TL;DR#

Many real-world systems are continuous in time, but most reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms are designed for discrete-time systems. Applying discrete-time RL to continuous systems often necessitates costly discretization and frequent interactions with the system. This can be especially problematic in applications where each interaction is expensive (e.g., medical treatments, greenhouse control). This paper introduces a novel framework, TACOS, that tackles this challenge.

TACOS optimizes policies that predict both the control action and its duration, resulting in an extended MDP that standard RL algorithms can solve. The authors demonstrate that state-of-the-art RL algorithms trained on TACOS drastically reduce interactions while maintaining performance. Furthermore, they introduce OTACOS, an efficient model-based algorithm with proven sublinear regret for sufficiently smooth systems. Experiments on various robotic tasks showcase TACOS’s superior performance and robustness against discretization frequency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning and control systems. It directly addresses the limitations of discrete-time RL in continuous systems, offering a novel framework (TACOS) for more efficient and cost-effective control. The theoretical analysis and empirical results provide significant insights, opening up new avenues for research in continuous-time RL and impacting real-world applications involving costly interactions.

Visual Insights#

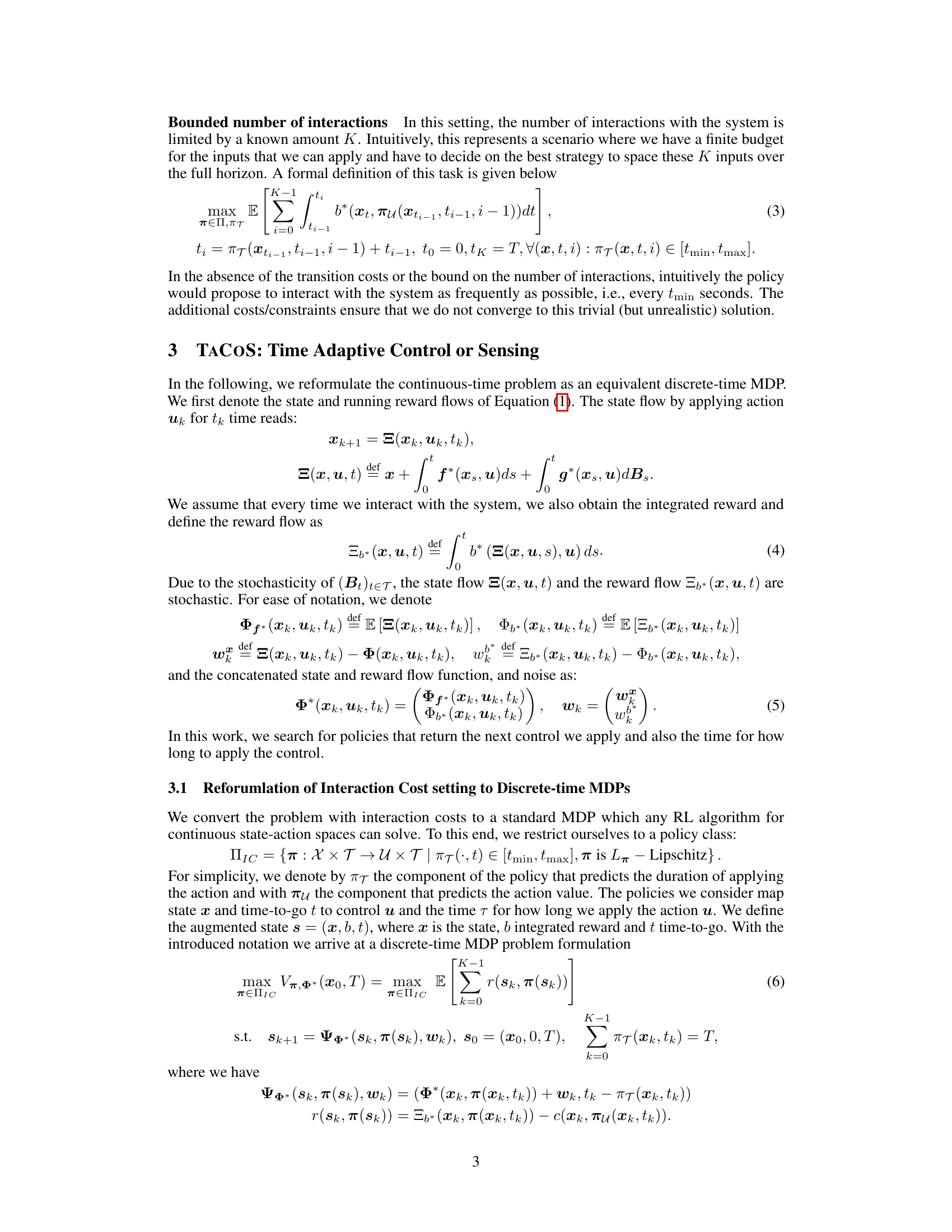

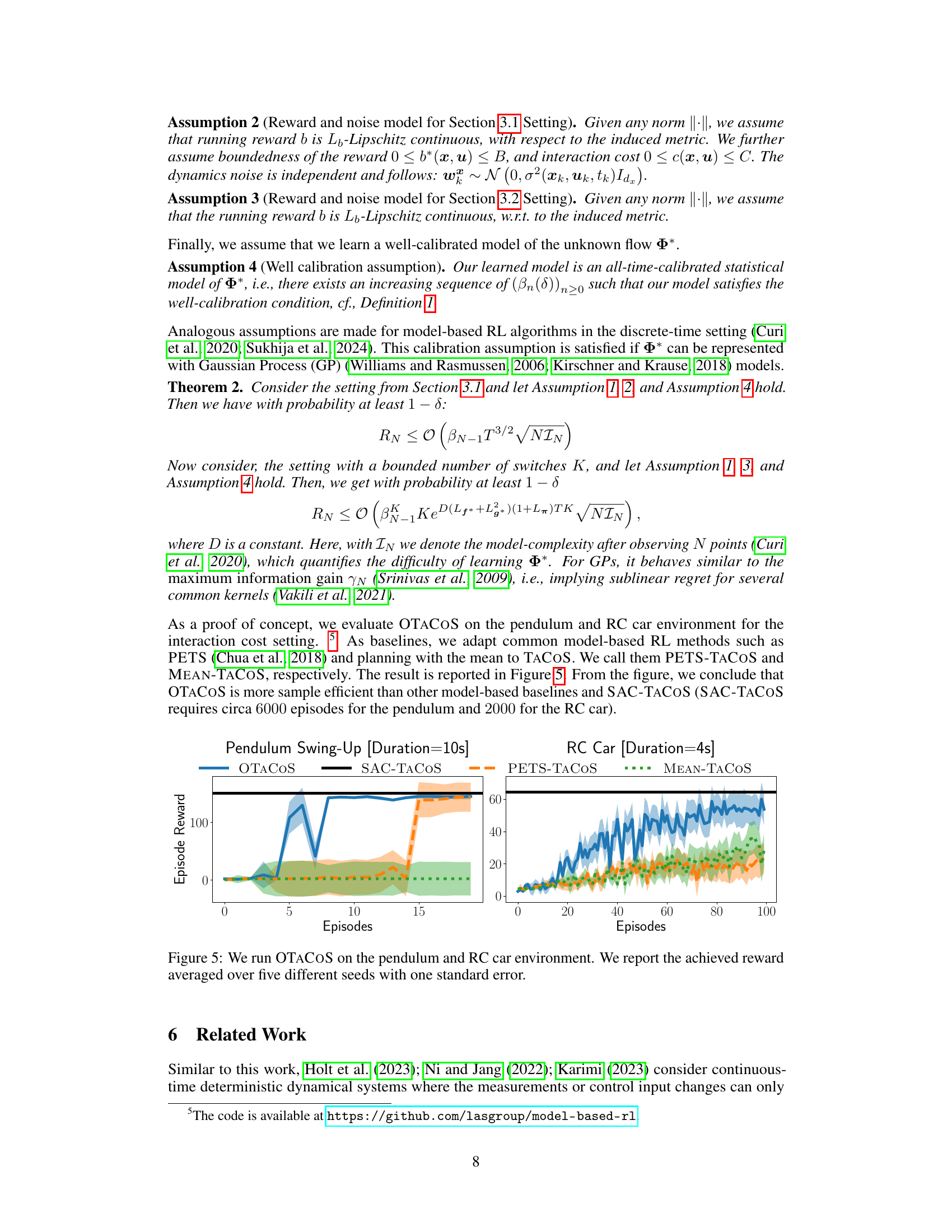

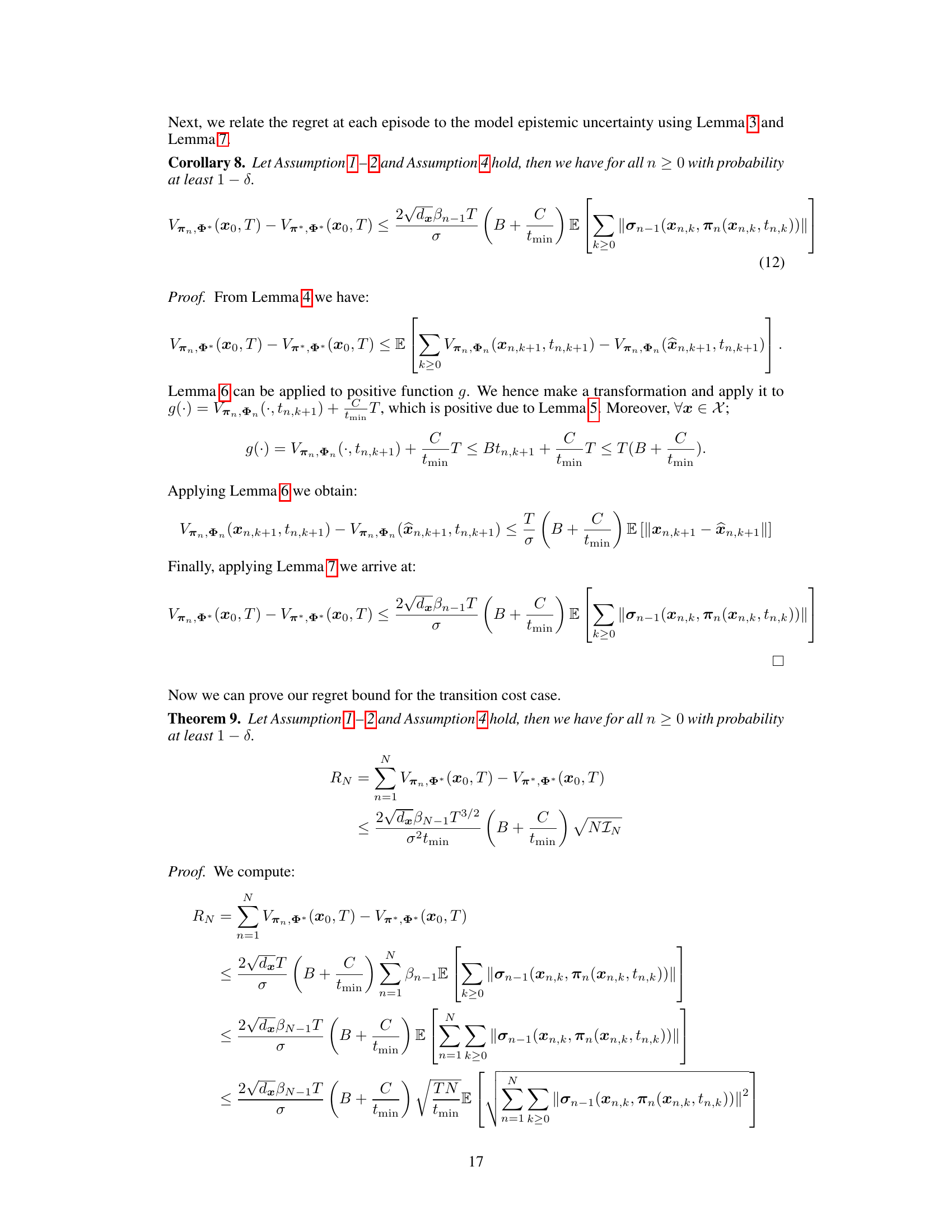

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment conducted on a pendulum environment using two different settings: average cost and bounded number of switches. The average cost setting penalizes each interaction with a constant cost, leading to fewer interactions overall and a smoother control trajectory. The bounded number of switches setting limits the total number of interactions, resulting in a policy that strategically chooses the timing of those interactions to maximize reward. The plots show state trajectories, control actions, reward, and time steps.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experiment on the Pendulum environment for the average cost and a bounded number of switches setting.

In-depth insights#

Time-Adaptive RL#

Time-adaptive Reinforcement Learning (RL) addresses the limitations of traditional RL methods, which often assume discrete-time Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). Many real-world systems are inherently continuous, making discrete-time approximations inaccurate and inefficient. Time-adaptive RL optimizes policies by not only selecting actions but also determining the duration for which each action is applied. This approach is particularly beneficial when interactions with the system are costly, such as in medical treatments or environmental