TL;DR#

Analyzing human mobility patterns from location-based services (LBS) is crucial. Existing methods often fall short by neglecting the rich semantic information present in check-in sequences. This leads to an incomplete understanding of user intentions and preferences, limiting the accuracy of predictive models. This paper tackles this problem by introducing Mobility-LLM.

Mobility-LLM uses a novel framework that leverages the semantic understanding capabilities of LLMs to analyze check-in sequences. It does so by reprogramming the sequences into a format that LLMs can interpret, using a Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN) and Human Travel Preference Prompts (HTPP). The results on multiple datasets and tasks show significantly better performance compared to existing models. The study highlights the potential of LLMs in extracting richer insights from human mobility data, leading to advancements in various LBS-related applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between human mobility data analysis and the power of large language models (LLMs). By showing how LLMs can effectively analyze check-in sequences, it opens new avenues for research in location prediction, user identification, and time prediction. The methodology is applicable to various domains, making it highly relevant to current research trends in AI and human behavior understanding. The impressive results and detailed experimental setup further enhance its value to the research community.

Visual Insights#

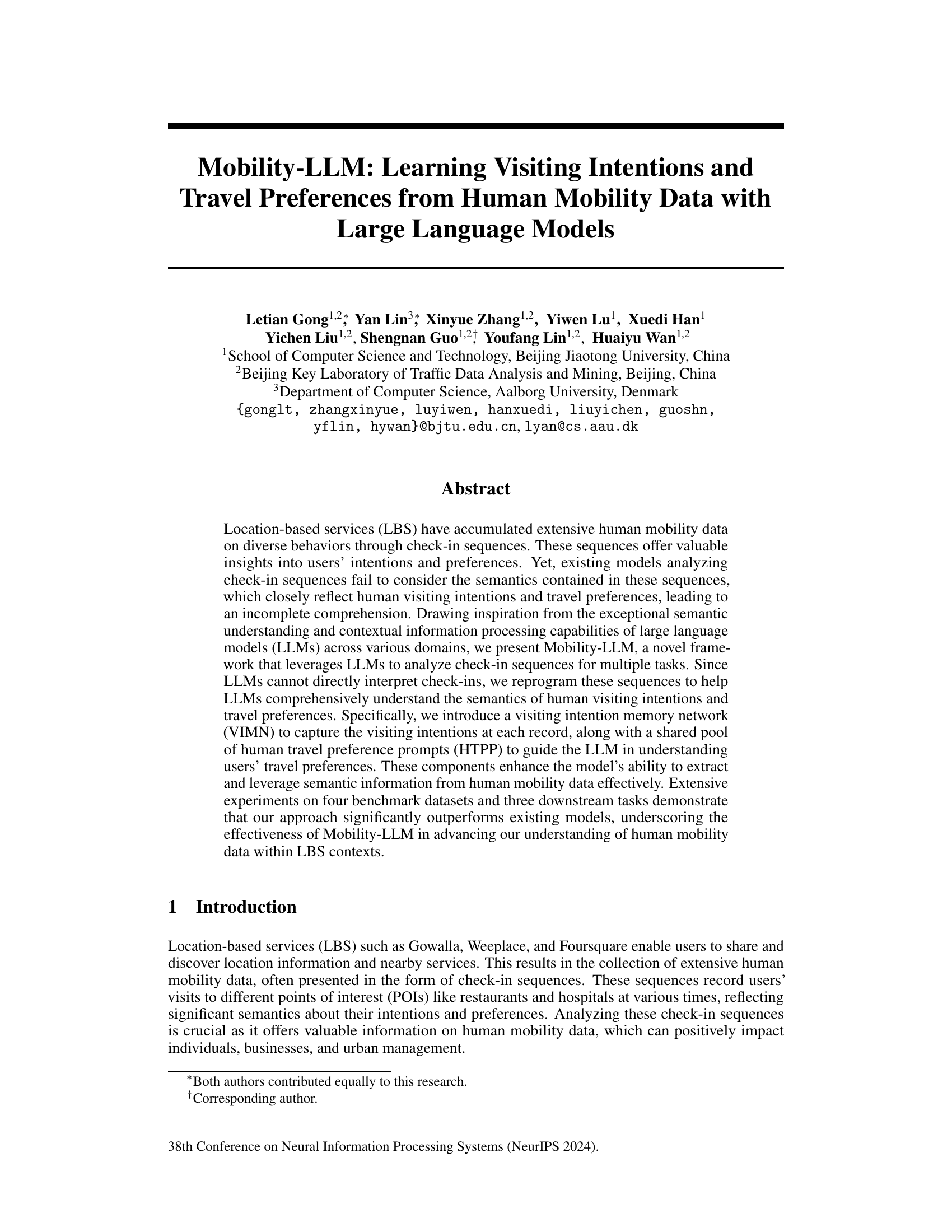

🔼 This figure presents the Mobility-LLM framework, which consists of four main components: 1. POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL) to generate semantic information embedding for each POI in a check-in record. 2. Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN) to capture users’ visiting intentions at each check-in record by prioritizing relevant check-in records. 3. Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP) pool to extract users’ preferences from check-in sequences. 4. A pre-trained LLM (Partially-Frozen + LoRA) that takes the output of VIMN and HTPP as input to perform different downstream tasks (Location prediction, Time prediction and User link prediction).

read the caption

Figure 1: The overall of our Mobility-LLM framework. a) POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL). b) Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN). c) Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP). d) a denotes the output of the LLM corresponding to VIMN (i.e. first n output of the LLM), while the remaining outputs are denoted as β.

