TL;DR#

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the challenge of efficiently selecting the best vision-language model for a given task, a problem faced by many researchers. The proposed method, SWAB, offers a novel approach to this problem, enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of VLM selection. This work is particularly timely due to the explosion of available pre-trained VLMs, making effective selection increasingly important.

Visual Insights#

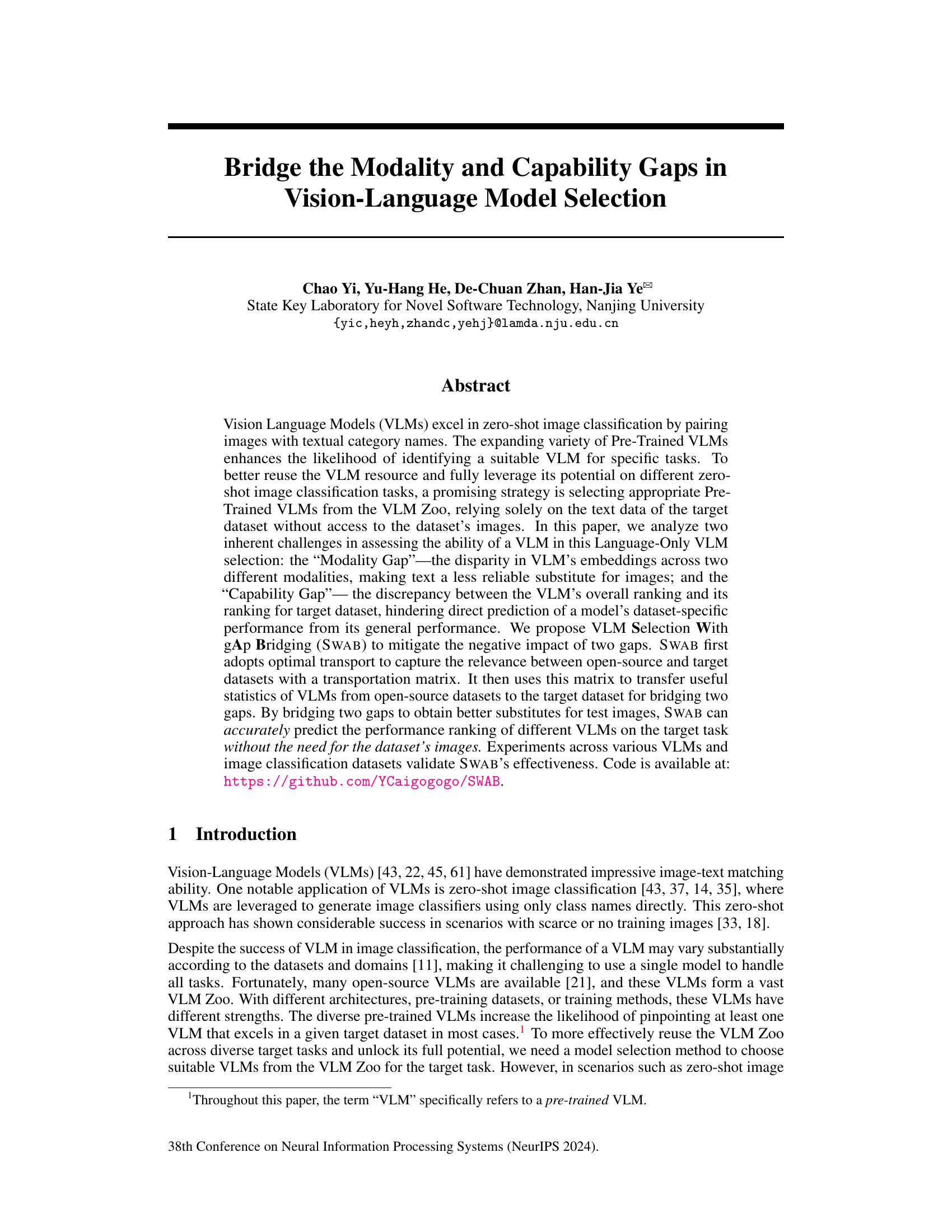

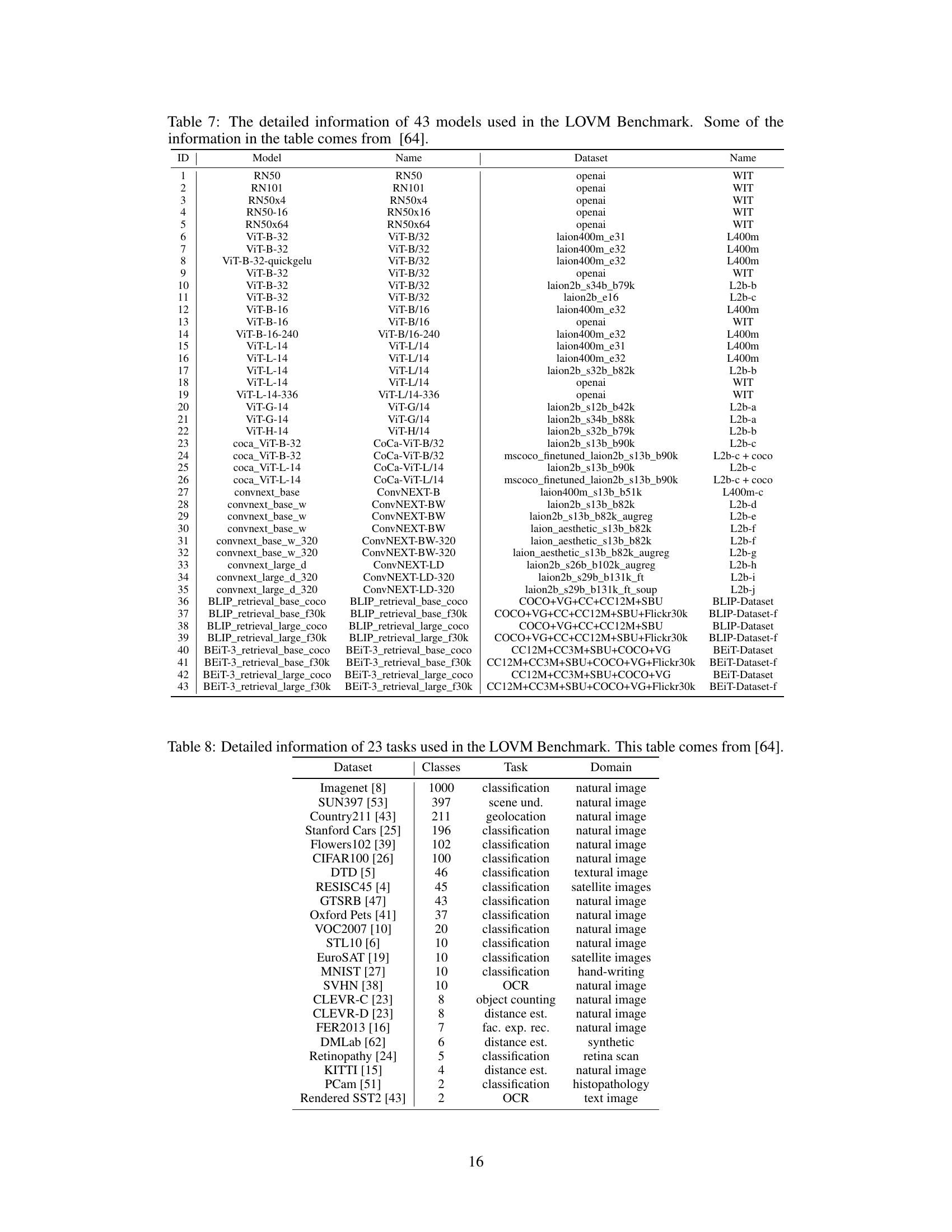

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM). A user starts by describing their task (e.g., classifying cats and dogs in natural images). A large language model (LLM) like ChatGPT then generates auxiliary text data related to the classes. This text data acts as a proxy for the actual images, which is helpful when image data isn’t available for the target dataset. A model selection algorithm then uses this text data, along with data from open-source datasets (containing both images and text), to predict how different Vision-Language Models (VLMs) will perform on the task. The best-performing VLM is finally selected.

read the caption

Figure 1: Paradigm of Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM). Users describe the details of their target tasks in text form, such as class names and image domains. Then, LOVM utilizes this information to generate class-related labeled texts through ChatGPT. These texts serve as substitutes for image samples in subsequent model selection algorithms. The model selection algorithm uses two types of data, including the open-source datasets (which have image and text data) and the text data from the target dataset, to predict the VLM's absolute or relative performance on a target dataset. It then selects the most appropriate VLM based on the predicted performance.

