TL;DR#

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) show promise in embodied AI, yet effectively translating their linguistic capabilities into real-world actions remains a challenge. The core problem lies in the mismatch between the model’s natural language output and the often complex and continuous/discrete action spaces of robotic systems. Existing methods lack a systematic comparison across various environments and action types.

This research introduces a unified architecture using ‘Action Space Adapters’ (ASAs) to bridge this gap. They systematically evaluate several ASA strategies across five different environments and 114 embodied tasks, exploring both continuous and discrete action spaces. The key findings reveal that a learned tokenization is superior for continuous actions, while semantically aligning discrete actions with the LLM’s native token space yields the best results. These insights provide practical guidelines for designing more effective embodied AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it systematically investigates how to effectively integrate large language models into embodied AI systems. This bridges the gap between the model’s natural language output and the often vastly different action spaces of robots and other agents. The findings directly impact the design and performance of embodied AI, accelerating progress in robotics and related fields.

Visual Insights#

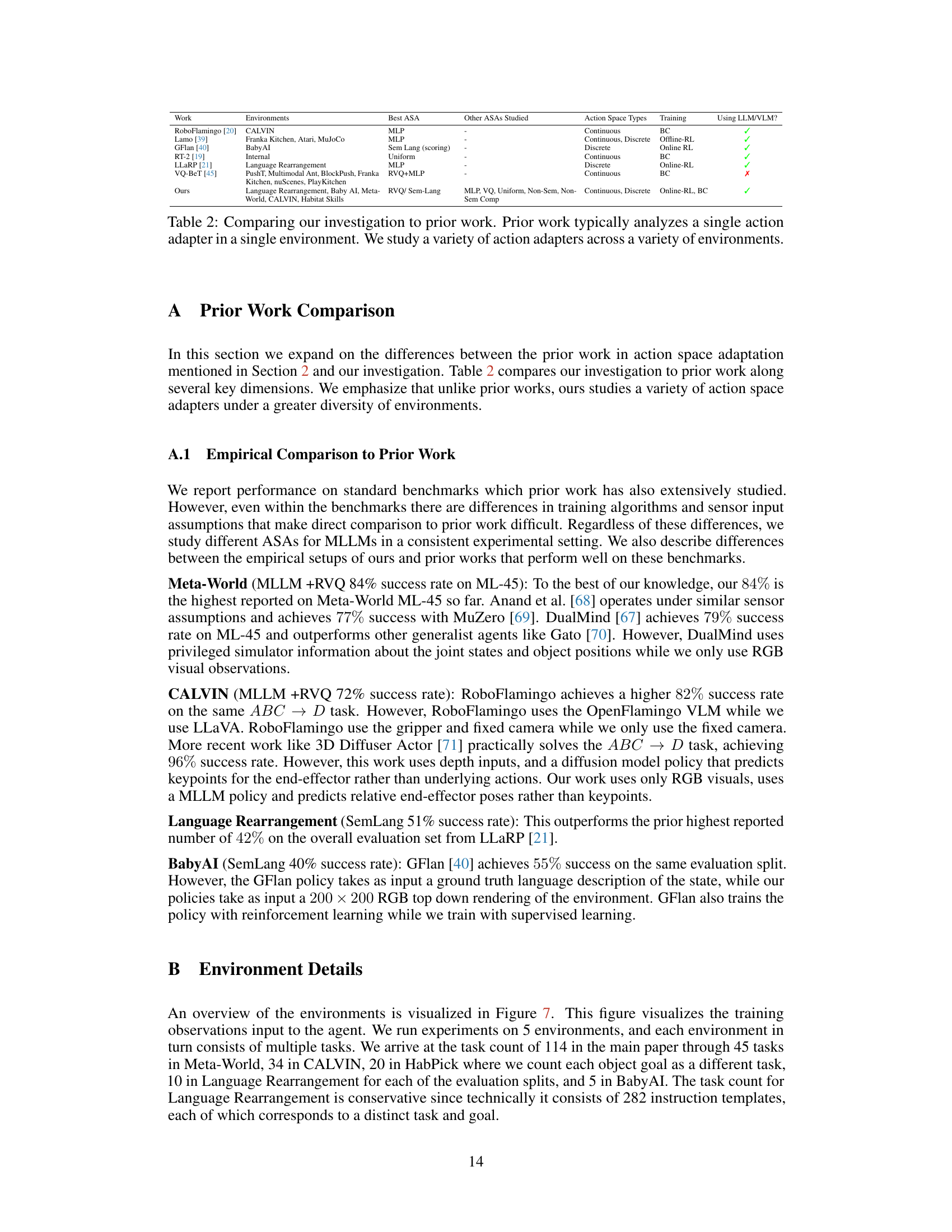

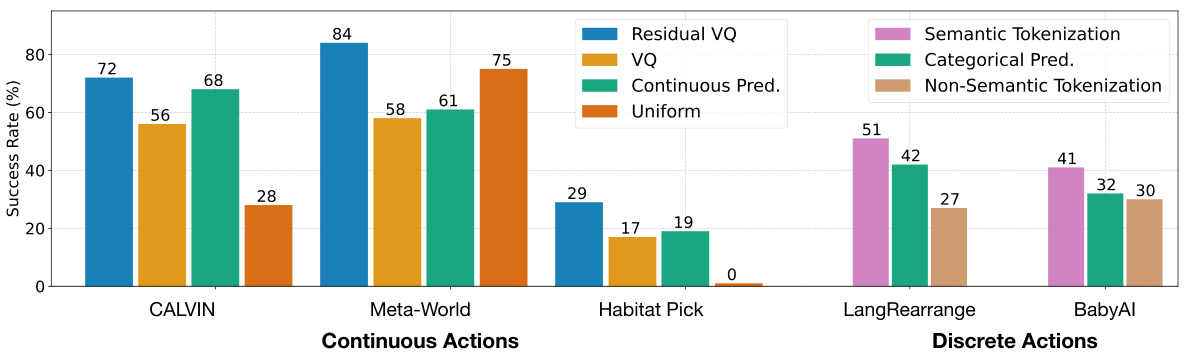

🔼 This figure summarizes the main results of the paper, showing how different methods of grounding Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) into actions perform across various tasks and environments. The figure compares the performance of different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) for both continuous and discrete action spaces. For continuous actions, a learned tokenization method (Residual VQ) showed the best performance, while for discrete actions, semantically aligning actions with the MLLM’s token space yielded superior results (Semantic Tokenization). The figure visually displays the success rates of each ASA on a bar chart, along with example action outputs for both continuous and discrete actions.

read the caption

Figure 1: We empirically analyze how to ground MLLMs in actions across 114 tasks in continuous and discrete action spaces. In each environment, we train a multi-task policy with different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) to re-parameterize the MLLM to output actions. For continuous actions, learning a tokenization with several tokens per-action performs best (Residual VQ). For discrete actions, mapping actions to semantically related language tokens performs best (Semantic Tokenization).