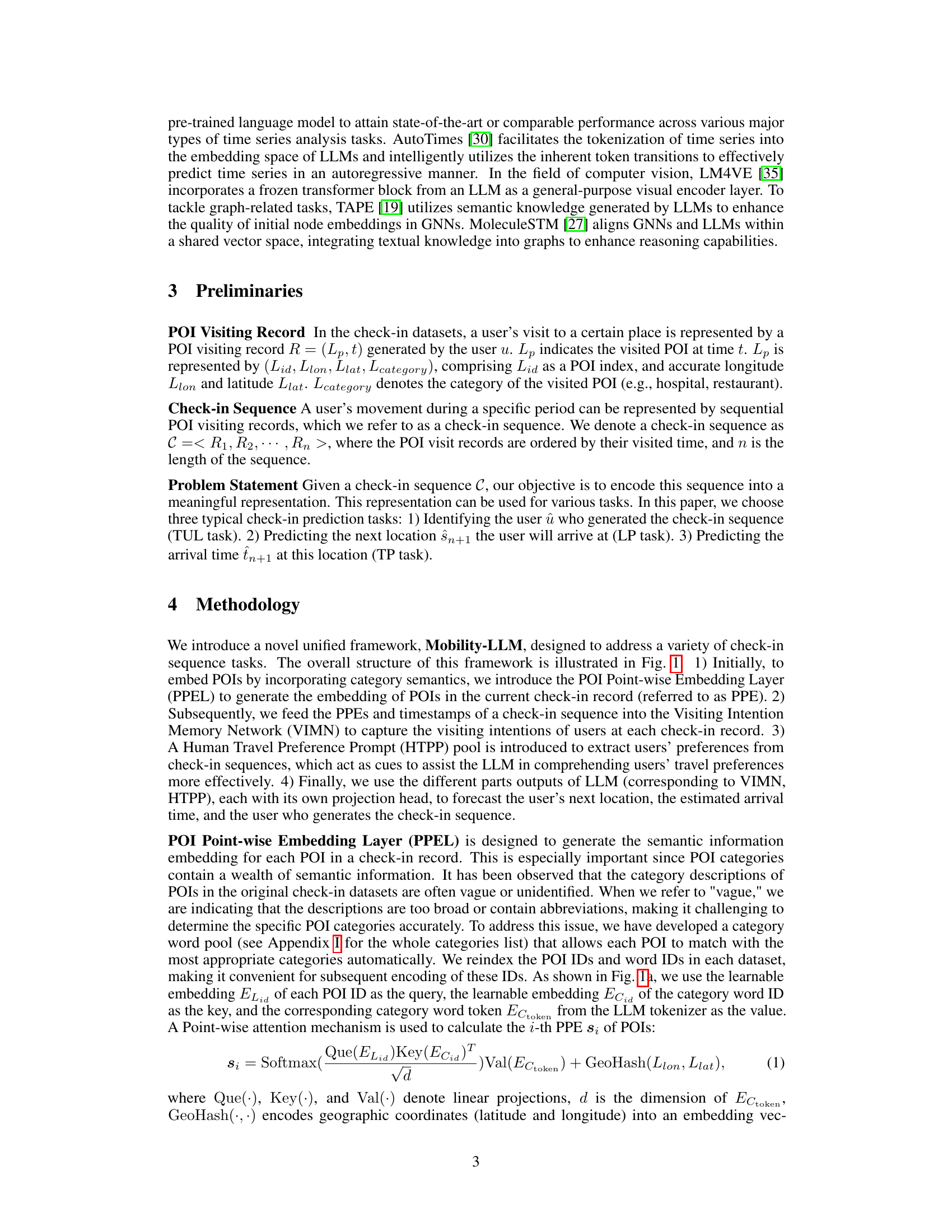

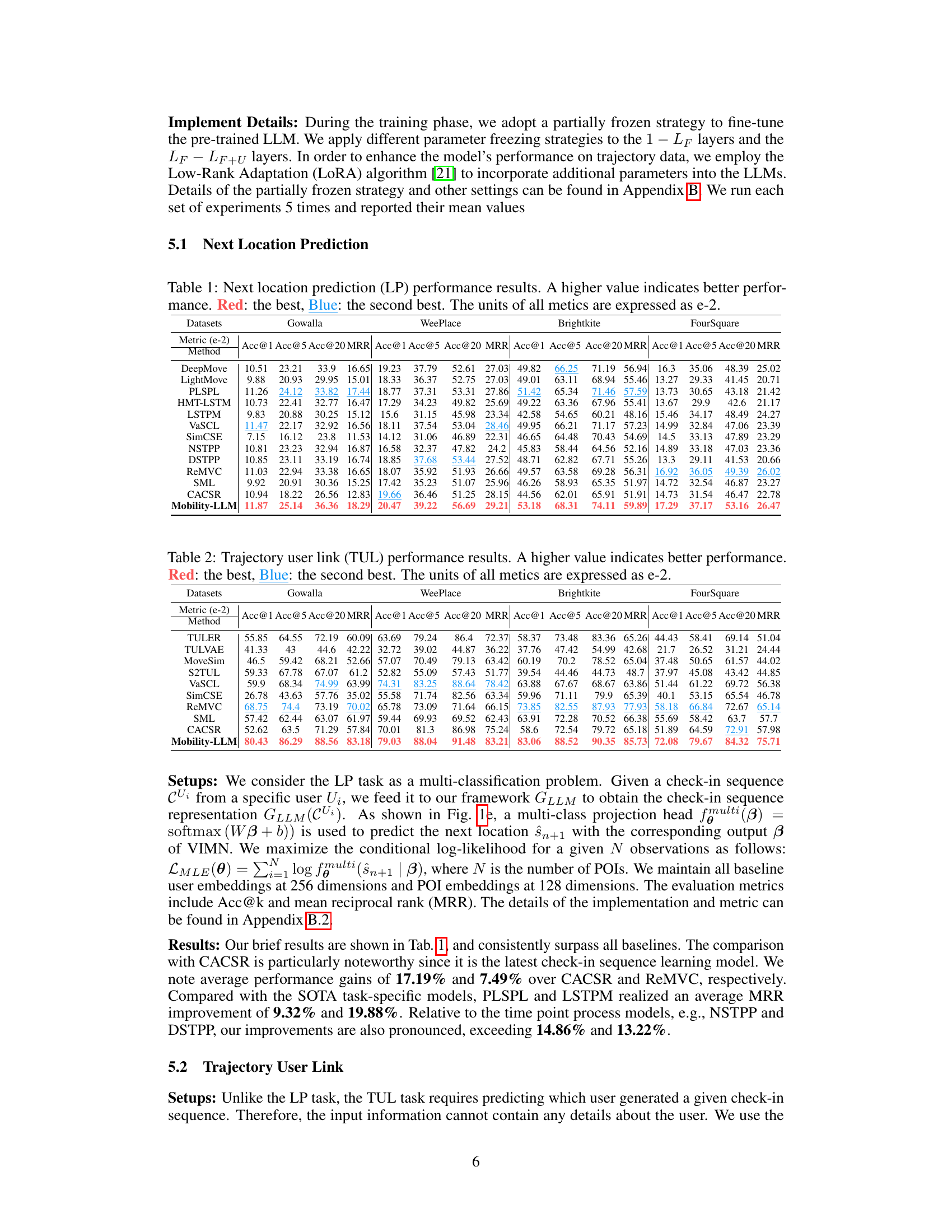

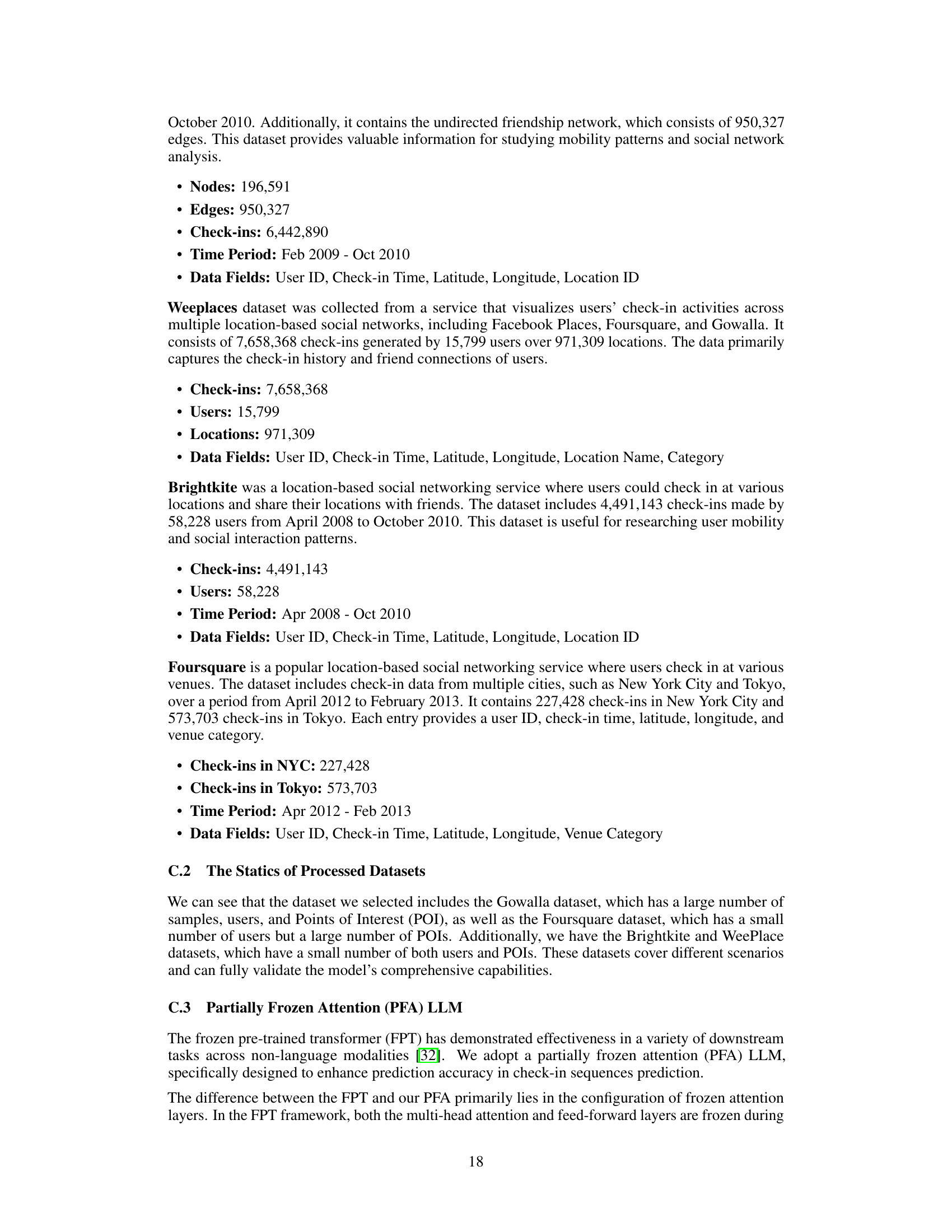

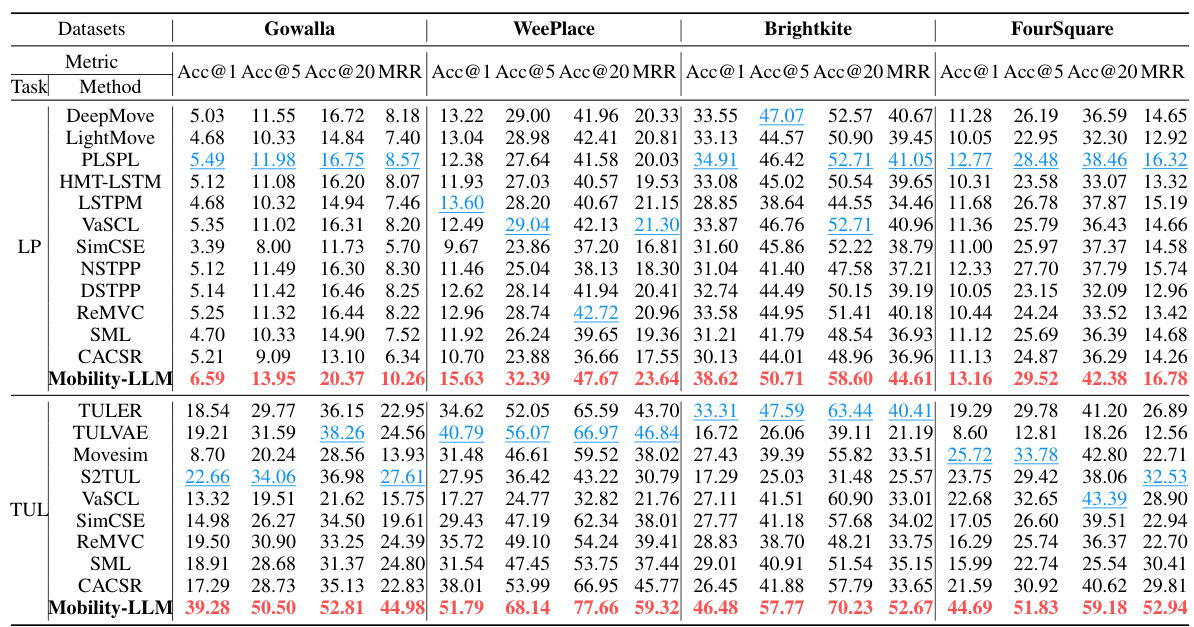

🔼 This table presents the performance of various next location prediction models on four different datasets (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and FourSquare). The metrics used to evaluate performance are Accuracy@1, Accuracy@5, Accuracy@20, and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). Higher values for each metric indicate better performance. The table highlights the best (red) and second-best (blue) performing models for each dataset and metric. The results are expressed as a percentage multiplied by 100.

read the caption

Table 1: Next location prediction (LP) performance results. A higher value indicates better performance. Red: the best, Blue: the second best. The units of all metics are expressed as e-2.

In-depth insights#

Mobility LLM Intro#

A hypothetical ‘Mobility-LLM Intro’ section would likely introduce the core concept: leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) to analyze human mobility data. It would highlight the limitations of existing methods, which often neglect the semantic richness of check-in sequences. The introduction would emphasize the potential of LLMs to capture visiting intentions and travel preferences, aspects crucial for a deeper understanding of human mobility patterns. This would then set the stage for the paper’s core contribution—a novel framework that uses LLMs to extract meaningful insights from location-based services data. The introduction might also briefly touch on the technical challenges and the proposed solutions, such as converting check-in data into LLM-interpretable formats and using specialized network architectures to enhance performance. Finally, a strong conclusion would state the paper’s objective —demonstrating that the proposed method outperforms current state-of-the-art techniques.

VIMN & HTPP#

