TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are revolutionizing AI, but their massive computational demands pose significant limitations. Existing efficiency improvements like linear attention mostly focus on optimizing self-attention, neglecting the equally computationally expensive fully-connected layers. This limits the potential scaling of LLMs and increases their overall energy consumption.

MemoryFormer tackles this issue head-on. It introduces a novel memory layer that replaces fully-connected layers with a memory-efficient hashing-based approach. Instead of computationally expensive matrix multiplications, the model retrieves relevant vectors from pre-computed lookup tables, dramatically reducing FLOPs. Extensive experiments demonstrate MemoryFormer achieves comparable performance to traditional transformers with significantly lower computational requirements, showing its potential for building more efficient and scalable LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel approach to reduce the computational cost of large language models (LLMs), a critical challenge in the field. By significantly reducing FLOPs without sacrificing performance, it opens up new avenues for research into more efficient and scalable LLMs, impacting various applications. It also suggests potential hardware design improvements that can further accelerate LLM inference.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure shows the comparison of computational complexity (FLOPs) between the proposed MemoryFormer and a baseline Transformer model. The x-axis represents the model’s hidden size, while the y-axis represents the FLOPs per block (in billions). Two lines are plotted for each model (Transformer and MemoryFormer), one for a sequence length of 1024 and another for a sequence length of 2048. The results clearly demonstrate that MemoryFormer achieves significantly lower FLOPs compared to the Transformer model, especially as the hidden size and sequence length increase. This reduction in FLOPs is a key advantage of MemoryFormer, indicating its enhanced computational efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: FLOPs with different model hidden size and sequence lengths.