control. By learning both the optimal control actions and the appropriate timing of those actions, time-adaptive RL algorithms achieve superior performance with drastically fewer interactions compared to their discrete-time counterparts. This improved sample efficiency is crucial in scenarios with limited resources and high interaction costs. The theoretical framework of time-adaptive RL involves reformulating the continuous-time problem into an equivalent discrete-time MDP, enabling the use of standard RL algorithms. Model-based approaches further enhance sample efficiency, providing a promising direction for future research in time-adaptive RL.

TACOS Framework#

The TACOS framework presents a novel approach to reinforcement learning (RL) in continuous-time systems by addressing the limitations of discrete-time approximations. It’s core innovation lies in its time-adaptive strategy, allowing the RL agent to optimize not only the control actions but also the duration of their application. This leads to significant improvements in sample efficiency and robustness, especially in scenarios where interactions with the system are costly. By optimizing over both actions and durations, TACOS effectively reduces the need for frequent, potentially wasteful, interactions. This is particularly beneficial in domains such as medical treatment or greenhouse control where measurements and actions require significant manual intervention. The framework’s elegance lies in its ability to transform the continuous-time RL problem into an equivalent discrete-time Markov Decision Process (MDP), which allows for application of standard RL algorithms. Furthermore, the introduction of model-based optimization within TACOS (OTACOS) offers enhanced sample efficiency and allows for theoretical guarantees in specific settings.

Model-Based RL#

Model-based reinforcement learning (RL) offers a compelling alternative to model-free methods by leveraging learned models of the environment’s dynamics. This approach enables planning, significantly improving sample efficiency and potentially leading to better generalization. The core idea is to learn a model from interaction data, then use this model to simulate the environment and plan optimal actions. This planning can take various forms, from tree search to direct optimization of a value function. Model-based RL faces challenges such as model bias (inaccuracies in the learned model) and model uncertainty (the model’s confidence levels). Addressing these challenges is crucial for effective performance. Techniques like ensemble methods can reduce bias, while techniques such as optimistic planning or uncertainty-aware planning can mitigate the impact of uncertainty. The choice of model architecture is also a key consideration, with options ranging from simple linear models to complex neural networks, each with its own trade-offs regarding expressiveness and computational cost. Ultimately, the success of model-based RL hinges on the balance between model accuracy and computational efficiency, making it a fertile area of ongoing research.

