TL;DR#

Current 3D anomaly detection heavily relies on object-specific training data, limiting its applicability to real-world scenarios where such data might be scarce due to privacy concerns or unavailability. This problem is further amplified in zero-shot settings where training samples of the target object are completely unavailable. This paper addresses this crucial yet under-explored problem.

PointAD, the proposed method, innovatively leverages the power of CLIP, a vision-language model, to overcome the limitations of traditional 3D anomaly detection methods. By rendering 3D data into multiple 2D views and integrating point and pixel information via hybrid representation learning, PointAD learns generic anomaly patterns that enable zero-shot detection on diverse unseen objects. Experiments demonstrate PointAD’s superior performance across various datasets and the plug-and-play integration of RGB information enhances the understanding of 3D anomalies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in 3D anomaly detection because it tackles the largely unexplored area of zero-shot learning. It introduces a novel method that avoids the need for object-specific training data and presents a new unified framework for understanding 3D anomalies from both point and pixel information. This is highly relevant given data scarcity in real-world 3D applications and opens up new avenues for efficient and generalizable anomaly detection systems. The results are promising and may significantly impact fields where acquiring labeled training data is difficult or impossible.

Visual Insights#

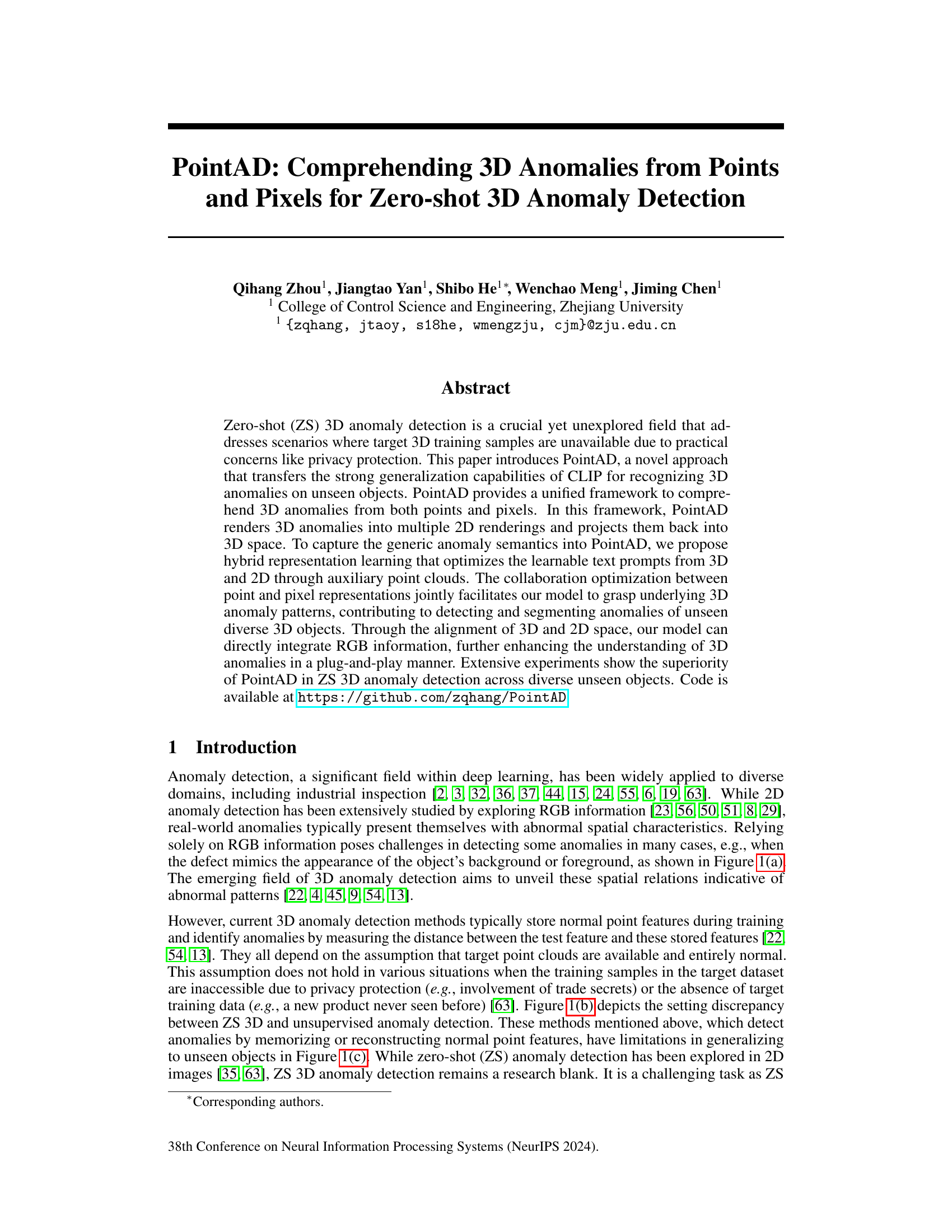

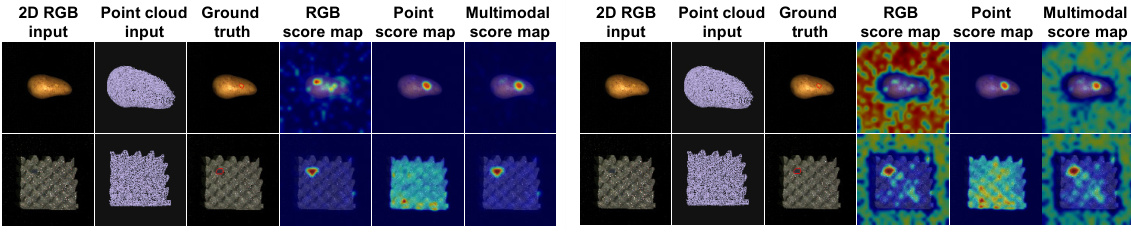

🔼 This figure highlights the challenges of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection by comparing different modalities (RGB vs. point cloud). It shows that relying solely on RGB information can be insufficient for detecting anomalies that blend with the background or foreground. Point clouds, by capturing spatial relations, prove more effective in such cases. The figure also illustrates the difference between zero-shot (ZS) and unsupervised anomaly detection settings, emphasizing the greater difficulty of ZS due to the lack of training samples for specific target objects.

read the caption

Figure 1: Motivation of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. (a): Top: The hole on the cookies presents a similar appearance to the background. Bottom: Surface damage on the potato is unapparent to the object foreground. In these cases, leveraging RGB information makes it difficult to detect anomalies that imitate the color patterns of the background or foreground. However, effective recognition can be achieved by modeling the point relations within corresponding point clouds. (b) and (c) depicts the setting difference of ZS and unsupervised manner.