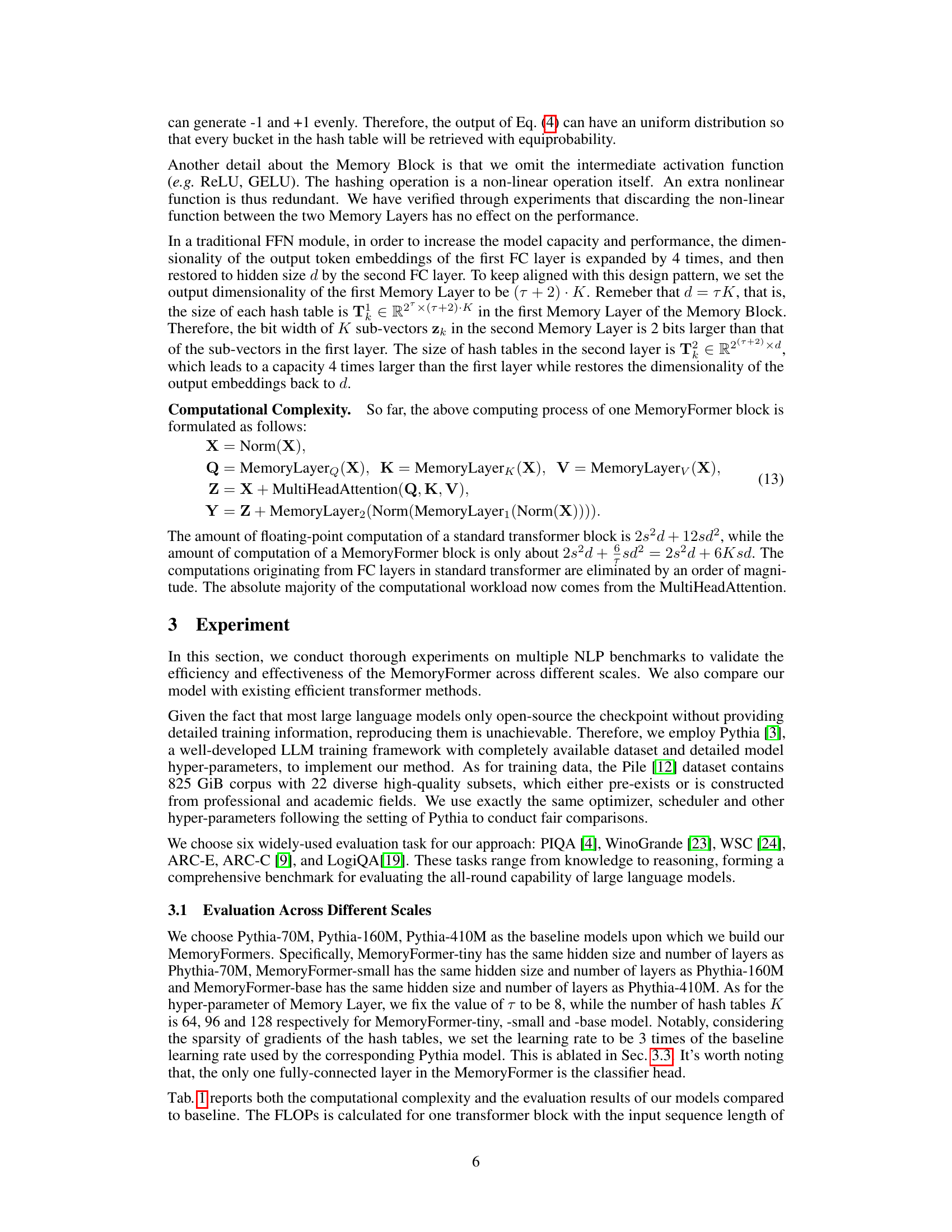

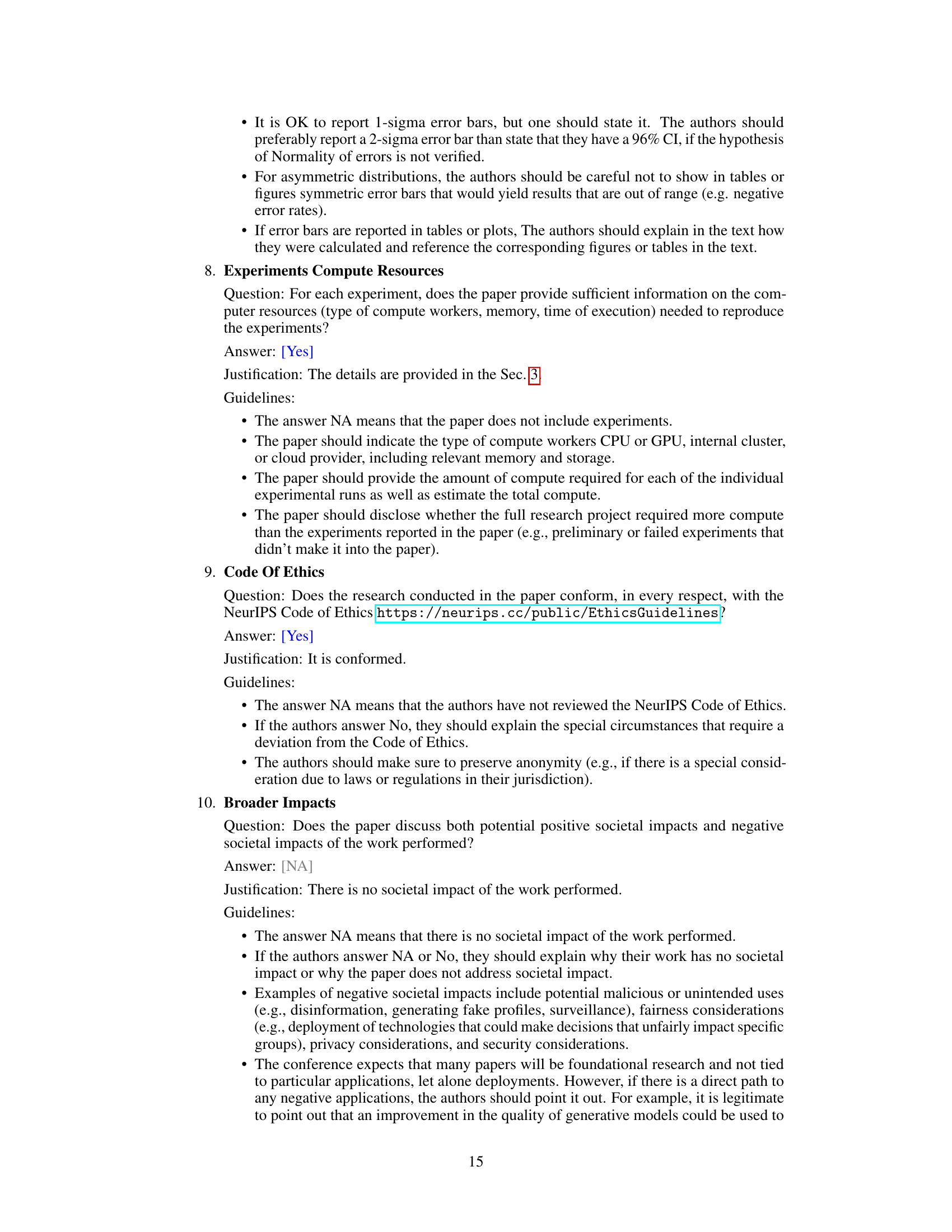

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot evaluation results of various models on six public NLP benchmarks. The models compared include Pythia models of different sizes (70M, 160M, 410M parameters) and their corresponding MemoryFormer variants. The table shows the number of layers, hidden size, FLOPs (with and without attention), and the average accuracy across the six benchmarks (PIQA, WinoGrande, WSC, ARC-E, ARC-C, LogiQA). Inference FLOPs are calculated for a single transformer block with a sequence length of 2048, to allow for comparison of computational efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Zero-shot evaluation results on public NLP benchmarks. We use 'MF' as the abbreviation for MemoryFormer. 'Attn.' refers to the computation of o(QKT)V. Inference FLOPs are measured for one block with sequence length of 2048.

In-depth insights#

MemoryFormer Intro#

The hypothetical ‘MemoryFormer Intro’ section would likely introduce the core concept of MemoryFormer, a novel transformer architecture designed to minimize computational cost. It would highlight the limitations of existing large language models (LLMs) regarding their massive computational demands and the existing optimization strategies, like linear attention, that haven’t sufficiently addressed the scaling problem. The introduction would then emphasize MemoryFormer’s unique approach of significantly reducing FLOPs by eliminating most computations except the crucial multi-head attention operations. This would be achieved through a proposed alternative to fully-connected layers, likely involving in-memory lookup tables and a hashing mechanism for efficient feature transformations. The introduction would emphasize the potential of MemoryFormer for improving LLM accessibility and deployment by reducing resource consumption, potentially touching upon its compatibility with existing hardware or suggesting directions for future hardware design.

LSH-based Hashing#

Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) is a crucial technique for efficiently searching large datasets by mapping similar items into the same hash buckets. Its effectiveness hinges on the careful design of the hash functions, which need to balance the probability of collision between similar items (high) and dissimilar items (low). LSH’s power lies in its ability to reduce the computational cost of approximate nearest neighbor search from O(n) to sub-linear complexity, making it suitable for high-dimensional data and large-scale applications. However, the performance of LSH heavily depends on parameter tuning, particularly the number of hash tables and the dimension reduction technique used. A poorly tuned LSH scheme can significantly degrade performance, potentially losing the benefits of dimensionality reduction and requiring more computational resources than a brute-force search. Choosing appropriate hash functions and optimizing parameters are therefore vital for effective LSH-based hashing. Furthermore, understanding the trade-offs between accuracy and speed is crucial when selecting and implementing this technique for specific applications.

Memory Layer Design#

The Memory Layer, a core component of the proposed MemoryFormer architecture, is designed to efficiently approximate the functionality of fully-connected layers in traditional Transformers. Its key innovation lies in replacing computationally expensive matrix multiplications with memory lookups. This is achieved by employing Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) to map input embeddings to pre-computed vectors stored in hash tables. The selection of these vectors, retrieved dynamically based on the input, is crucial. The use of LSH ensures that similar inputs map to similar vectors, mimicking the behavior of continuous linear projections. Furthermore, a probability-weighted aggregation of the retrieved vectors generates the final output, enabling backpropagation and end-to-end training. This design significantly reduces the computational complexity while aiming to preserve the representational power of fully-connected layers. However, challenges remain in managing hash table size and collisions, as well as in addressing the potential impact of hash function design on overall model performance.