TL;DR#

Online matching, where one side of a market arrives sequentially, is often studied focusing on maximizing total matches. This paper, however, shifts the focus to fairness, aiming to maximize the minimum matching rate across all online agent types. This poses challenges, as traditional methods often fall short of providing fair outcomes and are not optimal in many cases. Existing benchmarks are not sufficient to evaluate such fairness-focused policies. The paper also shows that simpler policies like First-Come-First-Serve are not generally sufficient to achieve fairness.

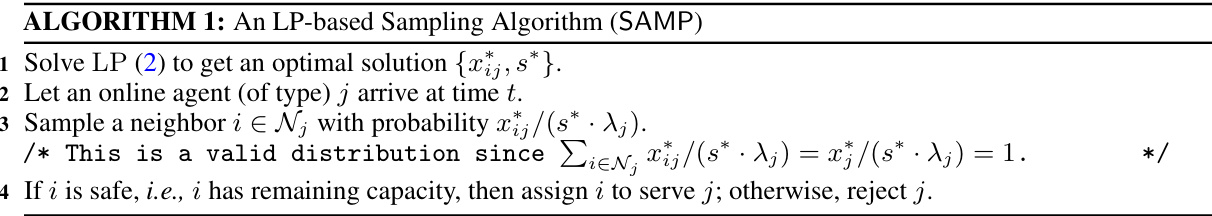

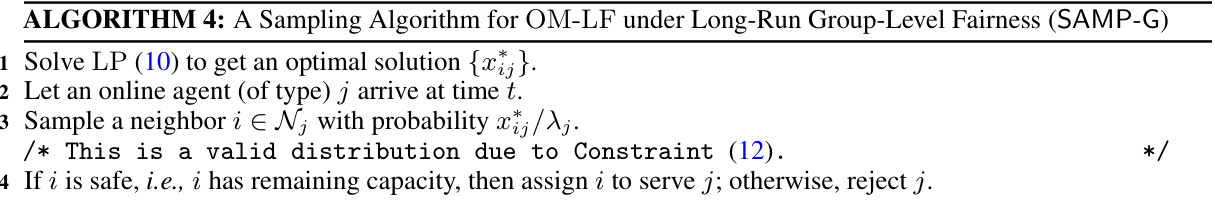

The paper proposes a novel sampling algorithm (SAMP) that effectively addresses these challenges. It proves the algorithm’s competitiveness and demonstrates its asymptotic optimality under specific conditions. The algorithm leverages a benchmark linear program (LP) to guide the matching process, improving fairness. The paper also explores extensions to group-level fairness, providing additional algorithms and analysis. Overall, the research makes significant contributions to the theoretical understanding of fairness in online matching and provides practical solutions for achieving fairer outcomes.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on online matching markets and fairness. It introduces novel fairness metrics and algorithms, addressing a critical gap in existing research. The asymptotic optimality results provide strong theoretical foundations, while the extensions to group-level fairness offer practical relevance. This work opens up avenues for research on fairness in dynamic systems and algorithm design for complex scenarios.

