↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current AI struggles with general mathematical reasoning, lacking the ability to generate interesting and challenging problems and solve them independently. Existing methods either rely on large pre-trained datasets of human-generated problems, leading to limitations in generalization and exploration, or focus on solving extrinsically defined problems, hindering the capacity for discovery. This paper introduces MINIMO, an intrinsically motivated agent for formal mathematical reasoning.

MINIMO uses a novel combination of constrained decoding and type-directed synthesis for conjecture generation, ensuring well-formed conjectures, even when starting from a randomly initialized model. The same model is used for both conjecture generation and proof search. A self-improvement loop allows the agent to continuously generate harder conjectures and to improve its theorem-proving abilities. Hindsight relabeling is used to improve data efficiency by re-interpreting failed proof attempts as successful ones for alternative, newly generated goals. Experiments on propositional logic, arithmetic, and group theory demonstrate MINIMO’s ability to bootstrap from axioms alone, self-improving significantly in both generating true, challenging conjectures and proving them.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers working on mathematical reasoning. It introduces a novel approach to training intrinsically motivated agents that learn to generate challenging mathematical conjectures and prove them, opening new avenues for research in automated theorem proving and AI-driven mathematical discovery. The self-improvement loop used to train the model addresses long-standing limitations in formal mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The findings are broadly applicable to other fields where generating and solving challenging problems is key.

Visual Insights#

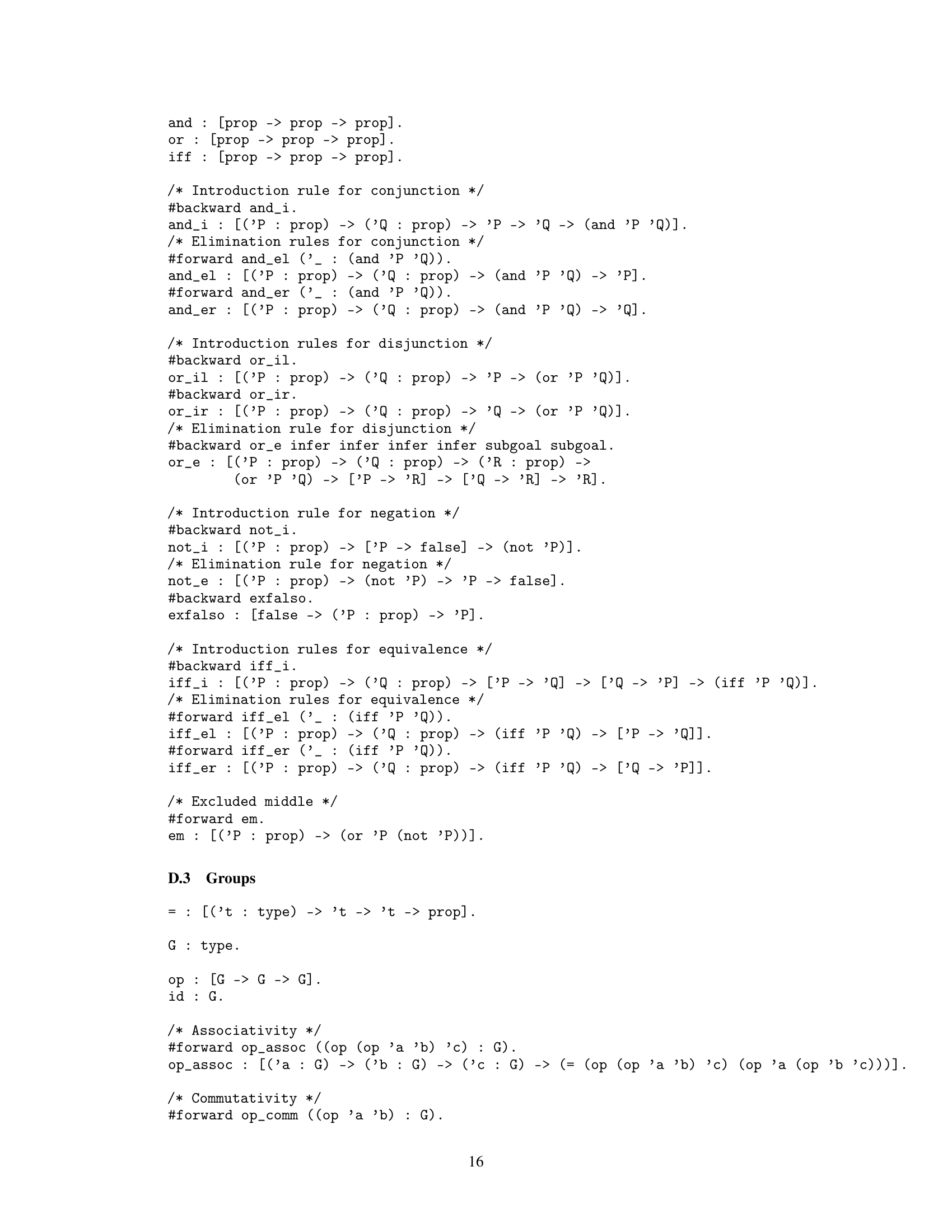

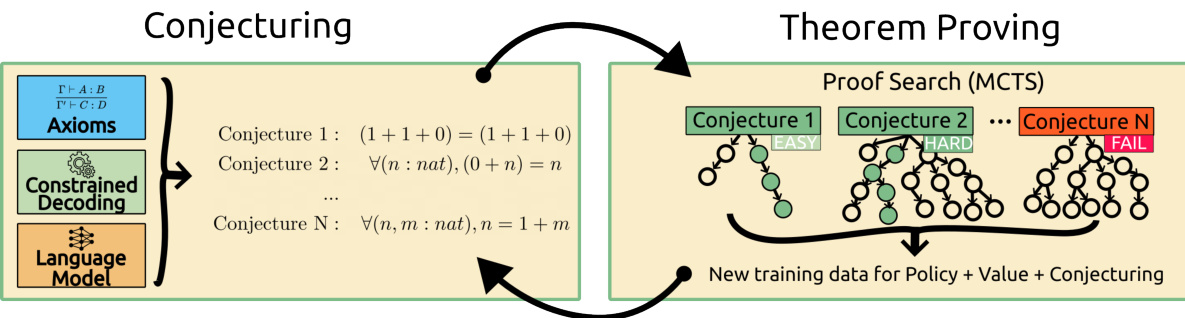

The figure illustrates the MINIMO framework. It shows a two-part process: Conjecturing and Theorem Proving. In the Conjecturing phase, a language model, informed by axioms and using constrained decoding, generates novel mathematical conjectures. These conjectures are then fed into the Theorem Proving phase, where a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm, guided by a policy and value function (also learned from the language model), attempts to find proofs for the conjectures. The success or failure of proof attempts, along with the difficulty of the proofs, generates new training data, which is then used to improve both the conjecturing and theorem proving components of the model in an iterative self-improvement loop.