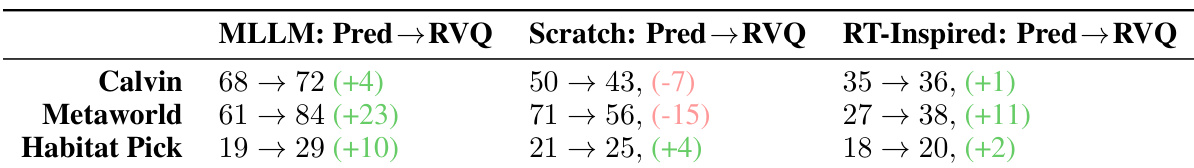

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different policy architectures (MLLM, Scratch, and RT-Inspired) when using either a standard prediction (Pred) or residual vector quantization (RVQ) action space adapter. The results highlight that the benefits of RVQ are specific to MLLMs, improving performance significantly in those models, but causing a decrease in performance for the other, less-complex, architectures. The improvements shown are in terms of the success rate on the CALVIN, MetaWorld, and Habitat Pick tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparing the effect of the RVQ action space adapter on the success rate of non-LLM based policies. Red indicates RVQ hurts over Pred and green indicates RVQ helps over Pred. RVQ typically has a negative impact on the Scratch policy, and helps the smaller RT-Inspired policy.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal grounding#

Multimodal grounding, in the context of large language models (LLMs), focuses on bridging the gap between an LLM’s understanding of the world (represented in text and images) and physical actions in the real world. It tackles the challenge of translating the rich semantic information within multimodal data into effective control signals for robots or other embodied agents. This involves addressing several key aspects, including: action space adaptation, which focuses on mapping the LLM’s output to the specific actions possible by the agent; representation learning, where suitable representations for actions (continuous vs. discrete) are learned and encoded; and policy learning, aiming to train effective policies that direct the agent’s behavior using the LLM’s multimodal understanding. Effective multimodal grounding requires careful consideration of the environment and its dynamics, including the agent’s capabilities and limitations. Ultimately, success in multimodal grounding enables LLMs to transition from passively processing information to actively interacting with the environment, opening possibilities for a wide range of applications in robotics, virtual reality, and more. The research in this area centers on developing efficient and robust methods for translating high-level multimodal input into low-level control, and the development of benchmarks to evaluate the success of these methods.

Action space adaptors#

Action space adaptors represent a crucial bridge between the high-level reasoning capabilities of multimodal large language models (MLLMs) and the low-level control requirements of embodied agents. The core challenge lies in translating the MLLM’s natural language output into actions that are both precise and meaningful for a specific environment. The paper explores various adaptor strategies for both continuous (e.g., robot arm movements) and discrete (e.g., picking up an object) action spaces. Learned tokenization emerges as a superior method for continuous actions, providing a more nuanced control than direct regression. For discrete actions, semantic alignment between MLLM tokens and action semantics proves most effective, enabling better performance and sample efficiency. The unified architectural framework presented facilitates a comprehensive comparative analysis of different adaptor types, thereby offering valuable insights into the design principles of efficient and effective grounding mechanisms for MLLMs in embodied AI applications. Choosing the right adaptor is shown to significantly impact downstream task performance, highlighting the importance of careful consideration for the specific action space and environment.

Tokenization methods#

The effectiveness of grounding multimodal large language models (MLLMs) in action hinges significantly on the choice of tokenization method for representing actions. For continuous action spaces, the paper champions a learned tokenization, particularly residual vector quantization (RVQ), which outperforms direct regression and uniform binning. RVQ’s strength lies in its ability to model fine-grained action nuances through a hierarchical tokenization, capturing both global action trends and subtle variations. In contrast, for discrete actions, the best approach centers on semantic alignment, where actions are mapped to semantically related tokens within the MLLM’s vocabulary. This ensures a smooth transition between the inherent language representation of the MLLM and the robot’s control commands, improving performance. The comparative analysis highlights the importance of aligning tokenization strategies to the nature of the action space, underscoring the need for tailored approaches to maximize the MLLM’s capabilities in embodied AI tasks.

Empirical comparison#

An empirical comparison section in a research paper is crucial for establishing the validity and significance of the findings. It involves a systematic comparison of the proposed method or model against existing state-of-the-art approaches. A strong empirical comparison should focus on relevant benchmarks and datasets, providing detailed results with clear error metrics. The choice of baselines is vital, ensuring that the comparison is fair and meaningful, highlighting the strengths of the proposed work. Statistical significance testing is essential to demonstrate the reliability of the observed improvements, particularly when dealing with noisy or limited data. Ideally, the comparison would show consistent improvements across diverse settings, demonstrating the robustness and generalizability of the proposed approach. Finally, thorough analysis of the results and a discussion of any limitations are necessary to provide a complete and unbiased perspective of the empirical findings. The section should present a balanced and nuanced comparison, providing evidence to support the claims made while also acknowledging potential limitations or alternative interpretations. A strong empirical comparison establishes the novelty and value of a research paper in the field.

