TL;DR#

Deep neural networks often exhibit a phenomenon called neural collapse, where the final layer’s structure simplifies during training. Recent research has investigated whether this “collapse” extends to earlier layers (deep neural collapse), and under what conditions it represents an optimal solution. However, existing work often simplifies the problem, considering linear models or only two layers. This paper investigates the general case of non-linear models with many layers and classes.

This study reveals a surprising result: deep neural collapse is not optimal in the general case. The authors demonstrate this by identifying a “low-rank bias” in multi-layer regularization, which favors solutions with even lower rank than those produced by neural collapse. They support their theoretical analysis with experiments on synthetic data and real-world datasets, showing that low-rank structures emerge in solutions found by gradient descent. This work significantly advances our understanding of deep neural network training and learned representations, suggesting that the search for optimal structures is more complex than previously thought.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the prevailing assumption of deep neural collapse optimality, revealing a low-rank bias that leads to even more efficient solutions. This finding significantly impacts the understanding of deep learning dynamics and opens new avenues for improving model efficiency and generalization. It also prompts a re-evaluation of existing theoretical frameworks and inspires further investigation into the interplay between optimization biases and model structure.

Visual Insights#

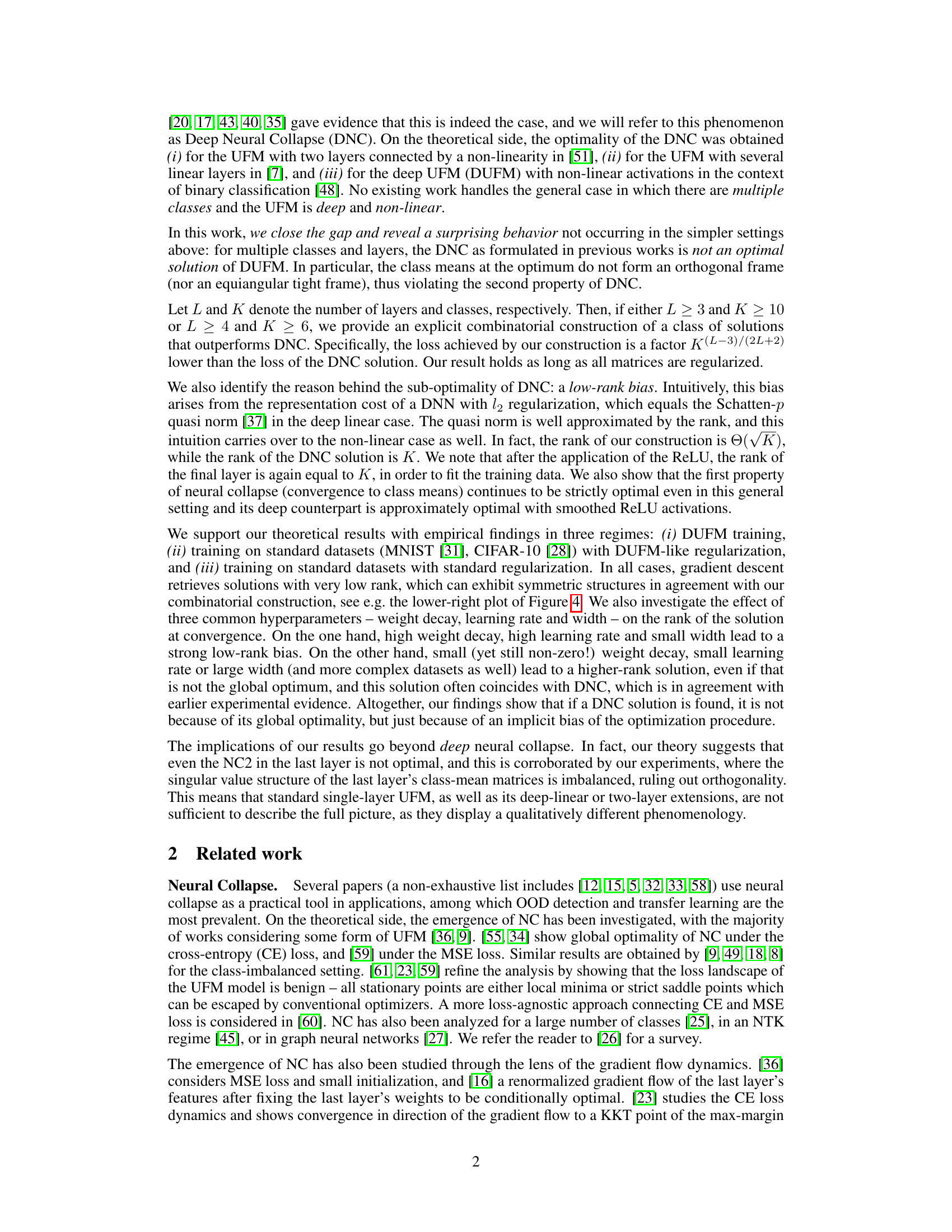

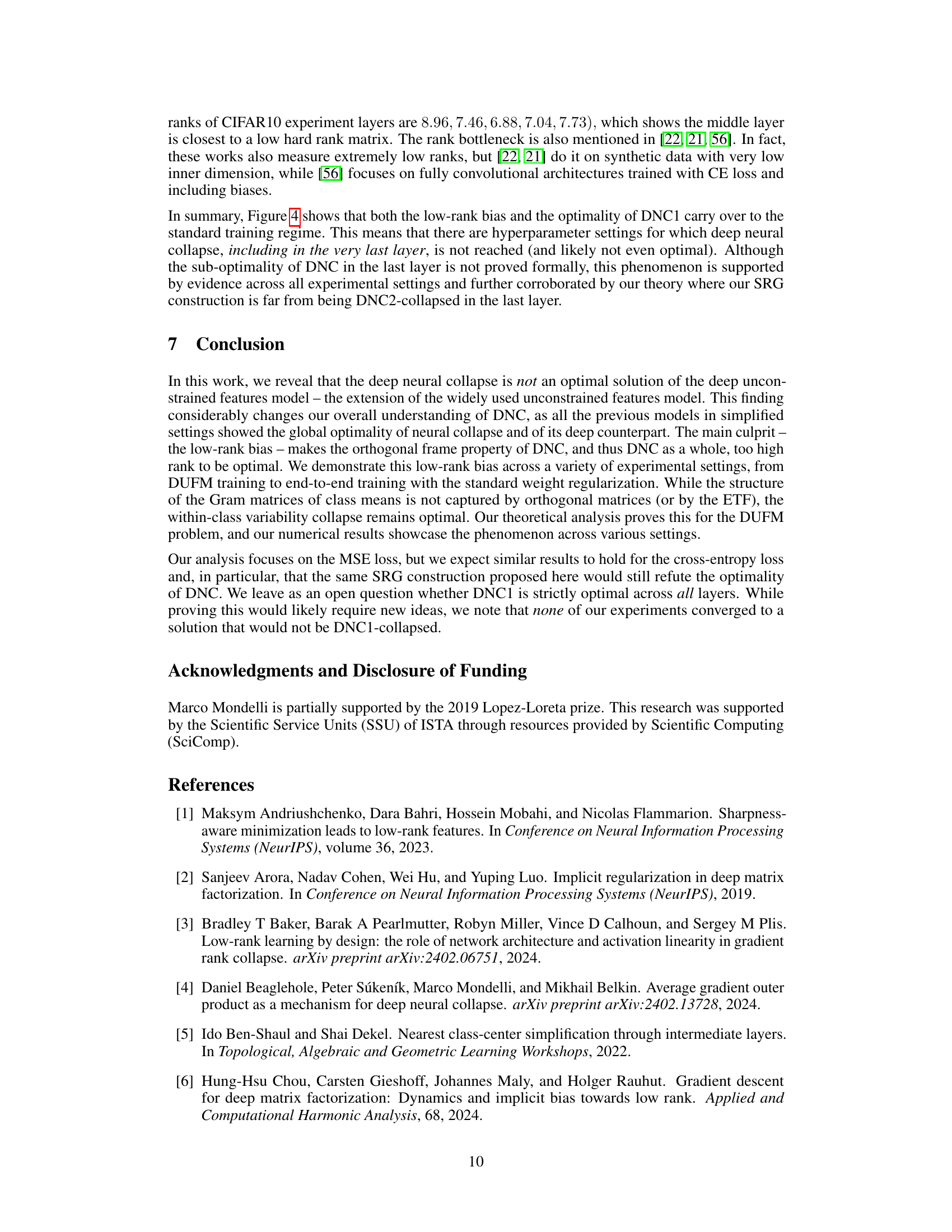

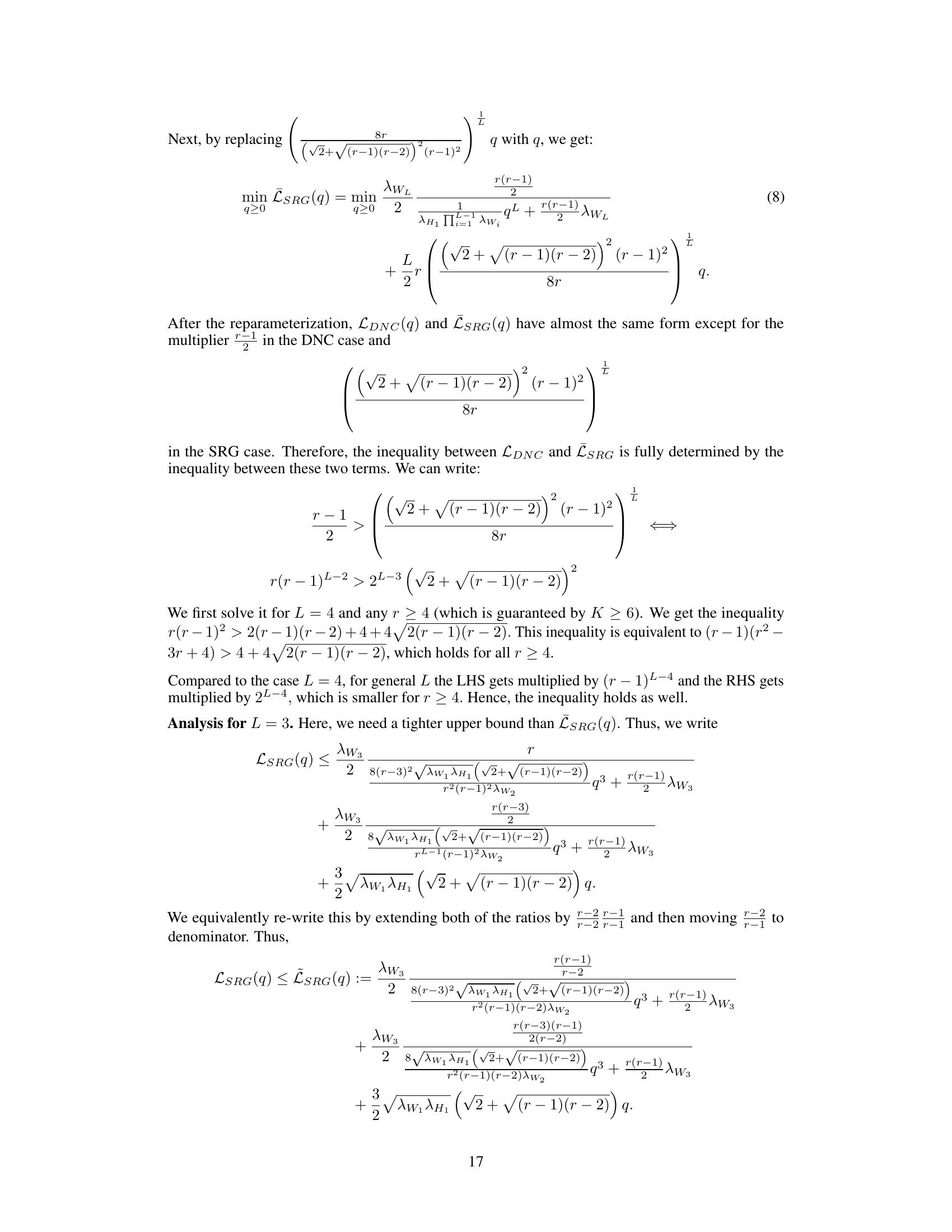

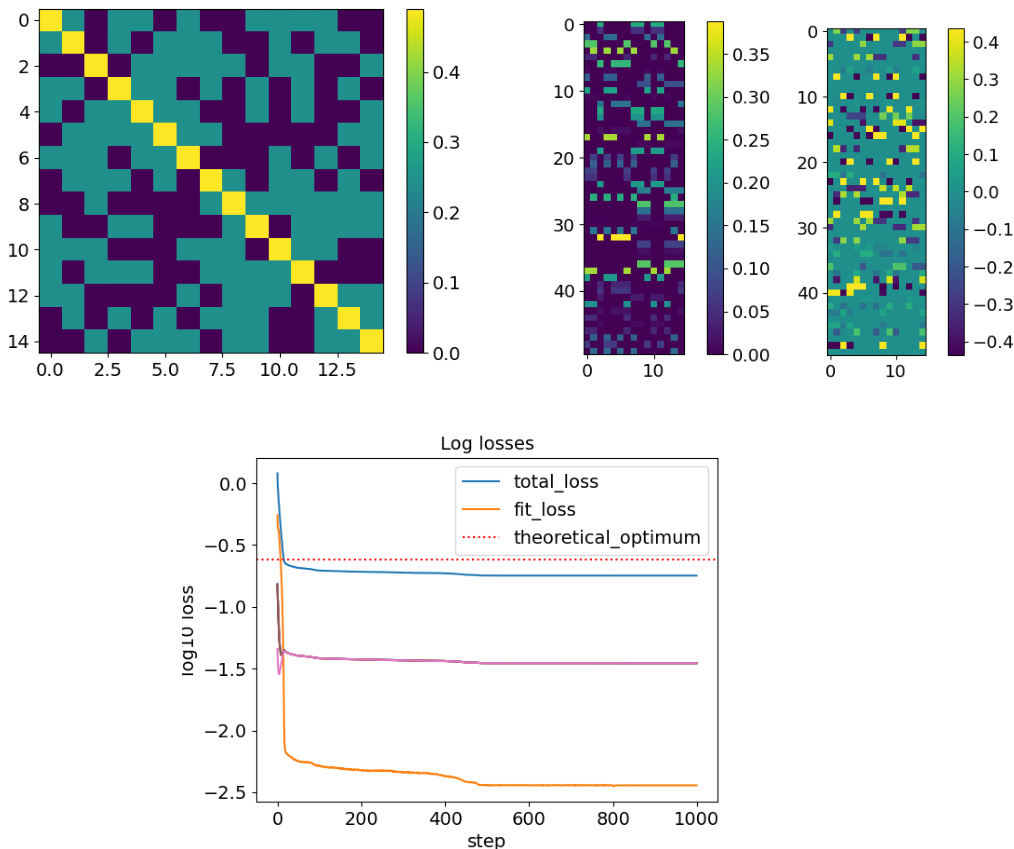

🔼 This figure shows a comparison between a strongly regular graph (SRG) solution and a deep neural collapse (DNC) solution for a 4-layer deep unconstrained features model (DUFM) with 10 classes. The left panel displays the class-mean matrix of the third layer (M3) for the SRG solution, highlighting its low rank (non-zero entries in each row are same, and their number is r-1). The middle panels show the class-mean matrix before ReLU application (M4) and its Gram matrix (MTM4) for the SRG solution, demonstrating its low rank before ReLU (rank(M4)=r, rank(σ(M4))=K). The right panel shows MTM4 for the DNC solution, which has full rank (K) in all layers.

read the caption

Figure 1: Strongly regular graph (SRG) solution with L = 4, K = 10 and r = 5. Left: Class-mean matrix of the third layer M3. The non-zero entries of each row have the same value and their number is r − 1, which corresponds to the degree of the complete graph Kr. Middle: Class-mean matrix of the fourth layer before ReLU M4 (middle left), and its Gram matrix MTM4 (middle right). The SRG construction has very low rank before ReLU: rank(M4) = r and rank(σ(M4)) = K. Right: MTM4 for DNC. The DNC solution has rank K in all layers before and after ReLU.