In-depth insights#

Intrinsic Math AI#

The concept of “Intrinsic Math AI” evokes an AI system that discovers and develops mathematical knowledge without explicit human guidance or pre-programmed datasets. This contrasts with extrinsic approaches that train AI on existing mathematical data. An intrinsic Math AI would likely learn by interacting with a formal system (e.g., axiomatic system), formulating its own conjectures, and developing methods to prove or disprove them. This process mirrors how humans discover mathematics, driven by curiosity and a desire to solve challenging problems. The key challenge lies in designing reward functions and mechanisms that incentivize the AI to explore challenging yet solvable problems. A successful Intrinsic Math AI would not just solve pre-defined problems but actively generate new mathematical knowledge, potentially advancing the field in unexpected ways. This requires sophisticated techniques from reinforcement learning, program synthesis, and theorem proving, integrated in a novel manner. The system would need to balance exploration (generating new conjectures) and exploitation (proving existing ones), avoiding getting stuck in easy or impossible problems. Such an AI, if realized, could represent a significant paradigm shift in AI and mathematics, leading to both theoretical breakthroughs and practical applications.

Conjecture Learning#

Conjecture learning lies at the heart of mathematical discovery, representing the process of formulating new hypotheses or propositions. It’s a creative process, often driven by intuition and pattern recognition, but also grounded in existing mathematical knowledge. Effective conjecture learning requires a balance between creativity and rigor. The ability to generate plausible and potentially provable conjectures is a crucial skill for mathematicians. Methods for automated conjecture generation often involve sampling from a space of possible conjectures, guided by a model trained on mathematical data or a language model trained on mathematical text. This requires careful consideration of the search space and techniques to filter or rank conjectures based on their plausibility. Furthermore, evaluating the quality of conjectures is a key challenge; simple metrics like syntactic validity are insufficient; sophisticated techniques are needed to evaluate potential mathematical significance and difficulty. A successful approach to conjecture learning would need to incorporate elements of both search and verification, ideally in a self-improving loop, where attempts to prove or disprove conjectures inform the generation of future ones. This self-improvement could lead to both faster progress in solving existing problems and also the discovery of novel mathematical results.

Hindsight Relabeling#

The concept of “Hindsight Relabeling” offers a powerful technique to enhance the efficiency of reinforcement learning, particularly in scenarios with sparse rewards, such as theorem proving. By reinterpreting failed proof search trajectories as successful ones, the method cleverly generates additional training data. This is achieved by re-labeling failed attempts with alternative, achievable goals extracted from the partially completed proofs. This approach significantly increases the volume of training data, especially in the initial stages where successes are scarce. The ability to leverage both successful and unsuccessful attempts makes this technique far more sample-efficient than conventional methods. A crucial aspect is the intelligent selection of these alternative goals, ensuring that they are novel, relevant, and of a reasonable difficulty. By continuously enriching the training dataset with a blend of successes and strategically re-labeled failures, the Hindsight Relabeling method promotes a more robust and accelerated learning process for the mathematical reasoning agent. This approach ultimately helps the agent to self-improve its capabilities in generating increasingly challenging yet provable conjectures.

Self-Improvement Loop#

The concept of a self-improvement loop in the context of AI agents tackling formal mathematics is a powerful idea. The core principle revolves around the agent’s ability to iteratively improve its capabilities in two key areas: conjecturing (generating new mathematical statements) and theorem proving (finding formal proofs). The agent starts with a basic understanding of the mathematical domain, typically axiomatic systems. The loop functions by first generating conjectures based on its current abilities. The success or failure in proving these conjectures provides valuable feedback, allowing the agent to refine its capabilities. Successful proofs generate training data to strengthen both conjecture generation and theorem-proving abilities. Failures also prove helpful: through hindsight relabeling, even unsuccessful attempts can inform the agent, adding new valuable datapoints. This dynamic interaction allows the agent to not only solve problems but also to continuously redefine the challenge space. The difficulty of the generated conjectures dynamically adjusts to the agent’s skill level, ensuring consistent progress. The self-improvement loop is a powerful mechanism for creating an agent capable of autonomous mathematical discovery, moving beyond solving pre-defined problems towards genuinely original mathematical exploration.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending MINIMO to handle more complex mathematical domains like topology or analysis is crucial. This would necessitate developing more sophisticated methods for conjecture generation and proof search that can manage the increased complexity and potentially infinite search spaces. Improving the efficiency and scalability of MINIMO is another key focus area. The current approach relies on a Transformer model, and computational constraints may limit its ability to tackle more substantial problems. Exploring more efficient architectures and training methods, perhaps involving techniques like curriculum learning, could significantly improve performance. Developing more advanced techniques for conjecture generation and proof search could enhance MINIMO’s ability to discover novel and interesting results. This could include integrating advanced search algorithms, such as those informed by symbolic computation, and incorporating techniques for prioritizing conjectures based on their potential significance. Finally, further research is needed to fully understand and address the limitations of intrinsic motivation in mathematical reasoning. While MINIMO demonstrates the potential of this approach, a deeper understanding of its strengths and weaknesses is essential for guiding future development and maximizing its impact on automated mathematical discovery.