Empirical Results#

An empirical results section in a reinforcement learning (RL) paper would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed time-adaptive approach (TACOS) against state-of-the-art baselines on various continuous-time control tasks. Key aspects to include would be comparisons of performance metrics (e.g., episode reward, average cost, number of interactions), sample efficiency, and robustness to different hyperparameters and environmental stochasticity. The results should clearly demonstrate that TACOS achieves superior performance in minimizing interactions while maintaining or even improving task performance. Visualizations, like plots showing episode rewards and number of interactions against various settings, are crucial for illustrating these findings effectively. A discussion on the computational cost of TACOS compared to discrete-time methods would strengthen the evaluation. Finally, the analysis should include an investigation into the impact of the minimal action duration parameter, tmin, to show TACOS’s robustness to its choice. A strong empirical results section would bolster confidence in the proposed method and provide practical insights into its strengths and limitations.

Future Works#

Future work could explore several promising directions. Extending TACOS to handle asynchronous sensing and control is crucial for real-world applicability, where measurements and actions may not be perfectly synchronized. Investigating alternative reward functions and cost structures beyond the ones considered could further enhance the framework’s adaptability to diverse scenarios. A deeper investigation into the theoretical guarantees of OTACOS under more relaxed assumptions about the model and environment dynamics is needed. Empirical evaluation on a wider range of continuous-time systems, particularly those with complex dynamics or high dimensionality, would provide stronger evidence of TACOS’s generalizability. Finally, researching combinations of TACOS with other advanced RL techniques, such as hierarchical reinforcement learning or transfer learning, could unlock even greater efficiency and scalability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments conducted on a pendulum swing-up task using two different settings: average cost and bounded number of switches. The plots illustrate the state (cos(θ), sin(θ)), action, running reward, and time for action, over time for each setting. The average cost setting shows a significant reduction in the number of interactions, while the bounded number of switches setting demonstrates that the task can still be solved with a limited number of interactions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experiment on the Pendulum environment for the average cost and a bounded number of switches setting.