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section in a research paper is crucial for evaluating the proposed method’s performance. It should present results across multiple established benchmarks, comparing the new method against existing state-of-the-art approaches. Quantitative metrics, such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and efficiency measures (like FLOPs or inference time), are essential. The presentation must be clear, including tables and graphs, along with statistical significance testing to ensure the observed improvements are not due to chance. Analysis of results should go beyond simple comparisons, explaining trends, and exploring strengths and weaknesses relative to different benchmarks or data characteristics. Limitations should be acknowledged where the method underperforms and potential reasons for this explored. The choice of benchmarks themselves is important. They should be relevant to the problem domain and widely accepted within the research community. Ultimately, a strong ‘Benchmark Results’ section provides compelling evidence of the proposed method’s practical value and contribution to the field.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from the MemoryFormer paper could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency of the hashing mechanism is crucial; while the current method reduces computational complexity, further optimization could yield even greater speedups, perhaps through more sophisticated hashing algorithms or hardware acceleration. Another key area is expanding the applicability of MemoryFormer to various model sizes and tasks. The current experiments demonstrate effectiveness on specific benchmarks, but broader testing is needed to establish its generalizability across diverse NLP applications. Furthermore, investigating the interplay between MemoryFormer and different self-attention mechanisms is warranted. Combining MemoryFormer with advanced attention techniques could lead to even more efficient and powerful transformer architectures. Finally, exploring the theoretical foundations of MemoryFormer and its relationship to other low-rank approximation techniques would provide valuable insights. A deeper theoretical understanding could guide the development of future, even more efficient memory-based transformer models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

