TL;DR#

Discovering new materials is crucial for advancements in various fields, but the sheer size of the chemical space makes experimental exploration incredibly challenging. Existing methods, like autoregressive LLMs and denoising models, have shown promise, but each has limitations: LLMs struggle with continuous values, while denoising models are less adept at handling discrete elements. Additionally, generating materials with desirable properties (e.g., high bandgap and thermal stability) requires complex conditional generation, which is difficult to achieve with existing methods.

FlowLLM tackles these challenges head-on. It leverages the strengths of both LLMs and Riemannian flow matching (RFM) in a synergistic way. It fine-tunes an LLM to learn a base distribution of metastable crystals, which is then refined using RFM. The result is a significant improvement in the generation rate of stable materials, exceeding existing methods by over 300%. Furthermore, FlowLLM’s output materials are much closer to their relaxed states, substantially lowering the computational cost of subsequent analysis.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it presents FlowLLM, a novel approach to material generation that significantly outperforms existing methods. Its combination of LLMs and RFM offers a new avenue for materials discovery, potentially accelerating innovation across various industries. This work also highlights the power of hybrid models combining the strengths of different AI techniques for complex tasks, a trend likely to influence future research in numerous fields. Furthermore, FlowLLM’s ability to generate stable materials efficiently significantly reduces computational costs associated with material discovery.