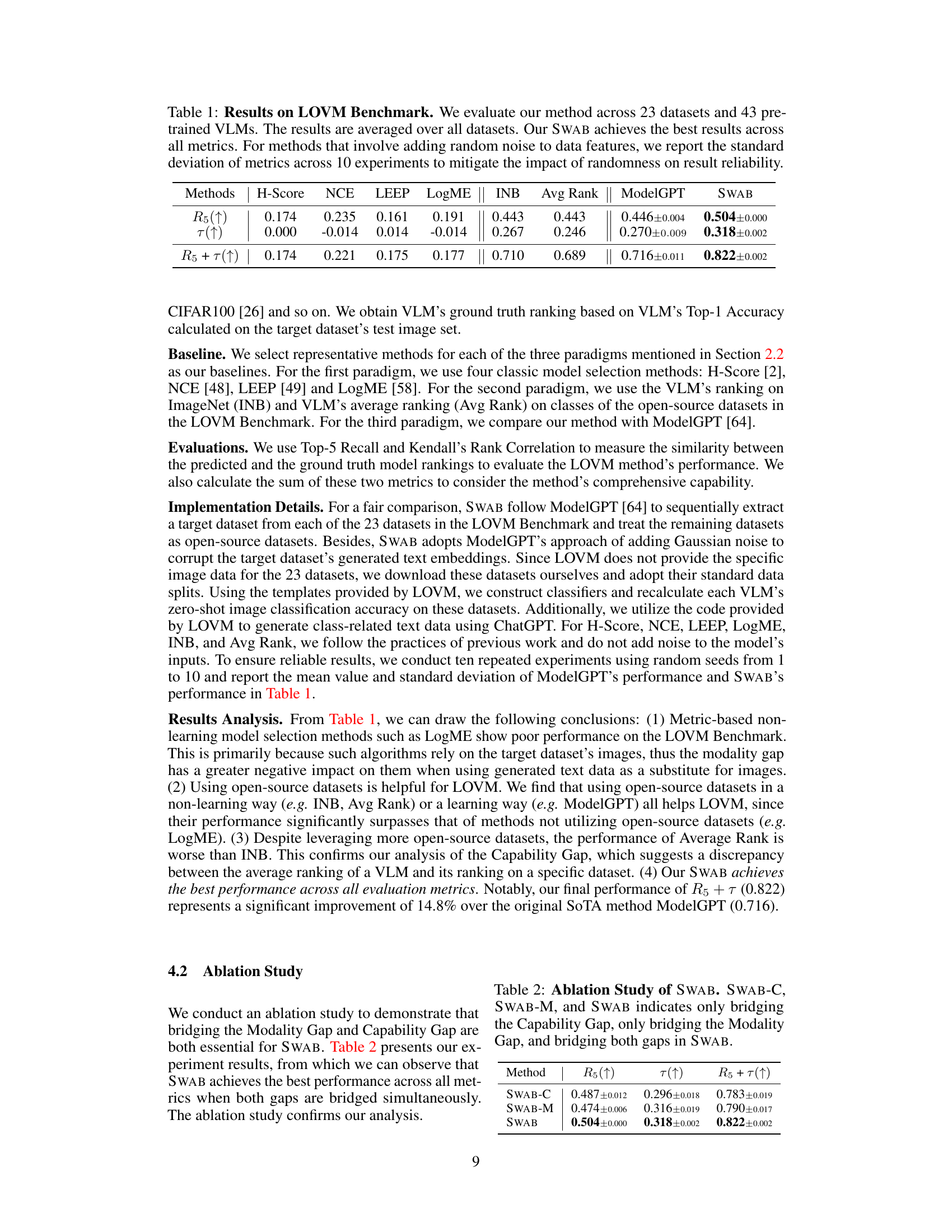

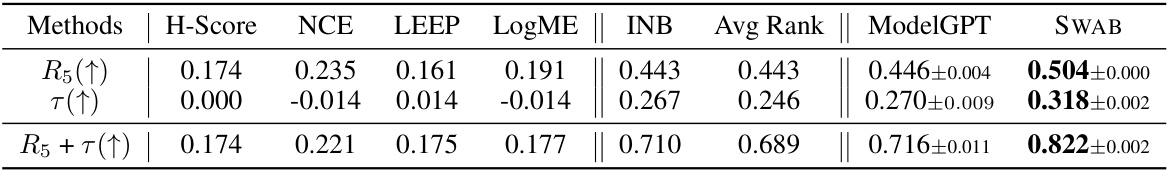

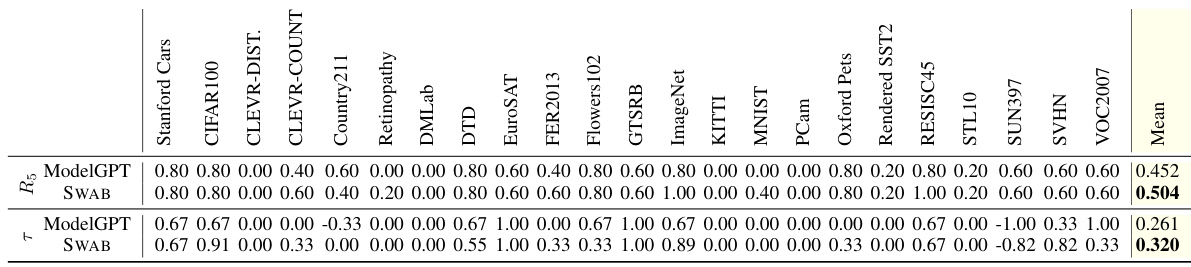

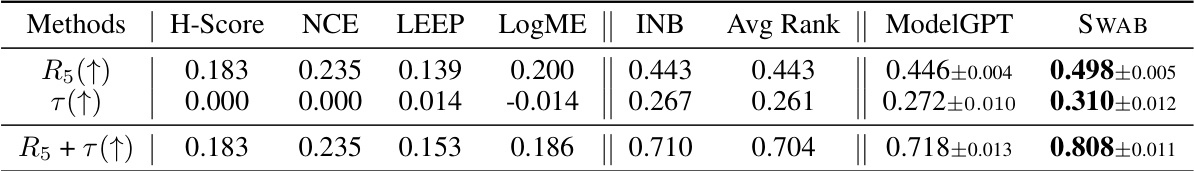

🔼 This table presents the results of the proposed SWAB method and several baseline methods on the LOVM benchmark. The benchmark consists of 23 image classification datasets and 43 vision-language models (VLMs). The table shows the average performance (across all 23 datasets) of each method, measured by four metrics: H-Score, Top-5 Recall (R5), Kendall’s Rank Correlation (τ), and the sum of R5 and τ. The standard deviations for methods using random noise are also provided to show the reliability of the results. SWAB consistently outperforms the baselines across all four metrics.

read the caption

Table 1: Results on LOVM Benchmark. We evaluate our method across 23 datasets and 43 pre-trained VLMs. The results are averaged over all datasets. Our SWAB achieves the best results across all metrics. For methods that involve adding random noise to data features, we report the standard deviation of metrics across 10 experiments to mitigate the impact of randomness on result reliability.

In-depth insights#

Modality Gap Issue#

The Modality Gap, a core challenge in Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM), arises from the inherent disparity between how Vision-Language Models (VLMs) represent visual and textual information. VLMs don’t encode these modalities in a unified, perfectly aligned space. Using text alone to proxy for images in VLM selection is problematic because textual and visual features cluster separately. This means that even semantically similar textual descriptions might not accurately capture the visual nuances a VLM relies on, leading to inaccurate performance predictions. Bridging this gap requires strategies that effectively map the textual space to the visual space the VLM utilizes, perhaps through techniques that learn a mapping between textual and visual embeddings, or methods that account for and correct the inherent differences in how VLMs process each modality. Failure to adequately address the Modality Gap compromises the reliability of any Language-Only VLM selection approach, resulting in suboptimal model choices and hindering effective VLM resource utilization.

