↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for Unsupervised Environment Design (UED) primarily focus on minimizing regret, overlooking the importance of environment novelty in improving generalization of AI agents. This leads to training curricula that lack diversity and hinder the development of truly robust AI systems. Existing novelty quantification methods suffer from limitations, such as being domain-specific or computationally expensive.

To address this, the paper introduces the Coverage-based Evaluation of Novelty In Environment (CENIE) framework. CENIE leverages the student agent’s state-action space coverage from previous training experiences to quantify novelty. CENIE is scalable, domain-agnostic and curriculum-aware, addressing the shortcomings of previous methods. The integration of CENIE with existing UED algorithms substantially improves zero-shot generalization performance across diverse benchmarks, highlighting the critical role of novelty in curriculum design.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning and unsupervised environment design. It directly addresses the critical challenge of improving generalization in AI agents by introducing a novel framework for quantifying environment novelty. This opens exciting avenues for improving curriculum design methods and advancing the state-of-the-art in training generally capable AI agents. The proposed CENIE framework is domain-agnostic and scalable, making it widely applicable across various AI domains, enhancing the impact and significance of this research. This work is timely, given the recent surge in interest in UED and its importance for tackling the generalization problem in deep reinforcement learning.

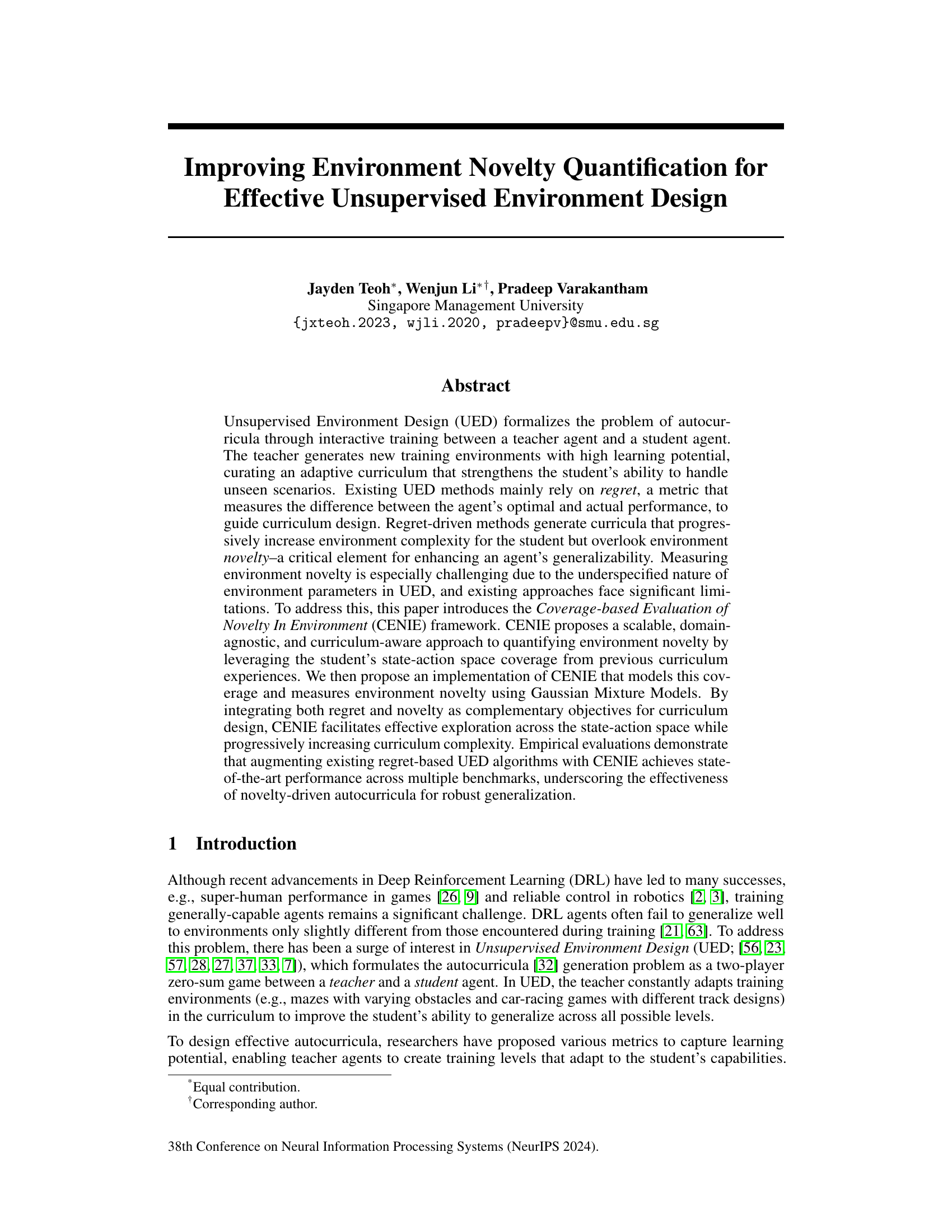

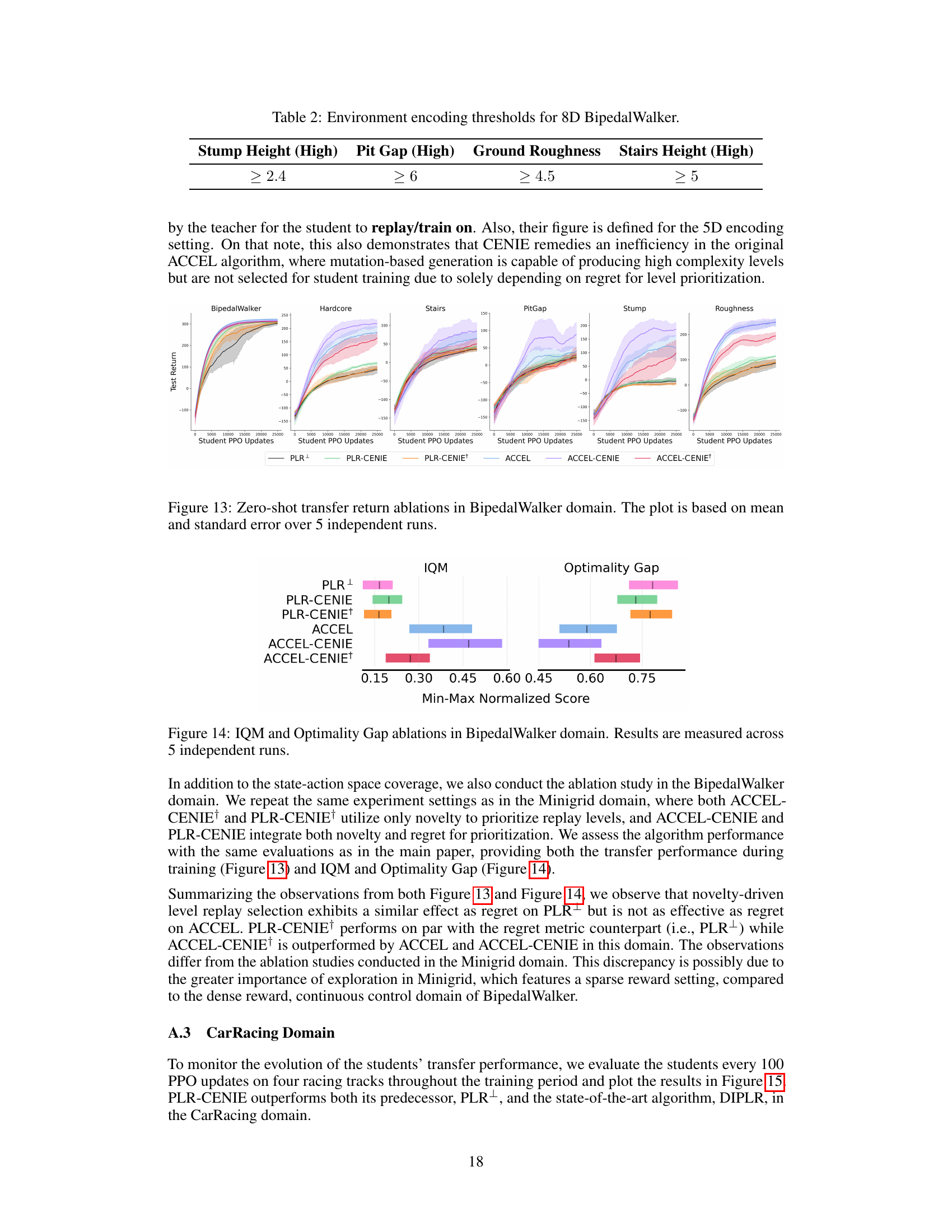

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the CENIE framework, which enhances unsupervised environment design (UED) by incorporating environment novelty alongside traditional regret-based methods for curriculum design. The teacher agent uses both environment regret (measuring the student agent’s performance gap) and environment novelty (quantified by CENIE using state-action coverage) to select and generate new training levels for the student agent. The student agent’s experiences (state-action pairs) are collected and used to update the coverage model (Γ), which is then used by CENIE to evaluate the novelty of new environments. The process is iterative, constantly adapting the curriculum based on the student’s progress and the novelty of available environments.

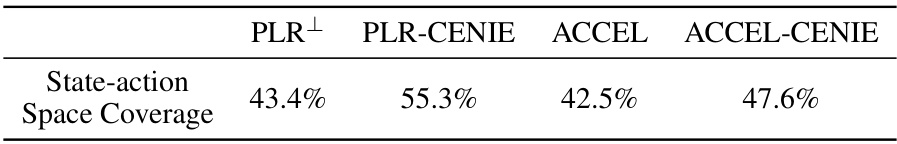

This table presents the state-action space coverage achieved by four different algorithms (PLR+, PLR-CENIE, ACCEL, ACCEL-CENIE) after 30,000 Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) updates in the BipedalWalker environment. State-action space coverage is a measure of how much of the state-action space the agent has explored during training. Higher coverage generally indicates better generalization. The table shows that the algorithms incorporating CENIE (PLR-CENIE and ACCEL-CENIE) achieve significantly higher state-action space coverage than their counterparts without CENIE (PLR+ and ACCEL).

In-depth insights#

Novelty in UED#

In Unsupervised Environment Design (UED), novelty plays a crucial role in enhancing the generalizability of reinforcement learning (RL) agents. Existing UED methods often focus primarily on regret minimization, overlooking the importance of introducing novel training environments. Novelty ensures that the agent encounters diverse scenarios, preventing overfitting to specific aspects of the training curriculum and improving the agent’s ability to handle unseen situations. However, quantifying novelty in UED is challenging. The underspecified nature of environment parameters makes it difficult to define novelty in an absolute sense, since environment characteristics are not known beforehand. Thus, a key contribution is to propose approaches that model and compare the agent’s state-action space coverage from previous training experiences, to define and quantify environment novelty. By integrating both regret and novelty objectives in the curriculum design, UED algorithms are improved with enhanced exploration and robustness. The framework presented achieves state-of-the-art results across multiple benchmarks by dynamically optimizing for both regret and novelty, effectively driving the agent towards unfamiliar state-action space regions while progressing through increasing complexity. The approach uses Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) to model the student agent’s state-action coverage, demonstrating scalability and domain-agnosticism. This addresses limitations of previous methods that relied on computationally intensive techniques or were limited to specific problem domains.