Visual Insights#

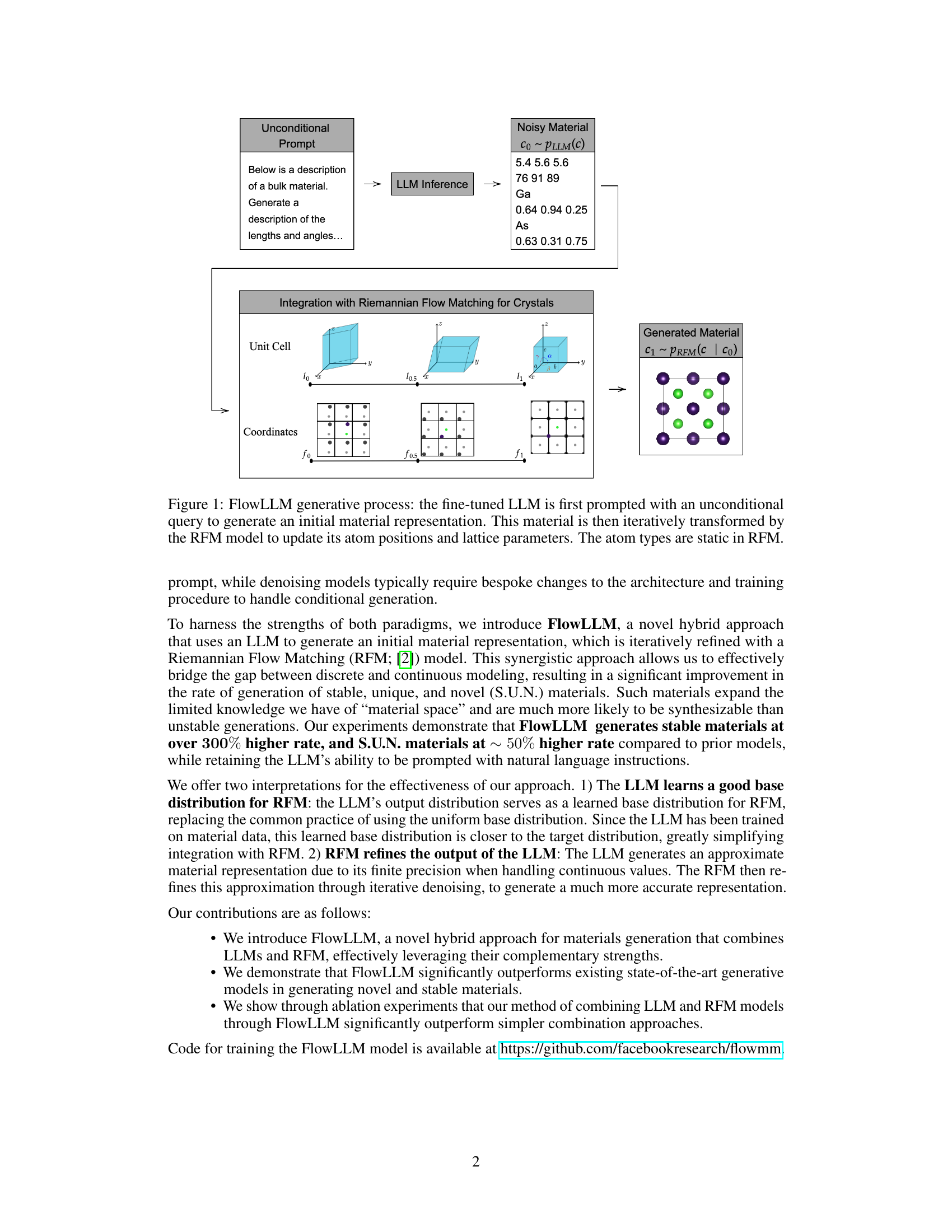

🔼 The figure illustrates the two-step process of FlowLLM. First, an unconditional prompt is given to a fine-tuned large language model (LLM) which generates a noisy initial material representation (text). This representation is then converted to a graph representation containing atom types, coordinates, and unit cell geometry. Then, a Riemannian Flow Matching (RFM) model iteratively refines this noisy material by updating atom positions and lattice parameters, finally producing a generated crystalline material structure. Atom types remain unchanged throughout the RFM refinement process.

read the caption

Figure 1: FlowLLM generative process: the fine-tuned LLM is first prompted with an unconditional query to generate an initial material representation. This material is then iteratively transformed by the RFM model to update its atom positions and lattice parameters. The atom types are static in RFM.