The research paper introduces two novel components, VIMN (Visiting Intention Memory Network) and HTPP (Human Travel Preference Prompts), designed to enhance the understanding of human mobility data. VIMN focuses on capturing the dynamic evolution of a user’s visiting intentions over time by prioritizing relevant past check-ins. This temporal weighting allows the model to better contextualize current check-in behaviors, improving prediction accuracy. HTPP leverages a shared pool of prompts representing various travel preferences. This shared pool guides the LLM in understanding users’ underlying travel patterns and motivations, thus facilitating more nuanced predictions. The combined usage of VIMN and HTPP is crucial as it enables the LLM to capture both the immediate visiting intentions and the broader, long-term travel preferences of the user, providing a more comprehensive and accurate representation of their mobility patterns.

Experiment Results#

The “Experiment Results” section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims and demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed methods. A strong results section will clearly present the key findings, using tables, figures, and statistical measures to support the claims made earlier in the paper. The discussion should go beyond simply stating the numerical results. It should provide a comprehensive analysis of the performance, including error analysis, comparisons with relevant baselines and discussion of statistical significance. Highlighting any unexpected results or limitations is also vital for demonstrating intellectual honesty and providing context for future research. A thoughtful interpretation of results is essential, connecting the findings back to the hypotheses and the broader implications of the research. Robustness analysis, for example testing under different parameters or datasets, is extremely important to showcase the reliability and generality of the proposed method. A clear and concise writing style in the result section improves the clarity and accessibility of the findings, ensuring the reader can easily understand the significance of the experiments.