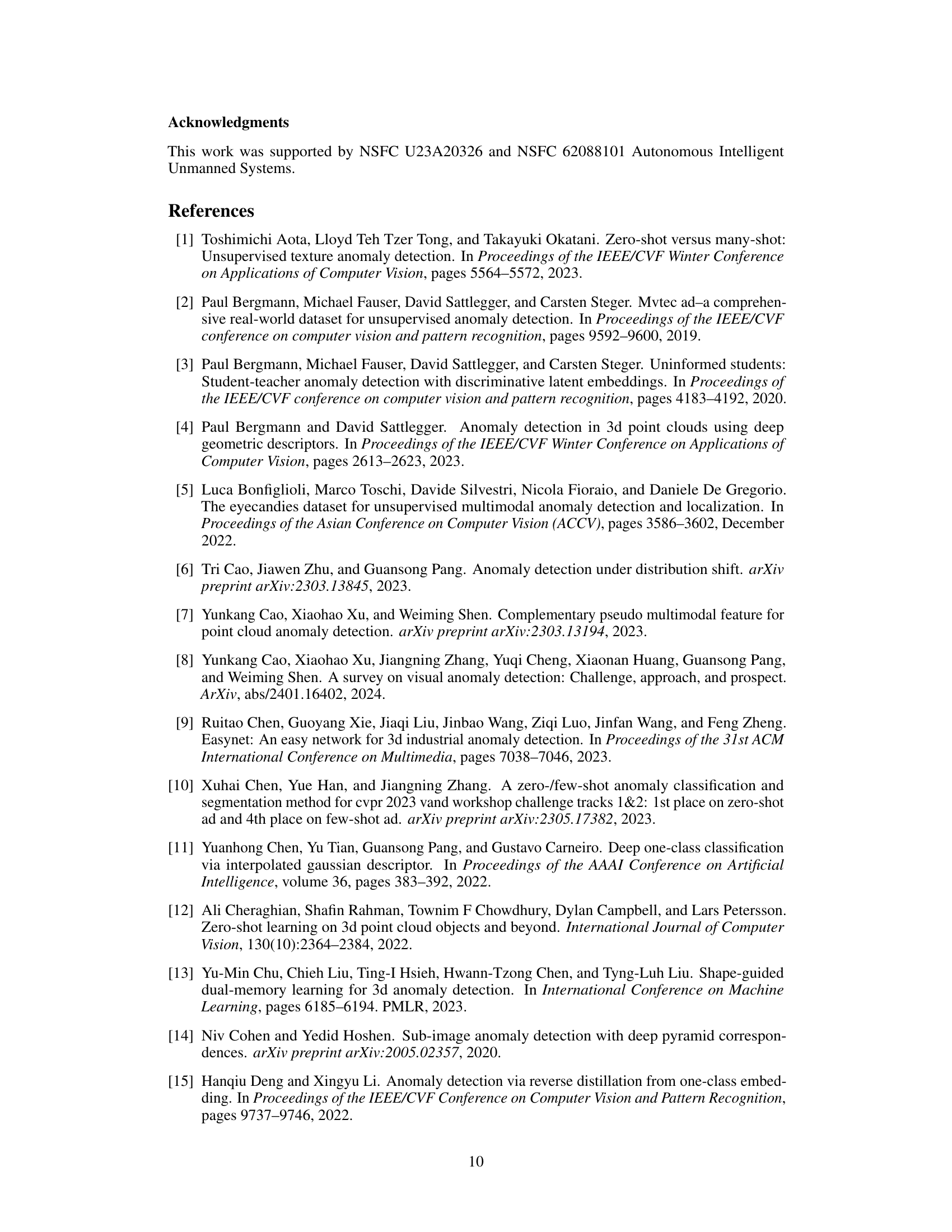

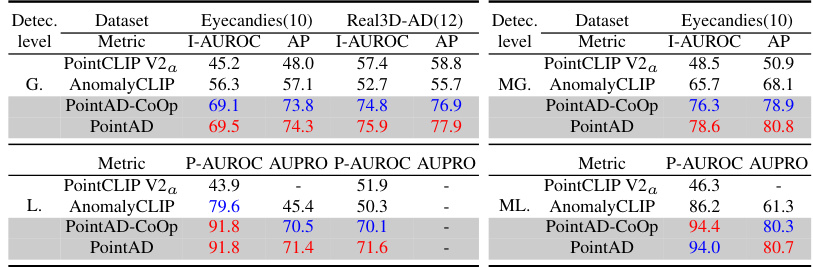

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of several zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection methods on three public datasets: MVTec3D-AD, Eyecandies, and Real3D-AD. The ‘one-vs-rest’ setting means that for each object category, the model is trained on all other categories and tested on that specific category. The table shows the I-AUROC (Image-level Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) and AP (Average Precision) for each method and dataset. Higher values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection in 'one-vs-rest' setting.

In-depth insights#

Zero-Shot 3D AD#

Zero-shot 3D anomaly detection (3D AD) tackles the challenge of identifying anomalies in unseen 3D objects, without requiring any training data from those specific objects. This is crucial for scenarios where acquiring training data is expensive, time-consuming, or impossible due to privacy or other constraints. Existing methods often rely on supervised learning or learning from normal data only, which limits their generalizability to new objects. PointAD, described in this paper, is a novel zero-shot approach that leverages the strong generalization capabilities of CLIP, a vision-language model, to learn generic anomaly representations. By rendering 3D objects from multiple views and combining these 2D renderings with 3D point cloud data, PointAD effectively captures both global and local anomaly patterns across various unseen objects. The hybrid representation learning jointly optimizes text prompts, further improving the model’s ability to discern subtle anomalies in unseen data. This approach significantly enhances the robustness and generalization of zero-shot 3D AD, opening up new possibilities for real-world applications.

Point & Pixel Fusion#

A hypothetical ‘Point & Pixel Fusion’ section in a 3D anomaly detection paper would likely detail how the model integrates data from both point clouds and RGB images. This fusion is crucial because point clouds provide precise geometric information, while RGB images offer rich visual context. A successful fusion strategy would leverage the strengths of each data modality to overcome limitations inherent in using either alone. For instance, point cloud data might be more robust to background clutter or subtle surface defects, while RGB data is better for capturing color or texture anomalies that are not easily expressed geometrically. Effective fusion could involve feature concatenation, attention mechanisms, or a multi-modal learning architecture. The paper would ideally discuss various fusion techniques and provide a comparative analysis, highlighting the chosen method’s effectiveness in improving accuracy and robustness of 3D anomaly detection, particularly for unseen objects in zero-shot settings. Challenges, such as handling inconsistencies between point cloud and image representations or computationally expensive fusion methods, would also require attention. Ultimately, a compelling ‘Point & Pixel Fusion’ section would demonstrate a synergistic approach that significantly enhances anomaly detection performance.

CLIP Transfer Learning#

CLIP transfer learning leverages the powerful image-text embeddings learned by CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) to improve performance on downstream tasks where labeled data is scarce. The core idea is to transfer CLIP’s learned visual representations, which are capable of understanding complex visual concepts, to a new 3D domain. This eliminates the need for extensive 3D training data which is often difficult and expensive to obtain. A key advantage is its generalization capability; CLIP’s knowledge of object recognition and semantics aids in identifying anomalies in unseen objects, enhancing zero-shot or few-shot learning. However, successful transfer requires careful consideration of the differences between 2D images and the 3D point cloud data. The process may involve rendering 3D data into multiple 2D views for compatibility with CLIP, followed by mapping the learned 2D representations back to 3D space. Challenges include aligning feature spaces and handling the loss of information during the 2D-3D conversion. While promising, the performance of CLIP transfer learning in 3D relies heavily on the quality of the 2D renderings and the effectiveness of the alignment techniques used.

Multi-View Rendering#

The effectiveness of 3D anomaly detection models hinges on their ability to capture comprehensive spatial relationships within point cloud data. Multi-view rendering addresses this challenge by projecting 3D point clouds into multiple 2D renderings from various viewpoints. This strategy leverages the strengths of 2D convolutional neural networks to extract rich feature representations from each 2D view. By then projecting these 2D features back into 3D space, the model gains a holistic understanding of the 3D shape and its anomalies, going beyond what’s achievable with single-view projections. Depth map projections are insufficient for fine-grained anomaly semantics because they lack sufficient resolution. Therefore, high-precision rendering is adopted to meticulously preserve the original 3D information. This multi-view approach significantly enhances the model’s ability to identify subtle spatial variations indicative of anomalies, leading to improved accuracy in anomaly detection and segmentation.

Future of PointAD#

The future of PointAD hinges on addressing its current limitations and expanding its capabilities. Improving the robustness to various rendering conditions (lighting, viewpoint, resolution) is crucial for real-world applicability. This could involve exploring more advanced rendering techniques or incorporating data augmentation strategies that account for these variations during training. Expanding to handle point cloud incompleteness or noise is another critical area; PointAD’s performance degrades with significant occlusion or low-density point clouds, limiting its use in practical scenarios. Methods to handle missing data or noise robustly, perhaps using imputation or noise-reduction techniques, would be beneficial. Exploring different vision-language models beyond CLIP might reveal even stronger generalization capabilities. Furthermore, integrating PointAD with other 3D data processing tools and frameworks would streamline its integration into various applications. Finally, investigating the effectiveness of PointAD in different domains and application areas beyond anomaly detection is also warranted, as its strong generalization ability suggests potential for wider usage.