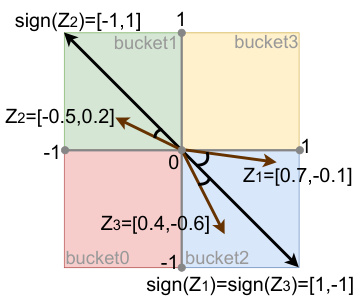

🔼 This figure demonstrates the Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) process used in MemoryFormer. It shows how three sub-vectors (z1, z2, z3) are hashed into different buckets of hash tables (T1, T2, T3). Each bucket stores a representative vector, and similar sub-vectors are mapped to the same bucket. This illustration helps visualize how the LSH approach enables efficient retrieval of similar vectors with a reduced computational cost compared to traditional fully-connected layers.

read the caption

Figure 2: A demonstration with T = 2 and K = 3, where z₁ is hashed to the bucket2 of T₁, z₂ is hashed to the bucket1 of T₂, z₃ is hashed to the bucket2 of T₃.

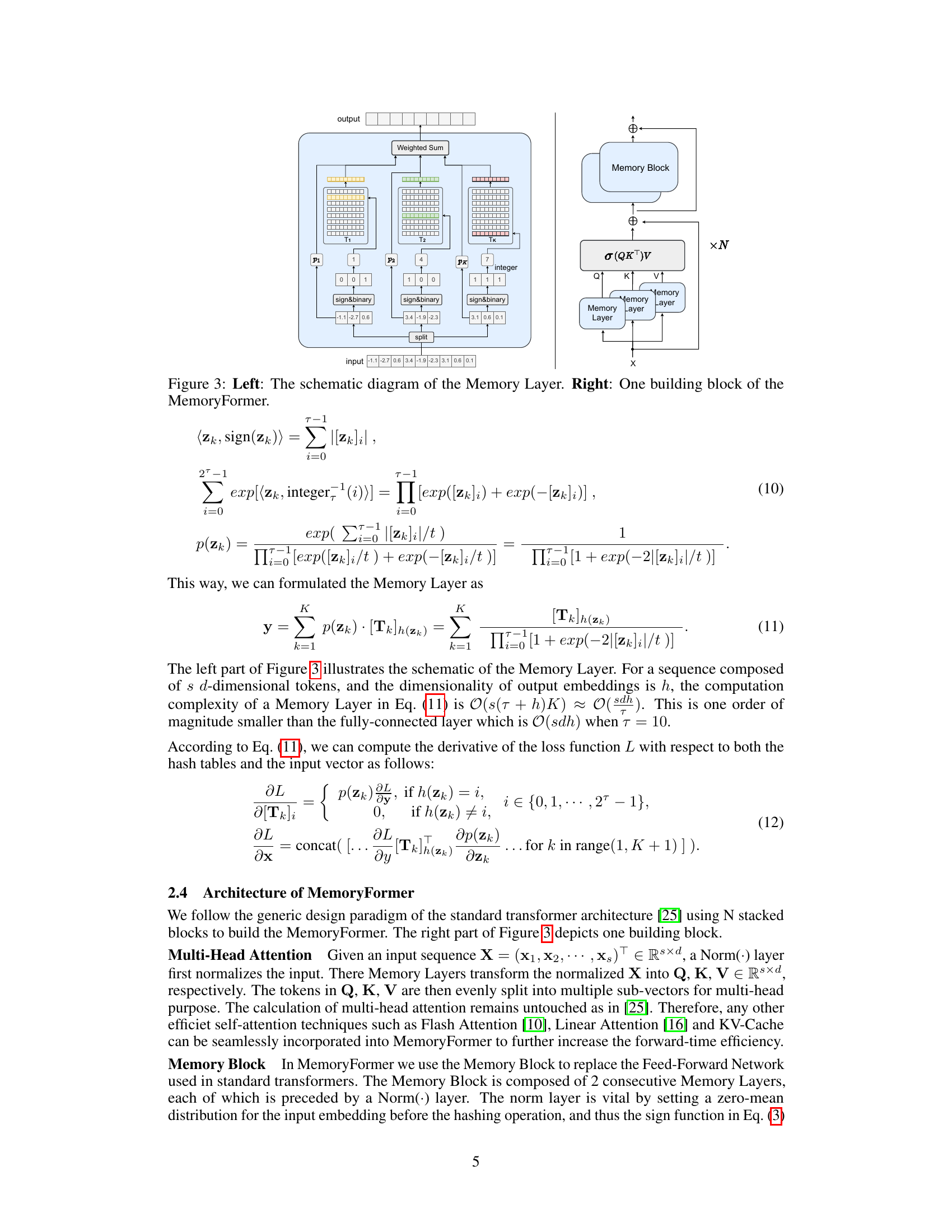

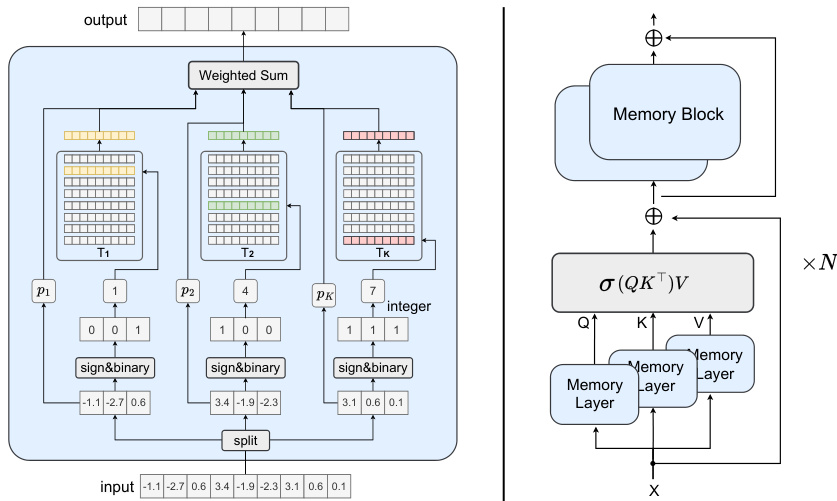

🔼 The figure shows two diagrams. The left diagram shows the internal structure of the Memory Layer, which is a core component of the MemoryFormer model. It illustrates the process of hashing input vectors, retrieving a subset of vectors from memory tables (T1 to Tk), and then computing a weighted sum of the retrieved vectors to generate the output. The right diagram depicts a single building block of the MemoryFormer architecture, illustrating how the Memory Layer is integrated with the multi-head attention mechanism. The building block takes an input (X), processes it through Memory Layers to obtain query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices, performs a multi-head attention operation, and finally outputs a transformed representation (Y).

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: The schematic diagram of the Memory Layer. Right: One building block of the MemoryFormer.