CENIE Framework#

The CENIE framework offers a novel approach to quantifying environment novelty in unsupervised environment design (UED). Instead of relying solely on regret, CENIE leverages the student agent’s state-action space coverage from past experiences to evaluate the novelty of new environments. This curriculum-aware approach is domain-agnostic and scalable, overcoming limitations of previous methods. By modeling state-action space coverage using Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), CENIE provides a quantitative measure of novelty that complements regret-based objectives. The integration of both novelty and regret facilitates exploration across the state-action space while increasing curriculum complexity, leading to improved generalization. CENIE’s flexibility allows for integration with existing UED algorithms, enhancing their performance and underscoring the importance of novelty for robust generalization in reinforcement learning.

GMM Implementation#

A robust GMM implementation for quantifying environment novelty is crucial for the success of the proposed CENIE framework. The choice of GMMs offers advantages like scalability in handling high-dimensional data. Careful consideration of model parameters, such as the number of Gaussian components, is needed to balance model complexity and representational accuracy. The use of the Expectation-Maximization algorithm presents a computationally efficient approach for parameter estimation. The implementation should include steps to address challenges such as ensuring convergence of the EM algorithm and dealing with the curse of dimensionality. Strategies for initial parameter setting, such as k-means++, significantly impact model performance and should be carefully chosen. The implementation should be evaluated across various benchmarks and domains to ensure its reliability and robustness in diverse settings. Addressing computational limitations, such as the use of efficient algorithms and potentially dimensionality reduction techniques, is also essential for a practical implementation.

Zero-Shot Transfer#

Zero-shot transfer, a crucial aspect of artificial intelligence, focuses on evaluating the capability of a model trained on a specific set of tasks to generalize to entirely new, unseen tasks without any additional training. This capability is paramount for creating truly robust and adaptable AI systems. The paper likely investigates zero-shot transfer performance as a key metric to assess the efficacy of its proposed unsupervised environment design (UED) method. High zero-shot transfer performance indicates that the UED approach successfully equips the agent with the ability to tackle novel situations. This suggests that the learning process facilitated by the UED method is not limited to the specific environments experienced during training, but promotes a broader understanding applicable to a much wider range of scenarios. The paper likely presents empirical results demonstrating the superiority of its UED method over existing approaches in terms of zero-shot transfer performance across various benchmark tasks, validating its effectiveness. This improvement likely stems from the UED method’s ability to incorporate environment novelty, an element that traditional methods often overlook.

Future of CENIE#

The CENIE framework, while promising, has room for expansion. Future research should explore alternative methods for modeling state-action space coverage beyond Gaussian Mixture Models, potentially leveraging more sophisticated techniques to handle high-dimensionality and complex data distributions. Incorporating techniques from novelty search and open-endedness would allow CENIE to generate truly novel and interesting environments, rather than simply prioritizing existing ones. Addressing the challenge of regret stagnation remains crucial, as solely relying on novelty might not provide sufficient learning pressure. Finally, the impact of different weighting schemes between novelty and regret needs investigation to identify optimal balancing strategies across diverse domains and task complexities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

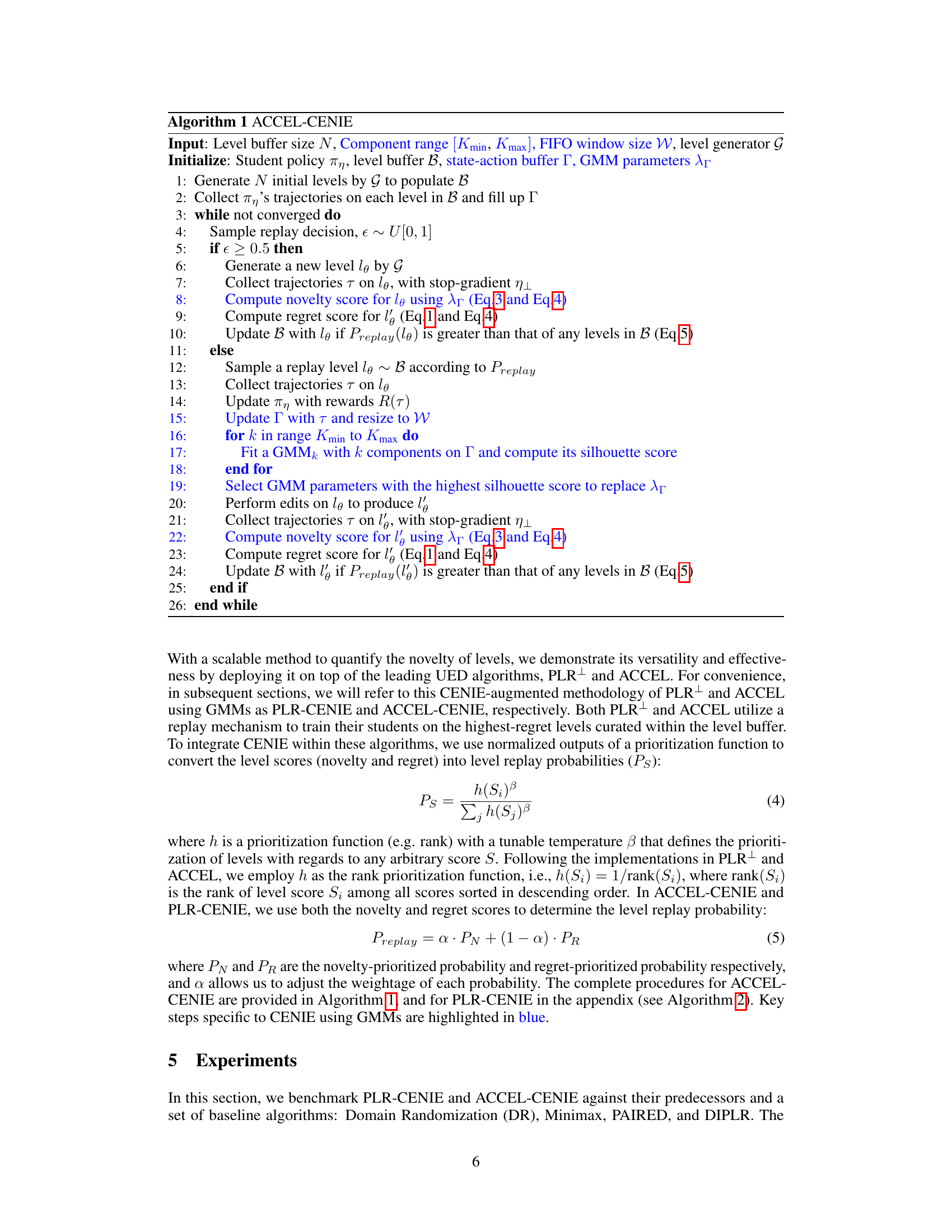

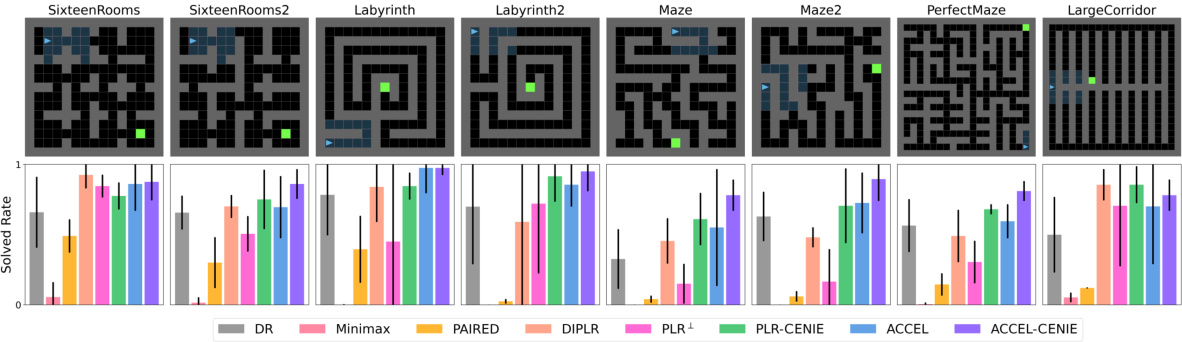

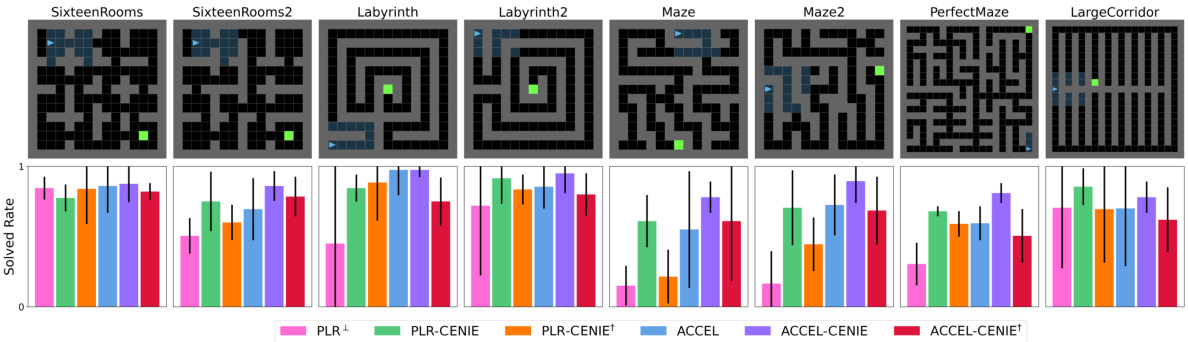

This figure shows the zero-shot transfer performance of different unsupervised environment design (UED) algorithms on eight different Minigrid environments. Each bar represents the percentage of times each algorithm successfully solved each environment, showing the median solved rate and the interquartile range (IQR) across 5 independent runs. The figure highlights the relative performance of each algorithm in terms of its ability to generalize to unseen environments after training on a curriculum generated by the respective UED method.

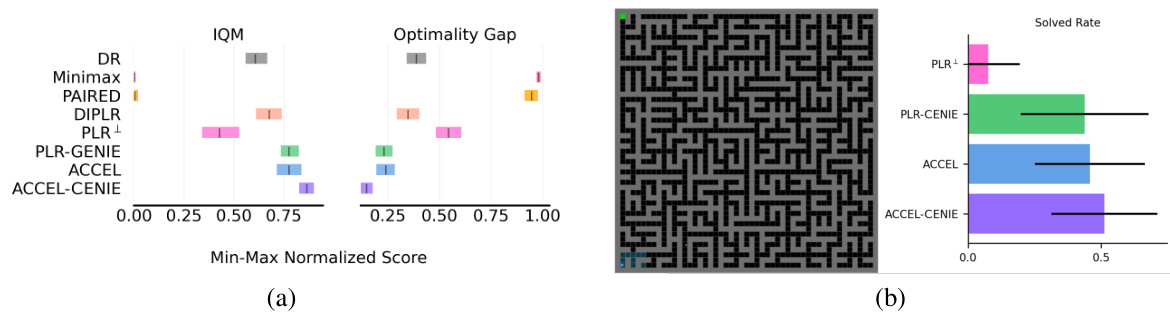

This figure shows the zero-shot transfer performance results of different algorithms on two Minigrid tasks. (a) displays the aggregate performance across 8 standard Minigrid environments; (b) shows results on a significantly larger and more complex environment, PerfectMazeLarge, to test generalization. ACCEL-CENIE consistently outperforms other algorithms, particularly on the more challenging PerfectMazeLarge environment, showcasing the effectiveness of integrating novelty into curriculum design.