More visual insights#

More on figures

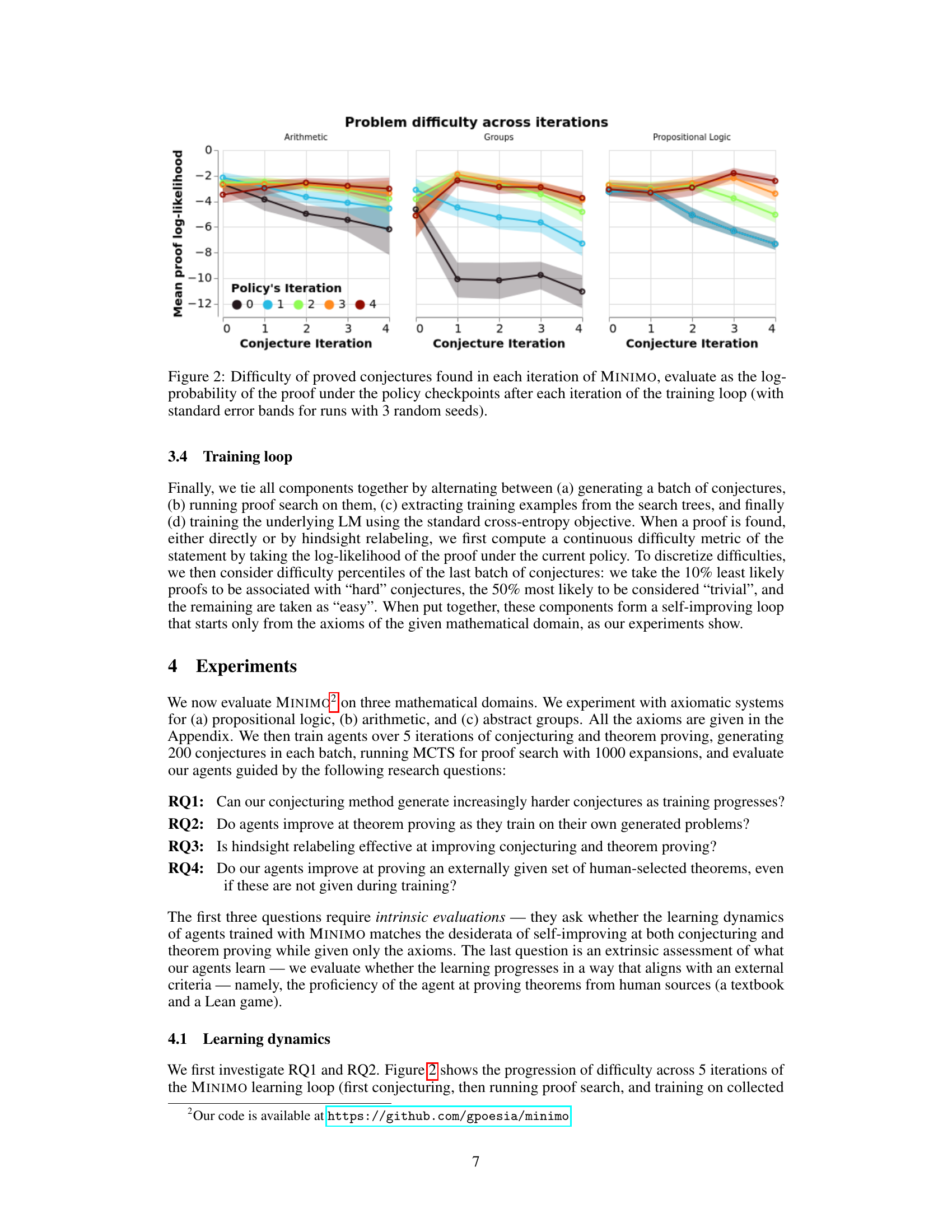

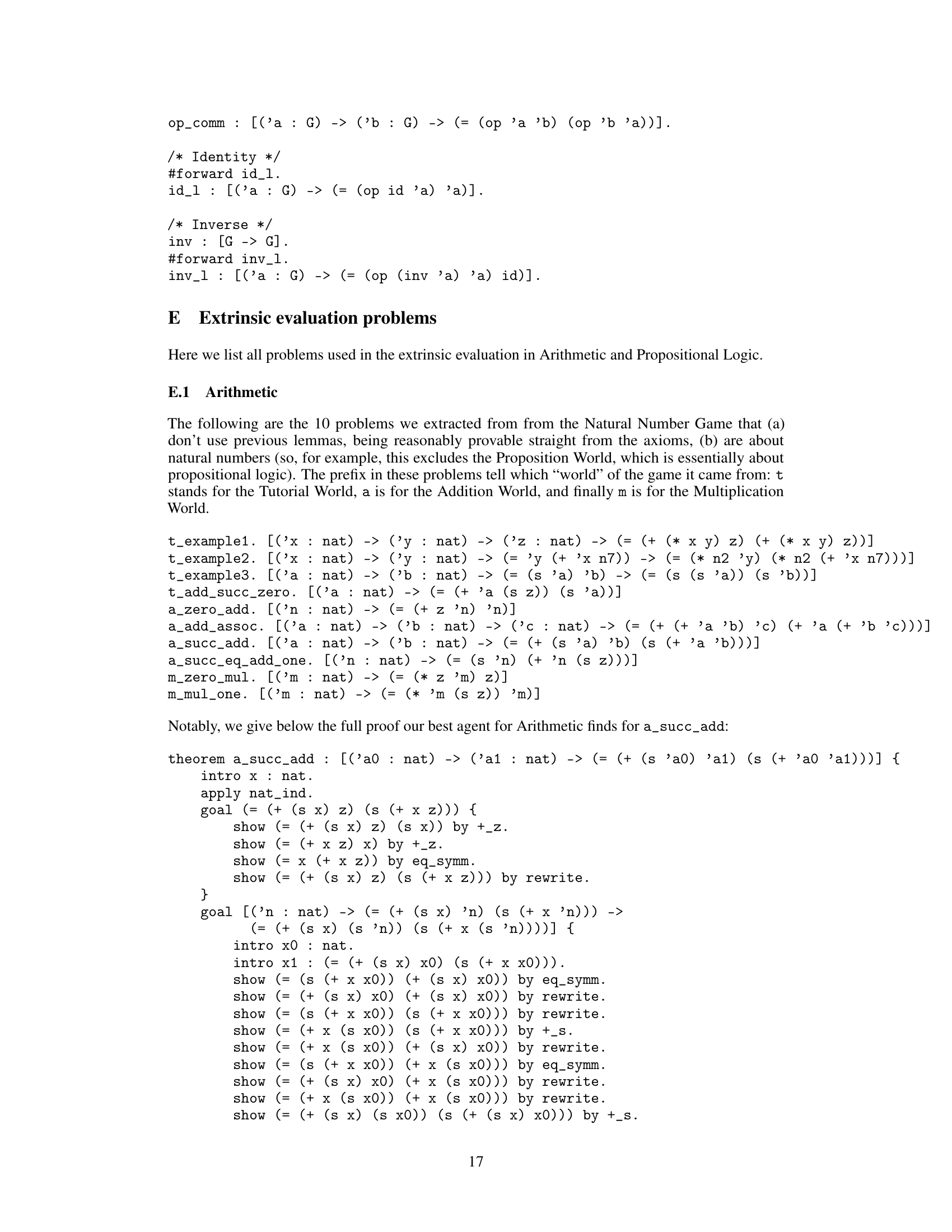

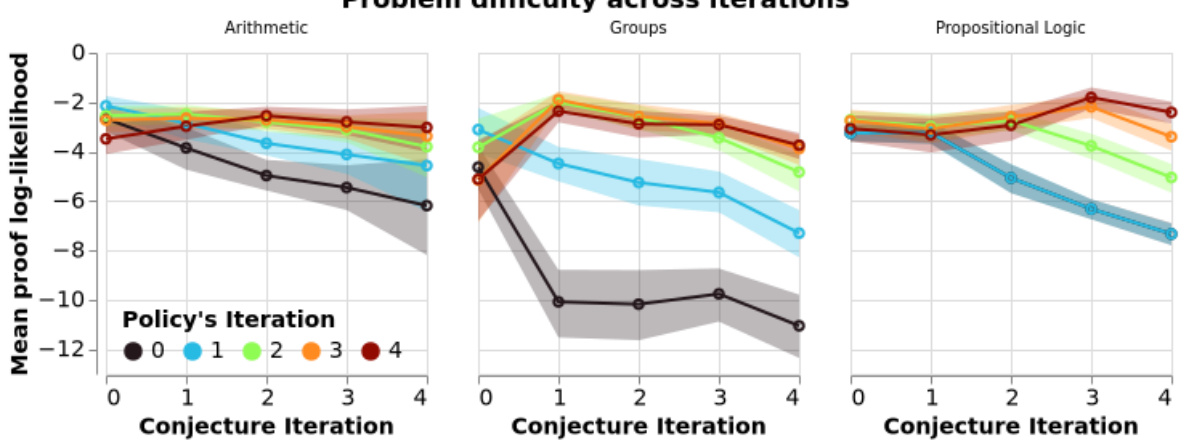

This figure shows how the difficulty of proven conjectures changes over training iterations of the MINIMO model. Difficulty is measured by the negative log-probability of the proof under the policy network at each iteration. The plot shows that as the model trains, it generates progressively harder (lower log-probability) conjectures that are still provable. The lines represent the difficulty of conjectures across the different training iterations and the shaded regions represent the standard error for three random seeds.