Future work#

The paper’s discussion on “Future Work” highlights several promising avenues. Extending the research to encompass a wider array of MLLMs is crucial for generalizing findings beyond LLaVA. Exploring different training regimes, such as full LLM finetuning, is key to understanding the impact on ASA performance. Improving the real-world applicability of these methods is paramount, addressing the performance gap between simulated and real-robot deployments. Investigating alternative learning paradigms, such as off-policy or offline RL, could enhance the efficiency and adaptability of the presented ASAs. Furthermore, a thorough examination of how different action space characteristics influence the optimal ASA design and the exploration of more sophisticated tokenization strategies, potentially involving hierarchical representations, is warranted. Finally, delving deeper into the interplay between tokenization, model architecture, and action space dimensionality would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of grounded MLLM capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

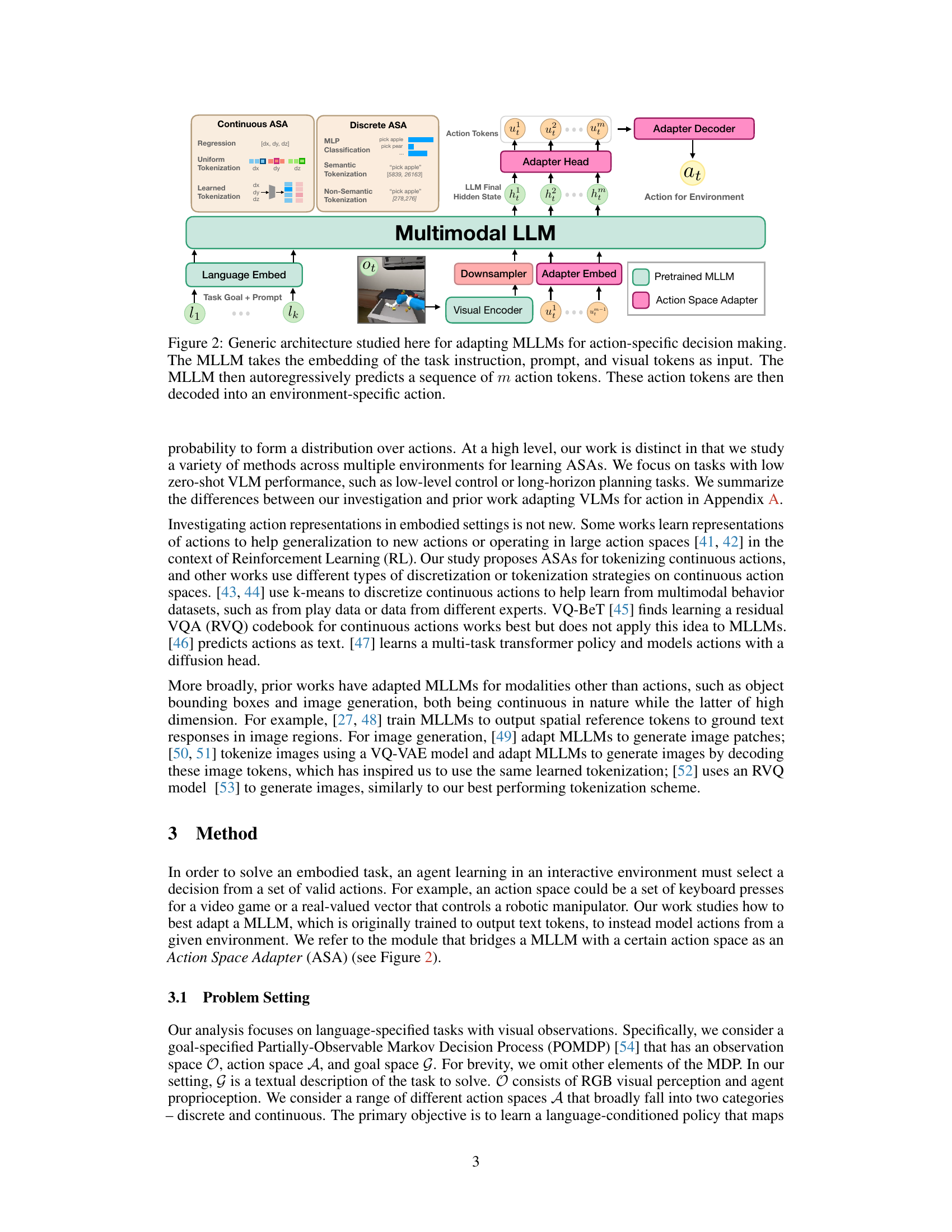

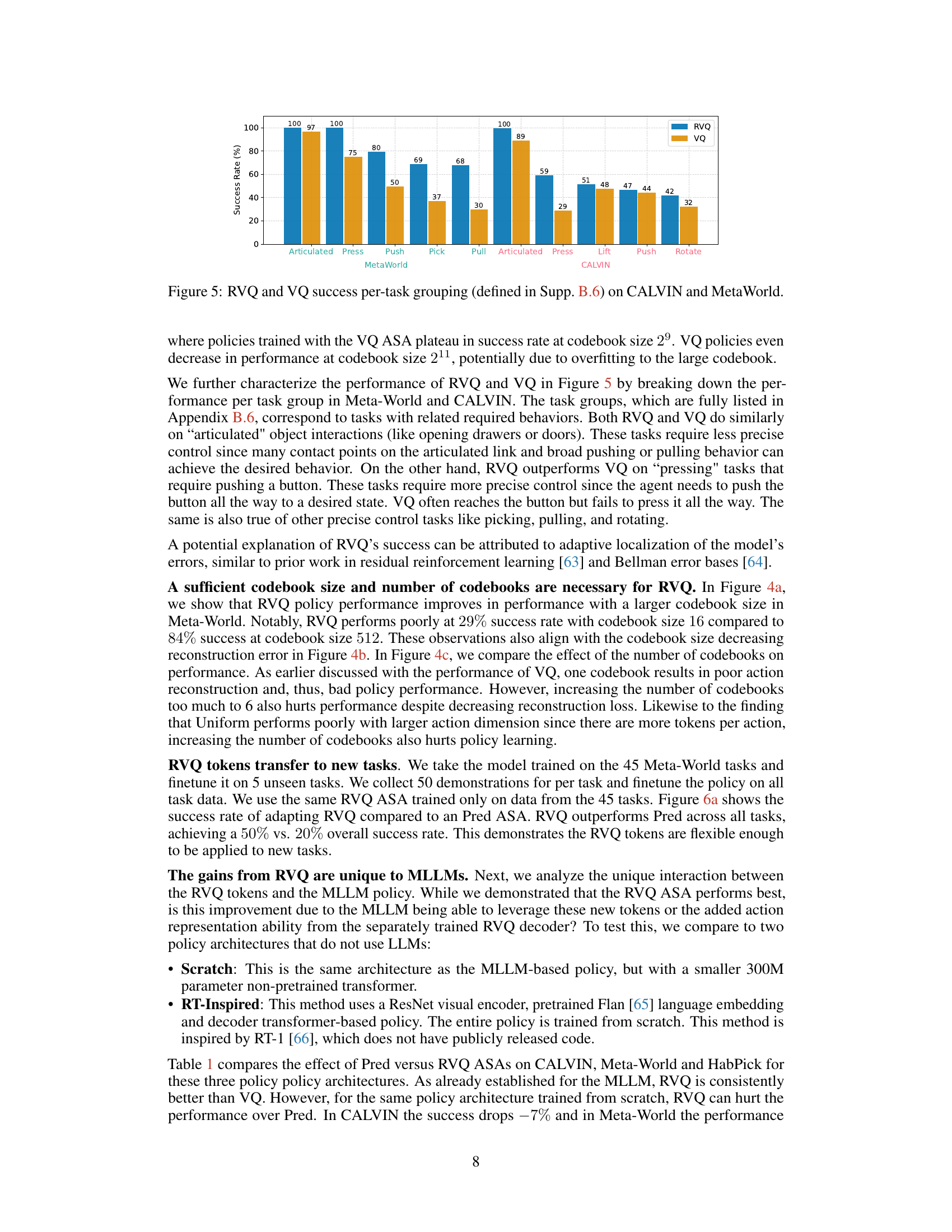

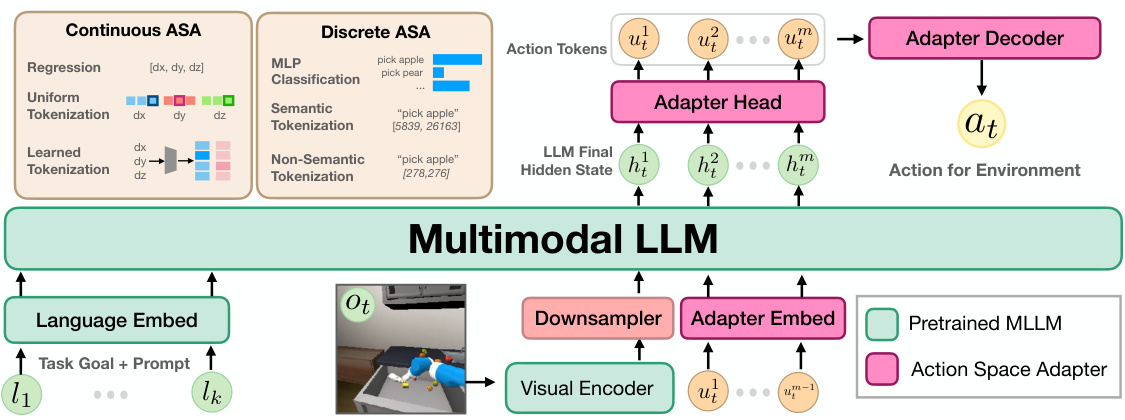

🔼 This figure illustrates the general architecture used to adapt Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for action-specific decision-making. The architecture comprises several key components: 1. Input: The MLLM receives embeddings of the task instruction, a prompt, and visual tokens. The visual tokens are processed by a visual encoder and then downsampled to reduce dimensionality before being fed to the MLLM. 2. MLLM Processing: The MLLM processes these embeddings autoregressively to predict a sequence of m action tokens. 