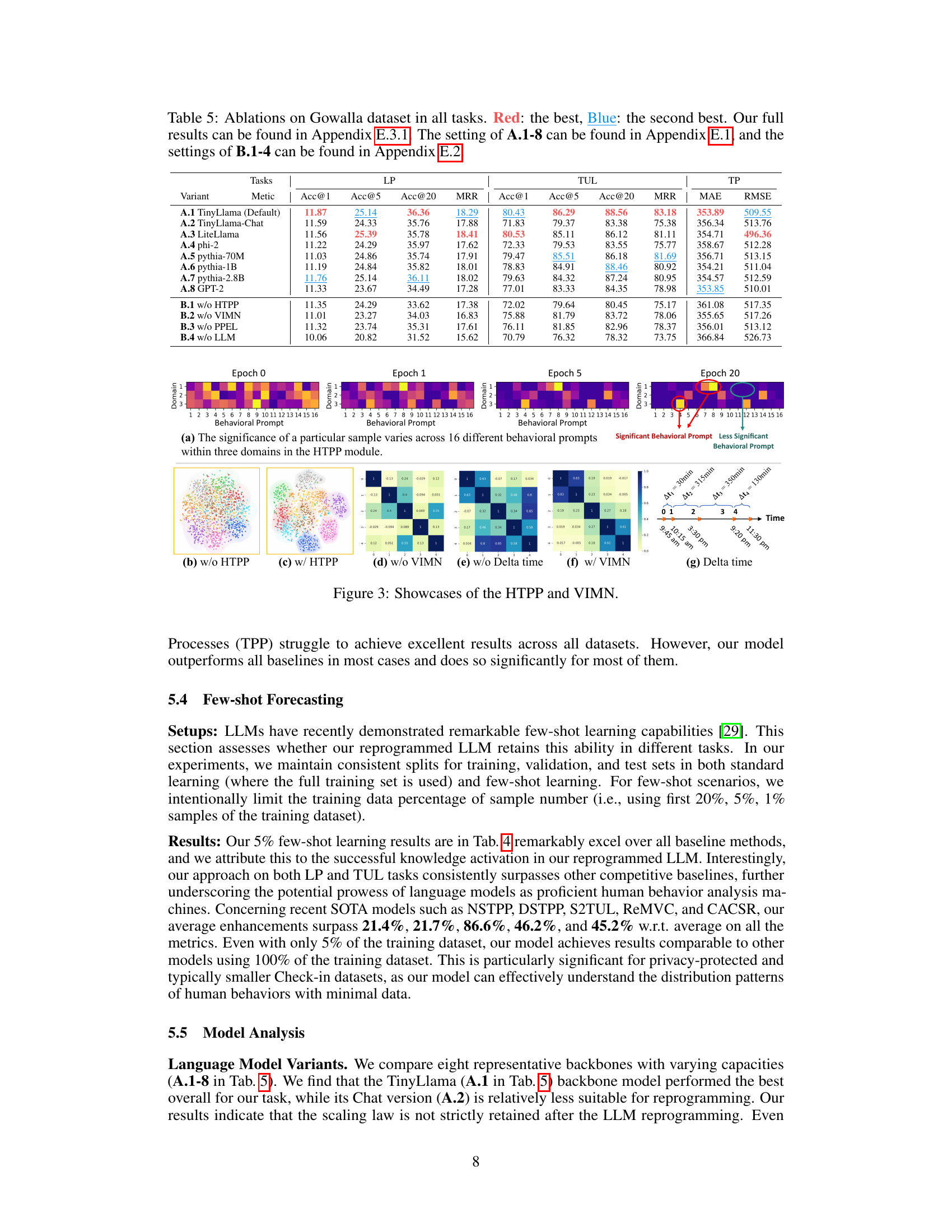

Few-Shot Learning#

The concept of few-shot learning, applied within the context of analyzing human mobility data using large language models, is particularly insightful. It directly addresses the challenge of limited labeled data, a common problem in real-world applications. By leveraging the power of pre-trained LLMs, the model demonstrates impressive adaptability, achieving significant performance gains even with drastically reduced training data. This highlights the potential of LLMs to extract meaningful semantic information from mobility patterns, transcending the limitations of traditional approaches which often rely on extensive datasets. The few-shot learning success underscores the robustness of the model’s architecture, showcasing its ability to effectively generalize from limited examples. This approach opens up exciting new possibilities for personalized recommendations and urban planning, enabling the analysis of human movement and preferences with less data. Future research should investigate the trade-off between the size of the pre-trained LLM and its few-shot capabilities, aiming to enhance efficiency and further reduce data requirements.

Future Work#

The paper’s omission of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section presents an opportunity for insightful discussion. A natural extension would be exploring the integration of Mobility-LLM with other advanced models such as graph neural networks or transformers to further enhance the understanding of spatio-temporal dynamics in human mobility. Investigating the generalizability of Mobility-LLM across diverse LBS datasets with varying data characteristics and granularities is also crucial. Furthermore, research into improving the efficiency and scalability of Mobility-LLM, particularly for real-time applications, would be valuable. Finally, a deeper dive into the interpretability of the model’s internal representations to better understand the decision-making processes and potentially address biases would provide valuable insights and contribute to increased trust and reliability. Exploring these directions will strengthen the model’s capabilities and broaden its practical implications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