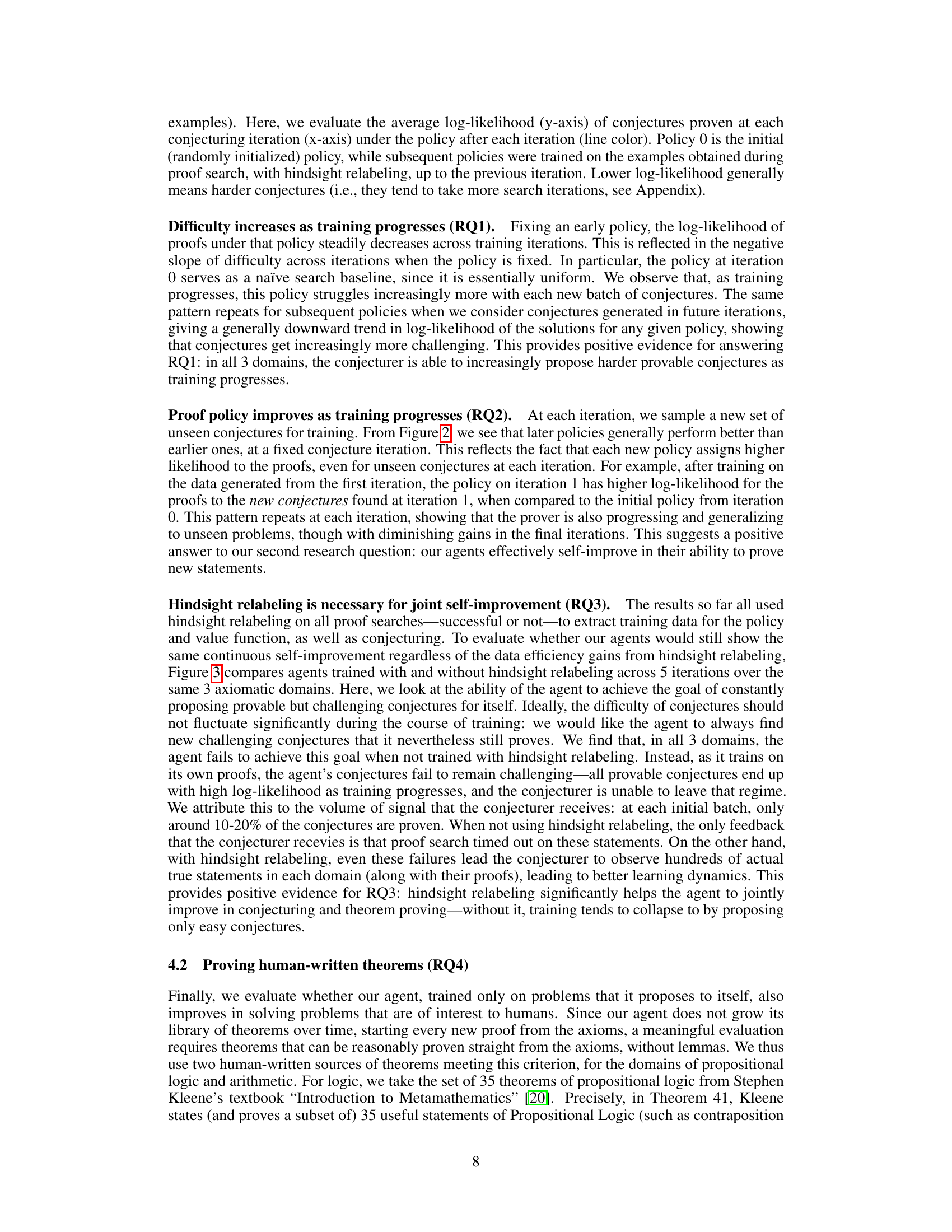

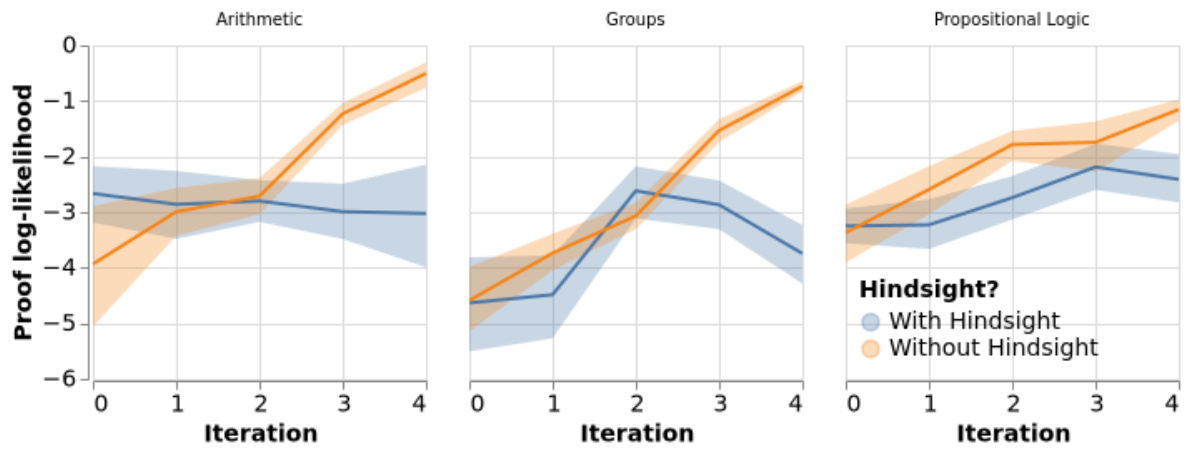

This figure shows the effect of hindsight relabeling on the difficulty of conjectures generated by the MINIMO agent across 5 training iterations. The y-axis represents the negative log-likelihood of the proof under the current policy (lower values mean harder problems). The x-axis shows the training iteration. Separate lines are shown for experiments with and without hindsight relabeling. The shaded area shows standard error across three runs. The results indicate that hindsight relabeling is crucial for maintaining the challenge of the generated conjectures.