More visual insights#

More on figures

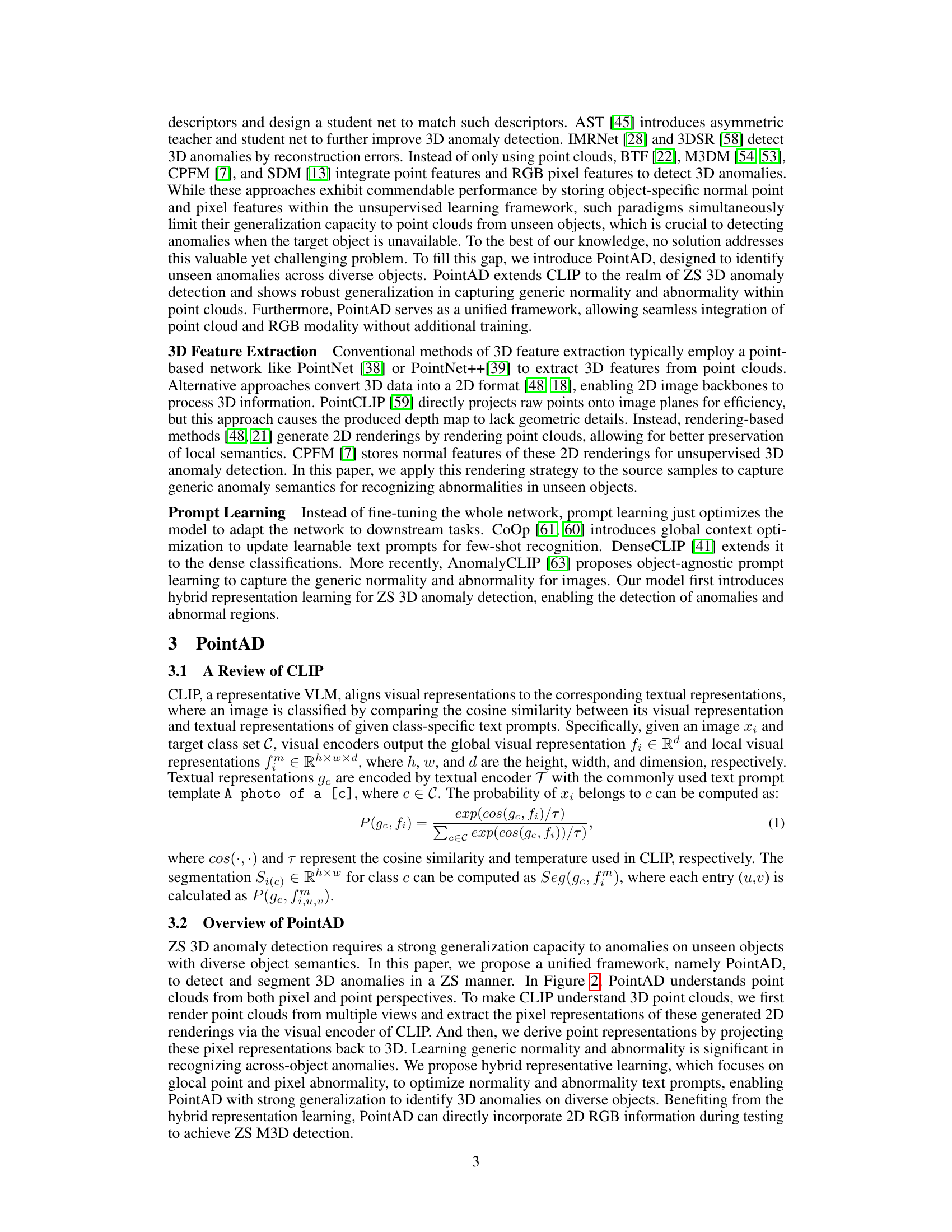

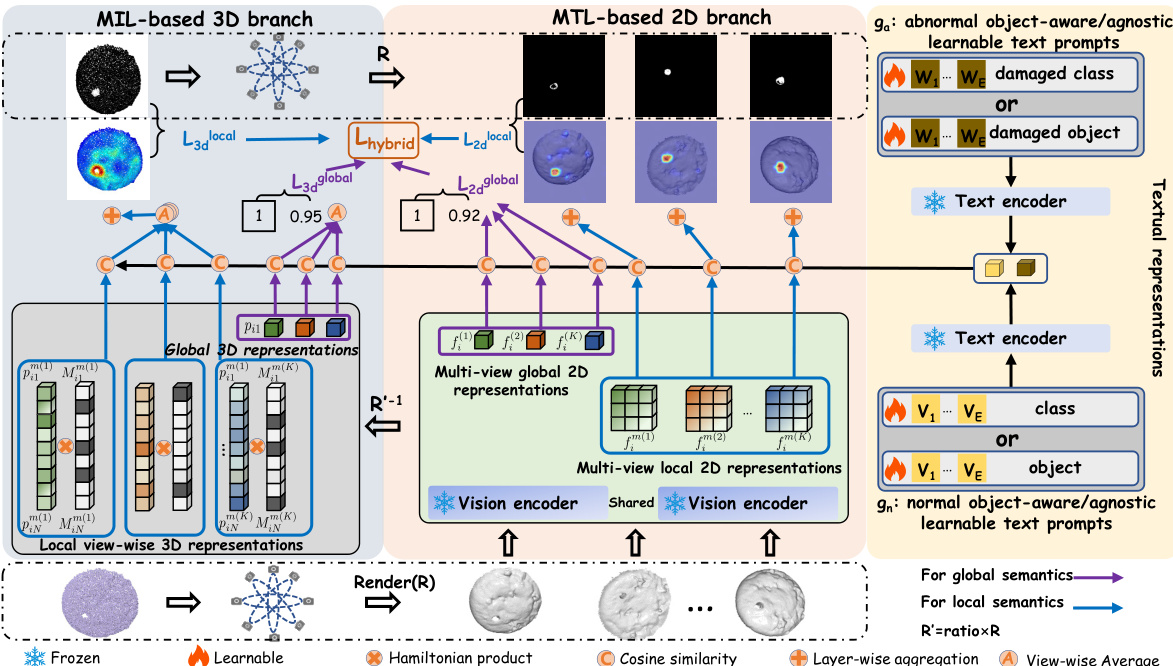

🔼 PointAD, a unified framework for zero-shot 3D anomaly detection, leverages CLIP’s capabilities by rendering 3D point clouds into multiple 2D views. It extracts both global and local 2D features using CLIP’s vision encoder, then projects these features back into 3D space. Hybrid representation learning optimizes text prompts from both 2D and 3D data via auxiliary point clouds, allowing PointAD to identify anomalies across various unseen objects. The figure details the multi-view rendering process, feature extraction, and hybrid representation learning which is the core idea behind the PointAD approach.

read the caption

Figure 2: Framework of PointAD. To transfer the strong generalization of CLIP from 2D to 3D, point clouds and corresponding ground truths are respectively rendered into 2D renderings from multi-view. Then, vision encoder of CLIP extracts the renderings to derive 2D global and local representations. These representations are transformed into glocal 3D point representations to learn 3D anomaly semantics within point clouds. Finally, we align the normality and abnormality from both point perspectives (multiple instance learning) and pixel perspectives (multiple task learning) and propose a hybrid loss to jointly optimize the text embeddings from the learnable normality and abnormality text prompts, capturing the underlying generic anomaly patterns.

