TL;DR#

Two-sided matching markets, prevalent in various applications like online advertising and job markets, present a unique challenge: participants need to learn preferences while striving for stable matchings. Existing bandit learning algorithms often struggle with high regret, particularly when the number of options (arms) significantly outnumbers the decision-makers (players). This is because existing algorithms treat arms equally and thus require heavy exploration regardless of its potential to lead to stable matching.

This research tackles this issue by proposing a new algorithm, AOGS. AOGS integrates the players’ learning process within the Gale-Shapley algorithm steps, intelligently balancing exploration and exploitation to drastically minimize regret. By efficiently managing the exploration, AOGS achieves a significantly better upper bound for regret, removing the K dependence in the main order term. It also provides a refined analysis of the existing centralized UCB algorithm under specific conditions, demonstrating an improved regret bound. These contributions represent significant advancement in bandit learning for two-sided matching markets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves the state-of-the-art in bandit learning for two-sided matching markets. The improved algorithm reduces regret by removing the dependence on the number of arms in the main term, making it highly efficient for markets where the number of players is much smaller than the number of arms. This has significant implications for various real-world applications, including online advertising and job markets. The refined analysis of the existing centralized UCB algorithm further enhances our understanding of this problem and opens new avenues for algorithm design and theoretical analysis.