In-depth insights#

Deep DNC Limits#

The heading ‘Deep DNC Limits’ suggests an exploration of the boundaries and constraints of Deep Neural Collapse (DNC). A thoughtful analysis would likely investigate scenarios where DNC’s optimality breaks down. This could involve exploring the impact of network architecture (depth, width, type of layers), data characteristics (number of classes, dimensionality, data distribution), and optimization methods (choice of optimizer, learning rate, regularization). High-dimensional datasets or complex architectures might reveal limitations in DNC’s ability to achieve global optimality. The analysis might also explore the emergence of low-rank solutions and their relationship to DNC, potentially showing that low-rank solutions can outperform DNC under specific circumstances. The role of regularization would be crucial, examining how different regularization schemes bias the network towards or away from DNC. Ultimately, a comprehensive study of ‘Deep DNC Limits’ would provide a nuanced understanding of when and why DNC is (or is not) a beneficial phenomenon, enhancing our theoretical understanding of deep learning convergence.

Low-Rank Bias#

The concept of ‘Low-Rank Bias’ in the context of deep neural networks (DNNs) is a crucial observation. It highlights that the optimization process, particularly gradient descent, inherently favors solutions with lower rank than what might be expected. This is not simply a consequence of regularization, but a deeper characteristic of the training dynamics. The paper demonstrates that this bias can lead to solutions with ranks significantly lower than those predicted by neural collapse (NC) theory, especially in models with multiple layers and classes. The low-rank bias is attributed to the representation cost of DNNs, where the complexity is related to the rank of feature matrices. This implies that simpler, lower-rank representations are preferred during optimization even if they don’t fully satisfy the conditions of neural collapse. The emergence of the low-rank bias challenges the assumption of optimality of neural collapse in practical DNN training, and reveals that the observed properties of NC might be a consequence of this implicit bias rather than a fundamental characteristic of optimal solutions.

SRG Solutions#

The section on ‘SRG Solutions’ presents a novel, low-rank alternative to Deep Neural Collapse (DNC) for deep neural networks. The core idea is to leverage the structure of strongly regular graphs (SRGs) to construct weight matrices and feature representations with significantly lower rank than those found in DNC. This low-rank property is key to outperforming DNC in terms of the objective function, specifically when dealing with many classes or layers. The authors provide an explicit combinatorial construction of such low-rank solutions, demonstrating that these solutions have a rank of Θ(√K) compared to DNC’s rank of K (K being the number of classes). This lower rank is achieved by carefully controlling the structure of the class-mean matrices, ensuring they satisfy certain orthogonality and symmetry conditions. The effectiveness of this method is supported by both theoretical analysis and empirical results, showing that gradient descent can indeed discover these low-rank solutions under specific conditions. The success of the SRG approach challenges the notion of DNC as the optimal solution, highlighting the influence of low-rank bias in the training process. The findings suggest that commonly observed low-rank phenomena in DNNs may not be simply explained by DNC, but rather are driven by more fundamental optimization biases in multi-layer models. Further research is needed to determine the full implications of these discoveries for our understanding of DNN behavior.

DNC1 Optimality#

The paper investigates the optimality of Deep Neural Collapse (DNC), specifically focusing on DNC1, which is the phenomenon where feature vectors of the same class collapse to their class mean. While previous research established DNC optimality in simplified settings (e.g., linear models, binary classification), this work demonstrates that DNC1 optimality doesn’t extend to the general multi-class, non-linear, deep learning setting. The authors find that multi-layer regularization schemes introduce a low-rank bias, leading to solutions of even lower rank than those predicted by DNC1. This suggests that DNC1, although empirically observed, is not necessarily the globally optimal solution in complex DNNs. The study highlights the importance of considering low-rank bias when analyzing the geometric structure of learned representations in deep networks. The authors’ theoretical findings are supported by experiments on both synthetic (DUFM) and real datasets, showing that low-rank solutions consistently outperform DNC, particularly as the number of classes and layers increase.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to other loss functions, beyond MSE, is crucial to understand the generality of the low-rank bias phenomenon and its interaction with neural collapse. Investigating the impact of different network architectures is also important, as the current analysis focuses primarily on a specific model. Exploring the relationship between low-rank bias, optimization algorithms, and generalization capabilities offers significant potential for advancing our understanding of deep learning. Empirical studies with a wider range of datasets and hyperparameter settings could further validate and refine the theoretical findings. Finally, developing practical methods to leverage the low-rank bias for improved model efficiency and performance would be a highly valuable contribution.