3. Action Space Adapter (ASA): An ASA (the focus of the paper) is employed, consisting of an adapter head, an adapter embedding, and an adapter decoder. The adapter head processes the MLLM’s final hidden state, which are then embedded and passed autoregressively through the MLLM to further refine the action tokens. 4. Action Decoding: Finally, the adapter decoder transforms the sequence of action tokens into an action that can be executed within a specific environment.

read the caption

Figure 2: Generic architecture studied here for adapting MLLMs for action-specific decision making. The MLLM takes the embedding of the task instruction, prompt, and visual tokens as input. The MLLM then autoregressively predicts a sequence of m action tokens. These action tokens are then decoded into an environment-specific action.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) for both continuous and discrete action spaces across five different environments. For continuous control tasks, the Residual Vector Quantized Tokenization (RVQ) method achieved the highest success rate. In contrast, for discrete action tasks, the Semantic Language Tokenization (SemLang) method performed best. The figure shows the average success rate across all tasks within each environment, with a more detailed breakdown provided in Appendix E of the paper. The five environments are CALVIN, Meta-World, Habitat Pick, Language Rearrangement, and BabyAI.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing ASAs for continuous and discrete action spaces across 5 environments. For continuous actions, the RVQ tokenization performs best. For discrete actions, SemLang performs best. Each bar gives the average over all tasks in the environment with the full breakdown in Appendix E.