Capability Gap Issue#

The ‘Capability Gap Issue’ highlights a critical problem in Vision-Language Model (VLM) selection: a model’s overall performance ranking may not accurately predict its performance on a specific task. A VLM might excel across many datasets but underperform on a particular target dataset, demonstrating a disconnect between general capability and task-specific effectiveness. This gap arises from the heterogeneity of datasets, with variations in domain, image style, and class distribution influencing VLM performance differently. Addressing this necessitates methods that go beyond average performance metrics. Instead, techniques are needed which estimate task-specific performance, perhaps by leveraging dataset similarity measures or transfer learning approaches. Successfully bridging this gap is crucial for effective VLM reuse, allowing researchers and practitioners to confidently select the optimal model for their specific needs, maximizing efficiency and resource utilization.

SWAB Method#

The SWAB method is presented as a novel approach to Vision-Language Model (VLM) selection, aiming to overcome the limitations of Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM). SWAB specifically tackles two key challenges inherent in LOVM: the Modality Gap and the Capability Gap. The Modality Gap refers to the discrepancy between VLM embeddings for text and images, making text a less reliable proxy for image data. The Capability Gap highlights the inconsistency between a VLM’s overall performance and its performance on a specific dataset. To address these, SWAB leverages optimal transport to create a bridge matrix that captures the relevance between open-source and target datasets’ classes. This matrix is then used to transfer useful statistics (gap vectors and performance rankings) from the open-source to the target dataset. By bridging these gaps, SWAB aims to provide more accurate estimates of VLM performance, enabling more effective model selection based solely on textual data from the target dataset. The utilization of optimal transport is crucial for its effectiveness in transferring knowledge across datasets, mitigating both the modality and capability gaps. This two-pronged approach demonstrates a significant advancement in the field of VLM selection, particularly in scenarios lacking image data for the target task.

LOVM Benchmark#

A robust LOVM benchmark is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of Language-Only VLM Selection methods. A well-designed benchmark should encompass a diverse range of pre-trained VLMs, reflecting variations in architecture, training data, and overall capabilities. The inclusion of multiple, diverse image classification datasets is also vital, ensuring that the selected VLMs are assessed across varied data distributions and visual characteristics. This ensures that the benchmark is not biased towards specific VLM architectures or dataset types. Furthermore, the evaluation metrics employed should be comprehensive, going beyond simple accuracy to include measures of ranking consistency and robustness. Transparent reporting of experimental setup and resource requirements is also essential, enabling researchers to reproduce and extend the benchmark’s findings. Finally, regular updates to the benchmark are critical to keep pace with the rapidly evolving landscape of VLMs and image datasets.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending SWAB to handle more complex scenarios, such as those involving multi-label classification or fine-grained image categorization, would significantly broaden its applicability. Furthermore, investigating alternative methods for bridging modality and capability gaps is warranted. While optimal transport proves effective, other techniques, like adversarial training or domain adaptation, might yield superior results. A crucial area for future work is developing more robust and efficient ways to estimate the transport matrix, potentially leveraging larger language models or incorporating prior knowledge about dataset relationships. Finally, a comprehensive evaluation across a wider variety of VLMs and datasets is necessary to fully assess SWAB’s generalizability and robustness, thus making it a more universally applicable tool for VLM selection.

More visual insights#

More on figures

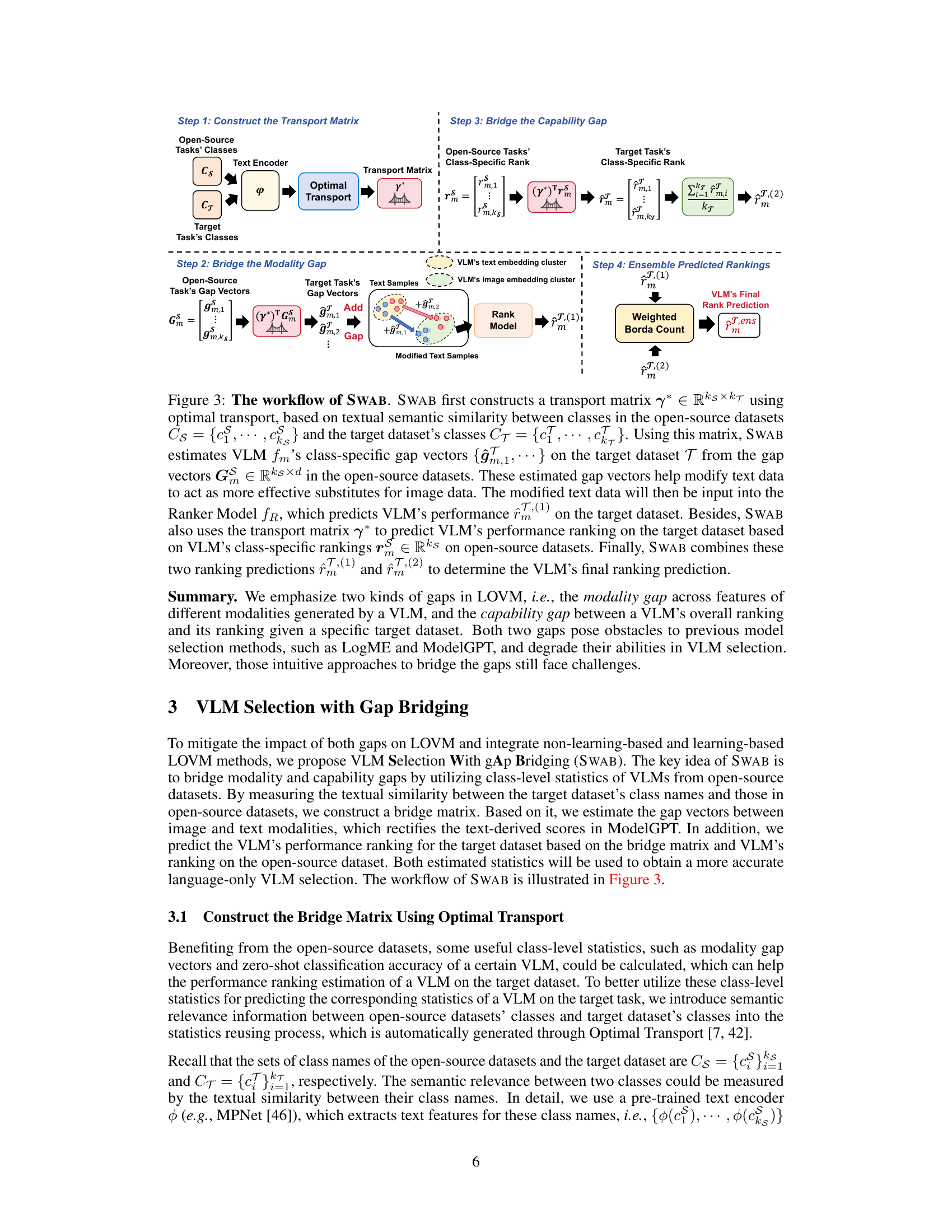

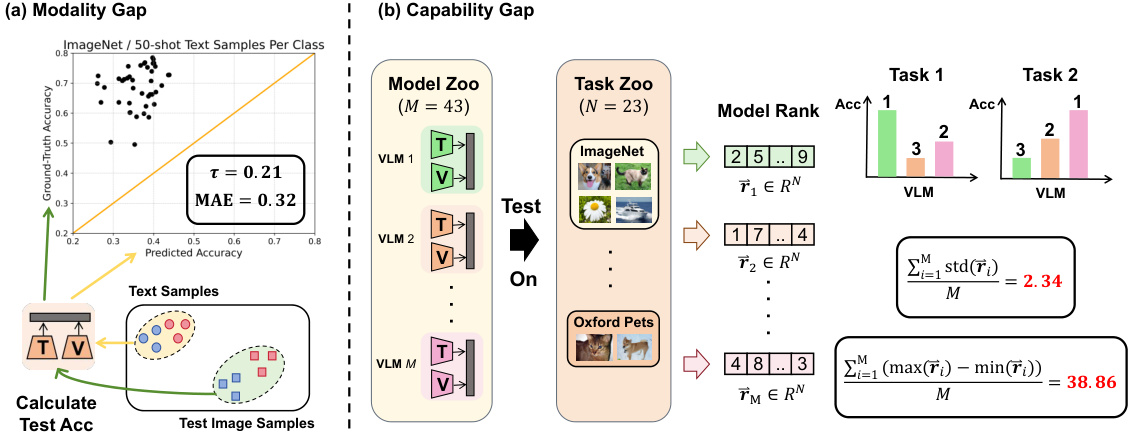

🔼 This figure presents validation experiments demonstrating the challenges of Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM). Panel (a) shows a scatter plot comparing predicted and actual zero-shot image classification accuracy using generated text as a proxy for images. The low correlation highlights the ‘‘Modality Gap’’ – text is a poor substitute for images. Panel (b) illustrates the ‘‘Capability Gap’’ by showing the variability of VLM performance across different datasets. The large standard deviation and range of performance differences emphasize that a VLM’s overall performance is not a reliable indicator of its performance on a specific dataset.