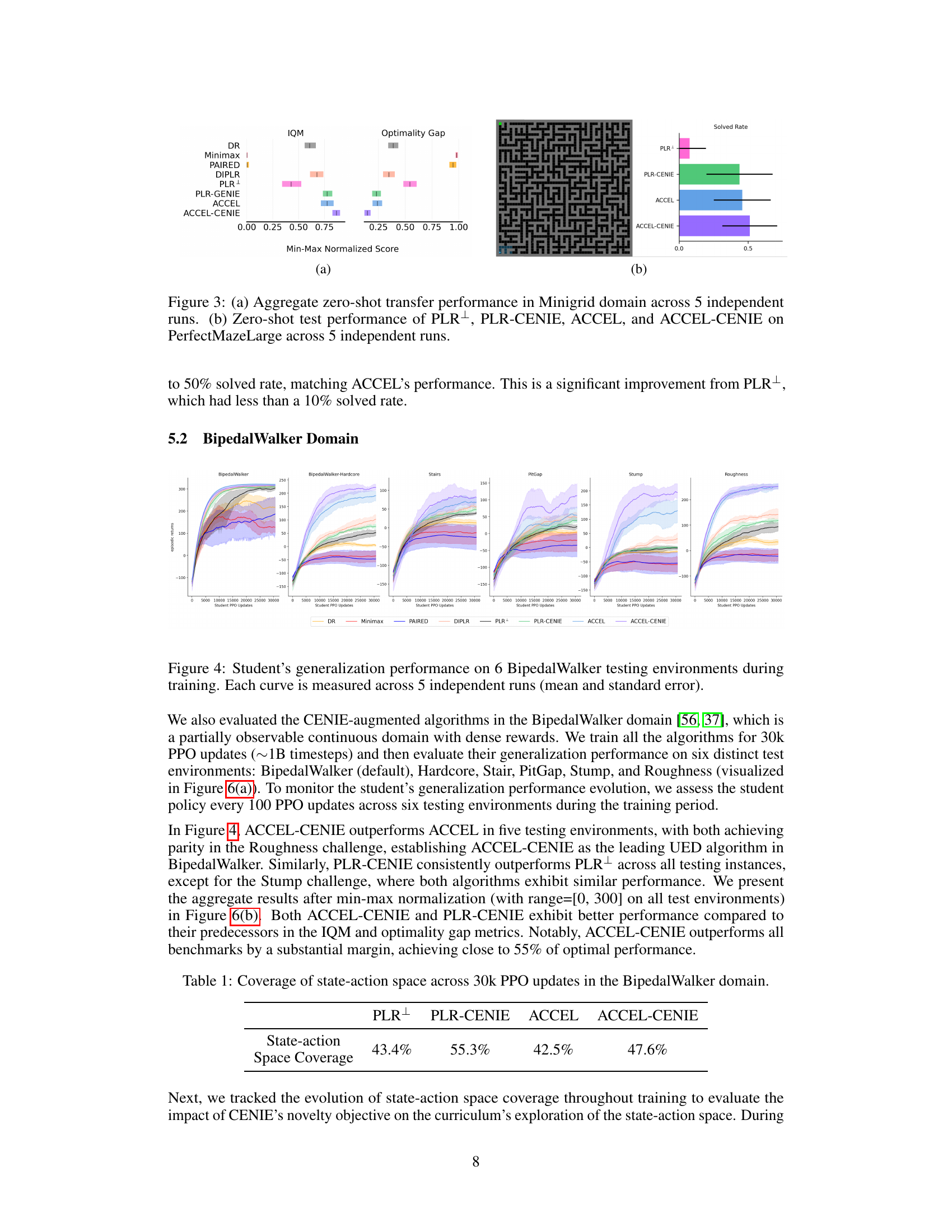

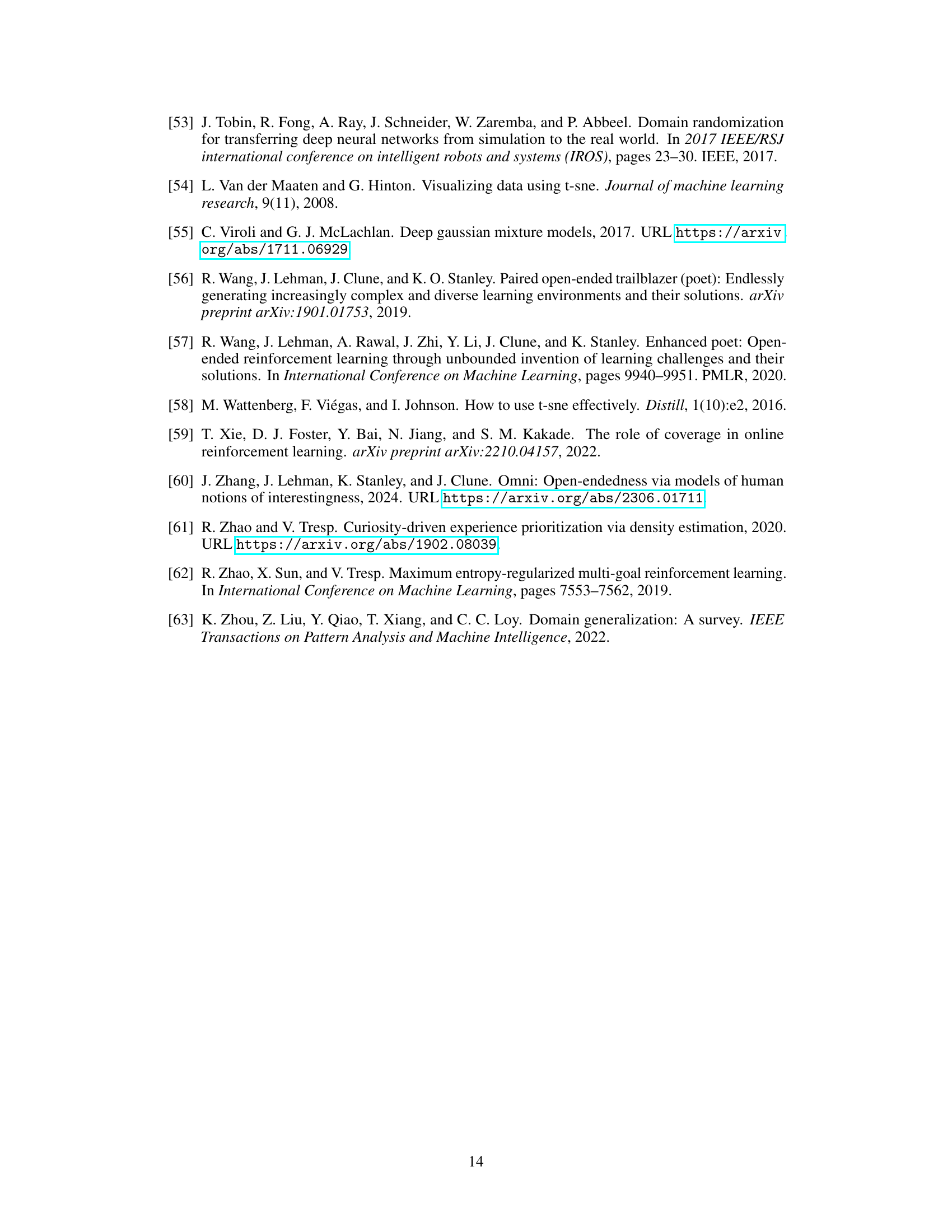

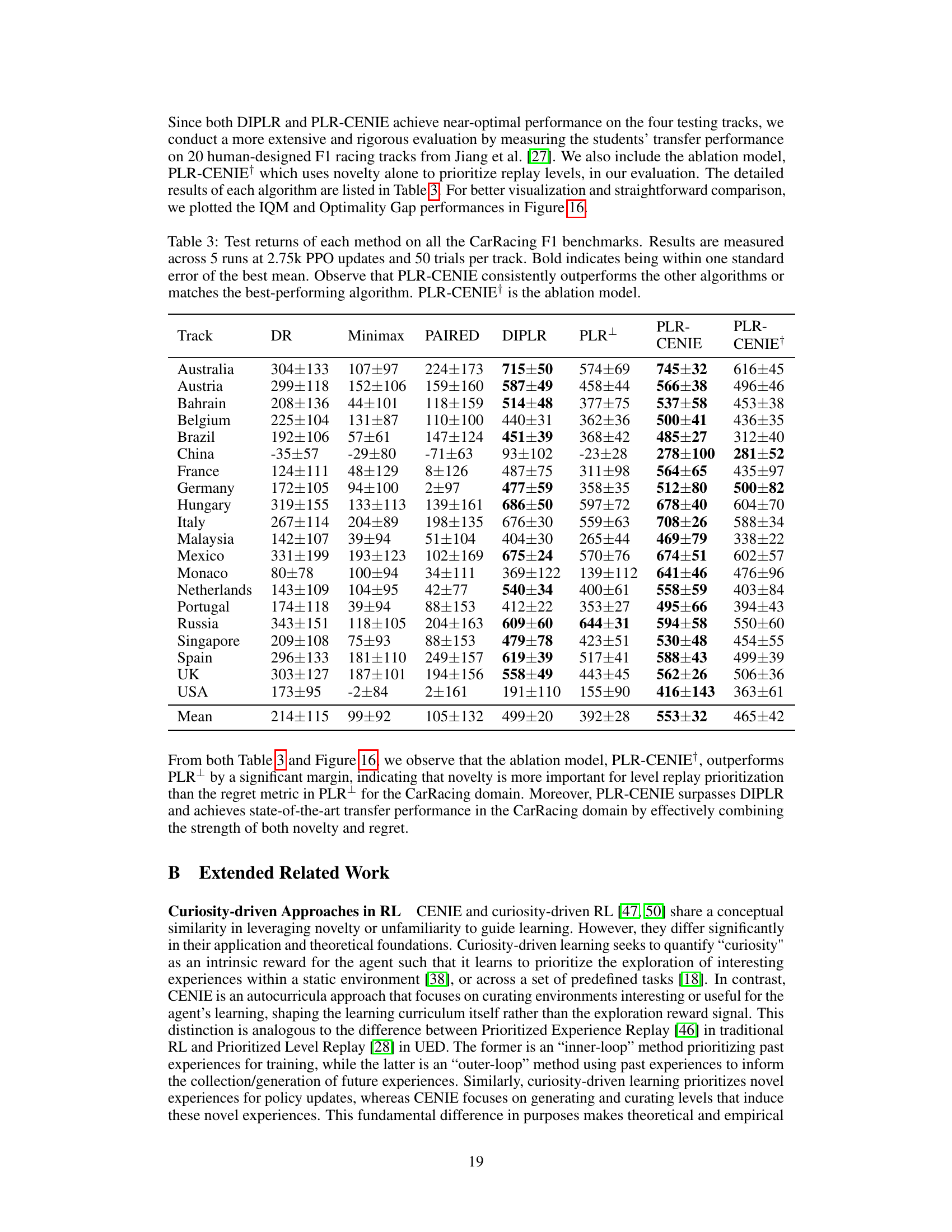

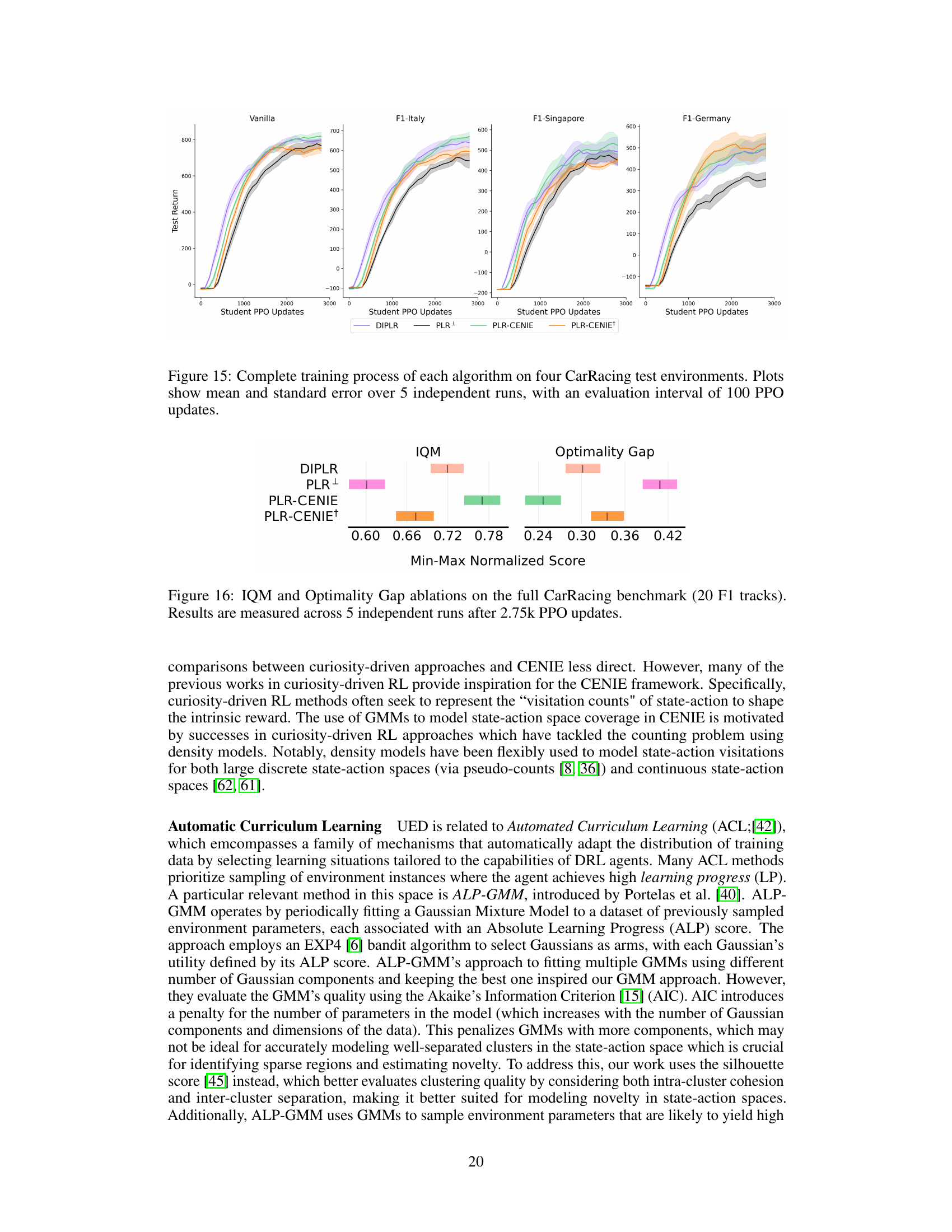

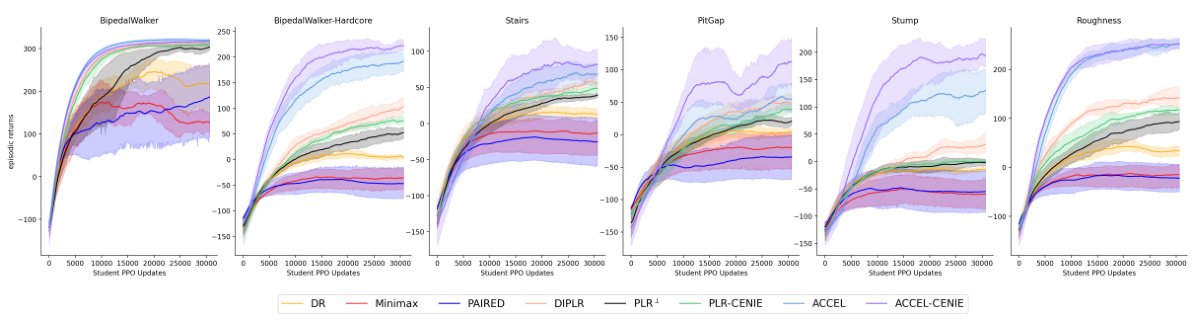

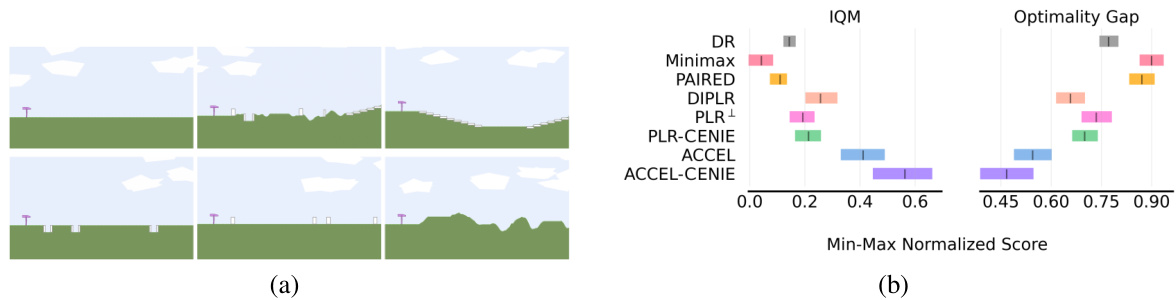

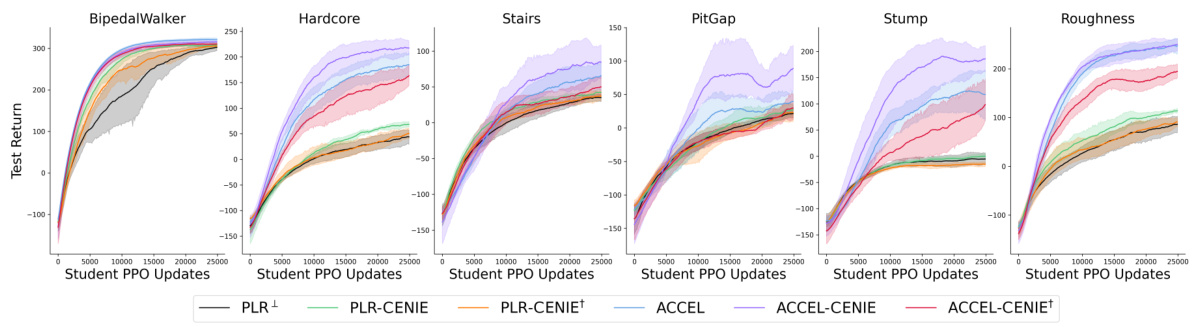

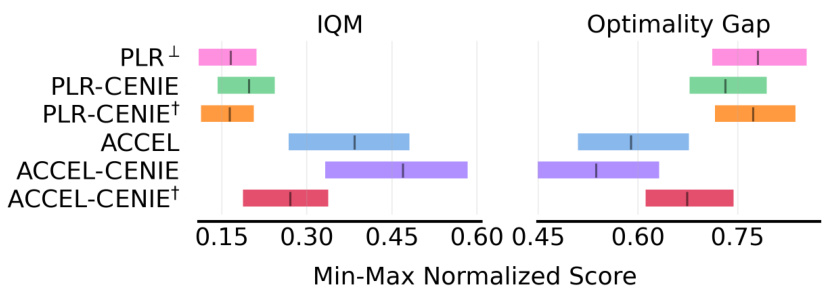

This figure displays the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms on six variations of the BipedalWalker environment over 30,000 training updates. Each line represents the average performance of an algorithm across five independent runs, with error bars indicating the standard error. The x-axis shows the number of training updates, and the y-axis represents the episodic return, a measure of the agent’s performance in each episode. The figure allows for comparison of how different algorithms generalize to unseen environments during the training process.

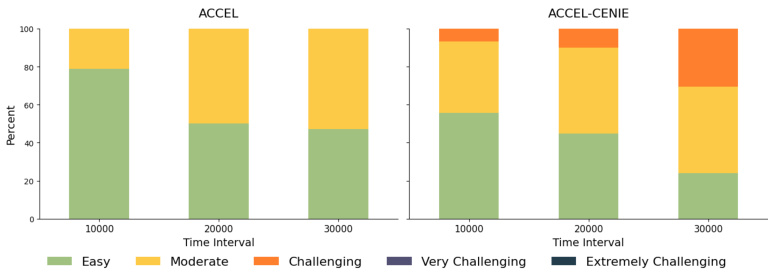

This figure compares the distribution of level difficulties replayed by ACCEL and ACCEL-CENIE across different training intervals. The difficulty is categorized into five levels: Easy, Moderate, Challenging, Very Challenging, and Extremely Challenging. The figure shows that ACCEL predominantly replays easy to moderate levels, while ACCEL-CENIE progressively incorporates more challenging levels throughout training, demonstrating how the addition of CENIE’s novelty objective affects the curriculum’s difficulty.

This figure displays the zero-shot transfer performance results of different algorithms on two Minigrid tasks. (a) shows the aggregated performance on various standard Minigrid environments. (b) specifically tests the algorithms’ generalization capability on a much larger, more complex environment (PerfectMazeLarge), demonstrating their ability to transfer knowledge to unseen, significantly more difficult scenarios. The results indicate that the algorithms augmented with CENIE achieve superior performance compared to their counterparts without CENIE, highlighting the effectiveness of the CENIE framework in improving generalization.