More visual insights#

More on figures

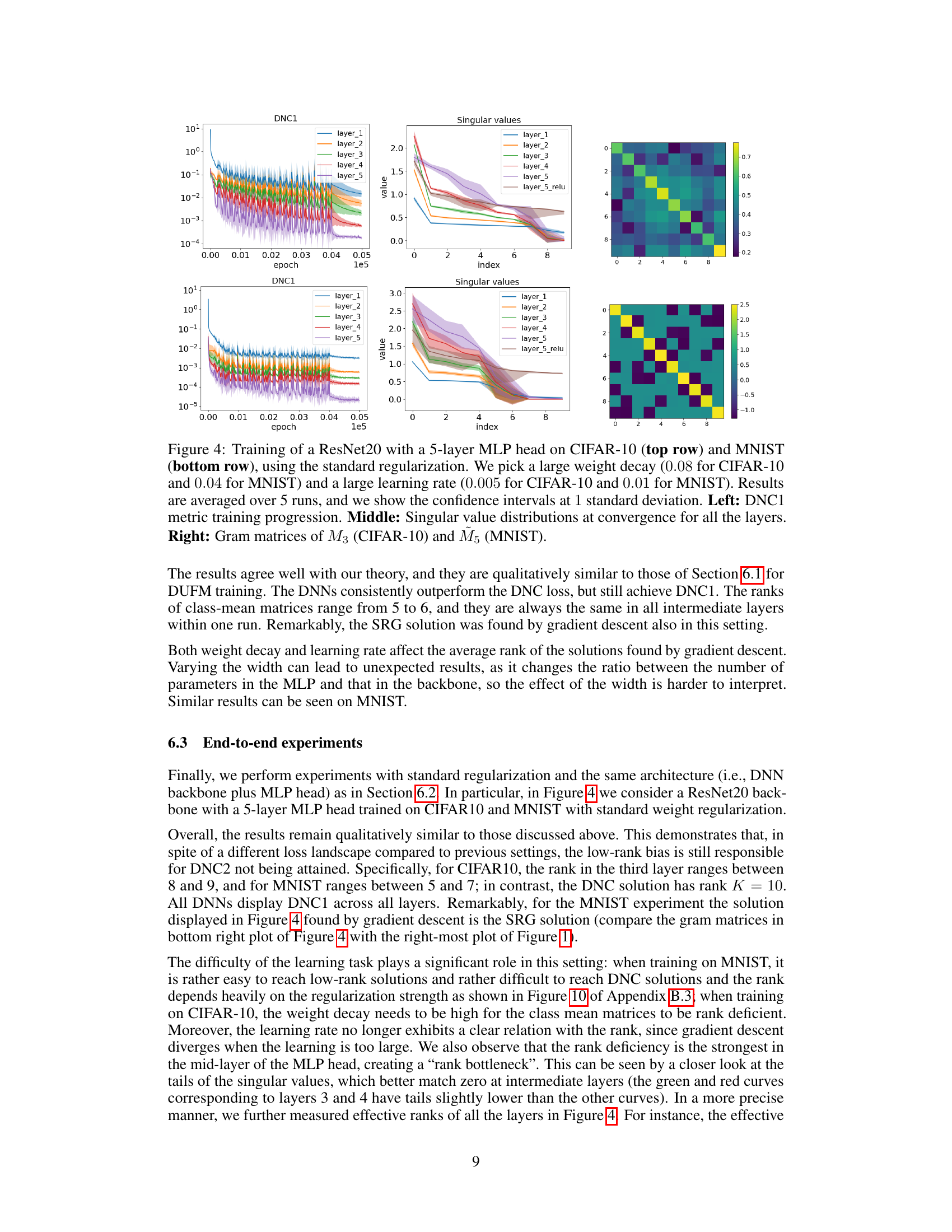

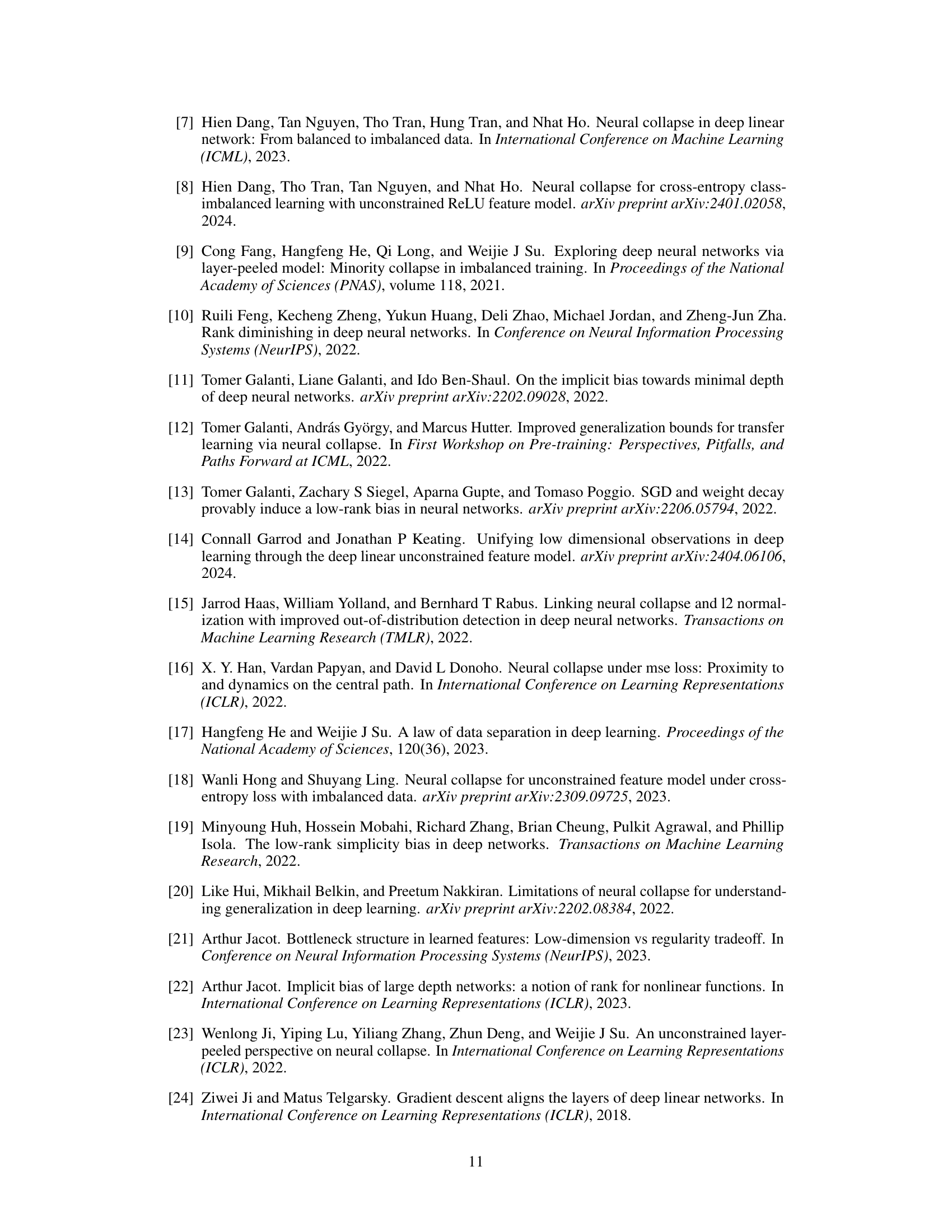

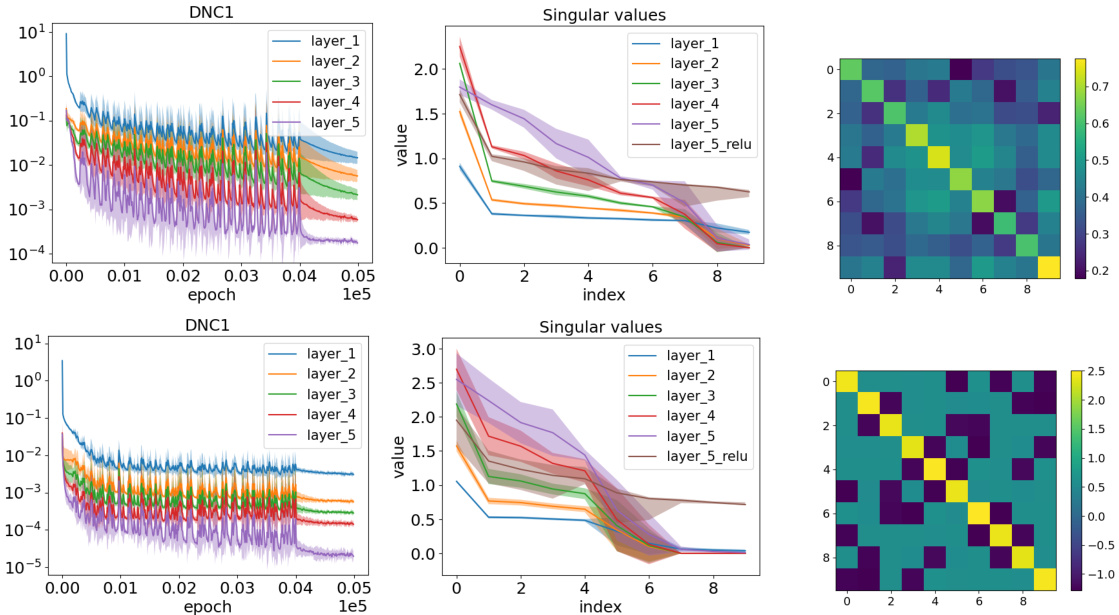

🔼 This figure compares the training performance of a 4-layer deep unconstrained features model (DUFM) and a ResNet20 with a 4-layer MLP head on CIFAR-10. The top row shows the results for the DUFM, illustrating training loss, DNC1 metric (measuring within-class collapse), and singular value distribution at convergence. The bottom row presents the same metrics for the ResNet20/MLP model, using a DUFM-like regularization scheme. The results demonstrate that low-rank solutions, in agreement with the theory, outperform deep neural collapse (DNC) solutions.