Visual Insights#

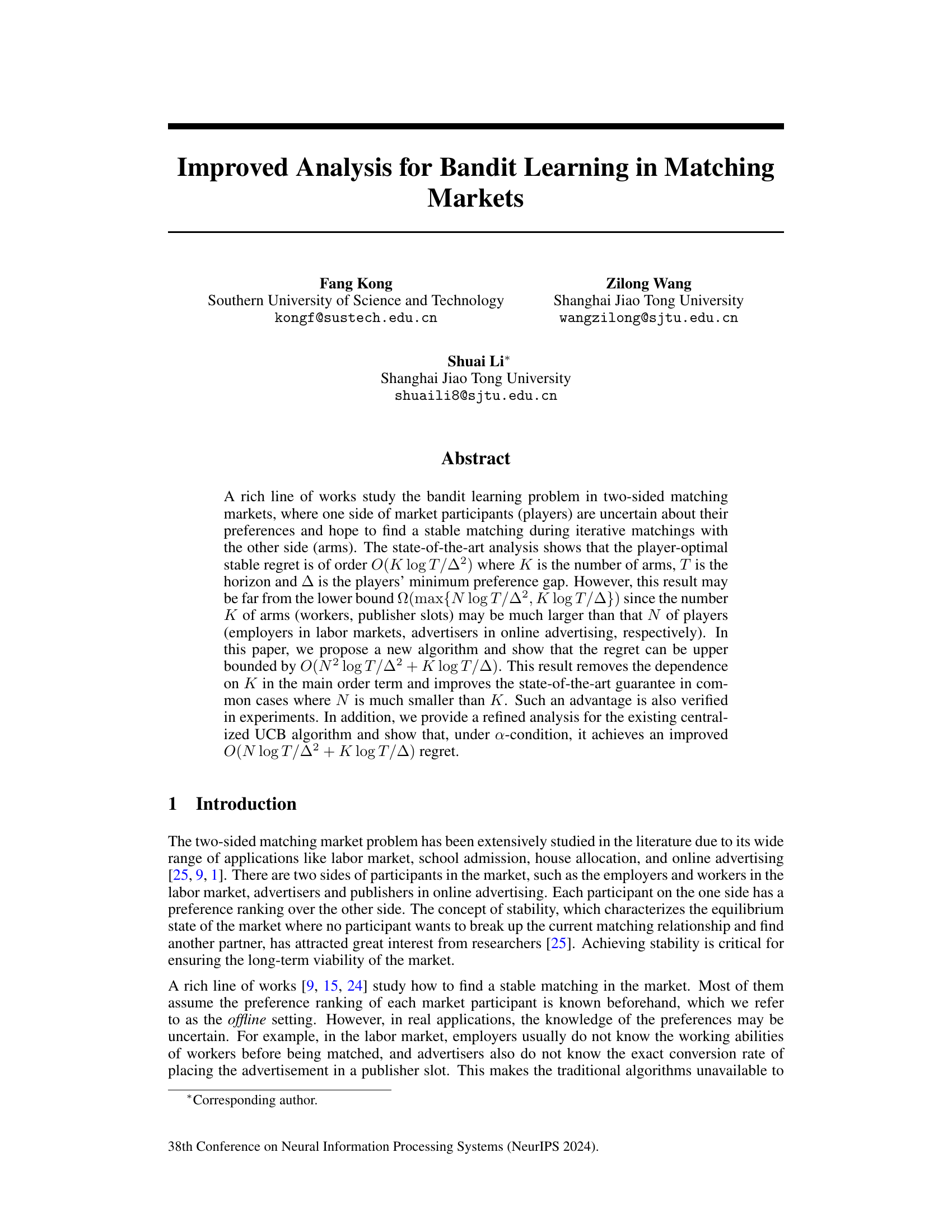

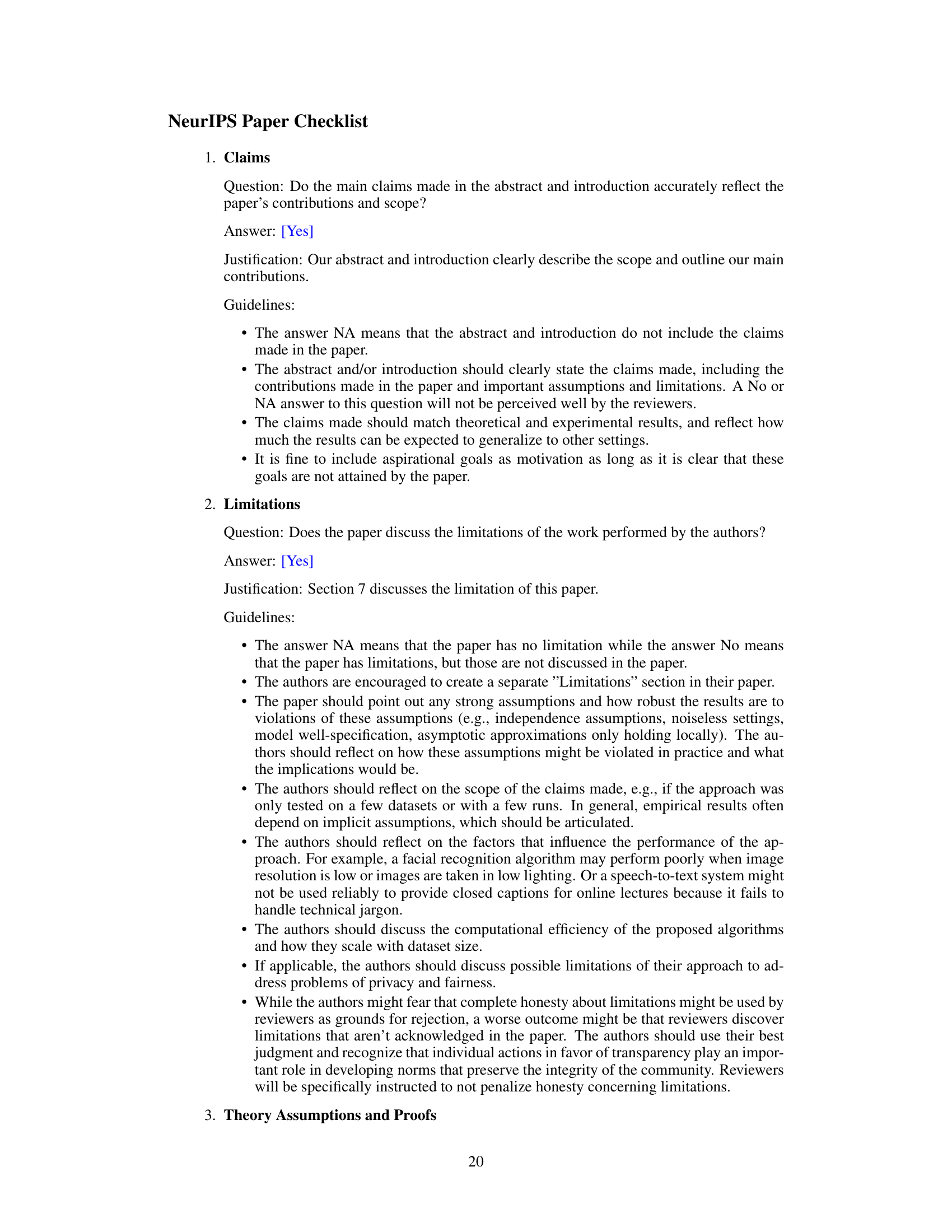

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing the performance of the proposed AOGS algorithm with three other algorithms (ETGS, ML-ETC, and PhasedETC) in decentralized one-to-one matching markets. The experiment settings involved 3 players and 10 arms, and the results are averaged over 50 independent runs. The figure consists of two sub-figures. Subfigure (a) plots the maximum cumulative player-optimal stable regret, showing how much reward each algorithm missed compared to the optimal stable matching. Subfigure (b) plots the maximum cumulative player-optimal unstability, representing how frequently each algorithm failed to reach the player-optimal stable matching. The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental comparisons of our AOGS with ETGS, ML-ETC and Phased ETC in one-to-one decentralized markets with N = 3 players and K = 10 arms.