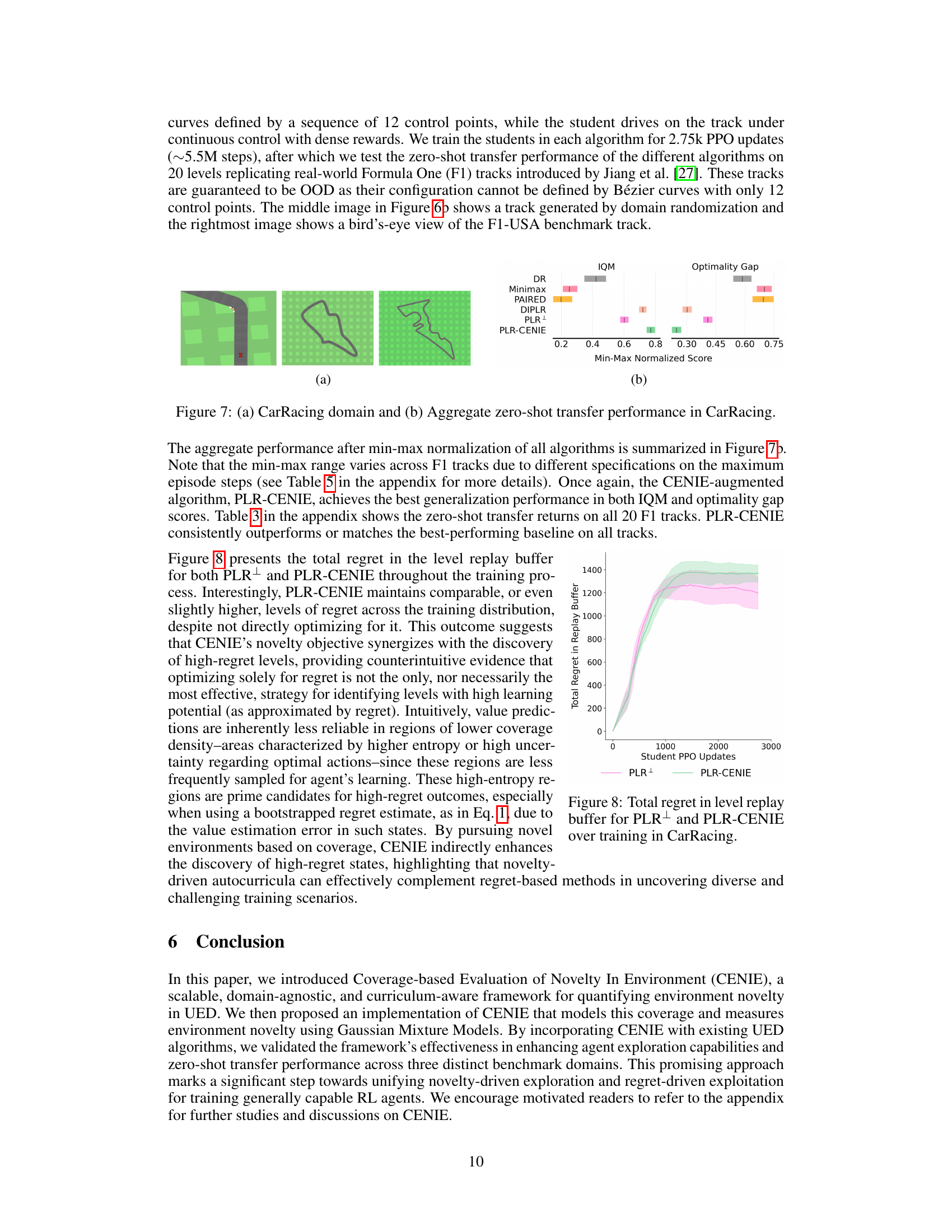

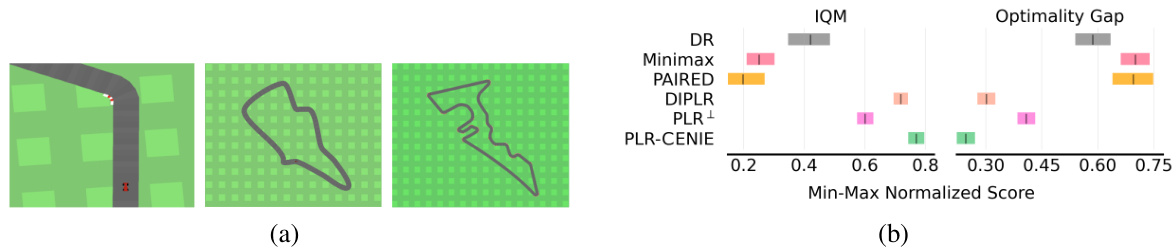

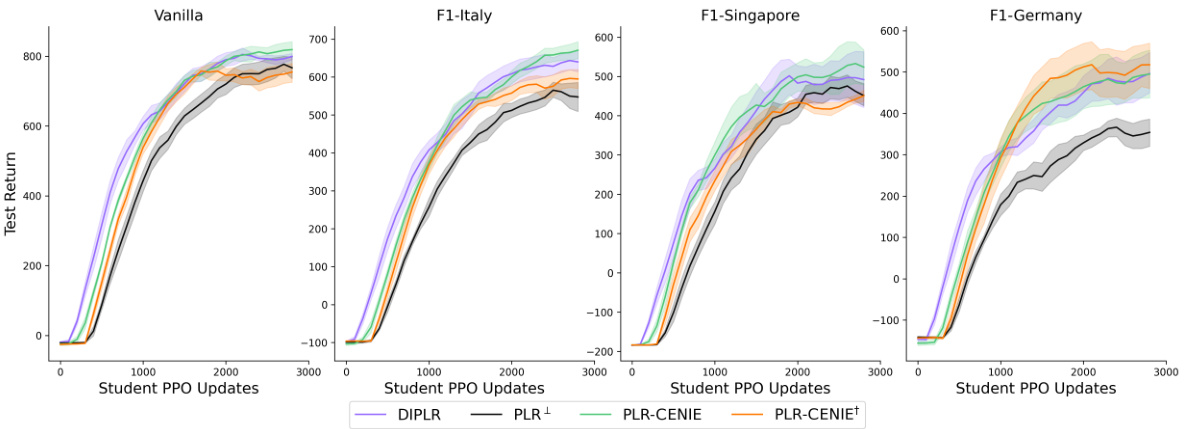

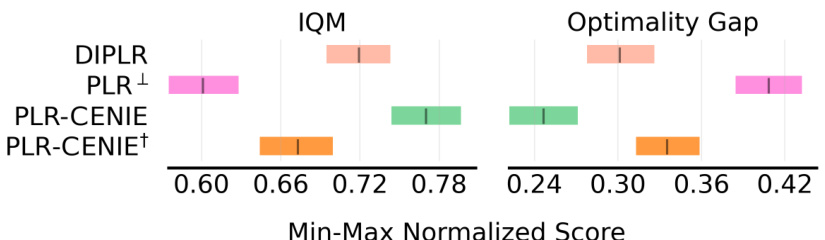

Figure 7(a) shows examples of the CarRacing environment. Figure 7(b) shows the performance of different algorithms on the CarRacing benchmark (20 F1 tracks). PLR-CENIE achieves the best generalization performance in terms of both IQM and optimality gap scores, consistently outperforming or matching the best-performing baseline on all tracks.

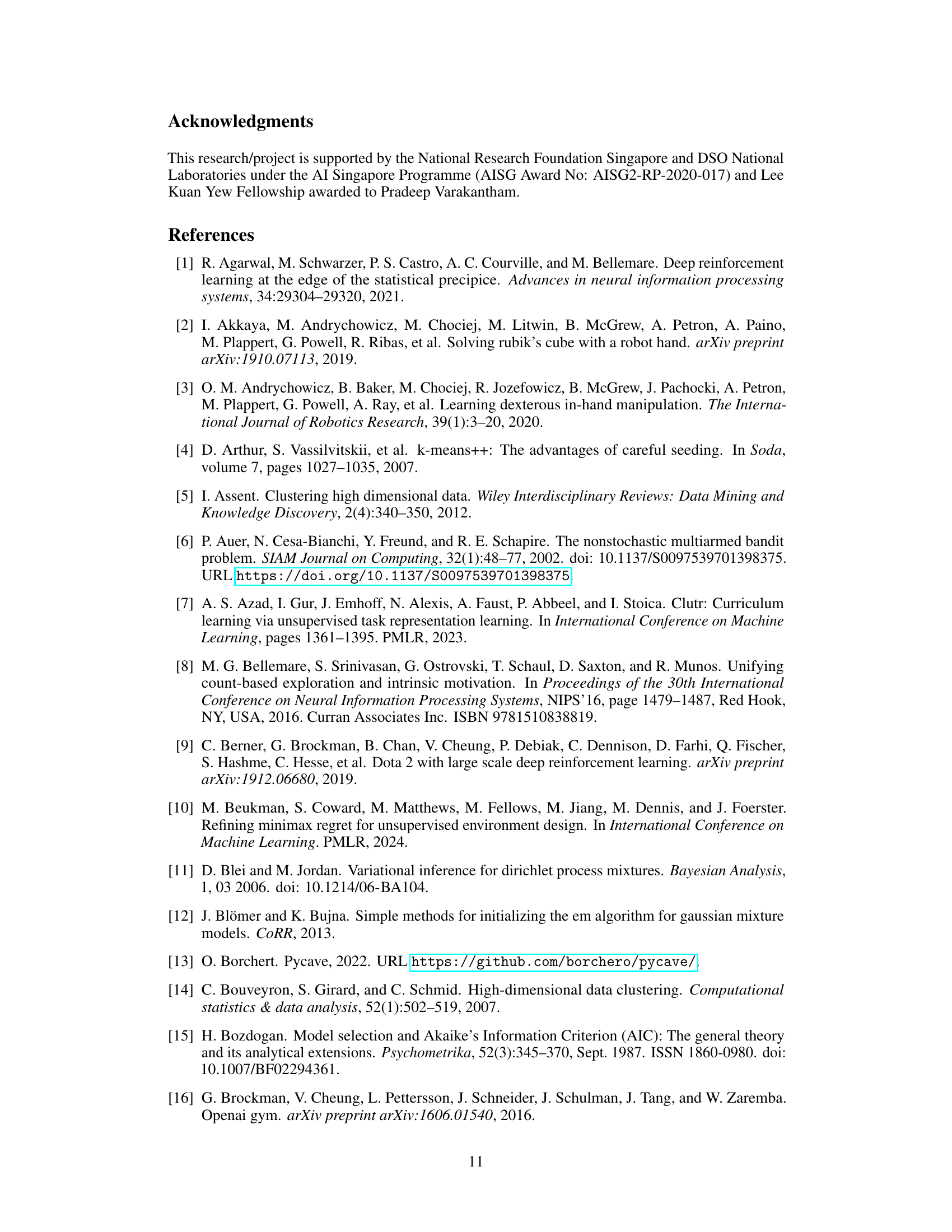

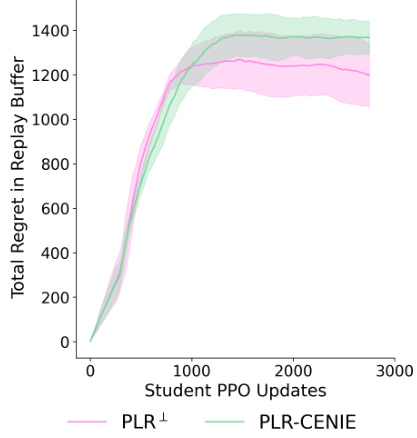

This figure shows the total regret in the level replay buffer for both PLR+ and PLR-CENIE throughout the training process in the CarRacing environment. It demonstrates that although PLR-CENIE doesn’t directly optimize for regret, it maintains comparable or even slightly higher levels of regret throughout training. This suggests that the novelty objective in CENIE synergizes with the discovery of high-regret levels, indicating that optimizing solely for regret isn’t always the most effective strategy for finding levels with significant learning potential.

This figure displays the zero-shot transfer performance of different algorithms (PLR+, PLR-CENIE, PLR-CENIE†, ACCEL, ACCEL-CENIE, and ACCEL-CENIE†) across eight distinct Minigrid environments. Each bar represents the solved rate (percentage of successful completions) for a given algorithm in each environment. Error bars indicate the variability in performance across five independent runs. The results show a comparison between algorithms using only regret, algorithms using only novelty, and algorithms that use both metrics. The figure demonstrates that combining regret and novelty can enhance performance on the Minigrid environments.