read the caption

Figure 2: Validation Experiments on the Modality Gap and Capability Gap. (a) Predicted VLMs' zero-shot image classification accuracy based on generated text data vs. VLM's true accuracy based on test images. Each point in the graph represents a model. From the result, we can find that the predicted accuracy poorly aligns with the true accuracy, indicating these text data are ineffective substitutes for image data. (b) We calculate the zero-shot image classification performance rankings of 43 VLMs across 23 datasets. We compute the average standard deviations and the mean value of differences between each VLM's maximum and minimum ranking. The result shows the performance of a VLM varies greatly across different datasets.

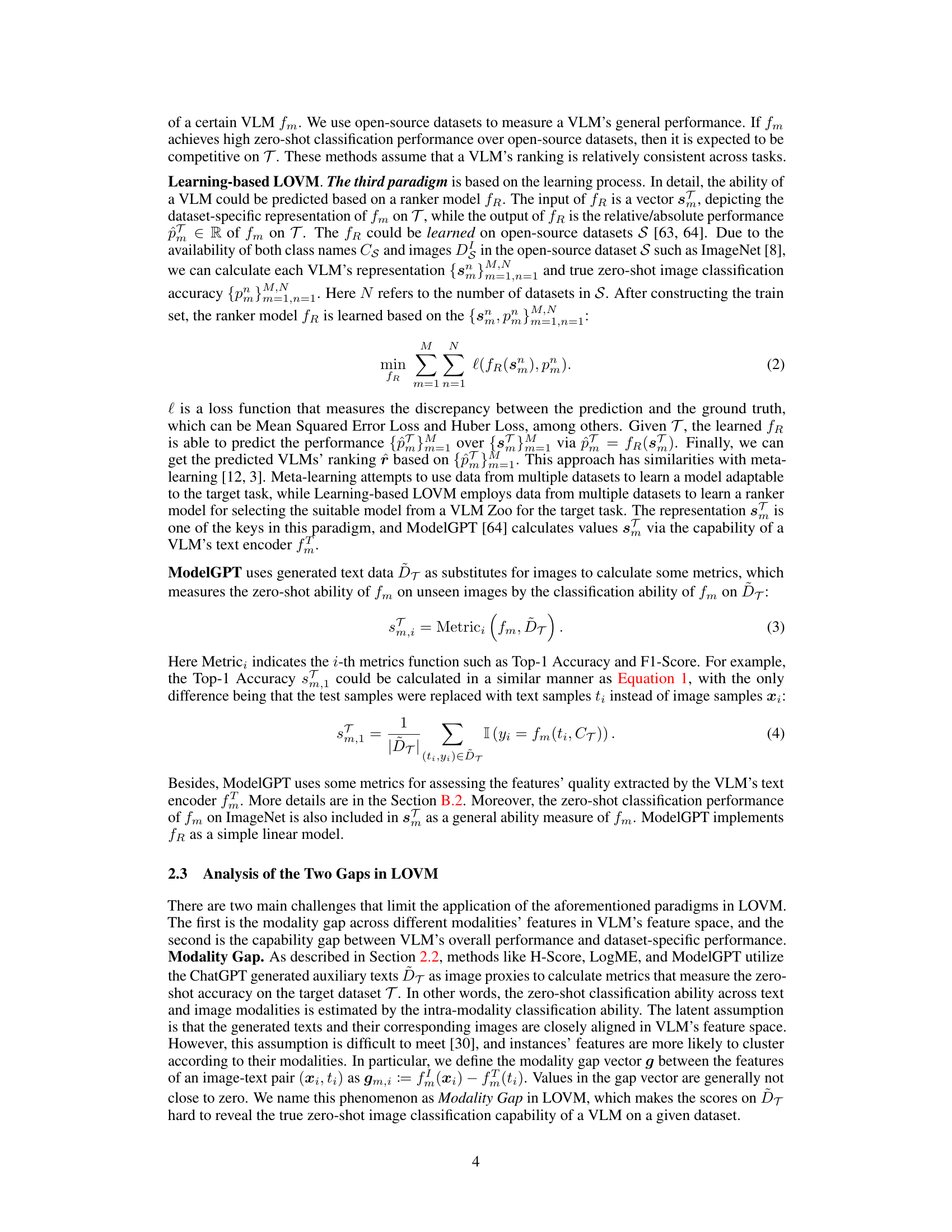

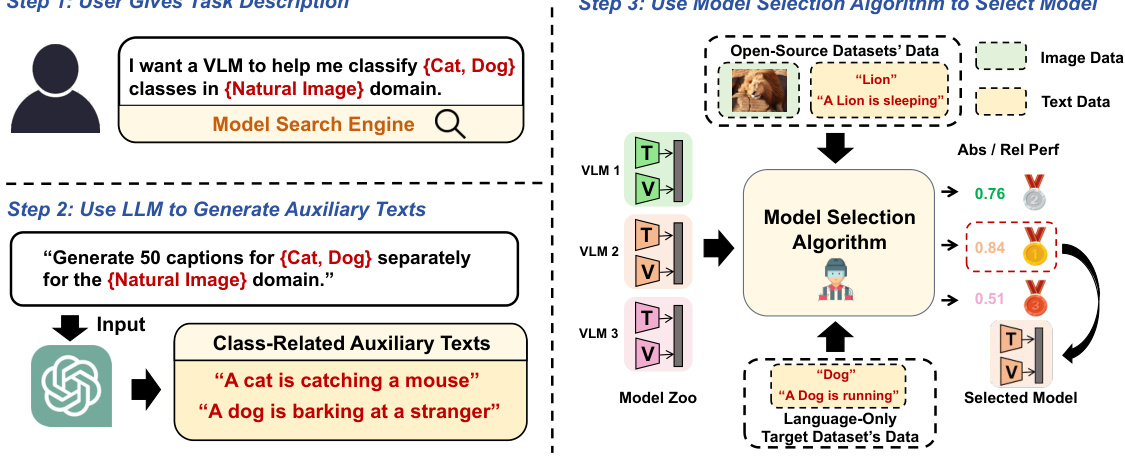

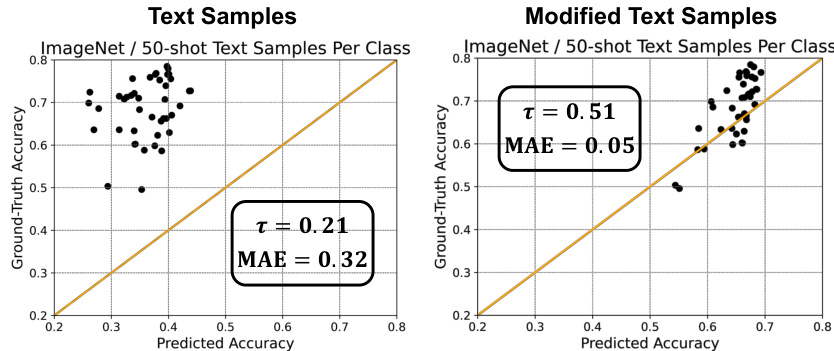

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the proposed VLM Selection With gap Bridging (SWAB) method. SWAB leverages optimal transport to create a bridge matrix based on textual similarity between classes in open-source and target datasets. This matrix is used in two key steps: 1) bridging the modality gap by transferring gap vectors (differences between image and text embeddings) from open-source to target datasets, thus improving the use of text as image proxies; and 2) bridging the capability gap by transferring ranking information from open-source to target datasets, improving the prediction of VLM performance on the target dataset. Finally, SWAB combines these two predictions to generate a final ranking of VLMs.