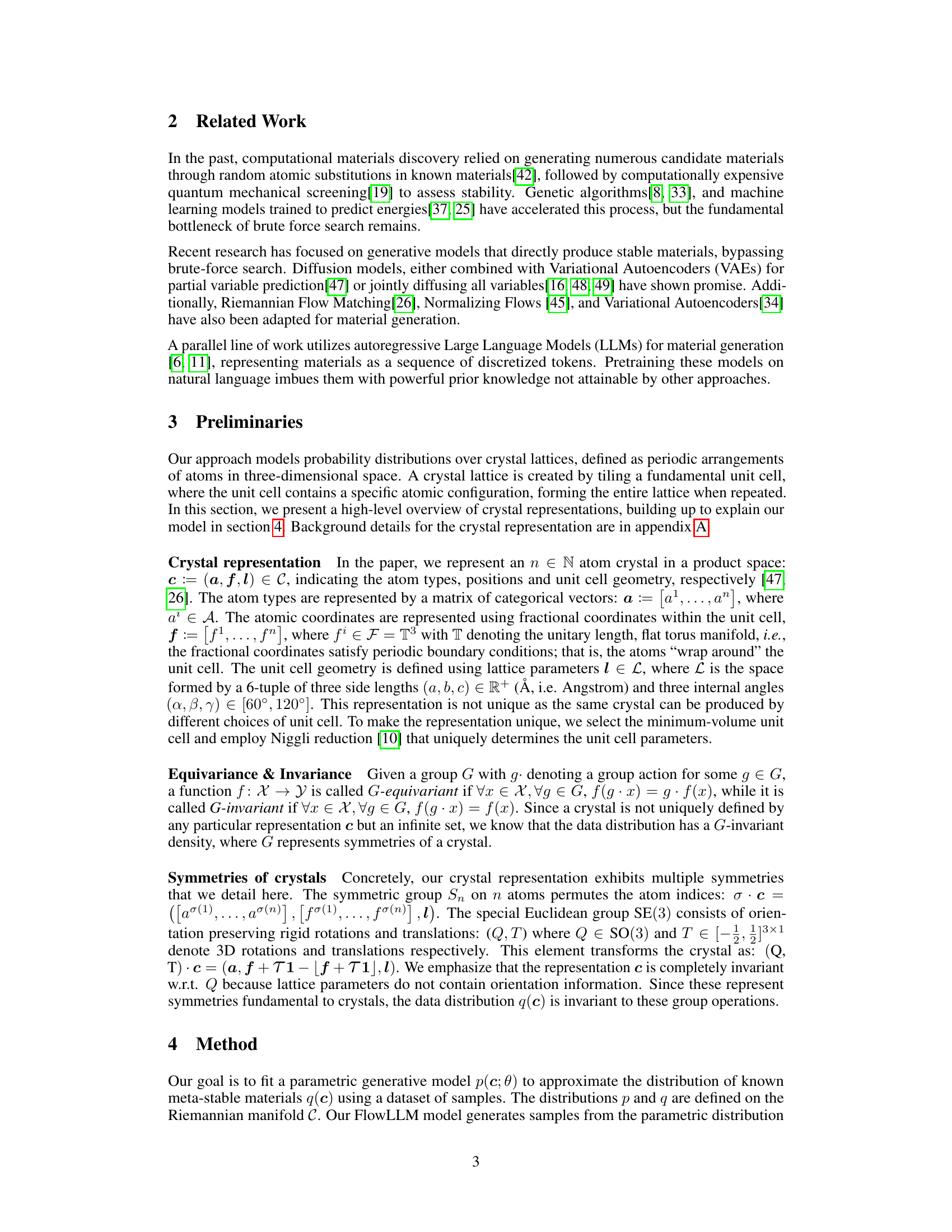

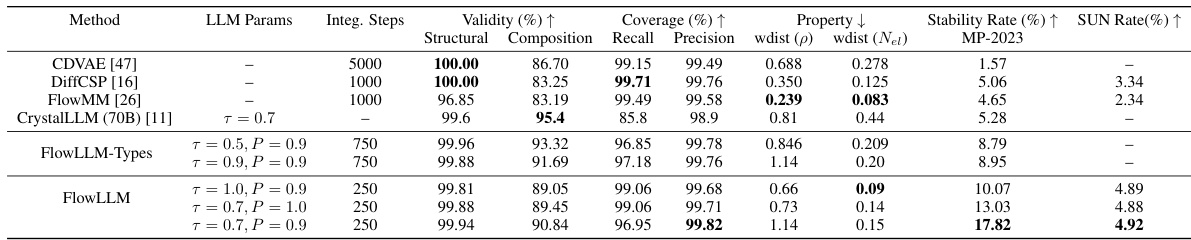

🔼 This table presents a comparison of FlowLLM’s performance against other state-of-the-art methods for material generation using the MP-20 dataset. It shows various metrics, including validity, coverage (recall and precision of structural compositions), Wasserstein distance (comparing generated and ground truth materials based on properties and number of unique elements), stability rate (percentage of generated materials that are thermodynamically stable), and SUN rate (percentage of stable, unique, and novel materials generated). The different rows represent different parameter settings or models, highlighting FlowLLM’s superior performance across various metrics, particularly stability and SUN rate.

read the caption

Table 1: Results for material generation on the MP-20 dataset. Stability rate is the percentage of generated materials with Ehull < 0.0 & N-ary ≥ 2.

In-depth insights#

LLM-RFM Synergy#

The core idea of “LLM-RFM Synergy” is a powerful combination of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Riemannian Flow Matching (RFM) for material generation. LLMs excel at generating discrete atomic species and initial crystal structures, offering versatility via natural language prompting. However, LLMs struggle with the continuous nature of atomic positions and lattice parameters. RFM, on the other hand, effectively refines continuous values, improving the stability and accuracy of the generated crystal structures. By first using the LLM to produce an initial material representation, and then refining it using RFM, this approach bridges the gap between discrete and continuous modeling. This synergistic approach is superior to using either model alone, generating more stable and novel materials with significantly reduced post-hoc computational costs. The learned base distribution from the LLM also enhances RFM’s efficiency and improves results by guiding the RFM process towards more realistic and physically meaningful structures.

Stable Material Rate#

The concept of “Stable Material Rate” in materials science research is crucial for assessing the efficacy of generative models in producing synthesizable materials. A high stable material rate signifies that a substantial fraction of the generated materials are thermodynamically stable, meaning they are likely to exist in reality and not merely theoretical constructs. This is a critical metric because synthesizing unstable materials is wasteful and unproductive. The rate is often expressed as a percentage, representing the ratio of stable materials generated to the total number of materials produced by the model. Therefore, optimizing generative models to maximize the stable material rate is a key objective, reflecting a successful strategy for reducing experimental costs and enhancing the efficiency of material discovery.