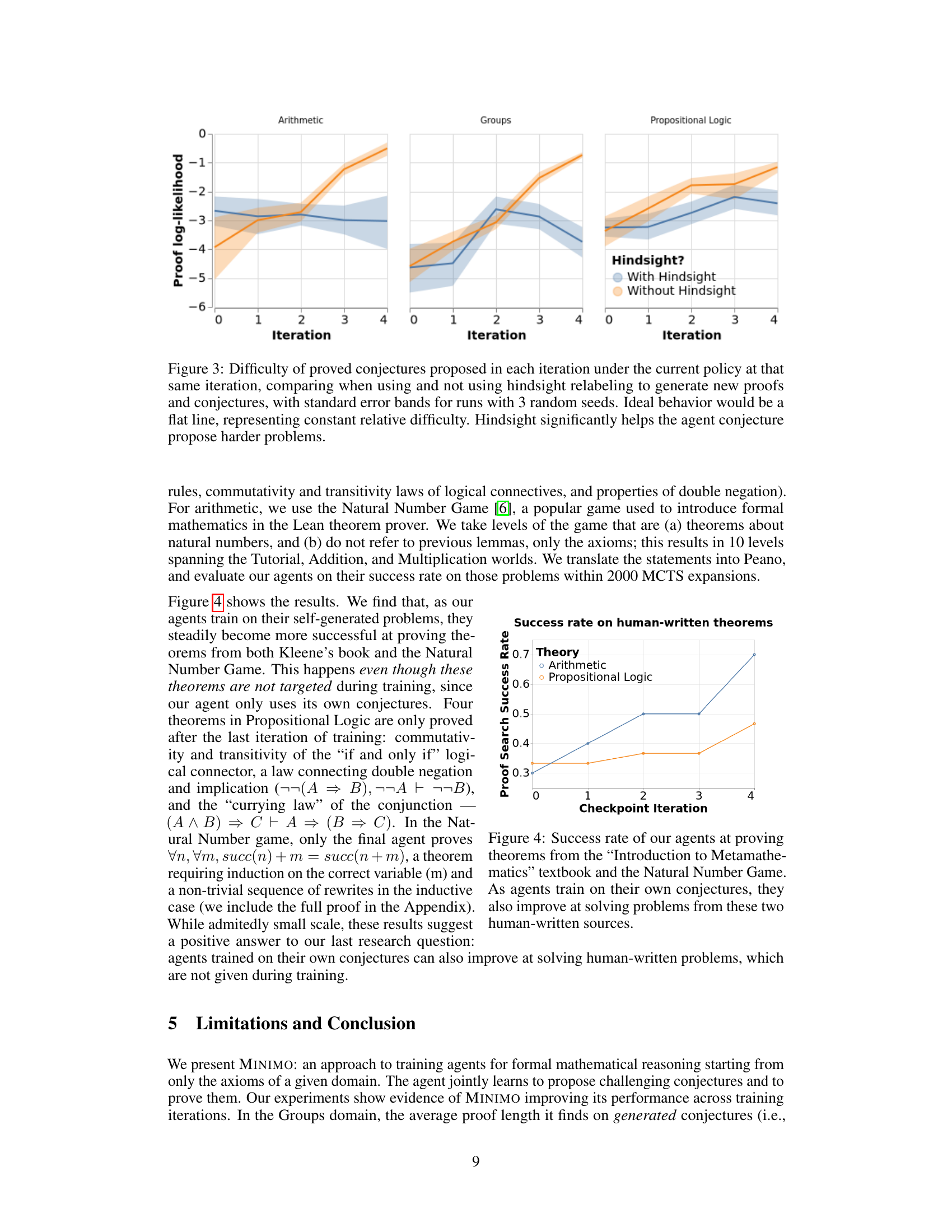

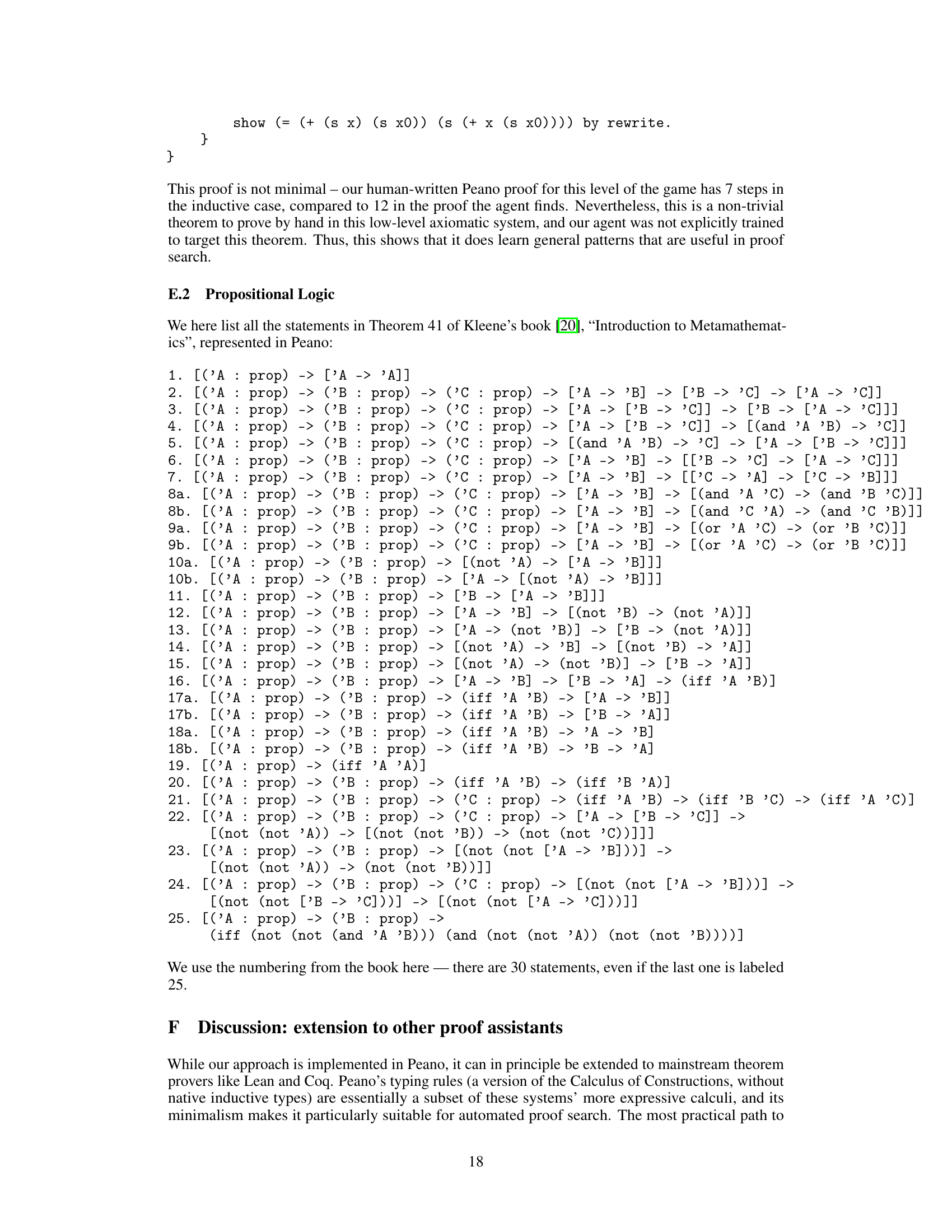

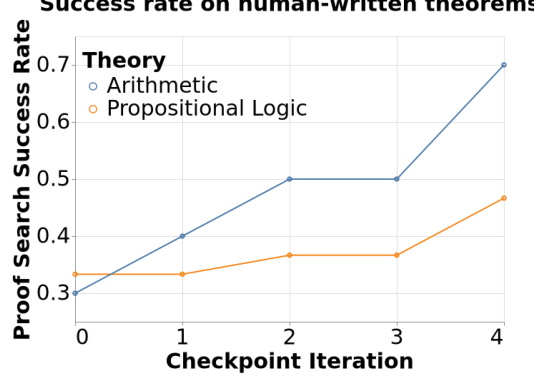

This figure shows the success rate of the trained agents in proving theorems from two external sources: Kleene’s textbook and the Natural Number Game. The x-axis represents the checkpoint iteration (training stage), and the y-axis represents the success rate (proportion of theorems proven within 2000 MCTS expansions). The plot shows separate lines for the Arithmetic and Propositional Logic domains, demonstrating the improvement in solving human-written theorems as the agents trained on self-generated problems progress through the training iterations.