read the caption

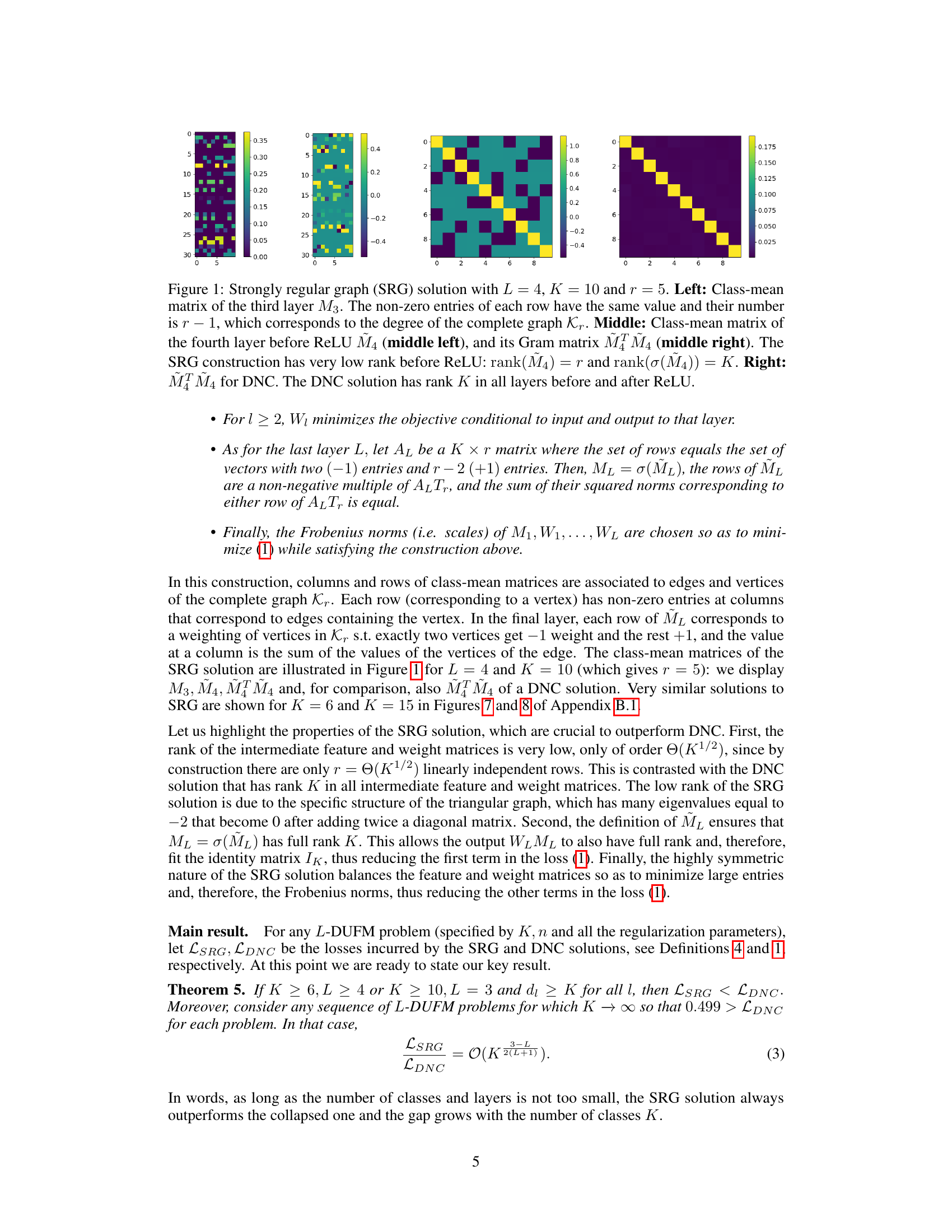

Figure 2: Training loss compared against DNC and SRG losses (left), DNC1 metric training progression (middle) and singular value distribution at convergence (right). Top row: 4-DUFM training with K = 10, λ = 0.004 for all regularization parameters, learning rate of 0.5 and width 30. Results are averaged over 10 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation. Bottom row: Training of a ResNet20 with a 4-layer MLP head on CIFAR10, using a DUFM-like regularization. We use weight decay 0.005 except λH1 = 0.000005 (to compensate for n = 5000, which significantly influences the total regularization strength), learning rate 0.05 and width 64 for all the MLP layers. Results are averaged over 5 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation.