Generative Process#

A generative process, in the context of a research paper on material generation using Large Language Models (LLMs) and Riemannian Flow Matching (RFM), typically involves a two-stage process. First, an LLM generates an initial material representation, often as a text-based description or a string encoding of atomic properties and lattice parameters. This initial representation is inherently noisy and imperfect, lacking the precision needed for accurate material modeling. Second, the RFM model takes this initial representation and iteratively refines it, typically focusing on continuous variables like atomic coordinates and lattice parameters, to generate a more accurate and stable material structure. The RFM component acts as a noise-reduction process, improving the quality of the initial LLM generation. The combined approach leverages the strength of LLMs for discrete variable generation and the suitability of RFM for refining continuous properties. This hybrid approach is crucial because directly training an LLM to handle both discrete and continuous aspects is challenging, and separately trained models lack the synergistic benefits provided by combining both LLM and RFM methods.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of material generation, this might involve removing the large language model (LLM) component, the Riemannian flow matching (RFM) component, or different parts of either. By comparing the performance of the complete model against the simpler versions, researchers determine the importance of each part for achieving high-quality outputs, such as higher stability rates and unique, novel crystal structures. A well-designed ablation study helps confirm the efficacy of the proposed model architecture and pinpoint which elements are most crucial. It may also reveal unexpected interactions between model components, suggesting avenues for further improvement or refinement. For instance, the ablation study might unexpectedly reveal that the LLM’s learned base distribution is essential for superior results, rather than just serving as an initialization. The results provide a crucial validation, demonstrating which features are essential and informing future design choices. The ablation study could also directly compare the results of the combined LLM-RFM model against simpler combinations, like only using the LLM to generate materials directly, to further highlight the advantages of the hybrid architecture.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from the FlowLLM paper could involve several key areas. Improving the efficiency of the model is crucial; reducing computational cost associated with training and sampling would broaden accessibility and enable larger-scale explorations of chemical space. Extending FlowLLM to handle more complex systems is also critical; this could include addressing issues like defects, surfaces, and interfaces within materials, or moving beyond bulk materials to encompass nanomaterials and 2D materials. Combining FlowLLM with other generative models or machine learning techniques might unlock further synergistic advantages, perhaps leveraging the strengths of different approaches to enhance prediction accuracy and explore a wider range of material properties. Finally, developing methods for inverse design within the FlowLLM framework would be a significant advancement; the ability to directly synthesize materials with desired properties would transform material discovery. Addressing the limitations of reliance on pre-trained LLMs by exploring alternative methods for creating a base distribution or incorporating domain knowledge more directly into the model could further improve performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