Visual Insights#

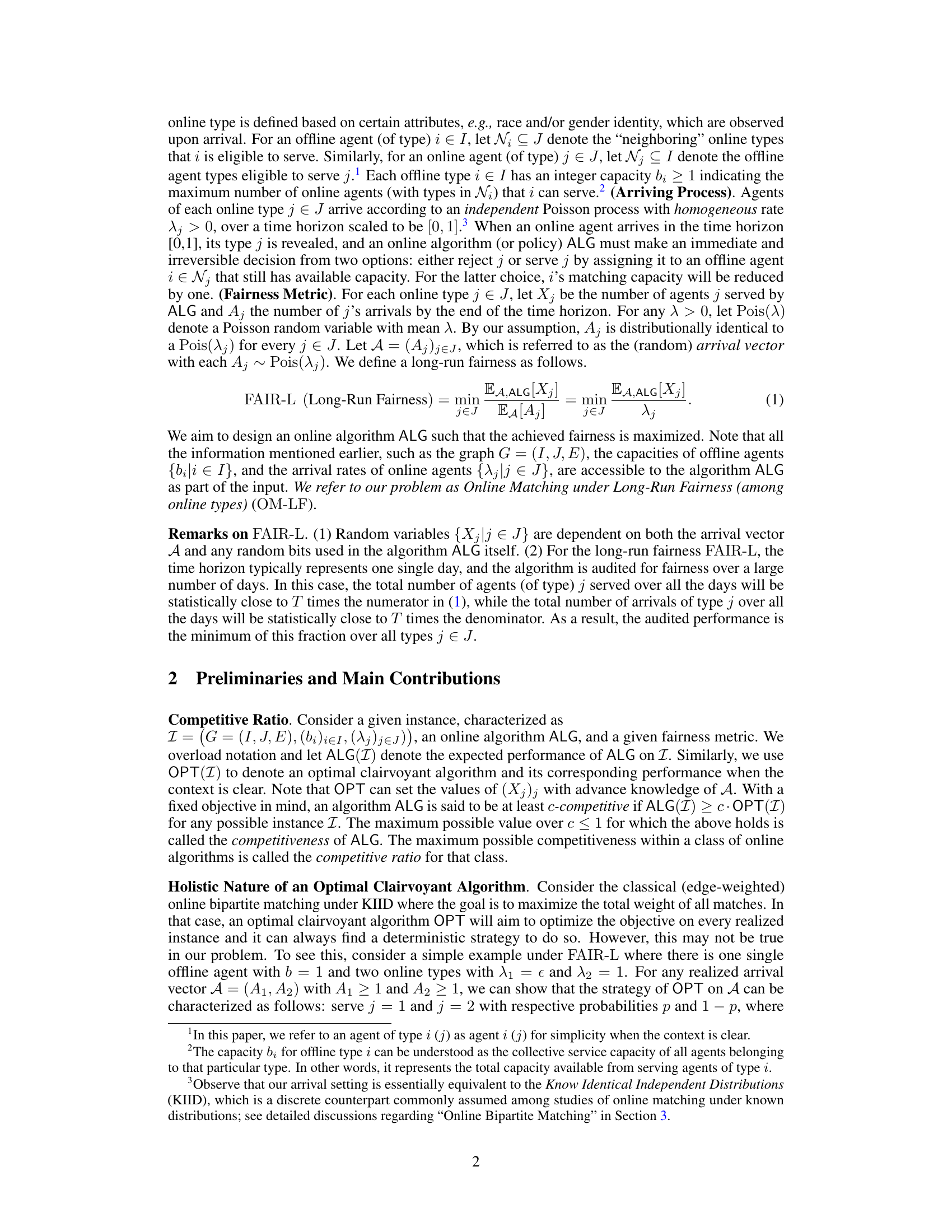

🔼 This figure presents a bipartite graph illustrating a scenario designed to demonstrate hardness results for online matching algorithms under fairness constraints. The graph consists of one common type of online agent (λ₀ = n-1) and n rare types of online agents (λᵢ = 1/n for 1 ≤ i ≤ n). Each rare type connects exclusively to one offline agent, while the common type connects to all offline agents. This setup highlights the challenge of balancing fairness across different types of agents when an algorithm must make immediate decisions about allocation without complete information.

read the caption

Figure 1: A bad example used to show hardness results for any randomized and non-rejecting algorithms and the tightness of competitive analysis for SAMP.