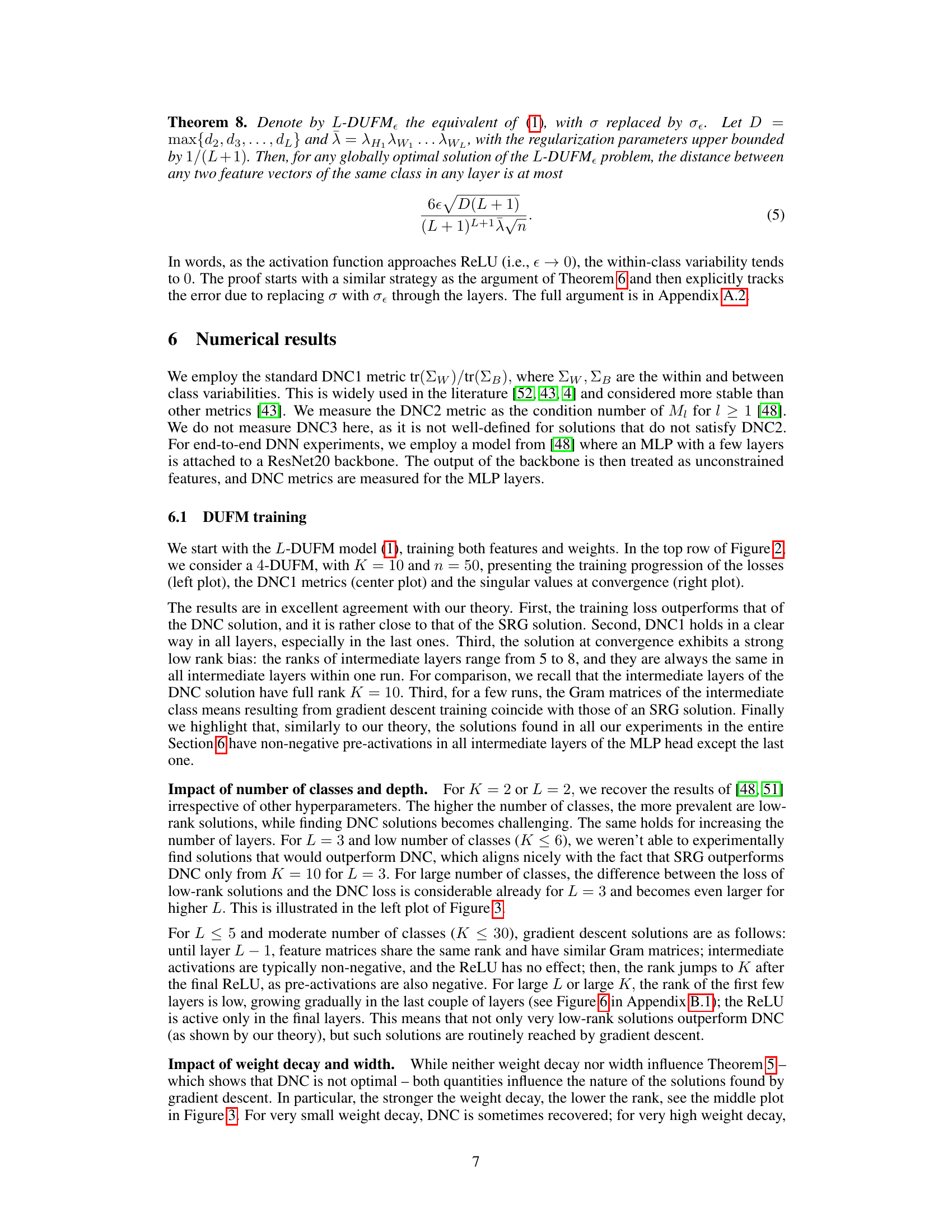

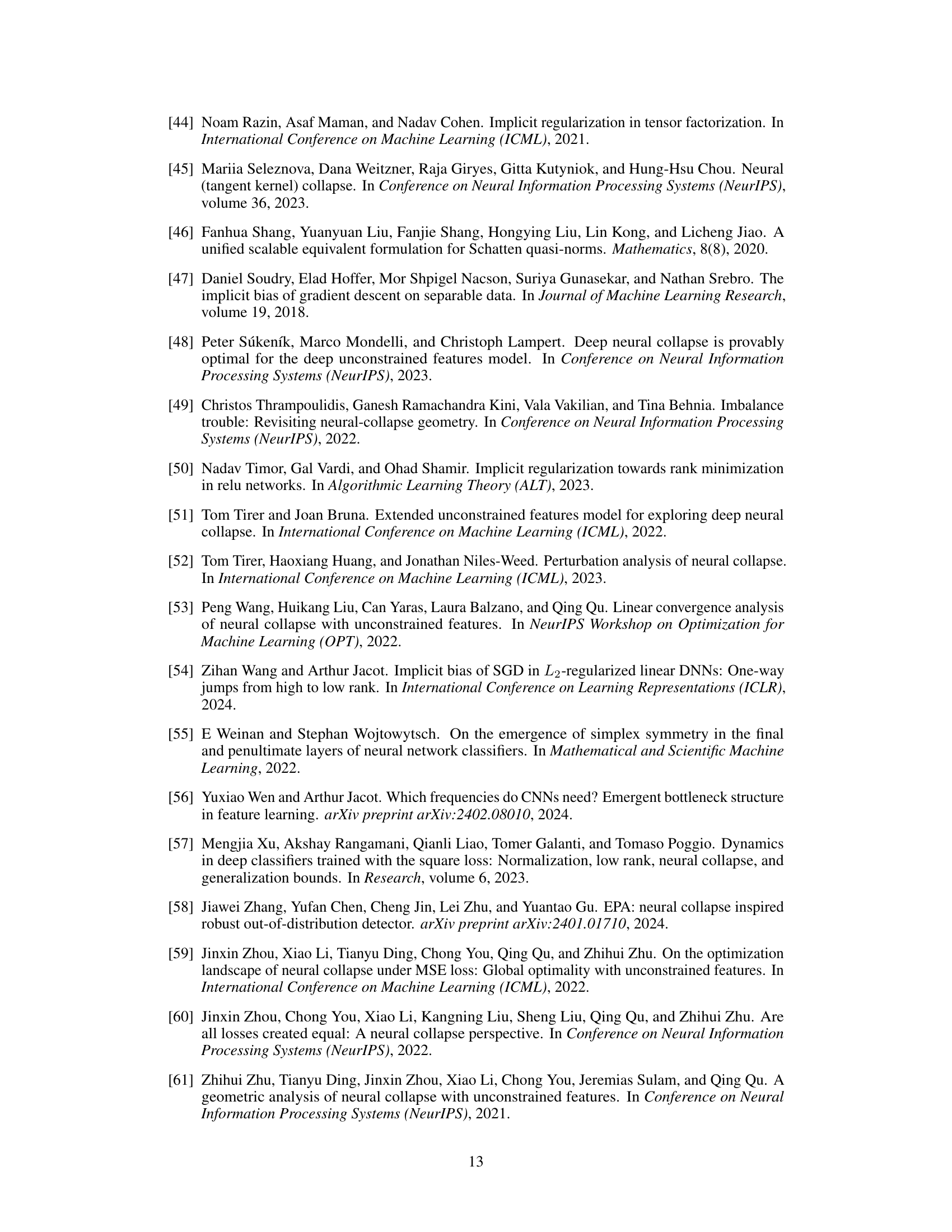

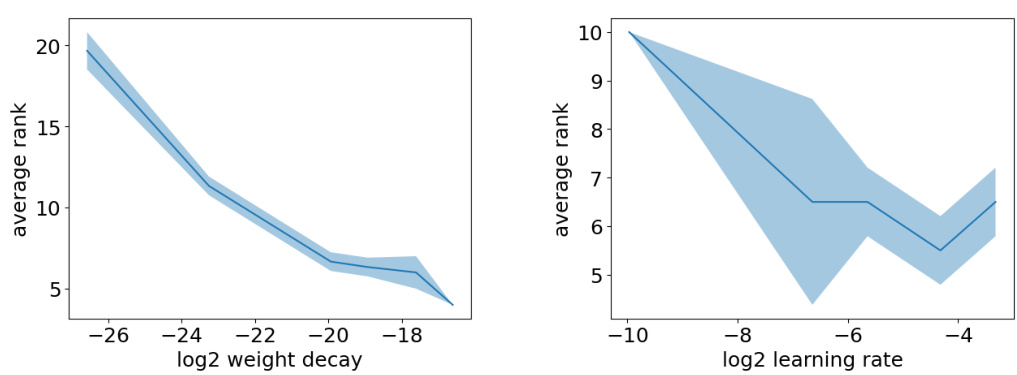

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on an L-DUFM model, illustrating the impact of various hyperparameters on the model’s performance and the emergence of neural collapse. The left plot shows the ratio of losses between the SRG solution and the DNC solution, highlighting the superiority of the SRG solution in certain parameter regimes. The middle plot demonstrates the effect of weight decay on the average rank of the obtained solutions, while the right plot illustrates the influence of network width on the probability of obtaining a DNC solution.

read the caption

Figure 3. All experiments refer to the training of an L-DUFM model. Results are averaged over 5 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation. Left: Ratio between SRG and DNC loss (LSRG/LDNC), as a function of r, where the number of classes is K = (2). Different curves correspond to different values of L ∈ {3,4,5}. Middle: Average rank at convergence, as a function of the weight decay in log2-scale, when L = 4 and K = 10. Right: Empirical probability of finding a DNC solution as a function of the width, when L = 4 and K = 10.

🔼 This figure compares the training performance of a 4-layer deep unconstrained features model (4-DUFM) and a ResNet20 with a 4-layer MLP head on CIFAR-10. The left plots show the training loss compared to the losses of deep neural collapse (DNC) and the strongly regular graph (SRG) solutions. The center plots display the DNC1 metric’s training progression, measuring within-class variability. The right plots illustrate the singular value distributions at convergence. The top row focuses on 4-DUFM training, while the bottom row shows results from training on CIFAR-10 with DUFM-like regularization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training loss compared against DNC and SRG losses (left), DNC1 metric training progression (middle) and singular value distribution at convergence (right). Top row: 4-DUFM training with K = 10, λ = 0.004 for all regularization parameters, learning rate of 0.5 and width 30. Results are averaged over 10 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation. Bottom row: Training of a ResNet20 with a 4-layer MLP head on CIFAR10, using a DUFM-like regularization. We use weight decay 0.005 except λH₁ = 0.000005 (to compensate for n = 5000, which significantly influences the total regularization strength), learning rate 0.05 and width 64 for all the MLP layers. Results are averaged over 5 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation.