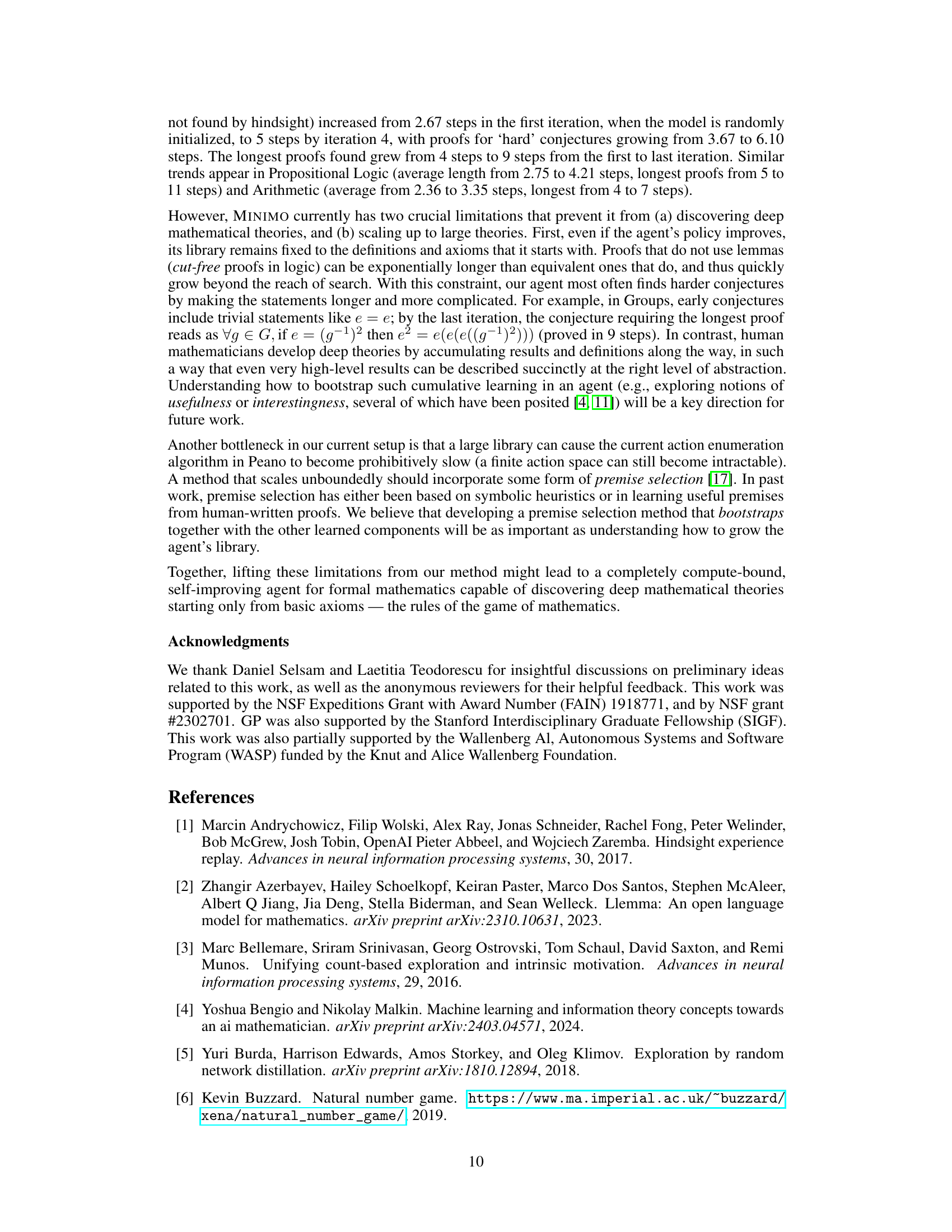

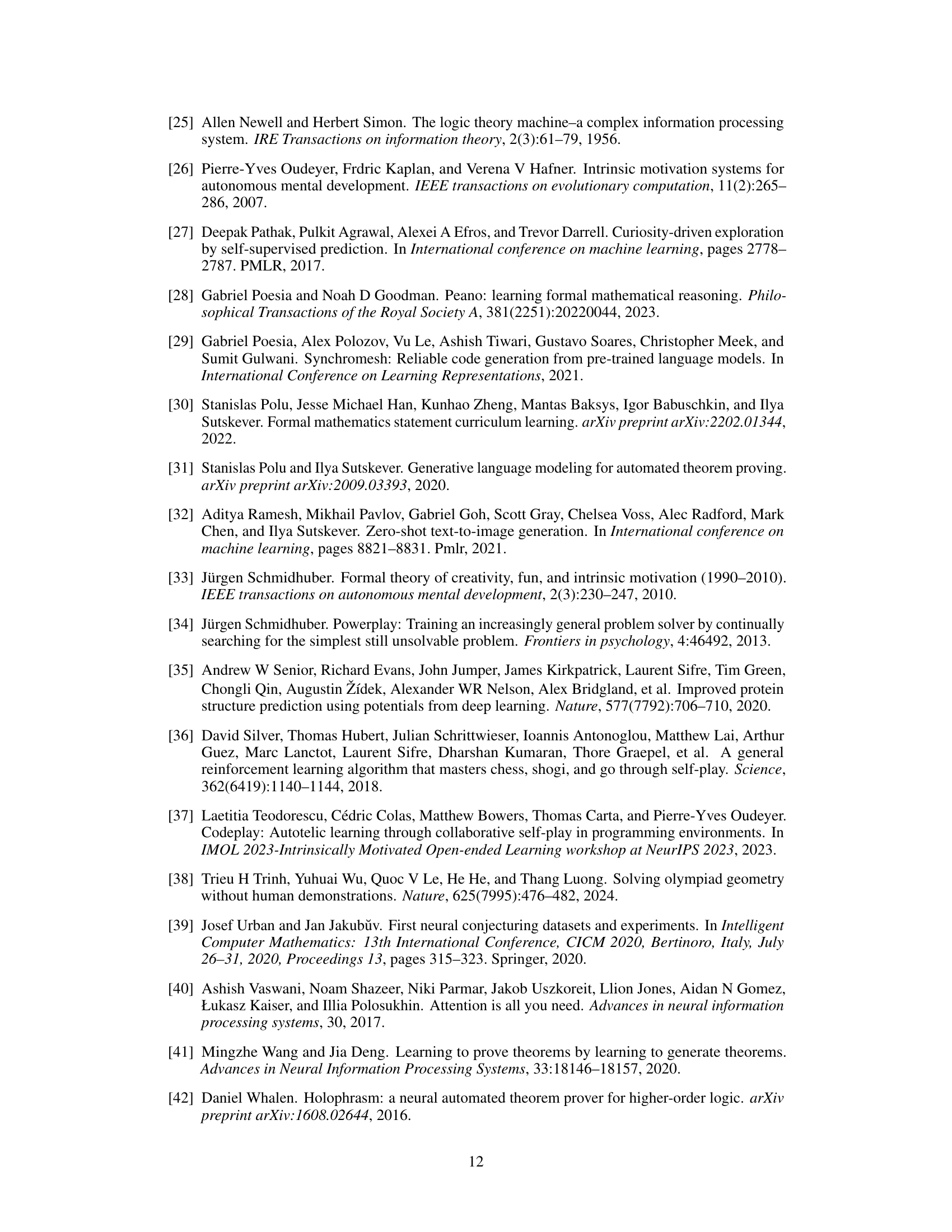

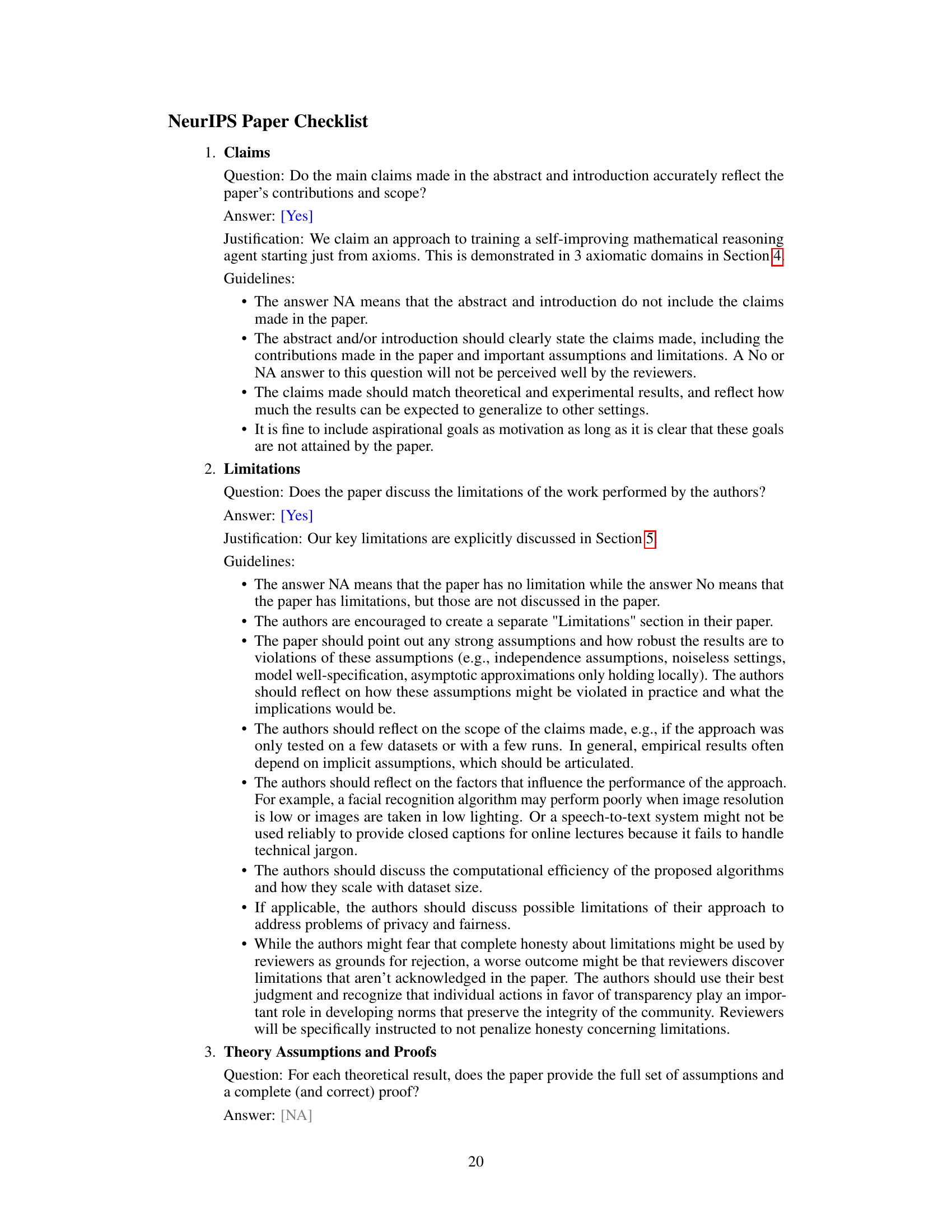

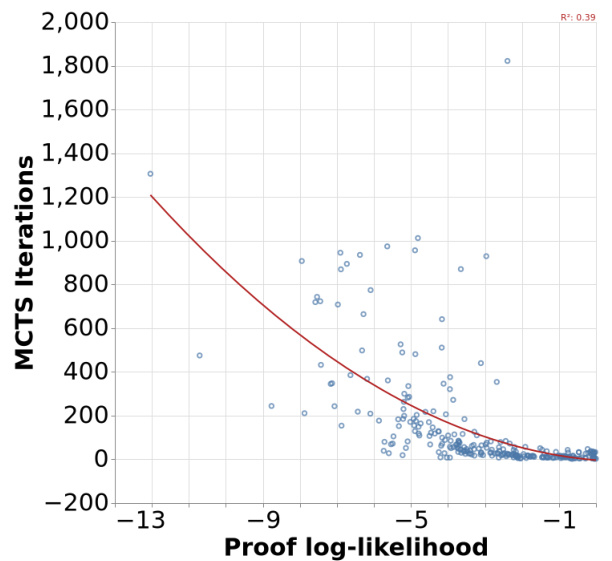

This figure shows the relationship between the number of iterations required by Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to find a proof and the log-likelihood of that proof under the learned policy. The log-likelihood serves as a measure of difficulty; higher log-likelihood indicates an easier proof to find, hence fewer MCTS iterations are required. The data points represent individual proofs found by MCTS, showing a clear trend where higher likelihoods correlate with faster proof discovery. A regression line visually reinforces this negative correlation.