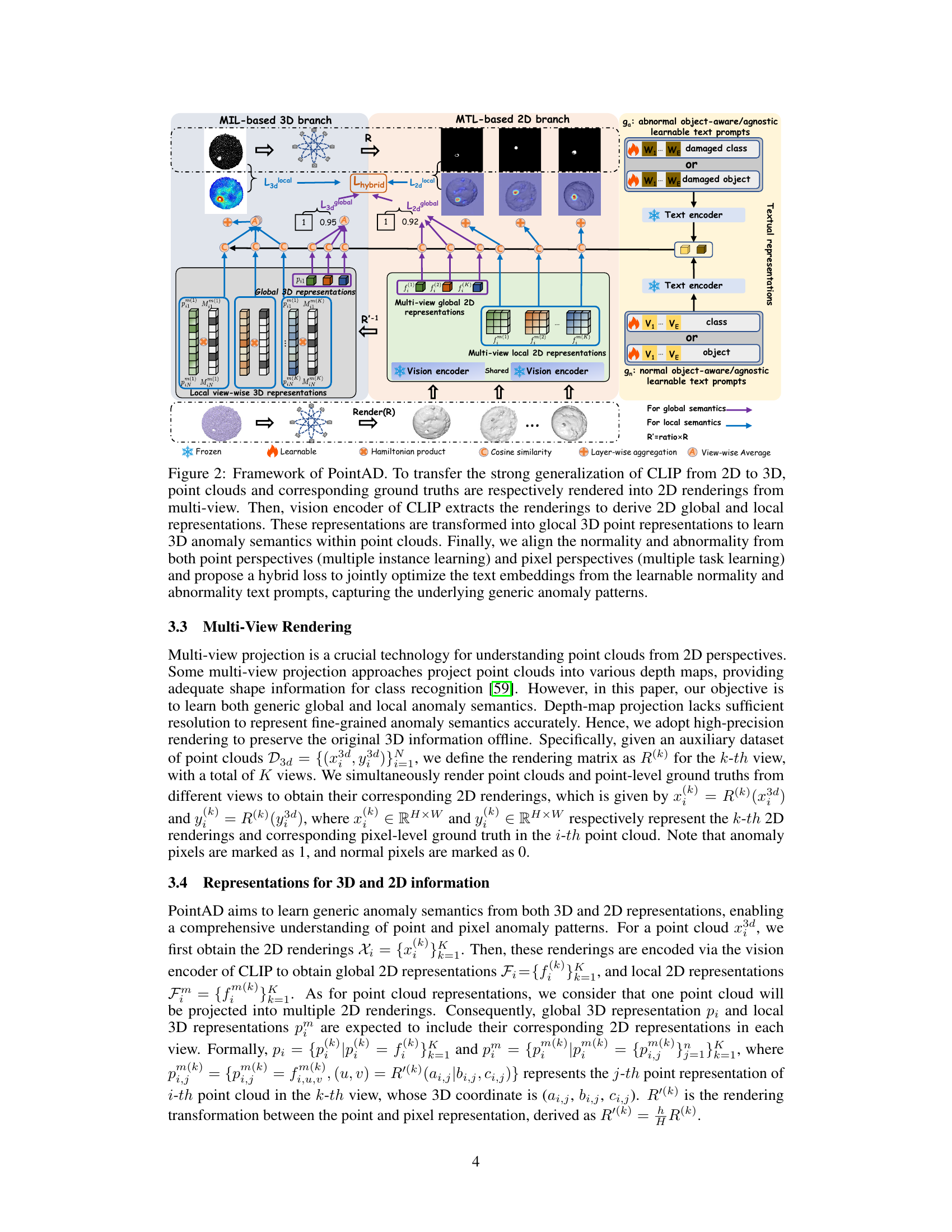

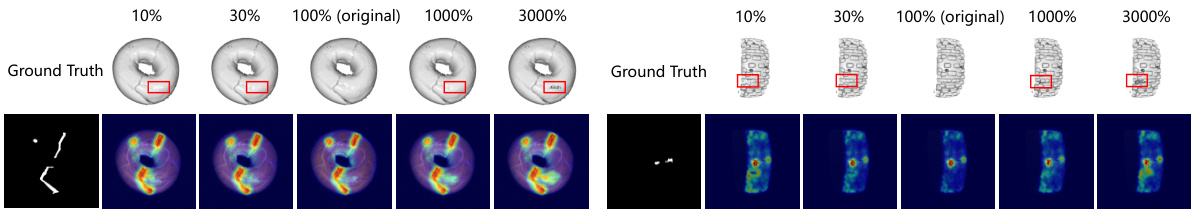

🔼 This figure shows the process of PointAD for zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. Point clouds of various objects are fed into the model. PointAD generates multiple 2D renderings of each 3D point cloud from different viewpoints. These 2D renderings are processed to generate 2D anomaly score maps. Finally, these 2D maps are projected back to 3D space to create a 3D anomaly score map. The figure showcases examples of these processes and the resulting anomaly score maps for different object types.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization on anomaly score maps in ZS 3D anomaly detection. Point clouds of diverse objects are input into PointAD to generate 2D and 3D representations. Each row visualizes the anomaly score maps of 2D renderings from different views, and the final point score maps are also presented. More visualizations are provided in Appendix J.

🔼 This figure illustrates the challenges of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. Panel (a) shows that relying solely on RGB information for anomaly detection can be problematic when the anomaly visually blends with the background or foreground, as seen in the examples of a hole in a cookie and surface damage on a potato. In contrast, utilizing point cloud data allows for better detection due to the distinct spatial relationships present within the point cloud. Panel (b) contrasts zero-shot (ZS) and unsupervised anomaly detection settings. Panel (c) demonstrates how performance degrades in the case of zero-shot anomaly detection when using an object-specific model (unsupervised) compared to an object-agnostic model (zero-shot).

read the caption

Figure 1: Motivation of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. (a): Top: The hole on the cookies presents a similar appearance to the background. Bottom: Surface damage on the potato is unapparent to the object foreground. In these cases, leveraging RGB information makes it difficult to detect anomalies that imitate the color patterns of the background or foreground. However, effective recognition can be achieved by modeling the point relations within corresponding point clouds. (b) and (c) depicts the setting difference of ZS and unsupervised manner.

🔼 This figure illustrates the PointAD framework, which transfers CLIP’s strong generalization ability from 2D to 3D. It shows how 3D point clouds are rendered into multiple 2D views, processed by CLIP’s vision encoder to extract 2D representations, and then projected back to 3D to learn 3D anomaly semantics. A hybrid representation learning method aligns normality and abnormality from both point and pixel perspectives using multiple instance learning (MIL) and multi-task learning (MTL). The learnable text prompts are jointly optimized to capture underlying generic anomaly patterns, enabling zero-shot 3D anomaly detection.

read the caption

Figure 2: Framework of PointAD. To transfer the strong generalization of CLIP from 2D to 3D, point clouds and corresponding ground truths are respectively rendered into 2D renderings from multi-view. Then, vision encoder of CLIP extracts the renderings to derive 2D global and local representations. These representations are transformed into glocal 3D point representations to learn 3D anomaly semantics within point clouds. Finally, we align the normality and abnormality from both point perspectives (multiple instance learning) and pixel perspectives (multiple task learning) and propose a hybrid loss to jointly optimize the text embeddings from the learnable normality and abnormality text prompts, capturing the underlying generic anomaly patterns.

🔼 This figure visualizes the PointAD model’s performance on zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. Multiple views of a 3D point cloud are rendered into 2D images, which are processed by the model to create anomaly score maps. These 2D score maps are then projected back into 3D space to generate a final 3D anomaly score map, which highlights the anomalous regions within the 3D point cloud. The figure demonstrates how PointAD integrates information from multiple 2D views to improve its understanding of 3D anomalies.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization on anomaly score maps in ZS 3D anomaly detection. Point clouds of diverse objects are input into PointAD to generate 2D and 3D representations. Each row visualizes the anomaly score maps of 2D renderings from different views, and the final point score maps are also presented. More visualizations are provided in Appendix J.

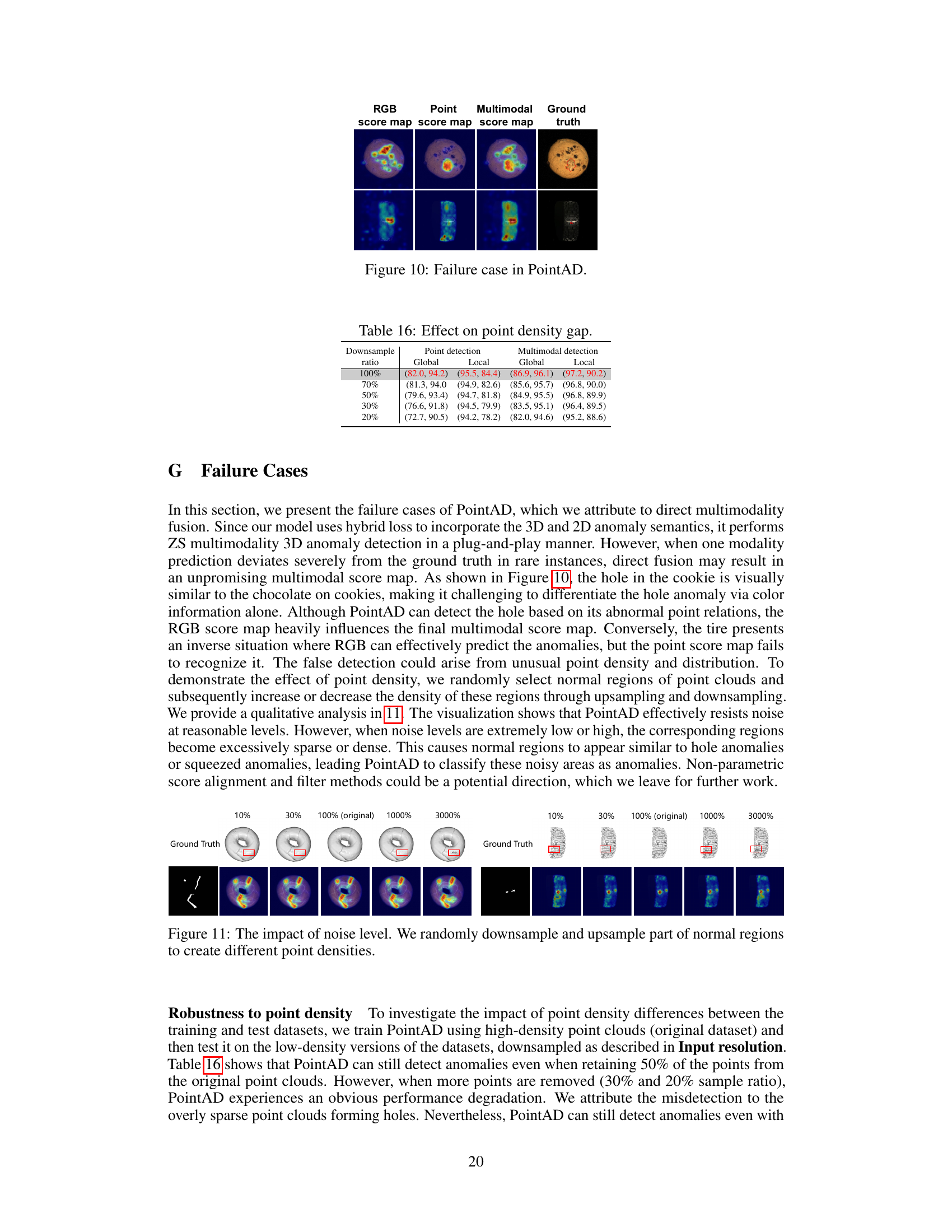

🔼 This figure shows the impact of different lighting conditions on the PointAD model’s performance. The top row displays rendered images of a bagel with varying lighting intensities, from very dim (‘Lighting–’) to very bright (‘Lighting++’). The bottom row shows the corresponding anomaly score maps generated by PointAD. The experiment demonstrates the model’s robustness to variations in lighting.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualization with different rendering lighting.