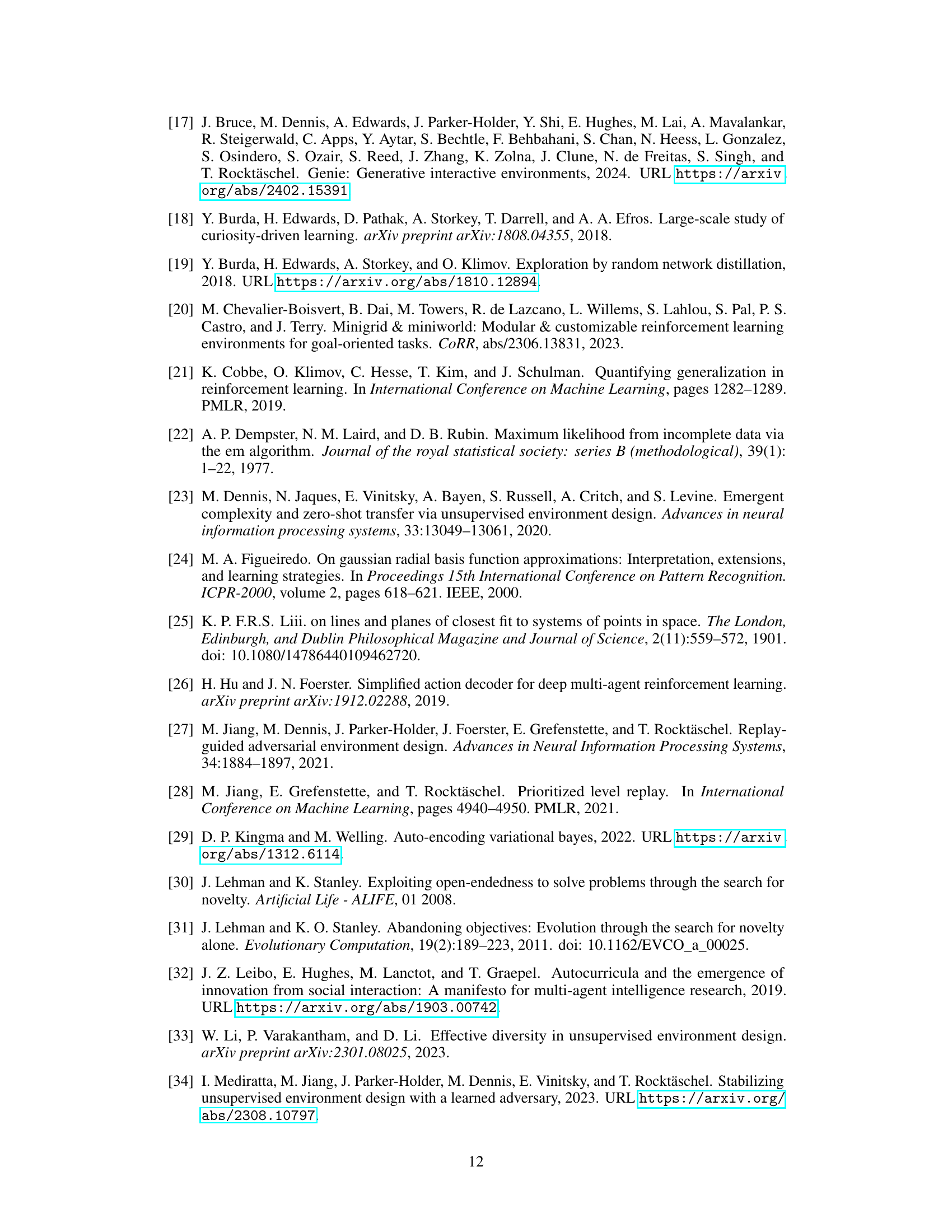

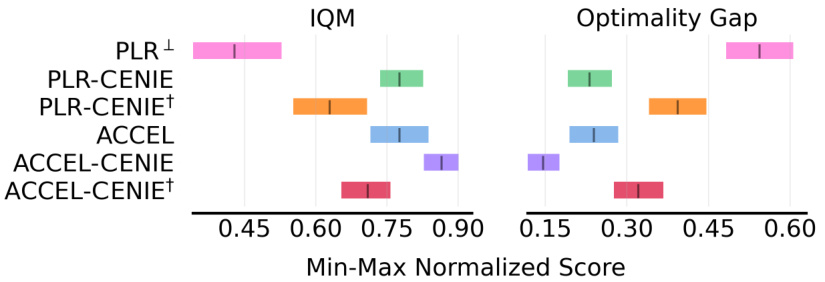

This figure shows the results of ablation studies conducted in the Minigrid domain. Specifically, it compares the performance of different algorithms in terms of Interquartile Mean (IQM) and Optimality Gap. The algorithms compared include PLR+, PLR-CENIE (combining regret and novelty), PLR-CENIE+ (using only novelty), ACCEL, ACCEL-CENIE (combining regret and novelty), and ACCEL-CENIE+ (using only novelty). The x-axis represents the min-max normalized score, and the y-axis shows the algorithms. The purpose of the figure is to demonstrate the individual and combined effects of regret and novelty on the performance of the algorithms in the Minigrid environment.

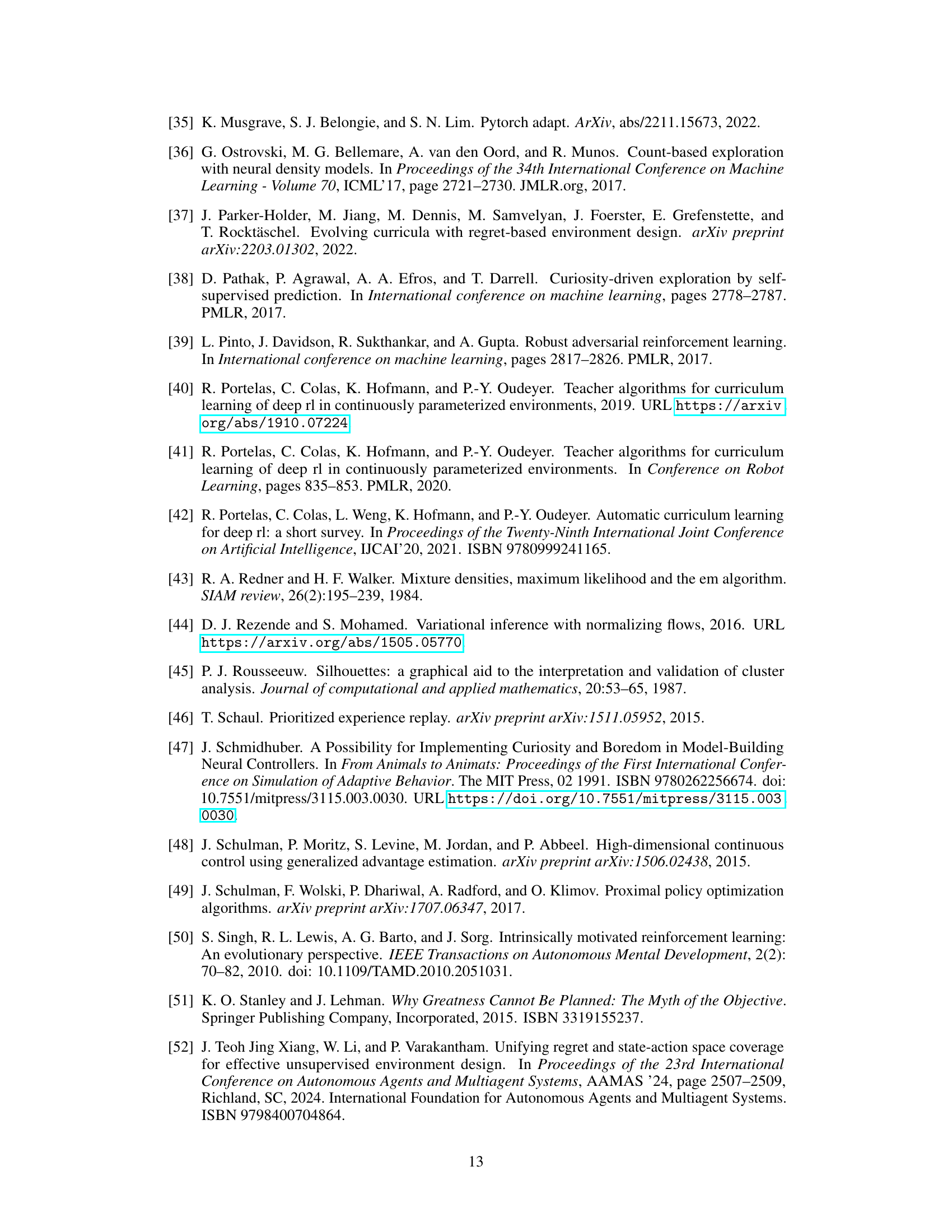

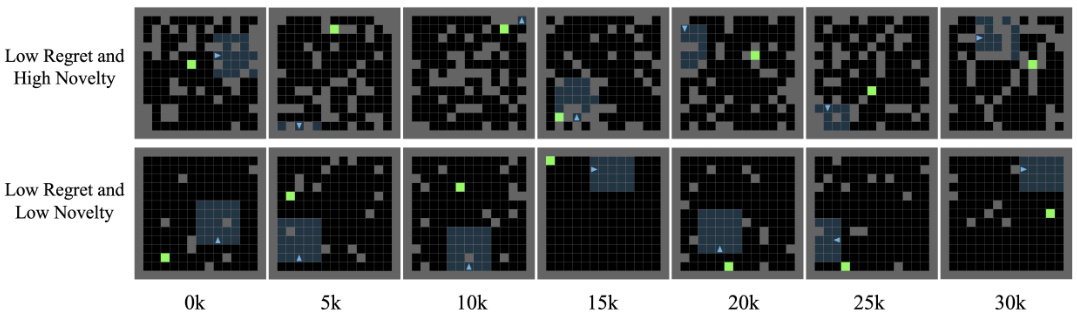

This figure shows a qualitative analysis of the effect of the novelty metric on the level replay buffer of PLR-CENIE in Minigrid. It highlights levels that have the lowest regret (bottom 10) yet exhibit the highest novelty (top 10) and vice versa. Visually, it is shown that levels with high novelty and low regret present complex and diverse scenarios. In contrast, the levels with low regret and low novelty often resemble simple, empty mazes. This demonstrates that incorporating novelty alongside regret enhances the ability to identify levels that present more interesting trajectories (experiences) for the student to learn from.