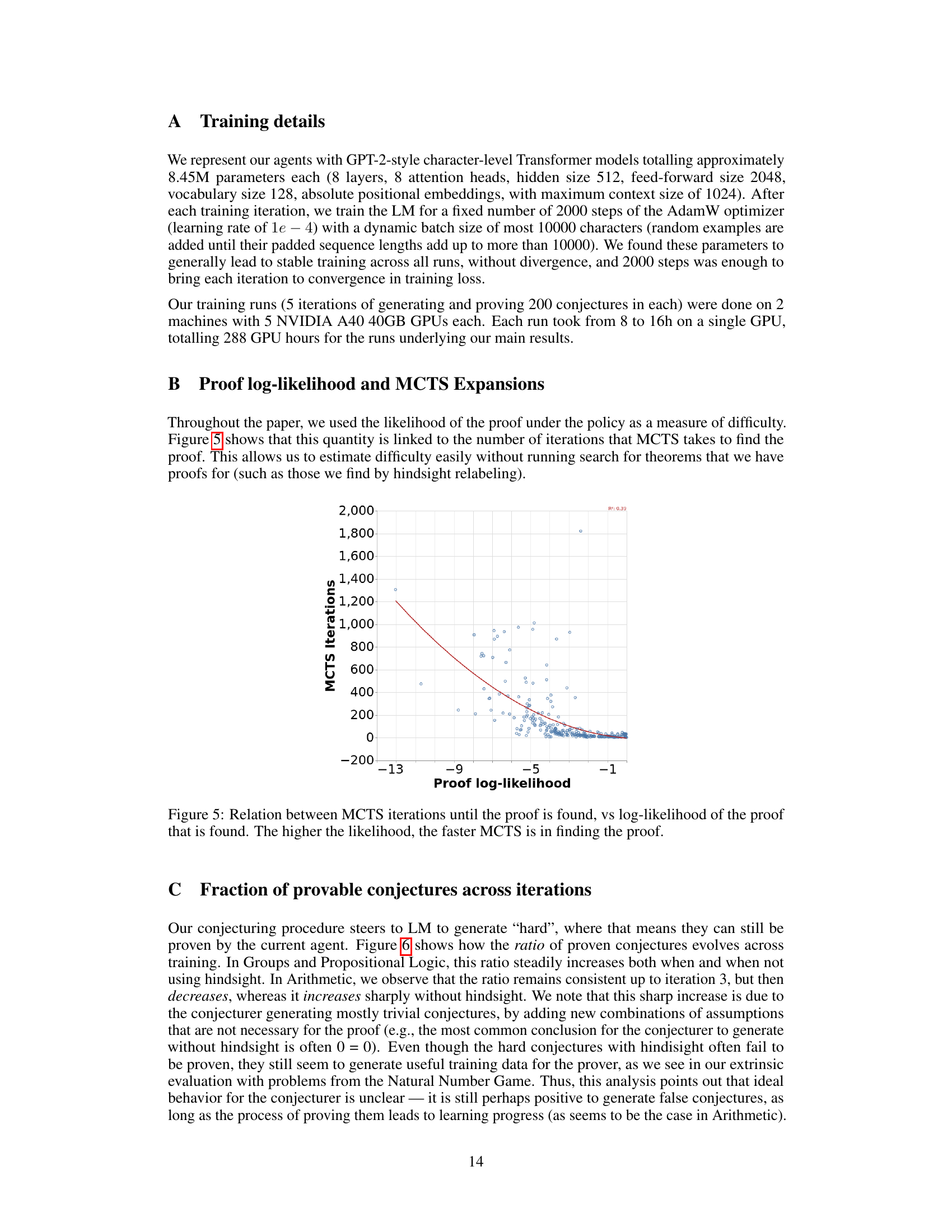

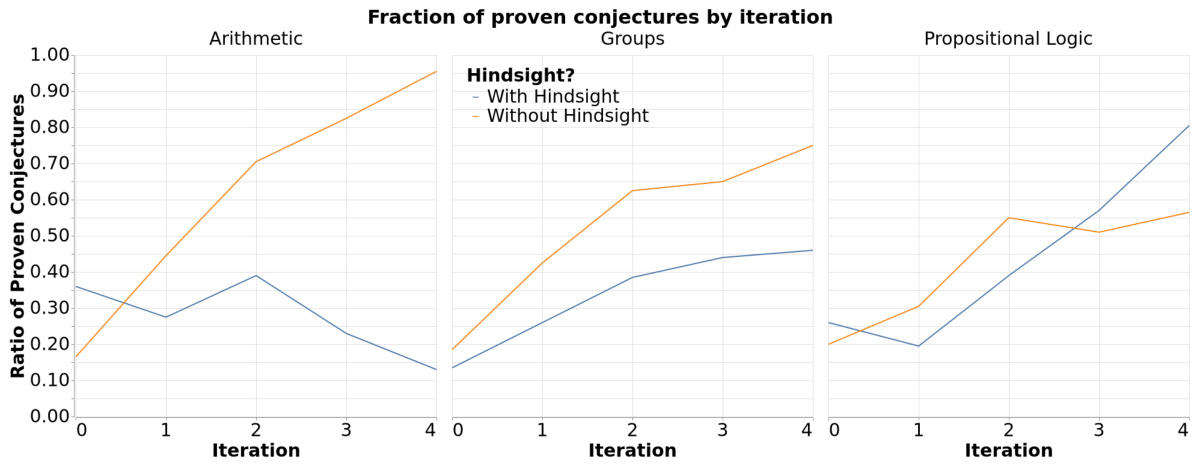

This figure shows the fraction of conjectures that were proven across different training iterations for three different axiomatic domains (Arithmetic, Groups, and Propositional Logic). The results are shown separately for experiments with and without hindsight relabeling. The graph reveals how the ratio of successfully proven conjectures changes as the model improves over multiple training iterations in each domain. This indicates whether the model is generating increasingly difficult, yet still solvable, conjectures.

Full paper#