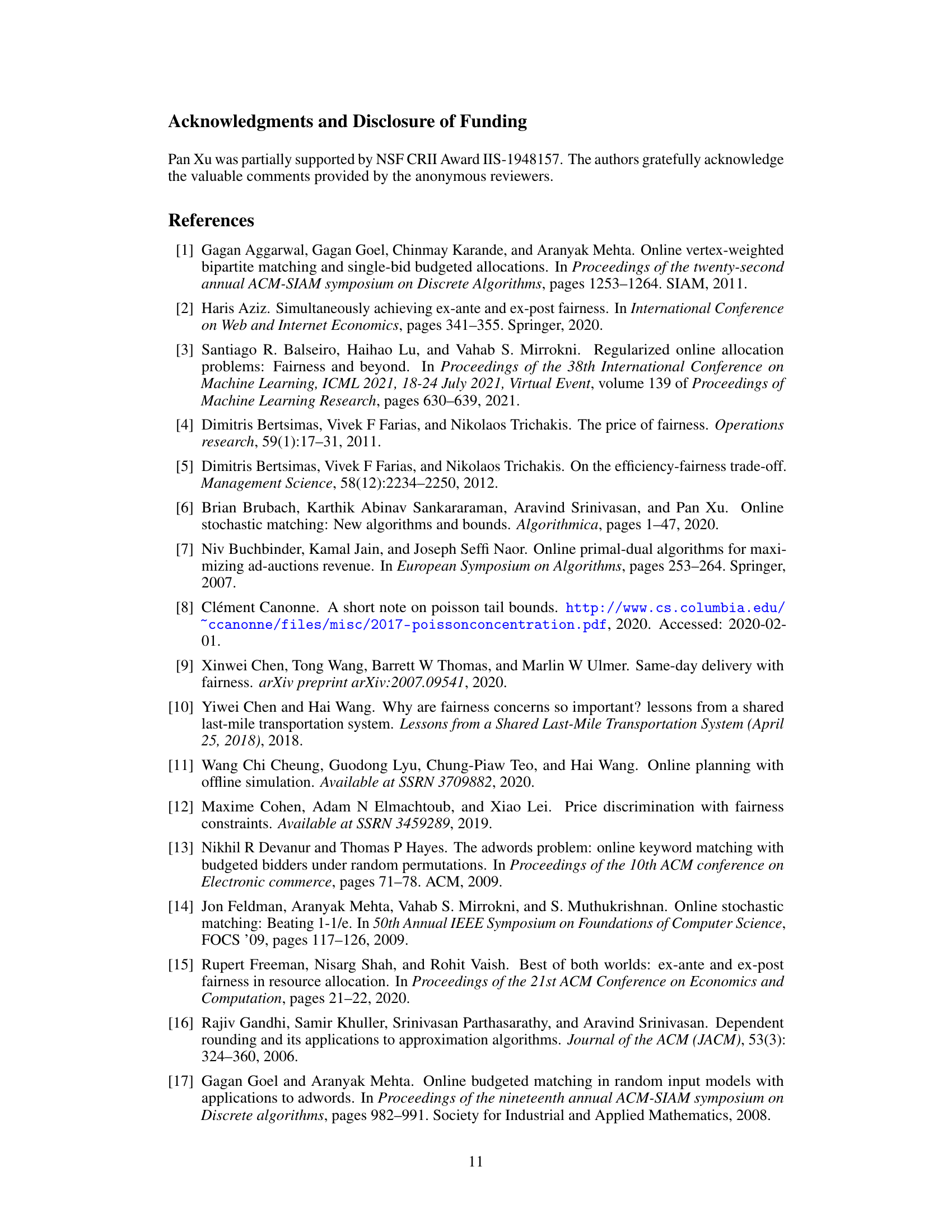

🔼 This table presents a bad example to demonstrate the hardness results for randomized and non-rejecting algorithms in online matching problems under long-run fairness. It also illustrates the tightness of the competitive analysis of the SAMP algorithm. The example involves a bipartite graph with multiple rare online types and a single common type, along with several offline agents each capable of serving only specific online types. This setup is designed to show that non-rejecting algorithms cannot achieve better than 1/2-competitiveness, while highlighting the near-optimal performance of SAMP in specific scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: A bad example used to show hardness results for any randomized and non-rejecting algorithms and the tightness of competitive analysis for SAMP.

In-depth insights#

Fairness in Matching#

Fairness in matching algorithms is a crucial consideration, especially in scenarios with sensitive attributes like gender or race. Algorithmic bias can disproportionately impact certain groups, leading to unfair outcomes. The paper likely explores different notions of fairness, such as individual fairness (equal treatment for similar individuals) and group fairness (equal representation across groups). Different fairness definitions often conflict, creating trade-offs that must be carefully managed. The authors probably investigate algorithmic approaches that attempt to achieve a balance between fairness and overall efficiency of the matching process, perhaps quantifying the trade-off using metrics like competitive ratio. The analysis likely delves into the computational complexity of achieving fairness, and explores the impact of various system parameters such as the number of agents and the distribution of their attributes. Furthermore, the paper might cover the fairness implications of specific matching algorithms and suggest modifications to ensure equitable treatment. Real-world applications in domains like job markets or organ allocation are significant contexts for demonstrating the practical value of fair matching algorithms.