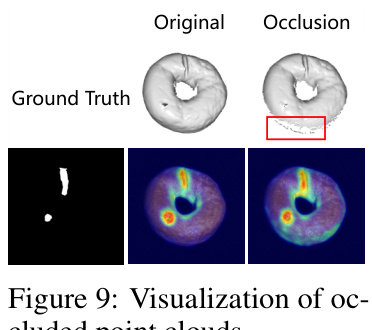

🔼 The figure visualizes the impact of point cloud occlusions on anomaly detection. It shows a bagel point cloud with an anomaly (a hole) in the original and an occluded version. The occluded version has a portion of the anomaly masked, simulating a scenario where part of the defect is hidden from view. Below, the anomaly score maps from different perspectives (views) are shown for both the original and the occluded point cloud. This illustrates how occlusions affect the model’s ability to detect anomalies, highlighting the challenge of robust anomaly detection in real-world scenarios with incomplete or partially obscured data.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visualization of occluded point clouds.

🔼 This figure illustrates the challenges of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. Subfigure (a) shows examples where relying on RGB information alone is insufficient for detecting anomalies because the anomalies visually blend with the background or foreground. Subfigure (b) highlights the difference between zero-shot and unsupervised settings for 3D anomaly detection, with zero-shot lacking training samples for the target object. Subfigure (c) demonstrates how the performance of traditional methods degrades significantly when applied to zero-shot scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 1: Motivation of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. (a): Top: The hole on the cookies presents a similar appearance to the background. Bottom: Surface damage on the potato is unapparent to the object foreground. In these cases, leveraging RGB information makes it difficult to detect anomalies that imitate the color patterns of the background or foreground. However, effective recognition can be achieved by modeling the point relations within corresponding point clouds. (b) and (c) depicts the setting difference of ZS and unsupervised manner.

🔼 This figure illustrates the limitations of using only RGB information for 3D anomaly detection and the advantages of PointAD’s approach. Subfigure (a) shows examples where RGB alone fails to distinguish anomalies from background or normal object features (a hole in cookies that looks like the background, surface damage on a potato that is hard to see). Subfigure (b) contrasts zero-shot (ZS) and unsupervised settings for anomaly detection, highlighting that ZS requires more generalization ability. Subfigure (c) demonstrates performance degradation in unsupervised methods when applied to zero-shot scenarios, which are addressed by PointAD.

read the caption

Figure 1: Motivation of zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. (a): Top: The hole on the cookies presents a similar appearance to the background. Bottom: Surface damage on the potato is unapparent to the object foreground. In these cases, leveraging RGB information makes it difficult to detect anomalies that imitate the color patterns of the background or foreground. However, effective recognition can be achieved by modeling the point relations within corresponding point clouds. (b) and (c) depicts the setting difference of ZS and unsupervised manner.

🔼 This figure showcases PointAD’s ability to generate anomaly score maps from diverse 3D objects. It demonstrates how PointAD processes 3D point cloud data by first creating multiple 2D renderings from various viewpoints. Each row shows a different object with its corresponding 2D renderings and resulting anomaly score maps. The final column presents the aggregated point cloud anomaly score map. This visually illustrates PointAD’s approach to comprehending 3D anomalies using both points and pixel information from 2D renderings.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization on anomaly score maps in ZS 3D anomaly detection. Point clouds of diverse objects are input into PointAD to generate 2D and 3D representations. Each row visualizes the anomaly score maps of 2D renderings from different views, and the final point score maps are also presented. More visualizations are provided in Appendix J.

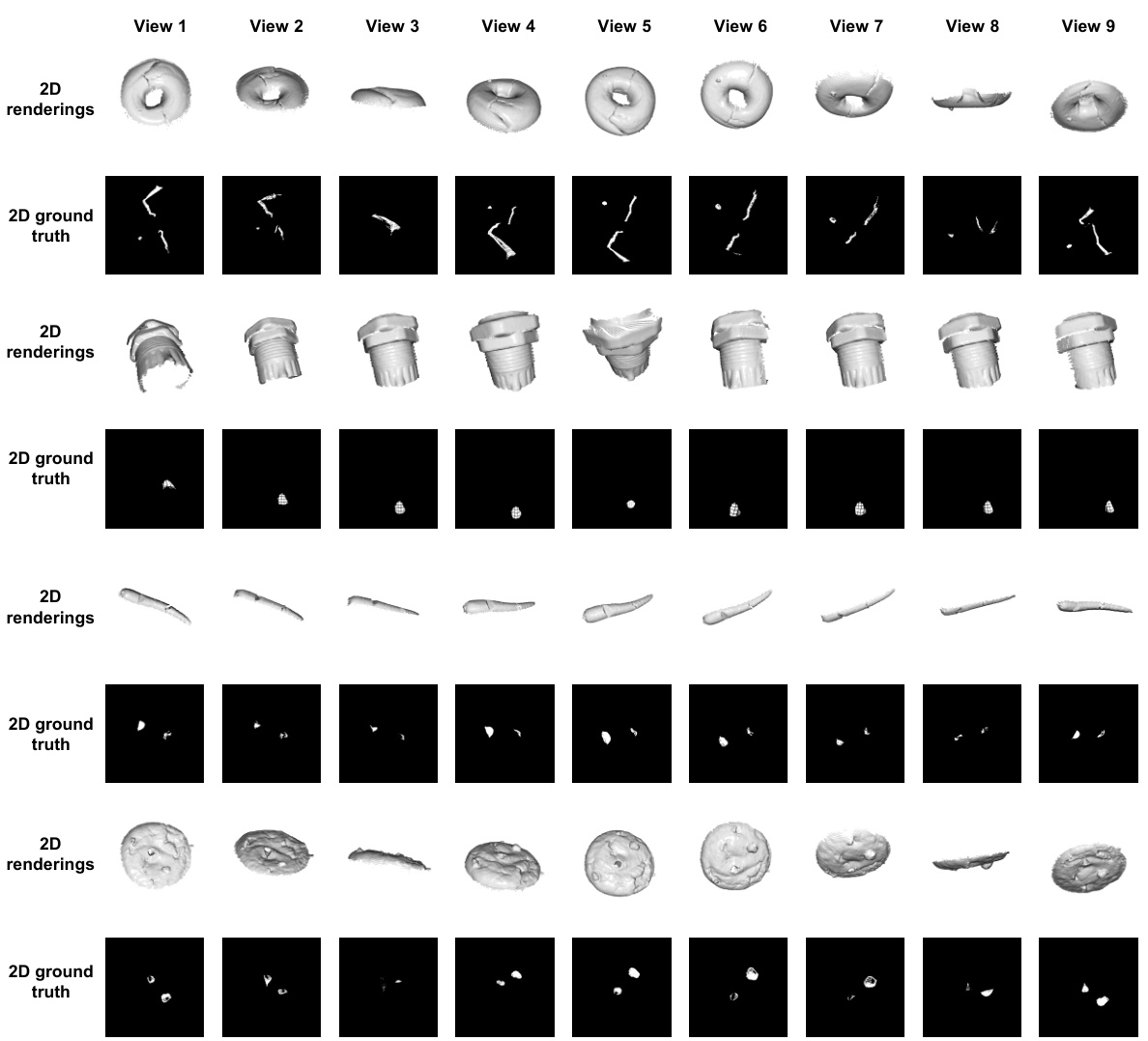

🔼 This figure visualizes the 2D renderings generated from multiple viewpoints (K=9) of several 3D point clouds, along with their corresponding ground truth anomaly masks. Each row represents a different 3D object. The visualizations illustrate how PointAD processes 3D point cloud data by projecting it into multiple 2D views to capture diverse perspectives of the object’s shape and anomalies. The comparison between the renderings and ground truth helps illustrate the accuracy of the 2D representation learned by the model.

read the caption

Figure 13: Visualization about 2D renderings and ground truth from different views (K = 9).