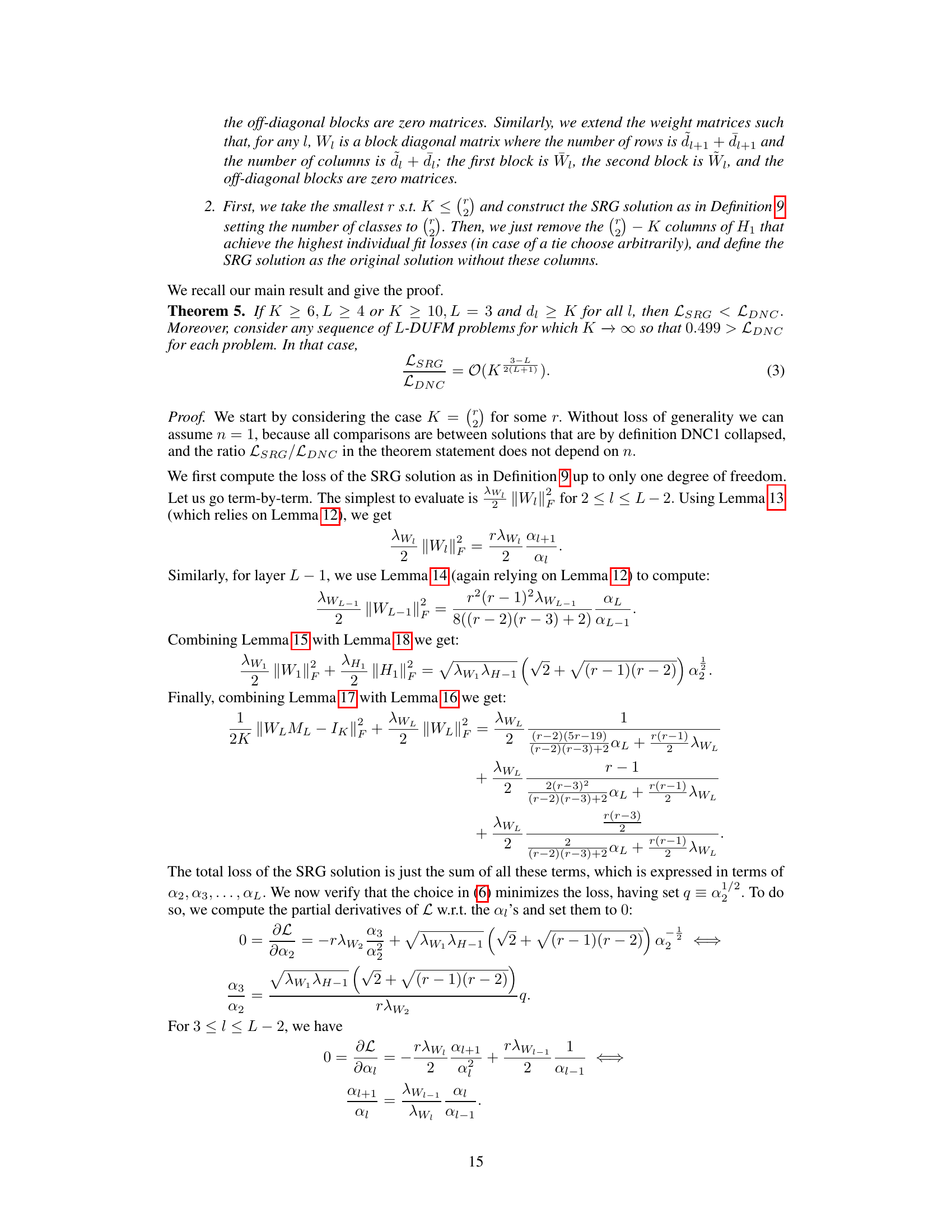

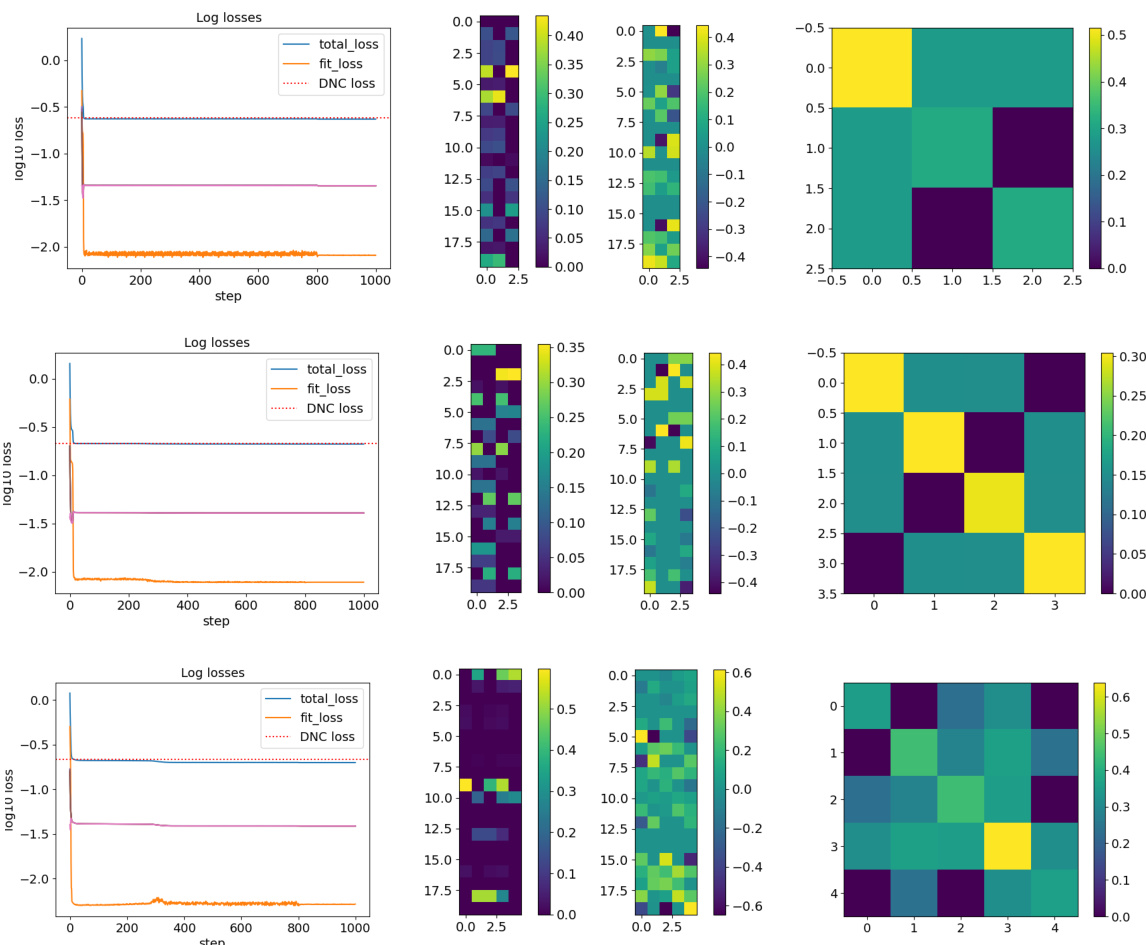

🔼 This figure presents the results of 4-layer deep unconstrained features model (DUFM) training with three different numbers of classes (K=3, 4, and 5). The left column shows the loss progression, broken down into total loss, fitting loss, and neural collapse (NC) loss. The middle column shows visualizations of the class-mean matrices M3 (middle-left) and M4 (middle-right) for each case. The right column visualizes the Gram matrix M3M3, showing the relationships between class means. The figure demonstrates that even with a small number of classes and layers, low-rank solutions outperform deep neural collapse.

read the caption

Figure 5: 4-DUFM training for K = 3 (top), K = 4 (middle), and K = 5 (bottom). Left: Loss progression, also decomposed into the fit and regularization terms. Middle left: Visualization of the matrix M3. Middle right: Visualization of the matrix M4. Right: Visualization of the matrix M3M3.