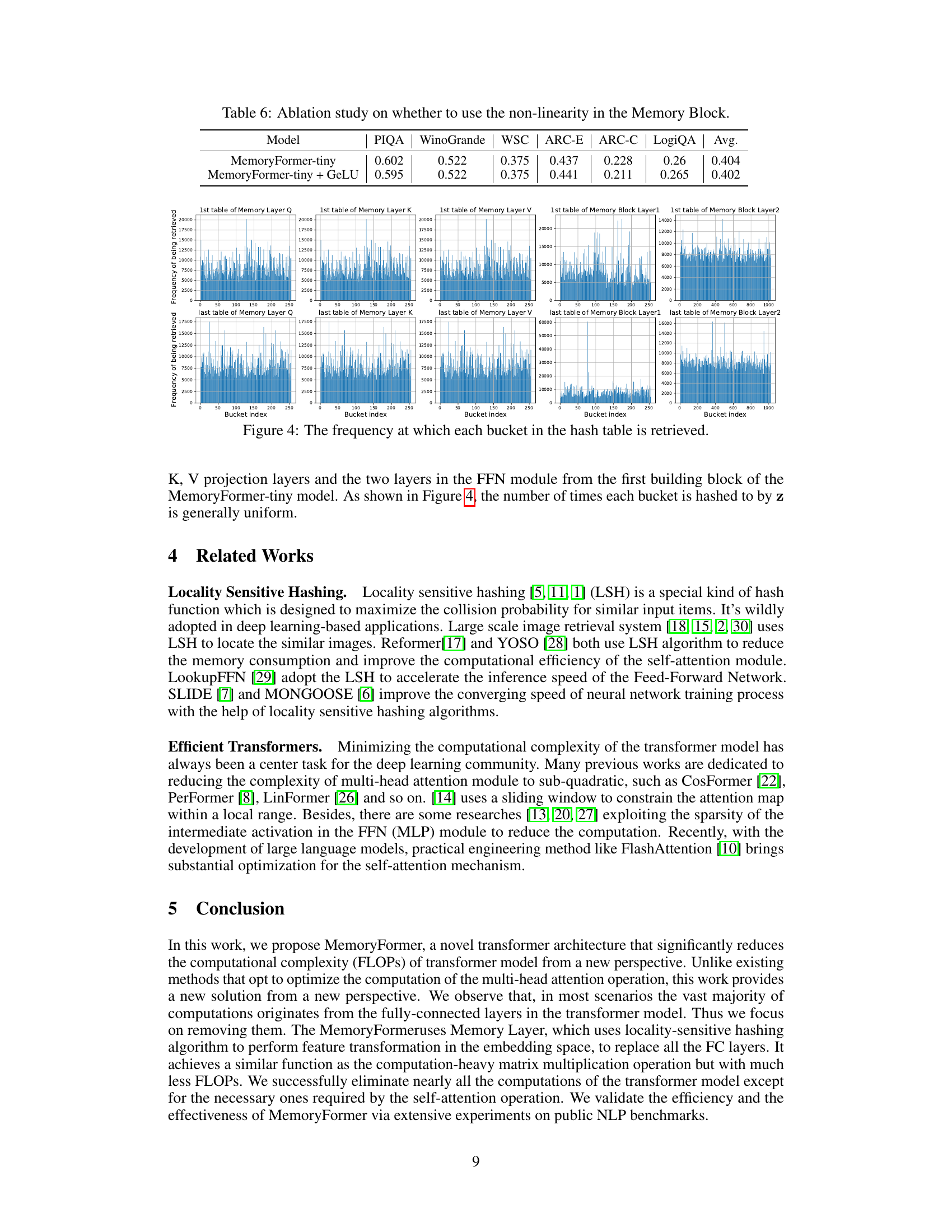

🔼 This figure visualizes the distribution of hash bucket retrievals in the Memory Layer. It shows the frequency with which each bucket in the hash tables (for Q, K, V projections and the two layers of the FFN module) is accessed. A uniform distribution across buckets indicates that the hashing function is working effectively and the embedding space is well-utilized. Deviations from uniformity might suggest issues with the hash function or data imbalance.

read the caption

Figure 4: The frequency at which each bucket in the hash table is retrieved.