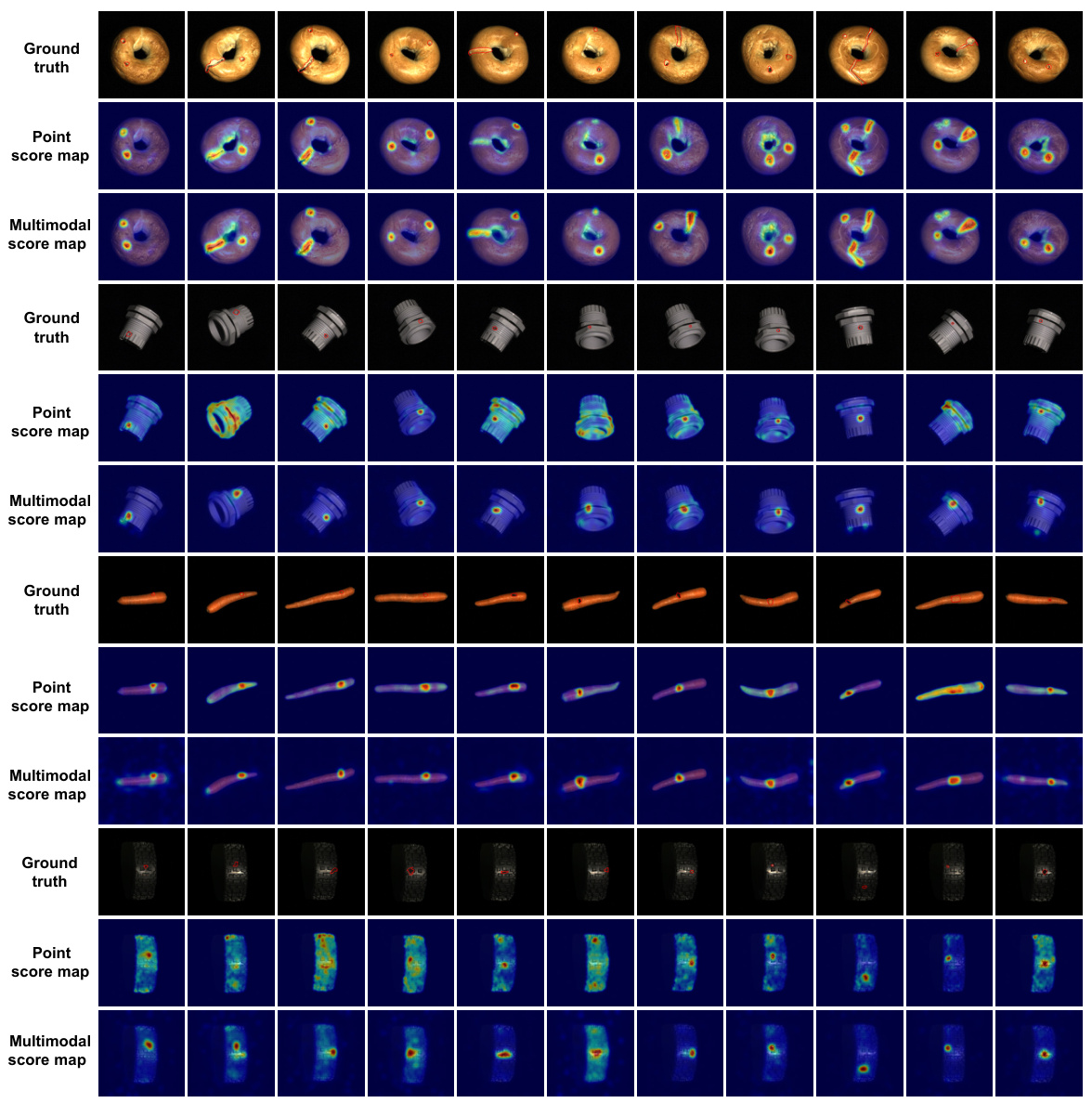

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of PointAD’s anomaly detection on four different objects from the MVTec3D-AD dataset. For each object, it shows the ground truth anomaly mask, the point-based anomaly score map, and the final multimodal anomaly score map (combining point and pixel information). The visualization helps demonstrate how PointAD integrates both point cloud and RGB information for more accurate anomaly detection. Different anomaly types (holes, surface damages) are shown across different object instances.

read the caption

Figure 14: Visualization of point and multimodal score maps in PointAD, which is pre-trained on cookie object.

More on tables

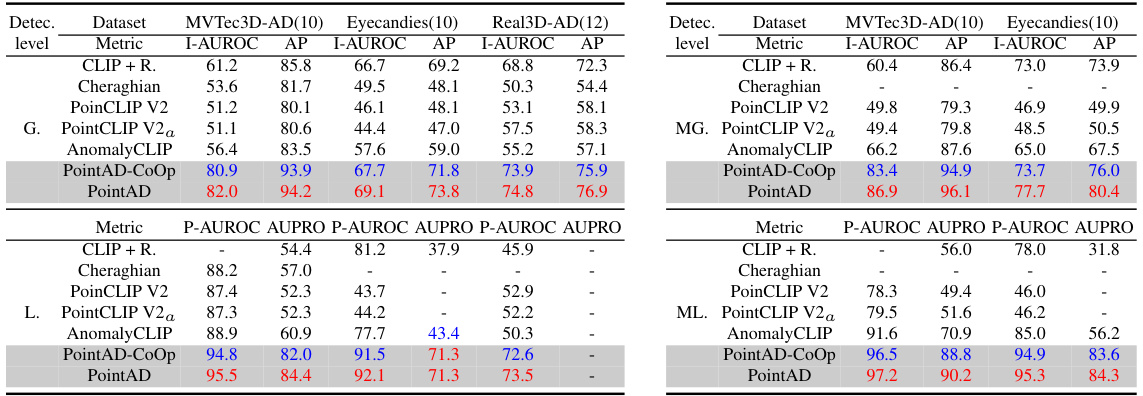

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection methods across different datasets. It highlights the generalization capabilities of the models by testing on datasets unseen during training. The metrics used are I-AUROC and AP for overall detection performance, and P-AUROC and AUPRO for local anomaly segmentation. The table allows for a comparison of PointAD’s performance against existing methods in a cross-dataset scenario.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection in cross-dataset setting.

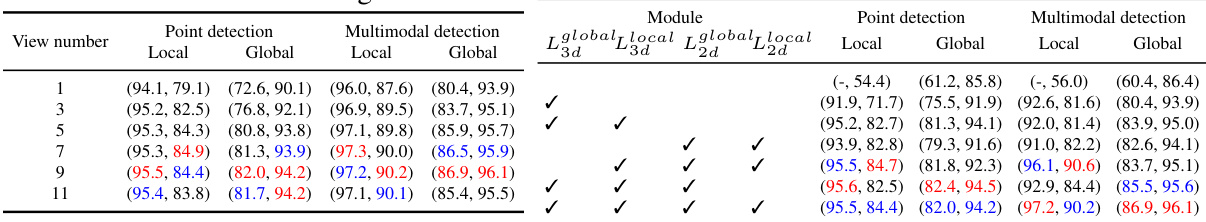

🔼 This table presents the ablation study of the proposed modules in PointAD. It shows the performance improvement with the addition of each module: 3D global branch, 3D local branch, 2D global branch, and 2D local branch. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of each module in capturing different aspects of anomaly semantics (global and local) and integrating point and pixel information for improved zero-shot 3D anomaly detection.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation on the proposed modules.

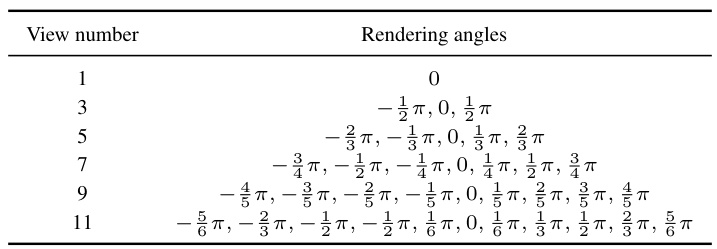

🔼 This table shows the ablation study on the number of rendering views used in PointAD. It lists the number of views (1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11) and the corresponding rendering angles used for each view number. The results of the ablation study show that increasing the number of views improves detection performance up to a certain point, but adding too many views introduces redundant information, leading to a decrease in performance. The optimal number of views was found to be 9.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation study on the number of rendering views.

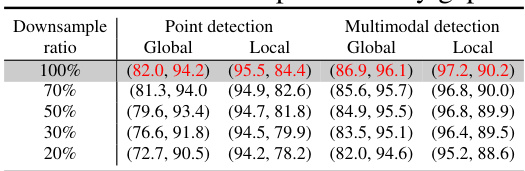

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the rendering quality of PointAD. The experimenters simulated varying rendering quality by applying a Gaussian blur with different sigmas (0, 1, 5, 9) to the 2D renderings. The table shows the performance of PointAD in terms of I-AUROC and AP for global and local anomaly detection. It highlights how the detection performance of PointAD diminishes as rendering quality decreases (increasing sigma), but still outperforms baselines even with heavily blurred renderings.

read the caption

Table 8: Analysis on the rendering quality. The original setting is highlighted in gray.

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of rendering quality on the performance of PointAD. Different levels of Gaussian blur were applied to the 2D renderings to simulate varying rendering quality. The table shows that PointAD’s performance decreases slightly as the rendering quality decreases (increasing blur), but it still outperforms baselines even with heavily blurred renderings.

read the caption

Table 8: Analysis on the rendering quality. The original setting is highlighted in gray.