SAMP Algorithm#

The SAMP algorithm, a core contribution of the research paper, presents a novel approach to online matching under long-run fairness constraints. Its key innovation lies in leveraging a benchmark linear program (LP) to guide the online decision-making process. Instead of directly solving the LP, SAMP cleverly uses its solution to inform a sampling distribution, probabilistically choosing an offline agent to match with an arriving online agent. This approach offers a compelling balance between fairness and efficiency. The algorithm’s competitiveness is rigorously analyzed, demonstrating its effectiveness in diverse scenarios, particularly when resources are abundant or agent types have high arrival rates. Importantly, the paper demonstrates that SAMP’s performance approaches optimality under certain conditions, making it a significant advancement in the field. However, the algorithm does have limitations, such as not being 1-competitive in all cases and the reliance on solving an LP. Future work could explore enhancements to address these limitations and extend the applicability of SAMP to even more complex scenarios.

OM-LF Hardness#

The section ‘OM-LF Hardness’ would delve into the computational complexity of the Online Matching under Long-Run Fairness problem. It would likely establish lower bounds on the achievable competitive ratio for any algorithm attempting to solve OM-LF. This means proving that no algorithm can perform better than a certain factor compared to an optimal solution, even with complete knowledge of future arrivals. The analysis might involve constructing specific, difficult problem instances that expose the limitations of online algorithms. The hardness results would highlight the inherent difficulty of the problem, which stems from the need to balance fairness across different online types with the dynamic and unpredictable nature of online arrivals. These results provide crucial context for evaluating the performance of proposed OM-LF algorithms; a tight lower bound demonstrates that an algorithm’s achieved performance is close to optimal. Furthermore, the section could investigate different types of hardness, such as deterministic vs. randomized policies, potentially showing varying levels of difficulty depending on the algorithm’s design choices. Ultimately, this section would underscore the significance of the positive results presented in the paper by framing them within the context of inherent problem difficulty.

Group Fairness#

The concept of group fairness extends individual fairness by considering the collective well-being of subgroups within a population. Instead of focusing on equal treatment for each individual, group fairness aims to ensure that protected groups are not disproportionately disadvantaged compared to other groups. This is particularly relevant in online matching markets where decisions, if not carefully considered, could systematically disadvantage certain demographic or social groups. Algorithms designed for group fairness must balance individual needs with the overall equity of outcomes across different groups. The challenges lie in defining appropriate metrics for group fairness, accounting for overlaps between groups, and devising algorithms that can efficiently maximize fairness without sacrificing overall system performance. Algorithmic approaches to group fairness require careful consideration of the specific context and potential trade-offs, often involving a balance between theoretical guarantees and real-world applicability. A key challenge is handling situations with overlapping group memberships and differing group sizes, ensuring that a fair allocation is possible without creating unintended consequences for certain subgroups. Ultimately, achieving group fairness requires both appropriate mathematical formulations and computationally efficient algorithms that can handle the complexity of real-world scenarios.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore relaxing the assumption of known stationary arrival distributions. Real-world scenarios often involve dynamic and unpredictable arrival patterns. Investigating how fairness can be maintained under such conditions is crucial. Another avenue is to examine different fairness metrics beyond long-run and short-run fairness. For instance, exploring notions of fairness incorporating temporal aspects or focusing on specific subgroups within the online agent population would offer richer insights. The development of more efficient and scalable algorithms for larger-scale problems is also critical. Integrating fairness considerations into existing online matching frameworks widely used in various applications would be valuable. Finally, a deeper examination of the tradeoffs between fairness, efficiency, and the overall system performance is needed for a holistic understanding of the problem. Empirically validating these theoretical findings with real-world data from various online matching platforms would help assess the effectiveness and generalizability of proposed algorithms and frameworks.