read the caption

Figure 3: The workflow of SWAB. SWAB first constructs a transport matrix γ* ∈ Rks×kt using optimal transport, based on textual semantic similarity between classes in the open-source datasets Cs = {c1,…, cks} and the target dataset's classes CT = {c1,…, ckt}. Using this matrix, SWAB estimates VLM fm's class-specific gap vectors {ĝm,1,…} on the target dataset T from the gap vectors Gm ∈ Rks×d in the open-source datasets. These estimated gap vectors help modify text data to act as more effective substitutes for image data. The modified text data will then be input into the Ranker Model fR, which predicts VLM's performance rT,(1)m on the target dataset. Besides, SWAB also uses the transport matrix γ* to predict VLM's performance ranking on the target dataset based on VLM's class-specific rankings rs ∈ Rks on open-source datasets. Finally, SWAB combines these two ranking predictions rT,(1)m and rT,(2)m to determine the VLM's final ranking prediction.

🔼 This figure presents validation experiments to demonstrate the presence of two inherent challenges in Language-Only VLM Selection: Modality Gap and Capability Gap. The left subfigure (a) shows a comparison between predicted and actual zero-shot image classification accuracy using generated text data, revealing the poor alignment and highlighting the ineffectiveness of text data as image substitutes due to the Modality Gap. The right subfigure (b) illustrates the Capability Gap by showing the significant variation in VLM performance rankings across different datasets, demonstrating the unreliability of predicting dataset-specific performance from overall performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: Validation Experiments on the Modality Gap and Capability Gap. (a) Predicted VLMs' zero-shot image classification accuracy based on generated text data vs. VLM's true accuracy based on test images. Each point in the graph represents a model. From the result, we can find that the predicted accuracy poorly aligns with the true accuracy, indicating these text data are ineffective substitutes for image data. (b) We calculate the zero-shot image classification performance rankings of 43 VLMs across 23 datasets. We compute the average standard deviations and the mean value of differences between each VLM's maximum and minimum ranking. The result shows the performance of a VLM varies greatly across different datasets.

🔼 This figure presents validation experiments demonstrating the challenges in Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM). (a) shows a comparison of predicted vs. actual zero-shot image classification accuracy using generated text data as image proxies, revealing a significant discrepancy due to the ‘Modality Gap’. (b) illustrates the ‘Capability Gap’ by showing the inconsistent performance rankings of VLMs across different datasets, highlighting the difficulty in selecting a VLM based solely on general performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: Validation Experiments on the Modality Gap and Capability Gap. (a) Predicted VLMs' zero-shot image classification accuracy based on generated text data vs. VLM's true accuracy based on test images. Each point in the graph represents a model. From the result, we can find that the predicted accuracy poorly aligns with the true accuracy, indicating these text data are ineffective substitutes for image data. (b) We calculate the zero-shot image classification performance rankings of 43 VLMs across 23 datasets. We compute the average standard deviations and the mean value of differences between each VLM's maximum and minimum ranking. The result shows the performance of a VLM varies greatly across different datasets.