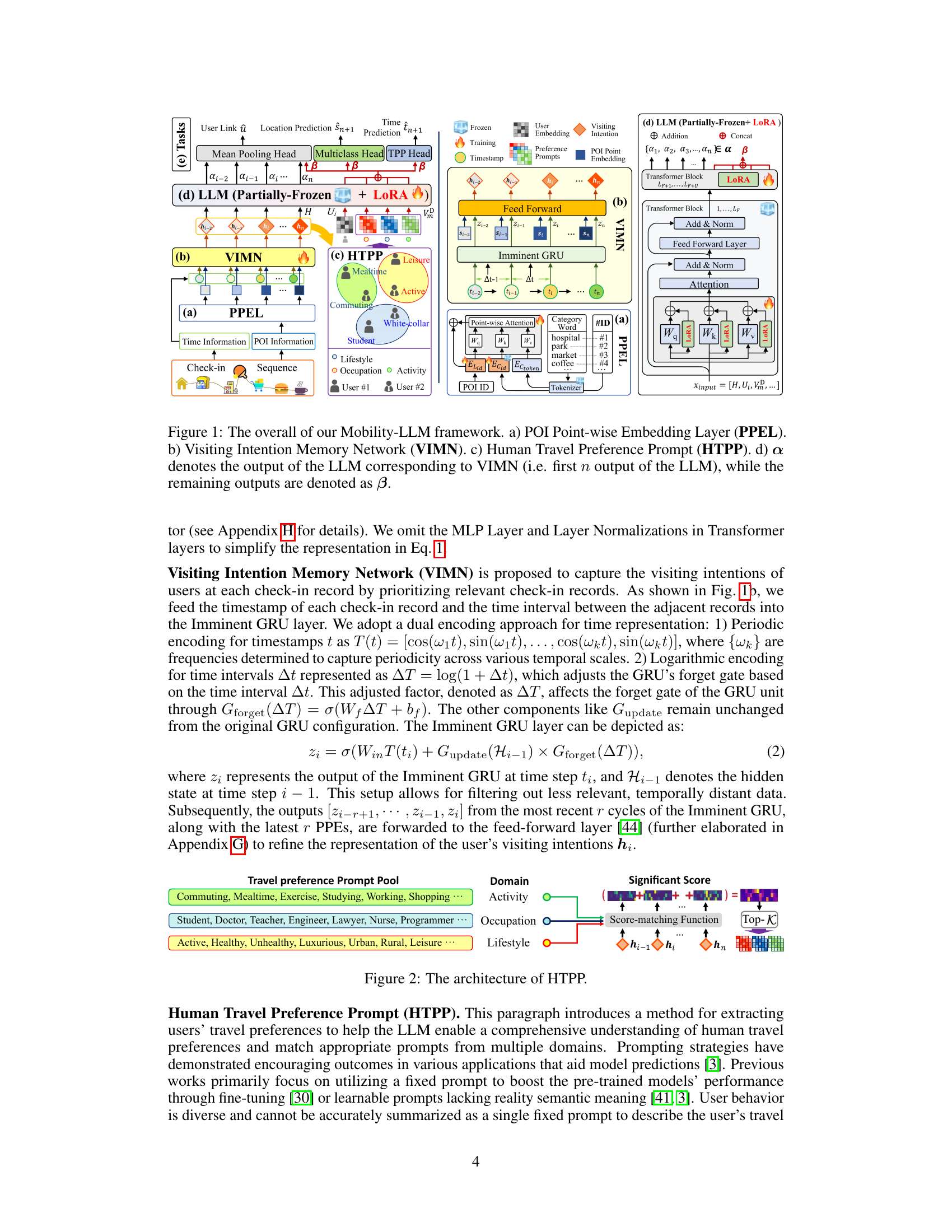

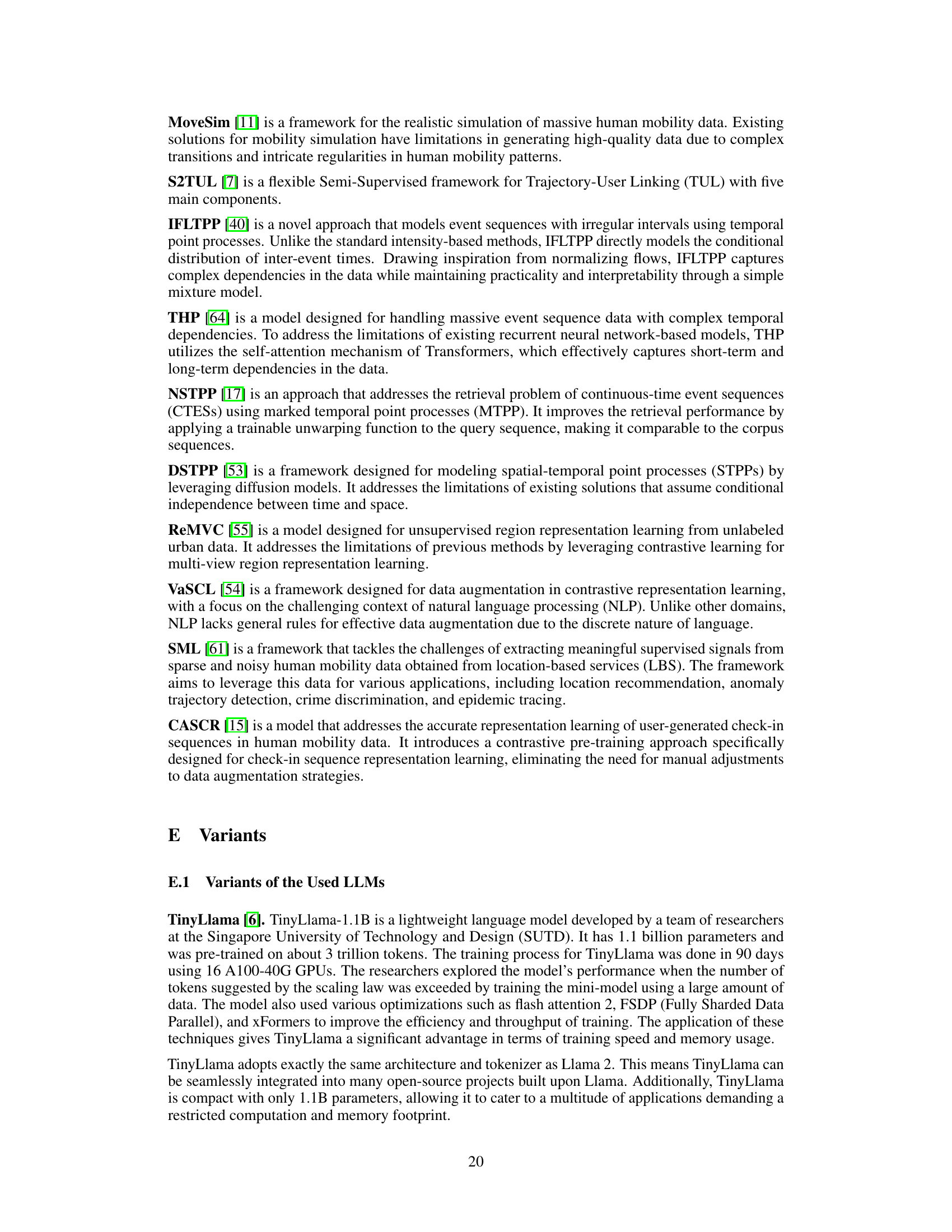

🔼 The figure illustrates the architecture of the Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP) module. It shows three domains (Activity, Occupation, Lifestyle) each with a set of prompt words. A score-matching function determines the relevance of each visiting intention (represented by hi) to the prompt words within each domain. The top-K most relevant prompt words are selected for each domain, providing a comprehensive understanding of user travel preferences.

read the caption

Figure 2: The architecture of HTPP.

🔼 This figure presents the Mobility-LLM framework’s architecture. It consists of four main components: 1. POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL): Embeds points of interest (POIs) by incorporating category semantics. 2. Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN): Captures user visiting intentions at each check-in record. 3. Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP): Extracts user travel preferences from check-in sequences. 4. Partially-Frozen LLM + LoRA: Processes the inputs (PPEs, timestamps, VIMN output, HTPP) to make predictions for location, time, and user. The figure illustrates how these components interact and contribute to the model’s ability to understand human mobility data.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overall of our Mobility-LLM framework. a) POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL). b) Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN). c) Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP). d) a denotes the output of the LLM corresponding to VIMN (i.e. first n output of the LLM), while the remaining outputs are denoted as β.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Mobility-LLM framework, a novel unified framework for check-in sequence analysis. It shows the three main components: POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL), Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN), and Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP). The PPEL generates semantic information embeddings for each POI. The VIMN captures the visiting intentions of users at each check-in record by prioritizing relevant check-in records. The HTPP extracts users’ preferences from check-in sequences, acting as cues to assist the LLM in understanding users’ travel preferences. The LLM processes the information from these three components to perform three downstream tasks: location prediction, trajectory user link, and time prediction.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overall of our Mobility-LLM framework. a) POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL). b) Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN). c) Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP). d) α denotes the output of the LLM corresponding to VIMN (i.e. first n output of the LLM), while the remaining outputs are denoted as β.

🔼 This figure presents the Mobility-LLM framework, which is a unified framework for check-in sequence analysis. The framework consists of four main components: (a) POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL) which generates embeddings for Points of Interest (POIs) considering category semantics; (b) Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN) which captures visiting intentions of users; (c) Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP) which extracts user preferences from check-in sequences; and (d) a partially frozen Large Language Model (LLM) which utilizes the information generated from the previous components to perform different check-in sequence analysis tasks. The output from the LLM is divided into two parts: α (the first n outputs corresponding to VIMN) and β (the remaining outputs).

read the caption

Figure 1: The overall of our Mobility-LLM framework. a) POI Point-wise Embedding Layer (PPEL). b) Visiting Intention Memory Network (VIMN). c) Human Travel Preference Prompt (HTPP). d) a denotes the output of the LLM corresponding to VIMN (i.e. first n output of the LLM), while the remaining outputs are denoted as β.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the performance of various methods on the Trajectory User Link (TUL) task across four different datasets (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and Foursquare). The performance is measured using four metrics: Accuracy at 1 (Acc@1), Accuracy at 5 (Acc@5), Accuracy at 20 (Acc@20), and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). Higher values for all metrics indicate better performance. The best performing method for each metric and dataset is highlighted in red, and the second-best is highlighted in blue. All values are expressed as percentages multiplied by 100.

read the caption

Table 2: Trajectory user link (TUL) performance results. A higher value indicates better performance. Red: the best, Blue: the second best. The units of all metics are expressed as e-2.