More on tables

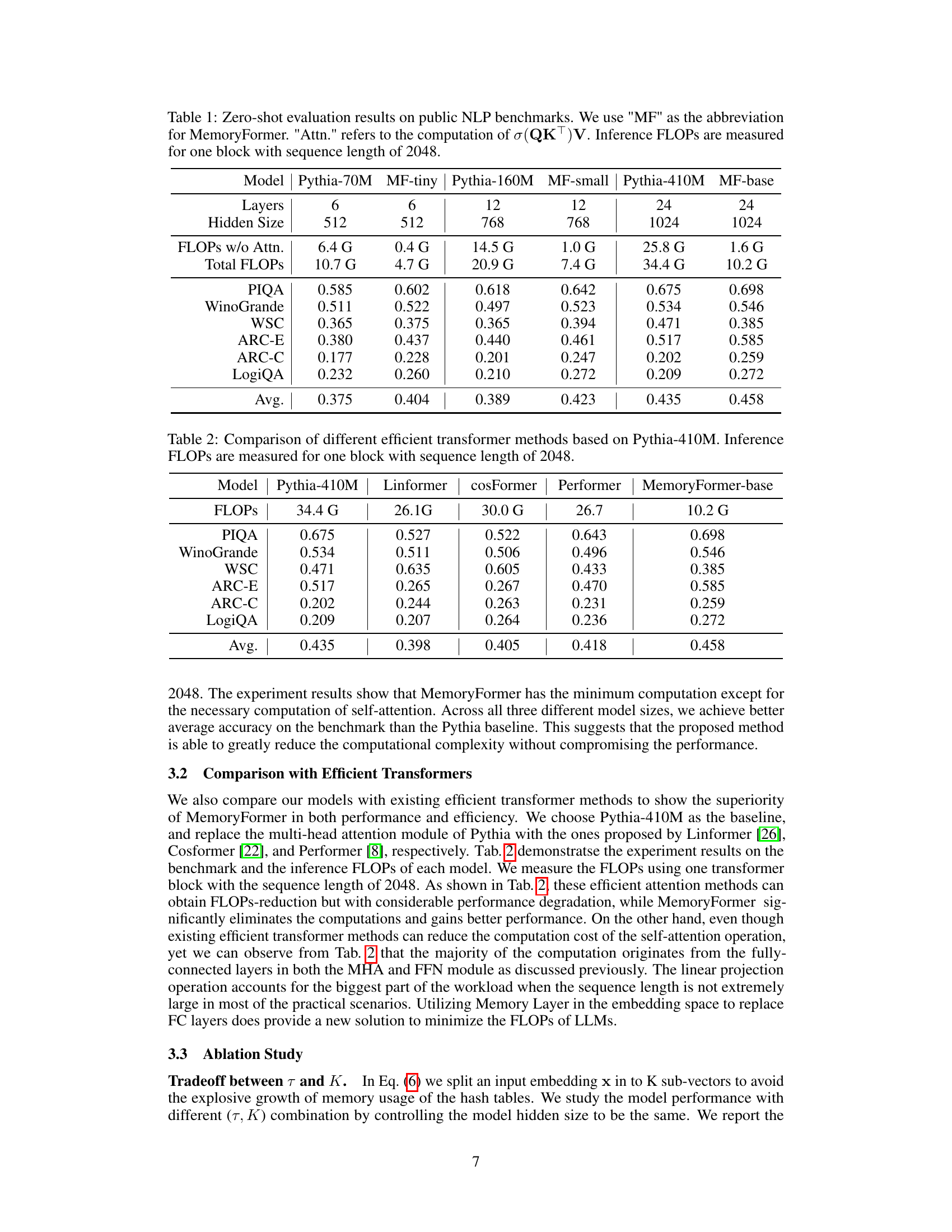

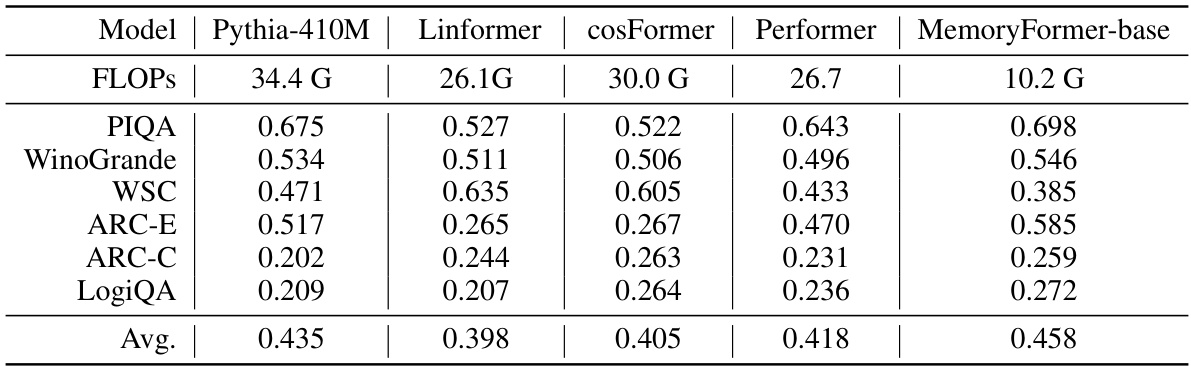

🔼 This table compares the performance and computational efficiency (in FLOPs) of different efficient transformer models against a baseline Pythia-410M model. The comparison includes Linformer, Cosformer, Performer, and MemoryFormer-base, all using a sequence length of 2048 for inference FLOPs calculation. The performance is evaluated across six NLP benchmarks: PIQA, WinoGrande, WSC, ARC-E, ARC-C, and LogiQA. The average performance across these benchmarks is also provided for each model.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of different efficient transformer methods based on Pythia-410M. Inference FLOPs are measured for one block with sequence length of 2048.