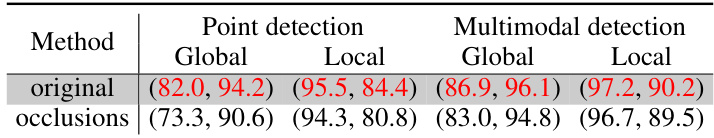

🔼 This table shows the impact of point cloud occlusions on the performance of PointAD. The ‘original’ row shows the performance of the model on the complete point clouds, while the ‘occlusions’ row shows the performance when some points are occluded, simulating real-world scenarios where parts of an object might be hidden. The results are reported as metric pairs (Global, Local) for both point detection and multimodal detection. The metrics are expressed as percentage values. Lower values after occlusions indicate that performance is degraded when some points are missing from the point cloud.

read the caption

Table 12: Analysis on the point occlusions.

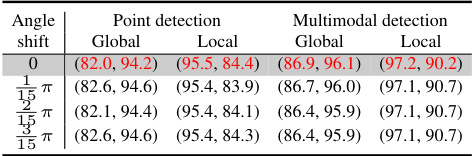

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the impact of varying rendering angles on the performance of PointAD. It shows the results (I-AUROC and AP for global and local anomaly detection, respectively) obtained by PointAD under various angle shifts while maintaining a constant angle discrepancy. The purpose is to assess PointAD’s robustness to variations in rendering angles that deviate from those used during training.

read the caption

Table 10: Analysis on the rendering angle.

🔼 This table shows the performance of PointAD under different lighting conditions. The original lighting condition is compared to stronger and weaker lighting conditions, denoted by ‘++’, ‘+’, ‘-’, and ‘–’, respectively. The results show PointAD’s robustness to variations in rendering lighting.

read the caption

Table 11: Analysis on the rendering lighting.

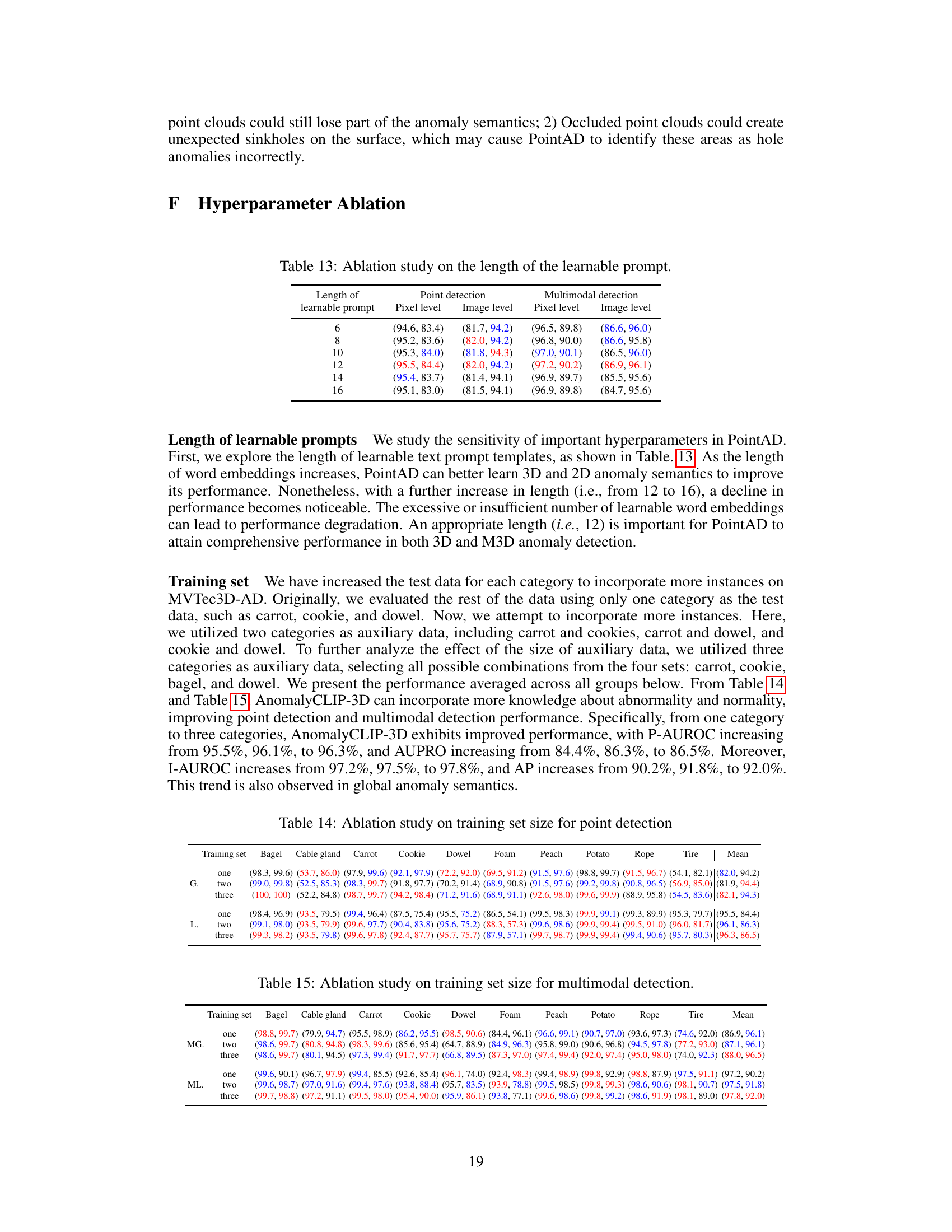

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the length of learnable prompts in PointAD. It shows the performance (Pixel level and Image level) for both point detection and multimodal detection at different prompt lengths (6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16). The results indicate an optimal length where performance peaks before declining with longer lengths, highlighting the sensitivity of the model to this hyperparameter.

read the caption

Table 13: Ablation study on the length of the learnable prompt.

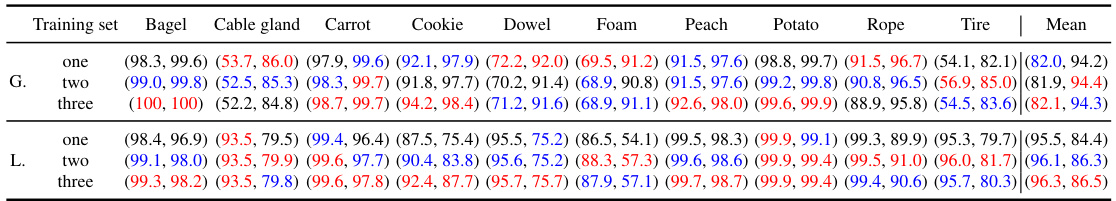

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the training set size for point detection. It shows the performance (I-AUROC and AP) of PointAD on different subsets of the MVTec3D-AD dataset, varying the number of categories used as auxiliary data for training. The results demonstrate how the model’s performance changes as more training data is included, and whether this improvement is consistent across different object categories.