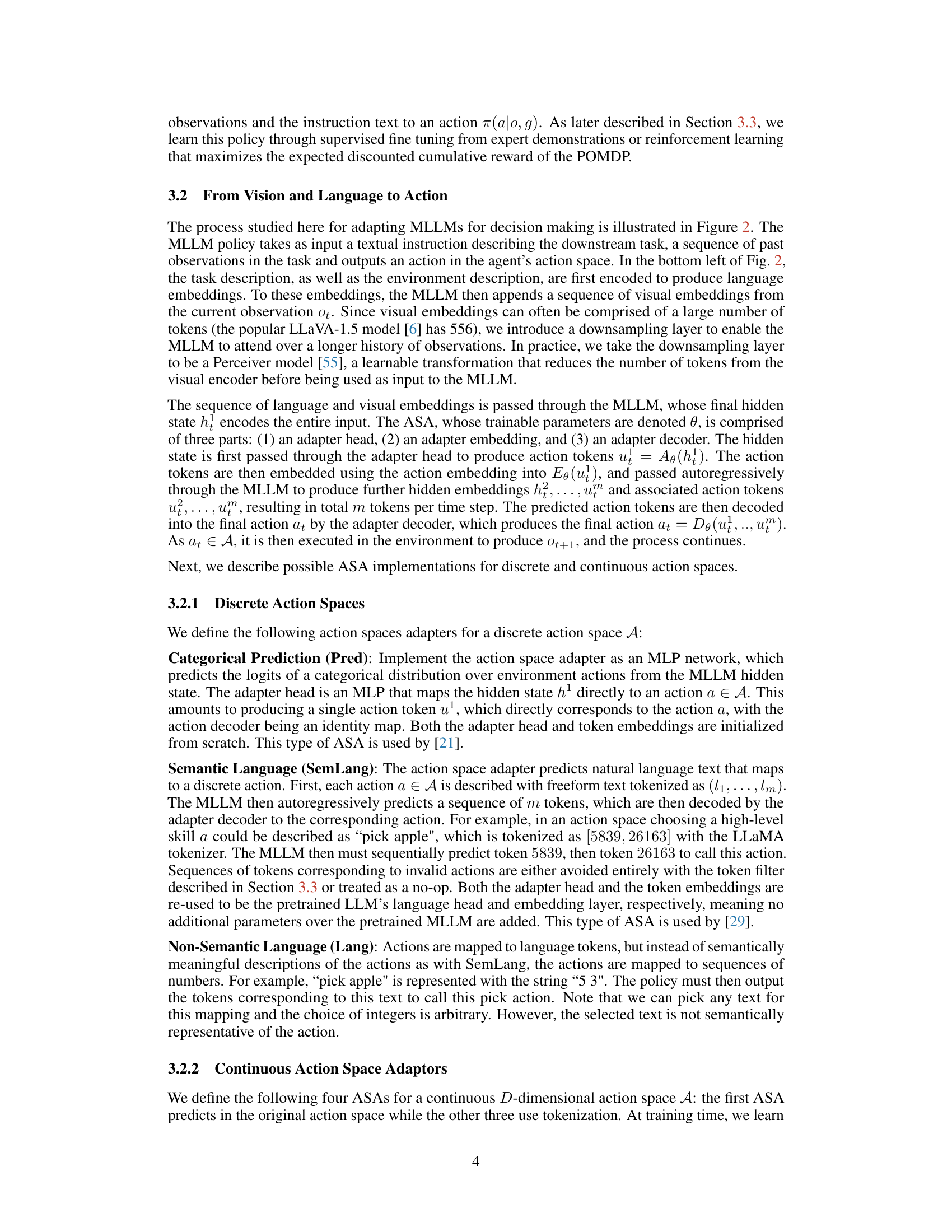

🔼 This figure analyzes the impact of codebook size and the number of codebooks in Residual Vector Quantized (RVQ) and Vector Quantized (VQ) tokenization methods on the success rate and reconstruction error in Meta-World environment. Subfigures (a) and (b) show how changing the codebook size affects success rate and reconstruction loss, respectively, for both RVQ and VQ. Subfigures (c) and (d) demonstrate the effects of varying the number of codebooks used in the RVQ method on both success rate and reconstruction loss. The results highlight the importance of carefully selecting these hyperparameters for optimal performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b) show the effect of the number of codes in the codebook for RVQ and VQ on final policy success rate (see (a)) and reconstruction on unseen action trajectories in Meta-World (see (b)). (c,d) show the effect of number of codebooks on final policy success rate (see (c)) and action reconstruction (see (d)). All metrics are computed on Meta-World.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different action space adapters (ASAs) on continuous and discrete action tasks across five different embodied AI environments. For continuous control tasks, the Residual Vector Quantized (RVQ) tokenization method outperforms other methods. For discrete action tasks, the Semantic Language (SemLang) approach is the most successful. The chart displays the average success rate across all tasks within each environment; a more detailed breakdown can be found in Appendix E of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing ASAs for continuous and discrete action spaces across 5 environments. For continuous actions, the RVQ tokenization performs best. For discrete actions, SemLang performs best. Each bar gives the average over all tasks in the environment with the full breakdown in Appendix E.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) on five different environments, categorized by continuous and discrete action spaces. The results show that Residual Vector Quantized Tokenization (RVQ) is the best-performing ASA for continuous control tasks, while Semantic Language (SemLang) outperforms other ASAs for discrete action tasks. The success rates are averages across all tasks within each environment, with a detailed breakdown provided in Appendix E of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing ASAs for continuous and discrete action spaces across 5 environments. For continuous actions, the RVQ tokenization performs best. For discrete actions, SemLang performs best. Each bar gives the average over all tasks in the environment with the full breakdown in Appendix E.

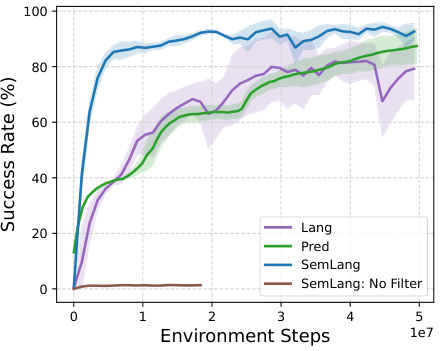

🔼 This figure contains two subfigures. Subfigure (a) shows the result of fine-tuning a model trained on 45 Meta-World tasks to 5 unseen tasks using the RVQ tokenization. It demonstrates the transferability of the learned RVQ tokens to new tasks. Subfigure (b) presents RL training curves for different action space adapters (ASAs) in the Language Rearrangement environment, highlighting the impact of a token filter on SemLang’s performance. It showcases the superior sample efficiency and faster convergence of SemLang with the token filter compared to other ASAs.

read the caption

Figure 6: (a) Adapting to 5 holdout tasks from Meta-World ML-45 with 50 demos per task using the fixed RVQ tokenization. (b) RL training curves in Language Rearrangement comparing the ASAs and utility of the token filter. Displayed are averages over 2 seeds with the shaded area as the standard deviation between seeds. SemLang learns faster than other ASAs and the token filter is crucial.