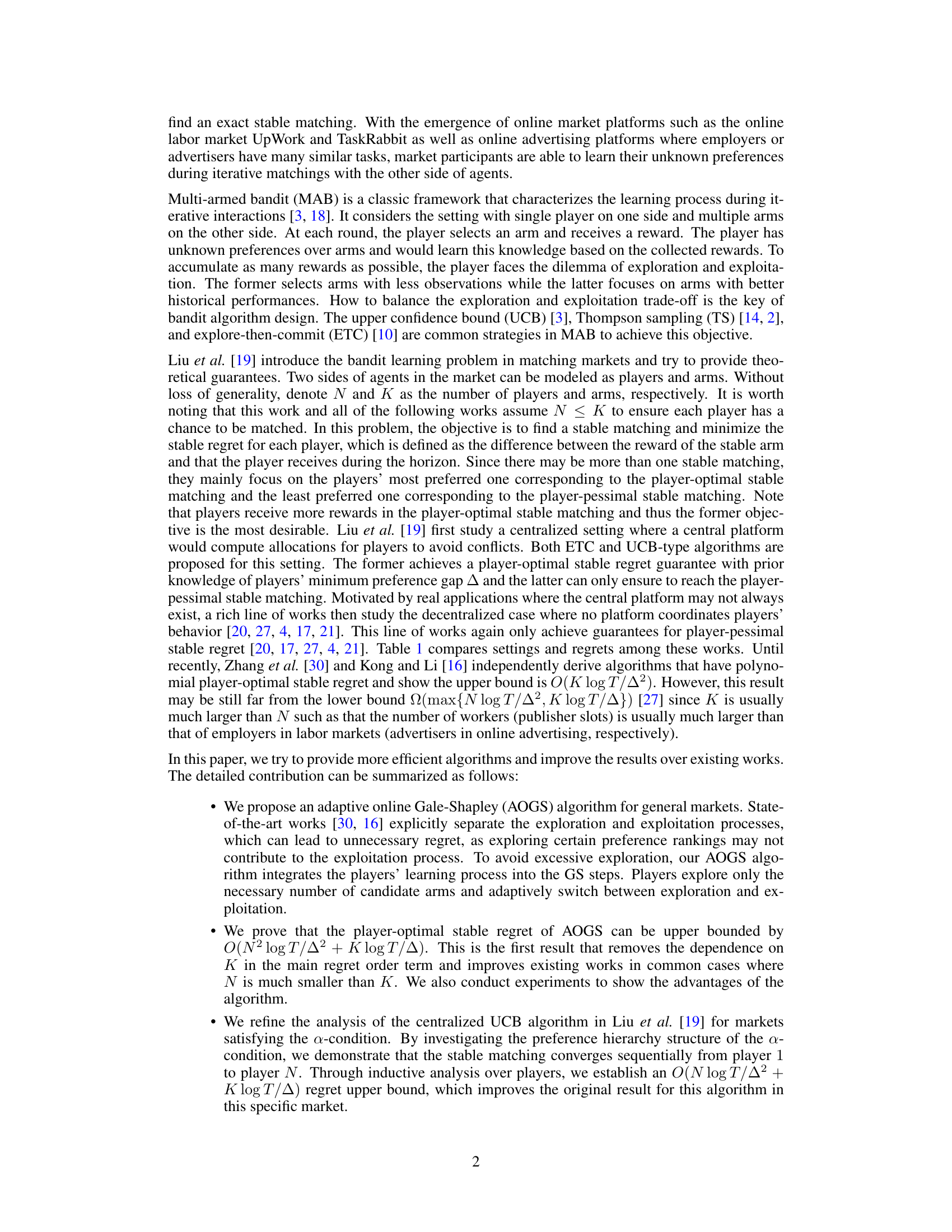

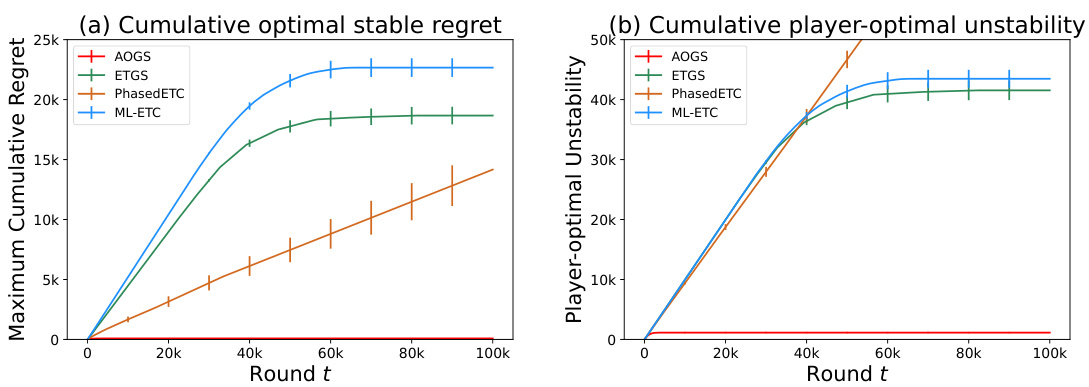

🔼 This table compares the proposed algorithm with existing works in terms of regret bounds and settings. It highlights the improvement achieved by the proposed algorithm, particularly in scenarios where the number of players is significantly smaller than the number of arms. Different metrics for the preference gap (Δ) are defined and compared.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparisons of settings and regret bounds with most related works, * represents the player-optimal stable regret and bounds without labeling * are for player-pessimal stable regret, # represents the centralized setting. N and K are the number of players and arms with N < K, T is the total horizon, Δ corresponds to some preference gap, ε depends on the hyper-parameter of algorithms, and C is related to the unique stable matching condition which can grow exponentially in N. The definition of Δ in different works requires particular care. We use gap₁, gap₂, gap₃, gap₄ represent the minimum preference gap between the (player-optimal) stable arm and the next arm after the stable arm in the preference ranking among all players, the minimum preference gap between any different arms among all players, the minimum preference gap between the first N + 1 ranked arms among all players, and the minimum preference gap between arms that are more preferred than the next of the player-optimal stable arm among all players, respectively. Based on the property that the player-optimal stable arm of each player must be its first N-ranked (shown in Appendix), there would be gap₁ ≥ gap₄ ≥ gap₃ ≥ gap₂. So our dependence on Δ is better than the state-of-the-art works [30, 16] for general markets.

Full paper#