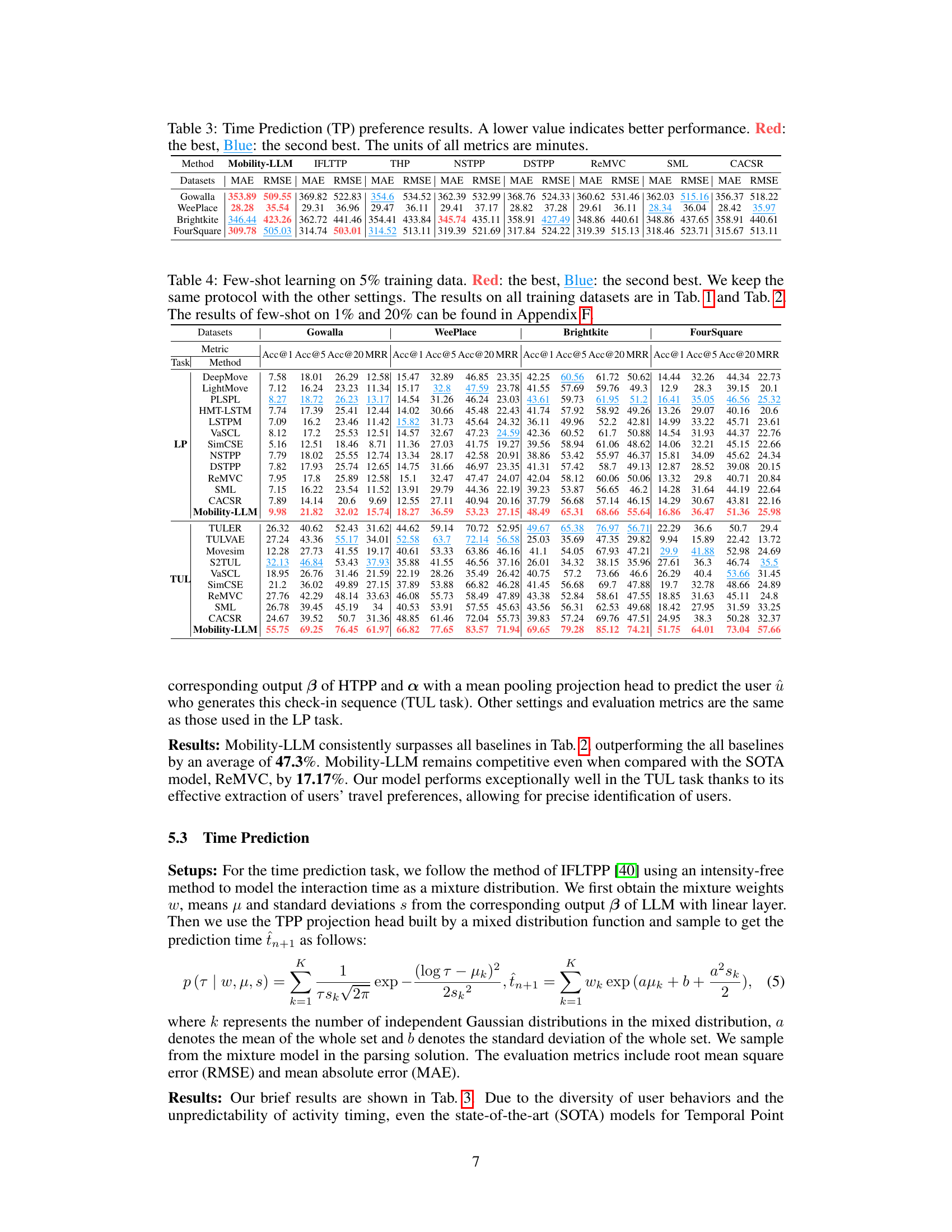

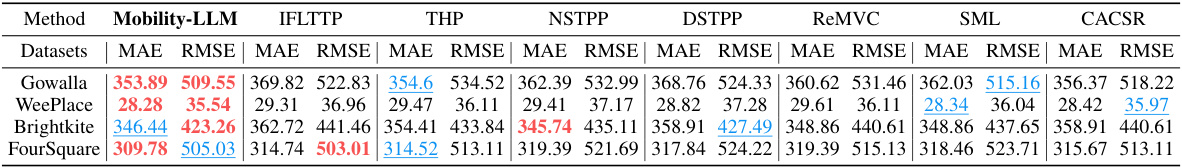

🔼 This table presents the results of the time prediction experiments performed on four benchmark datasets (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and FourSquare). It compares the performance of the proposed Mobility-LLM model against several state-of-the-art baselines (IFLTPP, THP, NSTPP, DSTPP, ReMVC, SML, and CACSR) using two metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). Lower values indicate better performance. The table highlights the best and second-best performing models for each dataset using red and blue coloring, respectively. The units of the metrics are in minutes.

read the caption

Table 3: Time Prediction (TP) preference results. A lower value indicates better performance. Red: the best, Blue: the second best. The units of all metrics are minutes.

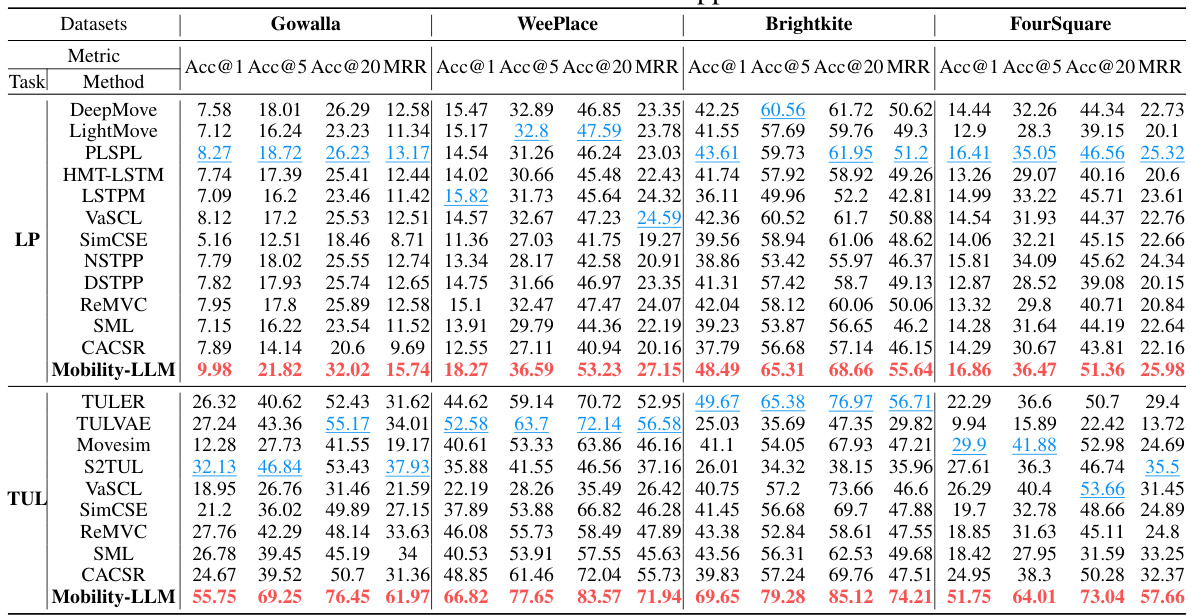

🔼 This table presents the performance of various models on the next location prediction task. It compares the performance of Mobility-LLM against several baselines across four datasets (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and Foursquare). Metrics used include Accuracy@1, Accuracy@5, Accuracy@20, and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). The best and second-best performing models for each metric and dataset are highlighted in red and blue, respectively.

read the caption

Table 1: Next location prediction (LP) performance results. A higher value indicates better performance. Red: the best, Blue: the second best. The units of all metics are expressed as e-2.