More visual insights#

More on tables

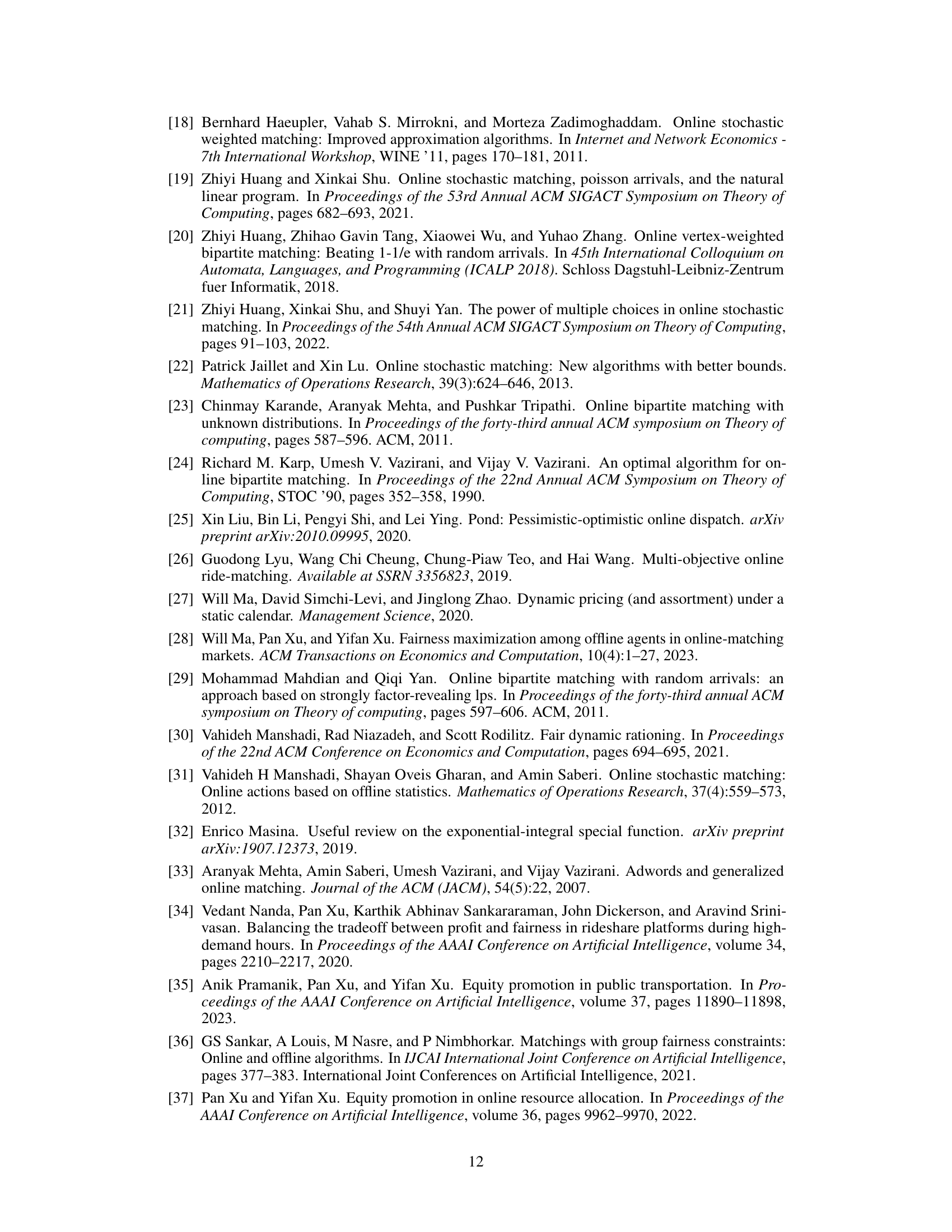

🔼 This table presents a specific example graph structure used in the paper’s analysis to prove hardness results. The graph is a bipartite graph representing an online matching problem with multiple ‘rare types’ of online agents and a ‘common type’. Each rare type can only be matched with a single offline server, while the common type can be matched with any server. The table helps illustrate the limitations of non-rejecting policies and randomized policies and demonstrates the tightness of the algorithm SAMP’s competitive ratio. Arrival rates of the different online agent types are also specified to support the analysis.

read the caption

Table 1: A bad example used to show hardness results for any randomized and non-rejecting algorithms and the tightness of competitive analysis for SAMP.