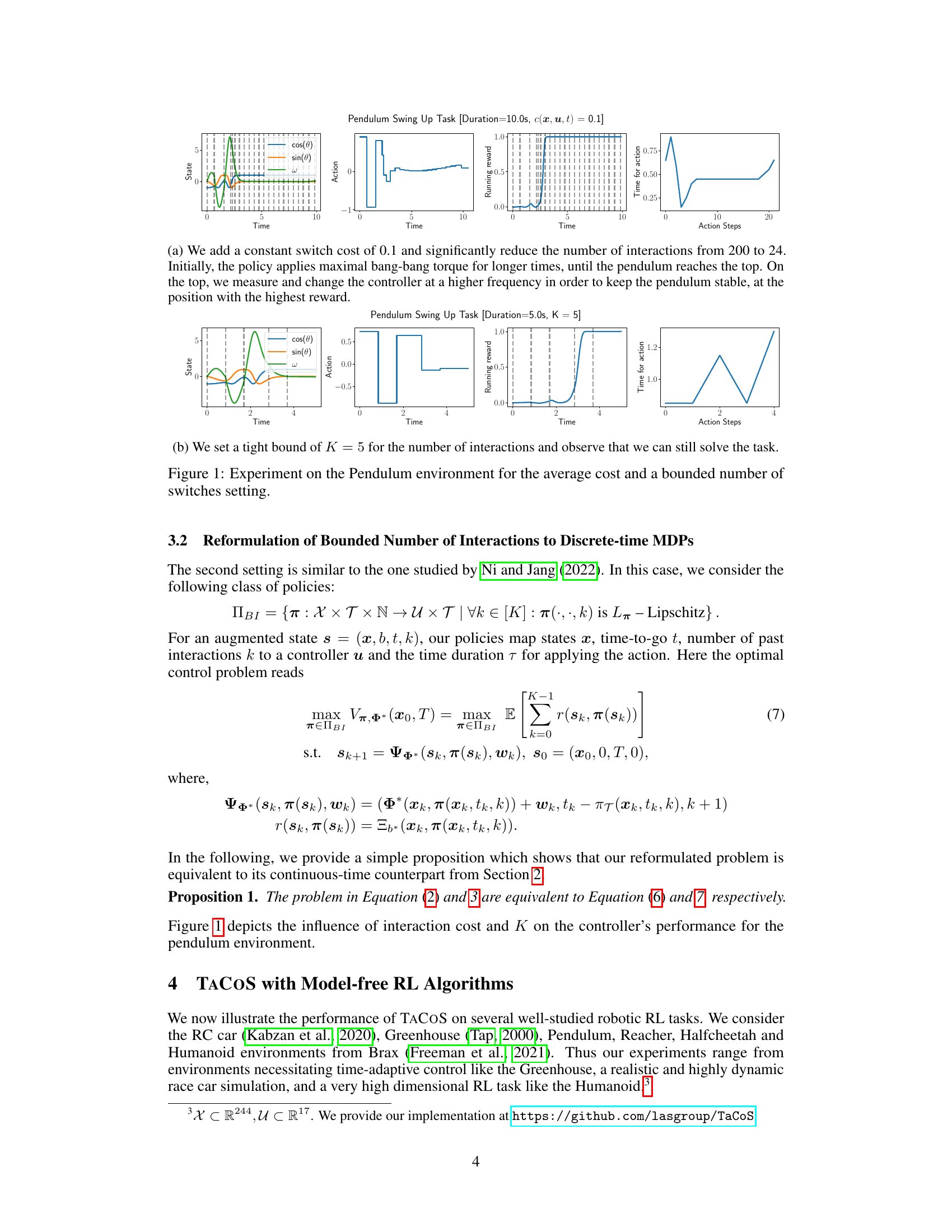

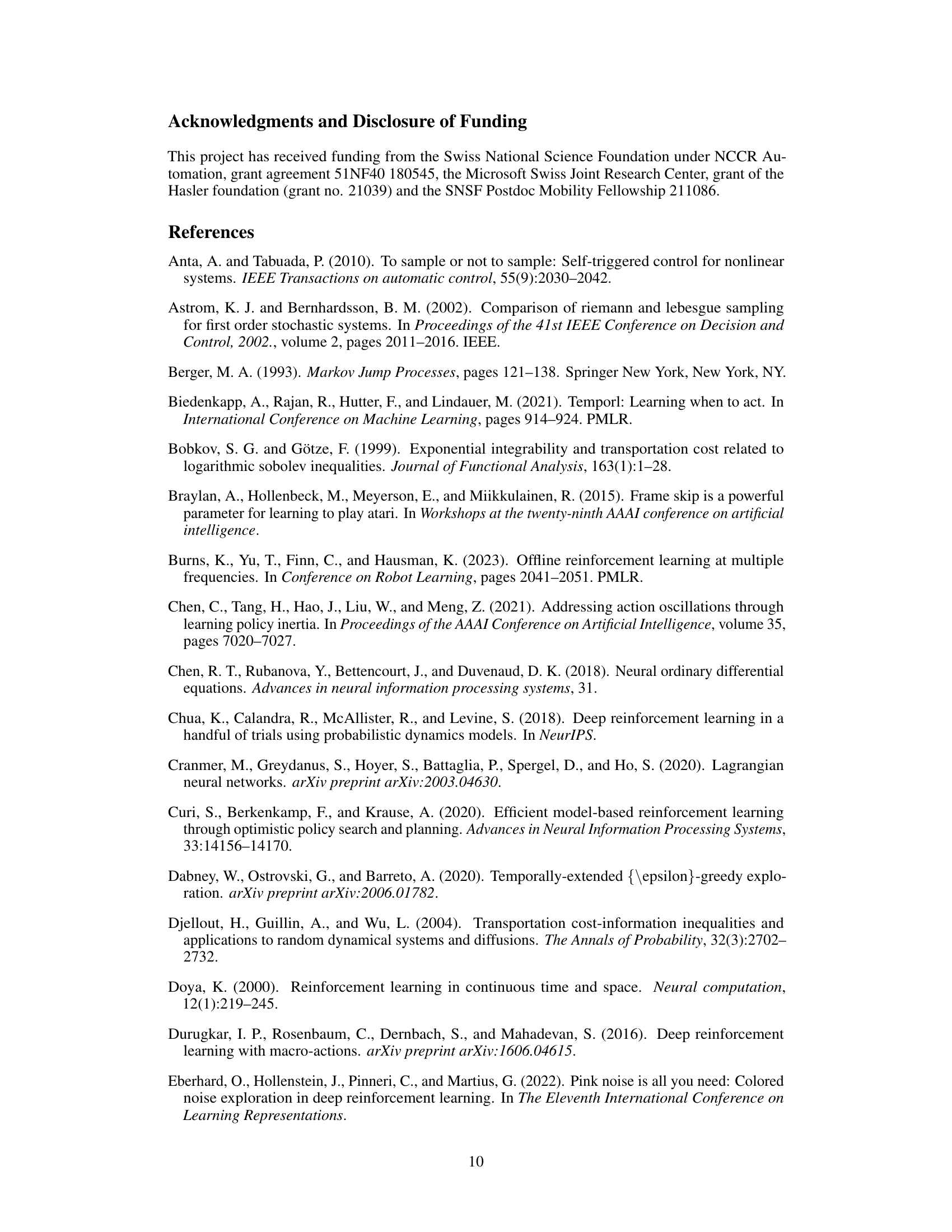

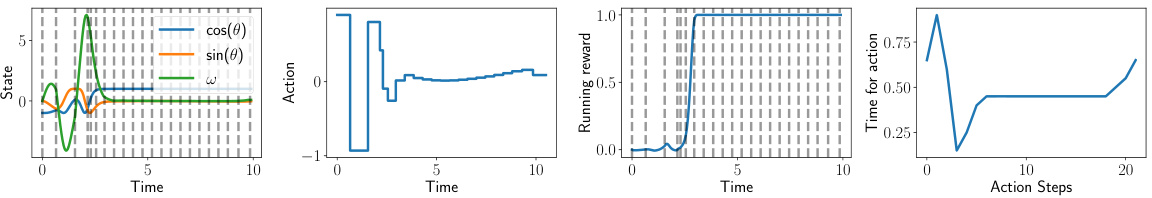

🔼 This figure compares the performance of TACOS against an equidistant time discretization baseline for three different tasks: Greenhouse Temperature Tracking, Pendulum Swing-up, and Pendulum Swing-down. The x-axis represents the number of interactions, and the y-axis shows the episode reward. The solid lines represent TACOS, and the dashed lines represent the equidistant baseline. The shaded regions indicate the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results clearly show that TACOS achieves significantly higher rewards than the baseline, especially when the number of interactions (K) is small, highlighting its efficiency in reducing interactions while maintaining or improving performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: We study the effects of the bound on interactions K on the performance of the agent. TACOS performs significantly better than equidistant discretization, especially for small values of K.