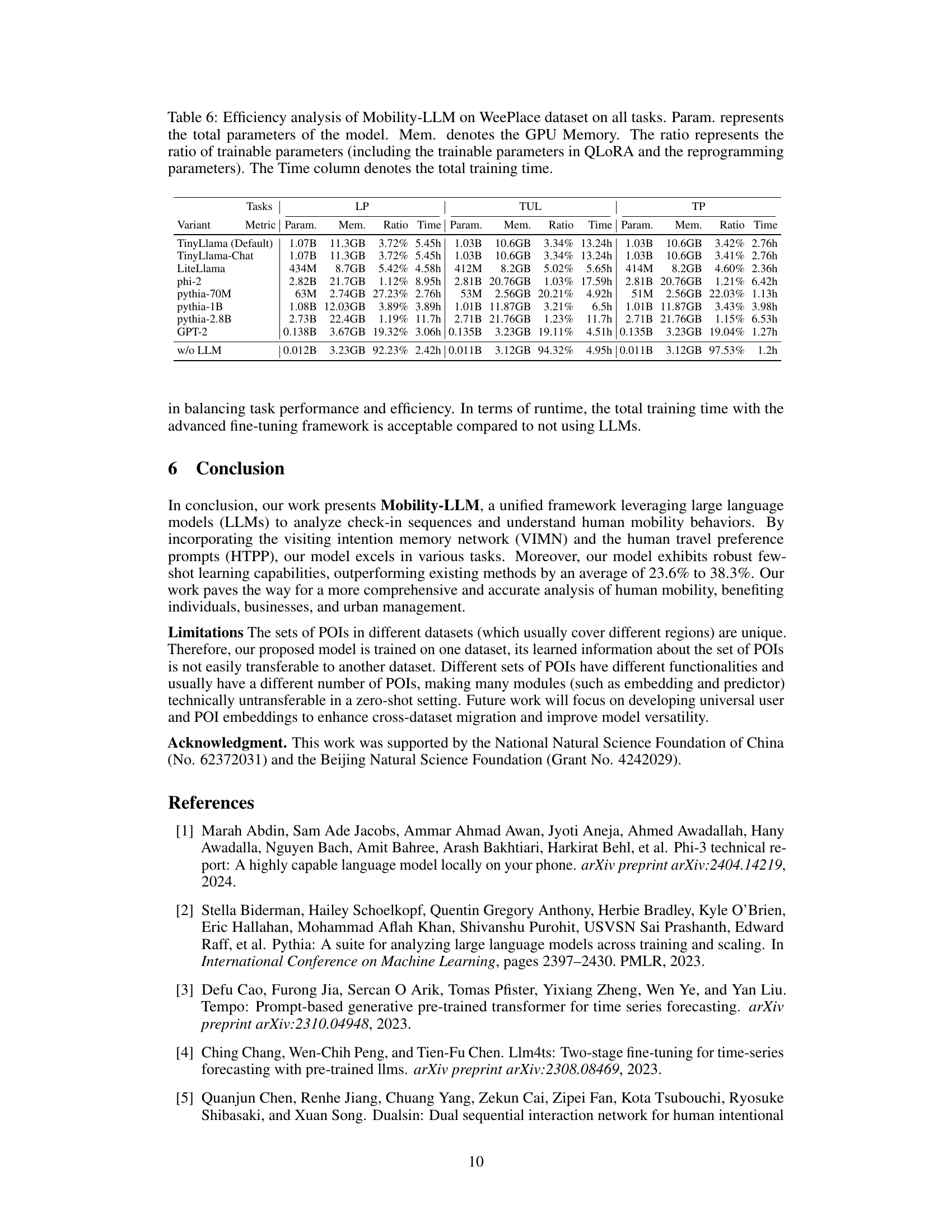

🔼 This table presents a detailed efficiency analysis of the Mobility-LLM model on the WeePlace dataset across three tasks: next location prediction (LP), trajectory user link (TUL), and time prediction (TP). It shows the total number of parameters, GPU memory usage, the percentage of trainable parameters (including QLoRA and reprogramming parameters), and the total training time for various model variants. The table allows for comparison of efficiency across different model choices and configurations. This information is vital for understanding the computational cost and resource requirements of different model setups.

read the caption

Table 6: Efficiency analysis of Mobility-LLM on WeePlace dataset on all tasks. Param. represents the total parameters of the model. Mem. denotes the GPU Memory. The ratio represents the ratio of trainable parameters (including the trainable parameters in QLoRA and the reprogramming parameters). The Time column denotes the total training time.

🔼 This table presents the statistics of four processed datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and Foursquare), it shows the number of samples, users, and points of interest (POIs). This provides context for the scale and characteristics of the data used to train and evaluate the Mobility-LLM model.