🔼 This figure summarizes the empirical study on grounding Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) in actions across various environments and action spaces. It compares the performance of different action space adapters (ASAs) for both continuous and discrete action spaces. The key finding is that for continuous control, learning a tokenization scheme (Residual VQ) is superior, while for discrete actions, semantically aligning actions with MLLM’s output tokens (Semantic Tokenization) yields the best results.

read the caption

Figure 1: We empirically analyze how to ground MLLMs in actions across 114 tasks in continuous and discrete action spaces. In each environment, we train a multi-task policy with different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) to re-parameterize the MLLM to output actions. For continuous actions, learning a tokenization with several tokens per-action performs best (Residual VQ). For discrete actions, mapping actions to semantically related language tokens performs best (Semantic Tokenization).

🔼 This figure summarizes the empirical analysis of grounding Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) in actions across various tasks with continuous and discrete action spaces. It shows different environments (CALVIN, Meta-World, BabyAI, Habitat, LangR) used for the experiments and compares the success rate of different Action Space Adapters (ASAs). The ASAs re-parameterize the MLLM output to produce actions, and the figure highlights that for continuous actions, a learned tokenization (Residual VQ) is best; while for discrete actions, semantic alignment (Semantic Tokenization) is superior.

read the caption

Figure 1: We empirically analyze how to ground MLLMs in actions across 114 tasks in continuous and discrete action spaces. In each environment, we train a multi-task policy with different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) to re-parameterize the MLLM to output actions. For continuous actions, learning a tokenization with several tokens per-action performs best (Residual VQ). For discrete actions, mapping actions to semantically related language tokens performs best (Semantic Tokenization).

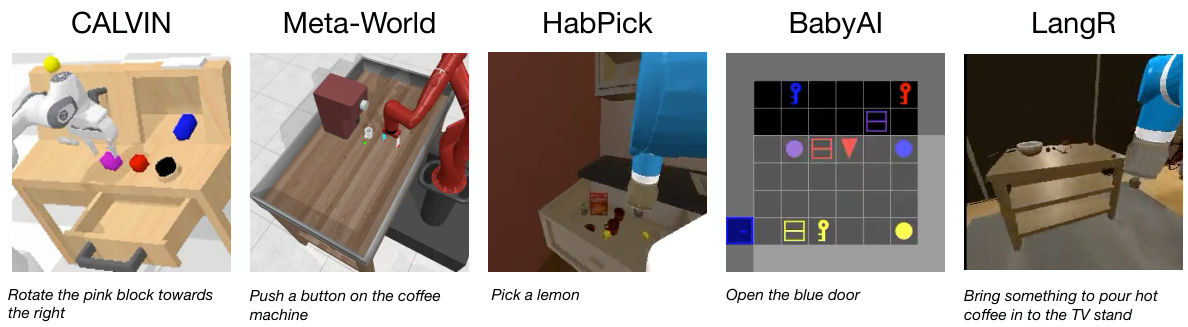

🔼 This figure shows five different robotic manipulation environments used in the paper: CALVIN, Meta-World, Habitat Pick, BabyAI, and LangR. For each environment, the top row displays a visual observation from the robot’s perspective during task execution. The bottom row provides the corresponding natural language instruction given to the robot to guide its actions in that specific episode.

read the caption

Figure 7: Visualizations of the environments we study. The top row shows an observation in the environment. The bottom row shows the associated instruction in that episode.

🔼 This figure shows five different robotic manipulation environments used in the paper’s experiments. Each environment’s image is accompanied by a sample instruction task given to the robot. The figure aims to visually illustrate the variety of tasks and visual inputs the model processes.

read the caption

Figure 7: Visualizations of the environments we study. The top row shows an observation in the environment. The bottom row shows the associated instruction in that episode.

🔼 This figure summarizes the main results of the paper by showing the success rate of different action space adapters (ASAs) for grounding multimodal large language models (MLLMs) in actions. The figure compares the performance of various ASAs on continuous and discrete action spaces across multiple environments and tasks. The key finding is that for continuous actions, learning a tokenization (Residual VQ) is best, and for discrete actions, aligning actions semantically with the MLLM’s output (Semantic Tokenization) is best.

read the caption

Figure 1: We empirically analyze how to ground MLLMs in actions across 114 tasks in continuous and discrete action spaces. In each environment, we train a multi-task policy with different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) to re-parameterize the MLLM to output actions. For continuous actions, learning a tokenization with several tokens per-action performs best (Residual VQ). For discrete actions, mapping actions to semantically related language tokens performs best (Semantic Tokenization).

🔼 This figure summarizes the empirical analysis of grounding Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) in actions across various tasks. It compares the performance of different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) for both continuous and discrete action spaces. The results show that for continuous actions, a learned tokenization method (Residual VQ) outperforms other methods, while for discrete actions, aligning actions with the MLLM’s native token space semantically achieves the best performance. The figure illustrates this comparison across multiple environments and tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: We empirically analyze how to ground MLLMs in actions across 114 tasks in continuous and discrete action spaces. In each environment, we train a multi-task policy with different Action Space Adapters (ASAs) to re-parameterize the MLLM to output actions. For continuous actions, learning a tokenization with several tokens per-action performs best (Residual VQ). For discrete actions, mapping actions to semantically related language tokens performs best (Semantic Tokenization).