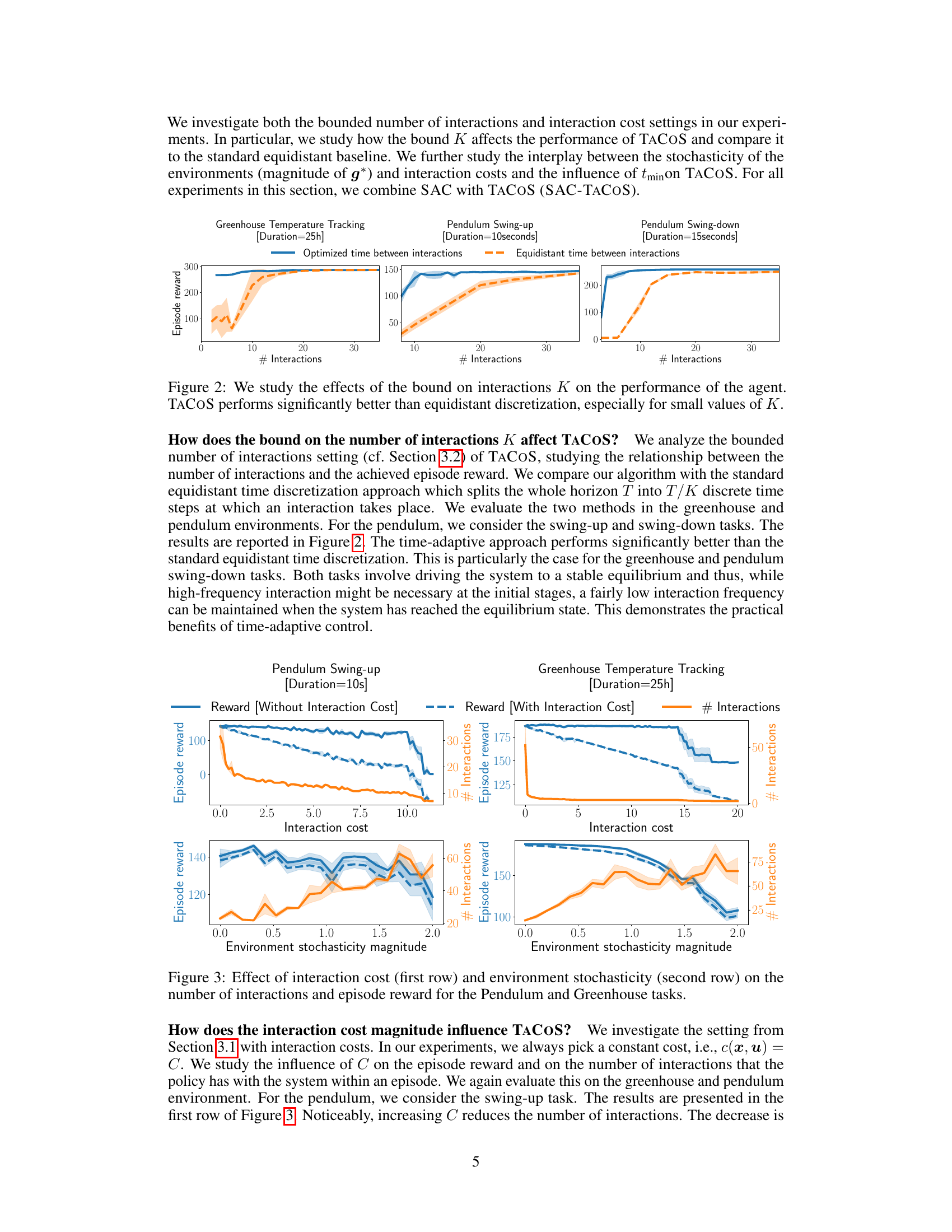

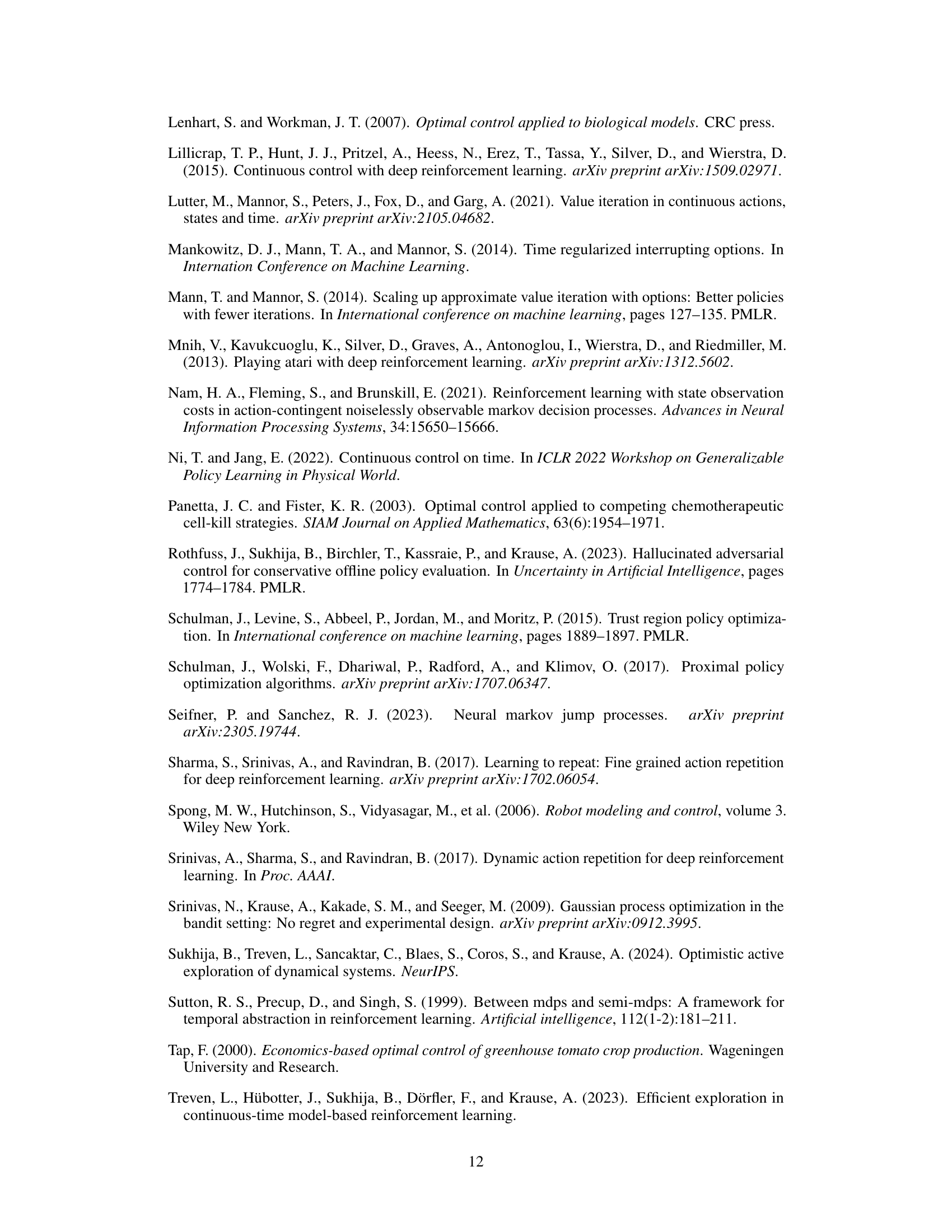

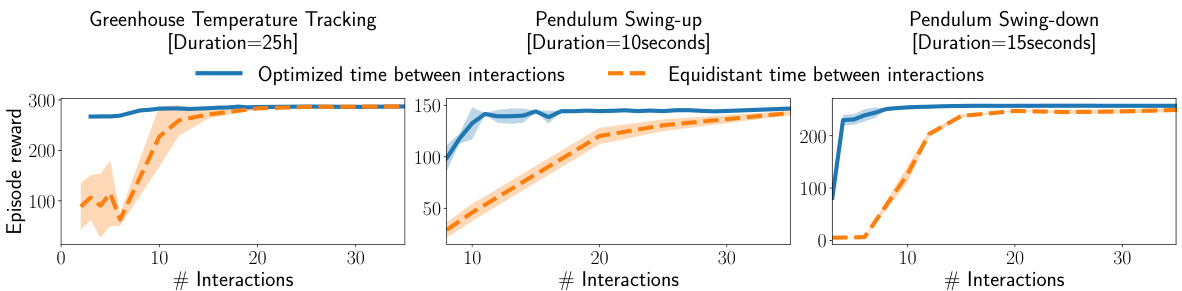

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments evaluating the effect of interaction cost and environment stochasticity on the performance of the TACOS algorithm. The first row shows the impact of increasing interaction cost (C) on both the episode reward and the number of interactions for the Pendulum Swing-up and Greenhouse Temperature Tracking tasks. The second row displays the influence of increasing environment stochasticity (magnitude of g*) on the same metrics, revealing how the algorithm adapts to more challenging scenarios. The shaded regions represent the standard deviation across multiple experimental runs.

read the caption

Figure 3: Effect of interaction cost (first row) and environment stochasticity (second row) on the number of interactions and episode reward for the Pendulum and Greenhouse tasks.

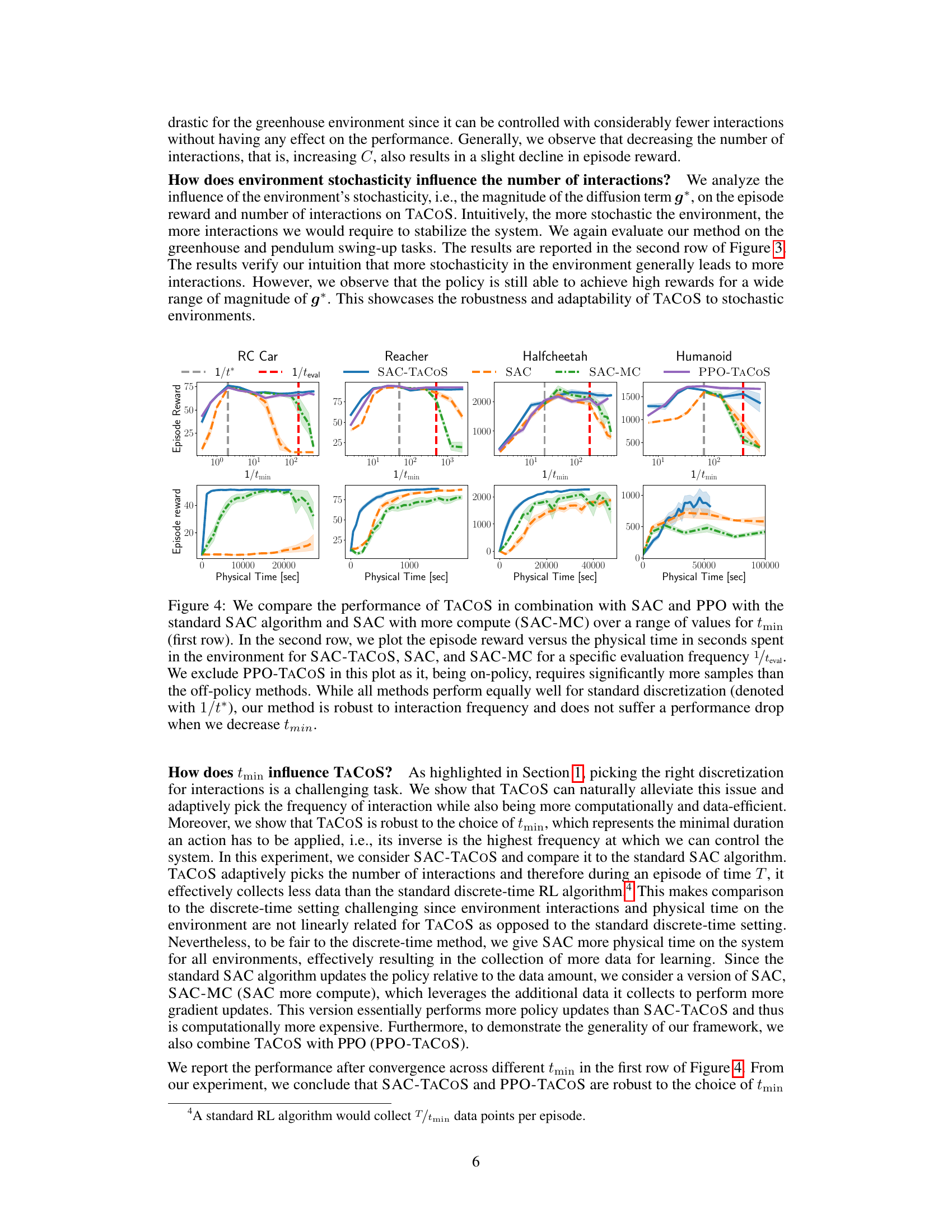

🔼 The figure compares the performance of different RL algorithms, including SAC-TACOS, on various robotic tasks across different interaction frequencies. The top row shows how the performance changes with respect to the minimum time between interactions (tmin), while the bottom row visualizes the trade-off between episode reward and physical time.

read the caption

Figure 4: We compare the performance of TACOS in combination with SAC and PPO with the standard SAC algorithm and SAC with more compute (SAC-MC) over a range of values for tmin (first row). In the second row, we plot the episode reward versus the physical time in seconds spent in the environment for SAC-TACOS, SAC, and SAC-MC for a specific evaluation frequency 1/teval. We exclude PPO-TACOS in this plot as it, being on-policy, requires significantly more samples than the off-policy methods. While all methods perform equally well for standard discretization (denoted with 1/t*), our method is robust to interaction frequency and does not suffer a performance drop when we decrease tmin.