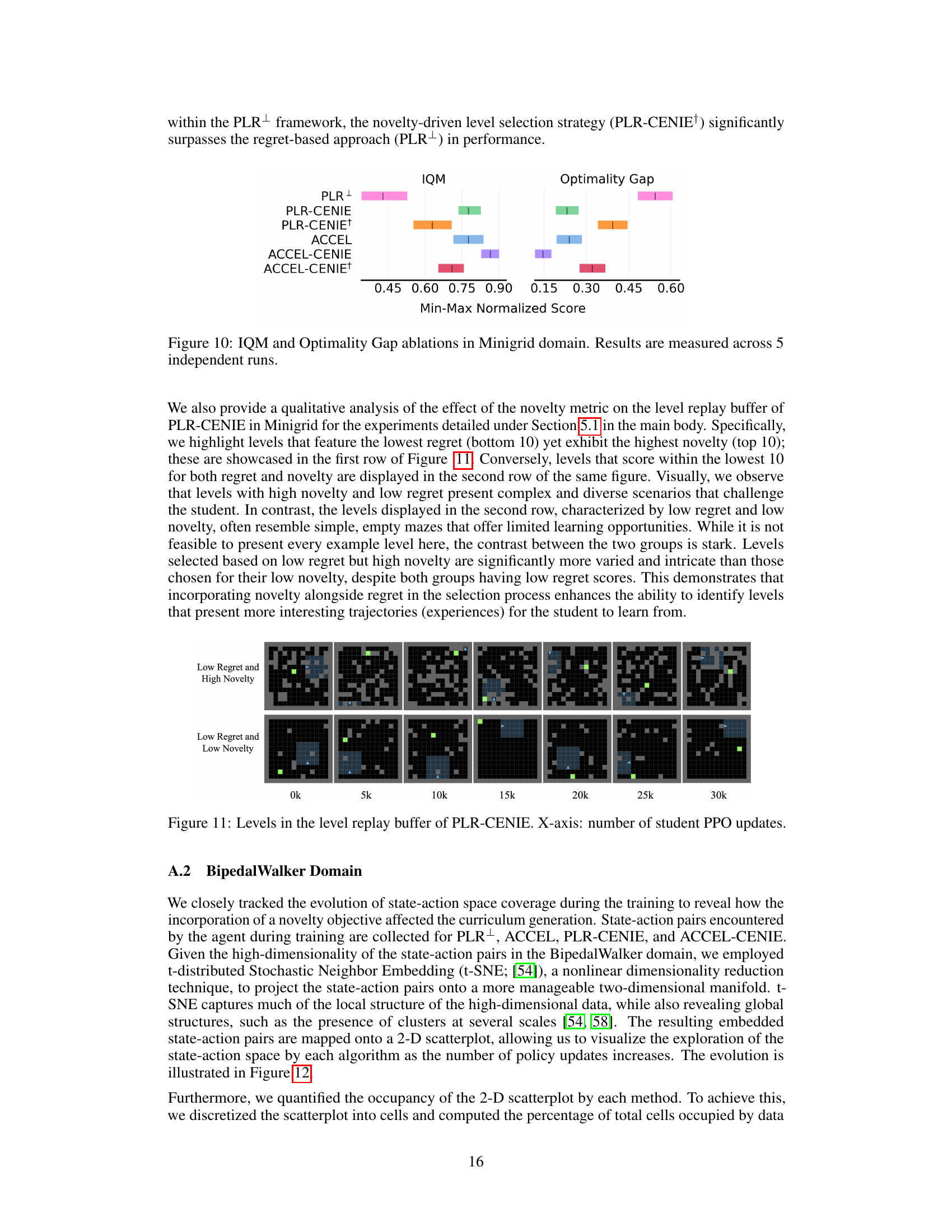

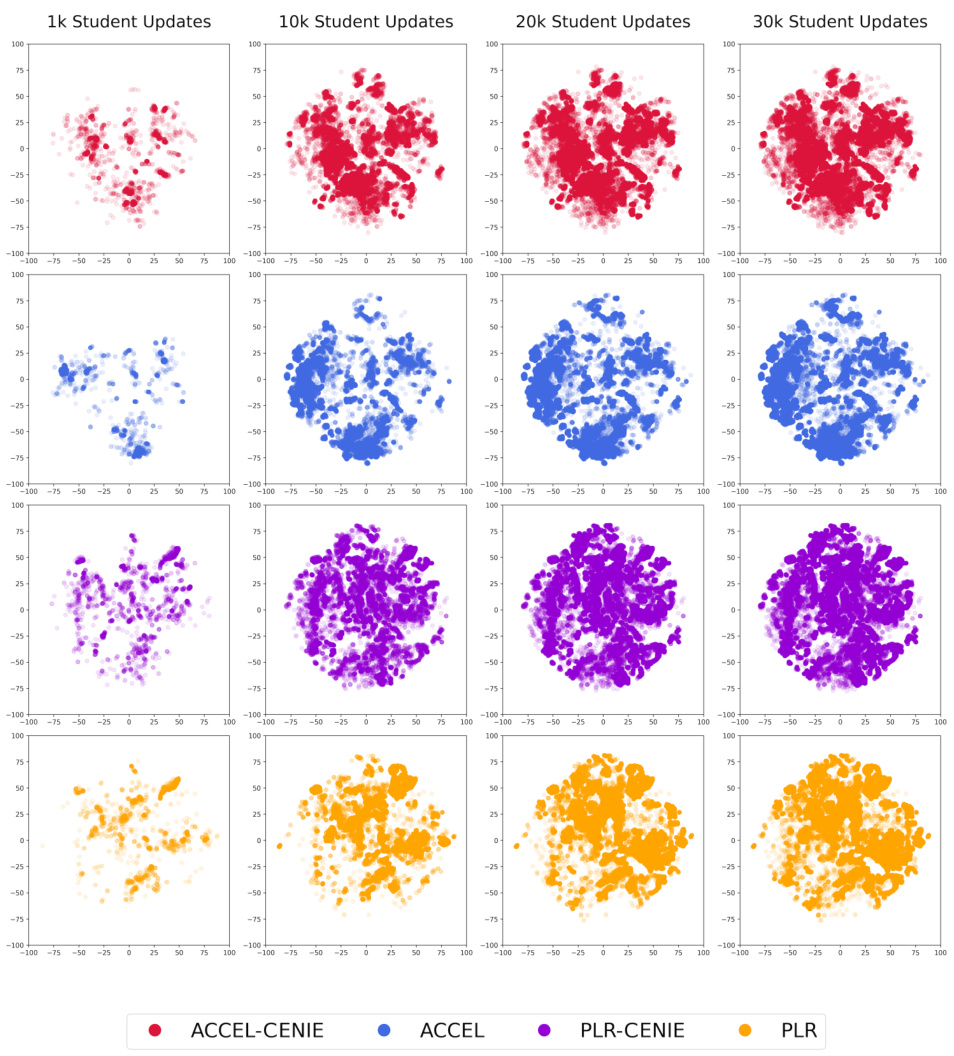

This figure visualizes the evolution of state-action space coverage for four different algorithms (ACCEL-CENIE, ACCEL, PLR-CENIE, and PLR) across four different checkpoints (1k, 10k, 20k, and 30k policy updates). Each subplot shows the distribution of state-action pairs in a two-dimensional space obtained using t-SNE. The evolution of the coverage across checkpoints highlights how different algorithms explore the state-action space throughout the training process. The change in the distribution of points demonstrates the different exploration strategies used by the algorithms and how the inclusion of CENIE influences the space covered.

This figure shows the performance of different algorithms (PLR+, PLR-CENIE, ACCEL, ACCEL-CENIE) across six different testing environments in the BipedalWalker domain over 30,000 PPO updates. The y-axis represents the student agent’s performance (test return), while the x-axis shows the number of PPO updates during training. Error bars represent standard errors across 5 independent runs. It demonstrates the generalization ability of the algorithms across different environments and how CENIE improves generalization performance compared to its counterpart algorithms without CENIE.

This figure shows the performance comparison of different algorithms in the Minigrid domain. Specifically, it compares the performance of PLR+, PLR-CENIE, PLR-CENIE+ (using only novelty for prioritization), ACCEL, ACCEL-CENIE, and ACCEL-CENIE+ (using only novelty for prioritization). The results are shown in terms of Interquartile Mean (IQM) and Optimality Gap, both of which are normalized. The purpose is to evaluate the individual contribution of regret and novelty in shaping curricula for better generalization performance.

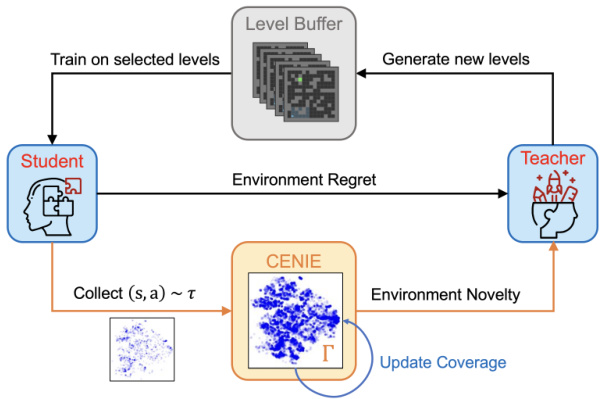

This figure shows the training curves of four different algorithms (DIPLR, PLR+, PLR-CENIE, and PLR-CENIE†) on four different CarRacing test environments. Each curve represents the average test return over five independent runs. The evaluation interval is every 100 PPO updates. The shaded areas represent the standard error. This figure is used to visually compare the learning curves and the final performance of each algorithm on the selected testing tracks.

This figure shows the ablation study results comparing the performance of different algorithms in the Minigrid environment. Specifically, it compares the performance of algorithms using only novelty (PLR-CENIE†, ACCEL-CENIE†) versus those that combine novelty and regret (PLR-CENIE, ACCEL-CENIE) for level selection in the curriculum. The Interquartile Mean (IQM) and Optimality Gap are shown to demonstrate the impact of using both novelty and regret on the overall performance and how the algorithms compare in terms of achieving a desired target.

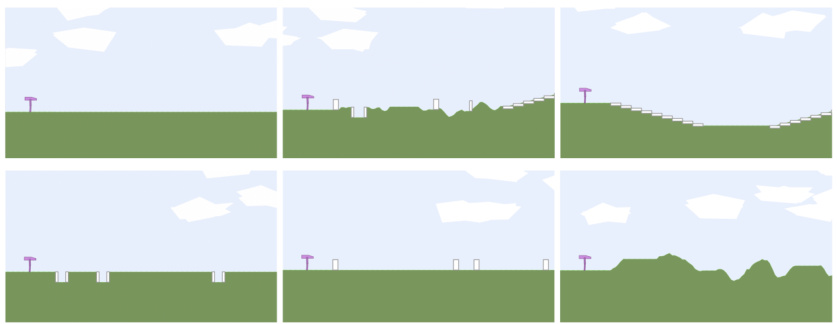

This figure shows six example testing levels from the BipedalWalker domain used to evaluate the generalization performance of the trained agents. Each subfigure represents a different level with varying difficulty, showcasing diverse terrain types such as flat ground, stairs, gaps, and uneven surfaces.

More on tables

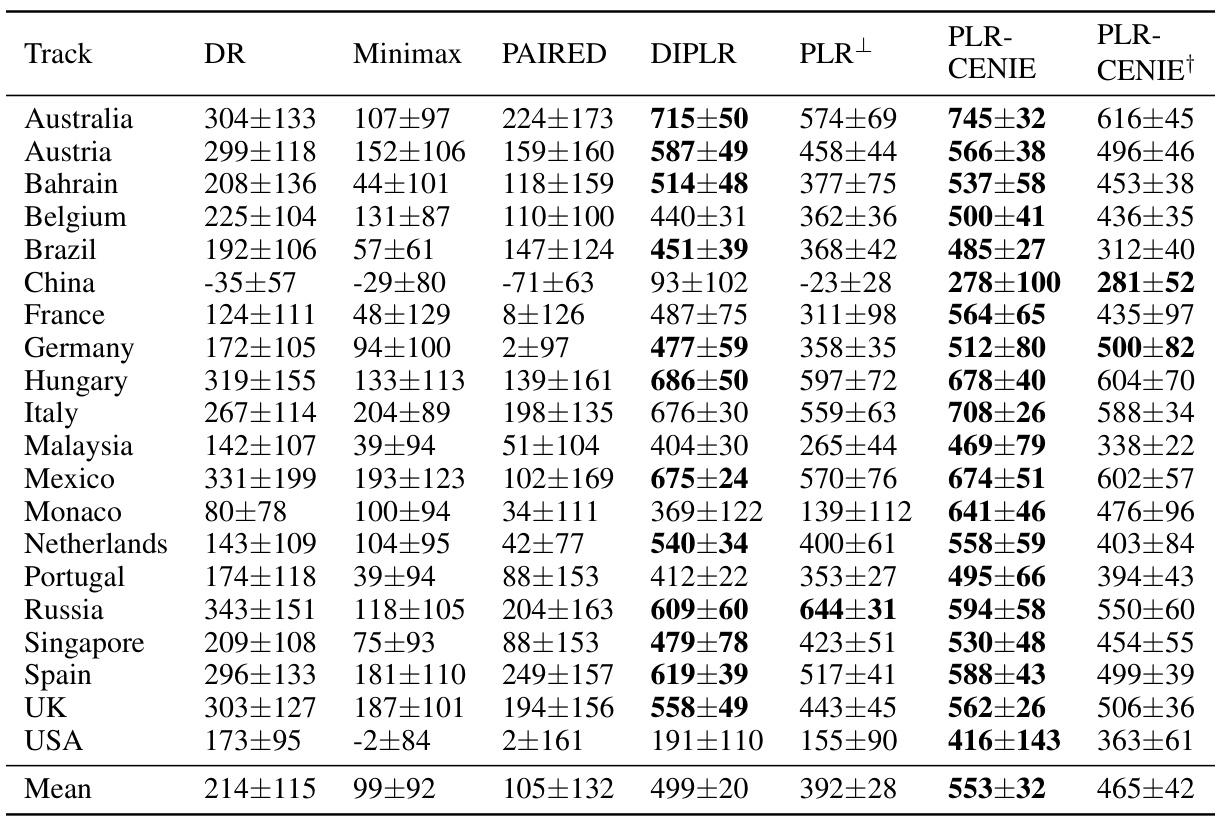

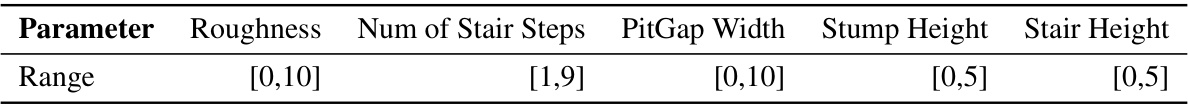

This table shows the thresholds for each of the eight environment parameters used in the BipedalWalker domain. A level is classified into different difficulty levels (Easy, Moderate, Challenging, etc.) based on how many of these thresholds are met. This is crucial for understanding the difficulty composition analysis in the paper.

