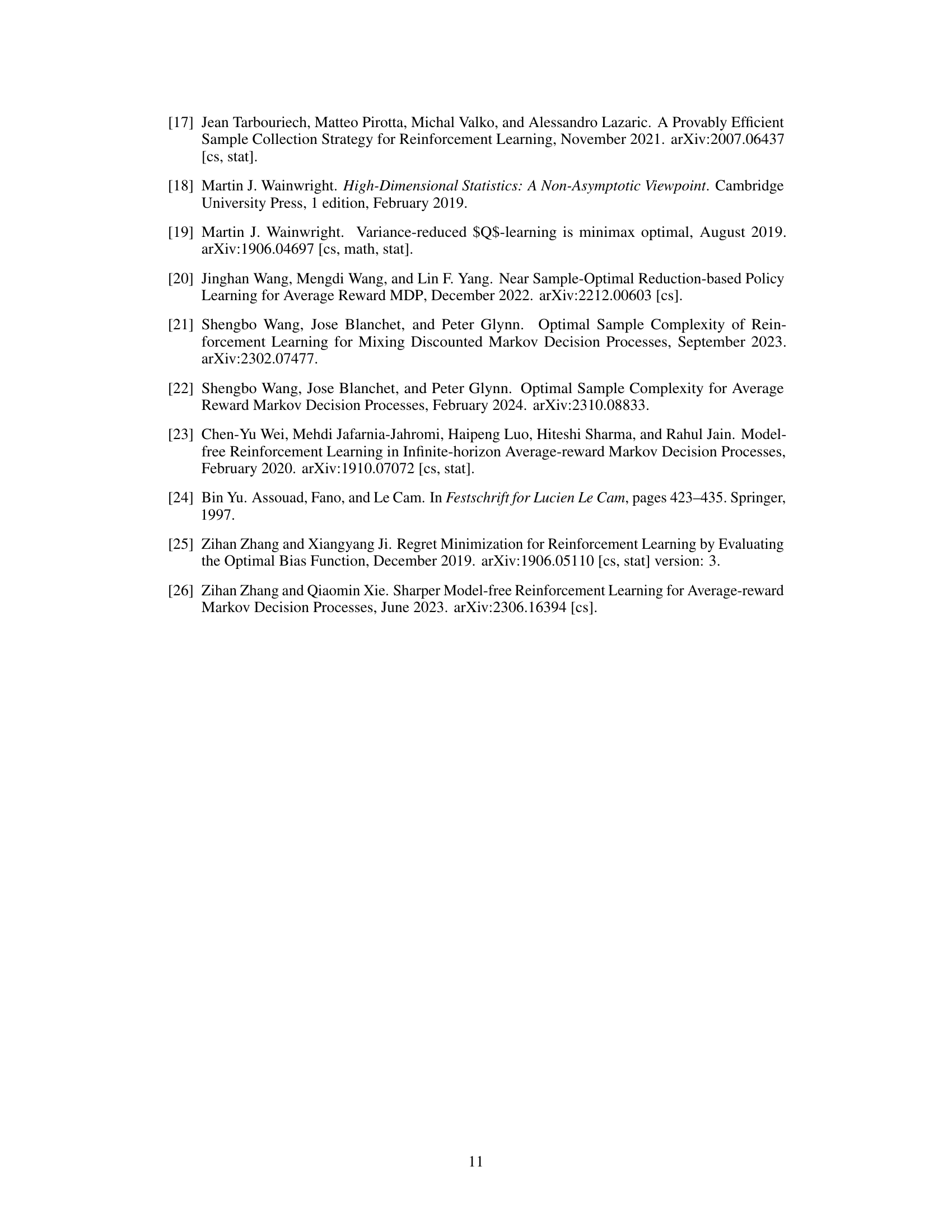

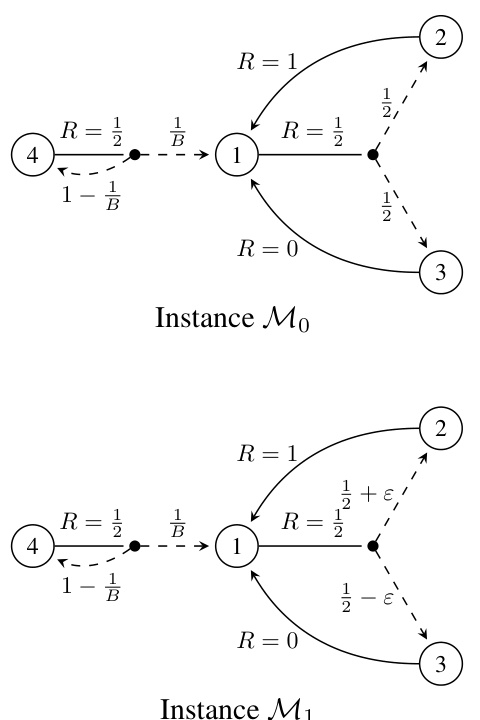

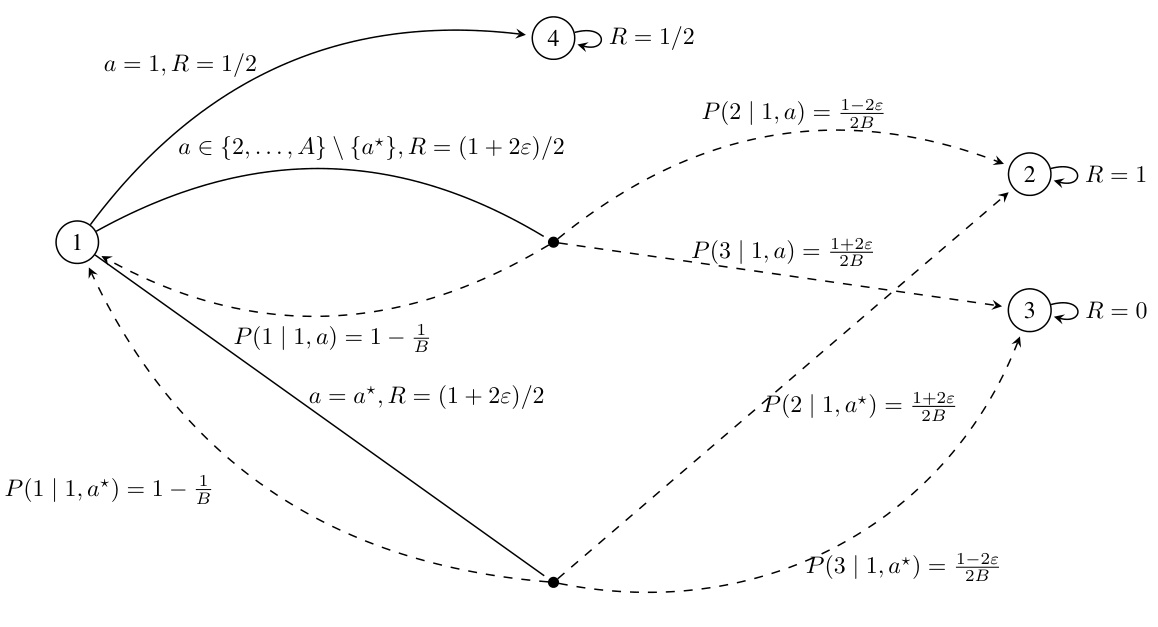

This figure presents the Markov Decision Process (MDP) instances used in the proof of the lower bound presented in Theorem 4. The MDPs, denoted as M1 and Ma* (where a* is an index from 2 to A), are used to demonstrate the statistical hardness of distinguishing between MDPs with different spans of the optimal bias function. The key differences lie in the transition probabilities and reward values associated with the actions taken from state 1, with the goal being to highlight the challenges in identifying the optimal policy and achieving optimal sample complexity without full knowledge of the MDP’s structural properties, like the span of the optimal bias function. The transient time parameter ‘B’ also plays a significant role in the complexity analysis illustrated by these instances.

This figure shows the Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) used to prove the lower bound in Theorem 4 of the paper. The MDPs, denoted as M1 and Ma* (where a* is an action), illustrate a scenario with a transient state (state 1) and multiple absorbing states (states 2, 3, and 4). The key difference between M1 and Ma* lies in the transition probabilities and rewards associated with actions from state 1. This subtle difference in structure is carefully crafted to demonstrate the inherent difficulty in learning near-optimal policies in general average-reward MDPs with limited samples. The complexity of distinguishing between these MDPs based on observed transitions forms the basis of the lower bound.

Full paper#