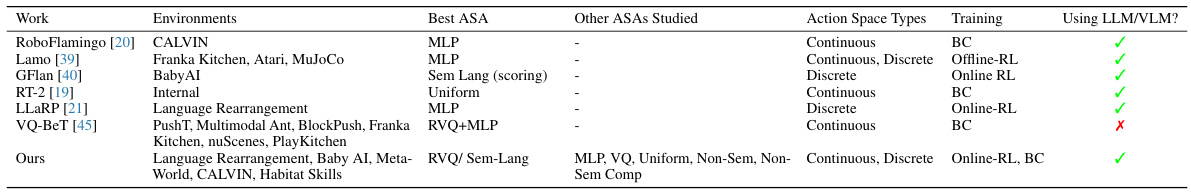

More on tables

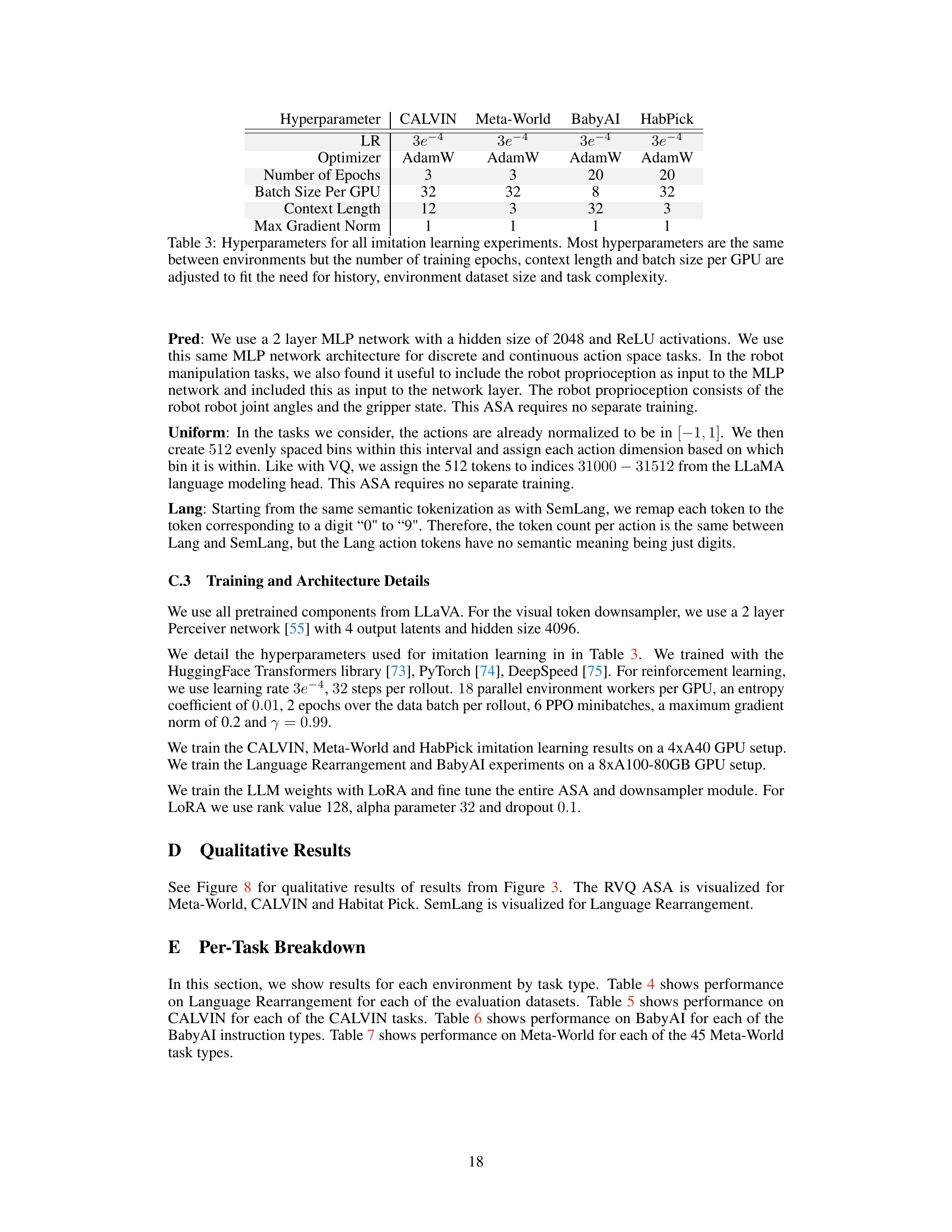

🔼 This table compares the authors’ work to previous research on adapting large language models (LLMs) for embodied tasks. It highlights that prior works often focused on a single action space adapter within a limited set of environments, whereas the authors’ work took a broader approach by evaluating multiple adapters across five different environments, encompassing 114 tasks. The table provides a summary of the different works, their methods, action space types, and whether they leveraged LLMs. This comparison underscores the comprehensive and systematic nature of the authors’ investigation.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparing our investigation to prior work. Prior work typically analyzes a single action adapter in a single environment. We study a variety of action adapters across a variety of environments.