read the caption

Table 7: The statics of Processed Datasets

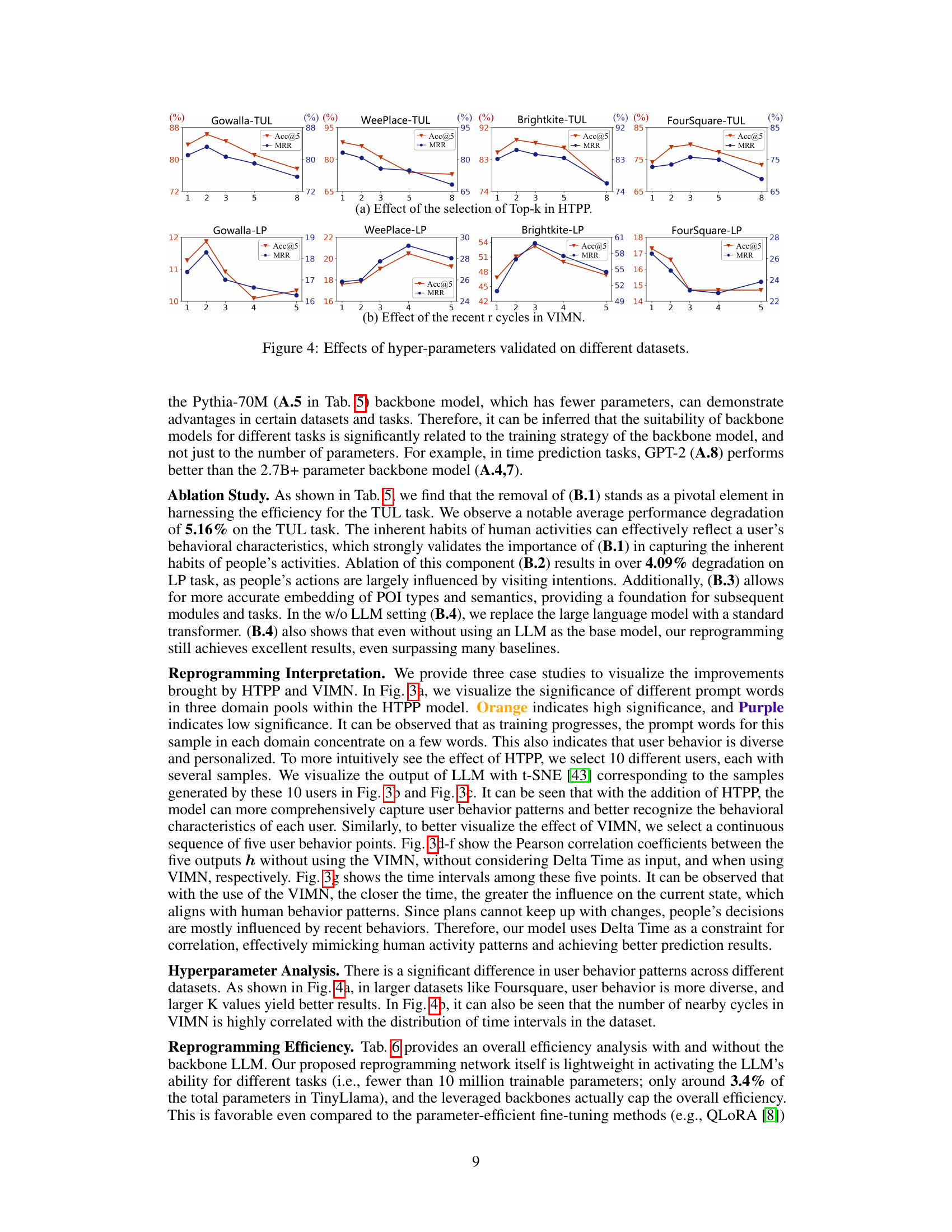

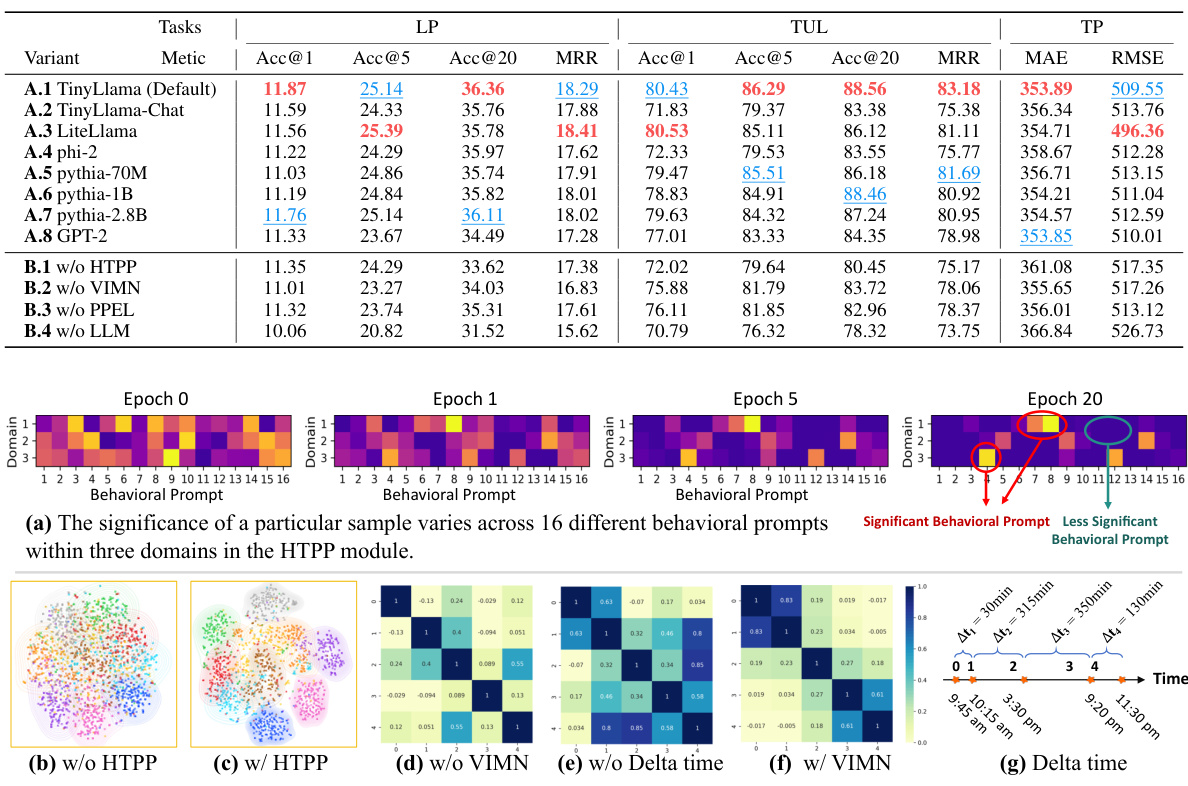

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation experiments conducted on the WeePlace dataset. It shows the performance of the Mobility-LLM model and its variants (removing components like HTPP, VIMN, PPEL, or replacing the LLM with a transformer layer) across three downstream tasks (LP: Next Location Prediction, TUL: Trajectory User Link, TP: Time Prediction). The metrics used are Accuracy at 1, 5, and 20 (Acc@1, Acc@5, Acc@20), Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The best performing variant for each metric in each task is highlighted in red, and the second-best in blue, to show the impact of each model component on the overall performance.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablations on WeePlace dataset in all tasks. Red: the best, Blue: the second-best.

🔼 This table presents the results of next location prediction experiments using various models on four benchmark datasets (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and FourSquare). The metrics used to evaluate performance are Accuracy@1, Accuracy@5, Accuracy@20, and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). Higher scores indicate better prediction accuracy. The table highlights the best and second-best performing models for each dataset and metric.

read the caption

Table 1: Next location prediction (LP) performance results. A higher value indicates better performance. Red: the best, Blue: the second best. The units of all metics are expressed as e-2.

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation experiments performed on the WeePlace dataset. The experiments evaluate the impact of removing key components of the Mobility-LLM model on the performance of three downstream tasks: Next Location Prediction (LP), Trajectory User Link (TUL), and Time Prediction (TP). Each row represents a different model variant, with columns showing the performance metrics for each task. ‘Red’ highlights the best performing variant, and ‘Blue’ highlights the second-best. The table provides insights into the relative contributions of different model components (HTPP, VIMN, PPEL, and the LLM itself) to the overall performance of Mobility-LLM.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablations on WeePlace dataset in all tasks. Red: the best, Blue: the second-best.

🔼 This table presents the results of next location prediction experiments on four datasets (Gowalla, WeePlace, Brightkite, and FourSquare). Multiple models are compared, including several state-of-the-art (SOTA) models and the proposed Mobility-LLM model. The metrics used to evaluate performance are Accuracy at 1 (Acc@1), Accuracy at 5 (Acc@5), Accuracy at 20 (Acc@20), and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR). The best and second-best performing models are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. Results are presented as percentages multiplied by 100 (e-2).

read the caption

Table 1: Next location prediction (LP) performance results. A higher value indicates better performance. Red: the best, Blue: the second best. The units of all metics are expressed as e-2.

Full paper#