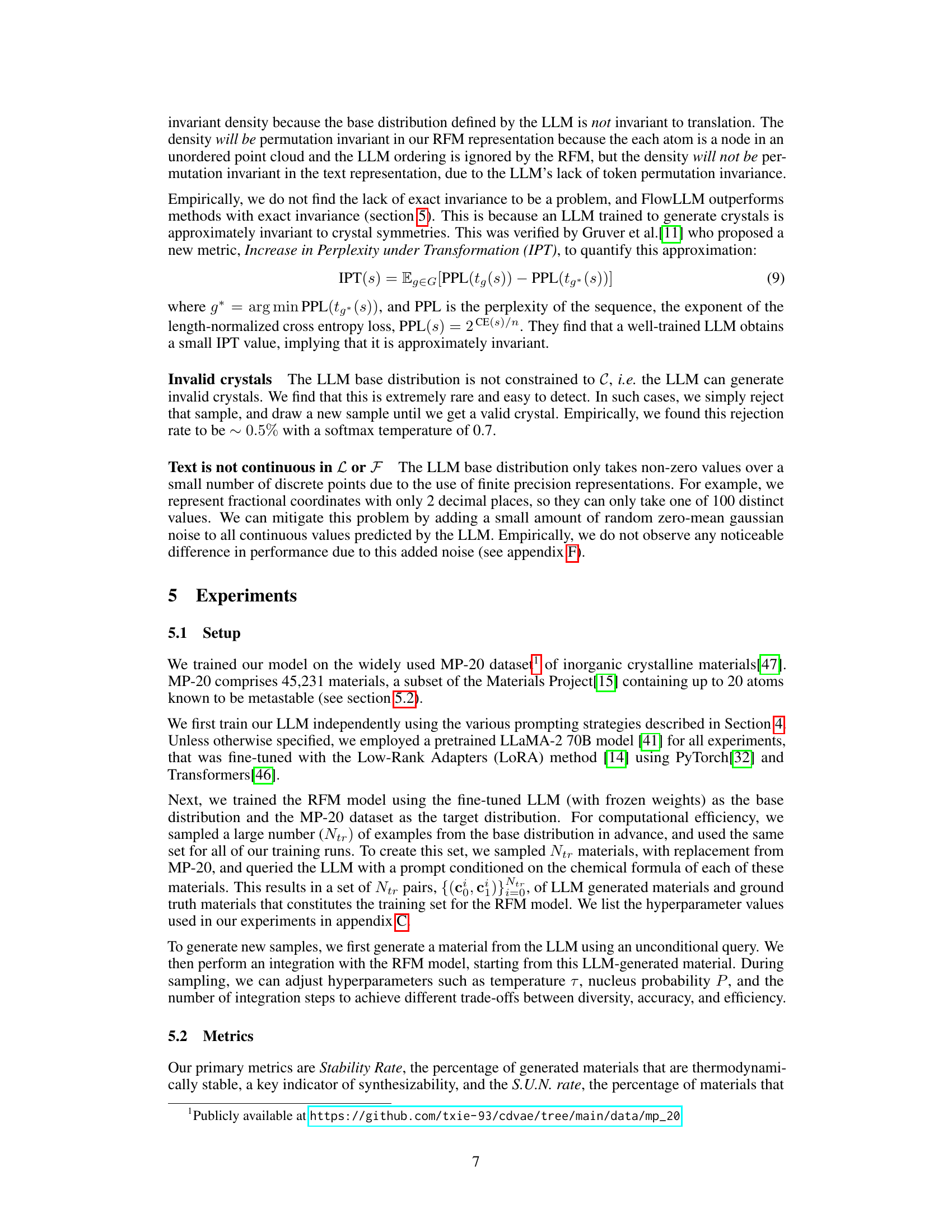

🔼 This figure illustrates the string encoding method used for representing materials in the LLM training process. The left side shows how the chemical formula and lattice parameters are converted into a string format used as input for the LLM. The right side shows an example of a prompt used to generate material representations during training. This prompt uses a conditional approach and indicates that the LLM should take the chemical formula (optional) and generate a detailed crystal structure description. The parts in red and blue represent where the inputs are replaced in the prompt for training.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: String encoding of materials used to train the LLM based on Gruver et al.[11]. Right: An example prompt used during training. The conditioning information in blue is optional, and can be replaced with conditioning on other properties as well. The text in red is replaced with the crystal string representation shown on the left.