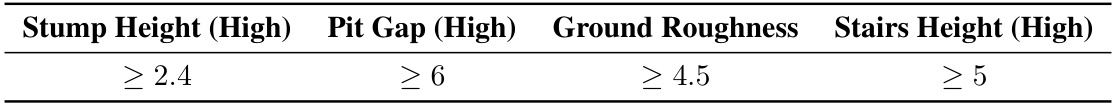

This table presents the zero-shot transfer performance of different algorithms on 20 human-designed F1 racing tracks. The results are the mean reward ± standard error, averaged over 5 independent runs with 50 trials per track. It shows PLR-CENIE’s consistent superior performance compared to other methods, demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to generalize to unseen environments. PLR-CENIE† represents a version of the algorithm using only novelty for prioritization.

This table presents the thresholds used for defining the environment parameters in the 8D BipedalWalker environment. These thresholds determine whether a given environment is classified as easy, moderate, challenging, very challenging, or extremely challenging. Specifically, it lists the minimum values for each parameter that must be exceeded to move to the next difficulty level. These parameters influence the complexity of the environment and are used in the paper’s analysis of level difficulty.

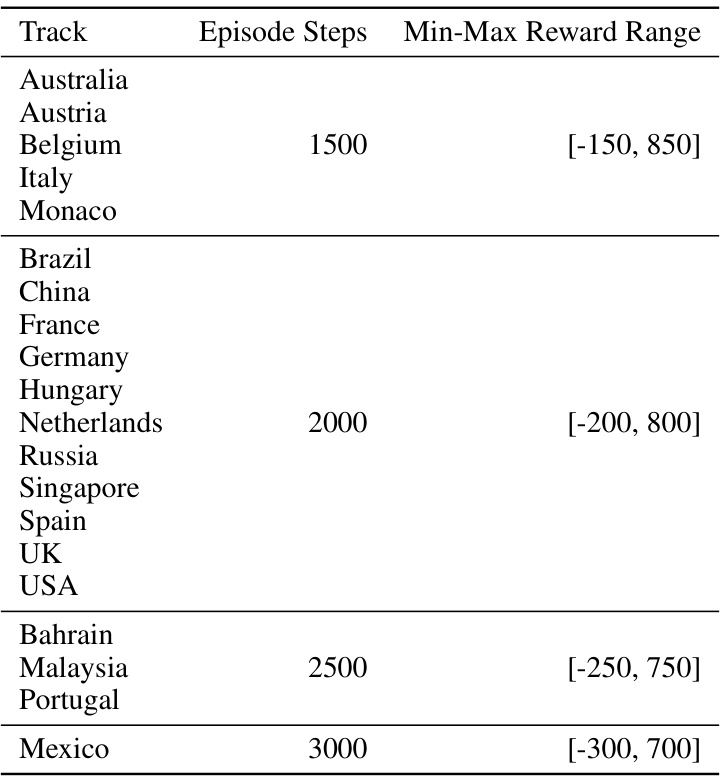

This table shows the minimum and maximum reward ranges for each of the 20 Formula 1 racing tracks used in the CarRacing experiments. These ranges are used to normalize the reward values before calculating the interquartile mean (IQM) and optimality gap, which are used to evaluate the performance of different algorithms. The episode step also varies for different track.

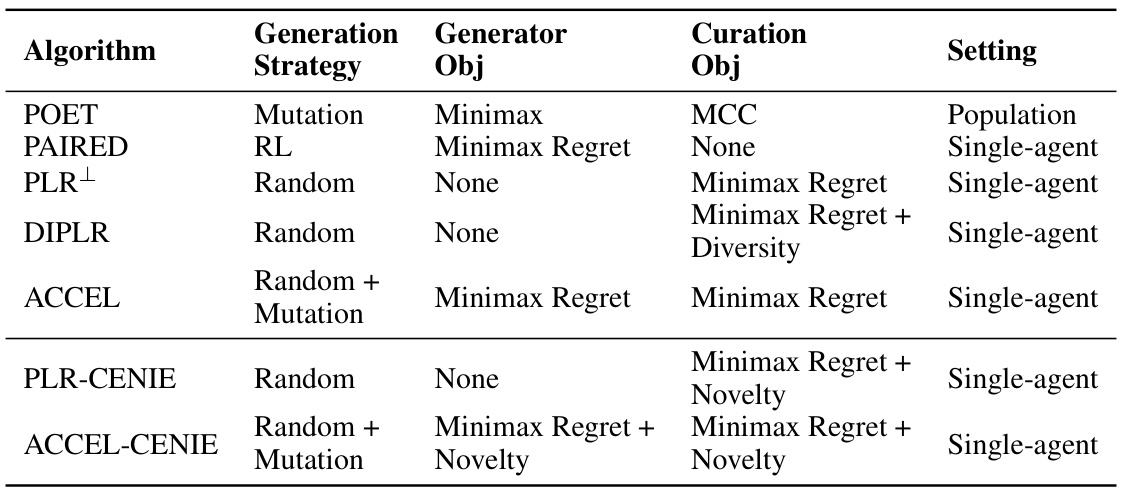

This table summarizes the key characteristics of several Unsupervised Environment Design (UED) algorithms, including both fundamental methods and those enhanced with the proposed CENIE framework. It compares algorithms across generation strategies (how new levels are created), generator objectives (the goal of the level generation process), curation objectives (how levels are selected for training), and the overall setting (whether a single agent or a population of agents is used). The table highlights the differences in the approaches to level generation and selection and the overall impact on the training process.

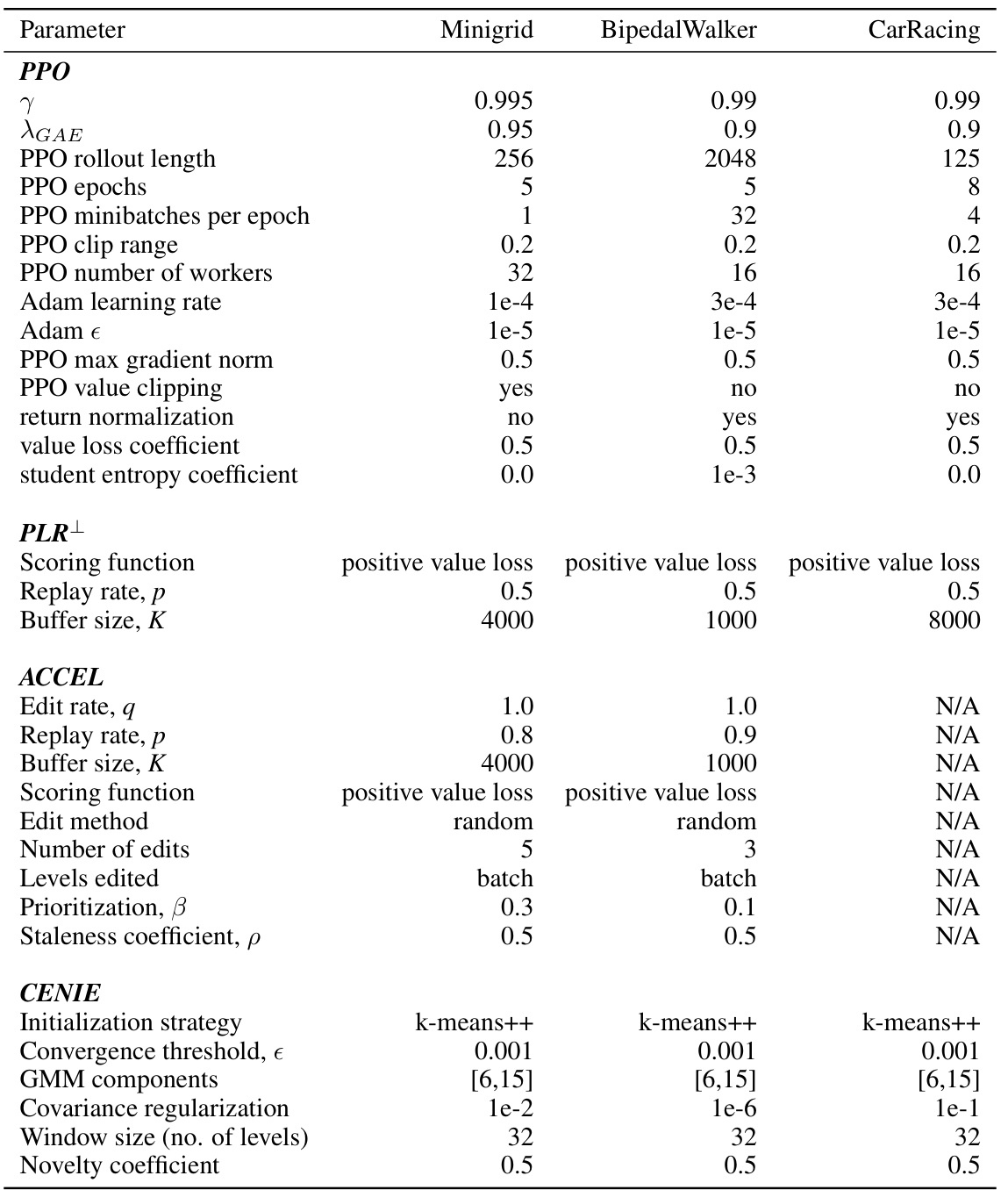

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the proposed algorithms, PLR-CENIE and ACCEL-CENIE. It shows the settings for the PPO algorithm, including rollout length, epochs, minibatches per epoch, clip range, number of workers, Adam learning rate, epsilon, max gradient norm, value clipping, return normalization, value loss coefficient, and student entropy coefficient. Additionally, it details the hyperparameters for PLR+, including the scoring function, replay rate, and buffer size, and ACCEL, including edit rate, replay rate, buffer size, scoring function, edit method, number of edits, levels edited, and prioritization coefficient. Finally, it provides the hyperparameters for CENIE, which include initialization strategy, convergence threshold, GMM components, covariance regularization, window size (number of levels), and novelty coefficient. The hyperparameters are specified for three different environments: Minigrid, BipedalWalker, and CarRacing.

Full paper#