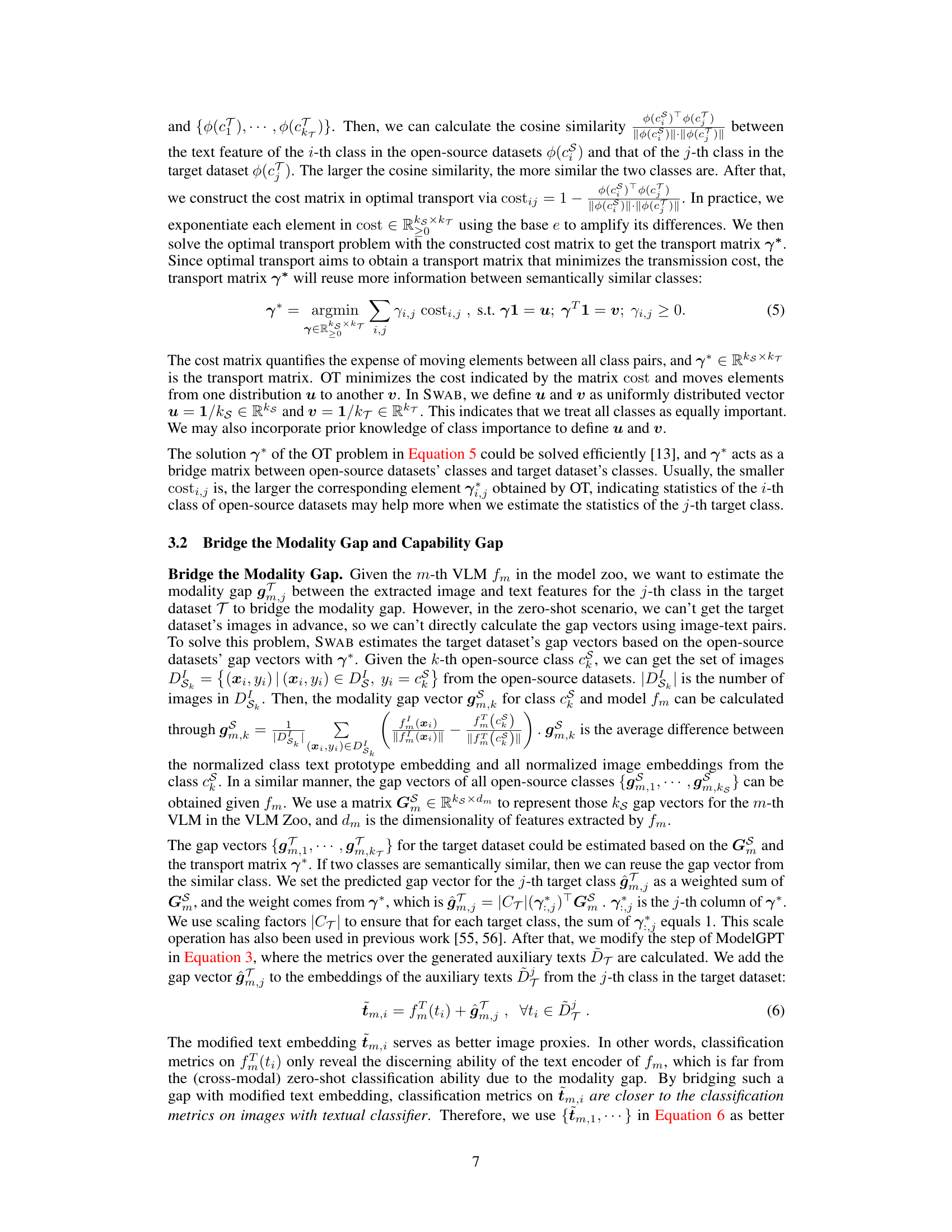

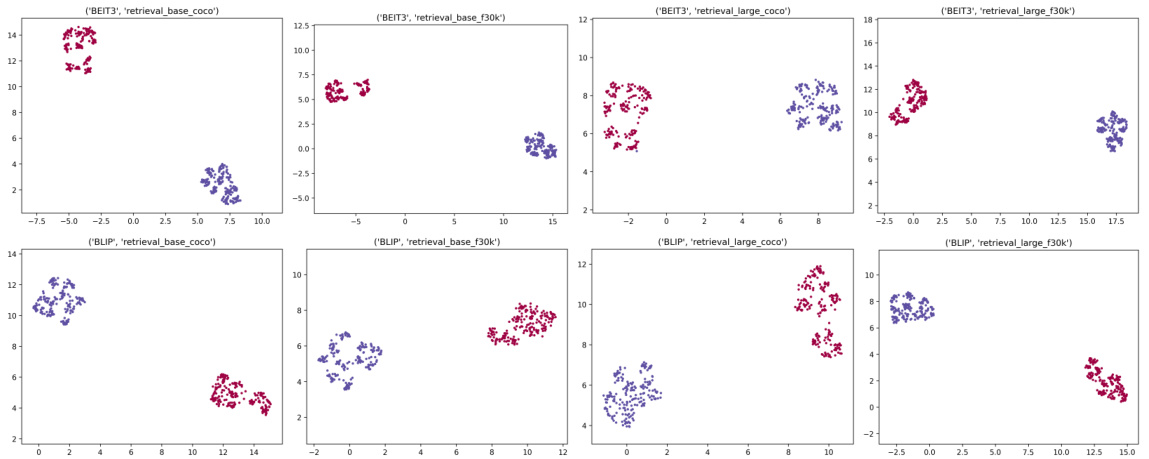

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying UMAP dimensionality reduction to image and text features extracted from various BEIT-3 and BLIP models. The plots visualize the separation or clustering of these features in a low-dimensional space, providing insights into the degree of modality gap between the image and text modalities for different models. Distinct clusters indicate a significant modality gap, where image and text features are not well-aligned in the model’s embedding space. Overlapping clusters suggest a smaller modality gap. The analysis helps to understand how well the models integrate image and text information and how this integration might affect their performance in zero-shot image classification tasks.

read the caption

Figure 6: UMAP visualization of image sample features and text sample features from different BEIT-3 and BLIP models.

🔼 This figure presents validation experiments demonstrating two key challenges in Language-Only VLM Selection (LOVM): the Modality Gap and the Capability Gap. Subfigure (a) shows a scatter plot comparing predicted VLM accuracy (using generated text data as image proxies) against the true accuracy (using actual images). The significant discrepancy highlights the ineffectiveness of using text alone. Subfigure (b) illustrates the Capability Gap by showing the wide variation in VLM performance across different datasets. The average standard deviation and the range of performance rankings for each VLM emphasize the inconsistency of a VLM’s general performance compared to its performance on a specific target dataset.

read the caption

Figure 2: Validation Experiments on the Modality Gap and Capability Gap. (a) Predicted VLMs' zero-shot image classification accuracy based on generated text data vs. VLM's true accuracy based on test images. Each point in the graph represents a model. From the result, we can find that the predicted accuracy poorly aligns with the true accuracy, indicating these text data are ineffective substitutes for image data. (b) We calculate the zero-shot image classification performance rankings of 43 VLMs across 23 datasets. We compute the average standard deviations and the mean value of differences between each VLM's maximum and minimum ranking. The result shows the performance of a VLM varies greatly across different datasets.