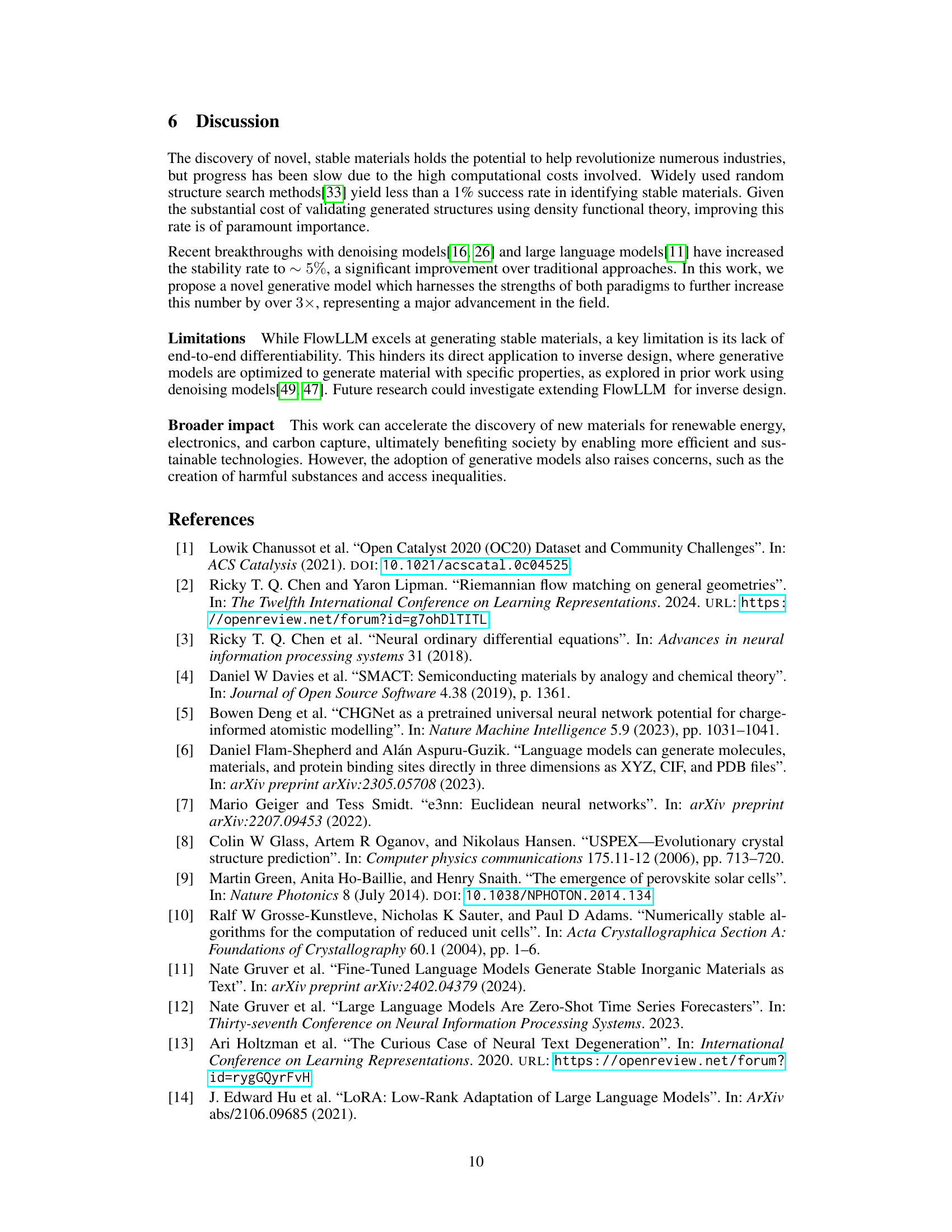

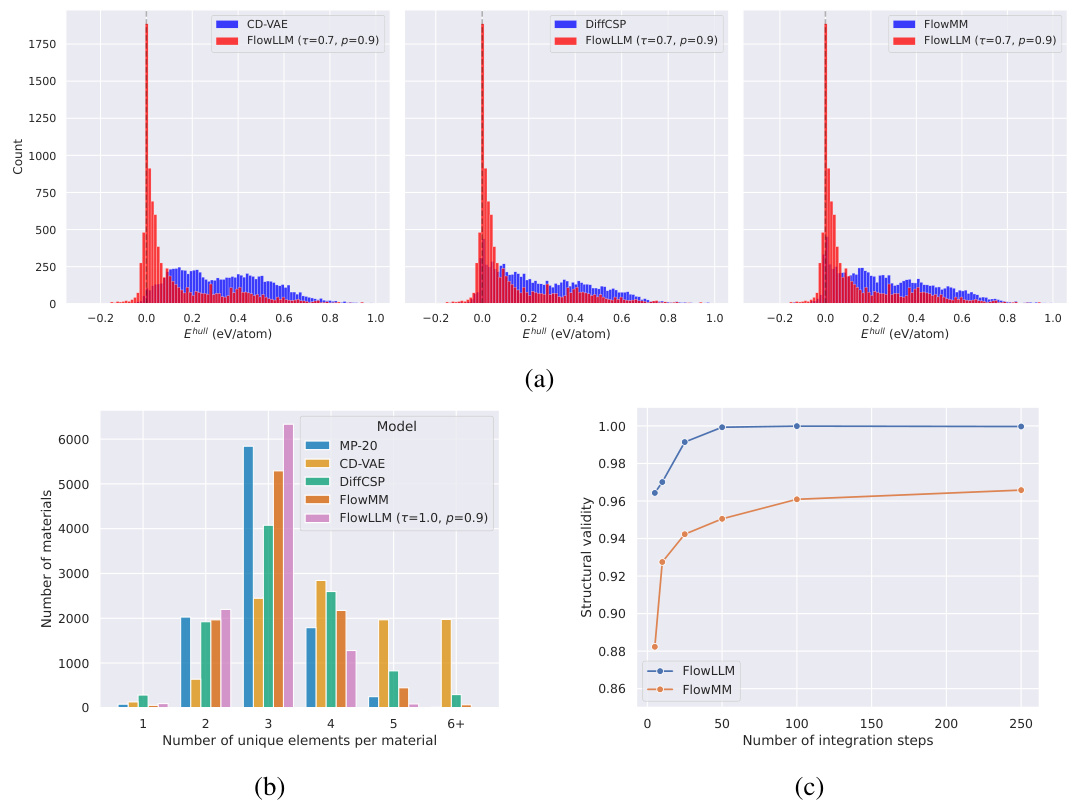

🔼 This figure compares FlowLLM’s performance against other models in terms of energy above the hull (Ehull), the number of unique elements per material (N-ary), and structural validity. Panel (a) shows histograms of Ehull, demonstrating FlowLLM’s generation of more stable materials. Panel (b) presents N-ary distributions, highlighting FlowLLM’s better match to the data distribution. Finally, panel (c) illustrates how the structural validity of generated materials improves with more integration steps during the FlowLLM process.

read the caption

Figure 3: (a) Histogram of Ehull values comparing FlowLLM with prior models. The dashed line shows thermodynamic stability threshold (Ehull = 0). (b) Histogram of N-ary compared to the data distribution. (c) Structural validity as a function of number of integration steps.

More on tables

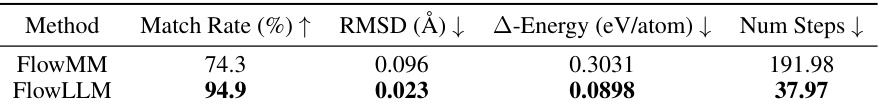

🔼 This table compares the generated structures from FlowMM and FlowLLM models to their corresponding ground state structures after relaxation using CHGNet. The metrics used for comparison are Match Rate (percentage of generated structures similar to their ground state structures), RMSD (root mean square deviation between generated and ground state structures), Δ-Energy (energy difference between generated and ground state structures), and Num Steps (number of optimization steps needed to pre-relax the generated structure using CHGNet). The results demonstrate that FlowLLM generates structures significantly closer to their ground state compared to FlowMM, indicating improved model performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of generated and corresponding ground state structures from the CHGNet relaxation. Compared to FlowMM, FlowLLM generates structures much closer to the ground state.