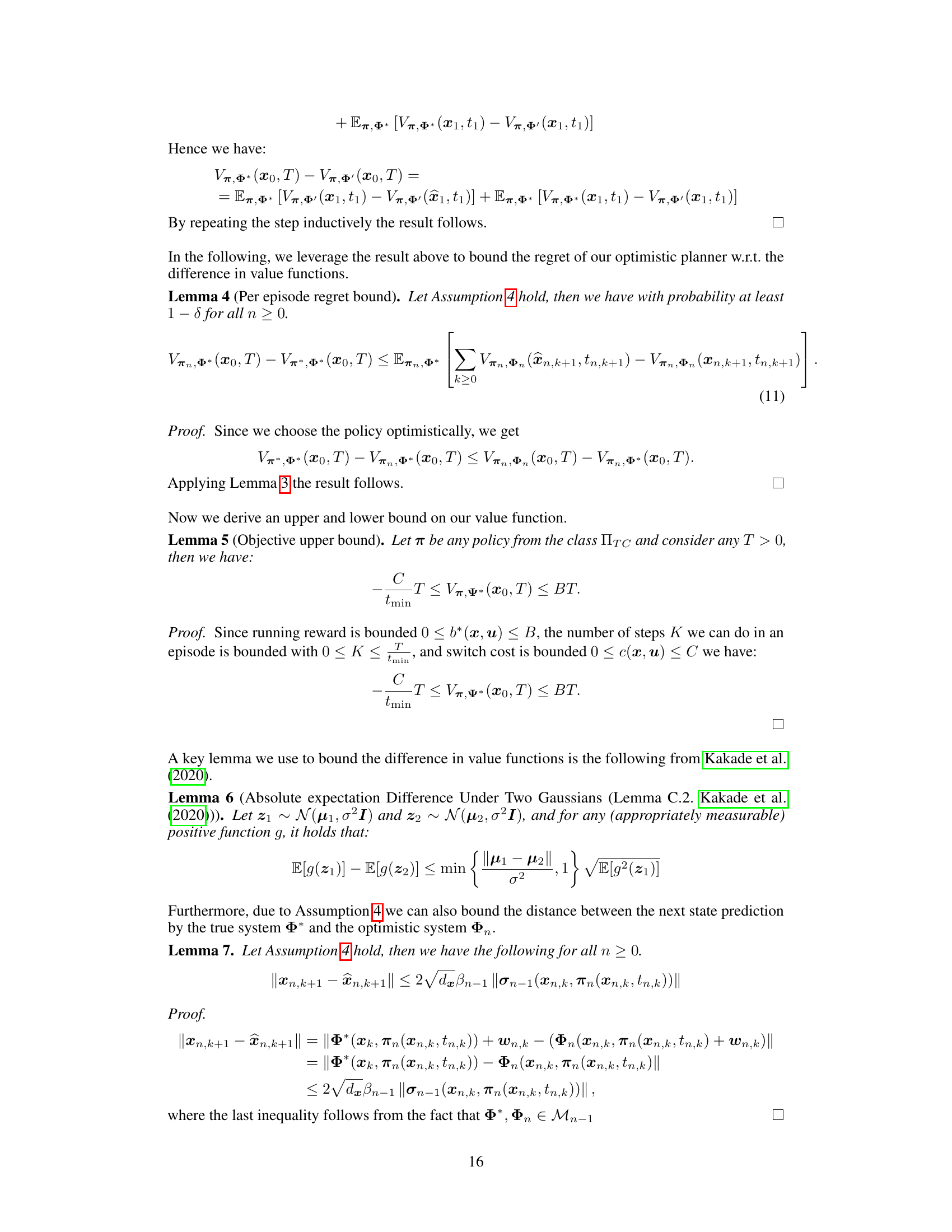

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the OTACOS algorithm against other model-based reinforcement learning methods (PETS-TACOS and MEAN-TACOS) and a model-free method (SAC-TACOS) on two robotic control tasks: pendulum swing-up and RC car driving. The results show the episodic rewards (averaged over five runs) over the number of episodes. Shaded areas indicate the standard error of the mean. OTACOS demonstrates superior sample efficiency compared to baselines, reaching higher rewards more quickly.

read the caption

Figure 5: We run OTACOS on the pendulum and RC car environment. We report the achieved rewards averaged over five different seeds with one standard error.

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments conducted on a pendulum swing-up task using two different settings: one with a constant cost for each interaction, and another with a fixed, limited number of interactions. The plots illustrate the state (cosine and sine of the angle), action (torque), running reward, and time for each action for both settings. The figure demonstrates that the proposed method effectively reduces the number of interactions needed to achieve successful control. (a) shows significant reduction in interaction numbers by adding a constant interaction cost, demonstrating effective control with minimal intervention. (b) shows the ability to successfully solve the task even with a drastically reduced number of interactions (K=5).

read the caption

Figure 1: Experiment on the Pendulum environment for the average cost and a bounded number of switches setting.

🔼 This figure presents the results of an experiment on a pendulum swing-up task using two different settings: average cost and bounded number of switches. The top row (a) shows the results for the average cost setting, where the policy learns to reduce the number of interactions from 200 to 24 by applying maximal torque for longer durations initially and switching the controller more frequently near the equilibrium position. The bottom row (b) illustrates the bounded number of interactions setting (K=5), where the policy successfully solves the task with a limited number of interactions, demonstrating adaptability of the approach.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experiment on the Pendulum environment for the average cost and a bounded number of switches setting.

Full paper#