More on tables

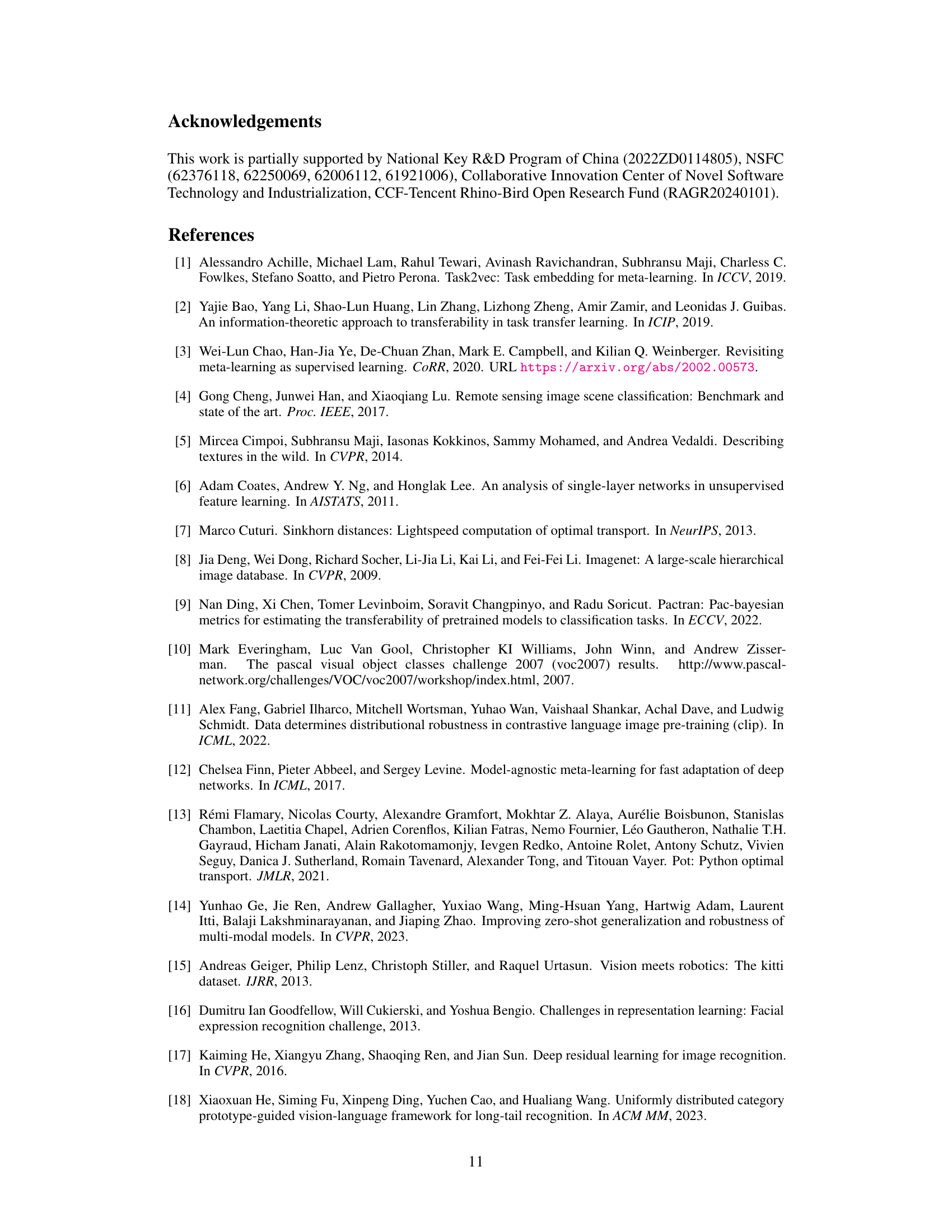

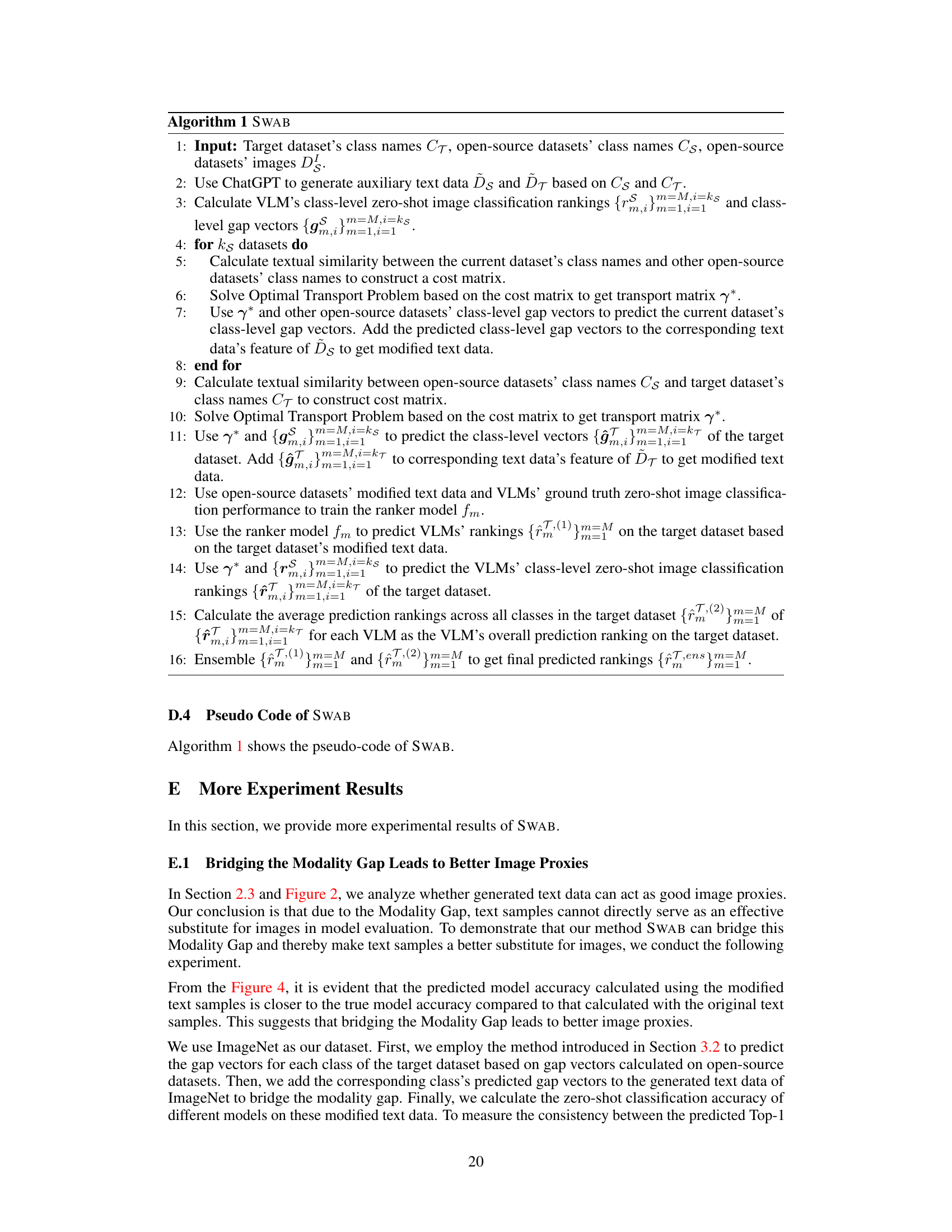

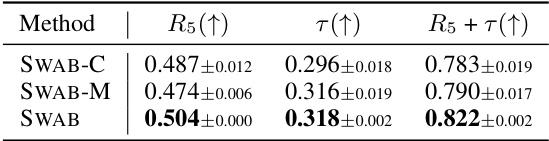

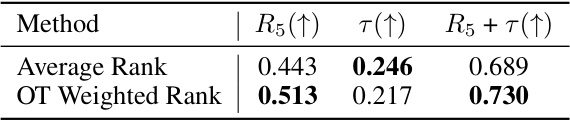

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results of the SWAB model. It shows the performance of three variants of SWAB: one that only bridges the Capability Gap (SWAB-C), one that only bridges the Modality Gap (SWAB-M), and one that bridges both gaps (SWAB). The results are presented in terms of Top-5 Recall (R5), Kendall’s Tau correlation (τ), and the sum of R5 and τ. The table demonstrates the importance of addressing both gaps for optimal performance. Higher values are better for all metrics.

read the caption

Table 2: Ablation Study of SWAB. SWAB-C, SWAB-M, and SWAB indicates only bridging the Capability Gap, only bridging the Modality Gap, and bridging both gaps in SWAB.

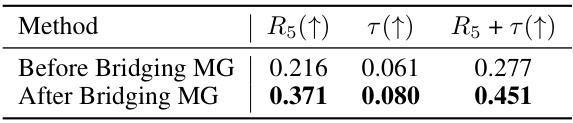

🔼 This table presents the results of using the OT Weighted Rank method for VLM selection on the LOVM benchmark, comparing its performance before and after incorporating the capability gap bridging technique. It shows the Top-5 Recall (R5), Kendall’s Rank Correlation (τ), and the sum of these two metrics (R5 + τ) for both scenarios. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of bridging the capability gap in improving the accuracy of VLM selection.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of on the LOVM before and after bridging the Capability Gap.

🔼 This table presents the results of before and after applying the modality gap bridging technique in SWAB. The metrics used are Top-5 Recall (R5), Kendall’s Rank Correlation (τ), and the sum of R5 and τ (R5+τ). Higher values indicate better performance. The results demonstrate the positive impact of bridging the modality gap on improving the accuracy of VLM selection in SWAB.

read the caption

Table 4: Results of before and after bridging the Modality Gap (MG).

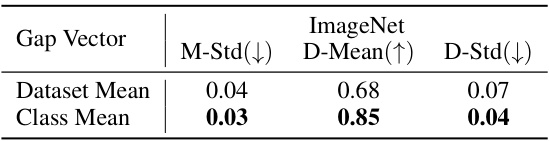

🔼 This table presents the results of measuring the consistency of gap vectors within the same dataset and within each class. Three metrics are used: the standard deviation of gap vector magnitudes (M-Std), the mean cosine similarity between gap vectors and their corresponding mean gap vectors (D-Mean), and the standard deviation of these cosine similarities (D-Std). Lower values for M-Std and D-Std indicate higher consistency, while higher values for D-Mean indicate higher consistency. The results are shown for the ImageNet dataset.

read the caption

Table 5: Results of metrics measuring gap vectors' consistency belonging to the same dataset or the same class. M: Magnitude, D: Direction.

🔼 This table shows the performance of SWAB-M on the LOVM benchmark. It compares the results of using dataset-level mean gap vectors versus class-level mean gap vectors for bridging the modality gap. The metrics used are Top-5 Recall (R5), Kendall’s Rank Correlation (τ), and the sum of the two (R5+τ). Higher values for R5 and τ indicate better performance. The results demonstrate that using class-level mean gap vectors leads to a significant improvement in the performance of SWAB-M.

read the caption

Table 6: Results of SWAB-M on the LOVM Benchmark using the dataset-level mean gap vectors and class-level mean gap vectors.