🔼 This table presents the results of material generation experiments using several methods on the MP-20 dataset. The key metrics are Validity, Coverage (the percentage of the material space covered), Structural Composition (Recall and Precision measuring how well the generated structures match the real ones), weighted distance, Stability Rate (percentage of generated materials that are thermodynamically stable), and SUN Rate (percentage of stable, unique, and novel materials). The table compares the performance of FlowLLM against existing state-of-the-art methods such as CDVAE, DiffCSP, FlowMM, and CrystalLLM, showing that FlowLLM significantly outperforms the others on stability and SUN rates.

read the caption

Table 1: Results for material generation on the MP-20 dataset. Stability rate is the percentage of generated materials with Ehull < 0.0 & N-ary ≥ 2.

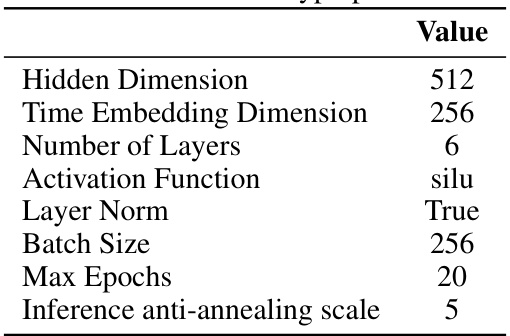

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of adding Gaussian noise to continuous values predicted by the LLM in the FlowLLM model. Four different noise standard deviations (0, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.04) were tested. The metrics evaluated were Validity (Structural and Composition), and Coverage (Recall and Precision). The results show that adding noise did not significantly impact these proxy metrics, suggesting that the LLM’s base distribution is relatively robust to noise.

read the caption

Table 4: Proxy metrics for a FlowLLM trained with different levels of random gaussian noise added to continuous values predicted by the LLM. Added noise increases the support of the base distribution, but we do not see an appreciable difference in the metrics.

Full paper#