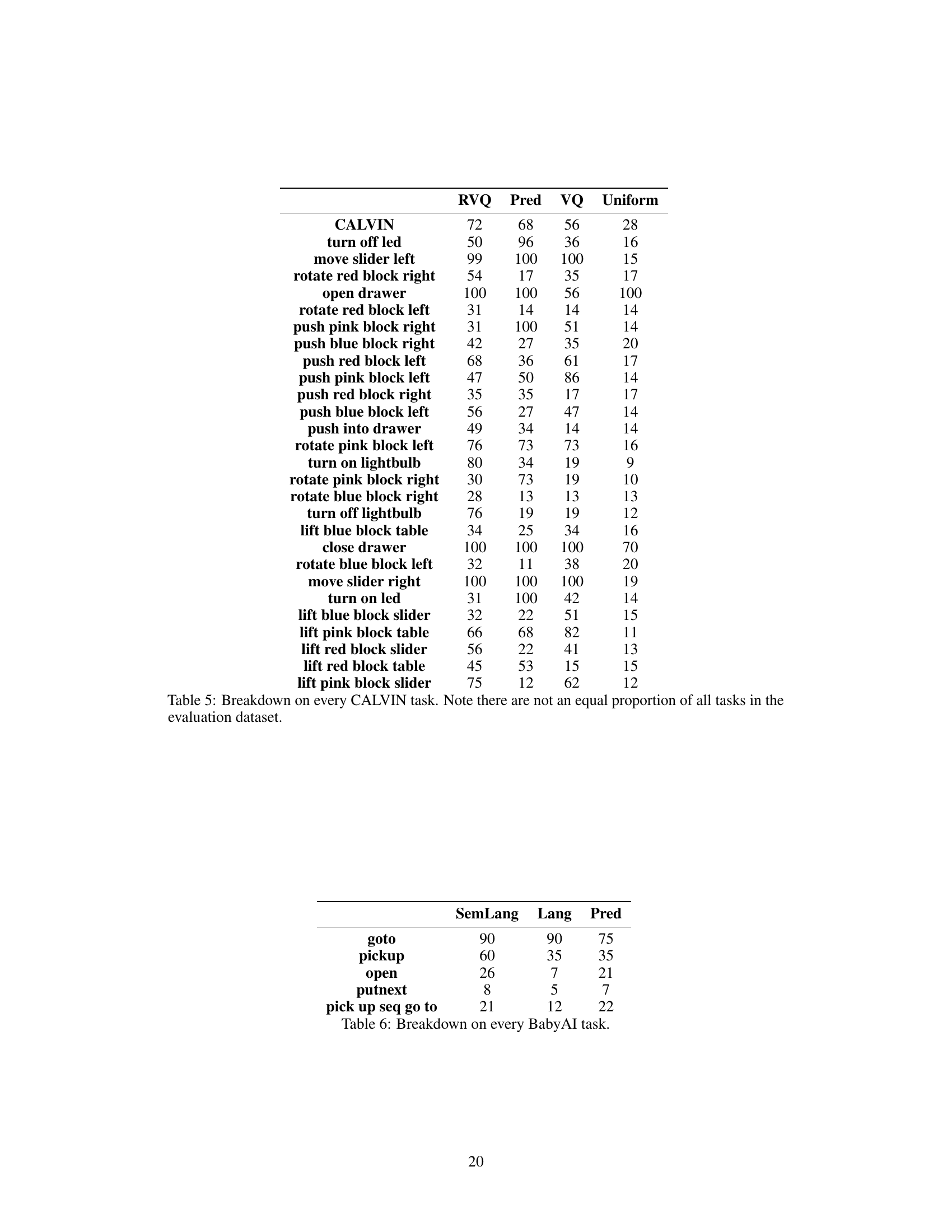

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used in the imitation learning experiments across different environments. While most parameters remain consistent, adjustments were made to training epochs, context length, and batch size per GPU to accommodate variations in data size, task complexity, and historical requirements.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameters for all imitation learning experiments. Most hyperparameters are the same between environments but the number of training epochs, context length and batch size per GPU are adjusted to fit the need for history, environment dataset size and task complexity.

🔼 This table presents the performance of three different action space adapters (SemLang, Lang, Pred) on the Language Rearrangement task after 20 million reinforcement learning steps. The results are broken down by various task aspects, including overall success rate and performance across different instruction types (paraphrastic robustness, novel objects, multiple objects, etc.). The table shows average success rates and standard deviations across two random training seeds, offering insights into the generalization capability and sample efficiency of each action space adapter.

read the caption

Table 4: Evaluation results at 20M steps of RL training for all results in Language Rearrangement. We show averages and standard deviations over 2 random seeds of full policy training.

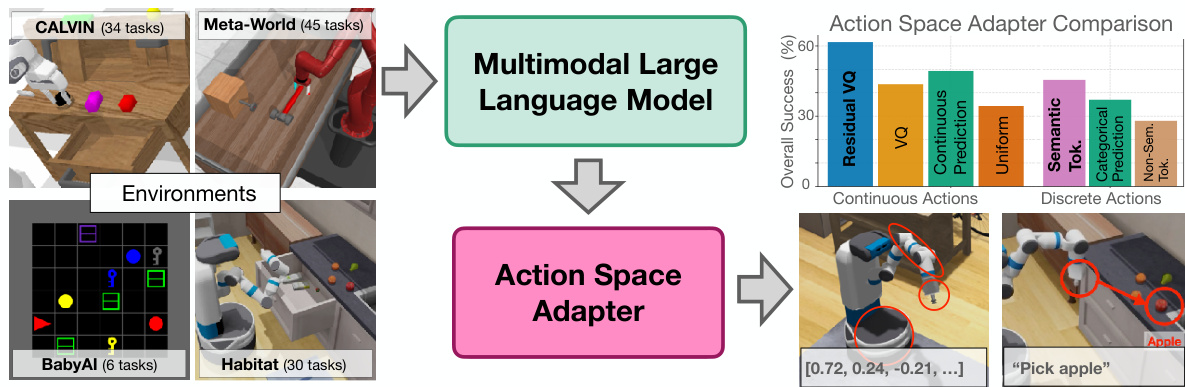

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of different action space adapters (RVQ, Pred, VQ, Uniform) on each individual task within the CALVIN benchmark. It shows the success rate (%) achieved by each adapter on each task. The note highlights that the distribution of tasks in the evaluation dataset is not perfectly uniform, meaning some task types are represented more often than others.

read the caption

Table 5: Breakdown on every CALVIN task. Note there are not an equal proportion of all tasks in the evaluation dataset.

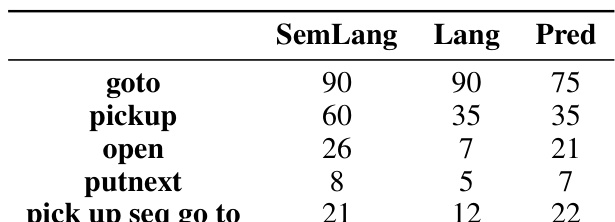

🔼 This table presents a performance breakdown for different action space adapters (SemLang, Lang, Pred) on various tasks within the BabyAI environment. Each row represents a distinct task type (e.g., ‘goto’, ‘pickup’, ‘open’), and the columns show the success rate for each of the three adapters. The results quantify the effectiveness of each action space adaptation method in tackling different types of tasks in the BabyAI environment.

read the caption

Table 6: Breakdown on every BabyAI task.

🔼 This table presents the success rate of different action space adapters (ASA) for each of the 45 tasks in the Meta-World environment. The ASAs compared are Residual Vector Quantized Tokenization (RVQ), Regression (Pred), Vector Quantized Tokenization (VQ), and Uniform. The success rate is shown for each ASA and each task, allowing for a detailed comparison of their performance across a variety of tasks and difficulty levels.

read the caption

Table 7: Breakdown on every Meta-World task.

Full paper#