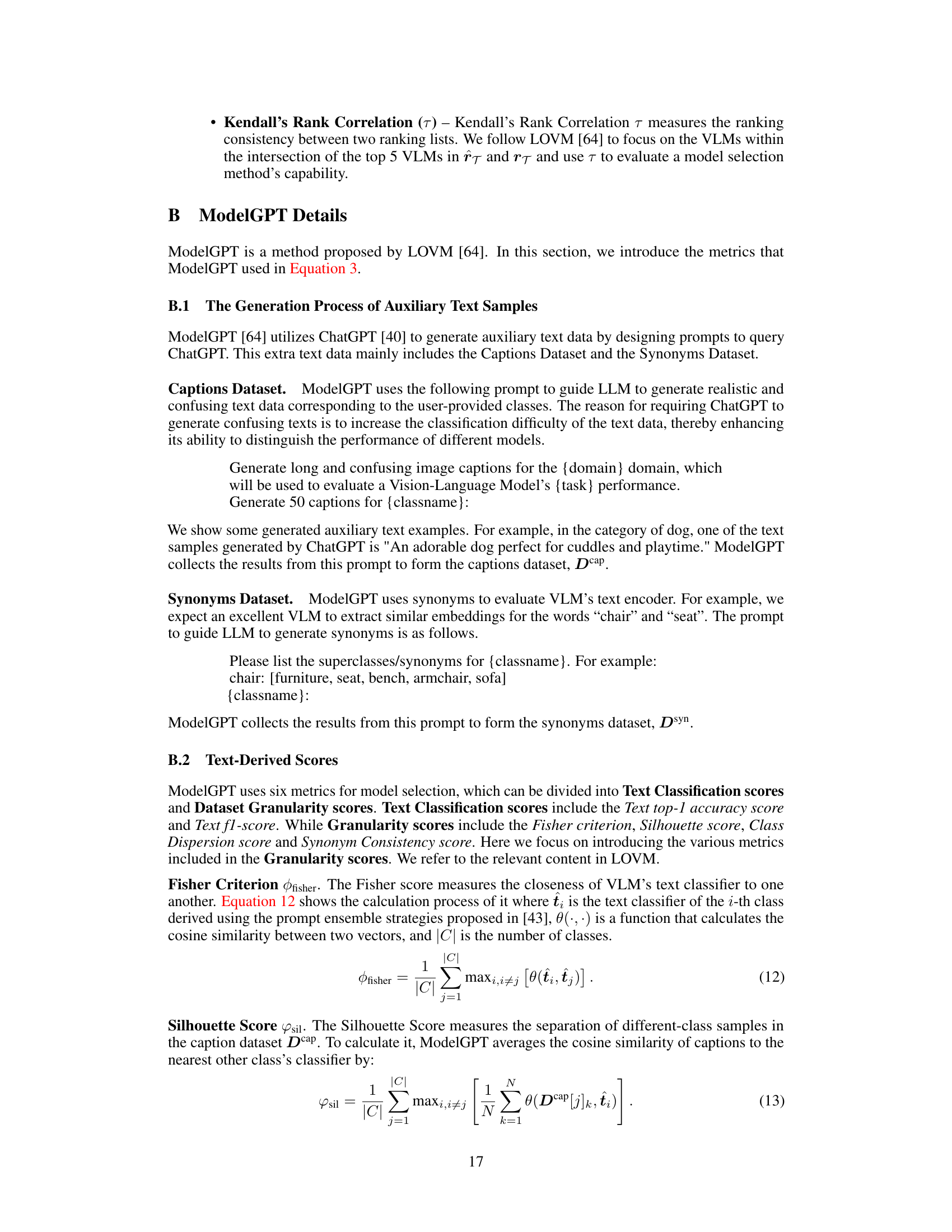

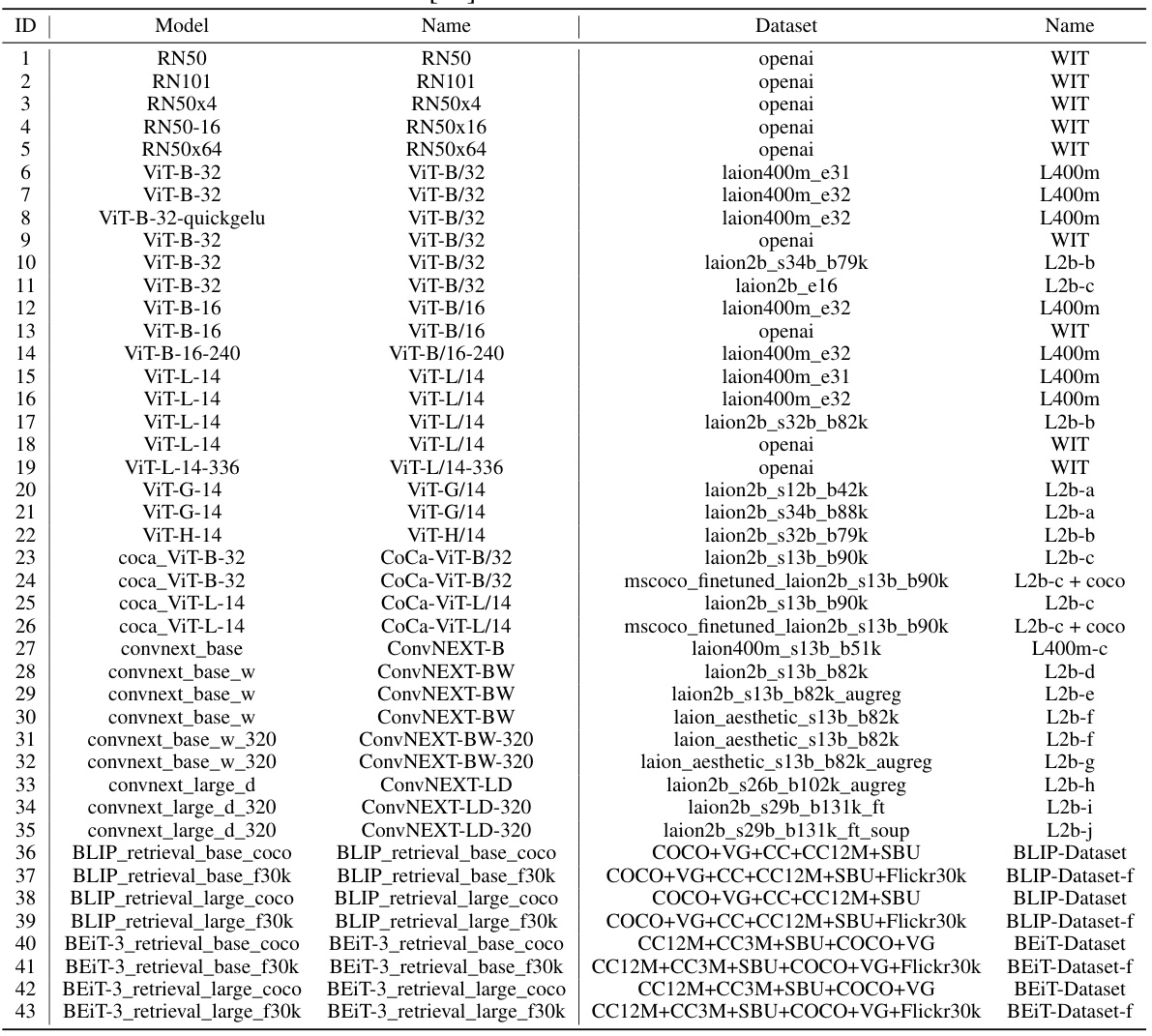

🔼 This table lists the details of the 43 vision-language models used in the LOVM benchmark. It provides information for each model, including the model name, the dataset used for pre-training, and other relevant details. This information is crucial to understanding the diversity of models included in the benchmark and how those differences might influence the results of the model selection process.

read the caption

Table 7: The detailed information of 43 models used in the LOVM Benchmark. Some of the information in the table comes from [64].

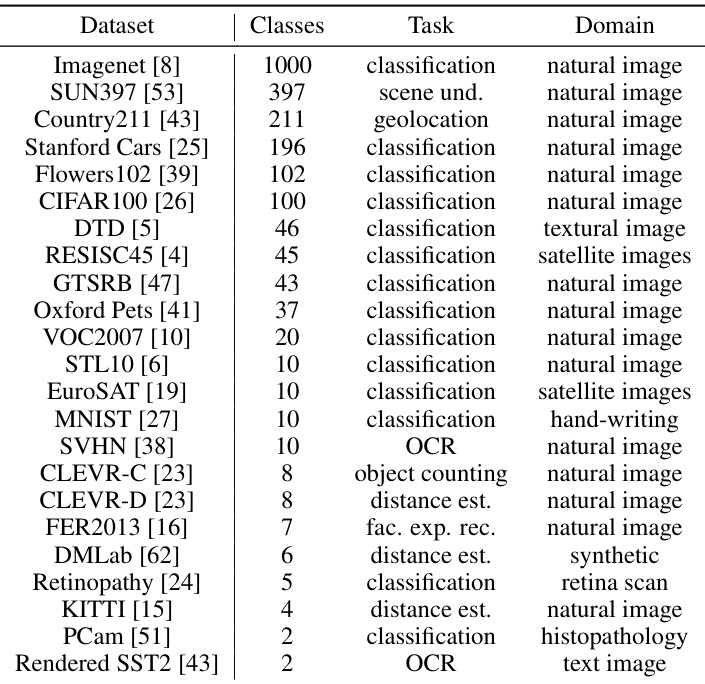

🔼 This table lists 23 image classification datasets used in the LOVM benchmark. For each dataset, it shows the number of classes, the type of task (classification, scene understanding, geolocation, object counting, distance estimation, facial expression recognition, or OCR), and the domain of the images (natural images, satellite images, textural images, synthetic images, retina scans, hand-writing, or histopathology). The variety of datasets ensures that experimental results reflect the performance of VLM model selection methods in real-world situations.

read the caption

Table 8: Detailed information of 23 tasks used in the LOVM Benchmark. This table comes from [64].

🔼 This table presents the results of the proposed SWAB method and several baseline methods on the original LOVM benchmark which consists of 35 pre-trained Vision-Language Models (VLMs) and 23 datasets. The metrics used to evaluate the performance are H-Score, NCE, LEEP, LogME, INB, Avg Rank, ModelGPT, and SWAB. The table shows the average performance across all 23 datasets, reporting Top-5 Recall (R5), Kendall’s Rank Correlation (τ), and the sum of these two metrics (R5 + τ) for each method. Higher values for R5 and τ indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 9: Results on LOVM's original VLM Zoo. We evaluate our method across 23 datasets and 35 pre-trained VLMs. The results are averaged over all datasets.

Full paper#