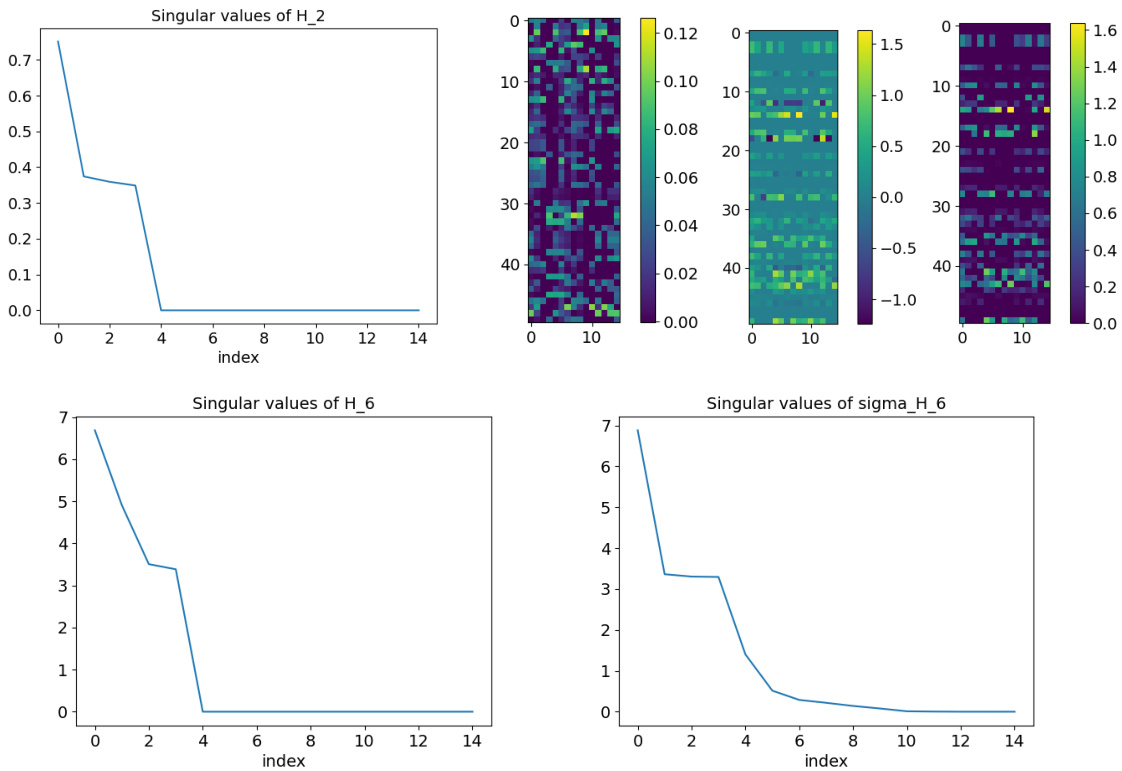

🔼 This figure visualizes the class-mean matrices and singular values at convergence for a deep unconstrained features model (DUFM) with 15 classes and 7 layers. The top row shows singular values of the second layer’s class-mean matrix (M2) alongside visualizations of the matrices M2, M6, and their Gram matrix (M6M6). The bottom row presents singular values for the sixth layer’s features (H6) before and after the ReLU activation (σ(H6)). This illustrates the low-rank properties observed in intermediate layers.

read the caption

Figure 6: Class-mean matrices and singular values at convergence for a DUFM model with K = 15 and L = 7. Top row: Singular values of M2, and visualization of the matrices M2, M6, M6 and M6. Bottom row: Singular values of H6 and H6.

🔼 This figure presents the results of 4-layer deep unconstrained feature model (DUFM) training experiments for different numbers of classes (K=3, 4, and 5). Each row shows results for a specific value of K. The left column displays the training loss progression, broken down into the total loss, fitting loss, and regularization loss. The middle columns show visualizations of the class-mean matrices M3 and M4 (matrices of the class means stacked into columns) at layer 3 and layer 4 respectively. The right column visualizes the Gram matrix, M3M3, showing the relationships between the class means in layer 3.

read the caption

Figure 5. 4-DUFM training for K = 3 (top), K = 4 (middle), and K = 5 (bottom). Left: Loss progression, also decomposed into the fit and regularization terms. Middle left: Visualization of the matrix M3. Middle right: Visualization of the matrix M4. Right: Visualization of the matrix M3M3.

🔼 This figure shows the results of 4-layer deep unconstrained feature model (DUFM) training for different numbers of classes (K=3, 4, and 5). The left column displays the loss progression, broken down into total loss, fit loss (how well the model fits the data), and regularization loss. The middle column presents visualizations of the class-mean matrices (M3 and M4) for the third and fourth layers. The right column visualizes the Gram matrices (M3M3) which shows the relationships between class means. The results demonstrate that even for a small number of layers and classes, the low-rank solutions outperform the deep neural collapse (DNC).

read the caption

Figure 5. 4-DUFM training for K = 3 (top), K = 4 (middle), and K = 5 (bottom). Left: Loss progression, also decomposed into the fit and regularization terms. Middle left: Visualization of the matrix M3. Middle right: Visualization of the matrix M4. Right: Visualization of the matrix M3M3.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three different approaches (standard training, deep neural collapse, and the proposed low-rank solution) on a four-layer deep unconstrained features model (4-DUFM) with 10 classes. The top row shows results for the 4-DUFM, while the bottom row illustrates the results when applying the same approaches on a ResNet20 backbone with a 4-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) head, trained on CIFAR10 dataset. The plots depict training loss, the DNC1 metric (measuring within-class collapse), and singular value distributions at the end of training. The results demonstrate that the proposed approach achieves lower training loss than DNC, exhibiting a strong low-rank bias. The results confirm that DNC1 (within-class variability collapse) holds.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training loss compared against DNC and SRG losses (left), DNC1 metric training progression (middle) and singular value distribution at convergence (right). Top row: 4-DUFM training with K = 10, λ = 0.004 for all regularization parameters, learning rate of 0.5 and width 30. Results are averaged over 10 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation. Bottom row: Training of a ResNet20 with a 4-layer MLP head on CIFAR10, using a DUFM-like regularization. We use weight decay 0.005 except λH1 = 0.000005 (to compensate for n = 5000, which significantly influences the total regularization strength), learning rate 0.05 and width 64 for all the MLP layers. Results are averaged over 5 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation.

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments on the L-DUFM model, which explores the impact of various hyperparameters on the loss and rank of solutions at convergence. It consists of three subplots: The left subplot illustrates the ratio of SRG loss to DNC loss as a function of r, showing that SRG outperforms DNC for different depths (L). The middle subplot shows how the average rank varies with weight decay, revealing a low-rank bias. Finally, the right subplot demonstrates the relationship between the width and the probability of obtaining a DNC solution, indicating that larger widths favor DNC.

read the caption

Figure 3. All experiments refer to the training of an L-DUFM model. Results are averaged over 5 runs, and we show the confidence intervals at 1 standard deviation. Left: Ratio between SRG and DNC loss (LSRG/LDNC), as a function of r, where the number of classes is K = (2). Different curves correspond to different values of L ∈ {3,4,5}. Middle: Average rank at convergence, as a function of the weight decay in log2-scale, when L = 4 and K = 15. Right: Empirical probability of finding a DNC solution as a function of the width, when L = 4 and K = 10.

Full paper#