read the caption

Table 14: Ablation study on training set size for point detection

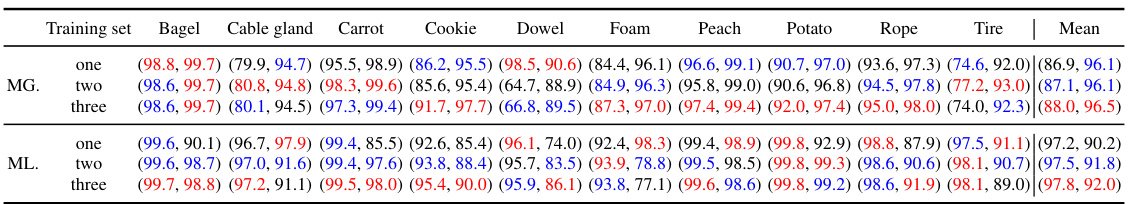

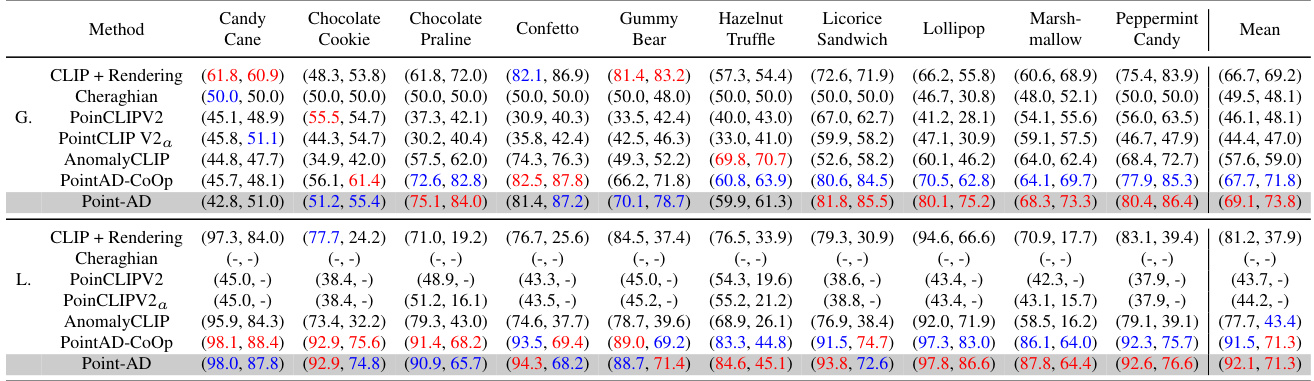

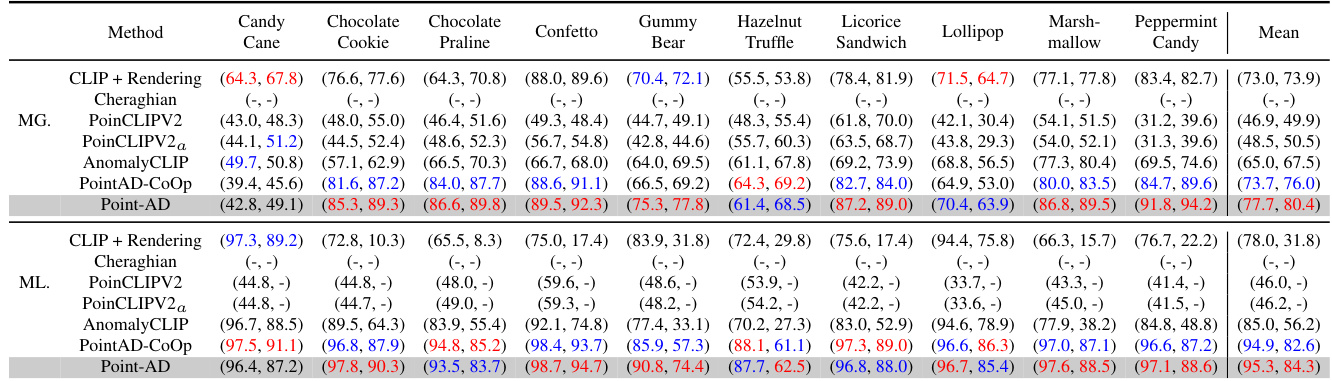

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods on zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. The methods are compared using two metrics: I-AUROC (image-level AUROC) and AP (average precision) for global anomaly detection, and P-AUROC (pixel-level AUROC) and AUPRO (average precision) for local anomaly detection. The table shows the performance for each of ten different object categories in the MVTec3D-AD dataset. PointAD consistently outperforms other methods across all metrics and categories.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effect of rendering quality on the performance of the PointAD model. The rendering quality was manipulated by applying a Gaussian blur filter with varying sigma values (0, 1, 5, and 9) to the 2D renderings. The table shows the performance (I-AUROC and AP) of both point detection and multimodal detection for different levels of blur. The original setting (no blur) is highlighted in gray. The results indicate how well the model is able to generalize across different rendering qualities.

read the caption

Table 8: Analysis on the rendering quality. The original setting is highlighted in gray.

🔼 This table compares the computation time, frames per second (FPS), GPU memory usage, and the performance metrics (I-AUROC, AP, P-AUROC, AUPRO) of PointAD with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for both unsupervised and zero-shot 3D anomaly detection on the MVTec3D-AD dataset. The results highlight PointAD’s efficiency and performance gains compared to existing approaches.

read the caption

Table 17: Comparison of computation overhead with SOTA approaches on MVTec3D-AD. The unsupervised method is abbreviated as Un.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of several zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection methods on the MVTec3D-AD dataset. The methods compared include CLIP + Rendering, Cheraghian, PointCLIP V2, PointCLIP V2a, AnomalyCLIP, PointAD-CoOp, and PointAD. The performance is evaluated using two metrics: I-AUROC and AP for global detection, and P-AUROC and AUPRO for local anomaly detection. The table highlights the superior performance of PointAD across all metrics.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods on zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection. The methods compared include CLIP+Rendering, Cheraghian, PointCLIP V2, PointCLIP V2a, AnomalyCLIP, PointAD-CoOp, and PointAD. The performance is evaluated using two metrics: I-AUROC (Image-level AUROC) and AP (average precision) for global anomaly detection, and P-AUROC (Pixel-level AUROC) and AUPRO (average precision) for local anomaly detection. Results are shown for ten different object categories in the MVTec3D-AD dataset.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of several methods on zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. The methods compared include CLIP + Rendering, Cheraghian, PointCLIP V2, PointCLIP V2α, AnomalyCLIP, PointAD-CoOp, and PointAD. Performance is measured using two metrics: I-AUROC and AP, which represent the global and local anomaly detection capabilities respectively. The results are presented for ten different object categories from the MVTec3D-AD dataset. The best and second-best performing methods for each metric are highlighted in red and blue, respectively.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods on zero-shot 3D anomaly detection. The methods are compared across multiple metrics (I-AUROC and AP for global detection, P-AUROC and AUPRO for local detection) and across ten different object categories from the MVTec3D-AD dataset. The best and second-best performing methods for each metric are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. Global and local anomaly detection results are shown separately. The table allows for a direct comparison of PointAD’s performance against other state-of-the-art and baseline methods in a zero-shot setting.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

🔼 This table compares the computation overhead (inference time, frames per second, GPU memory usage) of PointAD with state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches for 3D anomaly detection on the MVTec3D-AD dataset. It includes both unsupervised and zero-shot methods, highlighting PointAD’s efficiency and performance.

read the caption

Table 17: Comparison of computation overhead with SOTA approaches on MVTec3D-AD. The unsupervised method is abbreviated as Un.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods on zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection. The methods are compared using two metrics: I-AUROC (Image-level Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) and AP (Average Precision), both for global and local anomaly detection. The best and second-best results for each method are highlighted in red and blue. The table shows the performance across different object categories.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods on zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection. The metrics used are I-AUROC (Image-level Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) and AP (Average Precision) for global anomaly detection, and P-AUROC (Pixel-level AUROC) and AUPRO (Average Precision Under the Recall-Precision Curve) for local anomaly detection. The best and second-best results for each dataset and metric are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. The methods compared include CLIP+Rendering, Cheraghian, PointCLIP V2, PointCLIP V2α, AnomalyCLIP, PointAD-CoOp, and PointAD.

read the caption

Table 18: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection. The best and second-best results in ZS are highlighted in red and blue. G. and L. represent the global and local anomaly detection.

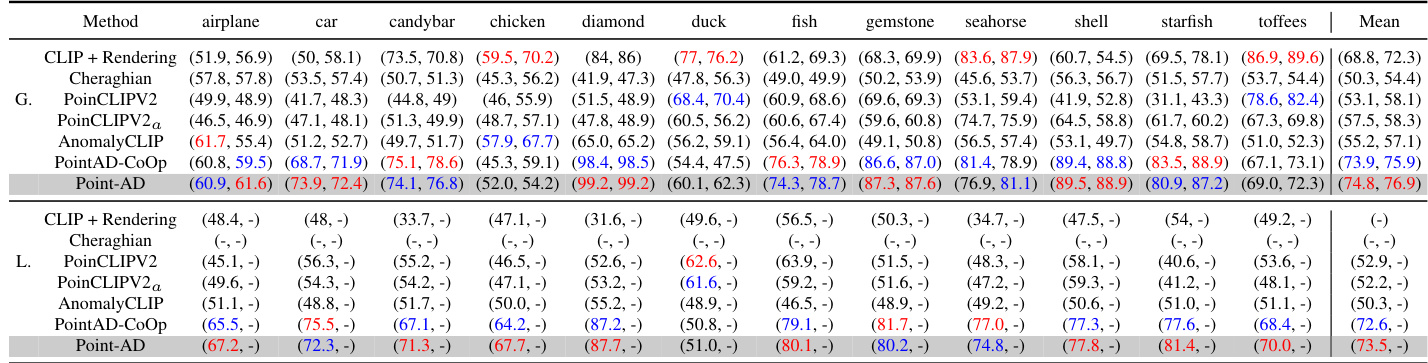

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of zero-shot (ZS) 3D anomaly detection methods on the Real3D-AD dataset. The methods compared include several baselines (CLIP + Rendering, Cheraghian, PoinCLIP V2, PoinCLIP V2a, AnomalyCLIP) and the proposed PointAD and PointAD-CoOp methods. Performance is measured by the Intersection over Union (IoU) for both global and local anomaly detection. The table shows PointAD consistently outperforms the baselines across all categories in the Real3D-AD dataset.

read the caption

Table 22: Performance comparison on ZS 3D anomaly detection on Real3D-AD.

Full paper#