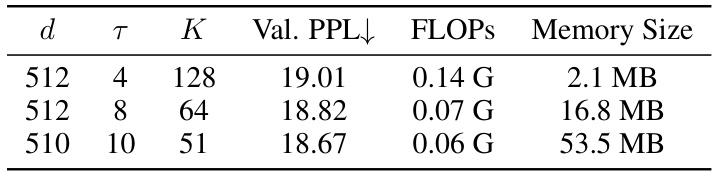

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the hyperparameters τ (number of bits) and K (number of hash tables) in the Memory Layer of the MemoryFormer model. It shows the validation perplexity (Val. PPL), floating-point operations (FLOPs), and memory size required for different combinations of τ and K. The results demonstrate the trade-off between model performance, computational cost, and memory usage when adjusting these hyperparameters.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study on different τ and K. Memory Size refer to the storage space required by the Memory Layer Q.

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effect of different learning rates (LR) on the validation perplexity (Val. PPL) of the MemoryFormer model. The experiment was run for 8000 training steps, and the learning rates tested were 1e-3, 2e-3, 3e-3, and 4e-3. The table shows that a learning rate of 3e-3 achieved the lowest validation perplexity.

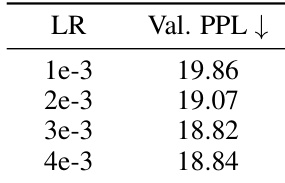

read the caption

Table 4: Val. PPL at 8000 training steps with various LR.

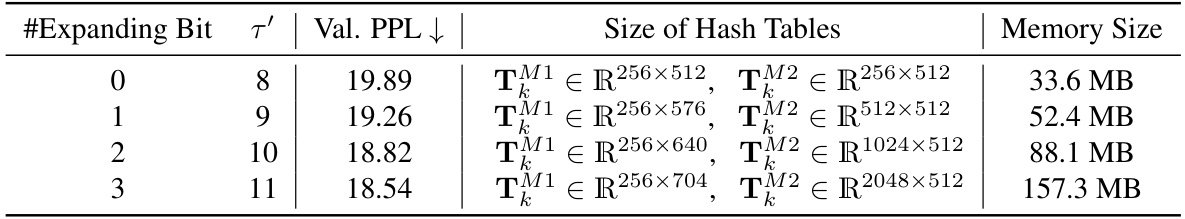

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the expanding bits in the Memory Block of the MemoryFormer model. It shows the validation perplexity (Val. PPL), the size of the hash tables (TM1 and TM2), and the total memory size used by the Memory Block for different numbers of expanding bits. The expanding bits refers to the additional bits added to the sub-vector zk during the expansion process in the second Memory Layer. As the number of expanding bits increases, the model performance improves, but the memory consumption increases exponentially.

read the caption

Table 5: Different expanding bits of Memory Block. #Expanding Bit = T' denotes the number of extra bit of zk after expansion. Memory Size denotes the storage space required by Memory Block.

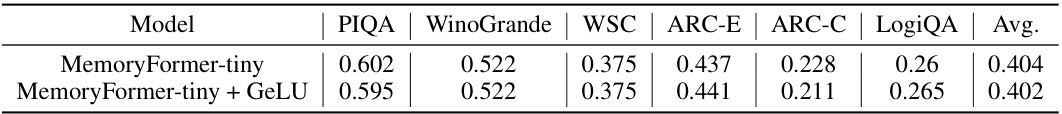

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of removing the GeLU activation function from the Memory Block in the MemoryFormer model. The table compares the performance (average accuracy across several NLP benchmarks: PIQA, WinoGrande, WSC, ARC-E, ARC-C, LogiQA) of the MemoryFormer-tiny model with and without GeLU activation between the two Memory layers of the block. Results show minimal performance difference, suggesting that the GeLU function may be redundant due to the inherent nonlinearity of the hashing operation.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation study on whether to use the non-linearity in the Memory Block.

Full paper#