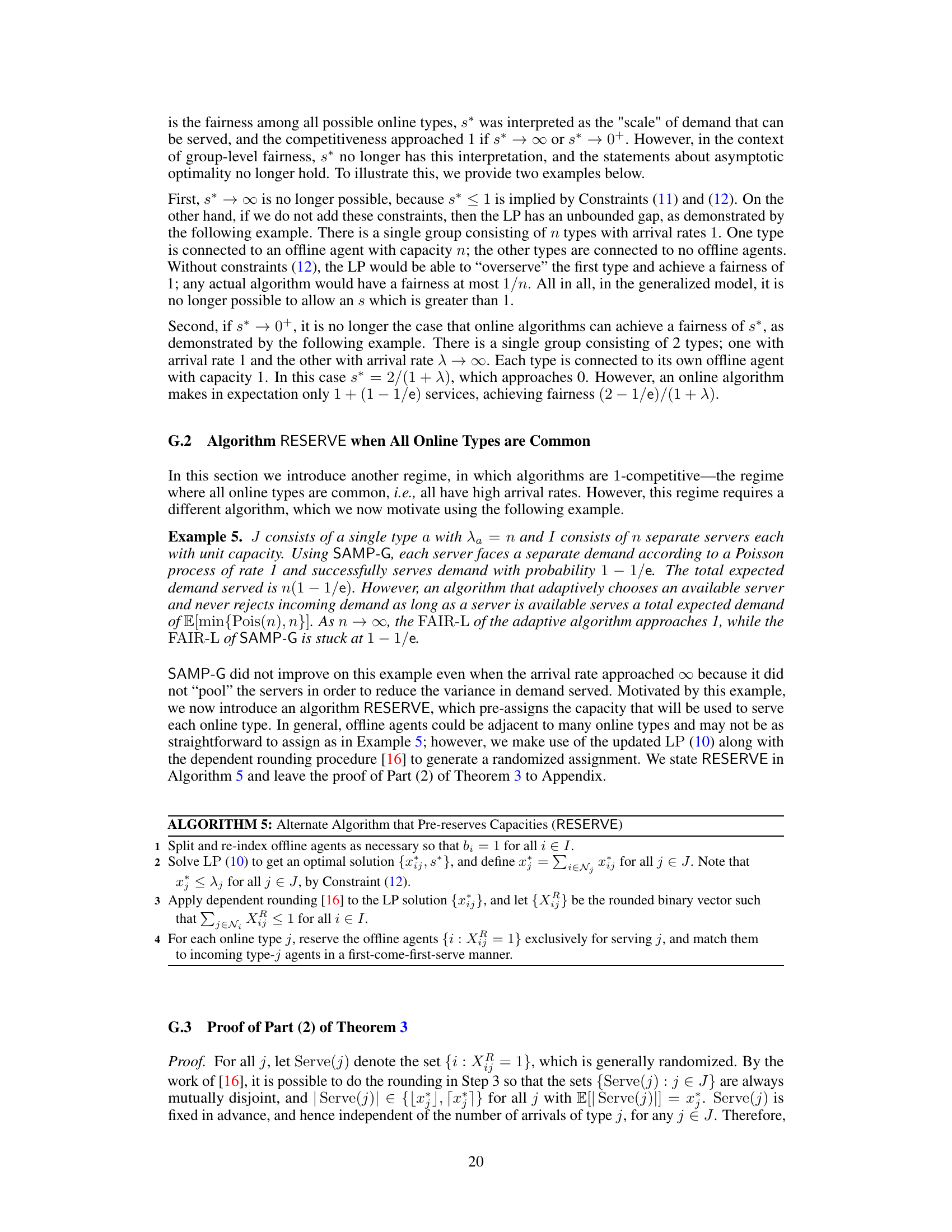

🔼 The RESERVE algorithm first solves a linear program to determine the optimal allocation of offline agents to online types, then uses dependent rounding to create a randomized assignment of offline agents to online types. Finally, it uses a first-come-first-serve policy to match incoming online agents to their pre-assigned offline agents.

read the caption

Algorithm 5: Alternate Algorithm that Pre-reserves Capacities (RESERVE)

Full paper#